Can Sustainability and Biodiversity Conservation Save Native Goat Breeds? The Situation in Campania Region (Southern Italy) between History and Regional Policy Interventions

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Description of the Goat Sector and Trends at the National and Regional Level

2.2. Analysis of National and Regional Policies for the Livestock Sector

3. Results

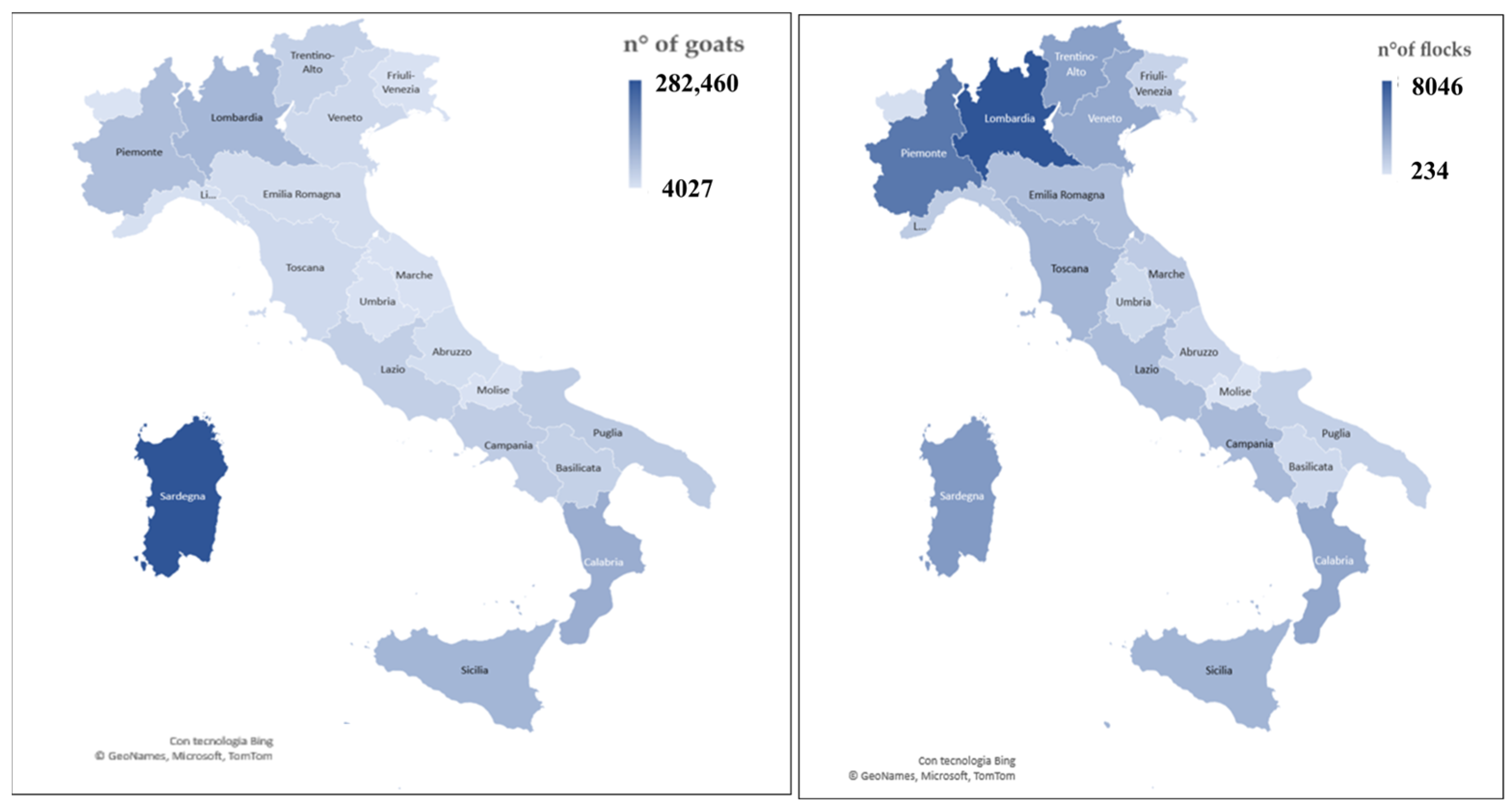

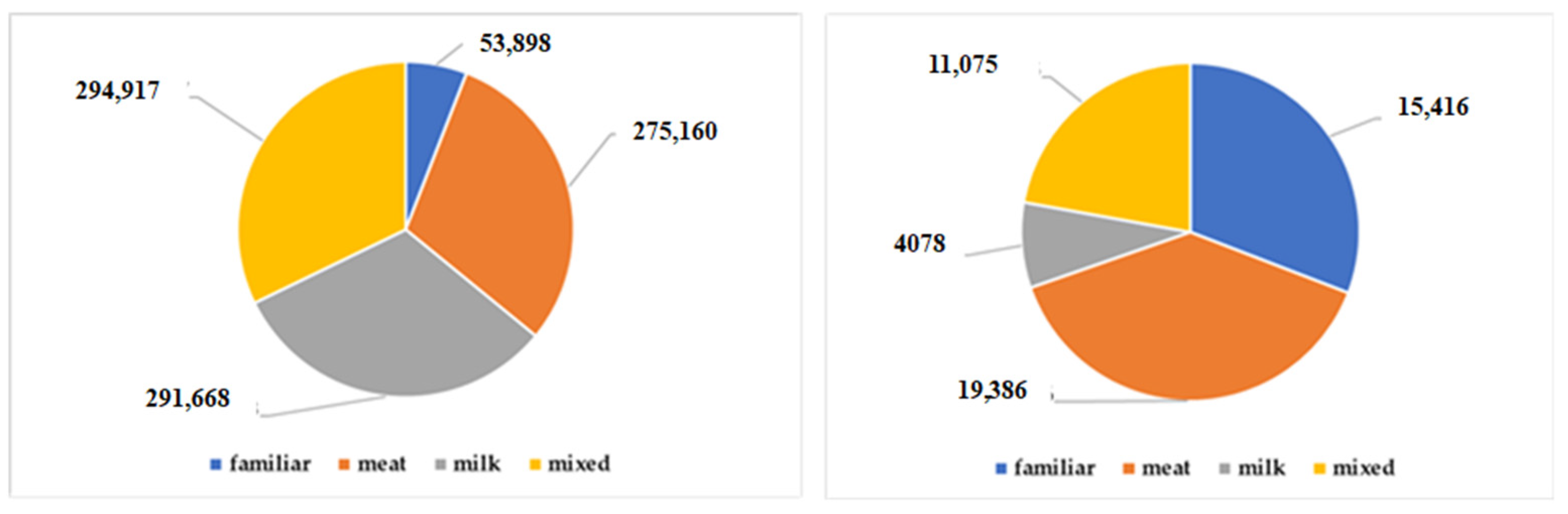

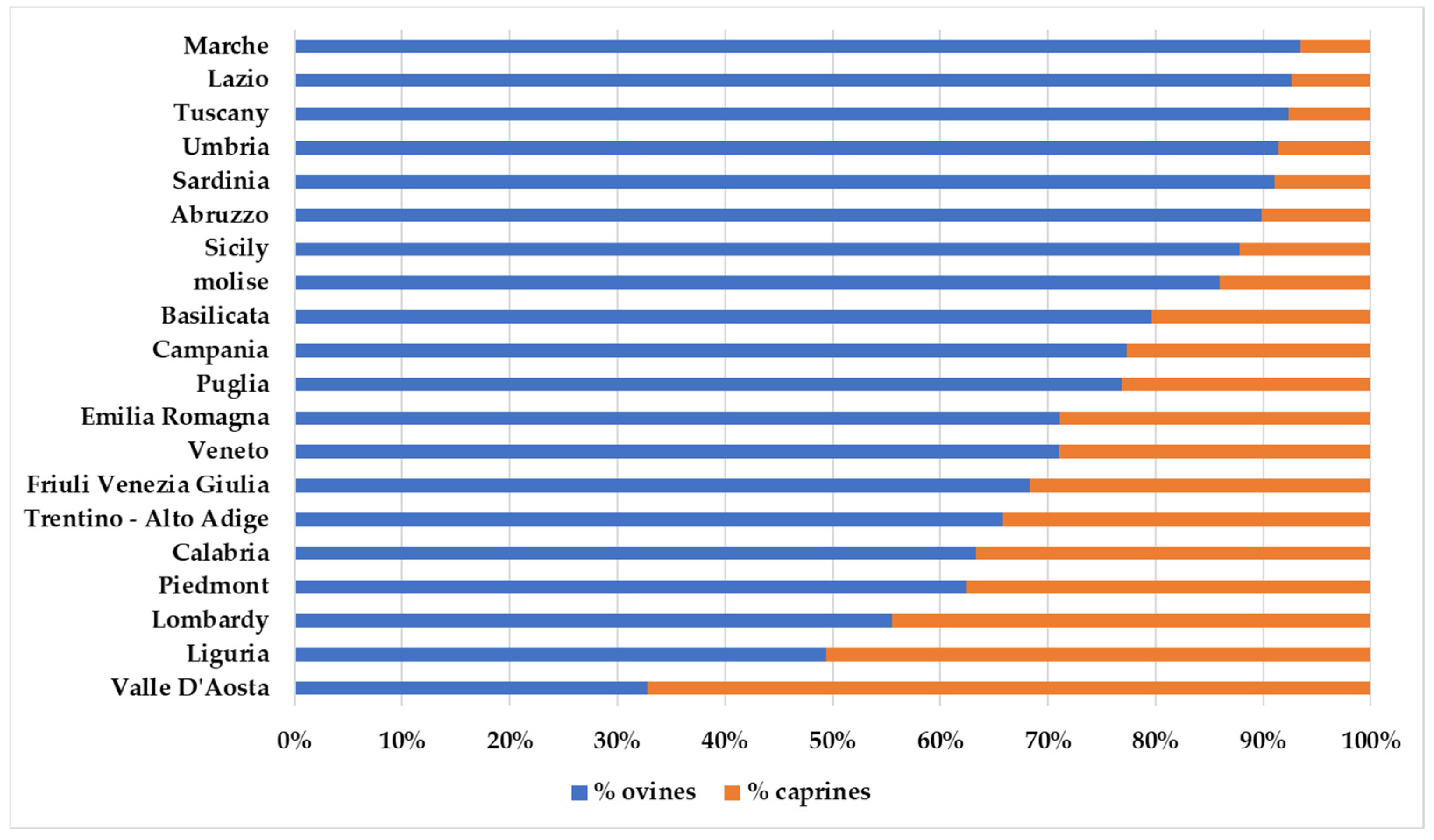

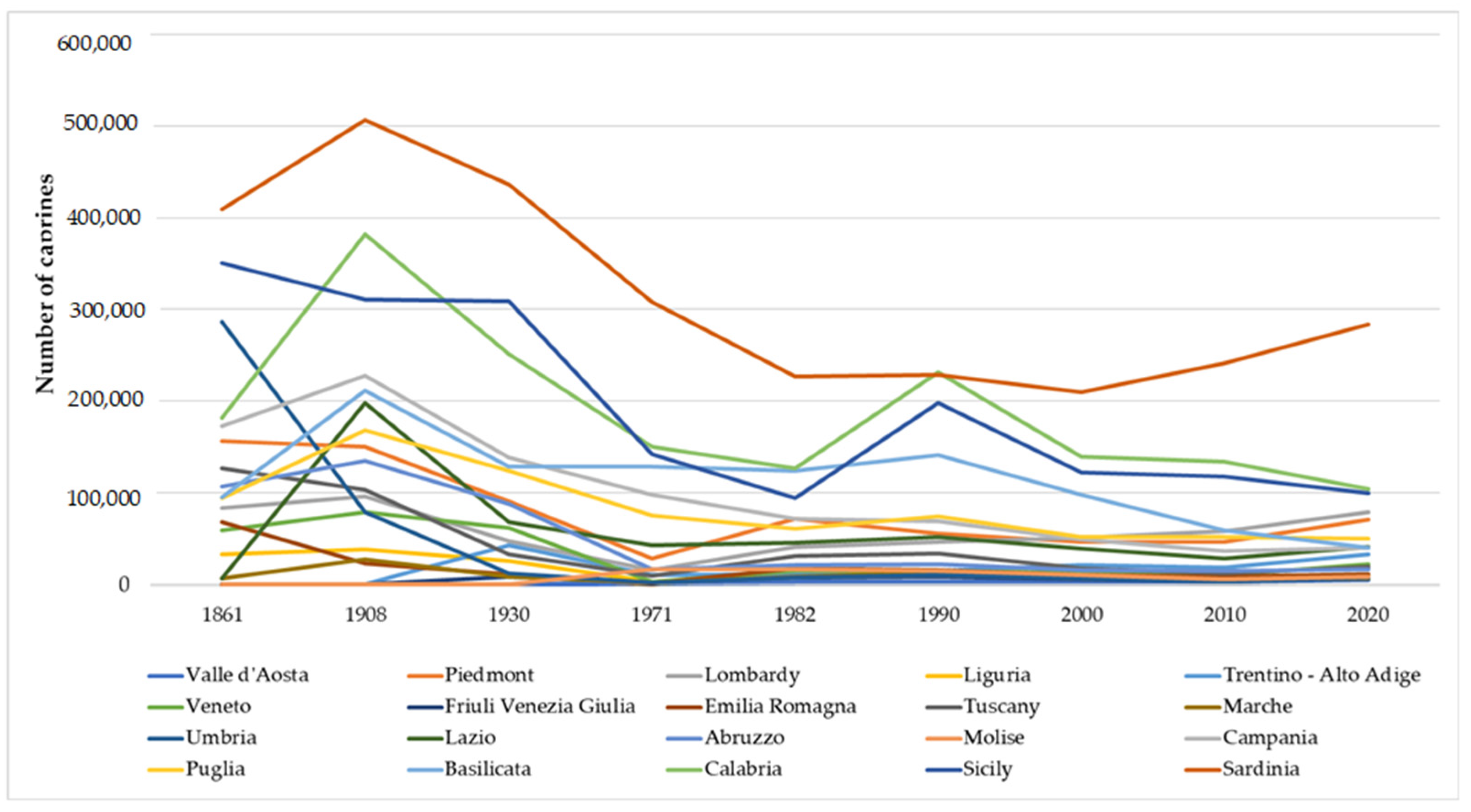

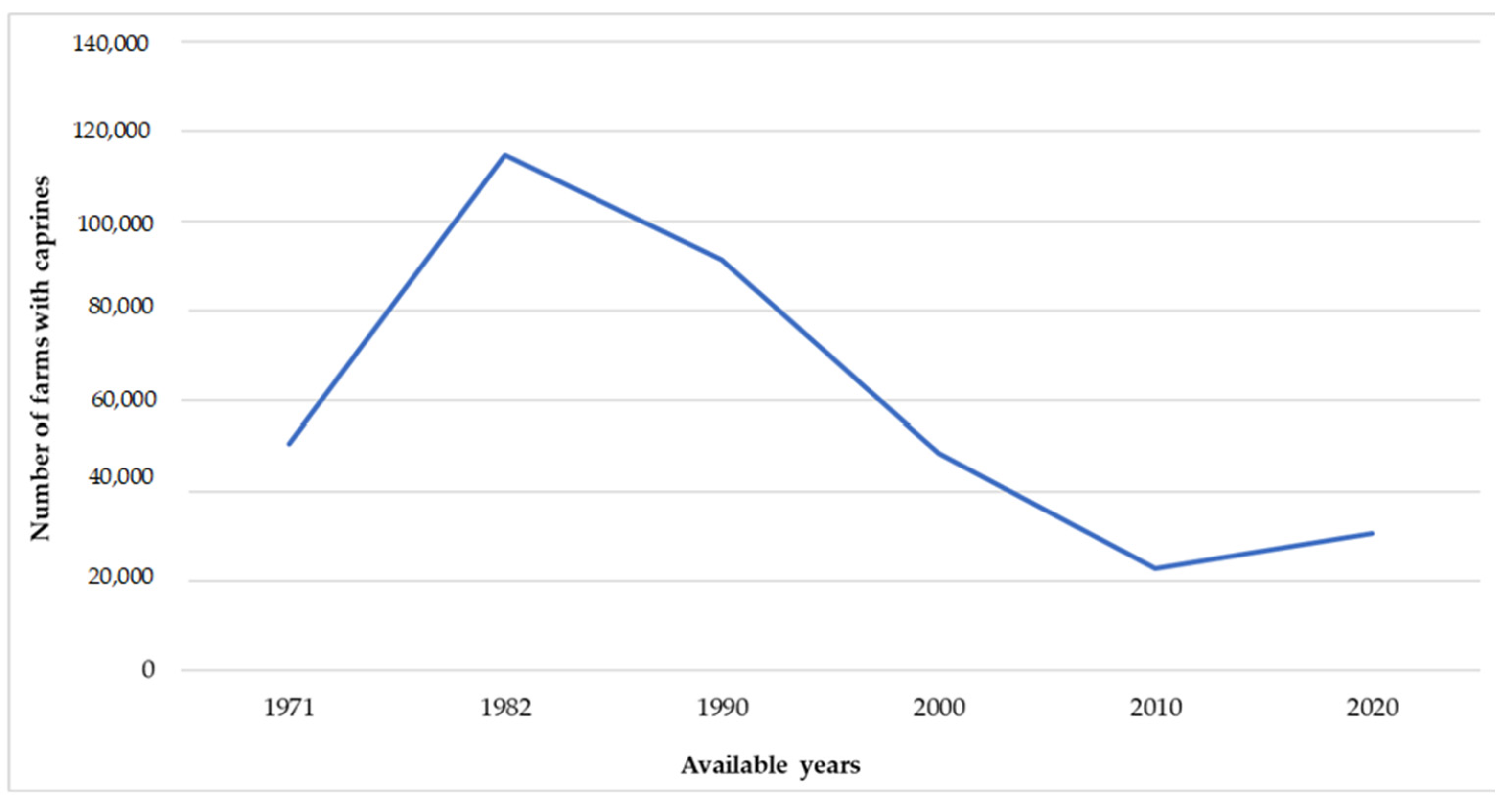

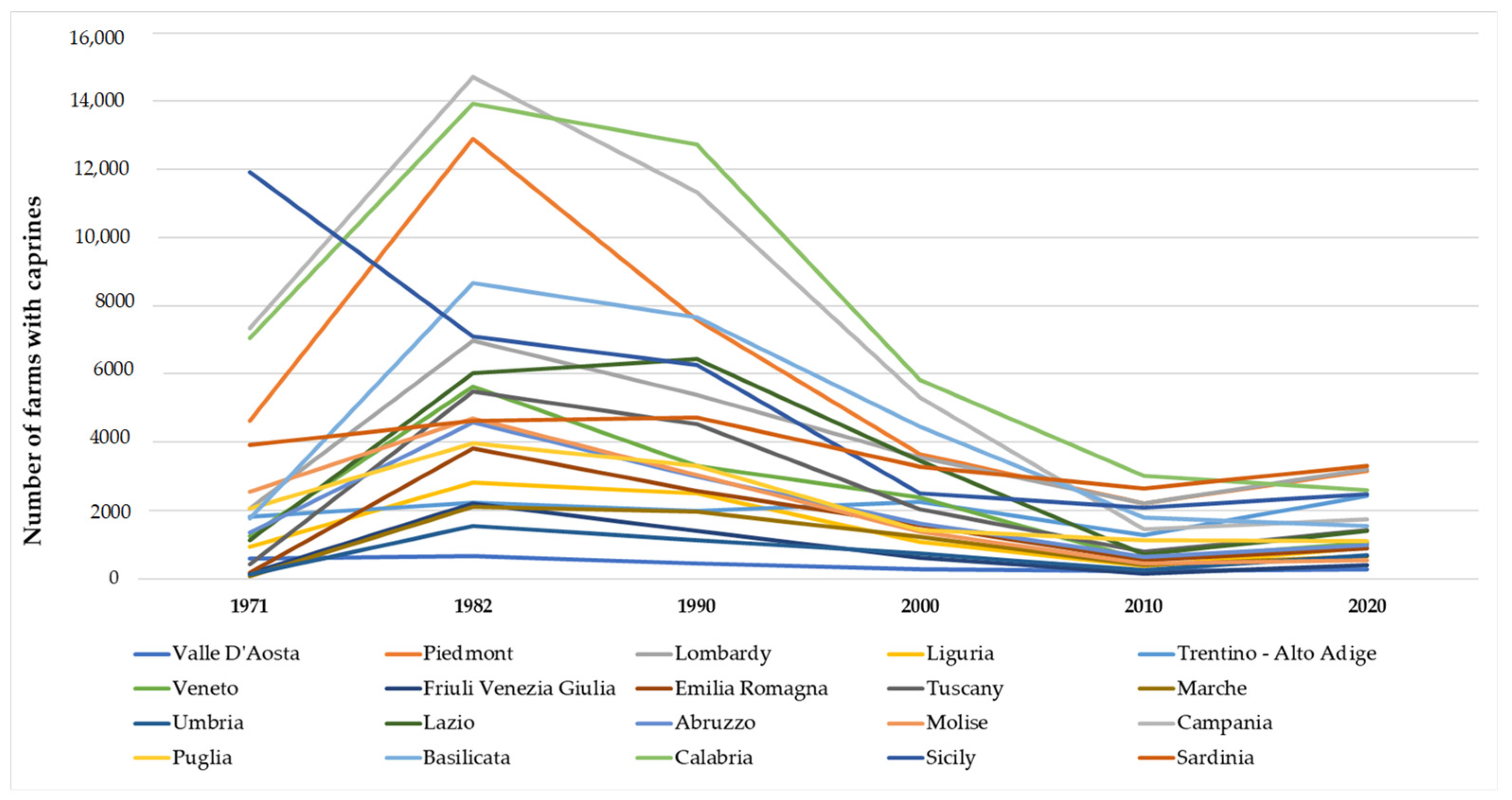

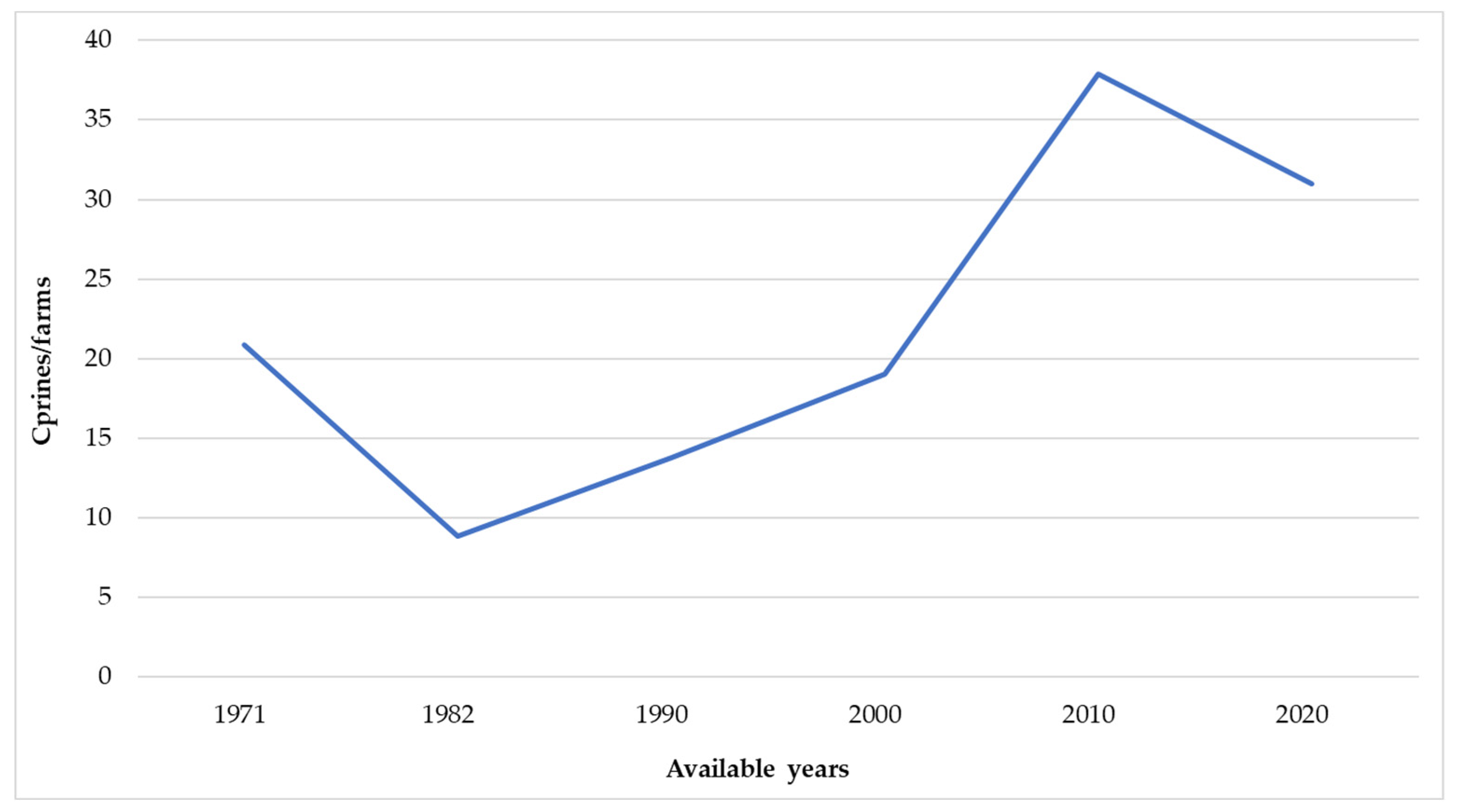

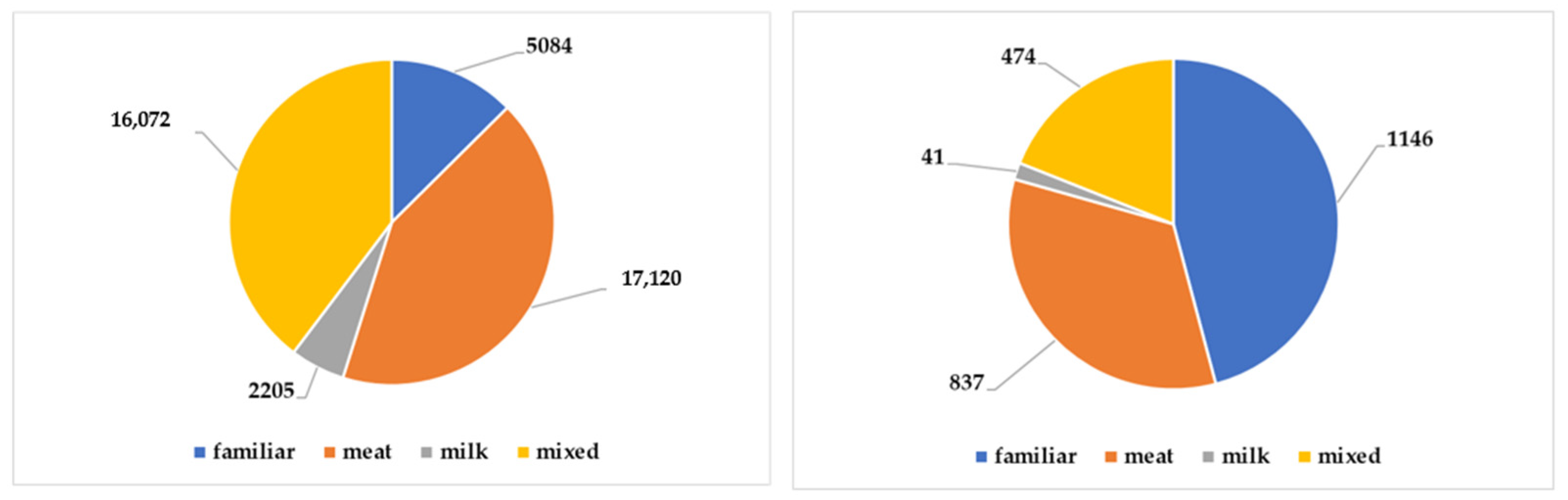

3.1. The Italian Goat Sector

- The Current Situation

- Farms with less than 10 animals are present in Marche, Liguria, Friuli, Veneto, Emilia Romagna, Tuscany, Valle d’Aosta, and Umbria;

- Farms with a number of goats varying from 11 to 19 in Trentino, Lombardy, Piedmont, Abruzzo, Lazio, and Campania;

- Farms with a number of goats varying from 30 to 40 in Calabria, Molise, and Sicily;

- Farms with more than 40 goats in Puglia, Basilicata, and Sardinia.

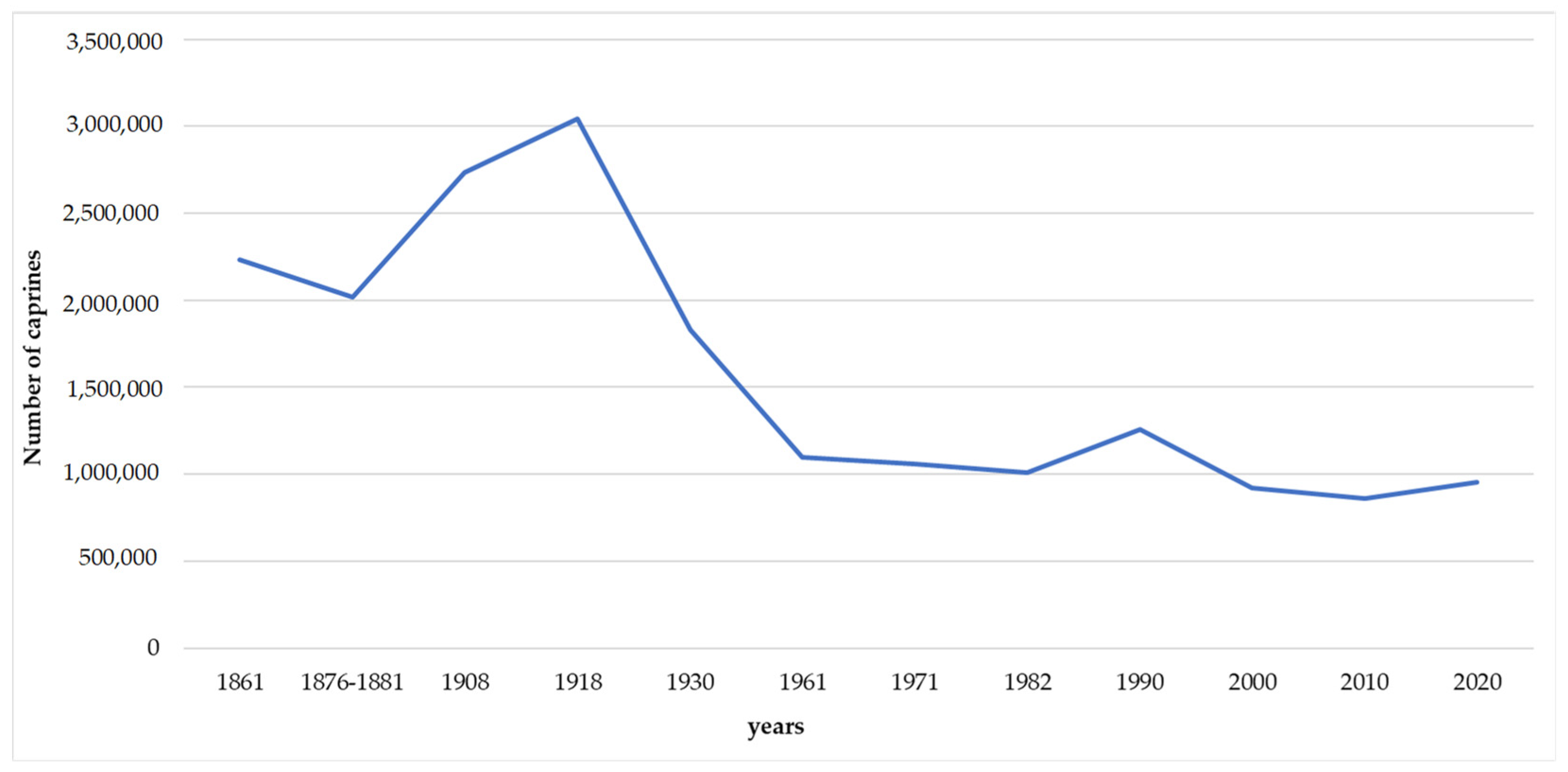

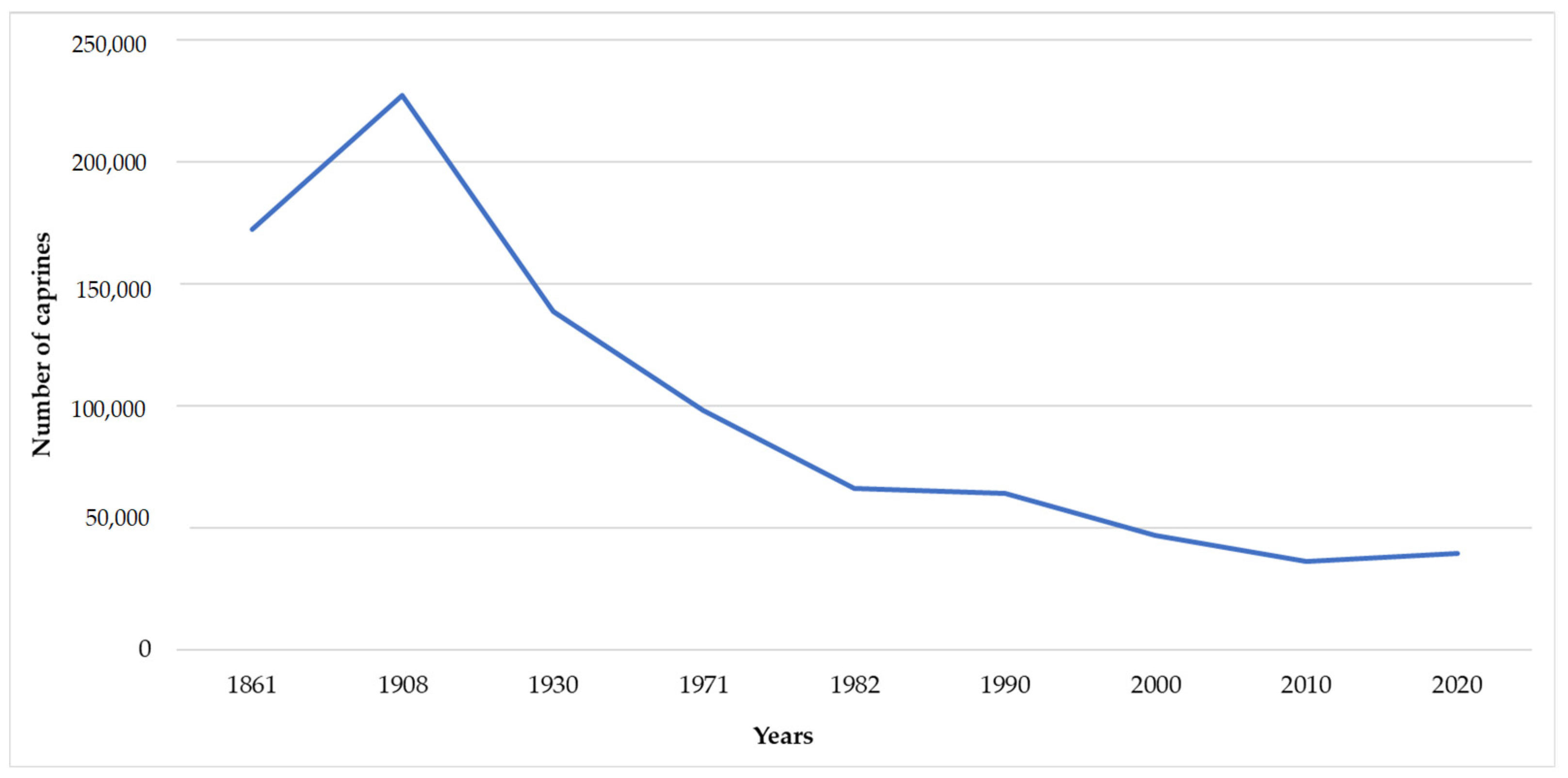

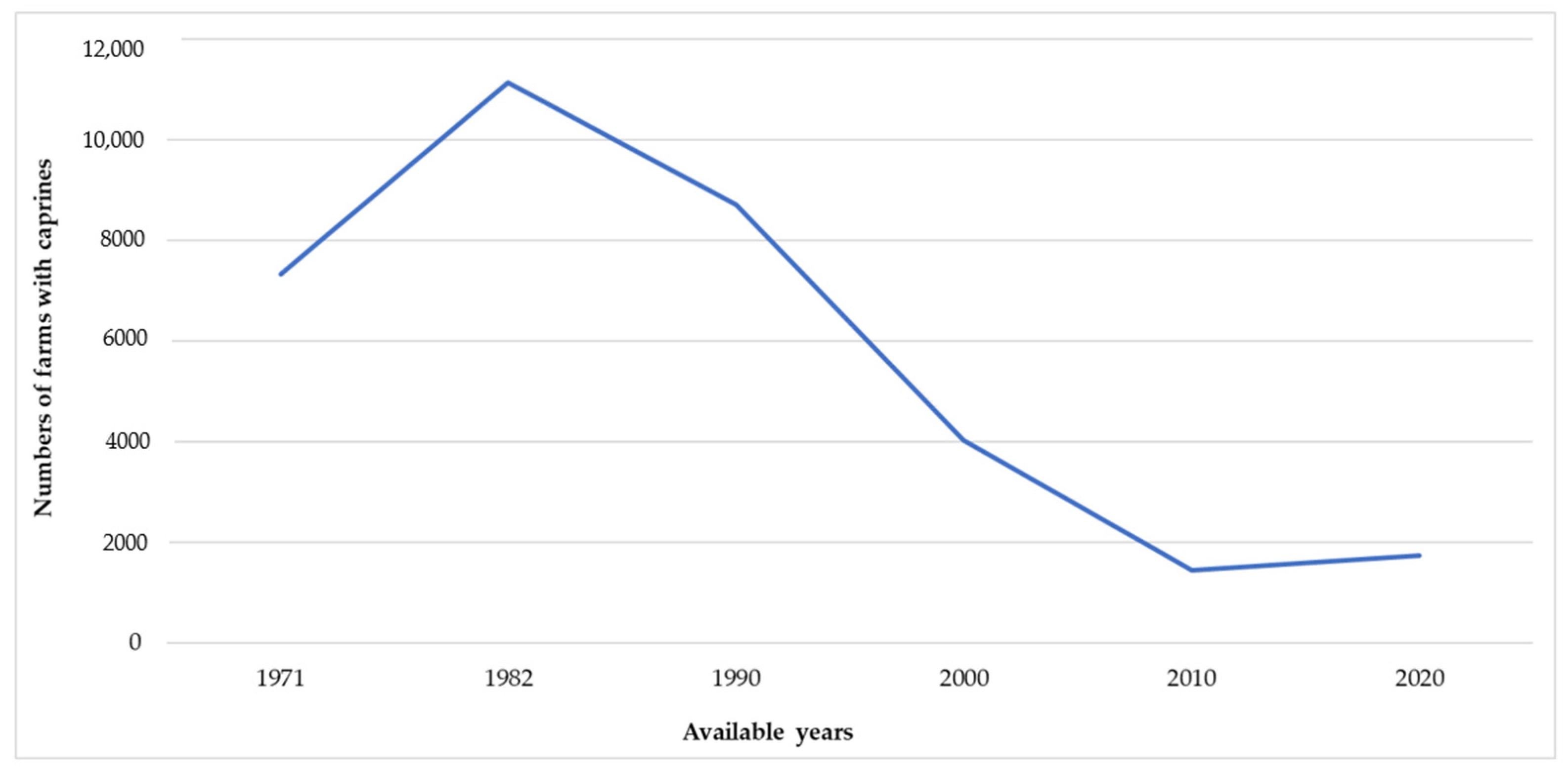

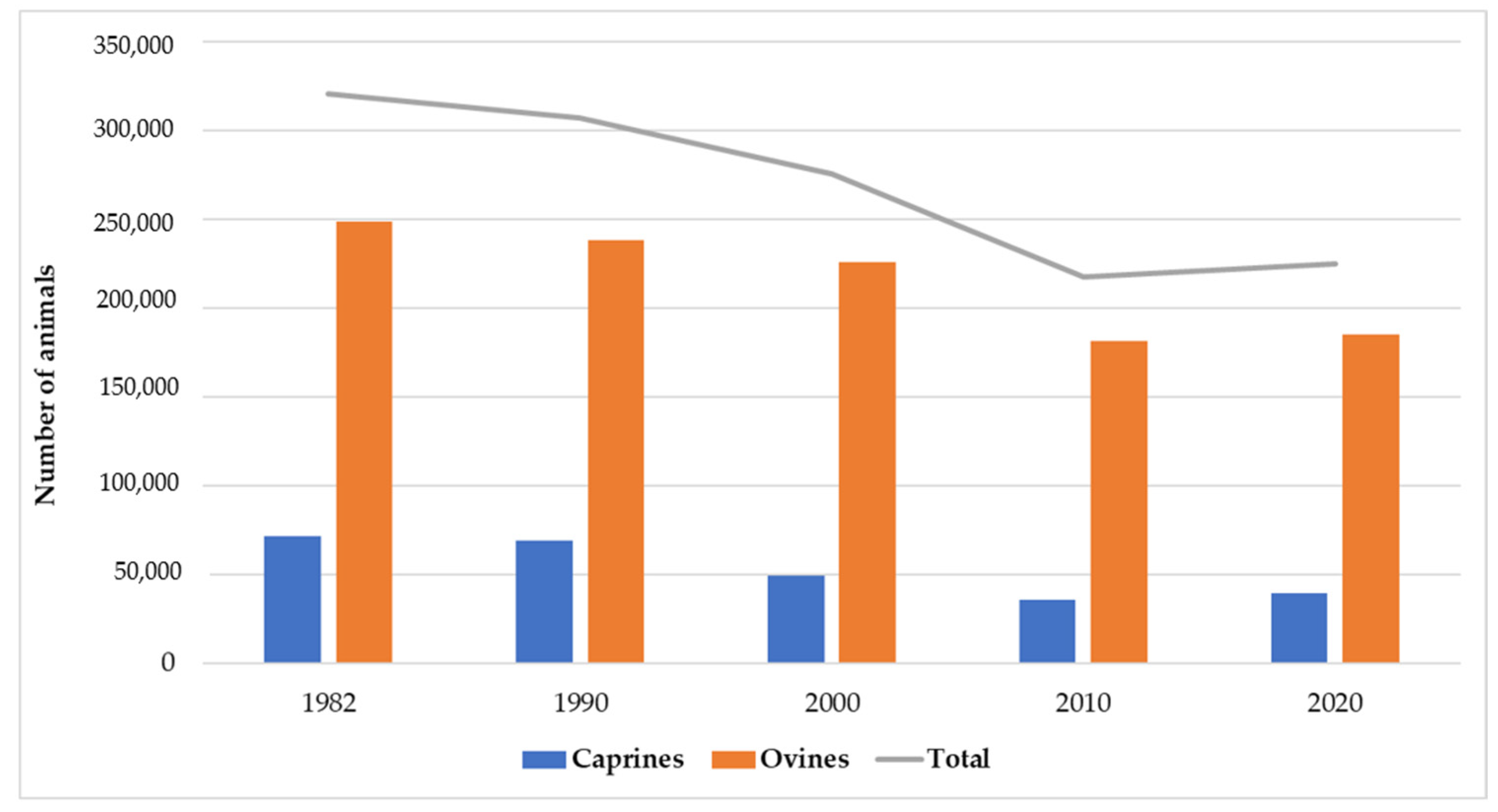

- The Trend over Time

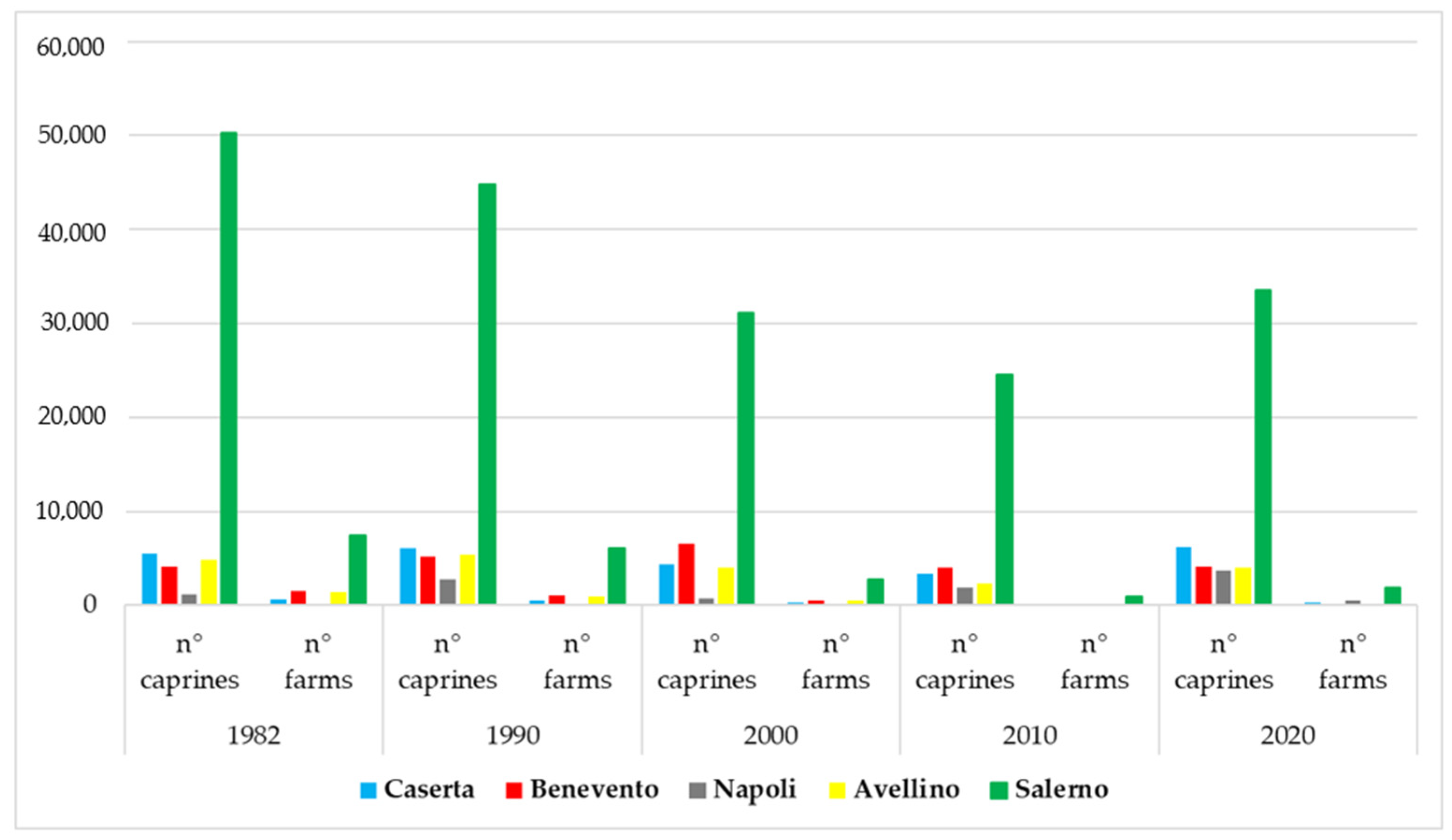

3.2. The Goat Sector of Campania Region

3.3. The Goat Sector between History and Politics

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Niesenbaum, R.A. The Integration of Conservation, Biodiversity, and Sustainability. Sustainability 2019, 11, 4676. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peretti, V.; Ciotola, F.; Iannuzzi, L. Characterization, conservation and sustainability of endangered animal breeds in Campania (Southern Italy). Nat. Sci. 2013, 5, 9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Regolamento Regionale 3 July 2012, n. 6-Regolamento di Attuazione Dell’articolo n. 33 Della Legge Regionale 19 Gennaio 2007, n. 1 (Disposizioni per la Formazione del Bilancio Annuale e Pluriennale Della Regione Campania-Legge Finanziaria Regionale 2007), per la Salvaguardia Delle Risorse Genetiche Agrarie a Rischio di Estinzione. Available online: https://www.regione.campania.it/normativa/item.php?pgCode=G19I238R118&id_doc_type=3&id_tema=1 (accessed on 30 January 2024).

- Law 1st December 2015, n. 194. Disposizioni per la Tutela e la Valorizzazione Della Biodiversità di Interesse Agricolo e Alimentare. Available online: https://www.normattiva.it/uri-res/N2Ls?urn:nir:stato:legge:2015;194 (accessed on 30 January 2024).

- Rubino, R. L’allevamento della Capra. In Guida Pratica Alla Progettazione, Realizzazione e Gestione di un Allevamento Caprine; Ars Grafica: Villa d’Agri, Italy, 1990. [Google Scholar]

- Lauvergne, J.J.; Renieri, C.; Pieramati, C. Populations Traditionnelles et Premières Races Standardisées D’ovicaprinae Dans le Bassin Méditerranéen; INRA: Paris, France, 1988. [Google Scholar]

- Amills, M.; Capote, J.; Tosser-Klopp, G. Goat domestication and breeding: A jigsaw of historical, biological and molecular data with missing pieces. Anim. Genet. 2017, 48, 631–644. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cortellari, M.; Barbato, M.; Talenti, A.; Bionda, A.; Carta, A.; Ciampolini, R.; Ciani, E.; Crisá, A.; Frattini, S.; Lasagna, E.; et al. The climatic and genetic heritage of Italian goat breeds with genomic SNP data. Sci. Rep. 2021, 11, 10986. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cañón, J.; García, D.; García-Atance, M.A.; Obexer-Ruff, G.; Lenstra, J.A.; Ajmone-Marsan, P.; Dunner, S.; Econogene Consortium. Geographical partitioning of goat diversity in Europe and the Middle East. Anim. Genet. 2006, 37, 327–334. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Di Trana, A.; Sepe, L.; Di Gregorio, P.; Di Napoli, M.A.; Giorgio, D.; Caputo, A.R.; Claps, S. The role of local sheep and goat breeds and their products as a tool for sustainability and safeguard of the Mediterranean environment. In The Sustainability of Agro-Food and Natural Resource Systems in the Mediterranean Basin; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2015; pp. 77–112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iommelli, P.; Infascelli, L.; Tudisco, R.; Capitanio, F. The Italian Cilentana goat breed: Productive performances and economic perspectives of goat farming in marginal areas. Trop. Anim. Health Prod. 2022, 54, 304. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Esposito, G.; Iommelli, P.; Infascelli, L.; Raffrenato, E. Traditional Sources of Ingredients for the Food Industry: Animal Sources. In Sustainable Food Science A Comprehensive Approach; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2023; pp. 7–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cerrato, M.; Benincasa, G.; Iasi, A.; Pergola, M. Animal Husbandry in the Cilento, Vallo di Diano and Alburni National Park: An Economic-Structural Analysis for the Protection and Enhancement of the Territory and Local Resources. Sustainability 2023, 15, 7863. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- NLR. Anagrafe Nazionale Zootecnica—Statistiche. Ministry of Health. 2023. Available online: https://www.vetinfo.it/j6_statistiche/#/ (accessed on 28 January 2024).

- Agostini, A. Capre e Boschi; Arti Grafiche F.lli Iacelli: Rome, Italy, 1931. [Google Scholar]

- National Pastoral Association (NPA). Indagine Nazionale su Alcuni Aspetti Degli Allevamenti e Delle Produzioni Caprine; Ministero Dell’agricoltura e Delle Foreste: Rome, Italy, 1971.

- ISTAT. Censimento Agricoltura. 1982. Available online: http://dati-censimentoagricoltura.istat.it/Index.aspx (accessed on 15 January 2024).

- ISTAT. Censimento Agricoltura. 1990. Available online: http://dati-censimentoagricoltura.istat.it/Index.aspx (accessed on 15 January 2024).

- ISTAT. Censimento Agricoltura. 2000. Available online: http://dati-censimentoagricoltura.istat.it/Index.aspx (accessed on 15 January 2024).

- ISTAT. Censimento Agricoltura. 2010. Available online: http://dati-censimentoagricoltura.istat.it/Index.aspx (accessed on 20 January 2024).

- ISTAT. Censimento Agricoltura. 2020. Available online: http://dati-censimentoagricoltura.istat.it/Index.aspx (accessed on 28 January 2024).

- Plieninger, T.; Höchtl, F.; Spek, T. Traditional land-use and nature conservation in European rural landscapes. Environ. Sci. Policy 2006, 9, 317–321. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Casasús, I.; Bernués, A.; Sanz, A.; Villalba, D.; Riedel, J.L.; Revilla, R. Vegetation dynamics in Mediterranean forest pastures as affected by beef cattle grazing. Agric. Ecosyst. Environ. 2007, 121, 365–370. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Benton, T.G.; Vickery, J.A.; Wilson, J.D. Farmland biodiversity: Is habitat heterogeneity the key? Trends Ecol. Evol. 2003, 18, 182–188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Braghieri, A.; Pacelli, C.; Bragaglio, A.; Sabia, E.; Napolitano, F. The hidden costs of livestock environmental sustainability: The case of Podolian cattle. In The Sustainability of Agro-Food and Natural Resource Systems in the Mediterranean Basin; Vastola, A., Ed.; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2015. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kramer, K.; Groen, T.A.; van Wieren, S.E. The interacting effects of ungulates and fire on forest dynamics: An analysis using the model FORSPACE. For. Ecol. Manag. 2003, 181, 205–222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gautieri, C. Dei Vantaggi e dei Danni Derivanti Dalle Capre in Confronto Alle Pecore; Destefanis: Milan, Italy, 1816. [Google Scholar]

- Weaver, S. The Goat: A Natural and Cultural History; Princeton University Press: Princeton, NJ, USA, 2020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boyazoglu, J.; Hatziminaoglou, I.; Morand-Fehr, P. The role of the goat in society: Past, present and perspectives for the future. Small Rumin. Res. 2005, 60, 13–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mastrelli, C.A. L’incidenza delle invasioni germaniche nelle denominazioni degli animali. In L’uomo di Fronte al Mondo Animale Nell’alto Medioevo; Fondazione Centro Italiano di Studi Sull’alto Medioevo: Spoleto, Italy, 1985. [Google Scholar]

- Bokonij, S. History of Domestic Animals in Central and Eastern Europe; Akadémiai Kiadò: Budapest, Hungary, 1974. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cherubini, G. Agricoltura e Società Rurale nel Medioevo; Sansoni: Firenze, Italy, 1977. [Google Scholar]

- Cardini, L. Praia a Mare. Relazione sugli scavi 1957–1970 dell’Istituto Italiano di Paleontologia Umana. Paletnol. Ital. 1970, 79, 31–57. [Google Scholar]

- Slicher Van Bath, B.H. Storia Agraria Dell’europa Occidentale; Einaudi: Turin, Italy, 1972. [Google Scholar]

- Laguna Sanz, E. Historia del Merino; Impresons: Madrid, Spain, 1986. [Google Scholar]

- Paone, N. La Transumanza: Immagini di una Civiltà; Cosimo Iannone Editore: Isernia, Italy, 1987. [Google Scholar]

- Gaudiani, A. Notizie per il Buon Governo Della Regia Dogana Della Mena Delle Pecore in Puglia; Editrice Apulia: Foggia, Italy, 1981. [Google Scholar]

- Regio Decreto-Legge 30 December 1923, n. 3267. Riordinamento e Riforma Della Legislazione in Materia di Boschi e di Terreni Montani. Available online: https://www.normattiva.it/uri-res/N2Ls?urn:nir:stato:regio.decreto:1923;3267#:~:text=REGIO%20DECRETO-LEGGE%2030%20dicembre%201923%2C%20n.%203267%20Riordinamento,%28023U3267%29%20note%3A%20Entrata%20in%20vigore%20del%20provvedimento%3A%2001%2F06%2F1924 (accessed on 15 December 2023).

- Modificazioni al Regio Decreto-Legge 16 Gennaio 1927, n. 100, Convertito Nella Legge 16 Giugno 1927, n. 1123, con cui fu Istituita una Tassa Speciale Sugli Animali Caprini. Available online: https://storia.camera.it/regno/lavori/PDF/RI_LEG28/unica/01926.pdf (accessed on 15 December 2023).

- Bevilacqua, P. Storia Dell’agricoltura Italiana in età Contemporanea; Marsilio: Venezia, Italy, 1990. [Google Scholar]

- Corti, P. Inchiesta Zanardelli Sulla Basilicata (1902); Einaudi: Turin, Italy, 1976. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gramignani, E. Zootecnia Irpina. Economia Irpina. Rassegna della Camera di Commercio, Industria e Agricoltura di Avellino 1965, 11/12, 5–26. [Google Scholar]

- Carena, A. Realtà e Sviluppo Dell’agricoltura Nelle Aree Interne del Mezzogiorno; De Santi: Potenza, Italy, 1977. [Google Scholar]

- Fotticchia, N. Problemi Dell’agricoltura Meridionale; Cassa Perqua il Mezzogiorno: Roma, Italy, 1953; Volume 2. [Google Scholar]

- Rubino, R. Il Mezzogiorno zootecnico. Quaderni–zootecnia, INEA, 1, 1991.

- Montemurro, O. La zootecnia nelle zone collinari del Mezzogiorno continentale. La. Razza Bruna Alp. 1984, 1. [Google Scholar]

- Matassino, D. Sviluppo zootecnico delle aree interne della Basilicata. L’informatore Zootec. 1982, 25, 58. [Google Scholar]

- Matassino, D.; Cosentini, E.; Freschi, P. Primo contributo alla conoscenza del sistema caprino in Basilicata. Il Vergaro 1987, 6, 2. [Google Scholar]

- Rubino, R.; Nardone, A.; Carena, A.; Matassino, D. I sistemi produttivi ovini e caprini nell’Italia meridionale. Prod. Anim. 1983, 2, 125. [Google Scholar]

- Matassino, D.; Rubino, R. I sistemi produttivi zootecnici nelle aree interne meridionali. La. Quest. Agrar. 1984, 16, 121. [Google Scholar]

- Matassino, D. Le razze zootecniche autoctone. Agric. Campania 1986, 10, 4. [Google Scholar]

- Ramunno, L.; Montemurro, N.; Muscillo, F.; Cosentino, E. Stato delle ricerche sul sistema zootecnico nelle Comunità montane “Melandro” e “Alto Sauro Camastra”. Produzione lattea, misure somatiche e caratteri fanerotici dei caprini. In Proceedings of the Stato Delle Ricerche Sulle Aree Marginali: Le Comunità Montane “Alto Sauro Camastra” e “Melandro”, CNR, Potenza, Italy, 22 February 1986. [Google Scholar]

- Matassino, D. La conoscenza del territorio e delle risorse condizione indispensabile per interventi programmatici in zootecnia. CISL Campania 1978, 19, 3–4. [Google Scholar]

- Matassino, D. Pim: Per cambiare rotta negli allevamenti del sud. L’Allevatore 1983, 39, 8. [Google Scholar]

- Matassino, D. Come programmare le produzioni animali in ambienti appenninici meridionali. L’Informatore Agrar. 1985, 41, 73. [Google Scholar]

- Matassino, D. Salvaguardia e recupero delle popolazioni autoctone italiane. In Salvaguardia genetica e prospettive per il recupero zootecnico di razze e popolazioni autoctone italiane. Atti Convegno CNR. L’Informatore Zootec. 1982, 29, 43. [Google Scholar]

- Matassino, D.; Lauvergne, J.J.; Renieri, C.; Ramunno, L.; Montemurro, N.; Rubino, R.; Valfrè, F.; Cosentino, E. Ricerche preliminari sul profilo genetico visibile di alcune popolazioni caprine autoctone allevate in tre regioni dell’Italiana meridionale. Prod. Anim 1984, 3, 71. [Google Scholar]

- Matassino, D. L’animale autoctono quale bene culturale. In Atti Della Tavola Rotonda Biodiversità Genetiche Autoctone Quali Risorse Economiche del Territorio; Pacini Editore: Pisa, Italy, 1997; pp. 43–58. [Google Scholar]

- Ministero dell’Agricoltura e delle foreste. Proposta di Piano Nazionale di Settore per gli Ovini e i Caprine; Rome, Italy, 1988.

- Regolamento (UE) 2016/1012 del Parlamento Europeo e del Consiglio, Dell’8 Giugno 2016, Relativo Alle Condizioni Zootecniche e Genealogiche Applicabili Alla Riproduzione, Agli Scambi Commerciali e All’ingresso nell’Unione di Animali Riproduttori di Razza Pura, di Suini Ibridi Riproduttori e del Loro Materiale Germinale, che Modifica il Regolamento (UE) n. 652/2014, le Direttive 89/608/CEE e 90/425/CEE del Consiglio, e che Abroga Taluni atti in Materia di Riproduzione Animale («Regolamento Sulla Riproduzione Degli Animali») (Testo Rilevante ai fini del SEE). Available online: https://eur-lex.europa.eu/legal-content/IT/TXT/?uri=CELEX:32016R1012#:~:text=Regolamento%20%28UE%29%202016%2F1012%20del%20Parlamento%20europeo%20e%20del,degli%20animali%C2%BB%29%20%28Testo%20rilevante%20ai%20fini%20del%20SEE%29 (accessed on 20 December 2023).

- Decreto Legislativo 11 May 2018, n. 52. Disciplina Della Riproduzione Animale in Attuazione Dell’articolo 15 Della Legge 28 July 2016, n. 154. Available online: https://www.normattiva.it/uri-res/N2Ls?urn:nir:stato:decreto.legislativo:2018;052 (accessed on 20 December 2023).

- Decreto Dirigenziale Della Giunta Regionale Della Campania n. 87 del 18/06/2018. Elenco Regionale Coltivatori Custodi-Sezione Animale: Approvazione Modello di Iscrizione e Avviso Pubblico (Con Allegati). Available online: http://agricoltura.regione.campania.it/biodiversita/doc/DRD_87-18-06-18.pdf (accessed on 20 January 2024).

- Assessorato Agricoltura Regione Campania. AMiCA Project (Azioni a Sostegno Delle Microfiliere Zootecniche per la Valorizzazione Delle Risorse Genetiche Campane Autoctone e Delle Relative Produzioni). Available online: http://agricoltura.regione.campania.it/comunicati/comunicato_04-08-21B.html#:~:text=attivit%C3%A0%20a%20carattere%20informativo%2C%20divulgativo%20e%20dimostrativo%20finalizzate,intesa%20fra%20tutti%20gli%20attori%20delle%20filiere%20coinvolte. (accessed on 30 January 2024).

- Assessorato Agricoltura Regione Campania. Progetto Relativo Alla Conservazione e Valorizzazione Delle Popolazioni Locali e delle Razze Autoctone Campane e del Loro Habitat. Available online: http://agricoltura.regione.campania.it/comunicati/comunicato_17-02-21.html (accessed on 15 January 2024).

- Istituto di Servizi per il Mercato Agricolo Alimentare (ISMEA). Ovicaprini-Novembre 2022. Available online: https://www.ismeamercati.it/flex/files/1/9/8/D.a5463f28d07a5333858e/Scheda_Ovicaprino_2022.pdf (accessed on 20 January 2024).

- Cerrato, M.; Iasi, A.; Di Bennardo, F.; Pergola, M. Evaluation of the Economic and Environmental Sustainability of Livestock Farms in Inland Areas. Agriculture 2023, 13, 1708. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Istituto di Servizi per il Mercato Agricolo Alimentare (ISMEA). Tendenze e Dinamiche Recenti Ovicaprini–Maggio 2023. Available online: https://www.ismeamercati.it/flex/cm/pages/ServeBLOB.php/L/IT/IDPagina/12631 (accessed on 20 January 2024).

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Cerrato, M.; Pergola, M.; Ruggiero, G. Can Sustainability and Biodiversity Conservation Save Native Goat Breeds? The Situation in Campania Region (Southern Italy) between History and Regional Policy Interventions. Sustainability 2024, 16, 3157. https://doi.org/10.3390/su16083157

Cerrato M, Pergola M, Ruggiero G. Can Sustainability and Biodiversity Conservation Save Native Goat Breeds? The Situation in Campania Region (Southern Italy) between History and Regional Policy Interventions. Sustainability. 2024; 16(8):3157. https://doi.org/10.3390/su16083157

Chicago/Turabian StyleCerrato, Michele, Maria Pergola, and Gianni Ruggiero. 2024. "Can Sustainability and Biodiversity Conservation Save Native Goat Breeds? The Situation in Campania Region (Southern Italy) between History and Regional Policy Interventions" Sustainability 16, no. 8: 3157. https://doi.org/10.3390/su16083157

APA StyleCerrato, M., Pergola, M., & Ruggiero, G. (2024). Can Sustainability and Biodiversity Conservation Save Native Goat Breeds? The Situation in Campania Region (Southern Italy) between History and Regional Policy Interventions. Sustainability, 16(8), 3157. https://doi.org/10.3390/su16083157