Understanding and Enhancing Food Conservation Behaviors and Operations

Abstract

1. Introduction

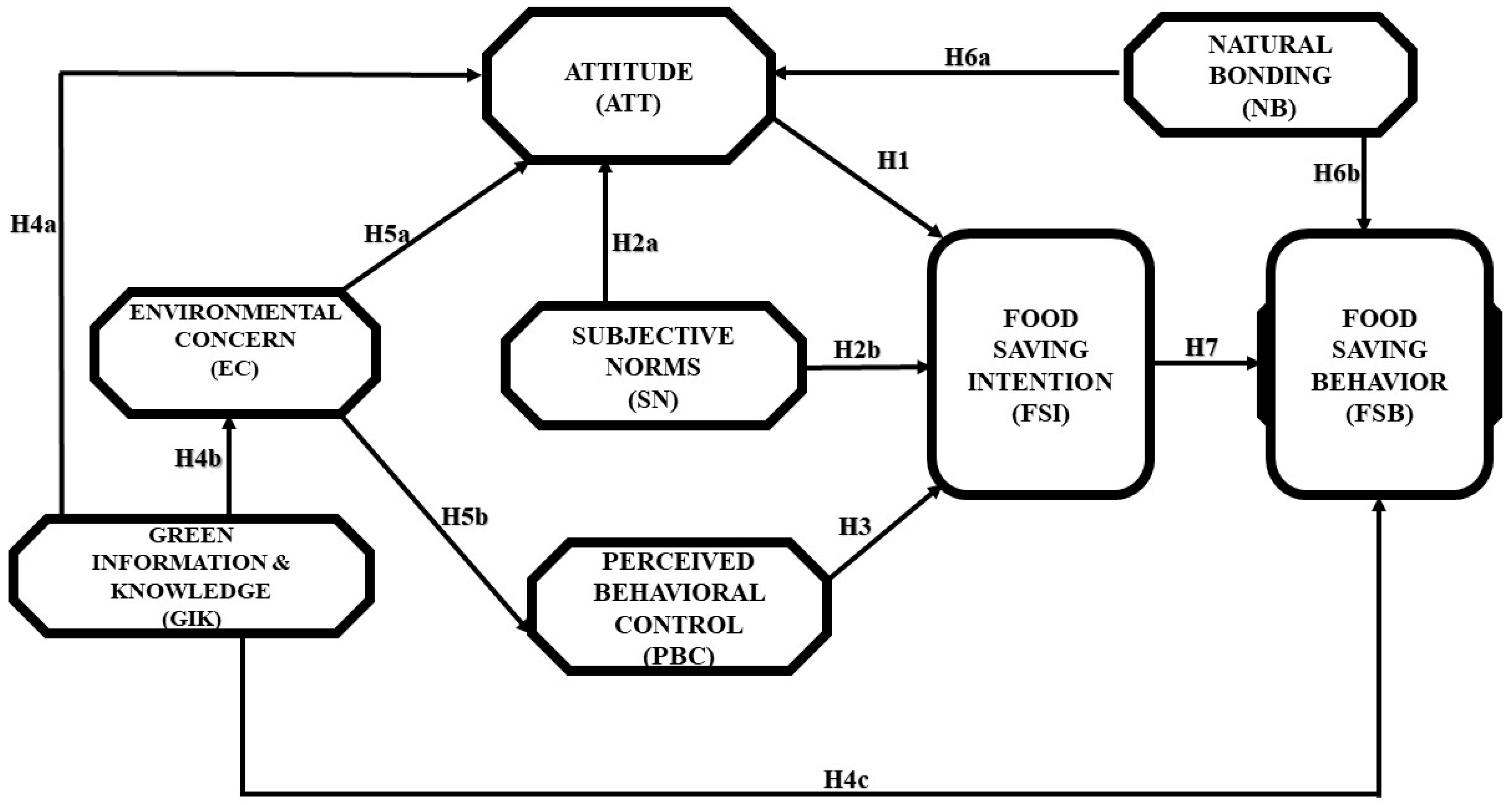

2. Review of Relevant Literature and Development of Hypotheses

2.1. Theory of Planned Behavior

2.2. Model Development

2.3. Green Information and Knowledge

2.4. Environmental Concerns

2.5. Natural Bonding

2.6. Intention Behavior

3. Data and Methods

3.1. Data Collection and Sampling

3.2. Constructs Measurements

3.3. Statistical Analysis

4. Study Results and Discussion

4.1. Respondents’ Information

4.2. Testing Measurement Models

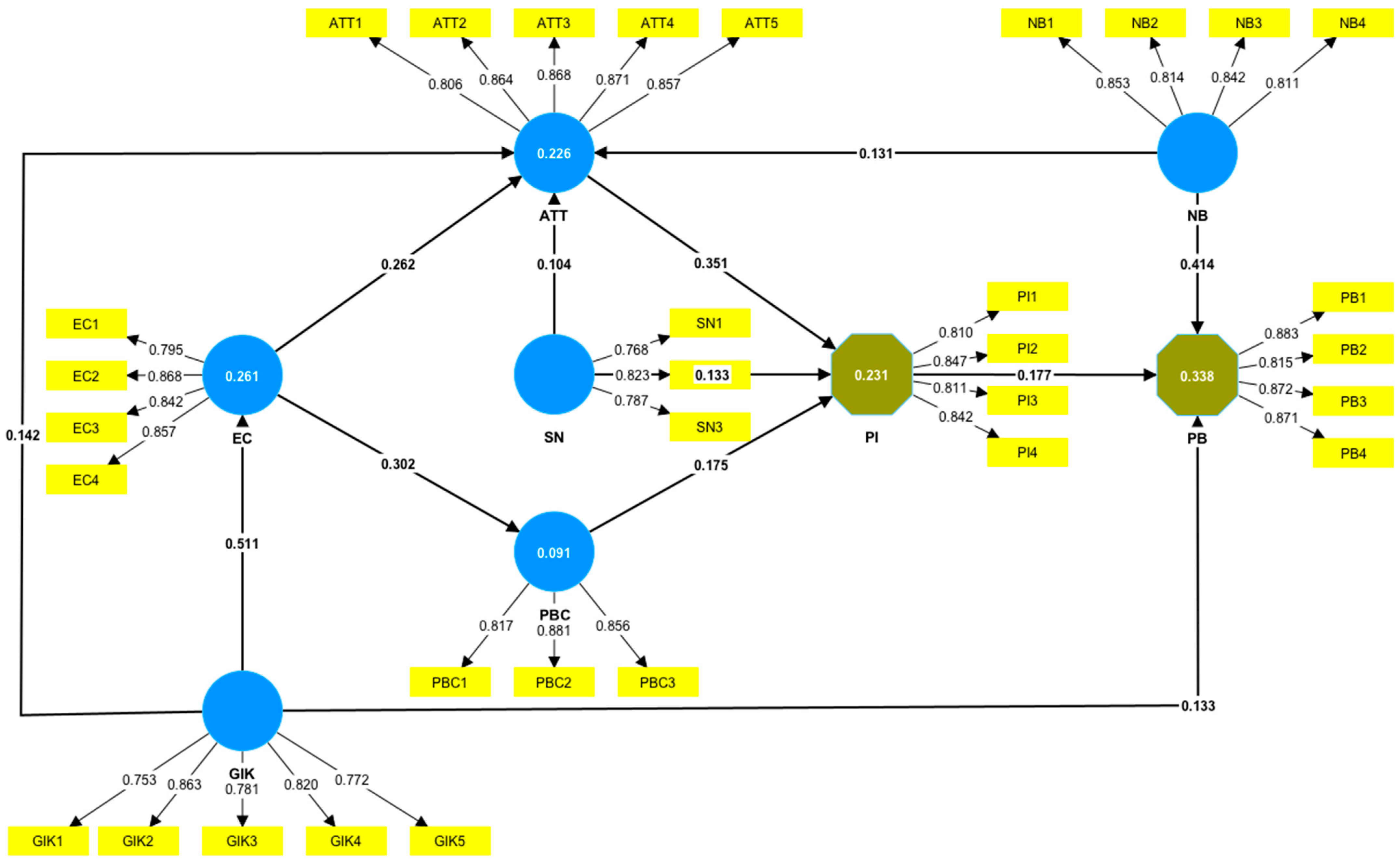

4.3. Structural Model Assessment

4.4. Hypotheses Results and Validation

4.5. Mediating Roles

4.6. Discussion

5. Conclusions and Policy Implications

5.1. Conclusions

5.2. Theoretical and Practical Implications

5.2.1. Theoretical Implications

5.2.2. Practical and Managerial Implications

5.3. Limitations and Future Research Direction

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A. Measurement Items

| Variable | Measurement Item | Modified Source |

| Attitude | ATT1: I think the idea of saving food is very positive ATT2: I think saving food is useful to solve environmental problems ATT3: For me, saving food is pleasant. ATT4: For me, saving food is a wise choice ATT5: I feel saving food is rewarding | [59,60] |

| Perceived Behavioral Control | PBC1: I have the ability to save food PBC2: I feel it is easy and convenient to save food PBC3: I am confident that if I want, I can save food | [59,60] |

| Subjective norms | SN1: People whose opinions I value would prefer me to save food SN2: Most people who are important to me would want me to save food SN5: My family and friends think I should save food | [59,60] |

| Green Information & Knowledge | GIK1: I know more about food saving GIK2: I know that saving food is important GIK3: I am very knowledgeable about food-saving issues GIK4: I know about the Sustainable Development Goals GIK5: I have an idea of how to save food | [60,61,62] |

| Environmental Concern | EC1: I save food because of the effect of food waste on the environment. EC2: I am concerned about the environment, so I don’t waste food EC3: Whenever I am eating, I am conscious about the environment EC4: I save food because its wastage is harmful to other people and the environment | [61] |

| Natural bonding | NB1: My love for nature makes me save food NB2: I owe an obligation to nature when I save food NB3: I think saving food means saving nature NB4: I will be troubled if the environment is harmed by not saving food | [30] |

| Food saving intention | FSI1: I intend to save food in the near future FSI2: I am inclined to save food FSI3: I am willing to save food when the need be FSI4: I will save food for a sustainable environment | [3,26,47] |

| Green furniture purchase behavior | FSB1: I save food often FSB2: I have food storage equipment FSB3: I cook and buy what I can eat FSB4: I always recommend food-saving practices to others when asked | [3,26,47] |

References

- Prelez, J.; Wang, F.; Shreedhar, G. For the Love of Money and the Planet: Experimental Evidence on Co-Benefits Framing and Food Waste Reduction Intentions. Resour. Conserv. Recycl. 2023, 192, 106904. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maragkaki, A.; Malliaros, N.G.; Sampathianakis, I.; Lolos, T.; Tsompanidis, C.; Manios, T. Evaluation of Biodegradability of Polylactic Acid and Compostable Bags from Food Waste under Industrial Composting. Sustainability 2023, 15, 15963. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, H.; Chen, K.; Ma, Z. Interactive Effects of Social Norms and Information Framing on Consumers’ Willingness of Food Waste Reduction Behavior. J. Retail. Consum. Serv. 2023, 75, 103525. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- UNEP. UNEP Food Waste Index Report 2021; UNEP: Nairobi, Kenya, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Wong, C. Food Waste in China and How the Government Is Combating It. Available online: https://earth.org/food-waste-in-china/ (accessed on 14 August 2023).

- Rifat, M.A.; Talukdar, I.H.; Lamichhane, N.; Atarodi, V.; Alam, S.S. Food Safety Knowledge and Practices among Food Handlers in Bangladesh: A Systematic Review. Food Control 2022, 142, 109262. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vatral, C.D.; Quinlan, J.J. Identification of Barriers to Consumers Adopting the Practice of Not Washing Raw Poultry. Food Control 2021, 123, 107682. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Le, A.T.; Nguyen, M.T.; Vu, H.T.T.; Nguyen Thi, T.T. Consumers’ Trust in Food Safety Indicators and Cues: The Case of Vietnam. Food Control 2020, 112, 107162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Onyeaka, H.; Ghosh, S.; Obileke, K.; Miri, T.; Odeyemi, O.A.; Nwaiwu, O.; Tamasiga, P. Preventing Chemical Contaminants in Food: Challenges and Prospects for Safe and Sustainable Food Production. Food Control 2024, 155, 110040. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jenkins, E.L.; Lukose, D.; Brennan, L.; Molenaar, A.; McCaffrey, T.A. Exploring Food Waste Conversations on Social Media: A Sentiment, Emotion, and Topic Analysis of Twitter Data. Sustainability 2023, 15, 13788. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, H.-H.; Huang, P.-Y. Food Waste and Environmental Sustainability of the Hotel Industry in Taiwan. Sustainability 2023, 15, 15459. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aka, S.; Buyukdag, N. How to Prevent Food Waste Behaviour? A Deep Empirical Research. J. Retail. Consum. Serv. 2021, 61, 102560. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, Y.; Tian, X.; Qin, J.; Li, X.; Liu, G. Decoding the Influence Mechanism of Restaurant Plate Waste Behaviors in Urban China. Resour. Conserv. Recycl. 2023, 196, 107059. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zong, X.; Tian, J.; Zheng, X.; Tong, Z.; She, S.; Sun, Y. Influence of Climate Change Beliefs on Adolescent Food Saving Behavior: Mechanisms Mediating Environmental Concerns. Environ. Dev. Sustain. 2024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, P.; Zhang, D.; Cheng, S. The Effect of Consumer Perception on Food Waste Behavior of Urban Households in China. Sustainability 2020, 12, 5676. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tsai, W.-C.; Chen, X.; Yang, C. Consumer Food Waste Behavior among Emerging Adults: Evidence from China. Foods 2020, 9, 961. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Obuobi, B.; Zhang, Y.; Adu-Gyamfi, G.; Nketiah, E. Households’ Food Waste Behavior Prediction from a Moral Perspective: A Case of China. Environ. Dev. Sustain. 2023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ajzen, I. From Intentions to Actions: A Theory of Planned Behavior. In Action Control; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 1985; pp. 11–39. [Google Scholar]

- Ajzen, I.; Fishbein, M. Understanding Attitudes and Predicting Social Behaviour; Prentice-Hall: Englewood Cliffs, NJ, USA, 1980. [Google Scholar]

- Ajzen, I. The Theory of Planned Behavior. Organ. Behav. Hum. Decis. Process. 1991, 50, 179–211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ajzen, I. Perceived Behavioral Control, Self-Efficacy, Locus of Control, and the Theory of Planned Behavior. J. Appl. Soc. Psychol. 2002, 32, 665–683. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Click, M.A.; Ridberg, R. Saving Food: Food Preservation as Alternative Food Activism. Environ. Commun. 2010, 4, 301–317. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kirmani, M.D.; Fatah Uddin, S.M.; Sadiq, M.A.; Ahmad, A.; Haque, M.A. Food-Leftover Sharing Intentions of Consumers: An Extension of the Theory of Planned Behavior. J. Retail. Consum. Serv. 2023, 73, 103328. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aydin, H.; Aydin, C. Investigating Consumers’ Food Waste Behaviors: An Extended Theory of Planned Behavior of Turkey Sample. Clean. Waste Syst. 2022, 3, 100036. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jabeen, F.; Dhir, A.; Islam, N.; Talwar, S.; Papa, A. Emotions and Food Waste Behavior: Do Habit and Facilitating Conditions Matter? J. Bus. Res. 2023, 155, 113356. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lourenco, C.E.; Porpino, G.; Araujo, C.M.L.; Vieira, L.M.; Matzembacher, D.E. We Need to Talk about Infrequent High Volume Household Food Waste: A Theory of Planned Behaviour Perspective. Sustain. Prod. Consum. 2022, 33, 38–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, L.; Wang, S.; Li, J.; Li, H. Application of the Extended Theory of Planned Behavior to Understand Individual’s Energy Saving Behavior in Workplaces. Resour. Conserv. Recycl. 2017, 127, 107–113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shi, H.; Wang, S.; Zhao, D. Exploring Urban Resident’s Vehicular PM2.5 Reduction Behavior Intention: An Application of the Extended Theory of Planned Behavior. J. Clean. Prod. 2017, 147, 603–613. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yadav, R.; Pathak, G.S. Determinants of Consumers’ Green Purchase Behavior in a Developing Nation: Applying and Extending the Theory of Planned Behavior. Ecol. Econ. 2017, 134, 114–122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nketiah, E.; Song, H.; Cai, X.; Adjei, M.; Obuobi, B.; Adu-Gyamfi, G.; Cudjoe, D. Predicting Citizens’ Recycling Intention: Incorporating Natural Bonding and Place Identity into the Extended Norm Activation Model. J. Clean. Prod. 2022, 377, 134425. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hamzah, M.I.; Tanwir, N.S. Do Pro-Environmental Factors Lead to Purchase Intention of Hybrid Vehicles? The Moderating Effects of Environmental Knowledge. J. Clean. Prod. 2021, 279, 123643. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saari, U.A.; Damberg, S.; Frömbling, L.; Ringle, C.M. Sustainable Consumption Behavior of Europeans: The Influence of Environmental Knowledge and Risk Perception on Environmental Concern and Behavioral Intention. Ecol. Econ. 2021, 189, 107155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, M.; Peng, L.; Shang, Y.; Zhao, X. Green Technology Progress and Total Factor Productivity of Resource-Based Enterprises: A Perspective of Technical Compensation of Environmental Regulation. Technol. Forecast. Soc. Chang. 2022, 174, 121276. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, S.; Abbas, J.; Sial, M.S.; Álvarez-Otero, S.; Cioca, L.-I. Achieving Green Innovation and Sustainable Development Goals through Green Knowledge Management: Moderating Role of Organizational Green Culture. J. Innov. Knowl. 2022, 7, 100272. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, S.; Wang, J.J.; Li, J.; Wang, J.J.; Liang, L. Policy Implications for Promoting the Adoption of Electric Vehicles: Do Consumer’s Knowledge, Perceived Risk and Financial Incentive Policy Matter? Transp. Res. Part A Policy Pract. 2018, 117, 58–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Choi, D.; Johnson, K.K.P. Influences of Environmental and Hedonic Motivations on Intention to Purchase Green Products: An Extension of the Theory of Planned Behavior. Sustain. Prod. Consum. 2019, 18, 145–155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, S.; Abbas, J.; Álvarez-Otero, S.; Cherian, J. Green Knowledge Management: Scale Development and Validation. J. Innov. Knowl. 2022, 7, 100244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Obuobi, B.; Zhang, Y.; Adu-Gyamfi, G.; Nketiah, E.; Grant, M.K.; Adjei, M.; Cudjoe, D. Fruits and Vegetable Waste Management Behavior among Retailers in Kumasi, Ghana. J. Retail. Consum. Serv. 2022, 67, 102971. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adu-Gyamfi, G.; Song, H.; Nketiah, E.; Obuobi, B.; Adjei, M.; Cudjoe, D. Determinants of Adoption Intention of Battery Swap Technology for Electric Vehicles. Energy 2022, 251, 123862. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fielding, K.S.; Head, B.W. Determinants of Young Australians’ Environmental Actions: The Role of Responsibility Attributions, Locus of Control, Knowledge and Attitudes. Environ. Educ. Res. 2012, 18, 171–186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bamberg, S. How Does Environmental Concern Influence Specific Environmentally Related Behaviors? A New Answer to an Old Question. J. Environ. Psychol. 2003, 23, 21–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alzubaidi, H.; Slade, E.L.; Dwivedi, Y.K. Examining Antecedents of Consumers’ pro-Environmental Behaviours: TPB Extended with Materialism and Innovativeness. J. Bus. Res. 2021, 122, 685–699. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fraccascia, L.; Ceccarelli, G.; Dangelico, R.M. Green Products from Industrial Symbiosis: Are Consumers Ready for Them? Technol. Forecast. Soc. Chang. 2023, 189, 122395. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gansser, O.A.; Reich, C.S. Influence of the New Ecological Paradigm (NEP) and Environmental Concerns on pro-Environmental Behavioral Intention Based on the Theory of Planned Behavior (TPB). J. Clean. Prod. 2023, 382, 134629. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nguyen-Phuoc, D.Q.; Nguyen, N.A.N.; Tran, P.T.K.; Pham, H.-G.; Oviedo-Trespalacios, O. The Influence of Environmental Concerns and Psychosocial Factors on Electric Motorbike Switching Intention in the Global South. J. Transp. Geogr. 2023, 113, 103705. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parashar, S.; Singh, S.; Sood, G. Examining the Role of Health Consciousness, Environmental Awareness and Intention on Purchase of Organic Food: A Moderated Model of Attitude. J. Clean. Prod. 2023, 386, 135553. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pandey, S.; Budhathoki, M.; Perez-Cueto, F.J.A.; Thomsen, M. Factors Influencing Consumers’ Food Waste Reduction Behaviour at University Canteens. Food Qual. Prefer. 2023, 111, 104991. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raymond, C.M.; Brown, G.; Weber, D. The Measurement of Place Attachment: Personal, Community, and Environmental Connections. J. Environ. Psychol. 2010, 30, 422–434. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clayton, S.; Devine-Wright, P.; Swim, J.; Bonnes, M.; Steg, L.; Whitmarsh, L.; Carrico, A. Expanding the Role for Psychology in Addressing Environmental Challenges. Am. Psychol. 2016, 71, 199–215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Triantafyllidis, S.; Kaplanidou, K. Marathon Runners: A Fertile Market for “Green” Donations? J. Glob. Sport Manag. 2021, 6, 359–372. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scannell, L.; Gifford, R. Defining Place Attachment: A Tripartite Organizing Framework. J. Environ. Psychol. 2010, 30, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carfora, V.; Caso, D.; Sparks, P.; Conner, M. Moderating Effects of Pro-Environmental Self-Identity on pro-Environmental Intentions and Behavior: A Multi-Behavior Study. J. Environ. Psychol. 2017, 53, 92–99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramkissoon, H.; Weiler, B.; Smith, L.D.G. Place Attachment and Pro-Environmental Behaviour in National Parks: The Development of a Conceptual Framework. J. Sustain. Tour. 2012, 20, 257–276. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Triantafyllidis, S.; Darvin, L. Mass-Participant Sport Events and Sustainable Development: Gender, Social Bonding, and Connectedness to Nature as Predictors of Socially and Environmentally Responsible Behavior Intentions. Sustain. Sci. 2021, 16, 239–253. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wan, C.; Shen, G.Q.; Choi, S. The Place-Based Approach to Recycling Intention: Integrating Place Attachment into the Extended Theory of Planned Behavior. Resour. Conserv. Recycl. 2021, 169, 105549. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Walker, G.J.; Chapman, R. Thinking like a Park: The Effects of Sense of Place, Perspective-Taking, and Empathy on Pro-Environmental Intentions. J. Park Recreat. Adm. 2003, 21, 71–86. [Google Scholar]

- Gao, S.; Bao, J.; Li, R.; Liu, X.; Wu, C. Drivers and Reduction Solutions of Food Waste in the Chinese Food Service Business. Sustain. Prod. Consum. 2021, 26, 78–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Del Ponte, A.; Li, L.; Ang, L.; Lim, N.; Seow, W.J. Evaluating SoJump.Com as a Tool for Online Behavioral Research in China. J. Behav. Exp. Financ. 2024, 41, 100905. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, X.; Wang, S.; Yu, Y. Consumer’s Intention to Purchase Green Furniture: Do Health Consciousness and Environmental Awareness Matter? Sci. Total Environ. 2020, 704, 135275. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hong, Y.; Hu, J.; Chen, M.; Tang, S. Motives and Antecedents Affecting Green Purchase Intention: Implications for Green Economic Recovery. Econ. Anal. Policy 2023, 77, 523–538. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prakash, G.; Choudhary, S.; Kumar, A.; Garza-Reyes, J.A.; Khan, S.A.R.; Panda, T.K. Do Altruistic and Egoistic Values Influence Consumers’ Attitudes and Purchase Intentions towards Eco-Friendly Packaged Products? An Empirical Investigation. J. Retail. Consum. Serv. 2019, 50, 163–169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yadav, R.; Pathak, G.S. Young Consumers’ Intention towards Buying Green Products in a Developing Nation: Extending the Theory of Planned Behavior. J. Clean. Prod. 2016, 135, 732–739. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dijkstra, T.K.; Henseler, J. Consistent Partial Least Squares Path Modeling. MIS Q. 2015, 39, 297–316. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hair, J.F.; Hult, G.T.M.; Ringle, C.M.; Sarstedt, M. A Primer on Partial Least Squares Structural Equation Modeling (PLS-SEM); Sage Publications: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Hair, J.F.; Ringle, C.M.; Sarstedt, M. PLS-SEM: Indeed a Silver Bullet. J. Mark. Theory Pract. 2011, 19, 139–152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Gahtani, S.S.; Hubona, G.S.; Wang, J. Information Technology (IT) in Saudi Arabia: Culture and the Acceptance and Use of IT. Inf. Manag. 2007, 44, 681–691. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fornell, C.; Larcker, D.F. Evaluating Structural Equation Models with Unobservable Variables and Measurement Error. J. Mark. Res. 1981, 18, 39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Henseler, J.; Ringle, C.M.; Sarstedt, M. A New Criterion for Assessing Discriminant Validity in Variance-Based Structural Equation Modeling. J. Acad. Mark. Sci. 2015, 43, 115–135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amit Kumar, G. Framing a Model for Green Buying Behavior of Indian Consumers: From the Lenses of the Theory of Planned Behavior. J. Clean. Prod. 2021, 295, 126487. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nimri, R.; Patiar, A.; Jin, X. The Determinants of Consumers’ Intention of Purchasing Green Hotel Accommodation: Extending the Theory of Planned Behaviour. J. Hosp. Tour. Manag. 2020, 45, 535–543. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cesarina Mason, M.; Pauluzzo, R.; Muhammad Umar, R. Recycling Habits and Environmental Responses to Fast-Fashion Consumption: Enhancing the Theory of Planned Behavior to Predict Generation Y Consumers’ Purchase Decisions. Waste Manag. 2022, 139, 146–157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Adu-Gyamfi, G.; Asamoah, A.N.; Nketiah, E.; Obuobi, B.; Adjei, M.; Cudjoe, D.; Zhu, B. Reducing Waste Management Challenges: Empirical Assessment of Waste Sorting Intention among Corporate Employees in Ghana. J. Retail. Consum. Serv. 2023, 72, 103261. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, A.; Peng, N. Green Hotel Knowledge and Tourists’ Staying Behavior. Ann. Tour. Res. 2012, 39, 2211–2216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- White Baker, E.; Al-Gahtani, S.S.; Hubona, G.S. The Effects of Gender and Age on New Technology Implementation in a Developing Country. Inf. Technol. People 2007, 20, 352–375. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ha, J.W.; Jeon, E.-C.; Park, S.K. Status of Environmental Awareness and Participation in Seoul, Korea and Factors That Motivate a Green Lifestyle to Mitigate Climate Change. Curr. Res. Environ. Sustain. 2023, 5, 100211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Profile | Freq. | % | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Gender | Male | 165 | 42.3 |

| Female | 225 | 57.7 | |

| Age | 18–28 | 77 | 19.7 |

| 29–38 | 139 | 35.6 | |

| 39–48 | 117 | 30 | |

| 49–59 | 56 | 14.4 | |

| 59 and above | 1 | 0.3 | |

| Marital status | Single | 84 | 21.5 |

| Married | 273 | 70 | |

| Divorced | 33 | 8.5 | |

| Education | High School and Below | 50 | 12.8 |

| Junior College | 91 | 23.3 | |

| Vocational | 219 | 56.2 | |

| Bachelor | 30 | 7.7 | |

| Income | Postgraduate | 73 | 18.7 |

| Below 2500 RMB | 33 | 8.5 | |

| 2500–5000 RMB | 122 | 31.3 | |

| 5001–7500 RMB | 115 | 29.5 | |

| 7501–10,000 RMB | 47 | 12.1 | |

| Family size | 2 or less | 6 | 1.5 |

| 3 | 96 | 24.6 | |

| 4 | 191 | 49 | |

| 5 or more | 97 | 24.9 | |

| Total | 390 | 100 | |

| Variable | Items | Factor Loadings (FL) | Cronbach’s Alpha (CA) | Composite Reliability | rho_A | Average Variance Extracted (AVE) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Attitude | ATT1 | 0.806 | 0.907 | 0.907 | 0.931 | 0.729 |

| ATT2 | 0.864 | |||||

| ATT3 | 0.868 | |||||

| ATT4 | 0.871 | |||||

| ATT5 | 0.857 | |||||

| Environmental concern | EC1 | 0.795 | 0.862 | 0.866 | 0.906 | 0.707 |

| EC2 | 0.868 | |||||

| EC3 | 0.842 | |||||

| EC4 | 0.857 | |||||

| Green Information and Knowledge | GIK1 | 0.753 | 0.858 | 0.869 | 0.898 | 0.638 |

| GIK2 | 0.863 | |||||

| GIK3 | 0.781 | |||||

| GIK4 | 0.820 | |||||

| GIK5 | 0.772 | |||||

| Natural bonding | NB1 | 0.853 | 0.850 | 0.852 | 0.899 | 0.689 |

| NB2 | 0.814 | |||||

| NB3 | 0.842 | |||||

| NB4 | 0.811 | |||||

| Food-saving behavior | FSB1 | 0.883 | 0.883 | 0.889 | 0.919 | 0.740 |

| FSB2 | 0.815 | |||||

| FSB3 | 0.872 | |||||

| FSB 4 | 0.871 | |||||

| Perceived behavioral norms | PBC1 | 0.817 | 0.811 | 0.818 | 0.888 | 0.725 |

| PBC2 | 0.881 | |||||

| PBC3 | 0.856 | |||||

| Food-saving intention | FSI1 | 0.810 | 0.847 | 0.850 | 0.897 | 0.685 |

| FSI2 | 0.847 | |||||

| FSI3 | 0.811 | |||||

| FSI4 | 0.842 | |||||

| Subjective norms | SN1 | 0.768 | 0.708 | 0.719 | 0.836 | 0.629 |

| SN3 | 0.787 | |||||

| SN3 | 0.823 |

| Heterotrait–Monotrait Ratio (HTMT)—Matrix | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Items | ATT | EC | GIK | NB | FSB | PBC | FSI | SN |

| ATT | ||||||||

| EC | 0.477 | |||||||

| GIK | 0.373 | 0.586 | ||||||

| NB | 0.364 | 0.537 | 0.292 | |||||

| FSB | 0.347 | 0.509 | 0.371 | 0.605 | ||||

| PBC | 0.261 | 0.359 | 0.483 | 0.277 | 0.296 | |||

| FSI | 0.483 | 0.339 | 0.585 | 0.532 | 0.493 | 0.329 | ||

| SN | 0.307 | 0.343 | 0.304 | 0.420 | 0.301 | 0.226 | 0.321 | |

| Fornell–Larcker criterion | ||||||||

| Items | ATT | EC | GIK | NB | FSB | PBC | FSI | SN |

| ATT | 0.854 | |||||||

| EC | 0.423 | 0.841 | ||||||

| GIK | 0.334 | 0.511 | 0.799 | |||||

| NB | 0.321 | 0.460 | 0.252 | 0.830 | ||||

| FSB | 0.310 | 0.447 | 0.327 | 0.527 | 0.860 | |||

| PBC | 0.225 | 0.302 | 0.406 | 0.232 | 0.252 | 0.852 | ||

| FSI | 0.424 | 0.970 | 0.507 | 0.453 | 0.431 | 0.277 | 0.828 | |

| SN | 0.251 | 0.270 | 0.242 | 0.327 | 0.239 | 0.176 | 0.252 | 0.793 |

| Measurement Items | Threshold | Outcomes |

|---|---|---|

| SRMR | <0.08 | 0.052 |

| NFI | >0.80 | 0.877 |

| R2 (GL) | 0.338 | |

| R2 (GLI) | 0.231 |

| Hypothesis | Pathway | Coefficients | Standard Deviation | T Statistics | p Values | Confidence Intervals | Outcome | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2.5% | 97.5% | |||||||

| H1 | ATT -> FSI | 0.353 | 0.043 | 8.078 | 0.000 *** | 0.265 | 0.438 | Validated |

| H2a | SN -> ATT | 0.106 | 0.049 | 2.096 | 0.036 * | 0.008 | 0.205 | Validated |

| H2b | SN -> FSI | 0.135 | 0.047 | 2.823 | 0.005 ** | 0.039 | 0.228 | Validated |

| H3 | PBC -> FSI | 0.177 | 0.046 | 3.778 | 0.000 *** | 0.084 | 0.264 | Validated |

| H4a | GIK -> ATT | 0.142 | 0.054 | 2.637 | 0.008 ** | 0.033 | 0.245 | Validated |

| H4b | GIK -> EC | 0.514 | 0.037 | 13.967 | 0.000 ** | 0.440 | 0.582 | Validated |

| H4c | GIK -> FSB | 0.132 | 0.048 | 2.780 | 0.005 ** | 0.037 | 0.223 | Validated |

| H5a | EC -> ATT | 0.264 | 0.057 | 4.628 | 0.000 *** | 0.153 | 0.375 | Validated |

| H5b | EC -> PBC | 0.306 | 0.045 | 6.703 | 0.000 *** | 0.216 | 0.393 | Validated |

| H6a | NB -> ATT | 0.131 | 0.056 | 2.337 | 0.019 * | 0.021 | 0.243 | Validated |

| H6b | NB -> FSB | 0.416 | 0.040 | 10.314 | 0.000 *** | 0.337 | 0.494 | Validated |

| H7 | FSI -> FSB | 0.178 | 0.053 | 3.346 | 0.001 *** | 0.073 | 0.281 | Validated |

| Pathway | Original Sample (β) | T Statistics | p Values | Confidence Intervals | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2.5% | 97.5% | |||||

| EC -> ATT -> FSI | 0.092 | 3.110 | 0.002 ** | 0.042 | 0.160 | +√ |

| GIK -> EC -> ATT | 0.134 | 4.277 | 0.000 *** | 0.077 | 0.200 | +√ |

| GIK -> ATT -> FSI -> FSB | 0.009 | 1.976 | 0.048 * | 0.002 | 0.019 | +√ |

| NB -> ATT -> FSI | 0.046 | 2.330 | 0.020 * | 0.007 | 0.086 | +√ |

| EC -> PBC -> FSI | 0.053 | 2.458 | 0.014 * | 0.018 | 0.101 | +√ |

| GIK -> EC -> PBC -> FSI | 0.027 | 2.276 | 0.023 * | 0.009 | 0.055 | +√ |

| GIK -> EC -> PBC | 0.154 | 5.336 | 0.000 *** | 0.103 | 0.216 | +√ |

| GIK -> ATT -> FSI | 0.050 | 2.528 | 0.012 * | 0.011 | 0.090 | +√ |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Gao, F.; Nketiah, E.; Shi, V. Understanding and Enhancing Food Conservation Behaviors and Operations. Sustainability 2024, 16, 2898. https://doi.org/10.3390/su16072898

Gao F, Nketiah E, Shi V. Understanding and Enhancing Food Conservation Behaviors and Operations. Sustainability. 2024; 16(7):2898. https://doi.org/10.3390/su16072898

Chicago/Turabian StyleGao, Fengni, Emmanuel Nketiah, and Victor Shi. 2024. "Understanding and Enhancing Food Conservation Behaviors and Operations" Sustainability 16, no. 7: 2898. https://doi.org/10.3390/su16072898

APA StyleGao, F., Nketiah, E., & Shi, V. (2024). Understanding and Enhancing Food Conservation Behaviors and Operations. Sustainability, 16(7), 2898. https://doi.org/10.3390/su16072898