Abstract

Social innovation as an outcome of social entrepreneurship represents the primary drive of social enterprises (SEs). In the emergent context of a digitally transforming entrepreneurship scenario, this study intends to investigate the role of digital capabilities (DC) in social innovation performance (SIP) in SEs while considering the underlying effects of a firm-level entrepreneurial orientation (EO). Utilizing a quantitative survey approach, the study acquired a total of 344 valid responses from SEs in Saudi Arabia. The data analysis performed through partial least square structural equation modeling (SmartPLS 3.0) revealed that DC have no direct impact on SIP in SEs. However, DC influence SIP through the full mediation effects of EO dimensions of social proactiveness, and social innovativeness. The mediation effects of social risk-taking on the DC-SIP relationship were not established. This work is the first to conceptualize and test a theoretical framework linking the DC and EO constructs concerning SIP in SEs. As a result, the study produces several academic and managerial implications underpinning social innovation amid the digitally transforming entrepreneurship context in SEs.

1. Introduction

Social innovations as drivers of social change in “Society 5.0” and “Industry 5.0” [1] address social, economic, political, and environmental issues pertaining to achievement of the “Sustainable Development Goals” (SDGs) [2,3]. Social innovation typically refers to a “new strategy for addressing a social issue that is more sustainable, efficient, or effective than current approaches and that primarily benefits society as a whole rather than just a small group of individuals” [4]. As such, social enterprises (SEs) are accredited as the primary social entities that develop and implement social innovations [2,5]. From an organizational perspective, a social enterprise can stand out in the market and accomplish long-term sustainability if it excels in social innovation compared to its rivals [6]. Social innovation equips SEs to position themselves in an increasingly competitive market, whether through internal organizational innovation or through tactics for navigating the external environment [7]. Even the accomplishment of a social enterprise’s financial goals is associated with, or seen as, the development of social value [8]. Despite the fact that social entrepreneurship (S-ENT) research and practice has grown significantly over the past two decades [9], the literature reveals a significant disparity in social innovation strategies and outcomes in SEs [10]. This discrepancy is marked by a lack of understanding of the organizational elements that can support the development, scaling, and implementation of social innovations in SEs. The scenario is further complicated by the diverse initiatives of private enterprises to mimic the social innovation approaches deployed by SEs [11]. Thus, it is not surprising that there has been a recent upsurge in studies exploring the variables affecting a firm’s capacity for innovation. For instance, the emerging entrepreneurship and innovation literature has emphasized the necessity of orchestrating the internal resources and procedures for a firm’s innovation performance [7,12]. In this direction, the authors are exploring the contexts and antecedents for and consequences of leveraging and realizing digital value propositions for firms’ innovation performance [13]. Since digital transformation (DT) is spreading as a larger socio-technical transformation [14] and permeates all organizational functions [15,16], it has strategic ramifications for firms promoting social innovation [17,18].

From an internal organizational standpoint, digital transformation signifies a substantial shift in the environment and mandates the development of new technological innovation capabilities at various operational and business levels of firms [19]. In this regard, digital capabilities (DC) are widely manifested as the organization’s ability to broadly include digital assets and business resources and leverage digital networks to create products, services, and processes to gain organizational learning and customer value [20]. DC as strategic dynamic capabilities [21], are gaining wide popularity in the current changing and turbulent business times [22]. The emerging literature is increasingly examining the links of digital transformation and DC with many organizational innovation capabilities like service innovation [23], value co-creation [24], and firm performance and competitiveness, etc. [7,25]. Accordingly, digitization has presented a new impetus and challenges for social value creation in the current digitally transforming entrepreneurship scenario [18,26], and many SEs stand to lose out if they do not leverage digital technologies [17]. Therefore, DC appear to be quite important to a social enterprise’s social innovation outcomes. However, the growth of the literature in this direction is largely contained within specific disciplines like strategic management [27], operations management and manufacturing [28], marketing [24], etc. While SEs largely are reported to be facing multidimensional challenges related to SIP, sustainability, and DT [17,18,29], the academic literature in this direction is inconsistent and fragmented [26,30]. Despite its crucial significance, the S-ENT literature has not yet addressed how DC might relate to performance and other S-ENT outcomes in SEs. This is problematic because a structured understanding of the factors influencing SIP amid the digital entrepreneurship landscape can offer strategic implications for both S-ENT theory and practice [18,26]. As a result, the current study specifically intends to address the question of how DC impact the social innovation performance (SIP) of SEs.

Despite the foregoing, the success or failure of DT is often dictated by larger organizational and technological approaches, as DT is ubiquitous and crosses organizational boundaries [31]. For instance, scholars have recently paid increasing attention to the phenomenon of entrepreneurial orientation (EO) and its nexus with a firm’s capacity to achieve its strategic goals both in commercial and SEs [32,33]. This may implore lessons for SEs to leverage their DC, since DT is acknowledged as an entrepreneurial process [34], and any innovation-led strategies necessitate supportive organizational behavior [35]. A few recent studies have highlighted the relationships between market orientation, entrepreneurial intentions, and performance in S-ENT [10,36]. This implies that an EO for a social enterprise has a crucial contingency role, one that may help or hamper its capacity to create and utilize DC for its SIP. Thus, it can be argued that SEs can strengthen their capacity to exploit digital technologies effectively by reconfiguring their available resources and strategies like the EO. This concept is in line with the theory of dynamic capability [37]. Yet, the current literature lacks an understanding of how SEs may benefit from growing and using their organizational capabilities, particularly their digital ones. The present study, thus, examines how the EO of SEs influences their ability to exploit their DC for SIP.

This study makes use of the resource-based theory (RBV) [38] and its extension, the dynamic capabilities theory [21], to fill in the aforementioned gaps. Since the study is the first to propose and test the framework involving SIP, DC, and an EO in SEs, it generates crucial theoretical and practical implications underpinning SIP and digital transformation in SEs.

The remaining work is organized in the following way: the first section presents a critical literature summary of social innovation within SEs. The second section creates the theoretical background for the hypothesized relationships among the underlying constructs. The methodology is detailed in the third section. The study’s analysis and conclusions come right after this. The discussion and study’s conclusions are expanded upon in the final sections.

2. Theoretical Background

Social Innovation and Social Enterprises

In today’s political and economic discourse, social innovation is overwhelmingly endorsed as a means of tackling the major issues highlighted by the United Nations 17 Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs), which cannot be solved unilaterally [2,3]. A growing body of studies agrees that governments tend to be more active in promoting enterprises to create social value and addressing social needs [39]. Accordingly, there is a notable increase in scholarly interest in researching social innovation, even though the idea is still poorly understood and is commonly employed as a “metaphor for social and technological change” [40]. Broadly speaking, social innovation is the term used to describe how commercial concepts, management techniques, and market principles are incorporated into government and nonprofit organizations [4]. Consequently, organizations that prioritize social purposes are the main conduits for the dissemination of social innovations [5]. As a result, SEs are acknowledged as the main organizations creating and applying social innovations globally [2]. However, in current competitive markets, SEs need to adopt an entrepreneurial “attitude” and incorporate business concepts into the provision of social goods and/or services [41,42]. Accordingly, many nonprofit entities have been found to be undergoing an incremental transformation in terms of combining multiple organizational forms [43] and merging among themselves to broaden their social service provision, as market orientation differentiates SEs from pure nonprofits [8]. In addition to helping social organizations optimize long-term market benefits, market orientation enables them to grasp customer expectations, competitive actions, and value chain dynamics [36]. In fact, several studies have highlighted the relationships between market orientation, entrepreneurial intentions, and performance in S-ENT. Since SEs pursue double- or triple-bottom-line objectives, the authors have achieved consensus about the intricacy of their business models, and the distinct challenges it poses for the strategic management of SEs [8]. As such, SEs face a variety of challenges in their efforts to drive SIP [44], and many SEs are not capable of becoming sustainable in their efforts to address social needs [45]. The existing literature on the drivers of SIP in SEs reveals a diversity of anecdotal factors including legal and public support for social innovators [46], the role of individual entrepreneurs, local “embeddedness”, social networks [47], and governance models, etc. In the meanwhile, despite substantial efforts being made to define social innovation, the factors and mechanisms that give rise to it are receiving comparatively little attention [48]. From an organizational perspective, all forms of innovation, including social ones, develop within socioeconomic contexts. Therefore, social innovation is driven by human, organizational, and contextual factors [40]. Nevertheless, despite the proliferating nature of studies on S-ENT, little is known about the organizational elements of SEs that can support the development, scaling, and implementation of social innovations.

3. Social Innovation within Social Enterprises: A Critical Summary of the Topical Literature

A critical examination of the extant studies on social innovation within S-ENT enabled us to categorize the extant studies into three broad themes. The first stream of studies was focused on understanding the nature and process of social innovation within SEs [49]. For instance, the authors tried to compare how social entrepreneurs and commercial entrepreneurs recognize social innovation opportunities [2], as well as outline the process, from the identification of social innovation opportunities through the scaling-up of social innovation by SEs [10,50]. Subsequently, some scholars went on to analyze how a social enterprise may use social innovation as a sort of competitive strategy to set itself apart from its rivals [6,51]. In an effort to support the latter research angle, our study looks at the elements in the developing digital transformation context that allow SEs to enhance their SIP and gain a competitive edge. The second stream of studies focused on examining social innovation underpinning the creation of SEs [52]. For instance, Peredo and Chrisman [53] discuss the unique methods by which community-based social entrepreneurs mobilize resources to address social issues and transform local communities [54]. Similarly, Lurtz and Kreutzer [55] expand on the concept of EO in the context of SEs, where inventiveness aids in the formation of new ventures. In recent years, EO research attracted further scholarly interest in the S-ENT context [32,56] with the proliferation of studies examining the EO and its links with S-ENT intentions, strategic orientation, and social value creation of SEs [33,57]. Our research aims to provide new insights into this area by elucidating the mechanisms through which an EO affects SIP in SEs. The third line of inquiry endeavors to tackle the strategic administration of SEs, considering the difficulties in overseeing the bottom-line goals [8,58]. Accordingly, those studies attempt to examine the varied determinants of the social and commercial performance of SEs [59]. Specifically, this evolving form of studies considers the pursuit of a market orientation and market disruptiveness capability, etc. as improving the performance of SEs [10]. In this connection, many scholars have adopted the RBV to explore the development of organizational capabilities like strategic orientation, market demand, etc. in SEs [8,36,51]. In a similar vein, our research aims to enrich the literature by examining the impact of DC on the SIP of SEs. We use RBV to envision DC as a crucial asset for SEs since they stand to lose out if they do not adopt digital technology [39].

4. Hypotheses Development

Resource-Based View of Social Enterprises

According to resource-based theory, an organization’s resources, which have an impact on the choice and execution of its business strategy, are its sources of competitive advantage [60]. This theoretical approach has been frequently utilized to describe how different forms of resources assist SEs to outperform their rivals in various commercial and social domains [61]. As per the capability-based viewpoint, many capabilities that organizations possess are significant factors in the variations in their organizational behavior and performance [62]. Meanwhile, one extension of resource-based theory argues that higher performance is not always a result of having more resources. Instead, it is essential to build specific organizational capabilities that in turn promote performance [63]. Likewise, emerging studies performed in many contexts support the relationship between technological capability and innovation [64], while also confirming the association between innovation and organizational performance [65]. Nevertheless, in the context of digital technology, there is little empirical evidence of the association between digital innovation and organizational performance [66]. However, the firms that attempt to tap their full DC gain higher returns compared to average firms [67]. As a result, the emerging literature has increasingly been examining the links of digital transformation and DC with many organizational capabilities like service innovation [23], value co-creation [68], and firm performance and competitiveness, etc. [7,25]. Similarly, the authors propose indicators of the impact of DC across crucial business domains like technological capabilities, labor and social relations, marketing capabilities, etc. [69]. For instance, organizational capabilities like effective human resource management practices, a strategic orientation, and the ability to utilize IT resources, etc. enable SEs to achieve superior performance in diverse areas such as collaborations and partnerships and financial sustainability, etc. [26]. Grounded by the above resource–capability–performance connection, the present study establishes hypotheses to explain the relationships between DC, an EO, and SIP in SEs.

5. Implications of Digital Capabilities for Social Innovation Performance

Most recent studies on DC have been on the connections between DC and corporate DT as well as how DC affects digital innovation [70]. The favorable effects of digital transformation on the innovation model and entrepreneurial behavior have been the subject of recent research [71,72]. Although digital technologies can have a significant impact on the entrepreneurial process, their effects are still not fully understood [73]. Nevertheless, many authors contend that an organization’s ability to grasp digital technologies is crucial to its success [70,72]. Because organizational capabilities speed up the innovation process by integrating and mobilizing both human and technological strengths and resources, they are essential prerequisites for managing DT challenges [74]. Accordingly, the authors consider DC to be a kind of dynamic capability that supports the organization’s digital orientation [21,37]. Yet, many organizations, especially small businesses, have yet to take advantage of these opportunities. They must properly standardize the processes to efficiently use, coordinate, and exploit digital resources (or create new ones) as a source of sustained competitiveness [29]. Thus, the ability to create an effective internal organization is regarded as a prerequisite for the success of innovation initiatives [52].

DC reflects organizations’ capability to recognize, choose, and update promising digital technologies. This process transforms abstract digital technologies into tailored digital solutions [75], creating the internal framework necessary to address triple-bottom-line issues [76]. Accordingly, authors have found evidence for DC promoting the attainment of social and environmental goals in organizations [72,77]. For example, different digital applications can help to improve the social value of SMEs [78]. Likewise, authors found promising evidence for the nexus of digital transformation and S-ENT as contributing to national well-being [79]. Along with social innovations, digital solutions will be able to encourage competitiveness, regional development, and job creation—actions that address several social challenges [80]. The “European Green Deal” has recognized the significant role of digitalization in progressing toward a sustainable future aligned with the UN’s 2030 SDGs [39]. Likewise, the EU’s response to the outbreak of the pandemic also provided new actions in the same direction [18,39]. This viewpoint outlines the future possibilities of digital transformation for society and industry. In recent years, digital technologies have played a more visible role in addressing socioeconomic challenges, which has converted them into powerful tools with which to magnify the outcomes of social innovation [81]. The existing studies specifically have found evidence for benefits of the use of ICT in the implementation of social innovation [82]. Businesses with digital capability can quickly upgrade or iterate their digital infrastructures, respond to socio-ecological challenges posed by sustainable development requirements, and quickly adapt to shifting external social and environmental needs [76]. It is, therefore, acceptable to conclude that the more a firm is prepared with these resources and the more effectively it can practice using them, the more likely it is to develop a beneficial strategy toward social innovation [83]. This logic is consistent with the dynamic capability theory, which shows how businesses adapt and renew their capacities and resources over time in unstable circumstances [37]. The digital dynamic capability then acts as a spontaneous, thorough impetus for enterprise innovation and transformation [84]. Digital dynamic capability builds on the resources and skills of organizations to apply various digital technologies crosswise, enhance the sustainable value creation capabilities of their current services and products, and dynamically adjust their sustainable business models, ultimately promoting the achievement of social and environmental value goals [77]. This is demonstrated by many SEs that utilized some creative techniques to digitize for social innovation during the COVID-19 pandemic [39,76]. Further from RBV, organizational capabilities are said to have an impact on the effectiveness of green innovation adoption [85]. Recent studies advocate for firms to determine the worth of their resources and how best to employ them, considering the competitive landscape [86]. For example, a firm’s ability to absorb information—that is, its capability to gather, communicate, and use information from both internal and external sources—influences green innovation [87]. The capabilities to capitalize on various operations like artificial intelligence, green production, product traceability, and recycling and remanufacturing can be utilized to attain superior performance [88]. Therefore, incorporating technology into a competitive strategy while also implementing environmentally friendly practices aids in achieving sustainability goals [89]. The emerging findings suggest that Industry 4.0, concerning digitalization, benefits environmental sustainability in Saudi Arabian textile enterprises [90]. Considering the theoretical lens of dynamic capabilities theory [21], this study considered how DCs make it possible to recognize signals from the environment and activate resources and capabilities that lead to increased social innovation in SEs. Grounded by the above resource–capability–performance connection, the present study establishes the following hypothesis to explain the relationship between DCs and SIP in SEs.

Hypothesis 1.

Digital capabilities positively influence social innovation performance in social enterprises.

6. Entrepreneurial Orientation, Digital Capabilities, and Social Innovation Performance

EO, according to Covin and Slevin [91], is the culmination of an organization’s structures, procedures, and behaviors, which are mostly expressed as innovation, proactivity, and risk-taking. As a potent predictor of company entrepreneurial activity, the EO has been the subject of much research in entrepreneurship [92]. A significant and expanding body of research demonstrates the relationship between firms’ EO and enhanced business performance [93]; however, other organizational components such as technological capabilities, human capital, marketing, etc., mediate this relationship [94].

The EO has attracted scholarly interest in the S-ENT context as well [32,55,93], with the proliferation of studies examining the EO and its links with a S-ENT-based intention, strategic orientation, and social value creation and performance in SEs [33,36,57]. Yet, to successfully deploy new goods or processes on a “meaningful scale at practical costs”, social innovation necessitates the active functioning of organizational tasks [95]. As a result, an increasing amount of research emphasizes how important it is to use the EO as a strategic asset to gain an advantage over competitors in S-ENT [59]. The EO has been seen to promote or increase innovation in commercial companies [59,96], and a recent study has established this role for EO in the S-ENT context as well [97]. Since an EO enhances an organization’s ability to recognize the resources required for innovation [7,98], it positions the business to take advantage of opportunities and think of novel resource combinations when the business innovates [99]. Accordingly, even if an EO supports the company’s entrepreneurial strategy [100,101], it also affects the company’s capacity to try out novel technologies, seize opportunities, and take on risky projects [96].

On the other hand, a stronger EO inclination puts the company in a position to develop new capabilities and upgrade current ones to ones that are more growth-oriented [102]. Drawing from the same theoretical foundations, recent studies have begun to uncover the connections between effective DT in enterprises and the EO [103]. Accordingly, it is thought that the entrepreneurial approach to DT is essential for helping small businesses realize their goals related to digital transformation [73,104]. In the meanwhile, companies need to keep up their proactive efforts to optimize the efficiency, innovation, and convergence benefits of digital technology [104]. The ultimate goal of digital technology and digital dynamic capabilities is to support an organization’s strategic outcomes. They are both designed for innovation and development. However, only when resources and skills are exposed to market processes through activities, routines, and business processes can their actual worth and ability to produce competitive advantages be recognized [105]. This aligns with the findings of a recent study conducted by Martínez-Caro et al. [106], which suggested that DC might not always result in successful innovation. The latest studies clarify how managerial and technological competencies, among other organizational tasks and capacities, impact a company’s capacity for innovation and effective management of its digital assets [22]. Likewise, from a firm’s perspective, internal reconfiguration methods could enhance innovation and firm performance [107]. This indicates that the strategic alignment of DC and digital transformation with creative activities like an EO may have an impact on a company’s inventive performance [108]. For SEs, who must deal with a shifting global environment and diminishing resources, such an approach has major ramifications [109]. According to Akgün et al. [110], innovativeness as a component of an EO determines the organizational commitment that supports the development of innovative ideas, goods, and services as well as technological advancements in SEs. Both large and small organizations can employ innovative ideas to boost business performance, as the innovativeness dimension is a crucial part of corporate strategy [96,111]. Being creative means that the company must seek out and support the conceptualization of completely new products, processes, and capabilities in addition to taking a fresh approach to already existing products, processes, and capabilities [96]. According to Runyan et al. [111], these kinds of commercial endeavors significantly promote and hasten the creation of novel and inventive company practices and capacities, such as DC. As a result, being innovative will help the company launch new projects or competitive capabilities, including DC and digital transformation [74], and solve challenges through workplace innovation [112]. According to Spiess-Knafl et al. [113], their studies concluded that EO innovativeness in SEs aids in their growth and sustainability goals. One may argue that an EO’s innovativeness will enable SEs to achieve their goal of providing societal value by fundamentally redefining and renewing their DC, as it is a fitting response to a dynamic environment [103]. According to Wales et al. [114], proactiveness also involves predicting possible issues and adjusting to change. According to Lumpkin and Dess (1996), a company might obtain a competitive edge by projecting wants into the future or even actively modifying its own surroundings to influence the business climate. DC enhance the company’s capacity to use its resources, which in turn has a favorable impact on the organizational readiness for the new business models to be adopted and implemented [115]. This is consistent with the idea that a greater level of EO empowers businesses to actively seek out and obtain resources provided by the environment. The resources can, therefore, be applied to innovative and proactive projects that enable the company to explore and seize the many opportunities presented by a dynamic environment [109]. We, therefore, suggest that an EO aids businesses in coordinating dynamic capabilities to improve performance levels.

Third, the uncertainty that accompanies behaving entrepreneurially is often referred to as “risk-taking” [116]. Because of this, businesses that prioritize risk-taking act even in the face of uncertainty or lack of structure [117]. In addition, incumbent organizations are compelled to try new business models due to the unique internal and external uncertainties and complexity of the digital strategy conditions [16]. Moreover, it is hypothesized that taking risks as an entrepreneurial behavior promotes creativity in businesses [21], and risk-taking is an essential component of proactivity and innovation in SEs [118]. This behavior is suitable for firms’ DT missions since risk-taking, the corporate behavior that supports the EO, requires coping with uncertainty [119]. Replication, for instance, is a crucial component of SE growth and may be discussed in terms of proactiveness and risk-taking, wherein certain SEs take the initiative to perform measures that are then imitated by other SEs [120]. Nevertheless, taking advantage of chances to gain a competitive advantage carries some risk. Thus, it is equally plausible to argue that the risk-taking aspect of the EO has a positive mediating effect. Consequently, taking risks is a reasonable response to DT and raises the possibility of using DC to achieve better performance during these tumultuous times of entrepreneurship, which is being transformed by digital technology.

In conclusion, an EO has potential benefits in a dynamic environment. Highly entrepreneurially oriented firms will constantly enhance or even modify their dynamic skills and resources to align with their DT goals. Building on the above theoretical arguments, as well as previous empirical evidence, the current study makes the case that an EO, as a strategic direction of SEs, may be decisive in the development as well as the utilization of DC, which in turn would influence their SIP. As a result, this research aims to investigate the following hypotheses:

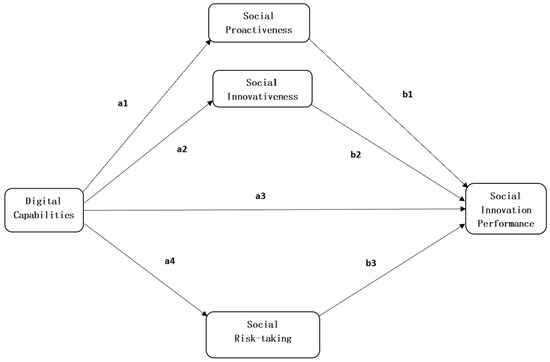

Hypothesis 2 (a1 × b1).

The social proactiveness dimension of entrepreneurial orientation mediates the relation between digital capabilities and social innovation performance in social enterprises.

Hypothesis 3 (a2 × b2).

The social innovativeness dimension of entrepreneurial orientation mediates the relation between digital capabilities and social innovation performance in social enterprises.

Hypothesis 4 (a4 × b3).

The social risk-taking dimension of entrepreneurial orientation mediates the relation between digital capabilities and social innovation performance in social enterprises.

Figure 1 depicts the hypothesized relationships.

Figure 1.

Proposed conceptual framework. H1 = a3: digital capabilities → social innovation performance. H2 = a1 × b1: digital capabilities → social proactiveness → social innovation performance. H3 = a2 × b2: digital capabilities → social innovativeness → social innovation performance. H4 = a4 × b3: digital capabilities → social risk-taking → social innovation performance.

7. Methodology

Context and Data Collection

The study’s sample units included a range of Saudi Arabian-based SEs. Since there is a lack of a publicly available source with a structured list of SEs, the researchers initially contacted several institutions individually since no single source offered a complete list of SEs. The organizations from which the list of SEs was obtained included, for instance, “the King Salman Youth Center”, “the Tamamy for Social Entrepreneurship”, and “the Ministry of Labor and Social Development”, as these institutions are active participants in S-ENT training, incubation, and acceleration plans and programs, etc. Such organizations and institutions provided a combined source for a data set for SEs. The process resulted in a total of 1082 SEs, which were included in the final pooled sample. The rationale behind examining the Saudi Arabian context stems from the fact that the country’s small businesses have demonstrated remarkable adaptability in the face of the difficult COVID-19 pandemic in 2020, with most social entrepreneurs and small business owners thinking that reaching Vision-2030 targets requires digital adaption [121]. Interestingly, Saudi Arabia is well positioned to develop this SE practice because of its leadership in charitable and philanthropic organizations and foundations, coupled with the presence of “Waqf” and “Zakat” as two important Islamic levers [122]. In light of this, the government recognizes that S-ENT is a crucial tool for achieving the Vision-2030 objectives by serving as a catalyst in areas like economic diversification, social services, healthcare, employment creation, and education, among others [123]. Furthermore, the Vision-2030 initiatives—like digital transformation and digital adaptation—are positioned as potent tools for the resurgence of Saudi Arabia’s social enterprise economy and nonprofit sector [121,124], which further qualifies Saudi Arabian SEs as appropriate subjects to comprehend the unique interaction between DC and SIP.

The study employed survey methodology to gather the primary data from owners/CEOs/managers of SEs (owing to their pivotal role in managing the SEs—see Austin et al. [125]. Equivalent English and Arabic versions of the questionnaire (based on the scale items) were created. Three independent academics, all of whom were bilingual in Arabic and English, conducted pre-test evaluations and independent back translations as part of the procedure. Between December 2022 and March 2023, an electronic survey via “Google Forms” was distributed to 1082 SEs. Only 344 useable responses—a response rate of just 3.14%—were obtained from the procedure after numerous emails and phone calls were made. Table 1 displays the respondents’ demographic characteristics.

Table 1.

Demographic profile of the social enterprises.

8. Measures

8.1. Digital Capabilities

The measurement of DC was based on the Zhou and Wu [126] measurement of technical capability, which was adapted for measuring DC by [66]. The measurement contains a five-item Likert scale with options from 1 = “very low” to 5 = “very high” for self-assessment of the enterprise’s capability related to the application of digital technology. This measure of DC is recognized by management scholars and widely applied in the measurement of technology-related capabilities [22]. Table 2 demonstrates the measurement items along with their reference sources.

Table 2.

Description of the study measures.

8.2. Social Innovation Performance

The SIP of SEs was measured using a multi-item reflective scale recently developed and validated by Ko et al., [51]. The measurement of the SIP of SEs varies widely, per context [127]. Most of the authors have used and modified the existing measures of for-profit enterprises’ innovation performance [128]. However, Ko et al.’s [51] measurement of SIP followed a systematic approach to the development and validation of the scale (Cronbach’s alpha ≥ 0.700; AVE ≥ 0.500) to specifically suit the S-ENT context.

8.3. Social Entrepreneurial Orientation

In line with previous research, the present study defines an EO as the culmination of a firm’s structures, procedures, and behaviors, which are mostly exhibited as innovativeness, risk-taking, and proactiveness [91]. It is generally accepted that EO research is performed on firm-level entrepreneurship [92], with the EO dimensions being separate theoretical constructs that do not empirically covariate [96]. However, there is no one optimal approach for conducting EO research [114].

A business needs to perform well across all dimensions, regardless of how they differ from one another [129]. Therefore, it might be required to evaluate the relative importance of each EO characteristic independently in order to properly understand the impact of an EO.

Understanding how different EO aspects influence the DC-SIP correlation is crucial since we are interested in the interaction between DC, an EO, and SIP. Three aspects of the EO—social innovativeness (SI), social proactiveness (SP), and social risk-taking (RT)—were measured and adapted from Kraus et al. [93]. They developed the standard EO constructs for application in S-ENT contexts. Both the SIP and EO scales are set up as five-point Likert scales, where 1 represents “strongly disagree” and 5 represents “strongly agree”.

9. Statistical Analysis and Hypothesis Testing

Using SmartPLS 3.0 software, partial least square (PLS) analysis was conducted to analyze and empirically validate the study model [130]. For evaluating the causal relationships between variables, structural equation modeling (SEM) has been regarded as a good methodological choice [131]. SEM is frequently employed in management and S-ENT research for comparable objectives [132]. Furthermore, several factors influenced our decision to use SEM. First, PLS analysis may test and specify the route models with latent constructs [133] and place fewer constraints on sample size and distribution [134]. Moreover, multicollinearity problems that are frequently linked to multivariate regression analysis can be resolved by PLS-SEM [134]. Furthermore, PLS-SEM offers various benefits over conventional regression techniques [130] as it simultaneously analyses the measurement and the theoretical structural model [134]. The PLS model is usually run in two phases: the structural model is used to investigate the potential relationships between the theoretical constructs, and the measurement model is used to gauge the reliability and validity of the constructs. Accordingly, hypotheses are only accepted if they possess statistically significant routes in the structural model, convergent and discriminant validity in the measurement model, and acceptable levels of reliability [134]. The statistical analysis for the current investigation was conducted following recent PLS-SEM recommendations [130,131].

10. Measurement Model

The analysis started with an estimation of the model. The analysis evaluated the measurement model criteria for convergent validity [average variance extracted (AVE) and indicator reliability], discriminant validity (cross-loading and HTMT), and internal consistency (Cronbach alpha/composite reliability) [135]. The indicator loading values for most factors are greater than 0.70, and the AVE values are greater than the threshold value of 0.500, according to the reliability indicator assessment. The threshold value of 0.70 was exceeded by the Cronbach alpha and composite reliability scores. According to Hair et al.’s [136] guidelines, these values represent meaningful loadings. Meanwhile, to ascertain the discriminatory validity, we employed a matrix and the HTMT (heterotrait–monotrait ratio of correlations) ratio [135]. The popularity of the HTMT ratio has recently eclipsed that of Fornell and Larcker [131]. The test findings showed that while the HTMT value is less than one (Table 3), the square root of the AVE (diagonal) in the Fornell–Larcker matrix is bigger than all other values (Table 4). Consequently, the measuring model’s degree of discriminant validity is deemed appropriate [131,135]. Additionally, by acquiring the AVE values, we evaluated the convergent validity. Because each construct’s square root of AVE is higher than the correlations between the other variable constructs, Table 3 and Table 4 results demonstrate that the model’s discriminating validity is valid [135]. Every AVE value exceeded the 0.50 cutoff [131]. Additionally, all the variable indicators are legitimate according to the PLS models’ outer model/convergent loadings, which are greater than 0.70. Thus, there was no need to eliminate any indicators at this stage.

Table 3.

Measurement model evaluation.

Table 4.

Fornell and Larcker’s criterion (indicating validity and correlations among constructs).

11. Estimation of Common Method Bias

The common method bias variance for the reflective constructs in the study was examined using Harman’s single-factor test. Common method bias, according to Harman [137], only occurs when one factor from factor analysis emerges and accounts for more than half of the variance’s eigenvalue. Consequently, four factors and a first-factor eigenvalue that explained 37.51% of the variance—less than the 50% threshold—were produced using the un-rotated matrix. Consequently, no significant indicators of common method bias were found.

12. Structural Model

Coefficient of Determination (R2)

The ability of exogenous variables to predict the variance in endogenous variable(s) is evaluated using R2 values. The R2 value of each endogenous variable shows how well the variable can be predicted, and its expected value falls between zero and one. According to Hair et al. [130], endogenous variables have a strong, moderate, and weak ability to predict the models, as indicated by their respective R2 values of 0.75, 0.50, and 0.25. The endogenous variable of SIP has a reasonable ability to predict the models (R2 = 0.606), based on the R2 values in Table 5. Alternatively, it may be inferred that 60.60% of the endogenous variable of SIP can be predicted by the exogenous variables of the model (SI, RT, SP, and DC), while the remainder is influenced by variables outside the purview of this study.

Table 5.

Variance explained in the endogenous latent variable (R-square).

13. Structural Equation Modeling

The structural equation model was assessed through 5000 bootstraps utilizing the SmartPLS procedure [138]. Table 6 displays the results of the structural model analysis. It also shows the path coefficient, p-, and t-values results for the hypothesis. Path coefficients reflect the strength of relationships between constructs or latent variables, like regression coefficients. Similarly to indicator weight analysis in regression, each route coefficient’s importance can be assessed using the bootstrapping techniques in PLS-SEM [139].

Table 6.

Summary of direct effects.

Path coefficients less than 0.30, between 0.30 and 0.60, and greater than 0.60 have been identified in the literature as producing moderate, strong, and extremely strong effects, respectively [140]. In light of this and considering the Table 6 results, H1 is not supported [coefficient = 0.287; t = 2.089; ρ-value = p ≥ 0.053].

Given that the nature of the interactions between exogenous and endogenous variables varies between models, both with and without the moderating effect, the indirect relationships of the structural model were assessed using the mediation test for interaction terms [136]. Subsequently, the results of the mediation effects shown in Table 7 revealed that both SP [coefficient = 0.348; t = 3.080; ρ-value = p ≥ 0.018] and SI [coefficient= 0.461; t = 5.017; ρ-value = p ≥ 0.003] positively mediate the DC-SIP relationship. However, the mediation effects of RT were found to be insignificant [coefficient = 0.248; t = 2.030; ρ-value = p ≥ 0.056].

Table 7.

Test of mediation.

Furthermore, the cross-validated redundancy (Q2) for all the endogenous variables (SIP, SP, SI, and RT) was greater than 0.000. As a result, the current study’s findings were both significant, and the study model’s predictive relevance was achieved [136].

14. Results and Discussion

In the current digitally transforming entrepreneurship scenario, the present study proposes and analyses the theoretical model linking DC, an EO, and SIP in SEs. To explore the empirical evidence, the study investigated the direct effect of the DC and SIP of SEs along with considering how the various EO constructs individually mediate the DC-SIP relationship in SEs. The study’s conceptual model is inclined with the theoretical preposition of resource-based theory (RBV) [38] and its extension—dynamic capabilities theory [21].

At the outset, it was assumed that DC has a direct and significant impact on SIP in the SEs. This is to say, the higher the degree of DC, the better the context for the occurrence of SIP. The structural model results, however, report DC as having an indirect rather than direct relationship with the SIP of SEs. Alternatively, it can be contended that DC as dynamic capabilities, may enable the SEs to improve their SIP, but they alone are insufficient to achieve SIP. This resembles the resource–capability–performance perspective that asserts that dynamic capabilities are equifinal and insufficient on their own to establish a foundation for competitive advantage [25]. DC complements other capabilities (like, for example, functional capabilities) to positively impact the firm performance [141]. Thus, the DC–firm performance association might be shaped by other contingencies. Building on the same logic, we subsequently seek to deepen the understanding of the relationship between DC and SIP by examining the mediation of an EO. The mediation effects of the EO were theorized on account of its ability to enhance the market effectiveness and resource orchestration of SEs in the current dynamic business environments [120]. Thus, the subsequent hypotheses tested how the DC-SIP relationship is mediated through the three individual constructs of firm-level EO. The statistical testing of the different paths revealed that not all the constructs of EO mediate the above relationship. The EO constructs of social innovativeness and social proactiveness were found to fully mediate the relationship, whereas the mediation effects of social risk-taking were not established. Conclusively, the present study establishes that when SEs appropriately develop and harness DC, they can improve their SIP, and some EO constructs positively influence the use of DC, which may be related to an increase in SIP. Alternatively, it might be stated that SEs can strengthen their capacity to exploit DC effectively by reconfiguring their available resources and strategies underpinning the specific EO constructs. This affirms the existing literature’s suggestions that view a firm’s strategic orientation as a crucial component of the organizational context in which the firm engages in innovation activities [99]. Given that an EO improves a company’s capacity to identify the resources needed for innovation [98], our results establish the role of an EO in the context of the DC-SIP nexus in SEs. Past studies contend that resources and capabilities are exposed to market processes through activities, routines, and business processes, where their true worth and capacity to create competitive advantages are recognized [105].

The EO has been seen to promote or increase innovation in commercial companies [96], and a recent study has established this role for EO in the S-ENT context as well [97]. However, considering the RBV of the firm, our results indicating that the EO construct mediates the DC-SIP relationship in SEs present a novel understanding of the role of the EO in influencing SIP in the digital era. Furthermore, the individual effects of social innovativeness, and proactiveness as fully mediating the DC-SIP relationship, confirms the fundamental belief that strategic orientation facilitates entrepreneurship strategy [101] and the consequent ability of the firm to experiment with new technologies and capitalize on capabilities and opportunities in S-ENT [96]. Thus, our findings of DC are dynamic capabilities that when combined with EO improve SIP in SEs offer novel insights in our understanding of SIP in SEs. According to Wales et al. [114], proactiveness shows that one can anticipate potential issues and adjust to change, which makes it suitable for firms’ DT missions [119] and social enterprise performance [118]. These findings support the positive mediation results for social innovativeness. Similar to this, the organization’s social innovation and proactiveness include seeking out and supporting the conceptualization of completely new ideas, processes, and products as well as taking a fresh approach to already-existing ideas, processes, and goods [96]. According to Runyan et al. [111], these kinds of commercial endeavors would significantly promote and hasten the creation of novel and inventive company strategies and technology. The fact that innovativeness enables firm to solve problems through workplace innovation [112] and launch new initiatives to compete, such as digital transformation [142], may, therefore, be attributed to the new insights regarding social innovativeness as mediating the DC-SIP. It may, therefore, be argued that social innovation and proactiveness will allow SEs to rethink and fundamentally renew their critical DC in order to enhance their SIP [103].

Although risk-taking is thought to promote innovation in businesses [42], the current study did not support the mediation impact of risk-taking in the DC-SIP connection. The results of this study are a little surprising, as innovation and proactivity both depend on taking risks [118]. This may be the result of the fact that SEs have been shown to perceive and assess risk differently compared to other enterprises [143]. For example, Beekman et al. [144] claim that SEs tend to be more cautious about fundraising during times when creativity and innovation are most required, which represents a certain failure to accept risks. Likewise, the recent study by Syrjä et al. [145] contends that despite their risk aversion, SEs are willing to self-correct, be proactive, and be innovative in the search for new revenue streams and in the resolution of social problems. Overall, the EO construct’s varied results are consistent with research by authors like do Adro et al. [30] and Kraus et al. [93], who note that the influence of the EO sub-dimensions may vary.

15. Conclusions

SEs are accredited as the primary social entities that develop and implement social innovations [2,6]. Remarkably, the extant literature indicates that social innovation, as an outcome of S-ENT, is the primary driver of SEs. Social innovation equips SEs to not only develop solutions to social issues [5,49,51], but also enables them to differentiate themselves in the marketplace and achieve long-term sustainability [6]. As a result, social innovation is considered mandatory for social as well as financial performance in SEs [8]. Nevertheless, considering the inherent difficulties in strategically managing the double- or TBL objectives of SEs [8,58], the SEs encounter multidimensional challenges as they work to build their businesses and create social value [44]. However, despite significant efforts being expended in defining what social innovation is, relatively little attention is being paid to the actors and mechanisms that bring it about [144].

This study is the first of its kind to design and evaluate a theoretical model involving DC, an EO, and SIP in SEs amid the current digitally transforming entrepreneurship scenario. Specifically, the study examined the direct effect of the DC and SIP of SEs along with considering how the individual constructs of a firm-level EO mediate the aforementioned relationships in SEs. By doing this, the study claims to add several fresh perspectives to the body of extant literature. First off, the research is one of the few studies that focus on examining innovation activities within SEs [49,51] and that interpret social innovation as a social enterprise’s competitive strategy [6,8]. Meanwhile, the study is the first to scientifically show that DC as strategic dynamic capabilities have an indirect favorable relationship with SIP in SEs. Because digitization has recently presented a new impetus and challenges for social value creation [18], it is crucial to expand the knowledge about DC in the context of SEs. By doing so, this study serves as the beginning of what may eventually grow to be a significant research topic that examines the antecedent factors that lead to SIP in SEs. Theoretically, the findings extend the theory of dynamic capability [21] by illustrating how DC enables SEs to improve their SIP. Thirdly, this study goes a step further by investigating how individual constructs of EO can mediate the link between DC and SIP. Although the importance of an EO in processes that may result in innovation outcomes has been partially acknowledged in the S-ENT literature [33,36,57], its existence and implications for the digital transformation in SEs are still largely untested. The relationships between SEO, DC, and SIP could be further extended and conceptualized as key constructs for DT in SEs, thus extending the scope of EO research. In practice, the study emphasizes the importance of bolstering enterprises’ capacities to exploit DC effectively by reconfiguring their available resources and the strategies underpinning their EO, given the growing necessity for social innovation organizations to develop and implement DT strategies. In particular, it is critical that SEs strategically apply their companies’ innovation, proactivity, and risk-taking to achieve their SIP objectives. Nevertheless, given the different implications of each sub-dimension, managers should refrain from generalizing about the equal impact of all EO dimensions on SIP. Following the social enterprise’s DC, a specific EO to one SIP goal may necessitate a different intensity of the three EO dimensions. Stated differently, the managers of SEs ought to concentrate on discovering strategies to encourage their firms’ strategic orientations, as this may have a favorable impact on the utilization of DC and could be linked to a rise in social innovation endeavors, which could ultimately lead to a rise in SIP. On the other hand, the study’s conclusions highlight the necessity of “strategizing” the DC inside SEs. The results specifically suggest bolstering the strategic and entrepreneurial capacities of social enterprises in order to enable the attainment of SIP in SEs. This has implications specifically for SEs in Saudi Arabia, which is rapidly moving toward the dual transitions of digital and sustainable development, in accordance with several developed countries [39]. Accordingly, digital technologies have become increasingly important in any nation’s endeavor to build a more competitive, inclusive, and, most importantly, sustainable economy and society [146]. Consequently, despite the ongoing challenges facing SE practices in Saudi Arabia, small enterprises persistently endeavor to adopt socially and environmentally innovative methods [147,148]. In light of the aforementioned, Saudi Arabia’s SEs can leverage DC to help them meet the demands of the digital business environment and obtain a competitive edge. Overall, the study’s conclusions offer a timely reminder for creating and utilizing social enterprises’ strategic directions toward SIP objectives. Additionally, the results have relevance for contemporary patterns in terms of the demand for digitization across a variety of industries and organization types amid “Society 5.0” and “Industry 5.0” [1,149], and thus facilitate the broadening of the consequences of digitization toward innovation and entrepreneurship [150].

16. Limitations and Future Research

The current study has important theoretical and practical consequences, but it has some drawbacks as well. Firstly, the results are based on cross-sectional data, which introduces causality errors and encourages endogeneity errors in the links between the constructs. Future researchers may conduct longitudinal studies to correct these flaws. Secondly, due to its design, this research only analyses the subjective measure of SIP. Future researchers might think about combining the longitudinal approaches with more objective SIP metrics, along with considering the DC and financial performance of the SEs. Thirdly, the association between DC and SIP may be better understood by further study of our explanations as well as the investigation of other mediators and moderators.

Future studies could also look at the effects of control variables (firm age, S-ENT sector, etc.) that were not studied in the current analysis, considering the risk of endogeneity and collinearity errors which could have been further complicated by the extremely skewed item responses in each category, thus reducing the model’s succinctness. Fifthly, although there was an absence of any country-specific features in our model, given the diversity of SEs across regions, future research may need to take context effects into account.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, M.S.S.; Methodology, G.A.; Software, F.O.; Validation, F.O.; Formal analysis, S.A.; Resources, G.A.; Data curation, F.O.; Writing—original draft, M.S.S.; Writing—review & editing, S.A.; Supervision, G.A.; Project administration, S.A. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

This study was conducted with the informed consent of all participants.

Data Availability Statement

Data is unavailable due to privacy or ethical restrictions.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Carayannis, E.G.; Morawska-Jancelewicz, J. The Futures of Europe: Society 5.0 and Industry 5.0 as Driving Forces of Future Universities. J. Knowl. Econ. 2022, 13, 3445–3471. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Wit, A.; Mensink, W.; Einarsson, T.; Bekkers, R. Beyond Service Production: Volunteering for Social Innovation. Nonprofit Volunt. Sect. Q. 2017, 48 (Suppl. S2), 52S–71S. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gasparin, M.; Green, W.; Lilley, S.; Quinn, M.; Saren, M.; Schinckus, C. Business as Unusual: A Business Model for Social Innovation. J. Bus. Res. 2021, 125, 698–709. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Phills, J.A.; Deiglmeier, K.; Miller, D.T. Rediscovering social innovation. Stanf. Soc. Innov. Rev. 2008, 6, 34–43. [Google Scholar]

- Mulgan, G. The Process of Social Innovation. Innov. Technol. Gov. Glob. 2006, 1, 145–162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weerawardena, J.; Mort, G.S. Competitive Strategy in Socially Entrepreneurial Nonprofit Organizations: Innovation and Differentiation. J. Public Policy Mark. 2012, 31, 91–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miao, C.; Coombs, J.E.; Qian, S.; Sirmon, D.G. The Mediating Role of Entrepreneurial Orientation: A Meta-Analysis of Resource Orchestration and Cultural Contingencies. J. Bus. Res. 2017, 77, 68–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Glaveli, N.; Geormas, K. Doing Well and Doing Good. Int. J. Entrep. Behav. Res. 2017, 24, 147–170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hota, P.K.; Subramanian, B.; Narayanamurthy, G. Mapping the Intellectual Structure of Social Entrepreneurship Research: A Citation/Co-Citation Analysis. J. Bus. Ethics 2019, 166, 89–114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nardini, G.; Bublitz, M.G.; Butler, C.; Croom-Raley, S.; Edson Escalas, J.; Hansen, J.; Peracchio, L.A. Scaling Social Impact: Marketing to Grow Nonprofit Solutions. J. Public Policy Mark. 2022, 41, 254–276. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rayna, T.; Striukova, L. Open Social Innovation Dynamics and Impact: Exploratory Study of a Fab Lab Network. RD Manag. 2019, 49, 383–395. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Covin, J.G.; Miller, D. International Entrepreneurial Orientation: Conceptual Considerations, Research Themes, Measurement Issues, and Future Research Directions. Entrep. Theory Pract. 2014, 38, 11–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wessel, L.; Baiyere, A.; Ologeanu-Taddei, R.; Cha, J.; Blegind Jensen, T. Unpacking the Difference Between Digital Transformation and IT-Enabled Organizational Transformation. J. Assoc. Inf. Syst. 2021, 22, 102–129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Volberda, H.W.; Khanagha, S.; Baden-Fuller, C.; Mihalache, O.R.; Birkinshaw, J. Strategizing in a Digital World: Overcoming Cognitive Barriers, Reconfiguring Routines and Introducing New Organizational Forms. Long Range Plan. 2021, 54, 102110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Z.; Chen, H.; Mo, B. Can Digital Finance Promote Urban Innovation? Evidence from China. Borsa Istanb. Rev. 2023, 23, 285–296. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Warner, K.S.R.; Wäger, M. Building Dynamic Capabilities for Digital Transformation: An Ongoing Process of Strategic Renewal. Long Range Plan. 2019, 52, 326–349. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gagliardi, D.; Psarra, F.; Wintjes, R.; Trendafili, K.; Pineda Mendoza, J.; Haaland, K.; Turkeli, S.; Giotitsas, C.; Pazaitis, A.; Niglia, F.; et al. Digital technologies and the social economy: New technologies and digitisation: Opportunities and challenges for the social economy and social enterprises. Eur. Comm. 2020, 14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deganis, I.; Haghian, P.Z.; Tagashira, M. Leveraging Digital Technologies for Social Inclusion; Policy Brief No. 92; United Nations Department of Economic and Social Affairs: New York, NY, USA, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Zhou, X.; Cai, Z.; Tan, K.H.; Zhang, L.; Du, J.; Song, M. Technological Innovation and Structural Change for Economic Development in China as an Emerging Market. Technol. Forecast. Soc. Change 2021, 167, 120671. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Annarelli, A.; Battistella, C.; Nonino, F.; Parida, V.; Pessot, E. Literature Review on Digitalization Capabilities: Co-Citation Analysis of Antecedents, Conceptualization and Consequences. Technol. Forecast. Soc. Change 2021, 166, 120635. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Libert, B.; Beck, M.; Wind, J. The Network Imperative: How to Survive and Grow in the Age of Digital Business Models; Harvard Business Review Press: Oxford, UK, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Zhen, Z.; Yousaf, Z.; Radulescu, M.; Yasir, M. Nexus of Digital Organizational Culture, Capabilities, Organizational Readiness, and Innovation: Investigation of SMEs Operating in the Digital Economy. Sustainability 2021, 13, 720. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parida, V.; Sjödin, D.R.; Lenka, S.; Wincent, J. Developing Global Service Innovation Capabilities: How Global Manufacturers Address the Challenges of Market Heterogeneity. Res. Technol. Manag. 2015, 58, 35–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lenka, S.; Parida, V.; Wincent, J. Digitalization Capabilities as Enablers of Value Co-Creation in Servitizing Firms. Psychol. Mark. 2016, 34, 92–100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Loureiro, R.; Ferreira, J.J.M.; Simões, J. Approaches to Measuring Dynamic Capabilities: Theoretical Insights and the Research Agenda. J. Eng. Technol. Manag. 2021, 62, 101657. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, X.-M.; Chen, K.; Liu, J.-T. Exploring How Organizational Capabilities Contribute to the Performance of Social Enterprises: Insights from China. Sustainability 2022, 14, 4363. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rêgo, B.S.; Jayantilal, S.; Ferreira, J.J.; Carayannis, E.G. Digital Transformation and Strategic Management: A Systematic Review of the Literature. J. Knowl. Econ. 2021, 13, 3195–3222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mourtzis, D. Simulation in the Design and Operation of Manufacturing Systems: State of the Art and New Trends. Int. J. Prod. Res. 2019, 58, 1927–1949. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Björkdahl, J. Strategies for Digitalization in Manufacturing Firms. Calif. Manag. Rev. 2020, 62, 17–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Do Adro, F.; Fernandes, C.I.; Veiga, P.M.; Kraus, S. Social Entrepreneurship Orientation and Performance in Non-Profit Organizations. Int. Entrep. Manag. J. 2021, 17, 1591–1618. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zimmer, M.P.; Baiyere, A.; Salmela, H. Digital Workplace Transformation: Subtraction Logic as Deinstitutionalising the Taken-for-Granted. J. Strateg. Inf. Syst. 2023, 32, 101757. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sulphey, M.M.; Salim, A. Development of a Tool to Measure Social Entrepreneurial Orientation. J. Entrep. Emerg. Econ. 2020, 13, 231–253. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lall, S.A.; Park, J. How Social Ventures Grow: Understanding the Role of Philanthropic Grants in Scaling Social Entrepreneurship. Bus. Soc. 2020, 61, 3–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Autio, E.; Nambisan, S.; Thomas, L.D.W.; Wright, M. Digital Affordances, Spatial Affordances, and the Genesis of Entrepreneurial Ecosystems. Strateg. Entrep. J. 2018, 12, 72–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, K.Z.; Yim, C.K.; Tse, D.K. The Effects of Strategic Orientations on Technology- and Market-Based Breakthrough Innovations. J. Mark. 2005, 69, 42–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu Sam, C.-H.; Huang, C.-E. Discovering Differences in the Relationship among Social Entrepreneurial Orientation, Extensions to Market Orientation and Value Co-Creation—The Moderating Role of Social Entrepreneurial Self-Efficacy. J. Hosp. Tour. Manag. 2020, 42, 97–106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Teece, D.J.; Pisano, G.; Shuen, A. Dynamic Capabilities and Strategic Management. Strateg. Manag. J. 1997, 18, 509–533. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burisch, R.; Wohlgemuth, V. Blind Spots of Dynamic Capabilities: A Systems Theoretic Perspective. J. Innov. Knowl. 2016, 1, 109–116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- European Commission. Digital Economy and Society Index (DESI) 2020 Thematic Chapters. 2021. Available online: https://eufordigital.eu/wp-content/uploads/2020/06/DESI2020Thematicchapters-FullEuropeanAnalysis.pdf (accessed on 7 March 2023).

- Domanski, D.; Howaldt, J.; Kaletka, C. A Comprehensive Concept of Social Innovation and Its Implications for the Local Context—On the Growing Importance of Social Innovation Ecosystems and Infrastructures. Eur. Plan. Stud. 2019, 28, 454–474. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Borzaga, C.; Bodini, R.; Carini, C.; Depedri, S.; Galera, G.; Salvatori, G. Europe in Transition: The Role of Social Cooperatives and Social Enterprises. SSRN Electron. J. 2014. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.-H.; Huang, J.-W.; Tsai, M.-T. Entrepreneurial Orientation and Firm Performance: The Role of Knowledge Creation Process. Ind. Mark. Manag. 2009, 38, 440–449. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Suykens, B.; Verschuere, B. Nonprofit Commercialization. In International Encyclopedia of Civil Society; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Dhondt, S.; Oeij, P.R.A.; Schröder, A. Resources, Constraints, and Capabilities; Sozialforschungsstelle TU Dortmund: Dortmund, Germany, 2018; pp. 74–77. [Google Scholar]

- Oeij, P.R.A.; van der Torre, W.; Vaas, F.; Dhondt, S. Understanding Social Innovation as an Innovation Process: Applying the Innovation Journey Model. J. Bus. Res. 2019, 101, 243–254. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dees, J.G. Creating large-scale change: Not ‘can’ but ‘how’. What Matters 2010, 4. [Google Scholar]

- Enciso-Santocildes, M.; Echaniz-Barrondo, A.; Gómez-Urquijo, L. Social Innovation and Employment in the Digital Age: The Case of the Connect Employment Shuttles in Spain. Int. J. Innov. Stud. 2021, 5, 175–189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morawska-Jancelewicz, J. The Role of Universities in Social Innovation Within Quadruple/Quintuple Helix Model: Practical Implications from Polish Experience. J. Knowl. Econ. 2021, 13, 2230–2271. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shockley, G.E.; Nicholls, A.; Murdock, A. (Eds.) Social Innovation: Blurring Boundaries to Reconfigure Markets. VOLUNTAS Int. J. Volunt. Nonprofit Organ. 2013, 24, 1209–1211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Perrini, F.; Vurro, C.; Costanzo, L.A. A Process-Based View of Social Entrepreneurship: From Opportunity Identification to Scaling-up Social Change in the Case of San Patrignano. Entrep. Reg. Dev. 2010, 22, 515–534. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ko, W.W.; Liu, G.; Wan Yusoff, W.T.; Che Mat, C.R. Social Entrepreneurial Passion and Social Innovation Performance. Nonprofit Volunt. Sect. Q. 2019, 48, 759–783. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miller, T.L.; Grimes, M.G.; McMullen, J.S.; Vogus, T.J. Venturing for Others with Heart and Head: How Compassion Encourages Social Entrepreneurship. Acad. Manag. Rev. 2012, 37, 616–640. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peredo, A.M.; Chrisman, J.J. Toward a Theory of Community-Based Enterprise. Acad. Manag. Rev. 2006, 31, 309–328. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shahid Satar, M. Towards Developing a Comprehensive Model for Describing the Phenomenon of Community Engagement in Social Enterprises. J. Enterprising Communities People Places Glob. Econ. 2019, 13, 472–488. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lurtz, K.; Kreutzer, K. Entrepreneurial Orientation and Social Venture Creation in Nonprofit Organizations. Nonprofit Volunt. Sect. Q. 2016, 46, 92–115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Satar, M.S.; Natasha, S. Individual Social Entrepreneurship Orientation: Towards Development of a Measurement Scale. Asia Pac. J. Innov. Entrep. 2019, 13, 49–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Indriastuti, H. Entrepreneurial inattentiveness, relational capabilities and value co-creation to enhance marketing performance. Humanit. Soc. Sci. Rev. 2019, 7, 181–188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Satar, M.S. Sustainability and Triple Bottom Line Planning in Social Enterprises: Developing the Guidelines for Social Entrepreneurs. Int. J. Sustain. Dev. Plan. 2022, 17, 813–821. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, G.; Takeda, S.; Ko, W.-W. Strategic Orientation and Social Enterprise Performance. Nonprofit Volunt. Sect. Q. 2012, 43, 480–501. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barney, J. Firm Resources and Sustained Competitive Advantage. J. Manag. 1991, 17, 99–120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Walk, M.; Schinnenburg, H.; Handy, F. Missing in Action: Strategic Human Resource Management in German Nonprofits. VOLUNTAS Int. J. Volunt. Nonprofit Organ. 2013, 25, 991–1021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hirvonen, J.; Majuri, M. Digital Capabilities in Manufacturing SMEs. Procedia Manuf. 2020, 51, 1283–1289. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amit, R.; Schoemaker, P.J.H. Strategic Assets and Organizational Rent. Strateg. Manag. J. 1993, 14, 33–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maldonado-Guzmán, G.; Garza-Reyes, J.A.; Pinzón-Castro, S.Y.; Kumar, V. Innovation Capabilities and Performance: Are They Truly Linked in SMEs? Int. J. Innov. Sci. 2019, 11, 48–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sainio, L.-M.; Ritala, P.; Hurmelinna-Laukkanen, P. Constituents of Radical Innovation—Exploring the Role of Strategic Orientations and Market Uncertainty. Technovation 2012, 32, 591–599. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khin, S.; Ho, T.C. Digital Technology, Digital Capability and Organizational Performance. Int. J. Innov. Sci. 2019, 11, 177–195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bughin, J.R.; van Zeebroeck, N. The Case for Offensive Strategies in Response to Digital Disruption. SSRN Electron. J. 2017. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Porter, M.E.; Heppelmann, J.E. How smart, connected products are transforming competition. Harv. Bus. Rev. 2014, 92, 64–88. [Google Scholar]

- Almeida, F.; Duarte Santos, J.; Augusto Monteiro, J. The Challenges and Opportunities in the Digitalization of Companies in a Post-COVID-19 World. IEEE Eng. Manag. Rev. 2020, 48, 97–103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, J.; Zhou, J.; Cheng, Y. Conceptual Method and Empirical Practice of Building Digital Capability of Industrial Enterprises in the Digital Age. IEEE Trans. Eng. Manag. 2022, 69, 1902–1916. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kuzior, A.; Kettler, K.; Rąb, Ł. Digitalization of Work and Human Resources Processes as a Way to Create a Sustainable and Ethical Organization. Energies 2021, 15, 172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Proksch, D.; Rosin, A.F.; Stubner, S.; Pinkwart, A. The Influence of a Digital Strategy on the Digitalization of New Ventures: The Mediating Effect of Digital Capabilities and a Digital Culture. J. Small Bus. Manag. 2021, 62, 1–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elia, G.; Margherita, A.; Passiante, G. Digital Entrepreneurship Ecosystem: How Digital Technologies and Collective Intelligence Are Reshaping the Entrepreneurial Process. Technol. Forecast. Soc. Change 2020, 150, 119791. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, D.; Chen, S.; Chou, T. Resource Fit in Digital Transformation. Manag. Decis. 2011, 49, 1728–1742. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vial, G. Understanding Digital Transformation: A Review and a Research Agenda. J. Strateg. Inf. Syst. 2019, 28, 118–144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- George, G.; Merrill, R.K.; Schillebeeckx, S.J.D. Digital Sustainability and Entrepreneurship: How Digital Innovations Are Helping Tackle Climate Change and Sustainable Development. Entrep. Theory Pract. 2020, 45, 999–1027. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gast, J.; Gundolf, K.; Cesinger, B. Doing Business in a Green Way: A Systematic Review of the Ecological Sustainability Entrepreneurship Literature and Future Research Directions. J. Clean. Prod. 2017, 147, 44–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vrontis, D.; Chaudhuri, R.; Chatterjee, S. Adoption of Digital Technologies by SMEs for Sustainability and Value Creation: Moderating Role of Entrepreneurial Orientation. Sustainability 2022, 14, 7949. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Torres, P.; Augusto, M. Digitalisation, Social Entrepreneurship and National Well-Being. Technol. Forecast. Soc. Chang. 2020, 161, 120279. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- ESCAP United Nations. Measuring the Digital Divide in the Asia-Pacific Region for the United Nations Economic and Social Commission for Asia and the Pacific (ESCAP); ESCAP: Bangkok, Thailand, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Maiolini, R.; Marra, A.; Baldassarri, C.; Carlei, V. Digital Technologies for Social Innovation: An Empirical Recognition on the New Enablers. J. Technol. Manag. Innov. 2016, 11, 22–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vasin, S.M.; Gamidullaeva, L.A.; Rostovskaya, T.K. The Challenge of Social Innovation: Approaches and Key Mechanisms of Development. Eur. Res. Stud. J. 2017, 20, 25–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Wang, C.L.; Ahmed, P.K. Dynamic Capabilities: A Review and Research Agenda. Int. J. Manag. Rev. 2007, 9, 31–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shen, L.; Zhang, X.; Liu, H. Digital Technology Adoption, Digital Dynamic Capability, and Digital Transformation Performance of Textile Industry: Moderating Role of Digital Innovation Orientation. Manag. Decis. Econ. 2021, 43, 2038–2054. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aboelmaged, M.G.; Hashem, G. Absorptive capacity and green innovation adoption in SMEs: The mediating effects of sustainable organisational capabilities. J. Clean. Prod. 2019, 220, 853–863. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chong, C.-L.; Rasid, S.Z.A.; Khalid, H.B.; Ramayah, T. Big Data Analytics Capability for Competitive Advantage and Firm Performance in Malaysian Manufacturing Firms. SSRN Electron. J. 2022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arfi, W.; Hikkerova, L.; Sahut, J.-M. External Knowledge Sources, Green Innovation and Performance. Technol. Forecast. Soc. Change 2018, 129, 210–220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bag, S.; Pretorius, J.H.C.; Gupta, S.; Dwivedi, Y.K. Role of Institutional Pressures and Resources in the Adoption of Big Data Analytics Powered Artificial Intelligence, Sustainable Manufacturing Practices and Circular Economy Capabilities. Technol. Forecast. Soc. Change 2021, 163, 120420. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharma, M.; Kamble, S.; Mani, V.; Sehrawat, R.; Belhadi, A.; Sharma, V. Industry 4.0 Adoption for Sustainability in Multi-Tier Manufacturing Supply Chain in Emerging Economies. J. Clean. Prod. 2021, 281, 125013. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhatti, M.A.; Aljoghaiman, A.; Kaliani Sundram, V.P.; Ghouri, A. Effect of Industry 4 Emerging Technology on Environmental Sustainability of Textile Companies in Saudi Arabia: Mediating Role of Green Supply Chain Management. Manag. Environ. Qual. Int. J. 2023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Covin, J.G.; Slevin, D.P. Strategic Management of Small Firms in Hostile and Benign Environments. Strateg. Manag. J. 1989, 10, 75–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Covin, J.G.; Wales, W.J. Crafting High-Impact Entrepreneurial Orientation Research: Some Suggested Guidelines. Entrep. Theory Pract. 2018, 43, 3–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kraus, S.; Niemand, T.; Halberstadt, J.; Shaw, E.; Syrjä, P. Social Entrepreneurship Orientation: Development of a Measurement Scale. Int. J. Entrep. Behav. Res. 2017, 23, 977–997. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Choi, S.B.; Williams, C. Entrepreneurial Orientation and Performance: Mediating Effects of Technology and Marketing Action across Industry Types. Ind. Innov. 2016, 23, 673–693. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harris, S.G. The Fifth Discipline: The Art and Practice of the Learning Organization, by Peter Senge, New York: Doubleday/Currency, 1990. Hum. Resour. Manag. 1990, 29, 343–348. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lumpkin, G.T.; Dess, G.G. Clarifying the Entrepreneurial Orientation Construct and Linking It to Performance. Acad. Manag. Rev. 1996, 21, 135–172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oduro, S. Entrepreneurial Orientation and Innovation Performance of Social Enterprises in an Emerging Economy. J. Res. Mark. Entrep. 2022, 24, 312–336. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, W.; Chang, M.; Chen, C. Promoting Innovation through the Accumulation of Intellectual Capital, Social Capital, and Entrepreneurial Orientation. RD Manag. 2008, 38, 265–277. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, C.C.J.; Huizingh, E.K.R.E. When Is Open Innovation Beneficial? The Role of Strategic Orientation. J. Prod. Innov. Manag. 2014, 31, 1235–1253. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dess, G.G.; Lumpkin, G.T.; Covin, J.G. Entrepreneurial Strategy Making and Firm Performance: Tests of Contingency and Configurational Models. Strateg. Manag. J. 1997, 18, 677–695. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miller, D.; Friesen, P.H. Innovation in Conservative and Entrepreneurial Firms: Two Models of Strategic Momentum. Strateg. Manag. J. 1982, 3, 1–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Visser, T.; van Scheers, L. How Important Is It for Family Businesses to Maintain a Strong Entrepreneurial Orientation over Time? Management 2020, 25, 235–250. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nadkarni, S.; Prügl, R. Digital Transformation: A Review, Synthesis and Opportunities for Future Research. Manag. Rev. Q. 2020, 71, 233–341. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nambisan, S. Information Technology and Product/Service Innovation: A Brief Assessment and Some Suggestions for Future Research. J. Assoc. Inf. Syst. 2013, 14, 215–226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ray, G.; Barney, J.B.; Muhanna, W.A. Capabilities, Business Processes, and Competitive Advantage: Choosing the Dependent Variable in Empirical Tests of the Resource-based View. Strateg. Manag. J. 2003, 25, 23–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]