1. Introduction

In the early 2000s, Jim O’Neill, a renowned economist, recognized the four fast-growing economies that are anticipated to dominate the global economy by 2050 and referred to them as the BRIC (i.e., Brazil, Russian Federation, India, and China). Following this, South Africa was discerned as a promising and strategic emerging economy and subsequently added to the BRIC countries in 2010 [

1,

2]. These five BRICS countries are among the 193 United Nations (UN) member states [

3]. In September 2015, the UN General Assembly Summit promulgated what has been termed, the “17 Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs)” [

3,

4,

5,

6]. Of interest to this study are SDGs 1, 8, and 9, which relate to the ending of poverty in all its forms everywhere; the promotion of sustained, inclusive, and sustainable economic growth, full and productive employment and decent work for all; and the building of resilient infrastructure, the promotion of inclusive and sustainable industrialization, and the fostering of innovation, respectively [

3]. By their association with the UN, the five BRICS countries are obliged to contribute to the attainment of the SDGs.

The attainment of the SDGs requires BRICS economies to adequately grow their economies and create jobs for their citizens to lift them out of poverty and disparity. Although the other three BRICS countries, namely Russia, India, and China, appear to be doing well when measured by economic growth in real GDP terms, Brazil and South Africa are lagging [

1,

2,

7]. South Africa has been grappling with slow economic growth; high unemployment rates (the youth unemployment rate has been reported at 46.5% recently); energy crises; crime; poverty; and other economic and social ills for decades [

1,

2,

8,

9]. Mwakalila [

10] posits that high unemployment rates encourage nefarious activities, social unrest, poor living conditions, and migration to other countries.

Russia, India, and China’s economies grew by approximately 7% in GDP in recent years, and these countries managed to create a substantial number of jobs and lift millions of their citizens out of poverty [

1,

7,

11]. Habiyaremye, Kruss, and Booyens [

12] note that part of China’s strategy to grow its economy at such a remarkable rate and pace entailed modernizing the economic structures of rural areas. This translated into improved living conditions for 800 million people in 40 years.

The South African economy grew by approximately 1–2% in recent years, and this minimal growth could not translate into notable job creation and poverty alleviation [

1,

11]. Earlier studies by Leshoro [

13] and Mahadea [

14] revealed that in South Africa, the increase in real GDP is not translating into an increase in employment because the increase in real GDP is a result of the increase in the economic activities of existing firms and labor.

Stagnant economic growth and high unemployment rates not only negatively affect the well-being of South Africans in both rural and urban areas but also rescind progress in attaining SDGs 1, 8, and 9. Thus, effective mechanisms through which economic growth and job creation can be stimulated have to be fostered. It has been propagated by scholars and practitioners that entrepreneurship and innovation are potent tools that can be harnessed to transform rural areas, grow rural economies, create jobs, and enhance the prospects of attaining the SDGs (see [

7,

11,

12,

15,

16,

17]). Mahadea [

14] and Mulibana and Rena [

18], explained that new jobs can be created through entrepreneurship and innovation, as effective entrepreneurship and innovation often lead to the creation of new business ventures, industries, and job opportunities. Despite this observation, there is still a debate pertaining to the relationship between entrepreneurship, innovation, and economic growth, with some scholars asserting that there is a positive relationship between entrepreneurship, innovation, and economic growth Whereas others argue that there is a negative relationship, particularly because entrepreneurship and innovation are not part of the neoclassical growth model, which discerns capital and labor as major contributors to production [

7]. Moreover, entrepreneurship and innovation success are not guaranteed. Entrepreneurs and innovators may fail, but the benefits of successful entrepreneurship and innovation are colossal and should serve as a motive to foster entrepreneurship and innovation. The likes of Elon Musk, Aliko Dangote, Patrice Motsepe, Jack Ma, and Jeff Bezos are just some of the examples of what successful entrepreneurs and innovators are capable of.

In light of the economic and societal benefits (including the attainment of SDGs) that can be accrued from effective entrepreneurship and innovation, these two disciplines garnered attention from many researchers, policymakers, and practitioners alike across the globe for virtually a century. Nonetheless, the entrepreneurship and innovation literature has mostly focused on urban areas, as entrepreneurship and innovation have been propagated as endeavors that are relatively necessary for densely populated areasand rural areas have often been excluded from entrepreneurship and innovation-oriented national development initiatives and research [

16,

19]. Subsequently, there is a paucity of literature on rural entrepreneurship and innovation in the BRICS economies.

Moreover, there has not been a review of the literature on rural entrepreneurship and innovation in South Africa. Lokuge [

20], Ramoroka [

21], and Yin, Chen, and Li [

22] observed that research on entrepreneurship and innovation paid attention to urban areas and R&D-based innovations rather than rural areas. Nonetheless, addressing problems in rural areas is critical for stability and people’s welfare in developing countries [

22,

23]. Approximately 19 million South Africans live in rural areas, and a substantial share of these people live in impoverished conditions [

24]. Thus, extending effective entrepreneurship and innovation to rural areas will help to end poverty, stimulate local economic development, create jobs, foster industrialization, and modernize rural areas. All of these efforts can enhance the prospects of attaining SDGs 1, 8, and 9. This doctrine was also corroborated by Habiyaremye, Kruss, and Booyens [

12].

Thus, within the context of the agency theory and the Triple Helix Model of industrial policy, this paper focuses on systematically reviewing the literature on rural entrepreneurship and innovation in the Republic of South Africa to: understand it; discern rural entrepreneurship and innovation challenges that require policy and practice intervention; share insights; and present recommendations for future research and practice.

From the identified research problem, we formulated the following research questions: What does the existing literature reveal about rural entrepreneurship and innovation in South Africa? What are the challenges facing rural entrepreneurship and innovation in South Africa? What are the insights that can be shared? What are the opportunities for future research?

In answering the aforementioned research questions, this paper contributes to the expansion of the literature on rural entrepreneurship and innovation by systematically reviewing the literature on rural entrepreneurship and innovation in the BRICS economies with a specific focus on South Africa. This paper also identifies challenges pertaining to rural entrepreneurship and innovation and research gaps/opportunities. It also shares insights and makes recommendations for future research and practice.

This manuscript is composed of seven sections, starting with the introduction section. This will be followed by the literature review section; theoretical framework section; materials and methods section; presentation and discussion of results section; recommendations for future research and practice section; and conclusions section.

2. Literature Review

In this section, we define the key concepts of this study, provide a brief history pertaining to these concepts, briefly denote the relationships between them, briefly explain the existing debates, and denote what is known and not known about rural entrepreneurship and innovation.

Our study focuses on rural areas in South Africa and the need to address the economic and social ills that are prevalent in this geographical area through rural entrepreneurship and innovation. This study also emphasizes the potential to attain SDGs 1, 8, and 9 through rural entrepreneurship and innovation. The term “rural areas” springs from the term “rurality”, which was conceptualized in the 194Os to refer to rural isolated and less populated areas that are inhabited by people of certain calibers, doctrines, and practices [

23]. The definition of rurality evolved in the 1950s and 1980s [

23]. Following this understanding, we look into the key concepts of this study in the following sections.

2.1. Rural Entrepreneurship

Entrepreneurship was derived from the French word, “

entreprendre”, which is associated with taking matters into one’s hands to create something of value [

25]. The recent literature has defined entrepreneurship as the activity of constantly identifying business opportunities and turning them into business ventures [

7,

26,

27]. Constantly creating business ventures is a risky endeavor, as the return on investment is not guaranteed due to the probability of business failure [

7,

26].

Madzivhandila and Dlamini [

28] reported that people resort to entrepreneurship based on both push and pull factors. Examples of pull factors are a gap in the market, self-employment, and the opportunity to accumulate opulence, among others. Conversely, examples of push factors are poverty, unemployment, and poor living conditions, among others [

28]. Based on this broader definition of entrepreneurship, rural entrepreneurs can be conceptualized as people who perpetually start or expand businesses to address rural economic and societal problems either for profit or not for profit. This conceptualization is premised on the comprehension that people based in urban areas can also establish businesses in rural areas. A study conducted by Bolosha, Sinyolo, and Ramoroka [

16] reported that some of the firms located in the rural areas and townships of the Republic of South Africa are branches of large firms with headquarters in large cities and towns across the country. Similarly, a study conducted by Utete and Zhou [

29] revealed that urban entrepreneurs are also pulled by business opportunities available in rural areas. There are also various types of rural entrepreneurship, such as social entrepreneurship, indigenous entrepreneurship, and agricultural entrepreneurship (see [

25]). This study focused on rural entrepreneurship in a general sense.

Albeit the neoclassical growth model, which discerns labor and capital as major contributors to output, does not recognize entrepreneurship as a major contributor to economic growth, there is a plethora of scholarly works that discern entrepreneurship as a major contributor to economic growth in both developed and developing countries [

7,

30]. Moreover, entrepreneurship addresses economic and societal ills such as unemployment, poverty, and inequality, among others [

7]. It also fosters innovation, industrialization, competition, and sustainable development [

24,

26,

31]. In the rural areas’ context, rural entrepreneurship lowers the rural-urban migration that puts a strain on urban infrastructure and resources. It also minimizes income disparity and creates competitive rural development, among other effects [

29]. It is on this basis that we argue that effective entrepreneurship significantly contributes to the attainment of SDGs 1, 8, and 9.

The benefits that can be accrued from entrepreneurship necessitate entrepreneurship in rural and impoverished settings, as poverty and unemployment remain high in these areas. As argued by Wale, Chipfupa, and Hadebe [

9] and Mahadea [

14], the South African economic and societal ills of poverty and unemployment can be addressed by effectively stimulating and nurturing entrepreneurship in rural areas and the informal sector. Moreover, Asmit et al. [

26] and Utete and Zhou [

29] asserted that rural areas can play a pivotal role in the development of regional and rural economies, as they offer useful natural resources.

However, for entrepreneurship to flourish in rural areas, a conducive environment with enabling laws and support systems is of utmost importance [

22]. Matenda and Sibanda [

7] corroborated this view when they explained that the recent literature on entrepreneurship emphasizes the need for an effective entrepreneurial ecosystem (i.e., a network of stakeholders who support entrepreneurs) to create a conducive business environment.

2.2. Rural Innovation

Innovation has been widely conceived of as the launch of new or improved products, processes, marketing strategies, and business models [

16,

22,

32]. Geum and Park [

33] aver that innovation is a process with distinct but interrelated phases from invention to launch. It is argued that Joseph Schumpeter was the founder of the innovation concept, as he was the first scholar to formally define innovation in 1934. Following this, innovation was recognized as a discipline in the 1950s and has since been widely acknowledged as a catalyst that enables notable and lasting development by scholars and practitioners alike. Nonetheless, innovation is a risky endeavor, and not all innovations are successful [

21,

22].

The existing literature categorically asserts that innovation significantly contributes to ensuring a sustainable world, job creation, economic growth, and development. More innovative countries and regions tend to achieve higher rates of economic growth and development (see [

12,

18,

21,

22,

31,

32,

34,

35]).

In light of the benefits that can be accrued from innovation, it is prudent to promote its practice in rural areas as this would contribute toward the modernization of rural areas, rural development, the creation of jobs, and the alleviation of poverty. As pointed out by Habiyaremye, Kruss, and Booyens [

12], rural areas should be transformed to foster the participation of rural people in the mainstream economy and enhance the prospects of attaining the SDGs. Moreover, rural innovation can aid in enhancing access to drinking water, quality education, quality health care, sanitation, and the eradication of neglected diseases. Bhatt, Sharma, and Jain [

36] and Singh and Bhowmick [

37] explained that rural innovation entails transforming innovative ideas into novel or improved products and services that respond to social requirements and contribute to rural development. Other innovation terms are closely related to rural innovation. such as social innovation, agricultural innovation, education innovation, inclusive innovation, innovation at the base of the pyramid, holistic innovation, and frugal innovation (see [

12,

16,

25,

30,

38,

39,

40]). This study focused on rural innovation in a general sense.

Bolosha, Sinyolo, and Ramoroka [

16]) conducted an empirical study that sought to determine factors influencing innovation in SMMEs in rural areas and the informal sector of five South African Provinces, namely, Western Cape, Eastern Cape, Mpumalanga, and KwaZulu Natal. The study sampled 643 firms and revealed that 44% of these firms operate in the tertiary sector (i.e., services such as retail); 38% operate in the primary sector (i.e., farming, mining, fishing, etc.); and 18% operate in the secondary sector (i.e., agro-processing, construction, and manufacturing). Albeit these firms are innovative; they mostly engage in incremental innovation in the form of adopting technologies and new processes to enhance operations rather than radical innovation. Similarly, Ramoroka [

21] argued that rural innovation seldom springs from research and development activities, and as such it is non-technological. It rather manifests itself in changes in production processes, marketing strategies, and delivery arrangements (i.e., incremental innovation). In an antipode, an earlier study by Hart et al. [

38], which focused on social innovation in rural municipalities in South Africa, revealed that approximately 10% of the surveyed firms engaged in radical innovation. Where scholars present relatively contrary findings, future studies become imperative to clarify the differences.

In spite of the above, a study by Bolosha, Sinyolo, and Ramoroka [

16] revealed that rural innovation does contribute to job creation, economic growth, and poverty alleviation, as on average the surveyed firms employ approximately 46 workers, which is commendable. Unfortunately, 77% of the surveyed firms trade within their local municipalities, and only 3% are export-oriented. This is concerning, as export-oriented firms tend to scale up and contribute more to economic growth and job creation than non-exporting firms. The study further revealed that the majority of the firms surveyed (57%) operated for more than 10 years [

16]. This suggests that more firms exist beyond 5 years in rural areas.

Similar to entrepreneurship, for innovation to flourish, there should be a conducive environment. Investing in education, regulations, instilling a culture of R&D, and the availability of venture capitalists are fundamental contributory factors to innovation [

41]. As denoted in the following section, to some extent the South African government provides financial and non-financial support to foster entrepreneurship and innovation. Nonetheless, there is still a debate about the effectiveness of the support offered.

2.3. South African Government’s Financial and Non-Financial Support to Rural Firms

Habiyaremye, Kruss, and Booyens [

12] and Ramoroka, Soumonni, and Muchie, [

40] argued that state intervention is necessary to support rural entrepreneurs and innovators and assist them in accessing new markets, since the state has the ability to collate and reallocate resources in high volumes. Drawing insights from the experiences of China, Taiwan, and South Korea during the period when they were transforming their rural areas into competitive and industrialized areas, which lifted millions of people out of poverty, policies that enabled rural communities to harness innovation and entrepreneurship were introduced [

12].

Within the South African context, economic and social ills such as poverty, unemployment, and inequality are serious concerns for the South African government in both urban and rural areas [

42]. Thus, in an attempt to address these challenges, the South African government introduced programs and initiatives such as the GEAR, the National Empowerment Fund, and the National Informal Business Uplifting Strategy, among others [

14,

19,

28]. The aforementioned programs and initiatives are used to support firms that are based in both rural and urban-rural areas, particularly youth and women-owned firms (see [

19,

42,

43]). In the same vein, Sinyolo [

44] explained that policy documents in South Africa emphasize the need to include rural, poor, and marginalized communities as participants in the national system of innovation.

Although the impact of some of the aforementioned programs is apparent in some urban areas, these programs have not been easily accessible to rural communities, and in instances where they are provided to rural areas, their effectiveness is questionable as rural economic and societal ills remain prevalent [

45]. Similarly, Lebambo [

24] posits that due to its confined comprehension of the dynamics of rural areas, the South African government’s efforts in supporting rural firms have not been effective. Some rural firms argue that government support initiatives in rural areas have mostly benefited extended urban firms, literate, and well-established rural firms. Hart et al. [

38] argued that to ensure that rural innovation and entrepreneurship policies are effective, they should be formulated and implemented with the participation of rural communities.

3. Theoretical Framework

The existing literature is awash with theories and models that aim to explain entrepreneurship and innovation. Alluding to all these theories and models would be a daunting task. Thus, this study was conducted within the context of the agency theory and the Triple Helix Model of industrial policy.

The agency theory postulates that society is interested in creating entrepreneurs to solve social problems, innovate, and grow the economy. Accordingly, entrepreneurs act as agents that serve society in exchange for revenue and profits. For agents to prosper in solving societal problems, innovating, and growing the economy, there has to be appropriate legislation and financial and non-financial support [

46].

The Triple Helix Model of industrial policy emphasizes collaboration between government, universities, and entrepreneurs in introducing and implementing initiatives that are development-oriented [

41]. Thus, as we were conducting this study, we expected rural entrepreneurs and innovators to be involved in entrepreneurship and innovation activities to solve problems of food security, access to basic services, infrastructure, poverty, poor living conditions, and so forth in rural communities. We also expected to find existing collaboration networks between the government, knowledge institutions or universities, and entrepreneurs dedicated to tackling problems encountered by rural communities and developing rural communities. Universities are knowledge organizations that produce new and improved knowledge. The transfer of such knowledge to rural corporates can lead to the creation of new business ventures and innovations that address problems in rural areas. The government can provide a conducive environment for rural entrepreneurs and innovators to flourish.

In the following section, we explain the materials and methods adopted in this study. The PRISMA Framework was used to guide the systematic literature review process, and the relevant aspects of the PRISMA Checklist of 2020 informed the contents of the materials and methods section. Other items of the PRISMA Checklist were excluded as they are more relevant to medical studies.

4. Materials and Methods

Following insights obtained from the PRISMA framework and checklist of 2020, this study systematically reviews the literature on rural entrepreneurship and innovation in the Republic of South Africa to: understand it; discern rural entrepreneurship and innovation challenges that require policy and practice intervention; share insights; identify research gaps; and present recommendations for future research and practice. Jones, Coviello, and Tang [

47] aver that systematic literature review studies should identify all relevant studies and appraise and synthesize them in a transparent and replicable manner. Thus, it should be clearly explained how the literature was searched, how scholarly works were included or excluded and analyzed [

32,

47].

Accordingly, in this study, we systematically reviewed the literature following the steps denoted below, which are further explained:

Step 1: Identification of key terms and location of studies;

Step 2: Selection and evaluation of studies;

Step 3: Analysis and synthesis; and

Step 4: Reporting and use of research results

4.1. Step 1: Identification of Key Terms and Location of Studies

The first step of a systematic literature review process is the identification of the key terms on which the study is premised, which are used to search for relevant studies on identified research databases. Following this, a search protocol is determined [

48,

49].

In this study, based on the research topic and formulated research questions, the following key terms were used to search for journal articles, conference papers, books, theses, and dissertations on the identified research databases: rural entrepreneurship; rural innovation; BRICS economies; South Africa; and rural areas. To get more relevant search results, a combination of key terms was used to search for relevant scholarly works. For instance, phrases such as “rural entrepreneurship in South Africa” and “rural innovation in South Africa” were used. Moreover, to identify scholarly works that present findings on challenges facing rural entrepreneurship and innovation, phrases such as “rural entrepreneurship challenges” and “rural innovation challenges” were used.

Our study focused on searching for relevant scholarly works on the following academic databases: ResearchGate, Google Scholar, and ScienceDirect. These academic databases were used because they could produce relevant scholarly works when the aforementioned search terms were used. Moreover, the selected databases were easily accessible to the authors.

The search was filtered to focus on studies published between 1990 and 2024, as research on entrepreneurship and innovation in South Africa gained momentum post-1994. Nonetheless, most of the studies that met the inclusion criteria were published in the past five to ten years.

4.2. Step 2: Selection and Evaluation of Studies

According to Counsell [

50], in systematic literature review studies, the researchers must denote the criteria used to include and exclude writings as part of the review process. Thus, in the table below (

Table 1) we denote what we used as criteria for the inclusion and exclusion of scholarly works. Moreover, the titles and abstracts of identified studies were read to determine relevance and only relevant studies were included in the review.

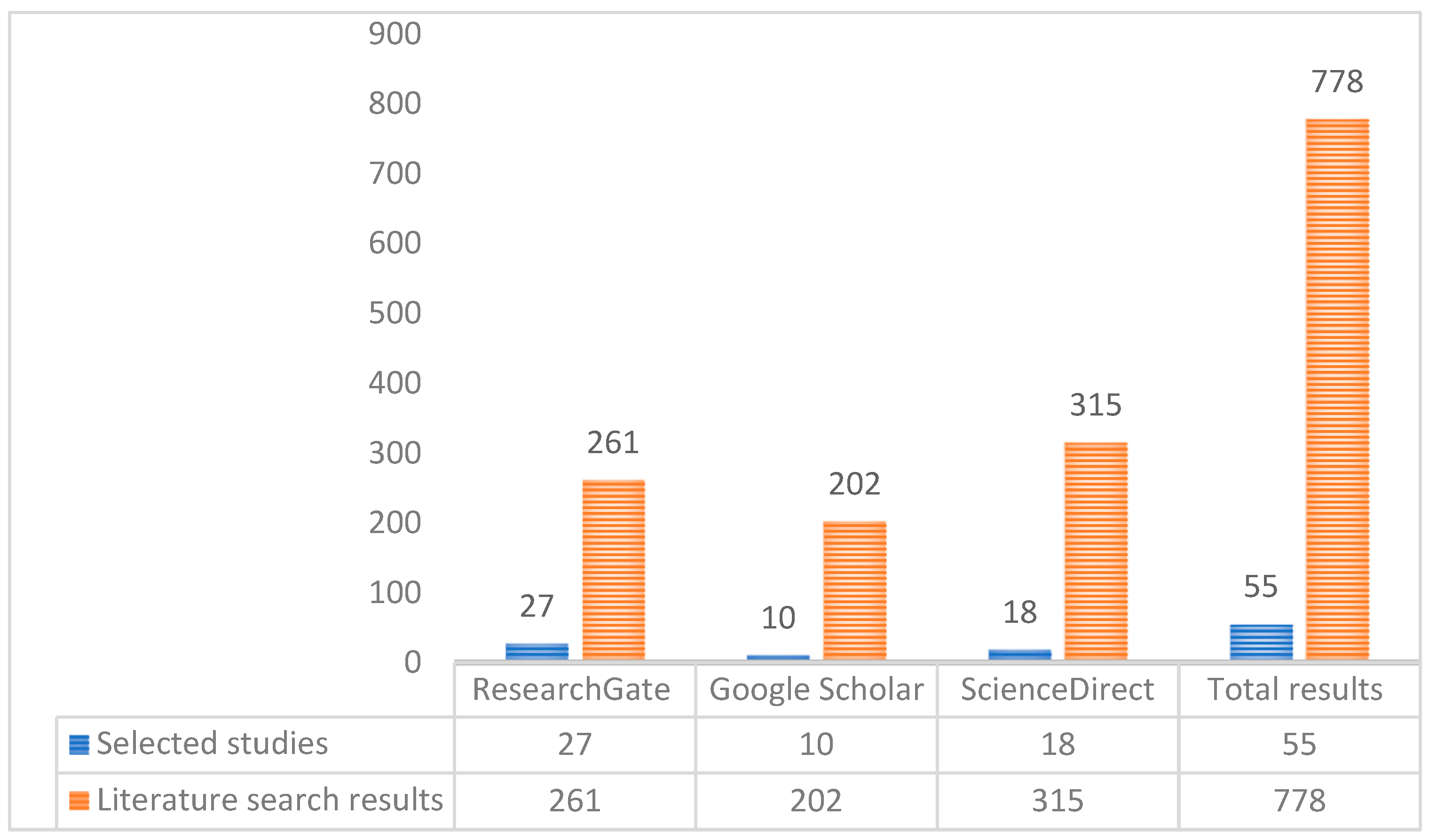

Figure 1 portrays that 778 scholarly works were found on the utilized academic databases. Of the 778 identified scholarly works, 55 were selected for the systematic literature review. The selected studies met the inclusion criteria; hence they were included in the study.

4.3. Step 3: Analysis and Synthesis

Counsell [

50] explained that analysis and synthesis involve critically examining each study, drawing relationships, and blending them to form a holistic whole. Accordingly, we qualitatively analyzed the selected scholarly works using thematic and constant comparison methods to determine themes and relationships. This involved critically reviewing each study, extracting data relevant to research questions and writing it down, and comparing the extracted data against each other to determine similarities, differences, and themes which were later documented under common conceptualized topics. What is common to the reviewed studies is that they mostly focused on identifying challenges facing rural entrepreneurship and innovation in South Africa. They also focused on identifying entrepreneurship and innovation activity and determining the role of the government and support structures such as actor networks in rural entrepreneurship and innovation.

Table 2 summarizes the themes or rather the findings emanating from the review.

4.4. Step 4: Reporting and Use of Research Results

According to Briner and Denyer [

48], in literature review studies, research findings denote what is known and not known about the systematic review questions. This study was guided by the following research questions: (1) What does the existing literature reveal about rural entrepreneurship and innovation in South Africa? (2) What are the challenges facing rural entrepreneurship and innovation in South Africa? (3) What are the insights that can be shared and what are the opportunities for future research? This study answers these questions in the findings and discussion section and the gaps and recommendations for future research section. The summary thereof is depicted in

Table 2.

The findings suggest that without addressing challenges that negatively affect rural entrepreneurship and innovation, entrepreneurship and innovation activity may not increase in rural areas, which reduces the prospects of harnessing rural entrepreneurship and innovation in transforming, industrializing, and modernizing rural areas. The findings further suggest that there are flaws in the rural areas’ policy formulation and implementation by the government and actor networks, which must be addressed to ensure that there is effective and sustainable rural entrepreneurship and innovation. Following the identification of research gaps, we also present recommendations for future research and practice in the later sections of this paper.

5. Presentation and Discussion of Results

In the preceding section, we explained the road map that was followed to conduct this secondary study. In this section, we present and discuss the results. This study was guided by the following research questions: (1) What does the existing literature reveal about rural entrepreneurship and innovation in South Africa? (2) What are the challenges facing rural entrepreneurship and innovation in South Africa? (3) What are the insights that can be shared and what are the opportunities for future research?

Table 2 summarizes the findings, references, and the identified gaps. The later subsections of this section present the findings and discussion.

5.1. The Ability of Rural Firms to Engage in Entrepreneurship and Innovation Activity Is Highly Dependent on the Availability of a Support System

Our review of the existing literature on rural entrepreneurship and innovation in South Africa revealed that rural firms depend on financial and non-financial support from the government, other firms, and other role players to engage in entrepreneurship and innovation activity. Without support from these institutions, rural firms refrain from engaging in entrepreneurship and innovation activity. As pointed out by Ramoroka, Soumonni, and Muchie [

40], rural innovations are deeply rooted in collaboration networks, and the effectiveness of such networks can lead to the success or failure of rural innovations. Similarly, Matenda and Sibanda [

7] aver that recent literature on entrepreneurship emphasizes the existence of an entrepreneurial ecosystem constituted by numerous stakeholders who provide support to entrepreneurs. In the same vein, a study conducted by Oriakhogba [

30] in rural areas of Kwazulu Natal Province of the Republic of South Africa revealed that, although crafting requires minimal human and structural capital, surveyed rural crafters mostly depended on resources offered by a non-profit organization in that area to craft and trade. In turn, this non-profit organization received funding from the government. A study conducted by Bolosha, Sinyolo, and Ramoroka [

16] in five provinces of the Republic of South Africa denoted that about 68% of the innovative rural firms surveyed obtained knowledge and information necessary to innovate from management and colleagues from urban branches or head offices of their firms. Furthermore, 29% of the innovative rural firms received support from the government departments and agencies to innovate.

While we acknowledge and support the existence of actor networks and their purpose, we argue that too much dependence on actor networks to engage in rural entrepreneurship and innovation activity is risky and diminishes the probability of rural entrepreneurship and innovation. This argument is premised on the understanding that without the purveyance of financial and non-financial support by actor networks, entrepreneurship and innovation do not take place in rural areas, which reduces the prospects of modernizing rural economies, industrializing rural areas, growing rural economies, creating jobs, alleviating poverty, and attaining SDGs 1, 8, and 9. Moreover, firm-to-firm collaboration networks are often dependent on the trust established over a certain period [

18,

40]. Thus, start-up rural firms that are new to the business environment may not benefit from firm-to-firm collaboration networks until they establish a certain type of reputation. Mulibana and Rena [

55] designed what they termed, “a Creative Innovation Framework,” which can be adopted by firms in rural areas and the informal sector to innovate without support from the government, universities, and large enterprises. The utilization of such models can reduce the dependence on actor networks for innovation and entrepreneurship purposes.

5.2. Rural Firms Are Risk-Averse, Which Challenges the Doctrine of Rural Transformation through Rural Entrepreneurship and Innovation

The review of the existing literature revealed that rural firms and people in South Africa are often reluctant to take risks to engage in entrepreneurship and innovation activity, which challenges the doctrine of creating transformed, modernized, and industrialized rural areas through entrepreneurship and innovation.

Wale, Chipfupa, and Hadebe [

9] explained that rural entrepreneurs, particularly smallholder farmers, are risk-averse. One of the contributory factors to this persona is the lack of title deeds, which impedes smallholder farmers from making long-term investments as they may be displaced by the landowners [

9]. Similarly, a study by Sinyolo [

44] observed that only 35% of the 415 surveyed rural farmers had adopted modern technologies. In the same vein, a study by Ramasimu [

39] focusing on education innovation in rural schools of the Limpopo Province revealed that although principals and teachers acknowledged the importance of education innovation in enhancing school performance, principals had to work hard to encourage teachers to take risks and adopt pedagogical related innovations. Moreover, a study conducted in rural areas of the Mpumalanga Province by Rutert and Traynor [

25] reported that due to close social relations in rural areas, participants often refrain from entrepreneurship and innovation due to fear of envy and jealousy from their fellow men and women, which may put their lives at risk.

Nonetheless, there is some evidence of entrepreneurship and innovation activity on a small scale, with male rural firm owners and workers being more entrepreneurial and innovative than their female counterparts [

9,

25,

44]. This finding suggests that males possess the “wafa-wafa” spirit, which is an African Venda language phrase often used by young Venda men when courting women who are “out of their league”. Its literal meaning is, “If I die, I die”, but its metaphorical meaning refers to instances where one braces oneself to undertake a high-risk endeavor with no fear of the possible negative outcome. Wafa-Wafa spirit is what most successful entrepreneurs and innovators have. Elon Musk once said that due to his strong desire to transport people to Mars to ensure that the human race becomes multi-planetary, he would not mind dying at Mars, either while entering or settling on it. As long as he managed to touch planet Mars, his long-term goal would have been achieved. Thus, mechanisms through which the wafa-wafa spirit can be instilled in rural firms and people to foster rural entrepreneurship and innovation should be determined.

5.3. Challenges Facing Rural Entrepreneurship and Innovation in South Africa

The review of the existing literature revealed that similar to urban areas, rural areas are not immune to challenges that impede entrepreneurship and innovation. The provision of adequate basic services to South Africans in rural areas is a persistent challenge to effective rural entrepreneurship and innovation. A study conducted by Lebambo [

24] in the rural areas of the Mpumalanga Province reported that water shortages, poor roads, and sub-standard service delivery are common challenges that rural firms in the Mpumalanga Province grapple with. In a more recent study conducted in the Limpopo Province, Pindihama and Malima [

54] explained that rural communities such as the Vhembe district barely have access to potable water. The Coronavirus pandemic exacerbated this situation as it caused interruptions in the operations of various organizations. Other common challenges facing firms in rural areas are corruption by government officials (government opportunities are not well advertised and communicated but given to friends and well-connected business associates by rural municipalities); multiple taxes; rising overhead costs on transportation and communication; late payment of rural firms; lack of appropriate business infrastructure, industry mentors, and networking opportunities; access to bank loans; and energy poverty [

15,

24,

25,

29]. Madzivhandila and Musara [

51] argued that although some rural municipalities made an effort to supply basic needs such as shelter, basic equipment, and other services to rural firms, rural firms (in particular small businesses) often struggle to pay high service fees to local municipalities to lease such facilities.

We argue that the limited to no provision of basic services such as water, electricity (in particular load shedding), and infrastructure to rural areas hinders rural entrepreneurship and innovation, thereby reducing the probability of growing the rural economy, creating jobs, addressing rural poverty and inequality, and attaining SDGs. Among the aforementioned service delivery problems, the energy crisis load shedding in particular has gained much interest in recent years. It has become a major stumbling block to entrepreneurship and innovation in all parts of South Africa. A recent study conducted by Olajuyin and Mago [

2] revealed that an unreliable energy supply negatively affects firms’ operations and increases operations costs. As such firms incur additional costs on alternative energy sources and repairs to equipment damaged by the turbulent energy supply. High operations costs often lead to business failure, which is detrimental to economic growth, job creation, and the attainment of SDGs.

Load shedding was initiated by the South African power utility Eskom in 2008 to avoid a total blackout as the electricity demand exceeds the supply. The limited supply is due to the ailing power generation infrastructure, which was burdened by the addition to the grid of millions of black South Africans who did not have access to electricity during the apartheid regime, and poor enhancements to and maintenance of the generation infrastructure over the years following the advent of a democratic regime in 1994. To mitigate the load-shedding crisis, the South African government has implemented several initiatives, such as the introduction of independent power producers, the splitting of Eskom into several divisions, the use of renewable energy, and so forth, but this has not translated into energy security for the country [

2]. Thus, effective mechanisms through which South Africa can achieve energy security for its citizens in both rural and urban areas have yet to be explored. Notwithstanding the above, it is interesting to note that a recent study conducted in five provinces of the Republic of South Africa by Bolosha, Sinyolo, and Ramoroka [

16] reported that, astonishingly, 80% of the respondents indicated that they had access to reliable energy. This suggests that power cuts and load shedding are not as frequent in rural areas as they are in urban areas, which favors entrepreneurship and innovation.

Concerning innovation, Ramoroka [

21] explained that rural communities seldom invest in R&D, which limits their probability of engaging in innovative activity. This can be attributed to their lack of innovation-fostering factors such as human and structural capital, a conducive environment, and the availability of financial resources. Moreover, Bolosha, Sinyolo, and Ramoroka [

16] aver that innovation-related challenges that face rural firms include a lack of innovation-related infrastructure such as ICT infrastructure, libraries, and laboratories, difficulty in dealing with government regulations, and limited human and structural capital. Rural firms are mostly located in impoverished settings. Subsequently, they often fail to attract highly skilled employees with high human capital and structural capital investments [

19,

53].

Rural entrepreneurship and innovation may not flourish amid the aforementioned challenges. As pointed out by Matenda and Sibanda [

7] and Habiyaremye, Kruss, and Booyens [

12], for rural entrepreneurship and innovation to flourish, there has to be a conducive environment with a supportive legislative framework and systems. Thus, if the South African government is serious about transforming and modernizing rural areas through rural entrepreneurship and innovation, addressing the aforementioned challenges should be among its top priorities.

5.4. Innovation Has Traditionally Been Perceived as an Endeavor Suitable for Urban Areas

Innovation has mostly been perceived as an endeavor that is suitable for densely populated areas, particularly urban areas. Rural areas have not traditionally been considered viable spaces for entrepreneurship and innovation due to their rurality [

12,

16,

19]. Ramoroka [

21] corroborated this view by explaining that studies on innovation activity often focus on urban areas and R&D-based innovations rather than rural areas.

Nonetheless, contemporary studies reveal that innovation occurs in rural and impoverished areas as well, with some scholars and practitioners arguing that rural innovation has always been there and it is not something that came into existence in recent years [

12,

21,

25]. We argue that rural areas have always been a home for entrepreneurship and innovation. Oral history posits that our forefathers were involved in entrepreneurship and innovation activities on a small scale by using readily available local resources to create new or improved products, services, processes, and so forth to respond to the household’s social and economic ills. The problem has been that these activities were not properly documented.

5.5. Rural Entrepreneurs and Innovators Are Often Excluded from Policy Making and Implementation

Firms in rural areas are often excluded during policymaking and implementation due to a lack of information and not knowing who to contact for information [

25,

38,

42]. This postulates that rural firms have been silent intended beneficiaries rather than active participants in many government policies, programs, and initiatives intended to support rural firms. Rural firms can thus be regarded as the “overlooked others”, and this can be considered the major cause of the persistent challenges that rural firms encounter. These challenges pose a risk to their existence, sustainability, and growth.

Farisani [

42] corroborated the aforementioned assertion by pointing out that institutions responsible for supporting rural firms do not have offices in rural areas, and when they do, they are not positioned in an area that is easily accessible from every corner of the rural area. Moreover, such institutions do not collaborate with rural organizations, such as the local business community, non-governmental organizations, and traditional leaders, when formulating and implementing policies and initiatives in rural areas.

We argue that this finding is the major contributory factor to the persistent economic and social ills in rural areas. It is counterproductive to formulate and implement policies without involving the beneficiaries of such policies. To some extent, different regions have unique challenges, and a solution that has worked elsewhere may not work in a certain region. As posited by Habiyaremye, Kruss, and Booyens [

12], to ensure effective policy formulation and implementation in rural areas, rural people should be active participants.

5.6. Firms That Receive Financial and Non-Financial Support Tend to Fail after the Phasing out of Business Support

Rungani and Klaas [

52] argued that small businesses continue to fail despite receiving support from both the public and private sectors, particularly after financial and non-financial support has been phased out. Similarly, Enaifoghe and Vezi-Magigaba [

19] posited that despite the public and private sector efforts in supporting small businesses, the sustainability of small businesses in both rural and urban areas remains a challenge.

Small business failures impede and to some extent rescind efforts to grow the economy, create jobs, and alleviate poverty in rural areas. Thus, this problem requires urgent attention. Surely there are flaws in the manner in which small businesses are being supported, which creates some form of dependence. That is why such businesses fail when such support is phased out. Moreover, when rural firms are not sustainable, do not grow, and fail, the potential to attain SDGs 1, 8, and 9 diminishes.

6. Recommendations for Future Research and Practice

This study revealed that rural firms that receive financial and non-financial support tend to fail after the phasing out of business support, which diminishes the potential to attain SDGs 1, 8, and 9. Future studies should determine the causes of this and propose feasible solutions.

Moreover, rural entrepreneurs and innovators are often excluded from policy making and implementation. Thus, future studies should determine and recommend feasible, inclusive rural policy formulation and implementation strategies.

There is a plethora of rural entrepreneurship and innovation challenges. Subsequently, rural firms and people are risk-averse. Thus, future studies should focus on determining solutions to the identified challenges and mechanisms through which the wafa-wafa spirit can be instilled in rural firms and people.

This study further revealed that there are innovations that occur in rural areas. In view of the South African energy crisis, which led to practices such as the load shedding that was initiated in 2008 and has gradually become more frequent in recent years, future studies should focus on ascertaining whether there are rural innovations in the energy generation space, and if such innovations exist, which of them can be targeted for government support and enhancement in an attempt to solve the South African energy crisis.

Collaboration between universities, government, and corporations, in particular, SMMEs is critical for meaningful and impactful entrepreneurial and innovation activity to occur in rural areas. Thus, future studies should determine what can be done to enhance collaboration between the various role players in rural areas.

Our study further revealed that actor networks such as innovation hubs and incubation centers are imperative in stimulating and nurturing entrepreneurship and innovation. Thus, it is recommended that the South African government establish several innovation hubs, clusters, and incubation centers in rural areas to stimulate and nurture rural entrepreneurship and innovation.

7. Conclusions

Following a systematic literature review approach, this study established an understanding of rural entrepreneurship and innovation in the Republic of South Africa. It revealed rural entrepreneurship and innovation challenges that require policy and practical intervention, shared some insights, highlighted research gaps, and presented recommendations for future research and practice. This study further revealed that rural firms and people are risk-averse, often due to challenges that are prevalent in their micro, market, and macro environment. This challenges the doctrine of rural transformation through rural entrepreneurship and innovation. Moreover, the ability of rural firms to engage in entrepreneurship and innovation is highly dependent on the availability of support from the government and actor networks. Subsequently, rural firms fail when support is phased out. The findings of this study resonate with the agency theory and the Triple Helix Model of industrial policy as it is apparent from the secondary evidence presented that rural firms are engaging in entrepreneurship and innovation to address economic and social problems that are prevalent in rural areas, including the need to end hunger, poverty, and inequality, through agricultural and other forms of innovation. It is further apparent that rural firms also require financial and non-financial support from the government and actor networks to engage in entrepreneurship and innovation.

The findings suggest that without addressing challenges that negatively affect rural entrepreneurship and innovation, entrepreneurship and innovation activity may not increase in rural areas, which reduces the prospects of harnessing rural entrepreneurship and innovation in transforming, industrializing, and modernizing rural areas. Moreover, the findings suggest that there are flaws in the rural areas policy formulation and implementation by the government and actor networks. These flaws must be addressed to ensure that there is effective and sustainable rural entrepreneurship and innovation.

In spite of the above interpretation, rural areas present a promising viable business environment, as there are abundant natural resources (including unused land), less energy poverty, less nefarious activities, less labor unrest, less social unrest, and cheap labor. Thus, there can be successful entrepreneurship and innovation in rural areas of South Africa. Effective rural entrepreneurship and innovation have a great potential to transform rural areas. Industrializing and modernizing them which could translate into an adequate economic growth rate, job creation, poverty alleviation, equality, and the attainment of SDGs 1,8, and 9. The existence of successful entrepreneurs and innovators in rural areas could also increase the government’s rural tax base, and the government could use the taxes to enhance rural infrastructure and other basic services such as proper access roads, the water and energy supply infrastructures.

The South African government and actor networks can further aid in nurturing successful rural entrepreneurship and innovation by addressing the challenges facing rural entrepreneurship and innovation presented in this paper. As they do so, they should teach rural firms and people to be independent and sustainable entrepreneurs and innovators.