Decision Change: The First Step to System Change

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Problems

2.1. COPs and Crises

2.2. Decision-Making by the United Nations

2.3. Systems Approach

2.4. Global Governance

2.5. Alternative Global Governance

3. Meta-Decision Structures

4. Decision-Making Experts

| Concise Descriptions of Some Important Fields of Decision-Making Theory |

|---|

| Social-choice theory is concerned with the aggregation of judgements or preferences, such as through various voting procedures [89,90,91]. To illustrate, an impossibility theorem states, loosely speaking, that no procedure for collective decision-making can recognise ‘objective basic needs or universal criteria’ [92]. |

| Public-choice theory considers decision-makers to be self-interested agents, as in an economy [93]. |

| Multiple-attribute group decision-making [94]. |

| Global governance [95], defined as repeated decision-making. |

| Decision-making based on wisdom, knowledge and reason. For governance, this is known as noöcracy [96], epistocracy [97,98], or epistemic democracy [99], and more generally, as collective reasoning [100]. |

| Negotiation [101] and the theory of mathematical games, including mechanism design [102]. |

| Deliberation, such as in citizens’ assemblies, comprising randomly selected citizens who inform themselves and decide collectively, often subject to group dynamics [103,104]. |

| Representation and delegation [105,106]. |

| Argumentation theory, that is, logic, rhetoric, and public discourse [107,108]. |

| Analytical methods, such as cost-benefit analysis [109]. |

| Individual decision-making and its fallacies [110]. |

5. Design of a Decision-Making Procedure

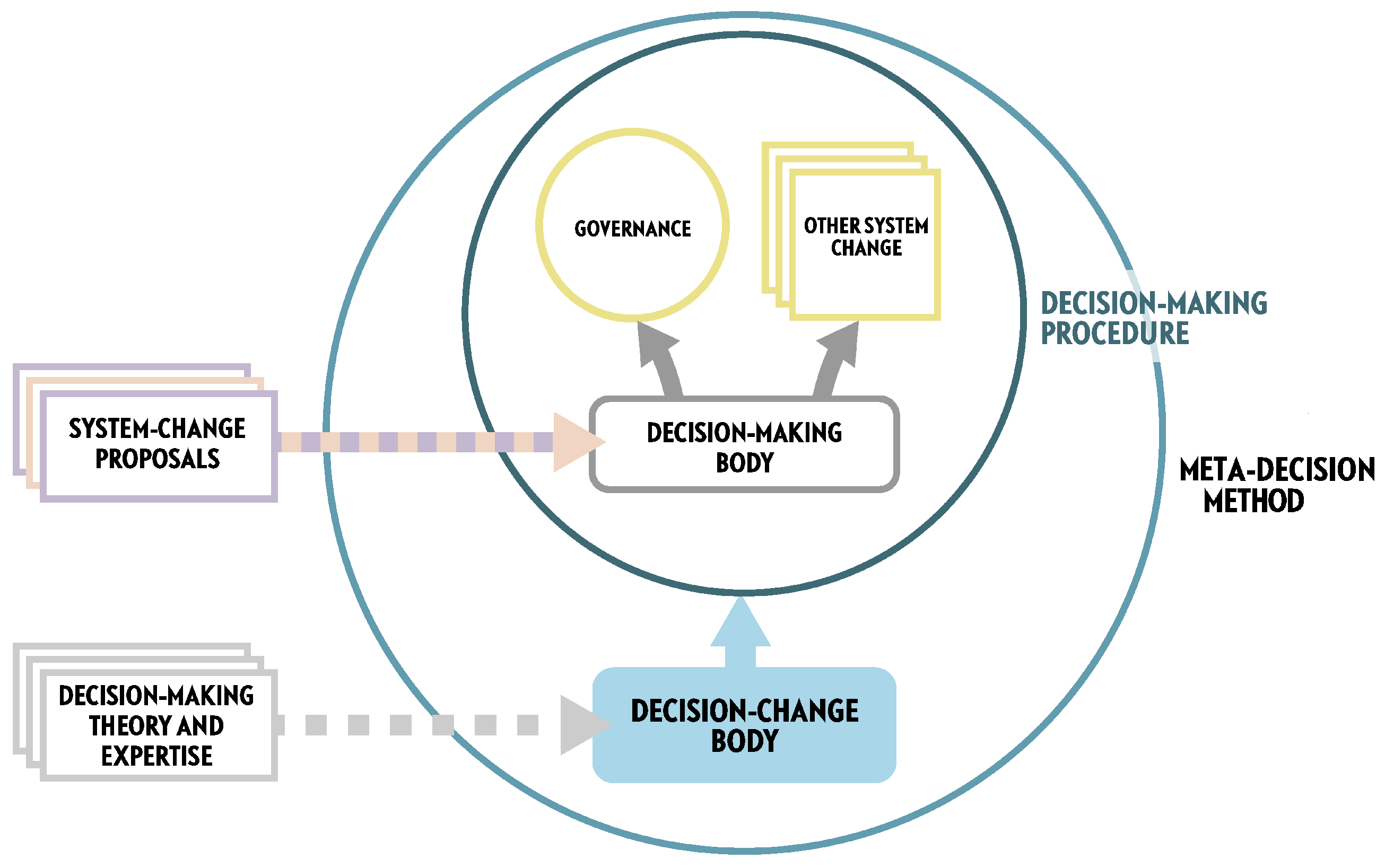

- Design: Independent experts in collective decision-making design a one-time decision-making procedure (medium-sized circle), while being monitored by auxiliary bodies (suggestions in Appendix A.2). The decision-making experts and auxiliary bodies are collectively called the decision-change body (lower box). Designing a decision-making procedure basically is a process of deciding how to decide, which follows a meta-decision method (larger circle and the upward arrow protruding from the lower box). This method is also to be selected by the experts, who already possess the required expertise and theoretical understanding, such as social-choice theory (lower dashed arrow). Suggestions for the meta-decision method are in Appendix A.1.

- Collection of system-change proposals: If unprepared, the decision-making body would possess only a limited array of system-change proposals and be faced with the daunting task of inventing additional proposals from the start. Therefore, proposals would have to be collected in advance to provide a head start, after which more proposals can be added (upper dashed arrow). Although this step should actually be designed by the decision-making experts, it has been inserted to show the experts that proposals will be available to decide upon.

- Decision: The decision-making body (upper box) employs the decision-making procedure designed by the decision-change body. Using system-change proposals (upper dashed arrow), the decision-making body decides on issues such as an economy based on wellbeing indicators (‘other system change’) as well as governance (that is, repeated decision-making), which may differ from the decision-making procedure used for its selection.

6. Coordination

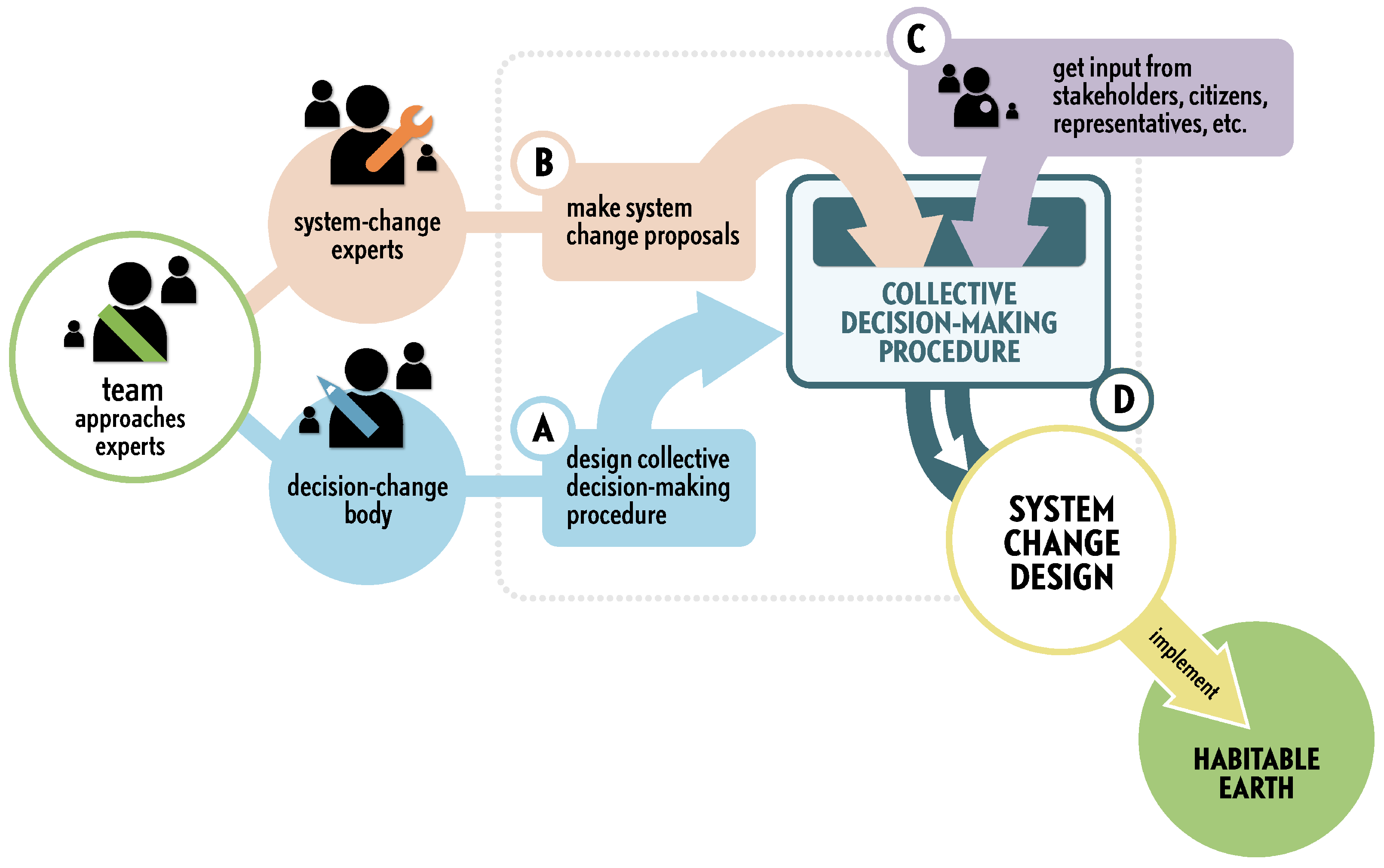

- A

- Compose the decision-change body (at the left of the rectangle); that is, convene independent experts in collective decision-making and assemble the auxiliary bodies. For details about independency, see Appendix A.2, second point. The decision-change body designs a procedure (box with a slit) to collectively decide on system change.

- B

- Collect initial system-change proposals from experts in relevant subject areas, not only as a head start, but also to convince decision-making experts to participate by making it plausible that their decision-making procedure will be implemented.

- C

- Collect proposals and other input from the public. (At least, this is our suggestion: Appendix A.3, paragraph about content.) Box C represents the inputs from both the decision-making body and other parties.

- D

- The decision-making body should combine the proposals and other input according to the selected decision-making procedure. The team only needs to initiate this final stage, that is, ensure that it is organised.

7. Discussion

7.1. Potential Advantages of the Programme

7.2. Potential Limitations of the Programme

7.3. Implementation Prospects

8. Conclusions and Call to Action

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| COP | Conference of the Parties |

| GHG | Greenhouse Gas |

| IPCC | Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change |

| NDC | Nationally Determined Contribution |

| UN | United Nations |

| UNFCCC | UN Framework Convention on Climate Change |

Appendix A. Potential Pathways

Appendix A.1. The Meta-Decision Method

Appendix A.2. Safeguarding the Design Process

Appendix A.3. Decision-Making Procedures

Appendix A.4. System-Change Design

Appendix B. Details

Appendix B.1. The Scenario Model Intercomparison Project

Appendix B.2. The Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change

Appendix B.3. The World Meteorological Organization

Appendix B.4. The United Nations Environment Programme and Others

Appendix B.5. The Global Stocktake

Appendix B.6. Betting against a one-third Chance of Failure

Appendix B.7. System Change

Appendix B.8. International Non-Governmental Organisations

Appendix B.9. The Meta-Coordination Problem

Appendix B.10. Orlove’s Classification

Appendix B.11. Informational Anti-Environmentalist Methods

References

- Climate Carnage: Whose Job Is it to Save the Planet? The Guardian. 2022. at 10:52. Available online: https://www.theguardian.com/environment/video/2022/nov/10/climate-carnage-whose-job-is-it-to-save-the-planet-documentary (accessed on 2 February 2024).

- Rosane, O. “These Processes Are Failing”: Greta Thunberg Calls Out World Leaders as Bonn Talks Founder. Common Dreams. 14 June 2023. Available online: https://www.commondreams.org/news/thunberg-calls-out-world-leaders-at-bonn (accessed on 2 February 2024).

- Maslin, M.; Parikh, P.; Taylor, R.; Chin-Yee, S. COP27 Will Be Remembered as a Failure: Here’s what Went Wrong. The Conversation. 22 November 2022. Available online: https://phys.org/news/2022-11-opinion-cop27-failurehere-wrong.html (accessed on 2 February 2024).

- McGuire, W. The Big Takeaway from Cop27? These Climate Conferences just Aren’t Working. The Guardian. 22 November 2022. Available online: https://www.theguardian.com/commentisfree/2022/nov/20/big-takeaway-cop27-climate-conferences-arent-working (accessed on 2 February 2024).

- Scrutton, A. After a Mediocre Deal, COP27 Needs a Dose of Democracy. Democracy Notes. 22 November 2022. Available online: https://www.idea.int/blog/after-mediocre-deal-cop27-needs-dose-democracy (accessed on 2 February 2024).

- Slavin, T. After “Disappointing” COP27, Calls Grow for New Approach to Fighting Climate Change. Reuters. 28 November 2022. Available online: https://www.reuters.com/business/sustainable-business/after-disappointing-cop27-calls-grow-new-approach-fighting-climate-change-2022-11-28/ (accessed on 2 February 2024).

- Democracy in Europe Movement 2025. COP off! DiEM25’s Alternative Climate Conference to COP27. DiEM Communications. 14 November 2022. Available online: https://diem25.org/cop-off-diem25s-alternative-climate-conference-cop27/ (accessed on 2 February 2024).

- Dixson-Declève, S. End the Circus of COP27 Once and for All. Club of Rome. 22 November 2022. Available online: https://www.clubofrome.org/blog-post/decleve-cop27/ (accessed on 2 February 2024).

- Nordborg, H. COP is a Planned Failure: Why Having a Bad Plan Is Worse than Not Having a Plan. Global Climate Compensation. 23 November 2022. Available online: https://www.global-climate-compensation.org/p/cop-is-a-planned-failure (accessed on 2 February 2024).

- Unitarian Universalist Service Committee. COP27: Radical Alternatives Needed. 15 November 2022. Available online: https://www.uusc.org/cop27-radical-alternatives-needed/ (accessed on 2 February 2024).

- Rockström, J.; Dixson-Declève, S.; Robinson, M.; Ki-moon, B.; Tubiana, L.; Huq, S.; Nobre, C.; Ghosh, A.; Burrow, S.; Patel, S.; et al. Reform of the COP Process. A Manifesto for Moving from Negotiations to Delivery. Club of Rome. 23 February 2023. Available online: https://www.clubofrome.org/cop-reform/ (accessed on 2 February 2024).

- Brandt, U.; Svendsen, G.T. Is the annual UNFCCC COP the only game in town? Unilateral action for technology diffusion and climate partnerships. Technol. Forecast. Soc. Change 2022, 183, 121904:1–121904:9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sommerer, T.; Agné, H.; Zelli, F.; Bes, B. The Legitimacy Crises of the WTO and the UNFCCC. In Global Legitimacy Crises: Decline and Revival in Multilateral Governance; Sommerer, T., Agné, H., Zelli, F., Bes, B., Eds.; Oxford University Press: Oxford, UK, 2022; pp. 79–102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Benedick, R.E. Avoiding Gridlock on Climate Change. Issues Sci. Technol. 2007, 23, 37–40. Available online: https://jstor.org/stable/43314398 (accessed on 2 February 2024).

- Hermwille, L.; Obergassel, W.; Ott, H.E.; Beuermann, C. UNFCCC before and after Paris: What’s necessary for an effective climate regime? Clim. Policy 2017, 17, 150–170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hjerpe, M.; Nasiritousi, N. Views on alternative forums for effectively tackling climate change. Nat. Clim. Change 2015, 5, 864–867. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Widerberg, O.; Pattberg, P. International Cooperative Initiatives in Global Climate Governance: Raising the Ambition Level or Delegitimizing the UNFCCC? Glob. Policy 2015, 6, 45–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dixson-Declève, S. COP28 Did Not Deliver; We Need Better Global Governance and Brave Leadership. Club of Rome. 15 December 2023. Available online: https://www.clubofrome.org/blog-post/decleve-post-cop28/ (accessed on 2 February 2024).

- Monbiot, G. Cop28 Is a Farce Rigged to Fail, but There Are Other Ways We Can Try to Save the Planet. The Guardian. 9 December 2023. Available online: https://www.theguardian.com/commentisfree/2023/dec/09/cop28-rigged-fail-save-planet-climate-summit-fossil-fuel (accessed on 2 February 2024).

- Neslen, A. We Need Power to Prescribe Climate Policy, IPCC Scientists Say. The Guardian. 7 December 2023. Available online: https://www.theguardian.com/environment/2023/dec/07/we-need-power-to-prescribe-climate-policy-ipcc-scientists-say (accessed on 2 February 2024).

- United Nations. Paris Agreement. 2015. Available online: https://unfccc.int/sites/default/files/english_paris_agreement.pdf (accessed on 2 February 2024).

- Iyer, G.; Cui, R.; Edmonds, J.; Fawcett, A.; Hultman, N.; McJeon, H.; Ou, Y. Taking stock of nationally determined contributions: Continued ratcheting of ambition is critical to limit global warming to 1.5 °C. One Earth 2023, 6, 1089–1092. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adger, W.N. Loss and Damage from climate change: Legacies from Glasgow and Sharm el-Sheikh. Scott. Geogr. J. 2023, 139, 142–149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tramel, S. The Road Through Paris: Climate Change, Carbon, and the Political Dynamics of Convergence. Globalizations 2016, 13, 960–969. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Streck, C.; von Unger, M.; Krämer, N. From Paris to Katowice: Cop-24 Tackles the Paris Rulebook. J. Eur. Environ. Plan. Law 2019, 16, 165–190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sinkovics, N.; Vieira, L.M.; van Tulder, R. Working toward the sustainable development goals in earnest—Critical international business perspectives on designing and implementing better interventions. Crit. Perspect. Int. Bus. 2022, 18, 445–456. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tebaldi, C.; Debeire, K.; Eyring, V.; Fischer, E.; Fyfe, J.; Friedlingstein, P.; Knutti, R.; Lowe, J.; O’Neill, B.; Sanderson, B.; et al. Climate model projections from the Scenario Model Intercomparison Project (ScenarioMIP) of CMIP6. Earth Syst. Dyn. 2021, 12, 253–293. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change. Views on the Elements for the Consideration of Outputs Component of the First Global Stocktake: Synthesis Report by the Secretariat. Items I.A.2 and I.A.3.b. 4 October 2023. Available online: https://unfccc.int/sites/default/files/resource/SYR_Views%20on%20%20Elements%20for%20CoO.pdf (accessed on 2 February 2024).

- Breeze, N. COPOUT. How Governments Have Failed the People on Climate—An Insider’s View of Climate Change Conferences, from Paris to Dubai; Ad Lib: Woodbridge, UK, 2024; pp. 57, 257. [Google Scholar]

- Ramanathan, V.; Feng, Y. On avoiding dangerous anthropogenic interference with the climate system: Formidable challenges ahead. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2008, 105, 14245–14250. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ripple, W.J.; Wolf, C.; Gregg, J.W.; Rockström, J.; Newsome, T.M.; Law, B.E.; Marques, L.; Lenton, T.M.; Xu, C.; Huq, S.; et al. The 2023 state of the climate report: Entering uncharted territory. BioScience 2023, 73, 841–850. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spash, C. This changes nothing: The Paris Agreement to ignore reality. Globalizations 2016, 13, 928–933. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Díaz, S.; Settele, J.; Brondízio, E.S.; Ngo, H.T.; Guèze, M.; Agard, J.; Arneth, A.; Balvanera, P.; Brauman, K.A.; Butchart, S.H.M.; et al. (Eds.) Summary for Policymakers of the Global Assessment Report on Biodiversity and Ecosystem Services of the Intergovernmental Science-Policy Platform on Biodiversity and Ecosystem Services; IPBES Secretariat: Bonn, Germany, 2019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chapin, F.S.; Zavaleta, E.S.; Eviner, V.T.; Naylor, R.L.; Vitousek, P.M.; Reynolds, H.L.; Hooper, D.U.; Lavorel, S.; Sala, O.E.; Hobbie, S.E.; et al. Consequences of changing biodiversity. Nature 2000, 405, 234–242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Managi, S.; Islam, M.; Saito, O.; Stenseke, M.; Dziba, L.; Lavorel, S.; Pascual, U.; Hashimoto, S. Valuation of nature and nature’s contributions to people. Sustain. Sci. 2022, 17, 701–705. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Piccolo, J.J.; Taylor, B.; Washington, H.; Kopnina, H.; Gray, J.; Alberro, H.; Orlikowska, E. “Nature’s contributions to people” and peoples’ moral obligations to nature. Biol. Conserv. 2022, 270, 109572:1–109572:8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anderson, V.; Read, R. Biodiversity: Targets and Lies. Resilience. 20 December 2022. Available online: https://www.resilience.org/stories/2022-12-20/biodiversity-targets-and-lies/ (accessed on 2 February 2024).

- United Nations. In Proceedings of the Conference of the Parties to the Convention on Biological Diversity: Kunming-Montreal Global Biodiversity Framework, Decision 15/4. 19 December 2022. Targets 16 and 18. Available online: https://www.cbd.int/doc/decisions/cop-15/cop-15-dec-04-en.pdf (accessed on 2 February 2024).

- Büscher, B.; Duffy, R. Biodiversity Treaty: UN Deal Fails to Address Root Causes of Nature’s Destruction. The Conversation. 12 December 2022. Available online: https://theconversation.com/biodiversity-treaty-un-deal-fails-to-address-the-root-causes-of-natures-destruction-196905 (accessed on 2 February 2024).

- United Nations. Our Common Agenda: Report of the Secretary-General. 2021. Item 62. p. 48. Available online: https://www.un.org/en/content/common-agenda-report/assets/pdf/Common_Agenda_Report_English.pdf (accessed on 2 February 2024).

- High-Level Advisory Board on Effective Multilateralism. A Breakthrough for People and Planet: Effective and Inclusive Global Governance for Today and the Future; United Nations University: New York, NY, USA, 2023; pp. 13, 24. Available online: https://highleveladvisoryboard.org/breakthrough/pdf/56892_UNU_HLAB_report_Final_LOWRES.pdf (accessed on 2 February 2024).

- Rietig, K.; Peringer, C.; Theys, S.; Censoro, J. Unanimity or standing aside? Reinterpreting consensus in United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change negotiations. Int. Environ. Agreements 2023, 23, 221–234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rached, D.H. The Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change: Holding Science and Policy-Making to Account. Yearb. Int. Environ. Law 2014, 24, 3–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spratt, D.; Armistead, A. COVID-19 Climate Lessons: Unprepared for a Pandemic, Can the World Learn How to Manage the Bigger Threat of Climate Disruption? National Centre for Climate Restoration (Breakthrough). 2020. Available online: https://www.breakthroughonline.org.au/papers (accessed on 2 February 2024).

- May, C. Who’s in charge? Corporations as institutions of global governance. Palgrave Commun. 2015, 1, 15042:1–15042:10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- McSweeney, R. Analysis: Which Countries Have Sent the Most Delegates to COP28? Carbon Brief. 1 December 2023. Available online: https://www.carbonbrief.org/analysis-which-countries-have-sent-the-most-delegates-to-cop28/ (accessed on 2 February 2024).

- Kick Big Polluters Out. Record Number of Fossil Fuel Lobbyists at COP28. 5 December 2023. Available online: https://kickbigpollutersout.org/articles/release-record-number-fossil-fuel-lobbyists-attend-cop28 (accessed on 2 February 2024).

- Watts, J. One in Four Billionaire Cop28 Delegates Made Fortunes from Polluting Industries. The Guardian. 12 December 2023. Available online: https://www.theguardian.com/environment/2023/dec/12/one-in-four-billionaire-cop28-delegates-made-fortunes-from-polluting-industries (accessed on 2 February 2024).

- Abu Dhabi National Oil Company Strategy. Available online: https://adnocdrilling.ae/en/innovation-and-growth/strategy (accessed on 2 June 2023).

- Zapf, M. Averting Climate Catastrophe Together: Framework for Sustainable Development with a Cooperative and Systemic Approach; Walter de Gruyter: Berlin, Germany, 2022; pp. 3, 159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bucelli, I.; McKnight, A. Mapping Systemic Approaches to Understanding Inequality and Their Potential for Designing and Implementing Interventions to Reduce Inequality; Working Paper 62; International Inequalities Institute: London, UK, 2021; Available online: https://www.bosch-stiftung.de/sites/default/files/publications/pdf/2021-05/LSE_working_paper_inequality.pdf (accessed on 2 February 2024).

- Budjeryn, M. Distressing a System in Distress: Global Nuclear Order and Russia’s War against Ukraine. Bull. At. Sci. 2022, 78, 339–346. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmed, N.M. Failing States, Collapsing Systems. Biophysical Triggers of Political Violence; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2017; pp. 87, 92, 94. Available online: https://academia.edu/34816514/Failing_States_Collapsing_Systems_BioPhysical_Triggers_of_Politica_Violence_SPRINGER_BRIEFS_IN_ENERGY_ (accessed on 2 February 2024).

- Bolton, M. A system leverage points approach to governance for sustainable development. Sustain. Sci. 2022, 17, 2427–2457. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goldsmith, E.; Allen, R.; Allaby, M.; Davoll, J.; Lawrence, S. A Blueprint for Survival; Penguin: Harmondsworth, UK, 1977. [Google Scholar]

- Heilbroner, R.L. Ecological Armageddon. In Between Capitalism and Socialism; Vintage Books: New York, NY, USA, 1970; pp. 269–283. [Google Scholar]

- Meadows, D.L. (Ed.) The Limits to Growth: A Report for the Club of Rome Project on the Predicament of Mankind; Universe Books: New York, NY, USA, 1972; Available online: https://www.donellameadows.org/wp-content/userfiles/Limits-to-Growth-digital-scan-version.pdf (accessed on 2 February 2024).

- d’Orville, H. The Relationship between Sustainability and Creativity. Cadmus 2019, 4, 65–73. Available online: https://cadmusjournal.org/article/volume-4/issue-1/relationship-between-sustainability-and-creativity (accessed on 2 February 2024).

- Commission on Global Governance. Our Global Neighborhood; Oxford University Press: Oxford, UK, 1995; Available online: https://academic.oup.com/book/53430 (accessed on 2 February 2024).

- Keping, Y. Governance and Good Governance: A New Framework for Political Analysis. Fudan J. Hum. Soc. Sci. 2018, 11, 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weiss, T.G.; Wilkinson, R. Rethinking Global Governance? Complexity, Authority, Power, Change. Int. Stud. Q. 2014, 58, 207–215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, Y.; Tan, X.; Shi, Y.; Deng, J. What are the core concerns of policy analysis? A multidisciplinary investigation based on in-depth bibliometric analysis. Humanit. Soc. Sci. Commun. 2023, 10, 190:1–190:12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lopez-Claros, A.; Dahl, A.L.; Groff, M. Global Governance and the Emergence of Global Institutions for the 21st Century; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 2020; pp. 13, 14, 64, 488. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Frey, U.J.; Burgess, J. Why do climate change negotiations stall? Scientific evidence and solutions for some structural problems. Glob. Discourse 2023, 13, 138–162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Biermann, F.; van Driel, M.; Vijge, M.J.; Peek, T. Governance Fragmentation. In Architectures of Earth System Governance: Institutional Complexity and Structural Transformation; Biermann, F., Kim, R.E., Eds.; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 2020; pp. 165–168, glossary p. 322. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hale, T.; Held, D. Gridlock and Innovation in Global Governance: The Partial Transnational Solution. Glob. Policy 2012, 3, 169–181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Biermann, F.; Pattberg, P.; van Asselt, H.; Zelli, F. The Fragmentation of Global Governance Architectures: A Framework for Analysis. Glob. Environ. Politics 2009, 9, 14–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Micklethwait, J.; Wooldridge, A. The Fourth Revolution: Reinventing the State and Democracy for the 21st Century. New Perspect. Q. 2014, 31, 24–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Friedman, J. Beyond cues and politicial elites: The forgotten Zaller. Crit. Rev. 2012, 24, 417–461. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hale, T.; Held, D. Breaking the Cycle of Gridlock. Glob. Policy 2018, 9, 129–137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marx, A.; Wouters, J. (Eds.) Global Governance; Elgaronline: Cheltenham, UK, 2018. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bedsted, B.; Mathieu, Y.; Leyrit, C. (Eds.) World Wide Views on Climate and Energy from the World’s Citizens to the Climate and Energy Policymakers and Stakeholders; Danish Board of Technology Foundation; Missions Publiques, and the French National Commission for Public Debate: Copenhagen, Denmark, 2015; Available online: https://climateandenergy.wwviews.org/wp-content/uploads/2015/09/WWviews-Result-Report_english_low.pdf (accessed on 2 February 2024).

- Curato, N.; Chalaye, P.; Conway-Lamb, W.; De Pryck, K.; Elstub, S.; Morán, A.; Oppold, D.; Romero, J.; Ross, M.; Sanchez, E.; et al. Global Assembly on the Climate and Ecological Crisis: Evaluation Report; Center for Deliberative Democracy on Global Governance; University of Canberra: Canberra, Australia, 2023; Available online: https://researchprofiles.canberra.edu.au/en/publications/global-assembly-on-the-climate-and-ecological-crisis-evaluation-r (accessed on 2 February 2024).

- Deese, R.S. Climate Change and the Future of Democracy; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Crowley, K.; Head, B.W. The enduring challenge of ‘wicked problems’: Revisiting Rittel and Webber. Policy Sci. 2017, 50, 539–547. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Biermann, F.; Abbott, K.; Andresen, S.; Bäckstrand, K.; Bernstein, S.; Betsill, M.M.; Bulkeley, H.; Cashore, B.; Clapp, J.; Folke, C.; et al. Navigating the Anthropocene: Improving Earth System Governance. Science 2012, 335, 1306–1307. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Browne, S. UN Reform. 75 Years of Challenge and Change; Edward Elgar: Northampton, MA, USA, 2019; p. 204. [Google Scholar]

- Orlove, B.; Shwom, R.; Markowitz, E.; Cheong, S.-M. Climate decision-making. Annu. Rev. Environ. Resour. 2020, 45, 271–303. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Earth System Governance. Radboud Conference on Earth System Governance. Bridging Sciences and Societies for Sustainable Transformations. 2023. Available online: https://www.earthsystemgovernance.org/2023radboud/ (accessed on 2 February 2024).

- Global Challenges Foundation. Joint Campaign to Strengthen International Cooperation Launches Call for Ideas. 26 July 2019. Available online: https://web.archive.org/web/20230327192831/https://globalchallenges.org/joint-campaign-to-strengthen-international-cooperation-launches-call-for-ideas/ (accessed on 2 February 2024).

- Global Challenges Foundation. New Shape Prize Library. 2018. Available online: https://globalchallenges.org/new-shape-library/ (accessed on 2 February 2024).

- Stimson Center. UN 2.0: Ten Innovations for Global Governance. 2020, pp. 60–62. Available online: https://www.stimson.org/wp-content/uploads/2020/06/UN2.0-Ten-Innovations-for-Global-Governance-Final.pdf (accessed on 2 February 2024).

- United Nations General Assembly. Modalities for the Summit of the Future. Document A/RES/76/307. 8 September 2022. Available online: https://digitallibrary.un.org/record/3987340/files/A_RES_76_307-EN.pdf?ln=en (accessed on 2 February 2024).

- Mische, P.M. Ecological Security and the Need to Reconceptualize Sovereignty. Alternatives 1989, 14, 389–427. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Laslier, J.-F. And the loser is … plurality voting, 2011. In Electoral Systems: Paradoxes, Assumptions, and Procedures; Felsenthal, D.S., Machover, M., Eds.; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2012; pp. 327–351. Available online: https://hal.science/hal-00609810/file/cahier_de_recherche_2011-13.pdf (accessed on 2 February 2024).

- de Almeida, A.T.; Nurmi, H. A Framework for Aiding the Choice of a Voting Procedure in a Business Decision Context. In Outlooks and Insights on Group Decision and Negotiation; GDN 2015. Lecture Notes in Business Information Processing; Kamiński, B., Kersten, G., Szapiro, T., Eds.; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2015; Volume 218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gunster, B. Omdenken: The Dutch Art of Flip-Thinking; King Perryman, C., Translator; Lev: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Moore, M.-L.; Milkoreit, M. Imagination and transformations to sustainable and just futures. Elementa 2020, 8, 081:1–081:17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arrow, K.A.; Sen, A.; Suzumura, K. (Eds.) Handbook of Social Choice and Welfare; Elsevier/North-Holland: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Brams, S.J. Mathematics and Democracy. Designing Better Voting Systems and Fair-Division Procedures; Princeton University Press: Princeton, NJ, USA, 2008; Available online: https://www.jstor.org/stable/j.ctt7sxc5 (accessed on 2 February 2024).

- Moulin, H. Axioms of Cooperative Decision Making; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 1988. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amadae, S.M. Impossibility Theorem. In Encyclopedia Britannica Online; Abella, J., Anderson, M., Anderson, M., Ascierto, J., Ashburn, D., Bigelow, F., Chabot, M., Charboneau, Y., Chmielewski, K., Daly, J., et al., Eds.; Encyclopædia Britannica: Chicago, IL, USA, 2015; Available online: https://www.britannica.com/topic/impossibility-theorem (accessed on 2 February 2024).

- Rowley, C.K.; Schneider, F. The Encyclopedia of Public Choice; Springer: New York, NY, USA, 2003; Available online: https://link.springer.com/book/10.1007%2Fb108558 (accessed on 2 February 2024).

- Kabak, Ö.; Ervural, B. Multiple attribute group decision making: A generic conceptual framework and a classification scheme. Knowl. Based Syst. 2017, 123, 13–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ansell, C.; Torfing, J. (Eds.) Handbook of Theories of Governance, 2nd ed.; Edward Elgar: Cheltenham, UK; Northampton, MA, USA, 2022; pp. 433, 611. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Laks, A. Plato’s Second Republic: An Essay on the Laws; Princeton University Press: Princeton, NJ, USA, 2022; p. 19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vandamme, P.-E. What’s wrong with an epistocratic council? Politics 2019, 40, 90–105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tushnet, M. Democratic remedies if ignorance threatens democracy. In Democratic Failure; Schwartzberg, M., Viehoff, D., Eds.; New York University Press: New York, NY, USA, 2021; pp. 262–270. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rothstein, B. Epistemic democracy and the quality of government. Eur. Politics Soc. 2019, 20, 16–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mercier, H.; Landemore, H. Reasoning is for arguing: Understanding the successes and failures of deliberation. Political Psychol. 2012, 33, 243–258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Courtois, P.; Tazdaït, T. Coopération sur le climat: Le mécanisme de négociations jointes. Négociations 2012, 2, 25–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wood, P.J. Climate Change and Game Theory: A Mathematical Survey. Ann. N. Y. Acad. Sci. 2011, 1219, 153–170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Jongh, M.S. Group Dynamics in the Citizens’ Assembly on Electoral Reform. Ph.D. Thesis, Utrecht University, Utrecht, The Netherlands, 2013. Available online: https://dspace.library.uu.nl/handle/1874/275018 (accessed on 2 February 2024).

- van Stokkom, B. Deliberative rituals: Emotional energy and enthusiasm in debating landscape renewal. In Politics and the Emotions: The Affective Turn in Contemporary Political Studies; Hoggett, P., Thompson, S., Eds.; Continuum Press: New York, NY, USA, 2012; pp. 41–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Landemore, H. Open Democracy: Reinventing Popular Rule for the Twenty-First Century; Princeton University Press: Princeton, NJ, USA, 2021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tangian, A. Mathematical Theory of Democracy; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2014. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van Eemeren, F.H.; Garssen, B.; Krabbe, E.C.W.; Snoeck Henkemans, A.F.; Verheij, B.; Wagemans, J.H.M. Handbook of Argumentation Theory; Springer: Dordrecht, The Netherlands, 2014. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Whyte, J. Crimes against Logic: Exposing the Bogus Arguments of Politicians, Priests, Journalists, and Other Serial Offenders; McGraw-Hill: New York, NY, USA, 2017; pp. 75, 153. [Google Scholar]

- Dittrich, R.; Wreford, A.; Moran, D. A survey of decision-making approaches for climate change adaptation: Are robust methods the way forward? Ecol. Econ. 2016, 122, 79–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gilboa, I. Making Better Decisions; Wiley-Blackwell: Chichester, UK, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Buchanan, A. Institutional Legitimacy. In Oxford Studies in Political Philosophy; Sobel, D., Vallentyne, P., Wall, S., Eds.; Oxford University Press: Oxford, UK, 2018; Volume 4, pp. 53–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adams, N.P. Legitimacy and institutional purpose. Crit. Rev. Int. Soc. Political Philos. 2020, 23, 292–310. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lahsen, M.; Turnhout, E. How norms, needs, and power in science obstruct towards sustainability. Environ. Res. Lett. 2021, 16, 025008:1–025008:10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Köpke, S. Interrogating the Links between Climate Change, Food Crises and Social Stability. Earth 2022, 3, 577–589. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Falkenberg, M.; Galeazzi, A.; Torricelli, M.; Di Marco, N.; Larosa, F.; Sas, M.; Mekacher, A.; Pearce, W.; Zollo, F.; Quattrociocchi, W.; et al. Growing polarization around climate change on social media. Nat. Clim. Change 2022, 12, 1114–1121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Geiß, S.; Magin, M.; Jürgens, P.; Stark, B. Loopholes in the Echo Chambers: How the Echo Chamber Metaphor Oversimplifies the Effects of Information Gateways on Opinion Expression. Digit. Journalism 2021, 9, 660–686. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Geels, F.W. Regime Resistance against Low-Carbon Transitions: Introducing Politics and Power into the Multi-Level Perspective. Theory Cult. Soc. 2014, 31, 21–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brulle, R.J.; Dunlap, R.E. A Sociological View of the Effort to Obstruct Action on Climate Change. Footnotes 2021, 49. Available online: https://www.asanet.org/sociological-view-effort-obstruct-action-climate-change (accessed on 2 February 2024).

- White, D.F.; Rudy, A.; Wilbert, C. Anti-Environmentalism: Prometheans, Contrarians, and beyond. In Sage Handbook in Environment & Society; Pretty, J., Ball, A.S., Benton, T., Guivant, J.S., Lee, D.R., Orr, D., Pfeffer, M.J., Ward, H., Eds.; Sage: Los Angeles, CA, USA, 2007; pp. 124–141. Available online: https://www.researchgate.net/publication/277007692 (accessed on 2 February 2024).

- Eaton, E.M.; Day, N.A. Petro-pedagogy: Fossil fuel interests and the obstruction of climate justice in public education. Environ. Educ. Res. 2020, 26, 457–473. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blythe, J.; Silver, J.; Evans, L.; Armitage, D.; Bennett, N.J.; Moore, M.-L.; Morrison, T.H.; Brown, K. The Dark Side of Transformation: Latent Risks in Contemporary Sustainability Discourse. Antipode 2018, 50, 1206–1223; risks 1 and 2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lewandowsky, S. Climate Change Disinformation and How to Combat It. Annu. Rev. Public Health 2021, 42, 1–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Avelino, F. Theories of power and social change: Power contestations and their implications for research on social change and innovation. J. Political Power 2021, 14, 425–448. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chomsky, N. The Common Good. In How the World Works; Chomsky, N., Barsamian, D., Naiman, A., Eds.; Hamish Hamilton: London, UK, 2011; pp. 206–314. [Google Scholar]

- Bradshaw, C.J.A.; Ehrlich, P.R.; Beattie, A.; Ceballos, G.; Crist, E.; Diamond, J.; Dirzo, R.; Ehrlich, A.H.; Harte, J.; Harte, M.E.; et al. Underestimating the Challenges of Avoiding a Ghastly Future. Front. Conserv. Sci. 2021, 1, 615419:1–615419:10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lix, K.; Goldberg, A.; Srivastava, S.M.; Valentine, M.A. Aligning Differences: Discursive Diversity and Team Performance. Manag. Sci. 2022, 68, 8430–8448. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gershkov, A.; Schweinzer, P. Dream teams and the Apollo effect. J. Mech. Inst. Des. 2021, 6, 113–148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Davis, J.W. A critical view of global governance. Swiss Political Sci. Rev. 2012, 18, 272–286. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Friedman, J. Power without Knowledge: A Critique of Technocracy; Oxford Academic: New York, NY, USA, 2019; p. 213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cole, M. What’s Wrong with Technocracy? Boston Rev. 22 August 2022. Available online: https://www.bostonreview.net/articles/whats-wrong-with-technocracy/ (accessed on 2 February 2022).

- Parlementair Documentatie Centrum. Minister Ollongren Presenteert Voorstellen tot Hervorming Parlementair Stelsel. 1 July 2020. Available online: https://www.parlement.com/id/vl9zdaltm4y3/nieuws/minister_ollongren_presenteert (accessed on 2 February 2024).

- Parlementair Documentatie Centrum. Burgerforum Kiesstelsel. Available online: https://www.parlement.com/id/vhnnmt7ltkw7/burgerforum_kiesstelsel (accessed on 2 February 2024).

- Fleming, D. Icon. In Lean Logic: A Dictionary for the Future and How to Survive It; Fleming, D., Chamberlin, S., Eds.; Chelsea Green: White River Junction, VT, USA, 2016; pp. 204–206. Available online: https://leanlogic.online/glossary/icon-the/ (accessed on 2 February 2024).

- Weisbord, M.; Janoff, S. Future Search: Getting the Whole System in the Room for Vision, Commitment, and Action; Berrett-Koehler: San Francisco, CA, USA, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Tonn, B.E. The future of futures decision making. Futures 2003, 35, 673–688. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burgers, L.E. Justitia, the People’s Power and Mother Earth. Democratic Legitimacy of Judicial Law-Making in European Private Law Cases on Climate Change. Ph.D. Thesis, University of Amsterdam, Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2020. Available online: https://dare.uva.nl/search?identifier=0e6437b7-399d-483a-9fc1-b18ca926fdb5 (accessed on 2 February 2024).

- Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development. Beyond Growth: Towards a New Economic Approach, New Approaches to Economic Challenges; OECD Publishing: Paris, France, 2020; p. 15. Available online: https://read.oecd-ilibrary.org/economics/beyond-growth_33a25ba3-en (accessed on 2 February 2024).

- Portail de Collapsologie. Better Understand the Current Risks of Social and Environmental Collapses. Available online: https://collapsologie.fr/en/ (accessed on 2 February 2024).

- Woollard, F.; Howard-Snyder, F. Doing vs. Allowing Harm, 7 July 2021. In Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy; Zalta, E.N., Nodelman, U., Eds.; Metaphysics Research Lab: Stanford, CA, USA, 2002; Available online: https://plato.stanford.edu/entries/doing-allowing/ (accessed on 2 February 2024).

- Gardiner, S.M. Ethics and Global Climate Change. Ethics 2004, 114, 555–600. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schröder, W. Moralischer Nihilismus. Radikale Moralkritik von den Sophisten bis Nietzsche; Reclam: Stuttgart, Germany, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Wright, J.C.; Pölzler, T. Should morality be abolished? An empirical challenge to the argument from intolerance. Philos. Psychol. 2022, 35, 350–385. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heilbroner, R.L. Reflections on the future of socialism. In Between Capitalism and Socialism; Vintage Books: New York, NY, USA, 1970; pp. 79–114. [Google Scholar]

- Hurwicz, L. Economic design, adjustment processes, mechanisms, and institutions. Econ. Des. 1994, 1, 1–14. Available online: https://link.springer.com/article/10.1007/BF02716611 (accessed on 2 February 2024). [CrossRef]

- Energy Exascale Earth System Model. CMIP6’s Scenario-Based Temperature and Precipitation Projections. 26 May 2021. Available online: https://e3sm.org/cmip6s-scenario-based-temperature-and-precipitation-projections/ (accessed on 2 February 2024).

- Pörtner, H.-O.; Roberts, D.C.; Tignor, M.; Poloczanska, E.S.; Mintenbeck, K.; Alegría, A.; Craig, M.; Langsdorf, S.; Löschke, S.; Möller, V.; et al. (Eds.) Climate Change 2022: Impacts, Adaptation and Vulnerability. Contribution of Working Group II to the Sixth Assessment Report of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 2022; pp. 8, 16–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Masson-Delmotte, V.; Zhai, P.; Pirani, A.; Connors, S.L.; Péan, C.; Berger, S.; Caud, N.; Chen, Y.; Goldfarb, L.; Gomis, M.I.; et al. (Eds.) Climate Change 2021: The Physical Science Basis. Contribution of Working Group I to the Sixth Assessment Report of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 2021; pp. 12, 15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- World Meteorological Organization. United in Science 2020: A Multi-Organization High-Level Compilation of the Latest Climate Science Information; Figure 2. 2020, p. 16. Available online: https://library.wmo.int/idurl/4/57145 (accessed on 2 February 2024).

- World Meteorological Organization. United In Science 2022: A Multi-Organization High-Level Compilation of the Most Recent Science Related to Climate Change, Impacts and Responses. Summary. 2022. Available online: https://library.wmo.int/idurl/4/58075 (accessed on 2 February 2024).

- World Meteorological Organization. Global Annual to Decadal Climate Update. Summary. 2023. Available online: https://library.wmo.int/idurl/4/68235 (accessed on 2 February 2024).

- United Nations Environment Programme. Broken Record. Temperatures Hit New Highs, yet World Fails to Cut Emissions (again). Item 7. 2023, p. XXII. Available online: https://www.unep.org/resources/emissions-gap-report-2023 (accessed on 2 February 2024).

- Rothenberg, G. A realistic look at CO2 emissions, climate change and the role of sustainable chemistry. Sustain. Chem. Clim. Action 2023, 2, 100012:1–100012:5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change. First Global Stocktake. Proposal by the President, Document FCCC/PA/CMA/2023/L.17; Items 18, 21, 25 ff, and 173. 13 December 2023. Available online: https://unfccc.int/sites/default/files/resource/cma2023_L17_adv.pdf (accessed on 2 February 2024).

- Rohde, R. September 2023 Temperature Update. Berkeley Earth. 11 November 2023. Available online: https://berkeleyearth.org/september-2023-temperature-update (accessed on 2 February 2024).

- Harmsen, M.; Tabak, C.; Höglund-Isaksson, L.; Humpenöder, F.; Purohit, P.; van Vuuren, D. Uncertainty in non-CO2 greenhouse gas mitigation contributes to ambiguity in global climate policy feasibility. Nat. Commun. 2023, 14, 2949:1–2949:14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dafnomilis, I.; den Elzen, M.; van Vuuren, D. Paris targets within reach by aligning, broadening and strengthening net-zero pledges. Commun. Earth Environ. 2024, 5, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- United Nations. COP28 Ends with Call to ‘Transition Away’ from Fossil Fuels; UN’s Guterres Says Phaseout Is Inevitable. UN News. 13 December 2023. Available online: https://news.un.org/en/story/2023/12/1144742 (accessed on 2 February 2024).

- Masson-Delmotte, V.; Zhai, P.; Pörtner, H.-O.; Roberts, D.; Skea, J.; Shukla, P.R.; Pirani, A.; Moufouma-Okia, W.; Péan, C.; Pidcock, R.; et al. (Eds.) Global Warming of 1.5 °C: An IPCC Special Report on the Impacts of Global Warming of 1.5 °C above Pre-Industrial Levels and Related Global Greenhouse Gas Emission Pathways, in the Context of Strengthening the Global Response to the Threat of Climate Change, Sustainable Development, and Efforts to Eradicate Poverty; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 2018; pp. 96, 116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Waddock, S. Thinking Transformational System Change. J. Change Manag. 2020, 20, 189–201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eilstrup-Sangiovanni, M. Death of international organizations. The organizational ecology of intergovernmental organizations, 1815–2015. Rev. Int. Organ. 2020, 15, 339–370. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Union of International Associations. The Yearbook of International Organizations; Brill: Leiden, The Netherlands, 2023; Available online: https://uia.org/yearbook (accessed on 2 February 2024).

- Vandenbergh, M.P.; Jonathan, M.; Gilligan, J.M. Beyond Politics: The Private Governance Response to Climate Change; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 2017; p. xviii. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buchanan, A. The Heart of Human Rights; Oxford University Press: Oxford, UK, 2013; p. 178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scherz, A.; Zysset, A. The UN Security Council, normative legitimacy and the challenge of specificity. Crit. Rev. Int. Soc. Political Philos. 2020, 23, 371–391. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tindall, D.B.; Stoddart, M.C.J.; Dunlap, R.E. (Eds.) Handbook of Anti-Environmentalism; Edward Elgar: Cheltenham, UK; Northampton, MA, USA, 2022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fleming, D. How to cheat in an argument. In Lean Logic: A Dictionary for the Future and How to Survive It; Fleming, D., Chamberlin, S., Eds.; Chelsea Green: White River Junction, VT, USA, 2016; pp. xxiii–xxvi. Available online: https://leanlogic.online/how-to-cheat-in-an-argument/ (accessed on 2 February 2024).

- Lamb, W.F.; Mattioli, G.; Levi, S.; Timmons Roberts, J.; Capstick, S.; Creutzig, F.; Minx, J.C.; Müller-Hansen, F.; Culhane, T.; Steinberger, J.K. Discourses of Climate Delay. Glob. Sustain. 2020, 3, e17:1–e17:5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Steinberger, J.K. Struggle for Survival: The Importance of Climate Activism from the Perspectives of Political Economy and Science Communication, 5 October 2021; at 00:41. Available online: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=2973tOyZ-TA (accessed on 2 February 2024).

- Grostern, J.; Herrmann, M.; Cooke, P. Revealed: Scale of The Telegraph’s Climate Change ‘Propaganda’. DeSmog. 23 November 2023; Seattle, WA, USA; London, UK. 2023. Available online: https://www.desmog.com/2023/11/23/revealed-scale-of-the-telegraphs-climate-change-propaganda/ (accessed on 2 February 2024).

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Bomans, A.J.; Roessingh, P. Decision Change: The First Step to System Change. Sustainability 2024, 16, 2372. https://doi.org/10.3390/su16062372

Bomans AJ, Roessingh P. Decision Change: The First Step to System Change. Sustainability. 2024; 16(6):2372. https://doi.org/10.3390/su16062372

Chicago/Turabian StyleBomans, Arnold J., and Peter Roessingh. 2024. "Decision Change: The First Step to System Change" Sustainability 16, no. 6: 2372. https://doi.org/10.3390/su16062372

APA StyleBomans, A. J., & Roessingh, P. (2024). Decision Change: The First Step to System Change. Sustainability, 16(6), 2372. https://doi.org/10.3390/su16062372