The Impact of COVID-19 on Attitudes towards Growth Capacity of Tourism Firms: Evidence from Greece

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Literature Review

2.1. Growth Capacity of Firms and Organizations

2.2. Impact of COVID-19 on Growth Capacity of Tourism Firms—Firm Factors

2.3. Personal Factors

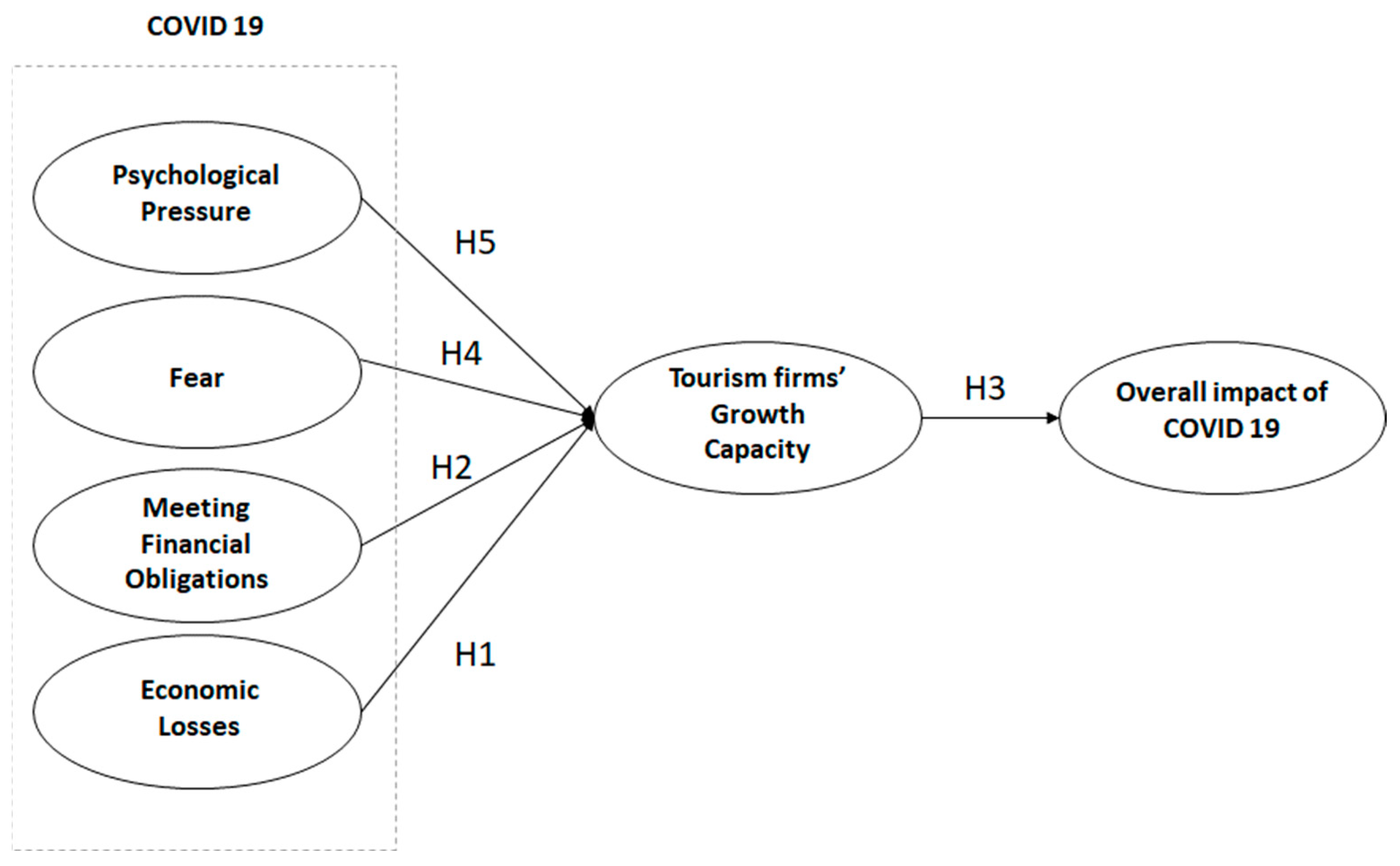

3. Research Method

3.1. Research Process

3.2. Research Instrument

3.3. Methods of Analysis

4. Results

4.1. Exploratory Factor Analysis (EFA)

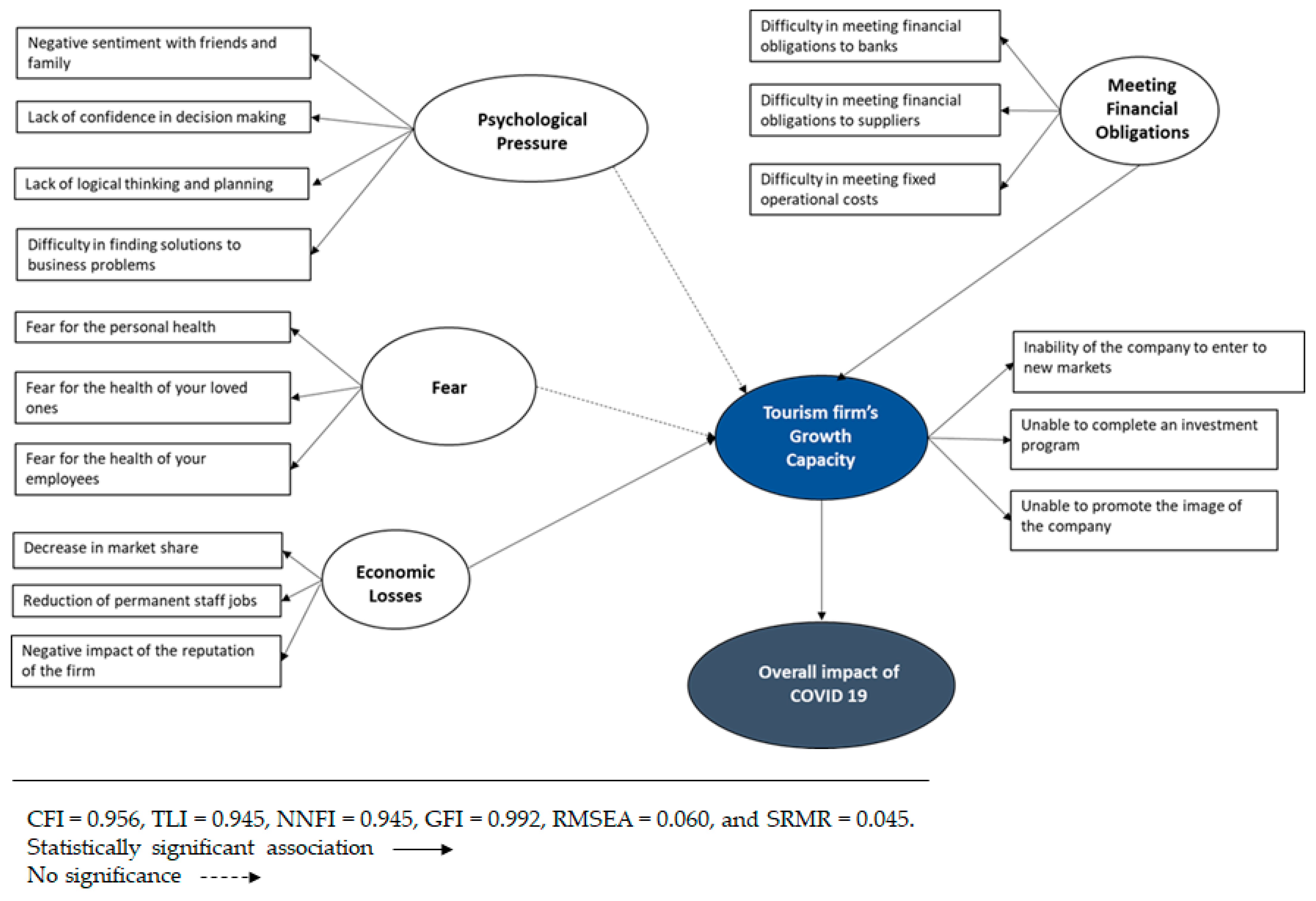

4.2. Confirmatory Factor Analysis (CFA)

4.3. Structural Model

5. Discussion

6. Practical Contributions and Implications

- -

- Financial support and stimulus packages.

- -

- Tax incentives: these could include reduced VAT or sales tax rates for tourism-related services such as accommodation, transportation, and entertainment.

- -

- Investment in infrastructures (transportation networks, attractions, etc.).

- -

- Organization of public campaigns that promote cultural heritage and unique experiences.

- -

- Establishment of clear health and safety protocols: these standards will help restore consumer confidence by ensuring that travelers can enjoy their trips without unnecessary health risks.

- -

- Training programs for tourism industry workers to upgrade their skills and adapt to new trends such as digital marketing, contactless service, and sustainability practices.

- -

- Broad support of small and medium enterprises (SMEs), which constitute the backbone of the Greek economy (grants, loans, and capacity-building initiatives).

- -

- Focus on sustainability by promoting eco-friendly practices, supporting local communities, and protecting natural and cultural resources.

- -

- Provide incentives for the digital transformation of the industry.

7. Research Limitations

8. Suggestions for Further Research

9. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A

| Extent of the Negative Impact of COVID-19 on the Overall Function of Greek Tourism Enterprises | Sources |

|---|---|

| Firm factors—negative impact of COVID-19 on… | |

| [20,21,22] |

| [2,20,21,22,23] |

| [20] |

| [23,24,25,26] |

| [15,16] |

| [27,28] |

| [27,28] |

| [27,28] |

| [23,24] |

| [29] |

| [29,54] |

| [4] |

| [29] |

| [23,25,30,31] |

| [29] |

| Personal factors | |

| [34] |

| [34] |

| [29,34] |

| [29,38] |

| [29,38] |

| [29,38] |

| [29,38] |

| [29] |

| [29] |

| [4] |

| [42] |

| [42] |

| [42] |

| [42] |

| [4] |

References

- Yu, Z.; Razzaq, A.; Rehman, A.; Shah, A.; Jameel, K.; Mor, R.S. Disruption in global supply chain and socio-economic shocks: A lesson from COVID-19 for sustainable production and consumption. Oper. Manag. Res. 2021, 15, 233–248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shen, H.; Fu, M.; Pan, H.; Yu, Z.; Chen, Y. The impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on firm performance. Emerg. Mark. Financ. Trade 2020, 56, 2213–2230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Greek Tourism Confederation (SETE). Available online: https://sete.gr/el/ (accessed on 1 September 2023).

- Gavriilidis, G.; Metaxas, T. The impact of COVID 19 on tourism enterprises in Greece. J. Dev. Areas 2023, 57, 293–314. [Google Scholar]

- Ioannides, D.; Gyimóthy, S. The COVID-19 crisis as an opportunity for escaping the unsustainable global tourism path. Tour. Geogr. 2020, 22, 624–632. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gössling, S.; Scott, D.; Hall, C.M. Pandemics, tourism and global change: A rapid assessment of COVID-19. J. Sustain. Tour. 2020, 29, 1–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pugsley, B.W.; Sedlacek, P.; Sterk, V. The nature of firm growth. Am. Econ. Rev. 2019, 11, 547–579. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Doyle, P. Value Based Marketing; Wiley and Sons: Chichester, UK, 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Kotler, P.; Keller, K. Marketing Management, 12th ed.; USA Prentice-Hall: Upper Saddle River, NJ, USA, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Lee, C.Y. A theory of firm growth: Learning capability, knowledge threshold, and patterns of growth. Res. Policy 2010, 39, 278–289. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, X.; Zou, H.; Wang, D.T. How do new ventures grow? Firm capabilities, growth strategies and performance. Int. J. Res. Mark. 2009, 26, 294–303. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eshima, Y.; Anderson, B.S. Firm growth, adaptive capability, and entrepreneurial orientation. Strateg. Manag. J. 2017, 38, 770–779. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lam-González, Y.E.; Suárez-Rojas, C.; León, C.J. Factors constraining international growth in nautical tourism firms. Sustainability 2019, 11, 6846. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Erkuş-Öztürk, H. Emerging importance of institutional capacity for the growth of tourism clusters: The case of Antalya. Eur. Plan. Stud. 2011, 19, 1735–1753. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, J.; Huang, X.; Gong, Z.; Cao, K. Dynamic assessment of tourism carrying capacity and its impacts on tourism economic growth in urban tourism destinations in China. J. Destin. Mark. Manag. 2020, 15, 100383. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, Y.; Ritchie, B.W.; Verreynne, M.L. Building tourism organizational resilience to crises and disasters: A dynamic capabilities view. Int. J. Tour. Res. 2019, 21, 882–900. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jin, X.C.; Qu, M.; Bao, J. Impact of crisis events on Chinese outbound tourist flow: A framework for post-events growth. Tour. Manag. 2019, 74, 334–344. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- García-Villaverde, P.M.; Elche, D.; Martinez-Perez, A. Understanding pioneering orientation in tourism clusters: Market dynamism and social capital. Tour. Manag. 2020, 76, 103966. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cerović Smolović, J.; Janketić, S.; Jaćimović, D.; Bučar, M.; Stare, M. Montenegro’s road to sustainable tourism growth and innovation. Sustainability 2018, 10, 4687. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Assaf, A.; Scuderi, R. COVID-19 and the recovery of the tourism industry. Tour. Econ. 2020, 26, 731–733. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hao, F.; Xiao, Q.; Chon, K. COVID-19 and China’s Hotel Industry: Impacts, a Disaster Management Framework, and Post-Pandemic Agenda. Int. J. Hosp. Manag. 2020, 90, 102636. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Farmaki, A.; Miguel, C.; Drotarova, M.H.; Aleksić, A.; Časni, A.Č.; Efthymiadou, F. Impacts of Covid-19 on peer-to-peer accommodation platforms: Host perceptions and responses. Int. J. Hosp. Manag. 2020, 91, 102663. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abebe, G.; Bundervoet, T.; Wieser, C. Monitoring COVID-19 Impacts on Firms in Ethiopia: Results from a High-Frequency Phone Survey of Firms. World Bank Rep. 2020, 7, 148538. [Google Scholar]

- Baum, T.; Mooney, S.K.; Robinson, R.N.; Solnet, D. COVID-19’s impact on the hospitality workforce–new crisis or amplification of the norm? Int. J. Contemp. Hosp. Manag. 2020, 32, 2813–2829. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bas, T.; Sivaprasad, S. The Impact of the COVID-19 Pandemic Crisis on the Travel and Tourism Sector: UK Evidence. SSRN Electron. J. 2020, 1–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, A.; Makridis, C.; Baker, M.; Medeiros, M.; Guo, Z. Understanding the Impact of COVID-19 Intervention Policies on the Hospitality Labor Market. Int. J. Hosp. Manag. 2020, 91, 102660. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sharma, A.; Nicolau, J.L. An open market valuation of the effects of COVID-19 on the travel and tourism industry. Ann. Tour. Res. 2020, 83, 102990. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xiong, H.; Wu, Z.; Hou, F.; Zhang, J. Which Firm-specific Characteristics Affect the Market Reaction of Chinese Listed Companies to the COVID-19 Pandemic? Emerg. Mark. Financ. Trade 2020, 56, 2231–2242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sigala, M. Tourism and COVID-19: Impacts and implications for advancing and resetting industry and research. J. Bus. Res. 2020, 117, 312–321. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nicola, M.; Alsafi, Z.; Sohrabi, C.; Kerwan, A.; Al-Jabir, A.; Iosifidis, C.; Agha, M.; Agha, R. The socio-economic implications of the coronavirus pandemic (COVID-19): A review. Int. J. Surg. 2020, 78, 185–193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baum, T.; Hai, N.T.T. Hospitality, tourism, human rights and the impact of COVID-19. Int. J. Contemp. Hosp. Manag. 2020, 32, 2397–2407. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sobaih, A.E.E.; Elshaer, I.; Hasanein, A.M.; Abdelaziz, A.S. Responses to COVID-19: The role of performance in the relationship between small hospitality enterprises’ resilience and sustainable tourism development. Int. J. Hosp. Manag. 2021, 94, 102824. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wieczorek-Kosmala, M. A study of the tourism industry’s cash-driven resilience capabilities for responding to the COVID-19 shock. Tour. Manag. 2022, 88, 104396. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, B.; Pennington-Gray, L.; Krieger, J. Tourism crisis management: Can the extended parallel process model be used to understand crisis responses in the cruise industry? Tour. Manag. 2016, 55, 310–321. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fofana, N.K.; Latif, F.; Sarfraz, S.; Bashir, M.F.; Komal, B. Fear and agony of the pandemic leading to stress and mental illness: An emerging crisis in the novel coronavirus (COVID-19) outbreak. Psychiatry Res. 2020, 291, 113230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cheng, T.M.; Hong, C.Y.; Zhong, Z.F. Tourism employees’ fear of COVID-19 and its effect on work outcomes: The role of organizational support. Curr. Issues Tour. 2022, 25, 319–337. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kang, S.E.; Park, C.; Lee, C.K.; Lee, S. The stress-induced impact of COVID-19 on tourism and hospitality workers. Sustainability 2021, 13, 1327. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yin, J.; Ni, Y. COVID-19 event strength, psychological safety, and avoidance coping behaviors for employees in the tourism industry. J. Hosp. Tour. Manag. 2021, 47, 431–442. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mao, Y.; He, J.; Morrison, A.M.; Andres Coca-Stefaniak, J. Effects of tourism CSR on employee psychological capital in the COVID-19 crisis: From the perspective of conservation of resources theory. Curr. Issues Tour. 2021, 24, 2716–2734. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aguiar-Quintana, T.; Nguyen, T.H.H.; Araujo-Cabrera, Y.; Sanabria-Díaz, J.M. Do job insecurity, anxiety and depression caused by the COVID-19 pandemic influence hotel employees’ self-rated task performance? The moderating role of employee resilience. Int. J. Hosp. Manag. 2021, 94, 102868. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tu, Y.; Li, D.; Wang, H.J. COVID-19-induced layoff, survivors’ COVID-19-related stress and performance in hospitality industry: The moderating role of social support. Int. J. Hosp. Manag. 2021, 95, 102912. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pathak, D.; Joshi, G. Impact of psychological capital and life satisfaction on organizational resilience during COVID-19: Indian tourism insights. Curr. Issues Tour. 2021, 24, 2398–2415. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stutely, M. Numbers Guide: The Essentials of Business Numeracy; Bloomberg Press: London, UK, 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Saunders, M.; Lewis, P.; Thornhill, A. Research Methods for Business Students; Pearson: Harlow, UK, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Greek Tourism Confederation (SETE). Available online: https://sete.gr/en/basic-figures-repository/ (accessed on 1 November 2021).

- Malhotra, N.; Birks, D. Marketing Research: An Applied Approach, 2nd European ed.; Pearson Education: Harlow, UK, 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Malhotra, N.; Birks, D. Marketing Research: An Applied Approach, 3rd European ed.; Pearson Education: Harlow, UK, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Piovesana, A.; Senior, G. How small is big: Sample size and skewness. Assessment 2018, 25, 793–800. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lance, C.E.; Vandenberg, R.J. Confirmatory factor analysis. In Measuring and Analyzing Behavior in Organizations: Advances in Measurement and Data Analysis; Drasgow, F., Schmitt, N., Eds.; Wiley: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2002; pp. 221–254. [Google Scholar]

- Hair, J.F., Jr.; Babin, B.J.; Krey, N. Covariance-based structural equation modeling in the Journal of Advertising: Review and recommendations. J. Advert. 2017, 46, 163–177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hooper, D.; Coughlan, J.; Mullen, M. Evaluating model fit: A synthesis of the structural equation modelling literature. In Proceedings of the 7th European Conference on Research Methodology for Business and Management Studies, London, UK, 19–20 June 2008; pp. 195–200. [Google Scholar]

- Fornell, C.; Larcker, D.F. Evaluating structural equation models with unobservable variables and measurement error. J. Mark. Res. 1981, 18, 39–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mandić, A.; Walia, S.K.; Rasoolimanesh, S.M. Gen Z and the flight shame movement: Examining the intersection of emotions, biospheric values, and environmental travel behaviour in an Eastern society. J. Sustain. Tour. 2023, 1–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hall, C.M.; Scott, D.; Gössling, S. Pandemics, transformations and tourism: Be careful what you wish for. Tour. Geogr. 2020, 22, 577–598. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Personal Characteristics | ||

| Gender | n | % |

| Male | 360 | 65.7 |

| Female | 188 | 34.3 |

| Age | ||

| 18–24 | 7 | 1.3 |

| 25–34 | 107 | 19.5 |

| 35–49 | 293 | 53.5 |

| 50–65 | 133 | 24.3 |

| >65 | 8 | 1.5 |

| Educational level | ||

| High school | 118 | 21.5 |

| University/College | 267 | 48.7 |

| Master’s degree and/or PhD | 163 | 29.7 |

| Work experience in the tourism industry (in years) | ||

| <1 | 6 | 1.1 |

| 1–4 | 43 | 7.8 |

| 5–9 | 96 | 17.5 |

| 10–14 | 83 | 15.1 |

| 15–19 | 89 | 16.2 |

| ≥20 | 231 | 42.2 |

| Position in the company | ||

| Owner/CEO | 270 | 49.3 |

| Employee | 278 | 50.7 |

| Total | 548 | 100.0 |

| Firms’ Characteristics | ||

| Legal form | n | % |

| Sole proprietorship | 146 | 26.6 |

| General partnership (OΕ) | 67 | 12.2 |

| Limited liability company | 39 | 7.1 |

| S.A. | 172 | 31.4 |

| Franchise | 3 | 0.6 |

| Member of a group | 70 | 12.8 |

| Other | 51 | 9.3 |

| Years of operation | ||

| <1 | 15 | 2.7 |

| 1–4 | 64 | 11.7 |

| 5–9 | 86 | 15.7 |

| 10–14 | 93 | 17.0 |

| 15–19 | 60 | 10.9 |

| ≥20 | 230 | 42.0 |

| Industry | ||

| Hospitality | 320 | 58.4 |

| Bars and restaurants | 76 | 13.9 |

| Travel agencies | 75 | 13.7 |

| Other services | 77 | 14.1 |

| Total | 548 | 100.0 |

| Construct | Items | Factor Loadings | Cronbach A | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Psychological impact | F1: Psychological pressure | Negative psychology in managing customer relationships | 0.741 | 0.918 |

| Negative psychology in managing relationships with the staff | 0.746 | |||

| Negative sentiment with friends and family | 0.799 | |||

| Lack of confidence in decision making | 0.815 | |||

| Lack of logical thinking and planning | 0.848 | |||

| Difficulty in finding solutions to business problems | 0.758 | |||

| Difficulty in performing everyday job tasks | 0.593 | |||

| F2: Fear towards the effects the new virus health | Fear for the effects on personal | 0.778 | 0.858 | |

| Fear for the health of loved ones | 0.877 | |||

| Fear for the health of employees | 0.836 | |||

| Economic impact | F3: Meeting financial obligations | Difficulty in meeting financial obligations to public organizations | 0.738 | 0.930 |

| Difficulty in meeting financial obligations to banks | 0.735 | |||

| Difficulty in meeting financial obligations to suppliers | 0.705 | |||

| Difficulty in meeting fixed operational costs | 0.727 | |||

| F4: Growth capacity | Unable to create new products/services | 0.666 | 0.814 | |

| Unable to complete an investment program | 0.598 | |||

| Unable to promote the image of the company | 0.541 | |||

| Unable to create new job positions | 0.725 | |||

| Inability of the company to enter new markets | 0.615 | |||

| F5: Economic losses | Negative impact of the reputation of the firm | 0.655 | 0.687 | |

| Decrease in market share | 0.617 | |||

| Reduction in permanent staff jobs | 0.545 | |||

| Kaiser–Meyer–Olkin | 0.928 | |||

| Sig. | 0.000 |

| Factor | Indicator | Loadings | AVE | CR |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Psychological pressure | Lack of confidence in decision making | 0.866 | 0.680 | 0.894 |

| (PP) | Lack of logical thinking and planning | 0.901 | ||

| Negative sentiment with friends and family | 0.707 | |||

| Difficulty in finding solutions to business problems | 0.812 | |||

| Fear for the new virus | Fear for personal health | 0.761 | 0.677 | 0.862 |

| (FEAR) | Fear for the health of loved ones | 0.900 | ||

| Fear for the health of employees | 0.802 | |||

| Meeting financial obligations | Difficulty in meeting financial obligations to banks | 0.898 | 0.781 | 0.915 |

| (MFO) | Difficulty in meeting financial obligations to suppliers | 0.895 | ||

| Difficulty in meeting fixed operational costs | 0.858 | |||

| Growth capacity | Unable to complete an investment program | 0.737 | 0.612 | 0.825 |

| (GC) | Unable to promote the image of the company | 0.880 | ||

| Inability of the company to enter new markets | 0.721 | |||

| Economic losses | Decrease in market share | 0.731 | 0.430 | 0.692 |

| (EL) | Reduction of permanent staff jobs | 0.623 | ||

| Negative impact on the reputation of the firm | 0.606 |

| Construct | CR | AVE | PP | FEAR | MFO | GC | EL |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| PP | 0.894 | 0.680 | 0.824 | ||||

| FEAR | 0.862 | 0.677 | 0.335 | 0.822 | |||

| MFO | 0.915 | 0.781 | 0.410 | 0.218 | 0.883 | ||

| GC | 0.825 | 0.612 | 0.420 | 0.236 | 0.629 | 0.782 | |

| EL | 0.692 | 0.430 | 0.399 | 0.246 | 0.515 | 0.547 | 0.655 |

| Hypotheses | Structural Coefficient | p Value | Status |

|---|---|---|---|

| H5: Impact of PP on growth capacity | 0.120 | 0.016 | Rejected |

| H4: Impact of fear on growth capacity | 0.004 | 0.924 | Rejected |

| H2: Impact of MFO on growth capacity | 0.314 | <0.001 * | Accepted |

| H1: Impact of EL on growth capacity | 0.407 | <0.001 * | Accepted |

| H3: Impact of growth capacity on the overall performance of tourism enterprises due to COVID-19 | 0.192 | <0.001 * | Accepted |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Gavriilidis, G.; Metaxas, T. The Impact of COVID-19 on Attitudes towards Growth Capacity of Tourism Firms: Evidence from Greece. Sustainability 2024, 16, 2371. https://doi.org/10.3390/su16062371

Gavriilidis G, Metaxas T. The Impact of COVID-19 on Attitudes towards Growth Capacity of Tourism Firms: Evidence from Greece. Sustainability. 2024; 16(6):2371. https://doi.org/10.3390/su16062371

Chicago/Turabian StyleGavriilidis, Gaby, and Theodore Metaxas. 2024. "The Impact of COVID-19 on Attitudes towards Growth Capacity of Tourism Firms: Evidence from Greece" Sustainability 16, no. 6: 2371. https://doi.org/10.3390/su16062371

APA StyleGavriilidis, G., & Metaxas, T. (2024). The Impact of COVID-19 on Attitudes towards Growth Capacity of Tourism Firms: Evidence from Greece. Sustainability, 16(6), 2371. https://doi.org/10.3390/su16062371