The Impact of Cross-Border Mergers and Acquisitions on Corporate Organisational Resilience: Insights from Dynamic Capability Theory

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Theory and Hypotheses

2.1. Defining and Measuring Corporate Organisational Resilience

2.2. Cross-Border M&As and Corporate Organisational Resilience

2.3. Cross-Border M&As, CSR and Corporate Organisational Resilience

2.4. Cross-Border M&As, Market Power and Corporate Organisational Resilience

3. Data and Methods

3.1. Model Specification

3.2. Variables

3.2.1. Dependent Variables

3.2.2. Control Variables

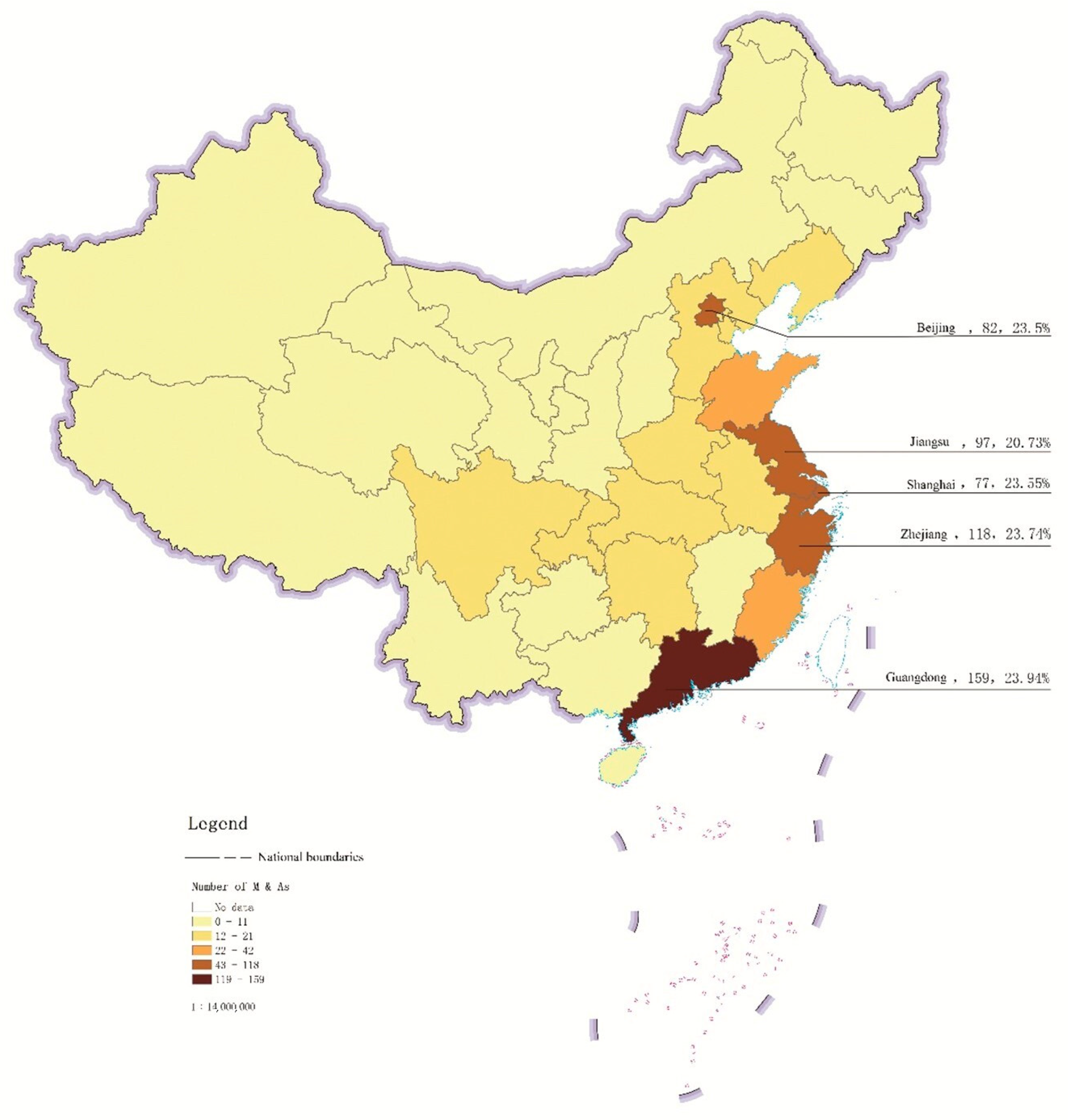

3.3. Data and Sample

4. Results

4.1. Basic Results

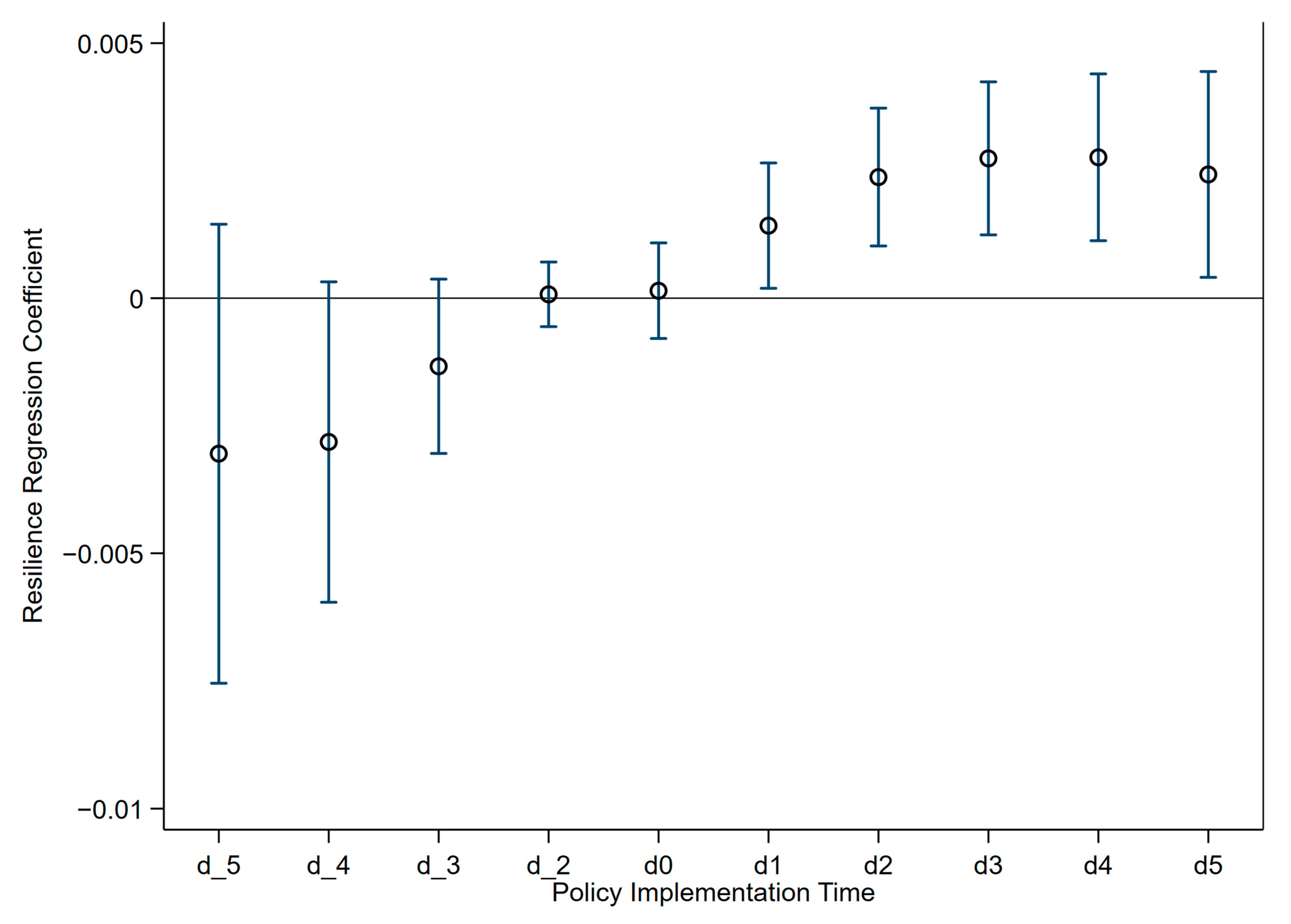

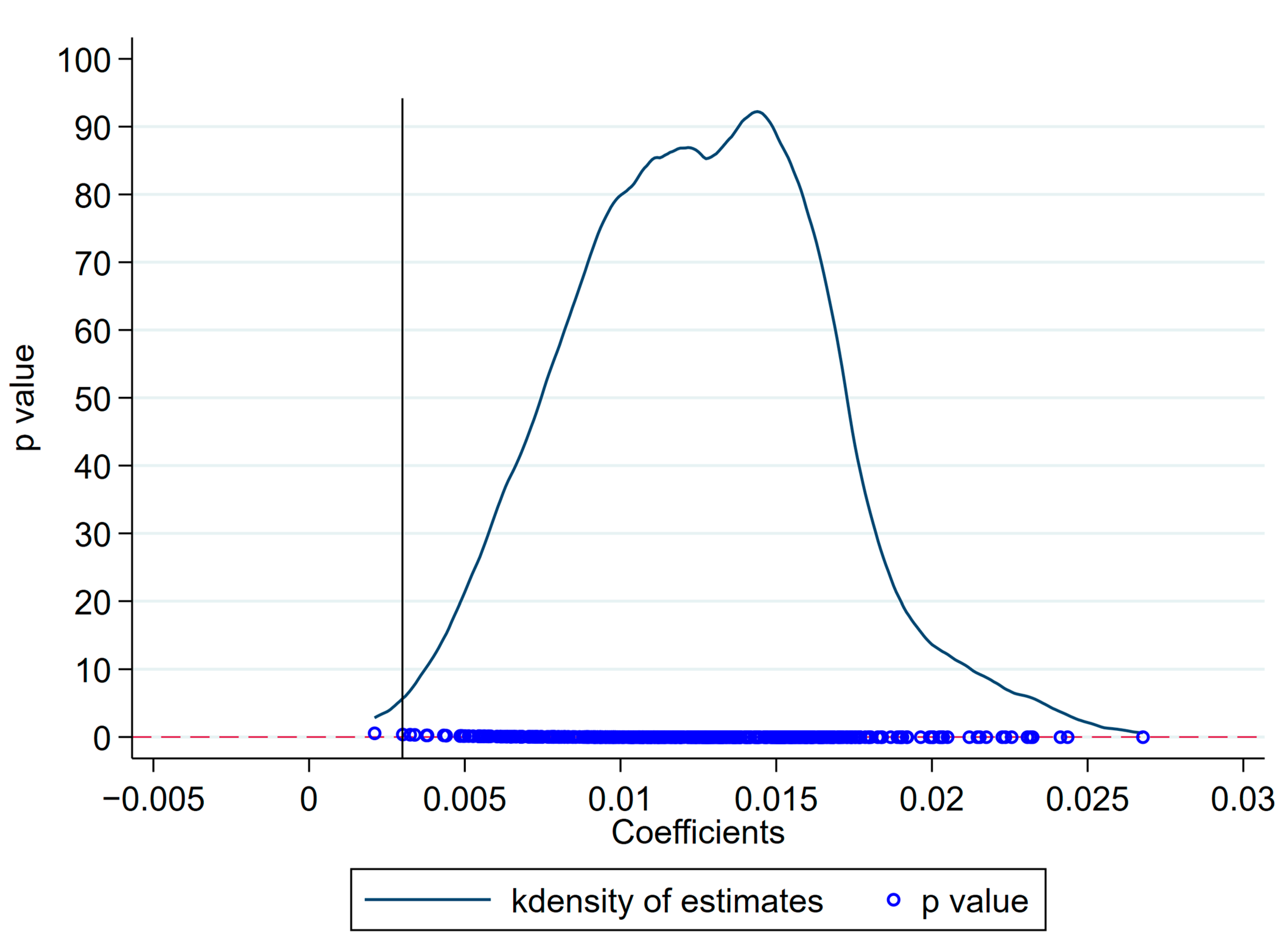

4.2. Robustness Test Analysis

4.3. Heterogeneity Analysis

5. Moderating Effects Analysis

6. Results and Discussion

6.1. Research Results

6.2. Research Results in Discussions

6.3. Conclusions

7. Theoretical Contributions and Policy Application

7.1. Theoretical Contributions

7.2. Managerial Implications, Limitations, and Future Research

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Dan, Y.; Xu, H.; Zhou, L.; Zhou, Q. Digital Empowerment: How Does Organizational Resilience Form in a Crisis Context?—An Exploratory Case Study of Lin Qingxuan’s Crisis Transformation. J. Manag. World 2021, 37, 84–104+107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lv, W.D.; Wei, Y.; Li, X.Y.; Lin, L. What Dimension of CSR Matters to Organizational Resilience? Evidence from China. Sustainability 2019, 11, 1561. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Linnenluecke, M.K. Resilience in Business and Management Research: A Review of Influential Publications and a Research Agenda. Int. J. Manag. Rev. 2017, 19, 4–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Annarelli, A.; Nonino, F. Strategic and Operational Management of Organizational Resilience: Current State of Research and Future Directions. Omega 2016, 62, 1–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xie, X.M.; Wu, Y.H.; Palacios-Marqués, D.; Ribeiro-Navarrete, S. Business Networks and Organizational Resilience Capacity in the Digital Age During COVID-19: A Perspective Utilizing Organizational Information Processing Theory. Technol. Forecast. Soc. Change 2022, 177, 121548. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, P.; Välikangas, L. Resilience, Resilience, Resilience. Manag. Organ. Rev. 2020, 16, 225–227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hillmann, J.; Guenther, E. Organizational Resilience: A Valuable Construct for Management Research? Int. J. Manag. Rev. 2021, 23, 7–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- DesJardine, M.; Bansal, P.; Yang, Y. Bouncing Back: Building Resilience Through Social and Environmental Practices in the Context of the 2008 Global Financial Crisis. J. Manag. 2019, 45, 1434–1460. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ortiz-de-Mandojana, N.; Bansal, P. The Long-Term Benefits of Organizational Resilience Through Sustainable Business Practices. Strateg. Manag. J. 2016, 37, 1615–1631. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- El Nayal, O.; Slangen, A.; van Oosterhout, J.; van Essen, M. Towards a Democratic New Normal? Investor Reactions to Interim-Regime Dominance During Violent Events. J. Manag. Stud. 2020, 57, 505–536. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, C.; Zuzul, T.; Jones, G.; Khanna, T. Overcoming Institutional Voids: A Reputation-Based View of Long-Run Survival. Strateg. Manag. J. 2017, 38, 2147–2167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grogaard, B.; Colman, H.L.; Stensaker, I.G. Legitimizing, Leveraging, and Launching: Developing Dynamic Capabilities in the MNE. J. Int. Bus. Stud. 2022, 53, 636–656. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.; Woywode, M. Light-Touch Integration of Chinese Cross-Border M&A: The Influences of Culture and Absorptive Capacity. Thunderbird Int. Bus. Rev. 2013, 55, 469–483. [Google Scholar]

- Chakrabarti, R.; Gupta-Mukherjee, S.; Jayaraman, N. Mars-Venus Marriages: Culture and Cross-Border M&A. J. Int. Bus. Stud. 2009, 40, 216–236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sinkovics, R.R.; Sinkovics, N.; Lew, Y.K.; Jedin, M.H.; Zagelmeyer, S. Antecedents of Marketing Integration in Cross-Border Mergers and Acquisitions: Evidence from Malaysia and Indonesia. Int. Mark. Rev. 2015, 32, 2–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, C.; Xie, J.; Wang, Q. Failure to Complete Cross-Border M&As: ‘To’ vs. ‘From’ Emerging Markets. J. Int. Bus. Stud. 2016, 47, 1077–1105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vahlne, J.E.; Hamberg, M.; Schweizer, R. Management Under Uncertainty–The Unavoidable Risk-Taking. Multinatl. Bus. Rev. 2017, 25, 91–109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hsu, C.C.; Park, J.Y.; Lew, Y.K. Resilience and Risks of Cross-Border Mergers and Acquisitions. Multinatl. Bus. Rev. 2019, 27, 427–450. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lebedev, S.; Peng, M.W.; Xie, E.; Stevens, C.E. Mergers and Acquisitions in and out of Emerging Economies. J. World Bus. 2015, 50, 651–662. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shao, X.J.; Wu, H.M.; Xiao, L.S.; Yang, J.; Xue, Y. Strategic Objectives and Operational Performance of Chinese Enterprises’ Cross-Border M&As: An Evaluation Based on the A-Share Market. J. World Econ. 2012, 35, 81–105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, H.Y.; He, R.Q.; Fu, Q. Does Corporate Social Responsibility Affect the Performance of Cross-border M&A of Emerging Market Multinationals? Financ. Res. Lett. 2023, 58, 104320. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heinz, D.; Hunke, F.; Breitschopf, G.F. Organizing for Digital Innovation and Transformation: Bridging Between Organizational Resilience and Innovation Management. In Proceedings of the 16th International Conference on Wirtschaftsinformatik (WI), Essen, Germany, 9–11 March 2021; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2021; pp. 548–564. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buyl, T.; Boone, C.; Wade, J.B. CEO Narcissism, Risk-Taking, and Resilience: An Empirical Analysis in U.S. Commercial Banks. J. Manag. 2019, 45, 1372–1400. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eisenhardt, K.M.; Martin, J.A. Dynamic Capabilities: What are They? Strateg. Manag. J. 2000, 21, 1105–1121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Staw, B.M.; Sandelands, L.E.; Dutton, J.E. Threat Rigidity Effects in Organizational Behavior: A Multilevel Analysis. Adm. Sci. Q. 1981, 26, 501–524. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meyer, A.D. Adapting to Environmental Jolts. Adm. Sci. Q. 1982, 27, 515–537. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ju, J. How Open Innovation Drives Intellectual Capital to Superior Organizational Resilience: Evidence from China’s ICT Sector. J. Intellect. Cap. 2023, 24, 1464–1484. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wiig, S.; Fahlbruch, B. Exploring Resilience: A Scientific Journey from Practice to Theory; Springer Nature: Cham, Switzerland, 2019; Volume 11. [Google Scholar]

- Williams, T.A.; Gruber, D.A.; Sutcliffe, K.M.; Shepherd, D.A.; Zhao, E.Y. Organizational Response to Adversity: Fusing Crisis Management and Resilience Research Streams. Acad. Manag. Ann. 2017, 11, 733–769. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duchek, S. Organizational Resilience: A Capability-Based Conceptualization. Bus. Res. 2020, 13, 215–246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bak, O.; Shaw, S.; Colicchia, C.; Kumar, V. A Systematic Literature Review of Supply Chain Resilience in Small-Medium Enterprises (SMEs): A Call for Further Research. IEEE Trans. Eng. Manag. 2020, 70, 328–341. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, Z.; Xiao, L.; Yin, J. Toward a Dynamic Model of Organizational Resilience. Nankai Bus. Rev. Int. 2018, 9, 246–263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sahebjamnia, N.; Torabi, S.A.; Mansouri, S.A. Building Organizational Resilience in the Face of Multiple Disruptions. Int. J. Prod. Econ. 2018, 197, 63–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sincorá, L.A.; de Oliveira, M.P.V.; Zanquetto-Filho, H.; Ladeira, M.B. Business Analytics Leveraging Resilience in Organizational Processes. RAUSP Manag. J. 2018, 53, 385–403. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gallopin, G. Linkages Between Vulnerability, Resilience, and Adaptive Capacity. Glob. Environ. Change 2006, 16, 293–303. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burnard, K.; Bhamra, R. Organisational Resilience: Development of a Conceptual Framework for Organisational Responses. Int. J. Prod. Res. 2011, 49, 5581–5599. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Patriarca, R.; Di Gravio, G.; Costantino, F. An Analytic Framework to Assess Organizational Resilience. Saf. Health Work 2018, 9, 265–276. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lin, J.; Fan, Y. Seeking Sustainable Performance through Organizational Resilience: Examining the Role of Supply Chain Integration and Digital Technology Usage. Technol. Forecast. Soc. Change 2024, 198, 123026. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y. Research on the Relationship Between Organizational Resilience, Strategic Capability, and the Growth of New Ventures. J. Univ. Chin. Acad. Soc. Sci. 2019, 1, 68–77. [Google Scholar]

- Kantur, D.; Say, A.I. Organizational Resilience: A Conceptual Integrative Framework. J. Manag. Organ. 2012, 18, 762–773. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, R.; Xu, L.B.; Ye, Q.Q.; Hai, T.T. Study on the Resilience Measurement and Influencing Factors of Chinese Private Enterprises. Bus. Manag. J. 2021, 43, 56–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kantur, D.; Say, A.I. Measuring Organizational Resilience: A Scale Development. J. Bus. Econ. Financ. 2015, 4, 456–472. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, S.F.; Xu, M.S.; Zhu, Y.; Wang, Z.Q. Technological Innovation, Organizational Resilience, and High-Quality Development of Manufacturing Enterprises. Sci. Technol. Prog. Policy 2023, 40, 81–92. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, J.Q.; Xu, Y.L. ESG Performance and Corporate Resilience. J. Audit. Econ. 2024, 1, 54–64. [Google Scholar]

- Hamel, G.; Valikangas, L. The Quest for Resilience. Harv. Bus. Rev. 2003, 81, 52–63. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Lengnick-Hall, C.A.; Beck, T.E.; Lengnick-Hall, M.L. Developing a Capacity for Organizational Resilience Through Strategic Human Resource Management. Hum. Resour. Manag. Rev. 2011, 21, 243–255. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shela, V.; Ramayah, T.; Hazlina, A.N. Human Capital and Organisational Resilience in the Context of Manufacturing: A Systematic Literature Review. J. Intellect. Cap. 2023, 24, 535–559. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vogus, T.J.; Sutcliffe, K.M. Organizational Resilience: Towards a Theory and Research Agenda. In Proceedings of the 2007 IEEE International Conference on Systems, Man and Cybernetics, Montreal, QC, Canada, 7–10 October 2007; pp. 3418–3422. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, H.H.; Kerstein, J.; Wang, C. The Impact of Climate Risk on Firm Performance and Financing Choices: An International Comparison. J. Int. Bus. Stud. 2018, 49, 633–656. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Williams, T.A.; Shepherd, D.A. Building Resilience or Providing Sustenance: Different Paths of Emergent Ventures in the Aftermath of the Haiti Earthquake. Acad. Manag. J. 2016, 59, 2069–2102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, G. The Impact and Difference of Cross-border and Domestic Mergers and Acquisitions on Corporate Market Value: Evidence from Chinese Enterprises. World Econ. Stud. 2020, 2020, 82–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Teece, D.; Pisano, G.; Shuen, A. Dynamic Capabilities and Strategic Management. Strateg. Manag. J. 1997, 18, 509–533. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, Q.C.; Liang, L.L.; Jia, F. How Strategic Learning Influences Organizational Innovation: A Perspective Based on Dynamic Capabilities. J. Manag. World 2018, 34, 109–129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Teece, D.J.; Leih, S. Uncertainty, Innovation, and Dynamic Capabilities: An Introduction. Calif. Manag. Rev. 2016, 58, 5–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xie, K.; Wu, Y.; Xiao, J.H.; Liao, X.H. Strategic Risk Control in Organizational Change: A Multi-Case Study Based on Corporate Internet Transformation. J. Manag. World 2016, 2016, 133–148+188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Teece, D.J. Explicating Dynamic Capabilities: The Nature and Microfoundations of (Sustainable) Enterprise Performance. Strateg. Manag. J. 2007, 28, 1319–1350. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiao, H.; Wei, J.; Cui, Y. Analysis of the Pathways for Building Corporate Dynamic Capabilities: A Perspective Based on Entrepreneurial Orientation and Organizational Learning. J. Manag. World 2008, 2008, 91–106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, B.; Wang, F.B.; Qin, Y. How Do Dynamic Capabilities Affect Organizational Routines? A Comparative Study of Two Cases. J. Manag. World 2013, 8, 136–153+188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, C.L.; Ahmed, P.K. Dynamic Capabilities: A Review and Research Agenda. Int. J. Manag. Rev. 2007, 9, 31–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, X.Y.; Mao, J.Y. Construction of Dynamic Capabilities: A Multi-Case Study Based on Offshore Software Outsourcing Suppliers. J. Manag. Sci. China 2010, 11, 55–64+120. [Google Scholar]

- Barreto, I. Dynamic Capabilities: A Review of Past Research and an Agenda for the Future. J. Manag. 2010, 36, 256–280. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arthurs, J.D.; Busenitz, L.W. Dynamic Capabilities and Venture Performance: The Effects of Venture Capitalists. J. Bus. Ventur. 2006, 21, 195–215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Helfat, C.E. Know-how and Asset Complementarity and Dynamic Capability Accumulation: The Case of R&D. Strateg. Manag. J. 1997, 18, 339–360. [Google Scholar]

- Distel, A.P.; Sofka, W.; de Faria, P.; Preto, M.T.; Ribeiro, A.S. Dynamic Capabilities for Hire-How Former Host-country Entrepreneurs as MNC Subsidiary Managers Affect Performance. J. Int. Bus. Stud. 2019, 53, 657–688. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deeds, D.L.; DeCarolis, D.; Coombs, J. Dynamic Capabilities and New Product Development in High Technology Ventures: An Empirical Analysis of New Biotechnology Firms. J. Bus. Ventur. 2000, 15, 211–229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Doving, E.; Gooderham, P.N. Dynamic Capabilities as Antecedents of the Scope of Related Diversification: The Case of Small Firm Accountancy Practices. Strateg. Manag. J. 2008, 29, 841–857. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sirmon, D.G.; Hitt, M.A. Contingencies Within Dynamic Managerial Capabilities: Interdependent Effects of Resource Investment and Deployment on Firm Performance. Strateg. Manag. J. 2009, 30, 1375–1394. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Madhok, A.; Osegowitsch, T. The International Biotechnology Industry: A Dynamic Capabilities Perspective. J. Int. Bus. Stud. 2000, 31, 325–335. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lim, J.H.; Stratopoulos, T.C.; Wirjanto, T.S. Path Dependence of Dynamic Information Technology Capability: An Empirical Investigation. J. Manag. Inf. Syst. 2011, 28, 45–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coen, C.A.; Maritan, C.A. Investing in Capabilities: The Dynamics of Resource Allocation. Organ. Sci. 2011, 22, 99–117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fang, E.; Zou, S. Antecedents and Consequences of Marketing Dynamic Capabilities in International Joint Ventures. J. Int. Bus. Stud. 2009, 40, 742–761. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Canhoto, A.I.; Quinton, S.; Pera, R.; Molinillo, S.; Simkin, L. Digital Strategy Aligning in SMEs: A Dynamic Capabilities Perspective. J. Strateg. Inf. Syst. 2021, 30, 101682. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hsu, L.C.; Wang, C.H. Clarifying the Effect of Intellectual Capital on Performance: The Mediating Role of Dynamic Capability. Br. J. Manag. 2012, 23, 179–205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chakrabarty, S.; Wang, L. The Long-Term Sustenance of Sustainability Practices in MNCs: A Dynamic Capabilities Perspective of the Role of R&D and Internationalization. J. Bus. Ethics 2012, 110, 205–217. [Google Scholar]

- Arikan, I.; Koparan, I.; Arikan, A.M.; Shenkar, O. Dynamic Capabilities and Internationalization of Authentic Firms: Role of Heritage Assets, Administrative Heritage, and Signature Processes. J. Int. Bus. Stud. 2019, 53, 601–635. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sapienza, H.J.; Autio, E.; George, G.; Zahra, S.A. A Capabilities Perspective on the Effects of Early Internationalization on Firm Survival and Growth. Acad. Manag. Rev. 2006, 31, 914–933. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, J.W.; Beamish, P.W. International Diversification and Firm Performance: The S-curve Hypothesis. Acad. Manag. J. 2004, 47, 598–609. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, L.; He, X.; Gu, H.F. Top Management Team Experience, Dynamic Capabilities, and Corporate Strategic Transformation: The Moderating Effect of Managerial Discretion. J. Manag. World 2020, 36, 168–188+201+252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weerawardena, J.; Mort, G.S.; Salunke, S.; Knight, G.; Liesch, P.W. The Role of the Market Sub-system and the Socio-technical Sub-system in Innovation and Firm Performance: A Dynamic Capabilities Approach. J. Acad. Mark. Sci. 2015, 43, 221–239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hitt, M.A.; Ireland, R.D.; Harrison, J.S. Mergers and Acquisitions: A Guide to Creating Value for Stakeholders; Oxford University Press: Oxford, UK, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Erel, I.; Liao, R.; Weisbach, M.S. Determinants of Cross-border Mergers and Acquisitions. J. Financ. 2012, 67, 1045–1082. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bris, A.; Cabolis, C. The Value of Investor Protection: Firm Evidence from Cross-border Mergers. Rev. Financ. Stud. 2008, 21, 605–648. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deli, Y.; Xu, D. Cross-border Mergers and Acquisitions by Emerging Market Firms: A Comparative Investigation. Int. Bus. Rev. 2017, 26, 57–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blyler, M.; Coff, R.W. Dynamic Capabilities, Social Capital, and Rent Appropriation: Ties That Split Pies. Strateg. Manag. J. 2003, 24, 677–686. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Teece, D.J. Dynamic Capabilities: Routines versus Entrepreneurial Action. J. Manag. Stud. 2012, 49, 1395–1401. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eckbo, E.B.; Thorburn, K.S. Gains to Bidders Revisited: Domestic and Foreign Acquisitions in Canada. J. Financ. Quant. Anal. 2000, 35, 1–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stadler, C.; Helfat, C.E.; Verona, G. The Impact of Dynamic Capabilities on Resource Access and Development. Organ. Sci. 2013, 24, 1782–1804. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fainshmidt, S.; Wenger, L.; Pezeshkan, A.; Mallon, M.R. When do Dynamic Capabilities Lead to Competitive Advantage? The Importance of Strategic Fit. J. Manag. Stud. 2019, 56, 758–787. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Makadok, R. Toward a Synthesis of the Resource-based And Dynamic-capability Views of Rent Creation. Strateg. Manag. J. 2001, 22, 387–401. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martin, J.A. Dynamic Managerial Capabilities and the Multibusiness Team: The Role of Episodic Teams in Executive Leadership Groups. Organ. Sci. 2011, 22, 118–140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zahra, S.A.; Sapienza, H.J.; Davidsson, P. Entrepreneurship and Dynamic Capabilities: A Review, Model and Research Agenda. J. Manag. Stud. 2006, 43, 917–955. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiao, H.; Yang, J.F.; Ying, Y. A Review of Dynamic Capabilities Research and Suggestions for Conducting Contextualized Research in China. J. Manag. World 2021, 37, 191–210+214+222–224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Omoush, K.; Ribeiro-Navarrete, B.; McDowell, W.C. The Impact of Digital Corporate Social Responsibility on Social Entrepreneurship and Organizational Resilience. Manag. Decis. 2023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dabic, M.; Colovic, A.; Lamotte, O.; Painter-Morland, M.; Brozovic, S. Industry-specific CSR: Analysis of 20 Years of Research. Eur. Bus. Rev. 2016, 28, 250–273. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sajko, M.; Boone, C.; Buyl, T. CEO Greed, Corporate Social Responsibility, and Organizational Resilience to Systemic Shocks. J. Manag. 2021, 47, 957–992. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, W.; Chen, S.; Nguyen, L.T. Corporate Social Responsibility and Organizational Resilience to COVID-19 Crisis: An Empirical Study of Chinese Firms. Sustainability 2020, 12, 8970. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramachandran, V. Strategic Corporate Social Responsibility: A ‘Dynamic Capabilities’ Perspective. Corp. Soc. Responsib. Environ. Manag. 2011, 18, 285–293. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chao, G.; Cheng, P.; Zhang, S.Y. An Empirical Study on the Impact of Corporate Social Responsibility on Employee Engagement from the Employee Perspective. Chin. J. Manag. 2012, 6, 831–836. [Google Scholar]

- Wisse, B.; van Eijbergen, R.; Rietzschel, E.F.; Scheibe, S. Catering to the Needs of an Aging Workforce: The Role of Employee Age in the Relationship Between Corporate Social Responsibility and Employee Satisfaction. J. Bus. Ethics 2018, 147, 875–888. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bocquet, R.; Le Bas, C.; Mothe, C.; Poussing, N. CSR, Innovation, and Firm Performance in Sluggish Growth Contexts: A Firm-level Empirical Analysis. J. Bus. Ethics 2017, 146, 241–254. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, H.; Tong, L.; Takeuchi, R.; George, G. Corporate Social Responsibility: An Overview and New Research Directions: Thematic Issue on Corporate Social Responsibility. Acad. Manag. J. 2016, 59, 534–544. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.; Yin, J. Stakeholder Relationships and Organizational Resilience. Manag. Organ. Rev. 2020, 16, 986–990. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chan, M.C.; Watson, J.; Woodliff, D. Corporate Governance Quality and CSR Disclosures. J. Bus. Ethics 2014, 125, 59–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nickel, M.N.; Rodriguez, M.C. A Review of Research on the Negative Accounting Relationship Between Risk and Return: Bowman’s Paradox. Omega 2002, 30, 1–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cui, J.; Jo, H.; Na, H. Does Corporate Social Responsibility Affect Information Asymmetry? J. Bus. Ethics 2018, 148, 549–572. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pal, R.; Torstensson, H.; Mattila, H. Antecedents of Organizational Resilience in Economic Crises: An Empirical Study of Swedish Textile and Clothing SMEs. Int. J. Prod. Econ. 2014, 147, 410–428. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hahn, R.W. Market Power and Transferable Property Rights. Q. J. Econ. 1984, 99, 753–765. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Datta, S.; Iskander-Datta, M.; Sharma, V. Product Market Pricing Power, Industry Concentration, and Analysts’ Earnings Forecasts. J. Bank. Financ. 2011, 35, 1352–1366. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, W.; Zhang, Y. Does China’s Carbon Emissions Trading Scheme Affect the Market Power of High-Carbon Enterprises? Energy Econ. 2022, 108, 105906. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Corts, K.S. Conduct Parameters and the Measurement of Market Power. J. Econ. 1999, 88, 227–250. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, Y.; Li, C. Digital Transformation, Firm Boundaries, and Market Power: Evidence from China’s Listed Companies. Systems 2023, 11, 479. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Graebner, M.E.; Heimeriks, K.H.; Huy, Q.N.; Vaara, E. The Process of Postmerger Integration: A Review and Agenda for Future Research. Acad. Manag. Ann. 2017, 11, 1–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Porter, M.E. Competitive Advantage; Free Press: New York, NY, USA, 1985. [Google Scholar]

- Peress, J. Product Market Competition, Insider Trading and Stock Market Efficiency. J. Financ. 2010, 65, 1–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ornaghi, C. Positive Assortive Merging. J. Econ. Manag. Strategy 2009, 18, 323–346. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stiebale, J. Cross-border M&A and Innovative Activity of Acquiring and Target Firms. J. Int. Econ. 2016, 99, 1–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heckman, J.; Ichimura, H.; Todd, P. Matching as an Econometric Evaluation Estimator: Evidence from Evaluating a Job Training Programme. Rev. Econ. Stud. 1997, 64, 605–654. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rosenbaum, P.R.; Rubin, D.B. The Central Role of the Propensity Score in Observational Studies for Causal Effects. Biometrika 1983, 70, 41–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Caliendo, M.; Kopeinig, S. Some Practical Guidance for the Implementation of Propensity Score Matching. J. Econ. Surv. 2008, 22, 31–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- John, K.; Litov, L.; Yeung, B. Corporate Governance and Risk-Taking. J. Financ. 2008, 63, 1679–1728. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guadalupe, M.; Kuzmina, O.; Thomas, C. Innovation and Foreign Ownership. Am. Econ. Rev. 2012, 102, 3594–3627. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, F.Q.; Lü, Y.T. Can Cross-border M&As Drive Corporate Innovation? A Theoretical and Empirical Study Based on Technological and Resource Complementarity. World Econ. Stud. 2022, 2022, 102–117+137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hawn, O. How Media Coverage of Corporate Social Responsibility and Irresponsible Influences Cross-border Acquisitions. Strateg. Manag. J. 2021, 42, 58–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Limnios, E.A.M.; Mazzarol, T.; Ghadouani, A. The Resilience Architecture Framework: Four Organizational Archetypes. Eur. Manag. J. 2014, 32, 104–116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ruiz-Martin, C.; Lopez-Paredes, A.; Wainer, G.A. What We Know and Do Not Know About Organizational Resilience. Int. J. Prod. Manag. Eng. 2018, 6, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gu, L.; Reed, R. Have Chinese Enterprises Failed in Overseas Mergers and Acquisitions? Econ. Res. J. 2011, 7, 116–129. [Google Scholar]

| Variables | Definition | Data Source |

|---|---|---|

| Dependent Variables | ||

| Resilience | Following standardisation, corporate organisational resilience is calculated by subtracting risk-taking and short-term financial volatility from the long-term growth figure. | CSMAR |

| Risk | The firm’s risk-taking, calculated from the three-year rolling standard deviation of the adjusted ROA | CSMAR |

| Growth | The long-term growth level of the enterprise is measured by the cumulative value of the enterprise’s three-year net sales growth | CSMAR |

| Volatility | The short-term financial volatility is measured by the standard deviations of monthly stock returns in each year. | CSMAR |

| Moderator | ||

| CSR | Corporate social responsibility is measured using Hexun’s corporate social responsibility score/100 | Hexun |

| Lerner | Firm market power is measured by the Lerner index | CSMAR |

| Control Variables | ||

| FirmAge | Age of enterprise, based on the date of establishment | CSMAR |

| Profits | Total profit of enterprise | CSMAR |

| ROA | Net profit rate on total assets | CSMAR |

| Lev | Asset-liability ratio | CSMAR |

| Mshare | Management shareholding ratio | CSMAR |

| TobinQ | Tobin’s Q | CSMAR |

| M&As Enterprises | Non-M&A Enterprises | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| N | Mean | SD | N | Mean | SD | |

| Resilience | 4240 | 0.003 | 0.599 | 19,650 | −0.032 | 0.473 |

| Risk | 4572 | 0.001 | 1.003 | 21,354 | −0.000 | 0.999 |

| Growth | 4656 | 0.131 | 1.435 | 25,665 | −0.0237 | 0.897 |

| Volatility | 4643 | −0.055 | 0.788 | 25,199 | 0.010 | 1.034 |

| CSR | 4771 | 0.240 | 0.161 | 24,437 | 0.237 | 0.151 |

| Lerner | 5004 | 0.0679 | 0.440 | 4771 | 0.240 | 0.161 |

| FirmAge * | 5004 | 2.868 | 0.345 | 27,744 | 2.791 | 0.390 |

| Profits * | 5004 | 1.414 × 109 | 6.441 × 109 | 27,744 | 5.293 × 108 | 3.707 × 109 |

| ROA * | 5004 | 0.038 | 0.072 | 27,744 | 0.045 | 0.064 |

| Lev * | 5004 | 0.467 | 0.196 | 27,744 | 0.417 | 0.209 |

| Mshare * | 4888 | 0.127 | 0.184 | 26,795 | 0.140 | 0.207 |

| TobinQ * | 4909 | 1.964 | 1.341 | 27,253 | 2.040 | 1.363 |

| (1) | (2) | (3) | (4) | (5) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Variables | Resilience | Resilience | Growth | Volatility | Risk |

| Model | Time-Varying DID | Time-Varying DID | Time-Varying DID | Time-Varying DID | Time-Varying DID |

| treat | 0.059 *** | 0.016 *** | 0.064 *** | 0.056 ** | 0.030 *** |

| (2.63) | (3.08) | (2.63) | (1.99) | (3.04) | |

| FirmAge | −0.032 | 0.193 *** | 0.110 | −0.065 | |

| (−0.64) | (3.15) | (1.53) | (−0.68) | ||

| Profits | 0.000 *** | 0.000 *** | −0.000 | −0.000 | |

| (38.41) | (58.08) | (−0.80) | (−0.08) | ||

| ROA | −2.060 *** | −0.422 *** | 0.418 *** | −5.807 *** | |

| (−34.28) | (−4.03) | (3.47) | (−52.91) | ||

| Lev | 0.138 *** | 0.239 *** | 0.126 ** | −0.140 ** | |

| (4.48) | (4.80) | (2.19) | (−2.47) | ||

| Mshare | −0.101 ** | −0.061 | 0.209 *** | −0.257 *** | |

| (−2.31) | (−0.90) | (2.64) | (−3.13) | ||

| TobinQ | 0.061 *** | 0.000 | 0.092 *** | 0.076 *** | |

| (19.45) | (0.05) | (14.94) | (13.20) | ||

| Constant | 0.014 | −0.016 | −0.622 *** | −0.428 ** | 0.355 |

| (0.88) | (−0.13) | (−4.33) | (−2.55) | (1.49) | |

| Observations | 23,890 | 23,102 | 29,327 | 28,859 | 24,573 |

| R-squared | 0.005 | 0.125 | 0.122 | 0.021 | 0.134 |

| Number of stkcd | 3211 | 3203 | 3778 | 3704 | 3397 |

| Firm FE | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y |

| Year FE | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y |

| Control variables | N | Y | Y | Y | Y |

| (1) | (2) | (3) | (4) | (5) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Dependent Variable | Resilience | Resilience | Growth | Volatility | Risk |

| Model | Time-Varying DID | Time-Varying DID | Time-Varying DID | Time-Varying DID | Time-Varying DID |

| treat | 0.008 *** | 0.003 ** | 42.028 *** | 0.002 | 0.089 *** |

| (2.60) | (2.22) | (3.98) | (0.55) | (3.08) | |

| FirmAge | 0.039 *** | 116.230 *** | 0.010 | 0.127 | |

| (5.07) | (4.38) | (1.04) | (0.43) | ||

| Profits | 0.000 | 0.000 *** | 0.000 | −0.000 | |

| (0.55) | (52.64) | (0.27) | (−0.66) | ||

| ROA | −0.105 *** | −180.131 *** | 0.079 *** | −22.429 *** | |

| (−8.02) | (−3.99) | (5.03) | (−66.14) | ||

| Lev | 0.021 *** | 93.283 *** | 0.009 | −0.356 ** | |

| (3.42) | (4.33) | (1.16) | (−2.03) | ||

| Mshare | −0.031 *** | −30.145 | 0.024 ** | −1.385 *** | |

| (−3.65) | (−1.02) | (2.29) | (−5.47) | ||

| TobinQ | 0.005 *** | 1.388 | 0.011 *** | 0.251 *** | |

| (6.98) | (0.60) | (13.01) | (14.16) | ||

| Constant | 0.753 *** | 0.658 *** | −314.129 *** | 0.166 *** | 3.330 *** |

| (225.93) | (36.62) | (−5.06) | (7.56) | (4.51) | |

| Observations | 30,322 | 29,328 | 29,327 | 28,859 | 24,573 |

| R-squared | 0.451 | 0.447 | 0.105 | 0.138 | 0.237 |

| Number of stkcd | 3787 | 3778 | 3778 | 3704 | 3397 |

| Firm FE | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y |

| Year FE | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y |

| Control variables | N | Y | Y | Y | Y |

| (1) | (2) | (3) | (4) | (5) | (6) | (7) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Dependent Variable | Resilience | ||||||

| Model | Time-Varying DID | ||||||

| Heterogeneity | Ownership | Industry | Region | ||||

| State | Private | Manufacturing | Non-Manufacturing | Eastern | Central | Western | |

| treat | 0.001 *** | −0.003 ** | 0.002 ** | 0.004 * | 0.002 *** | 0.001 * | 0.009 |

| (2.64) | (−2.01) | (1.99) | (1.78) | (4.48) | (1.86) | (0.83) | |

| Constant | 0.677 *** | 0.693 *** | 0.654 *** | 0.659 *** | 0.662 *** | 0.616 *** | 0.652 *** |

| (16.42) | (17.78) | (17.73) | (16.51) | (20.80) | (8.55) | (9.09) | |

| Observations | 11,073 | 15,992 | 19,361 | 9967 | 20,655 | 4706 | 3946 |

| R-squared | 0.719 | 0.302 | 0.408 | 0.520 | 0.408 | 0.568 | 0.534 |

| Firm FE | 1225 | 2555 | 2716 | 1337 | 2773 | 572 | 471 |

| Year FE | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y |

| Control variables | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y |

| (1) | (2) | (3) | (4) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Dependent Variable | Resilience | Resilience | Resilience | Resilience |

| CSR × treat | 0.029 *** | 0.034 *** | ||

| (4.41) | (4.78) | |||

| CSR | 0.010 ** | 0.030 *** | ||

| (2.50) | (7.01) | |||

| treat | 0.001 | −0.005 | 0.007 ** | 0.002 |

| (0.27) | (−1.14) | (2.10) | (0.60) | |

| lerner × treat | 0.006 * | 0.009 ** | ||

| (1.87) | (2.42) | |||

| lerner | −0.001 | 0.003 ** | ||

| (−1.38) | (2.32) | |||

| Constant | 0.825 *** | 0.758 *** | 0.753 *** | 0.660 *** |

| (186.35) | (21.96) | (183.46) | (36.71) | |

| Observations | 27,077 | 26,301 | 30,322 | 29,328 |

| R-squared | 0.213 | 0.220 | 0.451 | 0.447 |

| Number of stkcd | 3731 | 3722 | 3787 | 3778 |

| Firm FE | Y | Y | Y | Y |

| Year FE | Y | Y | Y | Y |

| Control variables | N | Y | N | Y |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Huang, X.; Yang, H.; Yang, P. The Impact of Cross-Border Mergers and Acquisitions on Corporate Organisational Resilience: Insights from Dynamic Capability Theory. Sustainability 2024, 16, 2242. https://doi.org/10.3390/su16062242

Huang X, Yang H, Yang P. The Impact of Cross-Border Mergers and Acquisitions on Corporate Organisational Resilience: Insights from Dynamic Capability Theory. Sustainability. 2024; 16(6):2242. https://doi.org/10.3390/su16062242

Chicago/Turabian StyleHuang, Xin, Huitong Yang, and Peijin Yang. 2024. "The Impact of Cross-Border Mergers and Acquisitions on Corporate Organisational Resilience: Insights from Dynamic Capability Theory" Sustainability 16, no. 6: 2242. https://doi.org/10.3390/su16062242

APA StyleHuang, X., Yang, H., & Yang, P. (2024). The Impact of Cross-Border Mergers and Acquisitions on Corporate Organisational Resilience: Insights from Dynamic Capability Theory. Sustainability, 16(6), 2242. https://doi.org/10.3390/su16062242