Abstract

The health experience is a crucial component of the customer experience that must not be overlooked. The sustainable development of the hospitality industry is affected by consumers’ health experiences in many aspects. As a part of the hospitality industry, the hotel industry should pay attention to consumers’ health experiences. This study uses a systematic review methodology and concept-based content analysis. The basic review section analyses the overall research trends from the perspectives of publishing time, publication channels, research themes, theoretical foundation, and research methodologies. The theme analysis section identifies three source themes that influence the health of hotel consumers: (1) hotels, (2) consumers themselves, and (3) special events. Based on the conclusions of the studies in the data set, the relationship between these three types of sources of influence and consumers’ health is analysed and discussed in combination with social cognitive theory. Then, two multidimensional frameworks are developed based on these source categories. The frameworks can be used to explain source categories and impact processes, as well as the relationship between impact sources and different health categories. Based on the existing research in the data set, nine valuable research questions are proposed for other researchers’ reference.

1. Introduction

The phenomenon of the experience economy has already pervaded several aspects of daily life and has steadily infiltrated diverse domains [1]. Pine and Gilmore [1] pointed out that the experience economy emerged after the service economy, and the main measurement criterion for products in the service economy is “delivery-focused”. The experience economy extends the standard for measuring product value from the customer’s perspective in both directions. That is, it expands the breadth of time for a product to realise its value and the depth of its meaning [2].

Consumer experience refers to the spontaneous reaction of consumers after being stimulated by products [3]. As the industry changes over time, new perspectives continue to emerge [4]. As the concept of experience continues to be segmented, research on consumer experience has shown a highly personalised development trend [4]. However, the growth of segmentation research has not only resulted in fragmented concepts and research perspectives [3] but also resulted in the neglect of consumers’ basic experiences.

Peppers and Rogers [5] pointed out that responding to consumers’ basic needs is a key element in consumer experience management. This perspective has been clearly illustrated in some incidents that have occurred in recent years. For example, during the COVID-19 period, the health experiences of hotel consumers were recognised as an important factor in their overall experiences [6].

Understanding and improving the health experiences of hotel consumers is not only beneficial to the customers but also to the sustainable development of the hotel industry. Firstly, from the perspective of sustainable industrial economic development, satisfying consumers’ health experiences can promote industrial economic development by influencing consumer loyalty and satisfaction [7], which, in turn, is conducive to the formation of an ecosystem in the hotel industry driven by health awareness. Furthermore, industry managers should realize that health-related issues are not only relevant to the industry but also closely related to the sustainable development of humankind. Among the 17 Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) proposed by the United Nations, human health ranks third [8].

However, previous studies have not paid much attention to the health experiences of hotel consumers, and most information relating to health experiences has been presented in a fragmented way. Therefore, this study aims to refine and summarise the fragmented factors from previous studies that affect hotel consumers’ health experiences, with a view to contributing to sustainable development in the hotel industry and globally.

2. Methodology

This study improved the rigour of its procedures by using a “systematic quantitative approach” to guide all of the study’s procedures, as suggested by Pickering and Byrn [9]. This method has been adopted by papers published in high-quality journals, including but not limited to top journals in the tourism and hotel management categories [10,11].

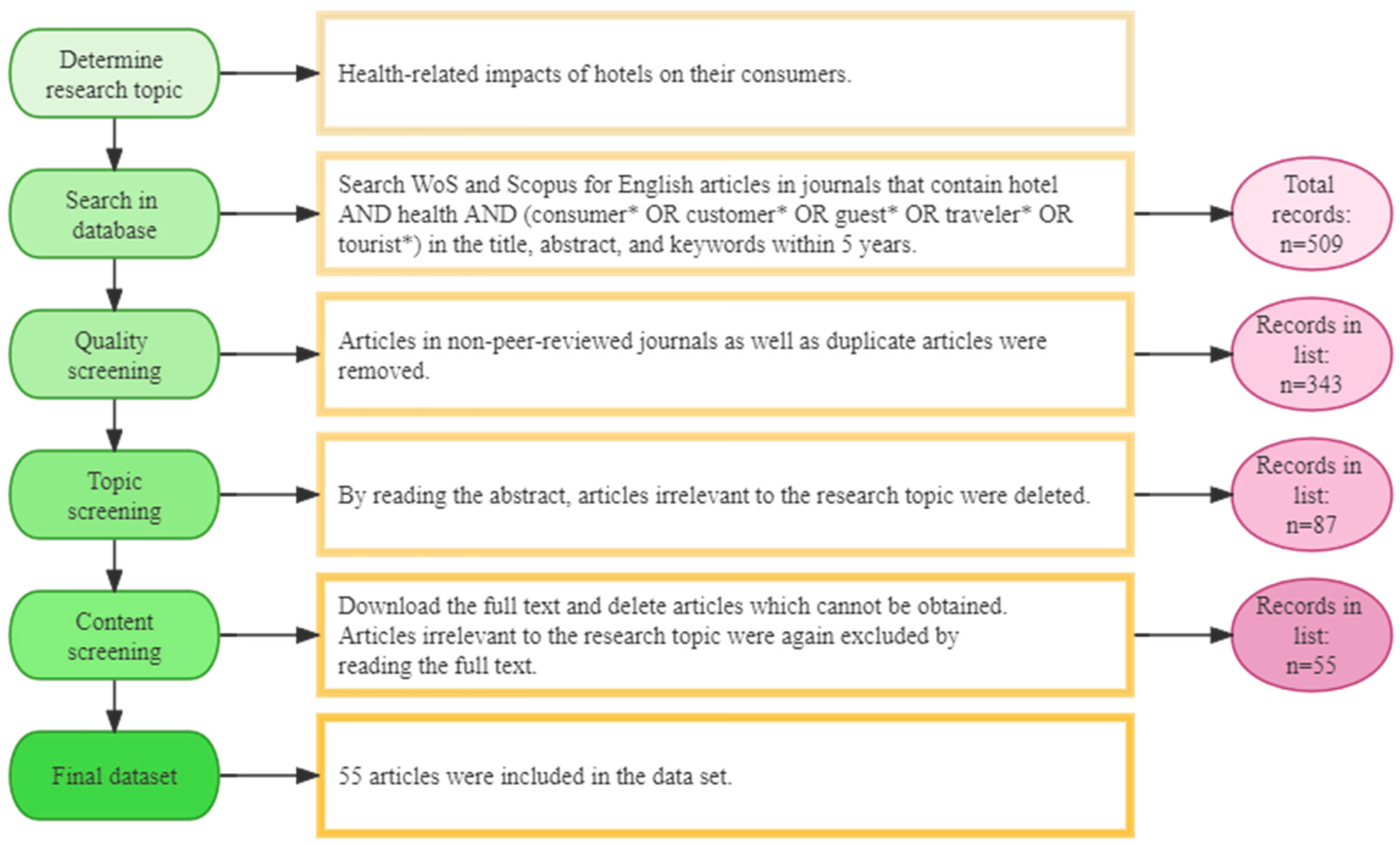

In order to minimise the amount of literature missed during the search process, this study’s search scope extended beyond titles and keywords to encompass abstracts. The principle of setting keywords for searches means including vocabulary related to research background, research objects, and research topics. The research background is strictly limited to hotels. The research object is hotel consumers (consumer* OR customer* OR guest* OR traveller* OR tourist*), and the research topic is health. The primary database chosen for this study was the Web of Science (WoS) and Scopus. The WoS and Scopus are the main databases commonly used for literature searches in the social sciences, and they cover high-quality journals in the field of hotel management [11,12]. This study only searched for English papers published in journals since 2019. The literature search was conducted on 31 October 2023, and 263 articles were obtained from the WoS and 245 articles from Scopus. After screening and reading, 55 articles that met the requirements of this study were finally included in the data set. Figure 1 shows each step of forming the final data set and the number of articles remaining at each step.

Figure 1.

Literature selection process. Note: The symbol “*” represents a wildcard or fuzzy search. For example, in the case of “traveler*”, the “*” means that the search not only include “traveler” but also includes “traveller”, “travellers” or “travelers”.

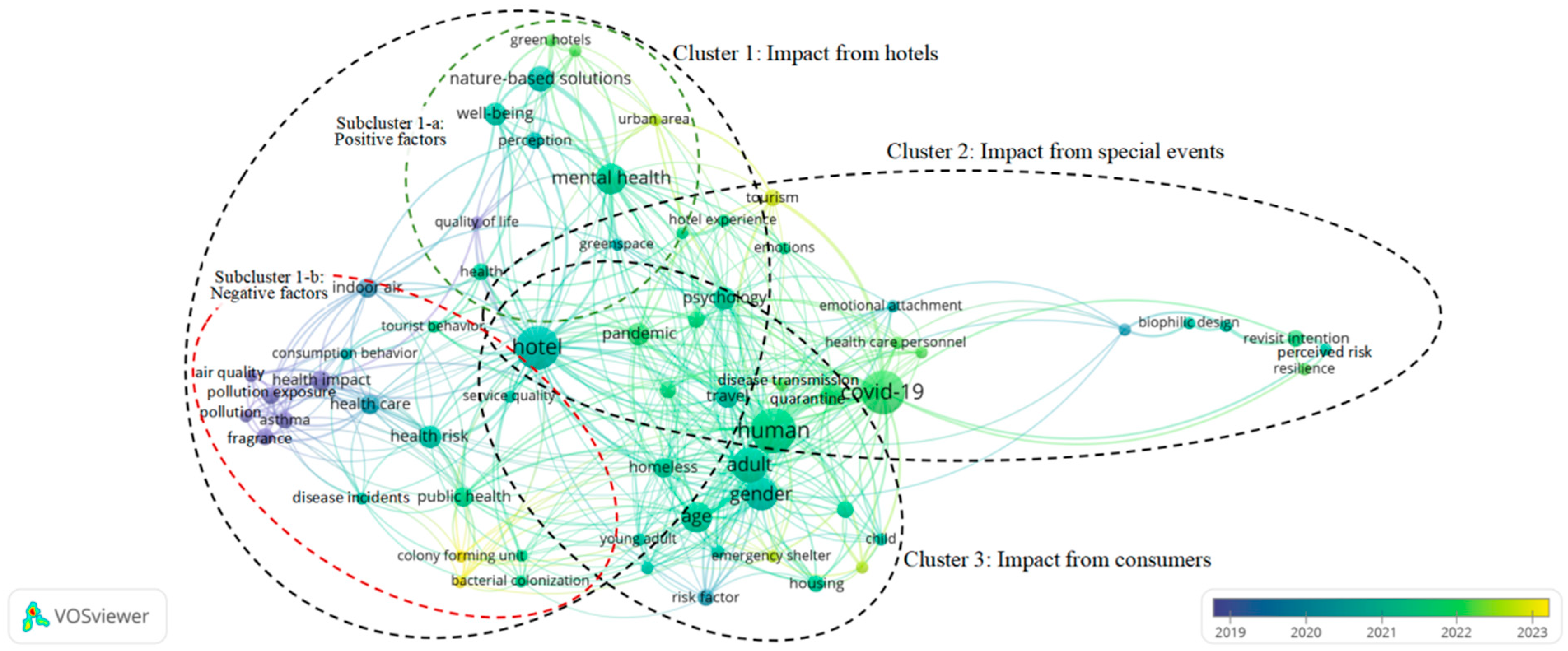

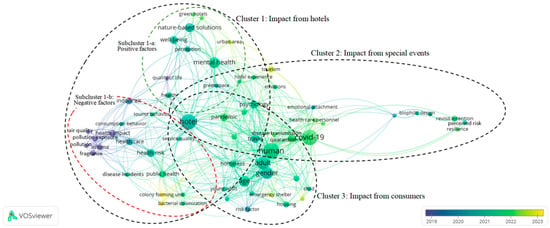

This study refers to the literature analysis process of Li et al. [11] and analyses articles in stages through two research methods. The first step is to present the current state of research on this topic using descriptive analysis within a quantitative research approach. Vosviewer was used as a tool to conduct keyword co-occurrence analysis. This method has been applied in some high-quality systematic literature review studies in the field of tourism and hotel management [4,11]. In total, 519 keywords were extracted from these 55 articles, and there were 67 keywords with a minimum occurrence of 2 times. This study performed a comparison between the cluster map of unfiltered keywords and the cluster map after filtering. Theme identification was then conducted based on the result of the comparison and the cluster recommendations provided by the software. Three themes were obtained, as shown in Figure 2. In addition, the researchers identified two sub-clusters based on the keywords under the theme of cluster 1.

Figure 2.

Keyword co-occurrence and cluster distribution.

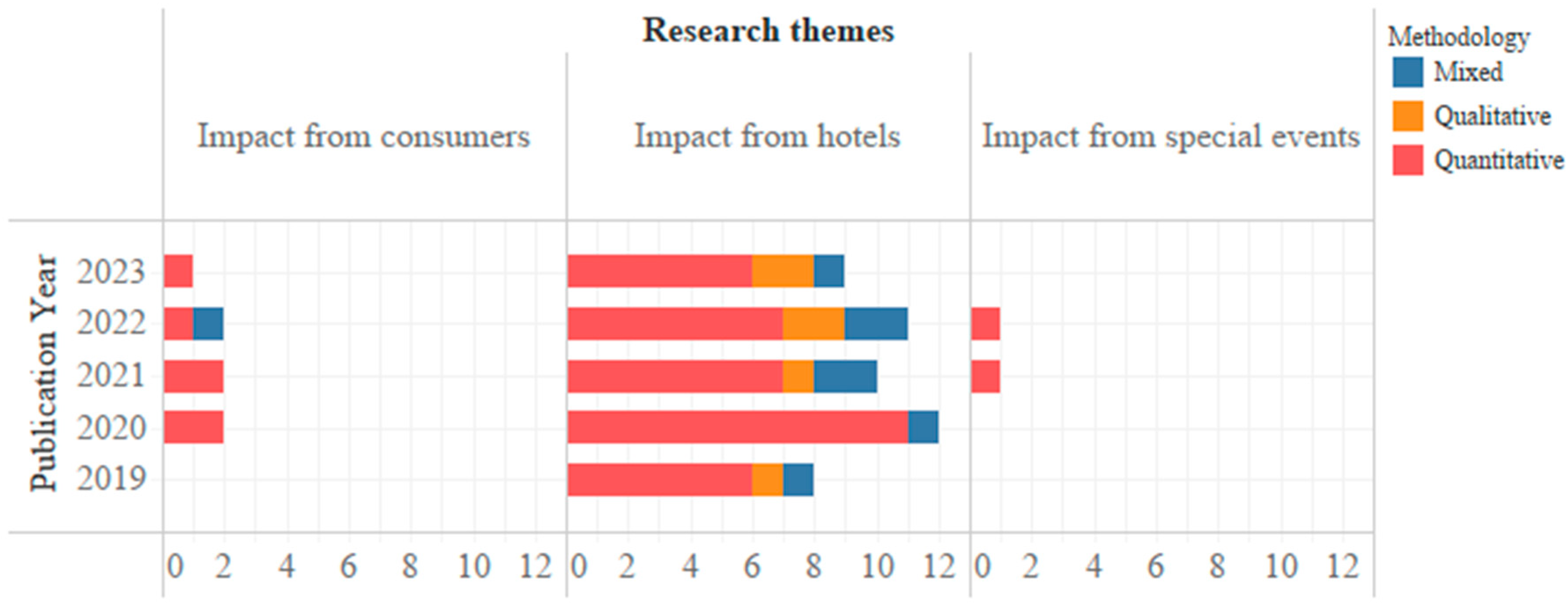

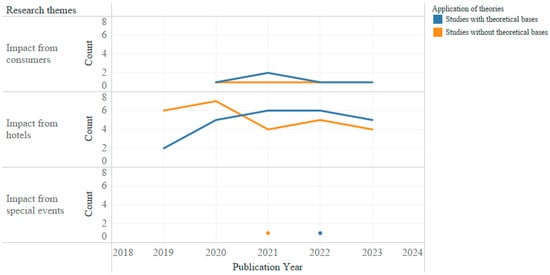

Following the topic analysis process of Le et al. [10] and Li et al. [11], this study clustered the articles to distinguish the research progress of each theme over time more clearly. First, the researchers discussed the types of articles that each cluster should cover based on the keyword co-occurrence results. The articles were then thematically categorised by two researchers. The topic classification process consisted of 5 rounds. Two researchers were required to compare the classification results after each round. If researchers disagreed on the categorisation of an article and could not agree after discussion, another researcher needed to be consulted to ensure that a consensus was ultimately reached. The classification results were imported into Tableau and used to generate Figure 3. It should be noted that four studies were labelled as having two themes at the same time, so the total number of studies shown in Figure 3 and Figure 4 is 59. This study adopted a concept-driven thematic analysis approach. Compared with other thematic analysis methods, this method can more clearly show the development of the research topic and is conducive to the construction of the researcher’s conceptual framework [11].

Figure 3.

Methodological evolution across themes over time.

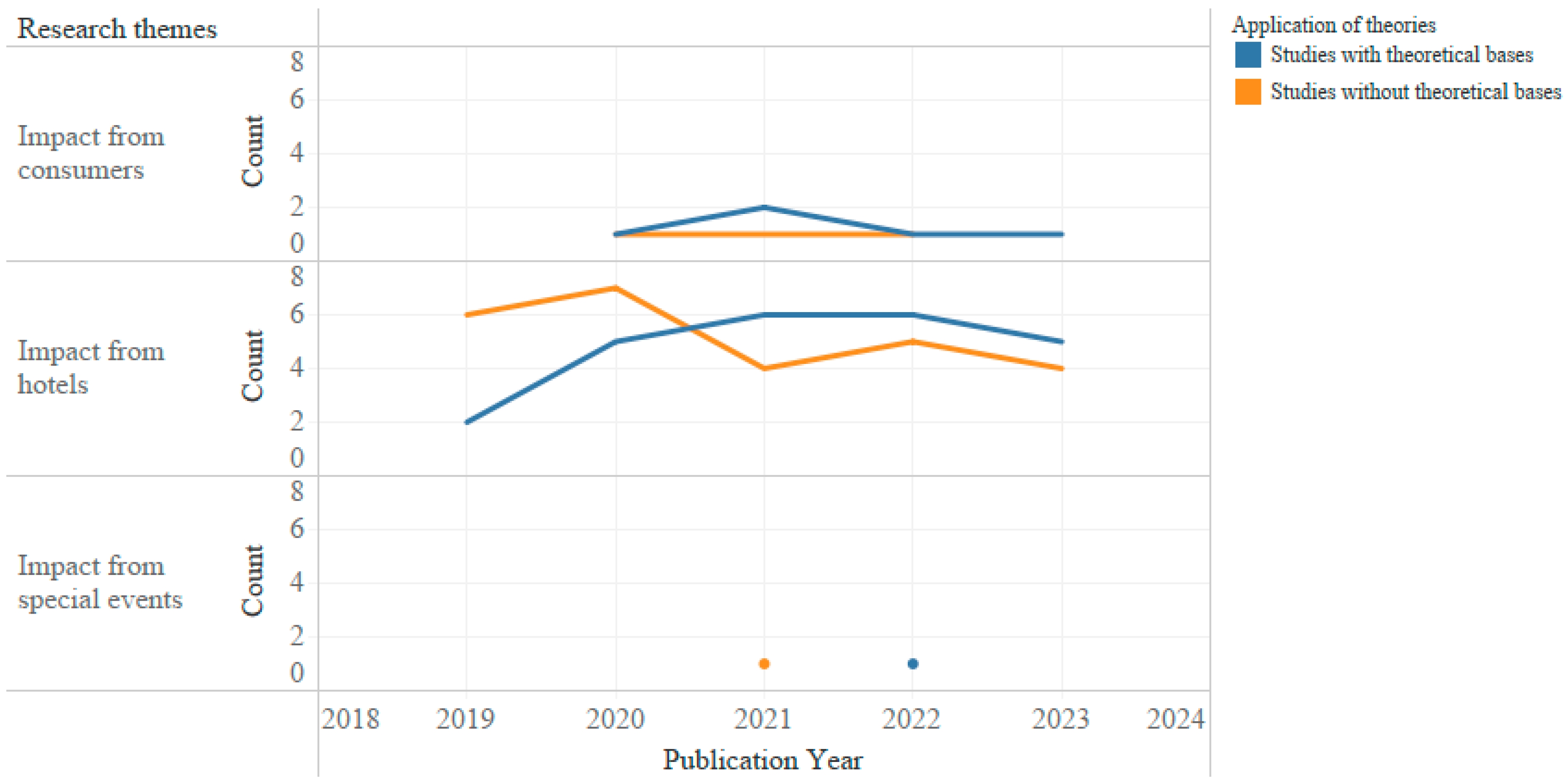

Figure 4.

Development of theoretical applications of each theme.

3. Characteristics of Research on Hotel Impacts on Consumers’ Health

3.1. Research Publication Dynamics

This study analysed the publication trends of the relevant literature regarding the impact of hotels on consumers’ health since 2019. The results showed that, although the growth trend in the number of studies on this topic has fluctuated slightly between 2019 and 2023, it generally shows an increasing trend. It is worth noting that, in the past five years, the number of studies increased the fastest from 2019 to 2020. Based on the distribution of keyword appearance years shown in Figure 2, it can be inferred that this phenomenon may be due to the COVID-19 outbreak at the end of 2019. Especially during the peak of the epidemic, tourism activities decreased because of local policy restrictions [13]. This phenomenon has attracted the attention of scholars in the field of hotel management [14,15].

3.2. Development Trends in the Research Topic

Figure 2 is constructed based on the co-occurrence frequency and appearance time points of keywords closely related to the research topic. The circles in the picture represent keywords in the article, and the diameter of a circle is proportional to the frequency of occurrence of the keywords. The identification of clusters is guided by social cognitive theory, which emphasises that individuals and their environments interact and influence each other [16]. Therefore, the researchers distinguished factors from the external environment and individual consumers in the classification process at first. Then, based on the identified key information, it was found that the external environment factors were dispersed into two parts, as shown in Figure 2. One part is hotel-related factors, circling the “hotel” keyword, and the other part is the external environment clustering factors, circling the “COVID-19” keyword. Based on the concepts and characteristics of the keywords, the researchers obtained three theme clusters. Since all studies in the data set are related to hotels, hotel appears as the most important keyword in the centre of the keyword co-occurrence map. The three clusters extending outward with hotel at the centre represent the sources of impact on the health of hotel consumers. Cluster 1 represents influencing factors directly derived from hotels. Cluster 2 represents the impact of special events. Cluster 3 shows consumers’ personal characteristics, including some other characteristics such as “homeless” in addition to general demographic characteristics such as “age” and “gender”.

The colour of a circle represents the average year of the publication of the keyword. The lighter the colour, the more recent the date the keyword appeared. As can be seen from Figure 2, in the past five years, researchers’ focus has transitioned from the negative impacts faced by hotel consumers to positive impacts. As a special event, COVID-19 has affected the overall trend of research on this topic.

3.3. Methodological Nature

The articles included in this study cover three basic categories of general research methods, namely, quantitative research methods, qualitative research methods, and mixed qualitative and quantitative research methods. However, it can be seen from Figure 3 that researchers are more inclined to use quantitative methods to explore the factors that affect the health of hotel consumers. Among the 55 studies, including 7 studies using mixed research methods, a total of 49 studies used quantitative research methods, accounting for 89.1%.

In studies that choose quantitative methods, researchers tend to use a single survey method to collect data, and the most common survey method is survey by questionnaire [17]. Exploring the relationship and level of influence of variables related to this particular scenario through a questionnaire would be detrimental to the validity of the research results [11]. Some research has attempted to restore real scenes through simulated scenes in the form of pictures or videos [18]. There are also some studies that reduce the occurrence of bias by limiting the time of hotel consumers’ last hotel stay experiences [19,20]. In addition, some studies also use field sampling and laboratory testing to obtain survey data based on their survey methods [21]. Primary data were used in most of the above studies. However, because of some special backgrounds, some researchers needed to use secondary data [22].

Researchers who applied mixed research methods usually combined focus groups or interviews with questionnaires to collect data. Since 2019, research focusing on the health experiences of hotel consumers has rarely adopted purely qualitative research methods. There are only six such studies in the data set, accounting for 10.9%. The interview method is the main data collection method used in these studies, and five articles adopted this method. Only one article selected online blogs as the data source. All six studies used thematic analysis in the content analysis method for data interpretation.

3.4. Theoretical Application

This study conducted analyses of the overall theoretical application status of the relevant research and found that 51.0% of the studies did not mention any theoretical basis. There are 19 theoretically based studies guided by a single theory. Only eight studies have multiple theoretical foundations. The overall trend shows a steady upward trend in the overall number of theory-guided studies. Not only do theory-based studies outnumber non-theory-based studies in terms of the number of publications per year, but the overall pace of their development has also widened the gap.

Stimulus–organism–response (SOR) theory and attachment theory were mentioned the most. Most of the theories used in the articles come from the field of psychology. These psychological theories are used to describe the impact mechanism of consumers’ personal characteristics on their health [23] and the reason why consumers’ health is affected by the environment [16]. Some sociological theories, especially those related to social psychology, are frequently used to explain the process and reasons why hotel consumers’ health is affected, such as social identity theory and terror management theory. Figure 4 shows the development of theoretical applications in research under different themes. From the distribution of research numbers in the figure, it can be seen that research with a theoretical basis accounts for the majority after 2021.

4. Thematic Synthesis

After a content analysis of research on this topic over the past five years, three main source categories that impact hotel consumers’ health were identified.

4.1. Sources of Impact on Hotel Consumers’ Health

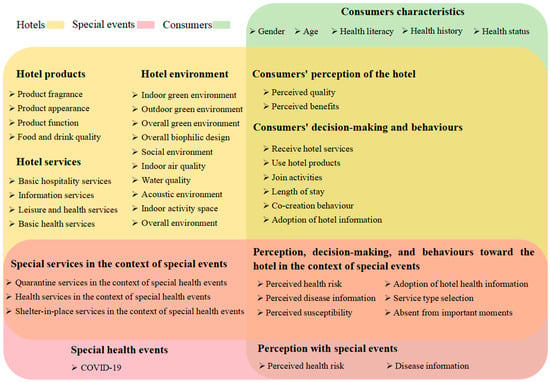

Figure 5 shows the analysis results for the sources of the factors mentioned in the articles collected in this study that impact hotel consumers’ health. According to social cognitive theory, individuals interact with their environments through their cognition and behaviour and are ultimately influenced by both personal and environmental factors [24]. Based on this theory, the researchers began the process of drawing the framework presented in Figure 5 by considering whether the influences mentioned in the article came from the consumers themselves or from the environment (i.e., hotels and special events). The results of this section of the analysis are presented in the nonoverlapping part of the framework diagram, which shows the underlying characteristics of the impact sources themselves. Secondly, the researchers focused on the conclusions of the studies and explored the process by which impacts were generated. The analysis results of this process are shown in the overlapping part of Figure 5.

Figure 5.

Impact sources and processes.

From the perspective of consumers, their inherent demographic characteristics (e.g., gender) are some of the sources that affect their health [25]. In addition, influencing factors from consumers also include some characteristics related to personal health, such as their basic health status before they stay in a hotel [26] and individual health literacy levels [27]. The impact of hotels on consumers mainly comes from three aspects, namely, the services, products, and hotel environment. These features are placed in nonoverlapping areas because these are basic features of the hotel and will not be affected by consumers or special events. Hotel products refer to the tangible products provided by hotels, including products for consumers to use, such as linens [17] and bathtubs [28]. They also include food and drinks (e.g., milk) provided to consumers by hotels [29]. Hotel services refer to the intangible products provided by hotels to consumers. Such products are usually considered to be an important impact source of hotel consumers’ experiences [30]. Services not only refer to reception services provided by employees [31] but also include some other types of services. For example, hotels provide health information services to consumers [32], leisure and health services [33], and just health services [34]. The hotel environment includes both the visual atmosphere inside and outside, such as the green atmosphere of indoor and outdoor spaces [35,36] and a sense of ecological design [25]. Hotel environment factors also include air quality [37], water quality [38], social environments [31], and acoustic environments [26]. These factors are not visually noticeable but will affect consumers when they enter the hotel space. Since the data collection time of this study is limited to between 2019 and October 2023, this study identified only one special event that affected hotel consumers’ health, namely, the COVID-19 pandemic.

Overall, factors affecting hotel consumers’ health come from three different themes: firstly, the consumers themselves; secondly, the hotel; and finally, special events. Compared with influencing factors from consumers themselves, researchers pay more attention to influencing factors from hotels. Within the limited time period of this study, the researchers’ attention to special events affecting consumers’ health was limited to one public health event, namely, the global COVID-19 pandemic that occurred at the end of 2019.

4.2. Hotel Consumers’ Health

Before explaining the ways in which these sources affect consumers’ health, it is necessary to understand what dimensions of consumers’ health are affected. The World Health Organization points out that health should not only be limited to a person’s physical health but also include an individual’s mental health and social health [39]. Therefore, when conducting this thematic analysis of the literature, the relevant outcome variables and conclusions were organised and analysed based on the three dimensions of physical health, mental health, and social health. There are some conclusions or results that represent the overall health status of consumers that cannot be divided into specific dimensions, so this part is considered according to total health. In addition, there are also a few factors that are related to health but do not belong to any of the three dimensions, such as health awareness and health behaviour. Although these factors do not belong to the health status dimension, existing research points out that these contents belong to the health literacy dimension [40]. Health literacy is very important to an individual’s health status [41]. Therefore, health literacy is also separately counted.

In the past five years, researchers have tried to explore the impact of every aspect of consumers’ health status from multiple perspectives. Mental health consists of multiple factors, such as emotions, thinking skills, moods, and psychological functions [42]. Most of the existing studies have measured consumers’ mental health through their emotions. For example, Han and Hyun [19] measured the impact of the hotel environment on consumers’ mental health by determining the alleviation of consumers’ anxiety or worry during their stays. The emotional level is an important representative of the mental health level. Most psychological self-rating scales include emotion-related items, such as the Depression and Anxiety Self-Rating Scale [43]. Therefore, using emotional status to reflect consumer mental health status is one of the most common methods. Mental health not only includes the current mental state but also includes appropriate self-psychological adjustment capabilities. However, few researchers have explored consumers’ mental health levels from this perspective. Only one study explored the impact of the hotel environment on consumer psychological resilience [44].

Physical health refers to the health of an individual’s physiological system, that is, the healthy state of the body’s systems and organs in operation and function [45]. Compared with the research perspective on mental health, the research perspective on physical health is richer. This is because, compared with mental states, the body has many different observable responses to external stimuli, which are also easy to record. Fleming et al. [22] found that hotel living environments reduce the frequency of illness in homeless populations by comparing follow-up visits recorded in the healthcare system for homeless populations living in hotels and those not living in hotels. In addition to this indirect way of obtaining health information, researchers can also directly obtain this information with surveys, determining whether they have diarrhoea [46], asthma [47], or sleep disorders [26] during their stay. In addition to the above already-detectable health states, this study also classified a portion of potential physical health states into this category during its analyses. The first reason is that infectious diseases have a direct negative impact on an individual’s physical health. Secondly, some infectious diseases have an incubation period. Although consumers may not show symptoms while staying in a hotel, they may become carriers of the germs in the hotel. Humans have evolved the instinct to identify infection risks during the evolution process [48], so their perceived infection risks represent, to a certain extent, the probability of a virus being attached to the body.

Social health refers to a balanced relationship between an individual and his or her social environment, namely, the establishment and maintenance of healthy social interactions [49]. Three of the studies in the data set focused on the social health of the general hotel consumer population, with two of the studies centred on specific consumer groups. Nowicki et al. [31] paid attention to the social health of particular consumer groups in hotels, with the study noting that homeless people living in hotels felt unequally treated and isolated as a disadvantaged group. Focusing on full-time workers, Chen et al. [50] explored the recovery of full-time workers’ perceptions of their self-social roles during hotel stays. Health literacy refers to an individual’s comprehensive ability to collect, process, and use health information [51]. Health literacy can have a direct impact on health outcomes [52]. In the studies in the data set, researchers measured consumers’ health literacy by measuring consumers’ health awareness and health behaviours, such as consumers’ health protection awareness [32] and healthy eating habits [53].

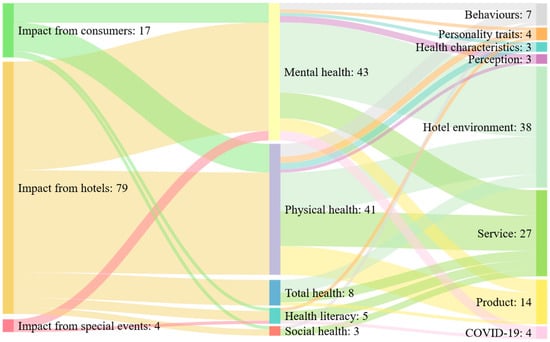

4.3. Impact of Hotels on Consumers’ Health

Figure 6 shows the relationship between influencing factors and consumers’ health in terms of both the primary and secondary themes of influencing sources. The left side of Figure 6 shows the primary theme of influencing factors, and the same horizontal position on the right side represents the secondary classification under this theme. The numbers behind each concept represent the frequency with which the concept has been verified to be related to other variables in the data set. The width of the curve connecting each concept represents the frequency of the association that has been proven to exist in this study. The wider the curve, the more times the association has been proven to exist.

Figure 6.

A framework of factors influencing hotel consumers’ health.

As can be seen from Figure 6, the collected studies prove that factors originating from hotels have an impact on all aspects of consumers’ health. From the identified themes, it was found that consumers mainly interact with hotel resources through perception, decision-making, and behaviour. It should be noted that, when consumers stay in a hotel, they will inevitably interact with hotel resources regardless of whether they actively use hotel resources or not. Therefore, the ways in which hotels impact consumers’ health can be divided into two categories: intentional and unintentional. From a perceptual perspective, when consumers enter the hotel, they have already begun to be affected by the overall atmosphere of the hotel even before they start using the product. For example, when consumers perceive the green atmosphere inside and outside the hotel, they gain pleasant emotions and feelings of relaxation [19,54]. It is worth noting that this relationship between consumer mental health and the hotel environment is verified most frequently in Figure 6, and most of the factors are about the positive impact of the hotel atmosphere on consumers’ mental health through unconscious interactive processes. From a behavioural perspective, consumers always perform some necessary unintentional behaviours. For example, when consumers enter a hotel environment, they are already breathing the air inside the hotel, and the fragrance or particles in the air will have an impact on the consumer’s respiratory system [55,56]. Given the above two aspects, it can be seen that the unintentional impacts on consumers’ health mainly come from the quality of the hotel environment and are due to the passive reception of environmental information by the senses.

Consumers’ intentional perception of hotel resources includes consumers’ further evaluation of the environment and hotel products. This kind of evaluation mainly includes the judgement of quality and the judgement of self-benefit. When consumers feel that they have benefited from the consumption process, they will generate pleasant emotions, thus improving their immediate mental health [36,57]. The service quality perceived by consumers will also affect consumers’ physical health. For example, consumers’ overall satisfaction with hotel service quality will affect their insomnia risk [26]. In contrast to perceptions of consumption, studies in the data set prove that consumers’ conscious decisions and behaviours can have an impact not only on their physical and mental health but also on their social health. For example, consumers’ decisions about accommodation and length of stay will expose them to the threat of some infectious viruses. Common ones include Enterobacterales, which causes digestive tract diseases [58], and Legionella, which causes respiratory diseases [34]. Consumers can also improve or maintain their health by making reasonable use of hotel resources. Consumers can use the health information provided by hotels to avoid possible health risks [32]. Consumers’ social health can be affected by their co-creation behaviour. When hotel consumers implement value co-creation behaviours, they can not only obtain psychological satisfaction but also enhance their perception of their own social status through effective social interaction [59].

4.4. Impact of Special Events and Consumer Characteristics on Consumers’ Health

COVID-19 served as the only special event identified in this study during thematic analysis. This special event both directly and indirectly affects consumers’ health. For example, COVID-19-related information and infection risks perceived by consumers will not only affect consumers’ mental health statuses during their stays but also affect their health behaviours [60]. It is important to note that consumer-perceived disease information and health risks are not necessarily acquired during a hotel stay. The impact of special events on consumers’ health is not limited to the frequency mentioned in Figure 6. The number presented in the figure represents only the frequency with which the relationship between the two concepts in the studies was verified, that is, the number of times this direct relationship was mentioned. During this special event, some hotels served consumers as quarantine places. These specific services arising from special backgrounds affect consumers’ health experience. When hotels are used as quarantine places, consumers are not only severely restricted in their activity space but they are also unable to enjoy the same basic reception and catering services as usual [22]. Some consumers even missed important moments due to quarantine measures [16]. As a result, they were affected not only in their mental health but also in their social and physical health and even in their overall state of health [16,22,23].

Based on the triadic interaction proposed in social cognition theory [24,61], consumers, as the main subjects of the entire influence process, are affected by both individual factors and the environment simultaneously. First of all, through the analysis of the impact of hotels and special events, it can be seen that, before these external events affect consumers’ health, consumers need to have intentional or unintentional perceptual or behavioural interactions with them. In addition to the interaction between consumers and resources playing a role in the above influencing process, there are some inherent characteristics of consumers that affect their health experiences when they stay in a hotel. For example, age and gender lead to different degrees of impact on consumers’ physical health and mental health [25,31]. Consumers’ health literacy level has an impact on their mental health and physical health during their stays [27]. The health literacy that appears here as an independent factor forms a closed loop with the health literacy that appears as a dependent factor, as noted earlier. That is, the health experience that hotel consumers have during their stay also appears to be an influencing factor in other impact processes in the future. This is consistent with the logical relationship of the triadic interaction model proposed by [24] in social cognitive theory.

5. Discussions

5.1. Main Findings

With the increasing number of segmented perspectives on consumer experience, consumers’ health experience is gradually receiving the attention of researchers. This study found that the number of studies related to hotel consumers’ health has steadily increased over the past five years. However, few researchers have organised or summarised the literature related to hotel consumers’ health, resulting in a lack of an overall framework to guide the development of research on this topic. This study was guided by the logical framework of social cognitive theory [24] and combined with the three-dimensional concept of health proposed by the WHO [39] to analyse the research related to hotel consumers’ health in the past five years. After thematic analysis, the researchers identified three themes that have an impact on consumers’ health, namely, hotel characteristics, consumer characteristics, and special events. The number of studies related to the impact of hotel characteristics on consumers’ health is the highest, while the number of studies related to the impact of special events on consumers’ health is the lowest. This reflects that researchers currently focus on the impact of factors within hotels compared with the environment outside the hotel and the characteristics of consumers.

Most studies on hotel consumers’ health have used quantitative research methods. As technology develops, more and more data sources are available for both quantitative and qualitative researchers. Taking special events as an example, although the process of data collection in real time during COVID-19 has met certain difficulties, technological equipment retained a large amount of usable data during the event, such as the number and categories of patients in the medical system [22], as well as blogs published by quarantine hotel consumers on the Internet [62]. The diversification of data sources provides researchers with more opportunities and perspectives to explore factors affecting consumers’ health.

Researchers are paying more and more attention to theory-based research, especially under the themes of the impact of hotels on consumers’ health and the impact of special events on consumers’ health. In 2019, the number of studies without a theoretical basis was three times the number of studies with a theoretical basis. The change in researchers’ emphasis on theory occurred between 2020 and 2021. In 2021, the number of studies with theoretical foundations exceeded those without theoretical foundations, and the gap is gradually widening. Mazanec [63] pointed out that good empirical research should be guided by sound theory. Therefore, this state of development is conducive to improving the overall quality of empirical research on this research topic. Although there are many types of applied theories, their subject areas are relatively concentrated. The most frequently used theories, such as SOR theory and attachment theory, as well as most other applied theories, come from the field of psychology. This also leads to the fact that most of the studies on this research topic are related to the mental health of hotel consumers.

By integrating the research findings in the data set, this study presents two framework figures that can describe the current state of research on this topic, namely, Figure 5 and Figure 6. Figure 5 shows the specific sources of impact on consumers’ health and also shows the impact process. For example, consumers’ health will be affected by the interaction (yellow and green overlapping areas) between consumers with personal characteristics (nonoverlapping green areas in the figure) and hotel resources (nonoverlapping yellow areas in the figure). In addition, this study also points out that the interaction can be divided into intentional interactions and unintentional interactions. Unintentional interaction refers to an interaction process in which external information is obtained directly through consumers’ senses without thinking and processing. No matter which form of interaction is used, it can have an impact on consumers’ physical and mental health. Intentional interaction can also have an additional impact on consumers’ social health and health literacy. Figure 6 can help researchers who are interested in this topic to identify areas that have received the most attention and areas that have been neglected by existing research. This framework can also help researchers, managers, and consumers understand the specific factors that affect consumers’ health.

5.2. Future Research Directions

Healthy experiences are gradually becoming the type of experience that hotel consumers pay close attention to and an important means for hotels to promote their products [64]. Such phenomena provide more research opportunities for researchers in the field of hotel and hospitality management. This systematic literature review analyses the relevant studies on hotel consumers’ health from 2019 to 2023 and explores the major research themes and trends in this area. Based on the findings of the analyses, this study raises research questions related to hotel consumers’ health based on four aspects (Figure 7).

Figure 7.

Research framework of hotel-consumer-health-related studies in the future.

5.2.1. Hotel Perspective

Firstly, existing studies have not only focused on factors that are beneficial to consumers’ health but also identified some factors in hotels that are harmful to consumers’ health. While some facility-related factors can be addressed to prevent problems later, there are also factors that threaten consumers’ health that cannot be completely avoided. For example, hotel consumers may suffer from mental health problems because they believe they are being discriminated against by other guests [65]. There are no studies in the data set that examine which methods of service compensation can eliminate or reduce the health damage suffered by consumers during their stays. Therefore, the first research question from the hotel perspective is posed: in what ways can hotels reduce or eliminate consumers’ negative health experiences during their stays (RQ1)? The second research question is based on factors in hotels that are beneficial to consumers’ health. This study points out that consumers obtain healthy experiences through interactions with hotel resources. In addition to the physical environment, which is mentioned more often in the literature, employees in hotels are also important factors that can have an impact on consumers’ health. It has been found in existing studies that hotel employees can have an impact on consumers’ health, such as based on the type of service provider, operational processes, quality of interactions, and personal characteristics [20,36]. However, this topic still lacks sufficient attention. With the advancement of technology, the service providers for consumers are not only limited to human employees but may also be artificial intelligence devices or even anthropomorphic robotic employees. Many researchers have conducted comparative studies on the impact of these two types of service providers on consumer loyalty, satisfaction, and intention to use studies [66,67]. However, fewer studies have focused their attention on the impact of service providers on consumers’ health experiences. Therefore, what hotels can do to help consumers maximise positive health experiences during their stays remains a question worth exploring from a number of perspectives (RQ2).

In addition, although existing studies have comprehensively explored the factors that exist in hotels that can affect consumers’ health, they are still limited to direct influencing factors. Researchers should pay attention to other possible indirect influencing factors, that is, find the antecedent variables of hotel-related factors that affect consumers’ health (RQ3). For example, the decision-making and support of hotel managers may be important antecedents that influence factors that affect consumers’ health experience. Existing research has confirmed that hotel services, products, and environments can have a significant impact on consumers’ health [17,31,36]. The hotel service model, product selection, and environment construction depend on the hotel manager. Therefore, whether hotel managers can correctly identify the factors that affect consumers’ health experience and support improving consumers’ health experience is one of the most important indirect influencing factors.

The above three research questions summarise and generalise the gaps in existing research from a hotel management perspective. An in-depth study of the above questions can help hotel managers and practitioners further enhance consumers’ healthy wellness experiences in terms of the services, products, and resources they provide to consumers.

5.2.2. Hotel Consumer Perspective

According to social cognitive theory [24], the characteristics of hotel consumers are also factors that cannot be ignored, as they affect consumers’ overall experiences. As can be seen in Figure 3, not only is the number of studies on this theme low but the variety of factors identified is limited, and the studies were mainly conducted in a quantitative manner. Compared with quantitative research, qualitative research is more suitable for the in-depth understanding and description of phenomena, as well as the exploration of new topics [11,68]. Given the current state of affairs with an insufficient base number of studies on this sub-theme, there is a stronger need for qualitative research to explore unknown variables at this stage. Therefore, the fourth research question is raised in this study: how can we discover and supplement more personal consumer characteristic factors that affect consumers’ health based on expanded research methods (RQ4)?

Secondly, by analysing the articles in the data set, this study found that health impacts on consumers are acquired in the form of interactions with external sources, which include both perceptual and decision-making behaviours. In addition, this study found that interactions can be divided into two different types. The first type is intentional interaction, that is, interaction after the consumer has given some consideration to it. The second type is unintentional interaction, which is a process that directly affects health status after being perceived by the senses without being processed by consideration. However, current research on unintentional interactions is limited to visual sensory interactions [54], auditory sensory interactions [26], and olfactory sensory interactions [47]. In the future, researchers can continue to explore how consumers’ health is affected through other types of senses within the sub-topic of unintentional interactions that affect consumers’ health (RQ5).

For consumers, as the main body of health experience, personal factors play a major role in the level of their final health experiences. Therefore, the identification of health experience factors from the consumer’s perspective can not only help hotels to develop reasonable health experience services for consumers but also be beneficial in guiding consumers to enhance their health experience through rational choice and effective use of environmental factors.

5.2.3. Special Event Perspective

This study identified COVID-19 as a special event. This special event is a public health event that is closely related to individual health. For the duration of the event, it had an impact on the business model and service model of the hotel industry, so it has attracted the attention of scholars in this field. Although this theme was identified in this study, follow-up analysis showed that hospitality management researchers were not concerned with the direct impact of this special event on hotel consumers. Researchers were more focused on the impact of changes in hotel service models and products on hotel consumers’ health in this context, for example, the impact of quarantine services provided by hotels during special events on the physical health and mental health of hotel consumers [31]. An overlooked perspective is how special events directly impact consumers’ health during their stay in a hotel (RQ6).

The special event Identified in this study is only one of the global public health events. This phenomenon reflects the fact that although researchers are focusing on the impact of the external social environment of hotels on consumers’ health, the perspective is still limited. There are many other types of global or regional events that may have an impact on hotel consumers’ health. For example, when some natural disasters or terrorist incidents occur, it is worth exploring whether the physical health of consumers living in hotels at the location of the incident will be threatened and whether their mental health will be affected by the incident as well as the extent and durability of the impact. The research question is therefore raised as to how and to what extent other types of special events impact consumers’ health (RQ7). Attention to and research on issues related to special events and hotel consumers’ health is not only conducive to improving the quality of hotel health services but also to improving the hotel’s ability to prevent special events and reduce the extent of losses suffered in similar events.

5.2.4. Consumers’ Health Perspective

With the development of science and technology, there are more and more devices that can evaluate an individual’s health status, and the results are becoming more and more accurate. Most of the data representing the health status of hotel consumers obtained in the data set were obtained through self-assessment questionnaires filled out by consumers who left a hotel. This survey method inevitably has biases caused by various factors [68], such as memory bias, response bias, and expectation bias. Therefore, in the future, it could be explored whether there are other data collection methods that could help researchers obtain a more objective view of consumers’ health status, as well as verify the conclusions obtained from self-assessment surveys (RQ8).

Secondly, social health is significantly different from mental health and physical health. Physical health and mental health can be objectively measured, while social health relies more on the individual’s perceived balance with the surrounding social groups. Therefore, different measures of social health will be used in different community settings. For hotel consumers, they are temporarily in a community setting that is different from their usual living places. Therefore, a more suitable concept of social health for hotel consumers is needed to guide future research. A ninth research question was accordingly posed, namely, how do we measure the social health of hotel consumers (RQ9)?

6. Conclusions

With the increase in the number of studies related to consumer experience, consumers’ health experiences, as a part of consumer experiences, are gaining attention from researchers. In this study, hotels were selected as the context and hotel consumers’ health experiences were used as the topic to conduct a systematic review of studies related to hotel consumers’ health. This study refers to the analysis method of Li et al. [11], who conducted a thematic analysis of existing research guided by theory. Based on the three identified categories of impact sources regarding hotel consumers’ health, the current research status and trends of this topic were analysed based on the time distribution of research publication, research methods, and theoretical basis. This study uses two multidimensional frameworks (Figure 5 and Figure 6) to comprehensively demonstrate the impact sources, impact processes, and affected health types. These two frameworks integrate current fragmented studies and provide researchers with a comprehensive perspective to understand the current status of this research topic. Secondly, this study builds on the findings of all the studies in the data set to propose research questions within this theme that are of value for researchers’ continued exploration. Finally, the results will also guide hotel managers in identifying factors that can affect consumers’ health experiences and conducting rational management.

This study also has some limitations that still need to be addressed. First, this study only selected English journal articles from the WoS and Scopus. Although this method can ensure the quality of the collected studies, it is prone to the omission of other related articles that are not included in these two databases. In future research, the search scope can be expanded, and while increasing database sources, the types of source publications should also be increased, such as conference papers and dissertations. Secondly, the study set a clear publication time limit, that is, from 2019 to October 2023. This results in the study not being able to fully understand the overall development trend of research related to hotel consumers’ health. Future research could expand forwards or backwards around the time period chosen in this study to provide a more complete view of the trends in this topic. Finally, the hotel industry is only a part of the hospitality industry. Future research can explore the health experiences of consumers in other hospitality industries to gain a more comprehensive understanding of the characteristics of this industry.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, Y.J. and A.G.; methodology, Y.J.; software, Y.J.; validation, Y.J., A.G. and P.S.; formal analysis, Y.J. and A.G.; investigation, Y.J. and A.G.; resources, Y.J. and A.G.; data curation, Y.J. and A.G.; writing—original draft preparation, Y.J.; writing—review and editing, Y.J. and A.G.; visualization, Y.J.; supervision, A.G. and P.S. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

The data presented in this study are available in the Web of Science at [www.webofscience.com] and Scopus at [www.scopus.com], accessed on 31 October 2023.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Pine, B.J.; Gilmore, J.H. The Experience Economy; Harvard Business Review Press: Boston, MA, USA, 2011; ISBN 978-1-4221-6197-5. [Google Scholar]

- Oh, H.; Fiore, A.M.; Jeoung, M. Measuring Experience Economy Concepts: Tourism Applications. J. Travel Res. 2007, 46, 119–132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Becker, L.; Jaakkola, E. Customer Experience: Fundamental Premises and Implications for Research. J. Acad. Mark. Sci. 2020, 48, 630–648. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, H.; So, K.K.F. Two Decades of Customer Experience Research in Hospitality and Tourism: A Bibliometric Analysis and Thematic Content Analysis. Int. J. Hosp. Manag. 2022, 100, 103082. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peppers, D.; Rogers, M. Managing Customer Experience and Relationships: A Strategic Framework, 3rd ed.; Wiley Corporate F&A Series; John Wiley & Sons, Inc.: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2017; ISBN 978-1-119-23981-9. [Google Scholar]

- Teng, C.-C.; Cheng, Y.-J.; Yen, W.-S.; Shih, P.-Y. COVID-19 Perceived Risk, Travel Risk Perceptions and Hotel Staying Intention: Hotel Hygiene and Safety Practices as a Moderator. Sustainability 2023, 15, 13048. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, P.C.; Lee, M.J.; Cheng, T.-T. Importance of Wellness Concepts in the Hotel Industry: Perspectives from the Millennials. J. Qual. Assur. Hosp. Tour. 2019, 20, 729–752. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- United Nations THE 17 GOALS | Sustainable Development. Available online: https://sdgs.un.org/goals (accessed on 13 February 2024).

- Pickering, C.; Byrne, J. The Benefits of Publishing Systematic Quantitative Literature Reviews for PhD Candidates and Other Early-Career Researchers. High. Educ. Res. Dev. 2014, 33, 534–548. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Le, T.H.; Arcodia, C.; Novais, M.A.; Kralj, A. What We Know and Do Not Know about Authenticity in Dining Experiences: A Systematic Literature Review. Tour. Manag. 2019, 74, 258–275. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, H.; Zhang, L.; Hsu, C.H.C. Research on User-Generated Photos in Tourism and Hospitality: A Systematic Review and Way Forward. Tour. Manag. 2023, 96, 104714. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elkhwesky, Z.; Elkhwesky, E.F.Y. A Systematic and Critical Review of Internet of Things in Contemporary Hospitality: A Roadmap and Avenues for Future Research. Int. J. Contemp. Hosp. Manag. 2023, 35, 533–562. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sann, R.; Lai, P.-C.; Chen, C.-T. Crisis Adaptation in a Thai Community-Based Tourism Setting during the COVID-19 Pandemic: A Qualitative Phenomenological Approach. Sustainability 2022, 15, 340. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dincer, D.; Gocer, O. Quarantine Hotels: The Adaptation of Hotels for Quarantine Use in Australia. Buildings 2021, 11, 617. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghaderi, Z.; Hall, C.; Beal, L. Quarantine Hotel Employees’ Protection Motivation, Pandemic Fear, Resilience and Behavioural Intention. Curr. Issues Tour. 2023, 26, 681–691. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nanu, L.; Rahman, I. The Biophilic Hotel Lobby: Consumer Emotions, Peace of Mind, Willingness to Pay, and Health-Consciousness. Int. J. Hosp. Manag. 2023, 113, 103520. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Robbins, R.; Grandner, M.; Knowlden, A.; Severt, K. Examining Key Hotel Attributes for Guest Sleep and Overall Satisfaction. Tour. Hosp. Res. 2021, 21, 144–155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Romero, J.; Lado, N. Service Robots and COVID-19: Exploring Perceptions of Prevention Efficacy at Hotels in Generation Z. Int. J. Contemp. Hosp. Manag. 2021, 33, 4057–4078. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, H.; Hyun, S.S. Green Indoor and Outdoor Environment as Nature-Based Solution and Its Role in Increasing Customer/Employee Mental Health, Well-Being, and Loyalty. Bus. Strategy Environ. 2019, 28, 629–641. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shin, H.; Kang, J. Reducing Perceived Health Risk to Attract Hotel Customers in the COVID-19 Pandemic Era: Focused on Technology Innovation for Social Distancing and Cleanliness. Int. J. Hosp. Manag. 2020, 91, 102664. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dehraj, S.; Noor, A.A. Population-Based Study of Environmental Food Pathogens and Their Antibiotic Resistance Pattern. Proc. Pak. Acad. Sci. Part B 2020, 57, 49–58. [Google Scholar]

- Fleming, M.D.; Evans, J.L.; Graham-Squire, D.; Cawley, C.; Kanzaria, H.K.; Kushel, M.B.; Raven, M.C. Association of Shelter-in-Place Hotels with Health Services Use among People Experiencing Homelessness during the COVID-19 Pandemic. JAMA Netw. Open 2022, 5, E2223891. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lu, L.; Zhao, J. Customers’ Purchasing Intentions for Enhanced Cleaning Services in Hotels during COVID-19: Establishing Price Strategies. Consum. Behav. Tour. Hosp. 2022, 17, 232–247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bandura, A. Social Foundations of Thought and Action: A Social Cognitive Theory; Prentice-Hall Series in Social Learning Theory; Prentice-Hall: Englewood Cliffs, NJ, USA, 1986; ISBN 978-0-13-815614-5. [Google Scholar]

- Lee, S. Effects of Biophilic Design on Consumer Responses in the Lodging Industry. Int. J. Hosp. Manag. 2019, 83, 141–150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiong, W.; Fan, F.; Qi, H. Effects of Environmental Change on Travelers’ Sleep Health: Identifying Risk and Protective Factors. Front. Psychol. 2020, 11, 724. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chi, C.; Chi, O.; Ouyang, Z. Wellness Hotel: Conceptualization, Scale Development, and Validation. Int. J. Hosp. Manag. 2020, 89, 102404. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gumá, M.; Drasar, V.; Santandreu, B.; Cano, R.; Afshar, B.; Nicolau, A.; Bennassar, M.; Barrio, J.D.; Crespi, P.; Crespi, S. A Community Outbreak of Legionnaires’ Disease Caused by Outdoor Hot Tubs for Private Use in a Hotel. Front. Microbiol. 2023, 14, 1137470. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dhanalakshmi, M.; Balakrishnan, S.; Sangeetha, A.; Manimaran, K.; Jayalalitha, V. Assessment of Milk Adulteration in the Commercially Available Milk for the Consumers in Cauvery Delta Region of Tamil Nadu, India. Indian J. Dairy Sci. 2020, 73, 131–135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, Y.J.; Kim, H.S. The Impact of Hotel Customer Experience on Customer Satisfaction through Online Reviews. Sustainability 2022, 14, 848. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nowicki, M.; Brickell, K.; Harris, E. The Hotelisation of the Housing Crisis: Experiences of Family Homelessness in Dublin Hotels. Geogr. J. 2019, 185, 313–324. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- García-Montero, P.; Blázquez-Sánchez, N.; Rivas-Ruíz, F.; Millán-Cayetano, J.F.; Fernández-Canedo, I.; de Troya-Martín, M. Preventing Skin Cancer Among Staff and Guests at Seaside Hotels. J. Cancer Educ. 2020, 35, 501–508. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Huh, C.; Lee, M.; Lee, S. A Profile of Spa-Goers in the U.S. Luxury Hotels and Resorts: A Posteriori Market Segmentation Approach. J. Hosp. Mark. Manag. 2019, 28, 1032–1052. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marras, L.; Bertolino, G.; Sanna, A.; Carraro, V.; Coroneo, V. Legionella Spp. Monitoring in the Water Supply Systems of Accommodation Facilities in Sardinia, Italy: A Two-Year Retrospective Analysis. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2023, 20, 6722. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kim, T.; Yun, S. Research Framework Built Natural-Based Solutions (NBSs) as Green Hotels. Sustainability 2022, 14, 4282. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Quan, L.; Kim, J.; Han, H. Customer Views on Comprehensive Green Hotel Selection Attributes and Analysis of Importance-Performance. J. Travzel Tour. Mark. 2022, 39, 535–554. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chang, H.; Huh, C.; Legendre, T.S.; Simpson, J.J. Exploring Particulate Matter Pollution in Hotel Guestrooms. Int. J. Contemp. Hosp. Manag. 2020, 32, 1131–1162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fotheringham, P.; Dorney, E.; McKinn, S.; Fox, G.J.; Bernays, S. Protecting Mental Health in Quarantine: Exploring Lived Experiences of Healthcare in Mandatory COVID-19 Quarantine, New South Wales, Australia. SSM-Popul. Health 2023, 21, 101329. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- The world health organization Constitution of the World Health Organization. Am. J. Public Health Nations Health 1946, 36, 1315–1323. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cho, J.; Park, D.; Lee, H.E. Cognitive Factors of Using Health Apps: Systematic Analysis of Relationships Among Health Consciousness, Health Information Orientation, eHealth Literacy, and Health App Use Efficacy. J. Med. Internet Res. 2014, 16, e125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Berkman, N.D.; Sheridan, S.L.; Donahue, K.E.; Halpern, D.J.; Crotty, K. Low Health Literacy and Health Outcomes: An Updated Systematic Review. Ann. Intern. Med. 2011, 155, 97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Galderisi, S.; Heinz, A.; Kastrup, M.; Beezhold, J.; Sartorius, N. Toward a New Definition of Mental Health. World Psychiatry 2015, 14, 231–233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Svanborg, P.; Åsberg, M. A New Self-rating Scale for Depression and Anxiety States Based on the Comprehensive Psychopathological Rating Scale. Acta Psychiatr. Scand. 1994, 89, 21–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, J. Exploring the Role of Healthy Green Spaces, Psychological Resilience, Attitude, Brand Attachment, and Price Reasonableness in Increasing Hotel Guest Retention. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2020, 17, 133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Engel, G.L. A Unified Concept of Health and Disease. Perspect. Biol. Med. 1960, 3, 459–485. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lago, K.; Telu, K.; Tribble, D.; Ganesan, A.; Kunz, A.; Geist, C.; Fraser, J.; Mitra, I.; Lalani, T.; Yun, H.C. Doxycycline Malaria Prophylaxis Impact on Risk of Travelers’ Diarrhea among International Travelers. Am. J. Trop. Med. Hyg. 2020, 103, 1864–1870. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Steinemann, A.; Goodman, N. Fragranced Consumer Products and Effects on Asthmatics: An International Population-Based Study. Air Qual. Atmos. Health 2019, 12, 643–649. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schaller, M.; Park, J.H.; Kenrick, D.T. Human Evolution and Social Cognition. In Oxford Handbook of Evolutionary Psychology; Barrett, L., Dunbar, R., Eds.; Oxford University Press: Oxford, UK, 2012; pp. 491–504. ISBN 978-0-19-856830-8. [Google Scholar]

- Breslow, L. A Quantitative Approach to the World Health Organization Definition of Health: Physical, Mental and Social Well-Being. Int. J. Epidemiol. 1972, 1, 347–355. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, C.C.; Han, J.; Wang, Y.C. A Hotel Stay for a Respite from Work? Examining Recovery Experience, Rumination and Well-Being among Hotel and Bed-and-Breakfast Guests. Int. J. Contemp. Hosp. Manag. 2022, 34, 1270–1289. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sørensen, K.; Van Den Broucke, S.; Fullam, J.; Doyle, G.; Pelikan, J.; Slonska, Z.; Brand, H.; (HLS-EU) Consortium Health Literacy Project European. Health Literacy and Public Health: A Systematic Review and Integration of Definitions and Models. BMC Public Health 2012, 12, 80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Berkman, N.D.; Davis, T.C.; McCormack, L. Health Literacy: What Is It? J. Health Commun. 2010, 15, 9–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cozzio, C.; Volgger, M.; Taplin, R. Point-of-Consumption Interventions to Promote Virtuous Food Choices of Tourists with Self-Benefit or Other-Benefit Appeals: A Randomised Field Experiment. J. Sustain. Tour. 2022, 30, 1301–1319. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, H.; Yu, J.; Hyun, S.S. Effects of Nature-Based Solutions (NBS) on Eco-Friendly Hotel Guests’ Mental Health Perceptions, Satisfaction, Switching Barriers, and Revisit Intentions. J. Hosp. Mark. Manag. 2020, 29, 592–611. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Steinemann, A. International Prevalence of Fragrance Sensitivity. Air Qual. Atmos. Health 2019, 12, 891–897. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Steinemann, A.; Klaschka, U. Exposures and Effects from Fragranced Consumer Products in Germany. Air Qual. Atmos. Health 2019, 12, 1399–1404. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, H. A Pilot Study of Business Travelers’ Stress-Coping Strategies. Tour. Hosp. Res. 2019, 19, 252–258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meurs, L.; Lempp, F.S.; Lippmann, N.; Trawinski, H.; Rodloff, A.C.; Eckardt, M.; Klingeberg, A.; Eckmanns, T.; Walter, J.; Lübbert, C.; et al. Intestinal Colonization with Extended-Spectrum Beta-Lactamase Producing Enterobacterales (ESBL-PE) during Long Distance Travel: A Cohort Study in a German Travel Clinic (2016–2017). Travel Med. Infect. Dis. 2020, 33, 101521. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yi, X.; Ul Haq, J.; Ahmed, S. Impact of Customer Participation in Value Co-Creation on Customer Wellbeing: A Moderating Role of Service Climate. Front. Psychol. 2023, 13, 877083. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, J.; Lee, K.; Hyun, S.S. Understanding the Influence of the Perceived Risk of the Coronavirus Disease (COVID-19) on the Post-Traumatic Stress Disorder and Revisit Intention of Hotel Guests. J. Hosp. Tour. Manag. 2021, 46, 327–335. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, L.; Zheng, F.; Xiong, J.; Wu, X. Relationship of Patient-Centered Communication and Cancer Risk Information Avoidance: A Social Cognitive Perspective. Patient Educ. Couns. 2021, 104, 2371–2377. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tham, A. Hotel Quarantine Guest Blogs: Unpacking Scheiner’s Spaces of Immobility and Implications on Urban Tourism Politics. Cities 2023, 134, 104202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mazanec, J.A. Hidden Theorizing in Big Data Analytics: With a Reference to Tourism Design Research. Ann. Tour. Res. 2020, 83, 102931. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bonfanti, A.; Vigolo, V.; Yfantidou, G. The Impact of the Covid-19 Pandemic on Customer Experience Design: The Hotel Managers’ Perspective. Int. J. Hosp. Manag. 2021, 94, 102871. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Poria, Y.; Beal, J.; Shani, A. “I Am so Ashamed of My Body”: Obese Guests’ Experiences in Hotels. Int. J. Hosp. Manag. 2021, 92, 102728. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiong, X.; Wong, I.A.; Yang, F.X. Are We Behaviorally Immune to COVID-19 through Robots? Ann. Tour. Res. 2021, 91, 103312. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pozharliev, R.; Rossi, D.; De Angelis, M. Anxious Attachment Style and Consumer Physiological Emotional Re-sponses to Human–Robot Service Interactions. J. Neurosci. Psychol. Econ. 2021, 14, 59–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhattacherjee, A. Social Science Research: Principles, Methods, and Practices, 2nd ed.; University of South Florida: Tampa, FL, USA, 2012. [Google Scholar]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).