Abstract

It is of general concern how poverty concentrates in cities, due to its close association with social equality issues. This research explores this topic at a citywide level. Spatial data of social housing regarding 2008 to 2020 in Shanghai are utilized to examine how the concentration patterns for low-to-moderate-income groups have changed. Multiple methods including spatial autocorrelation analysis, location quotient (LQ), and Mann–Whitney U test were employed to assess the spatial distribution of, and concentration patterns in, social housing, as well as investigating whether the spatial distribution of urban resources was equitable for residents in social housing. We found that the low-to-moderate-income groups were previously concentrated at the boundary of central city and then gradually deconcentrated into a relatively even pattern. However, it is important to note that this process has not effectively facilitated social equality due to the unequitable distribution of urban resources. Consequently, we recommend that policy makers in developing countries pay particular attention to site selection for social housing and the distribution of urban amenities in the future.

1. Introduction

In recent decades, many global metropolitan cities have experienced a process of poverty concentration, which has led to an uneven spatial distribution of low-income populations in certain urban areas. This is associated with serious social problems, including homicide, violence, crime, child abuse, racial segregation, income segregation, and class-based residential segregation [1,2,3,4,5,6,7,8,9]. Therefore, it is of general concern for both scholars and governments. In the global context, poverty concentration has been recognized as a social justice issue and has raised concern from many scholars regarding the aspects of the unfair distribution of public facilities, durable social-economic stratification, and racial segregation [3,10,11,12,13,14,15,16,17].

China is a good case study for understanding poverty concentration in transition, because its society has experienced a profound revolution from a planned economy to market economy in past decades. The extant research on poverty concentration in China has mostly studied the concentration of various social groups in terms of associated socioeconomic factors, demographic characteristics, and specific neighborhood types [7,18,19,20,21,22,23,24]. The increasing spatial segregation and significant changes in urban landscapes in China in recent years intuitively raise the concern of whether urban poverty is concentrated at the citywide level or still in pockets of neighborhoods. Therefore, using the spatial data of social housing in Shanghai, this research contributes to our understanding of poverty concentration at a citywide level from a spatial perspective and its implications for social equality in urban China. The findings might have important implications for policy making regarding social housing and urban resource distribution in developing countries.

The aim of this study is to examine whether the low-to-moderate-income populations were concentrated citywide and understand how things changed in a given period in order to understand the social inequality issues in urban China, by addressing the following questions:

(a) What are the spatial distribution patterns in social housing in Shanghai?

(b) Did low-to-moderate-income groups become geographically concentrated or deconcentrated at a citywide level from 2008 to 2020?

(c) Does poverty deconcentration improve social equality in urban China?

Shanghai is chosen as a case study, since it is a representative Chinese metropolis that is experiencing serious social segregation problems [25,26,27]. Compared with most existing urban China studies [18,19,23,24], which analyzed the demographical characteristics of poor urban populations, our study made use of the spatial distribution and concentration patterns in social housing to reveal the situation of low-to-moderate-income populations whose living demands are guaranteed by the housing security system in China. According to the terms in ‘Guidelines for construction of social housing in Shanghai’ (2010) and ‘Shanghai Housing Development 12th Five Year Plan’ (2012), the housing security system in Shanghai includes four types of housing. These are cheap rental housing (CRH, Lianzu Fang) for the lowest-income households, economical and comfortable housing (ECH, Jingji Shiyong Fang)/shared-ownership housing (SOH, Gongyou Chanquan Fang) for low-to-moderate-income households, public rental housing (PRH, Gongzu Fang) for certain groups such as new graduates at slightly lower rental price than the market level, and resettlement housing (RH, Dongqian Anzhi Fang)/capped-price housing (CPH, Xianjia Shangpin Fang) for relocated residents or farmers from urban renovation projects. In this article, we use the term ‘social housing’ to refer to the four types of housing. The regulation stage for the housing market, emphasizing the housing security system, was chosen as the study period; it began in 2008, signified by the Shanghai Municipal Government issuing ‘Implementation Opinions on Implementing the Spirit of the Documents from Office of the State Council and Promoting the Healthy Development of this Municipality’s Real Estate Market’, and ended in 2020, when COVID-19 substantially changed China’s urban life.

Social housing in Shanghai is built or renovated from existing structures by the local government and managed by Shanghai Housing Management Bureau. The individuals or households with Shanghai Hukou (the household registration system in China) or, in some cases, with a residence permit (a proof issued by the government for those who live and work in the long term in Shanghai), have the chance to apply for social housing, but only if they are not home owners or live in extremely small apartments (≤15 m2 per person), as well as have low incomes (disposable income ≤ CNY 86,400/year/person). Generally, people with Hukou are considered an invulnerable group in urban China. However, our study focuses on the vulnerable part of this group. Despite being registered with Hukou, they have little space to live in, owing to their low incomes, and, therefore, they are beneficiaries of the housing security system. This research contributes to the current topic on the subject of poverty concentration and residential spatial patterns from theoretical and policy-orientated perspectives, by conducting a systemic examination of the spatial patterns in social housing across Shanghai in the period of the regulation of the housing market, emphasizing the housing security system from 2008 to 2020. First, we provide the spatial perspective of social housing to understand the poverty concentration and subsequent social inequality issues against the particular background of China’s housing system reform. Second, we review the previous work on urban poverty concentrations, which has focused on cities in developed countries, especially American metropoles, while limited research on Chinese cities implies an unobvious poverty concentration at the citywide level. Our study demonstrates the existence of poverty concentration at a citywide level in Chinese cities. Third, in previous research, an association between poverty deconcentration and social equality has been established. In contrast, the results of our study imply that this association might not work in developing countries such as China, because geographically deconcentrated poverty does not equate to equal urban resources for those moderate-to-high-income populations. These insights could help policy makers review and reevaluate housing policies, especially those related to social housing and urban amenities.

The remainder of this article will be organized as follows. Section 2 reviews the literature on poverty concentration and residential spatial patterns. Section 3 introduces the methodology. Following the introduction of the study area, we will analyze the multiple-source data to essentially capture the spatial patterns in social housing in Shanghai. Further, to achieve the research objective and answer the research questions, a geospatial database, including the necessary variables related to social housing, has been created. Moreover, the study analyzed the spatial autocorrelation and computed the amount of social housing compounds in each subdistrict as a proportion of the total urban housing. The Global and Local Moran’s I and LQ were spatially calculated to measure how the social housing was distributed and concentrated across the city, and the Mann–Whitney U test was utilized to analyze the socioeconomic characteristics of regions with different levels of social housing agglomeration. Section 4 presents the findings on the spatial distribution and concentration patterns in social housing in Shanghai and the distribution of urban resources in high- and low-concentration regions. Section 5 explains how the study results answer the study questions. Finally, Section 6 summarizes the main findings of this study and proposes several housing policy implications.

2. Literature Review

2.1. Poverty Concentration

Studies on poverty concentration are mostly conducted in developed countries, especially in the United States. Previous studies show that racial segregation [3,28], public housing [29], the proportion of immigrants [30], economic health [31], and access to public transportation [32] can be responsible for poverty concentration. Due to the social problems caused by poverty concentration [1,31,33], federal governments have pursued poverty deconcentration through several measures, such as demolishing public housing [34], providing housing vouchers [34,35,36,37], and developing assisted-housing programs [14]. There have been debates on whether these measures work in practice. Crump questioned the dynamics of demolishing public housing to deconcentrate poor populations [34]. Owens suggested that assisted housing policy could not substantially reduce poverty concentration, given the durable urban inequality in the US [14]. Wyly and DeFilippis mapped the public housing in New York City and demonstrated that housing vouchers were not consistently associated with poverty deconcentration [38]. However, research in Atlanta and Western New York revealed that Housing Choice vouchers helped in the process of poverty deconcentration [35,39]. In recent years, the US has witnessed rapid increases of housing stock in the suburbs, which have allowed poor populations historically concentrated in city centers to have more access to the suburbs [13]. By 2013, more poor people were living in the suburbs than in the urban cores, and this process of poverty suburbanization or deconcentration was related to many socioeconomic factors, such as job decentralization, gentrification, and improved public transportation in the suburbs [8,13,16,40,41,42]. To some extent, the factors that explained the rising poverty in suburbs and city centers were the same [5], and suburban poverty concentration required more attention from scholars and policy makers [8]. Poverty concentration has also been studied in other countries. Orford utilized spatial statistical methods to measure the affluent and poor clusters in inner London to reflect the long-term changes in poverty concentration [2]. Ades et al. studied the eight largest Canadian cities and found that low-income groups lived in more spatially concentrated areas, but socioeconomically in a more dispersed pattern from 1986 to 2006 [42].

Studies in developing countries have revealed some different characteristics on the same topic. Khan et al. demonstrated that in Tanzania, the degree of poverty concentration and health measures were related [43]. In Gauteng, South Africa, the concentration, spatial spread, and orientation of poverty varied across the province, while a spatial autocorrelation also existed [44]. Research in Kumasi, Ghana showed gradually expanding spatial enclaves of poor urban populations impacted by people’s educational attainment and socioeconomic status [9]. Compared with those in developed countries, the studies in developing countries are limited and less systematic.

The concept of poverty concentration in the context of urban China is relatively new, and most research has been conducted at the neighborhood or nationwide level because there are no obvious ghettos in Chinese cities. At the neighborhood level, Liu and Wu (2006) proposed three types of poverty neighborhoods: inner-city dilapidated residences, degraded workers’ villages, and rural migrants’ enclaves, which accommodated impoverished groups in the city consisting of unemployed workers and rural migrants [45]. Of these, the inner-city dilapidated residences (old inner-city neighborhoods) had the highest poverty concentration [23]. Since it lacked the dimension of ethnic segregation, the poverty concentration at the city level was more moderate than that at the neighborhood level in China [20]. For the particular social groups living in specific impoverished neighborhoods, the neighborhood effect increased their possibility of becoming poor [22]. Research in Hong Kong showed that public rental housing did not contribute to poverty concentration in the neighborhoods where it was located and the surrounding neighborhoods, as has been observed in other countries [21]. At the nationwide level, Fang et al. conducted a household survey and found that the western region of China had the highest concentration of poverty, with a widening income gap between this region and the others [46]. Moreover, studies in 2016 demonstrated that this situation had not changed [47]. At the citywide level, previous studies in China have illustrated a pattern different from the ‘slum’ aggregation in other countries. Chen et al. examined the spatial distribution of poor urban populations in Nanjing and concluded that poor urban populations were distributed in decentralized and stochastic patterns due to the legacy of socialist housing allocations, while pockets of urban poverty were found in the city [18,48]. Guo et al. demonstrated that the high poverty concentration in Hong Kong existed in both the inner city and suburbs [7]. In urban China, poverty concentration is also closely related to social inequality. Despite the absence of ethnic segregation [20], social segregations in income, class, and immigrant dimensions contribute to poverty concentration [7,45,46].

2.2. Residential Spatial Patterns

There have been extensive arguments about the spatial patterns in urban housing, mainly from two perspectives. The first perspective focuses on the social inequality that can be explored through the spatial distribution of urban housing or certain groups. On one hand, inequality exists among different groups or types of housing. In American metropolitan areas, the degree of residential separation varies considerably across different ethnic groups [49]. The research in Guangzhou showed that in the first decade of the 21st century, residential segregation was relatively moderate, and social housing was more segregated than commercial housing [50]. On the other hand, inequality also exists even within the same type of housing. A study in Montreal showed that the accessibility of urban resources was not equal for residents of public housing [51]. The second perspective concerns the relation between specific socioeconomic factors and the residential spatial distribution. Generally, urban residential spatial patterns have been associated with housing prices and rents [52], employment opportunities [53,54], and the provision of urban facilities [55]. For particular housing types, research in Hong Kong showed that the spatial distribution of public housing was affected by surrounding residential rents, open space coverage, and the provision of education and health care facilities [56]. In American metropolitan areas, the increase in high-poverty neighborhoods in the urban core and inner ring has been linked to economic health and rapid population growth, respectively [31]. Regarding specific groups such as immigrants, studies in Oman have demonstrated that their residential spatial patterns were structured by their skill profiles [57], and research in Shanghai showed that the overall spatial restructuring or the impact of a neoliberal approach in the unique urban political economy in China located the immigrants [58,59]. Immigrants from developing countries living in Seoul tended to live near universities, but the presence of those from developed countries was increased in regions with more culture facilities [60].

3. Methodology

3.1. Study Area

In this study, we use the case of Shanghai to illustrate how the spatial distribution pattern in social housing in China has changed in the period of the regulation of the commercial housing market. Shanghai, a city in the Yangtze River Delta, is China’s economic and financial center. In the last few decades, Shanghai has experienced fast urbanization, with the urban population increasing by 125% from 1978 to 2020 (https://tjj.sh.gov.cn/index.html, accessed on 17 September 2022.), and to satisfy the living demands of citizens, a large amount of housing has been built. Accompanying the rapid economic growth, housing rents and prices in Shanghai have significantly increased. In 2016, the average price of commercial housing in Shanghai increased by approximately 42% (https://m.gotohui.com/years/3/2016/, accessed on 22 July 2023.), but citizens’ disposable income increased only 8.6% from 2016 to 2017 (https://tjj.sh.gov.cn/index.html, accessed on 22 July 2023). The surging housing price and stagnant income might place residential burdens on low-to-moderate income residents and cause them to have a stronger reliance on the housing security system. Therefore, Shanghai is used as a representative city for this study.

The spatial units in this study are Shanghai’s 225 subdistricts, which belong to 16 districts. Compared with uniform grids, the subdistricts are basic administrative units in Shanghai, fit into boundaries of urban management, land use, economic, and social properties, and therefore more suitable as the study units. In the study area, the urban center is the Lujiazui CBD, the central city is the area inside the outer ring viaduct, which is approximately 15 km around the urban center, and the suburban zone is the area between the outer ring viaduct and the ring expressway, which is approximately 15–40 km away from the urban center. Additionally, the area outside the ring expressway is the outskirt zone (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Study area.

3.2. Data Sources

In this study, we collected data from the website of China land market (https://www.landchina.com/#/, accessed on 22 July 2023) and the property agency Beike (https://sh.ke.com/, accessed on 22 July 2023), using web crawler technology to collect information including longitude, latitude, location, land prices, land use, transfer year, the names of residential compounds, the year of construction, ownership, the number of dwelling units, and housing prices. The collection time was December 2020, and the area was Shanghai. After the data collection, we supplemented missing information and eliminated repeated data according to the names of residential compounds. The Shanghai Statistical Yearbook 2020 (https://tjj.sh.gov.cn/index.html, accessed on 22 July 2023) shows that the urban population of Shanghai at the end of 2019 was 24.28 million and 2.64 people per household; therefore, there were 9.20 million dwelling units. The number of dwelling units that we collected from the website is 8.92 million, with a margin of error of 3% with the result from the Shanghai Statistical Yearbook. Therefore, we believe that the data are accurate and can reflect the real situation of housing construction in Shanghai. The social housing was selected based on ownership, and data with a construction year before 2008, 2012, 2016, and 2020 were selected, respectively, to explore the changes in spatial distributions. In addition, the data for explanatory variables are from the Seventh National Population Census of the People’s Republic of China 2021 and the POI of Baidu.

3.3. Methods

3.3.1. Spatial Autocorrelation Analysis

To depict the characteristics of the spatial distribution of social housing, we used Moran’s I [61] in ArcGIS to assess the degree of clustering of the social housing in the two study years. Its formula is given as

In which, , is the number of subdistricts, and represent the number of social housing compounds in unit and , respectively, is the mean counts of social housing compounds in all spatial units, and is the spatial weight value. The Moran’s I statistic range is in the interval [−1, 1]. If > 0, then the spatial pattern is clustered, if < 0, then the spatial pattern is dispersed, and if = 0, then the spatial distribution is completely random.

In addition, the local Moran’s I [62] was utilized to reflect the spatial heterogeneity of territorial units, and statistically significant clusters are represented in the local indicators of spatial association (LISA). The formula is defined as

in which and are expressed in deviations from the mean, and is the spatial weight value. , is the number of subdistricts, and is the number of social housing compounds in unit . Ii represents the local Moran’s I in unit . The LISA detects the significant patterns of association around an individual location, including hot spots and spatial outliers [62].

3.3.2. Location Quotient (LQ)

The LQ index is a technique that is utilized to measure the proportion of the presence of a phenomenon in a geographic zone relative to the proportion of the same phenomenon in the whole study area. This method has been utilized to investigate the geographic distributions and concentrations of immigrants in a country [57,63], to address the employment concentrations in an industrial sector [64,65], and to analyze spatial patterns in industrial locations [66,67] or crime counts [68]. Liu used this method in the analysis of the spatial patterns in housing tenure in Guangzhou in 2000 and 2010, respectively, and explored the logic of urban housing distribution and the dynamics of residential segregation in China [50].

In this study, the index has been primarily used to distinguish the spatial concentration patterns in social housing for all urban housing across Shanghai, in 2008, 2012, 2016, and 2020. The patterns in the spatial distribution of social housing at various subdistricts are captured well with . In addition, this measurement allows us to map the spatial distribution of social housing at different times and in different zoning systems, which is necessary for the research on the spatiotemporal characteristics of China’s urban housing. For example, the comparison of the degrees of geographical concentration of social housing in different study years may lead to an understanding of the effect of social housing policies during this period. It is estimated that certain zones in Shanghai may have larger shares of social housing. Alternatively, other zones may have smaller ones. The calculation formula for is [69]

where represents the number of social housing compounds in subdistrict , represents the number of social housing compounds in Shanghai, stands for the total number of urban housing compounds (including social housing, commercial housing, and welfare public housing) in subdistrict , and stands for the total number of urban housing compounds in Shanghai. If < 1, then it refers to a lower share of social housing in subdistrict , compared to Shanghai as a whole. If = 1, then subdistrict has a share of social housing in accordance with global standards. If > 1, then it indicates a relative concentration of social housing compared to that which is generally found. The higher the , the higher the agglomeration level.

3.3.3. Mann–Whitney U Test

We employ the Mann–Whitney test to discern the spatial distributional relationship between socioeconomic characteristics and social housing agglomeration. The test compares measures of location for two groups, subdistricts with high concentration of social housing vs. subdistricts with low concentration of social housing, based on the LQ results above, examining whether urban resources favor residents of social housing over other residents or equally. The formula is defined as

in which and are the sample size of each group, and Ri is the rank. and are the mean and standard deviation of . A two-sided test is conducted for the Z score, and the sign of estimation results points to different meanings. The positive sign illustrates that Group 1’s values are larger than Group 2’s values, while the negative sign shows smaller values for Group 1 than those for Group 2.

As summarized in the literature review in Section 2, the spatial patterns in urban housing and low-to-moderate-income populations are closely associated with housing prices and rents, employment opportunities, urban facilities, education, healthcare, ethnicity, and demographic composition [3,28,30,32,52,53,54,55,56]. In this study, we examined 19 socioeconomic characteristics in regions with high and low social housing agglomerations, respectively (Table 1). These variables can reveal the demographic characteristics in each subdistrict, the extent to which urban regions have been developed, the spatial distribution of urban amenities, and the housing affordability across the city.

Table 1.

Definitions of variables.

4. Results

4.1. Spatial Distribution of Social Housing

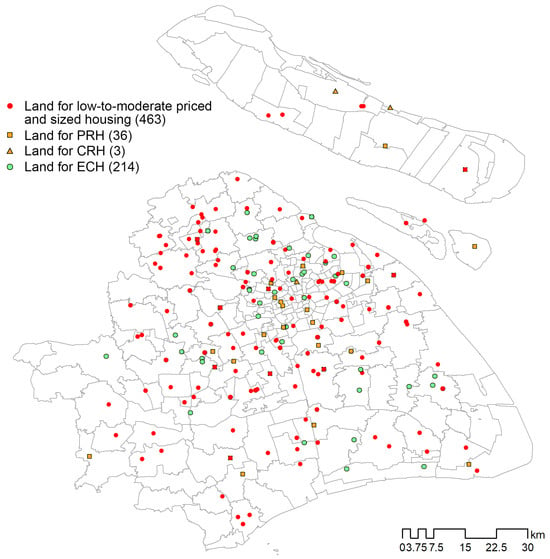

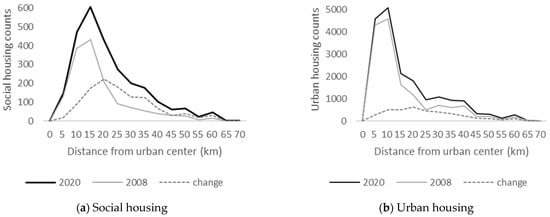

From 2008 to 2020, there were 716 pieces of land for social housing transferred in total. Of these, about 64.7% (463 pieces) were land for low-to-moderate-priced and -sized housing. This type of land is for the construction of RH or CPH. Others were lands for PRH (5%), CRH (0.4%), and ECH (29.9%) (Figure 2). The geographical profiles of social housing compared with those of urban housing reflect that the social housing in Shanghai distributes further from the urban center than other types of housing (commercial housing and welfare housing). Figure 3a shows the distributions of social housing for both study years and the changes in residential compound counts over different distances from the urban center. The figure illustrates that the largest quantity of social housing was about 15 km away from the urban center, at the boundary of central city, for both 2008 and 2020. However, the dotted line in Figure 3b shows that the largest amount of newly built social housing during this period was about 20 km away from the urban center, and the increase in social housing was mainly distributed in suburban zones rather than the central city or outskirt zone.

Figure 2.

Land transfer for social housing in Shanghai, 2008–2020.

Figure 3.

Geographical profiles of social housing (a) and urban housing (b) in 2008 and 2020, and their changes (2008–2020), Shanghai.

In comparison, Figure 3b shows the geographical profiles of urban housing in 2008 and 2020. The general patterns in urban housing remained almost the same over these years: more concentrated in the central city, within 10 km of the urban center. The number of residential compounds drops dramatically at the 10–15 km mark and shows a decreasing pattern further away from the center, only increasing a little at the 25–30 km mark, close to the boundary of the suburban zone. The change in urban housing is smooth over different distances, compared with that in social housing.

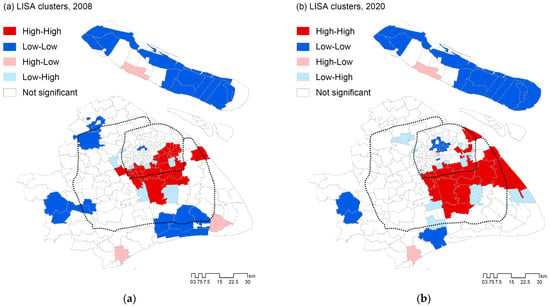

The Global Moran’s I shows the clustered patterns in social housing in both study years, and, from the global perspective, the clustered degree has changed from 0.39 to 0.35 (Table 2). Figure 4 depicts four types of LISA clusters in the analysis. Among them, high-high and low-low mean positive spatial autocorrelation occurs where similar values of high or low for a random variable tend to cluster in space. Additionally, high-low and low-high mean negative spatial autocorrelation occurs where dissimilar values tend to cluster in space. Moreover, ‘not significant’ indicates that spatial autocorrelation does not occur. In 2008, the spatial distribution of social housing is characterized by the pattern of high-high clusters (high values surrounded by high values) around the boundary of central city in the south, with some low-high clusters (low values surrounded by high values), and scattered low-low clusters (low values surrounded by low values) mainly in the outskirt zone and a small portion in the central city, with several high-low (high values surrounded by low values) clusters nearby. In contrast, the situation had changed greatly by 2020. The high-high clusters extended and moved south and east, mainly to the suburban zone rather than the boundary of central city, with several low-high clusters. Some low-low clusters in the north and south of the outskirt zone disappeared, but those in the central city have extended, with a few high-low clusters remaining nearby (Figure 4).

Table 2.

Global Moran’s I of social housing.

Figure 4.

LISA clusters of social housing counts at the subdistrict level: (a) 2008, (b) 2020.

4.2. Spatial Concentration of Social Housing

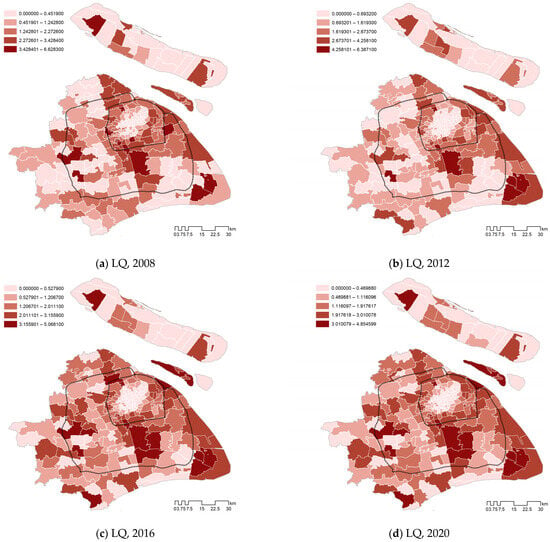

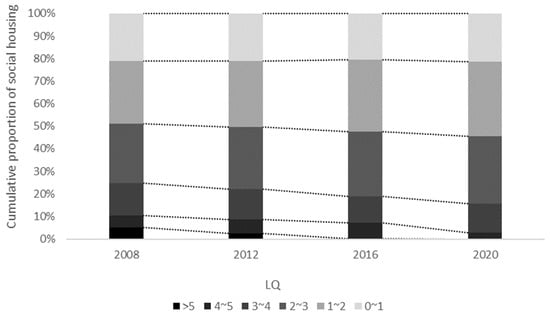

Following the spatial autocorrelation analysis, another issue to be examined is the extent to which social housing is concentrated in different urban zones. The LQ outputs were classified into five grades using the Jenks natural breaks classification method, illustrating the spatial concentration of social housing in different subdistricts (Figure 5). The patterns in 2008, 2012, 2016, and 2020 are presented to explain the changing process.

Figure 5.

Location quotients for social housing in 2008 (a), 2012 (b), 2016 (c), and 2020 (d).

Darker colors (higher LQ) are subdistricts with higher concentrations of social housing while lighter colors (lower LQ) imply a lower clustering of social housing. Figure 5 shows that the subdistricts with the lowest LQs (0–0.45 in 2008, 0–0.69 in 2012, 0–0.53 in 2016, and 0–0.47 in 2020) were in the central city, west of Huangpu River, as well as radically extending to the outskirt zone in 2008. In subsequent years, these low LQ subdistricts obviously reduced. Compared with that in 2008, the number of subdistricts with high concentration of social housing (LQ > 2.27 in 2008, LQ > 2.67 in 2012, LQ > 2.01 in 2016, and LQ > 1.92 in 2020) increased in the outskirt zone through 2012, 2016, and 2020. It would be an absolute even spatial pattern if all the LQs across the whole study area were 1. In this period of the government’s policy preferences on social housing, the suburban and outskirt zones witnessed a substantial increase in subdistricts with LQs around 1 (interval between 0.45 and 1.24 in 2008, 0.69 and 1.62 in 2012, 0.53 and 1.21 in 2016, and 0.47 and 1.12 in 2020). In the comparison of LQ associated values in different study years, the max value drops from 6.63 to 4.85; both the mean and median values are approaching 1 (1.27→1.31→1.27→1.24; 0.76→0.95→0.97→0.95); and the standard deviation gradually decreases from 1.35 to 1.10 (Table 3). In summary, the spatial pattern in social housing in Shanghai became more even in the period from 2008 to 2020.

Table 3.

The comparison of LQ associated values from 2008 to 2020.

The concentration profiles proposed by Poulsen, Johnston, and Forrest can be summarized as follows: if large numbers of one group are concentrated in spatial units with high proportions of that same group, then this group tends to be segregated, while, if the most are found in spatial units with low percentages of the same group, then this group is relatively dispersed [49,58]. Based on this idea, we used the ratio of social housing in spatial units with a different LQ to the total social housing to present the respective concentrations of social housing in different study years. In Figure 6, fewer darker segments through these years show that the proportions of social housing in highly concentrated spatial units have decreased, which indicates that social housing has become relatively dispersed over time.

Figure 6.

Percentages of social housing found in subdistrict units with a different LQ from 2008 to 2020, Shanghai.

4.3. Socioeconomic Characteristics in Areas with Different Levels of Social Housing Agglomeration

Table 4 shows the quartile scores of the socioeconomic indicators of two types of regions, namely, regions with a high concentration of social housing and regions with a low concentration of social housing. Among these, the high-concentration regions are defined as those with an LQ higher than 1, and the low-concentration regions are those with an LQ lower than 1. In order to test whether there is a significant difference in the distributions of urban resources and populations in relation to the concentration levels of social housing, the Mann–Whitney U test is employed to test each set of socioeconomic characteristics. The U test is a non-parametric test, and the null hypothesis is that there is no significant difference between the two sets of data with regard to social housing agglomeration levels.

Table 4.

The estimation of socioeconomic characteristics in low- and high-concentration subdistricts.

The model results show that there is an obvious difference between urban areas with different social housing agglomeration levels in terms of socioeconomic characteristics. Firstly, in terms of demographic characteristics, the U test reveals that areas with a high concentration of social housing tend to have a larger proportion of young and middle-aged people, as well as a larger percentage of people without Hukou. In contrast, areas with a low concentration of social housing tend to have a higher share of elderly residents and local residents. Moreover, areas further away from the urban center are associated with a high concentration of social housing. In these areas, the density of road networks, residents, and urban facilities, such as metro stations, bus stations, parks, healthcare facilities, schools, commercial facilities, and entertainment facilities, is relatively low. In addition, areas where social housing is concentrated have lower housing prices and rent prices. In comparison, there appear to be no disparities in terms of land prices for different social housing agglomeration areas, probably due to various types of allocated land, such as industrial land, green land, and highway land. Finally, despite the large percentage of social housing in the high concentration areas, the total quantity of urban housing in total is much lower than that in low-concentration areas.

5. Discussion

Based on the research contained herein, it appears that those low-to-moderate income populations in urban China present a concentration pattern at the citywide level, not just concentrated into several types of neighborhoods, as previous studies indicated [18,20,23,45,48]. In 2008, a great deal of social housing was distributed at the southern boundary of central Shanghai, in the districts of Minhang, Pudong, and Xuhui, about 15 km away from the urban center. Additionally, a high concentration of social housing also emerged in Baoshan, Qingpu, Songjiang, and Chongming, the suburban and outskirt zones. Despite the existence of poverty concentration at the citywide level, suburbanization and deconcentration emerged in the period from 2008 to 2020, when the local authority offered policy preferences for the housing security system. Compared with 2008, the year 2020 witnessed the movement of a large quantity of social housing towards south and east, from the boundary of central city to the suburban and outskirt zones. Over these years, the spatial concentration patterns in social housing in Shanghai seemed to become more and more homogeneous. However, our findings furthermore reveal that those areas with a high concentration of social housing also share the characteristics of being far from urban center, having low access to urban facilities, and having a high proportion of migrant populations and young people. In other words, although the spatial distribution of low-to-moderate-income groups tends to be more even, they have not obtained equal urban resources; rather, they are concentrated in relatively poor areas with few urban amenities in a dispersed pattern.

We offer a speculative elucidation of this process and the outcome. The poverty concentration at the neighborhood level in Chinese cities during the 1990s can be attributed to China’s housing allocation system stemming from the planned economy era: mixed social groups lived in work unit compounds, regardless of their ranks [46,49,70]. However, the implementation of housing system reforms and the commercialization of the housing market have brought about significant changes. The marketization of urban housing has enticed investments and newly emerged affluent households toward regions with high land value and convenient urban amenities in the urban center. Meanwhile, individuals with pre-existing institutional privileges, such as Hukou, have also been able to maintain their residence in the urban core [71,72]. Consequently, low-income and non-local residents have been compelled to relocate from the once socially diverse neighborhoods. They have involuntary clustered at the boundary of central city and in suburban regions. This massive ‘gentrification’ process triggered by urban renewal has also manifested in other Chinese cities [50,72]. From a governmental perspective, the Shanghai municipal government, like many other Chinese cities, once heavily relied on land-leasing fees as a source of local revenue. Therefore, there were limited incentives for the provision of social housing before 2008. As a result, social housing was predominantly concentrated in suburban regions where land prices were lower so as to minimize the opportunity cost in land-based revenues. In the Chinese context, the construction of social housing is basically a top-down process, and policy plays the most crucial role in it. Before 2008, the housing security system in Shanghai mainly consisted of CRH, and since then gradually developed into a ‘Four in One’ system (Four types of social housing (CRH, ECH/SOH, PRH, RH/CPH) in one housing security system) [73]. This multi-level housing security system and the associated multi-sourced social housing have accommodated more low-to-moderate-income populations. Since 2008, in response to the central government’s housing market regulations, the Shanghai municipal government has implemented various policies aimed at controlling speculation and strengthening social housing provisions (Table 5). These policies indicate that local authorities placed greater emphasis on the quantity of social housing rather than their locations, albeit with some vague regulations. For example, there are terms in ‘Guidelines for the construction of social housing in Shanghai (Trial)’ regulating that ‘newly built social housing shall be in locations with good environment, convenient transportation, convenient urban amenities, and safe geological conditions’. However, specific regulations are absent. While the integration of social housing into commercial housing developments allowed for a more favorable distribution throughout the city, the quantity remained limited (according to the response to the Deputy of the People’s Congress (https://fgj.sh.gov.cn/bljg/20230516/2b79b6bbdfff472aa3f39d5ee99e2108.html, accessed on 26 November 2023): from July 2010 to December 2022, about 3.37 million square meters of social housing equipped as commercial housing was constructed, and the number of units was 51 thousand), and priority was still given to the suburbs. Therefore, the gradual spatial dispersion of social housing between 2008 and 2020 was primarily driven by the extensive construction of social housing in areas that previously had few residential compounds. It is a unique phenomenon that emerged in urbanizing cities, in which social housing has expanded to broader regions but without commensurate development of urban amenities.

Table 5.

Policies about social housing.

In the global context, both the purpose and the consequence of deconcentrating poverty are to promote social integration and reduce spatial inequality by moving poor households to regions that had no over-representation of poverty in the past, especially those neighborhoods with a better environment and less poverty [36,37,74,75,76]. In contrast, our study shows that social housing has relocated but not to better places with more urban resources for the residents. Instead, social housing has still been in remote, cheap, and inconvenient locations in the city, as some scholars suspected [77,78]. The social segregation still exists and the social equality that is expected to emerge following poverty deconcentration is also absent.

6. Conclusions

This study employs multiple approaches to understanding the spatial distribution and concentration patterns in social housing in Shanghai from 2008 to 2020, as well as the socioeconomic characteristics of areas with different levels of social housing agglomeration. We will now answer the three questions addressed earlier. First, the findings of our study indicate clustered patterns in social housing, implying a concentration of low-to-moderate-income groups at the citywide level. Second, in the period 2008–2020, social housing was distributed in a more even pattern, spreading gradually from the boundary of central city to the suburban and outskirt zones. Third, the deconcentration and suburbanization of social housing have not truly promoted social equality. In this process, low-to-moderate-income groups living in social housing have relocated to places that originally had few residents, rather than places with moderate-to-high-income populations and affluent urban resources. This might be a result of local policies’ ignorance of locations in the construction of social housing, despite the preference toward their quantities, and the mismatch between the construction of social housing and urban amenities.

At present, there is no policy particularly aimed at deconcentrating poverty in China, but it is necessary. Experiences from other countries, especially the American cities, demonstrated that policies such as housing vouchers help in the deconcentration of urban poverty [35,39]. Based on Shanghai’s evidence, Chinese municipal governments could introduce measures, such as tax incentives for real estate developers, or rental discounts for low-income populations, to facilitate the construction of social housing together with commercial housing or provide poor populations with more opportunities to move into neighborhoods with better urban resources. Additionally, local government should both specify regulations on site selections for social housing in policies and construct urban amenities in broader regions of the city. For example, the outskirt zones including Jiading, Qingpu, Jinshan, Fengxian, Chongming, and Baoshan are expected to benefit from more green space, as well as transport, education, healthcare, commercial, and entertainment facilities. Moreover, in the construction of social housing, public opinion should be generally taken into consideration in order to promote the quality of housing.

Finally, although Shanghai is a representative metropolis of China, the situations regarding social housing construction and urban low-to-moderate-income groups might be different from that in other provinces or cities. In the future, we can select panel data from other cities, such as Nanjing, Wuhan, or Lanzhou, to study the phenomenon of poverty concentration. This research series is expected to build a bigger picture with regard to housing for poor populations in urban China.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, Y.L. and X.F.; methodology, Y.L.; software, Y.L.; validation, Y.L. and X.F.; formal analysis, X.F.; investigation, Y.L.; resources, Y.L.; data curation, X.F.; writing—original draft preparation, Y.L and X.F.; writing—review and editing, Y.L. and X.F.; visualization, Y.L.; supervision, X.F.; project administration, Y.L. and X.F.; funding acquisition, Y.L. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by the project ‘A Research from the Perspective of Urban Managerialism on the Morphological Evolution of Residential Space and its Mechanism in the Central Urban Area of Shanghai’ (grant number 52008295) from National Natural Science Foundation of China.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

The data presented in this study are available on request from the authors.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Parker, K.F.; Pruitt, M.V. Poverty, poverty concentration, and homicide. Soc. Sci. Q. 2000, 81, 555–570. [Google Scholar]

- Orford, S. Identifying and comparing changes in the spatial concentrations of urban poverty and affluence: A case study of inner London. Comput. Environ. Urban Syst. 2004, 28, 701–717. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Quillian, L. Segregation and Poverty Concentration: The Role of Three Segregations. Am. Sociol. Rev. 2012, 77, 354–379. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- UN-Habitat. The State of African Cities 2014 Re-Imagining Sustainable Urban Transitions; UN Habitat: Nairobi, Kenya, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Allard, S.W. Places in Need: The Changing Geography of Poverty; Russell Sage Foundation: New York, NY, USA, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Farrel, C.A.; Fleegler, E.W.; Monuteaus, M.C.; Wilson, C.R.; Christian, C.W.; Lee, L.K. Community Poverty and Child Abuse Fatalities in the United States. Pediatrics 2017, 139, e20161616. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Guo, Y.; Chang, S.; Sha, F.; Yip, P.S.F. Poverty concentration in an affluent city: Geographic variation and correlates of neighborhood poverty rates in Hong Kong. PLoS ONE 2018, 13, e0190566. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tong, X.; Kim, J.H. Concentration or diffusion? Exploring the emerging spatial dynamics of poverty distribution in Southern California. Cities 2019, 85, 15–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Poku-Boansi, M.; Amoako, C.; Owusu-Ansah, J.K.; Cobbinah, P.B. The geography of urban poverty in Kumasi, Ghana. Habitat Int. 2020, 103, 102220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Massey, D.S. The age of extremes, Concentrated affluence and poverty in the twenty-first century. Demography 1996, 33, 395–412. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Massey, D.S.; Fischer, M.J. How segregation concentrates poverty. Ethn. Racial Stud. 2000, 23, 670–691. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharkey, P. The Intergenerational Transmission of Context. Am. J. Sociol. 2008, 113, 931–969. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Howell, A.J.; Timberlake, J.M. Racial and Ethnic Trends in the Suburbanization of Poverty in U.S. Metropolitan Areas, 1980–2010. J. Urban Aff. 2014, 36, 79–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Owens, A. Housing Policy and Urban Inequality: Did the Transformation of Assisted Housing Reduce Poverty Concentration? Soc. Forces 2015, 94, 325–348. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Freedman, M.; McGavock, T. Low-Income Housing Development, Poverty Concentration, and Neighborhood Inequality. J. Policy Anal. Manag. 2015, 34, 805–834. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pathak, R.; Wyczalkowski, C.K.; Huang, X. Public transit access and the changing spatial distribution of poverty. Reg. Sci. Urban Econ. 2017, 66, 198–212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Petrović, A.; Manley, D.; Ham, M.v. Multiscale Contextual Poverty in the Netherlands: Within and Between-Municipality Inequality. Appl. Spat. Anal. Policy 2022, 15, 95–116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, G.; Gu, C.; Wu, F. Urban poverty in the transitional economy: A case of Nanjing, China. Habitat Int. 2006, 30, 1–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, S.; Liu, Y.; Wu, F.; Webster, C. Poverty incidence and concentration in different social groups in urban China, a case study of Nanjing. Cities 2008, 25, 121–132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, F. The State and Marginality: Reflections on Urban Outcasts from China’s Urban Transition. Int. J. Urban Reg. Res. 2009, 33, 841–847. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Delang, C.O.; Lung, H.C. Public Housing and Poverty Concentration in Urban Neighbourhoods: The Case of Hong Kong in the 1990s. Urban Stud. 2010, 47, 1391–1413. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, F.; He, S.; Webster, C. Path dependency and the neighbourhood effect: Urban poverty in impoverished neighbourhoods in Chinese cities. Environ. Plan. A 2010, 42, 134–152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, S.J.; Wu, F.L.; Webster, C.; Liu, Y.T. Poverty Concentration and Determinants in China’s Urban Low-income Neighbourhoods and Social Groups. Int. J. Urban Reg. Res. 2010, 34, 328–349. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gong, J.; Wang, G.; Wang, Y.; Zhao, Y. Consumption and poverty of older Chinese: 2011–2020. J. Econ. Ageing 2022, 23, 100410. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Z.; Wu, F. Socio-spatial Differentiation and Residential Inequalities in Shanghai: A Case Study of Three Neighbourhoods. Hous. Stud. 2006, 21, 695–717. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, L.; Huang, Y.; Zhang, W. Residential segregation and perceptions of social integration in Shanghai, China. Urban Stud. 2018, 55, 1484–1503. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shen, J.; Xiao, Y. Emerging divided cities in China: Socioeconomic segregation in Shanghai, 2000–2010. Urban Stud. 2020, 57, 1338–1356. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Madden, J.F. Changes in the Distribution of Poverty across and within the US Metropolitan Areas, 1979–1989. Urban Stud. 1996, 33, 1581–1600. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Holloway, S.R.; Bryan, D.; Chabot, R.; Rogers, D.M.; Rulli, J. Exploring the effect of public housing on the concentration of poverty in Columbus, Ohio. Urban Aff. Rev. 1998, 33, 767–789. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Joassart-Marcelli, P.; Wolch, J.; Alonso, A.; Sessoms, N. Spatial Segregation of the Poor in Southern California: A Multidimensional Analysis. Urban Geogr. 2005, 26, 587–609. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cooke, T.; Marchant, S. The Changing Intrametropolitan Location of High-poverty Neighbourhoods in the US, 1990–2000. Urban Stud. 2006, 43, 1971–1989. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Glaeser, E.L.; Kahn, M.E.; Rappaport, J. Why do the poor live in cities? The role of public transportation. J. Urban Econ. 2008, 63, 1–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Galster, G.; Zobel, A. Will dispersed housing programmes reduce social problems in the US? Hous. Stud. 1998, 13, 605–622. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Crump, J. Deconcentration by Demolition: Public Housing, Poverty, and Urban Policy. Environ. Plan. D Soc. Space 2002, 20, 581–596. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oakley, D.; Ward, C.; Reid, L.; Ruel, E. The poverty deconcentration imperative and public housing transformation. Sociol. Compass 2011, 5, 824–833. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Walter, R.J.; Li, Y.; Atherwood, S. Moving to Opportunity? An Examination of Housing Choice Vouchers on Urban Poverty Deconcentration in South Florida. Hous. Stud. 2015, 30, 1064–1091. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McClure, K.; Schwartz, A.F.; Taghavi, L.B. Housing Choice Voucher Location Patterns a Decade Later. Hous. Policy Debate 2015, 25, 215–233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wyly, E.; DeFilippis, J. Mapping Public Housing: The Case of New York City. City Community 2010, 9, 61–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Patterson, K.L.; Yoo, E.E. Trapped in Poor Places? An Assessment of the Residential Spatial Patterns of Housing Choice Voucher Holders in 2004 and 2008. J. Soc. Serv. Res. 2012, 38, 637–655. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kneebone, E. The Changing Geography of US Poverty. 2016. Available online: https://www.brookings.edu/testimonies/the-changing-geography-of-us-poverty/ (accessed on 10 December 2023).

- Lees, L.; Slater, T.; Wyly, E. Gentrification; Routledge: London, UK, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Ades, J.; Apparicio, P.; Séguin, A.M. Are new patterns of low-income distribution emerging in Canadian metropolitan areas? Can. Geogr./Le Géographe Can. 2012, 56, 339–361. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khan, M.M.; Hotchkiss, D.R.; Berruti, A.A.; Hutchinson, P.L. Geographic aspects of poverty and health in Tanzania: Does living in a poor area matter? Health Policy Plan. 2006, 21, 110–122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Katumba, S.; Cheruiyot, K.; Mushongera, D. Spatial Change in the Concentration of Multidimensional Poverty in Gauteng, South Africa: Evidence from Quality of Life Survey Data. Soc. Indic. Res. 2019, 145, 95–115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.; Wu, F. Urban poverty neighbourhoods: Typology and spatial concentration under China’s market transition, a case study of Nanjing. Geoforum 2006, 37, 610–626. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fang, C.; Zhang, X.; Fan, S. Emergence of urban poverty and inequality in China: Evidence from household survey. China Econ. Rev. 2002, 13, 430–443. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yuan, Y.; Gu, Y.; Chen, Z. Spatial differentiation of urban poverty of Chinese cities. Prog. Geogr. 2016, 35, 195–203. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Chen, G.; Gu, C.; Wu, F. Spatial Analysis of Urban Poverty in Nanjing. Sci. Geogr. Sin. 2004, 24, 542–549. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Johnston, R.; Poulsen, M.; Forrest, J. Ethnic and racial segregation in U.S. Metropolitan areas, 1980–2000: The dimensions of segregation revisited. Urban Aff. Rev. 2007, 42, 479–504. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, W. Tenure-Based Housing Spatial Patterns and Residential Segregation in Guangzhou under the Background of Housing Market Reform. Sustainability 2022, 14, 4567. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Apparicio, P.; Séguin, A. Measuring the Accessibility of Services and Facilities for Residents of Public Housing in Montréal. Urban Stud. 2006, 43, 187–211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, Q.; Li, Q.; Yue, Y.; Zhuang, Y.; Chen, Z.; Kong, H. Exploring changes in the spatial distribution of the low-to-moderate income group using transit smart card data. Comput. Environ. Urban Syst. 2018, 72, 68–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ong, R.; Phelps, C.; Rowley, S.; Wood, G.A. Spatial and Temporal Patterns in Housing Supply: A Descriptive Analysis. Urban Policy Res. 2018, 36, 287–303. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cui, C.; Mu, X.; Chang, H.; Li, J.; Wang, F. Patterns and determinants of location choice in residential mobility: A case study of Shanghai. Prog. Geogr. 2021, 40, 422–432. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Suen, I. Residential Development Pattern and Intraneighborhood Infrastructure Provision. J. Urban Plan. Dev. 2005, 131, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, W.; Shen, G.; Wang, H.; Lombardi, P. Critical issues in spatial distribution of public housing estates and their implications on urban renewal in Hong Kong. Smart Sustain. Built Environ. 2015, 4, 172–187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mansour, S. Spatial concentration patterns of South Asian low-skilled immigrants in Oman: A spatial analysis of residential geographies. Appl. Geogr. 2017, 88, 118–129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liao, B.; Wong, D.W. Changing urban residential patterns of Chinese migrants: Shanghai, 2000–2010. Urban Geogr. 2015, 36, 109–126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, C.; Li, C.; Wang, M.; Yang, S. Transnational migrants in Shanghai: Residential spatial patterns and the underlying driving forces. Popul. Space Place 2019, 26, e2272. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jeon, G.; Jung, S. Comparative analysis of residential patterns of foreigners from rich and poor countries in Seoul. Sustain. Cities Soc. 2019, 47, 101470. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moran, P.A.P. The interpretation of statistical maps. J. R. Stat. Society. Ser. B 1948, 10, 243–251. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anselin, L. Local indicators of spatial association—LISA. Geogr. Anal. 1995, 27, 93–115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rovolis, A.; Tragaki, A. Ethnic characteristics and geographical distribution of immigrants in Greece. Eur. Urban Reg. Stud. 2006, 13, 99–111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Flegg, A.T.; Tohmo, T. Regional input-output tables and the FLQ formula: A case study of Finland. Reg. Stud. 2013, 47, 703–721. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nelson, P.B.; Nelson, L.; Trautman, L. Linked migration and labor market flexibility in the rural amenity destinations in the United States. J. Rural. Stud. 2014, 36, 121–136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morrissey, K. Producing regional production multipliers for Irish marine sector policy: A location quotient approach. Ocean. Coast. Manag. 2014, 91, 58–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaygalak, I.; Reid, N. The geographical evolution of manufacturing and industrial policies in Turkey. Appl. Geogr. 2016, 70, 37–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Andresen, M.A. Location quotients, ambient populations, and the spatial analysis of crime in Vancouver, Canada. Environ. Plan. A 2007, 39, 2423–2444. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Isard, W. Methods of Regional Analysis: An Introduction to Regional Science; MIT Press: Cambridge, USA, 1960. [Google Scholar]

- Fang, Y.; Liu, Z.; Chen, Y. Housing inequality in urban China: Theoretical debates, empirical evidences, and future directions. J. Plan. Lit. 2020, 35, 41–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Z.; Wu, F. Tenure-based residential segregation in post-reform Chinese cities: A case study of Shanghai. Trans. Inst. Br. Geogr. 2008, 33, 404–419. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fang, Y.; Logan, J.R.; Pal, A. Emerging socio-spatial pattern of Chinese cities: The case of Beijing in 2006. Habitat Int. 2015, 47, 103–112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shi, J.; Li, J. Research on Shanghai housing security policy effect based on the evaluation method of prospect theory. Syst. Eng.-Theory Pract. 2019, 39, 89–99. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Williamson, A.R.; Smith, M.T.; Strambi-Kramer, M. Housing Choice Vouchers, the Low-Income Housing Tax Credit, and the Federal Poverty Deconcentration Goal. Urban Aff. Rev. 2009, 45, 119–132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bailey, N.; Minton, J. The suburbanisation of poverty in British cities, 2004–2016: Extent, processes and nature. Urban Geogr. 2018, 39, 892–915. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McClure, K.; Schwartz, A.F. Neighbourhood opportunity, racial segregation, and the Low-Income Housing Tax Credit program in the United States. Hous. Stud. 2023, 38, 1459–1481. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, Y. An institutional and governance approach to understand large-scale social housing construction in China. Habitat Int. 2018, 78, 96–105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, F.; Zhang, X.; Wang, J. Spatial Distribution and Forming Characteristic of Affordable Housing in Urban Central Area. Shanghai Urban Plan. Rev. 2023, 5, 79–85. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).