2. Cultural Heritage and Culture-Led Development

At the Convention for the Safeguarding of the intangible cultural heritage, ratified in 2003, ICH was defined as “the practices, representations, expressions, knowledge, skills—as well as the instruments, objects, artefacts and cultural spaces associated therewith—that communities, groups and, in some cases, individuals recognize as part of their cultural heritage” [

6] (p. 5). The ICH dimensions identified at the Convention are “(a) oral traditions and expressions, including language as a vehicle of the intangible cultural heritage; (b) performing arts; (c) social practices, rituals and festive events; (d) knowledge and practices concerning nature and the universe; (e) traditional craftsmanship” [

6] (p. 5). The United Nations World Tourism Organization explicitly added music under performing arts in 2012 and identified a new ICH dimension, namely gastronomy and culinary practices [

16].

Cultural heritage is a tool for strengthening identity [

2,

17] and sustaining local cultural diversity in the face of the homogenizing context of European belonging [

18]. The members of local communities are the main connoisseurs and promoters of cultural heritage [

19], which is kept alive and developed only through the involvement of locals [

20]. Traditional knowledge conveyed by heritage is learned. It is a long-lasting process that involves crediting the knowledge of previous generations along with inter-generational relations [

2].

During the last decade, European cultural policies show a growing interest in the sustainable dimension of culture and in efficient cultural management. As a result, the focus has shifted from the preservation of cultural heritage and common cultural identity to the decisive role of heritage in socio-economic development [

21]. Educating young Europeans to share the cultural identity has gained political stakes in the EU [

22], and cultural management has been acknowledged as a pillar for sustainable regional development [

23].

The dynamics of cultural heritage is noticeable in the influence of the dimensions of sustainable development, i.e., social, economic and environmental [

2]. A sustainable community is characterized by “cultural vitality”, namely by the ability to recognize its cultural values, preserve them in the long run and “use culture and history to advance societal learning” [

24] (p. 59).

Cultural heritage is a valuable resource for the policies and actions of culture-led development. Culture-led development [

25] is a concept that like many others such as cultural mapping [

26], sustainable culture [

27], cultural resilience [

28], creative tourism [

29], and arts-based development [

30] defines the relations between culture and local sustainable development promoted nowadays.

The speeches promoting those relations highlight the importance of the specific characteristics of places, communities and societies that are the cornerstone of research endeavors [

31]. Cultural resources catalyze the interactions within communities, thus generating an “enhanced sense of community and greater well-being” [

30] (p. 237), while improving life quality [

32]. They are considered a guarantee of sustainable development [

26]. Cultural heritage is acknowledged as an important resource of cultural resilience [

28] and revitalization of the rural environment [

31].

Thus, the direct beneficiaries of heritage management are local communities. The decisions on the selection, conservation and presentation of heritage resources are of direct interest to local people, businesses, public administration and politicians, since they should be the result of participatory practices [

17]. Awareness of the importance of authenticity reduces the divergence between heritage conservation and tourism value community wise. In this context, heritage tourism programs focusing on aspects that communities value as authentic are sustainable [

33].

3. Digital Communication and the Revitalization of Cultural Heritage

The wide access to the Internet in recent decades has opened interest in using the online environment for the management of cultural heritage resources. Many communities have chosen the digital description of heritage resources, as well as the dissemination of information on local culture and history via individual social media accounts [

26]. Concerning the process of bringing cultural heritage online, the terms “digital heritage” and “digitisation of heritage” have emerged. Digital heritage encompasses cultural heritage resources that have been made in this format from the new and existing cultural heritage resources that have been digitized [

34]. With the help of new technologies (such as 3D laser scanning, computer simulation or holographic imaging), digital heritage can include a multitude of dimensions, “archaeological sites, architectural monuments, intangible heritage like folk traditions, cultural relics, ancient books and museums, and creative art products with digital content (…) building clusters (palaces, temples, residential houses) and gardens” [

35] (p. 340). These can be effectively showcased with the support of augmented reality [

36,

37], virtual tours and exhibitions, 3D restorations, various online events, games and other applications [

36].

The “digital revolution” has generated important changes in both cultural production and consumption [

38]. Cultural heritage institutions are increasingly using digital heritage and social media facilities to engage with heritage custodian communities. Thus, with the help of museums, libraries, archives or historical societies, a new ecosystem of memory in which communities are encouraged to share their collective remembrances [

39] is configured. Digitizing cultural collections and local histories increases the chance of preserving them over time [

28]. On the other hand, websites promoting tourist destinations are essential communication tools in the international tourism market and are constantly under pressure to identify new strategies to increase the attractiveness of what it has to offer [

40]. The possibility of accessing cultural heritage on websites or social networks broadens what there is to offer in heritage tourism. Moreover, it meets the interest of the diaspora “in finding records of themselves or of their family links” [

28] (p. 466), and in genealogical tourism. For local communities, such touristic interests provide development opportunities. Nevertheless, Knapik and Krol [

41], in their study on Polish rural digital cultural heritage, consider it to be a less-known part of heritage. This is the case for Romanian rural cultural heritage, too. Its main embodiment is the promotion of agritourism and rural tourism in the online environment. In this context, rural digital cultural assets can be considered digital artefacts created in rural areas and are characteristic of them [

42].

Digital heritage is helpful in the conservation, maintenance, and promotion of real-world 3D heritage sites or assets. Digital heritage conservation requires a different approach, due to the unique requirements that concern access, reusability, and preservation [

43]. Thus, the employment of technology and digitization in different organizations supposes to establish and sustain digital repositories. In the field of organizations with responsibilities for cultural preservation, such as mayors, there are repositories of cultural heritage artifacts. These repositories operate as software-as-a-service in order to enhance the accessibility and appreciation of cultural heritage, securely storing, displaying, and sharing cultural artifacts [

44]. Digital databases can be used for conservation, communication and sustainable development [

45]. The digital protection of cultural heritage through traditional methods incurs a low information retrieval rate and a long processing time. Therefore, new digital methods based on web technology are needed [

46]. An important issue concerns the legal framework of the rules of digital technologies for the reproduction, use and preservation of cultural heritage content. Already, in 2011, the EU Commission admitted the urgent need for protection and preservation of the European cultural heritage by issuing the “Commission Recommendation on the digitisation and online accessibility of cultural material and digital preservation” (2011/711/EU) [

47]. Thus, efforts to digitize and digitally preserve cultural heritage are present all over Europe. The willingness of European Commission’s to support the digitization of cultural heritage is to be seen in the launch of a Collaborative Cloud for Europe’s cultural heritage, which will be developed under Horizon Europe, the EU research and innovation programme (2021–2027) [

48]. The Cloud is supposed to be the digital infrastructure that will connect cultural heritage institutions and professionals across the EU, contributing in this way to the vision and objectives of the Commission.

For example, the Greek approach to digitization relies on the conviction that the comprehensive protection of monuments is achieved when they are brought out of isolation and integrated into citizens’ lives as an organic part of their everyday life [

49]. In Poland, rural digital artefacts are records of ICT, infrastructure, environmental, cultural, and socioeconomic changes [

50]. Outside the EU space, efforts are made regarding the digitization of cultural heritage and its protection by law. In Albania for example, although tourism based on cultural heritage is an important part of the economy, the use of digital technologies is still weak [

51].

4. Făgăraș Land: Some Historical Landmarks

Făgăraș Land lies between the Făgăraș Mountains and the Olt River (

Figure 1), in Central Romania.

The Voivodeship of Făgăraș is an ancient Romanian state formation, attested in 1222 as Terra Blachorum. According to traditional sources, the first ruling dynasty of Wallahia, the Romanian voivodeship beyond the Carpathian Mountains to the south, originates here. The legendary founding voivode is Radu Negru. He crossed the mountains with some of his subjects having been defeated by the armed forces of the expanding Hungarian Kingdom. Beginning with the end of the 13th century, when Făgăraș Land was under the control of the Hungarian Kingdom, the administrative status of the county changed several times throughout history. A few times, it was offered in a feud to the Wallachian rulers and, depending on their relations with the Hungarian kings, taken back.

It was under royal ownership, a district offered to Universitas Saxonum (during the reign of King Matthias Corvinus), then a free territory owned by a powerful local Romanian nobleman (after the defeat of Hungary at Mohács in 1526), or property of the princes of Transylvania or of the Habsburg monarchy (by the Leopoldine Diploma of 1691). After that, it was part of the Military District of Sibiu (after the 1848 Revolution); next, it was included in the principality of Transylvania, which united with Hungary in 1865 [

52], and then it became part of the Romanian state after 1918.

On top of these changes in its political-administrative status, it was also marked by several dramatic historical events: invasions by the Tatars [

53], punitive incursions organized by Vlad Țepeș, ruler of Wallachia, in southern Transylvania [

54], the campaign to impose Catholicism under Empress Maria Theresa and the anti-communist resistance movement in the Făgăraș Mountains, followed by the communist persecution of the movement’s local supporters.

The donations made by the Wallachian voivodes in the XIV century contributed to the rise of the first ethnic Romanian boyars in the Făgăraș Land. Later, serfs were ennobled as a reward for their services in defending the Făgăraș Fortress, while much later, in the 17th century, the title of nobility could be purchased [

38]. In 1762 the border guards received land for their military services to the Habsburg Empire.

The numerous changes in the political-administrative status of Făgăraș Land, the dramatic events the inhabitants of the area had to outlive throughout history and the existence of local noble land owners in the Romanian communities contributed to the shaping and consolidation of the cultural identity of Făgăraș Land. In addition, during the interwar period (1929 and 1938) Dimitrie Gusti, the leader of the Sociological School in Bucharest, conducted his field research in the area. The interest showed towards the locals at the time still echoes in the self-representation of their descendants. The dwellers of Făgăraș Land have a strong feeling of belonging and take pride in it [

55]. The latter encapsulates all types of local resistance to the vicissitudes of history.

5. Materials and Methods

Four years ago, a research team, of which three of the authors of this article were part, conducted a project called

CarPaTO: Mapping the intangible cultural heritage of Făgăraș Land (2018–2019). During the aforementioned endeavor, intangible cultural heritage (ICH) resources were identified in the 16 ATUs of Făgăraș Land, which belong to the administrative county of Brașov. The research data showed the existence of an abundance of ICH resources [

56,

57]. Therefore, we formulated the question of whether this abundance is presented and promoted by the local authorities as part of their digital communication on the official websites belonging to the town halls of the ATUs included in our research. That is, we wanted to systematically analyze how local administrations communicate about ICH “to a local, national or even an international audience” [

58] (p. 6) through their official websites.

In order to attain this objective, we conducted a content analysis. Content analysis, which can be quantitative or qualitative, is often employed in conducting research on the sites of various institutions. A research project based on content analysis identifies the types of online resources used in the universities in Lithuania to present the idea of sustainable development [

59]. A similar research endeavor focuses on management approaches in Romanian universities [

60]. Content analysis of specialized official sites is also used to answer important questions related to promoting touristic attractions such as how local cultural sites can be promoted internationally [

40] (p. 164), the most adequate marketing strategies of touristic offices related to halal cuisine and hospitality [

61], or the means by which Portuguese municipalities promote local tourism on their official sites in direct correlation with assumed identities [

4].

Our content analysis included three stages. First, we identified the ICH-related information on the websites of the ATUs and organized it by categories, thus developing a coding scheme (

Table 1). Some ATUs did not present any ICH-related information on their official websites; therefore, in the second stage, we selected the websites that had ICH-related information and quantified the data based on a content analysis model recommended by Brancati (2018) [

62] (

Table 2). More specifically, once the measures and indicators were established according to the methodological model mentioned above, we explored each website individually, identified all the information related to ICH and organized it in a table, after which we counted the contents according to the established indicators. The results of these identification and counting procedures are presented in

Table 3 and

Table 4. Finally, during the third stage, we analyzed and interpreted the research data in order to gain a coherent image of how these official websites relay information on ICH.

The research presented in this article continues our work conducted four years ago, proposing a longitudinal perspective on digital communication about ICH. By analyzing the current data on the websites of town halls and using the same type of content analysis as four years ago, we aim at examining whether there are changes in the digital communication of ICH data. The administrative units of our study were all the 16 ATUs that are geographically part of the Făgăraș Land, but administratively belong to Brașov County, Romania. The same ATUs were also the subject of research in the CarPaTO project, which is frequently referred to in this article, as well as of the first content analysis we conducted in 2019.

Our research question was to examine the change in the online communication of information about local ICH on the official websites of the 16 municipalities, four years after our first research study on the same topic, during which time humanity has experienced a pandemic and significant changes in digitization have taken place. In addition, we focus on identifying new forms of communication about this type of heritage, based on our 2019 observation, according to which, some of the communicative content of community interests is transferred to social media. Thus, starting on 10 November and finishing on 1 December 2023, we conducted a new content analysis using the same coding scheme and the same manner of quantifying data. It is worth noting that we added an indicator related to video contents (I2.4), and we replaced the indicator I4.1 referring to the similarities in the design of town halls’ websites with the indicator focusing on the number of ATUs with similar content on their different Facebook pages (I4.1f).

In conducting the content analysis, our concern was to collect mainly numerical data that would allow us to use the measures and indicators, according to the methodological model presented above. However, in analyzing and interpreting the data, we also took into account qualitative information, such as the ICH categories proposed by UNESCO and WTO. Also, in analyzing the visual data (photographs with ICH-related content) we considered the same categories.

The COVID-19 pandemic occurred between 2019 and 2023, and it reshaped identities, behaviors, identities and interests [

15] all over the world. Furthermore, the pandemic highlighted the importance of digital communication in general, and of social media in particular. The comparison of the contents related to ICH on the websites of the town halls before and after the pandemic, together with the identification of references to ICH on the Facebook pages of the town halls, should indicate the alignment of the ATUs of Făgăraș Land to the trend of valorizing online communication generated by the pandemic restrictions.

The research we conducted was exploratory and descriptive. Since we analyzed a small number of cases (16), but which covered all the ATUs in the target area, we did not formulate hypotheses; however, we had two assumptions or expectations, thus, we expected to find two important changes in online communication about ICH: an increase in the value of the indicators used in the analysis during the period under review and the emergence of new forms of online communication about ICH, in particular, a migration of communication to social media. In the chapter dedicated to the discussion of the results, we will show how these expectations have been confirmed by the data.

6. Results

In 2019, 12 of the 16 websites we analyzed contained information on ICH. In 2023, the number of ATUs displaying information on ICH on their websites increased to 14. On the main page of the website, the button that most frequently gives access to the aforementioned information is the one that provides a general overview of the ATU (in seven of the cases in 2019, respectively, in eight of the cases in 2023), but there are also other buttons such as: Tourism, Public Announcements, Culture, Sights or Photo Gallery. In 2019, information about ICH was available under distinct sections such as Traditions (most frequently), History, Events, and Culture. In 2023, the names of the sections with information about ICH diversified, including new names such as: Local Events, Tourism and Economy, News and Cultural Events, Customs and Traditions, Traditional Products, as well as names of local institutions or events, such as the Village Museum, the Festival of the Lads’ Groups, Holidays Show, the Festival of the Soul of the Village, Traditional Weddings, etc.

In 2019, on the four sites that contained no information about ICH, there were still buttons for sections called Culture, Tourism or Heritage, but they displayed no information or referred only to natural tourist sites. In 2023, on the two websites where in 2019 there was no information on ICH, the situation remained the same. We also noted that none of the websites we analyzed in 2019 or in 2023 included a special section named “Intangible cultural heritage”.

In relation with the websites containing information on ICH, we conducted content analysis based on some criteria proposed by Brancati [

62]: size, counts, location, and similarity. For each of these criteria, we used specific indicators (

Table 3). Both in 2019 and 2023, we used counting techniques for the size, counts, and location criteria, and for the similarity criterion, we compared the design of the websites and the way information about ICH was arranged to determine whether there was a unified structure of online communication about ICH [

58].

The table below contains numerical data corresponding to measures I1.1–I3 for each of the ATUs that had information about ICH on their websites, as well as ICH categories (as defined by UNESCO and UNWTO) about which the websites provided information. For those ICH categories, we used the following abbreviations: (a) oral traditions and expressions—OTE; (b) performing arts and music—PAM; (c) social practices, rituals, and festive events—SPRE; (d) knowledge and practices concerning nature and the universe—KNU; (e) traditional craftsmanship—TC; and (f) gastronomy and culinary practices—GCP.

The results are presented in a systematic way, analyzing each measure individually, with the related indicators, according to the analysis scheme in

Table 2.

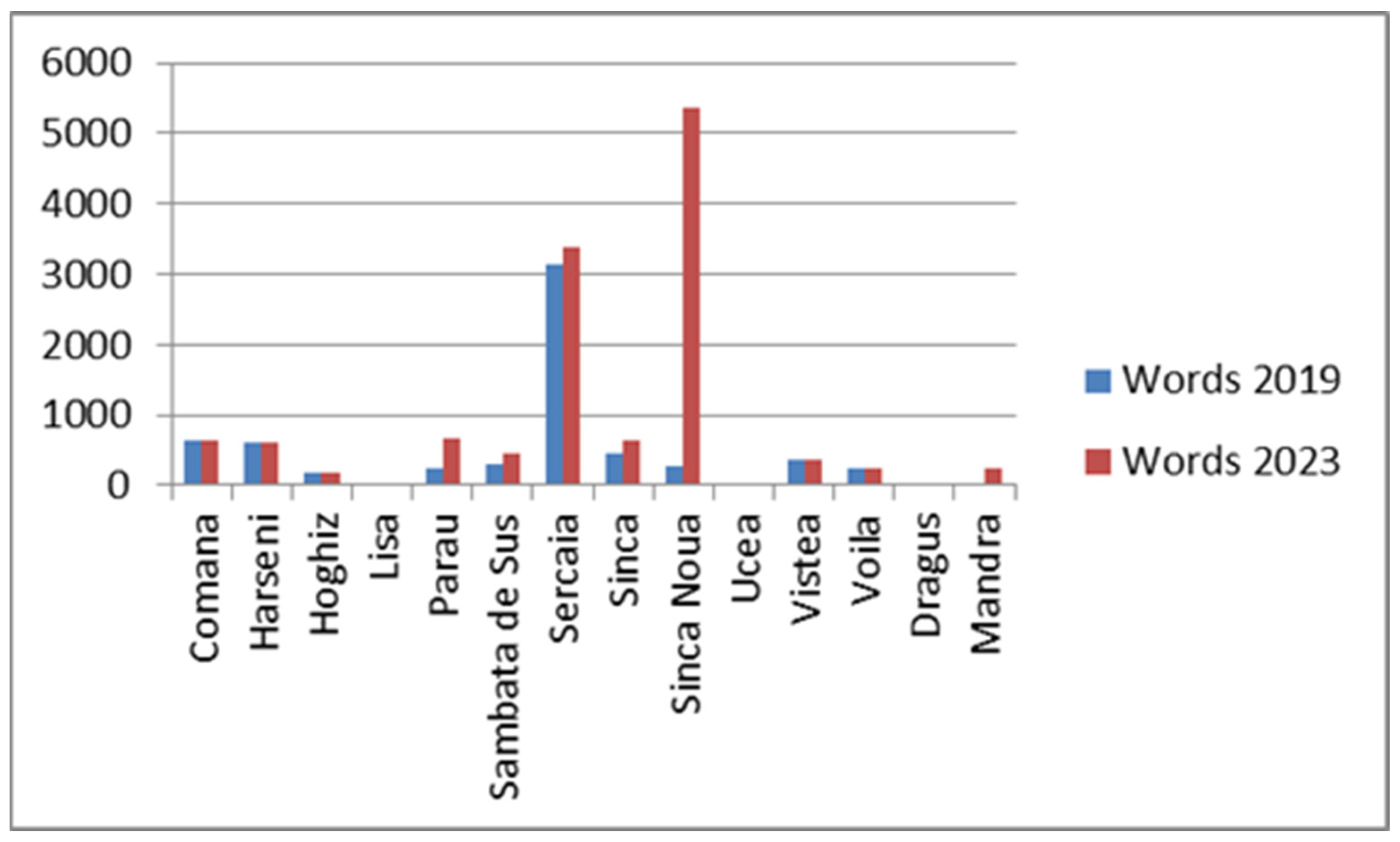

6.1. Measure M1: Size

As regards the length of the texts about local ICH (I1.1), in 2019, we recorded a variation from 19 to 3139 words. The longest texts we found were on the websites of Șercaia (3139), Comăna (647), and Hârseni (608) ATUs, and the shortest texts were on the websites of Hoghiz (190), Lisa (27), and Ucea (19) ATUs. In 2023, the variation was from 20 to 5365 words, which demonstrates that the amount of information on ICH increased. The longest texts were on the websites of Șinca Nouă (5365), Șercaia (3376), and Părău (664) ATUs, while the shortest texts were on the sites of the ATUs of Ucea (35), Lisa (30), and Drăguș (20). The evolution over the period analyzed for indicator I1.1 can be seen in the diagram below (

Figure 2):

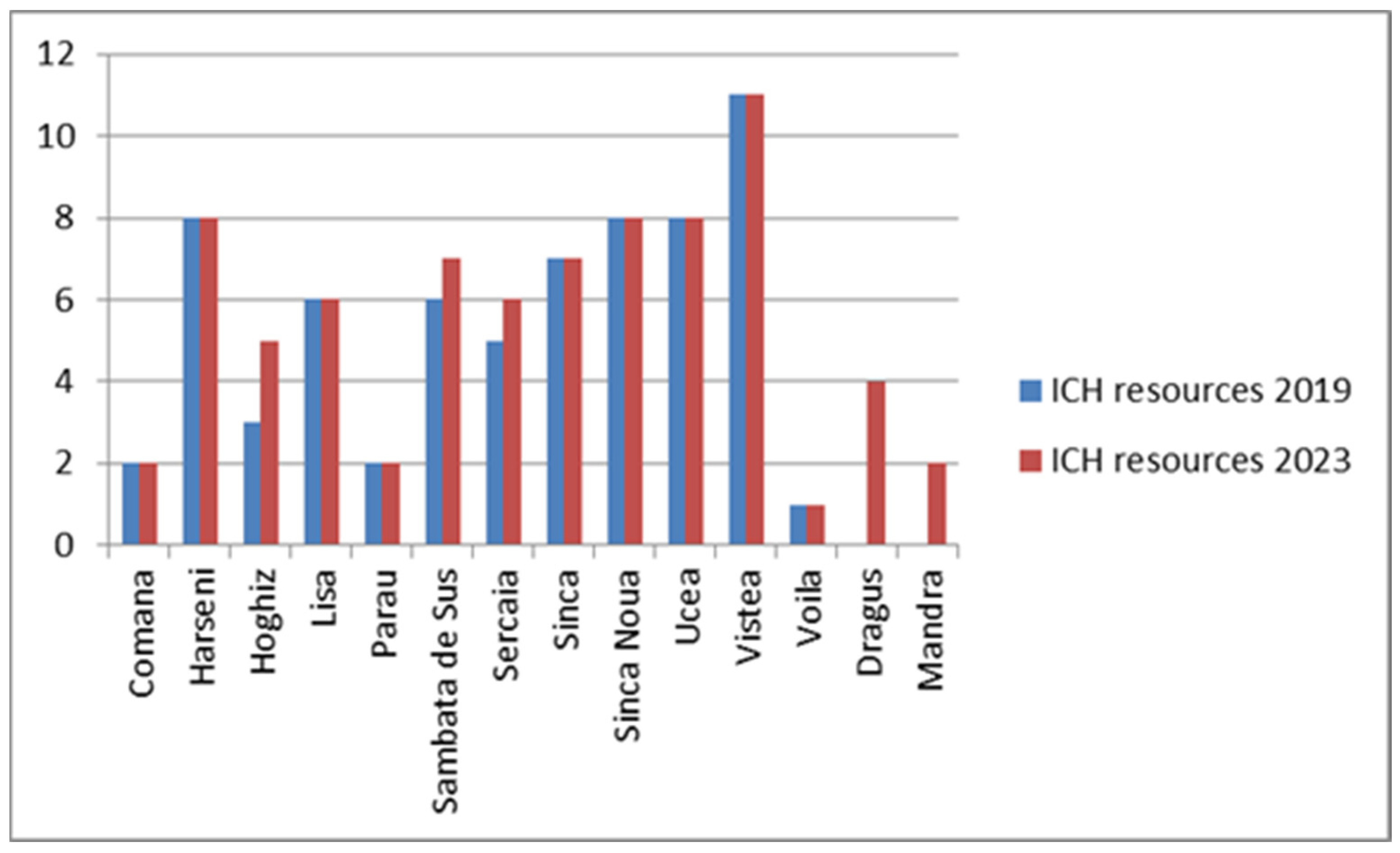

It is worth noting that the website of Șinca Nouă included 12 links to national and international cultural events where the Folk Ensemble of the ATU had participated. Thus, compared to 2019, two new ATUs rank among the top three, while two of the ATUs that were also there in 2019 are in the last three positions. Drăguș is one of those last three, with its website containing little text but plenty of visual information. Moreover, with very few exceptions, the number of distinct local resources on ICH (I1.2) remains the same, varying from 1 (Voila) to 11 (Viștea). In the diagram below (

Figure 3), these data are visually presented.

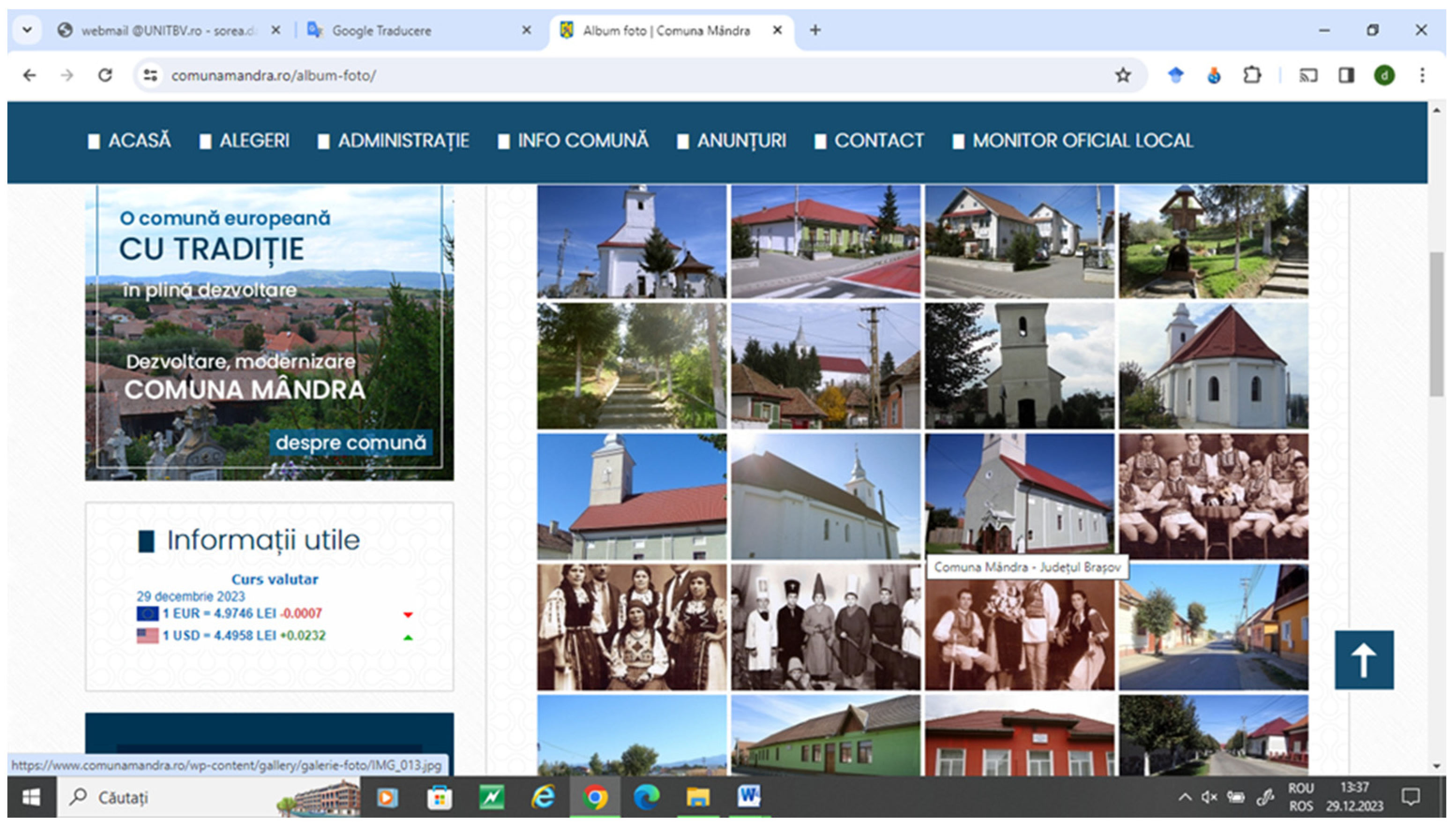

Three of the ATUs analyzed in 2019, namely Hoghiz, Sâmbăta de Sus and Șercaia, added one type of ICH resource in the information posted on their websites, whereas the two ATUs that enrich the list of websites containing information on ICH, Mândra (

Figure 4) and Drăguș (

Figure 5), respectively, mention two or four local ICH resources.

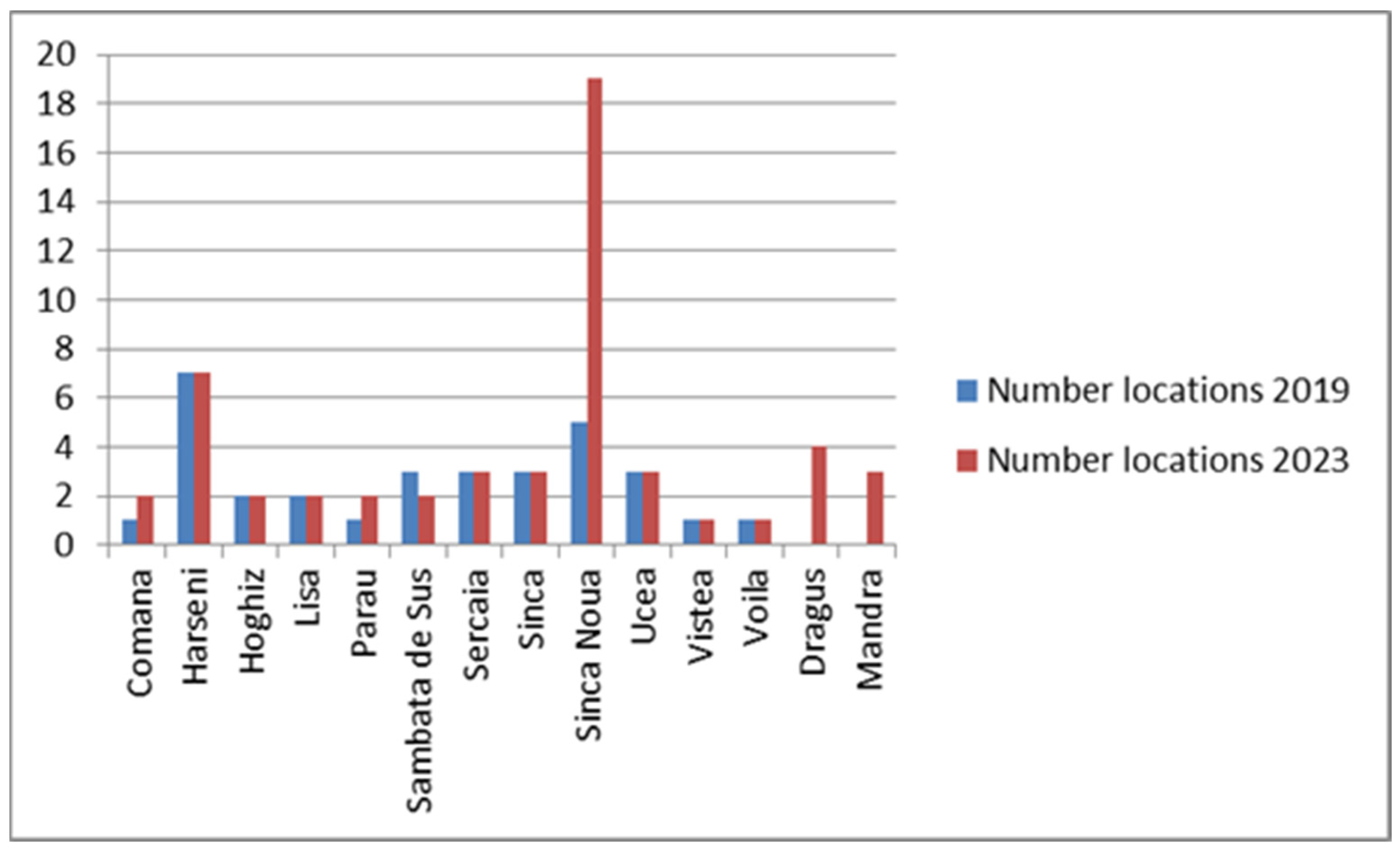

6.2. Measure M2: Counts

In 2019, the number of online locations with information about ICH (I2.1) ranged from 1 to 7, with an average of 2.6 locations. We found information in a single location in four cases (the ATUs Comăna, Părău, Viștea, and Voila) and in seven different locations in the case of one ATU (Hârseni). In 2023, this indicator varied from 1 to 19, with an average of 3.8 locations. We found information in a single location in only two cases (Viștea, and Voila) and in 19 different locations on the website of Șinca Nouă. Data on the number of locations and their evolution over the period analyzed are shown in

Figure 6.

In 2019, we found the word “heritage” (I2.2) only twice: in the case of Hârseni and Șinca Nouă. In 2023, the frequency of the word slightly increased in the case of the websites of four ATUs—three mentions in the case of the ATUs of Părău and Șercaia, and one mention on the websites of Hârseni and Șinca Nouă.

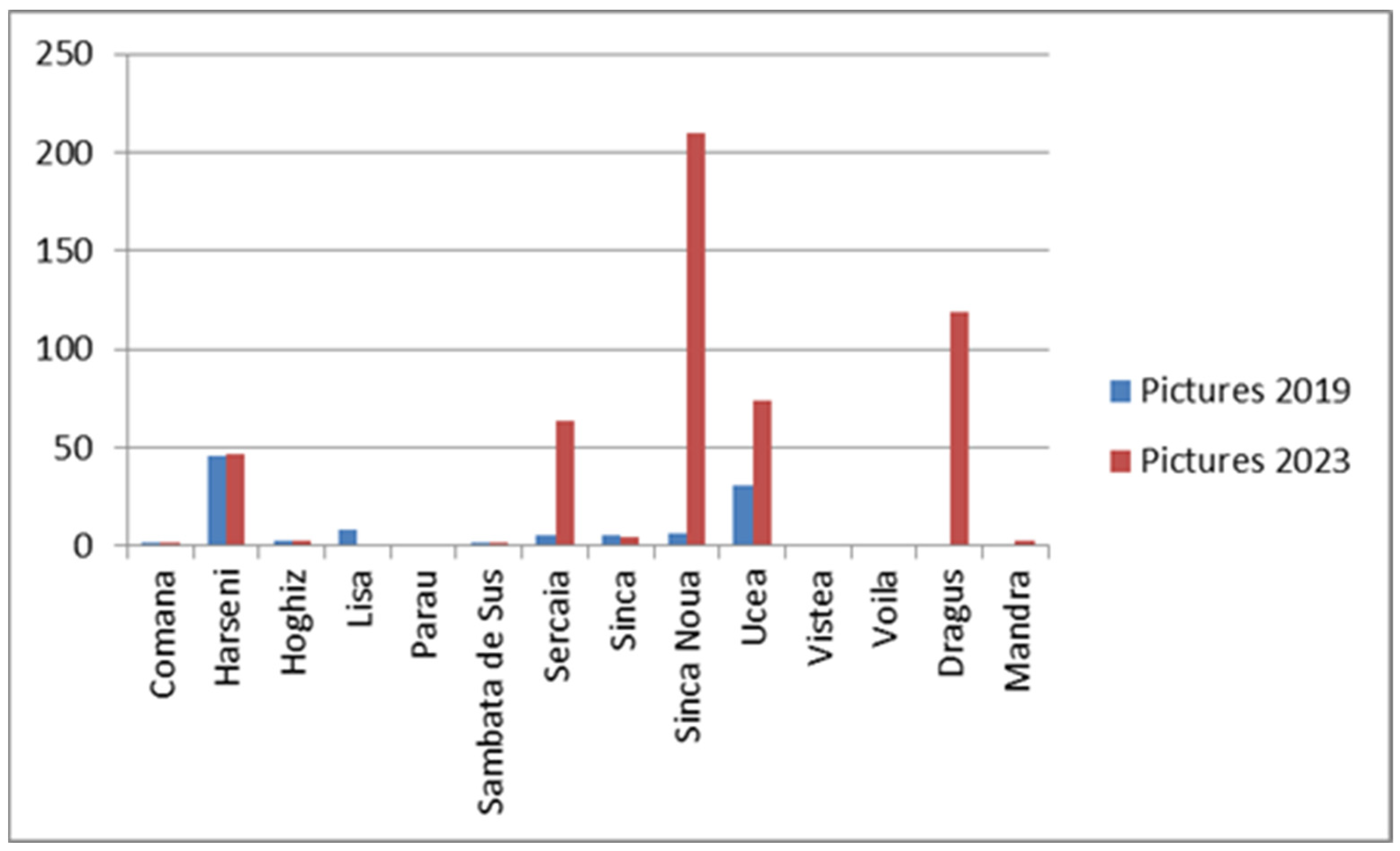

Regarding the visual data (I2.3), both in 2019 and in 2023, most websites contained pictures illustrating different forms of ICH resources, but in some cases, without explanations for what each picture represented. In 2019, three websites (Părău, Viștea, and Voila) had no pictures, and the others had a number of pictures ranging from 2 (Comăna and Sâmbata de Sus) to 46 (Hârseni), with an average of 9 pictures per website. In 2023, the situation of the three ATUs with no photos on their websites remained the same, while the variation on the sites including photographs increased: from 1 in the case of Lisa to 210 in the case of Șinca Nouă. Furthermore, the average also increased to 37.7 photographs per website. The diagram below (

Figure 7) contains a visual representation of the data on the number of photos about ICH posted on websites, corresponding to indicator I2.3.

6.3. Measure M3: Location

Similar to our endeavor in 2019, gaining access to information on ICH on the websites we analyzed was quite easy. The ICH content was retrieved by a maximum of two clicks. However, since this type of information is not organized under just one heading, the users must retrieve it from under several sections. In our content analysis, we navigated to all pages of the site to identify all information referring to ICH. The I3 measure was quantified by the maximum number of clicks by which users can access all the information on ICH available on the website starting from the home page. We noted a variation from 1 (in the case of the ATUs Comăna, Părău, and Voila) to 14 in the case of Hârseni, with an average of 3.7 clicks in 2019. In 2023, the variation ranged from 1 in the case of Voila and Sâmbăta de Sus to 19 for Șinca Nouă. The average was 4.5 clicks, slightly higher compared to the 2019 average.

6.4. Measure M4: Similarity

In relation to the similarities among the websites (I4.1), the situation remains unchanged compared to 2019. Thus, no website looks like another. Indicator I4.1 represents the number of websites with a similar design. In both 2019 and 2023, the value of this indicator was zero, which shows a wide heterogeneity of online communication about ICH [

44]. Measure I4.2, representing the maximum number of websites which contain references to the same type of ICH resource, had the same value (I4.2 = 12) in 2019 and 2023. All 12 of the websites had information about the specific groups of lads in their communities.

In the third phase of our analysis, we discussed the results, taking into account both the theoretical framework and the results obtained in the CarPaTO project, as well as in the content analysis undertaken four years ago. Both in 2019 and 2023, we found that the information displayed on the official websites of the town halls in Făgăraș Land covered the UNESCO and UNWTO categories of ICH unevenly. For example, in 2019, there was no information at all about gastronomy and culinary practices (GCP), and in 2023, only the website of Drăguș ATU displayed such information. Both in 2019 and 2023, the most present category of ICH was social practices, rituals, and festive events (SPRE). The twelve websites that contained information on ICH in 2019 also displayed materials about winter holidays. In 2023, the situation was the same: the same 12 of the 14 websites displayed information on the cultural events connected with winter holidays such as The Throw in the Blanket (which literally means the ritualistic throwing up and catching of a young man by the other young men in a blanket), Small Plough (a ritual practice of agricultural communities, wishing for wealth in the coming year), The Star (a group of children announcing the Nativity, caroling through the village with a decorated wooden star), the Herods (a short folk play about Herod’s infanticide, performed by caroling boys), and The Group of Lads (organized group of caroling lads).

Our research in 2023 also included analysis of the Facebook pages of the town halls of the 16 ATUs. This was based on our 2019 observation that a significant part of digital communication on ICH is made via social media. The table below (

Table 4) contains data on the information on ICH present on the Facebook pages of the town halls of the ATUs we analyzed in 2023.

Thus, for 2023, we first researched whether the ATUs included in our analysis had a Facebook page. We noticed that 8 of them, that is, half of the 16 ATUs, owned at least one such page. Some pages were officially acknowledged by the town halls, whereas in the case of the others, they mentioned that they were not official pages. We focused on measuring approximately the same indicators as in the case of the websites. The data obtained are presented as follows: the number of words related to ICH varies from 75 to 1398; the number of local resources presented ranges from 1 to 13; the number of locations (such as events, posts, photos, etc.) varies from 1 to 15; the word “heritage” appears in the case of two ATUs; the number of photographs ranges from 1 to 429, and the videos—which is a new element that is not on the websites—varies from 1 to 21; and the number of clicks to access the information on ICH ranges from 1 to 4.

Compared to websites, for the indicator referring to similarities, we analyzed whether the same ATU had similar information on its different Facebook pages and validated the assumption in the case of four ATUs (I4.1f = 4). As for the similarity of the Facebook pages of the various ATUs, we observed that the same event was presented on several Facebook pages. Such references were made in relation to the Festival of Lad Groups from Făgăraș Land, which was mentioned on the Facebook pages of all ATUs in the area under investigation (I4.2 = 8). Moreover, similar to websites, the most frequent ICH category was SPRE (social practices, rituals, and festive events).

The two ATUs recently included in the list of those displaying information about ICH on their official websites were under scrutiny with ample research. The results are presented in the form of two case studies that are relevant for the new means of preserving, retrieving, promoting and digitizing ICH.

6.5. New Perspectives on Digital Communication about ICH: Social Media and the Digitization of Heritage in Drăguș and Mândra: Two Case Studies

6.5.1. Case Study 1: Drăguș

The Drăguș ATU presents an interesting sociological history [

65] and a multitude of cultural resources. It aims at preserving and promoting its immaterial cultural heritage via social media platforms, Facebook mostly, as well as through a new website that provides information on traditions, cultural events and tourism. Besides the data gathered in the field during the CarPaTO project (2018–2019), we obtained information and a wider perspective on how the Drăguș ATU manages its cultural heritage and communicates about the latter via semi-structured interviews (9) with representatives of the ATU and citizens. The interviews were conducted by one of the authors of this article in the spring of 2021, and the data indicate that social media platforms, Facebook in particular, as well as the official website of the ATU are viewed as essential tools for promoting information about heritage and local cultural activities. They offer a direct communication means with the members of the community and people from the outside. One relevant aspect is the active Facebook page of the ATU by the name of “Drăguș Commune” (

Figure 8) where memories and materials about the community are posted, thus contributing to the preservation and promotion of traditions. Besides the Facebook account, there is also a group whose members promote ICH: “Drăguș—folklore, traditions, people, images and not only”. The group manages a virtual space dedicated to socialization and the preservation of collective memory. Even though there are efforts to modernize the official website of the town hall, there is a discrepancy between information available on the website, which is pretty scarce and mostly visual, and the information on Facebook, which is more diverse and numerous. However, the public administration from Drăguș started a website dedicated to cultural heritage and tourism, thus offering an exclusive means to promote those resources both to the local community and people from the outside. The website indragus.ro was launched in 2022 and is administered by the town hall of Drăguș. Its goal is to promote traditions, the customs of local producers and the touristic activities from Drăguș, offering information on events, traditions, gastronomy, “Dimitrie Gusti” Ethnographic Museum, tourism, as well as sports activities characteristic for the area. According to the interview data, in Drăguș, the technological evolution is well received by the community, and the various age groups adapt and use the Internet and social networks.

Even though the Draguș ATU is making progress in digitizing ICH, some vulnerabilities in this endeavour are also highlighted. The discrepancy between the information provided on the official website and that available on social media platforms indicates a lack of consistency in the management of online communication, which can affect credibility for visitors and the local community. In addition, the absence of an integrated communication strategy may diminish the impact of efforts to promote cultural heritage. Therefore, careful planning and coordination between online communication sources is necessary to avoid confusion and to deliver a consistent and accurate message to the public.

Another vulnerability is related to the limited and predominantly visual information presented on the official website of the municipality. This limitation affects the ability to provide relevant and substantive details about ICH. Therefore, constant updating and diversification of content would increase the effectiveness of the site.

6.5.2. Case Study 2: Mândra

Mândra ATU gained visibility nationally and internationally once the Museum of Canvas and Stories (

Figure 9) was created. The latter is a cultural center started as a family project dedicated to people, heritage and stories of the place, coordinated by Alina Zară. In two houses in the village, the museum hosts collections of canvas, old dowry items displaying local features, collections of stories in various forms (text, photos, postcards, volumes, exhibitions, etc.) and functions as a multifunctional space that retrieves, researches, preserves and promotes local cultural identity through its projects. The Mândra Chic workshops are already well known in Romania and in the Romanian diaspora, where contemporary dowry pieces are created and meant to soothe the homesickness of those who emigrated.

The museum also hosts free-of-charge projects and workshops dedicated to the children and adults of the community, environmental and civic campaigns, guided tours, an international travel project—Mother Ruța’s Spool around the world—and, more recently, the project #Garaj30—a collection of objects and local stories dating back to Communist times. Alina Zară was interviewed by one of the authors of the article at the beginning of December 2023. According to her, she is “a mix of a cultural entrepreneur and storyteller”. According to her: “As a cultural entrepreneur I can call myself a heritage retriever who reestablishes local cultural identity. As a storyteller, I capitalize on the oral history of Mândra based on 60 interviews and thus I obviously retrieve an important part of the immaterial cultural heritage. In the end, all of those, can be captured by the phrase of digital creator. However, I rather consider myself an enthusiastic researcher based on what I have retrieved from the cultural heritage, namely an ethnographic collection of Mândra area that reflects its cultural identity, as well as stories that bring forgotten arts and crafts back to the community”. Through what the Museum of Canvas and Stories of Mândra represents, but also through the intense activity of recovering forgotten crafts such as weaving and lace making, it is clear that a significant contribution to what we can call the recovery of the intangible heritage and the transmission of crafts, from one generation to the other, is being made. This recovery, however, “must not exclude the actual recovery of heritage. I am referring here to the recovery of lost crafts, which must be restored to the community so that it understands first of all the significance of the folk costume, but also the way in which such a costume is woven (restoration of textile heritage). If a community does not understand the meaning of the symbols, then an important part of the cultural heritage is lost, in fact the cultural identity specific to each area is lost.”

An example of a recently started project promoted via social media is the Warp of Ages. It is deemed a “courageous project aiming at retrieving almost lost traditional crafts- such as weaving and lace-making, giving them back to the community and reintroducing them in the creative routine of rural life as a contribution to the local development of the area: a creative ecosystem focusing on textile heritage that would give communities back the confidence and strength of the past” [

68].

The focus of ICH in the case of the museum in Mândra is on textile heritage, including through recovered crafts (weaving and lace making) and their stories. This perspective should be broadened so that more heritage components could be of interest for recovery. The Museum of Canvas and Stories is an ambitious project, which makes a significant contribution to the digitization of ICH and which should manage its status as a family project as well as possible.

7. Discussion

According to the results of the research conducted in 2019, online communication about ICH on the official websites of the town halls from Făgăraș Land lacks a coherent strategy. At the same time, it demonstrates an under-utilization of the resources of local cultural heritage in the online environment, even though Făgăraș Land has a unitary cultural identity and is an area with great potential. Hence, it can be considered an interesting Romanian and European “cultural landscape” [

69]. The research resumed four years later shows no significant changes. One obvious aspect is that a local coherent strategy on digital communication about ICH in Făgăraș Land is still missing. Such a strategy could highlight a narrative that would reflect the potential for development based on the cultural resources of this geographic and ethnographic area in Romania, as well as its identity [

4]. We noticed both in 2019 and 2023 that the communication strategies about ICH on town halls’ official websites are singular and very local, while the information posted is meant to notify people about various aspects of local identity. They are not integrated in a wider context, nor subsumed to international vision and policies on culture-based development.

The data gathered in 2023 through content analysis from the official websites of the town halls from Făgăraș Land show a slight increase in the number of official websites of town halls that include information on ICH, as well as in the quantity of textual and visual information on this type of heritage. In general, the textual information is descriptive, presenting some customs, traditions or local events in a manner similar to ethnographic texts or folklore textbooks. Nonetheless, the possible benefits ensuing from the contributions of cultural resources for local development are not mentioned. The focus is on the value of those resources as elements of local pride and identity. Additionally, the word “heritage” is mentioned very few times on those websites: on two websites in 2019 and on four websites in 2023.

Unlike 2019, some of the websites of some ATUs include links to local cultural events. This increases the possibility of users finding more information on ICH. However, in 2023, we noticed a significant increase in the number of photographs posted on sites. Thus, compared to a 9.0 average per site in 2019, in 2023, the average reached 37.7, which demonstrates interest in promoting visual data related to ICH.

The content and the type of ICH resources promoted by the photographs posted on websites are very diverse. Some websites (Viștea, Părău, Voila) had a lot of textual information about ICH, but they had no pictures, and the situation remained unchanged for four years in a row. Other websites contained many pictures placed in several locations (for example Hârseni); in other cases, despite the great number of photos, there was no additional information on the content and relevance of the images (Ucea, Drăguș).

The absence of a strategy to promote the ICH resources on the websites of the town halls in Făgăraș Land is demonstrated also by the great diversity in website design and the way the information on ICH is organized. Both in 2019 and 2023, we noticed that there was no similarity among the websites, their design or the information posted, all of which fell under the responsibility of the town halls. That was a surprising finding for us because, according to the data gathered in the field as a result of the CarPaTO project, back in 2018 and 2019, there was an abundance of ICH resources in Făgăraș Land, and local public administrations (for example, Viștea ATU) even started initiatives to promote such an abundance of ICH resource and hence, the cultural heritage of the area in a unitary and coherent manner. We therefore believe that the wealth of ICH resources does not seem to be sufficiently promoted via the official websites of the ATUs in Făgăraș Land. Additionally, compared to 2019, there is still no organization of information about ICH on these websites based on the UNESCO and UNWTO categories of ICH. The only exception is that of Șinca Nouă ATU. The information about ICH on its website is organized in a manner close to the internationally acknowledged ICH categories. In 2019, we posited that such a situation was considerably the result of vision and involvement in local culture-based development of the aforementioned ATU’s mayor. The same aspect was also noted in the case of two other ATUs—Viștea and Hârseni—whose websites included information about ICH, even though the information was not organized by the UNESCO and UNWTO categories.

We could not find any special section entitled “Intangible Cultural Heritage” neither in 2019, nor in 2023. That could indicate insufficient knowledge at a local level of the importance of the concept in international development policies [

58]. Furthermore, the formulation of the texts demonstrates that they target people from outside the community. They illustrate local narratives, according to which, the ATU is perceived as a unique scene or area whose historical and cultural identity must be preserved. The tourists are invited to admire traditions and everything that attributes identity to the area [

69]. However, the benefits ensuing from culture-based development identified by Markusen and Johnson [

32], their contribution to stronger communities and well-being [

3,

30] and subsequently, to the transformation of local ICH resources into authentic tourist resources are underrepresented. In our opinion, a town hall website that underlines the aforementioned elements would be more efficient in communicating about its cultural heritage online, rather than a website focusing on tourist attractions. In practical terms, that would mean organizing the information on websites in a clear taxonomical separation of ICH resources, as well as highlighting the two main functions underlying the conservation and promotion of local cultural heritage, namely attracting economic resources in the community or in the region, and, more importantly, contributing to bettering community life.

In relation to the first function, according to Piñeiro-Navala and Serra [

4], digital communication and digitization of ICH resources represents an efficient method to promote local cultural heritage. The Internet is essential for tourists who seek authentic destinations, as well as for the communities that want to promote cultural projects and tourist assets. The aforementioned authors indicate that in the case of Portugal, gastronomy is the main type of cultural resource promoted on the sites of municipalities. In our case, we could not find any reference to gastronomy on the websites analyzed in 2019, while in 2023, there was one mention, in the case of Drăguș, and two references for Drăguș and Părău on social media. Nonetheless, during the CarPaTo project when we conducted our field research, we identified a lot of valuable resources belonging to the gastronomic heritage of the communities that were included in our research [

56,

70]. In the context of a wider trend in the south of Transylvania to offer traditional products during festive brunches [

71] and as a result of encouragement on behalf of the state of small businesses similar to “small gastronomic points” [

72], the town halls could promote local gastronomy as an ICH resource on their websites, and thus reap immediate economic benefits for local producers and traders.

But local gastronomy, as an ICH resource, can be valued together with other resources, such as the Group of Lads, active during the winter holidays. The combination of the two resources configures local niche tourism with considerable potential for the annual return of tourists [

57].

Concerning the second function related to the conservation and promotion of cultural heritage, namely the betterment of community life, in 2019, we identified a paradoxical situation in the case of Drăguș. Even though the field research in the CarPaTO project showed the existence of a wealth of ICH resources in this commune, the town hall in Drăguș was among the four ATUs without ICH information on its website. However, the ATU had an active Facebook page, and its digital communication regarding cultural events and traditions had moved to social media, which, we argued at the time, could be a worthwhile alternative in terms of online communication about ICH both to the community and to external audiences [

58]. Subsequently, we noticed that other ATUs, such as Mândra, also had active Facebook pages. Hence, we decided to also conduct an analysis of the information about ICH posted via social media.

We did not identify any clear correlation between the interest for ICH demonstrated on the official websites of the town halls in Făgăraș Land or on the Facebook pages administered by those town halls. Șinca Nouă does not have a Facebook page. However, its website contains the richest references to ICH. Părău records the most significant activity related to ICH on its Facebook page and showed a significant increase in the amount on information on its website between 2019 and 2023. Comăna also demonstrates a consistent concern for ICH on its Facebook page, but the ICH-related content did not increase in the time period when we conducted our research. The Facebook page of Ucea contains a lot of information on ICH, even though its website is lacking in this respect. The town hall of Sercaia records a consistent amount of information about ICH both on its website and Facebook page. As for the last ATUs included in the list of those mentioning ICH on town hall websites, the Facebook page of Drăguș is very active, while its website content is very scarce, and Mândra ATU does not display any activities on Facebook, even though its website does contain some significant information.

Thus, concerning the relations between official websites and Facebook pages, they cover the whole spectrum between competition and mutual empowerment. What we find even more relevant than the diversity of these relations is that the ICH content as proof of the interest of the town halls in Făgăraș Land in terms of ICH was generally on the increase between 2019 and 2023. Thus, local administrations acknowledge the advantages of digital communication in alignment with the general trend generated by the COVID-19 pandemic in this respect.

Recognizing the advantages of digital communication and using related communication pathways highlight the importance of digitizing ICH to ensure sustainable development of local communities in Făgăraș Land.

These communities are in the process of embracing the digital component of their identity. Different reports on the opportunities for online communication of heritage resources point to the hesitation and circumspection but also to the enthusiasm that is inherent in the use of any new tool.

We are talking about a tool with which young people are much more familiar than older people in the rural communities of Făgăraș Land. This could lead to distortions, as the skilled users of the communication tool are different from the holders of the information about the valuable heritage. Using social media easily could become as or more important than the knnowledge of the beliefs, traditions, crafts or ancient practices of the community. The communicator could become, in the context of the different preferences for novelty of community members, the one who gradually imposes their own views on the community, thus affecting the transmission of heritage resources. For this reason, in line with the importance given by Baltà Portolés [

2] to the intergenerational dimension of cultural heritage management, we believe that it is necessary to involve community elders, with the status of advisors, in the management of the websites or social media accounts of municipalities.

7.1. Digitization as a Tool for Intergenerational Community Cohesion

As Burkey [

39] shows, cultural heritage institutions increasingly use social media platforms and initiatives to digitize heritage in order to interact with the communities that preserve heritage and access the content of their collective memory. There are several village museums in Făgăraș Land [

56], whose collections include a lot of traditional craftsmanship products revealing information about ICH categories such as social practices, rituals and local festive events, or about knowledge and practices concerning nature and the universe. It could be an easy endeavor to digitize those museum collections by employing young locals who either live in the area or come on holidays at their grandparents/relatives in the village as volunteers. Young people are accustomed to using the tools required for online communication, and the activities ensuing from the digitization process teaches them about the local ICH resources, thus consolidating their feeling of belonging to the community. Accessing the facilities for communicating heritage information in a digital format further opens the possibility of enriching museum collections with audio/video recordings of the elderly giving testimony on traditions, rituals and local crafts. Cultural heritage preservation involves inter-generational communication and relaying knowledge to young people, as Baltà Portolés [

2] indicates. Involving young people in digitizing the collections of small local museums and recording representative local informants is a means of communicating ICH information inter-generationally and is advantageous for all those involved.

Young volunteers could also be employed to improve the references to the ICH on town halls websites. Nonetheless, the specific requirements associated with safely accessing, using, supporting and sharing the materials from the digital archives [

43,

44] demand more rigorous and administrative support than the benevolent interest of young people on holidays could assure. Such support is or could become useful for town halls. It could be provided by institutions that have the overall vision and can responsibly and professionally administer the digitized information about ICH, thus capitalizing on their potential for supporting community identity and the sustainable development of local communities.

The possibility of online access to local cultural heritage resources supports genealogical tourism [

28]. It also has an important intergenerational component. Făgăraș Land is a tenderer destination in genealogical tourism for several categories of beneficiaries: the descendants of Transylvanians who left for America in the 19th century and the first part of the 20th century, the Saxons who chose to move to Germany at the end of the 20th century, or the descendants of Romanians who left to work abroad (Italy, Spain) in recent years. The digitization of ICH enhances their desire to temporarily return home.

7.2. Digital Communication and Digitization of ICH in the Cultural Landscape Făgăraș Land

The field research conducted as part of the CarPaTO project underlined the tendency, along with a number of community initiatives, to approach the culture of Făgăraș Land in a unitary manner. The content analysis of Facebook pages undertaken in 2023 highlighted similar references to the cultural events held in the area on the pages of several ATUs.

Făgăraș Land owns sufficient defining cultural features to be considered a cultural landscape [

55]. In this context, unitary and coherent management of all digitized ICH resources of Făgăraș Land is a sustainable approach. It converges with the common feeling of locals’ belonging to the cultural landscape of Făgăraș Land.

7.3. Involving Local Communities in the Digitization of ICH Resources

At the core of such a unified management of digitized ICH resources, as well as the digitization process, should be the ICH dimensions of the UNESCO classification with the WTO addition on gastronomy. The approach to these different dimensions implies different methods of collection, preservation and promotion, and even different specializations of the members of the digitization teams formed in the municipalities. Together with these teams, local heritage experts should work as advisors. Also, ethnographic specialists from cultural institutions, in particular from Brasov County, should work with the digitization teams. The role of these specialists is to guide the selection of representative resources and to signal cultural loans and dissemination.

In an area whose inhabitants are very protective towards their heritage resources, which they consider to be a source of pride, the fact that the digitization process can be carried out without removing artefacts from the household (e.g., old handmade clothing) is a great advantage. In these circumstances, digitization teams operating in the community are likely to receive widespread support.

A unified approach to the digitization process enables the identification and enhancement of local differentiation within the same heritage resource, with a stake in shaping community identities.

On the other hand, the need for differentiation, for a strict assumption of the heritage of the origin community, cannot be ignored in Făgăraș Land. It has deep historical roots and is a characteristic of communities with a strongly shaped identity. In this context, the diversity of design options for municipalities’ websites should be taken into account as a matter of fact. It should not be discouraged, but directed towards differentiated solutions with the same set of requirements, linked to the UNESCO and WHO dimensions of ICH. In this way, a unified approach to the digitization process would enhance differentiated solutions. The use of photographs, an upward trend signaled by our longitudinal research results, supports differentiated resolutions. Additionally, these differentiations invite the community to engage in highlighting their own resources. A competition for the best ICH section on the websites would also act as a catalyzer for interactive community ownership of heritage digitization.

Related to community involvement and the dimensions of ICH, as mentioned above, the research carried out in the CarPaTO project highlighted the richness of Făgăraș Land’s heritage resources in terms of gastronomy. Further research on the websites of the municipalities signaled very poor digital valorization of gastronomic heritage. Remedying this situation, i.e., programmatic development of sections dedicated to gastronomy on websites and social media accounts managed by local administrations, would arouse the interest and willingness of locals to get involved, especially local women, who have a long experience of cooking together [

57,

70].

8. Conclusions

Most of the local administrations in Făgăraș Land seem to be preoccupied with posting references to local ICH resources on their official websites. Most of the town halls which relay online information about ICH do not have a coherent strategy ensuing from a common concept of promoting the cultural identity of the entire area. Our research highlights a great diversity of means to present and capitalize on local ICH resources.

In response to the research questions about the evolution of online communication of ICH data and the adoption of new forms of communication, the results of the research we conducted show that between 2019 and 2023, there was a moderate increase, in terms of number (of municipalities) and quantity (of the ICH information conveyed), of ICH-related content on the official websites of Făgăraș Land municipalities, and in 2023, half of the area’s municipalities had official Facebook pages. Local administrations understood the importance of efficient digital communication, as well as the importance of social media for the community. Those aspects could become part of the beneficial lessons gathered during crisis situations, such as the COVID-19 pandemic, despite their dramatic constraints. As shown above, the moderate increase in ICH-related content on the websites of the municipalities is accompanied by a great diversity of local reports on social media facilities as complementary/convergent/competitive ways of communicating cultural heritage. This diversity suggests ongoing familiarity at a community level with social media tools.

Once the tools of digital communication are assumed, they could be better employed. On one hand, when analyzing ICH content on the websites of the town halls and comparing the results with those of the research conducted during the CarPaTO project [

42], we noticed that there was no correlation between the wealth of ICH and the information about ICH available online. On the other hand, we also observed that the messages about ICH targeted mostly outside users, namely tourists, to the detriment of potential internal users, namely community members. In the case of the latter, knowledge about ICH resources consolidates the identity of the community and contributes to local sustainable development. We consider that the main advantage of online communication and digitization of ICH resources in this area is the intergenerational transmission of heritage. They are an effective tool for linking ICH keepers with their young descendants. They may even represent the main opportunity for the preservation of ICH in an age of inevitable technology use in more and more aspects of culture.

Also in relation to the intergenerational transmission of ICH, its digitization opens up multiple possibilities for its presentation in the area’s primary schools. In Romania, some of the topics taught to schoolchildren are optional and proposed by each individual school. The accessibility of heritage resources makes them the subject of attractive topics, with generous possibilities for interactive approaches.

Better employment of town halls’ Facebook pages to promote and preserve ICH requires co-opting locals who are knowledgeable about the heritage for their administration. The space dedicated to ICH on the websites of the town halls can be better used by digitizing heritage and facilitating the access of all those taking an interest to the digital ICH archives. The cultural unity of Făgăraș Land suggests that a unitary approach to the digitization process of ICH in the area is efficient.

As long as ICH is an important resource for sustainable community development, there is a major stake in efficiently communicating information about ICH. The relay of information via social media and the digitization of ICH resources are means to making communication efficient. Therefore, we believe that they deserve full attention.

ICH digitization supports local community identity. As Balfour et al. [

30] show, cultural resources empower community-level interactions. They are guarantees of sustainable development [

26]. As we show in the opening part of our argument, the link between culture and sustainable development is widely highlighted in work dedicated to the topic [

25,

26,

27,

28,

29,

30]. In the logic of this connection, local and community specificity is of great importance [

31]. The digitization of ICH allows this specificity to be highlighted. It provides a generous background for future comparative research on heritage resources. In fact, the ease with which heritage information available in digital format can be accessed makes comparative research a very beneficial field for cultural studies.

At the same time, it allows and facilitates the comparative encounter of local cultural specificity with the European common cultural background, in the Cloud [

48]. Thus, the digitization of heritage provides additional ways of highlighting the unity in diversity, which is so important in defining Europe.