Autonomy Acquisition and Performance within Higher Education in Vietnam—A Road to a Sustainable Future?

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Data Envelopment Analysis (DEA)

2.2. Malmquist Productivity Change Measurement

2.3. DEA Model for Vietnamese Universities

2.4. Econometric Model Specification

3. Results

3.1. Autonomy Context and Some Figures of Vietnam Universities

3.2. Efficiency Analysis of Vietnam Universities

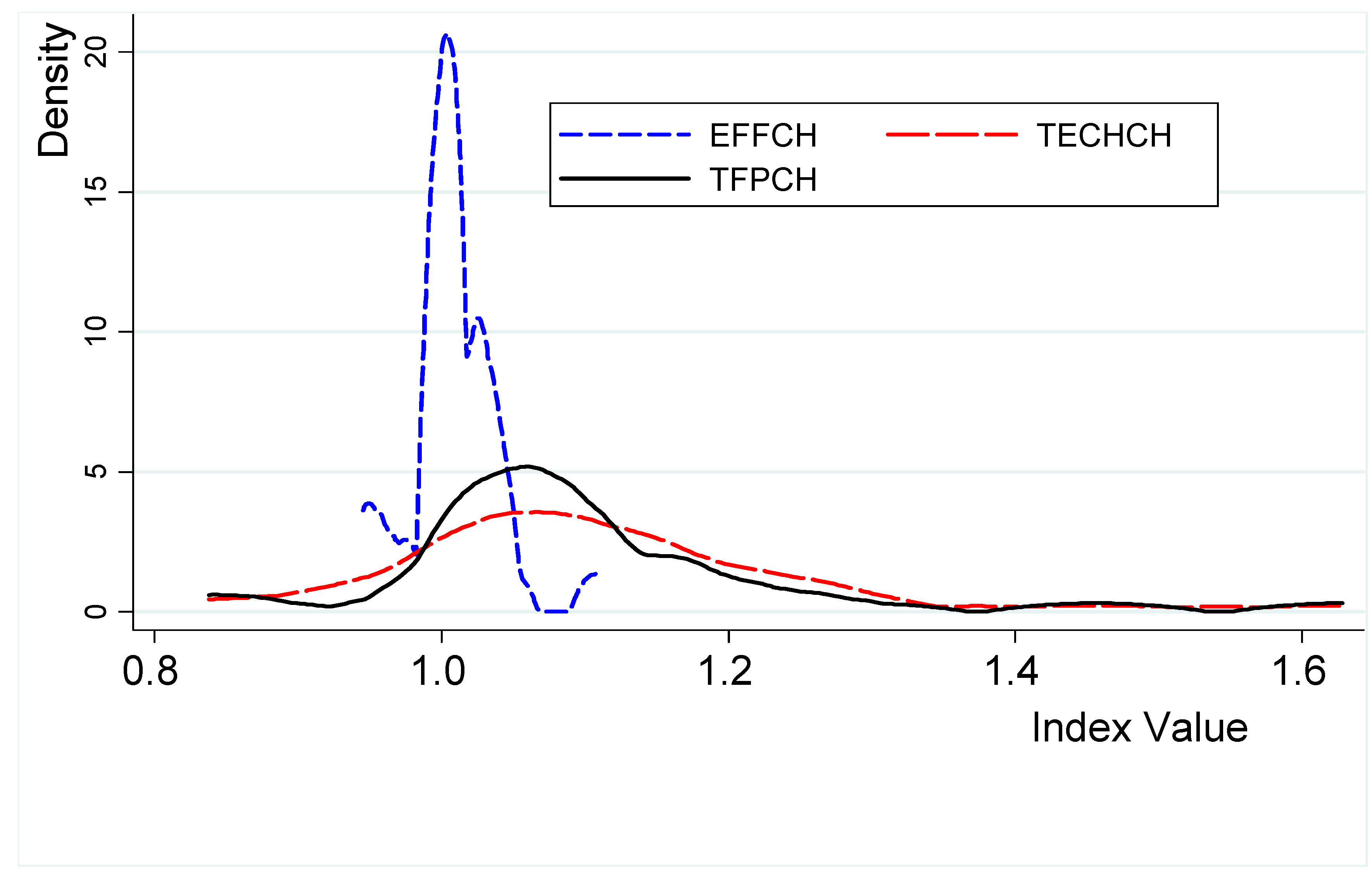

3.3. TFP Change Analysis of Vietnam Universities

3.4. Factors Affecting the Performance of Vietnamese Universities

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Pinheiro, R.; Pillay, P. Higher education and economic development in the OECD: Policy lessons for other countries and regions. J. High. Educ. Policy Manag. 2016, 38, 150–166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paik, S. Higher Education and National Development; KDI School of Public Policy and Management: Sejong, Republic of Korea, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Lattu, A.; Cai, Y. Tensions in the Sustainability of Higher Education—The Case of Finnish Universities. Sustainability 2020, 12, 1941. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lozano, R.; Ceulemans, K.; Alonso-Almeida, M.; Huisingh, D.; Lozano, F.J.; Waas, T.; Lambrechts, W.; Lukman, R.; Hugé, J. A review of commitment and implementation of sustainable development in higher education: Results from a worldwide survey. J. Clean. Prod. 2015, 108, 1–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramos, T.B.; Caeiro, S.; van Hoof, B.; Lozano, R.; Huisingh, D.; Ceulemans, K. Experiences from the implementation of sustainable development in higher education institutions: Environmental Management for Sustainable Universities. J. Clean. Prod. 2015, 106, 3–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Figueiró, P.S.; Raufflet, E. Sustainability in higher education: A systematic review with focus on management education. J. Clean. Prod. 2015, 106, 22–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abugre, J.B. Institutional governance and management systems in Sub-Saharan Africa higher education: Developments and challenges in a Ghanaian Research University. High. Educ. 2017, 75, 323–339. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ziderman, A.; Albrecht, D. Financing Universities in Developing Countries; Routledge: London, UK, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Tilak, J.B.G. Higher Education and Development. In International Handbook of Educational Research in the Asia-Pacific Region; Springer: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2003; pp. 809–826. [Google Scholar]

- Shuqin, W.; Yuqing, Z. Colleges and Universities Regulations: Limited Autonomy of Chinese Colleges and Universities; Advances in Educational Technology and Psychology, 2021 3rd International Modern Education Research Conference Vol. 24, 2021. Available online: https://www.clausiuspress.com/conferences/AETP/IMERC%202021/IMERC009.pdf (accessed on 12 December 2023).

- Lao, R. The Limitations of Autonomous University Status in Thailand: Leadership, Resources and Ranking. J. Soc. Issues Southeast Asia 2015, 30, 550–559. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jarernsiripornkul, S.; Pandey, I.M. Governance of autonomous universities: Case of Thailand. J. Adv. Manag. Res. 2018, 15, 288–305. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ly, T.T.; Marginson, S.; Do, H.M.; Do, Q.T.N.; Le, T.T.T.; Nguyen, T.N.; Vu, T.T.P.; Pham, T.N.; Nguyen, H.T.L.; Ho, T.T.H. Higher Education in Vietnam; Palgrave Macmillan: London, UK, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Weidman, J.C. Diversifying Finance of Higher Education. Educ. Policy Anal. Arch. 1995, 3, 5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Suresh, E.; Kumaravelu, A. The Quality of Education and its Challenges in Developing Countries. In Proceedings of the 2017 ASEE International Forum, Columbus, OH, USA, 28 June 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Varghese, N.V.; Martin, M. Governance Reforms in Higher Education: A Study of Institutional Autonomy in Asian Countries; International Institute for Educational Planning: Paris, France, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Agasisti, T.; Shibanova, E. Autonomy, Performance and Efficiency: An Empirical Analysis of Russian Universities 2014–2018. SSRN Electron. J. 2020. Available online: https://ssrn.com/abstract=3553716 (accessed on 12 December 2023).

- Aghion, P.; Dewatripont, M.; Hoxby, C.; Mas-Colell, A.; Sapir, A. The governance and performance of universities: Evidence from Europe and the US. Econ. Policy 2010, 25, 7–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kantabutra, S.; Tang, J.C.S. Efficiency Analysis of Public Universities in Thailand. Tert. Educ. Manag. 2010, 16, 15–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Enders, J.; de Boer, H.; Weyer, E. Regulatory autonomy and performance: The reform of higher education re-visited. High. Educ. 2012, 65, 5–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Belgaroui, R.; Hamad, S.B. The Good Practices of Academic Autonomy as Mechanism of Governance and Performance of Higher Education Institutions: Case of the University of Sfax. Int. J. Engl. Lit. Soc. Sci. 2021, 6, 177–184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clarice, A.M.; Hough, M.J.; Stewart, R.F. University autonomy and public policies: A system theory perspective. High. Educ. 1984, 13, 23–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carvalho, A.E.; Cosme, A.; Veiga, A. Inclusive Education Systems: The Struggle for Equity and the Promotion of Autonomy in Portugal. Educ. Sci. 2023, 13, 875. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aithal, P.S.; Aithal, S. Autonomy for Universities Excellence—Challenges and Opportunities. SSRN Electron. J. 2019, 3, 36–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ritzen, J. University Autonomy: Improving Educational Output; IZA World of Labor; Institute for the Study of Labor (IZA): Bonn, Germany, 2016. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Central Executive Committee of the CPV, Resolution No. 29-NQ/TW on “Fundamental and Comprehensive Innovation in Education, Serving Industrialization and Modernization in a Socialist-Oriented Market Economy during International Integration” Ratified in the 8th Session; Central Executive Committee of the CPV: Hanoi, Vietnam, 2013.

- National Assembly, Law 34/2018/QH14: Amendments and Supplements to Some Articles of the Higher Education Law; Ministry of Education and Training: Hanoi, Vietnam, 2018.

- Ministry of Education and Training. Circular 36/2017/TT-BGDT: Promulgating Regulations on Public Implementation of Educational and Training Institutions under the National Education System; Ministry of Education and Training: Hanoi, Vietnam, 2017.

- Charnes, A.; Cooper, W.W.; Rhodes, E. Measuring the efficiency of decision-making units. Eur. J. Oper. Res. 1978, 2, 429–444. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coelli, T.; Rao, D.S.P.; Battese, G.E. An Introduction to Efficiency and Productivity Analysis; Kluwer Academic: Dordrecht, The Netherlands, 1998. [Google Scholar]

- Färe, R.; Grosskopf, S.; Norris, M.; Zhang, Z. Productivity growth, technical progress, and efficiency change in industrialized countries. Am. Econ. Rev. 1994, 84, 66–83. Available online: http://www.jstor.org/stable/2117971 (accessed on 12 December 2023).

- Battese, G.E.; Coelli, T.J. A model for technical inefficiency effects in a stochastic frontier production function for panel data. Empir. Econ. 1995, 20, 325–332. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kuah, C.T.; Wong, K.Y. Efficiency assessment of universities through data envelopment analysis. Procedia Comput. Sci. 2011, 3, 499–506. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cinemre, H.A.; Ceyhan, V.; Bozoğlu, M.; Demiryürek, K.; Kılıç, O. The cost efficiency of trout farms in the Black Sea Region, Turkey. Aquaculture 2006, 251, 324–332. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jurado, E.B.; Moral, A.M.; Viruel, M.J.M.; Uclés, D.F. Evaluation of Corporate Websites and Their Influence on the Performance of Olive Oil Companies. Sustainability 2018, 10, 1274. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Banker, R.D.; Charnes, A.; Cooper, W.W. Some models for estimating technical and scale inefficiencies in data envelopment analysis. Manag. Sci. 1984, 30, 1078–1092. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cook, W.D.; Seiford, L.M. Data Envelopment Analysis (DEA)—Thirty Years On. Eur. J. Oper. Res. 2009, 192, 1–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kuah, C.T.; Wong, K.Y.; Behrouzi, F. A Review on Data Envelopment Analysis (DEA). In Proceedings of the Fourth Asia International Conference on Mathematical/Analytical Modelling and Computer Simulation, Kota Kinabalu, Malaysia, 26–28 May 2010; pp. 168–173. [Google Scholar]

- National Assembly of Vietnam, Law on Higher Education No. 08/2012/QH13; Ministry of Education and Training: Hanoi, Vietnam, 2012.

- Cook, W.D.; Zhu, J. Rank order data in DEA: A general framework. Eur. J. Oper. Res. 2006, 174, 1021–1038. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Webometrics, Update Webometrics Rankings for Vietnamese Universities. 2020. Available online: https://www.webometrics.info/en/asia/vietnam (accessed on 12 December 2023).

- Ministry of Education and Training. Circular 03/2022/TT-BGDT Regulations on Determining Admission Targets for Undergraduate, Master’s, and Doctoral Programs, as well as Admission Targets for Community College Education in Early Childhood Education; Ministry of Education and Training: Hanoi, Vietnam, 2022.

- Hoi, V.X.; Quyen, N.D.; Xuan, D.T.T.; Tan, B.N.; Thao, N.T.P.; Phiet, L.T.; Dat, N.; Ha, T.T.; Niem, L.D. Training, technology upgrading, and total factor productivity improvement of farms: A case of cassava (Manihot esculenta Crantz) production in Dak Lak province, Vietnam. Cogent Econ. Financ. 2022, 10, 2023270. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abbott, M.; Doucouliagos, C. The efficiency of Australian universities: A data envelopment analysis. Econ. Educ. Rev. 2003, 22, 89–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taylor, R.C.; Liang, X.; Laubichler, M.D.; West, G.B.; Kempes, C.P.; Dumas, M. Systematic shifts in scaling behavior based on organizational strategy in universities. PLoS ONE 2021, 16, e0254582. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yurchyshena, L. The influence of indicators of scale on the financial sustainability of the university: Methodological and practical aspects. Innov. Sustain. 2022, 4, 129–138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Daghbashyan, Z. Do University Units Differ in the Efficiency of Resource Utilization. Working Paper Series in Economics and Institutions of Innovation 176; Royal Institute of Technology, CESIS—Centre of Excellence for Science and Innovation Studies: Stockholm, Sweden, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Bajunid, I.A.; Wong, W.C.K. Private higher education institutions in Malaysia. In A Global Perspective on Private Higher Education; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2016; pp. 131–155. [Google Scholar]

- Simarmata, J. Human Resource Development Model for Improving Private University Competitiveness. In Proceedings of the 2nd Padang International Conference on Education, Economics, Business and Accounting (PICEEBA-2 2018), Padang, Indonesia, 24–25 November 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Tham, S.-Y. Exploring Access and Equity in Malaysias Private Higher Education. SSRN Electron. J. 2011. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Malik, M.A.; Masood, T.; Sheikh, M.A. Econometric Analysis of Total Factor Productivity in India. Indian Econ. J. 2021, 69, 88–104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Giang, M.H.; Xuan, T.D.; Trung, B.H.; Que, M.T. Total Factor Productivity of Agricultural Firms in Vietnam and Its Relevant Determinants. Economies 2019, 7, 4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, T.; Park, C. R&D, Trade, and Productivity Growth in Korean Manufacturing. Rev. World Econ./Weltwirtschaftliches Arch. 2003, 139, 460–483. [Google Scholar]

- Nguyen, H.Q. Total factor productivity growth of Vietnamese enterprises by sector and region: Evidence from panel data analysis. Economies 2021, 9, 109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- National Assembly of Vietnam, Education Law No. 11/1998/QH10; Ministry of Education and Training: Hanoi, Vietnam, 1998.

- National Assembly of Vietnam, Education Law No. 38/2005/QH11; Ministry of Education and Training: Hanoi, Vietnam, 2005.

- Ngo, H.T.; Niem, L.D.; Tran, P.C.; Nguyen, T.T.; Doan, D.T.; Ngo, H.T. Factors affecting academic staff development in the context of university autonomy through the lens of stakeholders: A case study from Tay Nguyen University, Vietnam. J. Appl. Res. High. Educ. 2023, 15, 411–428. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ministry of Education and Training, Higher Education Statistics. Available online: https://moet.gov.vn/thong-ke/Pages/thong-ko-giao-duc-dai-hoc.aspx?ItemID=6636 (accessed on 12 December 2023).

- Färe, R.; Grosskopf, S.; Lindgren, B.; Roos, P. Productivity developments in Swedish hospitals: A Malmquist output index approach. In Data Envelopment Analysis: Theory, Methodology and Applications; Charnes, A., Cooper, W.W., Lewin, A.Y., Seiford, L.M., Eds.; Kluwer: Dordrecht, The Netherlands, 1993; pp. 253–272. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Helal, S.M.A.; Elimam, H. Measuring the efficiency of health services areas in the Kingdom of Saudi Arabia using data envelopment analysis (DEA): A comparative study between the years 2014 and 2006. Int. J. Econ. Financ. 2017, 9, 172–184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fumasoli, T.; Gornitzka, A.; Maassen, P. University Autonomy and Organizational Change Dynamics; ARENA Working Paper 8; Arena Centre for European Studies, University of Oslo: Oslo, Norwa, 2014. [Google Scholar]

| Inputs | Outputs |

|---|---|

| X1: Number of academic staff | Y1: Number of graduates |

| X2: Number of students | Y2: Average graduates’ results (scoring) |

| X3: Qualification of first-year students (minimun entrance score) | Y3: Graduates’ employment (after one year) |

| X4: University’s total budget | Y4: Number of citations (from academic staff profiles) |

| No. | Document | Year | Content |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Education Law No. 11/1998/QH10) | 1998 | Course content, instructional materials, lesson plans, and teaching autonomy [55]. |

| 2 | Education Law No. 38/2005/QH11 | 2005 | Curriculum, material, and instructional and learning plan autonomy. Academic oversight of student enrollment, accreditation, and training. Human resources and recruitment via self-governance [56]. |

| 3 | Higher Education Law No. 08/2012 /QH13 | 2012 | Quality assurance, training, international cooperation, and organizational autonomy. Accountable for overseeing the enrollment process, establishing enrollment quotas, disseminating public information regarding quotas, training quality, and fulfilling other obligations associated with ensuring the quality of instruction at higher education institutions. Because of the university council’s restricted jurisdiction, autonomy in financial matters was curtailed [39]. |

| 4 | Amended Law on Higher Education No. 34/2018/QH14. | 2018 | Academic institutions are endowed with autonomy regarding communicating and implementing their policy guidelines for student tuition and scholarships, academic staff, public employees, and other personnel, and the enrollment and initiation of new training programs. The function of university councils is expanded by law, and universities are granted greater financial autonomy. Universities that operate with autonomy must also answer to society, parents, and students, in addition to the responsibilities outlined previously. The Ministry of Education and Training retains jurisdiction over the complexities associated with the independence and accountability of higher education institutions [27]. |

| Criteria (Per University) | 2017–2018 | 2021–2022 | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Total | Type | Total | Type | |||

| Public | Private | Public | Private | |||

| Number of institutions | 236 | 171 | 65 | 242 | 175 | 67 |

| Admitted undergraduate students | 1852 | 2064 | 1295 | 2351 | 2533 | 1875 |

| Admitted graduate students | 203 | 245 | 95 | 132 | 165 | 45 |

| The scale of undergraduate students | 7233 | 8418 | 4116 | 8865 | 9879 | 6217 |

| The scale of graduate students | 514 | 626 | 220 | 502 | 620 | 196 |

| - Master students | 452 | 541 | 215 | 454 | 554 | 193 |

| - PhD students | 62 | 84 | 4 | 48 | 66 | 3 |

| Annual graduation | 1448 | 1770 | 599 | 1013 | 1224 | 462 |

| Full-time faculty | 318 | 346 | 242 | 323 | 331 | 301 |

| - Full Professors | 3.1 | 3.1 | 3.1 | 2.5 | 2.6 | 2.1 |

| - Assoc. Professors | 19.2 | 22.2 | 11.4 | 190 | 2.6 | 2.1 |

| Govt’s subsidy per student (Million VND) | 3.4 | 4.1 | 0.0 | 3.8 | 4.6 | 0.0 |

| Annual tuition (million VND) | 14.1 | 11.6 | 25.0 | 18.0 | 13.0 | 41.0 |

| University Group | No. of Uni. | General Efficiency (CRS%) | Internal Efficiency (VRS%) | External Efficiency (Scale%) | Cause of Inefficiency |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| GE | IE | EE | |||

| The year 2018 | |||||

| Efficiency | 14 | 100 | 100 | 100 | - |

| External Inefficiency | 5 | 91.4 | 100 | 91.4 | EE |

| In/external Inefficiency | 13 | 80.2 | 83.4 | 96.1 | IE, EE |

| Average | 32 | 90.6 | 93.3 | 97.1 | IE, EE |

| The year 2021 | |||||

| Efficiency | 18 | 100 | 100 | 100 | - |

| External Inefficiency | 5 | 92.3 | 100 | EE | |

| In/external Inefficiency | 9 | 77.6 | 82.8 | 93.7 | IE, EE |

| Average | 32 | 92.5 | 95.2 | 97.1 | IE, EE |

| Criteria | Technology (TECHCH) | Technical Efficiency (EFFCH) | Total Factor Productivity (TFPCH) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Index values | |||

| 2019 | 1.069 | 0.987 | 1.055 |

| 2020 | 1.023 | 1.017 | 1.041 |

| 2021 | 1.189 | 1.018 | 1.211 |

| Period 2018–2021 | 1.092 | 1.007 | 1.100 |

| Number of universities (2018–2021) | |||

| Advanced | 28 | 14 | 26 |

| Unchanged | 1 | 13 | 1 |

| Decreased | 3 | 5 | 5 |

| Total | 32 | 32 | 32 |

| Variable | Type | Descriptions | Expected Signs |

|---|---|---|---|

| Dependent variables | |||

| Y: TFPCH | Cont. | A proxy for the ability to improve the total factor productivity of a university during 2018–2021 | |

| Y: EFFCH | Cont. | A proxy for individual improvement or the ability of a university to benchmark the best universities (the universities on the PPF) during 2018–2021. | |

| Y: TECHCH | Cont. | A proxy for the ability to shift the PPF outward during 2018–2021 | |

| Explanatory variables | |||

| X1: STUNUMBER | Discrete | Student population of the university | +/− |

| X2: FANUMBER | Discrete | Number of the academic staff of the university | +/− |

| X3: HQFNUMBER | Discrete | Number of highly qualified faculties (full and associate professors) | + |

| X4: LANDPS | Cont. | The area of land (m2) | + |

| X5: AREAPS | Cont. | The floor area of buildings (m2) | + |

| X6: LABNUMBER | Discrete | Number of labs | + |

| X7: RESEARHFUND | Cont. | Funding for research | + |

| X8: GOVTSUB | Cont. | Governmental subsidy to the university | + |

| D1: QAMETHOD | Binary | Accreditation by accreditation organizations: Foreign 0; Vietnamese: 1. | − |

| D2: OWNERSHIP | Binary | Private: 0; Public: 1. | +/− |

| D3: LOCATION | Binary | The main campus in a small city: 0, otherwise: 1. | + |

| (1) | (2) | (3) | |

|---|---|---|---|

| VARIABLES | TFPCH | TECHCH | EFFCH |

| X1: STUNUMBER | −1.04 × 10−6 | −2.66 × 10−7 | −7.25 × 10−7 |

| X2: FANUMBER | 0.000177 | 9.14 × 10−5 | 9.01 × 10−5 |

| X3: HQFNUMBER | −0.00205 | −0.00146 | −0.000636 |

| X4: LANDPS | −0.00326 * | −0.00312 ** | −5.65 × 10−5 |

| X5: AREAPS | 0.000388 | 0.000385 | 1.96 × 10−5 |

| X6: LABNUMBER | 0.00141 *** | 0.00139 *** | 8.22 × 10−6 |

| X7: RESEARCHFUND | 0.00459 ** | 0.00404 ** | 0.000494 |

| X8: GOVTSUB | −0.000101 | 5.42 × 10−5 | −0.000139 |

| D1: QAMETHOD | −0.149 ** | −0.119 ** | −0.0278 |

| D2: OWNERSHIP | −0.118 * | −0.113 * | 0.00142 |

| D3: LOCATION | −0.0154 | 0.0117 | −0.0133 |

| Constant | 1.179 *** | 1.148 *** | 1.009 *** |

| Observations | 96 | 96 | 96 |

| No. of universities | 32 | 32 | 32 |

| R-squared | 0.233 | 0.277 | 0.048 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Hieu, N.T.; Niem, L.D. Autonomy Acquisition and Performance within Higher Education in Vietnam—A Road to a Sustainable Future? Sustainability 2024, 16, 1336. https://doi.org/10.3390/su16031336

Hieu NT, Niem LD. Autonomy Acquisition and Performance within Higher Education in Vietnam—A Road to a Sustainable Future? Sustainability. 2024; 16(3):1336. https://doi.org/10.3390/su16031336

Chicago/Turabian StyleHieu, Ngo Thi, and Le Duc Niem. 2024. "Autonomy Acquisition and Performance within Higher Education in Vietnam—A Road to a Sustainable Future?" Sustainability 16, no. 3: 1336. https://doi.org/10.3390/su16031336

APA StyleHieu, N. T., & Niem, L. D. (2024). Autonomy Acquisition and Performance within Higher Education in Vietnam—A Road to a Sustainable Future? Sustainability, 16(3), 1336. https://doi.org/10.3390/su16031336