The Impact of Public Policies and Civil Society on the Sustainable Behavior of Romanian Consumers of Electrical and Electronic Products

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Literature Review

3. Research Methodology

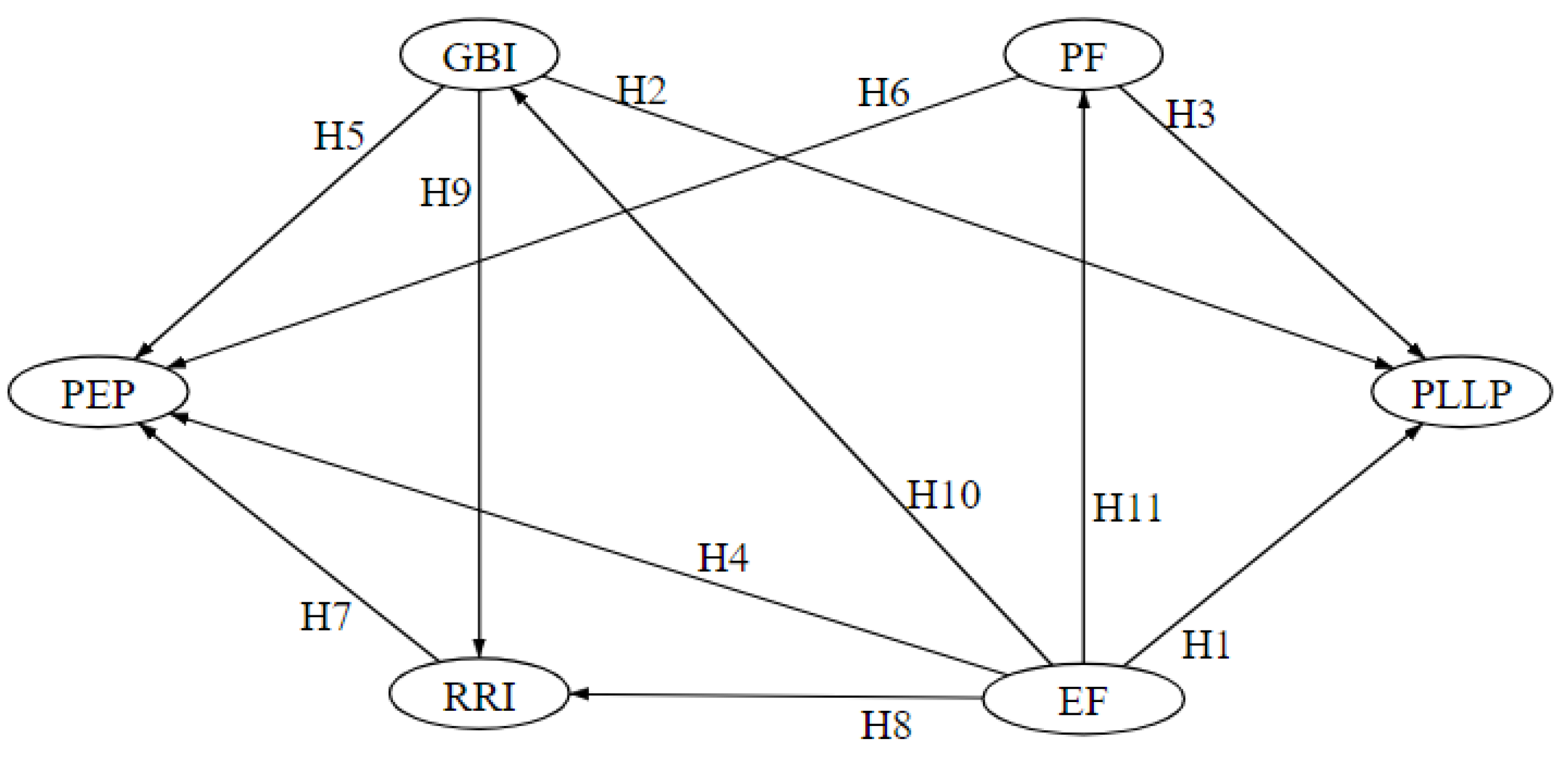

3.1. Research Design

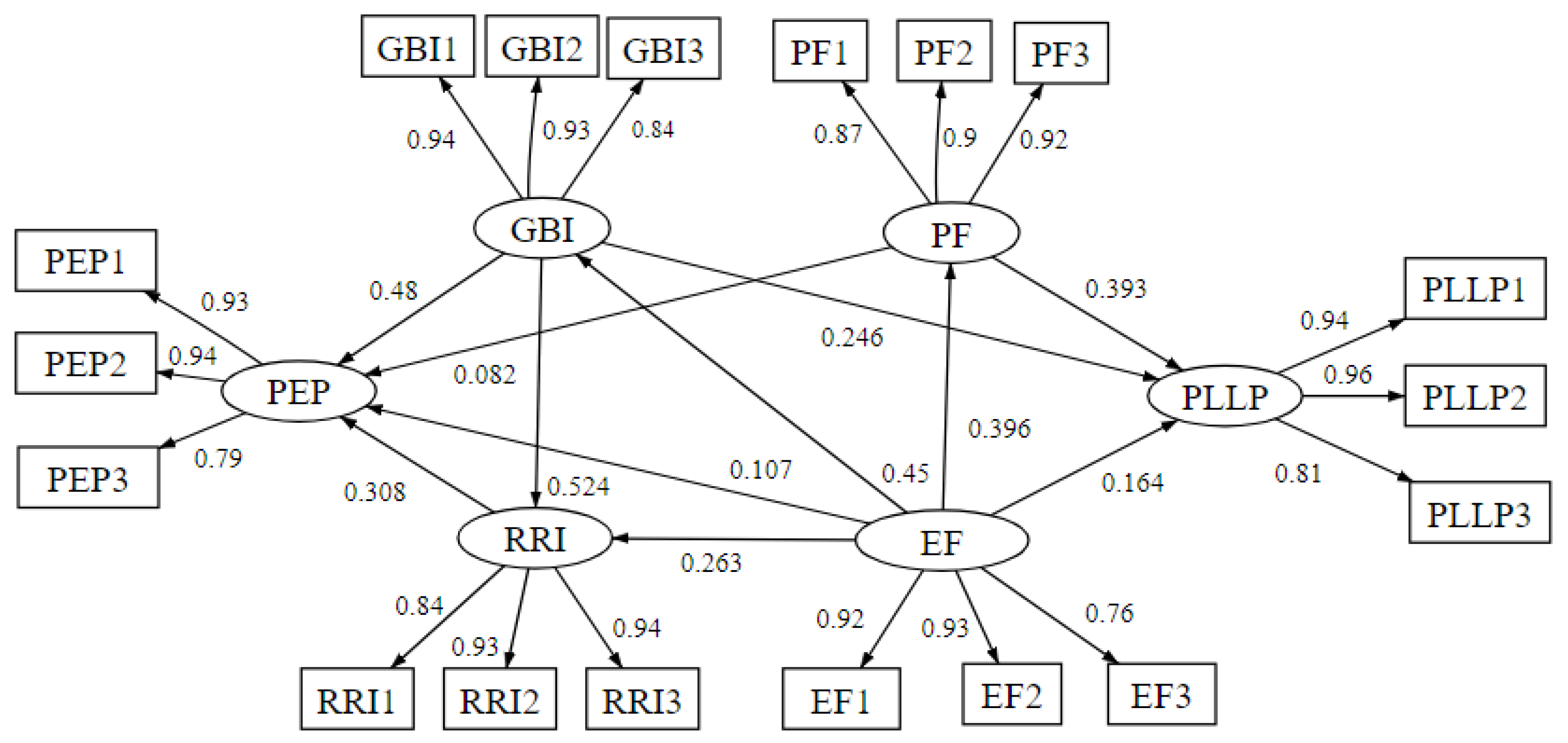

3.2. Measurement Model Assessment

3.3. Evaluation of the Structural Model

4. Results and Discussion

5. Conclusions and Policy Implications

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Söderholm, P. The green economy transition: The challenges of technological change for sustainability. Sustain. Earth 2020, 3, 6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gossen, M.; Kropfeld, M.I. “Choose nature. Buy less.” Exploring sufficiency-oriented marketing and consumption practices in the outdoor industry. Sustain. Prod. Consum. 2022, 30, 720–736. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Machová, R.; Ambrus, R.; Zsigmond, T.; Bakó, F. The impact of green marketing on consumer behavior in the market of palm oil products. Sustainability 2022, 14, 1364. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Riskos, K.; Dekoulou, P.; Mylonas, N.; Tsourvakas, G. Ecolabels and the attitude–behavior relationship towards green product purchase: A multiple mediation model. Sustainability 2021, 13, 6867. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thøgersen, J. Consumer behavior and climate change: Consumers need considerable assistance. Curr. Opin. Behav. Sci. 2021, 42, 9–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lăzăroiu, G.; Andronie, M.; Uţă, C.; Hurloiu, I. Trust management in organic agriculture: Sustainable consumption behavior, environmentally conscious purchase intention, and healthy food choices. Front. Public Health 2019, 7, 340. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lăzăroiu, G.; Ionescu, L.; Andronie, M.; Dijmărescu, I. Sustainability management and performance in the urban corporate economy: A systematic literature review. Sustainability 2020, 12, 7705. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Toader, C.-S.; Rujescu, C.I.; Feher, A.; Sălășan, C.; Cuc, L.D.; Bodnar, K. Generation differences in the behaviour of household consumers in Romania related to voluntary measures to reduce electric energy consumption. Amfiteatru Econ. 2023, 25, 710–727. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alves, R.; Ferreira, K.L.A.; Lima, R.; Moraes, F.T.F. An action research study for elaborating and implementing an electronic waste collection program in Brazil. Syst. Pract. Action Res. 2021, 34, 91–108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shaharudin, M.S.; Fernando, Y.; Ahmed, E.R.; Shahudin, F. Environmental NGOs involvement in dismantling illegal plastic recycling factory operations in Malaysia. J. Gov. Integr. 2020, 4, 29–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tummers, L. Public policy and behavior change. Public Adm. Rev. 2019, 79, 925–930. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, X.; Miao, X.; Wu, J.; Duan, Z.; Yang, R.; Tang, Y. Towards holistic governance of China’s E-Waste recycling: Evolution of networked policies. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2020, 17, 7407. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fu, Q.; Zhao, X.; Chang, C.-P. Does ESG performance bring to enterprises’ green innovation? Yes, evidence from 118 countries. Oeconomia Copernic. 2023, 14, 795–832. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jakubelskas, U.; Skvarciany, V. Circular economy practices as a tool for sustainable development in the context of renewable energy: What are the opportunities for the EU? Oeconomia Copernic. 2023, 14, 833–859. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sánchez García, J.; Galdeano Gómez, E. What drives the preferences for cleaner energy? Parametrizing the elasticities of environmental quality demand for greenhouse gases. Oeconomia Copernic. 2023, 14, 449–482. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, M.; Feng, G.-F.; Chang, C.-P. Is green finance capable of promoting renewable energy technology? Empirical investigation for 64 economies worldwide. Oeconomia Copernic. 2023, 14, 483–510. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ogutu, H.; El Archi, Y.; Dénes Dávid, L. Current trends in sustainable organization management: A bibliometric analysis. Oeconomia Copernic. 2023, 14, 11–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brodny, J.; Tutak, M. The level of implementing sustainable development goal "Industry, innovation and infrastructure" of Agenda 2030 in the European Union countries: Application of MCDM methods. Oeconomia Copernic. 2023, 14, 47–102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deniz, P.Ö.; Aydın, Ç.Y.; Kiraz, E.D.E. Electronic waste awareness among students of engineering department. Cukurova Med. J. 2019, 44, 101–109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nguyen, H.; Lee, C.-H.; Hung, R.-J. Willingness of end users to pay for e-waste recycling. Glob. J. Environ. Sci. Manag. 2021, 7, 47–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Directive (EU) 2019/771 of the European Parliament and of the Council of 20 May 2019 on Certain Aspects Concerning Contracts for the Sale of Goods, Amending Regulation (EU) 2017/2394 and Directive 2009/22/EC, and Repealing Directive 1999/44/EC. Available online: https://eur-lex.europa.eu/legal-content/EN/TXT/PDF/?uri=CELEX:32019L0771 (accessed on 3 February 2023).

- Jain, A. Development and evaluation of existing policies and regulations for E-waste in India. In Proceedings of the IEEE International Symposium on Sustainable Systems and Technology, Tempe, AZ, USA, 18–20 May 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Weila, L.; Varenyam, A. Environmental and health impacts due to e-waste disposal in China—A review. Sci. Total Environ. 2020, 737, 139745. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Okereafor, U.; Makhatha, M.; Mekuto, L.; Uche-Okereafor, N.; Sebola, T.; Mavumengwana, V. Toxic metal implications on agricultural soils, plants, animals, aquatic life and human health. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2020, 17, 2204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sahle-Demessie, E.; Mezgebe, B.; Dietrich, J.; Shan, Y.; Harmon, S.; Lee, C.C. Material recovery from electronic waste using pyrolysis: Emissions measurements and risk assessment. J. Environ. Chem. Eng. 2021, 9, 104943. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fernando, X.; Lăzăroiu, G. Spectrum sensing, clustering algorithms, and energy-harvesting technology for cognitive-radio-based internet-of-things networks. Sensors 2023, 23, 7792. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sultana, A.; Fernando, X. Intelligent reflecting surface-aided device-to-device communication: A deep reinforcement learning approach. Future Internet 2022, 14, 256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shukla, N. The Environmental Impact of Broken Technology and the Right to Repair Movement. Americas Europe: Pollution Solutions 2021. Available online: https://earth.org/the-environmental-impact-of-broken-technology-and-the-right-to-repair-movement/ (accessed on 3 February 2023).

- Andronie, M.; Lăzăroiu, G.; Iatagan, M.; Hurloiu, I.; Dijmărescu, I. Sustainable cyber-physical production systems in big data-driven smart urban economy: A systematic literature review. Sustainability 2021, 13, 751. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Andronie, M.; Lăzăroiu, G.; Ștefănescu, R.; Uță, C.; Dijmărescu, I. Sustainable, smart, and sensing technologies for cyber-physical manufacturing systems: A systematic literature review. Sustainability 2021, 13, 5495. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Colesca, S.E.; Ciocoiu, C.N.; Popescu, M.L. Determinants of WEEE recycling behavior in Romania: A fuzzy approach. Int. J. Environ. Res. 2014, 8, 353–366. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shevchenko, T.; Laitala, K.; Danko, Y. Understanding consumer E-Waste recycling. Sustainability 2019, 11, 2656. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Melnyk, V.; Carrillat, F.A.; Melnyk, V. The influence of social norms on consumer behavior: A Meta-Analysis. J. Mark. 2022, 86, 98–120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lăzăroiu, G.; Ionescu, L.; Uță, C.; Hurloiu, I.; Andronie, M.; Dijmărescu, I. Environmentally responsible behavior and sustainability policy adoption in green public procurement. Sustainability 2020, 12, 2110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oskamp, S.; Harrington, M.J.; Edwards, T.C.; Sherwood, D.L.; Oku-da, S.M.; Swanson, D.C. Factors influencing household recycling behavior. Environ. Behav. 1991, 23, 494–519. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hussain, S.; Huang, J. The impact of cultural values on green purchase intentions through ecological awareness and perceived consumer effectiveness: An empirical investigation. Front. Environ. Sci. 2022, 10, 985200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wijekoon, R.; Sabri, M.F. Determinants that influence green product purchase intention and behavior: A literature review and guiding framework. Sustainability 2021, 13, 6219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prakash, S.; Stamminger, R.; Ines, O. Faktencheck Obsoleszenz: Analyse der Entwicklung der Lebens- und Nutzungsdauer von ausgewählten Elektro- und elektronikgeräten. In Obsoleszenzinterdisziplinär. Vorzeitiger Verschleißaus Sicht von Wissenschaft und Praxis; Brönneke, T., Wechsler, A., Eds.; Nomos Verlag: Baden-Baden, Germany, 2015; pp. 98–99. [Google Scholar]

- Röös, E.; Larsson, J.; Resare Sahlin, K.; Jonell, M.; Lindahl, T.; André, E.; Säll, S.; Harring, N.; Persson, M. Policy options for sustainable food consumption: Review and recommendations for Sweden. Mistra Sustain. Consum. Rep. 2021, 1, 10. [Google Scholar]

- Ali, M.; Ullah, S.; Ahmad, M.S.; Cheok, M.Y.; Alenezi, H. Assessing the impact of green consumption behavior and green purchase intention among millennials toward sustainable environment. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 2023, 30, 23335–23347. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anuar, M.M.; Omar, K.; Ahmed, Z.U.; Saputra, J.; Yakoop, A.Y. Drivers of green consumption behavior and their implications for management. Pol. J. Manag. Stud. 2020, 21, 71–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Persson, J. A Study about Purchase Intentions for a Green Durable Good. Master’s Thesis, Blekinge Institute of Technology, Karlskrona, Sweden, 2018. Available online: https://www.diva-portal.org/smash/get/diva2:1239176/FULLTEXT02 (accessed on 14 January 2023).

- Dabija, D.C.; Bejan, B.; Grant, D. The impact of consumer green behavior on green loyalty among retail formats: A Romanian case study. Morav. Geogr. Rep. 2018, 26, 173–185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bäunker, L. Circular Consumption in the Linear Economy: Only a Drop in the Ocean? 2020. Available online: https://www.circle-economy.com/blogs/circular-consumption-in-the-linear-economy-only-a-drop-in-the-ocean/ (accessed on 27 March 2023).

- Mandarić, D.; Hunjet, A.; Vuković, D. The impact of fashion brand sustainability on consumer purchasing decisions. J. Risk Financ. Manag. 2022, 15, 176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Islam, M.T.; Huda, N.; Sahajwalla, V.; Baumber, A.; Shumon, R.; Zaman, A.; Ali, F. A global review of consumer behavior towards e-waste and implications for the circular economy. J. Clean. Prod. 2021, 316, 128297. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dalhammar, C.; Hartman, C.; Larsson, J.; Jarelin, J.; Milios, L.; Mont, O. Moving away from the throwaway society. Five policy instruments for extending the life of consumer durables. In Mistra Sustainable Consumption; Chalmers University of Technology: Gothenburg, Sweden, 2022; Volume 1, p. 12E. [Google Scholar]

- Al-Kumaim, N.H.; Shabbir, M.S.; Alfarisi, S.; Hassan, S.H.; Alhazmi, A.K.; Hishan, S.S.; Al-Shami, S.; Gazem, N.A.; Mohammed, F.; Abu Al-Rejal, H.M. Fostering a clean and sustainable environment through green product purchasing behavior: Insights from Malaysian consumers’ perspective. Sustainability 2021, 13, 12585. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adhitiya, L.; Astuti, R.D. The effect of consumer value on attitude toward green product and green consumer behavior in organic food. IPTEK J. Proc. Ser. 2019, 5, 193–202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mohanty, P.K.; Patro, A.; Harindranath, R.M.; Kumar, N.S.; Panda, D.K.; Dubey, R. Perceived government initiatives: Scale development, validation and impact on consumers’ pro-environmental behavior. Energy Policy 2021, 158, 112534. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- White, K.; Habib, R.; Hardisty, D.J. How to SHIFT consumer behaviors to be more sustainable: A literature review and guiding framework. J. Mark. 2019, 83, 22–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, L.; Wu, Q.; Jiang, L. Impact of environmental concern on ecological purchasing behavior: The moderating effect of prosociality. Sustainability 2022, 14, 3004. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rossi, C.; Rivetti, F. Young consumers’ purchase behavior of sustainably labelled food products. What is the role of scepticism? Food Qual. Prefer. 2023, 105, 104772. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shamsi, M.A.; Chaudhary, A.; Anwar, I.; Dasgupta, R.; Sharma, S. Nexus between environmental consciousness and consumers’ purchase intention toward circular textile products in India: A Moderated-Mediation Approach. Sustainability 2022, 14, 12953. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mustafa, S.; Hao, T.; Jamil, K.; Qiao, Y.; Nawaz, M. Role of eco-friendly products in the revival of developing countries’ economies and achieving a sustainable green economy. Front. Environ. Sci. 2022, 10, 955245. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pierre Fabre Group. Understand the Environmental and Social Impacts of Products. 2023. Available online: https://www.pierre-fabre.com/en/our-commitments/tthe-green-impact-index/environmental-and-social-impact-of-products/ (accessed on 28 January 2023).

- Atahau, A.D.; Huruta, A.D.; Lee, C.W. Rural microfinance sustainability: Does local wisdom driven-governance work? J. Clean. Prod. 2020, 267, 122153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mayers, C.K.M.; France, S.J.P.; Cowell, S.J. Extended producer responsibility for waste electronics. J. Ind. Ecol. 2008, 9, 169–189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bovea, M.; Ibáñez-Forés, V.; Pérez-Belis, V.; Juan, P. A survey on consumers’ attitude towards storing and end of life strategies of small information and communication technology devices in Spain. Waste Manag. 2018, 71, 589–602. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Târțiu, V.; Ștefănescu, M.; Petrache, E.; Gurău, C. Tranziția către o economie circulară. De la managementul deșeurilor la o Economie Verde, în România (Studiu). Studii de strategie și politici SPOS 2019. Institutul European din România. Available online: http://ier.gov.ro/wp-content/uploads/2019/03/Final_Studiul-3_Spos-2018_Economie-circular%c4%83-1.pdf (accessed on 4 March 2023).

- Zhong, H.; Zhou, S.; Zhao, Z.; Zhang, H.; Nie, J.; Simayi, P. An empirical study on the types of consumers and their preferences for E-waste recycling with a points system. Clean. Responsible Consum. 2022, 7, 100087. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bezzina, F.H.; Dimech, S. Investigating the determinants of recycling behavior in Malta. Manag. Environ. Qual. 2011, 22, 463–485. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, W.; Li, J. Who are the low-carbon activists? Analysis of the influence mechanism and group characteristics of low-carbon behavior in Tianjin, China. Sci. Total Environ. 2019, 683, 729–736. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Marinescu, C.; Ciocoiu, C.N.; Cicea, C. Drivers of eco-innovation within waste electrical and electronic equipment field. Theor. Empir. Res. Urban Manag. 2015, 10, 5–18. [Google Scholar]

- Brown, T.A. Confirmatory Factor Analysis for Applied Research; The Guilford Press: New York, NY, USA, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Chin, W.W. The partial least squares approach for structural equation modeling. In Methodology for Business and Management. Modern Methods for Business Research; Marcoulides, G.A., Ed.; Lawrence Erlbaum Associates Publishers: Mahwah, NJ, USA, 1998; pp. 295–336. [Google Scholar]

- Li, C.-H. Confirmatory factor analysis with ordinal data: Comparing robust maximum likelihood and diagonally weighted least squares. Behav. Res. 2016, 48, 936–949. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dash, G.; Paul, J. CB-SEM vs PLS-SEM methods for research in social sciences and technology forecasting. Tech. Forecast. Soc. Chang. 2021, 173, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anderson, J.C.; Gerbing, D. Structural equation modeling in practice: A Review of recommended two-step approach. Psychol. Bull. 1988, 103, 411–423. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schumacker, R.E.; Lomax, R.G. A beginner’s guide to structural equation modeling. Technometrics 2004, 47, 522. [Google Scholar]

- Danish, M.; Ali, S.; Ahmad, M.A.; Zahid, H. The influencing factors on choice behavior regarding green electronic products: Based on the green perceived value model. Economies 2019, 7, 99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hair, J.F.; Black, W.C.; Babin, B.J.; Anderson, R.E. Multivariate Data Analysis; Prentice Hall: Upper Saddle River, NJ, USA, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Hair, J.F.; Hult, G.T.M.; Ringle, C.M.; Sarstedt, M.; Danks, N.P.; Ray, S. Partial Least Squares Structural Equation Modeling (PLS-SEM) Using R; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Fornell, C.; Larcker, D.F. Evaluating structural equation models with unobservable variables and measurement Error. J. Mark. Res. 1981, 18, 39–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hair, J.F.; Ringle, C.M.; Sarstedt, M. PLS-SEM: Indeed, a Silver Bullet. J. Mark. Theory Pract. 2011, 19, 37–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Diamantopoulos, A.; Siguaw, J.A. Formative versus reflective indicators in organizational measure development: A comparison and empirical illustration. Br. J. Manag. 2006, 17, 263–282. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sarstedt, M.; Ringle, C.M.; Hair, J.F. Partial Least Squares Structural Equation Modeling. In Handbook of Market Research; Homburg, C., Klarmann, M., Vomberg, A., Eds.; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Construct | Item | Measurement | Loading | α/CR/AVE |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Product features (PF) [45,46,55] | PF1 | Quality | 0.864 | 0.880/0.886/ 0.798 |

| PF2 | Guarantees | 0.898 | ||

| PF3 | Duration of use | 0.916 | ||

| Preference for long-lasting products (PLLP) [39,40,41] | I am interested in buying EEP for which… | 0.898/0.927/ 0.823 | ||

| PLLP1 | …I can buy spare parts | 0.944 | ||

| PLLP2 | …I have solutions to repair | 0.961 | ||

| PLLP3 | …I can improve its functionality | 0.809 | ||

| External factors (EF) [32,33,36,60] | The factors that influence the intention to recycle EEP are: … | 0.873/0.889/ 0.763 | ||

| EF1 | …legislation | 0.918 | ||

| EF2 | …public policies | 0.930 | ||

| EF3 | …NGOs involved in recycling EEP | 0.763 | ||

| Recovering and recycling intentions (RRI) [12,61] | When I stop using EEP, I… | 0.900/0.918/ 0.818 | ||

| RRI1 | …am trying to find recovery and recycling solutions | 0.844 | ||

| RRI2 | …am trying to find collection centers | 0.930 | ||

| RRI3 | …dispose them at collection centers | 0.935 | ||

| Preference for ecological products (PEP) [48,50] | I buy EEP that… | 0.881/0.903/ 0.787 | ||

| PEP1 | …have eco-labels | 0.926 | ||

| PEP2 | …have ecological packaging | 0.935 | ||

| PEP3 | …participate in take-back initiatives | 0.793 | ||

| Green behavior intentions (GBI) [39,40,41] | My intention is to… | 0.899/0.916/ 0.815 | ||

| GBI1 | …diminish pollution with EEP waste | 0.936 | ||

| GBI2 | …help in reducing the carbon footprint | 0.932 | ||

| GBI3 | …carefully read the EEP sales contracts to collect the necessary information | 0.838 | ||

| Construct | PF | PLLP | EF | RRI | PEP | GBI |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| PF | 0.893 | |||||

| PLLP | 0.587 | 0.907 | ||||

| EF | 0.396 | 0.431 | 0.873 | |||

| RRI | 0.377 | 0.388 | 0.499 | 0.904 | ||

| PEP | 0.490 | 0.483 | 0.508 | 0.700 | 0.887 | |

| GBI | 0.521 | 0.525 | 0.450 | 0.642 | 0.768 | 0.903 |

| Effects | Path Coefficient | Standard Deviation | Z Value | p-Value | Hypotheses |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| EF→PLLP | 0.164 | 0.053 | 3.188 | 0.001 *** | H1—confirmed |

| GBI→PLLP | 0.246 | 0.058 | 4.264 | 0.000 *** | H2—confirmed |

| PF→PLLP | 0.393 | 0.053 | 8.127 | 0.000 *** | H3—confirmed |

| EF→PEP | 0.107 | 0.037 | 2.914 | 0.004 *** | H4—confirmed |

| GBI→PEP | 0.48 | 0.043 | 11.001 | 0.000 *** | H5—confirmed |

| PF→PEP | 0.082 | 0.043 | 2.051 | 0.040 ** | H6—confirmed |

| RRI→PEP | 0.308 | 0.049 | 6.851 | 0.000 *** | H7—confirmed |

| EF→RRI | 0.263 | 0.037 | 6.47 | 0.000 *** | H8—confirmed |

| GBI→RRI | 0.524 | 0.037 | 12.804 | 0.000 *** | H9—confirmed |

| EF→GBI | 0.45 | 0.042 | 10.936 | 0.000 *** | H10—confirmed |

| EF→PF | 0.396 | 0.049 | 7.633 | 0.000 *** | H11—confirmed |

| Path | Interactions | Coefficient | Standard Deviation | Z Value | p-Value | Hypotheses |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| EF-PF-PLLP | H11 × H3 | 0.156 | 0.031 | 5.200 | 0.000 *** | H12—confirmed |

| EF-GBI-PLLP | H10 × H2 | 0.111 | 0.028 | 4.090 | 0.000 *** | H13—confirmed |

| EF-GBI-PEP | H10 × H5 | 0.216 | 0.028 | 7.908 | 0.000 *** | H14—confirmed |

| EF-PF-PEP | H11 × H6 | 0.032 | 0.017 | 1.970 | 0.049 ** | H15—confirmed |

| EF-RRI-PEP | H8 × H7 | 0.081 | 0.018 | 4.476 | 0.000 *** | H16—confirmed |

| EF-GBI-RRI | H10 × H9 | 0.236 | 0.027 | 8.050 | 0.000 *** | H17—confirmed |

| EF-GBI-RRI-PEP | H10 × H9 × H7 | 0.073 | 0.013 | 5.481 | 0.000 *** | H18—confirmed |

| Path | Interactions | Coefficient | Standard Deviation | Z Value | p-Value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Total_EF-PF-PLLP | H1 + H11 × H3 | 0.320 | 0.050 | 6.585 | 0.000 |

| Total_EF-GBI-PLLP | H1 + H10 × H2 | 0.275 | 0.050 | 5.663 | 0.000 |

| Total_EF-GBI-PEP | H4 + H10 × H5 | 0.322 | 0.043 | 7.634 | 0.000 |

| Total_EF-PF-PEP | H4 + H11 × H6 | 0.139 | 0.037 | 3.817 | 0.000 |

| Total_EF-RRI-PEP | H4 + H8 × H7 | 0.188 | 0.035 | 5.436 | 0.000 |

| Total_EF-GBI-RRI-PEP | H4 + H10 × H9 × H7 | 0.179 | 0.035 | 5.193 | 0.000 |

| Path | Interactions | Coefficient | Standard Deviation | Z Value | p-Value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Grand_total EF-PEP | H8 × H7 + H10 × H9 × H7 + H4 + H10 × H5 + H11 × H6 | 0.508 | 0.036 | 14.181 | 0.000 |

| Grand_total EF-PLLP | H10 × H2 + H1 + H11 × H3 | 0.431 | 0.042 | 10.513 | 0.000 |

| Grand_total EF-GBI-RRI | H8 + H10 × H9 | 0.499 | 0.037 | 12.444 | 0.000 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Vaduva, F.; Csorba, L.M.; Dabija, D.-C.; Lăzăroiu, G. The Impact of Public Policies and Civil Society on the Sustainable Behavior of Romanian Consumers of Electrical and Electronic Products. Sustainability 2024, 16, 1262. https://doi.org/10.3390/su16031262

Vaduva F, Csorba LM, Dabija D-C, Lăzăroiu G. The Impact of Public Policies and Civil Society on the Sustainable Behavior of Romanian Consumers of Electrical and Electronic Products. Sustainability. 2024; 16(3):1262. https://doi.org/10.3390/su16031262

Chicago/Turabian StyleVaduva, Florin, Luiela Magdalena Csorba, Dan-Cristian Dabija, and George Lăzăroiu. 2024. "The Impact of Public Policies and Civil Society on the Sustainable Behavior of Romanian Consumers of Electrical and Electronic Products" Sustainability 16, no. 3: 1262. https://doi.org/10.3390/su16031262

APA StyleVaduva, F., Csorba, L. M., Dabija, D.-C., & Lăzăroiu, G. (2024). The Impact of Public Policies and Civil Society on the Sustainable Behavior of Romanian Consumers of Electrical and Electronic Products. Sustainability, 16(3), 1262. https://doi.org/10.3390/su16031262