1. Introduction

The International Labor Organization (ILO) proposed decent work in 1999. Decent work aims to promote decent and productive work opportunities for all genders in conditions of freedom, equality, safety, and human dignity. The proposal of decent work is of practical significance for social, organizational [

1], and individual development [

2]. By contributing to a more equitable, just, and humanistic approach to work, decent work helps reach a fairer globalization goal. At the organizational level, decent work provides us with guiding directions for the rational and legitimate use of human capital [

3]. Understanding decent work at the individual level is vital to transforming decent work from theory to reality [

2]. Decent work may provide a general framework to structure workers’ freedom, equality, safety, and human dignity. Although the expanding literature on this issue has provided a clear understanding, developing a commonly accepted definition of decent work from an individual level still needs to be solved. Another problem is to measure based on its links with knowledge workers. Despite various measurement tools in the literature, almost all have some limitations. In order to better understand and measure decent work perception for knowledge workers, a new measurement of decent work perception is needed. This current study aims to fill this gap by providing a new scale to measure decent work in terms of the perceptions of knowledge workers.

The data for this study were collected from knowledge workers in China. The ILO and China signed the “China Decent Work Country Program 2016–2020” in 2017, which sets out the areas of cooperation between China and the ILO for five years. Chinese workers’ decent work status has attracted international attention. Research results show that 12.9% of Chinese workers work over 10 h overtime per week [

4], far exceeding international average working hours. With the popularity of mobile Internet in the workplace, knowledge workers can effectively use the Internet to work anytime and anywhere, extending workers’ working hours and making overwork more invisible [

5]. Overworking has a significant negative effect on society [

6], organizations [

7], and individuals [

8,

9]. It squeezes the public’s time for leisure consumption and triggers an imbalance between work and family relationships from a social perspective, sacrifices employees’ health [

10,

11], decreases innovation-driven development incentives from an organizational perspective [

12], and violates workers’ right to life and health from an individual perspective [

8,

9]. As a result, overworking impacts sustainable social and human development [

13,

14].

Decent work has received attention from academics since its proposal in 1999. Studies have found that decent work promotes socioeconomic development and helps achieve strategic organizational goals. Decent work can significantly contribute to labor market stability [

15], socioeconomic competitiveness [

16], and the human development index [

17]. Moreover, decent work can predict employee engagement [

18], self-efficacy [

19], organizational commitment [

20], voice behavior [

21], innovative behavior, and job performance [

22,

23]. Surprisingly, organizational behavior and human resource management researchers have seldom directly studied knowledge workers’ decent work perception, although they have long realized that knowledge workers are critical to improving the competitiveness of organizations in the knowledge economy [

24]. The reason for the lack of management research on knowledge workers’ decent work perception is the inconsistency in the measurement of decent work. Since 1999, decent work measurement has been developed at the macro and micro levels. Ferraro et al. first proposed a decent work questionnaire (DWQ) consisting of thirty-one indexes from the four pillars of rights, employment equity, social dialogue, and social protection [

25]. This measurement is based on the ILO macro definition of decent work. Duffy et al. developed a decent work scale (DWS) based on the Psychology of Working Theory (PWT) from the micro-level [

26]. DWS consists of five dimensions: safe working conditions, security of health care, adequate salary, free time and rest hours, and organizational value [

26]. Yan et al. designed a decent work perception scale (DWPS) for knowledge workers at the micro-level of DWP [

27]. This scale is developed from grounded theory and contains 4 dimensions and 13 items. Job security (JSE), respect and support (RSU), self-value (SVA), and professional skills (PSK) are the four dimensions.

While offering valuable information, the objective measures of decent work have several limitations. First, decent work’s structural dimensions are complex, inconsistent, and difficult to recognize and disseminate. The 5-dimensions of Duffy et al. and the 7-dimensions of Ferraro et al. are complex [

25,

26], with too many items in the scale, resulting in low accuracy of subjects’ responses when collecting data through the questionnaire. Also, current scales need a solid foundation for qualitative research. The scales of Duffy et al. and Ferraro et al. were borrowed directly from established literature or objective indicator systems and lacked a solid qualitative study as a theoretical basis. Last, existing measurements are constructed on a small sample size for interviews and questionnaires. Yan et al.’s scale is based on qualitative research to develop DWPS scales [

27]. However, the sample size of interviews and questionnaires is small, and the generalizability and representativeness of their findings need to be improved.

The research questions of this study are: (1) How to construct a reasonable theoretical framework for decent work perception based on a standard scale development procedure? (2) How to construct a scale of decent work perception that is easy to remember and disseminate? (3) Is the newly developed scale valid and reliable? Based on these research questions, this paper is organized as follows:

Section 2 discusses current studies on decent work concept and scale development.

Section 3 explains the exploratory survey of generating codes of decent work perception based on the in-depth interview, pilot survey of item generating and selecting, and formal survey validating the decent work perception scale.

Section 4 compares the previous research results with the decent work perception scale and indicates that self-esteem is a distinct dimension proposed in decent work for knowledge workers.

Section 5 discusses the main conclusions of this research and the theoretical and practical applications of a decent work perception scale in the research field and management practice.

Section 6 discusses the limitations of this study and predicts future research directions.

3. Research Methodology

3.1. Research Philosophy

According to Saunders [

45], research philosophy can be classified into positivism, realism, interpretivism, and pragmatism. Interpretivism refers to a study that aims to comprehend the differences among individuals. Such research is often socially constructed and focuses on subjective meanings and social phenomena. Additionally, researchers are an integral part of the subject being studied and cannot be detached from it; therefore, their perspectives will inevitably be subjective. The commonly employed data collection techniques include small sample sizes, in-depth interviews, and qualitative methods. The underlying philosophy guiding this study is interpretivism since perceptions of decent work pertain to individuals’ internal hidden sentiments about their occupation.

3.2. Research Design

As

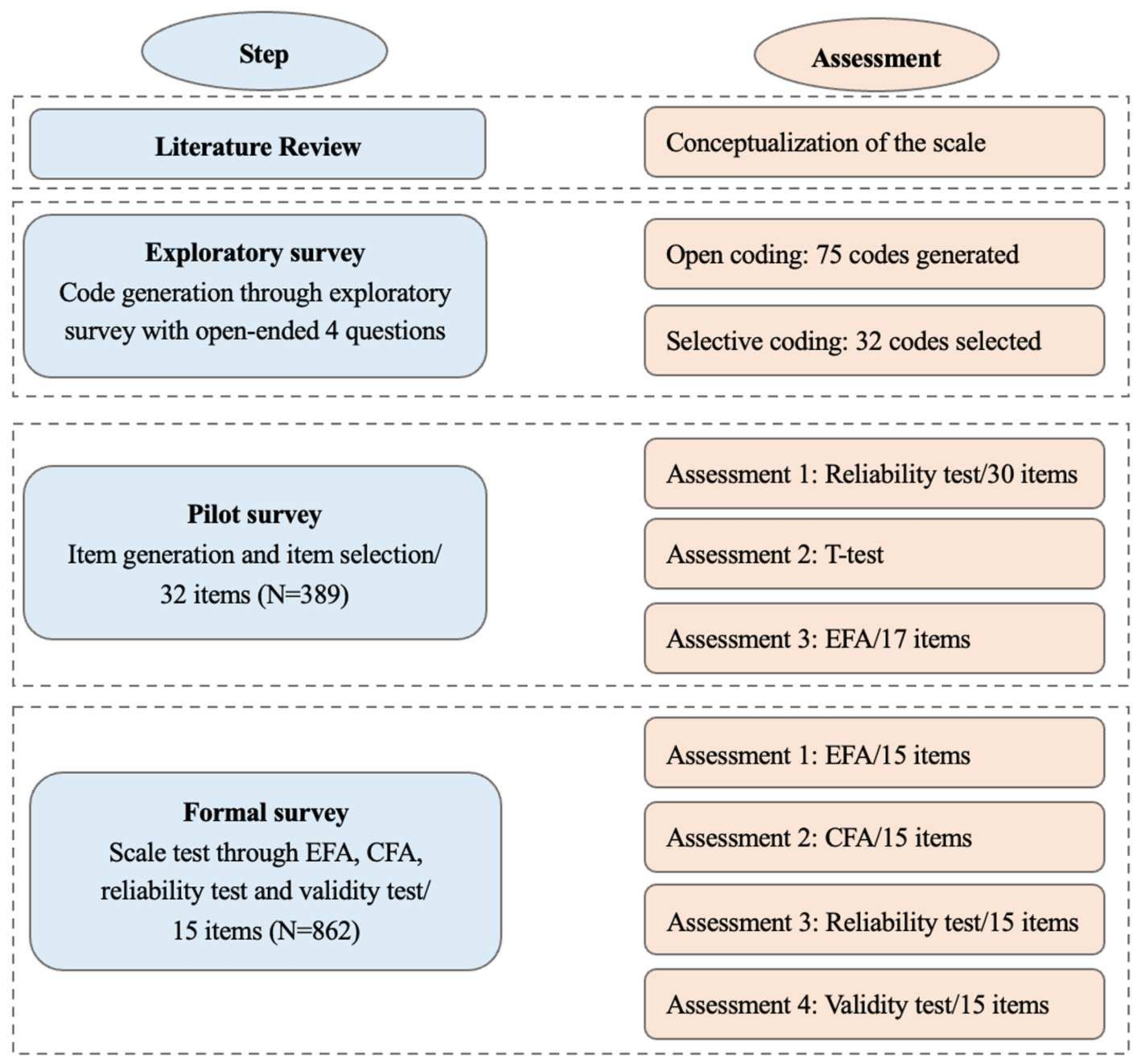

Figure 1 indicates, the scale development process strictly followed the scale development procedure proposed by Bagozzi et al. [

46]. Step 1 is a literature review. We have reviewed the general goal of decent work proposed by the ILO in 1999, which is also the definition of decent work. However, there are macro-level perspectives and micro-level perspectives in decent work measurement. Decent work in this study adopts the micro-level perspective. Therefore, decent work is also called decent work perception. It should be noted that this typology can only be used to build the foundation for decent work perception. Step 2 is an exploratory survey. An exploratory survey is conducted to construct the conceptual framework and create new items for decent work. As a result, a qualitative research method, proposed by Glaser and Holton [

47], is required. We conducted semi-structured interviews with thirty participants to answer four questions about decent work. Step 3 is a pilot survey. In this stage, we collected 389 questionnaires and analyzed the data using exploratory factor analysis to screen the items in the pool and verify the scale’s reliability. Step 4 is a formal survey. In this survey, a total of 862 valid questionnaires were collected. The scale was subjected to rigorous testing including exploratory factor analysis, confirmatory factor analysis, reliability assessment, and validity examination.

3.3. Ethics Statement

This research was approved by the Academic Ethics Committee in 2023. The reference code for this admission was 2023051201. The research will not pose any daily risks or provide any direct benefits to the respondents. To some extent, this study can provide evidence for understanding decent work for knowledge workers. It can also provide new ideas for understanding knowledge workers’ current work situation and improving industrial relations. Before the in-depth interview and the survey, the respondents will receive an oral consent form. Meanwhile, the researchers promise that respondent answers will be recorded anonymously and kept in encrypted files. All data will be only be used academically.

3.4. Exploratory Survey

We conducted exploratory surveys to generate codes with in-depth interviews. The in-depth interview was conducted in the following steps. First, the interviewer explained the research purpose and research content to the respondents. Then, the respondents were asked whether they were willing to be interviewed. If the respondents agreed to participate in the interview, they were orally informed about the consent form and confidentiality agreement. Finally, the formal interview began. The interview was recorded and transcribed with the respondents’ consent.

The interview lasted for 60 min and contained semi-structured questions. The interview contained two parts: the introduction questions and the core questions. Introduction questions were: (1) What position do you hold? How long have you been in this position? How long have you worked in this organization? (2) Can you describe the job content of your current position? Core questions were: (1) Which jobs do you feel are decent (please give examples), and why do you feel they are decent? (2) Which jobs do you consider are not decent (please give examples), and why do you believe they are not decent? (3) Do you agree that your current job is decent, and how can you make your current job (more) decent? (4) What characteristics do you think a decent job should have, and why do these characteristics make you feel decent? We identify knowledge workers by the respondents’ job content.

3.4.1. Samples

The target objective of this study is knowledge workers. Knowledge workers, initially proposed by Peter Drucker, are individuals who possess expertise in manipulating and applying symbols and concepts, relying on knowledge and information as the foundation of their professional endeavors. In this study, we specifically recruited knowledge workers with a minimum of a bachelor’s degree, who actively engage in knowledge sharing and creation within their work environment, and primarily perform cognitive tasks rather than physical labor. We recruited 30 respondents to participate in the in-depth interview by releasing information online. After receiving the respondent’s consent to participate in the interview, the academics evaluated the respondent’s age, gender, organization type, tenure, occupation, and other information. Participants will continue the interview only after meeting the above criteria for knowledge workers. The 30 respondents came from 30 organizations in different industries, including real estate, banking, securities, insurance, universities, and government. The respondents’ positions included product managers, human resource managers, teachers, accountants, finance specialists, sales, and administrative personnel. Among them, 18 were male, 12 were female, and their tenures ranged from 3 to 20 years. The demographic character of the sample shows that the respondents are diverse and representative in terms of industry, position, and tenure.

3.4.2. Coding Procedure

After data collection, we used substantive coding methods to analyze the data, including open and selective coding [

48]. The results of open coding and selective coding can be found in

Appendix A.

Step 1 is open coding. It refers to the coding process of data from the raw materials sentence-by-sentence and line-by-line. Open coding abstracts concepts without omitting critical information. In the open coding process, this study used a manual approach to encode the interview texts of 30 respondents. This was carried out to enhance the extraction of codes by repeatedly organizing, comparing, and analyzing them to eliminate irrelevant and redundant information about decent work. Researchers extracted the codes from the respondent’s description by identifying which aspect of decent work it belongs to. Ultimately, this study identified 877 labels after data analysis of the raw material and further derived 75 codes. We chose the 13 open coding extractions as an example, shown in

Table 1. To describe the code abstraction process, we take “realization of self-value” as an example. Representing the 22nd code in the 6th raw materials, original data 06-22 indicated, “I think decent work should allow me to realize self-value and life value.” We identified the code “work can realize self-value” from sentences 06-22. Original data 08-05 stated, “I think the work that reflects their values is the most decent. I particularly admire firefighters”. Original data 20-21 indicated, “I have value, and I will be respected.” Our extracting code was “self-worth can gain respect.” All three original data were related to self-value. We obtained the concept of self-value realization by opening coding.

Step 2 is selective coding. We use selective coding to purify the concepts generated from open coding because the initial information gathered from open coding is ambiguous. Selective coding extracts core concepts by filtering codes, which are more directional, specific, and theoretical [

47]. Based on the definition of decent work and the features of knowledge workers, this study deleted concepts with a frequency of less than three. Finally, we extracted 32 items, classified into 5 dimensions (see

Table 2), which differs from previous research results. First, we found that knowledge workers understand decent work in terms of social status in the newly conducted survey. They perceive decent work to be related to social status [

49], the most recent finding in our survey. As a result, we added the social status dimension to the new decent work structure. Second, we revised respect and support as support and renamed the dimension of professional skills as skills based on the new data.

3.4.3. Coding Results

As a result of the in-depth interviews, this study constructs a structural dimension of the perception of decent work through open coding and selective coding, which is elaborated as follows.

(1) Security. When talking about their understanding of decent work during the interviews, the respondents mentioned that jobs that are not easily dismissed, guarantee income and benefits, are safe in the workplace, match income to effort, and have well-organized systems can be considered decent work. According to respondents, this study extracts financial security, institutional security, and safety as the first dimension of “security,” i.e., financial security, institutional security, and safety that workers can feel at work [

26,

44,

50].

(2) Support. During the interviews, respondents suggested that decent workers should have access to job support from both outside and inside the organization. Support from outside the organization is evident in the fact that the clients and customers served by the work are well educated. Clients and customers can provide job support and assistance from a position of mutual benefit. Intra-organizational support is reflected in organizational support (e.g., being valued by the organization, having power and resources), superior support (receiving help and support from superiors), and co-worker support (having a positive relationship with co-workers). In line with this, this study extracts internal and external organizational support into the second dimension, “support,” i.e., workers can feel diversified support from outside and inside the organization at work [

2].

(3) Skills. According to the respondents’ replies, decent work should also be reflected in individual professional skills, job requirements, and work ethics. First, an individual’s professional skills should be applied to the working process, which is not easily replaced by machines and artificial intelligence (AI). Second, the work needs to be innovative and challenging and able to meet complex work requirements. Finally, decent work requires good professional ethics and qualifications. In line with this, this study extracts professional skills, job requirements, and professional ethics as the third dimension of “skills” [

44,

51,

52].

(4) Self-value. In the in-depth interviews, the respondents suggested that decent work should encompass self-determination, work autonomy, and development opportunities for knowledge workers. Knowledge workers’ self-determination refers to their ability to create and realize value at work and the resulting sense of accomplishment and pleasure. Job autonomy means knowledge workers have autonomy over work time and empowerment from leaders, which stimulates creativity. Third, development opportunities refer to identifying opportunities and effectively utilizing opportunities to improve employability. As a result, this study extracts self-determination, work autonomy, and development opportunities as the fourth dimension of perceived decent work “self-value” [

26,

53].

(5) Social status. The respondents believed that decent work’s social status should be reflected in three aspects: social image, work image, and personal image. To enhance the social image, the work should be legal, and the organization should enjoy an excellent societal reputation. The image of a person should be reflected in his or her occupation, work content, and workplace image. Regarding personal image, the implementation of decent work can facilitate employees in acquiring recognition, respect, and job satisfaction throughout the work process. In line with this, this study defines the fifth dimension of decent work as “social status,” inducing the ability of workers to obtain a sound social image, work image, and personal image through their work [

49,

54].

3.5. Pilot Survey

The pilot survey was two-sided: item generation and selection. Based on the 5S structural dimensions of knowledge workers’ perception of decent work, the researchers developed declarative sentences as the initial question pool. This was achieved by combining in-depth interviews and related literature. To ensure content validity, we invited two scholars specializing in human resource management to classify the initial question items back-to-back. The categorizing principle is “whether this item is related to its dimension”. If two experts categorize the question items in the same way, they were identified as measurement questions. If the question was not categorized consistently, the two experts discussed deleting or adjusting its categorization until all questions were organized consistently. Subsequently, we started with another round of evaluation on the principle of “no semantic overlap.” We merged or deleted the overlapping questions. After further purification, 32 items were retained.

3.5.1. Participants Selection

In this study, we developed an initial questionnaire using a 5-point Likert scale. The options for each question included “1 strongly disagree”, “2 disagree”, “3 neutral”, “4 agree”, and “5 strongly agree”. The questionnaires were distributed through an online platform, Questionnaire Star. The researcher set an RMB 1 bonus for each questionnaire as feedback to the survey participants. Based on the standards we followed, we selected a valid questionnaire. First, a knowledge worker should have a bachelor’s degree or above. Second, the response time should be more than one minute. Third, there are at most five consistent responses. All participants were sent a written consent form before taking the online survey. If participants agreed with the consent form, the survey could proceed.

The pilot survey was distributed over ten days from 5 July to 15 July 2023. We collected 480 questionnaires, and 389 were valid. The valid rate is 81.04%. According to the demographic statistical analysis, males were 42.4%, and females were 57.6%. The percentage of those aged 25 years and below was 8.8%, 26.8% aged 26–35 years, 37.1% aged 36–45 years, and 27.3% who were 46 years and above. The percentage of those with an education level of college or below is 11.7%, with a bachelor’s degree at 36.6%, a master’s degree at 27.3%, and a doctoral degree at 24.4%.

3.5.2. Data Analysis

Step 1: Reliability test for the initial scale. The initial question items were purified according to the following standards: (1) CICT is not significant. We should eliminate the items with a CICT value less than 0.50. Thus, S53 was deleted with a CICT value of 0.402; (2) Cronbach’s α after deleting an item is higher than the overall Cronbach’s α without deleting any item [

55]. We deleted S31 because Cronbach’s α after deleting the item is 0.933, higher than the dimensional Cronbach’s α 0.932 (see

Table 3). Ultimately, we retained 30 questions. Each dimensional Cronbach’s α is higher than 0.7, indicating an adequate internal reliability. It is noted that the reliability tests were carried out at the 95% significance level.

Step 2: T-test. The 27% cutoff was used as a grouping boundary. We ranked the first 27% of the scale total score in the sample data as the highest subgroup and the final 27% as the lowest subgroup. Each group had 105 questionnaires. We compared differences between the two extreme groups. The participants’ replies to one specific question significantly differed between the two groups when the p-value was lower than 0.05, indicating that the question distinguishes different groups. Therefore, questions with a significant p-value should be retained. If not, the questions should be deleted. According to the t-test results between the extreme groups, all questions have a significant p-value, indicating that they are well-identified. Therefore, all questions are retained.

Step 3: EFA of the initial scale. First, we conducted KMO and Bartlett tests to examine whether the initial scale was suitable for EFA. KMO is 0.969, and Bartlett’s

p-value was significant, indicating common factors among the questions. Second, we constructed Principal Component Analysis (PCA). We set five common factors extraction rules and applied orthogonal rotation using the maximum variance method. The results of EFA revealed low loadings, multi-loadings, and misallocation (see

Table 4). Therefore, we screened the questions for each situation. We deleted S15, S51, and S52 because the loadings on any factor were lower than 0.5. Multi-loading occurred when the question item loaded on both factors with a value greater than 0.5. As a result, we eliminated S13, S36, and S47 because of multi-loading. The misallocation of loadings indicates that the item did not exhibit loadings exceeding 0.5 on the predetermined factors, but instead demonstrated loadings surpassing 0.5 on alternative factors. We deleted S16, S24, S25, S26, S34, S44, and S54 because of misallocation. Finally, we kept 17 question items as the final scale with loadings higher than 0.5 on each factor. This indicates that the extracted common factor explained the measured variables well.

It should be noted that the fifth factor was originally named social status and contained three components: social image, work image, and personal image. However, according to the EFA, the final retained items were all related to personal image. This indicates that knowledge workers value self-esteem, recognition, and satisfaction. Thus, we renamed the fifth dimension as self-esteem. The results also indicated that knowledge workers were eager for inner spiritual desire, which differed from other workers.

3.6. Formal Survey

3.6.1. Data Collection

A formal survey was conducted to verify the reliability and validity of the scale through EFA, CFA, and reliability and validity tests. The questionnaire was distributed from 1 to 15 September 2023, on the online platform Questionnaire Star. The distribution of this questionnaire took one and a half months, and 969 questionnaires were collected. All participants were sent a written consent form before taking the online survey. Participants could proceed with the survey if they agreed to the consent form in advance. Finally, there were 862 valid questionnaires, and the validity rate of the questionnaires was 88.96%.

3.6.2. Descriptive Statistical Analysis

This questionnaire was distributed to a large number of subjects in order to ensure a wide range of sample sizes and distributions. Descriptive statistical analysis shows the sample consisted of 42.1% males and 57.9% females. In terms of education, 9.9% had a college degree or less, 57.7% had a bachelor’s degree, 22.0% had a master’s degree, and 10.4% had a PhD. More than 90% of the samples had a bachelor or higher, which is identical with the definition of knowledge workers as defined in the study. The age distribution is mainly concentrated in 26–45 years old, of which 26–35 years old accounted for 49.8%, and 36–45 years old accounted for 30.2% (see

Table 5). These data show that knowledge workers are predominantly middle-aged and young, which is in line with the inverted U-shape curve of human capital. The distribution of tenure is more dispersed; 6.7% are below 0.5 years, 6.8% are between 0.5 and 1 year, 21.5% are between 1.01 and 3 years, 16% are between 3.01 and 5 years, 18.4% are between 5.01 and 10 years, and 30.5% are more than 10 years. There is a wide range of tenure among samples, which indicates that knowledge workers are more loyal to careers than to organizations. The industry distribution of the sample covers banking (22%), insurance (31.4%), securities and investment (5.7%), communications and the internet (3.9%), education and training (24.2%), and smart manufacturing (2.7%). These industries are strategic emerging industries that have been vigorously developed by the Chinese government in recent years, attracting many knowledge workers. In terms of the distribution of the organization type, private enterprises accounted for 11.4%, state-owned enterprises accounted for 36.4%, government departments accounted for 19.7%, public services accounted for 17.4%, and foreign-funded enterprises accounted for 10.6%. The sample covered all different types of organizations.

3.6.3. Exploratory Factor Analysis (EFA)

We conducted an EFA on the formal questionnaire utilizing SPSS 26.0. First, we conducted KMO and Bartlett tests to clarify whether the data were suitable for EFA. Research results showed that KMO was 0.949, and the Bartlett test result of χ

2 was 10,603.080, indicating that common factors existed among the items. The overall variance explained was 78.046%. Second, we used PCA to extract factors. We set five common factors extraction rules and applied Promax rotation. The results are shown in

Table 6. We deleted S35 and S46 as they were misallocated. Professors from human resource management were consulted to confirm the dimensions and items that were misloaded. The experts suggested that S35 and S46 should be deleted because the item content was inconsistent with the loaded dimensions. As a result, we retained 15 items with loadings higher than 0.5 on each factor. Therefore, this study constructed the 5S dimensions of decent work perception as follows.

(1) S1 is security, including four items. They are “The job is secured”, “The income is secured”, The job is safe and secured”, and “One should feel equitable about the distribution system”.

(2) S2 is support, consisting of three items. They are “One can be respected by the organization”, “One should have resources and power at work”, and “One can get support and help from work”.

(3) S3 is self-value, including two items. They are “The job helps one realize his or her self-value” and “The job helps one create value”.

(4) S4 is skills, containing four items. They are “The job requires high competence,” “The job is creative”, “The job requires specialized skills and knowledge”, and “The job is challenging”.

(5) S5 is self-esteem with two items. They are “One can be respected and recognized for the job” and “One can be respected and satisfied with the job”.

3.6.4. Confirmatory Factor Analysis (CFA)

We used CFA to verify whether the 5S structure of decent work perception matches the formal survey data. We propose five test models as shown below:

M1: Single factor model means the 5S share the same latent variable (security + support + self-value + skills + self-esteem).

M2: The two-factor model means security, support, and skills share the same latent variable, while self-value and self-esteem share the same latent variable.

M3: The three-factor model suggests that security, support, and skills share the same latent variable, while self-value and self-esteem have separate latent variables.

M4: The four-factor model proposes that security and skills share the same latent variable, while support, self-value, and self-esteem have separate latent variables.

M5: The five-factor model hypothesizes that security, support, self-value, skills, and self-esteem all have their own latent variables.

We analyzed the data for model fit through the SPSSAU online statistical software platform (

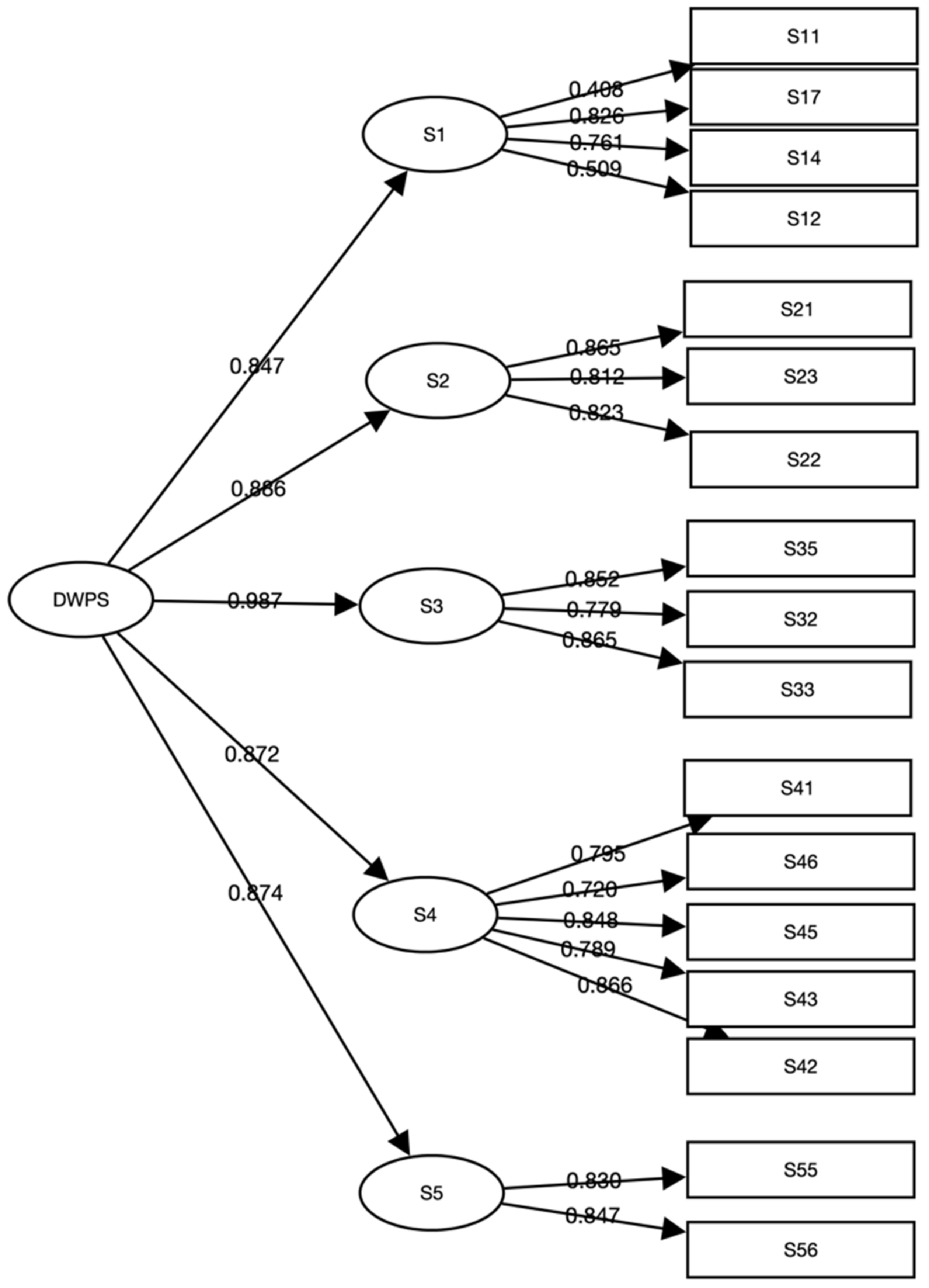

https://spssau.com). Results showed that M5 was the highest performing model among the five models, with χ

2 of 1226.025; GFI, RMSEA, RMR, CFI, and NFI were 0.859, 0.106, 0.045, 0.895, and 0.885, respectively (see

Table 7). GFI, CFI, and NFI are close to 0.9, RMSEA is close to 0.1, and RMR is less than 0.1, indicating that the five factor structure is well fitted with the data. CFA path coefficients are shown in

Figure 2.

3.6.5. Reliability Test and Validity Test

We utilized Cronbach’s α to test the overall reliability of the scale and CR to test the reliability of each dimension. Research results showed that Cronbach’s α was 0.944, indicating significant scale reliability. Meanwhile, 5S CR was 0.731, 0.872, 0.871, 0.902, and 0.826, respectively, indicating that each dimension was reliable. This shows that the whole scale and each dimension have high reliability.

Validity tests are examined for content and structural validity. Content validity is a test of measured items’ appropriateness. This study used qualitative research methods and expert consultation to ensure content validity and accuracy. We began by clearly defining the content of each topic on decent work perception according to the literature and in-depth interviews. Then, two experts in human resource management conducted a back-to-back review of the clarity and appropriateness of the language expression. Ultimately, the questionnaire was ensured to be of high content validity through a literature review, in-depth interviews, and expert review.

Structural validity is generally evaluated in terms of convergent and discriminant validity. AVE and CR usually examine convergent validity. An adequate convergent validity indicates that AVE is greater than 0.4 and CR is greater than 0.7. As can be seen from

Table 8, the CR of each dimension is 0.731, 0.872, 0.871, 0.902, and 0.826, respectively. All of them are greater than 0.7.

Furthermore, the AVE of the five dimensions is 0.422, 0.695, 0.693, 0.648, and 0.703, respectively. All are greater than 0.4, indicating good convergent validity. An effective discriminant validity indicates that the AVE square root for each factor is greater than the maximum correlation coefficient between that factor and the other factors.

Table 9 shows that the square roots of AVE are 0.649, 0.834, 0.833, 0.805, and 0.839, respectively. These values are significantly higher than the maximum value of the correlation coefficients. Therefore, the scale has an excellent discriminant validity.

4. Discussion

This research addresses a significant gap in the measurement of decent work at an individual level by proposing a novel conceptual framework, known as the 5S framework, specifically designed for knowledge workers. Furthermore, it lays the foundation for a comprehensive decent work framework that can be applied to various employee categories in different regions and countries. Additionally, this paper introduces a multidimensional scale to assess knowledge workers’ perception of decent work and examines its validity and reliability.

The findings of this study once again validate that the primary objective of decent work, safety and security, remains the paramount concern across diverse categories of workers. DWS with five dimensions and DWQ with seven indicators are both helpful for assessing decent work [

26,

40], emphasizing the importance of ensuring the occupational safety and job security of employees. Consistent with the conceptualization of DWS and DWQ, this study examines the security, support, and skills dimensions to ascertain that security and safety form the core components of decent work. The security dimension ensures the satisfaction of workers’ physical needs through the attainment of an adequate income [

29]. The support from organization and professional skills enhances employment safety in the labor market [

56].

This paper contributes the self-esteem dimension to the measurement of decent work for knowledge workers. Although DWPS has developed a four-dimensional model for knowledge workers, including job security, respect and support, self-value, and professional skills [

27], the model does not account for the pursuit of work meaning among knowledge workers [

42]. Consequently, the utilization of DWPS impose limitations on the assessment of decent work among knowledge workers. The inclusion of self-esteem in the measurement of decent work, as presented in the 5S model of this study, represents a significant advancement towards understanding the concept of decent work for knowledge workers. Self-esteem can be conceptualized as the level of self-esteem based on the organization and work activities. Employees’ perception of decent work is influenced by the inherent dignity associated with their organizational membership and job responsibilities. Previous research has demonstrated that the self-esteem of individuals, based on organization and work, significantly influences knowledge-sharing behavior and employee well-being among knowledge workers [

57,

58]. Therefore, the introduction of self-esteem enhances the comprehensiveness of measuring decent work.

This paper redefines the dimension of self-value in decent work. As indicated in the DWPS, the dimension of self-value encompasses a knowledge worker’s perception of autonomy within their work environment, their ability to create value, and the sense of accomplishment derived from their professional endeavors [

27]. The concept of self-value in DWPS focuses solely on value creation, while disregarding the importance of value realization. However, value creation and realization are the key process in the knowledge management [

59]. The self-value dimension in this study is defined as the process of cultivating and actualizing a sense of self-value experienced by knowledge workers within their professional roles, which is consistent with the conceptualization of knowledge management. The distinct dimension of self-esteem and redefined dimension of self-value reflect the unique perception of knowledge workers towards decent work, thereby enhancing the precision in measuring decent work.

6. Limitations and Directions for Future

The study’s limitations are as follows: (1) The sample was only validated on Chinese knowledge workers and did not involve samples from other countries. Due to the researcher’s time and budget constraints, the study only sampled within China, resulting in some sample selection limitations; (2) The 5S model was not compared with other work attitudes variables. This study’s dimensions of self-value, support, and self-esteem overlap with the dimensions of job satisfaction, well-being at work, and work meaningfulness. Due to time and energy constraints, this study did not establish a correlation validity test to differentiate between decent work perception and job satisfaction, well-being at work, and work meaningfulness.

Researchers can select samples of knowledge workers in multiple countries and regions to validate the questionnaire and revise the model in future research, which will significantly improve the questionnaire’s universality. Researchers can also compare and analyze decent work perception with job satisfaction, well-being at work, and work meaningfulness, which can define decent work clearly and lay a theoretical foundation for studying the antecedents and outcomes of decent work.