Abstract

This study explores the factors affecting proper garbage disposal in San Jose, Occidental Mindoro, Philippines, where approximately 49 tons of solid garbage are produced each day. This research was conducted using Structural Equation Modeling (SEM) to evaluate the variables affecting proper waste disposal in the community. The concept of this study follows the Theory of Planned Behavior (TPB), which refers to the idea that human beings act rationally depending on their behavioral aspects. A total of 300 respondents from the community of San Jose were acquired through an online questionnaire. The findings revealed that environmental knowledge significantly influences environmental concerns while it affects personal values and environmental attitudes. Intention was affected by personal attitudes and convenience, which also had an impact on waste management behavior. The result of the study could aid government institutions and households in incorporating effective solid waste management practices within the community. It is crucial to implement proper waste disposal procedures, as inadequate municipal waste management can lead to detrimental impacts on the environment, human health, and urban living standards. The study highlights the importance of community participation in developing effective strategies and improving waste management behavior in San Jose, Occidental Mindoro.

1. Introduction

Solid waste (SW) comprises wasted sludge, rubbish, refuse, and other solid items. It also comprises garbage from mining, agriculture, electronics, industry, municipalities, and home and commercial operations [1]. Solid waste management (SWM) is crucial in environmental issues or matters that have direct consequences for the environment, especially in air, water, soil, and public health. The global growth in trash generation complicates proper waste management activities [2].

Solid waste management (SWM) is critical in mitigating the effects of expanding urbanization on municipal and rural areas [3]. According to [4], it has become a serious environmental concern in emerging countries due to economic growth and increased consumerism, resulting in increased SW emissions. Most cities in low- and middle-income nations have been underperforming and could be performing better with adverse sustainability effects in urban growth and development.

The [5] report analyzing waste generation and recycling in countries within the Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development (OECD) found that only 17 of the 38 countries incinerate more waste than in landfills. South Korea (400 kg of waste per person), Denmark (845 kg of waste per person), and Germany (630 kg of waste per person) are among the top countries that incinerate more waste.

Solid waste management is a significant issue in the Philippines, with trash production increasing steadily. According to the 2018 Department of Environment and Natural Resources (DENR) report, the Philippines exhibited a daily generation of approximately 35,580 tons of garbage, corresponding to an annual output of about 14.66 million tons in 2014. Subsequent data from 2018 reveals an escalation to 16.6 million tons, positioning the Philippines as the third-largest annual solid waste generator among Southeast Asian countries [6].

According to [7], approximately 2.75 tons per day of solid waste is produced by businesses in the commercial sector produce around 2.75 tons of solid waste daily, with 0–60% biodegradable and recyclable, 19–20% recyclable, and 14–25% residual waste. On the other hand, the service sector produces a daily total of 70 kg of solid waste, containing 41% recyclable materials, 35% biodegradable matter, 23% residual waste, and a small amount of particular waste. Polyethylene (PET) bottles, assorted papers, tin cans, used magazines, and plastic cups are the most common recyclable materials, while diapers and napkins comprise most of the residual waste.

This study aims to determine the demographics of respondents to analyze factors affecting improper waste disposal in San Jose, Occidental Mindoro. It will evaluate community perception regarding waste disposal and recommend solutions to prevent environmental effects and health risks associated with improper waste disposal. This study follows the Theory of Planned Behavior’s (TPB) concepts and variables to assess individual perceptions regarding the waste disposal system along the community area. The results will help society and the government improve waste disposal practices in the community.

Research studies that have already been conducted have primarily concentrated on solid waste disposal techniques currently in use and are still endorsed as worthy of further study. As per [8], there is a need for new waste management approaches to maximize resource recovery and prevent environmental damage. This study uses Structural Equation Modeling to analyze factors that influence community perception of waste disposal and determine the demographics of respondents. The suggested questionnaire design techniques and proposed improvements to solid waste management may be helpful to researchers and decision-makers.

2. Theoretical Framework

2.1. Theoretical Framework and Variables

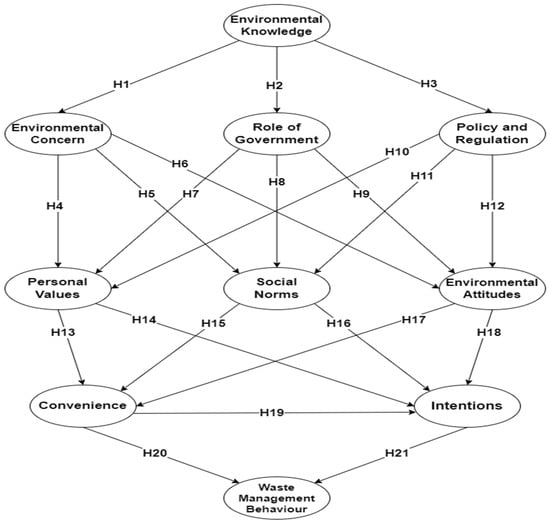

Figure 1 shows the theoretical framework for assessing the community’s perception of proper waste disposal. The researchers utilized the studies of [9], which incorporate the Theory of Planned Behavior (TBP), and [10], which states that policies and the role of the government are essential for proper waste disposal. Thus, these variables are Environmental Knowledge (EK), Environmental Concern (EC), Role of Government (RG), Policy and Regulation (PG), Personal Values (PV), Social Norms (SN), Environmental Attitudes (EA), Convenience (C), Intentions (I), and Waste Management Behavior (WMB) have been investigated in the current study. These factors were hypothesized to assess community perception in San Jose, Occidental Mindoro.

Figure 1.

Theoretical framework.

2.2. Relationship between Variables

This section will discuss the study hypothesis and the relationship between variables.

H1.

There is a significant relationship between Environmental Knowledge and Environmental Concern.

Individuals with greater environmental awareness were more likely to participate in pro-environmental actions, indicating a solid commitment to environmental protection and the value of education and understanding in altering people’s attitudes toward the environment and desire to act to protect it [11]. Environmental knowledge would indirectly increase pro-environmental behavior through environmental concern. Because interconnections are a central concept of environmental knowledge [12], acquiring environmental knowledge increases understanding of environmental issues, causes, and consequences, leading to a more excellent perception of nature and the human–nature relationship from an ecological perspective.

H2.

There is a significant relationship between Environmental Knowledge and the Role of Government.

The municipal government implements the central government’s environmental regulatory standards, significantly impacting the country’s overall environmental regulation effectiveness. If the local government fails to enforce environmental legislation, it can lead to continued environmental degradation and events. Good environmental governance requires a high public awareness of environmental hazards, a realistic challenge to address. The local government must handle environmental regulations during implementation [13].

H3.

There is a significant relationship between Environmental Knowledge and Policy and Regulation.

The experience of social movement organizations with regulatory institutions creates analysis, critique, and reform ideas. After that, movement organizations may re-enter the political process to put environmental proposals into policy. Thus, environmental knowledge engagement with policy-making institutions is a source of lived experience that informs reform proposals [14].

H4.

There is a significant relationship between Environmental Concern and Personal Values.

Private forest owners prioritize environmental benefits when managing forests. Understanding the reasons behind this can aid in creating policies that support environmental forestry. Personality traits and personal values heavily influence NIPF forest owners’ environmental concerns. This knowledge can assist in planning customized treatments that support environmental factors in forest management [15].

H5.

There is a significant relationship between Environmental Concerns and Social Norm.

According to [16], social norms affect the community and may influence the people or every individual in the community or its environment. Suppose the community or the environment has prioritized and focused on sustainability and environmental issues. In that case, the community will foster this behavior and may correlate with each other and engage in a sustainable environment.

H6.

There is a significant relationship between Environmental Concern and Environmental Attitudes.

Heads of households with pro-environmental attitudes and anticipated health benefits from energy efficiency retrofits are more likely to foresee financial benefits and fewer disruptions. Environmental concerns also increase the chance of planning for numerous retrofit types. However, lack of knowledge is a significant obstacle for some economic groups. This study emphasizes the importance of understanding energy performance retrofit benefits and hidden costs [17].

H7.

There is a significant relationship between the Role of Government into the Personal Values of individual citizens regarding Environmental Concerns.

Environmental concerns are a significant factor influencing citizens’ adoption of e-government services. Individuals with green lifestyles are motivated to adopt eco-friendly options. They may be more likely to use e-government services due to their environmentally conscious features, such as reduced paper usage. Such citizens are suggested to emphasize perceived usefulness, attitude, and trust more when considering e-government services than those with lower environmental concerns [18].

H8.

There is a significant relationship between the Role of the Government and the Social Norms of the people.

According to [19], governments can influence social norms by manipulating factors influencing behavior, such as adjusting choice architecture. This can be carried out through advertising campaigns and public information dissemination. However, personal and social norms can still prevail, as seen in the example of littering in a park. Governments must ensure accountability, fairness, and transparency when establishing norms while still upholding the ideals of representative democracy.

H9.

There is a significant relationship between the Role of Government in Environmental Attitudes and the behaviors of citizens.

Studies show that government quality positively affects public support for environmental measures and pro-environmental behaviors such as recycling. Research indicates that low corruption levels in governments are associated with higher levels of public support for environmental policy frameworks. However, few studies have examined the relationship between the quality of government and individuals’ daily pro-environmental behavior, as per findings of [20]. The importance of government institutions in encouraging pro-environmental measures and overcoming hurdles to collective action is also stressed by [21]. Their findings imply that bettering governmental performance can increase citizen engagement, which might increase environmental and climate initiatives.

H10.

There is a significant relationship between the Policy and Regulation and Personal Values.

Encouraging employee compliance with workplace regulations and corporate standards is essential. Corporate policies can influence personal values, including ethical and environmental considerations. In contrast, government policies can align with or challenge these values, such as social justice, environmental sustainability, public health, and safety. Numerous theoretical studies in risk research have identified the critical elements of trust [22]. In other words, they have investigated the types of evaluations that either strengthen or weaken trust in risk regulatory or other institutions.

H11.

There is a significant relationship between Policy and Regulation and Social Norms.

This embodies societal pressure, as well as rules and regulations. Wang et al.’s [23] study suggests that government regulations, formal organizations, and social pressure play crucial roles in promoting e-waste recycling in countries such as China and Vietnam. These factors help to encourage people to participate in recycling programs and increase their recycling intentions.

H12.

There is a significant relationship between Policy and Regulation and Environmental Attitudes.

Regional and municipal authorities do play a significant part in environmental policies. For instance, many countries delegate the responsibility of setting energy efficiency benchmarks for construction and controlling land utilization to local governments rather than the central governing body. Due to these various factors, the decentralization process could impact individuals’ environmental attitudes and formulation of environmental policy strategies [24].

H13.

There is a significant relationship between Personal Values and Convenience.

Contextual factors like convenience can impact the connection between individual norms and recycling behavior. Previous research has shown that rational and altruistic beliefs and attitudes influence individual waste management behavior. Understanding the environment might indirectly affect waste management by influencing environmental care, personal standards, and the perception of one’s ability to act. Additionally, the perception of behavioral control acted as an intermediary in the link between personal norms and waste management behavior [9].

H14.

There is a significant relationship between Personal Values and Intentions.

Millennials in India have less inclination to purchase green personal care goods due to lifestyle and personality factors. It indicates that consumer qualities connected to sustainability and lifestyle have a slight but positive influence on purchasing intentions. The study makes the minor but significant claim that personal values and lifestyle qualities influence Indian customers’ desire to purchase or intentions of environmentally friendly products [25].

H15.

There is a significant relationship between Social Norms and Convenience.

Social norms have a significant impact on human behavior, including recycling. People are more likely to recycle to gain social approval, but convenience is crucial in determining whether they will continue to recycle. Studies have shown that making recycling more convenient can increase the likelihood of continued engagement in recycling behavior, reinforcing social norms that support recycling [26].

H16.

There is a significant relationship between Social Norms and Intentions.

Social norms can influence an individual’s intentions, but other factors, such as individual values, attitudes, and beliefs, can mediate this relationship. Social norms are unwritten expectations that govern behavior and can be enforced through social sanctions. The pressure to conform to social norms can influence intentions, but individuals may only sometimes think of the norms affecting their behavior. The relationship between social norms and intentions is a complex topic extensively studied in social psychology [27].

H17.

There is a significant relationship between Environmental Attitudes and Convenience.

Environmental attitudes are characterized by [28] as psychological inclinations impacted by a person’s assessment of the natural world. The intention of a consumer to behave in the future is defined by [29] as behavioral intention. The convenience motive appears to favorably influence behavior, according to studies by [30].

H18.

There is a significant relationship between Environmental Attitudes and Intentions.

Research shows that individuals with strong environmental attitudes are likelier to engage in environmentally friendly behaviors and support sustainability initiatives. This positive correlation between environmental attitudes and intention is complex and influenced by social norms, personal beliefs, and resource access [31].

H19.

There is a significant relationship between Convenience and Intention.

Given that garbage cans are commonly prioritized in waste management research, their ease is frequently proposed as a reason for littering in specific locations [32]. Previous research has examined the factors influencing households’ intentions to sort waste. The view of infrastructure, facilities, and resources as convenient can boost the desire to engage in waste separation activities [33]. Studies have yet to look at how perceptions of the convenience of infrastructure affect home trash separation intentions estimates.

H20.

There is a significant relationship between Convenience and Waste Management Behavior.

Previous research on waste recycling did not consider the impact of social interactions and perceived convenience on sorting behavior. A recent study found that the intensity of information did not affect residents’ waste sorting choices, but the proportion of those who separated waste decreased as perceived convenience decreased. Negative information was ineffective in the context of low perceived convenience [34].

H21.

There is a significant relationship between Intentions and Waste Management Behavior.

In order to implement household waste separation (HWS), people must be conscious of, confident in, and in control of their abilities and capabilities. Perceived intentions have been shown in numerous studies to considerably increase a person’s ability to control their conduct [33]. It has been asserted that a person’s belief in their capacity to exercise self-control over a specific habit encourages engagement in that action and significantly impacts intentions [35].

3. Methodology

3.1. Participants

This study utilized a descriptive correlational research design in which the researcher will send online questionnaires via link survey using Messenger and the researcher’s social media accounts. The validity and reliability of the data in question are known to be enhanced by an increase in sample size [10]. The sample size of the research study was determined using Slovin’s formula. Slovin’s formula allows researchers to accurately sample populations to the desired extent, ensuring a reasonable level of accuracy in results by determining the required sample size [36]. Upon calculations, 300 respondents were acquired as participants required to answer the 60-item questionnaire.

Table 1 shows the demographic profile of 300 respondents in San Jose municipality. Most respondents were aged 18–29, male (58.3%), and senior high school graduates (45.3%). The majority had a monthly income of less than PHP 15,000 (66.3%) and came from Pag-asa, San Roque, Bagong Sikat, Labangan Poblacion, Caminawit, and Barangay 8.

Table 1.

Descriptive statistics of the respondents (N = 300).

3.2. Questionnaires

This study’s questionnaire incorporated ideas from various studies focusing on the components of the Theory of Planned Behavior. The Theory of Planned Behavior remains valuable for social and behavioral research, as shown in various studies. These studies demonstrate that the theory is still evolving and being explored, with researchers investigating factors such as perceived behavioral control and other factors that affect human behavior [37]. The questionnaire was divided into three parts: the first part was the introduction, where the researcher gave insights to the respondents about the study; the second part was the demographics of the respondents; and, lastly, the questionnaire itself, where the ten latent variables were included namely: (1) Environmental Knowledge, (2) Environmental Concern, (3) Role of Government, (4) Policy and Regulation, (5) Personal Values, (6) Social Norms, (7) Environmental Attitudes, (8) Convenience, (9) Intention, (10) Waste Management Behavior. With a Likert Scale of 1–5, 5 is the highest remarks and 1 is the lowest remarks. The set of questions was used to assess and evaluate the perceptions of the selected San Jose, Occidental Mindoro, residents regarding proper waste disposal in the community (Table 2).

Table 2.

The construct and measurement items.

3.3. Statistical Analysis: Structural Equation Modeling

In San Jose, Occidental Mindoro, the researchers used the Structural Equation Modeling (SEM) approach to investigate various factors influencing how locals perceive effective garbage disposal. A related study claims that policy instruments have substantial direct and indirect effects on families’ intentions to segregate. The empirical analysis supports this claim using a Structural Equation Modeling (SEM) methodology [74]. When the government implements targeted policies to encourage waste separation, it can boost people’s motivation to participate. This is due to both an inherent desire to do the right thing as well as external pressures to meet expectations. This intervention can ultimately increase individuals’ internal drive to recycle and reduce waste.

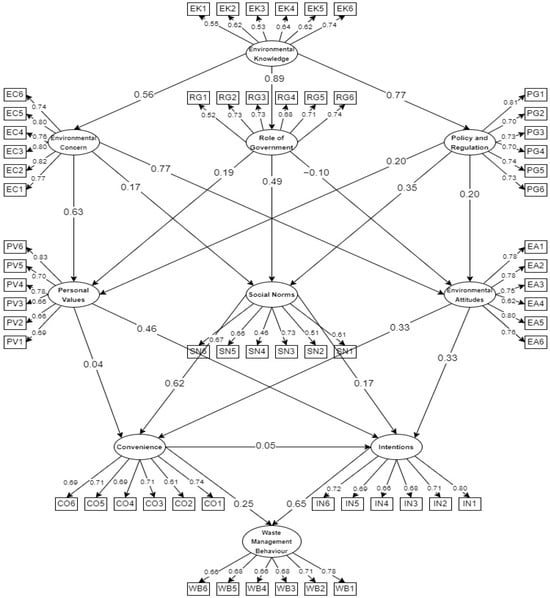

Data are collected from San Jose, Occidental Mindoro, to create a data set for analysis. The data were analyzed using IBM SPSS AMOS software version 22 to ensure its quality and reliability. Hypothesis testing is conducted to identify significant associations between variables, and the SEM model is assessed for its goodness of fit. It helps identify factors influencing proper trash disposal practices and offers insights on sustainable waste management methods, leading to policy recommendations for San Jose, Occidental Mindoro (Figure 2).

Figure 2.

Initial SEM results.

In evaluating models, there are several fit indices to consider. The most commonly used ones include CMIN/DF, Comparative Fit Index (CFI), AGFI, GFI, and Root Mean Square Error (RMSEA). Table 3 was created listing the Good Fit Values and Acceptable Fit Values of these fit indices. AGFI and GFI are based on residuals, and their values increase with larger sample sizes. AGFI ranges from 0 to 1, with values greater than 0.80 indicating a good fit. Similarly, GFI ranges from 0 to 1, with values above 0.80 considered acceptable. For RMSEA, a value of 0.08 or less suggests a good fit while a value between 0.05 and 0.08 indicates an adequate fit.

Table 3.

Model fit values.

4. Results and Discussion

The current study examines the variables affecting proper waste disposal in San Jose, Occidental Mindoro. It evaluates the factors affecting San Jose, Occidental Mindoro’s waste disposal optimization, guiding local government in developing effective strategies and community participation. In this study, SEM was utilized by the researchers to analyze the correlation between Environmental Knowledge (EK), Environmental Concern (EC), Environmental Attitudes (EA), Personal Values (PV), Convenience (CO), Intentions (IN), Waste Management Behavior (WMB), Role of Government (RG), Policy and Regulation (PG), and Social Norms (SN). A total of 300 data samples were acquired through an online questionnaire (Table 4).

Table 4.

Summary and results.

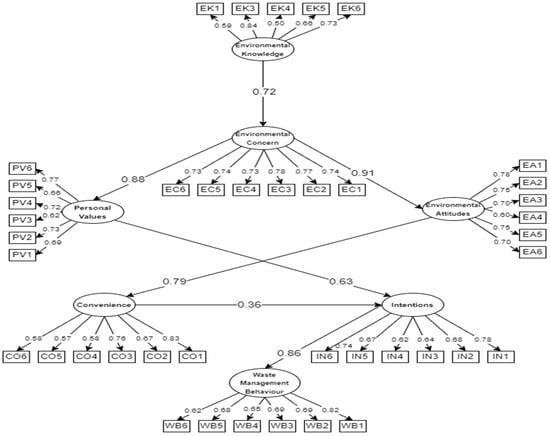

According to the results of Structural Equation Modeling (SEM), shown in Figure 3, Environmental Knowledge (EK) has a significant and positive effect on EC (β: 0.724, p = 0.014). The study conducted by [82] examines how disclosing environmental knowledge can impact public concern for the environment. It operates through two channels: risk perception and understanding environmental pollution. Investigating these mechanisms can help us understand how public environmental concerns and risk perception are affected, and the findings have policy implications for combating pollution. Additionally, SEM also reveals that Environmental Concern directly affects Personal Values (PV) (β: 0.877, p = 0.011). Personal values and personality traits can help explain environmental concerns to minimize waste disposal and create a healthy environment. Understanding how trash affects the environment and people can improve everyone’s position in an economy or an environment that promotes environmental considerations in garbage disposal [15].

Figure 3.

Final SEM result.

The results also show the direct effect of Environmental Concern (EC) on Environmental Attitudes (EA) (β: 0.913, p = 0.009). In addition to helping with global issues, such as the waste disposal problem, understanding environmental attitudes is essential for addressing many applied environmental concerns. Measuring environmental attitudes effectively can support community protection and the development of a sustainable community for all residents.

This study found that there is a significant correlation between Personal Values (PV) and Intentions (IN) (β: 0.630, p = 0.015). Personal values significantly affect people’s willingness to manage community solid waste. Intention is crucial in adopting solid waste management practices and encourages municipal door-to-door collection services, thus improving service utilization. The Structural Equation Model (SEM) also revealed that Environmental Attitudes (EA) have a direct impact on Convenience (CO) (β: 0.787, p = 0.006). To encourage proper waste disposal and sorting in households, engagement elements should be designed to address convenience-related factors that affect waste-sorting engagement. Previous studies have not identified specific factors that can motivate households to engage in better waste-sorting practices [83].

Regarding Convenience (CO), they have had a positive effect on Intentions (IN) (β: 0.358, p = 0.004). To improve household waste separation, it is essential to establish a set of characteristics for waste separation before addressing the convenience of community waste management. Addressing households’ lack of waste separation intentions is necessary to increase convenience in municipal solid waste management systems. Additionally, the SEM analysis revealed that Intentions (IN) were significantly related to Waste Management Behavior (WMB) (β: 0.857, p = 0.014). Households’ intention to separate solid waste was positively linked to improved waste management practices, leading to better municipal solid waste treatment. Attitude and perceived benefits significantly impact citizens’ intentions to separate household solid waste. Enabling conditions also influence household waste separation intentions and behaviors [84].

The interpretation of the hypothesis revealed that the rule of government connecting personal values (0.658) and environmental attitudes (0.771) is not directly significant because the correlation p-values are greater than 0.05. The lack of progress in policy and program sets raises concerns, and various factors, like harmful techniques and government roles, contribute to the complexity [85]. Also, the role of government is not significantly related to social norms (0.328) since the p-values are greater than 0.05. It is not the role of the government, but social norms that can affect people’s intention to dispose of waste in public open spaces. Our communities, friends, and family all impact how we manage our waste [86]. The results also show that the policy and regulations connecting personal values (0.448), social norms (0.190), and environmental attitudes (0.381) are not significantly related since the correlation p-values are greater than 0.05. Assessing household solid waste management requires considering factors such as family size, income, education, location, recycling habits, and municipal waste management, which are influenced by socioeconomic status and housing characteristics. However, policies and regulations related to environmental attitudes, social norms, and personal values do not directly impact these factors [87]. The environmental concerns about social norms (0.139) and environmental attitudes to intentions (0.062) are not significantly related because the p-value correlation is greater than 0.05. Research shows that a person’s behavior toward waste management is affected by logical and charitable attitudes and beliefs, such as personal norms and environmental concerns. Personal norms seek to preserve the natural world and indirectly influence waste management through environmental concern, perceived behavioral control, and environmental knowledge. As a result, personal norms greatly influence pro-environmental behavior [9].

Table 5 presents the capabilities or the significance of the latent variables to one another. Among the ten latent variables, most of the variables showed significance to one another with factor loading not ranging lower than 0.5, namely Environmental Concern (EC), Personal Values (PV), Environmental Attitudes (EA), Convenience (C), Intentions (I), Waste Management Behavior (WMB), and, when it comes to Environmental Knowledge (EK), among the six items, one was cut off due to its insignificance with a final factor loading of below 0.5, and also the variable Role of the Government (RG), Policy and Regulations (PG), and Social Norms (SN) were cut off. Therefore, it ascertains that these three variables do not influence the waste management system in San Jose, Occidental Mindoro. A factor loading of more than 0.5 shows excellent correlation among variables, and using this statistical tool, it is assessed whether given measures are relevant to the study [88].

Table 5.

Descriptive statistics.

Table 6 shows the reliability of the scales, i.e., Cronbach’s alpha, ranging from 0.779 to 0.909, of which ranges are in acceptable line according to the study in [89]. A high Cronbach’s alpha value (usually above 0.7) indicates that survey questions are reliable and measure the same construct. In contrast, a low score indicates that the questions are not consistent and may measure different constructs. In waste disposal research, a high Cronbach’s alpha value indicates effective measurement of knowledge, attitudes, and behaviors toward waste management practices, providing insights into factors influencing waste disposal and informing policy development.

Table 6.

Construct validity model.

Table 7 shows that the seven parameters, namely Minimum Discrepancy (CMIN/DF), Comparative Fit Index (CFI), Incremental Fit Index (IFI), Goodness-of-Fit Index (GFI), Adjusted Goodness-of-Fit index (AGFI), Tucker Lewis Index (TLI), and Root Mean Square Error (RMSE) are all in fit according to Table 3.

Table 7.

Model fit.

The model fit is critical and can be gauged using parameters such as CMIN/DF, CFI, IFI, GFI, AGFI, TLI, and RMSE. A good fit ensures the model is not overfitting or underfitting and leads to accurate results. CMIN/DF measures the difference between the observed and predicted data, while CFI and IFI compare the model to the baseline and null models. GFI and AGFI measure how well the model fits the data, with AGFI accounting for the number of parameters. TLI is similar to CFI, but with a penalty for the number of parameters, and RMSE measures the difference between predicted and actual values. A good fit indicates a reliable model that can make accurate predictions and serve as a strong base for creating an effective waste management system.

Table 8 shows the causal relationship of one variable to another. It indicates here whether the variables have a direct or indirect effect. Direct effects occur when a variable impacts the outcome variable while keeping others constant. Indirect effects happen when the variable influences the outcome variable through one or more intermediate variables. Total effects combine direct and indirect effects and provide a comprehensive understanding of the overall relationship between the variables. It indicates that all variables have a significant total effect, with a p-value less than 0.05. It implies that direct effects are statistically significant, and the intermediate correlates with the study.

Table 8.

Direct, indirect, and total effects.

5. Conclusions

Waste disposal sites are essential components of waste management strategies worldwide. Proper management is critical to preserving the environment and communities. As waste volume increases, disposal plan closures must consider socioeconomic factors to minimize negative impacts on nearby communities [90]. This study aimed to assess the perception of the San Jose, Occidental Mindoro community. This study can potentially direct San Jose toward appropriate waste disposal, and it may also direct the authorities to take proactive measures that promote community waste disposal.

Based on the results of the SEM, environmental knowledge directly affects environmental concerns. Also, the findings showed a significant relation between environmental concern, personal values, and environmental attitude. Meanwhile, personal values directly affect intentions and reveal the significant relationship between environmental attitudes and convenience. Regarding convenience, it also has a direct impact on intentions, while intentions have a direct effect on waste management behavior. On the other hand, the interpretation of the hypothesis revealed that the role of government in connecting personal values, social norms, and environmental attitudes have an insignificant relationship to each other. Also, the policies and regulations connecting to personal values, social norms, and environmental attitudes showed an insignificant relationship. Additionally, it reveals the indirect effect of environmental concern connecting to social norms and environmental attitudes to intentions. The researcher tends to examine the relation between the variable Role of Government and policy and regulation, even if they are insignificant to one another.

Even though the government should play a significant role in influencing the community’s perception of garbage disposal, the result showed that the government and its policies and regulations do not affect the community’s perception and behavior about proper waste disposal and segregation. Therefore, the Local Government Unit (LGU) of San Jose is recommended to have a municipal ordinance and reward programs for community initiation in compliance with national environmental regulations. The Ecological Solid Waste Management Act of 2000 (Republic Act 9003) [91], which mandates the nation for adequate and proper waste segregation, disposal, and recycling, strongly supports the national research and development programs initiated by the local community and government. Reward programs such as recycling programs and garbage exchange for prizes in Bacolod City, Philippines, are also good initiatives for the local community to begin segregating their waste correctly [92].

Drawing on the findings of this study, it is highlighted that the age group of 18–29 years old was the majority of the respondents, making them a good target for the Local Government of San Jose to promote waste management. This study suggests that the Local Government of San Jose could focus their waste management campaigns on younger adults, who are more likely to engage with and adopt sustainable behaviors. It could include targeted social media campaigns, community events, and educational programs to raise awareness about proper waste disposal methods. By targeting this age group, the government can encourage a culture of sustainability and environmental responsibility, resulting in far-reaching positive impacts on the entire community. Additionally, the study emphasizes the need for ongoing research and data collection to improve waste management strategies and ensure their continuous effectiveness.

Consequently, all waste disposal site closure procedures should sufficiently address the environmental, socioeconomic, and political aspects to ensure sustainability, just as important as ecological remediation and conservation are strategies for reducing adverse socioeconomic effects. In particular, any WDS closure activities and progression should include reducing the effects on the livelihoods of the informal stakeholders, as these livelihoods may be sustainably planned for, potentially eliminating the adverse effects. This study provides the community’s perception of waste disposal, gains knowledge of the potential impacts of waste disposal on the livelihoods of local communities, and examines strategies for sustaining livelihoods. This study can potentially guide authorities in San Jose to implement practical actions to promote sustainability for every livelihood in the community.

6. Limitation and Future Works

This study focuses on waste management in San Jose, Occidental Mindoro. Among the 39 barangays, the researchers should have contacted the 5 barangays to gather information. Due to its limitations, the researchers only gathered a total number of 300 participants; regarding Structural Equation Modeling, the more participants the model had, the better it would be structured. With a total number of 300 participants, the result leads to the insignificance of some latent variables. Moreover, the age group can be generalized by obtaining a survey from an equally distributed age group to represent the result better. It could be improved by gathering several participants, more than 300. A more significant number of samples will make the results more reliable and accurate.

The current study signifies the Theory of Planned Behavior as an accurate guideline for studying participants’ perceptions and manners. This study will contribute to future research considering other factors that affect the community’s waste management behavior. Future research could be conducted to gather larger samples and investigate critical drivers in a particular area and group.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, Supervision, Funding Acquisition, and Writing—Review and Editing, Y.-T.J., K.A.M. and C.S.S.; Formal Analysis, Investigation, Methodology, Visualization, and Writing—Original Draft, D.A.B., J.R.C., K.G., J.M., F.S. and K.A.V. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in this study.

Data Availability Statement

Data are contained within the article.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Tsydenova, N.; Morillas, A.V.; Salas, A.C. Sustainability assessment of Waste Management System for Mexico City (mexico)—Based on analytic hierarchy process. Recycling 2018, 3, 45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baawain, M.; Al-Mamun, A.; Omidvarborna, H.; Al-Amri, W. Ultimate composition analysis of municipal solid waste in Muscat. J. Clean. Prod. 2017, 148, 355–362. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hoang, N.H.; Fogarassy, C. Sustainability Evaluation of Municipal Solid Waste Management System for Hanoi (vietnam)—Why to choose the ‘waste-to-energy’ concept. Sustainability 2020, 12, 1085. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- David, V.E.; Cha, J.Y.; Hussain, S. Rethinking sustainability: A review of Liberia’s municipal solid waste management systems, status, and challenges. J. Mater. Cycles Waste Manag. 2020, 22, 1299–1317. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Global Waste Index. Sensoneo. Available online: https://sensoneo.com/global-waste-index/ (accessed on 25 July 2023).

- Coracero, E.E.; Gallego, R.J.; Frago, K.J.M.; Gonzales, R.J.R. A Long-Standing problem: A review on the solid waste management in the Philippines. Indones. J. Soc. Environ. Issues 2021, 2, 213–220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Municipal Planning Development Office. Comprehensive Land and Water Use Plan, Socio Economic and Physical Profile (SEPP) Volume One. 2017. Available online: https://m.facebook.com/MPDOSanJoseOccMindoro/photos/the-sectoral-and-special-area-studiesthe-municipality-of-san-jose-occidental-min/2057851954433737/?_se_imp=1NgZiQhqozYxTU820#_=_ (accessed on 18 December 2023).

- Khan, S.; Anjum, R.; Raza, S.T.; Bazai, N.A.; Ihtisham, M. Technologies for Municipal Solid Waste Management: Current Status, Challenges, and Future Perspectives. Chemosphere 2022, 288, 132403. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wu, L.; Zhu, Y.; Zhai, J. Understanding Waste Management Behavior among university students in China: Environmental knowledge, personal norms, and the theory of planned behavior. Front. Psychol. 2022, 12, 771723. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, N.; Liu, Y.; Yu, X. The impact of Public Environmental Concern on environmental pollution: The moderating effect of Government Environmental Regulation. PLoS ONE 2023, 18, e0290255. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Larson, L.R.; Stedman, R.C.; Cooper, C.B.; Decker, D.J. Understanding the multi-dimensional structure of pro-environmental behavior. J. Environ. Psychol. 2015, 43, 112–124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Enger, E.D.; Smith, B.F. Environmental Science: A Study of Interrelationships, 14th ed.; McGraw-Hill Education and Tsinghua University Press Limited: New York, NY, USA, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, H.; Zhu, G.; Li, Y. Research on the impact of environmental risk perception and public participation on evaluation of Local Government Environmental Regulation Implementation Behavior. Environ. Chall. 2021, 5, 100213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Silva, E. The politics of policy implementation and reform: Chile’s environmental impact assessment system. Extr. Ind. Soc. 2023, 15, 101321. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Degnet, M.B.; Hansson, H.; Hoogstra-Klein, M.A.; Roos, A. The Role of Personal Values and Personality Traits in Environmental Concern of Non-industrial Private Forest Owners in Sweden. For. Policy Econ. 2022, 141, 102767. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saracevic, S.; Schlegelmilch, B.B. The impact of social norms on pro-environmental behavior: A systematic literature review of the role of culture and self-construal. Sustainability 2021, 13, 5156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reaños, M.A.T.; Meier, D.E.; Curtis, J.; Pillai, A. The Role of Energy, Financial Attitudes and Environmental Concerns on Perceived Retrofitting Benefits and Barriers: Evidence from Irish Home Owners. Energy Build. 2023, 297, 113448. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Belanche, D.; Casaló, L.V.; Flavián, C. Integrating trust and personal values into the Technology Acceptance Model: The case of e-government services adoption. Cuad. Econ. Dir. Empresa 2012, 15, 192–204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kinzig, A.P.; Ehrlich, P.R.; Alston, L.J.; Arrow, K.; Barrett, S.; Buchman, T.G.; Daily, G.C.; Levin, B.; Levin, S.; Oppenheimer, M.; et al. Social norms and global environmental challenges: The complex interaction of behaviors, values, and policy. BioScience 2013, 63, 164–175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Harring, N.; Jagers, S.C.; Nilsson, F. Recycling as a large-scale collective action dilemma: A cross-country study on trust and reported recycling behavior. Resour. Conserv. Recycl. 2019, 140, 85–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kulin, J.; Sevä, I.J. Quality of government and the relationship between environmental concern and pro-environmental behavior: A cross-national study. Environ. Politics 2020, 30, 727–752. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Poortinga, W.; Pidgeon, N.F. Exploring the dimensionality of trust in risk regulation. Risk Anal. 2003, 23, 961–972. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Z.; Guo, D.; Wang, X. Determinants of residents’ e-waste recycling behaviour intentions: Evidence from China. J. Clean. Prod. 2016, 137, 850–860. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Geng, M.-M.; He, L.-Y. Environmental regulation, environmental awareness and environmental governance satisfaction. Sustainability 2021, 13, 3960. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gangwar, B.; Kaur, B. Exploring the Role of Lifestyle and Personality in Predicting the Green Buying Intentions of Responsible Consumers: Sustainability Insights From an Emerging Economy. In Sustainable Marketing, Branding, and Reputation Management: Strategies for a Greener Future; IGI Global: Firozpur, India, 2023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sorkun, M.F. How do social norms influence recycling behavior in a collectivistic society? A case study from Turkey. Waste Manag. 2018, 80, 359–370. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ham, M.; Jeger, M.; Ivković, A.F. The role of subjective norms in forming the intention to purchase Green Food. Econ. Res.-Ekon. Istraz. 2015, 28, 738–748. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Milfont, T.L.; Duckitt, J. The Environmental Attitudes Inventory: A Valid and Reliable Measure to Assess the Structure of Environmental Attitudes. J. Environ. Psychol. 2010, 30, 80–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wahyudin, M.; Yuliando, H.; Savitri, A. Consumer Behavior Intentions to Purchase Daily Needs through Online Store Channel. Agritech 2021, 40, 306–311. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yeo, V.; Goh, S.K.; Rezaei, S. Consumer Experiences, Attitude and Behavioral Intention toward Online Food Delivery (OFD) Services. J. Retail. Consum. Serv. 2017, 35, 150–162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Juma-Michilena, I.-J.; Ruiz-Molina, M.E.; Gil-Saura, I.; Belda-Miquel, S. An analysis of the factors influencing pro-environmental behavioural intentions on climate change in the University Community. Econ. Res.-Ekon. Istraz. 2023, 36, 2264373. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Henry, R.K.; Yongsheng, Z.; Jun, D. Municipal Solid Waste Management Challenges in Developing Countries—Kenyan Case Study. Waste Manag. 2006, 26, 92–100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Khan, O.; Daddi, T.; Slabbinck, H.; Kleinhans, K.; Vazquez-Brust, D.; De Meester, S. Assessing the Determinants of Intentions and Behaviors of Organizations Towards a Circular Economy for Plastics. Resour. Conserv. Recycl. 2020, 163, 105069. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, X.; Long, R.; Yang, J. Interactive Effects of Two-way Information and Perceived Convenience on Waste Separation Behavior: Evidence from Residents in Eastern China. J. Clean. Prod. 2022, 374, 134032. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aboelmaged, M. E-waste Recycling Behaviour: An Integration of Recycling Habits into the Theory of Planned Behaviour. J. Clean. Prod. 2020, 278, 124182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Memon, M.A.; Ting, H.; Cheah, J.-H.; Thurasamy, R.; Chuah, F.; Cham, T.H. Sample Size For Survey Research: Review and recommendations. J. Appl. Struct. Equ. Model. 2020, 4, 1–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bosnjak, M.; Ajzen, I.; Schmidt, P. The theory of planned behavior: Selected recent advances and applications. Eur. J. Psychol. 2020, 16, 352–356. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nguyen, T.T.; Malek, L.; Umberger, W.J.; O’Connor, P.J. Household food waste disposal behaviour is driven by perceived personal benefits, recycling habits and ability to compost. J. Clean. Prod. 2022, 379, 134636. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kharaba, Z.; Khasawneh, L.; Aloum, L.; Ghemrawi, R.; Jirjees, F.; Bataineh, N.A.; Al-Azayzih, A.; Buabeid, M.; Al-Abdin, S.Z.; Alfoteih, Y. An Assessment of the Current Practice of Community Pharmacists for the Disposal of Medication Waste in the United Arab Emirates: A Deep Analysis at a Glance. J. Saudi Pharm. Soc. 2022, 30, 1773–1780. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Insani, W.N.; Qonita, N.A.; Jannah, S.S.; Nuraliyah, N.M.; Supadmi, W.; Gatera, V.A.; Alfian, S.D.; Abdulah, R. Improper disposal practice of unused and expired pharmaceutical products in Indonesian households. Heliyon 2020, 6, e04551. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Komal. Archimedeanconorm based intuitionistic fuzzy WASPAS method to evaluate health-care waste disposal alternatives with unknown weight information. Appl. Soft Comput. 2023, 146, 110751. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Uba, U.J.; Efut, E.N.; Obeten, U.B.; Asuquo, E.E.; Uba, J.C. Sociodemographic factors and environmental workers’ knowledge of the impact of awareness creation on sustainable disposal of solid wastes. Heliyon 2023, 9, e18122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mensah, D.; Ng, K.T.; Hasan, M.M.; Jeenat, R.E.; Hurlbert, M. Assessing non-hazardous solid waste business characteristics of Western Canadian provinces. Ecol. Inform. 2023, 75, 102030. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mor, S.; Ravindra, K. Municipal solid waste landfills in lower- and middle-income countries: Environmental impacts, challenges and sustainable management practices. Process Saf. Environ. Prot. 2023, 174, 510–530. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ara, L.; Billah, W.; Bashar, F.; Mahmud, S.; Amin, A.; Iqbal, R.; Rahman, T.; Alam, N.H.; Sarker, S.A. Effectiveness of a multi-modal capacity-building initiative for upgrading biomedical waste management practices at healthcare facilities in Bangladesh: A 21st Century challenge for developing countries. J. Hosp. Infect. 2022, 121, 49–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, P.; Zhou, J.; Fan, Y.V.; Klemeš, J.J.; Zheng, M.; Varbanov, P.S. Data Analysis of resident engagement and sentiments in social media enables better household waste segregation and recycling. J. Clean. Prod. 2021, 319, 128809. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kamaruddin, S.M.; Pawson, E.; Kingham, S. Facilitating social learning in Sustainable Waste Management: Case Study of ngos involvement in Selangor, Malaysia. Procedia—Soc. Behav. Sci. 2013, 105, 325–332. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deliberador, L.R.; Santos, A.B.; Carrijo, P.R.S.; Batalha, M.O.; César, A.d.S.; Ferreira, L.M.D. How risk perception regarding the COVID-19 pandemic affected household food waste: Evidence from Brazil. Socio-Econ. Plan. Sci. 2023, 87, 101511. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jerin, D.T.; Sara, H.H.; Radia, M.A.; Hema, P.S.; Hasan, S.; Urme, S.A.; Audia, C.; Hasan Md, T.; Quayyum, Z. An overview of progress towards implementation of solid waste management policies in Dhaka, Bangladesh. Heliyon 2022, 8, e08918. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Makwara, E.C.; Snodia, S. Confronting the reckless gambling with people’s health and lives: Urban solid waste management in zimbabwe. Eur. J. Sustain. Dev. 2013, 2, 67–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Outka, U. Fairness in the Low-Carbon Shift: Learning from Environmental Justice. HeinOnline. 2016. Available online: https://heinonline.org/hol-cgi-bin/get_pdf.cgi?handle=hein.journals/brklr82§ion=27 (accessed on 4 September 2023).

- Segerson, K.; Tietenberg, T. The Structure of Penalties in Environmental Enforcement: An Economic analysis. In Economics and Liability for Environmental; Routledge: London, UK, 2018; pp. 333–354. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gallo, F.; Fossi, C.; Weber, R.; Santillo, D.; Sousa, J.; Ingram, I.; Nadal, A.; Romano, D. Marine litter plastics and microplastics and their toxic chemicals components. In Analysis of Nanoplastics and Microplastics in Food; CRC Press: Boca Raton, FL, USA, 2020; pp. 159–179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ndum, A.E. Bottom-Up Approach to Sustainable Solid Waste Management in African Countries. 2013. Available online: https://opus4.kobv.de/opus4-btu/frontdoor/index/index/docId/2753 (accessed on 4 September 2023).

- Zaman, A. A comprehensive review of the development of zero waste management: Lessons learned and guidelines. J. Clean. Prod. 2015, 91, 12–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, D.; Cai, X.; Nketiah, E.; Adjei, M.; Adu-Gyamfi, G.; Obuobi, B. Separate your waste: A comprehensive conceptual framework investigating residents’ intention to adopt household waste separation. Sustain. Prod. Consum. 2023, 39, 216–229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, X.; Li, X.; Bian, J.; Yang, C. Deposit or reward: Express packaging recycling for online retailing platforms. Omega 2023, 117, 102828. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salem, M.; Raab, K.; Wagner, R. Solid waste management: The disposal behavior of poor people living in Gaza Strip refugee camps. Resour. Conserv. Recycl. 2020, 153, 104550. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pei, Z. Roles of neighborhood ties, community attachment and local identity in residents’ household waste recycling intention. J. Clean. Prod. 2019, 241, 118217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Almulhim, A.I. Household’s awareness and participation in sustainable electronic waste management practices in Saudi Arabia. Ain Shams Eng. J. 2022, 13, 101729. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ke, J.; Cai, K.; Yuan, W.; Li, J.; Song, Q. Promoting solid waste management and disposal through contingent valuation method: A review. J. Clean. Prod. 2022, 379, 134696. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fagerholm, A.-S.; Haller, H.; Warell, A.; Hedvall, P.-O. What a waste—A norm-critical design study on how waste is understood and managed. Resour. Conserv. Recycl. Adv. 2023, 19, 200178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Katan, L.; Gram-Hanssen, K. ‘Surely I would have preferred to clear it away in the right manner’: When social norms interfere with the practice of waste sorting: A case study. Clean. Responsible Consum. 2021, 3, 100036. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Knebel, M. Cross-country comparative analysis and case study of institutions for future generations. Futures 2023, 151, 103181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Diprose, K.; Liu, C.; Valentine, G.; Vanderbeck, R.M.; McQuaid, K. Caring for the future: Climate change and intergenerational responsibility in China and the UK. Geoforum 2019, 105, 158–167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chi, N.T.K. Ethical consumption behavior towards eco-friendly plastic products: Implication for cleaner production. Clean. Responsible Consum. 2022, 5, 100055. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rottman, J.; Lerner, M. The burden of climate action: How environmental responsibility is impacted by socioeconomic status. J. Environ. Psychol. 2021, 77, 101674. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, J.; Yu, X.; Wang, J.; Sui, Q.; Zhao, W. Impacts of Garbage Classification and Disposal on the Occurrence of Pharmaceutical and Personal Care Products in Municipal Solid Waste Leachates: A Case Study in Shanghai. Sci. Total Environ. 2023, 874, 162467. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goyal, V.; Dharwal, M. The Puzzle of Garbage Disposal in India. Mater. Today Proc. 2022, 60, 926–929. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jia, Q.; Islam, M.S.; Hossain, M.S.; Li, F.; Wang, Y. Understanding Residents’ Behaviour Intention of Recycling Plastic Waste in a Densely Populated Megacity of Emerging Economy. Heliyon 2023, 9, e18921. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Malek, W.; Mortazavi, R.; Cialani, C.; Nordström, J. How Have Waste Management Policies Impacted the Flow of Municipal Waste? An Empirical Analysis of 14 European Countries. Waste Manag. 2023, 164, 84–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Habib, M.D.; Kaur, P.; Sharma, V.; Talwar, S. Analyzing the Food Waste Reduction Intentions of UK Households. A Value-Attitude-Behavior (VAB) Theory Perspective. J. Retail. Consum. Serv. 2023, 75, 103486. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, J.; Long, R.; Chen, H.; Cheng, X. Willingness to Participate in Take-out Packaging Waste Recycling: Relationship Among Effort Level, Advertising Effect, Subsidy and Penalty. Waste Manag. 2021, 121, 141–152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Akmal, E.; Panjaitan, H.P.; Ginting, Y.M. Service quality, product quality, Price, promotion, and location on customer satisfaction and loyalty in CV. Restu. J. Appl. Bus. Technol. 2023, 4, 39–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Norberg, M.; Stenlund, H.; Lindahl, B.; Anderson, C.; Weinehall, L.; Hallmans, G.; Eriksson, J.W. Components of metabolic syndrome pre-dicting diabetes: No role of inflammation or dyslipi-demia. Obesity 2007, 15, 1875–1885. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, H.; Arditi, D.; Wang, Z. Factors that affect transaction costs in construction projects. J. Constr. Eng. Manag. 2013, 139, 60–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Algi, S.; Abdul Rahman, M.A. The relationship between personal mastery and teachers’ competencies at schools in Indonesia. J. Educ. Learn. 2014, 8, 217–226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Chen, Y.Q.; Zhang, Y.B.; Liu, J.Y.; Mo, P. Interrelationship among critical success factors of construction projects based on the structural equation model. J. Manag. Eng. 2012, 28, 243–251. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Doloi, H.; Sawhney, A.; Iyer, K.C. Structural equation model for investigating factors affecting delay in Indian construction projects. Constr. Manag. Econ. 2012, 30, 869–884. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jafari, F.; Azadi, H.; Abdi, A.; Salari, N.; Faraji, A. Cultural Validation of the Competence in Evidence-Based Practice Questionnaire (EBP-COQ) for Nursing Students. J. Edu. Health Promot. 2021, 10, 464. Available online: https://www.jehp.net/text.asp?2021/10/1/464/333921 (accessed on 18 December 2023).

- Lee, S.; Park, E.; Kwon, S.; del Pobil, A. Antecedents of behavioral intention to use mobile telecommunication services: Effects of Corporate Social Responsibility and Technology Acceptance. Sustainability 2015, 7, 11345–11359. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pan, D.; Fan, W.; Kong, F. Dose Environmental Information Disclosure Raise Public Environmental Concern? Generalized Propensity Score Evidence From China. J. Clean. Prod. 2022, 379, 134640. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Negash, Y.T.; Sarmiento, L.S.C.; Tseng, M.-L.; Lim, M.K.; Ali, M.H. Engagement Factors for Household Waste Sorting in Ecuador: Improving Perceived Convenience and Environmental Attitudes Enhances Waste Sorting Capacity. Resour. Conserv. Recycling 2021, 175, 105893. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Wang, G.; Zhang, Q.; Ji, Y.; Xu, H. What determines urban household intention and behavior of solid waste separation? A case study in China. Environ. Impact Assess. Rev. 2022, 93, 106728. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salvia, G.; Zimmermann, N.; Willan, C.; Hale, J.R.; Gitau, H.; Muindi, K.; Gichana, E.; Davies, M. The Wicked Problem of Waste Management: An Attention-based Analysis of Stakeholder Behaviours. J. Clean. Prod. 2021, 326, 129200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tinio, E. Solid Waste and Social Norms: How Your Friends Affect How You Throw Your Trash. EnP Tinio. 2021. Available online: https://www.google.com/amp/s/enptinio.com/social-norms-waste-management/amp/ (accessed on 18 December 2023).

- Fadhullah, W.; Imran, N.I.N.; Ismail, S.N.S.; Jaafar, M.H.; Abdullah, H. Household Solid Waste Management Practices and Perceptions among Residents in the East Coast of Malaysia. BMC Public Health 2022, 22, 1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tavakol, M.; Wetzel, A. Factor analysis: A means for theory and instrument development in support of construct validity. Int. J. Med. Educ. 2020, 11, 245–247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Biggs, J.; Kember, D.; Leung, D.Y.P. The Revised Two-Factor Study Process Questionnaire: R-SPQ-2F. Br. J. Educ. Psychol. 2001, 71, 133–149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Aryampa, S.; Maheshwari, B.; Sabiiti, E.; Bateganya, N.L.; Olobo, C. Understanding the Impacts of Waste Disposal Site Closure on the Livelihood of Local Communities in Africa: A Case Study of the Kiteezi Landfill in Kampala, Uganda. World Dev. Perspect. 2022, 25, 100391. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Food and Agriculture Organization. Ecological Solid Waste Management Act No. 9003 of 2000. FAO.org. Available online: https://www.fao.org/faolex/results/details/en/c/LEX-FAOC045260/ (accessed on 18 December 2023).

- Ramonmitcs. GARBAGE = REWARDS—Bacolod City Government. Bacolod City Government—City of Smiles. Available online: https://bacolodcity.gov.ph/garbage-rewards/ (accessed on 7 February 2023).

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).