1. Introduction

Natural protected areas or conservation units, as in Brazil, fulfill several environmental, social, political, and economic objectives. Among the most important are the protection of biodiversity and its habitat, guaranteeing the availability of environmental services, protecting the country’s heritage, and promoting good environmental practices and research, among others [

1]. Therefore, objectives that are directed towards the conservation of ecosystems guarantee the provision of environmental goods and services that are essential for society, since economic growth and sustainable development depend on them [

2]. Conservation units or protected areas not only have different objectives, they also have different management models, in which some models of conservation units do not allow human presence inside them; however, there are few examples of wildlife that are free from human influence, which makes it necessary to consider the existence of populations in protected areas, which can significantly help in the formation and maintenance of protected ecosystems if carried out in the right way [

3].

Thus, to learn more about the management of protected areas, this study should focus on the region with the highest proportion of protected areas in the world, which is Latin America, distributed with 28.2% of the areas in Central America and 25% in South America; Latin America is also the richest region in biodiversity with 42% of mammals, 43% of reptiles, and 47% of amphibians in the world; it also contains 22% of the planet’s fresh water and 16% of marine water resources. In addition, due to latitudinal and altitudinal variation, it has a great variety of ecosystems ranging from the most arid desert to the most humid jungle in the world [

4]. But, on the other hand, in Latin America, life strategies were highly influenced by agriculture, finding human settlements even in protected areas, which happens despite the ecological importance promoted in 1992 by the Convention on Biodiversity, by which the system of protected areas was established, a term used in Latin America in 1960, with the exception of Brazil, which is known as the system of conservation units [

5].

Most protected areas have human settlements, which implies the presence of activities such as agriculture, characterized as an activity with the highest consumption of fresh water and which occupies large areas of land, leading to deforestation, which makes it an activity that promotes changes in biodiversity and ecosystem services; it is also the emitter of 34% of greenhouse gas emissions [

6]; in fact, the highest deforestation rates occur in the buffer zones around protected areas, and the most important driver of deforestation is agriculture, which is why deforestation around protected areas can hinder conservation strategies [

7].

Therefore, the Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations (FAO) mentions that the solution to this problem is green agrifood systems, which reduce emissions and seek the path of conservation, as opposed to conventional agriculture, which does not maintain a sustainable and harmonious relationship with natural resources; in addition, organic-based agriculture is characterized by not using chemicals in production, and on the contrary, focusing on soil fertility, crop rotation, nutrient cycling, and ecosystem dynamics [

8]. Likewise, FAO supports the transformation of agrifood systems, especially when some crops are in protected areas or conservation units, while recognizing and protecting the rights of Indigenous peoples, families, and farmers to achieve a better environment [

9].

So, the main objective of the conservation units or protected areas is conservation, but, according to the objectives of the area, sustainable use is allowed with the inclusion of certain anthropogenic activities such as agriculture, being the main economic activity in most of the areas for residents of said areas. Therefore, it is important to analyze the agriculture-protected area relationship, since depending on the type of agriculture (conventional or agroecological), type of crop, and other variables, it is the type of impact that is generated that can affect the fulfillment of the objectives and conservation [

10]. Furthermore, analyzing and studying the external or internal factors that influence this relationship are vital to reveal the weaknesses and strengths that are present in agricultural activities within the conservation area, as confirmed by Possamai and Assunção [

11]; within the transition from conventional to agroecological agriculture, there are challenges that depend on the social or political context of the territory where the natural area is located. Also, studying agricultural practices in protected areas provides information to local governments for conservation action plans, and maintains food production for the inhabitants of these areas [

12].

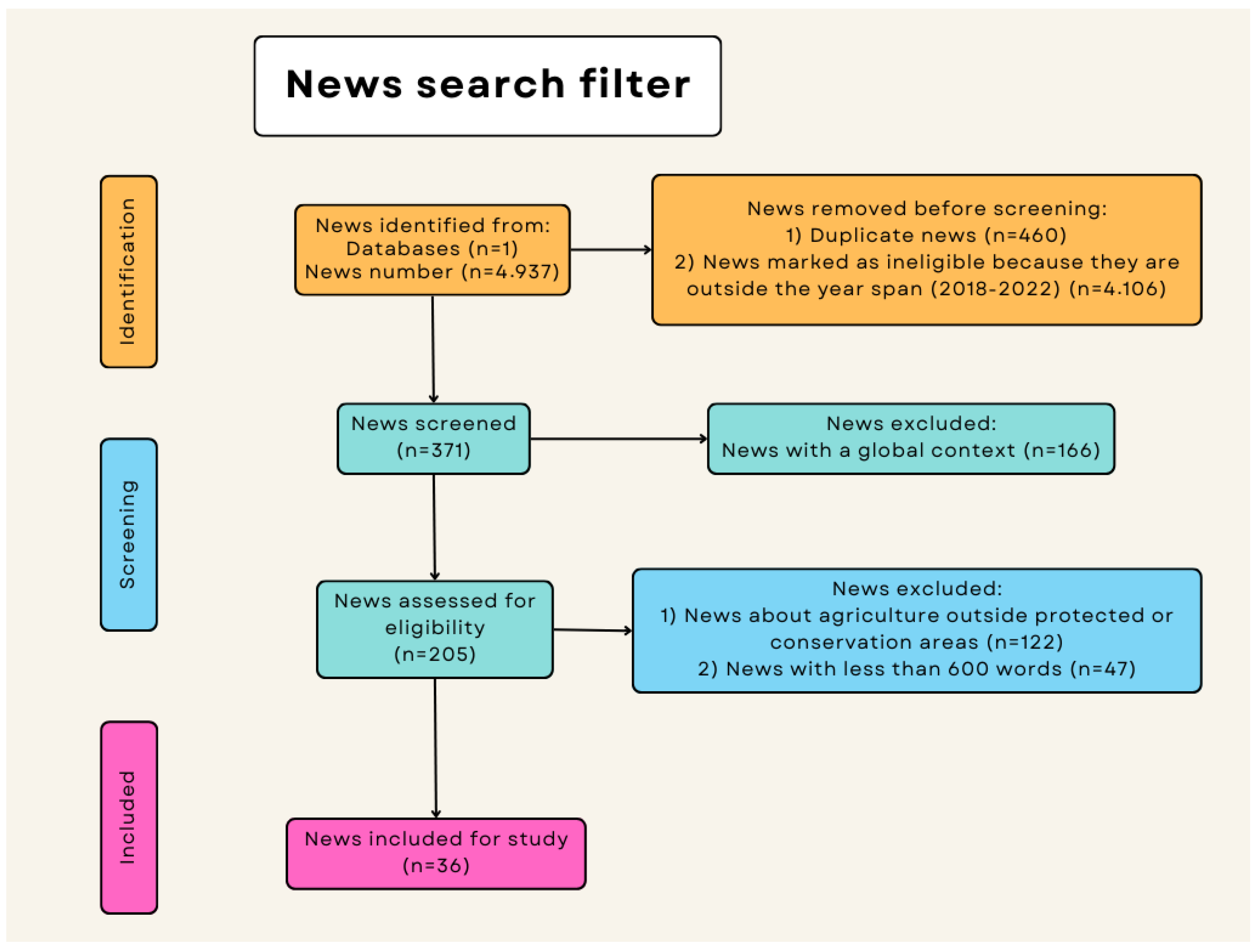

Finally, regarding the knowledge produced about agriculture in protected areas/conservation units, the different media have a strategic role in the dissemination of information about the interaction of agricultural practices in these areas. This leads to our problem question: what is the relationship between agriculture and the different protected areas/conservation units in Latin America considering the context of its territory? To answer this, we use a compilation of the most relevant Latin American news from the last 5 years on agriculture in the different protected areas/conservation units, relying on the opinions of different authors, since the objective of the study is to analyze the relationship between agriculture and the different protected areas/conservation units of Latin America with accurate information. Clarifying that, although the main objective of the media should be to inform the community about important day-to-day events, unfortunately this is often not the case [

13]. Therefore, it is necessary to validate the information provided about agriculture in protected areas/conservation units, to avoid falling into the sensationalism implemented by some media; for this reason, the information from the different media at the level of Latin America (Brazil, Costa Rica, Mexico, Dominican Republic, Colombia, Bolivia, Peru, Cuba, Paraguay, Nicaragua, Argentina, Honduras, Chile, Venezuela) is supported with academic literature, to give greater validity and confidence to the reports provided by journalists.

This paper combines different viewpoints of two media outlets, one with scientific objectives and the other with journalistic objectives, which when combined generate a complete and novel analysis, in which we not only find current information but also reliable information. In addition, we address the relationship between agriculture and protected areas or conservation units, which are key territories for conservation and are a relevant component in the mitigation of environmental impacts worldwide.

3. Results

There are several situations or environmental conflicts cited around each news item, from the establishment of new conservation rules to the description of different negative scenarios for conservation (logging, erosion, contamination, corruption, etc.). In addition, the actors involved in the event, the type of cultivation, the tools used, as well as the aforementioned species encompass the characteristics that generate impact according to the context of each country mentioned in the news, and, as a result, news about 14 Latin American countries was analyzed (

Figure 2).

In different Latin American countries, we find different situations that frame the relationship between protected areas or conservation units and agriculture (

Figure 3).

As seen in

Figure 3, there are common patterns in the different countries analyzed, where the percentage difference between the positive and negative scenarios presented in the analyzed news is 16.6%, since the sum of the percentages of negative scenarios such as illegal drug plantations, unauthorized plantations, and lack of regulations gives 58.3% compared to positive scenarios such as sustainable initiatives by the government or NGOs and crops under good environmental practices that add up to 41.7%; each scenario is detailed below.

Among the negative scenarios, there are the unauthorized plantations that affect ecosystems and go against conservation objectives in protected areas, followed by illegal plantations for which, although not a common denominator for all countries, two patterns of plantations were found, prohibited and illegal, which are presented in the following table (

Table 3):

The results show that, in some Latin American countries, illegal plantations (cocaine, marihuana) are established in protected areas; in general, it happens as a means to hide and reproduce this type of illegal crops within drug trafficking activities, as is the case in Colombia, where natural parks are characterized by conditions of difficult access, a large territorial extension, little presence of the state, and a strategic geographic location for the cultivation, processing, or trafficking of cocaine [

27]. The biggest problem is not the establishment of illicit crops in Colombia’s natural parks, but the deforestation it generates, where it also highlights that the expansion of such crops that has been present since 2013 is worrisome, although by 2019, it presented a reduction of 0.011 ha/km

2/year [

28]. On the contrary, in Peru, coca cultivation in natural protected areas increased between 2011 and 2019, from 47 ha to 218 ha within the protected areas, while in the buffer zones, it increased from 5075 ha to 6806 ha [

29]. Meanwhile, in Bolivia, for example, in the Chapare region, coca cultivation undermines the conservation objectives of its protected areas [

30]. And in the case of marijuana crops, we find Paraguay, a country that has become the main producer of cannabis in South America, and is currently growing cannabis within protected areas. A particular case is the Mbaracayú Forest Nature Reserve in Paraguay, where a group of farmers use the reserve to grow cannabis, being for them a safe and profitable ecosystem to develop their business as it is a large, wooded area, with different entry and exit points, which makes it impossible to control human movement; these factors make it an ideal space for clandestine planting in areas they call “drug moles”, which justice considers impossible to prosecute because it is difficult to locate them. In addition, this practice in the protected area was extended to protect their market from threats and extortion by state and non-state actors in the organized crime market [

31]. Likewise, another case of cannabis crops in protected areas is presented by Costa Rica, whose plantations are concentrated in the South of the Caribbean slope of the country, specifically in the Río Pacuare Forest Reserve, the Banano River Protective Zone, the Hitoy Cerere Biological Reserve, and especially in the La Amistad International Park [

32].

In the case of non-permitted crops, in Mexico, agricultural activities affect the conservation objectives of protected areas, as is the case in the Sierra de Huautla Biosphere Reserve, where corn, beans, and sorghum are grown, and where these crops have a major impact on the biodiversity present in the reserve [

33]; in Costa Rica, fragmented landscapes are observed due to the replacement of forests by crops; a specific case is observed in protected areas such as the Central Talamanca Volcanic Biological Corridor, affecting biodiversity and thus favoring the loss of connectivity between habitats [

34]; in Brazil, transgenic soybean crops are present in conservation units, specifically in the area of the Serra da Bodoquena National Park, where, according to environmental legislation in areas of integral protection, the planting of genetically modified food crops is prohibited, due to the negative impact on the health of the ecosystems [

35]; in Nicaragua, monocultures exert pressure on the Miraflor Moropotente protected area, causing ecosystem fragmentation and therefore changes in ecological processes [

36]; in the Dominican Republic, the management of protected areas is problematic due to the anthropogenic impact of human activities within the boundaries of protected areas with various types of crops that generate pressure on natural resources [

37]; in Honduras, regarding the protected area “Barras Cuero y Salado”, its biodiversity is threatened by the change in land use for the cultivation of African palm [

38]; finally, in Bolivia, protected natural areas are impacted by soybean cultivation and monoculture expansions [

39].

On the other hand, there is a lack of regulation (application of laws or rules) in some protected areas, which makes the conservation process difficult because the legal bases and supports that protect it have not been defined (

Table 4).

According to the description of the cases, the lack of regulation is due to poor management by the countries, the irrelevance of conservation objectives in protected areas, and the loss of balance between production and conservation. As is the case in Bolivia, and the institutional weakness of natural protected areas is one of the main problems, with insufficient management and administration instruments, which generates inapplicability and non-compliance with environmental regulations, in addition to the weakening, opening, and flexibilization of environmental protection zones, thus allowing the extension of soybean monocultures, which causes a significant decrease in soil productivity, depleting them and forcing them to move to other soils [

39]. Likewise, in Manuel Antonio National Park in Costa Rica, there are conflicts due to poor management of the protected area, which led to advances in the wetlands of the northern zone for pineapple cultivation [

44]. Likewise, in the Dominican Republic, the drivers of deforestation in Los Haitises National Park are multifactorial in nature, and most of them are linked to management factors of the protected area, one of them being due to decisions that allow the extension of monocultures [

45].

But, the management and regulation of protected areas must not only exist within their areas, but also around their zones (buffer zones), since any alteration in the buffer zone affects the protected area, influencing the balance and conservation of their ecosystems. To illustrate, there is the case of the “La Campana” protected area in Chile, where the increase in the surface area of avocado and citrus crops around the protected area exposes animals and plants that are on the verge of extinction (classified on the red list of threatened species of the International Union for Conservation of Nature) to greater pressure [

46]. Likewise, in Argentina, the protected areas of the Pampas region are threatened by the insertion of soybean monocultures around them, due to the lack of environmental regulation [

47].

Furthermore, it is worth analyzing that one of the causes of the poor regulation and management of protected areas is due to the bad governments that are exercised in each country. Worboys et al. express that national legislation and policies on protected areas often implicitly or explicitly specify the type of governance [

48]. An example is found in Brazil, where conservation units have been affected by bad government decisions by leaders who do not seek a balance between conservation and agricultural production, particularly with the mandate of former President Bolsonaro, in which he stated that the Brazilian government favors development over conservation [

49], words whose context was similar in the former president’s speech during his electoral campaign in 2018, where he stated that the state of Rondônia had many protected areas, words that are later evidenced by his terrible management in terms of environmental conservation in Brazil [

50]. Likewise, in Venezuela, President Nicolás Maduro announced that he would promote multinational mining concessions, which promote agriculture in the area to feed the miners, but the area with the concessions includes an extensive network of protected areas [

51]. According to Páez et al., the governance in protected areas that is applied in most Latin American countries is characterized by centralism and creates a government sphere with little public connection and interaction with citizens, and economic and political inequality that blocks many efforts at the expense of the most vulnerable, of the social and ecological future, and at the same time presents the case of the protected areas of the Province of Córdoba in Argentina, which presents a model of governance by government, which means that it is fundamentally subject to political interest, which does not guarantee conservation nor does it contemplate participation as an institutionalized mechanism [

52].

Otherwise, there are cases in which there is good management in protected areas and regulation for sustainability purposes that can go as far as restricting the implementation of agriculture in protected areas, due to the state of the territory or because the objective is only conservation (

Table 5).

Strong conservation objectives in protected areas allow maintaining the ecosystem services of these areas, in addition to mitigating the negative environmental impacts caused by uncontrolled agricultural activities. Such is the case of the Dominican Republic, where deforestation rates are higher due to agricultural activities, making it necessary to apply prohibitions on agricultural production and propose more sustainable alternatives [

56].

In addition, initiatives such as the creation of new protected areas are optimal for the conservation of vulnerable ecosystems, as is the case of tropical deciduous forests, one of the most vulnerable and unprotected ecosystems in Mexico. Therefore, in order to protect them, the Meseta de Cacaxtla flora and fauna protection area was created in the state of Sinaloa, considered one of the few sites in the Mexican Republic that still conserves well-developed ecological systems of a tropical deciduous forest [

57].

However, it is possible to maintain productive and conservation activities if limits and balance are maintained, with control over the use of natural resources, which is why there are protected areas where some activities are allowed, as long as they do not lose the sense of conservation within limits and certain types of crops that do not harm the health of the ecosystem. We observe that, for Brazil and Colombia, two articles mention permission to carry out agricultural practices in protected areas. In the Brazilian case, it was conveyed that the conservation of protected areas includes activities such as agriculture, as established in Law No. 9985 of 2000, which establishes the extractive reserve [

58]. In Colombia, it was ratified that agricultural activities as low-impact activities were stopped in Colombia, and farmers can grow onions or potatoes [

59].

Some entities or the state perform actions to encourage good agricultural practices in conservation areas and lead to the conservation of important ecosystems, as well as disincentives to abandon environmentally unfriendly agricultural practices, which mostly cause negative impacts, and degrade ecosystems (

Table 6).

There are positive cases in the agriculture-UC relationship that provide solutions and projections of a healthy relationship with the environment: in Peru, the National Service of Natural Areas Protected by the State (Sernanp) and the Frankfurt Zoological Society (FZS) developed a project with the farmers of the Lucuybamba community (located in the buffer zone of the Manu National Park) to conserve the Andean bear. They began by changing corn crops for golden currant, a profitable fruit that is not desired by the species, with the objective of reducing poaching and conflicts in the area, and added activities such as beekeeping and handicrafts, making the Andean bear their emblem [

66]. Additionally, according to Evans, conserving forests in agricultural landscapes can have a positive impact on the productivity, resilience, sustainability, and social equity of nearby farms, and in turn invites conservationists to be a little more flexible in what they carry out regarding protected areas, creating new approaches to conservation in landscapes where people coexist with nature [

67].

In Colombia, payments for environmental services enter as an alternative remuneration for sustainable practices or biodiversity conservation in rural scenarios; the strengthening of protected areas and regulations related to timber production through forest governance strategies are widely used tools to avoid unsustainable practices that can lead to forest loss [

68].

In Brazil, the Mamiraruá Institute, with the project “Conservation and Sustainable Use of Biodiversity in Conservation Units (BioREC)”, carried out with the support of the Amazon Fund and the National Development Bank, mapped agriculture in the Amanã Reserve, in the Amazon, through satellite images of the last 30 years to understand the dynamics of shifting agriculture. The results showed that, since 1988, around 6000 hectares of forest have been converted into agricultural areas by the residents of the Reserve, which occupies 2.3 million hectares, a number established within the limit of sustainable use by decree creating the conservation unit. In addition, 60% of the agriculture was carried out in reused areas that had gone through one or more fallow periods, thus reducing the pressure on the primary vegetation. Although the results are good, the researcher emphasizes the importance of continuous monitoring and sustainable actions [

69]. On the other hand, since 2016, the Brazilian Agricultural Research Corporation (EMBRAPA) has been developing and improving methodologies to measure the role of agriculture in the conservation of native vegetation, in permanent preservation areas, legal reserves, and other vegetation in Brazil. Through the records made by the farmers through satellite images, studies are carried out with geoprocessing of cartographic information of the native vegetation. And through the EMBRAPA website, it is possible to view all the information regarding the areas dedicated to the preservation of native vegetation in rural areas [

70].

Regarding experiences in agroforestry systems in protected areas, the municipality of Paraty (city of the State of Rio de Janeiro, Brazil) includes five conservation units of the Brazilian Atlantic Forest and there are agricultural activities around these units, which represent a threat to preservation; for this reason, agroforestry systems were established in the properties surrounding the conservation units in order to restore the areas and mitigate the negative impacts [

71]. Likewise, in Cuba, agroecological practices were introduced in the Viñales National Park protected area, and among the lessons learned is a greater awareness and participation of farmers in agricultural development, as well as conservation and reduction in rural emigration in the protected area [

72]. And there is also Paraguay, which incorporated agroforestry systems including Yerba mate (Ilex paraguariensis A. St-Hil.) in lands surrounding the Mbaracayú Forest Natural Reserve, with the aim of developing a landscape restoration model in the area of influence to the protected area [

73].

Finally, considering the information collected on illegal and prohibited crops, incentives, and regulations, it is possible to conclude the relationship between the protected area and agriculture, in which there is a bad relationship (with 52% of the news consulted) when some protected areas present a conflict due to the type of agriculture, the evasion of some norm or law with the implantation of some type of prohibited cultivation, or the affectation of some natural resource, among other cases; this causes a bad relationship between agriculture-protected area aspects. Avellaneda-Torres et al. [

74] highlight that conventional agriculture is in constant conflict where agricultural production is incompatible with the conservation of protected areas. In the opposite case, those areas with a type of sustainable agriculture generate a good relationship of this type of crops with the protected area; 48% of the news consulted has this characteristic, and as Possamai and Assunção [

11] mention, agroecology is a good strategy that can contribute to the conservation of the environment within protected areas.

4. Discussion

The purpose of protected areas is conservation, protecting biodiversity, maintaining the quality of watersheds, and taking advantage of the recreation of landscapes [

75]. But to maintain conservation, management of protected areas is necessary, which is essential to achieve the objectives of areas that are often threatened, not only by poor management, but also by the inclusion of illegal activities, such as in the case of Colombia in which protected areas are invaded by illicit crops, being a problem for management processes [

76]; Laurance et al. [

77] mention that financing for the management of protected areas is limited and many reserves are threatened by illegal crop invasion.

Latin American countries are characterized by having great natural wealth, but at the same time by the great destruction of their natural resources, often involving violence and corruption, which drastically affects the relationship between agriculture and protected areas. Roht-Arriaza [

78] emphasizes that the extraction of natural resources is generally induced and facilitated by corruption in permits, licenses, and export documents or in the ways of appropriating the exploited land, where the appropriation of land for marijuana cultivation also depends on the actions of corrupt officials and businessmen, legal or illegal. Likewise, for Lee and Kim [

79], corruption is directly linked to the management of natural resources, especially in Latin American countries that possess great natural wealth, and the authors point out that the causes of corruption are complex, but it is influenced by the abundance of resources they possess.

In this sense, press reports end up revealing that few countries stand out for having a sustainable relationship between the natural area and crops, and according to the results, it can be deduced that, in general, there are some factors that influence the poor relationship between agriculture and the protected area:

Abandonment of the government. From different perspectives, it is visible to detect government abandonment of protected areas, with reduced or no economic support initiatives, increased deforestation, and lack of control, among others, which do not offer the minimum environmental or social conditions [

80], just as it happens in the protected areas of the southern region of the Dominican Republic, which have been abandoned by the rulers in power [

81];

Lack of inspection of protected areas. Enforcement is a necessary activity for protecting protected natural areas, but unfortunately there is little or no investment, especially in developing countries [

82]. Salazar and Cuevas [

83] point out that in undeveloped countries there is no adequate attention to carrying out forestry inspections of protected natural areas, and environmental agencies do not effectively use their human and administrative resources in functions such as monitoring, control, and supervision, with the aim of complying with regulations; a specific case is of the protected natural areas of Mexico where the number of inspectors assigned to monitor forest lands has not grown in line with the greater number of hectares to monitor, despite the fact that complaints and forest deterioration have continued and increased;

Drug trafficking. In some Latin American countries, such as Peru, Bolivia, Paraguay, and Colombia, the planting of illicit crops or the felling of trees to open roads for drug trafficking is something that can be observed in the natural parks of these countries. According to Estupiñán [

84], the reasons for the presence of illicit crops in Colombia are due to government abandonment and, therefore, greater profitability of the product for not having options. Regarding Bolivia, Moyano [

85] mentions that, although agricultural activity is compatible with some management plans in protected areas, it is restricted for coca cultivation because it is an illegal crop and has implications for drug trafficking, as is the case in the Tipnis protected area and the Cordillera de Sama National Reserve (natural protected area);

Violence. In Colombia, violence marked the destruction of natural wealth by establishing guerrillas and other armed groups in Colombian Natural Parks to expand coca or poppy cultivation, managing to hide and protect illicit activities [

86]. In a specific case, armed groups in Colombia, especially FARC dissidents, are consolidating new territories in natural areas such as the Tinigua National Natural Park (a protected area) with coca crops, which causes the reactivation of old routes used in the past conflict, which in the long term will promote a new cycle of violence [

87];

Lack of regulation in protected areas. An example is the protected areas in Costa Rica, which, due to lack of control, affected the health of the local ecosystems; one of the cases is the Manuel Antonio National Park, where the situation reached the extreme of closing the entrance to visitors, due to little regulation, lack of control of management plans, and scarce presentation of environmental impact studies [

88].

Linked to the above, we found controversies in actions mainly repeated in the news information, such as deforestation; illegal planting; introduction of invasive species; implementation of monocultures; and bad agricultural practices, such as burning (

Figure 4).

We can see that the most denounced or highlighted action in the press is deforestation, the main action to be taken to establish crops in natural areas. Devine et al. [

89] mention that one of the causes of deforestation in protected areas in Latin America is the implementation of illicit crops (cocaine production in Colombia and Bolivia, and opium production in Mexico) and their transit routes (cocaine flows in Nicaragua, Honduras, and Guatemala), large-scale oil palm cultivation, and rice cultivation. But it is also due to the ravages of violence, as in the case of Colombia, where fumigation policies against drug trafficking are increasing the establishment of coca crops in protected areas to escape fumigation. These actions cause environmental damage, which are reported from the least serious to the most complex (

Figure 5).

Note that the most relevant negative impact is the loss of species in protected areas, followed by forest fires, fueled by other factors that may exist in the natural area. Devine et al. [

89] point out that deforestation in protected areas, one of its causes being the presence of illicit crops, generates large-scale environmental degradation with consequences for biodiversity, highlighting that narco-deforestation patterns are concentrated in the protected areas of Central America, which directly affects the ability to conserve and provide habitats for different species.

On the other hand, some advances were observed in the management of areas by governmental and non-governmental entities, as well as the inclusion of activities that promote a healthy relationship between agriculture and protected areas:

Establishment of boundaries in the protected area and with activities: The limits in a protected area are important both inside and outside the area, that is, in its surroundings (buffer zones), in order to maintain the balance and control of natural resources. An example of this is the establishment of agroforestry systems in the buffer zones of the Parque Serra do Brigadeiro protected area, which favor the conservation of local diversity (native species) and limit the introduction of potentially invasive foreign species that can affect the biodiversity of the ecosystems of the protected area; otherwise, there is a chance crops with little diversification are established, as is the case of monocultures [

90];

Creation of new protected areas and rules regulating permitted activities: We are currently experiencing a paradigm shift, where previously the preservation of the environment was a fanatical movement of ecologists or conservationists, and today is an object of government, which aims to protect natural resources, the natural wealth of each country; this involves the case of the creation of the Bellavista Private Protected Area in Ecuador, which began as an initiative of conservation and ecotourism, until the declaration as the first private protected area of the National System of Protected Areas (SNAP) in 2019. Land that years ago was populated by farmers who left the area because it was unfeasible to market their products, in which there were deforestation practices of the native forest of the place [

91];

Encouraging good agricultural practices and discouraging bad agricultural practices: According to Figueroa et al. [

92], in Latin America, projects have been carried out to encourage good agricultural practices, such as payments for environmental services (PES) in agroforestry systems, whose purpose is to internalize the value of environmental services by paying those who maintain land use through sustainable activities, and are carried out through programs such as those of the Latin American Network of National Parks and Protected Areas (REDPARQUES) with the support of different governmental entities;

Launching programs or initiatives that create healthy links between agriculture and protected areas: There are initiatives that create healthy links between agriculture and protected areas, as is the case of the implementation of agroforestry systems of corn associated with timber trees in the natural resource protected area of La Frailescana in Mexico, which aims to increase the value of the land, as well as mitigate and adapt to climate change [

93];

Return to ancestral techniques that favor conservation: In Peru, Argentina, Bolivia, Chile, Colombia, Ecuador, and Mexico, the ancestral technique of Sowing and Harvesting Water (SyCA) is used, mostly in protected areas, in which precipitation and runoff water is collected and then infiltrated into the subsoil, and sown and recovered after a while (harvesting), in the discharge of springs, streams, and wells that benefit from the infiltrated water. This technique can be considered green infrastructure that contributes to sustainable agriculture [

94];

Support from institutions and research to strengthen healthy relationships between agriculture and protected areas: Based on global goals, such as the “30% by 2030” objective, established at the 15th Conference of the Parties to the United Nations Convention on Biological Diversity, whose purpose is to promote the protection of 30% of our entire planet by 2030, institutions and research have joined forces to promote sustainable actions to achieve this goal. For example, to achieve healthy relationships between agriculture and protected areas within this global target framework, Barborak [

95] mentions the following:

“Achieving the 30 × 30 goal requires the use of active management tools for protected areas; the promotion of agricultural, forestry and fisheries certification, as well as import restrictions on products such as seafood, coffee, timber, meat, soybeans and African palm, when not produced sustainably, is creating powerful positive incentives in favor of active and adaptive management, based on inventories and monitoring of resource status, also considering the economic well-being of the populations that depend on the use of those resources. At the same time, there is much greater use of technologies, such as remote sensing, drones, and camera traps, to assist in resource monitoring and management.”

News of a good relationship between protected areas and agriculture was reported with descriptions of agroecological initiatives that seek to harmonize conservation objectives with social development, such as the cases of Peru and Brazil, which mention good practices in agriculture or establish new areas of environmental protection. In the case of Brazil, for example, the insertion of agroecology has achieved a way of working that guarantees a secure income and does not destroy the environment, and involves equity for farmers, in addition to sovereignty and food security. In conservation units of sustainable use, agroecology is an alternative to family farming, and the state plays a fundamental role in this scenario with public policies. Therefore, agroecology is a viable path in protected areas, which together with the support of research, contributes to the proper use of natural assets by traditional communities in conservation units [

11].

5. Conclusions and Future Prospects

It can be concluded that the relationship between agricultural activities and protected areas or conservation units presents light and gray tones; that is, we see an evident pattern between the different Latin American countries, characterized by activities that affect conservation objectives such as illegal plantations and those that are not permitted, and a lack of regulation and management, but on the contrary, we also find positive activities that promote conservation objectives such as sustainable initiatives and good agricultural practices. Likewise, although Latin America is the region richest in biodiversity and has the largest number of protected areas, the social and political context marked by state abandonment, violence, and corruption affects the protection of these areas. Even the natural wealth itself, characteristic of these areas, manages to awaken greed that, with political objectives, diverts conservation efforts.

It is necessary to study in depth the impact caused by deforestation for crops in the protected areas of Latin American countries, which has the greatest negative impact on ecosystems, since forests are the habitat and allow the diversity of many species, as well as the availability and quality of water. Furthermore, it is pertinent to open the possibility of comparing the results obtained from the Latin American region with those of any other geographic region, so that the weaknesses and strengths of the different territories can be analyzed.

Finally, although various actions and instruments have been detailed to achieve sustainability among protected areas in conjunction with agricultural activities, changes are still required at the political and governmental levels to create radical advances. It is essential to increase agricultural activities under conservation schemes, with good agroecological practices, resuming ancestral activities, establishing limits, performing diagnoses, controlling and monitoring areas, and training and educating farmers, which are key to living in harmony with the natural environment, recognizing that we need good health of ecosystems to have a prosperous future and thus obtain food security.