Abstract

The study examines the relationship between the eating habits of the families of children attending primary school and the appreciation of the meals served in school canteens during the COVID-19 pandemic in Italy. The analysis focuses on the disruptive effects of the lockdowns imposed from March 2020 onwards to contain the spread of the virus. Restrictions to mobility had an impact on family routines, changing eating habits, meal schedules, and food preparation. The extended time spent at home, combined with distance learning and the closure of school canteens, had a lasting impact on children, particularly on their attitudes toward food and their appreciation of school meals after reopening. Through qualitative and quantitative research into the eating habits of 592 families of 1092 pupils attending primary schools in different regions of Italy during the pandemic, this study highlights the influence of adult eating habits on children’s appreciation of food and allows critical insights into the sustainable school food policies implemented at the time. The findings provide a basis for advocating an alliance between schools and families to promote food education and address deficiencies in collective catering policies, which may hold strategic potential, especially during the ecological transition.

1. Introduction

This article examines the disruptive impact of lockdowns on family food habits during the COVID-19 pandemic in Italy, particularly their influence on children’s eating patterns and attitudes toward food, including their appreciation of school canteen meals. By analyzing these pandemic-induced disruptions in children’s eating routines, the study provides insights for developing more sustainable food policies and catering practices within educational contexts, fostering a new alliance between schools and families.

The COVID-19 pandemic significantly altered domestic routines and social dynamics [1], affecting food patterns and behaviors [2], especially among younger people [3]. Italy experienced a nationwide lockdown from March to May 2020, followed by region-specific closures and mobility restrictions. Lockdowns, the suspension of outdoor activities, along with the shift to remote work, school closures, and restrictions on social life (including eating out), restructured daily food-related routines [4] (p. 203), impacting how people procured and consumed food both at home and outside. Campaigns promoting staying at home fostered a home-based lifestyle, elevating the home as a refuge and increasing time spent in the kitchen, with greater enjoyment of cooking and eating [5]. In the early pandemic, recommendations to limit grocery trips and restricted access to fresh food markets encouraged stockpiling or excessive food purchases [6], and heightened reliance on staples (rice, pasta, bread) and nonperishable foods (canned goods), impacting dietary patterns [7] (p. 10), with an overall generalized weight gain in the population [8].

School catering services also faced prolonged closures, during which approximately 160,000 Italian children lost their only healthy and complete meal of the day [9,10], exacerbating the issue of altered nutrition in the absence of school meals [11,12,13,14]. Social isolation and forced cohabitation increased screen time, social media challenges, and fragmented snacking, leading to irregular and emotional eating, especially among young people [2]. Paired with limited access to psychological services, these changes contributed to generalized anxiety and post-traumatic stress syndromes, major drivers of eating disorders [15,16]. A review of 53 international studies in 2021 reported a 36% increase in eating disorders among young people worldwide, predominantly females aged 15 to 25, resulting in a 48% rise in hospitalizations [17]. An inquiry by the European Parliament estimated that approximately 20 million Europeans suffer from eating disorders, with 3 million cases in Italy alone [18]. Since the onset of the pandemic, one in ten children in Italy has shown symptoms of eating disorders [19] (p. 128). Upon school reopening, perduring strict social distancing and hygiene measures requiring the use of outsourced meals in isothermal, pre-portioned containers led to diminished flavor, reduced enjoyment and nutritional value, and increased plastic and food waste [20]. These changes affected children’s appreciation of school canteen food and, even more so, their parents’ perceptions. This is evidenced by research conducted by the Milan Municipality in 2021 and 2022, involving 2900 primary school children and their families, which shows that children’s average reported appreciation of school meals declined from a mean score of 2.76 in 2016 to 2.71 in 2021 [21] (p. 14), and that 51% of parents reported their children disliked the school meals (p. 22).

Although these disruptions—turning food into a source of stress, fear, anxiety, or all-day snacking—heightened risk factors for eating disorders, they also created opportunities [4], notably fostering family involvement in cooking and encouraging children to engage more creatively with food [2,5]. These shifts in attitudes toward food, both at home and outside, intersect with the moral sense children acquire through family upbringing. According to Piaget [22], children experience cognitive conformity until around age 11, when they begin to deviate from family rules and conform to peer-defined norms [23]. Building on these ideas, Kohlberg [24] identifies three phases of moral development: pre-conventional, conventional, and post-conventional, each with two stages. Children aged 8–11, at the boundary between pre-conventional and conventional stages, are still guided by immediate, conservative moral reasoning (e.g., avoiding punishment/obtaining rewards) but begin to shift toward seeking social approval through adherence to the social order [24]. Recent post-pandemic literature on the influence of home meal routines on children’s dietary behavior [25] and the significant role of parents in shaping their children’s food choices, both at home and at school [26], highlights the extent to which parents’ attention to food, perceptions of food quality, and involvement in food-related education contribute to their children’s dietary behaviors and ultimately influence whether they consume meals at school.

This awareness emphasizes the need to focus on family food habits and dietary styles, particularly their impact on pre-teen children during the pandemic, as reported by parents. It also highlights the challenges school canteens faced in adhering to sustainable food procurement policies while fulfilling their redistributive and educational roles. During the pandemic, a regulatory framework—introduced as an uncertain adaptation of the EU’s “Farm to Fork Strategy” [27]—imposed stricter yet often contradictory sustainability requirements for public food procurement [28]. These regulations led to abrupt menu changes, frequently disconnected from children’s food habits, which increased waste and undermined the crucial role of school canteens in promoting adequate food access. In Italy’s predominantly public education system, families contribute to the cost of school meals based on their economic situation, and in cases of insufficient financial capacity, the municipality provides financial support. Thus, school canteens play a vital role in ensuring equitable access to food and promoting healthy, sustainable diets despite socio-economic inequalities. But, precisely because of this democratic prerogative and given parents’ financial contributions to school meals, it is essential to promote their engagement in decision-making processes [29] and involve them in the co-creation of sustainable menus [30], ideally—as suggested by this study—as part of an educational pathway that connects school and family.

This study addresses the research gap of a missing comprehensive, multi-stakeholder investigation into food-related disruptions caused by the COVID-19 pandemic, both at home and in school canteens. Using a multidisciplinary approach involving parents and teachers, the research explores children’s disrupted eating habits (at home and at school), the weakened connection between family eating habits and school meals, and the effectiveness of sustainable nutrition policies implemented during that time.

2. Materials and Methods

Based on these premises, a research project titled “Nourishing School” was carried out by the University of Gastronomic Sciences in partnership with CIRFOOD Italy [31], a major provider for Italian school canteens, and the Food Policy of Milan [32]. The study employed both qualitative and quantitative methods. A convenience sample of the families of 1092 children attending all grades of ten public primary schools across northern, central, and southern Italy offering canteen services was formed. Within this research, a separate study directly involving the children was conducted but is not covered here [33], except for some data on unfinished food [see Section 4.3], as this study focuses solely on their families.

Given the unprecedented circumstances, the authors adopted an exploratory research approach to capture disruptive domestic patterns, emerging trends, and their relationship with evolving food-related values. Consistent with the cited literature, they initially formulated broad hypotheses. These initial hypotheses included the idea that the COVID-19 pandemic, particularly the prolonged lockdowns, may have disrupted family food-related routines and patterns [1,2], impacting perceptions of food and eating behavior [4,5] in both adults [3,6] and children [15,16,17,19], given the assumed continuity between them at that age stage [22,23,24,25,26]. This disruption could have implications for children’s appreciation of school meals [9,10,21], with some changes potentially persisting post-pandemic, offering lessons for parents, teachers, and other stakeholders.

2.1. The Qualitative Exploration of the Hypotheses

These general hypotheses were first explored through qualitative focus groups with parents and teachers from the selected primary schools. Focus groups are an effective method for eliciting detailed opinions on research sub-areas [34], aiming to gather ideas, suggestions, and considerations through open discussions relevant to the study [35]. They spark interactive debate, guided by a moderator steering the discussion toward the research objectives. This method benefits from participants’ reactions and their responses to others’ reflections, fostering deeper insights.

Three focus groups were conducted between January and February 2022. They were held online, as Italy’s health emergency—which restricted travel between regions, school access, and in-person gatherings—was not declared over until 31 March 2022. The focus groups, involving 22 participants (13 teachers and 9 parents), were recorded with participants’ written consent and transcribed for analysis. The number of participants was determined by their roles and availability. The teachers were selected from deputy school coordinators and those responsible for monitoring their classes’ meal consumption, a role that involves eating in the canteen with the children, providing us with a privileged perspective on the process. The parents were chosen from class representatives or members of canteen committees, a voluntary group of parents with school-aged children who use the school catering service. All participants were deeply involved in their children’s school life and the dynamics of the school canteen, providing valuable insights into the phenomenon under investigation. This engagement fostered open dialogue between parents and teachers, reducing any sense of inhibition and compensating for imbalances. Bringing these figures together was a key aspect of this research, aimed at fostering dialogue between the primary stakeholders—school and family—and gaining a comprehensive understanding of the complex issue of sustainable school canteens. An alliance between school and family, seen as a crucial strategy within educational policy to promote healthy and sustainable eating habits, is among the goals of this research.

Each focus group lasted approximately two hours and was facilitated by two researchers. The participants’ distribution was as follows:

- Five teachers and four parents from a primary school in Formigine (Emilia Romagna);

- Five teachers and two parents from a primary school in Perugia (Umbria);

- Three teachers and three parents from a primary school in Monfalcone (Friuli Venezia Giulia).

The above hypotheses led to the following questions:

- Q1:

- Have there been any changes in family eating habits involving children? The focus was on the following dimensions:

- Modalities: meal times, eating together, cooking together, use of food deliveries;

- Primary person responsible for meal preparation/delivery;

- Diet: new foods introduced or removed, new priorities, etc.

- Q2:

- Have these changes impacted perceptions of food and eating behavior?

- Q3:

- Which changes do you think will persist post-pandemic, and which won’t?

- Q4:

- What lessons have been learned about children’s relationship with food during the pandemic that can help school canteens better meet users’ needs, reduce food waste, and transform into educational spaces that promote a sustainable food culture?

2.2. The Quantitative Investigation by Survey

The insights gained from the focus groups enabled a more specific and in-depth formulation of the initial hypotheses, which were subsequently reorganized as follows:

Hypothesis 1:

The outbreak of the COVID-19 pandemic has disrupted domestic food-related routines [1,2], and heightened risk factors for eating disorders [3,6], especially in young people [15,16,17,18,19].

Hypothesis 2:

The significant restructuring of daily routines [5] created opportunities for a more mindful and sustainable approach to food [4], particularly for families already inclined to these dietary styles.

Hypothesis 3:

As children adopt their family’s eating habits [22,23,24,25,26], parents’ reports of disrupted patterns [7,8] can provide insight into children’s altered approach to food during extended school absences [11,12,13,14] and help improve attitudes toward school meals [9,10].

Hypothesis 4:

Understanding changes in children’s food behaviors helps align their evolving attitudes with healthier, more sustainable school meals [9,10], thereby reducing food waste and improving procurement policies [28], while also strengthening the family–school relationship [30] and positioning school canteens as educational spaces.

To test them on a larger scale, a survey was designed for the families of children attending the ten schools in the study. The survey, distributed online via Qualtrics (Version 2020, Qualtrics © 2020) from March 2022 to February 2023, targeted families through convenience sampling, with schools serving as the primary channel to reach families and encourage their participation. Convenience sampling, commonly employed in educational and social sciences to access otherwise hard-to-reach populations [36,37,38], was the only feasible approach given the challenges of reaching children and families during the tail end of the health emergency. The target population included families of over 1902 children attending all grades of primary schools with canteen services. Findings from the survey directly involving children are excluded here, as they are the focus of another study [33], except for certain relevant results on food waste, which are referenced in Section 4.3. To mitigate the bias of non-probabilistic sampling, we increased respondent numbers and distributed them across Italy’s main regions to capture the country’s diverse characteristics.

Participation criteria required consent to the survey, and the role of the parent or adult responsible for the family’s care and meal preparation, serving as an initial filter to ensure qualified respondents. The online questionnaire comprised 30 questions—29 closed and one open-ended (Q24bis)—across four sections, generating 70 variables (see Table 1). Each section addressed key dimensions for capturing shifts in food-related habits and routines. These changes were examined directly in relation to the adults and indirectly for their children, based on respondents’ perceptions and reported behaviors.

Table 1.

The Survey on Family Food Habits and Dietary Patterns During the Pandemic.

Based on the initial filter—the adult primarily responsible for food-related activities in the family—the survey was intended for individual completion rather than by all family members. While many questions addressed practices involving other or all family members, responses were always provided from an individual perspective.

The survey operationalized the research hypotheses and insights from the focus groups. The socio-demographic section, which formed the first part of the survey, included questions about individuals’ characteristics, including personal income. The latter was presented in brackets of yearly gross income, largely aligned with the Italian taxable base and reflecting key economic divisions within the Italian context. The decision to inquire about individual income was based on two main reasons: (1) it is easier for participants to report personal income rather than calculate household income, which could be time-consuming (potentially discouraging participation) or compromise response accuracy; (2) since family outreach was mediated by schools (which distributed the survey link and encouraged participation), respondents were reluctant to share highly sensitive family information, despite assurances of full anonymity and compliance with European privacy regulations.

Section 3.2 addressed Hypothesis 1; specifically, Questions 17 and 18 examined changes in family cooking and eating routines; Questions 19 to 21 focused on perceived changes in children’s eating patterns and preferences at home; and Question 22 (including sub-questions Q22_1 through Q22_4) explored the implications of these changes, particularly regarding children’s weight variations.

Questions 27, 23, and the entire Q24 battery, which examined perceived changes in food provisioning (e.g., delivery), food quality, and new foods introduced into the diet, explored Hypothesis 2. This hypothesis was also partially addressed by Question 26, which looked at changes in meal duration patterns, particularly alongside Questions 10 through 15, which investigated family eating practices, dietary habits, and meal arrangements.

Question 28 and the Q29 battery, focusing on parents’ perceptions of their children’s after-school appetite and appreciation of school canteens, addressed Hypothesis 3.

The entire survey addressed Hypothesis 4, offering insights to help school canteens manage pandemic-related disruptions while tackling sustainability challenges and transformations required by evolving food procurement policies. This hypothesis posits that research data can support canteens in better meeting changing needs, broadening children’s palates, and reducing food waste, while also serving as educational spaces that promote a sustainable food culture and provide valuable insights for policy development.

2.3. Multivariate Analysis: Multiple Correspondence Analysis (MCA) to Detect the Relationships Among the Data

To synthesize the data, we first identified correlation patterns and strengths among the 12 variables from the third key section of the questionnaire, which explored changes in family value-based motivational drivers and prioritized food characteristics since the pandemic’s outbreak. We applied multivariate statistical techniques, starting with Multiple Correspondence Analysis (MCA), a method suitable for categorical variables like ours. MCA detects groups of individuals with similar profiles (clusters) and associations between categorical variables (relationship patterns) [39]. It generalizes simple correspondence analysis, limited to two variables, and extends principal component analysis to categorical data [40]. The variables examined include Brand, Made in Italy, Traceability Origin DOP, Local Km0, Fresh Seasonal, Environmentally Sustainable Zero Waste, Natural Bio Non-GMO, Ethical Fair Animal Welfare, Eco-friendly Recyclable Packaging, Affordable Price, Diet Without, and Halal/Kosher Cultural Rules. These categorical variables use a 1–3 scale, where 1 is the lowest value (never, not at all), 3 is the highest (always, very much), and 2 represents intermediate values. MCA is ideal for exploring these associations. We conducted MCA using R software [41] with the MCA() function from the FactoMineR{} package [42] and visualized the results with factoextra{} [43]. The distance between row or column points indicates similarity or dissimilarity, revealing association patterns. On the factor map, row points with similar profiles are positioned close together, as are column points. Variables farther from the origin reflect distinct behaviors, while those closer to the origin represent more average, less distinguishable patterns.

2.4. Exploratory Factor Analysis (EFA) to Detect Hidden Correlation Patterns in the Observed Variables

MCA identified the most important variables, highlighting those with strong correlations. To further explore these correlations and uncover latent factors behind observed behaviors, we used Exploratory Factor Analysis (EFA). EFA revealed key variables linked to underlying patterns, helping us identify the motivational and evaluative factors influencing food purchasing choices and domestic consumption among the families studied. We conducted a factor analysis on 37 highly correlated variables (from the original 70) related to both motivational drivers for food purchasing (the same variables used for MCA) and eating habits (e.g., cooking frequency, meal routines, eating patterns) since the pandemic’s onset. Factors were extracted using principal component analysis (PCA) after converting categorical variables into numeric ones via CatPCA.

3. Results

3.1. Focus Group Findings on Children’s Eating Patterns at Home and School During Lockdowns

For each question posed during the focus groups with families and teachers, we highlight the key findings from the interviews, with school names encrypted for privacy.

3.1.1. More Cooking, More Eating, More Weight

The main finding regarding changes in family eating habits during the lockdown is that some parents resumed cooking more complex recipes, particularly baked goods, with their children. This involvement allowed them to reconnect with family and rediscover the pleasure of eating together, which had previously occurred only on weekends. Other parents reported persistent weight gain in their children due to increased food intake, inactivity, and heightened “voraciousness”.

The children started eating more. With little supervision and plenty of free time, the youngest daughter in particular ate more between main meals.(Dad D., School 1)

As both a teacher and a mother, I’ve noticed that the relationship with food has become voracious. For very active children like mine, being stuck at home caused a lot of stress, which was channeled into food. Now, even when he plays, he wants food, despite my efforts as a mother to pay close attention to quality. As a teacher and canteen referent, I have observed similar behaviors in the school canteen.(Teacher L., School 3)

Meal rhythms were disrupted, with more frequent snacking, especially after hours. Those left alone with working parents had unsupervised access to food, contributing to weight gain and lack of physical activity.

My husband and I continued working during the lockdown, and not always remotely. Especially when the kids were home alone, without adult supervision, they had unrestricted access to the pantry. Snack consumption between meals increased, and physical activity decreased.(Mum S., School 1)

Children ate more, possibly as emotional compensation for the distress and due to distance learning.

The distance from their classmates, the boredom during online lessons, hours of TV—it’s clear that when they don’t know what to do, they eat, and the easiest things to grab are the sweetest or most calorie-dense foods.(Dad G., School 2)

Eating has become a ‘release’; they eat either because they’re bored or because they’re excited by video games, spending hours on their smartphones playing or watching videos.(Mum B., School 2)

More time at home also led to more meals at home, with pizza delivery used for dinner multiple times a week. Delivery was one of the novelties, mostly associated with “junk food”, but in some cases, it also served as a vehicle for lighter meals or foods from other cultures.

My children didn’t use it (i.e., delivery) much during lockdown, but when they did, or still do, we declare it ‘junk night’, and everyone orders what they want. On junk night, the girls introduced poké, which gives the impression of having a lighter meal, although they end up loading it with sauces and toppings. The boy, on the other hand, doesn’t.(Mum R., School 1)

3.1.2. The Canteen, a Location of Sociability, with Some Problems During the Pandemic

Regarding changes in food perceptions and dining behaviors, the closure of the canteen removed an important source of regularity and quality. The canteen also provided a social time with friends, maintaining an integrative and convivial atmosphere during the pandemic. Upon the reopening of canteens, a positive change was that children no longer had to eat in the classroom, a practice that had previously diminished their appreciation for school food.

During the pandemic, even when children could return to school but the canteens were closed, they had to eat in their classrooms. A staff member would go from class to class with a cart to serve the meals, which caused the food to cool down, making it less enjoyable for the children.(Teacher L., School 3)

However, the new hygiene rules did not help improve children’s perceptions of the canteen, which worsened due to longer waiting times, leading to lower food quality (“cold food, overcooked pasta”), less varied and healthy mid-morning snacks, and increased selectiveness after becoming accustomed to home-cooked meals. Overall, children enjoy school meals less than before.

Some HACCP regulations have changed: teachers are currently not allowed to serve food to children or redistribute leftover food, particularly from one-dish meals. They must wait for authorized staff. This has significantly prolonged the serving process, which, in addition to generating waste, causes children to lose focus and interest in their meals.(Teacher S., School 2)

The situation at school has worsened: children’s appreciation for the food, especially vegetables, legumes, and pasta, has decreased. During the lockdown, families developed the habit of avoiding pre-packaged food and preparing meals themselves, learning to diversify their meals and experiment with recipes. As a result, children now refuse pre-portioned meals, particularly vegetables, which tend to be lightly seasoned or completely unsalted.(Teacher L., School 3)

With the pandemic, my eldest daughter (9 years old) changed her eating habits and rhythm. Now, at home, she eats more and more varied foods, but at school, she hardly eats anything. When she comes home, she’s hungry, and her snack is no longer a piece of fruit but a cheese sandwich or she asks to make crepes.(Mum D., School 3)

3.1.3. The Serious Consequences of the Pandemic

Regarding the third question on lasting changes beyond the pandemic, respondents noted that it profoundly impacted their lives and those of their children, with increased anxieties reflected in food habits, behaviors, and relationships, particularly among older children. Some children are now fixated on COVID-19, fearful of contact, and frequently sanitizing their hands.

Parents have passed their anxieties onto their children: you don’t hug because you have a cold, and the spontaneity of hugging and social interaction has been lost. Everything has become a source of fear; even sharing snacks is now an issue. Before, the children would trade snacks, but now that doesn’t happen anymore, especially among the older ones who understand the risk of contagion.(Teacher S., School 2)

Many adults have also grown accustomed to “non-contact” and staying indoors, feeling discomfort in resuming pre-pandemic habits. In some cases, this led to a rediscovery of cooking and greater mindfulness around eating.

Our habits have changed; we eat out less and prefer to stay home and cook something more elaborate together. We’ve learned to vary, but above all to empty the fridge and pantry before grocery shopping again, and we often use dry foods that we usually don’t have time to prepare, like legumes, or we cook meals that we then freeze.(Mum B., School 3)

Some parents describe these as “stolen years”, noting that children now fear physical contact and are less familiar with it.

3.1.4. School–Family Collaboration, an Educational Canteen

Regarding the fourth question on lessons from the pandemic related to the canteen, a key takeaway is that food reflects broader situations, particularly how children experience family life. Excessive screen time has heightened anxiety, and stronger collaboration between school and family is needed, as children’s feelings mirror home experiences, prompting changes in family food habits. Another lesson is the need to extend canteen time, as food is intertwined with other aspects of social life. Incorporating playtime during meals can foster awareness of what is being eaten.

To get children to eat their vegetables, you need to turn it into a game. We came up with ‘superhero pumpkin and carrot soup’ and even took photos of them eating it to send to their moms.(Teacher C., School 3)

Children have also improved in evaluating canteen food quality compared to home food, and reducing food waste remains crucial. The pandemic highlighted the need for serious nutrition education for both children and adults.

It would be better to provide HACCP training for teachers so they can help children avoid generating waste.(Mum V., School 3)

In first grade, young children tend to eat very slowly. On average, out of 18 students, only 3 or 4 finish their meals, while the rest typically leave food unfinished, especially vegetables. They should be able to receive assistance and encouragement from the teacher to help them eat.(Teacher L., School 1)

3.1.5. Overall Evidence from the Qualitative Exploration

To summarize the diverse findings from the qualitative survey, the key takeaway is that the pandemic, along with the changes it brought to food-related patterns at home—some positive, encouraging greater attention to food, and others negative, heightening anxiety and overeating—necessitates a rethinking of school canteen organization with increased awareness of home meal dynamics.

Canteens offer valuable opportunities for nutrition education and waste reduction. Using local food to ensure freshness, safety, and sustainability is a significant but insufficient driver for providing a varied menu. Ongoing collaboration between schools, teachers, and families is crucial to designing improvements that meet users’ needs.

3.2. Findings from the Quantitative Survey on Children’s Eating Patterns During Lockdowns

3.2.1. Descriptive Findings: The Characteristics of the Achieved Sample

Qualitative research findings informed the design and analysis of the subsequent quantitative survey. Of the 746 families who completed the survey, 592 passed the validation process. The distribution of these families reflects the locations of the ten primary schools involved, as shown in Table 2.

Table 2.

Primary schools’ names and geographic locations.

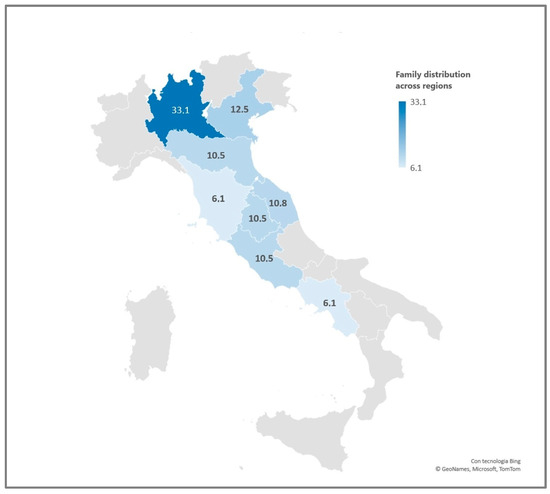

The surveyed families are primarily from central and northern regions, with Campania as the only representation from the south (Figure 1 and Table 3).

Figure 1.

Distribution of surveyed families across Italian regions.

Table 3.

Socio-Demographic Characteristics of Families.

In socio-demographic terms, 88% of respondents are women and 12% are men. This gender imbalance reflects the initial filter, which allowed only the parent or adult responsible for family food care to complete the survey, underscoring a persistent gender divide in caregiving roles among the surveyed families. A majority (56%) of respondents are based in the north, and 86% are married or cohabiting, with an average age of 46, suggesting that children were typically born when parents were between 36 and 41. Family composition predominantly includes three to four members, typically two parents and one or two children under 16. Respondents generally have good educational backgrounds, ranging from high school diplomas to master’s degrees, with personal gross yearly incomes concentrated in the EUR 15,001–EUR 28,000 (31%) and EUR 28,001–EUR 55,000 (22%) brackets. Additionally, 69% hold permanent employment.

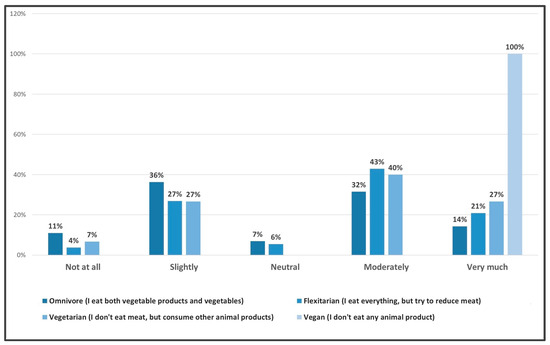

Regarding dietary preferences, 66% identify as omnivores, 31% as flexitarians, and 3% as vegetarians, with only 1% being vegan. While 45% of respondents report regular family vegetable consumption, daily intake is only 38%. Over half (53%) of the children prefer vegetables, with children of vegetarian or vegan parents showing notable appreciation (Figure 2).

Figure 2.

Children’s appreciation of vegetable-based meals (as reported by parents), by family dietary style.

During the lockdown, respondents increased time spent cooking with their children by 39%. This is notable, given that 62% of respondents reported typically spending 30 min to 1 h daily on cooking, reflecting time-saving and convenient dietary habits. This rise is likely due to 74% of respondents working remotely (only 31% worked in person), allowing more time at home for cooking and enjoying meals together. However, it also led to children eating more during the day (+23%), especially when unsupervised (+17%), often while watching films or playing video games (+14%) and frequently out of boredom (+37%), anxiety, or agitation (+24%).

While these data highlight family consumption habits and perceived changes, they do not fully capture the underlying values or food culture influencing children’s behavior during the lockdown, nor can they determine which variables are most critical for future food-related behaviors. To explore these aspects, multivariate analysis is needed to identify correlations between observed variables and hidden patterns driving behavior. This approach simplifies analysis by revealing key variables that capture in-depth changes in the surveyed families.

3.2.2. Explanatory Findings: The Results from the MCA

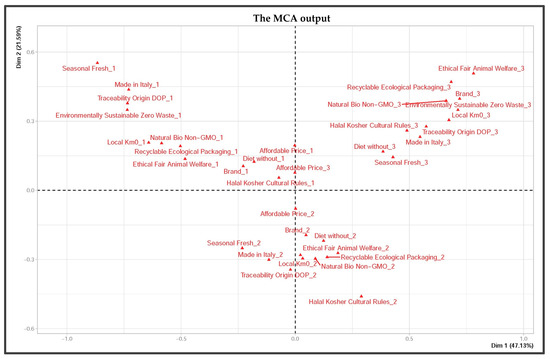

To evaluate variable representation quality, we used squared cosine (cos2), which indicates the strength of the link between variable categories and an axis. As shown in Figure 3, a sum of cos2 values close to one suggests a good representation across two dimensions.

Figure 3.

The MCA output. Points represent the exact positions of the variables on the plot, while lines connect the points to the variables’ names.

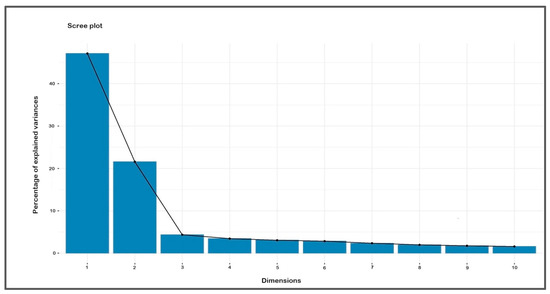

The scree plot in Figure 4 shows that the first two dimensions capture 68.7% of the total data variation, highlighting the key variables that account for the observed behaviors. The variable categories most contributing to these two dimensions include Made in Italy_1 (9.00%), Made in Italy_3 (7.78%), Traceability Origin DOP_1 (10.57%), Traceability Origin DOP_2 (7.00%), Traceability Origin DOP_3 (8.39%), Local Km0_1 (8.21%), Local Km0_3 (9.34%), Fresh Seasonal_1 (7.58%), Environmentally Sustainable Zero Waste_3 (9.53%), Natural Bio Non-GMO_1 (7.54%), Natural Bio Non-GMO_3 (9.00%), Environmentally Sustainable Zero Waste_1 (10.41%), Ethical Fair Animal Welfare_3 (9.17%), and Eco-friendly Recyclable Packaging_3 (8.52%). All these variables show cos2 values greater than 0.70, indicating strong representation across two dimensions.

Figure 4.

Scree plot of the dimensions contributing most to the data variance in the analysis.

While numeric output is omitted for brevity, most cos2 values exceed 0.50, except for Affordable Price_2, Affordable Price_3, Diet Without_2, and Halal/Kosher Cultural Rules_2, which are less distinctive of our surveyed consumers. Variables with cos2 values above 0.70 best represent consumer behaviors, highlighting a polarization between identity and ecological considerations.

3.2.3. Explanatory Findings: The Results from the EFA

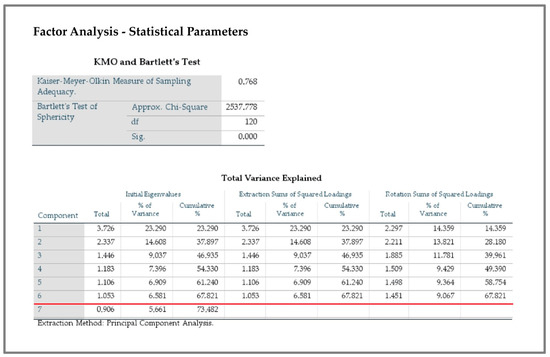

The statistical parameters in Figure 5 (KMO close to 1, Bartlett’s Test of Sphericity < 0.01) confirm the sample’s suitability for factor analysis. The optimal solution includes six components (those with an eigenvalue > 1), which together explain over 67% of the total variance (Figure 6).

Figure 5.

Statistical parameters and explained variance of the best EFA solution. (Figure and statistical calculations generated using IBM SPSS Statistics, version 29.0.0.)

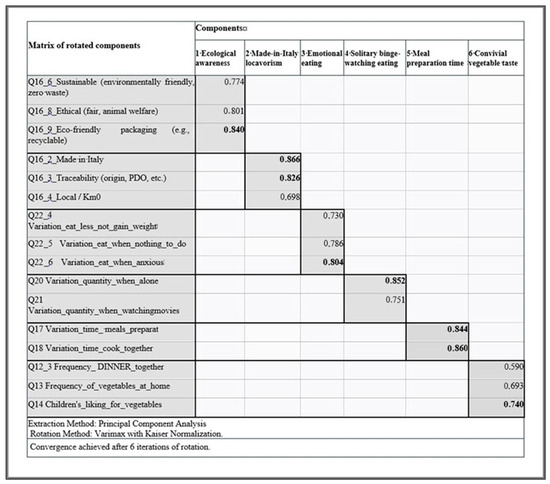

Figure 6.

EFA: the six factor components underpinning the food-related variables in the survey. The factor loadings in bold highlight the variables that weigh the most in this factor structure.

As shown in Figure 6, the EFA identifies two key components defining the food consumer profile of surveyed families during the lockdown: F1, “ecological awareness”, and F2, “Made-in-Italy locavorism”, confirming the preliminary MCA findings. These components demonstrate high reliability (Alphas 0.812 and 0.822, respectively) and account for 42% of food preferences and purchasing decisions after rotation.

A third component, F3, “Emotional Eating”, reflects parents’ perceptions of their children’s emotional strain and meal-related neuroticism since the pandemic. Though less influential, it remains significant, with a Cronbach Alpha above 0.70. This factor relates closely to F4, “Deregulated Meal Patterns”, which, despite weaker reliability (0.541) and not emphasized in descriptive analysis, still contributes to the perceived disruption of children’s habits.

Components 5 and 6 focus on the social dynamics of meal preparation and consumption during confinement. F5, “Meal Preparation Time Together”, captures increased interaction from schedule adjustments, while F6, “Convivial Vegetable Taste”, combines a preference for vegetables with social evening gatherings, where dinner remains the main meal.

These components, representing the “food cultures” of families, reveal significant regional differences in their distribution, which were assessed using the non-parametric Kruskal–Wallis test. The analysis highlights notable disparities across regions for three of the six factors analyzed. Factor 2 (p = 0.009) and Factor 3 (p < 0.001) show geographically varied distributions, indicating differences in preferences for local foods and the emotional charge associated with meals. Factor 6 (p < 0.001) highlights notable regional variations in convivial habits related to vegetable consumption. The other factors (F1, F4, F5) show no significant differences, suggesting uniformity across regions in ecological awareness, solitary eating habits, and time spent on meal preparation.

Pairwise comparisons reveal a consistent north–south gradient for the three significant factors. For Factor 2, Campania exhibits a lower preference for Italian foods compared to central and northern regions, with the most significant difference seen with Marche (p = 0.002). For Factor 3, reflecting a more anxious or emotional approach to meals, levels increase progressively from north to south, with Lazio showing slightly heightened emotional associations and Campania reporting the highest emotivity, particularly compared to Veneto (p = 0.000), Marche (p = 0.001), and Tuscany (p = 0.014). For Factor 6, convivial habits tied to vegetable consumption are notably stronger in Lombardy, Tuscany, and Emilia-Romagna than in Lazio, where appreciation for communal vegetable consumption is lower. Significant differences are observed between Lazio and Lombardy (p = 0.005), Lazio and Tuscany (p = 0.015), and Lazio and Emilia-Romagna (p = 0.037).

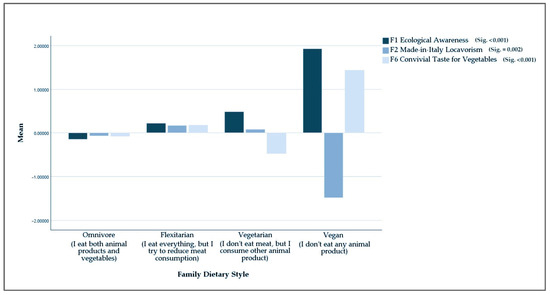

When crossed with dietary styles, only F1, F2, and F6 show statistical significance (again via the Kruskal–Wallis test). As shown in Figure 7, vegan families score high in ecological awareness and convivial taste for vegetables, while Made-in-Italy locavorism is notably low. Ecological awareness also remains positive, though less pronounced, in vegetarian families.

Figure 7.

Factors reflecting families’ “food cultures” crossed by families’ dietary styles. (Figure generated using IBM SPSS Statistics, version 29.0.0.)

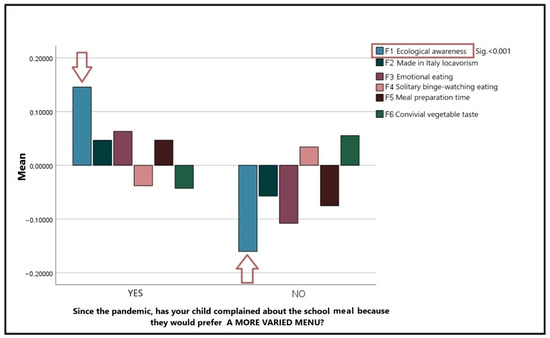

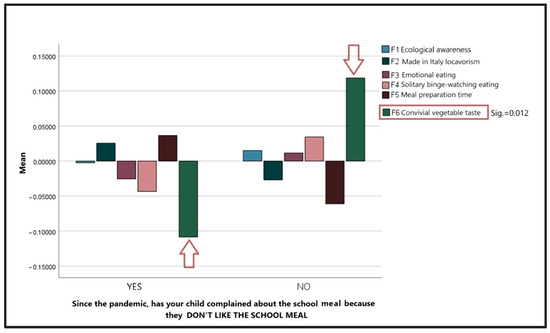

Figure 8 shows that when family ecological awareness is high, children tend to complain, preferring a more varied school menu.

Figure 8.

Correlation between family’s ecological awareness (F1) and children’s requests for a more varied school meal (as reported by parents). (Figure generated using IBM SPSS Statistics, version 29.0.0.)

Figure 9 shows that when families regularly consume vegetables at home, children tend to appreciate school meals more.

Figure 9.

Correlation between families’ convivial taste for vegetables (F6) and children’s appreciation of school meals (as reported by parents). (Figure generated using IBM SPSS Statistics, version 29.0.0.)

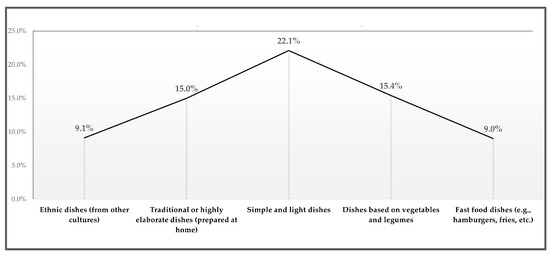

About 44% of respondents report changes in children’s food quality, particularly with new types of foods. As shown in Figure 10, 22% of families introduced simple and light dishes, while 15% added both traditional and elaborate dishes, as well as vegetable- and legume-based dishes, with a slight preference for the latter. Fast food and ethnic dishes were each introduced by 9% of respondents. The line chart in Figure 10 forms a mountain shape, with simple and light dishes at the peak and a range of tastes—from ethnic to traditional, fast food to vegetable-based—distributed along the slopes.

Figure 10.

Types of food introduced or added to children’s diets during lockdown: a “mountain” of opportunities.

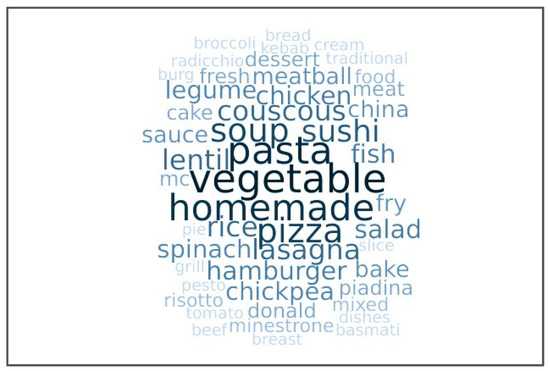

We asked families to list new foods introduced to their children’s meals during lockdown. As shown in Figure 11, in addition to homemade pasta and pizza, vegetables and ethnic foods like couscous, sushi, and Chinese dishes were prevalent, confirming the “mountain” depicted in Figure 10.

Figure 11.

New foods introduced by families during the lockdown (figure generated using Qualtrics © 2020, Version 2020).

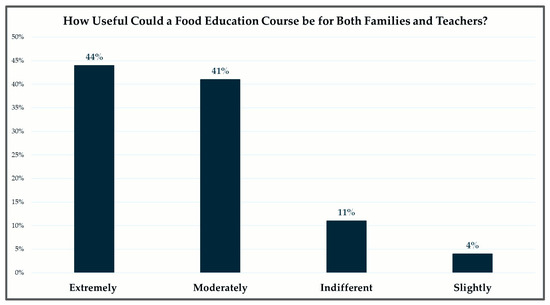

At the end of the investigation, we asked families to rate the importance of a food education course for parents and teachers. As shown in Figure 12, 85% expressed support, while only 15% were indifferent or opposed.

Figure 12.

Family-perceived utility of food education for families and teachers.

Correlating this feedback with the six food-related components, we found a significant positive correlation (p = 0.012) between the first component, FAC1 (family’s ecological awareness), and the importance attributed to food education.

4. Discussion of Results and Hypotheses

4.1. Contradictions and Opportunities in Children’s Family Food Cultures During the Pandemic

Despite the non-probabilistic sampling procedure, the sample’s characteristics reflect Italy’s social context at the time of the research, including its inherent contradictions and imbalances. The greater representation from central and northern regions highlights regional disparities in school canteen access. According to Save the Children [44], only 55.2% of Italian primary school students have access to school meals, ranging from 96% in Florence (Tuscany) to 6–8% in major Sicilian cities. Access is highest in the north and center (Liguria 86.5%, Tuscany 82.7%, Piedmont 79.4%) and lowest in five southern regions (Sicily 11.2%, Apulia 16.9%, Campania 21.3%, Calabria 25.3%, Molise 27.4%). The high number of female respondents highlights the persistent gender divide in caregiving within Italian households, where, according to the European Index of Gender Equality, 72% of women are still responsible for daily cooking and/or housework [45]. Respondents’ average age of 46 suggests late parenthood, likely between ages 36 and 41, significantly later than Italy’s already high average first childbirth age of 32.4, which substantially exceeds the EU average of 29.4 years [46]. Regarding economic status, our sample, consisting mainly of cohabiting two-partner households with personal incomes primarily concentrated (31%) between EUR 15,000 and EUR 28,000 gross annually, broadly aligns with the national profile of families using school catering services for their children. According to the Seventh Cittadinanzattiva Survey on School Catering, the “average family” using these services consists of three members with an annual gross income of EUR 44,200 [47]. Our slight upward deviation in income and family size is due to the concentration of respondents in Lombardy (northwest) and Veneto and Emilia-Romagna (northeast), which, excluding autonomous regions and provinces, have the highest average personal incomes and typically two minor children per household [48]. Household weekly food expenditure, most commonly ranging between EUR 101 and EUR 150, aligns with national trends, which indicate an average monthly household food expenditure of EUR 526.00, equivalent to a weekly range of approximately EUR 105.00 to EUR 132.00 [49].

Regarding attention to food, our family feeders—primarily women with regular jobs who also manage family cooking—adopt a convenient dietary style, prioritizing time-saving and easy meal preparation, typically spending no more than an hour per day. In line with the Italian trend reported by Eurispes [50] (p. 548), according to which over 93% are non-vegetarians, less than 5% of our surveyed families identify as vegetarian or vegan, and only 38% of respondents, slightly more than one in three, meet the recommended daily intake of vegetables. This is notably below the FAO’s [51] and Italian Dietary Guidelines’ recommendation of at least five portions of vegetables and fruits per day [52], reflecting a continued gap in ensuring a healthy diet for children.

4.2. Hypotheses 1 to 3: The Disruptive Effect of the Pandemic on Family Routine Influenced Children’s Eating Patterns

The increased time spent cooking with their children during the lockdown for 39% of respondents, particularly among the 74% working remotely, demonstrates the disruptive impact of lockdowns [1,2] in reshaping daily routines and food consumption patterns [6,7,8]. This led to more shared meals, a rediscovery of the kitchen as a space for socialization [5], and greater attention to food [4,8], breaking the predominantly convenient eating style among our respondents. However, these changes had a dual effect, also resulting in children’s increased daily intake, especially when unsupervised, often while binge-watching, out of boredom, or due to anxiety. This supports the hypothesis that the pandemic and extended closures disrupted domestic food routines and heightened eating disorder risk factors in youngsters [3,9,11,13].

Our findings also support the hypothesis that children conform to their family’s eating habits [22,23,24,25,26], as shown by the high appreciation for vegetables in those few families where parents are vegan (1%) or vegetarian (3%) (Figure 2).

The introduction of new foods, primarily simple and light dishes based on vegetables, legumes, and “ethnic” dishes (Figure 10 and Figure 11), aligns with the literature [53], which notes the increased popularity of plant-based meals during the lockdown, driven by the success of food delivery services offering options like salads and basmati rice.

Multivariate analysis (MCA and EFA) reveals key elements of families’ and children’s eating profiles during lockdowns, namely: (a) polarization in Italian consumers’ value patterns influencing food choices, (b) fragmentation and neuroticization of children’s eating habits, and (c) the rediscovery of the kitchen as a space for practicing and socializing around new, healthier foods.

Factors 1 (“ecological awareness”) and 2 (“Made-in-Italy locavorism”) predominantly characterize our families, revealing contradictory consumer claims since the pandemic, driven by uncertainty and a demand for protection. Alongside the ecological concerns of Factor 1, Factor 2 highlights identity-based food preferences, hinting at an early form of gastronationalism, now prominent among Italian consumers [54,55,56]. Factors 3 and 4 reveal disruptions in children’s eating patterns, leading to altered food intake habits. Increased time at home, often in front of screens and confined to rooms, turned meals into solitary, deregulated, or fragmented practices, affecting weight variations [11,13] and contributing to the neuroticization of meals. These components offer insight into the rise in eating disorders during the pandemic [15,16,17,18].

Factors 5 and 6 highlight the changing social dynamics of meal preparation and eating during extended home confinement, revealing a renewed appreciation of the kitchen as a space for family socialization and food awareness [5]. Factor 5, with a Cronbach Alpha of 0.705, reflects the increased time spent cooking together as a key element in the pandemic family foodscape. Although weaker (Cronbach Alpha 0.406), Factor 6 supports Hypothesis 3: as children conform to family eating habits, regularly shared, healthy, and vegetable-based meals enhance their appreciation of vegetables and school meals. In this sense, the pandemic opened a “window of opportunities” [4], as shown in Factors 1, 2, 5, and 6 and depicted in Figure 10, where the “window” takes the shape of a mountain, with healthy and unhealthy food choices equally placed on the slopes, peaking with simple, light dishes.

Factors 1, 2, and 6 suggest that turning lockdown-induced changes into a sustainable dietary style depends on pre-existing family food culture, as shown in Figure 7, where stronger ecological awareness and vegetable conviviality prevail among vegan families. Figure 8 and Figure 9 confirm our hypotheses that family food habits shape children’s attitudes toward school meals. Where family ecological awareness is strong, children demand higher quality and variety in school food; similarly, healthy dietary habits at home enhance children’s overall appreciation of school meals, reinforcing the study’s guiding idea that a sustainable school canteen starts at home.

4.3. Hypothesis 4: Connections Between Dietary Habits at Home and Food Waste in the Canteen

The key dimensions emerging from our data—polarization of family food values between ecological awareness and identity claims, fragmentation of children’s eating patterns during lockdowns, and increased family time spent cooking a variety of dishes, including more or fewer vegetables depending on parents’ dietary styles—affect not only family food cultures but also children’s school food culture. Children’s attitudes toward school meals, influenced by pre-existing family food habits (as shown in Figure 8 and Figure 9), may become a critical factor in the systemic dynamics of food waste in the canteen, either contributing to or preventing leftovers in the school dish. Food waste in school canteens is a long-standing “wicked” problem [57], which became especially challenging during the pandemic but existed prior due to factors spanning from home to school. The main causes include service (meal duration, canteen environment, serving methods, portioning), food (acceptability, palatability), and the eater (satiety, preferences, eating habits) [58], corresponding to three interdependent levels: operational (service management, portioning), behavioral (taste, preferences, family habits, satiety), and contextual (presentation, accessibility, time, comfort) [59,60].

The part of this research directly involving 1092 children—published elsewhere [33]—confirmed that contextual and operational mismatches (e.g., service time, duration, space, management, presentation, portioning) between home and school meals led to unappreciated meal times and increased food waste, especially among children attending the canteen only 1–2 times a week. Notably, 78% of the surveyed children used to leave food on the plate [33] (p. 7). The critical triad of leftover food—vegetables (57%), legumes (59%), and fish (54%)—is largely due to children’s unfamiliarity with and lack of preference for these foods [33] (pp. 6–7), as also confirmed by our data in Figure 2. Dimensions intersect when waste is driven by food neophobia, i.e., the rejection of new foods, which is heightened in uncomfortable contexts, increasing children’s mistrust of unfamiliar foods. Conversely, relaxed settings encourage a willingness to try new foods, especially when supported by a family habitus open to experimentation.

Rejection or acceptance of school food correlates with pupils’ ages: younger children in grades 1 and 2 waste less food, while older children in grades 3, 4, and 5 develop personal preferences—consistent with data from the focus groups Section 3.1.1—which often lead to dissatisfaction and increased waste. Grade 3, serving as a transitional period, presents an ideal opportunity to introduce food education involving families. As also highlighted in Q30 (Figure 11), a partnership between schools and families is crucial for reducing mismatches between home kitchens and school canteens, promoting a cultural paradigm that emphasizes the educational role of meals, stimulates curiosity, and encourages the acceptance of diverse foods, thereby reducing waste.

4.4. Hypothesis 4: Gaps in Italy’s Sustainable Food Procurement Standards and Inconsistencies in the Minimum Environmental Criteria

In the view of the European Commissioner for the Green Deal, canteens are expected to contribute to education and nutrition, combat poverty, and reduce waste [61]. However, it remains questionable whether these goals are prioritized and adequately substantiated by current legislation in accordance with a systematic scientific methodology.

The findings of this study (see Section 3.2.3), in line with the literature [25,30], highlight the importance of establishing a coherent relationship between children’s dietary habits at home, including by engaging families, and the food provided in school canteens, particularly to promote nutritional well-being and reduce food waste. Unfortunately, no such foundation is evident in the CAM (Criteri Ambientali Minimi in Italian, Minimum Environmental Criteria in English), which set mandatory procurement regulations for all primary school canteens and was last renewed in Italy on 10 March 2020 [28]. Although, according to Article 34 of the National Contracts Code, approved by Legislative Decree 50/2016, these criteria are subject to periodic updates, the last update occurred in March 2020, at the onset of the pandemic, and no further enhancements have been made, despite the documented impact of COVID-19 on canteens [20,21,29].

The CAM’s lack of integration with home habits, education, and school canteens is not its only theoretical shortcoming. Of particular relevance to this study is the CAM’s overwhelming focus on supply chains, with little emphasis on involving families in selecting suppliers and ingredients that are well accepted, thereby minimizing food waste—despite this being highlighted as one of the primary objectives in several sections of the accompanying technical report [62] (pp. 13–14, 19–20), a document that is not without contradictions. For instance, the CAM explicitly promote organic food by setting percentage requirements in procurement, even though it acknowledges that conventional food is equally safe, provided it comes from farming models that adhere to regulations [62] (p. 5). It mandates sourcing a minimum of 50% of fruit, 100% of eggs and dairy, and 50% of beef from organic producers [62], (Annex 1, p. 36), although the accompanying report states that in 2017, 76% of animal products, 77% of processed food, 64% of vegetables, and 36% of fruit in Italy were classified as “residue 0” [62], (p. 18), indicating concentrations below the measurable threshold and well within safety limits [63]. In contradiction to its earlier recommendations, the CAM, just a few pages later, citing “the limited market availability of organic products”, allow the replacement of organic quotas with quotas of “otherwise qualified foods”, such as PDO, PGI, or “mountain products” [62] (pp. 27–28, 34) for collective catering including at nurseries, preschools, and primary and secondary schools [62] (Annex 1, p. 36), a measure that seemingly lacks coherence and effectiveness. The CAM legislator prioritizes selecting appropriate supply chains for raw materials over ensuring that children receive optimal nourishment and genuinely enjoy their meals.

In its commendable intent to improve nutritional quality and reduce waste, the CAM promote low-cost protein consumption through legume-based recipes, also “introducing local and lesser-known species and varieties” [62] (p. 25). However, with specific regard to waste-reducing dishes served in schools, while they mention “collaboration with stakeholders possessing specific expertise […] to address root causes” [62] (p. 20), they entirely overlook dialogue with families, who are not even listed among the stakeholders [62] (Annex 3, p. 45). The introduction of innovative recipes with unfamiliar ingredients or formats—e.g., “one-dish meals (pasta or rice) with meat or fish ragù, legumes, baked with vegetables and cheese, etc.” [62] (p. 22)—combined with evidence that children often leave their plates unfinished, especially one-dish meals (see Section 3.1.2), mostly vegetables or costly, nutritionally important fish (see Section 4.3), contradicts the goal of reducing food waste and exacerbates malnutrition.

An analysis of the CAM, based on the results of their full implementation, reveals a significant disconnect between the legislator’s objectives and the actions required by the regulations. Although highly prescriptive, the legislation fails to adequately incorporate scientific knowledge, including the pedagogical aspects inherent in a process involving children and the two primary educational agencies: school and family. Its top-down approach neglects the need for phased implementation involving all stakeholders, as recommended globally [64]. It also overlooks economic constraints, placing the financial burden of these inconsistencies entirely on school catering entities, including municipalities, educational institutions, and catering operators. As a result, outcomes are unsatisfactory in terms of both children’s and families’ satisfaction, as well as food waste reduction, while costs remain prohibitively high.

In line with the results of this research, legislation should address the interconnected factors—household eating patterns, parents’ food-related awareness and lifestyles, and children’s attitudes toward school meals and healthier menus—and integrate them into its policies to effectively promote more sustainable canteens, healthier lifestyles, and waste reduction.

5. Conclusions

The research shows how the pandemic and extended lockdowns disrupted family food routines, affecting children’s relationship with food and increasing eating disorders, which impacted their appreciation of school meals. However, when surveyed, families revealed that this disruption brought not only risks but also a “mountain of opportunities” to adopt healthier eating habits. The study confirmed the overarching hypothesis that family food cultures and habits—both pre-existing and developed during the pandemic—are significantly correlated with children’s attitudes toward school meals. Data show that where family ecological awareness is strong, children become more demanding diners, seeking higher quality and variety in school food. Similarly, healthy, vegetable-based family diets enhance children’s appreciation of school meals, reinforcing the idea that a sustainable school canteen begins in the home kitchen. The study also highlights that children’s appreciation of school meals influences unfinished dishes—especially vegetables—and food waste. Given the influence of family on children’s tastes, promoting a cultural paradigm that emphasizes the educational role of meals for both parents and children, stimulates curiosity, and encourages acceptance of diverse foods could significantly reduce canteen waste. Lastly, understanding how children’s tastes are shaped and the nature of family habits provides additional perspectives for gaining insight into the gaps in food public procurement policies, with their contradictions, inconsistent reliance on scientific bases, and their disconnection from both family and canteen realities, as well as from the widely promoted sustainability goals—both nutritional and economic. Ultimately, the study suggests that these goals are likely achievable only if catering services and policies are rethought, reinforcing their reliance on scientific evidence, along with integrating nutrition education into school curricula and involving families in menu development.

6. Research Limitations

The main limitation of this research was the difficulty in accessing schools and securing the collaboration of teachers, children, and families during the health emergency and its immediate aftermath, which significantly extended the timeline and led to participant dropouts. This constraint necessitated the use of a non-probabilistic convenience sample and, despite efforts to mitigate bias and the observed alignment of our data with national trends, prevented the adjustment or supplementation of the sample with random sampling. Additionally, the limited availability of schools and participants during the emergency may have skewed the sample, favoring parents with higher educational backgrounds. Conducting focus groups online may have further reduced the effectiveness of participant interaction. Data collection occurred during or after successive waves of the COVID-19 pandemic, with a significant time gap between the initial focus groups and the survey’s conclusion, potentially influencing the findings.

Author Contributions

M.G.O.: conceptualization, methodology, software, validation, formal analysis, investigation, data curation, writing—original draft preparation, writing—review and editing, visualization. M.A.F.: conceptualization, formal analysis, resources, writing—original draft preparation, supervision, project administration, funding acquisition. P.C.: conceptualization, methodology, validation, formal analysis, investigation, writing—original draft preparation. C.F.: software, validation, formal analysis, investigation, data curation, writing—original draft preparation. F.F.: conceptualization, formal analysis, writing—original draft preparation. Regarding paragraph attributions, M.G.O. wrote Section 1, Section 2, Section 2.2, Section 2.4, Section 3.2.1, Section 3.2.3, Section 4.1 and Section 4.2; P.C. wrote Section 2.1, Section 3.1 and Section 3.1.1, Section 3.1.2, Section 3.1.3, Section 3.1.4 and Section 3.1.5; C.F. wrote Section 2.3 and Section 3.2.2; M.A.F. wrote Section 4.4; F.F. wrote Section 4.3. All authors contributed to the conclusions. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

The research project “Nourishing School” (grant number 2021-0575) was funded by Associazione Filiera Futura, Fondazione Cariplo, Fondazione Cassa di Risparmio di Bolzano, Fondazione Cassa di Risparmio di Cuneo, Fondazione Perugia, Fondazione Cassa di Risparmio di Torino, Fondazione CON IL SUD, Fondazione Cassa di Risparmio di Biella, Fondazione Cassa di Risparmio di Gorizia, Fondazione Cassa di Risparmio di Jesi, Fondazione Carivit, and Fondazione Cassa di Risparmio di Volterra.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki, and, as it involved humans, was approved by the Ethical Committee of the University of Gastronomic Sciences (Ethical Committee Proceeding N. 2022.03).

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was integrated in the survey and obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement

The data presented in this study are available upon request from the corresponding author, as they originate from privately funded research.

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank Annalisa Sivieri, from the Company Projects and Innovation of the University of Gastronomic Sciences, for her technical and administrative support. We also extend our gratitude to the school principals for allowing the schools to participate in the research and for facilitating contact with the children’s families.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest. The funders had no role in the design of the study; in the collection, analyses, or interpretation of data; in the writing of the manuscript; or in the decision to publish the results.

References

- Vandenberghe, F.; Véran, J.-F. The Pandemic as a Global Social Total Fact. In Pandemics, Politics, and Society; Delanty, G., Ed.; Walter de Gruyter GmbH: Berlin, Germany, 2021; pp. 171–190. [Google Scholar]

- Eftimov, T.; Popovski, G.; Petković, M.; Seljak, B.K.; Kocev, D. COVID-19 pandemic changes the food consumption patterns. Trends Food Sci. Technol. 2020, 104, 268–272. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gao, Y.; Bagheri, N.; Furuya-Kanamori, L. Has the COVID-19 pandemic lockdown worsened eating disorders symptoms among patients with eating disorders? A systematic review. J. Public Health 2022, 30, 2743–2752. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Forno, F.; Laamanen, M.; Wahlen, S. (Un-)sustainable transformations: Everyday food practices in Italy during COVID-19. Sustain. Sci. Pr. Policy 2022, 18, 201–214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Onorati, M.G.; Corvo, P.; Durelli, P.; Fontefrancesco, M.F. The kitchen rediscovered: The effects of the lockdown on domestic food consumption and dietary patterns in early pandemic Italy. Food Cult. Soc. 2023, 1–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Micalizzi, L.; Zambrotta, N.S.; Bernstein, M.H. Stockpiling in the time of COVID-19. Br. J. Health Psychol. 2021, 26, 535–543. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Scacchi, A.; Catozzi, D.; Boietti, E.; Bert, F.; Siliquini, R. COVID-19 Lockdown and Self-Perceived Changes of Food Choice, Waste, Impulse Buying and Their Determinants in Italy: QuarantEat, a Cross-Sectional Study. Foods 2021, 10, 306. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Di Renzo, L.; Gualtieri, P.; Pivari, F.; Soldati, L.; Attinà, A.; Cinelli, G.; Leggeri, C.; Caparello, G.; Barrea, L.; Scerbo, F.; et al. Eating habits and lifestyle changes during COVID-19 lockdown: An Italian survey. J. Transl. Med. 2020, 18, 229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Au, L.E.; Gurzo, K.; Gosliner, W.; Webb, K.L.; Crawford, P.B.; Ritchie, L.D. Eating School Meals Daily Is Associated with Healthier Dietary Intakes: The Healthy Communities Study. J. Acad. Nutr. Diet. 2018, 118, 1474–1481. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Decataldo, A.; Fiore, B. Is eating in the school canteen better to fight overweight? A sociological observational study on nutrition in Italian children. Child. Youth Serv. Rev. 2018, 94, 246–256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Franckle, R.; Adler, R.; Davison, K. Accelerated Weight Gain Among Children During Summer Versus School Year and Related Racial/Ethnic Disparities: A Systematic Review. Prev. Chronic Dis. 2014, 11, 130355. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, J.; Barnidge, E.; Kim, Y. Children Receiving Free or Reduced-Price School Lunch Have Higher Food Insufficiency Rates in Summer. J. Nutr. 2015, 145, 2161–2168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, Y.C.; Vine, S.; Hsiao, A.; Rundle, A.; Goldsmith, J. Weight-Related Behaviors When Children Are in School Versus on Summer Breaks: Does Income Matter? J. Sch. Health 2015, 85, 458–466. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- von Hippel, P.T.; Workman, J. From Kindergarten Through Second Grade, U.S. Children’s Obesity Prevalence Grows Only During Summer Vacations. Obesity 2016, 24, 2296–2300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Solmi, F.; Downs, J.L.; E Nicholls, D. COVID-19 and eating disorders in young people. Lancet Child Adolesc. Health 2021, 5, 316–318. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramalho, S.M.; Trovisqueira, A.; de Lourdes, M.; Gonçalves, S.; Ribeiro, I.; Vaz, A.R.; Machado, P.P.P.; Conceição, E. The impact of COVID-19 lockdown on disordered eating behaviors: The mediation role of psychological distress. Eat. Weight. Disord. Stud. Anorex. Bulim. Obes. 2022, 27, 179–188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Devoe, D.J.; Han, A.; Anderson, A.; Katzman, D.K.; Patten, S.B.; Soumbasis, A.; Flanagan, J.; Paslakis, G.; Vyver, E.; Marcoux, G.; et al. The impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on eating disorders: A systematic review. Int. J. Eat. Disord. 2023, 56, 5–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- European Parliament. 15.12.2021 Parliamentary Question—P-005594/2021. Eating Disorders: The Situation in the European Union. Available online: https://www.europarl.europa.eu/doceo/document/P-9-2021-005594_EN.html (accessed on 2 November 2024).

- ISTAT. Rapporto Annuale 2021 La Situazione del Paese; ISTAT: Roma, Italy, 2021.

- Pagliarino, E. State school catering in Italy during the COVID-19 pandemic: A qualitative study. Front. Sustain. Food Syst. 2024, 8, 1387100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Comune di Milano. 2022. “La Qualità Percepita del Servizio di Refezione Scolastica Anno 2021”. Commissione Consiliare Congiunta Educazione e Partecipate 16 Giugno 2022. Available online: https://comune-milano.img.musvc2.net/static/105044/assets/2/2022_06_16_Commissione%20Congiunta_La%20qualit%C3%A0%20percepita%20del%20servizio%20di%20refezione%20scolastica.pdf (accessed on 3 November 2024).

- Piaget, J. Lo Sviluppo Mentale del Bambino, orig. First ed. 1964; Einaudi: Torino, Italy, 1967. [Google Scholar]

- Coleman, J. La Natura dell’Adolescenza, orig. first ed. 1980; Il Mulino: Bologna, Italy, 1983. [Google Scholar]

- Kolberg, L. The Meaning and Measurement of Moral Development; Heinz Werner Institute: Clark University: Worcester, MA, USA, 1981. [Google Scholar]

- Ryan, D.; Holmes, M.; Ensaff, H. Adolescents’ dietary behaviour: The interplay between home and school food environments. Appetite 2022, 175, 106056. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hennchen, B.; Schafer, M. Healthy, Inclusive and Sustainable Catering in Secondary Schools—An Analysis of a Transformation Process with Multiple Tensions. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2024, 21, 370. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- European Commission. 2020. From Farm to Fork Strategy. Available online: https://food.ec.europa.eu/system/files/2020-05/f2f_action-plan_2020_strategy-info_en.pdf (accessed on 2 April 2024).

- DM 65/2020. Available online: https://gpp.mase.gov.it/sites/default/files/2022-05/cam_ristorazione.pdf (accessed on 2 September 2024).

- Pagliarino, E.; Santanera, E.; Falavigna, G. Opportunities for and Limits to Cooperation between School and Families in Sustainable Public Food Procurement. Sustainability 2021, 13, 8808. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Galli, F.; Brunori, G.; Di Iacovo, F.; Innocenti, S. Co-Producing Sustainability: Involving Parents and Civil Society in the Governance of School Meal Services. A Case Study from Pisa; Italy. Sustainability 2014, 6, 1643–1666. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Available online: https://www.cirfood.com/ (accessed on 29 August 2024).

- Available online: https://www.comune.milano.it/aree-tematiche/food_policy (accessed on 29 August 2024).

- Piochi, M.; Franceschini, C.; Fassio, F.; Torri, L. A large-scale investigation of eating behaviors and meal perceptions in Italian primary school cafeterias: The relationship between emotions, meal perception, and food waste. Food Qual. Prefer. 2025, 123, 105333. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morgan, D.L. Focus Groups as Qualitative Research; Sage: London, UK, 1988. [Google Scholar]

- Wilkinson, S. Focus groups. In Qualitative Psychology: A Practical Guide to Research Methods; Smith, J.A., Ed.; Sage: London, UK, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Turner, D.P. Sampling methods in research design. Headache J. Head Face Pain 2020, 60, 8–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Golzar, J.; Noor, S.; Tajik, O. Convenience Sampling. Int. J. Educ. Lang. Stud. 2022, 1, 72–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berndt, A.E. Sampling methods. J. Hum. Lact. 2020, 36, 224–226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Izenman, A.J. Modern Multivariate Statistical Techiniques. Regression, Classification, and Manifold Learning; Springer: New York, NY, USA, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Abdi, H.; Williams, L.J. Principal Component Analysis. WIREs Comp. Stat. 2010, 2, 433–459. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- R Core Team. R: A Language and Environment for Statistical Computing; R Foundation for Statistical Computing: Vienna, Austria, 2021; Available online: https://www.R-project.org/ (accessed on 2 July 2024).

- Lê, S.; Josse, J.; Husson, F. FactoMineR: An R Package for Multivariate Analysis. J. Stat. Softw. 2008, 25, 1–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kassambara, A.; Mundt, F. factoextra: Extract and Visualize the Results of Multivariate Data Analyses. R Package Version 1.0.7. 2020. Available online: https://CRAN.R-project.org/package=factoextra (accessed on 2 July 2024).

- Save the Children Italia. (10 June 2024). Mense Scolastiche: Un Servizio Essenziale per Ridurre le Disuguaglianze. Available online: https://www.savethechildren.it/cosa-facciamo/pubblicazioni/mense-scolastiche-un-servizio-essenziale-per-ridurre-le-disuguaglianze (accessed on 25 July 2024).

- EIGE. European Gender Equality Index. 2023. Available online: https://eige.europa.eu/gender-equality-index/2023/domain/time/IT (accessed on 4 March 2024).

- Eurostat. Mean Age of Women at Childbirth and at Birth of First Child. 2022. Available online: https://ec.europa.eu/eurostat/databrowser/view/tps00017/default/table?lang=en&category=t_demo.t_demo_fer (accessed on 4 March 2024).

- Cittadinanzattiva. VII indagine. Tariffe Mense Scolastiche e Investimenti PNRR. Report 2023/24. 2023. Available online: https://www.cittadinanzattiva.it/rapporti-osservatori-e-indagini/168-vii-indagine-mense-2024/download.html (accessed on 11 November 2024).

- ISTAT. Economic Conditions of Families and Inequalities. 2022. Available online: http://dati.istat.it/Index.aspx?QueryId=22919 (accessed on 11 November 2024).

- ISTAT. Le Spese per i Consumi Delle Famiglie. Anno 2023. 2023. Available online: https://www.istat.it/wp-content/uploads/2024/10/REPORT_Spese-per-consumi_2023_rev.pdf (accessed on 11 November 2024).

- Eurispes. 34° Rapporto Italia; Rubbettino: Soveria Mannelli, Italy, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- FAO. Food-Based Dietary Guidelines. Available online: https://www.fao.org/nutrition/nutrition-education/food-dietary-guidelines/en/ (accessed on 6 June 2024).

- CREA. Linee Guida per una Sana Alimentazione (2018). Roma, Ed. CREA. 2019. Available online: https://www.salute.gov.it/imgs/C_17_pubblicazioni_2915_allegato.pdf (accessed on 6 June 2024).

- Poelman, M.P.; Gillebaart, M.; Schlinkert, C.; Dijkstra, S.C.; Derksen, E.; Mensink, F.; Hermans, R.C.; Aardening, P.; de Ridder, D.; de Vet, E. Eating behavior and food purchases during the COVID-19 lockdown: A cross-sectional study among adults in the Netherlands. Appetite 2021, 157, 105002. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- DeSoucey, M. Gastronationalism: Food Traditions and Authenticity Politics in the European Union. Am. Sociol. Rev. 2010, 75, 432–455. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fino, M.A.; Cecconi, A.C. Gastronazionalismo; People: Busto Arsizio, Italy, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Onorati, M.G.; d’Ovidio, F.D. Sustainable eating in the “new normal” Italy:Ecological food habitus between biospheric values and de-globalizing gastronationalism. Food Cult. Soc. 2022, 26, 1134–1153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rittel, H.W.; Webber, M.M. Dilemmas in a general theory of planning. Policy Sci. 1973, 4, 155–169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blondin, S.A.; Djang, H.C.; Metayer, N.; Anzman-Frasca, S.; Economos, C.D. Un’indagine qualitativa sullo spreco di cibo in un programma di colazione scolastica universale e gratuita. Public Health Nutr. 2015, 18, 1565–1577. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cordingley, P. Il contributo della ricerca all’apprendimento e allo sviluppo professionale degli insegnanti. Oxf. Rev. Educ. 2015, 41, 234–252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boschini, M.; Falasconi, L.; Giordano, C.; Alboni, F. Lo spreco alimentare nelle mense scolastiche: Una metodologia di riferimento per studi su larga scala. J. Clean. Prod. 2018, 182, 1024–1032. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- See Vice President of the European Commission Frans Timmermans’ talk at the University of Gastronomic Sciences during the Inauguration of the Academic Year on March 17. 2023. Available online: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=4BpNaH9tHbA&t=1682s (accessed on 2 July 2024).

- Relazione Accompagnamento CAM Servizio di Ristorazione Collettiva e Fornitura Derrate Alimentari (DM n.65/2020). Available online: https://gpp.mase.gov.it/sites/default/files/2022-05/CAM%20Ristorazione%20Relazione%20accompagnamento%20aprile%202022_0.pdf (accessed on 2 July 2024).

- Djekic, I.; Smigic, N.; Udovicki, B.; Tomic, N. “Zero Residue” Concept—Implementation and Certification Challenges. Standards 2023, 3, 177–186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- See the OECD-COLEAD “The Fruits and Vegetables industry” Series, Particularly Session 7. Available online: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=SBsKpLOVQa4 (accessed on 10 November 2024).

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).