1. Introduction and Background

Vietnam is rich in renewable energy sources through the use of solar power and introduced a feed-in tariff (FIT) for electricity generated from solar power in June 2017 [

1]. In particular, the high price of USD 0.935/kWh for the two-year period from June 2017 to June 2019 spurred significant growth in solar power generation (SPG) facilities [

2,

3,

4,

5]. It is reasonable to expect that the expansion of mega-scale SPGs (MEGA-SPGs) will continue in Vietnam, as the country aims to achieve net-zero greenhouse gas emissions by 2050 [

6,

7,

8]. Understanding the acceptance requirements of residents living near MEGA-SPGs is essential for promoting their development in Vietnam [

9]. Many existing research has focused on policy and regulatory barriers [

10,

11,

12], economic [

11,

12,

13,

14,

15], technical [

16,

17,

18,

19,

20], and institutional [

21,

22] barriers to Solar Power Generations in Vietnam. However, there are few studies examining SPGs from the perspective of Vietnamese local residents, such as the study by Nguyen Ngoc et al. (2022), which focused on changes in farmers’ incomes [

23].

Prior research in other contexts, such as that of Susanne et al. (2016), studied the local acceptability requirements for large-scale solar installations in Morocco and identified seven factors that influenced the acceptance of this project, including information about the facility and its impact on the local economy [

24]. In Vietnam, Urakami, A. (2023) conducted interviews with wind and solar stakeholders, highlighting that a weak power grid hinders the deployment of generation facilities [

9]. Xuan et al. (2021) emphasized the necessity of stable legal, economic, and technological foundations for the success of wind and solar power [

2]. Similarly, Eleonora et al. (2020) identified incomplete institutional and technical problems with SPG as significant challenges to the future expansion of SPG in Vietnam [

3]. These technical issues are not unique to Vietnam but are a global concern. Existing studies have emphasized that the primary obstacles to promoting SPG in Vietnam are weak power grids and inadequate institutional support. In addition, many studies have conducted simulations of the optimal placement of SPGs [

25,

26,

27].

However, there is a paucity of research examining the impact of the MEGA-SPG construction from the perspective of local residents in Vietnam. Gaining widespread acceptance from nearby residents is crucial for the development of renewable energy facilities, such as SPGs, which are designed for long-term operation. Previous studies indicated that gaining understanding and support from nearby residents is necessary to facilitate the construction of SPGs [

28,

29,

30]. Without this acceptance, achieving the national goal of carbon neutrality by 2050 will be challenging.

This study aimed to identify the factors influencing the acceptance of MEGA-SPGs by residents living near construction sites. Residents’ quality of life is comprised of various factors [

31,

32]. Therefore, this study also refers to other studies conducted in non-Vietnamese countries to elucidate the opinions of Vietnamese residents regarding the construction of SPGs.

2. Methods

The understanding and agreement of local residents living near facilities are essential for the expansion and sustained operation of MEGA-SPGs. Hence, interviews were conducted with residents living near operational MEGA-SPGs.

2.1. Target Solar Power Generation Facilities

This study examined 89 MEGA-SPGs that commenced operation by the end of June 2019, as reported by the Vietnamese government [

33,

34]. Following the identification of these 89 MEGA-SPGs, Google Maps was utilized to locate those with residential areas within a 1 km radius. Of the 89 facilities that were operational by the end of June 2019,

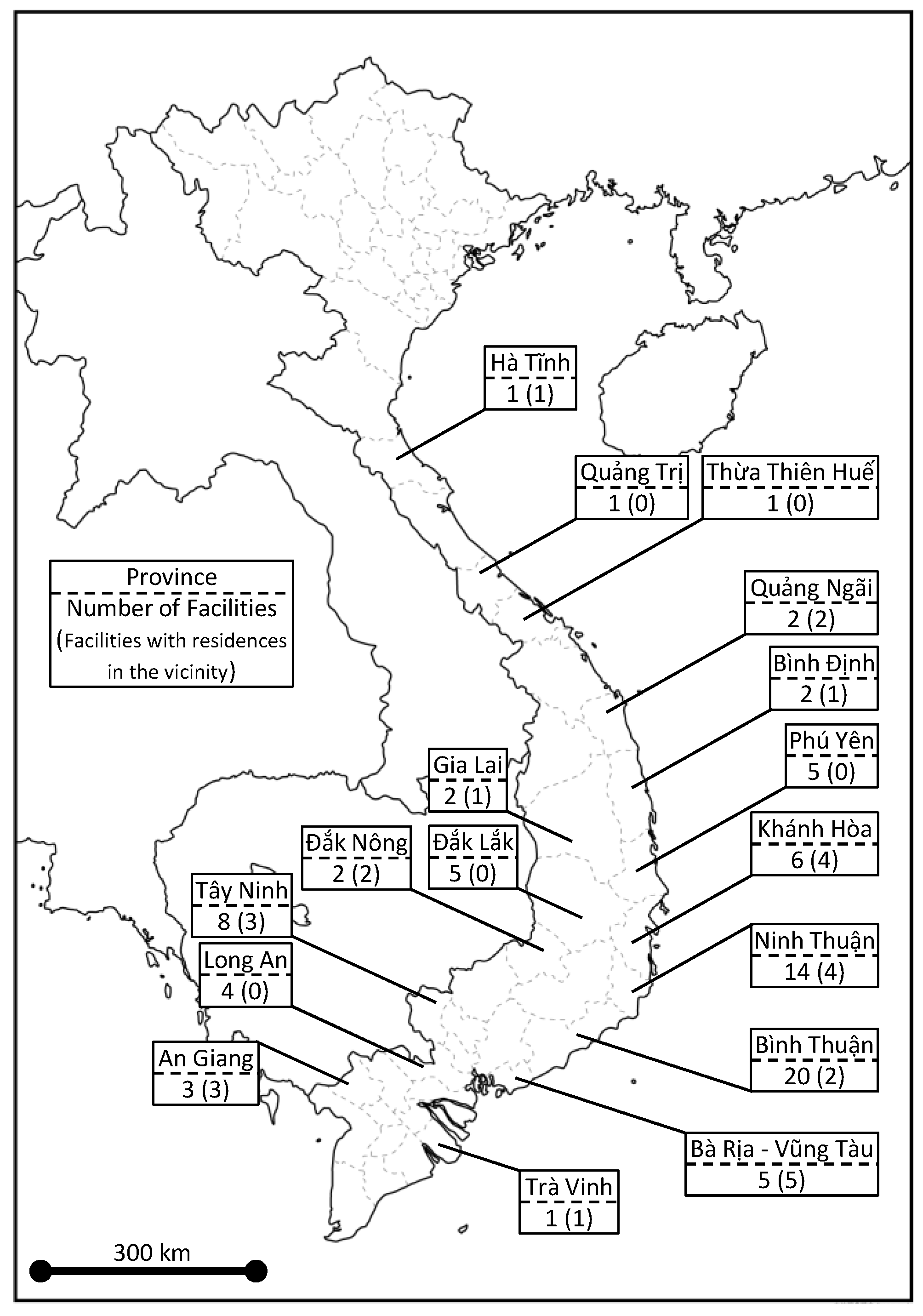

Figure 1 illustrates the 29 MEGA-SPGs that have residences within 1 km.

Focusing on Bà Rịa–Vũng Tàu (BR–VT) province, which has the highest number of MEGA-SPGs with residences in close proximity, this study selected one MEGA-SPG. When selecting the eligible MEGA-SPGs, those with multiple construction periods or adjacent facilities were excluded. Consequently, four of the five BR–VT provincial facilities were eliminated, leaving only one eligible facility.

2.2. Selection of Interviewees

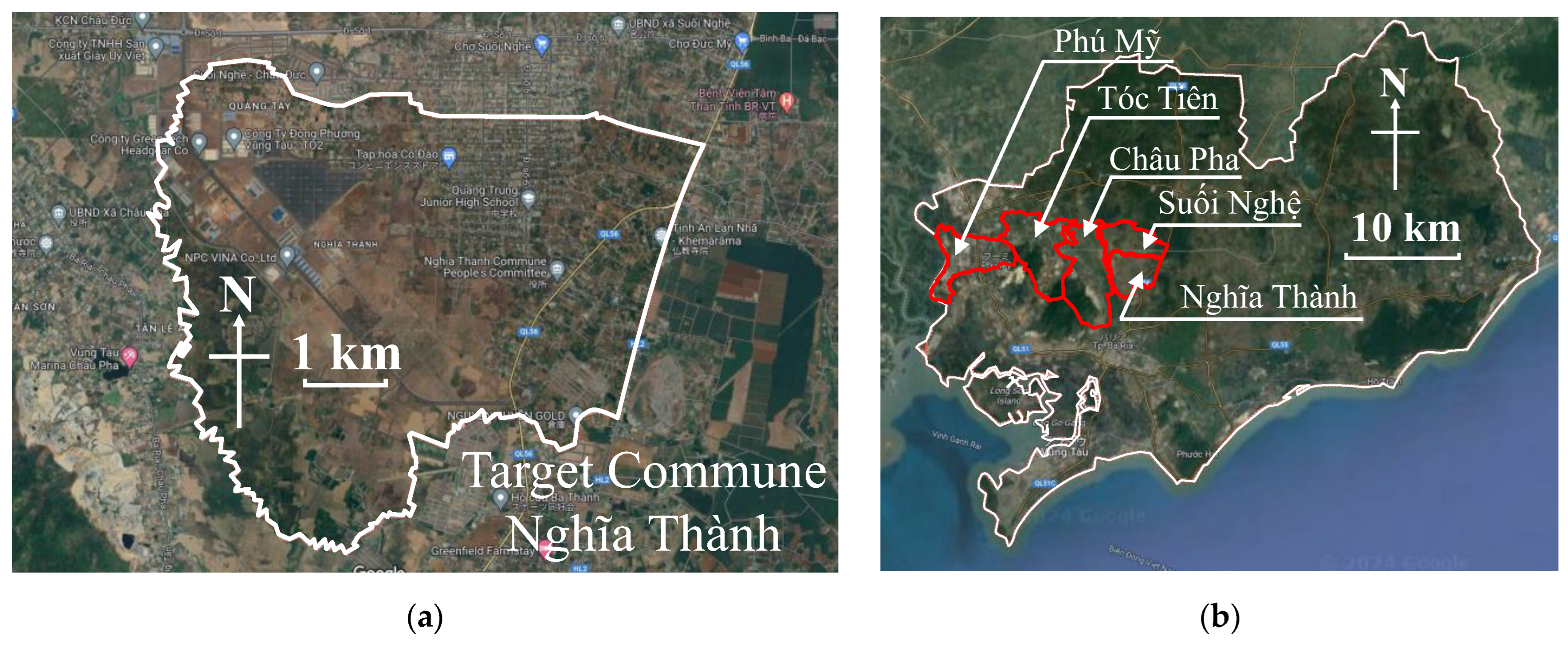

This study focused on the Chau Duc Industrial Park solar power plant (Nhà máy điện mặt trời KCN Châu Đức) in BR–VT province and conducted interviews with residents in the surrounding area.

Figure 2a shows an aerial photograph of the area surrounding the target facility obtained from Google Maps. Considering the influence of the distance from the target facility on acceptance, this study randomly selected and interviewed residents of communes 1, 3, 5, 10, and 20 km away from the target facility. This approach was based on the findings of Susanne et al. (2016), who emphasized the importance of understanding the perspectives of residents within a 20 km radius of the target facility to examine the factors influencing their acceptance of the facility’s construction [

24].

Figure 2b shows the location map of the target communes used for the interviews. Referring to Schreier (2018) and Kumar et al. (2020), we interviewed approximately 25 residents from each target commune [

35,

36].

Table 1 shows the survey dates and number of respondents per target commune.

2.3. Methods of Analyzing Interview Results

The interview survey results were tabulated and discussed, and this was followed by interpretation using a chi-squared test and residual analysis using Microsoft Excel. The Excel function (CHISQ.TEST) was utilized to calculate p-values. The analyses were conducted using the Microsoft Office 2021 software suite. Although the total number of respondents to the interview survey was 123, there were some respondents who did not answer certain questions. Therefore, it should be noted that the number of respondents varies for the analysis of each question.

Interview items were reviewed based on the findings of Susanne et al. (2016), who elucidated community acceptance of large-scale solar energy installations in developing countries [

24]. Specifically, factors such as “Awareness”, “Procedural Justice”, “Trust in Developers and Funders”, “Socioeconomic Impacts”, “Environmental Impacts”, and “Distance from the Project Site” were identified as potentially influencing the promotion of the construction of MEGA-SPGs in Vietnam, and interviews were conducted accordingly. However, despite the shared conditions of being a developing country, Vietnam was excluded in relation to the “Distributive Justice” factor due to its differing national system, making this section inapplicable. The question texts for each item were then reviewed by the authors, and the information presented in the

Supplementary Materials was presented to respondents during the interview survey to gather their feedback.

3. Results and Discussion

This section primarily discusses the interview results, in which significant differences were identified via chi-squared tests and residual analyses. The results of the analyses suggest that proactively disclosing information about construction plans to local residents, as well as ensuring that the residents feel that their opinions are heard and reflected in the construction plans significantly impact residents’ acceptance of facility construction.

3.1. Profile of Respondents

3.1.1. Sex and Age

Table 2 presents the sex and age distributions of respondents by commune type. Approximately 40% of the respondents were women (

n = 47), and approximately 60% were men (

n = 75). Although more respondents were male, the gender distribution was not heavily biased. Furthermore, there was no significant age skew among respondents in any commune, although there was a slight predominance of respondents in their 30s to 50s.

3.1.2. Duration of Residence and Recognition of Target Facility

Table 3 presents the duration of residence and recognition of the target facility among the respondents by commune. More than half of the respondents in all the communes had lived in their areas for over 10 years. Respondents who had resided in their areas for a shorter period (less than three years) exhibited a higher probability of being unaware of the target facility (15/18). Conversely, those who had lived in their areas for more than 10 years were more likely to be aware of the target facility (50/79). These trends were consistent across all communes.

3.1.3. Perceived Sentiments Toward Facility Operation

Table 4 presents the respondents’ levels of agreement with the operation of the target facility, measured on a five-point scale. Respondents from communes close to the target facility were significantly more likely to agree with the operation of the facility. However, a substantial proportion of responses were neutral in all communes.

Based on the above findings, the respondents to this interview survey shared common characteristics across all communes. Most respondents belonged to the working-age generation and were primarily in their 30s and 50s. In addition, many had resided in their areas for a substantial period of 10 years or more, and more than half of the respondents were aware of the target facility. Furthermore, many respondents from various communes exhibited a neutral stance on the operation of the target facility.

3.2. Factors Influencing Local Residents’ Receptivity to the Construction of MEGA-SPGs

3.2.1. Awareness

This section explores the attitudes of local residents toward MEGA-SPG construction plans. Awareness is a critical factor as it shapes residents’ understanding and perception of the project. For MEGA-SPGs, as with other large-scale infrastructure developments, fostering local awareness is essential to ensure informed community acceptance.

Table 5 shows the responses of each commune regarding the degree to which residents were informed in advance by the local municipality about MEGA-SPG construction plans. The most frequent response was an imperfect explanation, except in the communes located furthest from the target facility.

Table 6 illustrates the relationship between the respondents’ level of agreement with the operation of the target facility and the extent to which they were informed of the construction plan in advance. Significantly more responses were observed along the diagonal of the table, meaning that local residents who felt that they were informed about the construction plans in advance tended to have a positive view of the operation of the MEGA-SPG.

However, some local residents who were not informed of the construction plans in advance responded favorably to the operation of the MEGA-SPG. Susanne et al. (2016) noted a similar phenomenon in the Moroccan case [

24]. These results suggest that individuals who lack advance information about construction plans may not object because they are unaware of the information at hand.

Making as little information as possible available to the public may minimize opposition to the construction of a MEGA-SPG. However, the proactive and early disclosure of information, along with the fostering of community harmonization, will be more effective in promoting the successful construction and operation of a MEGA-SPG.

3.2.2. Procedural Justice

This section examines whether MEGA-SPG construction procedures were perceived as fair by local residents. Procedural fairness is essential, as unequal treatment can foster dissatisfaction and a sense of injustice, potentially hindering local support. Transparent and equitable processes are crucial for gaining community acceptance and promoting MEGA-SPG construction successfully.

Table 7 illustrates the relationship between the extent to which the developer of the target facility and the local government sought input from the local community on the construction plans and the extent to which the developer incorporated the local community’s input into the construction plan. The analysis revealed significant relationships between the level of consultation and the perceived adequacy of community input reflections in the construction plan. A lack of consultation is strongly correlated with negative perceptions of input reflection, whereas being fully consulted is correlated with positive perceptions. Neutral engagement leads to neutral perceptions, indicating consistency in moderate views. However, ensuring that full consultation translates into perceived adequacy remains a challenge, thus highlighting the need for further efforts to enhance reflection on community input.

This aligns with previous research which indicates that procedural justice—ensuring fair and meaningful community involvement in decision making—plays a significant role in project acceptance [

37,

38]. Baxter et al. argue that combining procedural justice with distributive fairness is key to achieving broader support [

39]. Community-owned projects, in particular, are often more positively received as they allow residents to engage more actively, giving them both a stake in the process and shared benefits [

40,

41].

3.2.3. Trust in Developers and Funders

This section explores the level of trust local residents have in the developers and funders of MEGA-SPGs. Trust is critical, as residents are unlikely to support initiatives led by governments or companies they perceive as unreliable. Building trust is therefore essential for fostering community acceptance and ensuring project success.

Table 8 shows the commune responses regarding the extent to which information on the developer or funder of the target facility was disclosed. Many respondents from all communes answered strongly in an imperfect or neutral manner.

Table 9 shows the relationship between respondents’ level of agreement with the operation of the target facility and the degree of disclosure by the developer and funder. A similar trend to the relationship observed in

Table 6 between the level of agreement or disagreement with the operation of the target facility and the degree of prior disclosure of information on the construction plans is evident in

Table 9. These results suggest that the disclosure of information regarding MEGA-SPG developers and funders is also necessary to promote the construction of MEGA-SPGs.

Table 10 illustrates the relationship between the degree of disclosure of the developer and funder of the target facilities and the respondents’ level of trust in these entities. The findings from

Table 10 reinforce results shown in

Table 9 that the transparency of developers and funders influences respondents’ level agreement with the operation of a target facility. In essence,

Table 10 underscores that the proper disclosure of information about developers and funders fosters trust among respondents.

Table 11 explores the relationship between the extent to which the developer of the target facility and the local government sought input from the local community on the construction plans and the degree of disclosure regarding the developer and funder. Respondents who reported prior communication with the local community were more likely to be familiar with the developers and funders. This suggests that communication with the local community is crucial for promoting the construction of a MEGA-SPG.

These findings are consistent with previous research that highlights the crucial role of trust in renewable energy projects. Jobert et al. [

42] observed that transparency and early engagement are vital in establishing trust between developers and local communities. When developers are seen as open and actively involved at the local level, communities are more likely to support the projects. In contrast, when projects are perceived as secretive or driven by profit, opposition tends to grow [

42]. Trust helps communities better cope with uncertainties, making it essential for developers to prioritize transparency and community engagement to gain wider acceptance for renewable energy projects [

43].

3.2.4. Socioeconomic Impacts

This section examines the opinions of local residents regarding the impacts of MEGA-SPG construction on the local economy. Residents who believe that the project will positively impact the local economy are more likely to support its development, highlighting the importance of demonstrating economic benefits to gain community approval.

Table 12 shows the respondents’ evaluations, on a five-point scale, of the potential impact of MEGA-SPG construction on the local economy. Across all the communes, the responses predominantly indicated a positive impact, although a significant number of neutral responses were also noted.

Table 13 examines the relationship between respondents’ agreement or disagreement regarding the operation of the target facility and its perceived impact on the local economy. Perceptions of positive economic impacts appeared to play a moderating role, with neutral respondents showing significantly positive economic perceptions. These findings suggest that emphasizing economic benefits can positively influence overall perceptions. A strong correlation was observed between positive operational perceptions and positive economic impacts, thus reinforcing the importance of highlighting economic benefits when garnering support for a target facility.

These insights also align with existing research suggesting that rural communities often back wind energy projects because of the economic benefits they bring, such as boosting local revenues and creating jobs [

44,

45,

46]. In areas where traditional agricultural income is on the decline, wind energy is seen as a valuable alternative, encouraging PIMBY (please in my backyard) attitudes rather than the more common NIMBY (not in my backyard) resistance [

45,

46].

However, the presence of neutral respondents regarding both operational and economic impacts highlights the need for enhanced communication on the economic contributions of the target facility to fully align positive operational perceptions with economic benefits. For example, offering financial incentives, such as reduced or free electricity, has been suggested as a way to address local concerns and reduce opposition to wind projects [

47,

48]. Additionally, studies in the U.S. have shown that local acceptance of wind farms increases when benefits like lower taxes and higher local revenues are provided [

49].

3.2.5. Environmental Impacts

This section examines the opinions of local residents regarding the impacts of MEGA-SPG construction on the local environment. Positive perceptions of minimal environmental harm are critical, as concerns about adverse effects could hinder support. Ensuring environmentally responsible practices is essential for building community trust and encouraging acceptance of MEGA-SPG projects.

Table 14 demonstrates the impact of a MEGA-SPG on the local environment, as indicated by the respondents on a five-point scale. Communes closer to the target facility predominantly report negative environmental impacts, whereas those farther away report positive environmental impacts. These results suggest that local residents may perceive a MEGA-SPG as a “not in my back yard” (NIMBY) facility, i.e., a facility that they do not want located near where they live).

Table 15 shows the relationship between the responses regarding the impact of the target facility on the local economy and the local environment. A substantial number of respondents who perceived positive economic impacts foresee beneficial environmental outcomes. This correlation emphasizes the importance of promoting both economic and environmental benefits to cultivate overall positive perceptions of the target facility.

Interestingly, some respondents exhibited environmental optimism, despite holding neutral views on the economic impact. This suggests that emphasizing the environmental advantages of the target facility can enhance the overall perception, even when the economic benefits are viewed neutrally.

3.2.6. Discussion Based on the Results

The results of this study suggest that local residents who have access to comprehensive information about MEGA-SPG construction are more receptive to the facility. Notably, the type of information that influences the acceptability of MEGA-SPG construction is not limited to basic details about the facility but also includes diverse aspects about the developer and the funders, as well as the impact on the local economy. Importantly, the results suggest that while access to information significantly enhances acceptability, it is difficult to determine which type of information holds the highest priority. In addition to the challenges previously identified in the literature regarding the promotion of MEGA-SPG construction in Vietnam [

2,

3,

9], this study underscores the critical role of information disclosure and sharing in improving local residents’ acceptance. This finding highlights the importance of adopting communication strategies that prioritize transparency and inclusiveness to foster trust and support from local communities.

4. Conclusions

This study analyzed the factors that would lead to the acceptance of the construction of MEGA-SPGs in Vietnam by surveying the opinions of residents living near the MEGA-SPG in BR–VT. The findings highlight the significance of transparency and the disclosure of comprehensive information to local residents as essential for fostering support for MEGA-SPG projects. This includes not only information about the construction plans but also details about the developers and funders of the MEGA-SPG as well as the potential impacts on the local economy and environment. Residents who perceive transparency and adequate disclosure are more likely to support the operation and development of MEGA-SPGs, suggesting that effective communication strategies can directly impact project acceptance.

The importance for disclosure of information about the MEGA-SPG, as highlighted in the literature [

24], has also been demonstrated in Vietnam to be necessary for the acceptance of the MEGA-SPG by local residents. In addition to the weak power grid and inadequate institutional support as obstacles to promote SPG construction in Vietnam that have been identified in existing studies, this study suggests that adequate information to local residents is also needed. By focusing on the perspectives of local residents—an aspect often overlooked in previous research—this study provides a novel dimension to the challenges of promoting SPG construction in Vietnam. While earlier studies have primarily examined the obstacles faced by governments and companies, this study highlights the importance of incorporating local community perspectives into SPG development strategies.

Nevertheless, this study has limitations, as it focused on only one MEGA-SPG in Vietnam. Further research is necessary to determine the factors that contribute to the acceptance of MEGA-SPGs across different regions in Vietnam. Additionally, while care was taken to ensure objective data collection, potential biases in respondents’ answers or variability in responses may have influenced the findings. The conclusions presented here should therefore be interpreted within the context of the specific respondent group and study design.

5. Recommendations

As outlined in the Conclusions, promoting SPG construction in Vietnam requires not only addressing the weak power grid and inadequate institutional support but also ensuring the disclosure and sharing of diverse information with local residents during SPG construction. Achieving national carbon neutrality by 2050 makes it imperative for Vietnam to advance SPG development. To achieve this, it would be effective to establish a system that promotes the construction of SPGs in harmony with local communities. Specifically, such a system could include provisions to deliver tangible benefits to the community, such as allocating a portion of the electricity generated for local consumption. Developing and implementing such an improvement plan is essential to build a prosperous Vietnam.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at:

https://www.mdpi.com/article/10.3390/su162310478/s1, The questionnaire used in the interview survey is presented here. The questionnaire was translated into Vietnamese prior to its administration during the interviews.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, Y.S.; methodology, Y.S. and H.B.N.; validation, Y.S. and H.B.N.; formal analysis, Y.S.; investigation, Y.S. and H.B.N.; data curation, Y.S.; writing—original draft preparation, Y.S. and H.B.N.; writing—review and editing, Y.S. and H.B.N.; visualization, Y.S. and H.B.N.; project administration, Y.S.; funding acquisition, Y.S. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This study was funded by a research grant from the Murata Science and Education Foundation (grant number: M24AC014).

Institutional Review Board Statement

Ethical review and approval were waived for this study due to it not dealing with human biological data or data obtained by loading humans.

Informed Consent Statement

Verbal consent for academic use of the research data was obtained from the participants. Verbal rather than written consent was obtained because this study does not deal with human biological data or data obtained from human loads.

Data Availability Statement

Data available on request due to restrictions (only when it does not violate the privacy of the research collaborators of this paper or the laws and regulations of each country).

Acknowledgments

The authors are grateful to all interviewees who participated in the series of interviews and provided useful insights.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Electricity and Renewable Energy Authority (EREA); Danish Energy Agency (DEA). Vietnam Energy Outlook Report 2024; Ministry of Industry and Trade (MOIT): Hanoi, Vietnam, 2024. Available online: https://ens.dk/sites/ens.dk/files/Globalcooperation/1._eor-nz_english_june2024_0.pdf (accessed on 8 October 2024).

- Xuan, P.N.; Ngoc, D.L.; Van, V.P.; Thanh, T.H.; Van, H.D.; Anh, T.H. Mission, challenges, and prospects of renewable energy development in Vietnam. Energy Sources Part A Recovery Util. Environ. Eff. 2021, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Riva, S.E.; Le, T.T.H.; Pham, M.H.; Di, S.M.L.; Nguyen, Q.N.; Favuzza, S. Review of Potential and Actual Penetration of Solar Power in Vietnam. Energies 2020, 13, 2529. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thang, N.D.; Paul, J.B.; Kenneth, G.H.B.; Chinh, T.N. Underlying drivers and barriers for solar photovoltaics diffusion: The case of Vietnam. Energy Policy 2020, 144, 111561. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vietnam Electricity (EVN). Solar Energy Development Is in a Standstill State; Vietnam Electricity (EVN): Hanoi, Vietnam, 2019; Available online: https://en.evn.com.vn/d6/news/Solar-energy-development-is-in-a-standstill-state-66-163-1677.aspx (accessed on 8 October 2024).

- Phuong, A.N.; Malcolm, A.; Thanh, L.T.N. The development and cost of renewable energy resources in Vietnam. Util. Policy 2019, 57, 59–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luu, D.H.; Nguyen, T.H.L. Renewable energy policies for sustainable development in Vietnam. VNU J. Sci. Earth Sci. 2009, 25, 133–142. Available online: https://js.vnu.edu.vn/EES/article/view/1870/1774 (accessed on 31 July 2024).

- Viet Nam Government Portal. Full remarks by PM Pham Minh Chinh at COP26. Online Newspaper of the Government of the Socialist Republic of Vietnam. 2021. Available online: https://en.baochinhphu.vn/full-remarks-by-pm-pham-minh-chinh-at-cop26-11142627.htm (accessed on 8 October 2024).

- Urakami, A. Are the Barriers to Private Solar/Wind Investment in Vietnam Mainly Those That Limit Network Capacity Expansion? Sustainability 2023, 15, 10734. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Das, K. Renewables in Vietnam: Current Opportunities and Future Outlook. 2019. Available online: https://www.vietnam-briefing.com/news/vietnams-push-for-renewable-energy.html/ (accessed on 8 October 2024).

- StoxPlus; Eurocham Vietnam. Vietnam Renewable Energy: Challenges and Practical Solutions. In Proceedings of the International Conference, Ho Chi Minh City, Vietnam, 23 August 2018; Available online: https://eurochamvn.glueup.com/resources/protected/organization/726/event/9311/50ab0989-fcaa-492e-bcf7-4df735a8007c.pdf (accessed on 8 October 2024).

- Neefjes, K.; Hoai, D.T.T. Towards a Socially Just Energy Transition in Viet Nam Challenges and Opportunities; Friedrich-Ebert-Stiftung Vietnam: Hanoi, Vietnam, 2017; Available online: https://library.fes.de/pdf-files/bueros/vietnam/13684.pdf (accessed on 8 October 2024).

- Nguyen, T.C.; Chuc, A.T.; Dang, L.N. Green Finance in Viet Nam: Barriers and Solutions; Asian Development Bank Institute: Tokyo, Japan, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- United Nations Development Programmes (UNDP). Green Growth and Fossil Fuel Fiscal Policies in Viet Nam–Recommendations on a Roadmap for Policy Reform; UNDP: Ha Noi, Vietnam, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- United Nations Development Programmes (UNDP). Greening the Power Mix: Policies for Expanding Solar Photovoltaic Electricity in Viet Nam; UNDP: Ha Noi, Vietnam, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Nguyen, D.L. A critical review on potential and current status of wind energy in Vietnam. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2015, 43, 440–448. [Google Scholar]

- World Bank. Vietnam Solar Competitive Bidding Strategy and Framework; World Bank: Washington, DC, USA, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Vietnam Business Forum. Made in Vietnam Energy Plan 2.0; Vietnam Business Forum (VBF): Hanoi, Vietnam, 2019; Available online: https://www.amchamvietnam.com/wp-content/uploads/2019/08/MVEP-2.0_final_ENG-9-Aug.pdf (accessed on 8 October 2024).

- Kies, A.; Schyska, B.; Thanh, V.D.; Von, B.L.; Heinemann, D.; Schramm, S. Large-Scale Integration of Renewable Power Sources into the Vietnamese Power System. Energy Procedia 2017, 125, 207–213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Viet, D.T.; Phuong, V.V.; Duong, M.Q.; Khanh, M.P.; Kies, A.; Schyska, B. A Cost-Optimal Pathway to Integrate Renewable Energy into the Future Vietnamese Power System. In Proceedings of the 2018 4th International Conference on Green Technology and Sustainable Development (GTSD), Ho Chi Minh City, Vietnam, 23–24 November 2018; pp. 144–149. [Google Scholar]

- Nguyen, N.T.; Ha-Duong, M. Economic potential of renewable energy in Vietnam’s power sector. Energy Policy 2009, 37, 1601–1613. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pham, K.T.; Nguyen, A.Q.; Quan, B.Q.M. Investment Incentives for Renewable Energy in Southeast Asia: Case study of Viet Nam; International Institute for Sustainable Development (IISD): Winnipeg, MB, Canada, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Nguyen, N.Q.; Nguyen, Q.M. Impacts of Land Acquisition for Solar Farm on Farmers’ Livelihoods in Viet Nam: A Case Study in Ninh Thuan Province, Vietnam. Math. Stat. Eng. Appl. 2022, 71, 1825–1841. [Google Scholar]

- Susanne, H.; Nadejda, K.; Boris, S.; Driss, Z.; Ahmed, I.; Anthony, P. Community acceptance of large-scale solar energy installations in developing countries: Evidence from Morocco. Energy Res. Soc. Sci. 2016, 14, 80–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chia-Nan, W.; Thanh-Tuan, D.; Ngoc-Ai-Thy, N.; Jing-Wein, W. A combined Data Envelopment Analysis (DEA) and Grey Based Multiple Criteria Decision Making (G-MCDM) for solar PV power plants site selection: A case study in Vietnam. Energy Rep. 2022, 8, 1124–1142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Giovanni, M.; Sergio, R.; Andrea, L. Optimum choice and placement of concentrating solar power technologies in integrated solar combined cycle systems. Renew. Energy 2016, 96 Pt A, 172–189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sajjad, A.; Ehsan, T.; Fatemeh, S.D. Optimal Placement and Sizing for Solar Farm with Economic Evaluation, Power Line Loss and Energy Consumption Reduction. IETE J. Res. 2019, 68, 2175–2190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sandra, G.O. Community obstacles to large scale solar: NIMBY and renewables. J. Environ. Stud. Sci. 2021, 11, 85–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Juliet, E.C.; David, S.; Stephanie, L.K.; Jeffrey, J. Utility-scale solar and public attitudes toward siting: A critical examination of proximity. Land Use Policy 2016, 58, 491–501. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lunardo, A.d.S.; Paula, F.; Ana, C.B. Social acceptance of wind and solar power in the Brazilian electricity system. Environ. Dev. Sustain. 2016, 18, 1457–1476. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hamam, S.E.D.; Ahmed, S.; Hend, E.F.; Sarah, A.E. Principles of urban quality of life for a neighborhood. HBRC J. 2013, 9, 86–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dempsey, N.; Bramley, G.; Power, S.; Brown, C. The social dimension of sustainable development: Defining urban social sustainability. Sustain. Dev. 2011, 19, 289–300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- “Open Identity” of 87 Solar Power Plants That Were in Operation Before June 30, 2019. Available online: https://baodautu.vn/mo-danh-tinh-87-nha-may-dien-mat-troi-da-van-hanh-truoc-ngay-3062019-d112210.html (accessed on 31 July 2024).

- The National Electricity Development Plan. Available online: https://moit.gov.vn/tin-tuc/phat-trien-nang-luong/quy-hoach-tong-the-ve-nang-luong-quoc-gia-thoi-ky-2021-2030-tam-nhin-den-nam-2050.html (accessed on 31 July 2024).

- Schreier, M. Sampling and generalization. In The SAGE Handbook of Qualitative Data Collection; Sage Publications: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 2018; pp. 84–97. Available online: http://digital.casalini.it/9781526416063 (accessed on 10 October 2024).

- Kumar, S.; Kumar, R.S.; Prabhu, N.R.V. Sampling Framework for Personal Interviews in Qualitative Research. Palarch’s J. Archaeol. Egypt/Egyptol. 2020, 17, 7102–7114. [Google Scholar]

- Leiren, M.D.; Aakre, S.; Linnerud, K.; Julsrud, T.E.; Di Nucci, M.R.; Krug, M. Community acceptance of wind energy developments: Experience from wind energy scarce regions in Europe. Sustainability 2020, 12, 1754. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mills, S.B.; Bessette, D.; Smith, H. Exploring landowners’ post-construction changes in perceptions of wind energy in Michigan. Land Use Policy 2019, 82, 754–762. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baxter, J.; Walker, C.; Ellis, G.; Devine-Wright, P.; Adams, M.; Fullerton, R.S. Scale, history and justice in community wind energy: An empirical review. Energy Res. Soc. Sci. 2020, 68, 101532. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Simcock, N. Exploring how stakeholders in two community wind projects use a ‘those affected’ principle to evaluate the fairness of each project’s spatial boundary. Local Environ. 2014, 19, 241–258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Warren, C.R.; McFadyen, M. Does community ownership affect public attitudes to wind energy? A case study from south-west Scotland. Land Use Policy 2010, 27, 204–213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jobert, A.; Laborgne, P.; Mimler, S. Local acceptance of wind energy: Factors of success identified in French and German case studies. Energy Policy 2007, 35, 2751–2760. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huijts, N.M.A.; Midden, C.J.H.; Meijnders, A.L. Social acceptance of carbon dioxide storage. Energy Policy 2007, 35, 2780–2789. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aitken, M. Wind power and community benefits: Challenges and opportunities. Energy Policy 2010, 38, 6066–6075. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wolsink, M. Wind power and the NIMBY-myth: Institutional capacity and the limited significance of public support. Renew. Energy 2000, 21, 49–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wolsink, M. Wind power implementation: The nature of public attitudes: Equity and fairness instead of ‘backyard motives’. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2007, 11, 1188–1207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Devine-Wright, P. Public engagement with large-scale renewable energy technologies: Breaking the cycle of NIMBYism. Wiley Interdiscip. Rev. Clim. Chang. 2011, 2, 19–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pierpont, N. Wind Turbine Syndrome: A Report on a Natural Experiment; K-Selected Books: Santa Fe, NM, USA, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Slattery, M.C.; Johnson, B.L.; Swofford, J.A.; Pasqualetti, M.J. The predominance of economic development in the support for large-scale wind farms in the US Great Plains. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2012, 16, 3690–3701. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Figure 1.

MEGA-SPGs in Vietnam that were operational by June 2019.

Figure 1.

MEGA-SPGs in Vietnam that were operational by June 2019.

Figure 2.

(a) Communes around the target facility. (b) Target communes for interviews.

Figure 2.

(a) Communes around the target facility. (b) Target communes for interviews.

Table 1.

Dates of interviews and the number of respondents per target commune.

Table 1.

Dates of interviews and the number of respondents per target commune.

| Commune | Survey Date | Distance from MEGA-SPG | Number of

Respondents |

|---|

| Nghĩa Thành | 17 March 2024

&

31 March 2024 | ~1 km | 25 |

| Suối Nghệ | ~3 km | 23 |

| Châu Pha | 7 April 2024 | ~5 km | 25 |

| Tóc Tiên | 9 April 2024

&

11 April 2024 | ~10 km | 25 |

| Phú Mỹ | ~20 km | 25 |

Table 2.

Sex and age distributions of respondents by commune.

Table 2.

Sex and age distributions of respondents by commune.

| AGE | Nghĩa Thành | Suối Nghệ | Châu Pha | Tóc Tiên | Phú Mỹ | SUM |

|---|

| Under 19 | 1 (1) | 0 (0) | 2 (0) | 0 (0) | 1 (0) | 4 (1) | 3.3% |

| 20–29 | 4 (1) | 2 (1) | 4 (2) | 2 (1) | 8 (2) | 20 (7) | 16.4% |

| 30–39 | 6 (0) | 7 (1) | 7 (1) | 7 (4) | 7 (3) | 34 (9) | 27.9% |

| 40–49 | 3 (2) | 6 (5) | 5 (1) | 5 (3) | 5 (2) | 24 (13) | 19.7% |

| 50–59 | 4 (1) | 6 (4) | 5 (2) | 5 (1) | 3 (3) | 23 (11) | 18.9% |

| 60–69 | 5 (1) | 2 (1) | 1 (1) | 4 (0) | 1 (0) | 13 (3) | 10.7% |

| Over 70 | 2 (1) | 0 (0) | 1 (0) | 1 (1) | 0 (0) | 4 (2) | 3.3% |

| SUM | 25 (7) | 23 (12) | 25 (7) | 24 (11 *) | 25 (10) | 122 (47) | 100.0% |

Table 3.

Duration of residence and recognition of target facility of respondents by commune.

Table 3.

Duration of residence and recognition of target facility of respondents by commune.

| | Nghĩa Thành | Suối Nghệ | Châu Pha | Tóc Tiên | Phú Mỹ | SUM |

|---|

| ~1 year | 1 (0) | 2 (2) | 3 (3) | 2 (2) | 1 (1) | 9 (8) | 7.4% |

| ~3 years | 0 (0) | 1 (1) | 4 (3) | 2 (2) | 2 (1) | 9 (7) | 7.4% |

| ~5 years | 1 (1) | 2 (0) | 1 (1) | 2 (1) | 4 (2) | 10 (5) | 8.3% |

| ~10 years | 2 (1) | 2 (0) | 4 (2) | 2 (0) | 4 (3) | 14 (6) | 11.6% |

| Over 10 years | 21 (6) | 15 (8) | 13 (7) | 16 (2) | 14 (6) | 79 (29) | 65.3% |

| SUM | 25 (8) | 22 (11) | 25 (16) | 24 (7) | 25 (13) | 121 (55) | 100.0% |

Table 4.

Respondents’ levels of agreement with the operation of the target facility by commune.

Table 4.

Respondents’ levels of agreement with the operation of the target facility by commune.

| Agree ⇔ Disagree | | Nghĩa Thành | Suối Nghệ | Châu Pha | Tóc Tiên | Phú Mỹ | SUM |

| 1 | 5 | 20.0% | 0 | 0.0% | 2 | 8.0% | 1 | 4.0% | 5 | 20.0% | 13 | 10.7% |

| 2 | 0 | 0.0% | 0 | 0.0% | 0 | 0.0% | 0 | 0.0% | 0 | 0.0% | 0 | 0.0% |

| 3 | 11 | 44.0% | 7 | 31.8% | 13 | 52.0% | 19 ** | 76.0% | 11 | 44.0% | 61 | 50.0% |

| 4 | 3 * | 12.0% | 1 | 4.5% | 1 | 4.0% | 0 | 0.0% | 0 | 0.0% | 5 | 4.1% |

| 5 | 6 | 24.0% | 14 ** | 63.6% | 9 | 36.0% | 5 | 20.0% | 9 | 36.0% | 43 | 35.2% |

| | SUM | 25 | | 22 | | 25 | | 25 | | 25 | | 122 | 100.0% |

Table 5.

Degree to which local residents feel they received prior explanations of construction plans.

Table 5.

Degree to which local residents feel they received prior explanations of construction plans.

| Perfect ⇔ Imperfect | | Nghĩa Thành | Suối Nghệ | Châu Pha | Tóc Tiên | Phú Mỹ | SUM |

| 1 | 13 | 52.0% | 12 | 60.0% | 14 | 56.0% | 15 | 60.0% | 8 * | 32.0% | 62 | 51.7% |

| 2 | 1 | 4.0% | 0 | 0.0% | 0 | 0.0% | 0 | 0.0% | 0 | 0.0% | 1 | 0.8% |

| 3 | 3 * | 12.0% | 2 * | 10.0% | 8 | 32.0% | 9 | 36.0% | 14 ** | 56.0% | 36 | 30.0% |

| 4 | 1 | 4.0% | 0 | 0.0% | 1 | 4.0% | 0 | 0.0% | 0 | 0.0% | 2 | 1.7% |

| 5 | 7 | 28.0% | 6 | 30.0% | 2 | 8.0% | 1 | 4.0% | 3 | 12.0% | 19 | 15.8% |

| SUM | 25 | | 20 | | 25 | | 25 | | 25 | | 120 | 100.0% |

Table 6.

Relationship between the level of agreement regarding the operation of a target facility (vertical axis) and the degree to which residents informed of the construction plans in advance (horizontal axis).

Table 6.

Relationship between the level of agreement regarding the operation of a target facility (vertical axis) and the degree to which residents informed of the construction plans in advance (horizontal axis).

| | Obtaining Advance Information on Facility Construction | |

|---|

| Imperfect ⇔ Perfect |

|---|

Level of agreement with facility operation

Agree ⇔ Disagree | | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | SUM |

| 1 | 10 * | 16.4% | 0 | 0.0% | 2 | 5.6% | 0 | 0.0% | 0 | 0.0% | 12 | 10.1% |

| 2 | 0 | 0.0% | 0 | 0.0% | 0 | 0.0% | 0 | 0.0% | 0 | 0.0% | 0 | 0.0% |

| 3 | 28 | 45.9% | 1 | 100.0% | 27 ** | 75.0% | 1 | 50.0% | 3 ** | 15.8% | 60 | 50.4% |

| 4 | 2 | 3.3% | 0 | 0.0% | 2 | 5.6% | 0 | 0.0% | 1 | 5.3% | 5 | 4.2% |

| 5 | 21 | 34.4% | 0 | 0.0% | 5 ** | 13.9% | 1 | 50.0% | 15 ** | 78.9% | 42 | 35.3% |

| SUM | 61 | | 1 | | 36 | | 2 | | 19 | | 119 | 100.0% |

Table 7.

Relationship between the extent to which the developer of the target facility and the local government sought input from the local community on the construction plans (vertical axis) and the extent to which the developer incorporated the local community’s input into the construction plan (horizontal axis).

Table 7.

Relationship between the extent to which the developer of the target facility and the local government sought input from the local community on the construction plans (vertical axis) and the extent to which the developer incorporated the local community’s input into the construction plan (horizontal axis).

| | Reflecting Local Residents’ Opinions

on Facility Construction Plans | |

Sufficiency of hearing the opinions of local residents

Perfect ⇔ Imperfect | | Insufficient⇔Sufficient |

| | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | SUM |

| 1 | 22 ** | 95.7% | 0 | 0.0% | 31 | 49.2% | 0 * | 0.0% | 9 * | 31.0% | 62 | 52.1% |

| 2 | 0 | 0.0% | 0 | 0.0% | 1 | 1.6% | 0 | 0.0% | 0 | 0.0% | 1 | 0.8% |

| 3 | 0 ** | 0.0% | 0 | 0.0% | 29 ** | 46.0% | 3 | 75.0% | 6 | 20.7% | 38 | 31.9% |

| 4 | 0 | 0.0% | 0 | 0.0% | 0 | 0.0% | 1 ** | 25.0% | 0 | 0.0% | 1 | 0.8% |

| 5 | 1 | 4.3% | 0 | 0.0% | 2 ** | 3.2% | 0 | 0.0% | 14 ** | 48.3% | 17 | 14.3% |

| SUM | 23 | | 0 | | 63 | | 4 | | 29 | | 119 | 100.0% |

Table 8.

Degree of disclosure of information about the developer or funder of the target facility.

Table 8.

Degree of disclosure of information about the developer or funder of the target facility.

| Perfect ⇔ Imperfect | | Nghĩa Thành | Suối Nghệ | Châu Pha | Tóc Tiên | Phú Mỹ | SUM |

| 1 | 12 | 50.0% | 7 | 31.8% | 13 | 52.0% | 10 | 40.0% | 5 * | 20.0% | 47 | 38.8% |

| 2 | 1 | 4.2% | 0 | 0.0% | 0 | 0.0% | 0 | 0.0% | 0 | 0.0% | 1 | 0.8% |

| 3 | 5 ** | 20.8% | 7 | 31.8% | 11 | 44.0% | 15 | 60.0% | 18 ** | 72.0% | 56 | 46.3% |

| 4 | 0 | 0.0% | 0 | 0.0% | 0 | 0.0% | 0 | 0.0% | 1 | 4.0% | 1 | 0.8% |

| 5 | 6 | 25.0% | 8 ** | 36.4% | 1 | 4.0% | 0 * | 0.0% | 1 | 4.0% | 16 | 13.2% |

| SUM | 24 | | 22 | | 25 | | 25 | | 25 | | 121 | 100.0% |

Table 9.

Relationship between the level of agreement with the operation of the target facility (vertical axis) and degree of disclosure about the developer and funder (horizontal axis).

Table 9.

Relationship between the level of agreement with the operation of the target facility (vertical axis) and degree of disclosure about the developer and funder (horizontal axis).

| | Disclosure of Information About Developers and Funders | | |

|---|

| Imperfect ⇔ Perfect | | |

|---|

Level of agreement with facility operation

Agree ⇔ Disagree | | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | SUM |

| 1 | 8 * | 17.4% | 0 | 0.0% | 3 | 5.4% | 0 | 0.0% | 0 | 0.0% | 11 | 9.2% |

| 2 | 0 | 0.0% | 0 | 0.0% | 0 | 0.0% | 0 | 0.0% | 0 | 0.0% | 0 | 0.0% |

| 3 | 20 | 43.5% | 0 | 0.0% | 39 ** | 69.6% | 0 | 0.0% | 1 ** | 6.3% | 60 | 50.0% |

| 4 | 1 | 2.2% | 1 ** | 100.0% | 1 | 1.8% | 0 | 0.0% | 2 | 12.5% | 5 | 4.2% |

| 5 | 17 | 37.0% | 0 | 0.0% | 13 ** | 23.2% | 1 | 100.0% | 13 ** | 81.3% | 44 | 36.7% |

| SUM | 46 | | 1 | | 56 | | 1 | | 16 | | 120 | 100.0% |

Table 10.

Relationship between the degree of disclosure about the developer and funder of the target facilities (vertical axis) and the respondents’ level of trust in them (horizontal axis).

Table 10.

Relationship between the degree of disclosure about the developer and funder of the target facilities (vertical axis) and the respondents’ level of trust in them (horizontal axis).

| | Trust in Developers and Funders | |

Disclosure of information about developers and funders

Perfect ⇔ Imperfect | | Distrust⇔Trust |

| | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | SUM |

| 1 | 11 ** | 100.0% | 1 | 100.0% | 29 | 36.3% | 1 | 25.0% | 5 * | 20.8% | 47 | 39.2% |

| 2 | 0 | 0.0% | 0 | 0.0% | 1 | 1.3% | 0 | 0.0% | 0 | 0.0% | 1 | 0.8% |

| 3 | 0 ** | 0.0% | 0 | 0.0% | 49 ** | 61.3% | 2 | 50.0% | 4 ** | 16.7% | 55 | 45.8% |

| 4 | 0 | 0.0% | 0 | 0.0% | 0 | 0.0% | 0 | 0.0% | 1 | 4.2% | 1 | 0.8% |

| 5 | 0 | 0.0% | 0 | 0.0% | 1 ** | 1.3% | 1 | 25.0% | 14 ** | 58.3% | 16 | 13.3% |

| SUM | 11 | | 1 | | 80 | | 4 | | 24 | | 120 | 100.0% |

Table 11.

Relationship between the extent to which the developer of the target facility and the local government sought input from the local community on the construction plans (vertical axis) and the degree of disclosure about the developer and funder (horizontal axis).

Table 11.

Relationship between the extent to which the developer of the target facility and the local government sought input from the local community on the construction plans (vertical axis) and the degree of disclosure about the developer and funder (horizontal axis).

| | Disclosure of Information About Developers and Funders | |

| Sufficiency of hearing the opinions of local residents | | | Imperfect⇔Perfect |

| Perfect ⇔ Imperfect | | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | SUM |

| 1 | 43 ** | 91.5% | 1 | 100.0% | 16 ** | 28.6% | 0 | 0.0% | 3 * | 20.0% | 63 | 52.5% |

| 2 | 0 | 0.0% | 0 | 0.0% | 1 | 1.8% | 0 | 0.0% | 0 | 0.0% | 1 | 0.8% |

| 3 | 2 ** | 4.3% | 0 | 0.0% | 35 ** | 62.5% | 0 | 0.0% | 1 * | 6.7% | 38 | 31.7% |

| 4 | 0 | 0.0% | 0 | 0.0% | 1 | 1.8% | 0 | 0.0% | 0 | 0.0% | 1 | 0.8% |

| 5 | 2 * | 4.3% | 0 | 0.0% | 3 * | 5.4% | 1 * | 100.0% | 11 ** | 73.3% | 17 | 14.2% |

| SUM | 47 | | 1 | | 56 | | 1 | | 15 | | 120 | 100.0% |

Table 12.

Results of respondents’ responses on a five-point scale regarding the impact of the construction of the MEGA-SPG on the local economy.

Table 12.

Results of respondents’ responses on a five-point scale regarding the impact of the construction of the MEGA-SPG on the local economy.

| Positive ⇔ Negative | | Nghĩa Thành | Suối Nghệ | Châu Pha | Tóc Tiên | Phú Mỹ | SUM |

| 1 | 3 ** | 13.0% | 0 | 0.0% | 0 | 0.0% | 0 | 0.0% | 0 | 0.0% | 3 | 2.5% |

| 2 | 1 | 4.3% | 0 | 0.0% | 1 | 4.0% | 0 | 0.0% | 0 | 0.0% | 2 | 1.7% |

| 3 | 14 | 60.9% | 8 | 34.8% | 15 | 60.0% | 9 | 36.0% | 6 * | 24.0% | 52 | 43.0% |

| 4 | 1 | 4.3% | 3 | 13.0% | 1 | 4.0% | 2 | 8.0% | 2 | 8.0% | 9 | 7.4% |

| 5 | 4 ** | 17.4% | 12 | 52.2% | 8 | 32.0% | 14 | 56.0% | 17 * | 68.0% | 55 | 45.5% |

| SUM | 23 | | 23 | | 25 | | 25 | | 25 | | 121 | 100.0% |

Table 13.

Relationship between the level of agreement with the operation of the target facility (vertical axis) and its impact on the local economy (horizontal axis).

Table 13.

Relationship between the level of agreement with the operation of the target facility (vertical axis) and its impact on the local economy (horizontal axis).

| | Impact on the Local Economy | | |

|---|

| Negative ⇔ Positive | | |

|---|

| Level of agreement with facility operation | Agree ⇔ Disagree | | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | SUM |

| 1 | 2 ** | 66.7% | 1 | 50.0% | 2 | 3.8% | 1 | 11.1% | 5 | 9.3% | 11 | 9.2% |

| 2 | 0 | 0.0% | 0 | 0.0% | 0 | 0.0% | 0 | 0.0% | 0 | 0.0% | 0 | 0.0% |

| 3 | 0 | 0.0% | 1 | 50.0% | 36 ** | 69.2% | 6 | 66.7% | 18 ** | 33.3% | 61 | 50.8% |

| 4 | 0 | 0.0% | 0 | 0.0% | 1 | 1.9% | 1 | 11.1% | 3 | 5.6% | 5 | 4.2% |

| 5 | 1 | 33.3% | 0 | 0.0% | 13 * | 25.0% | 1 | 11.1% | 28 ** | 51.9% | 43 | 35.8% |

| | SUM | 3 | | 2 | | 52 | | 9 | | 54 | | 120 | 100.0% |

Table 14.

Impact of MEGA-SPGs on the local environment, as indicated by respondents on a five-point scale.

Table 14.

Impact of MEGA-SPGs on the local environment, as indicated by respondents on a five-point scale.

| Positive ⇔ Negative | | Nghĩa Thành | Suối Nghệ | Châu Pha | Tóc Tiên | Phú Mỹ | SUM |

| 1 | 5 * | 20.8% | 3 | 13.6% | 3 | 12.0% | 0 | 0.0% | 0 | 0.0% | 11 | 9.1% |

| 2 | 1 | 4.2% | 0 | 0.0% | 8 ** | 32.0% | 0 | 0.0% | 0 | 0.0% | 9 | 7.4% |

| 3 | 14 | 58.3% | 11 | 50.0% | 11 | 44.0% | 12 | 48.0% | 10 | 40.0% | 58 | 47.9% |

| 4 | 0 | 0.0% | 1 | 4.5% | 1 | 4.0% | 3 | 12.0% | 1 | 4.0% | 6 | 5.0% |

| 5 | 4 | 16.7% | 7 | 31.8% | 2 ** | 8.0% | 10 | 40.0% | 14 ** | 56.0% | 37 | 30.6% |

| SUM | 24 | | 22 | | 25 | | 25 | | 25 | | 121 | 100.0% |

Table 15.

Relationship between the respective responses for the impact of the target facility on the local economy (vertical axis) and its impact on the local environment (horizontal axis).

Table 15.

Relationship between the respective responses for the impact of the target facility on the local economy (vertical axis) and its impact on the local environment (horizontal axis).

| | Impact on the Local Environment | |

|---|

| Negative ⇔ Positive |

|---|

| Impact on the local economy | Positive ⇔ Negative | | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | SUM |

| 1 | 2 ** | 18.2% | 0 | 0.0% | 0 | 0.0% | 0 | 0.0% | 0 | 0.0% | 2 | 1.7% |

| 2 | 1 | 9.1% | 1 * | 11.1% | 0 | 0.0% | 0 | 0.0% | 0 | 0.0% | 2 | 1.7% |

| 3 | 6 | 54.5% | 7 * | 77.8% | 36 ** | 63.2% | 1 | 16.7% | 2 ** | 5.6% | 52 | 43.7% |

| 4 | 0 | 0.0% | 1 | 11.1% | 5 | 8.8% | 1 | 16.7% | 2 | 5.6% | 9 | 7.6% |

| 5 | 2 | 18.2% | 0 ** | 0.0% | 16 ** | 28.1% | 4 | 66.7% | 32 ** | 88.9% | 54 | 45.4% |

| SUM | 11 | | 9 | | 57 | | 6 | | 36 | | 119 | 100.0% |

| Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).