Guardians of the Green: Exploring Climate Advocacy, Data Privacy-Conscious Marketing, and Social Moral Licensing in Regenerative Tourism in Hawaii

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Literature Review

2.1. Climate Advocacy

2.2. Social Moral Licensing

2.3. Data Privacy-Conscious Marketing

2.4. Regenerative Tourism Intention

2.5. Climate Advocacy and Regenerative Tourism Intention

2.6. Moderating Effects of Data Privacy-Conscious Marketing

2.7. Moderating Effects of Social Moral Licensing

3. Methods

3.1. Sampling and Procedure

3.2. Measures

3.3. Data Analysis

4. Results

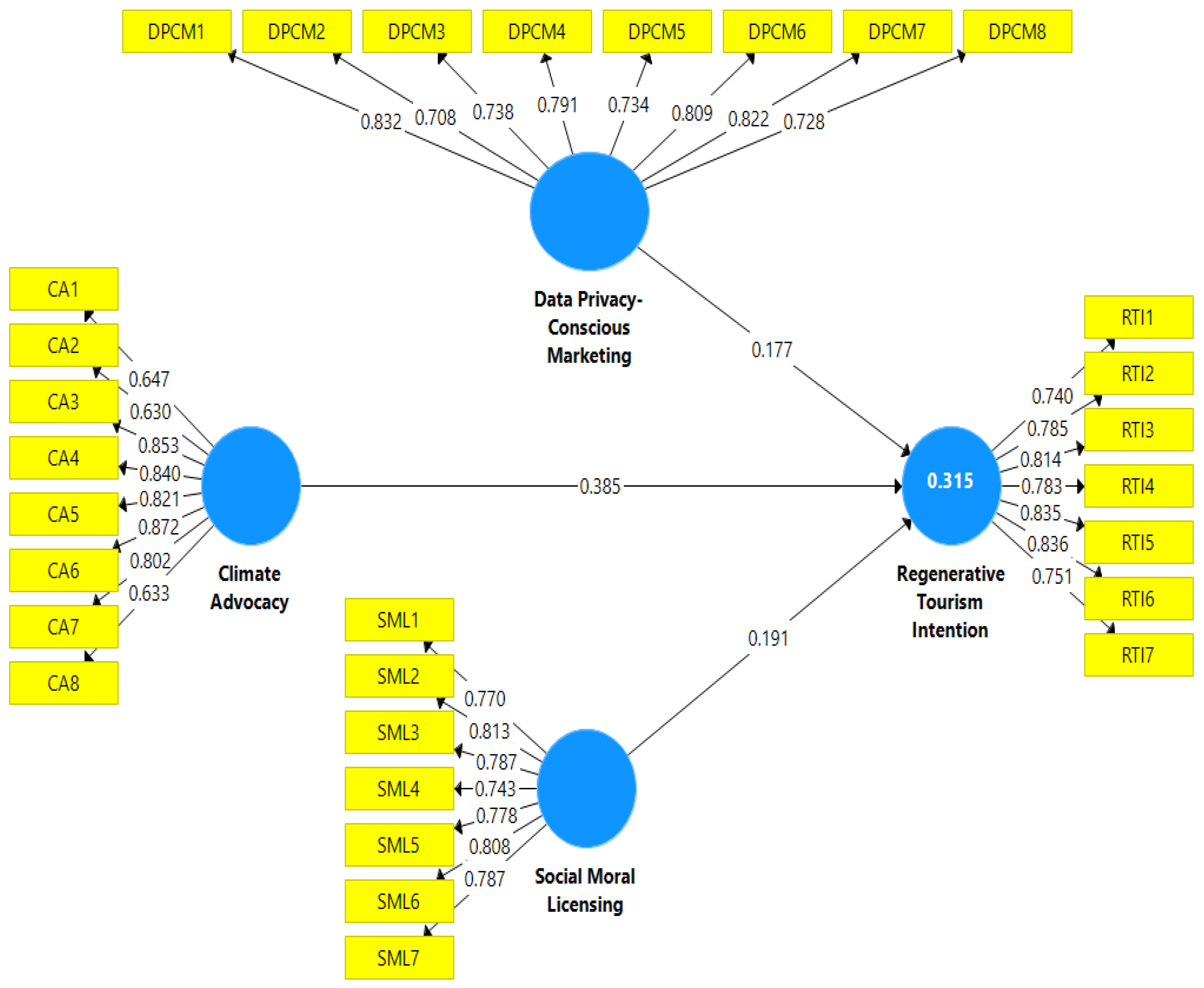

4.1. Measurement Model

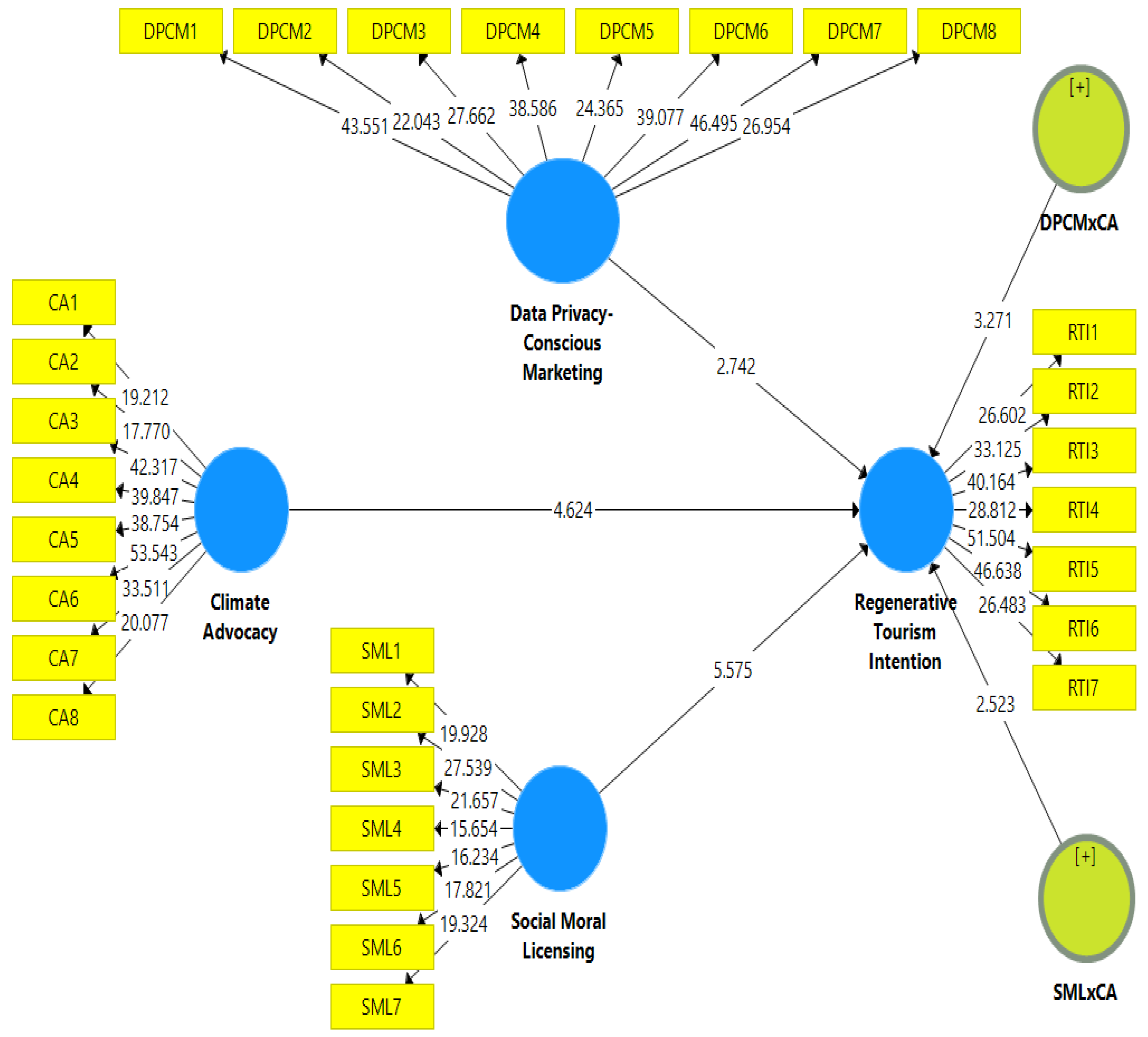

4.2. Structural Model

5. Discussion

5.1. Theoretical and Practical Implications

5.2. Limitations and Recommendations

6. Conclusions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A

- “I actively participate in events and/or activities aimed at raising awareness about climate change.”

- “I frequently discuss the importance of climate action with my friends, family, or colleagues.”

- “I support policies and initiatives that aim to reduce carbon emissions and mitigate climate change.”

- “I regularly share information about climate change and environmental issues on social media and/or other platforms.”

- “I engage in or contribute to organizations or groups that advocate for environmental protection and climate action.”

- “I encourage others to adopt sustainable practices and reduce their environmental impact.”

- “I collaborate with others to organize and/or promote activities that address climate change and environmental sustainability.”

- “I advocate for climate-related issues by contacting policymakers, signing petitions, or participating in public demonstrations.”

- “Improve the social, economic and environmental conditions at the host destination.”

- “Enhance the natural and cultural environment at the host destination.”

- “Enrich the local communities at the host destination.”

- “Enhance the quality of life for local people and communities at the host destination.”

- “Participate in host destination activities that help in reversing climate change.”

- “Make the host destination a better place for both current and future generations.”

- “Leave the host destination a place ‘better’ than it was before.”

- “I trust tourism businesses that transparently explain how my personal data will be collected and used.”

- “I am more likely to engage with tourism brands that allow me to control how my data are shared or used for marketing purposes.”

- “Tourism businesses that comply with legal regulations regarding data privacy earn my confidence.”

- “I prefer tourism services that clearly communicate the benefits of sharing personal information.”

- “I feel comfortable sharing my personal data with tourism companies that demonstrate ethical data-handling practices.”

- “I appreciate tourism businesses that respond promptly and effectively to privacy-related concerns.”

- “Tourism brands that personalize marketing efforts while ensuring data security enhance my trust in their services.”

- “I am more likely to recommend tourism businesses that prioritize protecting consumer data from breaches and misuse.”

- “I feel justified indulging in luxurious travel experiences after engaging in environmentally responsible activities, such as recycling or supporting local communities.”

- “I believe that my participation in regenerative tourism practices offsets the impact of other less eco-friendly choices I might make during my travels.”

- “After contributing to regenerative tourism initiatives, I allow myself to prioritize comfort or convenience over sustainability in other decisions.”

- “I perceive my eco-friendly actions while traveling as evidence of being a responsible tourist, even if I occasionally engage in less sustainable behaviors.”

- “I sometimes use my previous regenerative tourism choices as a reason to reward myself with experiences that might not be environmentally friendly.”

- “Knowing I have made ethical travel choices in the past motivates me to continue making sustainable decisions throughout my trip.”

- “I rationalize behaviors like increased energy or water use during travel as supporting the local economy, especially after engaging in regenerative tourism activities.”

References

- Sherman, D.K.; Van Boven, L. The connections—And misconnections—Between the public and politicians over climate policy: A social psychological perspective. Soc. Issues Policy Rev. 2024, 18, 31–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, Y.; Jia, R.; Razzaq, A.; Bao, Q. Social network platforms and climate change in China: Evidence from TikTok. Technol. Forecast. Soc. Change 2024, 200, 123197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luong, V.H.; Manthiou, A.; Kang, J.; Nguyen, C. The building blocks of regenerative tourism and hospitality: A text-mining approach. Curr. Issues Tour. 2024, 27, 361–380. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chaplain, J. Storytelling and worldmaking climate justice futures: Indigenous climate advocacy and transnational solidarity in UN climate conferences. Q. J. Speech 2024, 110, 1–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zaman, U. Seizing momentum on climate action: Nexus between net-zero commitment concern, destination competitiveness, influencer marketing, and regenerative tourism intention. Sustainability 2023, 15, 5213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bellato, L.; Pollock, A. Regenerative tourism: A state-of-the-art review. Tour. Geogr. 2023, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zaman, U. Nexus of Regenerative Tourism Destination Competitiveness, Climate Advocacy and Visit Intention: Mediating Role of Travel FOMO and Destination Loyalty. Sustainability 2024, 16, 7827. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fauzi, M.A.; Hanafiah, M.H.; Kunjuraman, V. Tourists’ intention to visit green hotels: Building on the theory of planned behaviour and the value-belief-norm theory. J. Tour. Futur. 2024, 10, 255–276. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Böhler, H.; Hanegraaff, M.; Schulze, K. Does climate advocacy matter? The importance of competing interest groups for national climate policies. Clim. Policy 2022, 22, 961–975. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bellato, L.; Frantzeskaki, N.; Lee, E.; Cheer, J.M.; Peters, A. Transformative epistemologies for regenerative tourism: Towards a decolonial paradigm in science and practice? J. Sustain. Tour. 2024, 32, 1161–1181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, S.; Hao, F. Metaverse and regenerative tourism: The role of avatars in promoting sustainable practices. Asia Pac. J. Tour. Res. 2024, 29, 1–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tshuma, S.; Masengu, R.; Dube, M. Security and Privacy Challenges in Digital Marketing. In AI-Driven Marketing Research and Data Analytics; IGI Global: New York, NY, USA, 2024; pp. 325–341. [Google Scholar]

- Lucas, C.; Aguiar, E.; Macedo, P.; Wu, Z.; Han, Q. Privacy-Preserving User Modeling for Digital Marketing Campaigns: The Case of a Data Monetization Platform. In Digital Marketing & eCommerce Conference; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2022; pp. 171–179. [Google Scholar]

- Rojas, N.S.; Sand, M.S.; Gross, S. Regenerative adventure tourism. Going beyond sustainability--a horizon 2050 paper. Tour. Rev. 2024. ahead-of-print. [Google Scholar]

- Zaman, U.; Aktan, M.; Agrusa, J.; Khwaja, M.G. Linking regenerative travel and residents’ support for tourism development in Kaua’i island (Hawaii): Moderating-mediating effects of travel-shaming and foreign tourist attractiveness. J. Travel Res. 2023, 62, 782–801. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wen, N.; Hu, T.E. License is ‘suspended’: The impact of social sharing on curbing moral licensing. J. Consum. Mark. 2023, 40, 712–720. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gabehart, K.M.; Nam, A.; Weible, C.M. Lessons from the Advocacy Coalition Framework for climate change policy and politics. Clim. Action 2022, 1, 13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hogg, M.A. Social Identity Theory. In Understanding Peace and Conflict Through Social Identity Theory: Contemporary Global Perspectives; McKeown, S., Haji, R., Ferguson, N., Eds.; Springer International Publishing: Cham, Switzerland, 2016; pp. 3–17. [Google Scholar]

- McCarthy, B. Moral licensing and habits: Do solar households make negligent choices? Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2024, 191, 114213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burger, A.M.; Schuler, J.; Eberling, E. Guilty pleasures: Moral licensing in climate-related behavior. Glob. Environ. Chang. 2022, 72, 102415. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Strange, K.F.; Satorras, M.; March, H. Intersectional climate action: The role of community-based organisations in urban climate justice. Local Environ. 2024, 29, 1–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Latter, B.; Demski, C.; Capstick, S. Wanting to be part of change but feeling overworked and disempowered: Researchers’ perceptions of climate action in UK universities. PLoS Clim. 2024, 3, e0000322. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ajzen, I. The theory of planned behavior. Organ. Behav. Hum. Decis. Process. 1991, 50, 179–211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qian, S.; Lu, Y.; Peng, Y.; Shen, C.C.; Xu, H. Convergence or divergence? A cross-platform analysis of climate change visual content categories, features, and social media engagement on Twitter and Instagram. Public Relat. Rev. 2024, 50, 102454. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boykoff, M.; Oonk, D. Evaluating the perils and promises of academic climate advocacy. Clim. Change 2020, 163, 27–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rabaa, S.; Wilken, R.; Geisendorf, S. Does recalling energy efficiency measures reduce subsequent climate-friendly behavior? An experimental study of moral licensing rebound effects. Ecol. Econ. 2024, 217, 108051. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lasarov, W.; Hoffmann, S. Social moral licensing. J. Bus. Ethics 2020, 165, 45–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lasarov, W.; Mai, R.; Hoffmann, S. The backfire effect of sustainable social cues. New evidence on social moral licensing. Ecol. Econ. 2022, 195, 107376. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bem, D.J. Self-Perception Theory11Development of Self-Perception Theory Was Supported Primarily by a Grant from the National Science Foundation (GS 1452) Awarded to the Author During His Tenure at Carnegie-Mellon University; Berkowitz, L., Ed.; Academic Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 1972; Volume 6, pp. 1–62. [Google Scholar]

- Blanken, I.; Van De Ven, N.; Zeelenberg, M. A meta-analytic review of moral licensing. Personal. Soc. Psychol. Bull. 2015, 41, 540–558. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harmon-Jones, E.; Mills, J. An introduction to cognitive dissonance theory and an overview of current perspectives on the theory. In Cognitive Dissonance: Reexamining a Pivotal Theory in Psychology, 2nd ed.; American Psychological Association: Washington, DC, USA, 2019; pp. 3–24. [Google Scholar]

- Deslée, A.; Cloarec, J. Safeguarding Privacy: Ethical Considerations in Data-Driven Marketing. In The Impact of Digitalization on Current Marketing Strategies; Emerald Publishing Limited: Bingley, UK, 2024; pp. 147–161. [Google Scholar]

- Malgieri, G. In/acceptable marketing and consumers’ privacy expectations: Four tests from EU data protection law. J. Consum. Mark. 2023, 40, 209–223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, Q.; Lucas, C.; Aguiar, E.; Macedo, P.; Wu, Z. Towards privacy-preserving digital marketing: An integrated framework for user modeling using deep learning on a data monetization platform. Electron. Commer. Res. 2023, 23, 1701–1730. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jos, P.H. Social Contract Theory: Implications for Professional Ethics. Am. Rev. Public Adm. 2006, 36, 139–155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, C.; Pan, Z.; Hou, C. Marketing data security and privacy protection based on federated gamma in cloud computing environment. Int. J. Intell. Netw. 2023, 4, 261–271. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pick, D. Data-driven Marketing in the Carsharing Economy--Focus on Privacy Concerns. In Data-Driven Marketing; Springer: Gabler, Wiesbaden, 2020; pp. 213–234. [Google Scholar]

- Zaman, U. Missing the forest for the trees: Scientometric analysis of Sustainable versus regenerative tourism (1966–2023). Pak. J. Commer. Soc. Sci. 2024, 18, 468–502. [Google Scholar]

- Suárez-Rojas, C.; Hernández, M.M.G.; León, C.J. Sustainability in whale-watching: A literature review and future research directions based on regenerative tourism. Tour. Manag. Perspect. 2023, 47, 101120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bleier, A.; Goldfarb, A.; Tucker, C. Consumer privacy and the future of data-based innovation and marketing. Int. J. Res. Mark. 2020, 37, 466–480. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bellato, L.; Frantzeskaki, N.; Nygaard, C.A. Regenerative tourism: A conceptual framework leveraging theory and practice. Tour. Geogr. 2023, 25, 1026–1046. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meral, K.Z. Strategic Social Media Marketing and Data Privacy. In Management Strategies to Survive in a Competitive Environment: How to Improve Company Performance; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2021; pp. 187–199. [Google Scholar]

- Gutierrez, A.; O’Leary, S.; Rana, N.P.; Dwivedi, Y.K.; Calle, T. Using privacy calculus theory to explore entrepreneurial directions in mobile location-based advertising: Identifying intrusiveness as the critical risk factor. Comput. Hum. Behav. 2019, 95, 295–306. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sarstedt, M.; Liu, Y. Advanced marketing analytics using partial least squares structural equation modeling (PLS-SEM). J. Mark. Anal. 2024, 12, 1–5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vaithilingam, S.; Ong, C.S.; Moisescu, O.I.; Nair, M.S. Robustness checks in PLS-SEM: A review of recent practices and recommendations for future applications in business research. J. Bus. Res. 2024, 173, 114465. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zaman, U. Nexus of tourism affinity, perceived behavioral control and green environmental literacy in support of regenerative tourism. Pak. J. Commer. Soc. Sci. 2024, 18, 781–810. [Google Scholar]

- He, J.; Zaman, U. Sustainable sojourns: Fostering sustainable hospitality practices to meet UN-SDGs. PLoS ONE 2024, 19, e0307469. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Cronbach’s Alpha | rho_A | Composite Reliability | Average Variance Extracted (AVE) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Climate Advocacy | 0.898 | 0.907 | 0.919 | 0.591 |

| Data Privacy-Conscious Marketing | 0.902 | 0.903 | 0.921 | 0.595 |

| Regenerative Tourism Intention | 0.901 | 0.903 | 0.922 | 0.629 |

| Social Moral Licensing | 0.897 | 0.908 | 0.918 | 0.615 |

| Climate Advocacy | Data Privacy-Conscious Marketing | Regenerative Tourism Intention | Social Moral Licensing | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Climate Advocacy | 0.769 | |||

| Data Privacy-Conscious Marketing | 0.663 | 0.772 | ||

| Regenerative Tourism Intention | 0.516 | 0.426 | 0.793 | |

| Social Moral Licensing | 0.071 | −0.036 | 0.213 | 0.784 |

| Climate Advocacy | Data Privacy-Conscious Marketing | Regenerative Tourism Intention | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Climate Advocacy | |||

| Data Privacy-Conscious Marketing | 0.758 | ||

| Regenerative Tourism Intention | 0.556 | 0.47 | |

| Social Moral Licensing | 0.088 | 0.103 | 0.227 |

| Original Sample (O) | Sample Mean (M) | Standard Deviation (STDEV) | T Statistics | p Values | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Climate Advocacy -> Regenerative Tourism Intention | 0.293 | 0.277 | 0.063 | 4.624 | 0.000 |

| DPCMxCA -> Regenerative Tourism Intention (Moderating effect) | 0.14 | 0.149 | 0.043 | 3.271 | 0.001 |

| Data Privacy-Conscious Marketing -> Regenerative Tourism Intention | 0.182 | 0.188 | 0.066 | 2.742 | 0.003 |

| SLMxCA -> Regenerative Tourism Intention (Moderating effect) | 0.105 | 0.123 | 0.042 | 2.523 | 0.006 |

| Social Moral Licensing -> Regenerative Tourism Intention | 0.172 | 0.173 | 0.031 | 5.575 | 0.000 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Zaman, U. Guardians of the Green: Exploring Climate Advocacy, Data Privacy-Conscious Marketing, and Social Moral Licensing in Regenerative Tourism in Hawaii. Sustainability 2024, 16, 10297. https://doi.org/10.3390/su162310297

Zaman U. Guardians of the Green: Exploring Climate Advocacy, Data Privacy-Conscious Marketing, and Social Moral Licensing in Regenerative Tourism in Hawaii. Sustainability. 2024; 16(23):10297. https://doi.org/10.3390/su162310297

Chicago/Turabian StyleZaman, Umer. 2024. "Guardians of the Green: Exploring Climate Advocacy, Data Privacy-Conscious Marketing, and Social Moral Licensing in Regenerative Tourism in Hawaii" Sustainability 16, no. 23: 10297. https://doi.org/10.3390/su162310297

APA StyleZaman, U. (2024). Guardians of the Green: Exploring Climate Advocacy, Data Privacy-Conscious Marketing, and Social Moral Licensing in Regenerative Tourism in Hawaii. Sustainability, 16(23), 10297. https://doi.org/10.3390/su162310297