1. Introduction

Fairs are large-scale events that provide a platform for businesses operating in various sectors to exhibit and promote their products and services, thereby enabling them to connect with potential customers and business partners [

1]. According to Comas and Moscardo [

2], fairs facilitate the interaction and exchange of information among participants and visitors. In the context of a rapidly globalizing world, the number of international fairs is increasing, and their scope is expanding in almost every sector. In the field of education, education fairs play a significant role in students’ decision-making processes regarding their career plans, influencing the sector as a whole [

3] and enabling service providers to establish effective one-to-one communication with students [

4]. Moreover, education fairs facilitate the presentation of a comprehensive range of alternatives to participants, thereby enabling students to gain insight into the distinctive constraints and potentialities associated with each option [

5]. In addition, education fairs play an instrumental role in facilitating international student mobility, serving as a pivotal instrument for universities seeking to gain access to these markets [

6]. It is of the utmost importance to select appropriate locations for education fairs in order to maximize success. In particular, locations that are accessible to large educational institutions and have a high international student demand serve to increase the effectiveness of fairs [

7,

8]. International education fairs can help reach students from underdeveloped and developing countries who want to study abroad but lack access to information and opportunities, thus supporting educational equality. In addition, more students from underdeveloped and developing countries can study and work in developed countries, which can create greater awareness of sustainability in these people and spread sustainability awareness and education on a global scale. This can also provide greater social benefits in the long term.

National policies and international agreements need to be developed and implemented for sustainable development. International fairs are organizations where businesses with different cultures come together through international agreements. The increase in international student mobility as a result of international education fairs organized in different countries has led to a rise in organizations and companies that facilitate educational fairs across various global locations. This trend is particularly pronounced in underdeveloped and developing countries, where there is a growing demand for student mobility. Consequently, selecting suitable locations for future events poses a complex challenge that requires careful evaluation of multiple factors. The selection of an appropriate location for educational fairs necessitates a comprehensive assessment of various criteria, including the needs of participants, geographical and demographic factors, local support opportunities, and the quality of the region’s educational infrastructure [

9]. An inappropriate choice of location may have a detrimental impact on participation rates, increase logistical costs, and create incompatibility with the target audience [

10]. The objective of this study is to examine the decision-making process involved in determining the location for international education fairs, which is inherently challenging and involves a multitude of factors. The study focuses on a fair company operating in Türkiye that is faced with the decision of selecting a new fair location. The investigation entails a comprehensive analysis of the suitability of five alternative countries, which were previously identified by the company as potential locations. In the study, the IVN Fuzzy TOPSIS method was used to determine the optimum location selection. The interval-valued neutrosophic fuzzy approach is a sophisticated mathematical method that can be used to address uncertainty and complexity in decision-making processes. It builds upon traditional fuzzy logic and neutrosophic set theory, offering a more flexible representation of data. In IVNF sets, each element is defined by three membership degrees: truth (T), indeterminacy (I), and falsity (F). These are represented as intervals within the range of 0 to 1. This structure allows for a more comprehensive assessment of information, as it captures the inherent ambiguity and conflicting evidence in complex systems. The most accurate decision-making process is one that is informed by expert input and provides a framework for implementing a transparent and fair decision-making process. The optimization of fair site selection ensures the efficient use of resources and increases the fairness, transparency, and inclusiveness of decision-making processes.

In scenarios involving the selection of complex locations, it is recommended that a primary region, typically a country or city, be initially identified in order to facilitate the subsequent selection of an appropriate venue for events [

10,

11]. Once the general region has been identified, specific venues, such as hotels or convention centers, are selected based on the requirements of the event in question. In selecting countries for events, companies prioritize those that demonstrate a commitment to long-term fair activities, and then identify specific areas or cities for the events. The process is complex and influenced by a number of variables, including the characteristics of the manager, their prior experiences, and external environmental conditions [

12]. In order to guarantee effective decision-making in this context, it is essential to adopt a comprehensive approach that addresses the multifaceted nature of the selection process in its entirety.

A review of the literature on the selection of international fair and congress sites reveals a significant focus on identifying the key attributes of meeting planners and on providing managerial inferences and suggestions based on these attributes. This is evident in the work of Fortin, Ritchie, and Arsenault [

9], McCleary [

13], Hall [

14], Var and colleagues [

15], Renaghan and Kay [

16], and Shaw, Lewis, and Khorey [

17]. The existing literature contains a limited number of studies on the selection of congress, exhibition, and fair site locations. For example, Perry, Foley, and Rumpf [

18], Harris and Jago [

19], Arcodia and Barker [

20], Li and Petrick [

21], Thomas, Hermes, and Loos [

22], Damm [

23], and Shone and Parry [

24] have conducted research in this area. A review of the literature reveals no existing studies on the topic of selecting locations for international education fairs. To address this gap in the literature, this study investigates the decision-making process for selecting appropriate locations for an international education fair organizer in Türkiye, examining five distinct country alternatives. The study makes a significant contribution to the existing literature in the following ways:

This research is the first to specifically focus on the decision-making process for location selection of international education fairs, thus addressing a previously unexplored area.

While there is no existing literature on the selection of locations for international education fairs, there are several studies on the selection of fair and exhibition locations, as well as convention locations, for a variety of industries. However, in contrast to the methodologies employed in these studies, this research introduces the use of interval-valued neutrophilic clusters as a novel approach. The method employed for analogous problems may serve as a case in point.

The process of selecting a site is a complex spatial decision-making problem, given the multitude of potential alternatives and the varying preferences of decision-makers [

25]. The Technique for Order of Preference by Similarity to Ideal Solution (TOPSIS) is a multi-criteria decision-making (MCDM) method initially proposed by Hwang and Yoon [

26] and is widely employed in location selection problems. It employs a ranking system based on the distances between alternatives and the ideal and negative ideal solutions. The assumption is that the optimal alternative is the one that is closest to the ideal solution and furthest from the negative ideal. The interval-valued neutrosophic fuzzy TOPSIS (IVN Fuzzy TOPSIS) method extends the classical TOPSIS approach by incorporating neutrosophic sets [

27], which facilitate the handling of uncertainties and indeterminacies inherent in decision-making processes. This method provides a more rigorous approach, particularly in instances where decision-makers have disparate evaluations and where concrete comparisons between alternatives are challenging. To this end, the IVN Fuzzy TOPSIS method, which was recently developed and is an effective method for decision-making under uncertainty and imprecision [

28], was employed in this study.

The following section presents an analysis of the current situation and future predictions regarding international student mobility. The section begins with an analysis of international student mobility statistics. Subsequently, a review of the literature on the issue of selecting locations for international education fairs is presented. Finally, it examines the methods utilized in this process. The third section of the study presents the methodology employed, while the fourth section elucidates the problem addressed. The fifth section provides a detailed account of the experimental study and presents the findings obtained. Furthermore, this section presents the results of a sensitivity analysis. The discussion and conclusion section presents the limitations of the study, examines the findings, and analyzes the results and decision criteria in detail. This section also addresses the success of the method and presents suggestions for future studies.

2. Literature Review

In recent years, international student mobility has experienced a notable increase, largely driven by the processes of globalization and the diversification of educational opportunities [

8]. This phenomenon not only contributes to students’ personal and academic growth but also represents a crucial economic factor for many countries. In particular, developing and less developed countries have witnessed a pronounced surge in outward student mobility, as students pursue superior educational prospects abroad. In recognition of the economic benefits that international students bring, governments are increasingly adapting their education systems to attract such students [

29]. Ultimately, international student mobility has become a strategic element that fosters cultural exchange and economic development, benefiting both individuals and nations.

A review of the data on student mobility globally reveals a significant increase in the number of international students. The growth of the global economy has been accompanied by an increase in international student mobility, as evidenced by the correlation between the two variables. While there were 2 million international students in 1998, this figure had risen to 6.4 million by 2020 [

30]. Despite the global impact of the SARS-CoV-2 pandemic, which precipitated a decline in international student mobility during the 2021 academic year, projections indicate a long-term recovery in demand for international student mobility. The Institute of International Education (IIE) Outlook 2030 report [

31] anticipates that this figure may reach approximately 10 million. A number of countries, including the United States of America, the United Kingdom, and Australia, are particularly attractive to international students. Forty percent of international students pursue their studies in Europe, which is the largest region for student mobility worldwide [

32]. A review of student mobility and international student data from 2022 reveals that North America and Western Europe collectively host 49% of international students, yet these regions account for only 13% of all mobile students [

7]. A substantial proportion, exceeding 50%, of international student mobility is attributable to Asia. China and India, in particular, are the main sending countries [

8]. However, the expectation of a deceleration in the rate of increase in the number of middle- and high-income households in China by 2030 (Guillerme [

8]), the anticipated demographic declines and economic deceleration, and China’s endeavors to develop its own universities (Arora and Baradiya [

6]) are regarded as indications that the rate of students pursuing studies abroad will decline. Nevertheless, projections indicate that Asia and the Middle East will continue to emerge as prominent destinations and sources of international student mobility in the near future. It is projected that the proportion of the population in Africa that is younger than 25 years of age will reach 33% by 2050, representing a doubling of this age group relative to the current population size [

7]. This situation demonstrates that Africa will assume a significant position in the future of international student mobility. Emerging markets such as Indonesia, Vietnam, Bangladesh, and the Philippines have significant potential for growth in student mobility. In addition, countries such as Türkiye, Brazil, and Mexico are among those with elevated macroeconomic risk. While these countries demonstrate potential for growth in student mobility, economic uncertainties and fluctuations in exchange rates may impede the realization of this potential [

31]. Upon examination of the recently prepared reports on international student mobility, such as [

6,

8,

30,

31,

32], it becomes evident that international student mobility will experience an uptick in the near future, particularly in Asia, Africa, and the Middle East. The increasing demand for international student mobility has led to an expansion of activities at international education fairs. Such events serve as vital resources for students contemplating the pursuit of studies abroad. These fairs provide students with direct access to university representatives, enabling them to obtain information on programs, scholarships, and admission requirements, thereby facilitating informed decision-making. Furthermore, education fairs facilitate networking, disseminate information regarding scholarship opportunities, and provide students with exposure to diverse cultures, thereby enhancing their overall experience. For the organizers, the choice of a suitable venue and country is a crucial strategic decision.

The fair and exhibition industry plays an integral role in the economy, drawing large crowds to facilitate the dissemination of current information about various sectors, promoting and selling products and services, and negotiating agreements and contracts related to the sector and companies [

33,

34]. The establishment of fair organizations in a multitude of geographical locations has the potential to facilitate the formation of a more inclusive and understanding society, as well as to contribute to the advancement of social justice. This is accomplished by fostering cross-cultural awareness and collaboration. The formation of new collaborative relationships and the injection of capital into existing enterprises have the potential to yield positive socio-economic outcomes, as evidenced by previous studies. The expansion of the event industry has resulted in an increased need for collaborative endeavors between event organizers and academic institutions, with the objective of enhancing efficiency and effectiveness [

35]. The process of preparing and presenting a fair or an exhibition event comprises a series of steps that every organization should undertake in order to maximize profits from exhibition activities prior to the event. Gębarowski [

3] identifies eight stages in this process: determining the goals of the exhibition activity, selecting fairs that will facilitate the achievement of the set goals, setting the budget of the exhibition event, refining the presentation concept of the offering alongside design and delivery of the exhibition, selecting and training the members of the exhibition team, preparing promotional materials, and participating in fairs and follow-up activities. In fair, exhibition, and convention organizations, the selection of an appropriate location is a crucial strategic decision that directly affects the success of the event [

10]. Fortin and Ritchie [

36] asserted that the selection of an event’s location is a pivotal decision that can vary based on the organization’s membership structure, past experiences, and environmental conditions.

An education fair is a commercial activity held at the same location on a regular basis. These events serve as a platform for disseminating information and promoting sales among prospective students regarding educational institutions, academic programs, and study abroad options in various countries and cities. Education-related congresses and conferences are activities that are primarily focused on the dissemination of information and are held in different locations on an annual basis. They are not as heavily influenced by commercial interests as other types of events. A review of the literature reveals a predominant focus on the success of education fairs and congresses, with numerous studies conducted in this area. These include works by Perry, Foley, and Rumpf [

18], Harris and Jago [

19], Arcodia and Barker [

20], Li and Petrick [

21], Thomas, Hermes, and Loos [

22], Damm [

23], and Shone and Parry [

24]. Furthermore, although a significant body of literature exists on the location selection for fairs and exhibitions (for references, see Crouch and Ritchie [

10]; Chacko and Fenich [

37]; Choi and Boger [

38]; Taylor and Shortland-Webb [

39]; Wu and Chen [

40]), there is a lack of research specifically addressing the site selection of educational fairs. The extant literature on the location selection of conventions and exhibitions (see, for example, Crouch and Ritchie [

10]; Chacko and Fenich [

37]; Choi and Boger [

38]; Taylor and Shortland-Webb [

39]; Wu and Chen [

40]; Jo et al. [

41]; Suwannasast [

42]; Nwobodo et al. [

43]; Pavluković, Vuković, and Cimbaljević [

44]) does not address the location selection of educational fairs specifically. This study represents a potential preliminary contribution to the field.

The initial attempt at site selection modeling in congress and fair site selection was conducted by Fortin and Ritchie [

36]. This study developed a fundamental conceptual model for the site selection process, utilizing the extant literature on organizational purchasing behavior. This model was among the earliest studies to incorporate the factors influencing congressional site selection, underscoring the significance of attributes such as conference room quality, pricing, assistance, and local support [

45]. This model had a profound impact on the site selection literature, serving as a foundational reference point in numerous subsequent studies [

46]. Over time, new models have been developed, and different decision criteria have been considered in the location selection process. The site selection literature has demonstrated that factors such as price, local support, transportation facilities, and security are significant considerations in the selection of congress and fair sites [

47]. The model developed by Crouch and Brent Ritchie [

10] concentrated on the impact of variables on the site selection process and classified these variables into eight fundamental categories. This model represents a more sophisticated iteration of Ritchie’s previous work with Fortin, focusing on the factors that influence the decision-making process itself rather than the process itself. One such factor is the term “local support”, which underscores the significance of subsidies [

10]. In the updated model proposed by Comas and Moscardo [

2], the significance of budgetary and temporal constraints in the location selection process is underscored. Dipietro et al. [

48] underscored the significance of the “saleability” of the destination to the participants. Moreover, Nelson and Rys [

49] and McCartney [

47] asserted that security and political stability in the selected location are pivotal determinants in the location selection process.

In the context of recent studies conducted within the scope of education fairs, the work of Arumugam et al. [

4] stands out as a notable contribution. This study examined the critical success factors (CSFs) for education exhibitions organized in Malaysia. The objective of this study was to evaluate the impact of critical success factors on the effective organization of educational exhibitions. It was asserted that project management, event promotion, and participant relations are particularly crucial to the success of the exhibitions. Sangpikul [

50] attempts to address a gap in the existing literature on experiential learning regarding Meetings, Incentives, Conferences, and Exhibitions (MICE) in the education sector, with a particular focus on the exhibition sector. The study examines graduate students’ perceptions of their academic learning experiences and the development of work-related skills through an exhibition project. The findings indicate that students developed a comprehensive understanding of the exhibition industry while also acquiring fundamental competencies, including teamwork, planning, and coordination. Similarly, Schulze and Markovič [

5] underscored the significance of education fairs in the 21st century, examining the factors that influence the decision to attend fairs for both participants and visitors. In their assessment, the researchers posit that education fairs are likely to persist as a significant marketing instrument and may potentially evolve into hybrid formats. In a recent study, Player-Koro et al. [

51] examined the role of education fairs in public education governance, with a particular focus on the dynamics between private and public actors. Despite the abundance of research on education fairs, it is notable that there is no study in the existing literature on the site selection of educational fairs. This presents a significant challenge for those responsible for organizing such events. However, this same absence of research also presents a promising opportunity for those engaged in academic inquiry.

The choice of event location is a multifaceted problem with a number of variables, depending on the specific sector and the decision-maker in question. However, the factors that should be taken into account in this decision-making process can be evaluated with greater objectivity through the use of analytical models [

45]. The site selection problem is influenced by a multitude of competing factors and criteria [

52]. In order to determine these factors and criteria, it is first necessary to examine the factors used in the studies in the literature. Subsequently, all criteria should be examined by experts and decision-makers regarding the location selection problem in question. Finally, the criteria to be taken into consideration in the problem-solving process should be determined. The most frequently utilized methods in location selection problems are multi-criteria decision-making (MCDM) methods [

53]. MCDM is an approach that entails the evaluation of multiple and conflicting criteria with the objective of identifying the most appropriate solution [

54]. Some of the most widely used traditional methods are the ELECTRE method, introduced by Roy [

55], the Analytic Hierarchy Process (AHP), developed by Saaty [

56], the Technique for Order of Preference by Similarity to Ideal Solution (TOPSIS), first introduced by Hwang and Yoon [

26], the Preference Ranking Organization Method for Enrichment of Decision-Making Excellence (PROMETHEE), developed by Brans et al. [

57], and the Analytic Network Process (ANP), developed by Saaty [

58] after the AHP. Fuzzy-based methods have been developed over time with the use of fuzzy logic. These methods enhance the precision of the decision-making process by incorporating uncertainty and ambiguous data into the solution process [

28,

59,

60,

61]. In their literature study on location selection studies in different areas, Yap et al. [

53] found that fuzzy TOPSIS or ANP TOPSIS methods are used in the energy sector [

62,

63,

64] and in public site selection [

65]. In addition, fuzzy TOPSIS methods have been employed in the logistics [

66,

67,

68,

69,

70,

71] and some other fields [

59,

60,

61]. The new technique used in this study, the interval-valued neutrosophic (IVN) fuzzy TOPSIS method, offers notable advantages over the conventional TOPSIS methodology. It effectively addresses the challenges posed by uncertainty, vagueness, and indeterminate information. In contrast to the conventional TOPSIS approach, which assumes the availability of precise input data, the IVN Fuzzy TOPSIS methodology incorporates interval-valued and neutrosophic sets, thereby facilitating a more flexible representation of decision-makers’ preferences in circumstances where incomplete knowledge is a factor. This capability enhances the reliability and robustness of the decision-making process, particularly in complex environments with ambiguous or conflicting data, thereby improving the overall quality of the decision-making process.

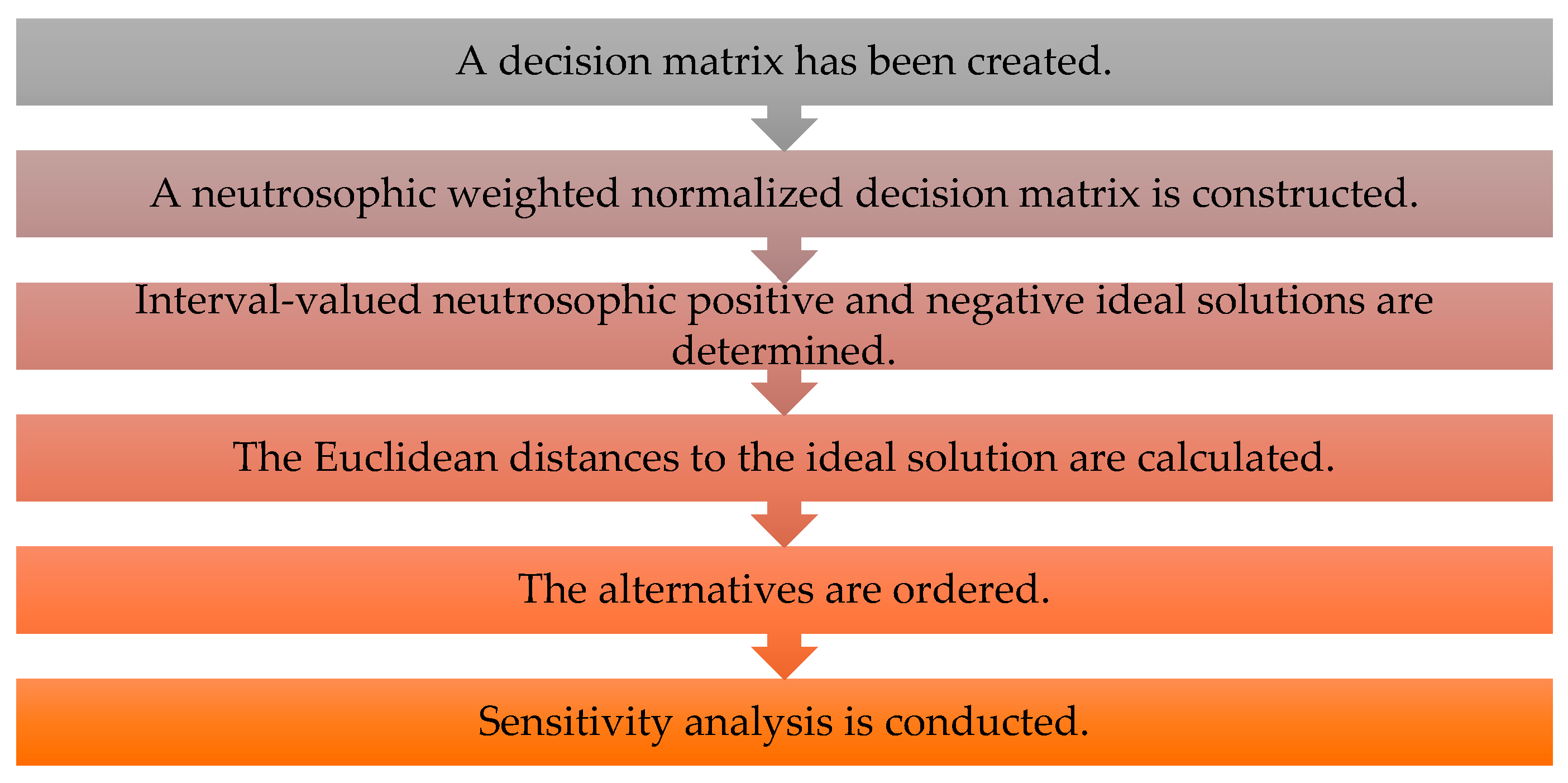

4. Problem Statement

According to data provided by UNESCO, in 2021, Türkiye was home to 51,146 students who were pursuing their studies abroad. The top three destinations for Turkish students, in order of popularity, were Germany, the United States of America, and the United Kingdom [

79]. It is projected that this figure will reach approximately 100,000 by the conclusion of 2025. In the 2023–2024 academic year, approximately 340 thousand international students from 198 countries were enrolled at Turkish universities [

80]. This has positioned Türkiye as one of the top 10 countries most preferred by international students worldwide [

81]. In response to the growing demand for international education and the increasing number of students from abroad seeking to study in Türkiye, the number of companies organizing international education fairs and overseas education consultancy firms is also rising rapidly.

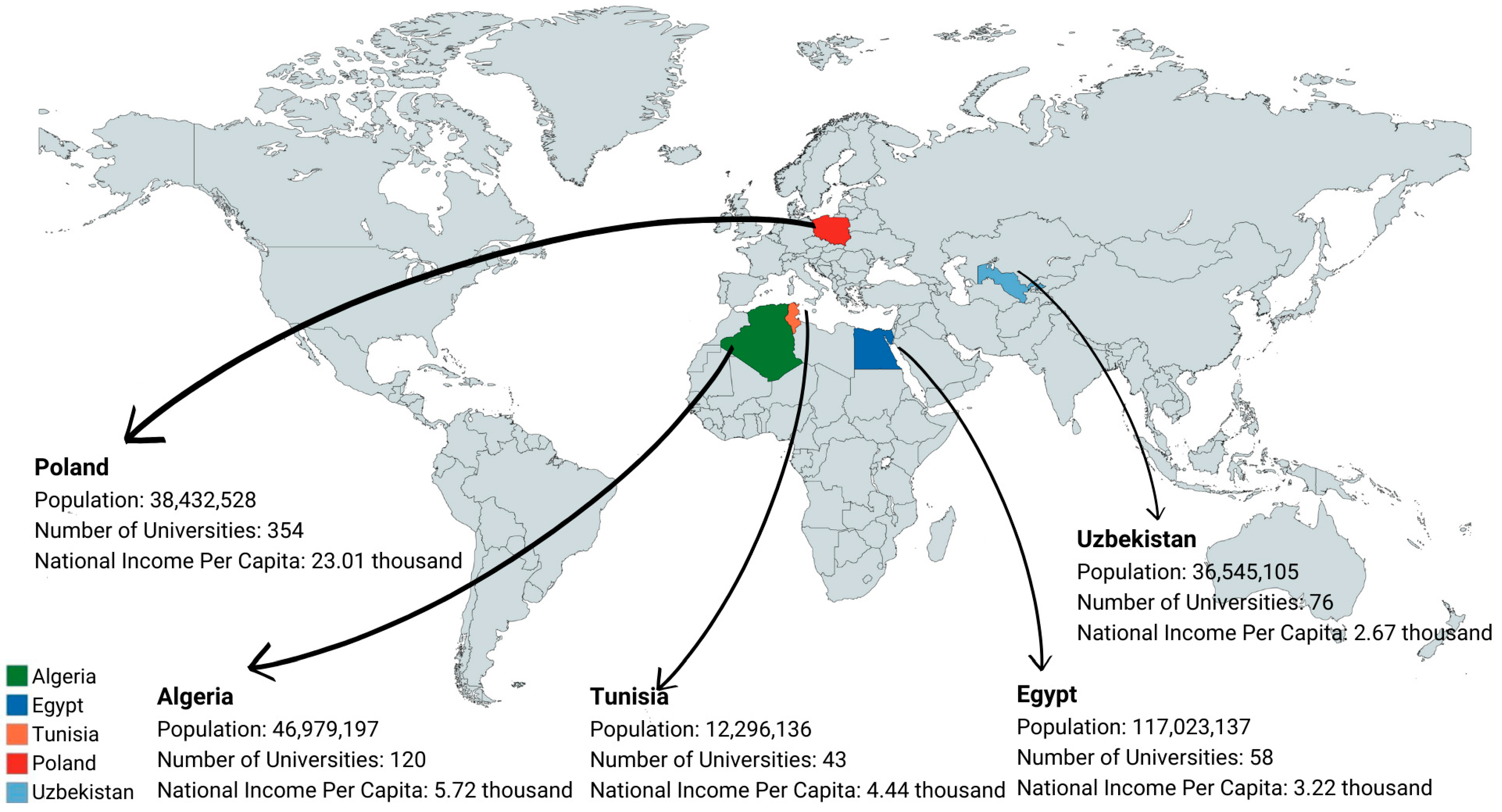

The increasing competition in the field of international student mobility and Türkiye’s growing attractiveness as a destination have led companies organizing education fairs to explore new markets abroad, investing substantial resources in the process. This study focuses on a real-world decision problem faced by one of Türkiye’s leading education fair companies, which manages international events in multiple countries. To address rising demand, the company decided to expand its fair activities to a new country, selecting among five alternatives: three in Africa, one in Europe, and one in Asia (as depicted in

Figure 2).

These candidate countries differ significantly in terms of geography, governance structures, and educational systems. Given that annual fairs would be held in the selected country, long-term stability, support for foreign organizations, and favorable economic conditions are crucial considerations. Additionally, student demand in each location plays a pivotal role in the decision. However, comparing these diverse alternatives directly, especially when criteria must be evaluated quantitatively, presents challenges. For instance, although Algeria has a larger population, Poland has nearly three times more universities. Similarly, Egypt’s population is about three times that of Uzbekistan and nine times that of Tunisia, which affects the demand for overseas education differently.

Moreover, variations in economic indicators can create conflicting priorities when choosing the ideal location for the fair. For example, while some indicators may favor economic growth, others might highlight the risks associated with investment. Given the complexity of this decision-making process, including elements of risk and uncertainty, selecting a methodology that incorporates linguistic evaluations and accurately handles uncertainty is essential. Using a precise decision-making approach can significantly enhance the process’s effectiveness, ensuring a more sensitive and well-founded final decision regarding the optimal country for hosting the education fair.

4.1. Dimensions Considered in Event Site Selection Research

To identify the key decision criteria, an initial review was conducted of studies examining education fairs and location selection. As no decision-making study on the selection of countries for international education fairs exists in the literature, the decision criteria used in studies on education fairs and conferences, as well as those employed in the selection of event locations, were examined in order to determine the decision criteria. Subsequently, the fundamental dimensions and the criteria associated with these elements were identified and evaluated collectively by three experienced professionals in the field of education fair organization. Through this process, the dimensions and criteria that were deemed most suitable for the selection of international education fairs were determined. A comprehensive review of the literature was conducted to identify studies on convention, exhibition, and fair location selection. The dimensions and criteria presented in these studies were then examined.

Table 2 presents a selection of notable studies published over the past ten years that have contributed to the existing literature on this topic.

In the selection of convention and exhibition centers, decision criteria are generally divided into two categories: center-specific and destination-specific factors. Breiter and Milman [

82] and Wu and Weber [

83] identified key center-specific factors like the quality of staff, available facilities, and ease of access. For destination-specific factors, studies highlight the importance of attractions, hotel options, and political stability [

84,

85]. Additionally, Jin et al. [

86] noted the significance of a supportive industrial environment, which can enhance the appeal of a location for specific types of exhibitions. Similarly, Boo and Kim [

87] found that cities with strong industry clusters, such as Boston for medical and high-tech sectors, are particularly attractive for related exhibitions.

Table 2.

Studies on international fair/convention/exhibition site selection in the last ten years.

Table 2.

Studies on international fair/convention/exhibition site selection in the last ten years.

| Author | Year | Title |

|---|

| [88] Huo, 2014 | 2014 | Meeting planners’ perception on convention destination attributes: Empirical evidence from six major Asian convention cities |

| [46] Park et al. | 2014 | The great halls of China? Meeting planners’ perceptions of Beijing as an international convention destination |

| [89] Chen | 2016 | Applying the Analytical Hierarchy Process (AHP) Approach to Convention Site Selection |

| [90] Lee et al. | 2016 | An Exploratory Study of Convention Destination Competitiveness from the Attendees’ Perspective: Importance-Performance Analysis and Repeated Measures of Manova |

| [91] Lee & Lee | 2017 | An exploratory study of factors that exhibition organizers look for when selecting convention and exhibition centers |

| [92] Van Niekerk | 2017 | Contemporary issues in events, festivals, and destination management |

| [40] Wu & Chen | 2017 | Applying ANP in Establishing a Decision-Making Model for the Destination Selection of Large-scale Exhibitions |

| [41] Jo et al. | 2019 | Destination-selection attributes for international association meetings: A mixed-methods study |

| [4] Arumugam et al. | 2019 | Critical Success Factors for Educational Exhibition Projects; Insights from Malaysia |

| [43] Nwobodo et al. | 2020 | Business Event Destination Determinants: Malaysia Event Organizers’ Perspective |

| [5] Schulze & Markovic | 2021 | The relevance of educational fairs in the 21st century – decision matrix for exhibitors and visitors to participate |

| [93] Handyastuti et al. | 2023 | Event Destination Selection Criteria: A Systematic Literature Review |

Lee and Lee’s [

91] study is among the most comprehensive on convention and exhibition center selection. The researchers aimed to identify the key factors that exhibition organizers consider when choosing sites. Using a mixed-methods approach, they created a framework with nine essential factors, divided into center-specific and destination-specific attributes. Center-specific factors include (1) C and E center accessibility, (2) C and E center image, (3) cost of the exhibition hall, (4) quality of C and E center staff members and service contractors, and (5) center facilities. Destination-specific factors focus on (1) the industrial environment of the C and E center site, (2) hotel accommodation, (3) the C and E center site environment, and (4) extra-exhibition opportunities that can attract visitors beyond the event itself. These factors emphasize the need for practical considerations like transportation access, local government support, and quality infrastructure to ensure that the location satisfies the requirements of organizers and attendees [

2,

10].

Arumugam et al. [

4] made a unique contribution by focusing specifically on education exhibitions, and exploring the critical success factors (CSFs) in this field through a survey in Malaysia. Their study identified key factors influencing the success of education fairs by applying Getz’s [

94] perspectives on events, which include environmental, community, economic, event programming, management, psychological, and political dimensions. This approach allowed them to assess how different aspects of event planning and execution affect outcomes in education exhibitions. In a more recent contribution, Handyastuti et al. [

93] conducted a Systematic Literature Review to analyze the criteria for selecting destinations for event tourism between 2013 and 2023. Their research identified a broad range of critical factors, such as infrastructure, accessibility, accommodation, safety, local support, cultural and recreational activities, event history, seasonal considerations, marketing and promotion, environmental sustainability, competitive advantage, and economic impact. These studies collectively provide a thorough understanding of what makes a destination appealing for various types of events, including conventions, exhibitions, and education fairs. These studies collectively underscore the complex and multifaceted nature of site selection in event management. The findings illustrate the significance of not only practical considerations, such as transportation and costs, but also the strategic congruence between the event’s theme and the local environment, including aspects of industrial synergy and regional support [

86,

87]. It is crucial for event organizers to comprehend these criteria in order to optimize both attendance and the overall success of the event.

4.2. Dimensions and Criteria Utilized in the Site Selection of International Education Fairs

In this study, a systematic review of all dimensions and criteria relevant to the selection of a location for an international education fair was conducted. This involved the incorporation of insights from the existing literature and input from experts working in the international fair organization company. The comprehensive analysis entailed a meticulous assessment of each potential criterion, ensuring its alignment with practical requirements and strategic objectives. After extensive deliberations, it was determined that the most suitable approach for addressing the location selection problem would be to utilize the specific dimensions and criteria outlined in

Table 3, which captures the essential factors for effective decision-making in this context.

In order to ensure that the study is based on a robust theoretical foundation in the process of determining the decision criteria, an examination was conducted of studies in the existing literature. While not within the purview of the education sector, studies on the determination of event locations in disparate sectors were also examined in the literature. In this context, the decision criteria used in studies of fair, exhibition, and convention locations were examined with experts in the context of the education fair location determination problem. In this context, the criteria to be utilized in the study were determined through a collaborative process with experts, utilizing the criteria employed in event location selection studies. Consequently, C1 and C2, as illustrated in

Table 3, were identified as specific criteria for this study, while the remaining nine decision criteria were derived from the criteria utilized in disparate studies.

The decision problem entailed the selection of a country from a set of five options: Egypt, Poland, Tunisia, Algeria, and Uzbekistan. This selection was based on five key dimensions and 11 decision criteria, which were derived from both expert consultation and a literature review. The initial dimension, “Population and Demand for Education Abroad”, assesses the prospective market for international education. It evaluates the prospective student population aged 16–24 who are interested in pursuing studies abroad, as well as the working population involved in business and seeking international education. A high evaluation in this dimension indicates a robust demand and market potential, which makes it a criterion oriented towards benefits. A larger demographic interested in overseas education is indicative of a higher probability of attendance and engagement at the education fair.

The second dimension, Potential of Educational Institutions to Meet Education Demand, assesses a country’s capacity to fulfill its educational needs. This dimension encompasses the ability of local universities to offer undergraduate and graduate programs, in addition to the potential for excellence in language training. A well-developed education system may result in a reduction in the number of local students pursuing education abroad, which could subsequently diminish the appeal for fair organizers. Accordingly, the criteria in this dimension are classified as cost-oriented, reflecting the potential economic implications of local educational offerings.

The third dimension, Economy, Politics, and Supports, is crucial for hosting successful international events. This dimension encompasses criteria such as per capita income and general welfare level, thereby ensuring that prospective participants can afford to engage in international education. Furthermore, the evaluation considers the political climate and the level of trust in governance, as political stability is a crucial factor in attracting both exhibitors and attendees. The role of government incentives for international education is also significant, as countries offering scholarships can enhance its attractiveness to prospective students.

The fourth dimension, Investor Support and Organization Support, assesses the degree to which the host country is favorable for the organization of events and investment. It assesses the extent of assistance provided to foreign investors, including logistical support and financial incentives, as well as the ease of conducting fairs and promotional activities. A robust regulatory and logistical framework is a prerequisite for the successful organization of large-scale events such as education fairs. This dimension is defined as benefit-oriented, as evidenced by the fact that high scores in these criteria indicate a supportive environment for event organization.

The Competitors’ Service Level dimension is the final component of the evaluation framework. It assesses the competence and quality of local educational service providers. It assesses the capacity of local companies to meet the demands of international students and the overall quality of the services provided by these institutions. The presence of robust local services facilitates international student mobility, yet it also signifies intense competition for fair organizers seeking to enter the market. Consequently, the criteria within this dimension are classified as cost-oriented, reflecting the economic challenges that new market entrants may face.

The framework for education fair site selection, based on these five dimensions and 11 criteria, aims to ensure that the chosen location not only has a robust demand for international education but also provides the necessary infrastructure, economic stability, and government support. By thoroughly assessing these factors, the organization can increase the likelihood of hosting a successful event that attracts a wide range of international education providers and prospective students. This systematic approach allows for a well-informed decision that balances both market potential and logistical feasibility, ensuring that the education fair achieves its objectives in a competitive international environment.

5. Analysis and Results

The perspectives of three experts involved in the international decision-making process were gathered through face-to-face interviews. During these interviews, the experts provided linguistic evaluations of the criteria and options for selecting an international education fair location. The experts were assigned varying weights based on their professional experience and international exposure. In accordance with the recommendations of the senior management team, the weights assigned to the first and second experts were set at 0.30 each, while the third expert was assigned a weight of 0.40. In the initial phase of our study, three experts conducted individual assessments, evaluating the criteria and alternatives independently. Subsequently, they convened to discuss and compare their evaluations, thereby facilitating an exchange of ideas and ensuring consistency across their judgments. This collaborative review process enabled the experts to refine their individual assessments and address any potential inconsistencies. The objective of this iterative approach was to enhance the validity of the linguistic term scaling and its implementation in the model, thereby ensuring a robust and justified representation of uncertainty.

Table 4 illustrates the rating scale utilized for these linguistic evaluations. For instance, the third expert assigned criterion 2 a rating of “VH” (Very High), indicating its high level of importance.

Table 5 illustrates the relative importance of the alternatives according to the criteria established by the first, second, and third experts, as represented in a decision matrix. To illustrate, the second decision-maker assigned a rating of H to alternative 2 for criterion 2. This value is indicative of a high importance weight in linguistic terms. The linguistic values in

Table 5 are the data obtained as a result of expert opinions. There are nine linguistic values here. The importance level of each criterion to the alternative was determined by one of nine different linguistic values ascertained by asking the expert.

Aggregated decision matrices were created for each expert based on their linguistic evaluations of all criteria and alternatives.

Table 6 shows the combined IVN decision matrices specially prepared for DM-1 in 11 criteria. In this process, linguistic evaluations were converted to numerical values using the INWAA operator defined in Definition 1. While calculations were made in the formula used in the INWAA operator, basic mathematical operations were performed according to the equations in Definitions 4 and 5. Additionally, multiplication and subtraction operations between two neutrosophics were calculated according to the equations determined as neutrosophics. This conversion resulted in six numerical values for each criterion. The aim of this step is to convert qualitative evaluations into quantitative data and to create the decision matrix that determines the starting point of the methodology.

Table 6 presents the aggregated decision matrix, constructed by applying the scale defined in the IVN decision matrix shown in

Table 1, in conjunction with the formula of the INWAA operator. The upper and lower bounds of all membership functions were derived numerically through the “if” operator, thus ensuring precision. For example, with regard to criterion 1, the determination of lower and upper values permitted an accurate representation of uncertainties related to the decision. This method facilitated a systematic approach to aggregating expert evaluations, thereby enhancing the reliability of the decision-making process through detailed quantitative analysis.

Table 7 displays the IVN decision matrices for the alternatives based on each criterion, representing the initial step of the IVN Fuzzy TOPSIS method. The results for criteria 1 and 11 are provided in this table. Experts’ linguistic evaluations were converted into numerical form, yielding six values for each cell. The table also shows the lower and upper limit values for each of the three parameters used in neutrosophic calculations. The equations presented in Step 1, Definitions 1, 3, 4, and 5 were instrumental in the generation of

Table 7 and

Table 8.

Table 8 shows the aggregated weighted IVN decision matrix. Here, a new decision matrix is created by multiplying the weights of the criteria, which is one of the stages of the IVN Fuzzy TOPSIS method, with the decision matrix created in the first stage.

Table 9 presents the positive ideal values of the neutrosophic criteria, calculated using Equation (7) in the third step of the IVN Fuzzy TOPSIS method. The table displays the TL, TU, IL, IU, FL, and FU values for each criterion.

The decision matrix of neutrosophic negative ideal solutions is shown in

Table 10. It is constructed using Equation (8) in Step 3 of the IVN Fuzzy TOPSIS method.

Euclidean distances were calculated using Equation (9) in the fourth step of the IVN Fuzzy TOPSIS method stages, shown in

Table 11. At this stage, the six linguistic values in each cell in the decision matrix were converted into a single linguistic value with the help of neutrosophic operations.

Table 12 presents the calculations for negative Euclidean distances and average values of the alternatives, following a similar approach as in the previous table. This table was derived using Equation (9) from Step 4 of the IVN Fuzzy TOPSIS method.

Table 13 illustrates the final stage of the IVN Fuzzy TOPSIS method, where alternatives are ranked. To obtain this ranking, the revised proximity values in Equation (10) in Step 5 are calculated. According to the results in this table, alternative number 2 is identified as the best option, while alternative number 3 holds the lowest position.

In order to test the accuracy and reliability of the method used at this stage, the results of the sensitivity analysis are given. Sensitivity analysis helps to measure the effectiveness of the method based on the change of only a certain parameter. Here, each of the linguistic values in

Table 3 is changed in order, and the new scores of the alternatives are tested. The structure of the sensitivity analysis used here is shown in

Table 14.

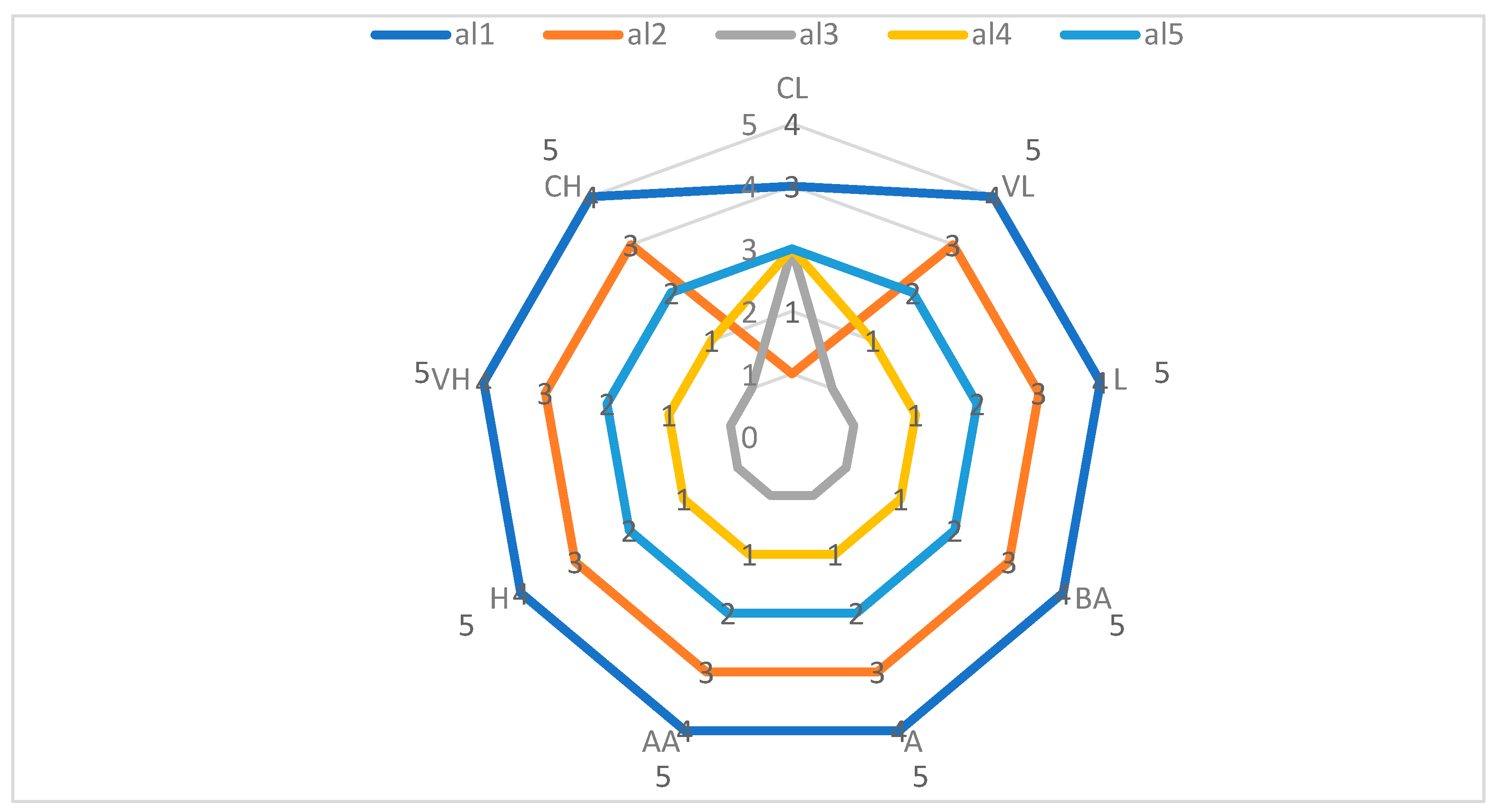

At this stage, the results of the sensitivity analysis conducted using the IVN Fuzzy TOPSIS method are presented graphically. As illustrated in

Figure 3, the ranking of alternatives reveals important insights. For instance, the ranking for the CL value of alternative 1 is positioned at 4, whereas the sequence for other linguistic values is at 5. Similarly, alternative 4 has a ranking of 3 for the CL value, while its other linguistic values rank at 1. This pattern of ranking for the remaining alternatives can also be observed.

At this point, the sensitivity analysis was conducted specifically for criterion 1. The slight variations observed in the current rankings highlight the accuracy and reliability of the method employed. The graph demonstrates that these slight variations in linguistic values across all alternatives enhance the reliability of the approach. During the sensitivity analysis, one parameter’s value is altered while the others remain constant, allowing for an assessment of how these changes impact the current rankings. In essence, the linguistic values for each alternative were sequentially modified, the model was rerun, and the resulting scores for the alternatives were documented to establish their ranks accordingly. This meticulous process highlights the robustness of the method in evaluating decision-making scenarios.

6. Discussion and Conclusions

6.1. Limitations

It should be noted that the findings of this study are subject to certain limitations. Firstly, in the context of the fair location selection decision problem, the decision-maker is a company operating in Türkiye, and the fair location alternatives are those determined by the company in accordance with its current strategies. Secondly, in the context of the presented problem, three expert opinions were elicited, with one expert demonstrating a greater degree of experience than the others. Accordingly, the weight assigned to one expert was 0.40, while the weights assigned to the other experts were 0.30. Thirdly, given the expertise of the evaluators in this field, their assessments were considered to be a reliable source of information. It is, however, possible that the results may vary depending on the evaluations of different experts. Fourthly, the expert evaluations were conducted in parallel with the study, and thus reflect the current status of the alternative country location options. It should be noted that the conclusions presented may be subject to modification in light of future developments. Finally, the neutrosophic approach presented in the study is a powerful tool for modeling uncertainty and conflicting information; however, it is not without its inherent limitations. The management of the three dimensions of truth, falsity, and indeterminacy can introduce significant complexity, particularly when applied to large datasets or systems with numerous variables. This may result in complications with regard to the analysis process. Furthermore, the approach’s reliance on expert judgments renders it susceptible to subjectivity. Such reliance on individual assessments may introduce biases, thereby affecting the consistency and reliability of evaluations across different contexts.

6.2. Discussion

Poland, one of the alternative countries under consideration for the international education fair venue, has emerged as a favored destination for students on account of its superior educational standards and relatively low tuition fees in comparison to those in Western Europe. Moreover, the increasing number of students from this country who travel to other European countries and the United States of America on an annual basis indicates that this country is a prominent player in the realm of student mobility. Similarly, Egypt, with its rich history and cultural importance, attracts students from various backgrounds, especially from neighboring African countries, who are seeking both educational opportunities and a culturally immersive experience. In recent years, Algeria and Tunisia have implemented notable initiatives with the objective of achieving political and economic stability in these regions. It is clear that there has been a notable increase in the demand for foreign language education in these countries on an annual basis. Among the alternatives, Uzbekistan, which is undergoing rapid development, is actively promoting the education sector, which has resulted in an increasing number of international partnerships and programs designed to attract foreign students. The countries of Uzbekistan, Algeria, and Tunisia, with their rich cultural heritage and developing educational frameworks, offer unique opportunities for students, especially in fields such as the humanities and social sciences. Moreover, these countries have a considerable number of students with the aspiration to pursue studies in science, engineering, and language education abroad.

Upon examination of the evaluations provided by the experts involved in the study, it becomes evident that the criteria C1, C2, C5, and C6 are more effective in the selection of suitable locations in comparison to other criteria. This indicates that the “population and demand for education abroad” dimension and the “economy, politics, and support” dimension are more efficacious in the decision-making process than other criteria. Given that the primary objective of education fairs abroad is to increase the number of registrations for international education programs, it is evident that criteria pertaining to demand potential are of significant importance. As evidenced by the expert evaluations, the economic potential and political stability of a country are highly effective in determining the suitability of a fair location. However, while the criteria of per capita income and individual welfare level, political climate, and environment of trust are regarded as vital elements, the incentives and supports provided for education abroad are considered to be of relatively lesser importance by the decision-makers of the fair organization. Upon examination of all evaluations, it becomes evident that C8, C9, C10, and C11 emerge as relatively less pivotal criteria in the decision-making process pertaining to the fair. Consequently, the evaluation of the aforementioned criteria revealed that investor and organizational support, the service level of competitors in that country, the demand potential for overseas education in the countries, and the economic and political conditions of the countries were deemed to be of relatively lesser importance.

The high ranking achieved by Poland in the assessment of educational fair attractiveness relative to other countries suggests that it is a more appealing option than other potential destinations in terms of meeting a range of criteria. Although Poland occupies the third position in the ranking of population size, it is in fact the country with the highest number of universities. In recent years, there has been a notable increase in the number of mobile students in Poland. When the number of university students who have studied abroad and the number of individuals employed in business who have studied abroad are considered, it becomes evident that Poland has the potential to be evaluated similarly to Egypt, which has a much larger population, in the first criterion, “Potential of the student population between the ages of 16–24 with a demand for education abroad”, and the second criterion, “Potential of the working population taking part in business life and demanding education abroad”. With regard to population and demand for education abroad, Tunisia is particularly deficient in the first dimension, exhibiting a considerably smaller population and mobility potential than other countries. In terms of the second dimension, the potential of educational institutions to meet the educational demand, experts have indicated that Poland and Egypt have a higher potential. However, this dimension is constrained by cost-oriented criteria pertaining to the capacity of existing universities in the country to meet the demand for undergraduate and graduate education, as well as the ability of educational institutions in the country to meet the needs of students and employees with regard to language education. The high potential in these areas may result in an increase in the number of competitors and, in the long term, may lead to a situation in which students who will pursue their studies abroad will be able to meet their educational demands in their own countries. Consequently, Tunisia, Algeria, and Uzbekistan, whose educational institutions are less capable of fulfilling the educational demands of the population, have been identified as more attractive markets in terms of these criteria. The third dimension, encompassing economic, political, and support factors, is of paramount importance for the continuity of investment. Notably, despite the presence of minor or major regional crises and conflicts in all alternative countries, it is anticipated that these countries will not engage in a substantial conflict or experience a political crisis in the near future. Upon examination of the evaluations within this dimension, it becomes evident that experts perceive Egypt to be comparatively disadvantaged in relation to other countries. Nevertheless, no notable discrepancy exists between the evaluations. In examining the criteria and evaluations pertaining to the fourth dimension, it becomes evident that Poland demonstrates a greater capacity for supporting prospective investors and facilitating their operations. In contrast, Egypt and Uzbekistan are perceived to offer more conducive conditions for foreign investors, particularly in comparison to Algeria and Tunisia. In the assessments of competitors in various countries, when the potential of companies providing education services abroad in the country to meet the needs and quality of their services are taken into consideration, it becomes evident that there are numerous companies in Poland that offer education abroad, and the service level is also higher. Given that Tunisia exhibits a lower potential than other countries in these cost-oriented criteria, it can be stated that it distinguishes itself in the selection of an appropriate location. The analysis further reveals that the selected countries not only meet the quantitative criteria of student populations but also exhibit qualitative aspects such as institutional partnerships, market trends, and economic factors that enhance their viability as locations for education fairs. The integration of these dimensions allows decision-makers to gain a comprehensive understanding of the potential of each country.

The utilization of neutrosophic methodologies in the selection of sites for international education fairs serves to illustrate their flexibility and efficacy in addressing complex decision-making challenges. While research directly applying neutrosophic methods to fair or exhibition site selection is currently limited, there is an expanding body of literature demonstrating their application across a variety of decision-making contexts [

95,

96,

97,

98]. These studies demonstrate the efficacy of neutrosophic approaches in evaluating multiple criteria, addressing the uncertainty, ambiguity, and variability inherent to such evaluations. The methodology employed in this study allows for a comprehensive assessment of a multitude of factors, including economic conditions, student mobility trends, and institutional support. It does so while accounting for the inherent uncertainty and variability inherent to these criteria. As a result, the selected location country is more likely to align with the diverse needs and expectations of all stakeholders, including educational institutions, students, and fair organizers. This, in turn, optimizes the success and relevance of the event location within the global education landscape. In the existing literature, it is evident that a variety of decision-making methods, including AHP-WASPAS [

95], CODAS [

96], SWARA, and EDAS [

99], have been employed in studies that adopt a neutrosophic approach. The suitability of each method may vary depending on the specific characteristics of the problem under consideration. The Technique for Order of Preference by Similarity to Ideal Solution (TOPSIS) method, employed in the present study, assesses the relative merits of alternatives in terms of their proximity to the ideal solution and their distance from the negative ideal solution. The integration of this approach with the IVN fuzzy approach ensures that each alternative is evaluated comprehensively, taking into account multiple criteria and their varying levels of importance. This equilibrium has facilitated a systematic and transparent decision-making process. The IVN Fuzzy TOPSIS method is particularly well suited for complex multi-criteria decision-making scenarios, particularly in the context of optimal location selection, by providing a flexible framework that can be adapted to a wide range of criteria with varying weights. This adaptability allows for the implementation of customized analyses that are compatible with the specific requirements of a particular project and stakeholder expectations.

The method can be developed by using different fuzzy sets for future studies. At the same time, results can be compared with more than one method. This study can be compared with other multi-criteria decision-making methods such as IVN fuzzy CODAS, IVN fuzzy EDAS, IVN fuzzy VIKOR, and IVN fuzzy AHP. Apart from this, the effectiveness of the method can be increased by evaluating the methods with hybrid approaches. The extent to which the results change can be observed by increasing the number of decision-makers used in the application part of the study. The method employed in this investigation can serve as an exemplar not only for the country selection of international educational fairs but also for event site selection in contexts where different organizations are involved.

6.3. Conclusions

The strategic selection of locations for international education fairs can facilitate the promotion of educational equity and contribute to sustainable development. Such fairs have the potential to reach a more diverse demographic of students, particularly those from underdeveloped or developing countries who lack access to information regarding opportunities for studying abroad. These fairs provide access to undergraduate, graduate, and language programs in developed countries, thereby enabling students to gain global competence, engage in cross-cultural exchange, and pursue personal development. In addition to the individual benefits, international education fairs contribute to broader socio-economic development. Students who undertake studies abroad frequently gain skills and knowledge that they subsequently apply in their home countries, thereby stimulating innovation and economic growth. Furthermore, international education fairs facilitate international collaboration and reinforce global partnerships in alignment with sustainability objectives. Thus, the optimal selection of locations for such events facilitates both educational equity and global development by ensuring maximum accessibility and impact. In selecting the optimal location for an international education fair, a complex decision-making process is often faced with numerous uncertainties. To address this challenge, a novel method was employed to eliminate these uncertainties and optimize the decision-making process.

This study employs the IVN Fuzzy TOPSIS method to address the complex decision-making process involved in selecting the most suitable locations for international education fairs. This study represents the preliminary examination of the issue of selecting locations for international education fairs, with a particular focus on the process of selecting locations for events. Additionally, this study presents a novel investigation of the decision-making process involved in selecting new locations for a fair company operating in Türkiye. Moreover, the neutrosophic approach has been employed for the first time in event organization location selection, thereby addressing a previously unaddressed gap in the literature. The final results of the case study indicate that Poland is the optimal choice for hosting international education fairs in the location country selection problem, followed by Egypt, Uzbekistan, Algeria, and Tunisia. This ranking underscores the considerable demand for international student mobility, the diversity of demand, and the distinctive attributes that render these countries attractive for fair organization companies.

In recent years, neutrosophic methods have been increasingly utilized in decision-making processes due to their capacity to address scenarios characterized by high uncertainty, complexity, and incomplete information. These methods are particularly efficacious when uncertainty, inconsistency, and contradictory data are present, as in the decision problem considered in this study, because they can accommodate degrees of accuracy, uncertainty, and inaccuracy in the analysis. In contrast to conventional decision-making methodologies, IVN Fuzzy TOPSIS facilitates a more comprehensive presentation of uncertain and ambiguous data. This results in more robust and reliable outcomes. This makes it a valuable tool in complex decision-making problems, such as the one presented here, where precise information may be difficult to obtain or where expert opinions may differ. Moreover, the IVN Fuzzy TOPSIS method is more computationally efficient than other methods, resulting in faster output. The adaptability of neutrosophic methods permits the integration of both qualitative and quantitative data, thereby enabling the implementation of decision-making processes in a multitude of real-world scenarios, such as the one under consideration here, where the decision criteria may be subjective or complex. Therefore, neutrosophic methods provide a comprehensive framework that can improve the quality of decisions in various applications and ensure that optimal choices are made even in the presence of uncertainty and incomplete information. The application of neutrosophic methods in the context of international education fair location selection has demonstrated their flexibility and effectiveness in addressing the multifaceted challenges inherent to decision-making in this domain. These methods provide a structured approach to evaluating various criteria, such as economic conditions, student mobility trends, and organizational support, while accounting for the inherent uncertainty and variability of these factors. This results in a more accurate prioritization of potential locations, thereby ensuring that the selected country location is compatible with the needs and expectations of all relevant stakeholders.

In conclusion, the findings of this study underscore the importance of a systematic approach to selecting locations for international education fairs. By leveraging neutrosophic methods, decision-makers can navigate the complexities and uncertainties inherent in this decision-making process. The ranked countries—Poland, Egypt, Uzbekistan, Algeria, and Tunisia—emphasize the significance of demographic trends, economic conditions, and institutional readiness in shaping the landscape of international education. Moving forward, further research is recommended to explore the long-term impacts of these fairs on student mobility and the educational outcomes in these regions. By continually enhancing the decision-making criteria and methodologies employed, fair organization companies can enhance their strategic positioning in the global education market and generate more precise decisions regarding the selection of new fair locations.