Linking Management Capabilities to Sustainable Business Performance of Women-Owned Small and Medium Enterprises in Emerging Market: A Moderation and Mediation Analysis

Abstract

1. Introduction

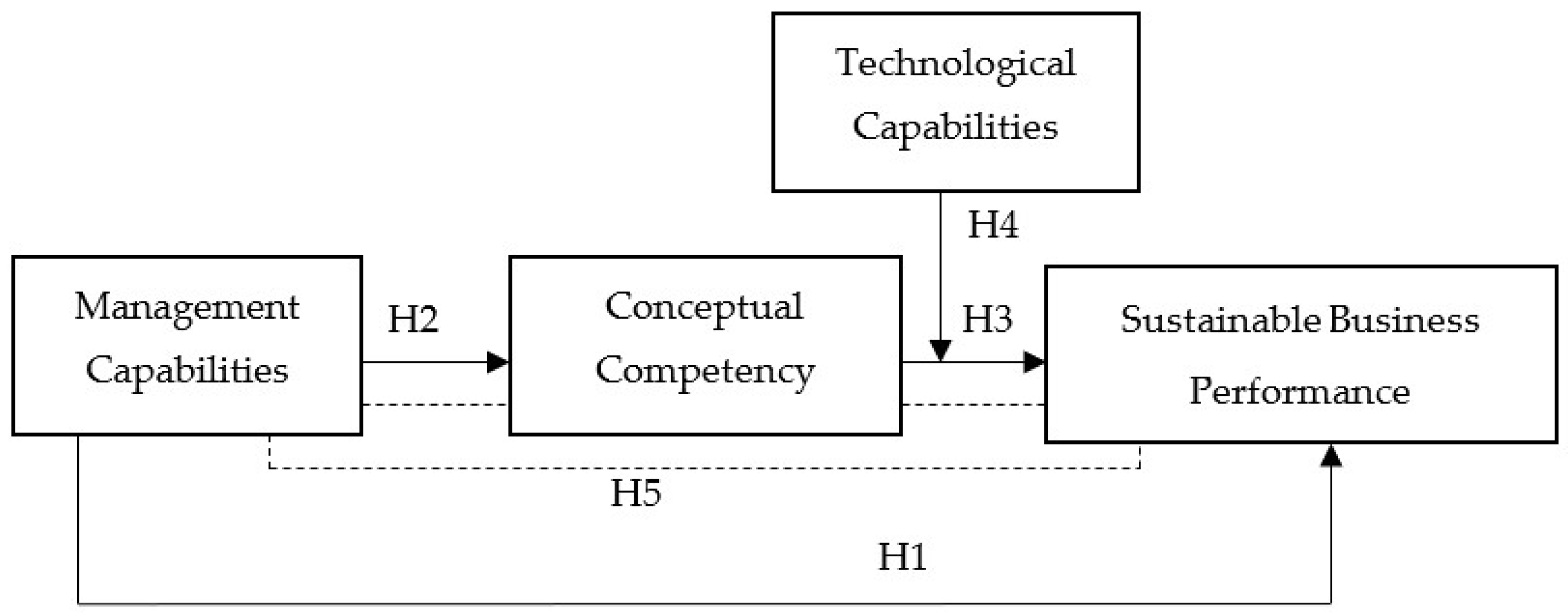

2. Literature Review and Development of Hypothesis

2.1. Women-Owned SMEs

2.2. Sustainable Business Performance

2.3. Leveraging Management Capabilities for Sustainable Business Performance

2.4. Relationship Between Management Capabilities and Conceptual Competency

2.5. Relationship Between Conceptual Competence and Sustainable Business Performance

2.6. Technological Capability as the Moderating Variable

2.7. Conceptual Competence Mediates the Relationship Between Management Capability and Sustainable Business Performance

3. Materials and Methods

3.1. Procedure and Participants

3.2. Variables and Instruments

3.3. Data Analysis Tools and Techniques

3.4. Common Method Variance

4. Results

4.1. Demographic Profile

4.2. Measurement Model (Reliability and Validity)

4.3. Structural Model and Moderation Analysis

4.4. Mediation Analysis

5. Discussion

5.1. Theoretical Implications

5.2. Practical Implications

6. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A

- a.

- My integrated logistics systems help me carry out better business

- b.

- My cost control capabilities help me carry out better business.

- c.

- My financial management skills help me carry out better business.

- d.

- My human resource management capabilities help me carry out better business.

- e.

- My accuracy in profitability and revenue forecasting helps me carry out better business.

- f.

- My marketing planning process helps me carry out better business.

- a.

- My skills in organizing and motivating people help me carry out better business.

- b.

- My skills in delegation of responsibilities help me carry out business effectively.

- c.

- My knowledge of my employees helps me in keeping my organization running smoothly.

- d.

- My skills in organizing and coordinating tasks support me in carrying out business effectively.

- e.

- I can effectively supervise, influence, and lead my employees to do better at my business.

- a.

- My new product development capabilities help me carry out better business.

- b.

- My manufacturing process capabilities help me carry out better business.

- c.

- Technology development capabilities help me carry out better business.

- d.

- My ability to predict technological changes in the industry helps me carry out better business.

- e.

- Production facilities of my business help me carry out better business.

- f.

- Quality control skills help me carry out better business.

- a.

- Net profit margin of our organization increased.

- b.

- Return on investment of our organization increased.

- c.

- Profitability growth has been outstanding.

- d.

- Profitability has exceeded our competitors.

- e.

- Overall financial performance has exceeded competitors.

References

- Ogbari, M.E.; Folorunso, F.; Simon-Ilogho, B.; Adebayo, O.; Olanrewaju, K.; Efegbudu, J.; Omoregbe, M. Social Empowerment and Its Effect on Poverty Alleviation for Sustainable Development Among Women Entrepreneurs in the Nigerian Agricultural Sector. Sustainability 2024, 16, 2225. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lagrasta, F.P.; Scozzi, B.; Pontrandolfo, P. Feminisms and entrepreneurship: A systematic literature review investigating a troubled connection. Int. Entrep. Manag. J. 2024, 20, 3081–3112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mwesigwa, R.; Alupo, S.; Nakate, M.; Mayengo, J.; Nabwami, R. The role of institutional support on female-owned business sustainability from a developing country’s perspective. J. Humanit. Appl. Soc. Sci. 2024. ahead-of-print. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moral, I.H.; Rahman, M.M.; Rahman, M.S.; Chowdhury, M.S.; Rahaman, M.S. Breaking barriers and empowering marginal women entrepreneurs in Bangladesh for sustainable economic growth: A narrative inquiry. Soc. Enterp. J. 2024, 20, 585–610. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Emon, M.H.; Nipa, M.N. Exploring the Gender Dimension in Entrepreneurship Development: A Systematic Literature Review in the Context of Bangladesh. Westcliff Int. J. Appl. Res. 2024, 8, 34–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alka, T.A.; Sreenivasan, A.; Suresh, M. Tracking the footprints of global entrepreneurship research: A theoretical exploration of landscape of global entrepreneurship through a bibliometric perspective. J. Glob. Entrep. Res. 2024, 14, 21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bangladesh Bureau of Statistics. Report on the Labor Force Survey of Bangladesh Institutions. 2024. Available online: https://bbs.portal.gov.bd/sites/default/files/files/bbs.portal.gov.bd/page/57 (accessed on 10 November 2024).

- Brodman, J.; Berazneva, J. Transforming opportunities for women entrepreneurs. Inf. Technol. Int. Dev. 2008, 4, 3–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brush, C.G.; Cooper, S.Y. An International Journal Female entrepreneurship and economic development: An international perspective. Entrep. Reg. Dev. 2012, 24, 37–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khan, S.N.; Khan, T.; Jilhajj, K. Investigating the role of banks in promoting women-owned micro and small businesses empirical evidence from an emerging economy. Bus. Strategy Dev. 2023, 7, e418. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gafur, I.; Islam, R. Performance of Female Entrepreneurs: An Organized Assessment of the Literature Addressing the Factors Affecting Bangladeshi Women Entrepreneurs’ Performance. Eur. J. Theor. Appl. Sci. 2024, 2, 215–224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salaudeen, N.H.; Sauri, B.G.K. Modelling the influence of culture on entrepreneurial competencies and business success of the women micro entrepreneurs in the informal sector of the economy. J. Apl. Manaj. Ekon. Dan Bisnis 2020, 5, 85–100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baharudin, M.H.; Rusok, N.H.M.; Sapiai, N.S.; Ghazali, S.A.M.; Salleh, M.S. Entrepreneurial Competencies and Business Success Among Women Entrepreneurs. Int. J. Acad. Res. Bus. Soc. Sci. 2021, 11, 302–310. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Agarwal, S.; Agrawal, V. Female entrepreneurship motivational factors: Analysing effect through the conceptual competency-based framework. Int. J. Entrep. Small Bus. 2023, 49, 350–373. [Google Scholar]

- Adner, R.; Helfat, C.E. Corporate effects and dynamic managerial capabilities. Strateg. Manag. J. 2003, 24, 1011–1025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eisenhardt, K.M.; Martin, J.A. Dynamic capabilities: What are they? Strateg. Manag. J. 2000, 21, 1105–1121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kearney, A.; Harrington, D.; Kelliher, F. Exploiting managerial capability for innovation in a micro-firm context: New and emerging perspectives within the Irish hotel industry. Eur. J. Train. Dev. 2014, 38, 95–117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lopa, N.Z.; Bose, T.K. Relationship between entrepreneurial competencies of SME owners/managers and Firm performance: A study on manufacturing SMEs in Khulna City. J. Entrep. Manag. 2015, 3, 1–12. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, Y.; Po Lo, H.; Zhang, Q.; Xue, Y. How technological capability influences business performance: An integrated framework based on the contingency approach. J. Technol. Manag. China 2006, 1, 27–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salisu, Y.; Julienti, L.; Bakar, A.; Malaysia, D. Technological capability, innovativeness and the performance of manufacturing small and medium enterprises (SMEs) in developing economies of Africa. IOSR J. Bus. Manag. 2019, 21, 56–61. [Google Scholar]

- Marei, A.; Abou-Moghli, A.; Shehadeh, M.; Salhab, H.; Othman, M. Entrepreneurial competence and information technology capability as indicators of business success. Uncertain Supply Chain Manag. 2023, 11, 339–350. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Poli, T.A. Mediating Role of Entrepreneurship Capability in Sustainable Performance and Women Entrepreneurship: An Evidence from a Developing Country. J. Ecohumanism 2024, 3, 2006–2019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carmeli, A.; Tishler, A. Resources, capabilities, and the performance of industrial firms: A multivariate analysis. Manag. Decis. Econ. 2004, 25, 299–315. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gillis, W.E.; Combs, J.G.; Yin, X. Franchise management capabilities and franchisor performance under alternative franchise ownership strategies. J. Bus. Ventur. 2018, 35, 105899. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koryak, O.; Mole, K.F.; Lockett, A.; Hayton, J.C.; Ucbasaran, D.; Hodgkinson, G.P. Entrepreneurial leadership, capabilities and firm growth. Int. Small Bus. J. 2015, 33, 89–105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kapetaniou, C.; Lee, S.H. Geographical proximity and open innovation of SMEs in Cyprus. Small Bus. Econ. 2018, 52, 261–276. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Katz, R.L. Skills of an Effective Administrator; Harvard Business Review: Boston, MA, USA, 1955; Volume 33, pp. 33–43. [Google Scholar]

- Ikupolati, I.; Adeyeye, A.; Olatunle, O.; Obafunmi, O. Entrepreneurs Managerial Skills as Determinants for Growth of Small and Medium Enterprises (SMEs) in Nigeria. J. Small Bus. Entrep. Dev. 2017, 5, 1–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mishra, M.; Deshpande, A.P. Investigating entrepreneurial competency in emerging markets: A thematic analysis. Int. J. Bus. Glob. 2023, 33, 245–265. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barbero, J.L.; Casillas, J.C.; Feldman, H.D. Managerial capabilities and paths to growth as determinants of high-growth small and medium-sized enterprises. Int. Small Bus. J. 2011, 29, 671–694. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ansah Ofei, A.M.; Paarima, Y. Exploring the governance practices of nurse managers in the Greater Accra Region of Ghana. J. Nurs. Manag. 2021, 29, 1444–1453. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ndrecaj, V.; Mohamed Hashim, M.A.; Mason-Jones, R.; Ndou, V.; Tlemsani, I. Exploring Lean Six Sigma as Dynamic Capability to Enable Sustainable Performance Optimisation in Times of Uncertainty. Sustainability 2023, 15, 16542. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mason, C.; Brown, R. Entrepreneurial ecosystems and growth oriented entrepreneurship. Final. Rep. OECD Paris 2014, 30, 77–102. [Google Scholar]

- Brush, C.G.; Greene, P.G.; Welter, F. The Diana project: A legacy for research on gender in entrepreneurship. Int. J. Gend. Entrep. 2020, 12, 7–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ploum, L.; Blok, V.; Lans, T.; Omta, O. Toward a validated competence framework for sustainable entrepreneurship. Organ. Environ. 2018, 31, 113–132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tjahjadi, B.; Soewarno, N.; Karima, T.E.; Sutarsa, A.A.P. Business strategy, spiritual capital and environmental sustainability performance: Mediating role of environmental management process. Bus. Process Manag. J. 2023, 29, 77–99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kalaivani, N.; Vijayarangan, R.; Chandra, S.; Karthikeyan, P. Women Entrepreneurs in Emerging Markets for Driving Economic Growth. In Real-World Tools and Scenarios for Entrepreneurship Exploration; IGI Global: Hershey, PA, USA, 2024; pp. 257–290. [Google Scholar]

- Andersson, I.; Raihan, A.; Rivera, M.; Sulaiman, I.; Tandon, N.; Welter, F. Handbook on Women-Owned SMEs. In Challenges and Opportunies in Policies and Programmes; Welter, F., Ed.; IKED: Malmö, Sweden, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Nziali, A.M.; Messomo, S.E.; Ongo, E.N. Does Usage of Financial Services influence the Growth of Women Owned Small and Medium Size Enterprises (SMEs) in Cameroon? Multidiscip. Int. J. Res. Dev. 2024, 5, 59–73. [Google Scholar]

- de Bruin, A.; Brush, C.G.; Welter, F. Introduction to the special issue: Towards building cumulative knowledge on women’s entrepreneurship. Entrep. Theory Pract. 2006, 30, 585–593. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sarfaraz, L.; Faghih, N.; Majd, A. The relationship between women entrepreneurship and gender equality. J. Glob. Entrep. Res. 2014, 2, 6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sehrawat, M.; Sharma, D. Female Entrepreneurship, Institutional Support and Accomplishments: A Review. In Women Entrepreneurship Policy: Context, Theory, and Practice; Dana, L.P., Chhabra, M., Eds.; Springer: Gateway East, Singapore, 2024; pp. 217–233. [Google Scholar]

- Chowdhury, A.-H.A. Socio economic impact of women entrepreneurship in Sylhet city, Bangladesh. Bangladesh Dev. Res. Work. Paper. 2018, 6, 526–533. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Allen, I.E.; Langowitz, N.; Minniti, M. Global Entrepreneurship Monitor. 2006 Report on Women and Entrepreneurship; Babson College: Wellesley Hills, MA, USA, 2007; Volume 3, pp. 54–88. [Google Scholar]

- Saikou, S.E.; Sanyang, S.E.; Huang, W.-C. Small and Medium Enterprise for Women Entrepreneurs in Taiwan. World J. Agric. Sci. 2008, 4, 884–890. [Google Scholar]

- Meng, L.; Qamruzzaman, M.; Adow, A.H.E. Technological adaption and open innovation in SMEs: An strategic assessment for women-owned SMEs sustainability in Bangladesh. Sustainability 2021, 13, 2942. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khanum, F.; Akter, N.; Deep, T.A.; Nayeem, M.A.R.; Akter, F. The role of women entrepreneurship in women empowerment: A case study in the city of Barishal, Bangladesh. Bangladesh. Asian J. Adv. Res. 2020, 5, 13–24. [Google Scholar]

- Hossain, S.; Islam, M.S.; Kundu, S.; Faruq, O.; Hossen, M.A. Women Participation in Entrepreneurial Activities in the Post COVID-19 Pandemic: Empirical Evidence from SMEs Sector. Health Econ. Manag. Rev. 2023, 1, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tvorik, S.J.; McGiven, M. Determinants of organizational performance. Manag. Decis. 1997, 35, 417–435. [Google Scholar]

- Sahoo, S.; Kumar, S.; Donthu, N.; Singh, A.K. Artificial intelligence capabilities, open innovation, and business performance–Empirical insights from multinational B2B companies. Ind. Mark. Manag. 2024, 117, 28–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hunt, S.D.; Morgan, R.M. The Resource-Advantage Theory of Competition: Dynamics, Path Dependencies, and Evolutionary Dimensions. J. Mark. 1996, 60, 107–114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Richard, P.J.; Devinney, T.M.; Yip, G.S.; Johnson, G. Measuring organizational performance: Towards methodological best practice. J. Manag. 2009, 35, 718–804. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaplan, R.S.; Norton, D.P. Transforming the balanced scorecard from performance measurement to strategic management: Part II. Account. Horiz. 2001, 15, 147–160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reichheld, F.F. Learning from Customer Defections. Harv. Bus. Rev. 1996, 74, 56–69. Available online: http://search.ebscohost.com/login.aspx?direct=true&db=bth&AN=9603067619&site=eds-live (accessed on 11 November 2024).

- Wiklund, J. The sustainability of the entrepreneurial orientation-performance relationship. Entrep. Growth Firms 1999, 24, 37–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haseeb, M.; Hussain, H.I.; Kot, S.; Androniceanu, A.; Jermsittiparsert, K. Role of social and technological challenges in achieving a sustainable competitive advantage and sustainable business performance. Sustainability 2019, 11, 3811. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hurtado-Palomino, A.; Gala-Velásquez, B.D.L.; Zirena-Bejarano, P.P.; Bustamante-Carpio, J.A. Structural Capital and Firm Performance: Synergistic Effects of Realized and Potential Absorptive Capacities in Tourism Businesses. Glob. Bus. Rev. 2024, 09721509241228012. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maina, W. Factors Influencing Performance of Women Owned Micro and Small Enterprises in Kikuyu Sub County, Kiambu County Kenya. Ph.D. Thesis, University of Nairobi, Nairobi, Kenya, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Bhardwaj, A.; Punia, B.K. Managerial competencies and their influence on managerial performance: A literature review introduction. Int. J. Adv. Res. Manag. Soc. Sci. 2013, 2, 70–84. Available online: http://garph.co.uk/IJARMSS/May2013/6.pdf (accessed on 9 November 2024).

- Gunawan, J.; Aungsuroch, Y. Managerial competence of first-line nurse managers: A concept analysis. Int. J. Nurs. Pract. 2017, 23, e12502. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yuan, C.C.; Lo, S.H. Relationship Among Team Temporal Leadership, Competency, Followership, and Performance in Taiwanese Pharmaceutical Industry Leaders and Employees. J. Career Dev. 2018, 45, 227–238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Damanpour, F. Organizational Size and Innovation. Organ. Stud. 1992, 13, 375–402. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Niode, I.Y. The effect of management capability and entrepreneurial orientation on business performance through business strategy as an intervening variable. J. Manaj. Dan Pemasar. Jasa 2022, 15, 255–274. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lewrick, M.; Omar, M.; Raeside, R.; Sailer, K. Education for entrepreneurship and innovation: Management capabilities for sustainable growth and success. World J. Entrep. Manag. Sustain. Dev. 2011, 6, 1–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Papulova, Z.; Mokros, M. Importance of Managerial Skills and Knowledge in Management for Small Entrepreneurs. E-Lead. Prague 2007, 1–8. [Google Scholar]

- Bilderback, S. Integrating training for organizational sustainability: The application of Sustainable Development Goals globally. Eur. J. Train. Dev. 2024, 48, 730–748. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Urefe, O.; Odonkor, T.N.; Chiekezie, N.R.; Agu, E.E. Enhancing small business success through financial literacy and education. Magna Sci. Adv. Res. Rev. 2024, 11, 297–315. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xuan, L.M.; Jamaluddin, A.; Zainalaludin, Z.; Yusoff, I.S.M. Advancing Women Entrepreneurs: A Framework for Small Family Businesses Success Within the Sustainable Economy. J. Account. Bus. Manag. (JABM) 2024, 32, 257–278. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Agbim, K.C.; Owutuamor, Z.B.; Oriarewo, G.O. Entrepreneurship development and tacit knowledge: Exploring the link between entrepreneurial learning and individual know-how. J. Bus. Stud. Q. 2013, 5, 112. [Google Scholar]

- Rehman, S.U.; Elrehail, H.; Nair, K.; Bhatti, A.; Taamneh, A.M. MCS package and entrepreneurial competency influence on business performance: The moderating role of business strategy. Eur. J. Manag. Bus. Econ. 2023, 32, 1–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmetaj, B.; Kruja, A.D.; Hysa, E. Women entrepreneurship: Challenges and perspectives of an emerging economy. Adm. Sci. 2023, 13, 111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Man, T.W.; Lau, T.; Chan, K. The competitiveness of small and medium enterprises. J. Bus. Ventur. 2002, 17, 123–142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baia, E.P.; Ferreira, J.J. Dynamic capabilities and performance: How has the relationship been assessed? J. Manag. Organ. 2024, 30, 188–217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Decenzo, D.; Anish, A. Management Practices of Successful Female Business Owners. Am. J. Small Bus. 1988, 8, 40–46. [Google Scholar]

- Bhattacharya, M.; Gibson, D.E.; Doty, D.H. The effects of flexibility in employee skills, employee behaviors, and human resource practices on firm performance. J. Manag. 2005, 31, 622–640. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramadan, A.; Alkhodary, D.; Alnawaiseh, M.; Jebreen, K.; Morshed, A.; Ahmad, A.B. Managerial Competence and Inventory Management in SME Financial Performance: A Hungarian Perspective. J. Stat. Appl. Probab. 2024, 13, 859–870. [Google Scholar]

- Machio, P.M.; Kimani, D.N.; Kariuki, P.C.; Ng’ang’a, A.M.; Njoroge, M.M. Social Capital and Women’s Empowerment. Forum Soc. Econ. 2024, 53, 322–340. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paarima, Y.; Ansah Ofei, A.M.; Kwashie, A.A. Managerial competencies of nurse managers in Ghana. Afr. J. Nurs. Midwifery 2020, 22, 20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ahmad, N.H.; Suseno, Y.; Seet, P.S.; Susomrith, P.; Rashid, Z. Entrepreneurial competencies and firm performance in emerging economies: A study of women entrepreneurs in malaysia. Contrib. Manag. Sci. 2018, 5–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, D.-Y.; Liu, J. Dynamic capabilities, environmental dynamism, and competitive advantage: Evidence from China. J. Bus. Res. 2014, 67, 2793–2799. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Afshari, M.; Honary, H.; Ghafouri, F. An experimental study of three managerial skills (conceptual, human, technical) of administrative directors pf physical edeucation organizations throughout the country. Sport Manag. 2010, 105–125. [Google Scholar]

- Yap, C.S.; Keling, W.; Ho, P.L. Determinants of entrepreneurial performance of rural indigenous women entrepreneurs in Sarawak, Malaysia. Gend. Manag. Int. J. 2023, 38, 337–356. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Asandimitra, N.; Kautsar, A.; Dewie, T.W.; Kusumawati, N.D.; Nihaya, I.U. Women in business: The impact of digital and financial literacy on female-owned small and medium-sized enterprises. Invest. Manag. Financ. Innov. 2024, 21, 330–343. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tuominen, M.; Torkkeli, M. The contribution of technology selection to core competencies. Int. J. Prod. Econ. 2002, 77, 271–284. [Google Scholar]

- Walsh, S.; Linton, J.D. The measurement of technical competencies. J. High Technol. Manag. Res. 2002, 13, 63–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heredia, J.; Castillo-Vergara, M.; Geldes, C.; Gamarra, F.M.C.; Flores, A.; Heredia, W. How do digital capabilities affect firm performance? The mediating role of technological capabilities in the “new normal”. J. Innov. Knowl. 2022, 7, 100171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tyler, B.B. The complementarity of cooperative and technological competencies: A resource-based perspective. J. Eng. Technol. Manag. (JET-M) 2001, 18, 1–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chatterjee, S.; Chaudhuri, R.; Vrontis, D.; Papadopoulos, T. Examining the impact of deep learning technology capability on manufacturing firms: Moderating roles of technology turbulence and top management support. Ann. Oper. Res. 2024, 339, 163–183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- El-Sabaa, S. The skills and career path of an effective project manager. Int. J. Proj. Manag. 2001, 19, 1–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Man, W.Y.T. Entrepreneurial Competencies and the Performance of Small and Medium Enterprises in the Hong Kong Services Sector. Ph.D. Thesis, Hong Kong Polyrechnic University, Hung Hom, Hong Kong, 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, Y.; Ma, X.; Pang, J.; Xing, H.; Wang, J. The impact of digital transformation of manufacturing on corporate performance—The mediating effect of business model innovation and the moderating effect of innovation capability. Res. Int. Bus. Financ. 2023, 64, 101890. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McEvily, S.K.; Eisenhardt, K.M.; Prescott, J.E. The global acquisition, leverage, and protection of technological competencies. Strateg. Manag. J. 2004, 25, 713–722. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Verona, G. A resource-based view of product development. Acad. Manag. Rev. 1999, 24, 132–142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Etemad, H.; Lee, Y. Technological capabilities and industrial concentration in NICs and industrialized countries: Taiwanese SMEs versus South Korean chaebols. Int. J. Entrep. Innov. Manag. 2001, 1, 329–355. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, C.; Lee, K.; Pennings, J.M. Internal capabilities, external networks, and performance: A study on technology-based ventures. Strateg. Manag. J. 2001, 22, 615–640. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shen, L.; Zhang, X.; Liu, H. Digital technology adoption, digital dynamic capability, and digital transformation performance of textile industry: Moderating role of digital innovation orientation. Manag. Decis. Econ. 2022, 43, 2038–2054. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duysters, G.; Hagedoorn, J. Core competences and company performance in the world-wide computer industry. J. High Technol. Manag. Res. 2000, 11, 75–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shea, T.; Usman, S.A.; Arivalagan, S.; Parayitam, S. “Knowledge management practices” as moderator in the relationship between organizational culture and performance in information technology companies in India. VINE J. Inf. Knowl. Manag. Syst. 2023, 53, 719–747. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kamar, K.; Lewaherilla, N.C.; Ausat, A.M.A.; Ukar, K.; Gadzali, S.S. The Influence of Information Technology and Human Resource Management Capabilities on SMEs Performance. Int. J. Artif. Intell. Res. 2022, 6, 1. [Google Scholar]

- Parmigiani, A.; Mitchell, W. The hollow corporation revisited: Can governance mechanisms substitute for technical expertise in managing buyer-supplier relationships. Eur. Manag. Rev. 2010, 7, 46–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Madhoun, M.I.; Analoui, F. Managerial skills and SMEs’ development in Palestine. Career Dev. Int. 2003, 8, 367–379. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eikebrokk, T.R.; Olsen, D.H.; Garmann-Johnsen, N.F. Conceptualizing Business Process Management Capabilities in Digitalization Contexts. Procedia Comput. Sci. 2024, 239, 330–337. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Teece, D.J.; Pisano, G.; Shuen, A. Dynamic capabilities and strategic management. Strateg. Manag. J. 1997, 18, 509–533. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Teece, D.J. Explicating dynamic capabilities: The nature and microfoundations of (sustainable) enterprise performance. Strateg. Manag. J. 2007, 28, 1319–1350. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Markedium. SMEs of Bangladesh: The Present Scenario and Future Prospects. 2022. Available online: https://markedium.com/smes-of-bangladesh-the-present-scenario-and-future-prospects/ (accessed on 12 November 2024).

- International Monetary Fund. World Economic Outlook Database, October 2019. 2020. Available online: https://www.imf.org/en/Publications/WEO/Issues/2020/04/14/weo-april-2020 (accessed on 9 November 2024).

- Ministry of Industries, Government of the People’s Republic of Bangladesh. Small and Medium Enterprises (SME) Policy 2019. 2019. Available online: https://moind.portal.gov.bd/sites/default/files/files/moind.portal.gov.bd/page/66b4934c_1ad2_4ab3_a9f8_329331d9b054/10.%20SME%20Policy%202019.pdf (accessed on 9 November 2024).

- Faisal-E-Alam, M.; Khan, M.R.A.; Rahman, M.A.; Ferreira, P.; Almeida, D.; Castanho, R.A. Critical Individual and Organizational Drivers of Circular Economy Implementation in SMEs in Bangladesh. Sustainability 2024, 16, 7149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mia, M.A.; Nasrin, S.; Zhang, M.; Rasiah, R. Chittagong, Bangladesh. Cities 2015, 48, 31–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nawanir, G. The effect of lean manufacturing on operations performance and business performance in manufacturing companies in Indonesia. Ph.D. Thesis, Universiti Utara Malaysia, Kedah, Malaysia, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Desarbo, W.S.; Di Benedetto, C.A.; Song, M.; Sinha, I. Revisiting the miles and snow strategic framework: Uncovering interrelationships between strategic types, capabilities, environmental uncertainty, and firm performance. Strateg. Manag. J. 2005, 26, 47–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Conant, J.S.; Mokwa, M.P.; Varadarajan, P.R. Strategic types, distinctive marketing competencies and organizational performance: A multiple measures-based study. Strateg. Manag. J. 1990, 11, 365–383. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pavett, C.M.; Lau, A.W. Managerial work: The influence of hierarchical level and functional specialty. Acad. Manag. J. 1983, 26, 170–177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chandler, G.N.; Jansen, E. The founder’s self-assessed competence and venture performance. J. Bus. Ventur. 1992, 7, 223–236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramli, N.A.; Latan, H.; Nartea, G.V. Why Should PLS-SEM be Used Rather than Regression? Evidence from the Capital Structure Perspective. In Partial Least Squares Structural Equation Modeling: Recent Advances in Banking and Finance; Avkiran, N., Ringle, C., Eds.; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2018; pp. 171–209. [Google Scholar]

- Sarstedt, M.; Ringle, C.M.; Hair, J.F. Partial Least Squares Structural Equation Modeling. In Handbook of Market Research; Homburg, C., Klarmann, M., Vomberg, A., Eds.; Springer International Publishing: Cham, Switzerland, 2021; pp. 587–632. [Google Scholar]

- Podsakoff, P.M.; MacKenzie, S.B.; Lee, J.-Y.; Podsakoff, N.P. Common method biases in behavioral research: A critical review of the literature and recommended remedies. J. Appl. Psychol. 2003, 88, 879–903. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Conway, J.M.; Lance, C.E. What reviewers should expect from authors regarding common method bias in organizational research. J. Bus. Psychol. 2010, 25, 325–334. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hair, J.F.; Hult, G.T.M.; Thiele, K.O.; Sarstedt, M.; Ringle, C.M. Mirror, Mirror on the Wall: A Comparative Evaluation of Six Structural Equation Modeling Methods. In Developments in Marketing Science: Proceedings of the Academy of Marketing Science; Kim, K., Ed.; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2016; pp. 991–992. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cooper, D.R.; Schindler, P.S.; Sharma, J.K. Business Research Methods, 12/E (SIE); McGraw-Hill Education: New York, NY, USA, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Franke, G.R.; Sarstedt, M. Heuristics Versus Statistics in Discriminant Validity Testing: A Comparison of Four Procedures. Internet Res. 2019, 29, 430–447. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fornell, C.; Larcker, D.F. Evaluating structural equation models with unobservable variables and measurement error. J. Mark. Res. 1981, 18, 39–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chin, W.W. The Partial Least Squares Approach to Structural Equation Modeling. In Modern Methods for Business Research; Marcoulides, G.A., Ed.; Lawrence Erlbaum Associates: Mahwah, NJ, USA, 1998; pp. 295–336. [Google Scholar]

- Cohen, J. Statistical Power Analysis for the Behavioral Sciences, 2nd ed.; Routledge: London, UK, 1988. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dyke, L.S.; Fischer, E.M.; Reuber, A.R. An inter-industry examination of the impact of owner experience on firm performance. J. Small Bus. Manag. 1992, 30, 72–87. [Google Scholar]

- Babajide, A.; Osabuohien, E.; Tunji-Olayeni, P.; Falola, H.; Amodu, L.; Olokoyo, F.; Adegboye, F.; Ehikioya, B. Financial literacy, financial capabilities, and sustainable business model practice among small business owners in Nigeria. J. Sustain. Financ. Invest. 2023, 13, 1670–1692. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Segal, G.; Borgia, D.; Schoenfeld, J. Founder human capital and small firm performance: An empirical study of founder-managed natural food stores. J. Manag. Mark. Res. 2010, 4, 1–10. Available online: http://www.aabri.com/manuscripts/09260.pdf (accessed on 11 November 2024).

- Marchiori, D.M.; Rodrigues, R.G.; Popadiuk, S.; Mainardes, E.W. The relationship between human capital, information technology capability, innovativeness and organizational performance: An integrated approach. Technol. Forecast. Soc. Change 2022, 177, 121526. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Tabbaa, O.; Zahoor, N. Alliance management capability and SMEs’ international expansion: The role of innovation pathways. J. Bus. Res. 2024, 171, 114384. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rashid, S.; Ratten, V. How Women Entrepreneurs Are Adapting in Dynamic Entrepreneurial Ecosystem of Pakistan. In Strategic Entrepreneurial Ecosystems and Business Model Innovation; Ratten, V., Ed.; Emerald Publishing Limited: Bingley, UK, 2022; pp. 41–59. [Google Scholar]

- Qader, A.A.; Zhang, J.; Ashraf, S.F.; Syed, N.; Omhand, K.; Nazir, M. Capabilities and opportunities: Linking knowledge management practices of textile-based SMEs on sustainable entrepreneurship and organizational performance in China. Sustainability 2022, 14, 2219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buzzao, G.; Rizzi, F. On the conceptualization and measurement of dynamic capabilities for sustainability: Building theory through a systematic literature review. Bus. Strategy Environ. 2021, 30, 135–175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chian, J.; Hanifah, H.; Vafaei-Zadeh, A. Development of entrepreneurial competencies and business performance in SMEs: Between government support and empowerment of Malaysian women entrepreneurs. Glob. J. Al-Thaqafah 2022, SI, 23–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Epezagne Assamala, I.R.; Li, W.; Ashraf, S.F.; Syed, N.; Di, H.; Nazir, M. Mediation-moderation model: An empirical examination of sustainable women entrepreneurial performance towards agricultural SMEs in ivory coast. Sustainability 2022, 14, 6368. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Dyk, E. Female Leaders: A Dynamic Capabilities View on Diversity and Equality. Master’s Thesis, University of Pretoria, Pretoria, South Africa, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Constantine, W.; Thedy, P.A.; Claudia, J.; Anggriawan, C.; Angdris, J.F.; Ardyan, E. How Do Young Entrepreneurs Enhance Problem-Solving Skills and Quality Business Decision Making? Understanding the Driver Factors. J. Entrep. Dan Entrep. 2024, 13, 135–148. [Google Scholar]

- Nigam, N.; Shatila, K. Entrepreneurial intention among women entrepreneurs and the mediating effect of dynamic capabilities: Empirical evidence from Lebanon. Int. J. Entrep. Behav. Res. 2024, 30, 916–937. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Categories | Subcategories | Frequency | Valid | Percentage | Cumulative Percentage |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Marial Status | Single | 85 | 216 | 39.4 | 39.4 |

| Married | 120 | 55.6 | 94.9 | ||

| Divorced | 6 | 2.8 | 97.7 | ||

| Widow | 5 | 2.3 | 100.0 | ||

| Age | >20 | 3 | 216 | 1.4 | 1.4 |

| 21–30 | 112 | 51.9 | 53.2 | ||

| 31–40 | 76 | 35.2 | 88.4 | ||

| 41–50 | 23 | 10.6 | 99.1 | ||

| 50+ | 2 | 0.9 | 100.0 | ||

| Number of Employees | >25 | 129 | 216 | 59.7 | 59.7 |

| 25–50 | 79 | 36.6 | 96.3 | ||

| 50–150 | 8 | 3.7 | 100.0 | ||

| Duration | 1–5 | 162 | 216 | 75.0 | 75.0 |

| 6–10 | 45 | 20.8 | 95.8 | ||

| 11–15 | 6 | 2.8 | 98.6 | ||

| 15+ | 3 | 1.4 | 100.0 | ||

| Type of Business | Coffee and Restaurant | 20 | 216 | 0.5 | 0.5 |

| Fast food | 14 | 9.3 | 9.8 | ||

| Confectionary | 9 | 6.5 | 16.3 | ||

| Small food factory | 12 | 4.1 | 20.4 | ||

| Catering | 24 | 5.6 | 26 | ||

| Bakery | 19 | 11.0 | 37.0 | ||

| Others | 117 | 63.0 | 100.0 |

| Constructs | Items | Loadings | CA | CR | AVE |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sustainable Business Performance | SBP1 | 0.755 | 0.765 | 0.784 | 0.509 |

| SBP2 | 0.687 | ||||

| SBP3 | 0.798 | ||||

| SBP4 | 0.697 | ||||

| SBP5 | 0.616 | ||||

| Conceptual Competency | CC1 | 0.854 | 0.882 | 0.889 | 0.680 |

| CC2 | 0.825 | ||||

| CC3 | 0.773 | ||||

| CC4 | 0.866 | ||||

| CC5 | 0.803 | ||||

| Management Capabilities | MgtC1 | 0.735 | 0.856 | 0.862 | 0.582 |

| MgtC2 | 0.777 | ||||

| MgtC3 | 0.738 | ||||

| MgtC4 | 0.806 | ||||

| MgtC5 | 0.806 | ||||

| MgtC6 | 0.712 | ||||

| Technological Capabilities | TC1 | 0.767 | 0.853 | 0.861 | 0.575 |

| TC2 | 0.787 | ||||

| TC3 | 0.758 | ||||

| TC4 | 0.739 | ||||

| TC5 | 0.756 | ||||

| TC6 | 0.741 |

| SBP | CC | MgtC | TC | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| SBP | ||||

| CC | 0.643 | |||

| MgtC | 0.583 | 0.808 | ||

| TC | 0.476 | 0.639 | 0.875 |

| SBP | CC | MgtC | TC | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| SBP | 0.713 | |||

| CC | 0.566 | 0.825 | ||

| MgtC | 0.494 | 0.707 | 0.763 | |

| TC | 0.413 | 0.569 | 0.750 | 0.758 |

| R-Square | R-Square Adjusted | Q-Sqaure | |

|---|---|---|---|

| SBP | 0.352 | 0.352 | 0.232 |

| CC | 0.506 | 0.504 | 0.497 |

| CC | MgtC | SBP | TC | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| CC | 0.074 | |||

| MgtC | 1.025 | 0.022 | ||

| SBP | ||||

| TC | 0.002 |

| Relationships | Beta | SD | t-Value | p-Value | Decision | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| H1 | MgtC → SBP | 0.382 | 0.090 | 4.253 | 0.000 | Supported |

| H2 | MgtC → CC | 0.713 | 0.039 | 18.280 | 0.000 | Supported |

| H3 | CC → SBP | 0.344 | 0.082 | 4.194 | 0.000 | Supported |

| H4 | TC × CC → SBP | −0.103 | 0.046 | 2.256 | 0.024 | Not Supported |

| Total Effects (MgtC → SBP) | Direct Effect (MgtC → SBP) | Indirect Effects of MgtC on SBP | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Beta | t Value | p Value | Beta | t Value | p Value | Hypothesis | Beta | SE | t Value | p Value |

| 0.382 | 4.253 | 0.000 | 0.137 | 1.494 | 0.135 | MgtC → CC → SBP | 0.245 | 0.061 | 3.997 | 0.000 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Akther, S.; Islam, M.R.; Faisal-E-Alam, M.; Castanho, R.A.; Loures, L.; Ferreira, P. Linking Management Capabilities to Sustainable Business Performance of Women-Owned Small and Medium Enterprises in Emerging Market: A Moderation and Mediation Analysis. Sustainability 2024, 16, 10193. https://doi.org/10.3390/su162310193

Akther S, Islam MR, Faisal-E-Alam M, Castanho RA, Loures L, Ferreira P. Linking Management Capabilities to Sustainable Business Performance of Women-Owned Small and Medium Enterprises in Emerging Market: A Moderation and Mediation Analysis. Sustainability. 2024; 16(23):10193. https://doi.org/10.3390/su162310193

Chicago/Turabian StyleAkther, Sharmin, Mohammed Rafiqul Islam, Md. Faisal-E-Alam, Rui Alexandre Castanho, Luís Loures, and Paulo Ferreira. 2024. "Linking Management Capabilities to Sustainable Business Performance of Women-Owned Small and Medium Enterprises in Emerging Market: A Moderation and Mediation Analysis" Sustainability 16, no. 23: 10193. https://doi.org/10.3390/su162310193

APA StyleAkther, S., Islam, M. R., Faisal-E-Alam, M., Castanho, R. A., Loures, L., & Ferreira, P. (2024). Linking Management Capabilities to Sustainable Business Performance of Women-Owned Small and Medium Enterprises in Emerging Market: A Moderation and Mediation Analysis. Sustainability, 16(23), 10193. https://doi.org/10.3390/su162310193