Exploring the Factors Influencing Tourists’ Satisfaction and Continuance Intention of Digital Nightscape Tour: Integrating the Design Dimensions and the UTAUT2

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Theoretical Background and Hypotheses

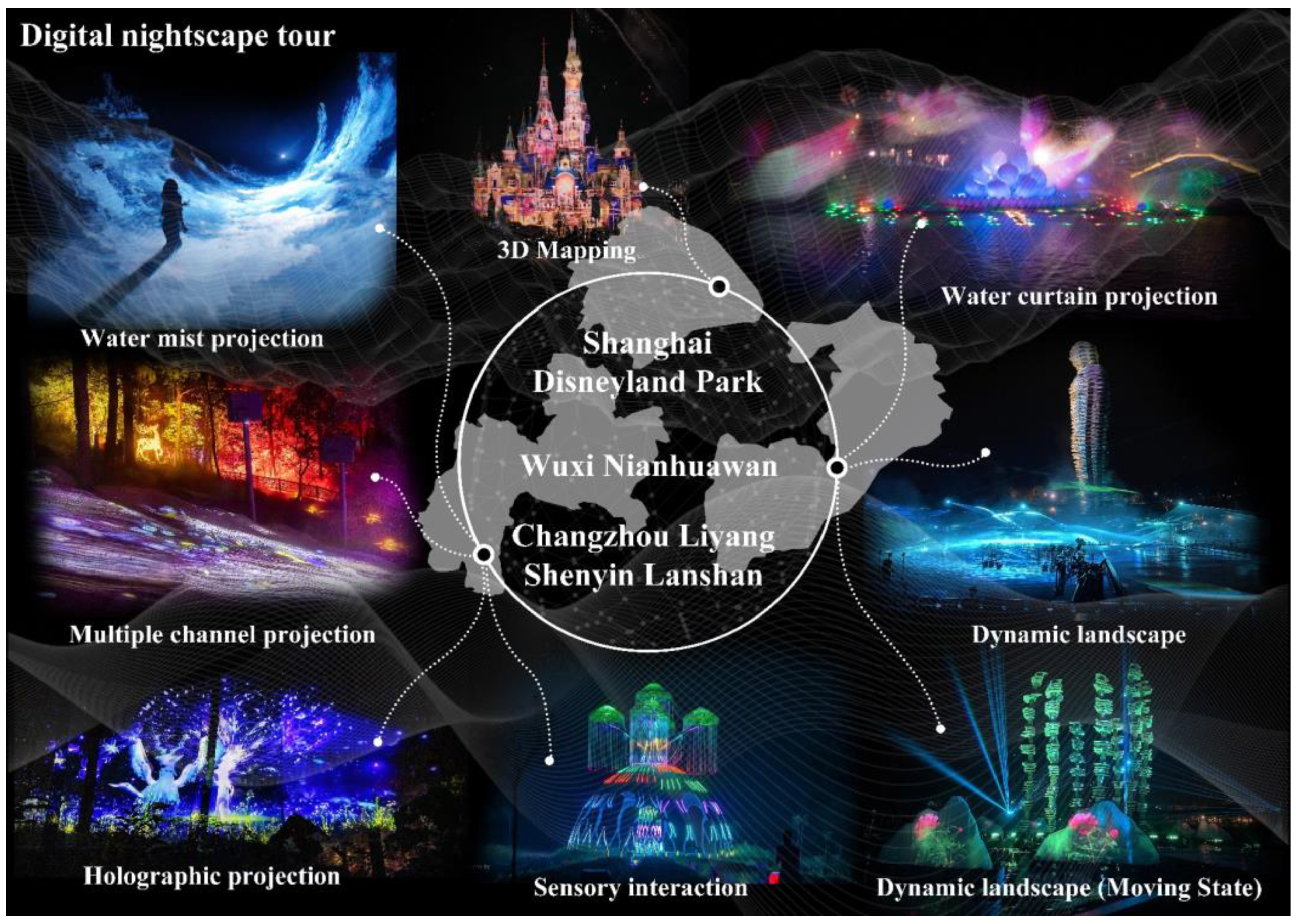

2.1. Digital Nightscape Tour

2.2. Factors Impacting Tourists’ Satisfaction and Continuance Intention

2.3. Theoretical Background

2.3.1. UTAUT2

2.3.2. Ambience and Spatial Layout

2.3.3. Innovation and Cultural Contact

2.4. Hypothesis Development

2.4.1. UTAUT2 in the Context of Digital Nightscape Tour

2.4.2. Impact of Ambience and Spatial Layout on Satisfaction

2.4.3. Impact of Innovation and Cultural Contact on Satisfaction

3. Method

3.1. Data Collection Process

3.2. Measures

3.3. Data Analysis

4. Results

4.1. The Measurement Model

4.2. Structural Equation Model

4.3. Analysis of Direct, Indirect, and Total Effects

5. Discussion and Conclusions

5.1. Discussion

5.2. Conclusions

6. Contributions and Shortcomings

6.1. Theoretical Contributions

6.2. Practical Implications

6.3. Limitations and Future Research Suggestions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Chang, J.; Hsieh, A.T. Leisure motives of eating out in night markets. J. Bus. Res. 2006, 59, 1276–1278. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Valetti, L.; Pellegrino, A.; Aghemo, C. Cultural Landscape: Towards the Design of a Nocturnal Lightscape. J. Cult. Herit. 2020, 42, 181–190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, L.; Li, X.; Guo, Y. Research on the Influencing Factors of Spatial Vitality of Night Parks Based on AHP–Entropy Weights. Sustainability 2024, 16, 5165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eldridge, A.; Smith, A. Tourism and the Night: Towards a Broader Understanding of Nocturnal City Destinations. J. Policy Res. Tour. Leis. Events 2019, 11, 371–379. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, R. Digital Economy Drives Tourism Development—Empirical Evidence Based on the UK. Econ. Res.-Ekon. Istraživanja 2023, 36, 2003–2020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, L.; Zhao, H.; Liu, J.; He, T.; Zhu, H.; Liu, Y. How Does the Digital Economy Affect Carbon Emissions from Tourism? Empirical Evidence from China. J. Clean. Prod. 2024, 469, 143175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shaw, R. Neoliberal Subjectivities and the Development of the Night-Time Economy in British Cities. Geogr. Compass 2010, 4, 893–903. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Plyushteva, A. Commuting and the Urban Night: Nocturnal Mobilities in Tourism and Hospitality Work. In Tourism and the Night; Routledge: London, UK, 2021; pp. 37–51. [Google Scholar]

- Pinke-Sziva, I.; Smith, M.; Olt, G.; Berezvai, Z. Overtourism and the Night-Time Economy: A Case Study of Budapest. Int. J. Tour. Cities 2019, 5, 1–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eldridge, A. Strangers in the Night: Nightlife Studies and New Urban Tourism. In Tourism and the Night; Routledge: London, UK, 2021; pp. 52–65. [Google Scholar]

- Orange, H. Flaming Smokestacks: Kojo Moe and Night-Time Factory Tourism in Japan. J. Contemp. Archaeol. 2017, 4, 59–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dumbrăveanu, D.; Tudoricu, A.; Crăciun, A. The Night of Museums—A Boost Factor for the Cultural Dimension of Tourism in Bucharest. Hum. Geogr. 2014, 8, 55–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hung, H.K.; Wu, C.C. Impact of Night Markets on Residents’ Quality of Life. Soc. Behav. Personal. 2020, 48, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, J.; Zhang, Y. Does Tourism Contribute to the Nighttime Economy? Evidence from China. Curr. Issues Tour. 2023, 26, 1295–1310. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, W.J.; Wang, P. “All That’s Best of Dark and Bright”: Day and Night Perceptions of Hong Kong Cityscape. Tour. Manag. 2018, 66, 274–286. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, C.H.S. The Relationships among Brand Equity, Culinary Attraction, and Foreign Tourist Satisfaction. J. Travel Tour. Mark. 2016, 33, 1143–1161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, C.H.; Fang, Y.P. Conceptualizing, Validating, and Managing Brand Equity for Tourist Satisfaction. J. Hosp. Tour. Res. 2018, 42, 960–978. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, Y.; Hong, F. Examining the Relationship between Customer-Perceived Value of Night-Time Tourism and Destination Attachment among Generation Z Tourists in China. Tour. Recreat. Res. 2023, 48, 220–233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, R.; Li, Y.-Q.; Liu, C.-H.; Ruan, W.-Q. How to Create a Memorable Night Tourism Experience: Atmosphere, Arousal, and Pleasure. Curr. Issues Tour. 2022, 25, 1817–1834. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ruan, W.Q.; Jiang, G.X.; Li, Y.Q.; Zhang, S.N. Night Tourscape: Structural Dimensions and Experiential Effects. J. Hosp. Tour. Manag. 2023, 55, 108–117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boo, S.; Busser, J.A. Tourists’ Hotel Event Experience and Satisfaction: An Integrative Approach. J. Travel Tour. Mark. 2018, 35, 895–908. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, Y.-C. Integrated Concepts of the UTAUT and TPB in Virtual Reality Behavioral Intention. J. Retailing Consum. Serv. 2023, 70, 103127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kiatkawsin, K.; Han, H. Young Travelers’ Intention to Behave Pro-Environmentally: Merging the Value-Belief-Norm Theory and the Expectancy Theory. Tour. Manag. 2017, 59, 76–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abrate, G.; Quinton, S.; Pera, R. The Relationship Between Price Paid and Hotel Review Ratings: Expectancy-Disconfirmation or Placebo Effect? Tour. Manag. 2021, 85, 104314. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Venkatesh, V.; Thong, J.Y.; Xu, X. Consumer Acceptance and Use of Information Technology: Extending the Unified Theory of Acceptance and Use of Technology. MIS Q. 2012, 36, 157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Evans, G. Hold Back the Night: Nuit Blanche and All-Night Events in Capital Cities. Curr. Issues Tour. 2012, 15, 35–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bianchini, F. Night Cultures, Night Economies. Plan. Pract. Res. 1995, 10, 121–126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smith, R.G. World City Topologies. Prog. Hum. Geogr. 2003, 27, 561–582. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hsieh, A.-T.; Chang, J. Shopping and Tourist Night Markets in Taiwan. Tour. Manag. 2006, 27, 138–145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, M.; Upadhya, A. Night Shopping as a Tourist Attraction: A Study of Night Shopping in Dubai. J. Tour. Serv. 2017, 8, 7–18. [Google Scholar]

- Charman, A.; Govender, T. The Creative Night-Time Leisure Economy of Informal Drinking Venues. Int. J. Urban Reg. Res. 2020, 44, 793–808. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, N.; Wang, Y.; Li, J.; Wei, Y.; Yuan, Q. Examining Structural Relationships among Night Tourism Experience, Lovemarks, Brand Satisfaction, and Brand Loyalty on “Cultural Heritage Night” in South Korea. Sustainability 2020, 12, 6723. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Hu, W.; Park, K.S.; Yuan, Q.; Chen, N. Examining Residents’ Support for Night Tourism: An Application of the Social Exchange Theory and Emotional Solidarity. J. Destin. Mark. Manag. 2023, 28, 100780. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Colomb, C. Staging the New Berlin: Place Marketing and the Politics of Urban Reinvention Post-1989; Routledge: London, UK, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Pizam, A.; Neumann, Y.; Reichel, A. Dimensions of Tourist Satisfaction with a Destination Area. Ann. Tour. Res. 1978, 5, 314–322. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.; Jang, S. The Effects of Dining Atmospherics: An Extended Mehrabian-Russell Model. Int. J. Hosp. Manag. 2009, 28, 494–503. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kozak, M.; Rimmington, M. Tourist Satisfaction with Mallorca, Spain, as an Off-Season Holiday Destination. J. Travel Res. 2000, 38, 260–269. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saxena, A.; Sharma, N.K.; Pandey, D.; Pandey, B.K. Influence of Tourists Satisfaction on Future Behavioral Intentions with Special Reference to Desert Triangle of Rajasthan. Augment. Hum. Res. 2021, 6, 13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Canny, I.U. An Empirical Investigation of Service Quality, Tourist Satisfaction and Future Behavioral Intentions Among Domestic Local Tourists at Borobudur Temple. Int. J. Trade Econ. Financ. 2013, 4, 86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duong, C.D.; Nguyen, T.H.; Ngo, T.V.N.; Pham, T.T.P.; Vu, A.T.; Dang, N.S. Using Generative Artificial Intelligence (ChatGPT) for Travel Purposes: Parasocial Interaction and Tourists’ Continuance Intention. Tour. Rev. 2024, ahead-of-print. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Hwang, J. Dawn or Dusk? Will Virtual Tourism Begin to Boom? An Integrated Model of AIDA, TAM, and UTAUT. J. Hosp. Tour. Res. 2023, 48, 10963480231186656. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, M.J.; Hall, C.M. What Drives Visitor Economy Crowdfunding? The Effect of Digital Storytelling on Unified Theory of Acceptance and Use of Technology. Tour. Manag. Perspect. 2020, 34, 100638. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gupta, A.; Dogra, N.; George, B. What Determines Tourist Adoption of Smartphone Apps?: An Analysis Based on the UTAUT-2 Framework. J. Hosp. Tour. Technol. 2018, 9, 50–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amalia, F. The Used of Modified UTAUT 2 Model to Analyze the Continuance Intention of Travel Mobile Application. In Proceedings of the 2019 7th International Conference on Information and Communication Technology (ICoICT), Kuala Lumpur, Malaysia, 24–26 July 2019; IEEE: Piscataway, NJ, USA, 2019; pp. 1–6. [Google Scholar]

- Coves-Martínez, Á.L.; Sabiote-Ortiz, C.M.; Frías-Jamilena, D.M. How to Improve Travel-App Use Continuance: The Mod-erating Role of Culture. Tour. Manag. Perspect. 2023, 45, 101070. [Google Scholar]

- Bitner, M.J. Servicescapes: The Impact of Physical Surroundings on Customers and Employees. J. Mark. 1992, 56, 57–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Turley, L.W.; Milliman, R.E. Atmospheric Effects on Shopping Behavior: A Review of the Experimental Evidence. J. Bus. Res. 2000, 49, 193–211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bertan, S. Impact of Restaurants in the Development of Gastronomic Tourism. Int. J. Gastron. Food Sci. 2020, 21, 100232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schumpeter, J.A.; Swedberg, R. The Theory of Economic Development; Routledge: London, UK, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Divisekera, S.; Nguyen, V.K. Determinants of Innovation in Tourism: Evidence from Australia. Tour. Manag. 2018, 67, 157–167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scott, N.; Cooper, C.; Baggio, R. Destination Networks. Ann. Tour. Res. 2008, 35, 169–188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, S.-N.; Li, Y.-Q.; Liu, C.-H.; Ruan, W.-Q. How Does Authenticity Enhance Flow Experience through Perceived Value and Involvement: The Moderating Roles of Innovation and Cultural Identity. J. Travel Tour. Mark. 2019, 36, 710–728. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Custódio Santos, M.; Ferreira, A.; Costa, C.; Santos, J.A.C. A Model for the Development of Innovative Tourism Products: From Service to Transformation. Sustainability 2020, 12, 4362. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Işık, C.; Küçükaltan, E.G.; Taş, S.; Akoğul, E.; Uyrun, A.; Hajiyeva, T.; Bayraktaroğlu, E. Tourism and Innovation: A Literature Review. J. Ekonomi 2019, 1, 98–154. [Google Scholar]

- Gnoth, J.; Zins, A.H. Developing a Tourism Cultural Contact Scale. J. Bus. Res. 2013, 66, 738–744. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McKercher, B.; Du Cros, H. Testing a Cultural Tourism Typology. Int. J. Tour. Res. 2003, 5, 45–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, H.; Rahman, I. Cultural Tourism: An Analysis of Engagement, Cultural Contact, Memorable Tourism Experience and Destination Loyalty. Tour. Manag. Perspect. 2018, 26, 153–163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reisinger, Y. Tourist-Host Contact as a Part of Cultural Tourism. World Leis. Recreat. 1994, 36, 24–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, M.Y.; Li, Y.Q.; Ruan, W.Q.; Zhang, S.N.; Li, R. Influencing Factors and Formation Process of Cultural Inheritance-Based Innovation at Heritage Tourism Destinations. Tour. Manag. 2024, 100, 104799. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, H.; Youn, N. Immersed in Art: The Impact of Affinity for Technology Interaction and Hedonic Motivation on Aesthetic Experiences in Virtual Reality. Empir. Stud. Arts 2024, 02762374241282938. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ponsignon, F.; Derbaix, M. The Impact of Interactive Technologies on the Social Experience: An Empirical Study in a Cultural Tourism Context. Tour. Manag. Perspect. 2020, 35, 100723. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, V.; Akhter Shareef, M.; Kumar, U.; Persaud, A. Promotional Marketing Through Mobile Phone SMS: A Cross-Cultural Examination of Consumer Acceptance. Transnatl. Corp. Rev. 2016, 8, 1–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Macedo, I.M. Predicting the Acceptance and Use of Information and Communication Technology by Older Adults: An Em-pirical Examination of the Revised UTAUT2. Comput. Hum. Behav. 2017, 75, 935–948. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Assaker, G.; Hallak, R.; El-Haddad, R. Consumer Usage of Online Travel Reviews: Expanding the Unified Theory of Acceptance and Use of Technology 2 Model. J. Vacat. Mark. 2020, 26, 149–165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, X.; Lai, I.K.W. The Acceptance of Augmented Reality Tour App for Promoting Film-Induced Tourism: The Effect of Celebrity Involvement and Personal Innovativeness. J. Hosp. Tour. Technol. 2021, 12, 454–470. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Rojas, C.; Camarero, C. Visitors’ Experience, Mood, and Satisfaction in a Heritage Context: Evidence from an Interpretation Center. Tour. Manag. 2008, 29, 525–537. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Del Bosque, I.R.; Martín, H.S. Tourist Satisfaction: A Cognitive-Affective Model. Ann. Tour. Res. 2008, 35, 551–573. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Russell, J.A.; Snodgrass, J. Emotion and the Environment. In Handbook of Environmental Psychology; Stokols, D., Altman, I., Eds.; John Wiley & Sons: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 1987; Volume 1. [Google Scholar]

- Mehrabian, A.; Russell, J.A. An Approach to Environmental Psychology; MIT Press: Cambridge, UK, 1974. [Google Scholar]

- Bruner, G.C. Music, Mood, and Marketing. J. Mark. 1990, 54, 94–104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, L.; He, Z.; King, C.; Mattila, A.S. In Darkness We Seek Light: The Impact of Focal and General Lighting Designs on Customers’ Approach Intentions Toward Restaurants. Int. J. Hosp. Manag. 2021, 92, 102735. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhuang, M.; Zhang, H.; Li, P.; Shen, C.; Gao, X.; Zhang, J. Connecting Tourists to Musical Destinations: The Role of Musical Geographical Imagination and Aesthetic Responses in Music Tourism. Tour. Manag. 2023, 98, 104768. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spangenberg, E.R.; Crowley, A.E.; Henderson, P.W. Improving the Store Environment: Do Olfactory Cues Affect Evaluations and Behaviors? J. Mark. 1996, 60, 67–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Charousaei, M.; Faizi, M.; Khakzand, M. The Impact of the Visual Layout of University Open Space on Students’ Behavior and Satisfaction Level: The Case of Iran University of Science and Technology. Smart Sustain. Built Environ. 2024, ahead-of-print. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aldebert, B.; Dang, R.J.; Longhi, C. Innovation in the Tourism Industry: The Case of Tourism@. Tour. Manag. 2011, 32, 1204–1213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Csikszentmihalyi, M. Flow and the Psychology of Discovery and Invention; HarperPerennial: New York, NY, USA, 1997; pp. 1–16. [Google Scholar]

- De Massis, A.; Frattini, F.; Pizzurno, E.; Cassia, L. Product Innovation in Family Versus Nonfamily Firms: An Exploratory Analysis. J. Small Bus. Manag. 2015, 53, 1–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chandralal, L.; Valenzuela, F.R. Exploring Memorable Tourism Experiences: Antecedents and Behavioral Outcomes. J. Econ. Bus. Manag. 2013, 1, 177–181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schumacker, R.E.; Lomax, R.G. A Beginner’s Guide to Structural Equation Modeling; Psychology Press: London, UK, 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Fornell, C. Structural Equation Models with Unobservable Variables and Measurement Error: Algebra and Statistics; Publications Sage: Los Angeles, CA, USA, 1981. [Google Scholar]

- Chin, W.W. Commentary: Issues and Opinion on Structural Equation Modeling. MIS Q. 1998, 22, vii–xvi. [Google Scholar]

- Hu, L.; Bentler, P.M. Cutoff Criteria for Fit Indexes in Covariance Structure Analysis: Conventional Criteria Versus New Alternatives. Struct. Equ. Model. Multidiscip. J. 1999, 6, 1–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shin, D.H.; Shin, Y.J.; Choo, H.; Beom, K. Smartphones as Smart Pedagogical Tools: Implications for Smartphones as U-Learning Devices. Comput. Hum. Behav. 2011, 27, 2207–2214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shi, M.; Wang, Q.; Long, Y. Exploring the Key Drivers of User Continuance Intention to Use Digital Museums: Evidence from China’s Sanxingdui Museum. IEEE Access 2023, 11, 81511–81526. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alkhwaldi, A.F.A.; Kamala, M.A. Why Do Users Accept Innovative Technologies? A Critical Review of Models and Theories of Technology Acceptance in the Information System Literature. J. Inform. Syst. 2017, 4, 7962–7971. [Google Scholar]

- Choi, H.; Kandampully, J. The Effect of Atmosphere on Customer Engagement in Upscale Hotels: An Application of SOR Paradigm. Int. J. Hosp. Manag. 2019, 77, 40–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wan, C.K.B. Flourishing Through Smart Tourism: Experience Patterns for Co-Designing Technology-Mediated Traveller Experiences. Des. J. 2018, 21, 163–172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Benur, A.M.; Bramwell, B. Tourism Product Development and Product Diversification in Destinations. Tour. Manag. 2015, 50, 213–224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mathias, M.; Zhou, F.; Torres-Moreno, J.M.; Josselin, D.; Poli, M.S.; Carneiro Linhares, A. Personalized Sightseeing Tours: A Model for Visits in Art Museums. Int. J. Geogr. Inf. Sci. 2017, 31, 591–616. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hjalager, A.-M. 100 Innovations That Transformed Tourism. J. Travel Res. 2015, 54, 3–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yi, X.; Fu, X.; Yu, L.; Jiang, L. Authenticity and Loyalty at Heritage Sites: The Moderation Effect of Postmodern Authenticity. Tour. Manag. 2018, 67, 411–424. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fan, X.; Jiang, X.; Deng, N. Immersive Technology: A Meta-Analysis of Augmented/Virtual Reality Applications and Their Impact on Tourism Experience. Tour. Manag. 2022, 91, 104534. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Edensor, T. Illuminated Atmospheres: Anticipating and Reproducing the Flow of Affective Experience in Blackpool. Environ. Plan. D Soc. Space 2012, 30, 1103–1122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aylan, F.K.; Gök, H.S. Panoramic Museum Visits as Cultural Recreation Activities: Panorama 1453 History Museum Example. J. Tour. Leis. Hosp. 2021, 3, 103–117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qin, Q.; Xuan, W. Multisource Data–Based Urban Odor Map and Construction of a Scent-Emotional System for Public Spaces. J. Urban Plan. Dev. 2023, 149, 05023040. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Characteristic | Option | Frequency | Percent |

|---|---|---|---|

| Participating night tours | Shanghai Disneyland Nightscape | 143 | 28.8% |

| Changzhou Shenyin Nanshan Nightscape | 94 | 18.9% | |

| Universal Studios Nightscape | 73 | 14.7% | |

| Wuxi Nianhuawan Nightscape | 61 | 12.3% | |

| Shandong Taierzhuang Ancient Town Nightscape | 60 | 12.1% | |

| Other Nightscape | 66 | 13.3% | |

| Gender | Male | 199 | 40% |

| Female | 298 | 60% | |

| Age | 18~30 years old | 308 | 62% |

| 31~50 years old | 119 | 23.9% | |

| 51~60 years old | 49 | 9.8% | |

| Over 60 years old | 21 | 4.2% | |

| Income level (¥) | CNY Below 2000 | 64 | 12.9% |

| CNY 2000–5000 | 173 | 34.8% | |

| CNY 5000–10,000 | 168 | 33.8% | |

| CNY 10,000–20,000 | 62 | 12.4% | |

| CNY Over 20,000 | 30 | 6% | |

| Education | Junior high school and below | 9 | 2% |

| High school/Vocational school | 61 | 12.3% | |

| College | 96 | 19.2% | |

| University | 252 | 50.7% | |

| MBA or above | 79 | 15.8% |

| Latent Variable | Measurement Variable | Factor Loadings | Mean | Std. Dev | α | AVE | CR |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Social influence | SI1. People who are important to me think that I should experience the digital nightscape tour. | 0.912 | 5.08 | 1.32 | 0.901 | 0.753 | 0.901 |

| SI2. People who influence my behavior think I should experience the digital nightscape tour. | 0.859 | ||||||

| SI3. People whose opinions I value prefer that I experience the digital nightscape tour. | 0.830 | ||||||

| Hedonic motivation | HM1. I think experiencing the digital nightscape tour is fun. | 0.927 | 5.42 | 1.26 | 0.882 | 0.722 | 0.886 |

| HM2. I think experiencing the digital nightscape tour is enjoyable. | 0.834 | ||||||

| HM3. I think experiencing the digital nightscape tour is very entertaining. | 0.781 | ||||||

| Price value | PV1. The digital nightscape tour is reasonably priced. | 0.850 | 5.06 | 1.29 | 0.885 | 0.720 | 0.885 |

| PV2. The digital nightscape tour is good value for the money. | 0.807 | ||||||

| PV3. At the current price, the digital nightscape tour provides a good value. | 0.888 | ||||||

| Habit | HT1. The use of the digital nightscape tour has become a habit for me. | 0.933 | 4.77 | 1.38 | 0.881 | 0.722 | 0.886 |

| HT2. I am addicted to experiencing the digital nightscape tour. | 0.831 | ||||||

| HT3. Experiencing the digital nightscape tour has become natural to me. | 0.778 | ||||||

| Satisfaction | SA1. Overall, I am satisfied with the digital nightscape tour. | 0.838 | 5.42 | 1.19 | 0.885 | 0.724 | 0.887 |

| SA2. I am happy with my experience with the digital nightscape tour. | 0.883 | ||||||

| SA3. On the whole, I am satisfied with my experience in the digital nightscape tour. | 0.830 | ||||||

| Continuance intention | CI1. I have the intention to continue experiencing the digital nightscape tour in the future. | 0.892 | 5.19 | 1.29 | 0.889 | 0.731 | 0.890 |

| CI2. I will continue to experience the digital nightscape tour as much as possible. | 0.806 | ||||||

| CI3. In the future, I will continue to experience the digital nightscape tour. | 0.865 | ||||||

| Ambience | AMB1. I think the lighting arrangement in the digital nightscape tour is just right. | 0.892 | 5.16 | 1.27 | 0.890 | 0.674 | 0.891 |

| AMB2. I think the music arrangement in the digital nightscape tour is comfortable. | 0.809 | ||||||

| AMB3. I think the smell in the digital nightscape tour is pleasant. | 0.739 | ||||||

| AMB4. I think the digital art in the digital nightscape tour can evoke emotions. | 0.837 | ||||||

| Spatial layout | SL1. The digital nightscape tour provided a comfortable sightseeing space. | 0.843 | 5.09 | 1.20 | 0.843 | 0.643 | 0.844 |

| SL2. The overall layout of the digital nightscape tour is convenient to visit. | 0.813 | ||||||

| SL3. The overall layout of the digital nightscape tour prioritizes the privacy of tourists. | 0.747 | ||||||

| Innovation | INN1. The form of the digital nightscape tour experience is novel. | 0.905 | 5.31 | 1.30 | 0.903 | 0.703 | 0.904 |

| INN2. This experience challenged my existing ideas about the digital nightscape tour. | 0.816 | ||||||

| INN3. This experience provided new ideas for a digital nightscape tour. | 0.826 | ||||||

| INN4. The digital nightscape tour experience here is creative. | 0.804 | ||||||

| Cultural contact | CC1. I like the local customs, rituals, and lifestyles reflected in the digital nightscape tour. | 0.883 | 5.32 | 1.23 | 0.863 | 0.688 | 0.868 |

| CC2. I like to experience different recreational activities related to local culture during the digital nightscape tour. | 0.856 | ||||||

| CC3. I want to learn about cultural differences through the digital nightscape tour. | 0.742 |

| Constructs | SI | HM | PV | HT | SA | CI | AMB | SL | INN | CC |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| SI | 0.868 | |||||||||

| HM | 0.418 ** | 0.850 | ||||||||

| PV | 0.387 ** | 0.393 ** | 0.849 | |||||||

| HT | 0.273 ** | 0.189 ** | 0.389 ** | 0.850 | ||||||

| SA | 0.526 ** | 0.576 ** | 0.481 ** | 0.229 ** | 0.851 | |||||

| CI | 0.463 ** | 0.439 ** | 0.440 ** | 0.331 ** | 0.520 ** | 0.855 | ||||

| AMB | 0.426 ** | 0.367 ** | 0.349 ** | 0.245 ** | 0.493 ** | 0.436 ** | 0.821 | |||

| SL | 0.292 ** | 0.369 ** | 0.368 ** | 0.260 ** | 0.445 ** | 0.340 ** | 0.391 ** | 0.802 | ||

| INN | 0.334 ** | 0.458 ** | 0.399 ** | 0.191 ** | 0.542 ** | 0.378 ** | 0.429 ** | 0.449 ** | 0.838 | |

| CC | 0.332 ** | 0.410 ** | 0.268 ** | 0.170 ** | 0.501 ** | 0.361 ** | 0.400 ** | 0.379 ** | 0.473 ** | 0.829 |

| Model | χ2/df | GFI | AGFI | IFI | TLI | CFI | RMSEA |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Measurement model | 1.755 | 0.913 | 0.891 | 0.971 | 0.965 | 0.971 | 0.039 |

| Research model | 2.942 | 0.855 | 0.828 | 0.921 | 0.911 | 0.920 | 0.063 |

| Recommended criteria | <3.0 | >0.8 | >0.8 | >0.8 | >0.8 | >0.8 | <0.08 |

| Hypotheses | Hypothesized Path | B | β | S.E | t | Result |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| H1 | SI→CI | 0.148 | 0.175 | 0.044 | 3.348 *** | Supported |

| H2 | HM→CI | 0.129 | 0.153 | 0.041 | 3.110 ** | Supported |

| H3 | PV→CI | 0.143 | 0.162 | 0.042 | 3.371 *** | Supported |

| H4 | HT→CI | 0.098 | 0.130 | 0.033 | 2.949 ** | Supported |

| H5 | SA→CI | 0.272 | 0.275 | 0.057 | 4.784 *** | Supported |

| H6 | AMB→CI | 0.146 | 0.174 | 0.048 | 3.060 ** | Supported |

| H7 | AMB→SA | 0.221 | 0.261 | 0.040 | 5.545 *** | Supported |

| H8 | SL→SA | 0.156 | 0.167 | 0.046 | 3.393 *** | Supported |

| H9 | INN→SA | 0.225 | 0.268 | 0.040 | 5.545 *** | Supported |

| H10 | CC→SA | 0.213 | 0.240 | 0.044 | 4.878 *** | Supported |

| Dependent Variable | Independent Variable | Direct Effect | Indirect Effect | Total Effect | R2 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| CI | AMB | 0.174 | 0.072 | 0.246 | 0.296 |

| SL | _ | 0.046 | 0.046 | ||

| INN | _ | 0.074 | 0.037 | ||

| CC | _ | 0.066 | 0.066 | ||

| SA | 0.275 | _ | 0.275 | ||

| HT | 0.130 | _ | 0.130 | ||

| PV | 0.162 | _ | 0.162 | ||

| HM | 0.153 | _ | 0.153 | ||

| SI | 0.175 | _ | 0.175 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Rui, L.; Li, K.; Jiang, M.; Jiang, X. Exploring the Factors Influencing Tourists’ Satisfaction and Continuance Intention of Digital Nightscape Tour: Integrating the Design Dimensions and the UTAUT2. Sustainability 2024, 16, 9932. https://doi.org/10.3390/su16229932

Rui L, Li K, Jiang M, Jiang X. Exploring the Factors Influencing Tourists’ Satisfaction and Continuance Intention of Digital Nightscape Tour: Integrating the Design Dimensions and the UTAUT2. Sustainability. 2024; 16(22):9932. https://doi.org/10.3390/su16229932

Chicago/Turabian StyleRui, Liang, Keyi Li, Mu Jiang, and Xiaopu Jiang. 2024. "Exploring the Factors Influencing Tourists’ Satisfaction and Continuance Intention of Digital Nightscape Tour: Integrating the Design Dimensions and the UTAUT2" Sustainability 16, no. 22: 9932. https://doi.org/10.3390/su16229932

APA StyleRui, L., Li, K., Jiang, M., & Jiang, X. (2024). Exploring the Factors Influencing Tourists’ Satisfaction and Continuance Intention of Digital Nightscape Tour: Integrating the Design Dimensions and the UTAUT2. Sustainability, 16(22), 9932. https://doi.org/10.3390/su16229932