Determinants of Microfinance Demand (Evidence from Chiredzi Smallholder Resettled Sugarcane Farmers in Zimbabwe)

Abstract

1. Introduction and Background

2. Literature Review

2.1. Theoretical Literature Review

2.1.1. Institutionalist Approach

2.1.2. Welfarist Approach

2.2. Empirical Literature Review

3. Research Methodology

3.1. Data, Survey, and Sampling

3.2. Analytical Framework

3.2.1. Determinants of Microcredit Demand (Probit Model Specification)

3.2.2. Determinants of the Microcredit Size (Tobit Model Specification)

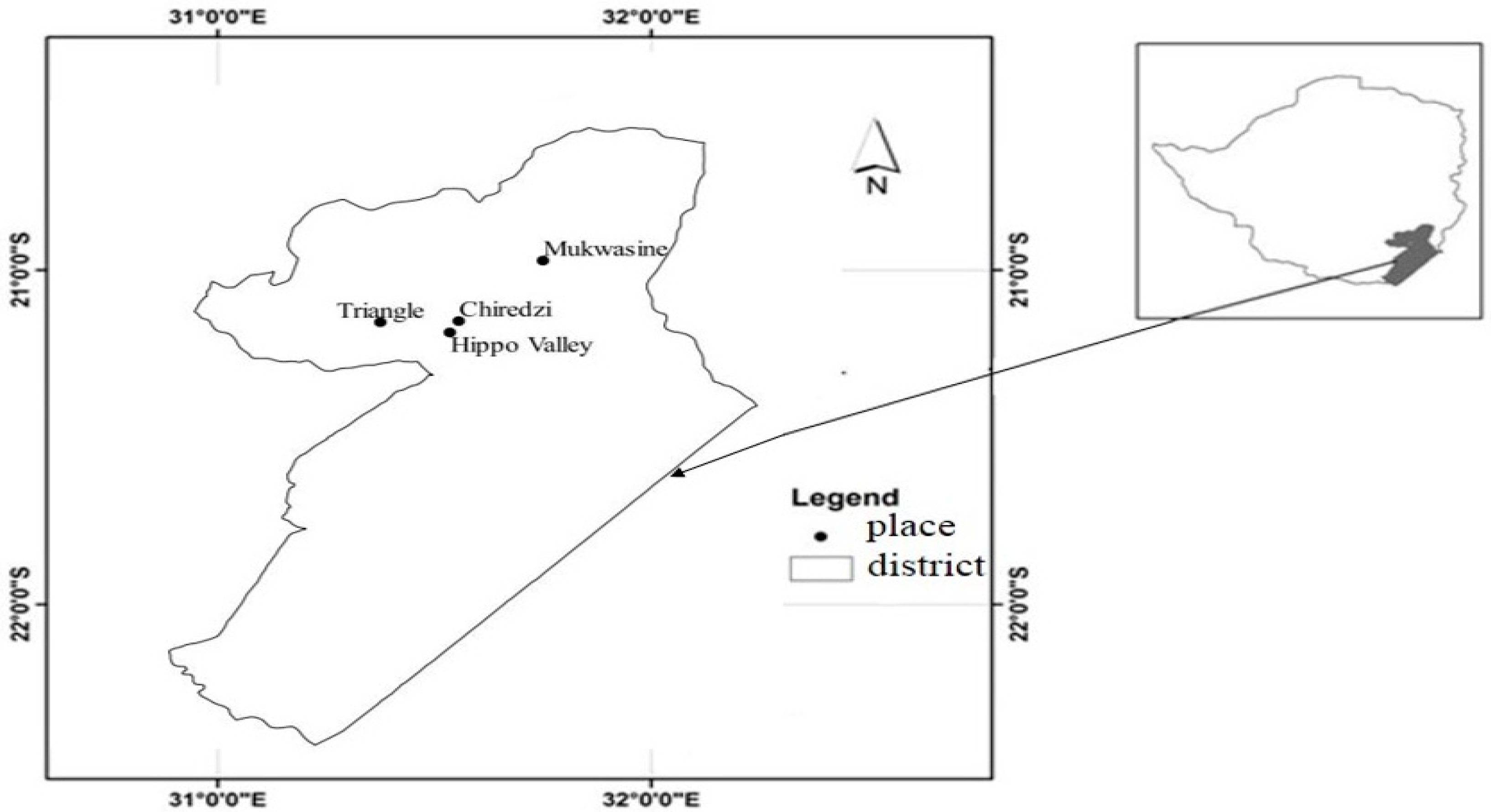

3.3. Description of the Study Area

3.3.1. Expected Signs

3.3.2. Multi-Collinearity Diagnosis

4. Results Presentation, Interpretation, and Analysis

4.1. Descriptive Statistics

4.2. Multi-Collinearity Diagnosis

4.3. Probit and Tobit Regression Results

4.4. Results Interpretation and Discussion

4.4.1. Demographic Determinants

4.4.2. Financial/Institutional Determinants

4.4.3. General Farming Determinants

5. Conclusions and Recommendations

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Samuel, A.; Eric, N.; Gabriel, K.-B. Does Loan Size Matter in How Collateral Characteristics Relate to Credit Access? J. Econ. Financ. Account. Stud. 2023, 6, 1–4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kangogo, D.; Lagat, J.; Ithinji, G. The Influence of Social Capital Dimensions on Household Participation in Micro-Credit Groups and Loan Repayment Performance in Uasin Gishu, Kenya, MPRA Working Paper No. 48624. 2013. Available online: https://mpra.ub.uni-muenchen.de/48624/ (accessed on 23 August 2024).

- Khan, S.; Anuar, A.R. Access to finance: Exploring barriers to entrepreneurship development in SMEs. In Global Entrepreneurship and New Venture Creation in the Sharing Economy; IGI Global: Hershey, PA, USA, 2018; pp. 92–111. [Google Scholar]

- Armendariz, B.A.; Morduch, J. The Economics of Microfinance, 2nd ed.; MIT Press: London, UK, 2010; ISBN 9780262513982. [Google Scholar]

- Domanban, P.B. Determinants of loan sizes in microfinance institutions: Evidence from the Upper West Region of Ghana. Cogent Econ. Financ. 2024, 12, 2300924. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dorfleitner, G.; Forcella, D.; Nguyen, Q.A. The digital transformation of microfinance institutions: An empirical analysis. J. Appl. Account. Res. 2022, 23, 454–479. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reserve Bank of Zimbabwe. Microfinance Annual Report. 2022. Available online: https://www.rbz.co.zw/index.php/financial-markets/nps/27-bs-annual-report/1290-2022-microfinance-annual-report (accessed on 20 November 2023).

- World Bank. World Development Report 2022: Finance for an Equitable Recovery; World Bank: Washington, DC, USA, 2022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chandio, A.A.; Jiang, Y.; Rehman, A.; Twumasi, M.A.; Pathan, A.G.; Mohsin, M. Determinants of demand for credit by smallholder farmers’: A farm level analysis based on survey in Sindh, Pakistan. J. Asian Bus. Econ. Stud. 2020, 28, 225–240. Available online: http://creativecommons.org/licences/by/4.0/legalcode (accessed on 25 May 2024). [CrossRef]

- Hailu, B.K.; Abrha, B.K.; Weldegiorgis, K.A. Adoption and impact of agricultural technologies on farm income: Evidence from Southern Tigray, Northern Ethiopia. Int. J. Food Agric. Econ. 2014, 2, 91–106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- International Finance Corporation. Access to Finance for Smallholder Farmers©; International Finance Corporation: Washington, DC, USA, 2014; Available online: http://hdl.handle.net/10986/21679 (accessed on 13 April 2024).

- World Bank Group. Microfinance and Economic Development Policy Research Working Paper 8252; Cull, R., Morduch, J., Eds.; Finance and Private Sector Development Team, Development Research Group; New York University: New York, NY, USA, 2017; Available online: https://papers.ssrn.com/sol3/papers.cfm?abstract_id=3076231 (accessed on 16 May 2024).

- Masiyandima, N.; Chigumira, G.; Bara, A. Sustainable Financing Options for Agriculture in Zimbabwe. Zimbabwe Economic Policy Analysis Research Unit (ZEPARU) Working Paper Series (ZWPS 02/10). 2011. Available online: https://EconPapers.repec.org/RePEc:ags:zepars:305816 (accessed on 23 August 2024). [CrossRef]

- Guy, M.E. The Macro Drawbacks of Microfinance; Student Publications 872. 2019. Available online: https://cupola.gettysburg.edu/student_scholarship/872 (accessed on 13 April 2024).

- Mpuga, P. Constraints in Access to and Demand for Rural Credit: Evidence from Uganda. Afr. Dev. Rev. Tunis-Tunis. 2010, 22, 115–148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adebosin, W.G.; Adebayo, A.A.; Mobolaji, A.W.; Ayanyemi, A.A. Determinants of Farmers’ Demand for Micro Finance: The Case of a rural community in Nigeria. J. Econ. Sustain. Dev. 2013, 4, 5. [Google Scholar]

- Matsvai, S.; Mushunje, A.; Tatsvarei, S. Technical efficiency impact of microfinance on small scale resettled sugar cane farmers in Zimbabwe. Cogent Econ. Financ. 2022, 10, 2017599. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kampala. Housing Microfinance Can Help Poor People to Build Better Homes. The Economist. 2019. Available online: https://www.economist.com/finance-and-economics2019/07/18/housing-microfinance-can-help-poor-people-build-better-homes (accessed on 27 August 2024).

- Colombo, and Nachchikuda. “Microfinance Is Driving many Sri Lankan Borrowers to Despair”. The Economist. 2019. Available online: https://www.economist.com/finance-and-economics/2019/08/15/microfinance-is-driving-many-sri-lankan-borrowers-to-despair (accessed on 13 October 2024).

- Kiriti-Nganga, T.W. Microfinance and Poverty alleviation: How effective is it in Alleviating Gender Based Poverty? In Poverty, Poverty Alleviation and Social Disadvantage: Analysis, Case Studies and Policies; Clem, T., Ed.; Serials Publications: New Dehli, India, 2007; Available online: http://erepository.uonbi.ac.ke:8080/xmlui/handle/123456789/49619 (accessed on 13 October 2024).

- de Janvry, A.; Sadoulet, E. Development Economics, 2nd ed.; Routledge: New York, NY, USA, 2021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nakano, Y.; Magezi, E.F. The impact of microcredit on agricultural technology adoption and productivity: Evidence from randomized control trial in Tanzania. World Dev. 2020, 133, 104997. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bangura, S.; Sesay, A.K.; Bah, D.K.S.C.J.; Mansaray, I. The Impact of Microfinance on Smallholder Agricultural Productivity in Sierra Leone: A Case Study of Koinadugu District. Glob. Sci. J. 2020, 8. Available online: http://www.globalscientificjournal.com (accessed on 15 May 2024).

- Zimbabwe Association of Microfinance Institutions (ZAMFI) Creating Sustainable Microfinance’. Performance Report of the Microfinance Sector (December 2023). Available online: https://zamfi.org/download/analysis-of-the-performance-of-the-microfinance-sector-in-zimbabwe-dec-2023/ (accessed on 15 August 2024).

- Matsvai, S.; Mushunje, A.; Tatsvarei, S. Characterisation of smallholder resettled sugarcane farmers their perceptions towards microfinance in Zimbabwe (Chiredzi). J. Agribus. Rural Dev. 2021, 3, 293–306. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Asante-Addo, C.; Mockshell, J.; Zeller, M.; Siddig, K.; Egyir, I.S. Agricultural credit provision: What really determines farmers’ participation and credit rationing? Agric. Financ. Rev. 2017, 77, 239–256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dang, H.D.; Dam, A.H.; Pham, T.T.; Nguyen, T. Determinants of credit demand of farmers in Lam Dong, Vietnam. Agric. Financ. Rev. 2019, 80, 255–274. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dube, L.; Mariga, T.; Mrema, M. Determinants of Access to Formal Credit by SmallholderTobacco Farmers in Makoni District, Zimbabwe. Greener J. Agric. Sci. 2015, 5, 33–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Robinson, M. The Microfinance Revolution: Sustainable Finance for the Poor; World Bank: Washington, DC, USA, 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Fecke, W.; Feil, J.; Musshoff, O. Determinants of loan demand in agriculture: Empirical evidence from Germany. Agric. Financ. Rev. 2016, 76, 462–476. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rweyemamu, D.C.; Kimaro, M.P.; Urassa, O.M. Assessing Microfinance Services in the Agriculture Sector Development: A Case of Semi-Formal Financial Institutions in Tanzania; Economics and Social Research Foundation: Dar es Salaam, Tanzania, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Pendame, S.; Akotey, J.O. The effect of a moveable collateral registry on MSME access to finance: Evidence from Malawi. Cogent Econ. Financ. 2023, 11, 2163873. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vishwanatha; Eularie, M. Access to microcredit for smallholder agricultural producers in Rwanda (Africa): Emerging challenges and issues. J. Commer. Manag. Thought 2017, 8, 452. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mamuye, W. Determinants of Smallholder Farmers Participation in Formal Credit and Challenges Faced by Institutions: The Case of Mojana Wodera District, Amhara Region, Ethiopia. Int. J. Financ. Bank. Res. 2021, 7, 9–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sebatta, C.; Wamulume, M.; Mwansakilwa, C. Determinants of smallholder farmers’ access to agricultural finance in Zambia. J. Agric. Sci. 2014, 6, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chikodzi, D.; Murwendo, T.; Malvern, F.S. Climate Change and Variability in Southeast Zimbabwe: Scenarios and Societal Opportunities. Am. J. Clim. Change 2013, 2, 36–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gujarati, N. Basic Econometrics, 4th ed.; McGraw Hill Publishing Company: New Delhi, India, 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Silong, A.K.F.; Gadanakis, Y. Credit sources, access and factors influencing credit demand among rural livestock farmers in Nigeria. Agric. Financ. Rev. 2019, 80, 68–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sangwan, S.; Nayak, N.C. Factors influencing the borrower loan size in microfinance group lending: A survey from Indian microfinance institutions. J. Financ. Econ. Policy 2021, 13, 223–238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Asiamah, T.A.; Steel, W.F.; Ackah, C. Determinants of credit demand and credit constraints among households in Ghana. Heliyon 2021, 7, e08162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tura, E.G.; Kenea, T.; Kaso, T. Determinants of demand for credit among wheat and teff smallholder farmers in central of Ethiopia (Arsi and South West Shewa). Am. Res. J. Bus. Manag. 2017, 3, 17. [Google Scholar]

- Osano, H.M.; Languitone, H. Factors influencing access to finance by SMEs in Mozambique: Case of SMEs in Maputo central business district. J. Innov. Entrep. 2016, 5, 1–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nasereldin, Y.A.; Chandio, A.A.; Osewe, M.; Abdullah, M.; Ji, Y. The Credit Accessibility and Adoption of New Agricultural Inputs Nexus: Assessing the Role of Financial Institutions in Sudan. Sustainability 2023, 15, 1297. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saqib, S.E.; Ahmad, M.M.; Panezai, S. Landholding size and farmers’ access to credit and its utilisation in Pakistan. Dev. Pract. 2016, 26, 1060–1071. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mason, D.R. Who gets what? Determinants of loan size and credit rationing among microcredit borrowers: Evidence from Nicaragua. J. Int. Dev. 2014, 26, 77–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Behr, P.; Entzian, A.; G€uttler, A. How do lending relationships affect access to credit and loan conditions in microlending? J. Bank. Financ. 2011, 35, 2169–2178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Variable Description | Probit | Tobit |

|---|---|---|

| Demographics | ||

| Gender (1 if male and 2 if female-GEN) | +/- | +/- |

| Household size (number of people in the household-HHS) | + | + |

| Primary education (Eductn2) | + | +/- |

| Secondary education (Eductn3) | + | +/- |

| Tertiary education (Eductn4) | + | - |

| Age (age of farmers years-AGE) | + | + |

| Marital status (1 if married and 0 if not-MS) | + | +/- |

| Financial/Institutional Characteristics | ||

| Interest rate (rate of interest charged on micro-borrowing-INTR) | - | - |

| Grace period (number of months before the first installment-GP) | + | + |

| Payback period (number of months taken to clear the debt-PBP) | + | + |

| Application and processing charges (1 if low and 2 if high-APC) | + | + |

| Micro-savings (1 for micro-savers and 0 for non-savers in Probit and the value of farmer’s previous season savings in Tobit-MSAV) | - | - |

| Frequency of borrowing (times the farmer borrowed from MFIs-FREQ) | + | + |

| Off-farm income (1 for having off-farm income and 0 if otherwise (in Probit) and value of farmer’s off-farm income (in Tobit)-OFY) | +/- | +/- |

| Microfinance risk perception (1-risk neutral and 0-for risk averse-RIS) | + | - |

| General Farming Characteristics | ||

| Extension visits (number of visits per sugarcane farming season-EXT) | + | +/- |

| Farming experience (years of sugarcane farming-EXP) | + | + |

| Operation expenses (value of the seasonal operating expenses-OPE) | + | + |

| Household farming assets (1 for having assets and 0 if otherwise (in Probit) and the net book value of farming assets (in Tobit)-HFA) | +/- | +/- |

| Membership to farmers associations (1-members and 0 if not-MFA) | +/- | +/- |

| Land Size (continuous variable in hectares-LN) | + | + |

| Nature of farming (dummy where fulltime = 1 and part-time = 0-NOF) | + | +/- |

| Distance to the nearest MFI (in kilometers-DIS) | - | - |

| Characteristic (Variable) N = 370 | Mean | Stnd Dev. | Min | Max |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Amount borrowed (AMNT) | $5016 | $2440 | $1275 | $10,000 |

| Age (years) | 60.84 | 15.69 | 29 | 89 |

| Operating costs ($) | $48,201.50 | $18,641.50 | 13,966 | 125,464 |

| Household size (number) | 8.4 | 3.0367 | 2 | 17 |

| Payback period (months) | 3.8645 | 3.2696 | 2 | 12 |

| Distance to the nearest MFI in km | 21.968 km | 15.5291 | 2 | 64 |

| Interest rate (%) | 11.65% | 1.1527 | 10.5 | 12.8 |

| Grace period (months) | 3.1028 | 3.2830 | 1 | 14 |

| Land size (ha) | 11.4324 | 3.91042 | 4 | 25 |

| Experience (years) | 11.1135 | 5.1169 | 2 | 19 |

| Off-farm income (OFY) | $3956 | 2.971 | $350 | $17,893 |

| Micro-savings value (MSAV) | $1274 | 1.079 | $175 | $11,850 |

| Extension visits (number) | 4 | 3.502 | 1 | 15 |

| Household farming assets @ estimated net book value (HFA) | $13,873 | 9.343 | $3850 | $105,000 |

| Frequency of borrowing (FREQ) | 5 | 2.973 | 1 | 7 |

| Variable (N = 370) | Description | Unit | Participants | Non-Participants |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Gender (GEN) | Male | 1 | 150 | 119 |

| Female | 0 | 64 | 37 | |

| Marital status (MS) | Married | 1 | 149 | 65 |

| Single | 0 | 126 | 30 | |

| Off-farm income (OFY) | Have Off-farm Income | 1 | 71 | 143 |

| No Off-farm Income | 0 | 107 | 49 | |

| Nature of farming (NOF) | Full time | 1 | 165 | 138 |

| Part time | 0 | 49 | 18 | |

| Farmers association membership (MFA) | Member | 1 | 184 | 128 |

| Not a Member | 0 | 30 | 28 | |

| Risk attitude/perception (RIS) | Neutral | 1 | 162 | 41 |

| Averse | 0 | 52 | 115 | |

| Savings (MSA) | Microsavers | 1 | 91 | 46 |

| Non-microsavers | 0 | 123 | 110 | |

| Education (Eductn1, 2 &3) | No Schooling | 0 | 36 | 30 |

| Primary | 1 | 39 | 64 | |

| Secondary | 2 | 66 | 49 | |

| Tertiary | 3 | 73 | 12 |

| Probit Results | Tobit Results | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Number of Obs | 370 | 214 | ||||

| Prob > chi2 | 0.0000 | 0.0000 | ||||

| LR chi2 | 68.60 | 206.54 | ||||

| Pseudo-R2 | 0.6462 | 0.536 | ||||

| Log-likelihood | −89.115 | −89.1146 | ||||

| Kt | Coeff | dy/dx | ᵶ | coeff | Stn | t |

| Cons | −1.125 | −6.94 *** | −8667.51 | −2.50 ** | ||

| Demographic Characteristics | ||||||

| GEN | −0.129 | −0.044 | −0.43 | −67.5 | 64.64 | −1.04 |

| HHS | 0.018 | 0.006 | 0.36 | −56.57 | 39.394 | −1.44 |

| Eductn2 | 0.522 | 0.18 | 1.28 | 0.108 | 0.104 | 1.17 |

| Eductn3 | 1.019 | 0.351 | 2.19 ** | 0.051 | 0.021 | 2.18 ** |

| Eductn4 | 1.819 | 0.627 | 3.60 *** | 0.132 | 0.239 | 5.36 *** |

| AGE | −0.302 | −0.07 | −4.34 *** | −0.724 | 0.281 | −2.04 ** |

| AGE2 | 0.003 | 0.001 | 3.95 *** | 0.016 | 0.387 | 0.73 |

| MS | −0.111 | −0.038 | −0.35 | 0.361 | 0.458 | 1.39 |

| Financial Characteristics | ||||||

| INTR | −1.545 | −0.845 | −3.44 *** | −937.96 | 297.93 | −2.50 *** |

| GP | 0.216 | 0.192 | 3.01 *** | 1414.55 | 262.28 | 5.39 *** |

| PBP | −0.314 | −0.026 | −4.03 *** | −829.029 | 65.41 | −1.27 |

| APC | −0.092 | 0.182 | −3.04 *** | 0.1915 | 90.811 | 5.62 *** |

| MSAV | 0.033 | 0.0114 | 0.14 | −518.82 | 310.14 | −1.67 * |

| FREQ | 0.059 | 0.232 | 0.912 | 0.153 | 0.050 | 2.075 ** |

| OFY | −0.4 | −0.155 | −1.73 * | 458.98 | 239.24 | 1.92 * |

| RIS | 1.077 | 0.3939 | 4.95 *** | 1366.53 | 264.4 | 5.17 *** |

| General Farming Characteristics | ||||||

| EXT | 0.148 | 0.051 | 3.96 *** | −35.982 | 37.7 | −0.95 |

| EXP | −0.074 | −0.026 | −2.24 ** | 1.027 | 0.164 | 6.17 *** |

| OPC | 0.001 | 0.00002 | 4.84 *** | 0.040 | 0.008 | 4.81 *** |

| HFA | 1.408 | 0.485 | 4.53 *** | 1577.68 | 310.46 | 5.08 *** |

| MFA | 0.358 | 0.124 | 1.17 | 4.753 | 1.257 | 6.38 *** |

| DIS | 0.007 | 0.0025 | 0.93 | −0.092 | 0.182 | −1.09 |

| LN | 0.136 | 0.0436 | 18.45 *** | 561.21 | 125.83 | 4.46 *** |

| NOF | −0.25 | 0.172 | −0.672 | 0.435 | 0.138 | 4.32 *** |

| Variable | Determinants of Borrowing (Probit) | Determinants of Microcredit Size (Tobit) |

|---|---|---|

| Demographic Determinants | ||

| Secondary education | positive | positive |

| Tertiary education | positive | positive |

| Age | Positive to negative | positive |

| Financial/Institutional Determinants | ||

| Interest rate | negative | negative |

| Payback period | positive | positive |

| Application and processing charges | negative | positive |

| Savings | no effect | negative |

| Frequency of borrowing | no effect | positive |

| Off-farm income | negative | positive |

| Microfinance risk perception | positive | positive |

| General Farming Characteristics/Determinants | ||

| Extension visits | positive | no effect |

| Farming experience | negative | positive |

| Operation expenses | positive | positive |

| Household farming assets | Positive | positive |

| Membership to farmers associations | no effect | Positive |

| Land size | positive | Positive |

| Nature of farming | no effect | positive |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Matsvai, S. Determinants of Microfinance Demand (Evidence from Chiredzi Smallholder Resettled Sugarcane Farmers in Zimbabwe). Sustainability 2024, 16, 9752. https://doi.org/10.3390/su16229752

Matsvai S. Determinants of Microfinance Demand (Evidence from Chiredzi Smallholder Resettled Sugarcane Farmers in Zimbabwe). Sustainability. 2024; 16(22):9752. https://doi.org/10.3390/su16229752

Chicago/Turabian StyleMatsvai, Simion. 2024. "Determinants of Microfinance Demand (Evidence from Chiredzi Smallholder Resettled Sugarcane Farmers in Zimbabwe)" Sustainability 16, no. 22: 9752. https://doi.org/10.3390/su16229752

APA StyleMatsvai, S. (2024). Determinants of Microfinance Demand (Evidence from Chiredzi Smallholder Resettled Sugarcane Farmers in Zimbabwe). Sustainability, 16(22), 9752. https://doi.org/10.3390/su16229752