1. Introduction

The United Nations Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs), particularly goal 13 (climate action), emphasize the urgent need to take action to mitigate climate change and promote sustainable development. Carbon trading, by establishing a market mechanism for reducing greenhouse gas emissions (GHGs), provides a key policy tool for achieving these goals. Therefore, implementing carbon trading policies is essential for balancing economic development with environmental management and promoting a transition to a more sustainable economy. As global climate change intensifies, China faces mounting pressure to reduce emissions both domestically and internationally. Being the largest developing country globally and a significant contributor to GHGs, China’s carbon dioxide (CO2) emissions from fuel combustion reached 10,648 MtCO2 in 2021, making it the highest globally. The Chinese government formally committed to its “dual carbon” goals in September 2020: achieving peak CO2 emissions by 2030 and carbon neutrality by 2060.

GHGs from production are driven by consumer demand along the supply chain, with developed countries exhibiting a higher share of consumption-based emissions relative to production-based emissions [

1]. In China, household consumption accounts for approximately 26% of total energy use and 30% of CO

2 emissions [

2]. From the perspective of sectoral CO

2 emissions, housing is a significant contributor, with emissions concentrated in the building sector. The residential buildings in China face growing demand for home energy services [

3], which necessitates large amounts of primary energy (e.g., coal) and secondary energy (e.g., electricity), leading to substantial CO

2 emissions from domestic buildings [

4]. Many scholars argue that the potential for emission reductions in residential buildings is considerable. Zhou et al. (2018) emphasized that improving building energy efficiency holds significant practical value in reducing CO

2 emissions [

5]. Cha et al. (2024) proposed optimizing heating, ventilation, and air conditioning (HVAC) systems to reduce household carbon footprints, while also highlighting the great potential of integrating renewable energy in the household sector [

6]. Additionally, the efficiency of the HVAC system is significantly impacted by the performance of variable refrigerant flow (VRF) systems. Based on performance and metrics, such as accuracy, precision, sensitivity, computation time, and the confusion matrix, Es-sakali et al. (2024) validated that the CACMMS (Cloud Air Conditioning Monitoring and Management System), which incorporates advanced fault detection and diagnosis strategies in a real-world building, is effective in addressing faults in VRF systems and enhancing the overall efficiency of HVAC systems [

7]. Furthermore, Chen et al. (2023) contended that fault detection and diagnostics are essential to ensuring the reliable operation of HVAC systems and preventing energy waste [

8]. Therefore, reducing CO

2 emissions linked to household consumption is crucial for expanding carbon reduction efforts under China’s dual-carbon goals [

9].

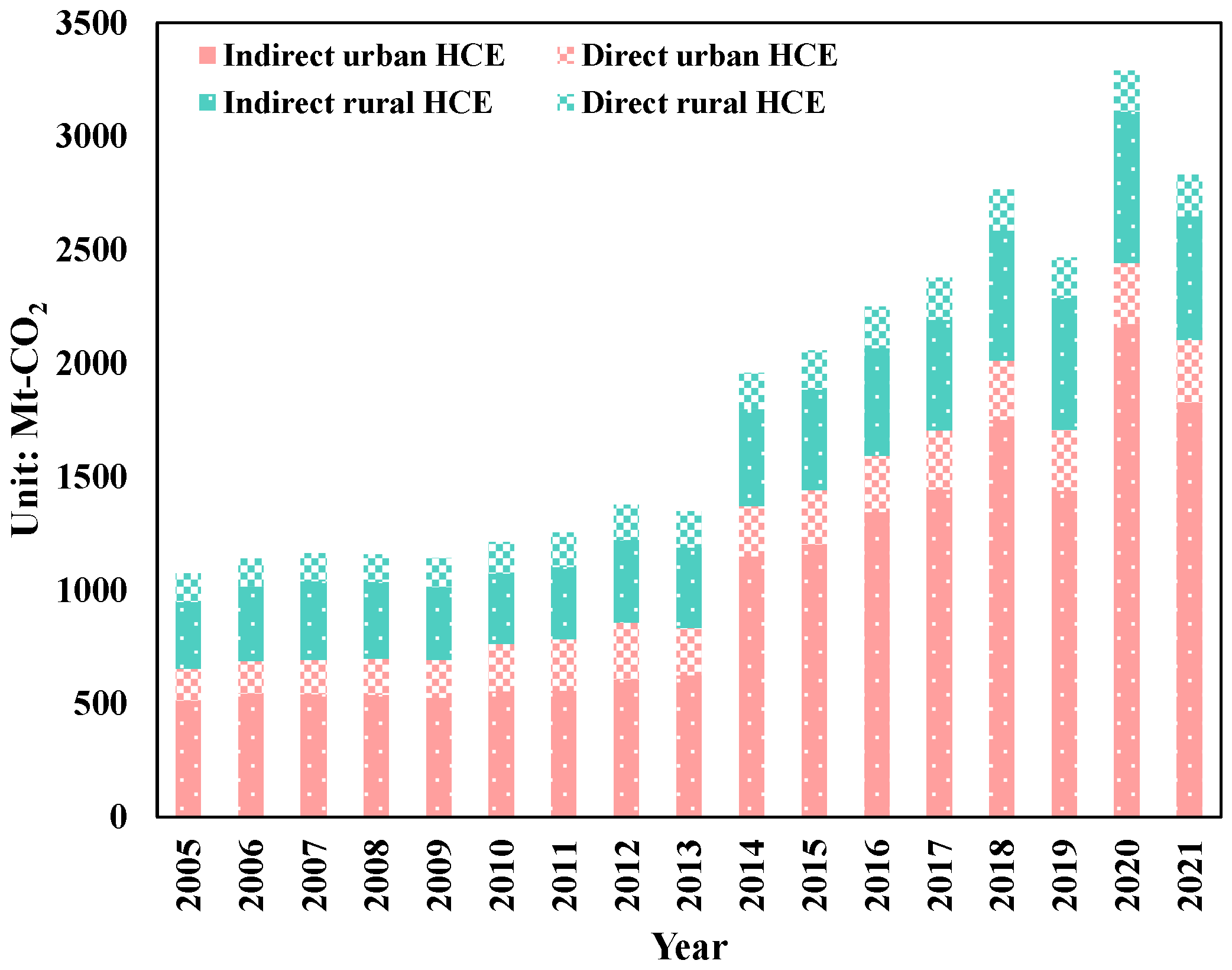

Economic disparities between urban and rural regions are obvious in income levels, lifestyle choices, consumption structures, and other factors [

10], leading to significant differences in the CO

2 emissions generated from household consumption. The rapid urbanization in China has fueled income growth and the increasing concentration of energy-intensive sectors in cities, resulting in more carbon-intensive lifestyles among urban households. In 2012, urban households, which made up 53% of the population, were responsible for 75% of national household CO

2 emissions (HCE) [

11]. Rural household consumption has also expanded, with rural per capita consumption increasing from 6991 yuan in 2010 to 13,713 yuan in 2020, reflecting a growth rate of 1.96 times. However, rural households exhibit distinct consumption patterns: a higher proportion of their spending goes toward basic needs, and their energy consumption relies more on traditional energy sources.

The emergence of carbon trading is a critical response to the global climate crisis, serving as a key tool for advancing global climate governance and promoting low-carbon development worldwide [

12,

13]. The fundamental principle of carbon trading involves the transfer of CO

2 emission permits, treated as a scarce resource, thereby raising the cost of emissions and promoting reduction efforts. China began developing its carbon trading market in 2011, launching operations in 2013, and transitioning from regional pilots to a national carbon market in 2021 [

14]. Currently, China’s carbon trading market primarily encompasses major emission-intensive sectors, including petrochemicals, chemicals, building materials, steel, and power generation. Carbon trading facilitates reduce emissions in these sectors by optimizing energy use, lowering carbon intensity, and fostering technological innovation [

15]. However, when emission costs are incorporated into production costs, businesses often pass a portion of these costs onto consumers. In this way, carbon trading indirectly affects household consumption patterns by influencing the pricing mechanism and the supply–demand dynamics of energy and commodities, ultimately impacting HCE.

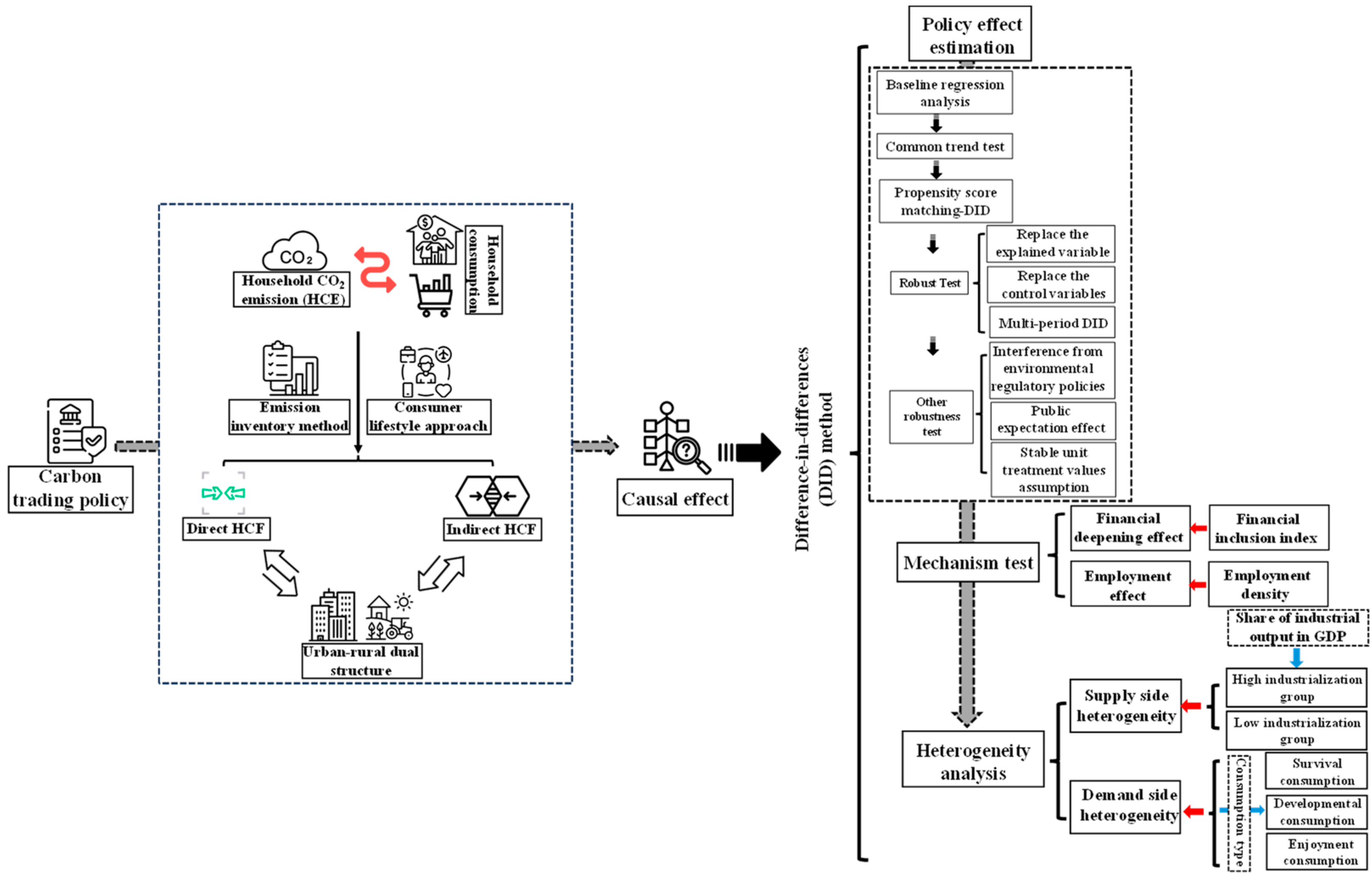

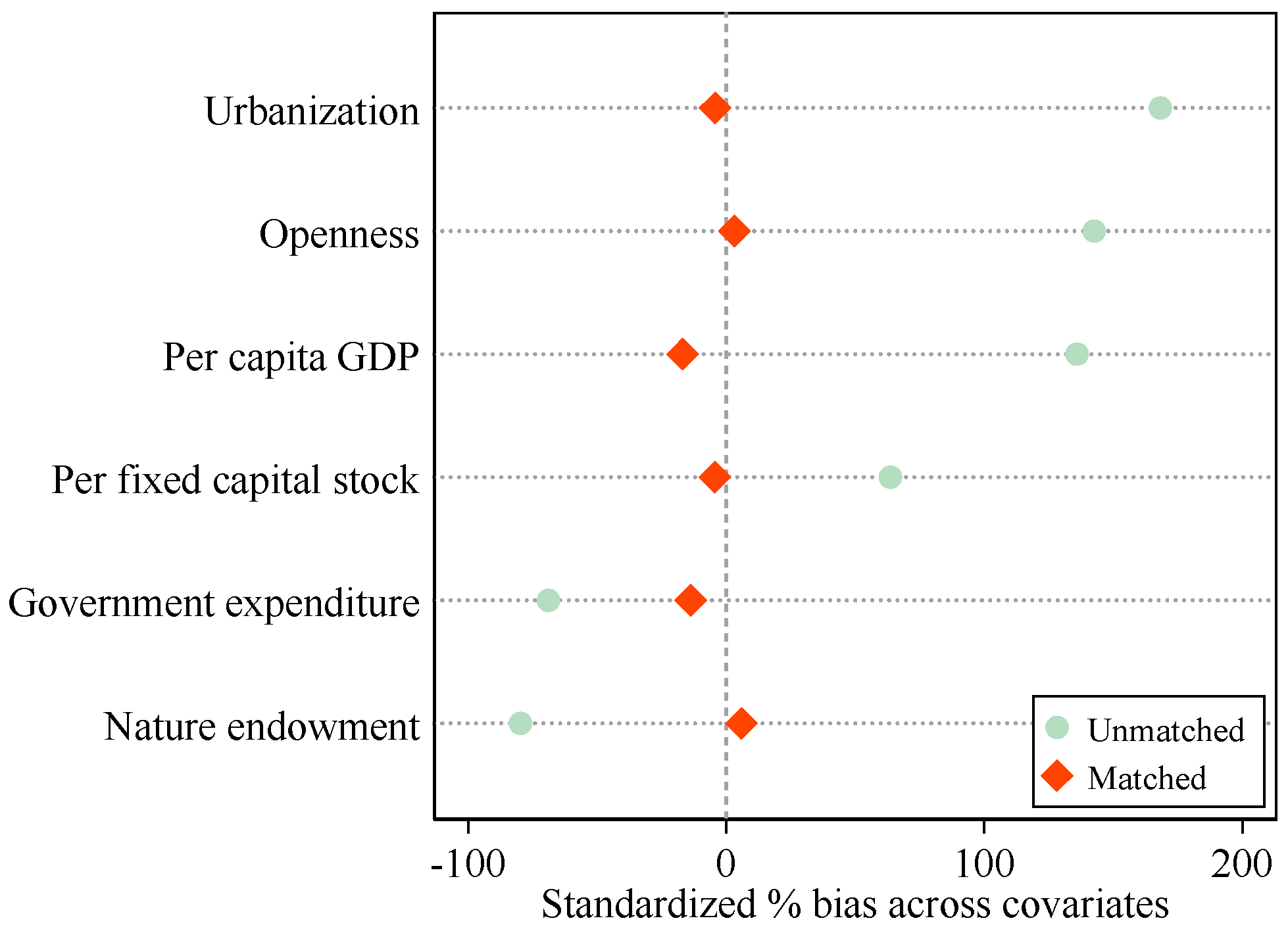

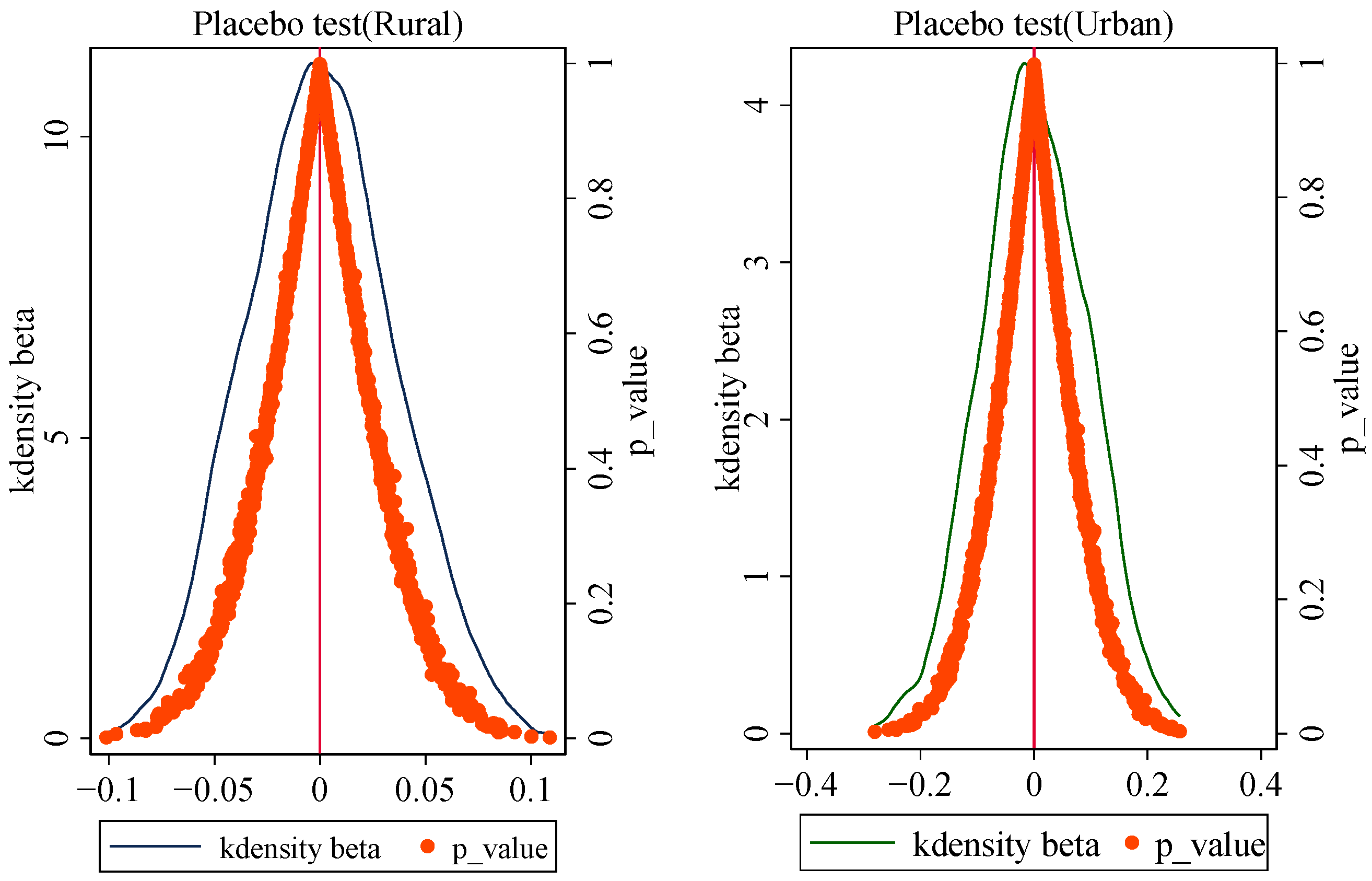

The success of carbon trading policies in lowering high-carbon emissions is vital for meeting China’s dual carbon targets. The purpose of this study is to comprehensively assess the impact of market-oriented environmental policies on HCE from both urban and rural household in China. Using the carbon trading policies introduced in 2013 as a quasi-natural experiment and accurately measuring urban and rural HCE from 2005 to 2021, we employ the difference-in-differences (DID) method to estimate the heterogeneous effects of these policies on HCE. First, utilizing a recalculated provincial HCE dataset that distinguishes between urban and rural areas, we extend the scope of carbon trading policies to the consumption side. Second, we aim to clarify the transmission mechanisms through which carbon trading policies affect HCE, while also investigating the heterogeneity of these effects on the supply side and demand side. Finally, given the potential inequality in policy outcomes caused by China’s urban–rural dual structure, we explore disparities in the effect of carbon trading policies across regions. Understanding the effectiveness of carbon trading policy in mitigating consumption-based emissions can offer fresh insights for the formulation of governmental environmental policies. In addition, by addressing regional carbon inequality, this study contributes to the broader research on equitable carbon reduction strategies.

This study provides multiple marginal contributions to the understanding of sustainable development under China’s dual carbon goals and the field of environmental economics. First, we recalculate the most recent provincial-level CO

2 emission dataset for urban and rural household consumption, identifying and verifying the carbon reduction effect of carbon trading policies on consumption-based emissions. To date, most evaluations of carbon trading policies have focused on production-based emissions, with little attention paid to their impact on the consumption side [

16,

17]. This study extends the impact boundary of carbon trading policies to the consumption side, significantly enriching and broadening the literature on environmental policy impact assessments. Second, this study reveals the transmission process and mechanisms through which carbon trading policies reduce HCE, examining the heterogeneity of market-based environmental policies on both the supply and demand sides. This provides valuable insights for the government in further broadening the scope of environmental policy. Third, from the perspective of China’s urban–rural dual structure, this study innovatively explores the differences in the intensity of carbon trading policies’ impact on HCE between urban and rural areas. Previous research has mainly focused on the single effect of carbon trading policies, neglecting the potential policy inequality that may arise from urban–rural differences. This study deepens the understanding of carbon trading policies and introduces a new perspective for addressing regional carbon inequality

The structure of this paper is as follows:

Section 2 provides a comprehensive review of the relevant literature;

Section 3 outlines the empirical strategy and data selection.

Section 4 discusses the main findings.

Section 5 provides conclusions with policy implications.

5. Discussion

We conducted a comprehensive assessment of the positive impacts of carbon trading policies on HCE in urban and rural areas, addressing a less explored area in the literature. Existing studies have primarily examined the effects of China’s carbon trading pilots in reducing production-based emissions in energy-intensive industries and overall regional CO

2 emissions [

17,

33,

36,

77,

78] and have demonstrated the positive role of carbon trading policies in reducing emissions based on the Porter hypothesis [

37]. However, some scholars argue that the impact of carbon market policies on reducing consumption-based emissions is limited [

79]. In contrast, our research confirms the positive effect of carbon trading policies on consumption related emissions and emphasizes the urban-rural disparity. This fairness perspective, grounded in cross-sectional comparisons, is critical [

80]. Furthermore, our study captures the more pronounced long-term adjustment effects of these policies on households, revealing the specific ways in which policy intensity evolves over time. Studies on the diminishing effects of carbon taxes or carbon trading systems underscore this point [

81]. This long-term perspective provides valuable insights into the broader impacts of carbon trading policies on sustainable development under China’s dual carbon goals.

Previous literature has mainly focused on the direct regulatory effects of carbon trading on industrial output and technological innovation [

14,

35,

37], with limited consideration of how these impacts are transmitted to household consumption behavior. We identified two transmission mechanisms—finance and employment—which are crucial for understanding how carbon trading policies affect HCE. On the supply side, as financial markets deepen, increasing amounts of social capital flow into environmental protection, energy-saving technologies, and clean energy sectors, gradually reducing the carbon intensity of products. On the demand side, financial deepening primarily influences household consumption behavior. Urban households, due to higher levels of education and income, are more inclined toward low-carbon consumption practices [

65]. Additionally, housing is closely tied to financial liabilities for Chinese households, which explains why financial deepening has different impacts between urban and rural areas. This paper argues that although carbon trading policies do not directly affect income, their implementation comes at the cost of rural residents’ employment opportunities, as they are more likely to lose jobs. This ultimately leads to environmental inequality, consistent with the literature on whether environmental regulations disproportionately impact traditionally disadvantaged regions [

35,

75].

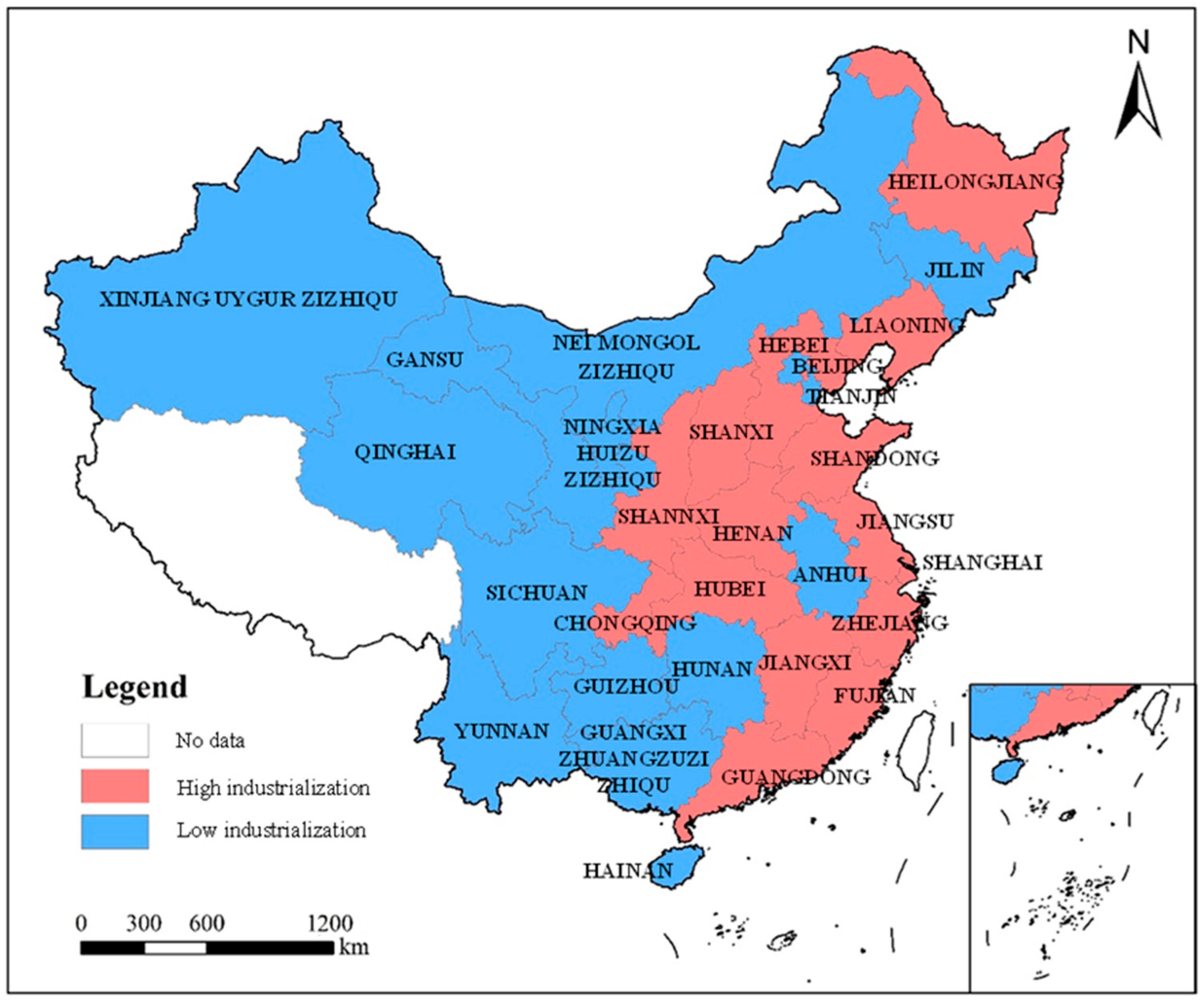

By distinguishing between the supply-side and demand-side effects, we provide a more nuanced understanding of carbon trading policies. The broader literature on carbon markets reveals how regional factors lead to varying policy impacts [

33,

34]. Our findings offer a more interesting conclusion: highly industrialized regions are more significantly affected by such policies than less industrialized regions. When carbon trading policies encourage both businesses and residents to transition to low-carbon energy, the negative impact on consumption-based emissions is more pronounced among low-industrialization groups. Similarly, this heterogeneity issue also manifests in urban-rural differences. Compared to rural households with lower income elasticity, wealthier urban households respond differently to the price signals of carbon trading [

24,

42]. These varying responses provide policymakers with more detailed insights, helping them design complementary policies to address the distinct needs and challenges of different regions.

China is committed to improving the urban-rural dual structure, and enhancing the welfare of rural residents is crucial. At the very least, carbon trading policies should not exacerbate their burdens [

82]. Research on carbon policies also emphasizes the potential unequal impacts across different regions or socioeconomic groups [

83,

84]. Unlike much of the literature that holds a pessimistic view of carbon policies, our study confirms the differentiated impacts of market-based policies on the urban-rural dual structure and highlights the positive significance of these policies in reducing carbon inequality. Broadly speaking, understanding residents’ preferences for different types of consumption goods is essential to grasping the role of carbon policies [

24,

85]. Particularly in areas of subsistence consumption, as income rises, carbon policies can leverage market forces to achieve carbon redistribution, ensuring that the benefits of carbon reduction are considered through an equity lens. This finding provides valuable insights for policymakers seeking to design interventions that not only reduce carbon inequality but also promote carbon reduction.

6. Conclusions and Policy Implication

The implementation of market-oriented environmental policies, such as carbon trading, represents a critical strategy for China in reducing CO2 emissions and addressing carbon inequality. This study offers an initial exploration of carbon trading policies, with an emphasis on the consumption side. Employing a DID methodology, this study empirically analyzes the heterogeneous impacts of carbon trading policies on HCE, and investigates the underlying mechanisms that explain these variations. The principal outcomes of this research are outlined below:

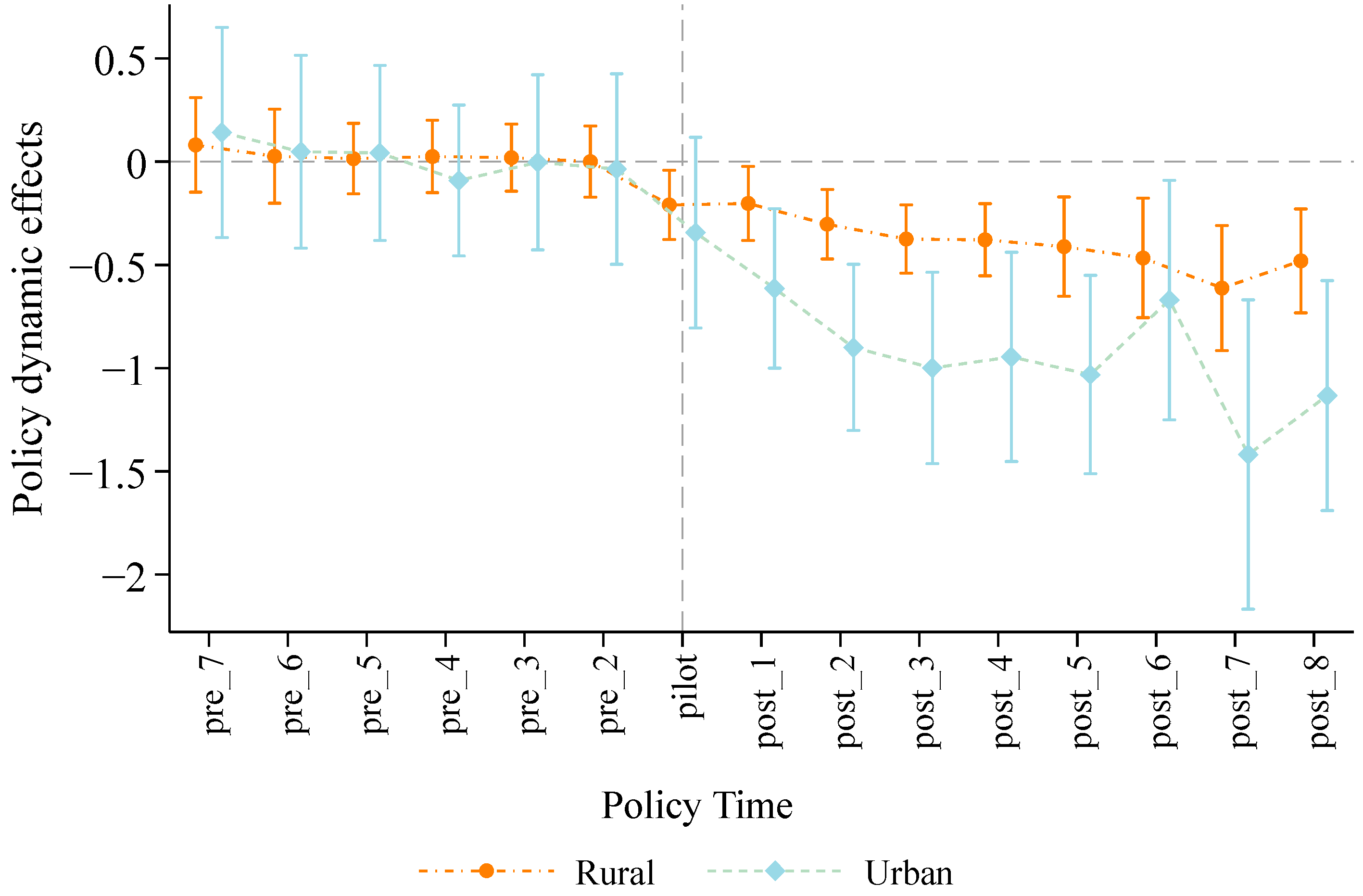

The implementation of carbon trading policies has led to a notable reduction in HCE, with the most pronounced effects observed in urban areas. Although the policy impact weakened over time, the findings suggest a lasting influence on promoting low-carbon lifestyles among households.

Financial deepening and employment effects are identified as the primary channels through which the carbon trading market influences HCE. These transmission mechanisms have a more substantial impact on urban households.

The policy effects differ markedly between urban and rural areas, with carbon trading policies most effectively reducing HCE related to survival consumption, thereby helping to alleviate urban-rural carbon inequality from the demand side.

In light of the results, the following policy implications are suggested:

First, given the inhibitory effects of carbon trading policies on China’s HCE, policymakers should fully leverage market mechanisms in environmental regulation and further advance market-based incentive policies. Accelerating the establishment of an integrated carbon trading system is crucial for promoting low-carbon lifestyles and supporting China’s objectives of reducing carbon emissions and achieving carbon neutrality.

Second, improving the coordination between carbon trading policies and household consumption is of significant practical importance for alleviating urban-rural carbon inequality. Policymakers should account for the urban-rural dual structure to ensure equitable benefits for rural households. As market-oriented environmental policies may not always promote fair distribution, complementary carbon distribution policies should be designed to prevent the widening of carbon inequality.

Lastly, carbon reduction strategies should be tailored to the cost-effectiveness of household consumption patterns, considering the level of regional industrialization. In highly industrialized regions, regulatory policies should complement market mechanisms to achieve more substantial emissions reductions at lower costs. In less industrialized regions, the application of market-based environmental policies should be expanded to promote cost-effective carbon reduction. Furthermore, policies should target high-carbon products related to household subsistence consumption, adapting to regional variations in consumption needs.

7. Limitations and Future Perspectives

Although one of the study objectives was to explore the impact of China’s carbon trading policy on consumption-based emissions, we acknowledge that there is scope for more precise measurement of HCE. Given that a key focus of our research is to examine changes in the structure of HCE across different provinces in China, we chose the CLA to estimate indirect CO2 emissions based on annual household consumption data. This method allows us to capture the structural dynamics of consumption emissions over time at the provincial level, which is essential for our analysis. However, this method, admittedly, does not account for the influence of factors such as technological conditions of production and supply chain structures on HCE. In future research, we will attempt to expand the scope of our CO2 emission estimations, such as environmental extended input–output analysis framework. Moreover, this study focused on China’s provincial-level administrative units, which limits the overall sample size. In future work, we aim to extend the geographical scope to include city-level administrative units across China, which will ensure a more robust and diverse sample for analysis.

Last but not least, during the review process, we received constructive feedback from reviewers, and based on these valuable comments, we made several modifications to improve the study’s clarity and depth. First, we have added a detailed introduction to HCE in the background section to provide a more comprehensive research context. Second, we restructured the introduction to outline the research framework more effectively. Third, we reorganized the literature review to reflect a more thorough understanding of prior work. Lastly, we expanded the discussion of key findings to offer additional insights into the study’s implications. These improvements significantly enhance the study’s contribution to the field and address the reviewers’ valuable suggestions.