Design and Test of a Multi-Media Web Platform Prototype Based on People’s Preferences to Increase Cultural Heritage Awareness

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Case Area: Strijp-S, Eindhoven

2.2. The Multi-Media Platform Prototype

2.2.1. Platform Structure

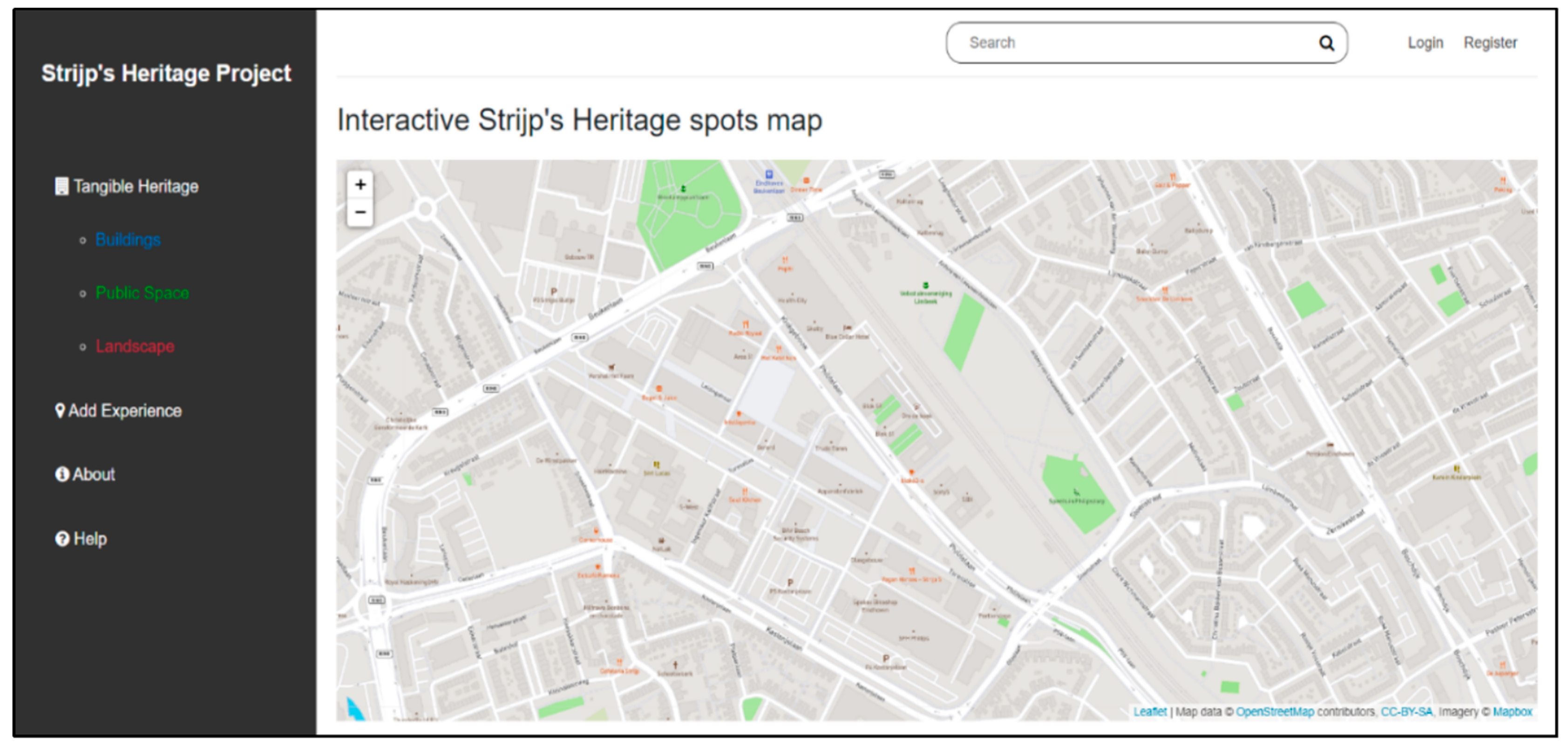

2.2.2. Multi-Media Web Platform Interface

2.3. Survey

Data Collection

3. Results

3.1. Sample Characteristics

3.2. Comments on the Multi-Media Platform Prototype

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- UNESCO World Heritage Center. Basic Texts of the 1972 World Heritage Convention; UNESCO: Paris, France, 2005; pp. 1–234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Steinberg, F. Conservation and rehabilitation of urban heritage in developing countries. Habitat. Int. 1996, 20, 463–475. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lussetyowati, T. Preservation and Conservation through Cultural Heritage Tourism. Case Study: Musi Riverside Palembang. Procedia Soc. Behav. Sci. 2015, 184, 401–406. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Frey, B.S.; Briviba, A. A policy proposal to deal with excessive cultural tourism. Eur. Plan. Stud. 2021, 29, 601–618. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ashworth, G. Preservation, Conservation and Heritage: Approaches to the Past in the Present through the Built Environment. Asian Anthropol. 2011, 10, 1–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaddu, S. Collaboration in Digitising Cultural Heritage as a strategy to sustain access and sharing of cultural heritage information in Uganda. Libr. Theory Res. 2015, 1–14. [Google Scholar]

- Ricart, S.; Ribas, A.; Pavón, D.; Gabarda-Mallorquí, A.; Roset, D. Promoting historical irrigation canals as natural and cultural heritage in mass-tourism destinations. J. Cult. Herit. Manag. Sustain. Dev. 2019, 9, 520–536. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cassel, S.H.; Pashkevich, A. World Heritage and tourism innovation: Institutional frameworks and local adaptation. Eur. Plan. Stud. 2014, 22, 1625–1640. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dragoni, M.; Tonelli, S.; Moretti, G. A knowledge management architecture for digital cultural heritage. J. Comput. Cult. Herit. 2017, 10, 15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.-D. Cultural events and cultural tourism development: Lessons from the European Capitals of Culture. Eur. Plan. Stud. 2014, 22, 498–514. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Monod, E.; Klein, H.K.; Missikoff, O.; Isari, D. Cultural heritage systems evaluation and design: The virtual heritage center of the city of Rome. In Proceedings of the Connecting the Americas. 12th Americas Conference on Information Systems, AMCIS 2006, Acapulco, México, 4–6 August 2006; pp. 1351–1360. [Google Scholar]

- Ott, M.; Pozzi, F. Towards a new era for cultural heritage education: Discussing the role of ICT. Comput. Hum. Behav. 2011, 27, 1365–1371. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barrientos, F.; Martin, J.; De Luca, C.; Tondelli, S.; Gómez-García-Bermejo, J.; Casanova, E.Z. Computational methods and rural cultural & natural heritage: A review. J. Cult. Herit. 2021, 49, 250–259. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bethapudi, A. The role of ICT in tourism industry. J. Appl. Econ. Bus. 2013, 1, 67–79. [Google Scholar]

- Cunha, C.R.; Carvalho, A.; Afonso, L.; Silva, D.; Fernandes, P.O.; Pires, L.C.; Costa, C.; Correia, R.; Ramalhosa, E.; Correia, A.I.; et al. Boosting cultural heritage in rural communities through an ICT platform: The Viv@vó Project. IBIMA Bus. Rev. 2019, 2019, 608133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Foni, A.E.; Papagiannakis, G.; Magnenat-Thalmann, N. A taxonomy of visualization strategies for cultural heritage applications. J. Comput. Cult. Herit. 2010, 3, 1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ginzarly, M.; Teller, J. Online communities and their contribution to local heritage knowledge. J. Cult. Herit. Manag. Sustain. Dev. 2020, 11, 361–380. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thekkum Kara, G.K. Developing a sustainable cultural heritage information system. Libr. Hi Tech. News 2021, 38, 17–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Di Giulio, R.; Boeri, A.; Longo, D.; Gianfrate, V.; Boulanger, S.O.M.; Mariotti, C. ICTs for Accessing, Understanding and Safeguarding Cultural Heritage: The Experience of INCEPTION and ROCK H2020 Projects. Int. J. Archit. Herit. 2021, 15, 825–843. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gupta, D.K.; Sharma, V. Enriching and enhancing digital cultural heritage through crowd contribution. J. Cult. Herit. Manag. Sustain. Dev. 2017, 7, 14–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ott, M.; Pozzi, F. ICT and cultural heritage education: Which added value? In Emerging Technologies and Information Systems for the Knowledge Society, Proceedings of the First World Summit on the Knowledge Society, WSKS 2008, Athens, Greece, 24–26 September 2008; Lecture Notes in Computer Science; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2008; Volume 5288 LNAI, pp. 131–138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dusi, N.; Ferretti, I.; Furini, M. A transmedia storytelling system to transform recorded film memories into visual history. Entertain. Comput. 2017, 21, 65–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lazzeretti, L.; Oliva, S.; Innocenti, N.; Capone, F. Rethinking culture and creativity in the digital transformation. Eur. Plan. Stud. 2022, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moitra, A.; Das, V.; Team, G.V.; Kumar, A.; Seth, A. Design lessons from creating a mobile-based community media platform in rural India. In Proceedings of the 8th International Conference on Information and Communication Technologies and Development, University of Michigan, Ann Arbor, MI, USA, 3–6 June 2016. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pecchioli, L.; Carrozzino, M.; Mohamed, F.; Bergamasco, M.; Kolbe, T.H. ISEE: Information access through the navigation of a 3D interactive environment. J. Cult. Herit. 2011, 12, 287–294. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Pyae, A. Understanding the role of culture and cultural attributes in digital game localization. Entertain. Comput. 2018, 26, 105–116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maietti, F.; Di Giulio, R.; Medici, M.; Ferrari, F.; Piaia, E.; Brunoro, S. Accessing and Understanding Heritage Buildings through ICT. The INCEPTION Methodology Applied to the Istituto degli Innocenti. Int. J. Archit. Herit. 2021, 15, 921–930. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rubegni, E.; Di Blas, N.; Paolini, P.; Sabiescu, A. A format to design narrative multimedia applications for cultural heritage communication. In Proceedings of the 201 ACM Symposium on Applied Computing, Sierre, Switzerland, 22–26 March 2010; pp. 1238–1239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Varriale, L.; Volpe, T.; Noviello, V. Enhancing cultural heritage at the time of the COVID-19 outbreak: An overview of the ICT strategies adopted by museums in the Campania Region of Italy. In Tourism Destination Management in a Post-Pandemic Context; Emerald Publishing: Bingley, UK, 2021; pp. 201–218. [Google Scholar]

- Moßgraber, J.; Lortal, G.; Calabrò, F.; Corsi, M. An ICT Platform to support Decision Makers with Cultural Heritage Protection against Climate Events. EGU Gen. Assem. Conf. Abstr. 2020, 20, 700395. [Google Scholar]

- Bødker, S.; Kristensen, J.F.; Nielsen, C.; Sperschneider, W. Technology for boundaries. In Proceedings of the 2003 International ACM SIGGROUP Conference on Supporting Group Work, Sandibel Island, FL, USA, 9–12 November 2003; pp. 311–320. [Google Scholar]

- Halabi, A.; Sabiescu, A.; David, S.; Vannini, S.; Nemer, D. From exploration to design: Aligning intentionality in community informatics projects. J. Community Inform. 2015, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kamppuri, M.; Bednarik, R.; Tukiainen, M. The expanding focus of HCI: Case culture. In Proceedings of the 4th Nordic Conference on Human-Computer Interaction: Changing Roles, Oslo, Norway, 14–18 October 2006; pp. 405–408. [Google Scholar]

- Leidner, D.E.; Kayworth, T. A review of culture in information systems research: Toward a theory of information technology culture conflict. MIS Q. 2006, 30, 357–399. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haus, G. Cultural heritage and ICT: State of the art and perspectives. Digit. J. Digit. Cult. 2016, 1, 9–20. [Google Scholar]

- Ch’ng, E. Experiential archaeology: Is virtual time travel possible? J. Cult. Herit. 2009, 10, 458–470. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Champion, E. Entertaining the similarities and distinctions between serious games and virtual heritage projects. Entertain. Comput. 2016, 14, 67–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chung, N.; Han, H.; Joun, Y. Tourists’ intention to visit a destination: The role of augmented reality (AR) application for a heritage site. Comput. Hum. Behav. 2015, 50, 588–599. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lucifora, C.; Schembri, M.; Poggi, F.; Grasso, G.M.; Gangemi, A. Virtual reality supports perspective taking in cultural heritage interpretation. Comput. Hum. Behav. 2023, 148, 107911. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Machidon, O.M.; Duguleana, M.; Carrozzino, M. Virtual humans in cultural heritage ICT applications: A review. J. Cult. Herit. 2018, 33, 249–260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- YiFei, L.; Othman, M.K. Investigating the behavioural intentions of museum visitors towards VR: A systematic literature review. Comput. Hum. Behav. 2024, 155, 108167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Graziano, T.; Privitera, D. Cultural heritage, tourist attractiveness and augmented reality: Insights from Italy. J. Herit. Tour. 2020, 15, 666–679. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shehade, M.; Stylianou-Lambert, T. Emerging Technologies and the Digital Transformation of Museums and Heritage Sites. In Proceedings of the First International Conference, RISE IMET 2021, Nicosia, Cyprus, 2–4 June 2021; ISBN 9783030836467. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, B.; Dane, G.Z.; De Vries, B. Increasing awareness for urban cultural heritage based on 3D narrative system. Remote Sens. Spat. Inf. Sci. 2018, 42, 215–221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koukopoulos, Z.; Koukopoulos, D.; Jung, J.J. A trustworthy multimedia participatory platform for cultural heritage management in smart city environments. Multimed. Tools Appl. 2017, 76, 25943–25981. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roose, M.; Nylén, T.; Tolvanen, H.; Vesakoski, O. User-Centred Design of Multidisciplinary Spatial Data Platforms for Human-History Research. ISPRS Int. J. Geo-Inf. 2021, 10, 467. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rivero Moreno, L.D. Sustainable city storytelling: Cultural heritage as a resource for a greener and fairer urban development. J. Cult. Herit. Manag. Sustain. Dev. 2020, 10, 399–412. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mugobi, T.; Mlozi, S. The impact of external factors on ICT usage practices at UNESCO World Heritage Sites. J. Tour. Herit. Serv. Mark. 2021, 7, 3–12. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, B.; Dane, G.Z.; de Vries, B. Preferences for a multimedia web platform to increase awareness of cultural heritage: A stated choice experiment. J. Herit. Manag. 2021, 6, 188–208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arts, H.P.T.; Groot, J.K.H.; van Haeff, S.; Luttikhuis, M.; de Wit, E. DirectView: Management Support System for the Strijp-S planning; Technische Universiteit Eindhoven, Stan Ackermans Instituut: Eindhoven, The Netherlands, 2005; ISBN 9044405608. [Google Scholar]

- Dane, G.; Borgers, A.; Tilma, F. Lifestyles, new uses, and the redevelopment of industrial heritage sites: A case study of Strijp-S, Eindhoven. In Proceedings of the 24th International Conference on Urban Planning and Regional Development in the Information Society GeoMultimedia, Karlsruhe, Germany, 2–4 April 2019; pp. 483–492. [Google Scholar]

- de Zwart, B. De heruitvinding van Strijp S. In Transformatie Strijp S. Herinnering Verbeelding Toekomst; Doevendans, C.H., Veldpaus, L., Eds.; Technische Universiteit Eindhoven: Eindhoven, The Netherlands, 2007; pp. 44–49. [Google Scholar]

- Luttikhuis, M. Inbedding Strijp S: Een Brug. Slaan Tussen Strijp S En. Haar Omgeving. 2006. Available online: https://www.tue.nl/en/department-of-the-built-environment/education/designers-programs-pdeng/post-msc-architectural-design-management-systems-adms/program/information-for-industry/publicationsprojects/final-reports-in-company-assignment-sai-adms (accessed on 27 October 2024).

- Mulrenin, A.M. DigiCULT: Unlocking the Value of Europe’s Cultural Heritage Sector. In Digital Applications for Cultural and Heritage Institutions; Routledge: Oxfordshire, UK, 2017; pp. 45–54. [Google Scholar]

- Marconcini, S. ICT as a tool to foster inclusion: Interactive maps to access cultural heritage sites. IOP Conf. Ser. Mater. Sci. Eng. 2018, 364, 012040. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, B.; Dai, L.; Liao, B. System architecture design of a multimedia platform to increase awareness of cultural heritage: A case study of sustainable cultural heritage. Sustainability 2023, 15, 2504. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, B.; Dane, G.; Arentze, T. A structural equation model to analyze the use of a new multi media platform for increasing awareness of cultural heritage. Front. Archit. Res. 2023, 12, 509–522. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karayazi, S.S.; Dane, G.; Arentze, T. Visitors’ heritage location choices in Amsterdam in times of mass tourism: A latent class analysis. J. Herit. Tour. 2024, 19, 497–518. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Socio-Demographics | Numbers in MMP Group (%) | Numbers in Google Group | p-Value of Chi-Square | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Gender | Male | 151 (50.0%) | 73 (49.3%) | 0.893 |

| Female | 151 (50.0%) | 75 (50.7%) | ||

| Age | Young people (below 34) | 73 (24.2%) | 45 (30.4%) | 0.061 |

| Middle age (34–49) | 77 (25.5%) | 46 (31.1%) | ||

| Elder (50+) | 152 (50.3%) | 57 (38.5%) | ||

| Education level | Low education | 37 (12.3%) | 18 (12.7%) | 0.087 |

| Middle education | 129 (42.7%) | 48 (32.4%) | ||

| High education | 136 (45.0%) | 82 (54.9%) | ||

| Income | Low income | 56 (18.5%) | 27 (18.2%) | 0.670 |

| Middle income | 129 (42.7%) | 69 (46.6%) | ||

| High income | 87 (28.8%) | 35 (23.6%) | ||

| Not to say | 30 (10.0%) | 17 (11.6%) | ||

| Have you visited Strijp-S before? | Yes | 71 (23.5%) | 44 (29.7%) | 0.155 |

| No | 231 (76.5%) | 104 (70.3%) | ||

| Do you live in Eindhoven now? | Yes | 13 (4.3%) | 7 (4.7%) | 0.837 |

| No | 289 (95.7%) | 141 (95.3%) | ||

| Statements | p-Value | Group | Mean |

|---|---|---|---|

| I would like to visit specific buildings at Strijp-S | 0.002 | Before | 2.960 |

| After | 3.109 | ||

| I would like to visit Strijp-S district when I have an opportunity | 0.016 | Before | 3.096 |

| After | 3.199 | ||

| I care about cultural heritage buildings or public places at Strijp-S | 0.688 | Before | 3.113 |

| After | 3.133 | ||

| I’m interested in buildings at Strijp-S | 0.010 | Before | 3.083 |

| After | 3.262 | ||

| I’m interested in public space at Strijp-S | <0.001 | Before | 2.772 |

| After | 3.149 | ||

| I’m interested in landscape at Strijp-S | <0.001 | Before | 2.914 |

| After | 3.156 | ||

| I’m interested in persons who are related to Strijp-S | <0.001 | Before | 2.589 |

| After | 2.947 | ||

| I’m interested in historical and current events of Strijp-S | <0.001 | Before | 2.861 |

| After | 3.109 | ||

| I’m interested in local lifestyle related to Strijp-S | 0.001 | Before | 2.566 |

| After | 2.821 | ||

| I would like to live in one of the cultural heritage buildings at Strijp-S | <0.001 | Before | 1.894 |

| After | 2.209 | ||

| I am interested in cultural heritage redevelopment of Strijp-S | <0.001 | Before | 2.768 |

| After | 2.990 | ||

| I would like to join discussions about the future cultural heritage redevelopment of Strijp-S | <0.001 | Before | 1.911 |

| After | 2.109 | ||

| I would like to join at least one of the events at Strijp-S | 0.022 | Before | 2.719 |

| After | 2.821 |

| Statements | p-Value | Group | Mean |

|---|---|---|---|

| The platform can help to gain tangible cultural heritage information | <0.001 | 2.345 | |

| Multi-Media Platform | 3.583 | ||

| The platform can help to gain intangible cultural heritage information | <0.001 | 2.500 | |

| Multi-Media Platform | 3.500 | ||

| The platform can help to gain interested cultural heritage information | <0.001 | 2.3445 | |

| Multi-Media Platform | 3.619 | ||

| I would like to visit specific buildings at Strijp-S | 0.096 | 2.926 | |

| Multi-Media Platform | 3.109 | ||

| I would like to visit Strijp-S district when I have an opportunity | 0.007 | 2.905 | |

| Multi-Media Platform | 3.199 | ||

| I care about cultural heritage buildings or places at Strijp-S | 0.008 | 2.939 | |

| Multi-Media Platform | 3.133 | ||

| I’m interested in buildings at Strijp-S | <0.001 | 2.635 | |

| Multi-Media Platform | 3.262 | ||

| I’m interested in public space at Strijp-S | 0.05 | 2.899 | |

| Multi-Media Platform | 3.149 | ||

| I’m interested in landscape at Strijp-S | 0.254 | 3.014 | |

| Multi-Media Platform | 3.156 | ||

| I’m interested in persons who are related to Strijp-S | 0.001 | 2.947 | |

| Multi-Media Platform | 3.358 | ||

| I’m interested in historical and current events of Strijp-S | 0.698 | 3.109 | |

| Multi-Media Platform | 3.162 | ||

| I’m interested in local lifestyle related to Strijp-S | <0.001 | 2.821 | |

| Multi-Media Platform | 3.399 | ||

| I would like to live in one of the cultural heritage buildings at Strijp-S | <0.001 | 2.209 | |

| Multi-Media Platform | 3.777 | ||

| I am interested in cultural heritage redevelopment of Strijp-S | 0.474 | 2.990 | |

| Multi-Media Platform | 3.068 | ||

| I would like to join discussions about the future cultural heritage redevelopment of Strijp-S | <0.001 | 2.109 | |

| Multi-Media Platform | 3.926 | ||

| I would like to join at least one of the events at Strijp-S | 0.05 | 2.821 | |

| Multi-Media Platform | 3.061 | ||

| The Platform has increased my awareness of cultural heritage of Strijp-S | <0.001 | 2.250 | |

| Multi-Media Platform | 3.672 |

| Questions | Group | Mean Score | p-Value of t-Test |

|---|---|---|---|

| The number of architectural buildings/public-space/heritage-landscape at Strijp-S known to respondents | Before | 1.864 | <0.001 |

| After | 2.905 | ||

| The number of historical persons who had a significant influence related to Strijp-S known to respondents | Before | 1.291 | <0.001 |

| After | 1.371 | ||

| The number of events that are significant for the history of Strijp-S known to respondents | Before | 1.581 | <0.001 |

| After | 2.432 |

| Questions | Group | Mean Score | p-Value of t-Test |

|---|---|---|---|

| The number of architectural buildings/public-space/heritage-landscape at Strijp-S known to respondents | Before | 1.600 | <0.001 |

| After | 2.338 | ||

| The number of historical persons who had a significant influence related to Strijp-S known to respondents | Before | 1.304 | <0.001 |

| After | 1.517 | ||

| The number of events that are significant for the history of Strijp-S known to respondents | Before | 1.937 | <0.001 |

| After | 2.268 |

| Questions | Group | Average Difference in Numbers | Independent t-Test |

|---|---|---|---|

| The number of architectural buildings/public-space/heritage-landscape at Strijp-S known to respondents | Multi-Media Platform | 1.041 | 0.018 |

| 0.738 | |||

| The number of historical persons who had a significant influence related to Strijp-S known to respondents | Multi-Media Platform | 0.08 | <0.001 |

| 0.213 | |||

| The number of events that are significant for the history of Strijp-S known to respondents | Multi-Media Platform | 0.851 | <0.001 |

| Media type | Media Questions | ||

| Which media has helped you the most to find information about the public space at Strijp-S | Which media has helped you the most to find information about the buildings at Strijp-S | Which media has helped you the most to find information about the landscape at Strijp-S | |

| Map | 3 | 1 | 3 |

| Text | 1 | 2 | 2 |

| Photo | 2 | 2 | 1 |

| 3D model | 5 | 4 | 5 |

| Video | 4 | 5 | 4 |

| Panorama VR | 6 | 6 | 6 |

| Media type | Media Questions | ||

| Which media has helped you the most to find information about significant events at Strijp-S | Which media has helped you the most to find information about significant persons at Strijp-S | Which media has helped you the most to find information about local lifestyle at Strijp-S | |

| Text | 1 | 1 | 1 |

| Photo | 2 | 2 | 2 |

| Video | 3 | 3 | 3 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Wang, B.; Dane, G.; de Vries, B.; Arentze, T. Design and Test of a Multi-Media Web Platform Prototype Based on People’s Preferences to Increase Cultural Heritage Awareness. Sustainability 2024, 16, 10065. https://doi.org/10.3390/su162210065

Wang B, Dane G, de Vries B, Arentze T. Design and Test of a Multi-Media Web Platform Prototype Based on People’s Preferences to Increase Cultural Heritage Awareness. Sustainability. 2024; 16(22):10065. https://doi.org/10.3390/su162210065

Chicago/Turabian StyleWang, Benshuo, Gamze Dane, Bauke de Vries, and Theo Arentze. 2024. "Design and Test of a Multi-Media Web Platform Prototype Based on People’s Preferences to Increase Cultural Heritage Awareness" Sustainability 16, no. 22: 10065. https://doi.org/10.3390/su162210065

APA StyleWang, B., Dane, G., de Vries, B., & Arentze, T. (2024). Design and Test of a Multi-Media Web Platform Prototype Based on People’s Preferences to Increase Cultural Heritage Awareness. Sustainability, 16(22), 10065. https://doi.org/10.3390/su162210065