Abstract

Chiang Mai Old City, a cultural heritage site and major tourist destination in Thailand, has significant cultural capital but lacks a well-designed urban lighting system, limiting its nighttime development potential. This issue arises from the absence of an urban lighting master plan, a crucial tool for guiding the city’s growth. The challenge lies in reconciling the diverse perspectives of stakeholders to create a comprehensive lighting master plan that meets shared goals. This research proposes a system dynamics approach to analyze stakeholder complexity. A qualitative, multi-stage method was employed, through in-depth interviews and focus groups with 60 stakeholders from three groups: government, professionals, and end users, to prioritize critical factors. Causal Loop Diagrams (CLDs) were used to illustrate the interrelations among those factors, leading to alternative scenarios for the lighting master plan’s development. The findings demonstrate that safety and security is the top priority, followed by cultural and economic factors. Eleven reinforcing loops and two balancing loops are proposed through CLD visualization. This framework highlights the importance of a participatory process, advocating for a systematic and holistic approach where all stakeholders with diverse perspective collaborate side-by-side in the development of the urban lighting master plan for Chiang Mai Old City.

1. Introduction

Nighttime development has gained global attention as a key strategy to improve quality of life, revitalize the evening economy [1,2,3,4], enhance a city’s image, and create competitiveness in night tourism [5,6,7,8,9,10]. Urban lighting, as a core infrastructure element, plays a crucial role in shaping the nighttime environment of cities. It addresses multiple levels of human needs such as providing safety and security that facilitate people to commute around the city [11,12,13,14,15,16,17,18,19], fosters social interaction [13,15,17,20,21], enhances cultural experiences, and promotes a city’s unique identity [13,15,17,22,23]. These benefits stimulate economic activity by attracting tourists, creating jobs, and driving consumption in vibrant nighttime destinations [5,6,7,13,17,23,24].

As nighttime urban environments become increasingly complex, there has been a shift in urban lighting design from focusing solely on technical performance and aesthetics to adopting a more holistic paradigm [8,17,25]. This new approach incorporates a more complex broader range of considerations, including cultural, social, economic, well-being, and environmental factors [17,25,26]. Consequently, the need for a comprehensive urban lighting master plan has become essential for revitalization of a city.

A comparative study of 12 member cities of the Lighting Urban Community International (LUCI) Association highlights that successful urban lighting master plans share the same key significant element, which is the use of a participatory process involving diverse stakeholders. This approach ensures more inclusive and informed outcomes by incorporating the knowledge, perspectives, and concerns of affected groups throughout the design, planning, and implementation stages [27]. However, engaging multiple stakeholders is challenging, as each tends to view the system from their own perspective, often overlooking unintended consequences or broader solutions [28]. To overcome these challenges, it is important to provide tools that enable stakeholders to understand the system holistically and recognize interdependencies. Effective methodologies and strong collaboration are crucial for achieving this comprehensive view [26].

In urban research, stakeholder engagement is essential for tackling complex challenges and developing sustainable solutions, especially for infrastructure projects which have a high diversity of stakeholders with conflict interest [29,30,31]. The participatory process plays a vital role in integrating cross-disciplinary insights by fostering collaboration across diverse stakeholder groups, which in turn offers different role and stages during the entire planning process [28,32,33].

To understand the diversity of the stakeholder perspective, Causal Loop Diagrams (CLDs) have been widely used as effective tools to transform unstructured insights into a systems dynamic approach. They are particularly useful for addressing the complexity of diverse factors and the interrelations raised by multiple stakeholders [28,34,35,36,37,38]. CLDs clarify relationships between key actors and their perspectives, providing a comprehensive understanding of the dynamics within the system [39] and facilitating more effective, holistic problem-solving. However, in urban lighting design, there appears to be limited direct research on applying CLDs specifically to this field. The nighttime urban environment is complex, influenced by factors that fluctuate with changing conditions. This complexity highlights the urgent need for a holistic understanding of the entire system, making the use of CLDs essential for effectively addressing the interconnected challenges of urban lighting design.

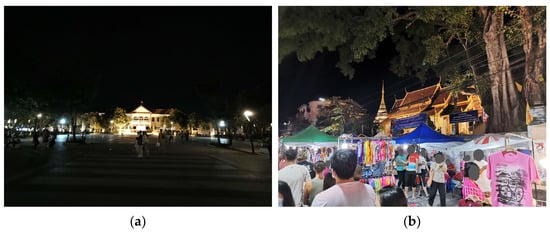

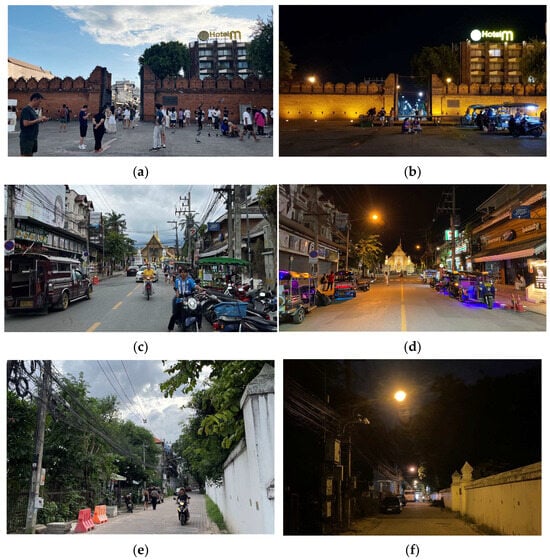

Chiang Mai Old City is an important tourism destination in northern Thailand. Its rich cultural heritage presents significant opportunities for enhancing cultural identity, economic development, and tourism [40,41,42,43]. Currently, Chiang Mai Old City holds the title of a Creative City for Crafts and Folk Art, recognized by UNESCO, and the city is pursuing a potential nomination as a UNESCO World Heritage Site [42,44]. While previous research has suggested that most visits occur during the evening and nighttime [45], nevertheless, the city’s nightscape planning has received less attention. Results from the preliminary survey reveal deficiencies in nighttime lighting infrastructure, particularly in areas such as roads, alleys, and public open spaces (see Figure 1). These deficiencies impact public perceptions of safety and obstruct the visibility of cultural elements and architectural features. As a result, this diminishes the city’s ability to foster community pride and fully leverage its nighttime potential [46].

Figure 1.

Examples of current urban lighting condition in Chiang Mai Old City: (a) Three Kings Monument Plaza, a civic space of Chiang Mai Old City, and (b) Rachadamnoen Road weekend walking street, the main axis of Chiang Mai Old City. (Images were taken by authors on 15 October 2023).

Urban lighting design is widely recognized as a powerful tool for celebrating and enriching the nighttime environment [47], creating placemaking and city characterization [48,49,50], and evoking emotional connections that strengthen the bond between people and the city [11,51]. The absence of a comprehensive urban lighting master plan represents a significant gap in Chiang Mai’s ability to fully utilize its nighttime potential. This gap presents a valuable opportunity for this study to explore and address the complex lighting issues from the perspective of stakeholders, using Chiang Mai Old City as a case study.

This study has three objectives. Firstly, it aims to identify and prioritize the critical factors for developing an urban lighting master plan for Chiang Mai Old City by using a qualitative multi-stage method to collect diverse stakeholder perspectives from in-depth interviews and focus groups. Secondly, it seeks visualize the complex interrelationships between various factors from stakeholders by using CLDs for a deeper understanding of the cause-and-effect interrelation to propose possible thematical clusters and initial scenarios as a strategic model for an urban lighting master plan towards sustainable development. Lastly, the study will discuss the broader applicability and flexibility of this approach to other cities by offering a framework for developing urban lighting master plans in cultural heritage contexts.

Overall, this research offers a holistic approach to urban lighting master planning by utilizing CLDs for systemic analysis. The study provides a comprehensive framework for addressing the complex dynamics of lighting design in cultural heritage cities like Chiang Mai Old City. Moreover, it presents a flexible solution that can be adapted to other cities, promoting sustainable urban development through inclusive stakeholder’s participatory process.

2. Literature Review

2.1. The Paradigm Shift in Urban Lighting Master Planning

In the early stage of urban lighting design, the focus was primarily on technical considerations. Urban lighting handbooks and standards have long been approached primarily from a technical perspective. Early editions of lighting handbooks and standards often focus predominantly on technical aspects such as light quantity, visual performance, and infrastructure durability. This technical approach aimed to ensure adequate illumination and performance but often overlooked aesthetic that enhances a city’s attractiveness and stakeholder engagement.

Over time, lighting practice has shifted from a focus on engineering illumination to more emphasis on lighting design, moving away from illuminance calculations towards aesthetic considerations and quality of lighting [52,53,54,55,56]. As argued by the International Commission on Illumination (CIE) [57], functional lighting, designed primarily for safety and utility, often lacks visual appeal. The focus evolved to include expressive elements such as beautification, harmony, and identity creation. This transition began in the early 1990s when French lighting designers, notably from the Association des Concepteurs Lumière et Éclairagistes (ACE), began integrating cultural and aesthetic considerations into their designs [26].

Strategic urban lighting master plans emerged, aimed at enhancing the urban nightscape atmosphere contributing to city beautification [52,57]. These master plans, which were widely adopted across the UK, Europe, North America, and Asia, not only addressed future lighting needs but also served as marketing tools to attract funding for their implementation. For example, the Edinburgh Lighting Vision Plan aimed to boost the Scottish capital’s tourism economy beyond the busy summer season by focusing on key visual elements such as gateways, nodes, skylines, topography features, vistas, and historical zones, all of which helped create a coherent nighttime identity for the city, create a sense of arrival, and prioritize visual performance [52].

Nevertheless, criticisms arose regarding the narrow focus of earlier plans, which either emphasized functional lighting or highlighted architectural landmarks without considering the broader context [58]. This critique highlighted the need for a more holistic approach to urban lighting master planning, one that integrates nocturnal landscapes, pedestrian-friendly environments, and environmental considerations such as energy consumption and ecological impact [17,57,58].

The most recent shift in urban lighting design places people and social dynamics at the center. This human-centric paradigm extends beyond technical performance and aesthetic considerations, incorporating a broader interdisciplinary perspective that integrates lighting engineering with urban design and architecture to enhance human experiences [17,25]. Zielinska-Dabkowska and Bobkowska [17] highlight this shift towards prioritizing human needs over traditional factors such as infrastructure and city mobility. This shift emphasizes improving pedestrian experiences and fostering environmentally responsible, sustainable urban environments [20] as a more holistic approach to urban lighting master planning [59]. The CIE [57] supports this broader approach, advocating for comprehensive lighting master plans that harmonize all lighting elements within the urban nightscape. These plans balance visual objectives with legislative, managerial, and economic considerations while addressing energy consumption and light pollution, aiming to achieve an optimal balance between functionality and aesthetic appeal.

Recently, Peña-García et al. [60] identify a gap in recognizing how contextual factors interact with lighting to influence outdoor lighting outcomes. They propose the Basic Process of Lighting (BPL) framework, which integrates human factors by assessing the effects of public lighting on well-being and emotions. Their research indicates that social factors have a significant impact on well-being compared to physical and visual factors, highlighting the need for a deeper understanding of how lighting design affects human experiences and social dynamics.

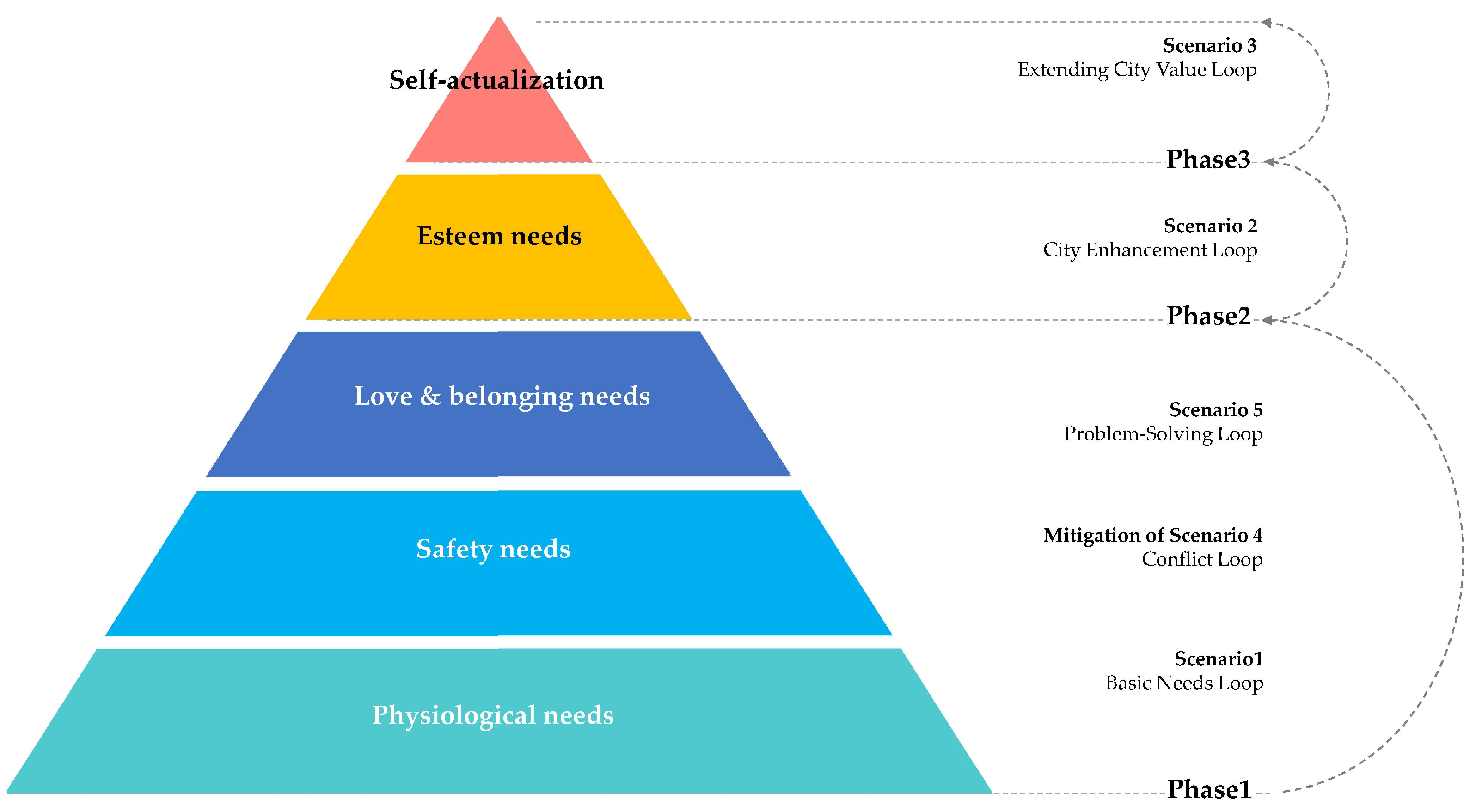

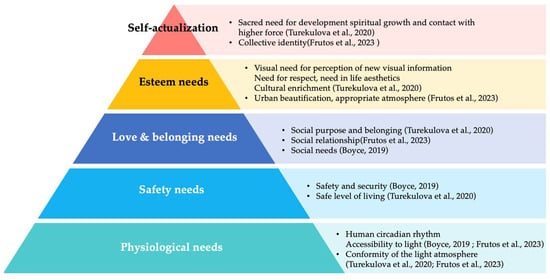

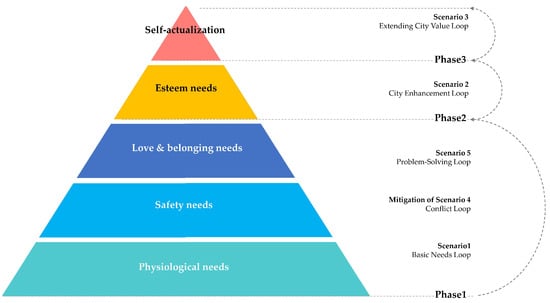

To understand the relation of human perception and expectations towards the urban lighting, the Society of Light and Lighting (SLL) [56] integrates Maslow’s hierarchy of needs [61] to evaluate how lighting contributes to various needs, from basic physiological requirements to higher-order psychological and self-fulfillment needs. Recent research has applied this framework to lighting design. For example, Boyce [13] utilized Maslow’s hierarchy to demonstrate that nighttime lighting addresses fundamental human motivations, arguing that urban lighting should not only fulfill basic needs but also evolve in alignment with the ascending levels of Maslow’s pyramid.

Frutos et al. [11] explored how lighting design fosters a sense of belonging, identifying lighting as a generator of atmosphere. Properly designed lighting can create optimal conditions for social interaction, making spaces more attractive and encouraging people to return and spend more time. Moreover, lighting can serve as a symbol, reflecting collective memories through personal, group, and cultural processes. Additionally, Turekulova et al. [12] assessed how lighting correlates with human needs and emotions using a morphological analysis with a cross-consistency assessment method. Their evaluation criteria, based on Maslow’s pyramid, considered the effects of light on different levels of needs. This approach highlights the importance of integrating lighting design with a comprehensive understanding of human needs, enhancing both functionality and emotional impact in urban spaces.

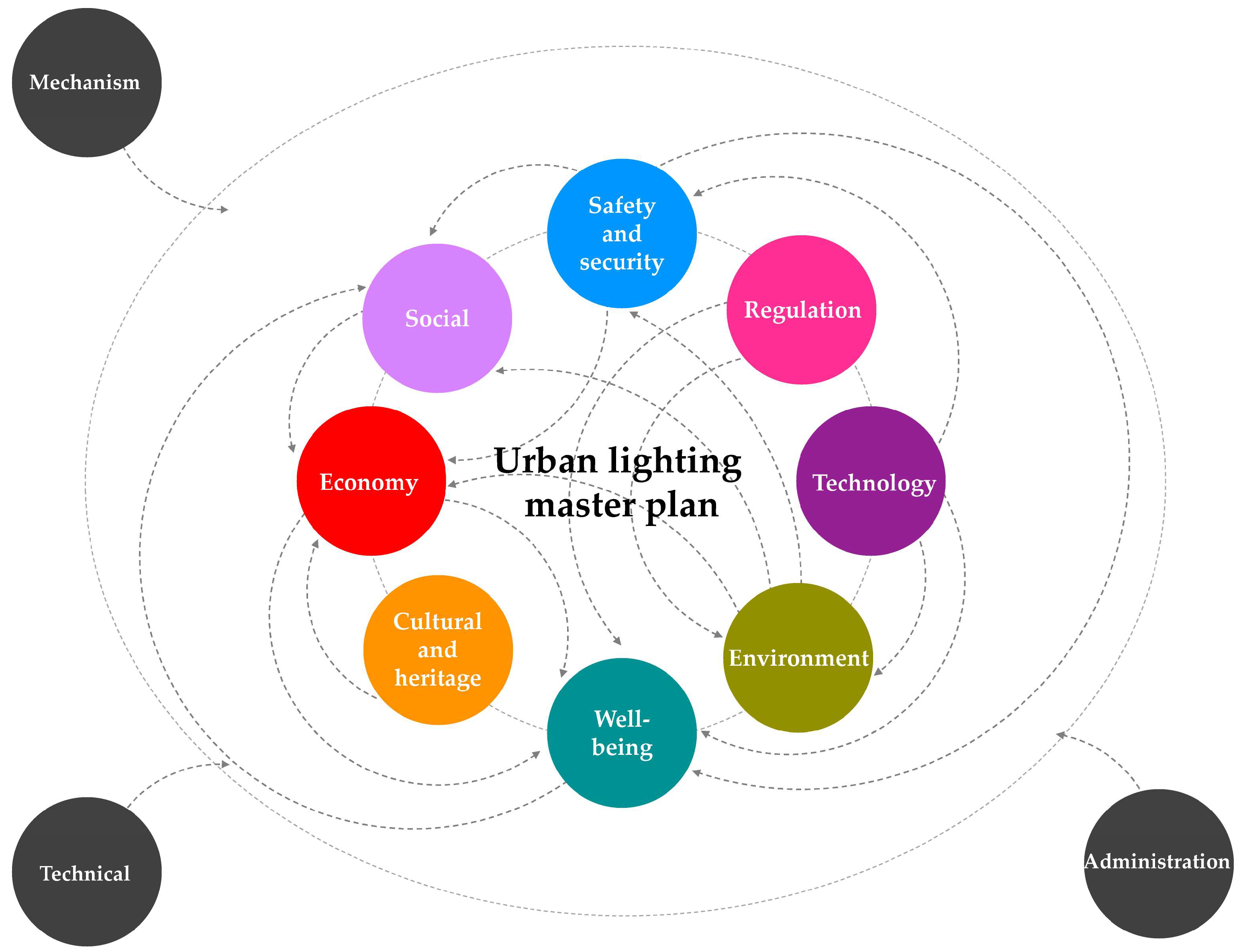

Despite an increasing use of the Maslow’s hierarchy framework in lighting design, its application to large scale urban lighting master planning remains underexplored. Figure 2 illustrates the connection between Maslow’s hierarchy framework and urban lighting design, which could provide a comprehensive framework for urban lighting master plans.

Figure 2.

The connection between Maslow’s hierarchy of needs framework [61] and previous studies on urban lighting design [11,12,13]. Source: Authors.

2.2. Factors in Urban Lighting Master Plan Development

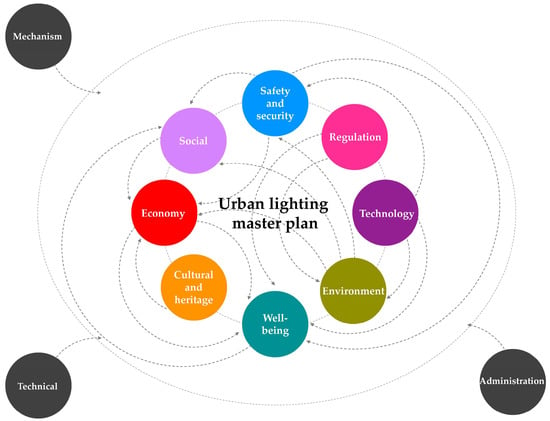

Regarding the current shift towards a human-centric paradigm in urban lighting master planning, Zielińska-Dabkowska and Bobkowska [17] identified eight key aspects of urban lighting in sustainable cities. In this research, these eight aspects serve as the base framework for analysis. A literature review is conducted to expand upon these aspects, providing a deeper understanding and detailing their scope. Table 1 provides a summary of urban elements and lighting benefits for each factor.

Table 1.

The various factors identified by different lighting researchers.

2.2.1. Safety and Security

Urban lighting’s primary function is widely recognized as ensuring safety and security for both motorists and pedestrians by enhancing visual performance [52,53,55]. Adequate lighting fosters a sense of safety and boosts confidence for individuals venturing outdoors after dark [13,16,19,76]. Previous studies [16,62] identified four critical objectives of pedestrian lighting: detecting obstacles such as uneven surfaces, facilitating visual orientation for reading street signs, enhancing facial recognition for social comfort, and ensuring overall pedestrian comfort.

The preference for lighting plays a crucial role in enhancing a sense of safety [18]. Himschoot et al. [19] suggested that higher light intensity generally enhances feelings of safety more than light color does, recommending amber lighting as a balance between safety benefits and minimizing negative impacts on wildlife, night vision, and circadian rhythms. Böhme [15] supported that well-lit areas promote feelings of security and freedom, as illuminated spaces create a sense of safety by clearly defining boundaries and reducing exposure to potential hazards. In contrast, darker, undefined areas can be perceived as dangerous, heightening the perceived risk.

This foundational aspect of urban lighting extends to various additional benefits for the city. Boyce [13] also emphasized that effective urban lighting not only improves safety but also offers social and economic benefits.

2.2.2. Social

Lighting is not only a functional tool but also plays a vital role in shaping social spaces, enhancing urban livability, and fostering social connections among diverse communities. Entwistle and Slater [20] emphasize how light influences social diversity and interactions by shaping spaces through both technical and aesthetic design, highlighting its transformative role in urban environments. Böhme [15] expands on this, suggesting that space is not merely defined by physical structures such as walls, balconies, or stone cornices, but by the interplay of light, alignment, and perspective. Illumination significantly affects how individuals perceive and experience space, with light actively creating environments that shape our social interactions. Bille [21] supports this by framing light as an ambient quality that surrounds and defines space, rather than merely illuminating it. Boyce [13] emphasizes the social value of lighting, noting how it extends daily activities by enabling social interactions after dark.

2.2.3. Economy

Urban lighting plays a pivotal role in driving the nighttime economy by extending business hours and fostering social engagement in public spaces, particularly in tourism, retail, and hospitality sectors, contributing to a city’s overall liveliness and economic resilience. Boyce [13] emphasizes that effective lighting not only enables businesses to operate around the clock but also encourages people to gather and participate in social activities after dark. This aligns with Schulte-Römer et al. [24], who highlight how lighting creates vibrant and dynamic environments that draw in shoppers, diners, tourists, and nightlife enthusiasts, thereby boosting economic activity. Giordano [23] further stresses the strategic use of urban lighting in revitalizing nighttime economies and promoting tourism.

The second scope relates to temporary or event-based lighting, such as in the context of light festivals. Böhme [15] highlights how illumination can enhance features such as public art, tourist attractions, and light festivals, adding a crucial dimension to space and creating an atmosphere of spectacle and engagement. This approach aligns with Zielinska-Dabkowska’s [63] previous study that lighting festivals, such as the Fête des Lumières in Lyon or the Biennale of Lighting Culture, Frankfurt, serve not only as cultural events but also as economic tools to attract tourists, using advanced lighting technologies like 3D mapping and projection.

2.2.4. Cultural and Heritage

In the context of cultural and heritage aspects of urban lighting, Böhme [15] emphasizes that the phenomenology of light significantly influences how spaces are perceived, contributing to emotional experiences tied to urban environments. Edensor [64] suggests that defamiliarization through illumination can transform familiar places, making them seem both new and profound. This approach enhances the sense of place by offering diverse sensory and symbolic experiences that connect people with historical narratives and cultural contexts.

Zielinska-Dabkowska and Xavia [67] highlight the importance of nighttime illumination in enhancing the visual and cultural identity of urban settings, particularly in cities dependent on heritage tourism. Effective lighting not only showcases architectural and historical elements but also enriches the spatial experience for residents and visitors. They advocate for the use of appropriate lighting technologies and professional expertise to ensure that the unique character of a place is highlighted harmoniously and sensitively. This includes maintaining and preserving monuments, archaeological sites, and historic urban settings to retain their cultural significance during the night.

Zielinska-Dabkowska and Bobkowska [17] further argue that decorative urban lighting should enhance the appreciation of built heritage by sensitively illuminating facades, monuments, and other structures, thus giving them distinct identities after dark. Giordano [23] points out the growing emphasis on sustainable and innovative lighting designs in cultural-led regeneration strategies. This approach aims to foster a renewed commitment to adopting technologies that support the cultural and economic vitality of cities. Overall, the integration of lighting into cultural heritage strategies requires a balanced consideration of aesthetic, emotional, and functional aspects to create vibrant and meaningful authenticity.

Urban lighting plays a vital role in shaping the identity and atmosphere of a place. Edensor [64,65] emphasized that the interplay between light and darkness not only defines how we perceive space but also shapes how we experience it, as lighting reveals various dimensions of space. Color and illumination can alter perceptions, creating distinct sensory experiences.

Böhme [15] described urban atmospheres as being “staged” by designers and advertisers, much like scenes in a theater. This staging is reflected in how cities use lighting to balance attractions, control their image, and enhance beauty and entertainment. Meanwhile private property lighting, such as from facades and advertisements, plays a significant role in this balance, influencing the city’s overall aesthetic [13]. Media displays and glass facades further contribute to the visual appeal of cities at night, helping to highlight architecture and skylines in ways that reinforce urban identity and branding strategies. This strategic use of lighting not only beautifies urban spaces but also contributes to the process of “place-making” [9,24], where lighting helps define a city’s character and its appeal to both residents and visitors.

2.2.5. Well-Being

The relationship between light and human health, particularly in relation to the circadian system, has led to a growing concern in lighting design, where the focus is shifting beyond vision to include human well-being [68]. Entwistle and Slater [20] highlight the impact of artificial lighting on circadian rhythms and overall health. Artificial illumination can disrupt sleep and contribute to health problems such as unwanted light trespass and spill light from outdoor sources infiltrating homes which can lead to insomnia and hormonal imbalances [17,67,69,72]. As cities transition from sodium lamps to LEDs, the extent of our exposure to artificial light is increasing. This shift emphasizes the need for new strategies and technologies to address these issues. Raising public awareness about lighting problems is crucial, and both researchers and lighting professionals must communicate these challenges effectively.

Veitch [68] emphasizes that effective lighting should address not just visual performance but also spatial aesthetics, safety, and overall human well-being. This perspective marks a significant shift from earlier lighting design principles, which primarily prioritized visual performance. According to the IESNA [54] lighting handbook and discussions from the First CIE Symposium on Lighting Quality in 1998 [77], modern lighting design now encompasses three key dimensions: visual performance, spatial appearance, and individual well-being.

Lighting plays a crucial role in well-being; for example, excessive glare and flicker can disrupt eye movements, reduce visual comfort, and lead to headaches and eyestrain. Conversely, insufficient lighting can also negatively impact health, potentially contributing to mood disorders. This evolving understanding pointed out the importance of designing lighting solutions that cater to the diverse needs of individuals and promote both functionality and health [68].

2.2.6. Environment

In recent decades, lighting professionals have significantly altered nighttime environments by illuminating streets, buildings, landscape, advertising lighting, and skyglow continuously [72]. This shift has prioritized visual appeal for visitors over the preservation of natural nightscapes. Consequently, this had led to unnatural brightness and color changes, which are now recognized as environmental pollutants which affect terrestrial and aquatic habitats; for example, this affects places like New Zealand where preserving natural nocturnal landscapes is crucial due to the unique native flora and fauna [67,71].

Schulte-Römer et al. [24] highlight the growing awareness of lighting as an environmental issue affecting both humans and animals. The negative impacts of ALAN, such as reduced visibility of starry skies, are often subtle and challenging to prove. The shift to energy-efficient LED lighting, particularly those emitting cold-white light with higher blue wavelengths, exacerbates these issues. Zielinska-Dabkowska and Xavia [70] also proposed effective strategies, including using fully shielded fixtures, selecting appropriate light sources with safer color temperatures, and implementing controls such as curfews and automatic sensors. These measures can enhance urban safety, improve environmental quality, and protect natural areas. Moreover, the built environment can gain from emphasizing nocturnal placemaking by intentionally leaving some areas unlit as dark sanctuaries for wildlife.

2.2.7. Technology

The rapid evolution of lighting technologies has led to increased unnatural brightness and varied light colors across urban landscapes [71]. This proliferation of artificial light has significant implications for both the environment and public health. Many cities are adopting new technologies in their lighting strategies and master plans to reduce costs and emissions while fostering the development of “smarter” cities [73]. Technological advancements in lighting have dramatically expanded the range of options and effects available. As noted by Entwistle and Slater [20], innovations such as LEDs, advanced control systems, and big data applications have enhanced human-centered lighting design. Böhme [15] highlights that modern light-generating and control technologies offer a diverse array of lighting possibilities and effects.

It is apparent that urban lighting should prioritize energy efficiency by using energy-saving light sources, luminaires with optimized optical design, appropriate light spectra, and smart control systems. Pérez Vega et al. [71] emphasize the collaboration between researchers and industry professionals, including those in remote sensing and lighting technology, is crucial for developing and implementing effective lighting control measures. These collaborations often occur through new platforms such as conferences and technical committees, which facilitate the exchange of knowledge and the advancement of lighting technologies.

It should also support circular economy principles by reusing and recycling lighting equipment. Additionally, incorporating renewable energy sources, such as solar power, is vital for urban illumination. Furthermore, Zielinska-Dabkowska et al. [74] note that the rise of digital tools, like online petitions, has sparked a new wave of citizen action aimed at reducing the impacts of light pollution. Results, in terms of energy efficiency and lighting quality, show that approaches could be feasible and environmentally friendly at the same time [75].

2.2.8. Regulation

Effective regulation of urban lighting is becoming increasingly important as it intersects with a range of environmental, health, and social concerns. Pérez Vega et al. [71] highlight the critical role of collaborative frameworks involving key stakeholders such as urban planners, landscape designers, policymakers, and environmental experts in creating and enforcing comprehensive urban lighting regulations. These collaborative efforts help set sustainable short- and long-term goals for lighting master plans, ensuring that lighting strategies are not only functional but also environmentally and socially responsible.

Current policies and regulatory frameworks should be reassessed to support prototyping, innovation, and human-centered design. Lighting design considerations must be integrated early in project planning to ensure alignment with broader city development goals. As it becomes more complex, the need for sustainable, inclusive, and contextually sensitive development grows [25].

Zielinska-Dabkowska [69] points out that healthy lighting design is becoming an ethical concern, with legal actions, such as those in Monterey, California, challenging inappropriate LED lighting practices. Consequently, Zielinska-Dabkowska and Bobkowska [17] emphasize the need for urban lighting to be regulated through both soft and hard laws, with ongoing monitoring to mitigate artificial light pollution and its adverse effects.

In conclusion, the eight factors are commonly mentioned by lighting researchers as key elements for developing urban lighting master plan. The literature review reveals the interrelated nature of these factors, demonstrating the complex cause-and-effect relationships that influence urban lighting design. Each factor affects the others, reinforcing the need for a holistic approach to developing an effective urban lighting master plan. Understanding these dynamics is crucial for creating comprehensive and impactful urban lighting strategies that address functional, aesthetic, and societal needs. However, prioritizing these factors requires active stakeholder engagement throughout the design and planning process. Both CIE [57] and ILE [52] emphasize the importance of balancing lighting requirements for various user groups, which is crucial during the development of urban lighting master planning.

2.3. Stakeholders in Urban Lighting Master Planning

Stakeholders refer to individuals, groups, or organizations that have an interest in, or are affected by, the decisions, actions, or outcomes of a project. Effective management of stakeholders is critical to a project’s success, as inadequate strategies, plans, methods, and processes for stakeholder engagement can result in project failure [29].

In the urban design and planning process, the analysis of stakeholders’ being used as a research tool in the development of the urban decision-making process [31], it is crucial to involve stakeholders to ensure that their needs and preferences are considered [29,30,78]. Various stakeholder groups each responsible for different roles and stages throughout the planning process [28,32,33] have distinct short-term and long-term expectations, with different beneficiaries receiving value at each stage [31]. However, a significant challenge is that each stakeholder views the system from their own unique perspective. Stakeholders may overlook unintended consequences outside their limited view of the system, and they may only consider solutions within these perceived boundaries [28]. This occurs because decisions are often shaped by narrow viewpoints.

In an urban lighting master plan, the dynamics of urban life after dark must be tackled within a broader social, economic, and environmental framework. Lighting must be integrated as a core component of urban planning policy rather than treated as a separate initiative or strategy. This integration should recognize the significant impact lighting has on the nighttime experience and the interconnectedness of lighting with urban design, human experience, and other practices [8,25]. As lighting becomes more complex, the need for sustainable, inclusive, and contextually sensitive development grows. Stakeholders, defined broadly as individuals or groups with an interest or stake in the outcome of a project, are essential to the urban design process and bring diverse perspectives that contribute to more balanced and effective planning outcomes [25,57].

The role of stakeholders in urban nightscape has gained increasing recognition in recent years since the rapid pace of urbanization [8,25]. A successful urban lighting master plan is impossible without effective stakeholder collaboration and a shared vision to create a vibrant urban space for its users [74]. Collaboration is essential for generating innovative and suitable lighting solutions for urban areas after dark. Planning a cohesive urban nightscape is challenging due to the involvement of multiple actors with varying levels of expertise, cultural influences, and objectives, ranging from government departments to individual property owners [57].

According to CIE [57], the development of urban lighting requires the collaboration of multiple stakeholders who are interested in improving and implementing lighting strategies. These stakeholders may differ depending on the region, but the core principle is to involve and gain the support of any organization, group, or individual that can influence or contribute to the lighting development process. It is essential to anticipate and address potential objections by ensuring the inclusion and consideration of all relevant stakeholders’ perspectives, which CIE divided into the consultation group.

The LUCI Association stresses the importance of fostering cooperation between the public and private sectors, ensuring that all stakeholders, including light producers and citizens, understand the significance of the nightscape’s quality and identity, as well as their shared responsibility in shaping it [27]. This awareness could promote the development of a genuine “local culture of light”. Similarly, ARUP [25] emphasized the importance of collaboration across disciplines, stakeholder groups, and management systems. Lighting designers should take a more proactive role in creating socially sustainable environments by encouraging stakeholder collaboration, leveraging shared knowledge, and building interdependencies. Meanwhile, a strategy for managing light ownership should harmonize both private and public lighting sources. Additionally, citizens and stakeholders should be involved in the design and decision-making processes to better understand public and business needs.

In the design and planning process, another significant group of stakeholders, the professional group, has been identified. This consists of the designer and technical team, who possess a unique combination of lighting skills and/or project knowledge that enhances the possibility of delivering successful solutions on different levels of responsibility for a public realm in the city. Previous research also pointed out the rising role of designer, stating that it is crucial to recognize the urban designer’s position within the power hierarchy of stakeholders who are invested in the implementation of design and urban development, and to understand whose interests the design is intended to serve [79,80]. Rather than imposing solutions, designers are increasingly working alongside communities to create new modes of participation, helping to harness and extend local resources through collaborative initiatives.

Various literature sources provide insights into how these stakeholders are categorized, emphasizing the importance of their engagement at every stage. Table 2 outlines the key stakeholders identified in several important studies on urban lighting master planning.

Table 2.

Identification of key stakeholders from previous studies on urban lighting master planning.

Table 2 illustrates that while each source of literature focuses on stakeholder engagement from different angles, a consistent pattern emerges across the studies. Stakeholders can be broadly categorized into three main groups: the government sector, professional sector, and end users. The government sector includes national and local governments, and municipal departments, which play a regulatory and policy-driven role in urban lighting development. The professional sector comprises urban planners, architects, lighting designers, engineers, and other technical experts responsible for designing, implementing, and maintaining lighting systems. Finally, the end users group encompasses residents, businesses, tourists, NGOs, and citizens who directly interact with and experience the city’s nighttime environment.

Together, these groups encapsulate the full range of perspectives required to develop a well-rounded urban lighting master plan. Their combined input ensures that the plan addresses regulatory requirements, technical feasibility, and public satisfaction, making them representative of the city’s diverse stakeholder landscape.

Each stakeholder plays a different role and holds varying responsibilities in the collaborative planning process. Stakeholder importance can vary across different stages of the planning process, from design and planning to implementation, monitoring, evaluation, and ongoing maintenance. Although the goal is to involve a broad range of stakeholders throughout all phases, this evaluation helps to understand participants’ varying motivations, levels of willingness to engage, power dynamics, influence, and interests at each stage.

2.4. Participation in Urban Master Planning

Traditionally, urban planning and design followed a top-down approach, where planners, viewed as “the experts”, developed proposals which were then presented to decision-makers. These decision-makers held the authority to approve or reject the proposed urban plan [81,82], which led to the top view implementation that was disconnected from public participation.

Nowadays, this sits in direct contrast to participatory planning, which emphasizes the involvement of concerned stakeholders as a bottom-up approach which has gained increasing popularity as it encourages the involvement of a larger number of stakeholders, allowing for collective decision-making from joint participation [81,82,83]. However, it also presents challenges, as diverse stakeholders often bring specific concerns and interests, which can lead to conflicts. These conflicts may, in turn, cause delays in the planning and implementation process.

2.4.1. Urban Design and Planning Participation

Arnstein’s Ladder of Citizen Participation [84] is a foundational framework in the study of public involvement in decision-making processes. It offers a critical perspective on the varying degrees of citizen engagement and highlights how different levels of participation impact the effectiveness and equity of decision-making. However, its simplistic and linear structure as well as overemphasis of power dynamics have led to criticisms of its limitations and inadequacies for fully grasping the complexities of participation, both conceptually and in practical terms [85,86].

Since then, stakeholder participation has been developed in various theories and frameworks across disciplines, especially in urban design and planning. For example, Friedmann proposed Transactive Planning, which focuses on the interactive process where knowledge is not just transferred from experts to the public but co-created through ongoing engagement. Habermas’ Theory of Communicative Action [87] underpins many participatory approaches by emphasizing the role of communication and deliberation in democratic processes wherein stakeholders should engage in discourse free from coercion, leading to the best argument prevailing rather than the most powerful voice.

Freeman’s stakeholder theory [88] emphasizes the need for organizations to consider the diverse interests of all stakeholders and recognizes the interconnectedness of their actions and the broader social and environmental systems in which they operate. Supported by Wenger’s Communities of Practice [89], it emphasizes stakeholder participation as a process of collective learning with a shared interest in a particular domain that comes together to exchange knowledge, develop new ideas, and build shared practices.

In addition, Innes and Booher’s Collaborative Rationality [90] raises an alternative to traditional rational planning models, emphasizing the importance of deliberative processes where stakeholders engage in open dialogue, negotiate differences, and co-create solutions. This suggests that effective planning in complex environments requires the collaboration of multiple stakeholders with diverse perspectives and collective wisdom that leads to more robust and acceptable outcomes.

2.4.2. Participation in Urban Lighting Design

In urban design and planning, there has been a clear shift from traditional linear, hierarchical approaches to more co-creative and holistic processes that emphasize communication and deliberation. Similarly, in urban lighting, Zielinska-Dabkowska and Bobkowska [17] introduced a new design approach called “side-to-side”, which promotes multidisciplinary and interdisciplinary collaboration to enhance communication among stakeholders. The traditional linear, top-down approach to urban lighting typically involves creating a brief, which is then developed into a document and executed without ongoing communication or checks throughout the process. Moreover, end users are often only involved in the later stages of design, limiting their ability to provide input or influence the project. This approach lacks tools for capturing and communicating user feedback and social satisfaction.

To address these limitations, the Iterative Urban Lighting Design Process, which focuses on collaboration among a wide range of stakeholders who work together towards shared goals and interests, has been proposed. This iterative process gives all participants an equal role, fostering open communication, collective decision-making, and the development of appropriate solutions. The iterative design method involves multiple rounds of analysis and feedback, with each iteration aimed at refining decisions and improving outcomes. This approach breaks down complex urban lighting challenges into manageable parts, allowing for incremental design, development, and testing until a fully functional and effective lighting solution is achieved and ready for implementation.

However, the recent body of research on participatory processes in urban lighting design remains relatively limited. As public urban lighting is a transdisciplinary field, the complexities of participatory and interactive lighting require expertise and knowledge background [91]. Moreover, the success of urban lighting research must be conducted in real-world settings, allowing for practical application. This approach is critical for developing lighting solutions that are not only technically proficient but also socially inclusive and responsive to the needs of different stakeholders, as it refers to the shifting of the urban lighting paradigm to a more holistic approach [17].

Due to the challenges of complexity on the participatory process with interdisciplinary factors related to urban lighting master planning, it is crucial to employ appropriate tools which can unravel the complexities. Traditional representations like master plans or rendered visualizations can no longer adequately be systematically assessed to ensure they encompass all levels of engagement to see the holistic visualization. Therefore, designers and researchers must leverage new opportunities to capture the dynamic nature, growth, and ongoing transformation of cities by gathering information and incorporating it into iterative urban design processes [92].

2.5. Visualisation Tool for Urban Complexity

With the complexity and uncertainty of the urban context, it is necessary to unwind the unstructured problem before proposing the design solution. Sterman [93] suggests that to effectively address an issue, it is vital to understand the entire system. Any intervention without this comprehensive understanding is likely to create additional problems.

Recently, there have been many research methods and tools used to tackle the complexity and uncertainty of urban design and planning with a systematic approach, especially the research on the diversity of stakeholders’ perspective. For example, the structural analysis–MICMAC method was created to structure decision-making in a hierarchical manner [94] while the science–design loop was created as Iterative and Participative Action Loops [95]. Stakeholder Mapping to identify relevant stakeholders seems to be crucial to enable higher planning efficiency, reducing bottlenecks and the time needed for planning, designing, and implementing projects [33]. The Analytic Hierarchy Process (AHP) developed a model by using stakeholder participation [96]. Problem structuring methods (PSMs) are used widely in urban participatory research such as intervention strategies for urban project [97,98,99] to enhance the understanding of decision problems and to foster a productive environment where individuals and processes can effectively structure key elements.

Finally, the Participatory System Dynamics (SD) Model is a conceptual framework used to understand and simulate the behavior of complex systems over time. It allows for a deeper understanding of how different elements within the system interact. This approach is particularly valuable for studying dynamic, non-linear problems that evolve over time and are influenced by multiple interacting factors. This approach supports decision-making on a strategic, system-wide scale and allows for the examination of the long-term effects of different strategies [34].

However, to understand a complex system, it is often described in terms of three key dimensions: the number of elements involved (quantity), the extent of interrelationships between these elements (connectivity), and the functional connections among the system’s elements (functionality) [93]. SD was first introduced by Jay W. Forrester in 1969, and is used to illustrate the system in the mind of the individual, which is called a mental model. This modeling approach captures people’s perceptions of real-world systems by focusing on causal relationships and feedback loops which is a system structure where outputs from a process or action are fed back into the system as inputs, influencing future behavior, particularly combined with influence diagrams like Causal Loop Diagrams (CLDs) and Cognitive Maps (CMs) [93,97,100].

Causal Loop Diagrams (CLDs) and Cognitive Maps (CMs) are popularly used as tools to visualize the mental model. However, it is important to clarify [28] that CMs are typically organized in a hierarchical structure, often represented as a means/ends graph, with goal-oriented statements positioned at the top of the hierarchy. CLDs focus on mapping the feedback structures within systems [101], as opposed to emphasizing hierarchical organization [102]. Moreover, CLDs are composed of variables linked by causal connections, each with a designated polarity that indicates the direction of influence between the variables. These diagrams highlight reinforcing and balancing feedback loops and are frequently utilized to illustrate critical feedback mechanisms that contribute to a particular issue within a decision-making process [28]. Creating CLDs involves pinpointing stakeholders and internal variables as well as establishing the causal relationships among those variables. Typically, CLDs are constructed using qualitative methods such as literature reviews, observations, and stakeholder interviews [39].

In summary, CLDs are a vital part of the System Dynamics methodology, serving as a bridge between qualitative understanding to quantitative modeling of complex systems which normally are illustrated by using thematic analysis of CLDs. Now there are many research studies using CLDs to unwind the various urban un-structured problem, as CLDs have been used widely as a visualization tool in recent urban research. For example, Tomoaia-Cotisel et al. [36] use CLDs to help policymakers identify and implement effective health system strengthening. Coletta et al. [37] use CLDs with Flood Risk Management in an Urban Regeneration Process. Pluchinotta et al. [28,38] studied both the complex urban system and the importance of stakeholders’ elicitation by using CLDs to comprehend stakeholders’ perceptions of system boundaries and problem definitions, and to analyze how these perceptions might influence decision-making by systematically comparing the causal maps of different stakeholder groups regarding a common concern. Tiller et al. [103] also use SD and CLDs to understand the stakeholder narratives into a quantitative environmental model.

In conclusion, results from the literature review suggest that urban lighting master planning is a multifaceted discipline shaped by a complex interplay of factors and diverse stakeholders with differing priorities. With the challenge in urban lighting complexity and the limitations of the participatory process in this interdisciplinary field, it results in a lack of awareness and holistic understanding of stakeholders’ diverse perspectives. This is a barrier and challenge for the urban lighting master planning process.

To address these complexities, the initial step in developing an effective urban lighting master plan involves creating a clear visualization of the system’s complexity. This requires understanding the intricate relationships and causal effects among the various multidimensional factors and stakeholders. CLDs are particularly well-suited for this purpose, providing a holistic approach to elucidate how different factors interact and influence each other. By employing CLDs, stakeholders can explore alternative scenarios and further the immediate and long-term needs of Chiang Mai Old City’s urban lighting master plan.

3. Materials and Methods

This section outlines the entire research process, which employed a multi-stage qualitative method. It begins by describing the research design, data collection process through in-depth interviews and focus groups, followed by the data analysis used to address the in-depth interviews and focus groups outcome. Finally, it details the visualization process using CLDs as a key tool in Systems Dynamics methodology. CLDs visually represent the feedback relationships among different factors within a complex system [93], helping to capture the dynamics of urban lighting systems and facilitating the exploration of alternative proposed scenarios for Chiang Mai Old City. This approach also opens the discussion on its applicability and flexibility to other cities.

3.1. Site and Setting: Chiang Mai Old City

The focus area of this study is Chiang Mai Old City, located within the Chiang Mai municipality, covering an Old City area of 5.13 sq.km. according to Chiang Mai World Heritage Site. Chiang Mai is one of the country’s major tourist destinations of northern Thailand, southeast Asia. With over 700 years of history, the city has a rich legacy of settlement and a distinct urban morphology [40]. Chiang Mai Old City reflects a unique blend of diversity and cultural dynamics, encompassing both the tangible and intangible urban heritage of the traditional Lanna Kingdom [42]. However, its long history of local traditions, combined with modern developments driven by tourism, has created a complex urban environment, both during the day and at night, shaped by the diverse activities and uses of various stakeholder groups.

Despite its cultural significance, the current nightscape of Chiang Mai Old City is insufficiently developed to maximize the potential of this cultural heritage area. For example, the lighting at Tha Phae Gate, a landmark of the Old City and an ancient city entrance, fails to adequately support many social activities. Moreover, the lack of a lighting design guideline has resulted in excessive illumination from surrounding buildings, contributing to light pollution that undermines the historic atmosphere and distracts from the landmark, as illustrated in Figure 3a,b.

Figure 3.

Example of daytime and nighttime scenes of Chiang Mai’s landmark, main street, and alleyway—(a,b) Tha Phae, landmark of Chiang Mai Old City, (c,d) Rachadamnoen Road, main axis of Chiang Mai Old City, (e,f) Phra Pok Klao 13 Alley, community pathway within the Old City. (Images were taken by authors during March–June 2024).

Similarly, Rachadamnoen Road, the main axis in Chiang Mai Old City featuring the Phra Singha Temple as a focal point, experiences challenges due to cluttered lighting vignettes caused by unregulated façade, advertising controls, and street lighting. This disarray detracts from the significant value and majestic views of these historical sites, undermining the intended ambiance along the city’s vista axis, as shown in Figure 3c,d.

Additionally, Phra Pok Klao 13 Alley, which serves as a community pathway within the Old City, is inadequately lit, resulting in a diminished sense of safety and a loss of direction and connectivity, particularly for tourists, as depicted in Figure 3e,f. This dynamic interplay of historical significance, modern challenges, and varying stakeholder needs presents unique opportunities and challenges for urban planning, especially regarding the development of nighttime lighting, which plays a critical role in addressing the city’s evolving demands and future directions.

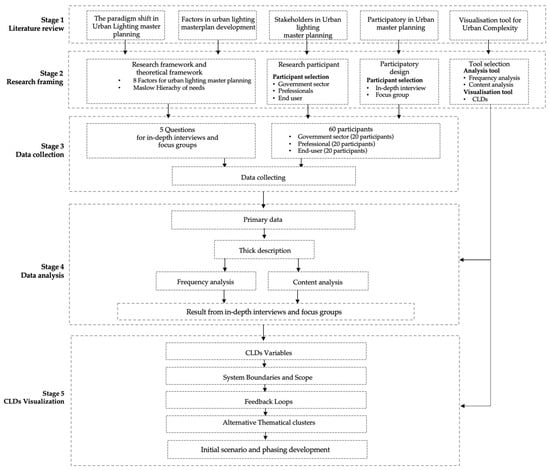

3.2. Research Design

The research design of this study was structured to three key objectives: identifying and prioritizing critical factors of urban lighting master plan for Chiang Mai Old City, understanding the complex interrelationships between those factors, and discussing the broader applicability of the approach to other cities. The research employed a multi-stage qualitative approach, as shown in Figure 4.

Figure 4.

Multi-stage qualitative research process. Source: Authors.

3.2.1. Stage 1: Literature Review

This study began by reviewing five main pieces of the literature: examining the paradigm shift in urban lighting master planning, the factors in urban lighting master plan development, and the roles of stakeholders in the process. This stage also reviewed participatory urban master planning methods and visual tools like Causal Loop Diagrams (CLDs) for managing complex urban systems.

3.2.2. Stage 2: Research Framing

Based on the literature review, the research framework was structured from the eight factors of urban lighting master planning, as outlined by Zielińska-Dabkowska and Bobkowska [17]. In this research, Questions 1–3 asked participants to evaluate the satisfaction of existing urban lighting, the future perspective and vision, and the top three priorities factors which influenced Chiang Mai Old City. Questions 4–5, which asked for the unique conditions of Chiang Mai, refer to the strength of the city, and suggestions for developing Chiang Mai Old City’ urban lighting. Lastly, Maslow’s Hierarchy of Needs [61] was used as an assessment tool to evaluate the participants’ perspective towards urban lighting, as part of an effort to adapt this framework for evaluating lighting at an urban scale.

For participant selection in this study, three key stakeholder groups adapted from stakeholders’ literature reviews were used: the government sector, professionals, and end users. The participatory research design was structured around in-depth interviews and focus groups with 60 participants, equally divided among the three groups.

3.2.3. Stage 3: Data Collection—Semi-Structured In-Depth Interviews and Focus Groups

This stage involved gathering qualitative data from a selected group of 60 participants, representing three main stakeholder categories according to the stakeholders’ literature review. Semi-structured in-depth interviews and focus groups, using five questions, were employed as the primary data collection methods. This stage was crucial for capturing the diverse insights and perspectives of various stakeholders on the challenges and opportunities surrounding urban lighting of Chiang Mai Old City.

3.2.4. Stage 4: Data Analysis—Identifying the Critical Factors and Key Stakeholders

Once the qualitative data were collected, the data analysis stage involved a frequency analysis and comprehensive content analysis. This process included coding and categorizing the participants’ responses to identify the detailed perspectives on critical factors relevant to the development of the urban lighting master plan. This enabled a more holistic and systematic understanding of how diverse perspectives contribute to the urban lighting planning process. Furthermore, the content analysis uncovered underlying issues and potential opportunities, highlighting key aspects of urban lighting that were not immediately apparent during data collection.

3.2.5. Stage 5: CLDs Visualization Modeling

The stage of the research involved translating the qualitative insights gathered from the content analysis into visualization modeling using CLDs to visualize the complex interactions between the critical factors identified in the previous stage. The CLDs facilitated a deeper understanding of how various factors interact dynamically within the urban lighting system by representing these interactions visually. This stage allowed the exploration of a proposed alternative thematical cluster, providing a flexible possibility for considering different urban lighting development paths. Lastly, an initial scenario and phasing was proposed for Chiang Mai Old City’s urban lighting master plan to tackle the city’s urban lighting system.

3.3. Data Collection: Semi-Structured, In-Depth Interviews, and Focus Groups

In this stage, qualitative data collection was carefully structured to ensure balanced stakeholders’ engagement, capturing a wide range of perspectives on urban lighting in Chiang Mai Old City. A combination of theory-based and snowball sampling methods was employed to identify 60 participants representing three main stakeholder categories, as referenced in the stakeholder literature review [17,25,26,27,57]. This approach maximized diversity and relevance in the insights gathered, making sure the perspectives covered were well-aligned with the stakeholder groups outlined in previous studies.

Semi-structured in-depth interviews and focus groups are widely recognized qualitative research methods in urban planning, especially in the multi-stakeholder participatory approach [104]. These methods are often employed in the initial stages of identifying and defining problems and shared concerns, serving as a foundation for developing CLDs modeling processes, or other modeling approaches that contribute to urban solutions across various research topics [28,33,37].

To ensure accessibility and meaningful engagement among participants from varied backgrounds, each interview and focus group began with a 5–10 min presentation that provided key context about the study, including its objectives and the specific site details of Chiang Mai Old City. This introductory presentation aimed to address potential communication barriers and ensure participants had a clear understanding of the research framework. Open-ended questions such as, “Do you have any questions before we proceed?” were used to confirm participants’ understanding, while technical jargon was avoided. Additionally, visual aids and simplified terminology were integrated to further support participants from non-technical backgrounds, enabling them to fully engage with and contribute to the discussions.

A total of 28 interviews and 8 focus group sessions were completed during June to August 2024. Each session lasted between 60 and 90 min and centered around five key questions designed to meet the research objective of developing an urban lighting master plan for the cultural heritage of Chiang Mai Old City, as shown in Table 3.

Table 3.

Questions in semi-structured in-depth interviews and focus groups.

Urban lighting design is a technical topic that can be challenging for many people to discuss in depth. To make the interviews more accessible and engaging, a conversational semi-structured format was used. This approach allowed participants to share their thoughts naturally while giving the researcher the freedom to ask follow-up questions as needed, following guidance from Osborne and Grant-Smith [104].

The interview began with an easy question, asking participants to reflect on their experiences with Chiang Mai Old City’s current nighttime lighting (Question 1). This helped establish a connection with the topic and allowed participants to ease into the conversation. Next, they were encouraged to share their ideal vision for the city’s nighttime lighting (Question 2), moving gradually into more focused discussions. To make technical aspects more understandable, a simple diagram of the eight key lighting factors (as outlined by Zielińska-Dabkowska and Bobkowska [17]) was used to help participants choose which factors they felt were most important (Question 3).

As participants became more comfortable, they were asked to think about the city’s strengths and potential in developing its lighting (Question 4). The final question invited open-ended suggestions for improving Chiang Mai’s urban lighting (Question 5). The last 2 questions were positioned at the end to ensure participants felt relaxed and ready to share any sensitive ideas, such as ways to advance the project or involve other stakeholders.

This structured flow allowed for a smooth conversation, encouraging deeper insights while keeping the discussion accessible. It also enabled the researcher to ask clarifying and follow-up questions as necessary. During the interviews, close-ended or leading questions were avoided to ensure participants could freely express their thoughts.

Similarly, the focus groups followed a conversational flow, bringing together small to medium size groups of participants from 3 to 10 participants per session, fostering dynamic and meaningful discussions. This method is particularly useful for generating a range of ideas, identifying common themes, and understanding group dynamics, making it widely used in urban research [105,106,107]. In focus groups, the interactive nature compels participants to articulate the reasoning behind their views, enabling the researcher to observe not only how individuals develop their own perspectives but also how they relate and respond to differing viewpoints [108]. However, for focus groups, moderators followed a set of guidelines to prevent any single participant from dominating the discussion. Techniques such as “round-robin” questioning were employed, where each participant was given an equal opportunity to respond to each question.

3.4. Research Participants

3.4.1. Participant Selection

To create a comprehensive and representative sample of stakeholders involved in urban lighting master planning, participants were selected based on their relevance to the study’s focus areas. The selection criteria, adapted from stakeholder literature [17,25,26,27,57], categorized participants into three distinct groups:

- Government sector: Participants must hold positions within local or national government agencies or regulatory bodies involved in urban planning, public safety, or environmental regulations.

- Professional sector: Participants should be professionals with expertise in urban lighting design, including architects, lighting designers, engineers, supplier, and consultants.

- End user: Participants must represent private sector entities such as business owners, property developers, civil society, or community organizations that are directly impacted by urban lighting.

3.4.2. Participant Recruitment

To ensure balanced representation, a two-stage recruitment process, combining theory-based and snowball sampling methods, was utilized to create a well-rounded participant sample.

Initially, theory-based sampling was used to target key individuals and organizations directly relevant to the study’s focus. This method involves selecting participants based on specific research needs to ensure the sample accurately represents the phenomenon under investigation [109]. Invitations were sent to stakeholders from diverse demographic backgrounds, including different ages, professional roles, and areas of expertise, to capture a broad spectrum of perspectives. Engaging individuals with varying levels of influence within organizations, from decision-makers to community representatives, helped avoid the overrepresentation of any single viewpoint.

The selection process began with identifying local individuals and organizations significantly involved in urban lighting, balancing representation equally among the three groups of stakeholders. Participants were approached through professional networks and recommendations, with initial contact made via email, phone, or formal invitations that outlined the study’s objectives and emphasized the importance of their input. This method ensured a comprehensive participant pool that reflected diverse insights, enhancing the overall quality of the research.

Next, snowball sampling was used to expand the participant pool. Initial participants were encouraged to refer colleagues or contacts with similar roles and responsibilities, systematically increasing the number of relevant participants. Efforts were made to achieve proportional representation across stakeholder groups, with quotas established to promote balanced participation. This approach helped capture data reflecting the interests and concerns of all relevant stakeholders.

3.5. Sample Size

The sample size of this research consists of 60 participants, categorized equally into three distinct groups based on the study’s criteria, as shown in Table 4.

Table 4.

Sample of stakeholders involved in urban lighting master planning.

3.6. Data Analysis Process

This section details the holistic and systematic approach used to analyze collected data. The initial step involved transcribing the recorded in-depth interviews and focus groups into detailed text descriptions, stored in Word document files. Content analysis was employed to identify and categorize key themes, patterns, and concepts within the data [110,111].

The initial coding process began with assigning preliminary codes to specific segments of text based on their content and context. This process involved generating codes from recurring themes and significant patterns observed in the data by using eight factors of urban lighting master planning [17] as a framework. These codes were compared with the original data to ensure accuracy and relevance. Similar codes were then consolidated into broader categories that reflected common themes and meanings. The categorized data were compiled into spreadsheet files, classifying large volumes of text into a manageable number of categories that represented similar meanings. Data from Question 1–5 were tabulated to show the total number of responses and the percentage of number of responses on each key factor and sub-factor. This organization facilitated coherent content analysis and interpretation.

The identified themes were linked to the broader objectives of developing a comprehensive urban lighting master plan referring to the theoretical framework from the literature reviews. The results were presented in a structured format using charts and tables to effectively communicate the findings. The analysis aimed to provide stakeholders with valuable insights into urban lighting master planning. Additionally, these insights were used as variables for creating further CLDs visualizations.

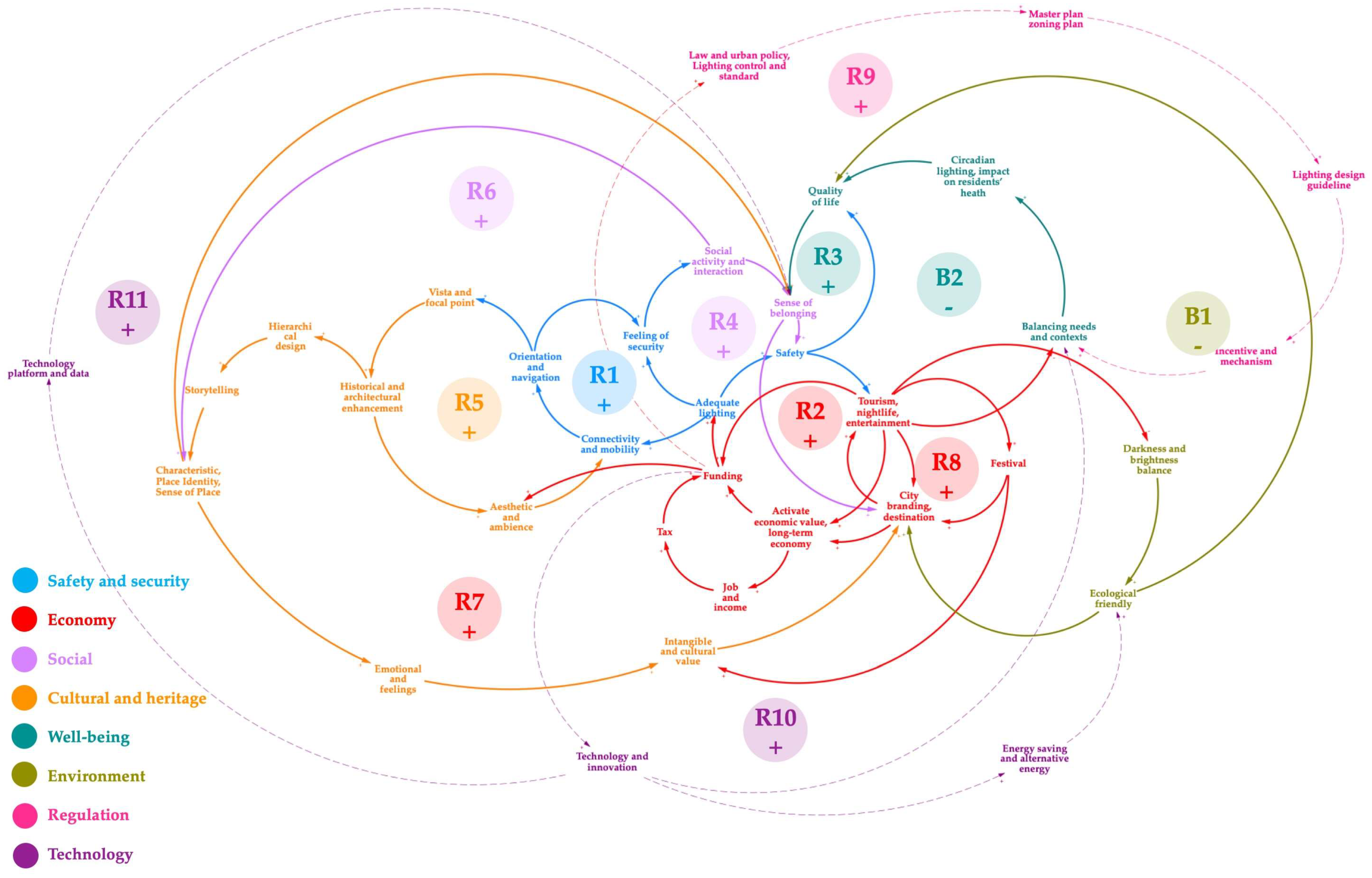

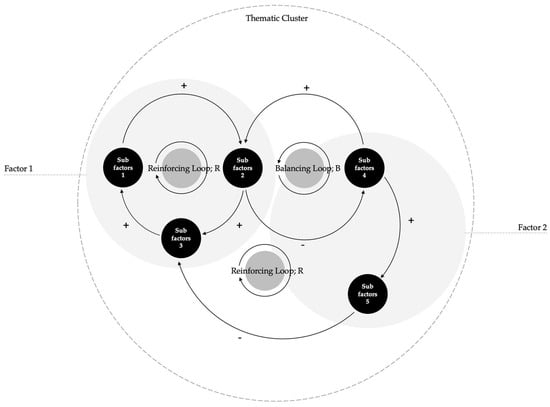

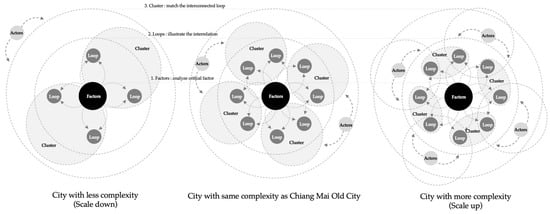

3.7. Visualization and Implication

Following the data analysis process, significant findings revealed complex relationships between existing problems, aspects and expectations, critical factors, methods and mechanisms, and key actors. These elements contribute to a complex, unstructured problem with various interrelations. To systematically represent this complexity and enhance understanding of the holistic and systematic approach, CLDs were utilized, as they provide a structured means of “Conceptualization” [112].

The process of building CLDs involved using Vensim PLE 10.2.1, a simulation software for developing dynamic feedback model. The first step in creating CLDs was to capture the intricacies of critical factors in urban lighting systems and their interactions visually. This approach highlights feedback loops and interdependencies among various factors influencing urban lighting, helping to identify the centrality of shared concerns, expectations, and aspects, and illustrating how these elements interact within the Urban Lighting Master plan. These visualizations aimed to clarify and depict the significant factors and their interrelationships, providing a comprehensive understanding of the urban lighting system and informing strategic planning. The main elements required creating CLDs which are outlined in Table 5.

Table 5.

Key elements in CLDs.

In applying CLDs to Chiang Mai Old City’s urban lighting system, the first step involved identifying key sub-factors, derived from in-depth interviews and focus groups. These sub-factors are defined as variables within the system. The next step was to map the relationships between them. Arrows were used to link the sub-factors, representing the direction of influence; a positive (+) relationship indicates that an increase in one variable causes an increase in another, while a negative (−) relationship means that an increase in one variable leads to a decrease in another.

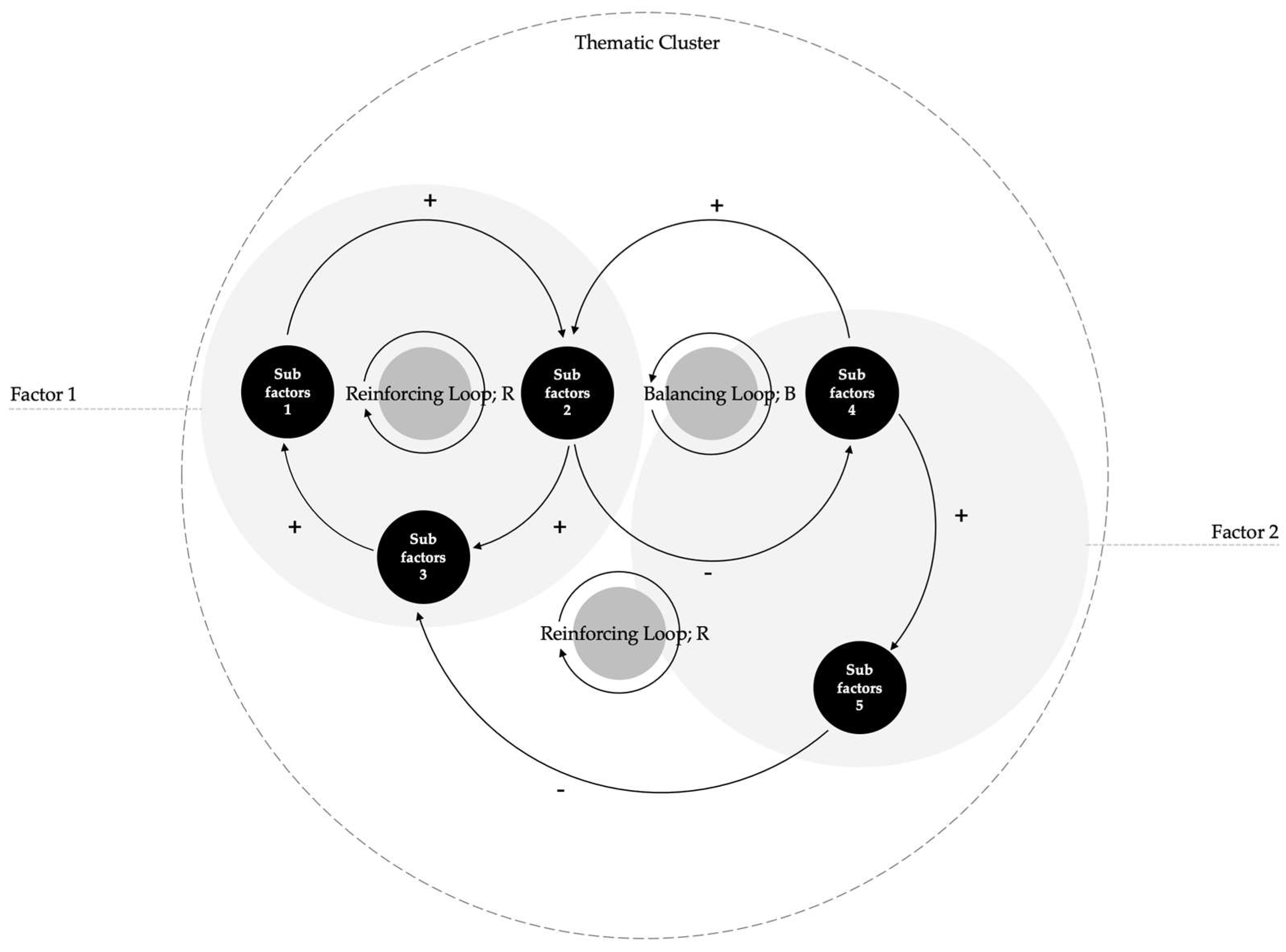

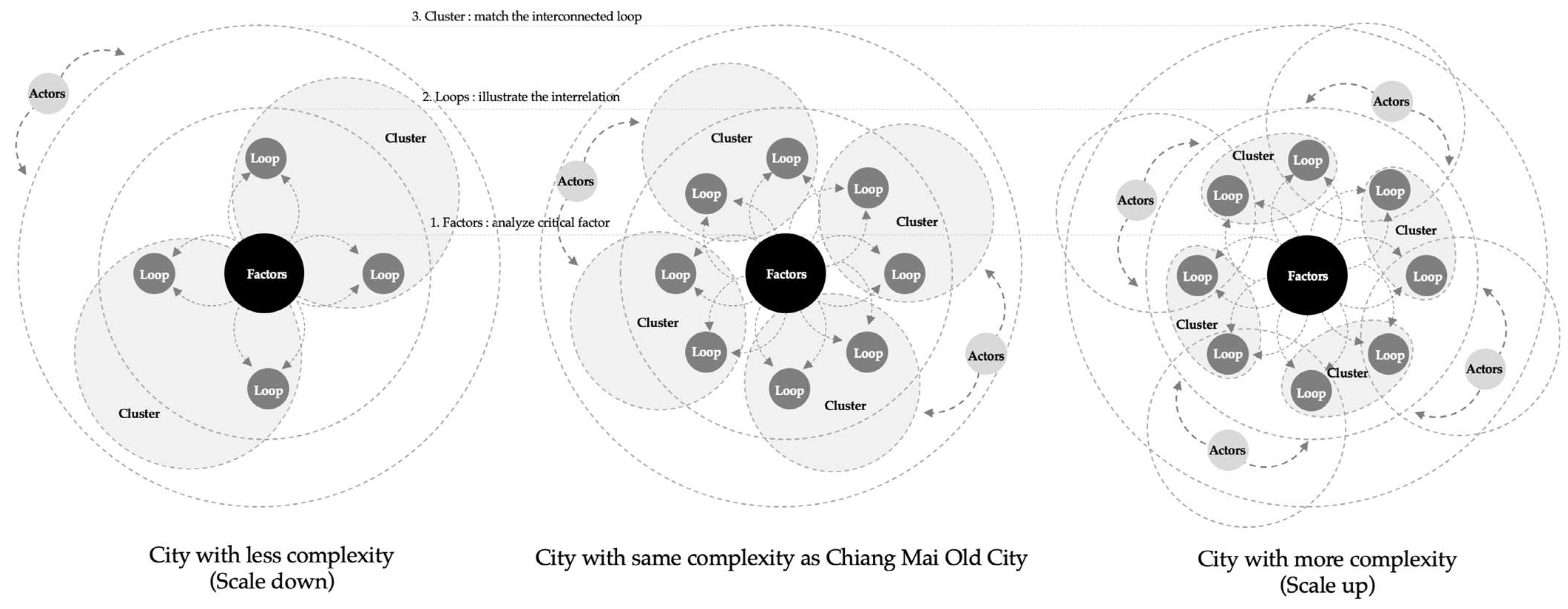

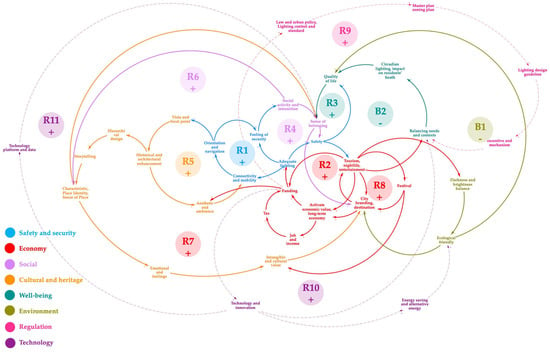

As these relationships were mapped, feedback loops emerged. These loops were either reinforcing (R), where changes intensify over time, or balancing (B), where the system stabilizes or counteracts itself. After forming these loops, the next step was to group related loops into broader categories or factors, which refer back to the eight factors of urban lighting master planning [17]. The loops were then further gathered into thematic clusters to guide the direction of lighting development. This process allowed for a clear understanding of how the different thematic cluster influence each other and revealed the dynamic possibilities within Chiang Mai Old City’s urban lighting system. The final step involved exploring alternative scenarios, using the insights from the CLDs to assess potential outcomes, as shown in Figure 5.

Figure 5.

A schematic diagram of the CLDs system. Source: Authors.

4. Results

This section consists of three parts. First, it presents the results from the in-depth interviews and focus groups, highlighting key findings and insights from stakeholder discussions are presented. Second, it visualizes the CLDs that illustrate the complex relationships and feedback loops identified in the urban lighting systems for Chiang Mai Old City are visualized. Finally, it discusses the implications of these urban lighting recommendations by proposing thematical clusters, possible initial scenarios, and phases for developing urban lighting master planning for Chiang Mai Old City.

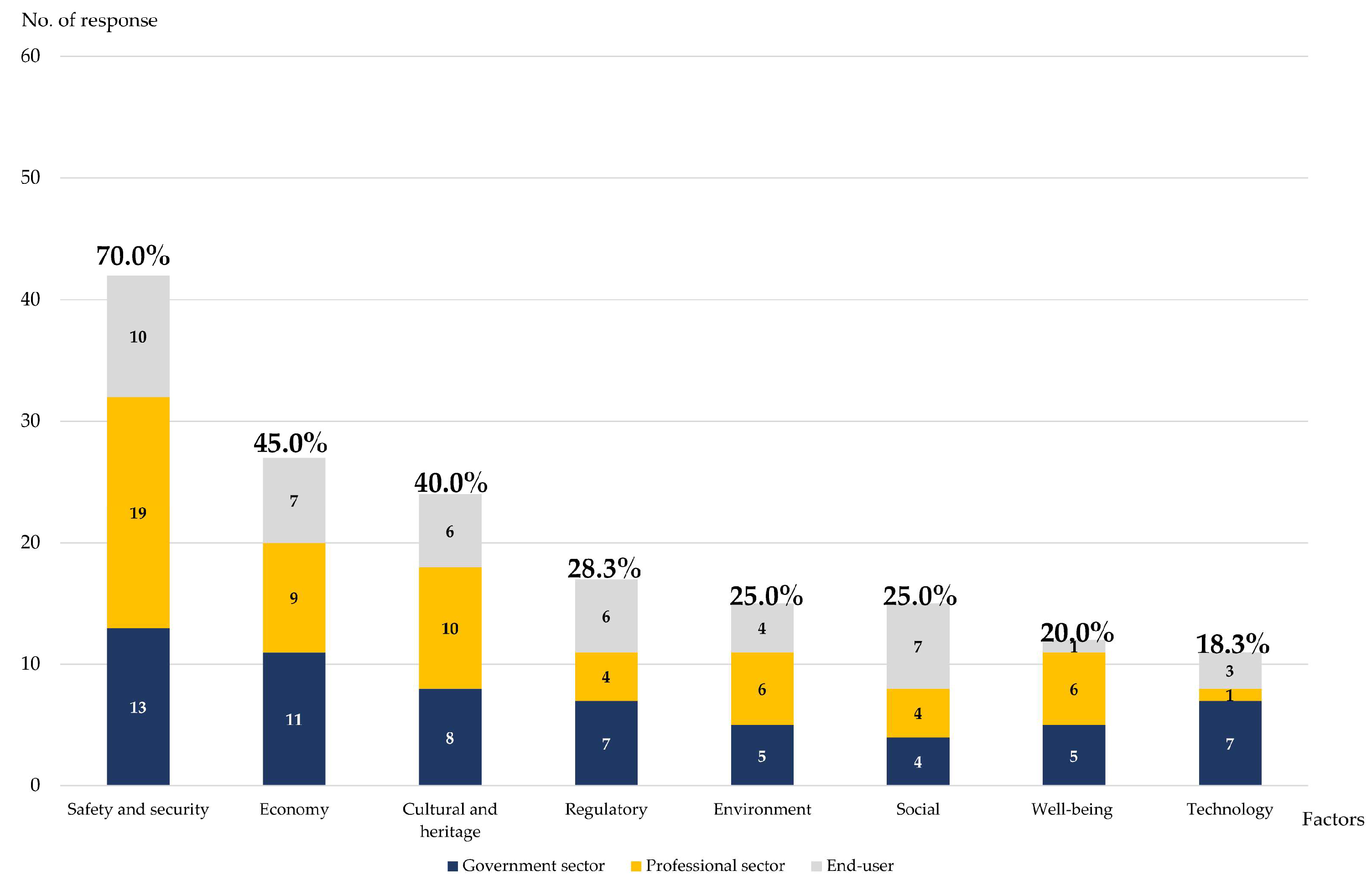

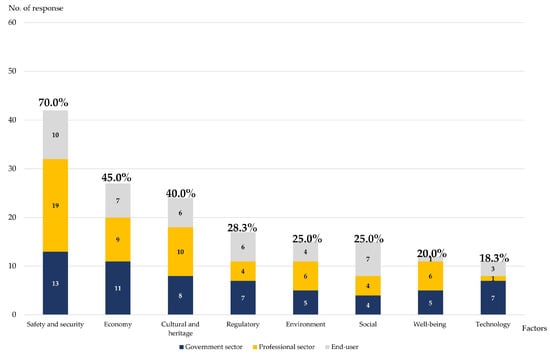

4.1. In-Depth Interviews and Focus Group Outcomes

4.1.1. Satisfaction with Existing Urban Lighting

The results from Question 1 asked participants to evaluate their satisfaction and dissatisfaction with the existing urban lighting in Chiang Mai Old City. The collected data were analyzed and categorized according to a framework of eight factors in urban lighting master planning, adapted from Zielińska-Dabkowska and Bobkowska [17]. The results provide a detailed account of participants’ feedback, revealing their understanding and concerns regarding these eight factors as well as emergence and prioritization of sub-factors, representing different facets of urban lighting with varying degrees of importance based on the frequency of responses from participants, as shown in Table 6.

Table 6.

Results from Question 1: Satisfaction and dissatisfaction with existing urban lighting in Chiang Mai Old City.

Safety and security factors emerged as the most significant, noted by 66.7% of participants. The most frequently mentioned was the need of adequate lighting for safety, followed by connectivity and mobility, reflecting the need for well-lit streets and public spaces to ensure ease of movement. A feeling of security and reassurance was closely linked to the role of lighting in promoting a sense of personal safety, while orientation and navigation was highlighted as important for wayfinding within the city. This reinforces the importance of urban lighting in creating safer nighttime environments for residents and visitors alike.

Cultural and heritage considerations were another major concern, highlighted by 58.3% of participants, referencing high aspects related to enhancing the characteristic, place identity, and sense of place. Other key aspects included historical and architectural enhancement, emphasizing the importance of preserving and showcasing the city’s heritage through lighting, aesthetic and ambience, hierarchical design, and storytelling through lighting, which indicates the importance of lighting in conveying the city’s cultural narrative. Additional concerns like vista and focal points, and intangible cultural value further suggest that lighting plays a vital role in revitalizing the city’s unique cultural identity.

The regulation framework surrounding urban lighting was another dominant theme, with 51.7% of participants referencing concerns as essential tools for balancing, preventing, and controlling light pollution to protect the well-being of residents and the city’s environment. Participants emphasized the importance of law and urban policy, lighting control, and lighting standards, implemented through master plans, zoning plans, and strategic plans as mediators. They further highlighted the role of lighting design guidelines to create the unity of city’ nighttime image. These responses indicate a strong demand for clearer regulations and policies to guide the development of lighting schemes that are both functional and aesthetically aligned with the city’s needs. Incentives for businesses and stakeholders to adopt these guidelines were also mentioned, signaling the need for supportive policies to encourage compliance.

Economic considerations were highlighted by 31.7% of participants. The impact of lighting on tourism and nightlife activities was particularly important, with lighting seen as a way to activate public spaces for the nighttime economy and tourism. Additionally, concerns regarding city branding and job and income generation were notable, indicating the need for further development to maximize the nighttime economy. Participants also pointed to festivals as an economic driver, where urban lighting plays a crucial role in creating memorable experiences, drawing crowds, and stimulating the local economy.

Social aspects of urban lighting were acknowledged by 28.3% of respondents, who emphasized how lighting can foster social activity and interaction as well as serve social needs. These insights reflect the importance of lighting in enhancing the livability of public spaces, creating environments that encourage social gatherings and community engagement, particularly in the evening.

Technological aspects of urban lighting were addressed by 16.7% of participants, with discussions surrounding technology and innovation, energy-saving solutions, and the use of technology platforms and data to enhance the efficiency and effectiveness of urban lighting. These responses suggest an emerging interest in the integration of smart lighting technologies and sustainable practices within the city’s lighting plan

Well-being issues were cited by 13.3% of participants, focusing on circadian lighting, particularly regarding its impact on residents’ health. The need for balancing lighting needs with the city’s cultural and environmental contexts was another concern, indicating that lighting should be designed to promote both well-being and environmental harmony.

Although less frequently mentioned, environmental concerns such as light pollution and darkness control were raised by 8.3% of participants. These issues highlight the need for the lighting master plan to consider ecological impacts, particularly in terms of reducing unnecessary light spillage and maintaining natural darkness where appropriate.

4.1.2. Perspective and Vision

In Question 2, participants were asked to share their perspectives and vision for the future of urban lighting in Chiang Mai Old City based on the eight factors in urban lighting master planning, as shown in Table 7.

Table 7.

Results from Question 2: Perspective and vision for urban lighting in Chiang Mai Old City.

Cultural and heritage factor were the most frequently discussed for the future of urban lighting, with 81.7% of participants mentioning aspects related to culture. The highest response frequency was associated with the characteristic, place identity, and sense of place. This suggests that participants strongly value lighting that emphasizes Chiang Mai Old City’s unique cultural identity and enhances its historical and architectural character. Other important cultural aspects including historical and architectural enhancement and aesthetic and ambience also play crucial roles in participants’ visions for future lighting.

Participants also emphasized the intangible cultural value of lighting and its role in storytelling, in revitalization of the city’s cultural assets. Hierarchical design, along with the use of vistas and focal points, were also mentioned as tools to shape the city’s character at night. Additionally, participants raised the significance of the emotional and sensory experiences elicited by lighting, showing a preference for lighting that fosters both visual and emotional connections with the city’s heritage.