Abstract

To respond more effectively to the current increasingly serious environmental problems, the boundary of corporate social responsibility is expanding. In this context, how to take green responsibility for each stakeholder has become a topic of concern for all sectors of society. However, there is still a gap in research on how green human resource management (GHRM) affects employees’ household pro-environmental behavior (PEB) from a cross-domain work–family perspective to achieve CSR more comprehensively. Our study argues that companies can use GHRM across the work–family boundary to influence employees’ household pro-environmental behaviors to achieve positive contributions to the social environment. Our study uses 310 questionnaires collected in southeastern China to conduct an empirical analysis and concludes that GHRM can positively shape green attitudes, help employees perceive green subjective norms, and develop green self-efficacy. Consistent with the findings of the Theory of Planned Behavior, individuals’ green attitudes, green subjective norms, and green self-efficacy can effectively enhance individuals’ household pro-environmental behavioral intentions, which in turn enables the prediction of individuals’ household pro-environmental behaviors. In conclusion, our study extends the influence of GHRM to a wider range of non-work domains and points the way to the full realization of corporate social responsibility by companies. In addition, our study emphasizes that with the subtle cultivation of companies, individuals can become fans of green and low-carbon behaviors, and through the widespread implementation of pro-environmental behaviors, it can reach a virtuous circle of environmental protection as a whole.

1. Introduction

The boundaries of corporate social responsibility (CSR) are expanding in response to an increasingly challenging dual carbon development situation—from “maximizing shareholder profits” to “triple bottom line reporting”. Companies need to take responsibility not only for internal stakeholders but also for external stakeholders, such as communities and the environment [1,2,3]. Green human resource management (GHRM) is a management activity that can create positive environmental outcomes for companies [4,5,6] and is a key tool for companies to fulfill their social responsibility. Although studies have verified that GHRM can help companies fulfill their responsibilities to employees, shareholders, and even the environment [1,7,8], the role of GHRM in helping companies fulfill their community responsibilities has been overlooked. With the rise in telecommuting, employee offices have shifted from the central office to the home—a spatial leap that has extended the primary spatial factors for companies to assume CSR from the focused formal workplace to the decentralized employee home. As families are important constituent units of communities, companies need to further consider how to take on CSR for communities under the premise of breaking through spatial boundaries, that is, to realize the spatial spillover of CSR under the influence of GHRM.

Individual pro-environmental behavior (PEB), as the conscious initiative of individuals to adopt the least negative ecological impact in their daily work and life [9], is a concrete manifestation of individual ethical behavior and a key factor for achieving CSR. Existing studies have demonstrated that employees’ workplace PEB is directly facilitated by corporate GHRM [10]. Meanwhile, some studies indicate that the implementation of GHRM within organizations can motivate employees to extend their eco-friendly behaviors beyond the workplace to their personal lives, thereby fostering a comprehensive green lifestyle. In fact, this positive spillover of PEB behavior contributes to the seamless integration of sustainability practices between work and family life [11]. However, no research has directly investigated the specific impact and mechanism of GHRM in employee household PEB. To explore more fully whether and how GHRM influences household PEB across domains, our study introduces the TPB theory. In accordance with the TPB theory, an individual’s motivation to engage in planned behavior is primarily influenced by three key factors: One is behavioral attitude, which refers to an individual’s positive or negative assessment of engaging in a specific behavior. The second factor is subjective norms, encompassing the social pressure that an individual feels when contemplating whether to engage in a particular behavior. The third is perceived behavioral control; that is, the individual perceives the ease or difficulty associated with engaging in a particular behavior [12]. According to TPB, employees can discern the organization’s environmental inclination through green recruitment in GHRM, thereby increasing their willingness to act in the environment [13]. Through green training and performance appraisal within GHRM, organizations can establish specific subjective norms within the workplace, so as to improve employees’ awareness of implementing green behaviors [14]. Furthermore, GHRM can incentivize employees to adopt green behaviors by offering green compensation [15]. Therefore, bringing in TPB may examine the interplay between green HRM policies and employees’ intentions and employee green behavior [16]. Similarly, individual PEB is influenced by green attitude, green subjective norms, and green self-efficacy in green contexts. In the workplace, employees will be guided by the company to perceive the green demands of society, the company, and others [17]. When returning home, employees are equally exposed to environmental pressures from society, the organization, and those around them [18], resulting in consistent work–family–green subjective norms. It can be seen that all three variables are factors that influence PEB in universal contexts and are not limited by spatial fields. Therefore, our study uses green attitude, green subjective norms, and green self-efficacy as a bridge between work and family to explore whether and how GHRM can promote household PEB by shaping environmentally friendly individuals.

Furthermore, due to the paradoxical property of PEB being “beneficial to others but costly to oneself” [19], individuals may refrain from implementing household PEB despite their PEB intention due to concerns about their costs/benefits. Based on TPB, when intentions do not adequately predict behavior [12], a gap between intentions and actual behavior arises, and we cannot simply study household PEB intention as a proxy variable for actual household PEB. Therefore, our study introduces household PEB intention and analyzes the gap between household PEB intentions and behaviors of environmental individuals to investigate how to improve the efficiency of GHRM in guiding employees’ environmental protection.

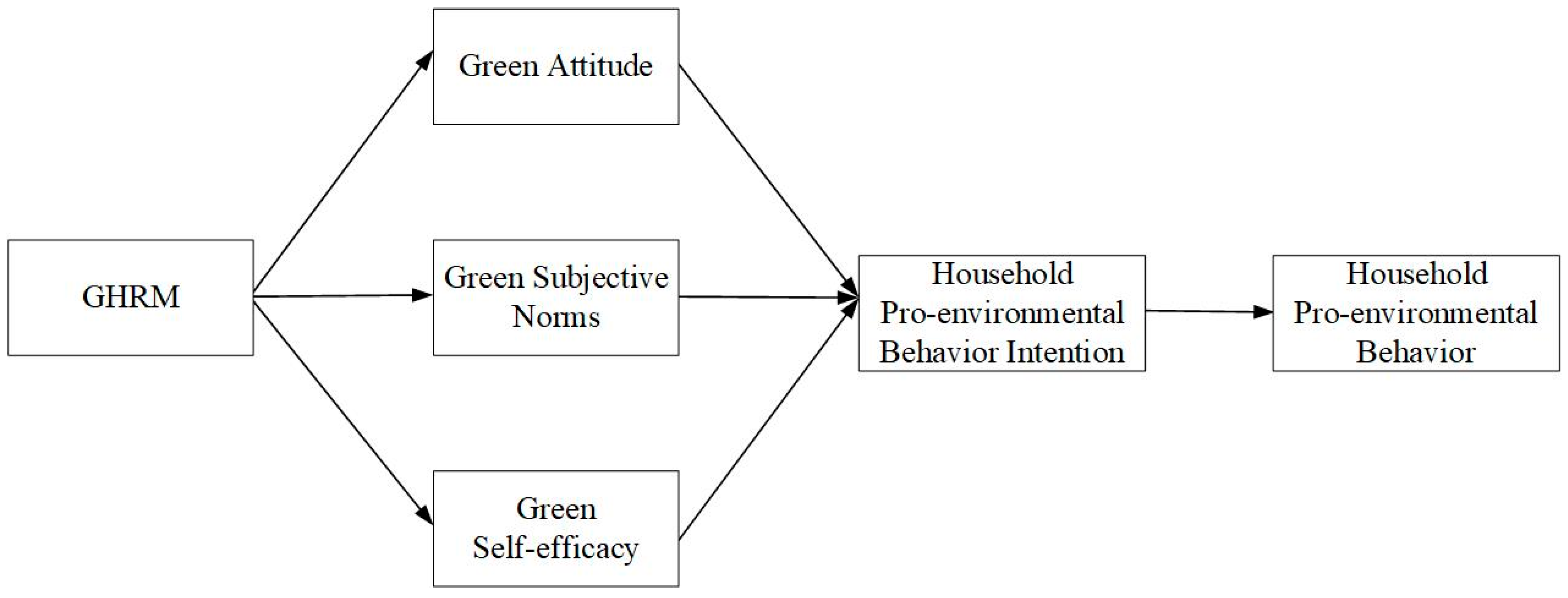

In summary, our study aims to investigate whether and how companies can use GHRM to guide employees to break the spatial boundaries, thus promoting employees’ household PEB. Our study contributes in three ways: First, based on the reality that CSR boundaries are expanding, our study investigates whether the ethical license effect can be suppressed and discovers the important role of GHRM in helping companies to take community responsibility across domains, thus expanding their positive contributions to society. Secondly, our study introduces three universal variables, namely, green attitude, green subjective norms, and green self-efficacy, to break through spatial limitations and expand the influence of GHRM on other fields. Finally, based on the logical chain of “GHRM shapes environmental individuals and environmental individuals predict household PEB”, our study combines GHRM and TPB, thus enriching the research on GHRM and TPB. The theoretical model of our study is shown in Figure 1.

Figure 1.

The theoretical model.

2. Hypotheses and Literature Review

2.1. Green Attitude and Household PEB Intention

A green attitude is the general concern of individuals about environmental protection in daily life and reflects people’s perceptions about the ecological environment in general [20] According to TPB, attitudes are one of the important predictor variables of behavioral intentions [12]. Focusing on the environmental domain, our study introduces green attitude to better predict employees’ household PEB intention. Individuals with a green attitude are more likely to endorse ecological protection and believe that such behaviors can produce long-term benefits for themselves and society [19], thus having stronger household PEB intention.

So how can individuals cultivate a positive green attitude? Our study argues that as a management activity integrating environmental concepts into corporate management, GHRM can influence the thoughts of all employees [21] and cultivate employees’ green attitude that is concerned with general environmental issues by enhancing their awareness of environmental issues. In addition, GHRM can create an environmentally friendly organizational culture that encourages employees to socialize following the company’s sustainability strategy [22]. Considering that a green attitude is the result of the socialization process [23], employees who are in an environmentally friendly culture will enhance their identity as environmentalists through environmental communication, interaction, and participation with the organization, and thus build green attitude in line with their surroundings. In summary, our study proposes the following hypotheses:

H1.

Green attitude is positively related to household PEB intention.

H2.

Green attitude plays a mediating role in the effect of GHRM on employees’ household PEB intention.

2.2. Green Subjective Norms and Household PEB Intention

Subjective norms are the degree of social pressure that individuals perceive that significant others expect individuals to behave in a particular way [12]. It is likewise a predictor of individuals’ behavioral intentions. Nowadays, the whole of society is paying close attention to low-carbon sustainability. In this context, individuals can recognize the esteem of surroundings for environmental protection and the strong desire to achieve green behaviors. Under such circumstances, individuals will assume a higher level of social and environmental pressure. What is more, individuals always have a greater initiative in the household and are able to freely decide whether to adopt PEB [24]. As a result, such pressure will force individuals to have stronger intentions to implement household PEB based on TPB.

GHRM is one of the methods that companies can use to respond to their stakeholders’ environmental pressures. It can be utilized to align an organization’s internal policies and practices with the environmental demands of a wide range of stakeholders [25], including developing greener production and management processes, increasing exposure to the overall societal demand for environmental protection, creating an environmental climate, and setting an environmental role model. In these ways, companies can communicate environmental stances and green expectations to employees on behalf of themselves and other stakeholders. Consequently, employees in such situations can perceive the support and expectations of significant others (including government, organizations, communities, the surroundings, etc.) for environmental protection [26], namely, green subjective norms. In addition, GHRM can use various green functional modules, such as green compensation and performance, to motivate or sanction employees according to the green criteria established by stakeholder requirements [25]. By doing so, employees may perceive the environmental concerns and expectations of the multiple stakeholders represented by the company, thus promoting the individual perception of green subjective norms. In conclusion, GHRM can guide employees’ participation in environmental practices and help them understand the encouragement and requirements for individuals to implement PEB by companies and multiple stakeholders, such as the government and society, thus promoting individuals’ perceptions of green subjective norms. In summary, our study proposes the following hypotheses.

H3.

Green subjective norms are positively related to household PEB intention.

H4.

Green subjective norms play a mediating role in the effect of GHRM on employees’ household PEB intention.

2.3. Green Self-Efficacy and Household PEB Intention

Green self-efficacy is an individual’s belief in their ability to organize and implement the actions needed to achieve green goals [27] Existing research has demonstrated that individuals with green self-efficacy can increase household PEB intentions, such as green purchase intentions [28], green recycling intentions [29], and green product-using intentions [30]. Therefore, our study concludes that green self-efficacy is likewise an important influencing factor for individual household PEB intention.

In addition, GHRM has a positive contribution to employees’ green self-efficacy [31]. When companies implement GHRM, employees can gain knowledge and skills about environmental protection through green training, receive opportunities to participate in environmental practices through green engagement, and earn economic and non-economic resources from green performance and compensation [32]. Based on TPB, as GHRM gives individuals more resources and opportunities to participate in environmental protection, individuals will have a stronger sense of control over the PEB; in other words, their green self-efficacy will be improved. In addition, because the knowledge, ability, and resources given to employees by GHRM will be transferred across borders with individual activities, individuals will also believe that they have the ability and self-confidence to benefit the broader social and environmental goals, thus achieving an increase in their general green self-efficacy. Therefore, GHRM can positively increase employees’ green self-efficacy with respect to general environmental issues. In summary, our study proposes the following hypotheses.

H5.

Green self-efficacy is positively related to household PEB intention.

H6.

Green self-efficacy plays a mediating role in the effect of GHRM on household PEB intention.

2.4. Household PEB Intention and Household PEB

PEB intention, as a strong internal stimulus, reflects the extent to which an individual is willing to try a certain PEB and put effort into it [33]. According to TPB, PEB intentions serve as direct predictor variables of behavior that can guide individuals’ PEB implementation [34]. And a meta-analytic study by Bamberg and Möser (2007) [35] showed the existence of a stronger positive effect of PEB intention on PEB in non-work contexts compared to PEB in the workplace. Therefore, we suggest that individual household PEB intention can positively predict individual household PEB.

Therefore, the following hypothesis is proposed in our study.

H7.

Household PEB intention is positively associated with individual household PEB.

3. Methods

3.1. Sample Collection

In our study, a paper-based questionnaire was used to survey several IT companies with telecommuting modes located in Southeast China. Since employees in the IT industry can choose a more flexible way of working remotely, they have more time to spend at home every day than other employees, and they have more opportunities to handle work at home [36]. For these employees, the boundaries between home and work become blurred, which further promotes the occurrence of work–family spillovers. As a result, the perceptions and experiences of these employees at work are more likely to influence their private lives and families [37]. Consequently, they are probably more inclined to carry out active household PEB compared to employees from other sectors.

In order to avoid the problem of common method bias, our study collected data from two data sources: leaders and employees. What is more, our study conducted two surveys in the process of a questionnaire using a time-lag design with an interval of one month. The first phase of the study was distributed in May 2023, and the second phase was conducted in June 2023. First, we surveyed 83 team leaders on team GHRM and 386 members of these teams on green attitude, green subjective norms, green self-efficacy, and household PEB intention. For the second survey, we administered a second questionnaire to employees who effectively completed the first questionnaire, asking them to report basic personal information and rate their recent household PEB.

The research process consisted of the following steps. Firstly, we obtained consent and authorization from the heads of each IT company (and its divisions). With the help of internal assistants, we finally enlisted 80 teams who agreed to conduct the questionnaire for data collection. Secondly, to facilitate the matching of questionnaires, we numbered the lists provided by the teams and asked the leaders and employees to fill in the correct numbers when completing the questionnaires. This ensured that after the collection was completed, we were able to match the leader and employee questionnaires according to the list numbers. Finally, according to the list for matching and eliminating irregular questionnaires, 62 valid leaders’ questionnaires and 310 valid employees’ questionnaires with a team size of 3–6 were retained in our study. We acquired the team GHRM data through leader questionnaires and subsequently aligned team leaders with their respective employees, thereby facilitating a more objective and precise assessment of the employees’ team GHRM. The valid return rate was 81.60%. Descriptive statistics showed that male employees accounted for 55.87% of the total number of employees; married employees accounted for 44.76% of the total.

3.2. Measures

Our study used authoritative scales to ensure the reliability and validity of the instruments. Our study followed a strict “translation-back translation” procedure and was evaluated on a 5-point Likert scale.

3.2.1. Green Human Resource Management (GHRM)

For better measurement, our study adopted Dumont’s (2017) [38] 7-item scale for GHRM with items such as “My team considers employees’ workplace green behaviors in performance evaluations”. And team leaders were asked to assess during the first survey. The Cronbach coefficient of this scale was 0.941.

3.2.2. Green Attitude (GA)

We employed a 4-item scale adapted by Liu et al. (2020) [39] to measure employees’ green attitudes. The items include “I believe that the balance of nature is very delicate and easily upset”, and were completed by employees in the first survey. The Cronbach’s alpha of this scale in our study was 0.973.

3.2.3. Green Subjective Norms (GSNs)

Our study measured subjective norms by adapting Paul et al.’s (2016) [40] scale. The revised scale consisted of four items, such as “Most people who are important to me think I should implement pro-environmental behaviors at home.”. Employees evaluated it in the first survey and the value of Cronbach’s alpha for this scale was 0.783.

3.2.4. Green Self-Efficacy (GSE)

Green self-efficacy was measured by adapting the green self-efficacy scale developed by Huang (2016) [27]. The revised scale consists of four items, such as “I believe I have the ability to take action to mitigate global warming and prevent climate change at work”. This scale was completed by employees in the first survey and had a Cronbach’s alpha of 0.872.

3.2.5. Household Pro-Environmental Behavior Intention (HPEBI)

Our study adapted the scale developed by Norton et al. (2017) [41] to measure individuals’ household PEB intention. The scale consisted of three items including “Tomorrow, I intend to act in environmentally friendly ways at home” and was evaluated by employees in the first survey. The Cronbach’s alpha of the scale in our study was 0.772.

3.2.6. Household Pro-Environmental Behavior (HPEB)

The scale used by Liu et al. (2020) [39] was adopted in our study to measure an individual’s household PEB, with three items including “How often do you sort the waste correctly”. This scale was answered by the employees in the second survey with a Cronbach’s alpha of 0.960.

3.2.7. Control Variables

Similar to Liu et al. (2021) [34], we also control for the potential effects possessed by gender, marital status, age, education level, and household income level on household PEB.

4. Results

4.1. Reliability Analysis

In our study, Cronbach’s α and composite reliability were used to judge the internal consistency and stability of the constructs, and the results are shown in Table 1.

Table 1.

Descriptive statistics, correlations, and reliability coefficients.

In addition, our study used a confirmatory factor analysis to test the discriminant validity among the six variables. The results are shown in Table 2, where the baseline model fit index was optimal (χ2/df = 2.333, RMSGA = 0.065, CFI = 0.951, TLI = 0.944, IFI = 0.952), indicating that the baseline model for the six variables had good discriminant validity.

Table 2.

Results of confirmatory factor analysis.

The average variance extracted (AVE) values of the six variables in our study were 0.698, 0.903, 0.632, 0.476, 0.536, and 0.891, which were mostly greater than 0.5, indicating that the constructs had good convergent validity. Moreover, the root mean square of AVE values for each latent variable was greater than its correlation coefficient (see Table 2), indicating good discriminant validity.

4.2. Common Method Bias

Although our study adopted multiple sources to collect data, the effect of common method bias was still not completely eliminated. To determine whether common method variance significantly affects results, our study compared the single-factor measurement model and the multi-factor measurement model (the current study model), and the results are shown in Table 1. The fit indexes of the baseline model met the requirements and significantly outperformed the single-factor model, indicating that the common method variance problem in our study was not serious.

4.3. Descriptive Statistics

The descriptive statistics as well as the correlation coefficients for the six variables involved in our study are shown in Table 2. The results showed that GHRM was significantly and positively correlated with green attitude (r = 0.793, p < 0.01), green subjective norms (r = 0.490, p < 0.01), and green self-efficacy (r = 0.282, p < 0.01). Also, green attitude, green subjective norms, and green self-efficacy had a significant positive correlation with household PEB intention (r = 0.276, p < 0.01; r = 0.271, p < 0.01; r = 0.389, p < 0.01), respectively. Finally, household PEB intention correlated significantly and positively with household PEB (r = 0.220, p < 0.01) as well, tentatively validating some of the hypotheses of our study.

4.4. Hypothesis Testing

To test the hypotheses, model comparisons were conducted in our study. The results are shown in Table 3. The baseline model of our study had the best fit (χ2 = 665.01, df = 265, RMSGA = 0.044, CFI = 0.944, TLI = 0.936, IFI = 0.944). Therefore, the baseline model was retained as the final structural model in our study.

Table 3.

Model comparisons.

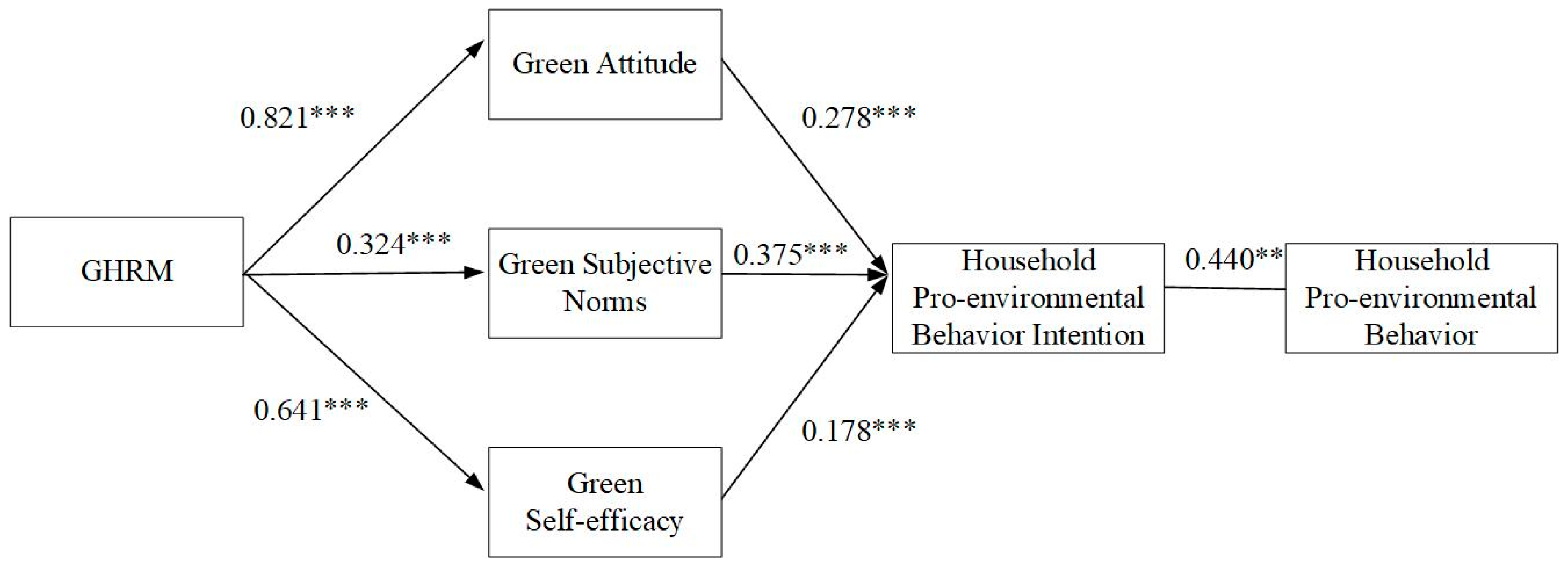

Subsequently, we conducted a path coefficient analysis and hypothesis testing based on the baseline model of our study. Among them, household PEB intention was significantly positively related to household PEB (β = 0.440, p < 0.001), and Hypothesis 7 was supported; green attitude (β = 0.278, p < 0.001), green subjective norms (β = 0.178, p < 0.001), and green self-efficacy (β = 0.375, p < 0.05) each had a significant positive relationship with household PEB intention. Hypotheses 1, 3, and 5 were supported. Furthermore, GHRM significantly and positively influenced green attitude (β = 0.821, p < 0.001), green subjective norms (β = 0.324, p < 0.001), and green self-efficacy (β = 0.641, p < 0.001), and Hypotheses 2, 4, and 6 were also initially tested. The standardized regression coefficients and significance levels for each pathway are shown in Figure 2.

Figure 2.

Path coefficients of theoretical model. Note—For more conciseness. Figure 2 does not list effects of control variables. * p < 0.05; ** p < 0.01; *** p < 0.001.

Finally, to further verify the significance of the mediating effect, bootstrap sampling was used in our study. The results are shown in Table 4. Green attitude played a significant mediating effect between GHRM and household PEB intention (BC 95% CI = [0.043, 0.328]); thus, Hypothesis 8 was validated. Green subjective norms had a significant mediating effect between GHRM and household PEB intention (BC 95% CI = [0.027, 0.341]); thus, Hypothesis 9 was confirmed. Green self-efficacy exerted a significant mediating effect between GHRM and household PEB intention (BC 95% CI = [0.014, 0.264]), and thus Hypothesis 10 was proven.

Table 4.

Path coefficients of the structural model.

5. Conclusions

First, our study verified the facilitative effect of GHRM on green attitude, a finding consistent with the derivation of Rayner and Morgan (2018) [24]. Second, our study found that GHRM can positively influence individual green subjective norms. This finding is a focus on Norton et al.’s (2014) [42] study in the area of GHRM, which argued that formal organizational policies can promote employees’ perceptions of social norms (i.e., subjective norms). Third, the demonstration of the positive impact of GHRM on employees’ green self-efficacy further confirms Farooq et al.’s (2021) [31] study. Fourth, considering GHRM as an antecedent variable for the three predictor variables in the TPB model, our study confirmed that green attitude, green subjective norms, and green self-efficacy can all significantly mediate the positive effect of GHRM on individual household PEB intention. These findings extend AI-Mamun et al.’s (2019) [30] efforts to introduce TPB into the environmental domain, enrich Muster and Schrader’s (2011) [22] discussion of GHRM’s ability to focus on home sites across domains, and further validate Rashid’s (2007) [43] finding that environmental management systems promote individuals’ private life implementation of PEB in their private lives.

5.1. Theoretical Implications

Our study contributes to the literature in several ways. First, our study focuses on the household PEB of employees in IT companies, and further expands the scope of CSR by introducing the impact of GHRM on the community in which employees live. Most existing studies on CSR have focused on the internal workplace [44], the environment [1], and customers in consumption sites [45], but neglected the impact on the community. Companies, however, happen to be closely related to the community, especially during the COVID-19 closure. Many IT companies have achieved telecommuting, and even Ctrip has announced the universalization of telecommuting. Therefore, to fill the research gap of comprehensively implementing CSR, our study takes IT companies as the research subject to verify that their formal environmental management tools (GHRM) can positively influence employees in their home places and make positive contributions to the sustainable development of society.

Secondly, our study has extended the influence of GHRM to the household by breaking the limits of the workplace. GHRM, which contributes significantly to the environment, is now widely studied. Many scholars have verified the positive contribution of GHRM to individual-level variables such as PEB [46], green creativity [47], and work engagement [48]. However, these studies have only explored the effects of GHRM on workplace factors and have not explored its effects on other domains beyond organizational boundaries. According to Muster and Schrader (2011) [22], GHRM not only influences employees’ behavior in the workplace but also promotes employees’ household behavior by using the thoughts and experiences developed in the workplace in their private lives. Therefore, our study enriches the existing research on GHRM and expands the scope of GHRM’s influence.

Finally, our study emphasizes the combination of GHRM and TPB to further enrich the research related to GHRM and individual behavior. Most of the current studies on how GHRM affects individual PEB have been explored from the perspective of a single mediating variable [49], and fewer studies have been able to introduce multiple concurrent mediators for the explanation. Our study applies TPB and introduces green attitude, green subjective norms, and green self-efficacy as antecedent variables of employees’ household PEB, thus providing a comprehensive exploration of how it affects the process of employees’ PEB and enriching the research related to GHRM and TPB.

5.2. Practical Implications

Our study provides some important management insights for IT firms and individuals. First, IT companies should pay attention to the impact of PEB on themselves and their communities. Nowadays, IT enterprise employees suffer from greater downward pressure in the industry. At this time, IT companies should, on the one hand, use reasonable work arrangements to ensure that employees are in normal working conditions and encourage the implementation of PEB so that they can also reap positive psychological resources such as a sense of meaning in times of crisis. On the other hand, this practice can also reduce the environmental pressure on the community, which in turn affects the broader community.

Second, companies should pay attention to the shaping of pro-environmental individuals. Individuals are the core of social networks, and their behavior has an impact not only on the company but also on their communities and whole society [50]. In this context, companies need to pay attention to their role in cultivating and shaping individuals and use GHRM to encourage them to become faithful implementers of environmental protection. In short, companies should implicitly cultivate individuals to become green and low-carbon advocates, so that PEB can be widely implemented.

Finally, employees should be aware of the importance of household PEB to provide individual strengths for the sustainable development of the whole society. Individuals tend to have greater initiative in the family place and are able to freely decide whether to adopt PEB [24]. Our study highlights the ability of individuals to take the initiative to conserve energy, recycle, and reduce waste in their home life, motivated and influenced by the organization’s formal system (GHRM). These household pro-environmental initiatives not only satisfy the pursuit of their environmental ambitions, but also help families to save economic resources. In addition, and most importantly, household PEB can also satisfy the whole society’s advocacy of low-carbon and environmentally friendly living. In short, the individual implementation of household PEB can reach a virtuous cycle of environmental protection as a whole and play a key role in the goal of sustainable development for society.

5.3. Limitations and Prospects

First of all, it should be noted that the samples used in this study were specifically selected from companies located in Southeast China. However, the willingness and implementation of individual PEB are influenced by various factors, including the economic and educational development stages of different countries, potential social norms, and differing cultural perspectives on the environment [51]. For instance, individuals from different cultures, such as collectivists and individualists, have different PEBs [52]. Therefore, our research may overlook other potential control variables related to the country and social culture, such as green values, long-term orientation values, individualism, and collectivism. Future studies could control for variables representing individual environmental characteristics to distinguish different choices of individuals with different value preferences under different countries and cultural backgrounds.

Secondly, this particular focus on IT companies may restrict the applicability of the results to other industries. Particularly, the IT industry may have conditions that more easily facilitate PEB through green technologies and digitization, potentially leading to an overestimation of the results. Future research should take into account the utilization of a wider range of data collection methods and incorporate samples from other cultural contexts as well as industries in order to augment the applicability and external validity of the results.

Moreover, although our study adopted the leader–employee pairing method to collect data, employees may be affected by social expectations and self-report bias when evaluating their household PEB. Future research could add data sources to report employees’ household PEB from a third-party perspective or use more objective measures of household PEB (e.g., carbon footprint averages) [53]. The combination of questionnaire data and objective data may better clarify the effect of GHRM on household PEB.

Finally, while we used a time-lag design with a one-month interval, this period may not be sufficient to track long-term changes in household PEB. Ref. [54] contended that incorporating a blend of short- and long-term measures in research design has gained significant importance in enhancing our understanding of the intricate relationship between work and family performance, as well as the enduring nature of behavioral change. Therefore, future studies can employ methods such as diary methods (for several weeks) or follow-up surveys to gain deeper insights into how the influence of GHRM on household PEB evolves or diminishes over time, and subsequently examine its long-term consequences.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, C.W. and H.L.; methodology, W.X.; software, W.X.; validation, W.X., H.L. and J.Z.; formal analysis, H.L.; investigation, C.W.; resources, C.W. and H.L.; data curation, H.L.; writing—original draft preparation, W.X.; writing—review and editing, J.Z.; visualization, C.W.; supervision, H.L.; project administration, H.L.; funding acquisition, H.L. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This work was supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (Project Number: 72474104; 71974189); and “the Fundamental Research Funds for the Central Universities”, No. 30924010601.

Institutional Review Board Statement

All procedures performed in studies involving human participants were in accordance with the ethical standards of the institutional and/or national research committee and with the 1964 Helsinki Declaration and its later amendments or comparable ethical standards.

Informed Consent Statement

We obtained participant informed consent. Informed consent was obtained from all individual participants included in the study. All individuals who participated in the study agreed to have their data published.

Data Availability Statement

The data that support the findings of this study are available on request from the corresponding author. The data are not publicly available due to privacy or ethical restrictions.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Jamali, D.R.; El Dirani, A.M.; Harwood, I.A. Exploring human resource management roles in corporate social responsibility: The CSR-HRM co-creation model. Bus. Ethic A Eur. Rev. 2015, 24, 125–143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Camilleri, M.A. Strategic Attributions of Corporate Social Responsibility and Environmental Management: The Business Case for Doing Well by Doing Good! Sustain. Dev. 2022, 30, 409–422. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abbas, J.; Dogan, E. The impacts of organizational green culture and corporate social responsibility on employees’ responsible behaviour towards the society. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 2022, 29, 60024–60034. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Roscoe, S.; Subramanian, N.; Jabbour, C.J.; Chong, T. Green human resource management and the enablers of green organisational culture: Enhancing a firm’s environmental performance for sustainable development. Bus. Strat. Environ. 2019, 28, 737–749. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raza, S.A.; Khan, K.A. Impact of green human resource practices on hotel environmental performance: The mod-erating effect of environmental knowledge and individual green values. Int. J. Contemp. Hosp. Manag. 2022, 34, 2154–2175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aftab, J.; Abid, N.; Cucari, N.; Savastano, M. Green human resource management and environmental performance: The role of green innovation and environmental strategy in a developing country. Bus. Strat. Environ. 2023, 32, 1782–1798. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sabokro, M.; Masud, M.M.; Kayedian, A. The effect of green human resources management on corporate social responsibility, green psychological climate and employees’ green behavior. J. Clean. Prod. 2021, 313, 127963. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tahir, A.H.; Umer, M.; Nauman, S.; Abbass, K.; Song, H. Sustainable development goals and green human resource management: A comprehensive review of environmental performance. J. Environ. Manag. 2024, 370, 122495. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krajhanzl, J. Environmental and proenvironmental behavior. Sch. Health 2010, 21, 251–274. [Google Scholar]

- Tu, Y.; Li, Y.; Zuo, W. Arousing employee pro-environmental behavior: A synergy effect of environmentally specific transformational leadership and green human resource management. Hum. Resour. Manag. 2022, 62, 159–179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Naqvi, S.; Siddiqui, D.A. Effect of GHRM Practices on Work Performance: The Mediatory Role of Green Lifestyle. 2019. Available online: https://papers.ssrn.com/sol3/papers.cfm?abstract_id=3486132 (accessed on 3 September 2024).

- Ajzen, I. The Theory of Planned Behavior. Organ. Behav. Hum. Decis. Process. 1991, 50, 179–211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, D.; Bai, Y.; Wu, H.; Wang, X. How does the perceived green human resource management impact employee’s green innovative behavior?—From the perspective of theory of planned behavior. Front. Psychol. 2023, 13, 1106494. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fawehinmi, O.; Yusliza, M.Y.; Wan Kasim, W.Z.; Mohamad, Z.; Sofian Abdul Halim, M.A. Exploring the Interplay of Green Human Resource Management, Employee Green Behavior, and Personal Moral Norms. SAGE Open 2020, 10, 2158244020982292. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fawehinmi, O.; Yusliza, M.Y.; Tanveer, M.I.; Abdullahi, M.S. Influence of green human resource management on employee green behavior: The sequential mediating effect of perceived behavioral control and attitude toward corporate environmental policy. Corp. Soc. Responsib. Environ. Manag. 2024, 31, 2514–2536. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ullah, W.; Abbas, S.M.; Wei, L.; Nadeem, A. Green Human Resource Management: A Decadal Examination of Eco-Friendly HR Practices. Pak. Bus. Rev. 2024, 25, 415–449. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, Y.J.; Kim, W.G.; Choi, H.-M.; Phetvaroon, K. The effect of green human resource management on hotel employees’ eco-friendly behavior and environmental performance. Int. J. Hosp. Manag. 2019, 76, 83–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, G.; Chen, Y.; Jiang, Y.; Paillé, P.; Jia, J. Green human resource management practices: Scale development and validity. Asia Pac. J. Hum. Resour. 2018, 56, 31–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Davis, T.; Hennes, E.P.; Raymond, L. Cultural evolution of normative motivations for sustainable behaviour. Nat. Sustain. 2018, 1, 218–224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bissing-Olson, M.J.; Iyer, A.; Fielding, K.S.; Zacher, H. Relationships between daily affect and pro-environmental behavior at work: The moderating role of pro-environmental attitude. J. Organ. Behav. 2013, 34, 156–175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Laszlo, C. The Sustainable Company: How to Create Lasting Value Through Social and Environmental Performance; Island Press: Washington, DC, USA, 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Muster, V.; Schrader, U. Green Work-Life Balance: A New Perspective for Green HRM. Z. Fur Pers.-Forsch. 2011, 25, 140–156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leppänen, J.M.; Haahla, A.E.; Lensu, A.M.; Kuitunen, M.T. Parent-Child Similarity in environmental attitudes: A Pairwise Comparison. J. Environ. Educ. 2012, 43, 162–176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rayner, J.; Morgan, D. An empirical study of ‘green’ workplace behaviours: Ability, motivation and opportunity. Asia Pac. J. Hum. Resour. 2018, 56, 56–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guerci, M.; Longoni, A.; Luzzini, D. Translating stakeholder pressures into environmental performance—The mediating role of green HRM practices. Int. J. Hum. Resour. Manag. 2016, 27, 262–289. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ajzen, I. Nature and Operation of Attitudes. Annu. Rev. Psychol. 2001, 52, 27–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, H. Media use, environmental beliefs, self-efficacy, and pro-environmental behavior. J. Bus. Res. 2016, 69, 2206–2212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharma, N.; Dayal, R. Drivers of Green Purchase Intentions: Green Self-Efficacy and Perceived Consumer Effectiveness. Glob. J. Enterp. Inf. Syst. 2017, 8, 27–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Janmaimool, P. Application of Protection Motivation Theory to Investigate Sustainable Waste Management Behaviors. Sustainability 2017, 9, 1079. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al Mamun, A.; Masud, M.M.; Fazal, S.A.; Muniady, R. Green vehicle adoption behavior among low-income households: Evidence from coastal Malaysia. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 2019, 26, 27305–27318. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Farooq, R.; Zhang, Z.; Talwar, S.; Dhir, A. Do green human resource management and self-efficacy facilitate green creativity? A study of luxury hotels and resorts. J. Sustain. Tour. 2022, 30, 824–845. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, W.; Chavez, R.; Feng, M.; Wong, C.Y.; Fynes, B. Green human resource management and environmental cooperation: An ability-motivation-opportunity and contingency perspective. Int. J. Prod. Econ. 2020, 219, 224–235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaiser, F.G.; Gutscher, H. The Proposition of a General Version of the Theory of Planned Behavior: Predicting Eco-logical Behavior. J. Appl. Soc. Psychol. 2006, 33, 586–603. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, X.; Wang, Q.-C.; Jian, I.Y.; Chi, H.-L.; Yang, D.; Chan, E.H.-W. Are you an energy saver at home? The personality insights of household energy conservation behaviors based on theory of planned behavior. Resour. Conserv. Recycl. 2021, 174, 355–384. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bamberg, S.; Möser, G. Twenty years after Hines, Hungerford, and Tomera: A new meta-analysis of psycho-social determinants of pro-environmental behaviour. J. Environ. Psychol. 2007, 27, 14–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leung, L.; Zhang, R. Mapping ICT use at home and telecommuting practices: A perspective from work/family border theory. Telemat. Inform. 2017, 34, 385–396. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, D.J.; Joseph Sirgy, M. Work-life balance in the digital workplace: The impact of schedule flexibility and tele-commuting on work-life balance and overall life satisfaction. In Thriving in Digital Workspaces: Emerging Issues for Research and Practice; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2019; pp. 355–384. [Google Scholar]

- Dumont, J.; Shen, J.; Deng, X. Effects of Green HRM Practices on Employee Green Behavior: The Role of Psychological Green Climate and Employee Green Values. Hum. Resour. Manag. 2017, 36, 118–128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, P.; Teng, M.; Han, C. How does environmental knowledge translate into pro-environmental behaviors?: The mediating role of environmental attitudes and behavioral intentions. Sci. Total Environ. 2020, 728, 138126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paul, J.; Modi, A.; Patel, J. Predicting green product consumption using theory of planned behavior and reasoned action. J. Retail. Consum. Serv. 2016, 29, 123–134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Norton, T.A.; Zacher, H.; Parker, S.L.; Ashkanasy, N.M. Bridging the gap between green behavioral intentions and employee green behavior: The role of green psychological climate. J. Organ. Behav. 2017, 38, 996–1015. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Norton, T.A.; Zacher, H.; Ashkanasy, N.M. Organisational sustainability policies and employee green behaviour: The mediating role of work climate perceptions. J. Environ. Psychol. 2014, 38, 49–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rashid, N.A. Employee Involvement in EMS/ISO 14001 and Its Spillover Effect in Creating Consumer Environmentally Responsible Behavior. Unpublished Master’s Thesis, University Sains Malaysia, Gelugor, Malaysia, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, Y.; Lu, T.; Qiao, Y. The effect of air pollution on corporate social responsibility performance in high energy-consumption industry: Evidence from Chinese listed companies. J. Clean. Prod. 2021, 280, 124345. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, H. Theory of green purchase behavior (TGPB): A new theory for sustainable consumption of green hotel and green restaurant products. Bus. Strat. Environ. 2020, 29, 2815–2828. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aboramadan, M.; Karatepe, O.M. Green human resource management, perceived green organizational support and their effects on hotel employees’ behavioral outcomes. Int. J. Contemp. Hosp. Manag. 2021, 33, 3199–3222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hameed, Z.; Naeem, R.M.; Hassan, M.; Nazim, M.; Maqbool, A. How GHRM is related to green creativity? A moderated mediation model of green transformational leadership and green perceived organizational support. Int. J. Manpow. 2022, 43, 595–613. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gim, G.C.; Ooi, S.K.; Teoh, S.T.; Lim, H.L.; Yeap, J.A. Green human resource management, leader–member exchange, core self-evaluations and work engagement: The mediating role of human resource management performance attributions. Int. J. Manpow. 2022, 43, 682–700. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Farrukh, M.; Ansari, N.; Raza, A.; Wu, Y.; Wang, H. Fostering employee’s pro-environmental behavior through green transformational leadership, green human resource management and environmental knowledge. Technol. Forecast. Soc. Chang. 2022, 179, 121643. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miller, D.; Tang, Z.; Xu, X.; Le Breton-Miller, I. Are Socially Responsible Firms Associated with Socially Responsible Citizens? A Study of Social Distancing During the COVID-19 Pandemic. J. Bus. Ethics 2021, 179, 387–410. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pisano, I.; Lubell, M. Environmental Behavior in Cross-National Perspective. Environ. Behav. 2017, 49, 31–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Riaz, W.; Gul, S.; Lee, Y. The Influence of Individual Cultural Value Differences on Pro-Environmental Behavior among International Students at Korean Universities. Sustainability 2023, 15, 4490. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lacroix, K. Comparing the relative mitigation potential of individual pro-environmental behaviors. J. Clean. Prod. 2018, 195, 1398–1407. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ilies, R.; Liu, X.-Y.; Liu, Y.; Zheng, X. Why do employees have better family lives when they are highly engaged at work? J. Appl. Psychol. 2017, 102, 956–970. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).