Abstract

It has become increasingly important to provide equal educational opportunities to all students for quality and sustainable education in classrooms with rapidly increasing diversity. In this context, communication skills, social intelligence and intercultural sensitivity are important competences that can affect teacher performance and efficiency in classrooms. Despite the importance of these competencies, empirical studies examining the relationships between these variables are scarce. Consequently, this study aimed to investigate the relationships between teacher candidates’ communication skills and their intercultural sensitivity and social intelligence levels through the application of structural equation modeling (SEM). The participants were selected from among the teacher candidates studying at Kütahya Dumlupınar University, a public university in Türkiye, using simple random sampling method. The results indicated that teacher candidates had high levels of communication skills, intercultural sensitivity and social intelligence. In addition, while there was a significant positive relationship between communication skills and intercultural sensitivity level and social intelligence level at low level, there was a significant positive relationship between intercultural sensitivity and social intelligence level at medium level. Furthermore, communication skills and intercultural sensitivity were found to be significant predictors of social intelligence and intercultural sensitivity had a partial mediating role in the relationship between communication skills and social intelligence. In the study, it was concluded that teacher candidates’ communication skills predicted social intelligence through intercultural sensitivity.

1. Introduction

With the second half of the twentieth century, migration waves caused by wars, natural disasters and economic developments paved the way for many people with different cultures and characteristics to live together. According to the data of 2021, the number of immigrants in the world has reached 281 million, and intercultural interaction has increased [1]. This transformation process, experienced due to intercultural interaction, has also had a profound impact on schools, which are the social institutions of the society. In other words, the increasing number of immigrant students in schools has proposed the cultural diversity phenomenon for the agenda [2]. In recent years, the number of students from different cultures in schools has gradually increased and a multicultural structure has emerged.

According to UNESCO [3], it is essential for sustainable development that all individuals, regardless of their differences, have access to equal educational opportunities. For quality and sustainable education, there is a fundamental need to establish an inclusive and egalitarian system that takes into account all children [4]. At this point, the concept of inclusion in education has been discussed intensively in recent years. The understanding of inclusion in education focuses on providing equivalent learning opportunities to children and young people, taking into account their different cultural, social and learning backgrounds [5]. In today’s world, where differences are increasing and diversifying with the impact of globalization, the idea that all students should be offered equal educational opportunities has increased the importance of inclusive education. As a result of these developments, the meaning of inclusive education as it first emerged has expanded, going beyond students with disabilities or special education needs. Inclusive education has thus reached a conceptual breadth that extends to individual learning differences, gender-based inequalities, immigrants, refugees, asylum seekers, cultural and social diversity [5,6]. Inclusion is one of the leading principles to be adopted for education for sustainable development [7].

In inclusive education, which is defined as a very general concept in the literature, multicultural education is seen as an important sub-dimension of inclusive education since cultural diversity is one of the features emphasized within the framework of taking individual characteristics into account [8]. Multicultural education is defined as “an idea, an educational reform and a process that aims to create equal educational opportunities for all students, including those from different racial, ethnic and social classes, and seeks to change and restructure the entire school” [9]. It is emphasized that education systems need to embrace diversity in order to create a philosophy of social change and that a pedagogical model that overcomes the dichotomy between intercultural and inclusive education and combines both should be addressed [10].

The education process of students from different cultures should aim to provide equal educational opportunities to all students by prioritizing respect for differences and intercultural sensitivity [11]. Because in today’s schools with the increased cultural diversity, it has become more and more important for teachers, one of the main actors of the education system, to have an intercultural sensitivity in the realization of an effective education process. This cultural diversity in schools has also increased the need for teachers with intercultural sensitivity [12]. Given the increasing cultural diversity in contemporary schools, it has become essential for teachers, as key actors within the education system, to possess intercultural sensitivity in order to facilitate an effective educational process. This growing cultural diversity in schools has underscored the need for teachers who are interculturally sensitive [13]. At the same time, students from different cultures are positively affected by the intercultural sensitivity of teachers and they become more successful in their education processes [14,15].

Teachers play an important role in realizing an inclusive educational process despite the growing differences between students. There are a number of competencies that teachers should have in order to successfully fulfill these roles. Multiculturalism experienced in schools requires teachers to have intercultural sensitivity, as well as effective communication skills and a high level of social intelligence in providing equal educational opportunities to students with different characteristics [16]. In a world where multiculturalism continues to grow, it is stated that the happiness and amicable lives of children depend on the existence of individuals with high social intelligence who do not discriminate, able to use communication effectively, and give importance to the interests and needs of individuals with different characteristics [17]. Teachers have an crucial role in raising individuals with high social intelligence levels [18]. Teacher candidates, therefore, play an active role in the realization of sustainable development [19].

In the literature, various studies have examined the relationships between teachers’ communication skills, intercultural sensitivity, and social intelligence, alongside a range of organizational variables. For instance; previous studies on communication skills analyzes variables such as self-efficacy [20], organizational cynicism [21], empathic tendency [22], speech anxiety [23] and classroom management efficacy perception [24]. Considering the studies on intercultural sensitivity; it is understood that they survey the relationship of intercultural sensitivity with variables such as subjective well-being [12], perception of cultural difference [25] its effect on student leadership [26] and the level of ethnocentrism [27]. And studies on the level of social intelligence focus on issues such as multicultural education manner [16], empathy [28], and practices within the scope of drama lesson [29]. However, when we reviewed the literature, we did not encounter with any study examining the relationship between the concepts of communication skill, intercultural sensitivity and social intelligence, which are thought to be related to each other. In this research, we try to explore the relationships between communication skills, intercultural sensitivity and social intelligence level. We also seek to answer how teacher candidates’ communication skills and intercultural sensitivity affect their social intelligence levels. We focus on how intercultural sensitivity mediates the relationship between communication skills and social intelligence. In other words, this research aims to reveal the importance of strengthening pre-service teachers’ communication skills and intercultural sensitivity to improve their social intelligence levels. Another important point about this study is that it aims to bring a new perspective to teacher education research by expanding the research ground on communication skills, intercultural sensitivity and social intelligence, which are the competences that effective teachers should have. Therefore, the following research questions were tried to be answered in this study:

Research Question 1. Are teacher candidates’ communication skills a significant predictor of their social intelligence levels?

Research Question 2. Are teacher candidates’ communication skills a significant predictor of their intercultural sensitivity levels?

Research Question 3. Is the level of intercultural sensitivity of teacher candidates a significant predictor of their social intelligence levels?

Research Question 4. Does intercultural sensitivity have a mediating role in the effect of teacher candidates’ communication skills on their social intelligence levels?

In addition, considering the growing number of immigrant students, now constituting approximately 6% of the total student population, and the educational needs of this large mass, it can be stated that Türkiye faces significant challenges in the domain of multicultural education. As a matter of fact, Türkiye has had to implement critical educational reforms since 2011 in order to overcome this major issue [5]. In countries such as Türkiye, where there is mass refugee influx, various problems may arise in terms of integrating these individuals into education system, as well as problems related to economic, legal and social life. Thus, there is a need for teachers and teacher candidates, who are sensitive to cultural diversity and capable of facilitating an effective educational process in such environments. In addition, it is thought that revealing the relationship between teacher candidates’ communication skills, and their intercultural sensitivity and social intelligence levels will contribute to the realization of an effective education process in today’s schools where differences are high, and to determine which qualification teachers should have.

1.1. Conceptual Framework

1.1.1. Communication Skill

The origins of communication can be traced back to the advent of human language [30]. The fundamental purpose of communication with other people can be expressed as “to influence, to be affected and to be understood” [31]. As such, it is possible to reach many definitions of communication in studies explaining the concept of communication. Cüceloğlu [32] explains the communication as an exchange of meaning that begins with the awareness of other people; Lasswell [33], as “who says what, to whom, with what channel and effect?”; TDK [Turkish Language Association] [34], as “transmitting feelings, thoughts or information to others by any conceivable means”.

A healthy and successful communication process depends on effective communication skills. It is known that individuals with effective communication skills do not have difficulty in solving the problems encountered and they succeed quickly in their career [35]. The teaching profession is also one of the professions with intense communication, and the essence of educational activities is accepted as communication [36]. Because teachers who use communication effectively makes positive contribution to personality development of students and interaction with the environment [35], creation of a good classroom atmosphere [37], establishing positive relationships with students [38], and student success [39]. In other words, the inability of teachers to communicate effectively with students can affect students’ academic success negatively [40]. In brief, it is understood that communication skills are necessary in order to achieve positive outcomes in schools.

1.1.2. Intercultural Sensitivity

Intercultural sensitivity focuses on the individual’s sensitivity towards different cultures and people from different cultures. Öğüt and Olkun [41] define intercultural sensitivity in their study as “a person’s ability to understand and develop cultural differences that encourage an appropriate and effective behavior in intercultural communication”. Chen [42] states that individuals with developed intercultural sensitivity willing to understand different cultures, develop positive attitudes and interact. Bhawuk & Brislin [43] and Matkin and Barbuto [44] state the importance of showing sensitivity to the opinions of culturally different individuals.

In recent years, the number of students from different cultures has steadily increased and a multicultural structure has emerged in schools, which are among the institutions that are most closely affected by the developments in society. This cultural diversity experienced in schools requires sensitivity to the thoughts and opinions of students with different cultures and different characteristics [45]. On the other hand, providing equal education opportunities to all students in the realization of an effective education should not be ignored. Because it is known that teachers with insufficient intercultural sensitivity are unsuccessful in the education processes of students from different cultures [46,47].

1.1.3. Social Intelligence

The concept of social intelligence is based on the studies done by Thorndike. Thorndike defines social intelligence as “the ability to understand and manage people, and act wisely in human relations” [17]. Renner and Feldman [48] draw attention to the fact that social intelligence is the skills used in the communication process. Social intelligence is the ability to integrate in establishing coherent social interaction [49]. Therefore, concept of social intelligence is directly related to cognitive and behavioral structure [50].

Social intelligence is a type of intelligence that is effective in the development and success of the individual in all areas. Individuals with high social intelligence are more successful in understanding, empathizing, interacting and listening to other people [51]. Teaching profession is one of the professions which interaction is intense with students, parents and other people. For this reason, individuals who will teach are expected to be individuals with advanced social intelligence. In studies conducted on teachers concerning social intelligence, positive relationships were found between teachers’ social intelligence levels and multicultural education attitudes [16]. Thus, enhancing the social intelligence levels of teachers in schools characterized by increasing cultural diversity may significantly contribute to the provision of equal educational opportunities for all students.

1.1.4. Relationship between Communication Skill, Intercultural Sensitivity and Social Intelligence

Irregular migration flows, which have been experienced and still continuing in the world in recent times, have revealed the coexistence of many people with different cultures. This situation was accompanied with being sensitive to different cultures, being able to communicate effectively with people who has different characteristics, and socializing. These developments have increased the communication and interaction between people from different cultures in the society [52]. It has been inevitable for schools to be affected by this cultural mobility in the society and a multicultural structure has emerged in schools.

Teachers have important duties in terms of intercultural sensitivity and effective communication skills [53]. Providing equal education opportunities to all students requires effective communication skills and high social intelligence. Because teachers with effective communication skills and high social intelligence can more easily meet the needs of students with different characteristics in culturally diverse classes [16]. According to Goleman [17], in a world where multiculturalism is increasing, the happiness of children depends on the existence of individuals with high social intelligence who attach importance to the interests and needs of individuals with different characteristics and can use communication effectively. People with high social intelligence can communicate effectively with individuals from different cultures and with different characteristics [50]. People with advanced social intelligence can have more quality communication with other individuals [54]. In addition, it can be said that social intelligence has a key role in solving problems arising from communication [55]. All these explanations and inferences point to the relationship between communication skills, intercultural sensitivity and social intelligence.

1.1.5. Research Objective

This study tried to determine the relationship between the communication skills of teacher candidates, and their levels of intercultural sensitivity and social intelligence. In line with the main purpose of the research, the following hypotheses were tested;

H1:

Communication skills of teacher candidates predict their social intelligence levels positively and significantly.

H2:

Communication skills of teacher candidates predict their intercultural sensitivity levels positively and significantly.

H3:

The intercultural sensitivity level of teacher candidates predicts their social intelligence levels positively and significantly.

H4:

Intercultural sensitivity level has a mediating role in the relationship between teacher candidates’ communication skills and social intelligence levels.

2. Materials and Methods

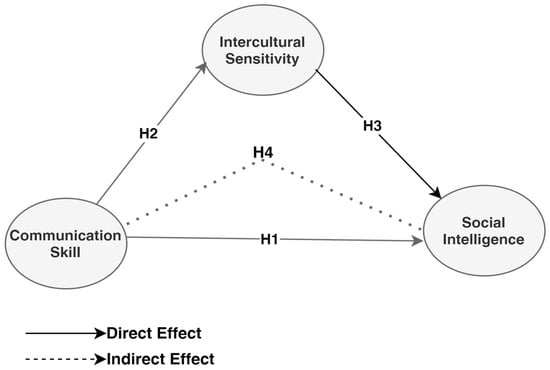

2.1. Research Model

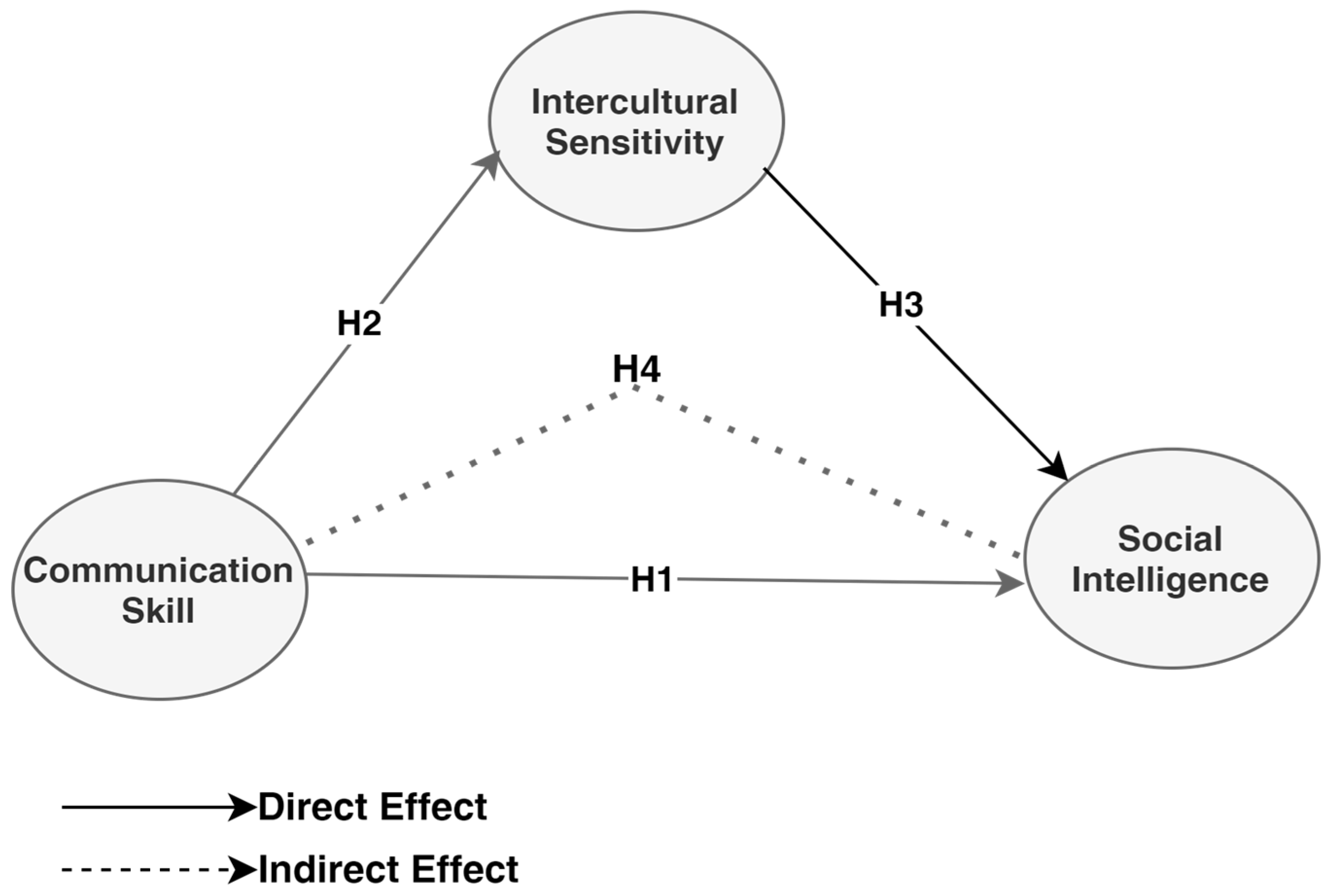

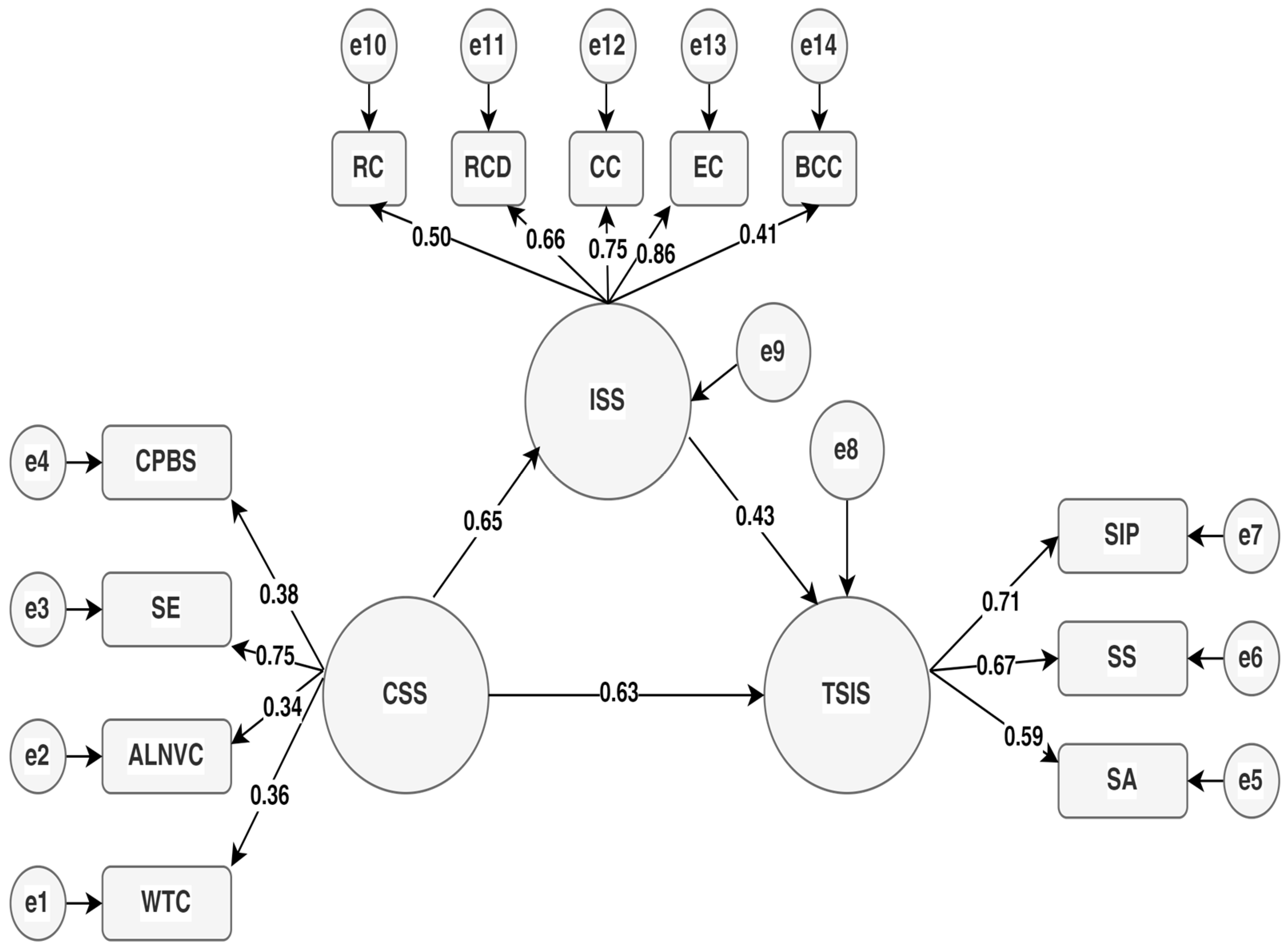

This research, which tries to determine the relationship of teacher candidates’ communication skills with their levels of intercultural sensitivity and social intelligence, was designed in relational screening model. Relational screening model is a research model in which the direction of the relationships between two or more variables is determined [56]. The relationships between the variables of the study were tested with the hypotheses developed by the researchers. The research model created according to the hypotheses was examined by structural equation modeling (SEM). The model of the study is given in Figure 1 (Straight lines indicate direct effect, dashed lines indicate indirect effect).

Figure 1.

Model tested in research.

As seen in Figure 1, the independent variable of the study was determined as the communication skills of the teacher candidates, the intercultural sensitivity as the mediator variable, and the social intelligence level as the dependent variable.

2.2. Population and Sample

The population of the research consists of 1394 teacher candidates studying at the Faculty of Education of Kütahya Dumlupınar University in Türkiye, in the 2021–2022 academic year; the sample consists of 318 teacher candidates determined by simple random sampling method. In simple random sampling method, every unit in the population has equal chance to be included in the sample [57]. Simple random sampling method was preferred in order to ensure that each participant’s sampling rate (chance) was the same. In the determination of the sample size, the sample size calculation formula and the sample size table were used. Accordingly, it is known that 301 participants are sufficient for a population of 1394 people at 95% confidence level with 5% error [58]. In this context, it can be said that 318 teacher candidates represent the population sufficiently. 254 (79.9%) of teacher candidates participating in the research were female and 64 (20.1%) were male; 234 (73.6%) were between the ages of 19–22, 84 (26.4%) were between the ages of 23–29; 98 (30.8%) live with their families, 163 (51.3%) live in dormitories/pension, 57 (17.9%) live with their friends; 79 (24.8%) of them studying in department of Preschool Teaching, 68 (21.4) Primary School Teaching, 22 Science Teaching, 52 (16.4%) Elementary Mathematics Teaching, 63 (19.8%) Social Studies Teaching, 34 (10.7%) Turkish Language Teaching. The number of participants registered in the 1st year is 41 (12.9%), the number of participants registered in the 2nd year is 93 (29.2%), the number of participants registered in the 3rd year is 75 (23.6%), and the number of participants registered in the 4th year is 109 (34.3%).

2.3. Data Collection Tools

Explanations about the data collection tools used in the research shown below.

2.3.1. Communication Skills Scale (CSS)

In order to measure the communication skills of university students the “Communication Skills Scale (CSS)”, consisting of 4 dimensions and 25 items developed by Korkut Owen and Bugay [59], was used. The communication principles and basic skills dimension of the scale consists of 10 items (1., 3., 6, 13., 15., 16., 21., 23., 24. and 25.), while the self-expression dimension consists of 4 items (2., 5, 17 and 20), active listening and non-verbal communication dimension consists of 6 items (10., 11., 12., 18., 19. and 22.), and willingness to communicate consists of 5 items (4., 7., 8. and 14.). There is no reversed item in the CSS and it is graded between “(1) Never and (5) Always” in a 5-point Likert scale type. The communication principles and basic skills dimension, self-expression dimension, active listening and non-verbal communication dimension, willingness to communicate dimension and reliability internal consistency coefficient of the scale were identified as 0.79, 0.72, 0.64, 0.71 and 0.88, respectively [60]. According to the confirmatory factor analysis (CFA) results of the CSS, the adaptive values reported to be within the acceptable range (x2/sd = 1.40, CFI = 0.91, IFI = 0.91, TLI =0.90, RMSEA = 0.046, SRMR = 0.068) [60]. Within the scope of this research, the construct validity of the CSS was re-examined with confirmatory factor analysis. The construct validity results of the CSS indicate that the 4-dimensional structure is compatible with the research data (x2/sd = 2.75, CFI = 0.90, IFI = 0.90, TLI = 0.89, RMSEA = 0.074, SRMR = 0.0722) [60,61,62]. The communication principles and basic skills dimension, self-expression dimension, active listening and non-verbal communication dimension, willingness to communicate dimension and Cronbach’s Alpha internal consistency reliability coefficient regarding the whole of the CSS were determined as 0.93, 0.71, 0.80, 0.75 and 0.84, respectively; McDonalds reliability coefficients 0.93, 0.75, 0.84, 0.78 and 0.84, respectively.

2.3.2. Intercultural Sensitivity Scale (ISS)

Aiming to measure the level of intercultural sensitivity of the participants, ISS was developed by Chen and Starosta [63] and adapted into Turkish by Bulduk, Tosun, and Ardıç [64]. ISS is a 5-dimensional and 24-item scale. Responsibility in communication, which is the first dimension of ISS, consists of 7 items (1., 11., 13., 21., 22., 23., and 24.), respect for cultural differences dimension consists of 6 items (2., 7., 8., 16., 18. and 20.), self-confidence in communication dimension consists of 5 items (3., 4., 5., 6. and 10.), communication enjoyment dimension consists of 3 items (9., 12. and 15.), the dimension of being careful in communication consists of 3 items (14., 17. and 19.). 9 items of ISS are reversed items (2., 4., 7., 9., 12., 15., 18., 20. and 22.) and the scale items are 5-point Likert scale type “(1) I strongly disagree and (5) I completely agree. Sub-dimension and grand total scores can be obtained in the scale. A high score from the scale means high intercultural sensitivity. The Cronbach Alpha internal consistency reliability coefficient regarding the whole of the ISS was calculated as 0.72 [61]. For this study, the validity and reliability of the ISS were recalculated. As a result of confirmatory factor analysis, it was determined that the 5-dimensional structure of the ISS is in the appropriate value ranges with the research (x2/sd = 3.053, CFI = 0.86, IFI = 0.87, TLI = 0.85, RMSEA = 0.080, SRMR = 0.0991) [60,61,62]. Responsibility in communication dimension, respect for cultural differences dimension, self-confidence in communication dimension, enjoying communication dimension, being careful in communication dimension and Cronbach’s Alpha internal consistency reliability coefficient regarding the whole of the ISS were identified as 0.83, 0.73, 0.80, 0.67., 0.86 and 0.89 respectively; McDonalds reliability coefficients as 0.85, 0.76, 0.81, 0.69., 0.88 and 0.89 respectively.

2.3.3. Tromso Social Intelligence Scale (TSIS)

TSIS is a scale originally developed by Silvera, Martinussen and Dahl [65] in order to measure the social intelligence levels of university students and adapted into Turkish by Doğan and Çetin [50]. The scale consists of 21 items and 3 dimensions. The social information process dimension, which is the first dimension of TSIS, consists of 8 items (1., 3., 6., 9., 14., 15., 17. and 19.), the social skills dimension consists of 6 items (4., 7., 10., 12., 18. and 20.), social awareness dimension consists of 7 items (2., 5., 8., 11., 13., 16. and 21.). 11 items of the TSIS are reversed items (2., 4., 5., 8., 11., 12., 13., 15., 16., 20. and 21.) and the scale items rated in 5-point Likert scale type from “(1) Not suitable at all, (5) Completely suitable”. Social information process dimension, social skills dimension, social awareness dimension and Cronbach Alpha internal consistency coefficient regarding the whole of TSIS were determined as 0.77, 0.84, 0.67 and 0.83, respectively [51]. In addition, the confirmatory factor analysis (CFA) results of the TSIS showed that the adaptive values of the data were within the acceptable range x2 = 621.26 p = 0.00, CFI = 0.95, IFI = 0.95, RFI = 0.91, NFI = 0.92, GFI = 0.92, RMSEA = 0.057) [51]. In the context of the current research, the validity and reliability of the TSIS were re-examined. Accordingly, as a result of the confirmatory factor analysis of TSIS, it was found that the 3-dimensional structure was within acceptable ranges with the research data x2/sd = 3.616, CFI = 0.81, IFI = 0.81, GFI = 0.84, AGFI = 0.80, RMSEA = 0.091, SRMR = 0.0725 [60,61,62]. The social information process dimension, social skills dimension, social awareness dimension and Cronbach’s Alpha internal consistency reliability coefficient regarding the whole of TSIS determined as 0.77, 0.78, 0.72 and 0.85, respectively; McDonalds reliability coefficients as 0.78, 0.82, 0.73 and 0.86, respectively.

2.4. Data Collection Process and Analysis of Data

Ethical approval dated 14 April 2022 and numbered 2022/04 was obtained from the Social and Human Sciences Scientific Research and Publication Ethics Committee of the Rectorate of Kütahya Dumlupınar University, a University in Türkiye, for the realization of the research. In addition, at all stages of the research process, the principles of scientific research and publication ethics were taken into consideration.

In the analysis of the research data, descriptive statistics, Pearson product-moment correlation, confirmatory factor analysis (CFA) and structural equation modeling (SEM) were used. First of all, assignments were made with the EM algorithm (expectation maximization) technique in substitution for the items left blank in the scales. Then, it was checked whether the research data provided the necessary assumptions for SEM. In this framework, the extreme and Mahalanobis distance values of the research were examined. 24 scale data that did not have a Z score between −3 and +3 and exceeded the Mahalanobis distance value were excluded from the analysis. Thus, the analyses were carried out on the remaining 318 unit.

The skewness and kurtosis values were checked by taking the total scores of the scales under the assumption of normality. Accordingly, the skewness values of the scales were found to be between −0.798 and −0.378; kurtosis values were found to be between −0.380 and −0.724. The fact that the skewness and kurtosis values of the study are between −1.5 and +1.5 means that the research data are normally distributed [66]. In addition, the research data were also examined in terms of linearity, multicollinearity problem and autocorrelation. Linear relationship between the variables in the scatter diagram indicates that the linearity assumption is provided. The fact that correlation values between the variables is less than 0.90 and in the range of 0.25 and 0.59; the tolerance value greater than 0.20 and exactly 0.938; the VIF value is less than 10 and exactly 1.066, and the Durbin-Watson value is between 1–3 and exactly 1.601 proves that there is no multicollinearity problem and autocorrelation [67]. The direct and indirect predictive effects of the variables were determined by path analysis in accordance with the structural equation modeling (SEM), and the suitability of the established models was interpreted according to various adaptive values. The significance of the mediation effect in the study was determined according to 10,000 bootstrap and confidence intervals. The significance of the mediation effect was determined according to fact that the lower and upper confidence intervals did not include zero [68]. However, in order to determine whether the mediating effect is partial or full mediation, the following steps suggested by Baron and Kenny [69] were taken into account: (a) the independent variable should significantly predict the dependent variable, (b) the independent variable should significantly predict the mediating variable. (c) the mediating variable should significantly predict the dependent variable, (d) the predictive effect of the independent variable on the dependent variable should disappear or decrease when the mediating variable is added to the model together with the independent variable. With the inclusion of the mediating variable in the model, the loss of significance of the predictive effect of the independent variable on the dependent variable is interpreted as full mediation, and its decrease is interpreted as partial mediation. All analyzes of the research were made with SPSS 24.00 and AMOS 24.00 programs, and the results of the research were evaluated at 0.01 and 0.05 significance levels.

3. Results

3.1. Findings Related to Descriptive and Correlation Values of the Research

Table 1 shows the results of the Pearson correlation analysis between the descriptive statistics (mean and standard deviation) on the communication skills, intercultural sensitivity, social intelligence levels of the teacher candidates and the variables.

Table 1.

Findings related to descriptive and correlation values of the research.

As seen in Table 1, the communication skills of teacher candidates ( = 3.80; Ss = 0.48), cross-cultural sensitivity ( = 4.18; Ss = 0.32) and social intelligence levels (=3.89; Ss = 0.38) was determined as “high”. According to the Pearson correlation analysis, there is a low-level significant positive correlation between the communication skills and intercultural sensitivity level (r = 0.25; p < 0.01), and the communication skills and social intelligence level (r = 0.28; p < 0.01) of the teacher candidates; moderately significant positive correlation between intercultural sensitivity and social intelligence level (r = 0.59; p < 0.01).

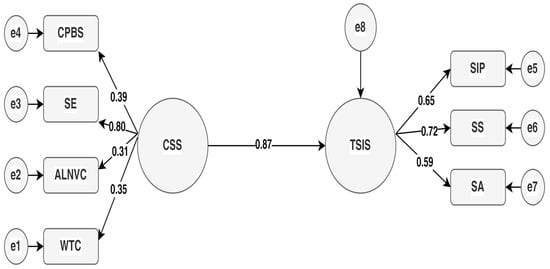

3.2. Findings Related to the Hypothesis of “Teacher Candidates’ Communication Skills Predict Their Social Intelligence Levels Positively and Significantly (H1)”

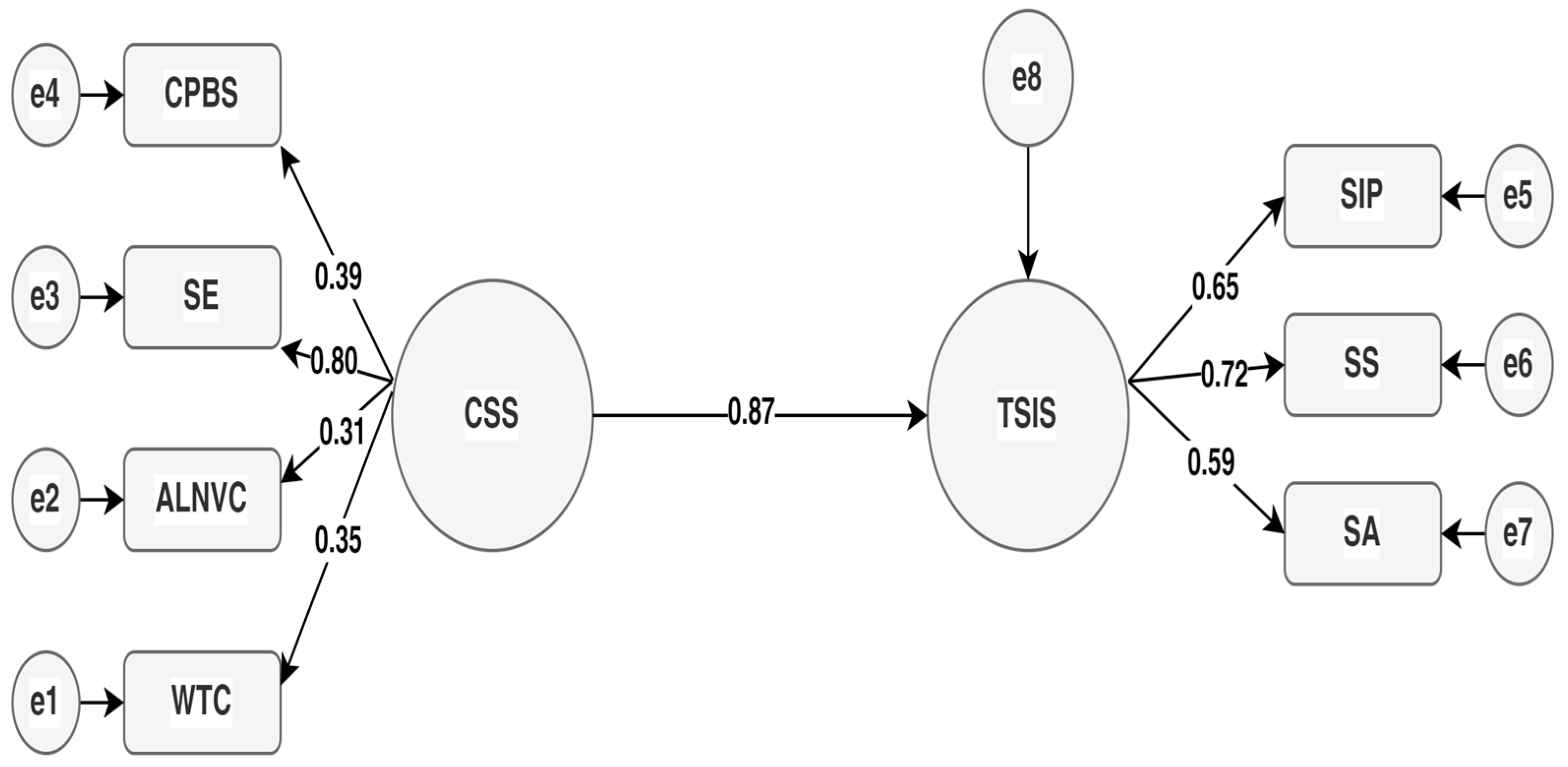

Structural equation model (SEM) was used to determine the research hypotheses and the mediation effect suggested by Baron and Kenny [69]. In this direction, path analysis model established for the hypothesis of “H1: Communication skills of teacher candidates predict their social intelligence levels positively and significantly.” is presented in Figure 2 (CPBS: Communication Principles and Basic Skills, SE: Self-Expression, ALNVC: Active Listening and Non-Verbal Communication, WTC: Willingness to Communicate, CSS: Communication Skills Scale; SIP: Social Information Process, SS: Social Skills, SA: Social Awareness, TSIS: Tromso Social Intelligence Scale).

Figure 2.

The Path Model Established for the H1 Hypothesis.

As shown in Figure 2, the communication skills of teacher candidates positively and significantly predict the level of social intelligence (β = 0.87; p < 0.001). In addition, the communication skills scale explains 76% of the total variance in the level of social intelligence. Figure 2 shows that the goodness of fit values of the path model established for the H1 hypothesis are in the appropriate value ranges of the established model (x2/sd = 2.784, CFI = 0.93, IFI = 0.94, NFI = 0.90, TLI = 0.89, RMSEA = 0.075, SRMR = 0.0446) [61,62,63]. These results mean that the H1 hypothesis of the study is accepted and the first condition of Baron and Kenny [69] (independent variable predicts dependent variable significantly) is met.

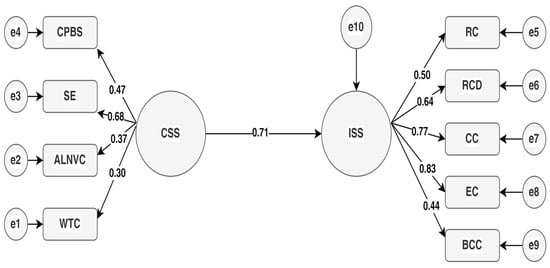

3.3. Findings Related to the Hypothesis of “Teachers Candidates’ Communication Skills Predict Intercultural Sensitivity Levels Positively and Significantly (H2)”

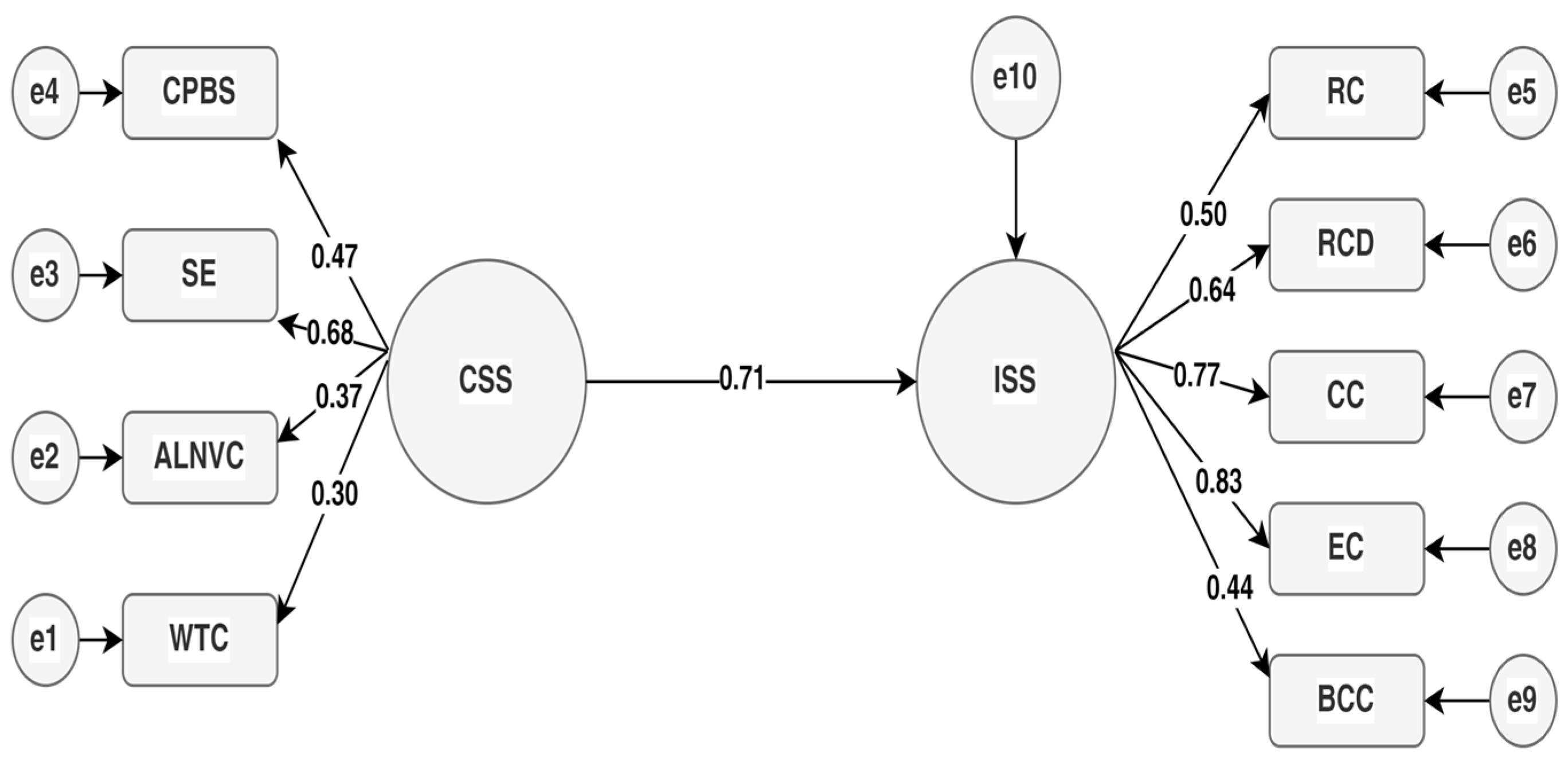

The path analysis model established for the hypothesis of “teacher candidates’ communication skills predict their intercultural sensitivity levels positively and significantly” is given in Figure 3 (CPBS: Communication Principles and Basic Skills, SE: Self-Expression, ALNVC: Active Listening and Non-Verbal Communication, WTC: Willingness to Communicate, CSS: Communication Skills Scale; RC: Responsibility in Communication, RCD: Respect for Cultural Diversity, CC: Confidence in Communication, EC: Enjoying Communication BCC: Being Careful in Communication, ISS: Intercultural Sensitivity Scale).

Figure 3.

The Path Model Established for the H2 Hypothesis.

As shown in Figure 3, communication skills of teacher candidates positively and significantly predict the level of intercultural sensitivity (β = 0.71; p < 0.001). In addition, the communication skills scale explains 50% of the total variance in the level of intercultural sensitivity. Figure 3 shows that the goodness fit values of the path model established for the H2 hypothesis are acceptable (x2/sd = 2.857, CFI = 0.92, IFI = 0.93, NFI = 0.89, TLI = 0.89, AGFI = 0.92, GFI = 0.96, RMSEA = 0.077, SRMR = 0.0518) [61,62,63]. According to these results, the H2 hypothesis of the research is accepted. Thus, Baron and Kenny’s [69] second condition (independent variable predicts mediator variable significantly) is also met.

3.4. Findings Related to the Hypothesis of “Teacher Candidates’ Intercultural Sensitivity Levels Predict Their Social Intelligence Levels Positively and Significantly (H3)”

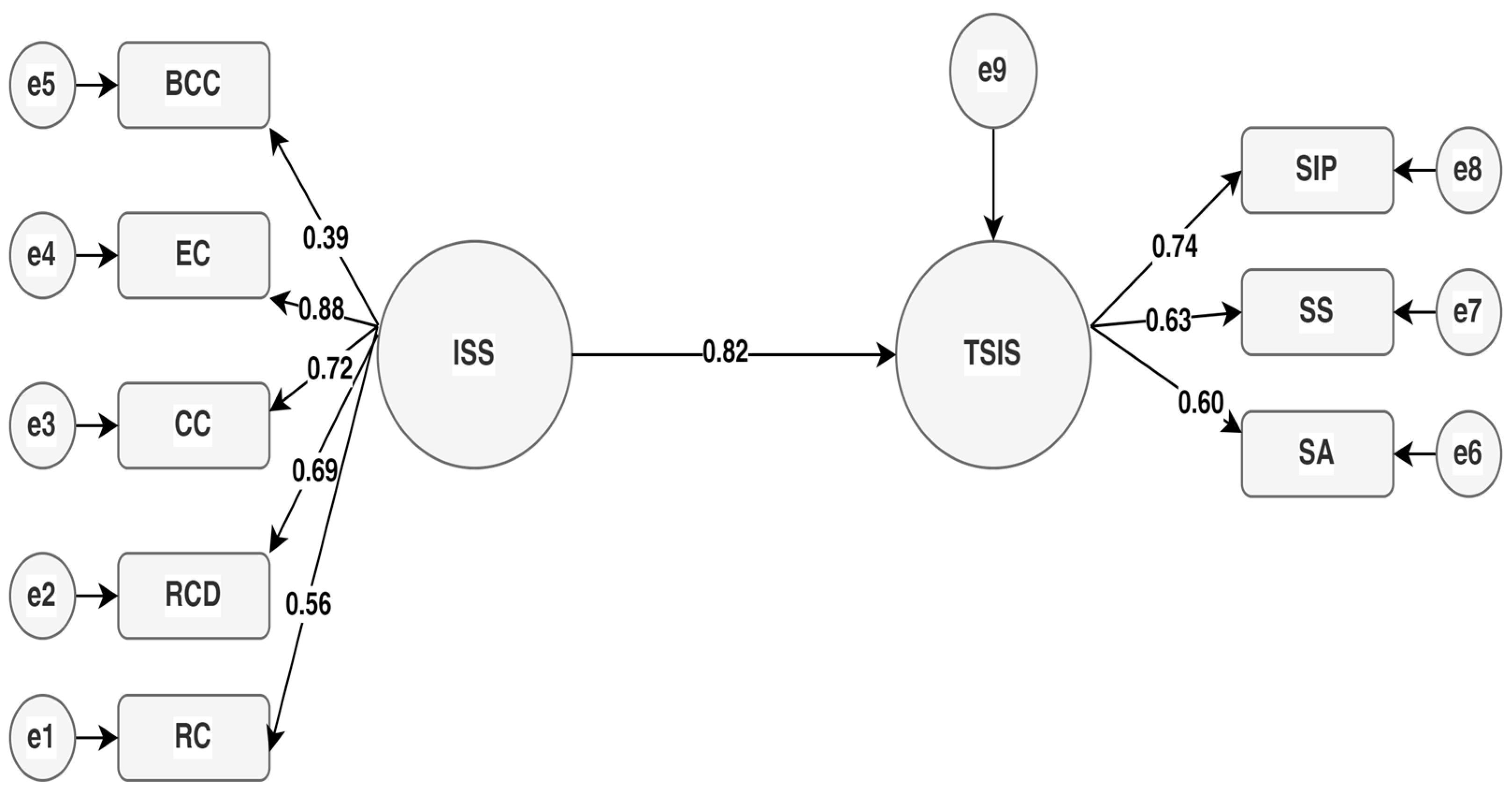

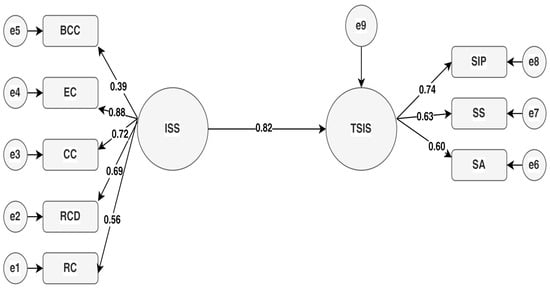

The path analysis model established for the hypothesis of “the level of intercultural sensitivity of teacher candidates predicts their social intelligence levels positively and significantly” is shown in Figure 4 (RC: Responsibility in Communication, RCD: Respect for Cultural Diversity, CC: Confidence in Communication, EC: Enjoying Communication BCC: Being Careful in Communication, ISS: Intercultural Sensitivity Scale; SIP: Social Information Process, SS: Social Skills, SA: Social Awareness, TSIS: Tromso Social Intelligence Scale).

Figure 4.

The Path Model Established for the H3 Hypothesis.

As shown in Figure 4, the intercultural sensitivity level of teacher candidates positively and significantly predicts the level of social intelligence (β = 0.82; p < 0.001). However, the intercultural sensitivity scale explains 68% of the total variance in the level of social intelligence. Figure 4 shows that the goodness fit values of the path model established for the H3 hypothesis are in the appropriate value ranges of the established model (x2/sd = 3.670, CFI = 0.95, IFI = 0.94, NFI = 0.93, TLI = 0.91, AGFI = 0.90, GFI = 0.95, RMSEA = 0.092, SRMR = 0.0499) [61,62,63]. Based on these results, the H3 hypothesis of the research is accepted. Therefore, the third condition of Baron and Kenny [69] (the mediating variable predicts the dependent variable significantly) is also met.

3.5. Findings Related to the Hypothesis of “Intercultural Sensitivity Level Has a Mediating Role in the Relationship between Communication Skills and Social Intelligence Levels of Teacher Candidates (H4)”

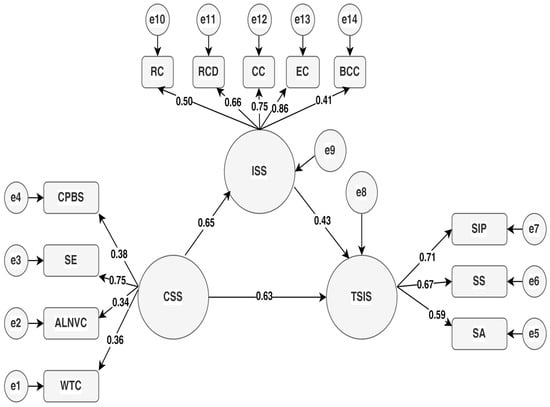

Since the first three conditions of Baron and Kenny [69] are met in order to determine the mediating role between the variables (see: Figure 2, Figure 3 and Figure 4), a model for the mediating role was created. For this reason, communication skills were included in the model as independent variables, intercultural sensitivity level as mediating variable, and social intelligence level as dependent variables. Figure 5 shows the path analysis established for the hypothesis of H4: “Intercultural sensitivity level has a mediating role in the relationship between teacher candidates’ communication skills and social intelligence levels” (CPBS: Communication Principles and Basic Skills, SE: Self-Expression, ALNVC: Active Listening and Non-Verbal Communication, WTC: Willingness to Communicate, CSS: Communication Skills Scale; RS: Responsibility in Communication, RCD: Respect for Cultural Diversity, CC: Confidence in Communication, EC: Enjoying Communication BCC: Being Careful in Communication, ISS: Intercultural Sensitivity Scale; SIP: Social Information Process, SS: Social Skills, SA: Social Awareness, TSIS: Tromso Social Intelligence Scale).

Figure 5.

The Path Model Established for the H4 Hypothesis.

As shown in Figure 5, the communication skills of the teacher candidates significantly predict the level of intercultural sensitivity (β = 0.65, p < 0.01) and social intelligence (β = 0.63, p < 0.01). Intercultural sensitivity was also found to be a significant predictor of social intelligence level (β = 0.43, p < 0.01). The fact that structural equation model established in Figure 5 have the necessary adaptive values (x2/sd = 3.422, CFI = 0.89, IFI = 0.89, NFI = 0.85, TLI = 0.85, AGFI = 0.87, GFI = 0.92, RMSEA = 0.087, SRMR = 0.0606) means that the model was validated [60,61,62]. The standardized path coefficients for the structural equation model established in Figure 5 are summarized in Table 2.

Table 2.

Standardized path coefficients for hypothesis H4.

As shown in Figure 5 and Table 2, in the relationship between communication skills and social intelligence level, even when the intercultural sensitivity level is added to the research model, the predictor of communication skills on social intelligence was again significant (β = 0.63, p < 0.01). However, 0.87 in the total predictive model (see: Figure 2) the standardized β value decreased to 0.63 with the inclusion of the intercultural sensitivity variable in the model (see: Figure 5 and Table 2). According to Baron and Kenny [69] when the mediating variable is added to the model together with the independent variable, the significant decrease in the predictive effect of the independent variable on the dependent variable is considered as a partial mediation effect. Accordingly, the H4 hypothesis is accepted and it was determined that the level of intercultural sensitivity had a “partial mediation” role in the relationship between the communication skills of teacher candidates and their social intelligence levels. In terms of indirect effect, communication skill significantly predicts social intelligence through intercultural sensitivity (β = 0.28, p < 0.01, 95% CI [0.032, 0.415]) and the fact that confidence interval does not include zero [69] shows that its mediating role is significant. On the other hand, the fact that the VAF (Variance Account For) value of the study was 0.32 [70], confirms the “partial mediation” role of intercultural sensitivity in the relationship between communication skills and social intelligence levels.

4. Conclusions, Discussion and Recommendations

In the context of sustainable education,, which aimed to determine the relationship between the communication skills of teacher candidates, and their level of intercultural sensitivity and social intelligence, it was determined that the communication skills of the teacher candidates is at a “high” level. This result suggests that the teacher candidates possess communication skills that meet the desired standards. In other words, it can be inferred that teacher candidates are proficient in conveying their thoughts clearly and purposefully to others, interacting effectively with various individuals, actively utilizing body language during speech, and expressing their emotions with ease. There are studies in the literature that are consistent with this result of the research. For instance, Korkut conducted a research [71] on Faculty of Education students, by Tepeköylü, Soytürk and Çamlıyar [72] on teacher candidates studying in the department of Physical Education and Sports, by Bingöl and Demir [73] Aşçı, Hazar and Yılmaz [74] on Health College students, by Pazar, Demiralp and Erer [75] on students of Faculty of Nursing.The study indicated that university students, including teacher candidates, generally exhibit high levels of communication skills.” Teacher candidates contribute to the development of society through a fairer and more sustainable education process [76,77,78] as well as being a citizen with communication skills that can lead the new challenges posed by society [79]. Teacher candidatescan should be supported and trained by the university as the guiding institution of their education to understand the importance of their role in sustainable education and to incorporate the ‘sustainability’ component into their future professional practice [80]. According to Seidel [81] high and desired level of communication skills of teachers affect the learning-teaching processes positively and are seen as the key to effective teaching. In this direction, the fact that teacher candidates’ communication skills are high in the research may provide positive contributions to the learning-teaching processes.

Another important result of the study is that the intercultural sensitivity levels of teacher candidates is “high”. This result may be an indication that teacher candidates respecting different cultures, communicating with people from different cultures, seeing all cultures as equal and do not approach any culture with prejudice. The high level of intercultural sensitivity of teacher candidates can be explained by the inclusiveness of the environments they live in and the cultural values they acquire from their families. Indeed, similar studies in the literature [82,83,84,85,86,87,88,89] the reason for the high level of sensitivity is explained by emphasizing social and cultural variables. Therefore, the level of intercultural sensitivity varies depending on social and cultural variables. It is important for the future of sustainable education that teacher candidates are sensitive to intercultural dialogue and understanding and understand the people with different backgrounds represented in their classrooms [90]. In this context, it is among the duties of universities to contribute to sustainable educational activities to promote new ways of intercultural dialogue and mutual understanding [91].

In the study, it was determined that the social intelligence levels of the teacher candidates is also at a “high” level. The high level of social intelligence in the study may be a proof that teacher candidates easily adapt to social environments and establish good relations with people they have just met. The existence of various studies in the literature [66,92,93,94] that are consistent with this result of the research supports this conclusion. However, the high level of social intelligence of teacher candidates can also be explained by the fact that they are constantly in an interactive social environment and frequently participate in social activities. Because social intelligence consist of the individual’s communication skills in the social environment and the behaviors that occur in a certain social environment [95]. In other words, it can be claimed that individuals with high social skills and social aspects may naturally have a high level of social intelligence.

The results of the correlation analysis revealed positive and significant relationships between teacher candidates’ communication skills and their levels of intercultural sensitivity and social intelligence. In summary, the findings suggest that as teacher candidates’ communication skills improve, their intercultural sensitivity and social intelligence also tend to increase. This indicates that enhanced communication abilities may contribute to heightened awareness of cultural diversity and an improved capacity to navigate social interactions effectively. It is reported in the literature that there are positive and significant relationships between communication skills and social intelligence level [96,97], and between communication skills and intercultural sensitivity [98,99]. On the other hand, it is stated in the literature that intercultural sensitivity, as a type of intelligence, has a positive and significant relationship with cultural intelligence [100,101,102] and someone with high social skills also has a high level of social intelligence [103]. In this context, the richness and diversity of social life may have paved the way for meaningful relationships between communication skills, intercultural sensitivity and social intelligence levels of individuals. In the current study, it is estimated that the richness and diversity of social life increases the level of communication skills, intercultural sensitivity and social intelligence in teacher candidates. The research conducted by Yermentaeyeva [104] shows that the development of communicative competence of teacher candidates in the context of university education is significantly related to social intelligence. In this context, universities are expected to provide teacher candidates with a much richer sustainable education for exploratory social intelligence [105].

Another important result of the research is that teacher candidates’ communication skills is a significant predictor of social intelligence level and intercultural sensitivity; and intercultural sensitivity is also a significant predictor of social intelligence level. In the literature, there are studies showing that the communication skills significantly predicts social intelligence level [96,97,106] and intercultural sensitivity [52] and intercultural sensitivity significantly predicts cultural intelligence as an extension of social intelligence [107,108,109]. Also, according to Willmann, Feldt, and Amelang [110] communication skill among individuals is seen as a social intelligence skill in terms of ensuring harmony and balance in interpersonal relations. Social intelligence, on the other hand, means the individual’s ability to understand himself and others, and communicate [111]. For this reason, it is inevitable for individuals with high communication skills to have a more developed social intelligence as they can express themselves better. At the same time, since the communication skill is the common symbol shared by the members of a society and culture, it can be said that it is the main tool for getting along with individuals from different cultures. Because communication skills are necessary for intercultural sensitivity, and cultural sensitivity is necessary for social intelligence [112]. It is thought that this necessity enables individuals who have positive attitudes towards different cultures to express themselves better in their communications and to cope better with daily events. From the perspective of this study, universities’ development of sustainable education to train teacher candidates who respect intercultural sensitivity, have high communication skills, and have developed social intelligence contributes to raising responsible and conscious students [113,114,115].

As a result of the path analysis conducted in the research, it was determined that the level of intercultural sensitivity has a “partial mediation” role in the relationship between the communication skills and social intelligence levels of teacher candidates. Accordingly, it can be said that the communication skills of the teacher candidates are effective on the level of social intelligence through intercultural sensitivity. In other words, it is understood that the effect of teacher candidates’ communication skills on social intelligence is partially provided by intercultural sensitivity. Some researchers [116,117,118] point out the importance of intercultural sensitivity by drawing attention to the possible effects of cultural variables and conditions. In the literature, it is stated that the level of intercultural sensitivity of individuals who encounter different cultures is higher than other individuals’ and they are more successful in overcoming many problems [52,63,119]. In this context, it can be seen as an expected result that the social intelligence levels of individuals, who can exchange ideas with other people, strengthen their interaction and connect people to each other, are high. The fact that teacher candidates’ social intelligence levels were predicted by intercultural sensitivity and communication skills also supports this conclusion in the study.

While evaluating the results of the study, some limitations should be taken into account. First of all, it should be known that the sample of the research was carried out in a single university on teacher candidates and only with a relatively small group of participants. On the other hand, the fact that the results obtained in the research are not supported by qualitative data that will enable a full understanding of the underlying reasons can be seen as another limitation.

Based on findings of this research, several recommendations can be made for both practitioners and researchers. For example: contents that develops communication skills and intercultural sensitivity of teacher candidates can be included in the education and curriculum programs for practitioners. In this way, the factors that hinder communication skills can be identified, and solutions and awareness activities can be developed to eliminate them. In addition, by focusing on student exchange programs such as Erasmus, Farabi and Mevlana, which aim to improve teacher candidates’ communication skills, intercultural sensitivity and social intelligence levels, it can be ensured that teacher candidates get to know different cultures. In addition to these, social activities in which each of the teacher candidates can participate can be emphasized. And for researchers, it can be suggested that the current research can be reproduced with comparative analyzes at foundation universities and with a wider participation, examined thoroughly with qualitative or mixed methods, and the mediator or moderator role of other variables in the relationship between communication skills and social intelligence can be analyzed. Also, it is thought that it would be useful to test the relationships between variables in the study with multilevel regression models.

Author Contributions

M.Ö.: Literature review, writing the introduction, collection of data, following the publication process, M.N.Ç.: Discussion of the findings obtained, writing the results. M.S.Ç.: Data analysis, methodology, organization of findings. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

For this study, approval was obtained from the Social and Human Sciences Scientific Research and Publication Ethics Committee of Kütahya Dumlupınar University, a public university in Türkiye, on 14 February 2022 with the number 2022/02.

Informed Consent Statement

The researchers requested and received the consent of the participants regarding their participation in the study.

Data Availability Statement

The corresponding author can be contacted to request access to the data supporting the findings of this study.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- World Migration Report 2022, International Organization for Migration. Available online: https://publications.iom.int/books/world-migration-report-2022 (accessed on 8 October 2022).

- Strohmeier, D.; Spiel, C. Immigrant children in Austria: Aggressive behavior and friendship patterns in multicultural school classes. J. Appl. Sch. Psychol. 2003, 19, 99–116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- UNESCO. Education for Sustainable Development 2016. UN Decade of ESD. Available online: http://en.unesco.org/themes/education-sustainable-development/what-is-esd/un-decade-of-esd (accessed on 15 November 2022).

- Polat, M. Is inclusive education possible? Analyzing the views of pre-service teachers who took the inclusive education course with the vignette technique. Van. Yüz. Yıl. Üni. Eğit. Fak. Der. 2022, 19, 965–986. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Şimşek, H.; Dağıstan, A.; Şahin, C.; Koçyiğit, E.; Dağıstan Yalçınkaya, G.; Kart, M.; Dağdelen, S. Traces of multiculturalism in basic education programs in Türkiye in the context of inclusive education. Ahi. Ev. Üni. Sos. Bil. Ens. Der. 2019, 5, 177–197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Çelik, R. Justice, inclusion and equitable equal opportunities in education. Fe. Der. 2017, 9, 17–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Özdemir, O. A new perspective on environmental education: Education for sustainable development. Eği. Ve. Bil. 2007, 32, 23–39. [Google Scholar]

- Şengöz, E.; Soydan, S.B.; Saltalı, N.D. Critical multicultural education self-efficacy as a predictor of basic education teachers’ inclusive education self-efficacy. J. Acad. Soc. Sci. 2022, 127, 244–265. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Banks, J.A. Multicultural education: Characteristics and goals. In Multicultural Education: Issues and Perspectives, 9th ed.; Banks, J.A., Banks, C.A.M., Eds.; John Wiley & Sons: New York, NY, USA, 2015; pp. 2–23. [Google Scholar]

- Sorkos, G.; Hajisoteriou, C. Sustainable intercultural and inclusive education: Teachers’ efforts on promoting a combining paradigm. Ped. Cul. Soc. 2020, 29, 1–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hammer, M.R.; Bennett, M.J.; Wiseman, R. Measuring intercultural sensitivity: The intercultural development inventory. Int. J. Intercult. Rel. 2003, 27, 421–443. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bölükbaşı, A. Examining pre-service teachers’ intercultural sensitivity in terms of empathic disposition, subjective well-being and socio-demographic variables. Mer. Üni. Eği. Fak. Der. 2020, 16, 44–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ünlü, İ.; Örten, H. Examining pre-service teachers’ perceptions of multiculturalism and multicultural education. Dic. Üni. Ziy. Gök. Eği. Fak. Der. 2013, 21, 287–302. [Google Scholar]

- Gay, G. Acting on beliefs in teacher education for cultural diversity. J. Teach. Educ. 2010, 61, 143–152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ruan, J. Using the ABCs to support intercultural understanding. In Getting to Know Ourselves and Others: A Less Travelled Path to Intercultural Understanding; Literacy, Language and Learning Series; Finkbeiner, C., Lazar, A.M., Schmidt, P., Eds.; Information Age Publishing: Charlotte, NC, USA, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Akman, Y.; İmamoğlu Akman, G. Examining teachers’ multicultural education attitudes according to their perception of social intelligence. Sak. Uni. J. Edu. 2017, 7, 34–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goleman, D. Sosyal Zekâ: İnsan Ilişkilerinin Yeni Bilimi; Deniztekin, O.Ç., Translator; Varlık Yayınları: İstanbul, Turkey, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Kozikoğlu, İ.; Yıldırımoğlu, S. The relationship between teachers’ attitudes towards multicultural education and classroom practices in inclusive education. Dok. Eyl. Üni. Buc. Eğit. Fak. Der. 2021, 51, 226–244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akcay, K.; Altinay, F.; Altınay, Z.; Daglı, G.; Shadiev, R.; Altinay, M.; Adedoyin, O.B.; Okur, Z.G. Global citizenship for the students of higher education in the realization of sustainable development goals. Sustainability 2024, 16, 1604. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Çiftçi, S.; Taskaya, S.M. The relationship between self-efficacy and communication skills of prospective primary school teachers. Edu. Sci. 2010, 5, 921–928. [Google Scholar]

- Bulut, R.C. The Relationship Between Communication Skills and Organizational Cynicism Levels of Secondary School Teachers. Master’s Thesis, İstanbul Sabahattin Zaim Üniversitesi, İstanbul, Turkey, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Özgökman, Ş. Examining The Relationship Between Communication Skills and Empathic Tendencies of Preservice Preschool Teachers (Afyonkarahisar Province Sample). Master’s Thesis, Afyon Kocatepe Üniversitesi, Afyon, Turkey, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Can, F.; Bozgün, K. The relationship between communication skills and speaking anxiety of education faculty students. Ulus. Türk. Ede. Kül. Eği. Der. 2021, 10, 1124–1136. [Google Scholar]

- Gülbahar, B.; Sıvacı, S.Y. Examining the relationship between pre-service teachers’ communication skills and their perceptions of classroom management efficacy. Va. Yüz. Yı. Üni. Eği. Fak. Der. 2018, 15, 268–301. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Polat, S.; Rengi, Ö. Classroom teachers’ perceptions of cultural differences and intercultural sensitivity. Zeit. Fü. Di. Wel. De. Tür. J. Wor.Tur. 2014, 6, 135–156. [Google Scholar]

- Çetin, M.; Kartal Baş, M. Examining the effect of intercultural sensitivity acquisition on student leadership in pre-service teachers. Güm.Üni. Sos. Bil. Der. 2022, 13, 48–62. [Google Scholar]

- Demir, S.; Üstün, E. Investigation of pre-service teachers’ intercultural sensitivity and ethnocentrism levels in terms of various variables. Va. Yüz.Yı. Üni. Eği. Fak. Der. 2017, 14, 182–204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karagüven, M.H.Ü.; Hülya, M. Empathy and social intelligence. Int. J. Soc. Sci. 2015, 34, 187–197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ünver, N.; Semiz, S. The effect of the practices within the scope of the drama course in the preschool teaching undergraduate program on the social intelligence areas of pre-service teachers. Kast. Eği. Der. 2016, 24, 2585–2594. [Google Scholar]

- Gönenç, E.Ö. Historical process of communication. İst. Üni. İlet.Fak. Der. 2007, 28, 87–102. [Google Scholar]

- Koçyiğit, M. Effective Communication and Emotional Intelligence, 3rd ed.; Eğitim Yayınevi: Konya, Turkey, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Cüceloğlu, D. Human to Human Again; Remzi Kitabevi: İstanbul, Turkey, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Lasswell, H.D. The structure and function of communication in society. J. Commun. Res. 2007, 24, 215–228. [Google Scholar]

- TDK. Türk Dil Kurumu. 2022. Available online: https://sozluk.gov.tr/ retrieved from (accessed on 15 October 2022).

- Işık, M. Introduction to Communication Science, 2nd ed.; Eğitim Yayınevi: Konya, Turkey, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Lynn, E.M. In-service teacher education in classroom communication. Commun. Educ. 2009, 26, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tezel, Ş.; Kandır, A.; Can-Yaşar, M.; Yazıcı, E. Investigation of preschool teachers’ communication skills in terms of some variables. Int. Ref. Aca. Soc. Sci. J. 2012, 3, 95–108. [Google Scholar]

- Gökçe, E. Competencies of primary classroom teachers. Çağ. Eği. 2003, 299, 36–48. [Google Scholar]

- Şen, H.S.; Erişen, Y. Effective teaching characteristics of lecturers in teacher training institutions. Gaz. Üni. Gaz. Eği. Fak. Der. 2002, 22, 99–116. [Google Scholar]

- Aksungur, G. Examining Turkish Teachers’ Perceptions Of Effective Communication Skills in the Classroom. Master’s Thesis, Ahi Evran Üniversitesi, Kırşehir, Turkey, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Öğüt, N.; Olkun, E.O. Intercultural sensitivity level of university students: The case of Selcuk University. Sel. İlet. 2018, 11, 54–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, G. The impact of intercultural sensitivity on ethnocentrism and intercultural communication apprehension. Intercult. Commun. Educ. 2010, 19, 1–9. [Google Scholar]

- Bhawuk, D.; Brislin, D. The Measurement of Intercultural Sensitivity Using The Concepts of Individualism and Collectivism. Int. J. Intercult. Rel. 1992, 16, 413–436. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matkin, G.; Barbuto, J. Demographic similarity/difference, intercultural sensitivity, and leader–member exchange: A Multilevel Analysis. J. Leadersh. Org. Stud. 2012, 19, 294–302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Johnson, L.S. The diversity imperative: Building a culturally responsive school ethos. Intercult. Educ. 2003, 14, 17–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cırık, İ. Multicultural education and its reflections. Hacet. Eği. Fak. Der. 2008, 34, 27–40. [Google Scholar]

- Kengwee, J. Fostering cross cultural competence in preservice teachers through multicultural education experiences. Early Child. Educ. 2010, 38, 197–204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Renner, T.; Feldman, R.S. The Mind of My Mind Psychology. Durak, M.; Durak, E.Ş.; Kocatepe, U., Translators; Nobel Akademik Yayıncılık: Ankara, Turkey, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Aman, D.; Verma, E. Metacognition among secondary school students in relation to social intelligence, gender, type of family and locale. G. J. Si. Thou. 2015, 2, 11–16. [Google Scholar]

- Doğan, T.; Çetin, B. Factor structure, validity and reliability study of the Turkish version of the Tromso Social Intelligence Scale. Kur. Uyg. Eği. Bil. 2009, 9, 691–720. [Google Scholar]

- Özcan, M. Investigation of pre-service teachers’ social intelligence levels. Eğit. Ye. Yak. Der. 2018, 1, 42–51. [Google Scholar]

- Bekiroğlu, O.; Balcı, Ş. Searching for traces of intercultural communication sensitivity: A study in the case of communication faculty students. Tür. Araş. Der. 2014, 35, 429–460. [Google Scholar]

- Onur Sezer, G.; Bağçeli Kahraman, P. The relationship between classroom and pre-service preschool teachers’ attitudes towards multicultural education and intercultural sensitivity: The case of Uludag University. Mer. Üni. Eği. Fak. Der. 2017, 13, 550–560. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kazu, E.; Düşükcan, M. The effect of nursing students’ social intelligence levels on their communication skills. Fır. Üni. Sos. Bil. Der. 2021, 31, 215–230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Başoğlu, C.İ. Sosyal Zekânın Girişimcilik Eğilimine Etkisinde Kültürel Zekânın Aracı. Master’s Thesis, Kastamonu Üniversitesi, Kastamonu, Turkey, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Fraenkel, J.R.; Wallen, N. Eç How to Design and Evaluate Research in Education, 6th ed.; McGraw-Hill: New York, NY, USA, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Neuman, W.L.; Robson, K. Basics of Social Research; Pearson Canada: Toronto, ON, Canada, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Cohen, L.; Manion, L.; Morrison, K. Research Methods in Education; Routledge: London, UK, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Korkut Owen, F.; Bugay, A. Development of communication skills scale: Validity and reliability study. Mer. Üni. Eği. Fak. Der. 2014, 10, 51–64. [Google Scholar]

- Byrne, B.M. Structural Equation Modeling with AMOS; Routledge: New York, NY, USA, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Kline, R.B. Principles and Practice of Structural Equation Modeling; The Guilford Press: New York, NY, USA, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Schumacker, R.E.; Lomax, R. GA Beginner’s Guide to Structural Equation Modeling, 2nd ed.; Psychology Press: New York, NY, USA, 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, G.M.; Starosta, W.J. The development and validation of the intercultural sensitivity scale. Hum. Commun. 2000, 3, 1–22. [Google Scholar]

- Bulduk, S.; Tosun, H.; Ardıç, E. Measurement properties of Turkish intercultural sensitivity scale in nursing students. Tür. Klin. J. Med. Eth. La. His. 2011, 19, 25–31. [Google Scholar]

- Silvera, D.H.; Martinussen, M.; Dahl, T.I. The trom sosocial intelligence scale, a self-reportmeasure of social intelligence. Scand. J. Psychol. 2001, 42, 313–319. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tabachnick, B.G.; Fidell, L.S. Using Multivariate Statistic; Pearson: Boston, MA, USA, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Green, S.B.; Salkind, N.J. Using SPSS for Windows and Macintosh: Analyzing and Understanding Data, 5th ed.; Pearson Education, Inc.: Upper Saddle River, NJ, USA, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Preacher, K.J.; Hayes, A.F. Asymptotic and resampling strategies for assessing and comparing indirect effects in multiple mediator models. Behav. Res. Methods 2008, 40, 879–891. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baron, R.M.; Kenny, D.A. The moderator-mediator variable distinction in social psychological research: Conceptual, strategic and statistical considerations. J. Pers. Soc. Psychol. 1986, 51, 1173–1182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hair, J.F., Jr.; Hult, G.T.M.; Ringle, C.; Sarstedt, M. A Primer on Partial Least Squares Structural Equation Modeling (PLS-SEM); Sage Publications: New York, NY, USA, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Korkut, F. Evaluation of Communication Skills of University Students; IV. In Proceedings of the National Congress of Educational Sciences; Anadolu Üniversitesi: Eskişehir, Turkey, 1997; pp. 208–218. [Google Scholar]

- Tepeköylü, Ö.; Soytürk, M.; Çamlıyer, H. Investigation of Physical Education and Sports School (PEHS) students’ perceptions of communication skills in terms of some variables. Spo. Bed. Eği. Sp. Bil. Der. 2009, 7, 115–124. [Google Scholar]

- Bingöl, G.; Demir, A. Communication skills of Amasya health college students. Göz. Tı. Der. 2011, 26, 152–159. [Google Scholar]

- Aşçı, Ö.; Hazar, G.; Yılmaz, M. Communication skills of school of health students and related variables. Acıba. Üni. Sağ. Bil. Der. 2015, 6, 160–165. [Google Scholar]

- Pazar, B.; Demiralp, M.; Erer, İ. The communication skills and the empathic tendency levels of nursing students: A cross-sectional study. Cont. Nur. 2017, 53, 368–377. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Álvarez, O.; García, L.Á.; Salvà, F.; Calvo, A. Variables influencing preservice teacher training in education for sustainable development: A case study of two Spanish universities. Sustainability 2019, 11, 4412. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Solís, C.; Ruiz, J.; Limón, D.; Valderrama, R. Sustainability in the University: A study of its presence in curricula, teachers and students of education. Sustainability 2019, 11, 6620. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muñoz, J.M.; Sánchez, F.; Barrón, Á.; Serrate, S. Are we training in sustainability in higher education? Case study: Education degrees at the University of Salamanca. Sustainability 2020, 12, 4421. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Merritt, E.; Hale, A.; Archambault, L. Changes in pre-service teachersí values, sense of agency, motivation and consumption practices: A case study of an education for sustainability course. Sustainability 2019, 11, 155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vásquez, C.; Seckel, M.J.; Alsina, Á. Belief system of future teachers on Education for Sustainable Development in math classes. Uniciencia 2020, 34, 1–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seidel, T. Klassenführung. In Paedagogische Psychologie; Wild, E., Möller, J., Eds.; Springer Verlag: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Banos, R.V. Intercultural Sensitivity of Teenagers: A study of Educational Necessities in Catalonia. Intercult. Commun. Educ. 2006, 15, 16–22. [Google Scholar]

- Bayles, P.P. Assesing The Intercultural Sensitivity of Elementary Teachers in Bilingual Schools in Texas School District. Ph.D. Thesis, University of Minnesota, Minneapolis, MN, USA, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Demir, A.; Demir, S. Evaluation of Erasmus program in terms of intercultural dialogue and interaction: A qualitative study with pre-service teachers. Ulus. Sos.Araş. Der. 2009, 2, 95–105. [Google Scholar]

- Fretheim, A.M. Assesing the Intercultural Sensitivity of Educators in an American International School. Ph.D. Thesis, University of Minnesota, Minneapolis, MN, USA, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Penbek, S.; Yurdakul, D.; Guldem Cerit, A. Intercultural Communication Competence: A Study About the Intercultural Sensitivity of University Students Based on Their Education and International Experiences. In Proceedings of the European and Mediterranean Conference on Information Systems, Izmir, Turkey, 13–14 June 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Rengi, Ö. Sinif Öğretmenlerinin Kültürel Farklilik Algilari Ve Kültürlerarasi Duyarlılıkları. Master’s Thesis, Kocaeli Üniversitesi, Kocaeli, Turkey, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Talib, M.; Sari, H. Pre-Service Teachers’ Intercultural Competence in Japan and Finland: A Comparative Study of Finnish and Japanese University Students—A Preliminary Study. Changing Educational Landscapes; Springer: Dordrecht, The Netherlands, 2010; pp. 241–260. [Google Scholar]

- Westrick, J.M.; Yuen, C.Y. The intercultural sensitivity of secondary teachers in Hong Kong: A comparative study with ımplications for professional development. Intercult. Educ. 2007, 18, 129–145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garrido, M.C.D.; Ruiz-Cabezas, A.; Domínguez, M.C.M.; Dueñas, M.C.L.; Pérez Navío, E.; Rivilla, A.M. Teachers’ training in the intercultural dialogue and understanding: Focusing on the education for a sustainable development. Sustainability 2020, 12, 9934. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Levitt, H.M.; Bamberg, M.; Creswell, J.W.; Frost, D.M.; Josselson, R.; Suárez-Orozco, C. Journal article reporting standards for qualitative primary, qualitative meta-analytic, and mixed methods research in psychology: The APA Publications and Communications Board task force report. Am. Psychol. 2018, 73, 26–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ermiş, E.; İmamoğlu, O.; Erilli, N.A. The effect of sports on university students’ physical and social multiple intelligence scores. Sp. Perf. Araş. Der. 2012, 3, 23–29. [Google Scholar]

- Milli, M.S.; Yağcı, U. Investigation of pre-service teachers’ communication skills. Aba. İz. Bay. Üni. Eği. Fak. Der. 2017, 17, 286–298. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saracoğlu, A.S.; Yenice, N.; Karasakaloğlu, N. The relationship between pre-service teachers’ communication and problem solving skills and their reading interests and habits. Yüz. Yı. Üni. Eği. Fak. Der. 2009, 6, 187–206. [Google Scholar]

- Ford, M.E.; Tisak, M.S. A further search for social intelligence. J. Educ. Psychol. 1983, 75, 196–206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arıbaş, B.B. Investigating The Relationship Between Social Intelligence Levels and Communication Skills of Pre-Service Social Studies Teachers. Master’s Thesis, Uşak Üniversitesi, Uşak, Turkey, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Kaya, N.; Turan, N.; Kamberova, H.A.; Cenal, Y.; Kahraman, A.; Evren, M. Communication skills and social intelligence levels of nursing students according to art characteristics. Hemş. Eği. Araş. Der. 2016, 13, 50–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Çetinkaya, Ö.; Alparslan, A.M. The effect of emotional intelligence on communication skills: A study on university students. Sül. Deml. Üni. İkt. İd. Bil. Fak. Der. 2011, 16, 363–377. [Google Scholar]

- Oyur, E.; Mercan, N.; Saylan, O.; Buran, A.Ç. A study on expressing emotions and communication skills in the work environment. Org.Yön. Bil. Der. 2012, 4, 1309–8039. [Google Scholar]

- Abaslı, K.; Polat, Ş. Examining students’ views on intercultural sensitivity and cultural intelligence. Ane. Mu. Alp. Üniv. Sos.Bil. Der. 2019, 7, 193–202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mercan, N. A study on the relationship between cultural intelligence and intercultural sensitivity in multicultural settings. Öm. Halis. Üni. İkt. İd. Bil. Fak. Der. 2016, 9, 1–13. [Google Scholar]

- Özdemir, K. The Impact of Cultural Intelligence on Intercultural Sensitivity. Master’s Thesis, Hasan Kalyoncu Üniversitesi, Gaziantep, Turkey, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Doğan, T. Examining The Relationship Between Social Intelligence Levels of University Students and Depression and Some Variables. Master’s Thesis, Sakarya Üniversitesi, Sakarya, Turkey, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Yermentaeyeva, A.; Aurenova, M.D.; Uaidullakyzy, E.; Ayapbergenova, A.; Muldabekova, K. Social intelligence as a condition for the development of communicative competence of the future teachers. Procedia Soc. Behav. Sci. 2014, 116, 4758–4763. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Iqbal, Q.; Piwowar-Sulej, K. Sustainable leadership in higher education institutions: Social innovation as a mechanism. Int. J. Sust. Higher Edu. 2021, 23, 1–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gül, E. The Relationship Between Emotional Intelligence and Communication Skills: An Application. Master’s Thesis, Beykent Üniversitesi, İstanbul, Turkey, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Gezer, M.; Şahin, İ. Investigating the relationship between attitude towards multicultural education and cultural intelligence with SEM. Do. Coğ. Der. 2017, 22, 173–188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- İlhan, M.; Çetin, B. Validity and reliability study of Turkish version of cultural intelligence scale. Hacet. Üni. Eği. Fak. Der. 2014, 29, 94–114. [Google Scholar]

- Koçak, S.; Özdemir, M. The role of cultural intelligence in pre-service teachers’ attitudes towards multicultural education. İlkö. Onl. 2015, 14, 1352–1369. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Willmann, E.; Feldt, K.; Amelang, M. Prototypical behavior pattern of social intelligence. Anintercultural comparison between Chinese and German subjects. Int. J. Psychol. 1997, 32, 329–346. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bar-On, R.; Handley, R. The Bar-On EQ-360: Technical manual; Multi-HealthSystems: Toronto, ON, Canada, 2003. [Google Scholar]

- James, M. Interculturalism: Theory and Policy; The Baring Foundation: London, UK, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Abduganiev, O.I.; Abdurakhmanov, G.Z. Ecological education for the purposes sustainable development. Am. J. Soc. Sci. Educ. Innov. 2020, 2, 280–284. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, K.W. Learning management knowledge: Integrating learning cycle theory and knowledge types perspective. Acad. Manag. Learn. Edu. 2020, 19, 192–222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Strachan, G. Can education for sustainable development change entrepreneurship education to deliver a sustainable future? Dis. Com. Sust. Edu. 2018, 9, 36–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Crowne, K.A. The relationships among Social Intelligence, Emotional Intelligence and Cultural Intelligence. Organ. Manag. J. 2009, 6, 148–163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eisenberg, J.; Lee, H.J.; Brück, F.; Brenner, B.; Claes, M.T.; Mironski, J.; Bell, R. Can business schools make students culturally competent? Effects of cross-cultural management courses on cultural ıntelligence. Acad. Manag. Learn. Edu. 2013, 12, 603–621. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jyoti, J.; Kour, S. Assessing the Cultural Intelligence and Task Performance Equation: Mediating Role of Cultural Adjustment. Cross. Cult. Manag. 2015, 22, 236–258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Terry, J. New techniques for trainging and motivating yoru compnay’s multicultural management team. Employ. Relat. Today 2007, 34, 37–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).