Factors Influencing Consumer Upcycling Behavior—A Study Based on an Integrated Model of the Theory of Planned Behavior and the Technology Acceptance Model

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Research Model and Hypotheses

2.1. Theoretical Framework

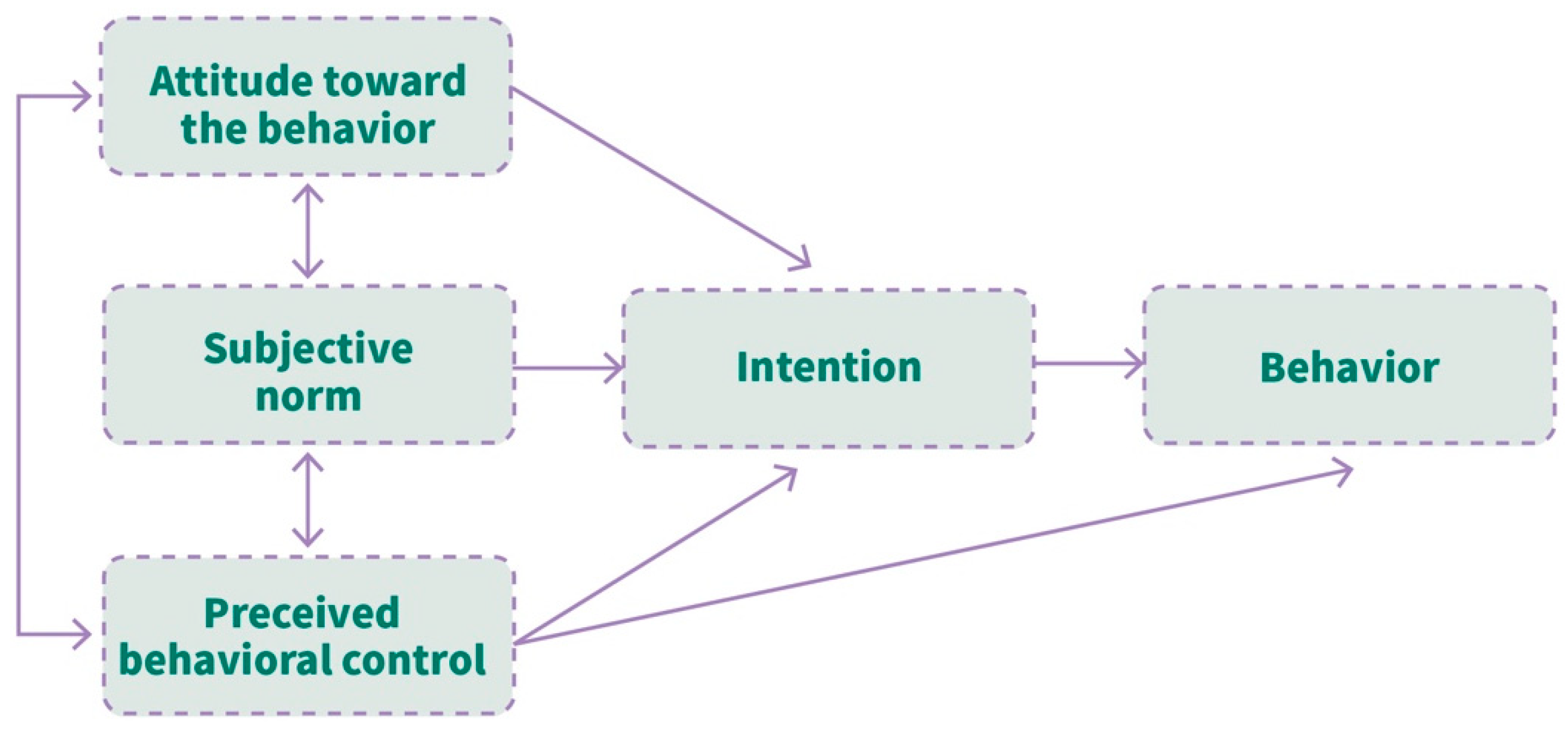

2.1.1. Theory of Planned Behavior

- Attitude: Attitude pertains to an individual’s personal evaluation of the attractiveness or unattractiveness of participating in a specific conduct. Positive attitudes are likely to encourage behavior, while negative attitudes can deter it.

- Subjective Norm: Social pressure refers to the influence exerted by important individuals such as family and friends, which can either encourage or discourage the performance of a specific action.

- Perceived Behavioral Control: It is the subjective evaluation of the ease or difficulty of executing a specific behavior by an individual. It considers both internal factors, such as emotional regulation, experiences, and abilities, and external factors, such as information, opportunities, and resources.

- Intention: It pertains to an individual’s level of determination and motivation to carry out a certain conduct, as demonstrated by their specific plans and actions.

- Behavior: The actual action taken, which is largely determined by behavioral intention but also directly influenced by perceived behavioral control, leading to possible inconsistencies between intention and behavior.

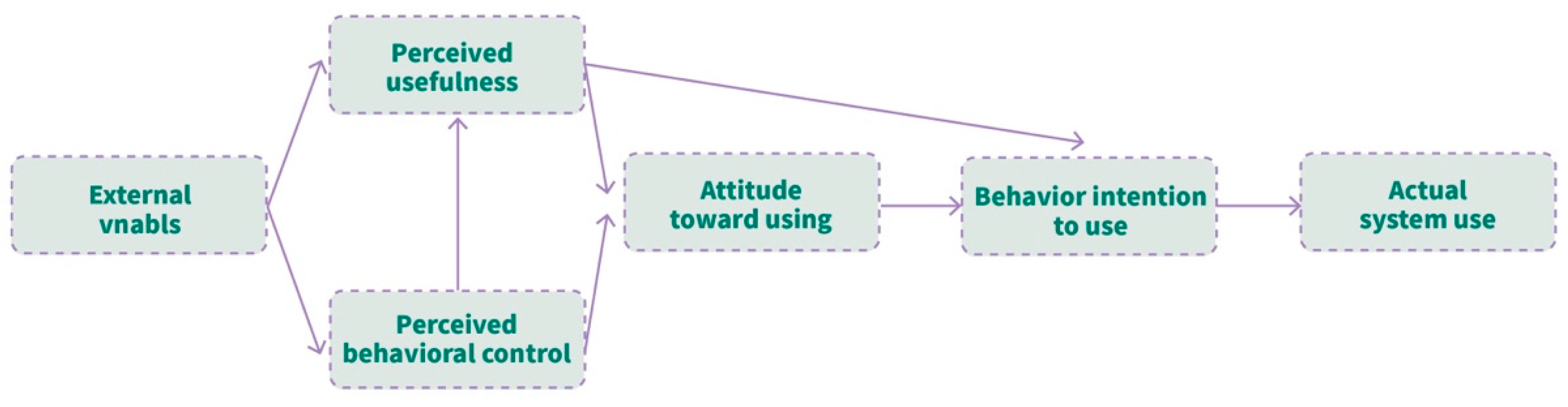

2.1.2. Technology Acceptance Model

- Perceived usefulness: The degree to which a person thinks that using a certain technology would enhance their productivity, efficiency, or ability to finish tasks. It highlights the practical benefits of the technology for achieving personal goals.

- Perceived ease of use: Usability refers to the extent to which a user considers a technology as being user-friendly. Increased perceived ease of use results in a more favorable attitude towards the technology.

- Attitude toward using: User’s overall appraisal of a specific technology, including both positive and negative emotions derived from their evaluations of the technology’s utility and user-friendliness.

- Subjective norms: The perceived social pressure to use a specific technology, influenced by the expectations of colleagues, family, friends, or other social groups.

- Behavioral intention: The individual’s intention to adopt a particular technology, indicating their plans to use it in the future and serving as a precursor to actual adoption.

- Actual system use: The individual’s real-world use of a particular technology, extending from behavioral intention to practical adoption and usage.

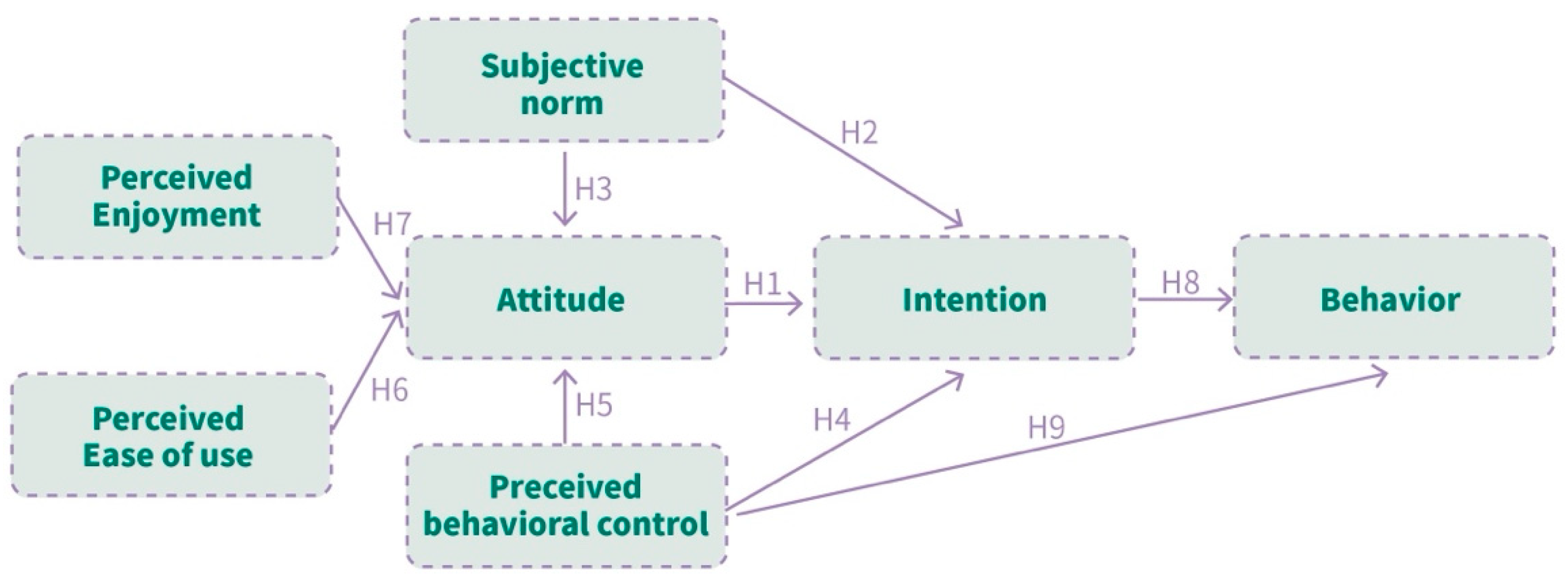

2.1.3. Model Integration

2.2. Revised Behavior Model

2.2.1. Attitude

2.2.2. Subjective Norm

2.2.3. Perceived Behavioral Control

2.2.4. Perceived Ease of Use

2.2.5. Perceived Enjoyment

2.2.6. Intention

3. Research Process and Methods

3.1. Design Overview

3.2. Design Process

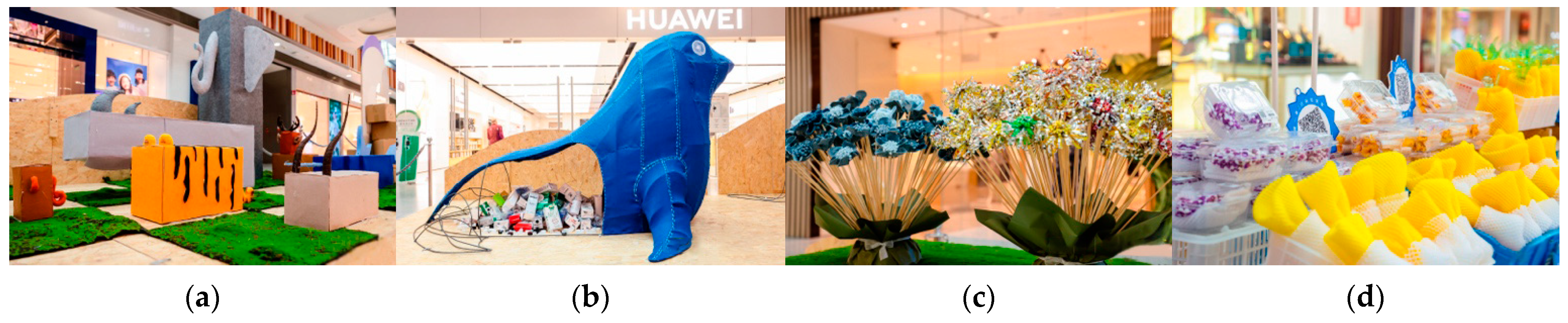

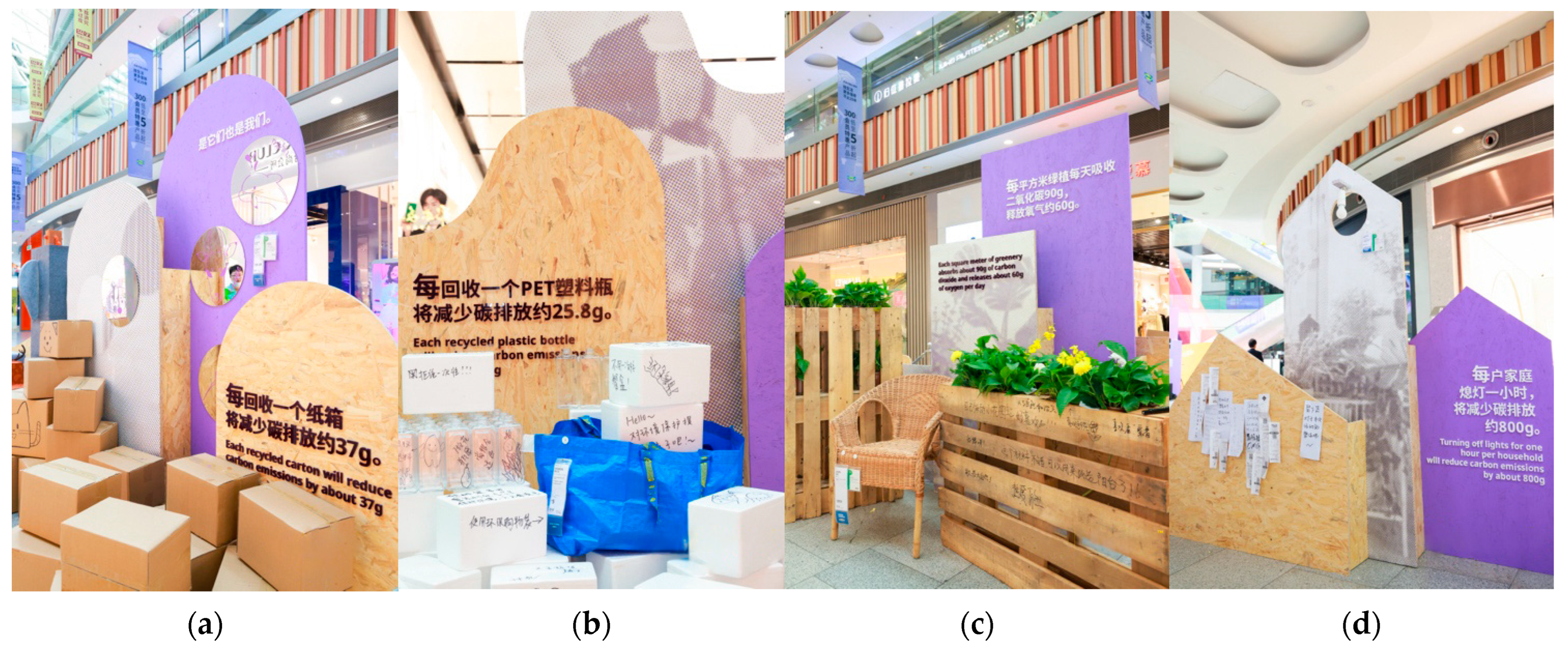

3.2.1. Project Overview

3.2.2. Co-Creation Section

3.2.3. Workshop

3.3. Questionnaire Design

4. Research Analysis

4.1. Data Sample Analysis

4.2. Descriptive Statistics

4.3. Reliability Analysis

4.4. Validity Analysis

4.4.1. Exploratory Factor Analysis

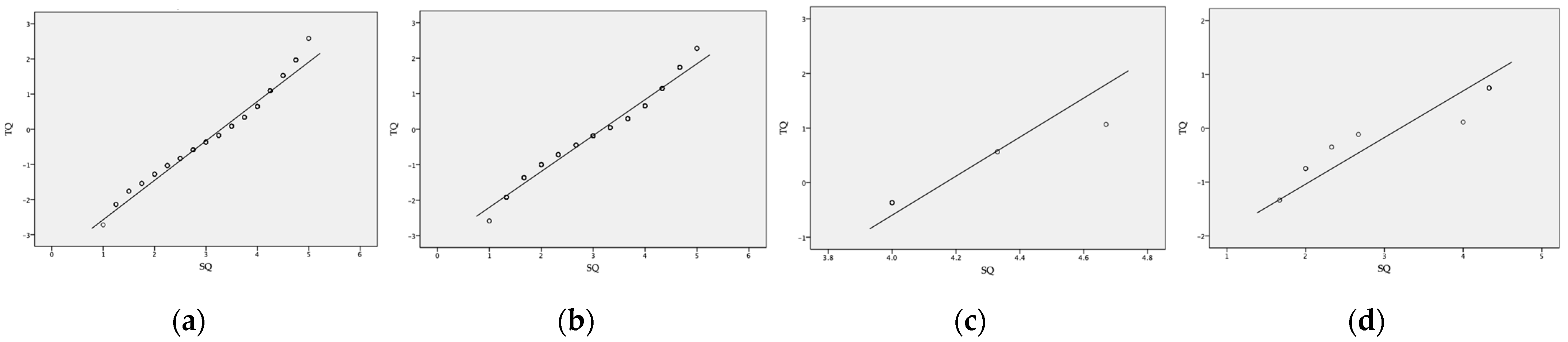

4.4.2. Confirmatory Factor Analysis

4.5. Correlation Analysis

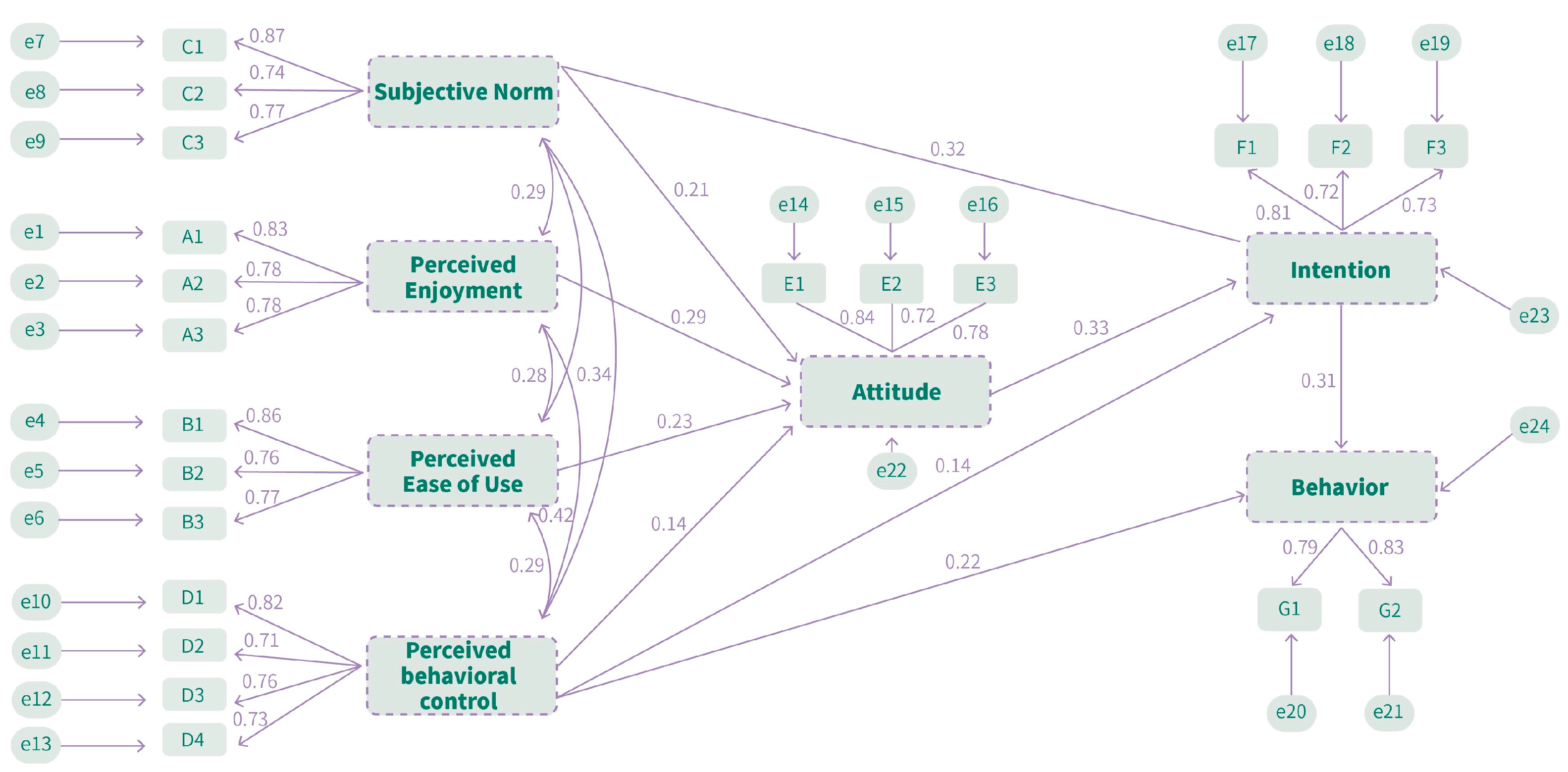

4.6. Structural Equation Model Test

5. Results

6. Discussion and Implications

6.1. Discussion of the Results

6.2. Theoretical and Practical Implications

6.3. Limitations and Future Research

- At the government level, formulate relevant policies and guidelines, strengthen promotion and education with respect to upcycling, enhance public awareness of upcycling, and regulate behavior. This includes economic incentives for upcycling behaviors, tax reductions for environmental protection, environmental standards and certifications, etc., to encourage public participation in upcycling activities and advocate for more sustainable lifestyles. Different levels of support can be provided, such as establishing upcycling fund projects and providing financial support, investing in upcycling facility construction, developing innovative technologies, and cultivating talents.

- At the commercial level, advocate for sustainable concepts using commercial resources, incorporate upcycling into sustainable development strategies and business models, promote the circulation of corporate resources, and promote sustainable consumption methods. Environmental products and services can be launched to enhance corporate image; by leveraging brand effects and resource advantages, dynamic and interesting upcycling co-creation activities can be offered as a service to promote consumption while increasing consumer awareness and stimulating consumer upcycling behavior.

- At the societal level, social organizations and media can stimulate positive consumer behavior through educational and promotional activities, such as interesting TV programs, media events, short video dissemination, etc. Furthermore, platforms for communication can be established to organize upcycling exchange activities and community projects, provide resource sharing and technical support, promote experience sharing and cooperation, and foster a good community cultural atmosphere and community cohesion.

- At the consumer level, consumers can be motivated to engage in upcycling by utilizing the facilities and services provided by the government and communities to gain convenience and rewards. Additionally, consumers can actively participate in educational and training activities conducted by governments or social organizations to improve their understanding and mastery of upcycling skills and knowledge.

7. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- You, W.; Zhang, Y.; Lee, C.C. The dynamic impact of economic growth and economic complexity on CO2 emissions: An advanced panel data estimation. Econ. Anal. Policy 2022, 73, 112–128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, F.; Zhang, Y. Simulation of Development Strategies and Evaluation of Low-Carbon Development Level in Jiangsu Province under Carbon Peaking and Carbon Neutrality Goals. Sustainability 2024, 16, 1597. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shi, T.; Huang, R.; Sarigöllü, E. A qualitative study on internal motivations and consequences of consumer upcycling. J. Clean. Prod. 2022, 377, 134–185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Braungart, M. Upcycle to eliminate waste: The chemist recasts materials in an endless loop. Nature 2013, 494, 174–175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martin, M.; Eklund, M. Improving the environmental performance of biofuels with industrial symbiosis. Biomass Bioenergy 2011, 35, 1747–1755. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bridgens, B.; Powell, M.; Farmer, G.; Walsh, C.; Reed, E.; Royapoor, M.; Gosling, P.; Hall, J.; Heidrich, O. Creative upcycling: Reconnecting people, materials and place through making. J. Clean. Prod. 2018, 189, 145–154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nastasi, R.; Proietti, G.; Marino, C.; Remondino, C.L. Strategy models for upcycling. How to create a systemic change through practice potentialities. AALTO UNIVERSITY PUBLICATION SERIES. ART+ DESIGN+ ARCHITECTURE 2023, 3, 695–703. [Google Scholar]

- Park, H.K. Current state and analysis of domestic and overseas upcycling product brands. Treatise Plast. Media 2018, 21, 48–57. [Google Scholar]

- Sung, K. A review on upcycling: Current body of literature, knowledge gaps and a way forward. In Proceedings of the ICECESS: 17th International Conference on Environmental, Cultural, Economic and Social Sustainability, Venice, Italy, 13–14 April 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Guselnikova, O.; Semyonov, O.; Sviridova, E.; Gulyaeu, R.; Gorbunova, A.; Kogolev, D.; Trelin, A.; Yamauchi, Y.; Boukherroub, R.; Postnikov, P. “Functional upcycling” of polymer waste towards the design of new materials. Chem. Soc. Rev. 2023, 14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, S.; Lee, J. The effects of consumers’ perceived values on intention to purchase upcycled products. Sustainability 2019, 11, 1034. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burns, A. Upcycling Classics—Sustainable Design Development through Fabric Manipulation Techniques in Fashion Design Education. Int. J. Art Des. Educ. 2024, 43, 272–288. [Google Scholar]

- Wu, D.; Zhuang, M.; Zhang, X.; Zhao, Y. Towards Circular Fashion: Design for Community-Based Clothing Reuse and Upcycling Services under a Social Innovation Perspective. Sustainability 2022, 15, 262. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sung, K. Evaluating two interventions for scaling up upcycling: Community event and upcycling plaza. In Proceedings of the International Conference on Resource Sustainability, Dublin, Ireland, 19–23 July 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Ly, S.; Furukawa, R. Factors That Influence Clothing Upcycling Behavior in Japan: Extending the Theory of Planned Behavior. Sustainability 2024, 16, 6116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sung, K.; Cooper, T.; Kettley, S. Factors influencing upcycling for UK makers. Sustainability 2019, 11, 870. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhatt, D.; Silverman, J.; Dickson, M.A. Consumer interest in upcycling techniques and purchasing upcycled clothing as an approach to reducing textile waste. International Journal of Fashion Design. Technol. Educ. 2019, 12, 118–128. [Google Scholar]

- Coppola, C.; Vollero, A.; Siano, A. Consumer upcycling as emancipated self-production: Understanding motivations and identifying upcycler types. J. Clean. Prod. 2021, 285, 124–812. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, S. Bringing Everyday Design into People’s Life: Design Considerations for Facilitating Everyday Design Behavior. Ph.D. Thesis, Ulsan National Institute of Science and Technology, Ulsan, Republic of Korea, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Yue, S.; Wang, P.; Yu, B.; Zhang, T.; Zhao, Z.; Li, Y.; Zhan, S. From plastic waste to treasure: Selective upcycling through catalytic technologies. Adv. Energy Mater. 2023, 13, 2302008. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jackson, T. Motivating sustainable consumption: A review of evidence on consumer behaviour and behavioural change. Sustain. Dev. Res. Netw. 2005, 29, 30–40. [Google Scholar]

- Tonglet, M.; Phillips, P.S.; Read, A.D. Using the Theory of Planned Behaviour to investigate the determinants of recycling behaviour: A case study from Brixworth, UK. Resour. Conserv. Recycl. 2004, 41, 191–214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barr, S.; Gilg, A.; Shaw, G. ‘Helping People Make Better Choices’: Exploring the behaviour change agenda for environmental sustainability. Appl. Geogr. 2011, 31, 712–720. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Casalegno, C.; Candelo, E.; Santoro, G. Exploring the antecedents of green and sustainable purchase behaviour: A comparison among different generations. Psychol. Mark. 2022, 39, 1007–1021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ur Rahman, S.; Chwialkowska, A.; Hussain, N.; Bhatti, W.A.; Luomala, H. Cross-cultural perspective on sustainable consumption: Implications for consumer motivations and promotion. Environment. Dev. Sustain. 2023, 25, 997–1016. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Choi, S.; Kim, I. Role of restorative natural environments in predicting hikers’ pro-environmental behavior in a nature trail context. J. Travel Tour. Mark. 2024, 41, 596–613. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Quan, L.; Koo, B.; Han, H. Exploring the factors that influence customers’ willingness to switch from traditional hotels to green hotels. J. Travel Tour. Mark. 2023, 40, 185–202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stern, P.C. New environmental theories: Toward a coherent theory of environmentally significant behavior. J. Soc. Issues 2000, 56, 407–424. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kallbekken, S.; Rise, J.; Westskog, H. Combining insights from economics and social psychology to explain environmentally significant consumption. In Sustainable Energy, 1st ed.; John, K.D., Rübbelke, D.T.G., Eds.; Routledge: London, UK, 2010; pp. 127–145. [Google Scholar]

- Martiskainen, M. Affecting consumer behaviour on energy demand. Sussex SPRU–Sci. Technol. Policy Res. 2007, 81, 42–49. [Google Scholar]

- Ajzen, I. The theory of planned behavior. Organ. Behav. Hum. Decis. Process. 1991, 50, 179–211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fishbein, M.; Ajzen, I. Belief, attitude, intention, and behavior: An introduction to theory and research. Philos. Rhetor. 1977, 10, 130–132. [Google Scholar]

- Armitage, C.J.; Conner, M. Efficacy of the theory of planned behaviour: A meta-analytic review. Br. J. Soc. Psychol. 2001, 40, 471–499. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Joo, K.; Kim, J.; Hwang, J. Effects of foodservice consumers’ perceptions of face recognition payment on attitude, desire, and behavioral intentions: A cross-cultural study. J. Travel Tour. Mark. 2024, 41, 359–376. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Davis, F.D. Perceived usefulness, perceived ease of use, and user acceptance of information technology. MIS Q. 1989, 13, 319–340. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.Q.; Henseler, J.; Liu, Y.D. What makes tourists adopt smart hospitality? An inquiry beyond the technology acceptance model. Digit. Bus. 2022, 2, 100042. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, C.D.; Fan, Y.W.; Farn, C.K. Predicting electronic toll collection service adoption: An integration of the technology acceptance model and the theory of planned behavior. Transp. Res. Part C Emerg. Technol. 2007, 15, 300–311. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Choe, J.Y.; Kim, J.J.; Hwang, J. Innovative robotic restaurants in Korea: Merging a technology acceptance model and theory of planned behaviour. Asian J. Technol. Innov. 2022, 30, 466–489. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rausch, T.M.; Kopplin, C.S. Bridge the gap: Consumers’ purchase intention and behavior regarding sustainable clothing. J. Clean. Prod. 2021, 278, 123882. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kang, J.; Liu, C.; Kim, S.H. Environmentally sustainable textile and apparel consumption: The role of consumer knowledge, perceived consumer effectiveness and perceived personal relevance. Int. J. Consum. Stud. 2013, 37, 442–452. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, S.H.; Seock, Y.K. The roles of values and social norm on personal norms and pro-environmentally friendly apparel product purchasing behavior: The mediating role of personal norms. J. Retail. Consum. Serv. 2019, 51, 83–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ajzen, I. From intentions to actions: A theory of planned behavior. In Action Control: From Cognition to Behavior; Kuhl, J., Beckmann, J., Eds.; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 1985; pp. 11–39. [Google Scholar]

- Paul, J.; Modi, A.; Patel, J. Predicting green product consumption using theory of planned behavior and reasoned action. J. Retail. Consum. Serv. 2016, 29, 123–134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shen, C.C.; Chiou, J.S. The impact of perceived ease of use on Internet service adoption: The moderating effects of temporal distance and perceived risk. Comput. Hum. Behav. 2010, 26, 42–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kowalczuk, P. Consumer acceptance of smart speakers: A mixed methods approach. J. Res. Interact. Mark. 2018, 12, 418–431. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bryman, A. Social Research Methods, 5th ed.; Oxford University Press: Oxford, UK, 2016; pp. 1–747. [Google Scholar]

- Livat. Available online: https://www.livat.cn/zh-cn/about-us/ (accessed on 5 June 2024).

- Constructing a TPB Questionnaire: Conceptual and Methodological Considerations. Available online: https://people.umass.edu/aizen/pdf/tpb.measurement.pdf (accessed on 5 June 2024).

- Chen, S.Y. Green helpfulness or fun? Influences of green perceived value on the green loyalty of users and non-users of public bikes. Transp. Policy 2016, 47, 149–159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maichum, K.; Parichatnon, S.; Peng, K.C. Application of the extended theory of planned behavior model to investigate purchase intention of green products among Thai consumers. Sustainability 2016, 8, 1077. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mallery, P.; George, D. SPSS for Windows Step by Step; Allyn & Bacon, Inc.: Needham, MA, USA, 2000; pp. 1–371. [Google Scholar]

- Kline, P. An Easy Guide to Factor Analysis; Routledge: London, UK, 2014; pp. 1–208. [Google Scholar]

- Stevens, J.P. Applied Multivariate Statistics for the Social Sciences, 5th ed.; Routledge: Cincinnati, OH, USA, 2012; pp. 337–406. [Google Scholar]

- Gansser, O.A.; Reich, C.S. Influence of the new ecological paradigm (NEP) and environmental concerns on pro-environmental behavioral intention based on the theory of planned behavior (TPB). J. Clean. Prod. 2023, 382, 134629. [Google Scholar]

- Albayati, H.; Alistarbadi, N.; Rho, J.J. Assessing engagement decisions in NFT Metaverse based on the Theory of Planned Behavior (TPB). Telemat. Inform. Rep. 2023, 10, 100045. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Belida, P.R.C.; Ong, A.K.S.; Young, M.N.; German, J.D. Determining the Factors Influencing the Behavioral Intention of Job-Seeking Filipinos to Career Shift and Greener Pasture. Societies 2024, 14, 145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Su, D.L.; Wan, A.W.; Zhang, L.; Teng, J.; Chan, D.K. Predicting Adolescents’ Leisure-Time Physical Activity Levels: A Three-Wave Prospective Test of the Integrated Model of Self-Determination Theory and the Theory of Planned Behavior. Behav. Sci. 2024, 14, 693. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Godin, G.; Valois, P.; Lepage, L. The pattern of influence of perceived behavioral control upon exercising behavior: An application of Ajzen’s theory of planned behavior. J. Behav. Med. 1993, 16, 81–102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, P.; Lin, I.K.; Chen, H.S. Low Carbon Sustainable Diet Choices—An Analysis of the Driving Factors behind Plant-Based Egg Purchasing Behavior. Nutrients 2024, 16, 2604. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ajzen, I.; Fishbein, M. Understanding Attitudes and Predicting Social Behavior. Exp. Soc. Psychol 1980, 22, 453–474. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Villanueva, D.J.B.; Ong, A.K.S.; German, J.D. Machine Learning Methods Analysis of Preceding Factors Affecting Behavioral Intentions to Purchase Reduced Plastic Products. Sustainability 2024, 16, 2978. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khan, F.; Ahmed, W.; Najmi, A. Understanding consumers’ behavior intentions towards dealing with the plastic waste: Perspective of a developing country. Resour. Conserv. Recycl. 2019, 142, 49–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saoula, O.; Shamim, A.; Suki, N.M.; Ahmad, M.J.; Abid, M.F.; Patwary, A.K.; Abbasi, A.Z. Building e-trust and e-retention in online shopping: The role of website design, reliability and perceived ease of use. Span. J. Mark.-ESIC 2023, 27, 178–201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deng, Y.; Shen, H.; Ji, X. Exploring Virtual Fashion Consumption through the Emotional Three-Level Theory: Reflections on Sustainable Consumer Behavior. Sustainability 2024, 16, 5818. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Warganegara, D.L.; Babolian Hendijani, R. Factors That Drive Actual Purchasing of Groceries through E-Commerce Platforms during COVID-19 in Indonesia. Sustainability 2022, 14, 3235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Klopping, I.M.; McKinney, E. Extending the technology acceptance model and the task-technology fit model to consumer e-commerce. Inf. Technol. Learn. Perform. J. 2004, 22, 1–14. [Google Scholar]

- Ali, M.; Ullah, S.; Ahmad, M.S.; Cheok, M.Y.; Alenezi, H. Assessing the impact of green consumption behavior and green purchase intention among millennials toward sustainable environment. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 2023, 30, 23335–23347. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, S.; Zhong, Z.; Zhu, Y.; Sun, J. Green Emotion: Incorporating Emotional Perception in Green Marketing to Increase Green Furniture Purchase Intentions. Sustainability 2024, 16, 4935. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, C.; Han, Y.; Ng, P. Green consumption intention and behavior of tourists in urban and rural destinations. J. Environ. Plan. Manag. 2023, 66, 2126–2150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carfora, V.; Cavallo, C.; Catellani, P.; Del Giudice, T.; Cicia, G. Why Do Consumers Intend to Purchase Natural Food? Integrating Theory of Planned Behavior, Value-Belief-Norm Theory, and Trust. Nutrients 2021, 13, 1904. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Canova, L.; Bobbio, A.; Manganelli, A.M. Buying organic food products: The role of trust in the theory of planned behavior. Front. Psychol. 2020, 11, 575–820. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qi, X.; Ploeger, A. Explaining Chinese Consumers’ Green Food Purchase Intentions During the COVID-19 Pandemic: An Extended Theory of Planned Behaviour. Foods 2021, 10, 1200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ruzgys, S.; Pickering, G.J. Gen Z and sustainable diets: Application of The Transtheoretical Model and the theory of planned behaviour. J. Clean. Prod. 2024, 434, 140300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fauzi, M.A.; Hanafiah, M.H.; Kunjuraman, V. Tourists’ intention to visit green hotels: Building on the theory of planned behaviour and the value-belief-norm theory. J. Tour. Futures 2024, 10, 255–276. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, L.; Wong, P.P.; Narayanan, E.A. The demographic impact of consumer green purchase intention toward green hotel selection in China. Tour. Hosp. Res. 2020, 20, 210–222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liao, C.; Huang, Y.; Zheng, Z.; Xu, Y. Investigating the factors influencing urban residents’ low-carbon travel intention: A comprehensive analysis based on the TPB model. Transp. Res. Interdiscip. Perspect. 2023, 22, 100948. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, H. Travelers’ pro-environmental behavior in a green lodging context: Converging value-belief-norm theory and the theory of planned behavior. Tour. Manag. 2015, 47, 164–177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qiu, H.; Wang, X.; Morrison, A.M.; Kelly, C.; Wei, W. From ownership to responsibility: Extending the theory of planned behavior to predict tourist environmentally responsible behavioral intentions. J. Sustain. Tour. 2022, 1–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cao, J.; Qiu, H.; Morrison, A.M. Self-identity matters: An extended theory of planned behavior to decode tourists’ waste sorting intentions. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2023, 20, 5099. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wildt, K.K.D.; Meijers, M.H.C. Time spent on separating waste is never wasted: Fostering people’s recycling behavior through the use of a mobile application. Comput. Hum. Behav. 2023, 139, 107541. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Halder, P.; Singh, H. Predictors of Recycling Intentions among the Youth: A Developing Country Perspective. Recycling 2018, 3, 38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, C.; Ahmad, S.F.; Ayassrah, A.Y.A.B.A.; Awwad, E.M.; Irshad, M.; Ali, Y.A.; AI-Razgan, M.; Khan, Y.; Han, H. An empirical evaluation of technology acceptance model for Artificial Intelligence in E-commerce. Heliyon 2023, 9, e18349. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, S.F.; Chen, C.C. Exploring Designer Trust in Artificial Intelligence-Generated Content: TAM/TPB Model Study. Appl. Sci. 2024, 14, 6902. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mohr, S.; Kühl, R. Acceptance of artificial intelligence in German agriculture: An application of the technology acceptance model and the theory of planned behavior. Precis. Agric. 2021, 22, 1816–1844. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vahdat, A.; Alizadeh, A.; Quach, S.; Hamelin, N. Would you like to shop via mobile app technology? The technology acceptance model, social factors and purchase intention. Australas. Mark. J. 2021, 29, 187–197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, J.; Song, S. Older adults’ online shopping continuance intentions: Applying the technology acceptance model and the theory of planned behavior. Int. J. Hum.-Comput. Interact. 2021, 37, 938–948. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sajid, S.; Rashid, R.M.; Haider, W. Changing trends of consumers’ online buying behavior during COVID-19 pandemic with moderating role of payment mode and gender. Front. Psychol. 2022, 13, 919334. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ceschin, F.; Gaziulusoy, I. Evolution of design for sustainability: From product design to design for system innovations and transitions. Des. Stud. 2016, 47, 118–163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Construct | Scale Items | Source |

|---|---|---|

| Perceived Enjoyment | A1: I think upcycling can be a crafting experience. A2: I think upcycling can relieve stress. A3: I think upcycling is a good way to spend my free time. | [49] |

| Perceived Ease of Use | B1: Upcycling doesn’t take much of my time. B2: I have enough space in my home to support recycling. B3: I am very creative when upcycling. | [35] |

| Subjective Norms | C1: I would feel guilty about not upcycling (e.g., drink bottles can still hold spices, etc.) C2: Upcycling is in line with what my friends and family expect of me. C3: Social policies support upcycling. | [48] |

| Perceived Behavioral Control | D1: Overall, I think upcycling is easy. D2: There are no significant production costs associated with upcycling. D3: There is no outside influence on whether I upgrade or not. D4: The difficulty of upcycling directly affects my attitude. | |

| Attitude | E1: For me upcycling is pleasant. E2: For me upgrading is useful. E3: I think upcycling should be done. | [48] |

| Intention | F1: In the future, I intend to upcycle. F2: In the future, I intend to increase the frequency of upcycling. F3: In the future, I intend to plan for the reuse of waste. | |

| Behavior | G1: In the past year, how often have you upcycled? G2: In the past year, what percentage of the time did you use your own rebuilt products? |

| Name | Options | Frequency | Percentage (%) | Cumulative Percentage (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Gender | Male | 130 | 38.69 | 38.69 |

| Female | 206 | 61.31 | 100.00 | |

| Age Group | <18 | 33 | 9.82 | 9.82 |

| 18–25 | 277 | 82.44 | 92.26 | |

| 26–35 | 15 | 4.46 | 96.73 | |

| 36–45 | 10 | 2.98 | 99.70 | |

| 46–60 | 1 | 0.30 | 100.00 | |

| Income Status | <100,000 RMB | 307 | 91.37 | 91.37 |

| 100,000–200,000 RMB | 13 | 3.87 | 95.24 | |

| 200,001–400,000 RMB | 6 | 1.79 | 97.02 | |

| >400,000 RMB | 10 | 2.98 | 100.00 | |

| Education Level | Below bachelor’s degree | 76 | 22.62 | 22.62 |

| Bachelor’s degree | 243 | 72.32 | 94.94 | |

| Master’s degree and above | 17 | 5.06 | 100.00 | |

| Frequency of Waste Reuse in Daily Life | Almost every day | 72 | 21.43 | 21.43 |

| Once a week | 95 | 28.27 | 49.70 | |

| Once a month | 79 | 23.51 | 73.21 | |

| Once a year | 27 | 8.04 | 81.25 | |

| Almost never | 63 | 18.75 | 100.00 |

| SS | df | MS | F | p | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Perceived Enjoyment | B | 1.064 | 2 | 0.532 | 0.476 | 0.621 |

| W | 371.904 | 333 | 1.117 | |||

| T | 372.968 | 335 | ||||

| Perceived Ease of Use | B | 0.033 | 2 | 0.017 | 0.015 | 0.985 |

| W | 374.457 | 333 | 1.124 | |||

| T | 374.490 | 335 | ||||

| Subjective Norms | B | 0.097 | 2 | 0.049 | 0.044 | 0.957 |

| W | 364.837 | 333 | 1.096 | |||

| T | 364.934 | 335 | ||||

| Perceived Behavioral Control | B | 0.269 | 2 | 0.134 | 0.157 | 0.855 |

| W | 285.325 | 333 | 0.857 | |||

| T | 285.594 | 335 | ||||

| Attitude | B | 5.297 | 2 | 2.649 | 2.750 | 0.065 |

| W | 320.697 | 333 | 0.963 | |||

| T | 325.994 | 335 | ||||

| Intention | B | 6.776 | 2 | 3.388 | 3.743 | 0.025 |

| W | 301.402 | 333 | 0.905 | |||

| T | 308.178 | 335 | ||||

| Behavior | B | 1.254 | 2 | 0.627 | 0.516 | 0.597 |

| W | 404.728 | 333 | 1.215 | |||

| T | 405.981 | 335 |

| Form | Options | Shapiro-Wilk | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| W | df | p | ||

| Intention | Below bachelor’s degree | 0.934 | 76 | 0.001 |

| Bachelor’s degree | 0.947 | 243 | 0.000 | |

| Master’s degree and above | 0.827 | 17 | 0.005 | |

| DV | (I) Education Level | (J) Education Level | MD(I–J) | SE | p | 95% Confidence Interval | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Lower Limit | Upper Bound | ||||||

| Attitude | Below bachelor’s degree | Bachelor’s degree | 0.02858 | 0.12504 | 0.819 | −0.2174 | 0.2745 |

| Below bachelor’s degree | Bachelor’s degree | −0.62392 * | 0.25525 | 0.015 | −1.1260 | −0.1218 | |

| Bachelor’s degree | Master’s degree and above | −0.65250 * | 0.23868 | 0.007 | −1.1220 | −0.1830 | |

| SS | df | MS | F | p | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Perceived Enjoyment | B | 2.573 | 3 | 0.858 | 0.769 | 0.512 |

| W | 370.395 | 332 | 1.116 | |||

| T | 372.968 | 335 | ||||

| Perceived Ease of Use | B | 5.829 | 3 | 1.943 | 1.750 | 0.157 |

| W | 368.661 | 332 | 1.110 | |||

| T | 374.490 | 335 | ||||

| Subjective Norms | B | 0.477 | 3 | 0.159 | 0.145 | 0.933 |

| W | 364.456 | 332 | 1.098 | |||

| T | 364.934 | 335 | ||||

| Perceived Behavioral Control | B | 33.390 | 3 | 11.130 | 14.652 | 0.000 |

| W | 252.203 | 332 | 0.760 | |||

| T | 285.594 | 335 | ||||

| Attitude | B | 10.641 | 3 | 3.547 | 3.734 | 0.012 |

| W | 315.353 | 332 | 0.950 | |||

| T | 325.994 | 335 | ||||

| Intention | B | 2.275 | 3 | 0.758 | 0.823 | 0.482 |

| W | 305.903 | 332 | 0.921 | |||

| T | 308.178 | 335 | ||||

| Behavior | B | 4.511 | 3 | 1.504 | 1.243 | 0.294 |

| W | 401.471 | 332 | 1.209 | |||

| T | 405.981 | 335 |

| Form | Income Status | Shapiro-Wilk | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| W | df | p | ||

| Perceived Behavioral Control | <100,000 RMB | 0.963 | 307 | 0.000 |

| 100,000–200,000 RMB | 0.916 | 13 | 0.225 | |

| 200,001–400,000 RMB | 0.800 | 6 | 0.059 | |

| >400,000 RMB | 0.884 | 10 | 0.144 | |

| Attitude | <100,000 RMB | 0.955 | 307 | 0.000 |

| 100,000–200,000 RMB | 0.919 | 13 | 0.247 | |

| 200,001–400,000 RMB | 0.700 | 6 | 0.006 | |

| >400,000 RMB | 0.796 | 10 | 0.013 | |

| DV | (I) Income Status | (J) Income Status | MD(I-J) | SE | p | 95% Confidence Interval | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Lower Limit | Upper Bound | ||||||

| Perceived Behavioral Control | <100,000 RMB | 100,000–200,000 RMB | 1.43022 * | 0.24680 | 0.000 | 0.9447 | 1.9157 |

| <100,000 RMB | 200,001–400,000 RMB | 1.21227 * | 0.35928 | 0.001 | 0.5055 | 1.9190 | |

| <100,000 RMB | >400,000 RMB | 0.02060 | 0.28007 | 0.941 | −0.5303 | 0.5715 | |

| 100,000–200,000 RMB | 200,001–400,000 RMB | −0.21795 | 0.43017 | 0.613 | −1.0641 | 0.6282 | |

| 100,000–200,000 RMB | >400,000 RMB | −1.40962 * | 0.36661 | 0.000 | −2.1308 | −0.6885 | |

| 200,001–400,000 RMB | >400,000 RMB | −1.19167 * | 0.45008 | 0.008 | −2.0770 | −0.3063 | |

| Attitude | <100,000 RMB | 100,000–200,000 RMB | −0.64377 * | 0.27597 | 0.020 | −1.1866 | −0.1009 |

| <100,000 RMB | 200,001–400,000 RMB | −0.98966 * | 0.40175 | 0.014 | −1.7800 | −0.1994 | |

| <100,000 RMB | >400,000 RMB | −0.02200 | 0.31318 | 0.944 | −0.6381 | 0.5941 | |

| 100,000–200,000 RMB | 200,001–400,000 RMB | −0.34590 | 0.48102 | 0.473 | −1.2921 | 0.6003 | |

| 100,000–200,000 RMB | >400,000 RMB | 0.62177 | 0.40994 | 0.130 | −0.1846 | 1.4282 | |

| 200,001–400,000 RMB | >400,000 RMB | 0.96767 | 0.50328 | 0.055 | −0.0224 | 1.9577 | |

| Name | Mean | Standard Deviation | Skewness | Kurtosis |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Perceived Enjoyment | 3.115 | 1.055 | −0.422 | −0.939 |

| Perceived Ease of Use | 3.107 | 1.057 | −0.335 | −1.052 |

| Subjective Norms | 3.209 | 1.044 | −0.342 | −0.947 |

| Perceived Behavioral Control | 3.218 | 0.923 | −0.35 | −0.786 |

| Attitude | 3.220 | 0.986 | −0.29 | −0.988 |

| Intention | 3.151 | 0.959 | −0.211 | −1.121 |

| Behavior | 3.243 | 1.101 | −0.434 | −0.872 |

| Dimension | Number of Items | Sample Size | Cronbach’s Alpha Coefficient |

|---|---|---|---|

| Perceived Enjoyment | 3 | 336 | 0.835 |

| Perceived Ease of Use | 3 | 336 | 0.834 |

| Subjective Norm | 3 | 336 | 0.830 |

| Perceived Behavioral Control | 4 | 336 | 0.838 |

| Attitude | 3 | 336 | 0.815 |

| Intention | 3 | 336 | 0.791 |

| Behavior | 2 | 336 | 0.783 |

| KMO Value | 0.838 | |

| Bartlett’s test of sphericity | Approximate Chi-Square | 3303.342 |

| df | 210 | |

| p | 0.000 | |

| Factor Number | Eigenvalues | Pre-Rotation Variance Explained | Post-Rotation Variance Explained | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Eigenvalues | Percentage of Variance Explained (%) | Cumulative (%) | Eigenvalues | Percentage of Variance Explained (%) | Cumulative (%) | Eigenvalues | Percentage of Variance Explained (%) | Cumulative (%) | |

| 1 | 6.693 | 31.874 | 31.874 | 6.693 | 31.874 | 31.874 | 2.808 | 13.374 | 13.374 |

| 2 | 1.989 | 9.470 | 41.344 | 1.989 | 9.470 | 41.344 | 2.292 | 10.914 | 24.288 |

| 3 | 1.776 | 8.457 | 49.800 | 1.776 | 8.457 | 49.800 | 2.290 | 10.907 | 35.195 |

| 4 | 1.544 | 7.352 | 57.153 | 1.544 | 7.352 | 57.153 | 2.267 | 10.796 | 45.991 |

| 5 | 1.329 | 6.331 | 63.483 | 1.329 | 6.331 | 63.483 | 2.215 | 10.546 | 56.537 |

| 6 | 1.224 | 5.831 | 69.314 | 1.224 | 5.831 | 69.314 | 2.131 | 10.149 | 66.686 |

| 7 | 1.114 | 5.304 | 74.618 | 1.114 | 5.304 | 74.618 | 1.666 | 7.932 | 74.618 |

| Name | Factor Loadings | Communality (Common Factor Variance) | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Factor 1 | Factor 2 | Factor 3 | Factor 4 | Factor 5 | Factor 6 | Factor 7 | ||

| A1 | 0.139 | 0.001 | 0.880 | 0.048 | 0.107 | 0.050 | 0.111 | 0.822 |

| A2 | 0.236 | 0.161 | 0.766 | 0.093 | 0.168 | 0.088 | 0.107 | 0.724 |

| A3 | 0.075 | 0.099 | 0.821 | 0.098 | 0.156 | 0.136 | 0.107 | 0.753 |

| B1 | 0.036 | 0.910 | 0.053 | 0.111 | 0.064 | 0.069 | 0.034 | 0.855 |

| B2 | 0.171 | 0.770 | 0.036 | 0.124 | 0.157 | 0.183 | 0.154 | 0.721 |

| B3 | 0.095 | 0.796 | 0.156 | 0.097 | 0.176 | 0.113 | 0.072 | 0.726 |

| C1 | 0.070 | 0.128 | 0.069 | 0.893 | 0.073 | 0.123 | 0.031 | 0.845 |

| C2 | 0.159 | 0.104 | 0.063 | 0.779 | 0.096 | 0.196 | 0.107 | 0.705 |

| C3 | 0.145 | 0.100 | 0.106 | 0.778 | 0.225 | 0.168 | −0.022 | 0.726 |

| D1 | 0.880 | 0.008 | 0.104 | 0.048 | 0.055 | 0.063 | −0.009 | 0.796 |

| D2 | 0.750 | 0.087 | 0.118 | 0.056 | 0.075 | 0.176 | 0.111 | 0.636 |

| D3 | 0.780 | 0.110 | 0.056 | 0.177 | 0.148 | 0.056 | 0.086 | 0.688 |

| D4 | 0.731 | 0.109 | 0.177 | 0.117 | 0.138 | 0.080 | 0.085 | 0.624 |

| E1 | 0.055 | 0.144 | 0.141 | 0.124 | 0.866 | 0.140 | 0.050 | 0.831 |

| E2 | 0.176 | 0.162 | 0.208 | 0.141 | 0.724 | 0.135 | 0.072 | 0.668 |

| E3 | 0.195 | 0.109 | 0.112 | 0.136 | 0.768 | 0.158 | 0.180 | 0.729 |

| F1 | 0.083 | 0.107 | 0.100 | 0.125 | 0.082 | 0.879 | 0.053 | 0.826 |

| F2 | 0.211 | 0.100 | 0.113 | 0.195 | 0.133 | 0.730 | 0.089 | 0.664 |

| F3 | 0.075 | 0.162 | 0.064 | 0.188 | 0.221 | 0.724 | 0.140 | 0.664 |

| G1 | 0.077 | 0.093 | 0.178 | 0.020 | 0.061 | 0.163 | 0.868 | 0.830 |

| G2 | 0.147 | 0.130 | 0.117 | 0.081 | 0.188 | 0.073 | 0.859 | 0.837 |

| Indicator Name | Fit Standard | Test Result | Acceptability |

|---|---|---|---|

| CMIN/df | <3 | 2.040 | Acceptance |

| RMSEA | <0.08 | 0.056 | Acceptance |

| GFI | >0.8 | 0.916 | Acceptance |

| NFI | >0.8 | 0.899 | Acceptance |

| IFI | >0.8 | 0.946 | Acceptance |

| CFI | >0.8 | 0.945 | Acceptance |

| TLI | >0.8 | 0.931 | Acceptance |

| PNFI | >0.5 | 0.719 | Acceptance |

| PCFI | >0.5 | 0.756 | Acceptance |

| Latent Variable | Measurement Item | Coefficient (Coef.) | Standard Error (Std. Error) | z (CR) | p | Standard Estimate (Std. Estimate) | Average Variance Extracted (AVE) | Composite Reliability (CR) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Perceived Enjoyment | A1 | 1 | - | - | - | 0.832 | 0.638 | 0.841 |

| A2 | 0.767 | 0.053 | 14.429 | 0 | 0.784 | |||

| A3 | 0.751 | 0.052 | 14.364 | 0 | 0.779 | |||

| Perceived Ease of Use | B1 | 1 | - | - | - | 0.858 | 0.639 | 0.841 |

| B2 | 0.726 | 0.051 | 14.323 | 0 | 0.768 | |||

| B3 | 0.73 | 0.051 | 14.336 | 0 | 0.769 | |||

| Subjective Norm | C1 | 1 | - | - | - | 0.868 | 0.634 | 0.838 |

| C2 | 0.693 | 0.05 | 13.989 | 0 | 0.743 | |||

| C3 | 0.739 | 0.051 | 14.513 | 0 | 0.773 | |||

| Perceived Behavioral Control | D1 | 1 | - | - | - | 0.823 | 0.571 | 0.841 |

| D2 | 0.722 | 0.055 | 13.134 | 0 | 0.712 | |||

| D3 | 0.780 | 0.056 | 14.036 | 0 | 0.757 | |||

| D4 | 0.735 | 0.055 | 13.415 | 0 | 0.726 | |||

| Attitude | E1 | 1 | - | - | - | 0.841 | 0.612 | 0.825 |

| E2 | 0.653 | 0.049 | 13.225 | 0 | 0.721 | |||

| E3 | 0.741 | 0.052 | 14.215 | 0 | 0.78 | |||

| Intention | F1 | 1 | - | - | - | 0.818 | 0.571 | 0.799 |

| F2 | 0.738 | 0.06 | 12.252 | 0 | 0.721 | |||

| F3 | 0.712 | 0.058 | 12.297 | 0 | 0.725 | |||

| Behavior | G1 | 1 | - | - | - | 0.777 | 0.660 | 0.795 |

| G2 | 0.879 | 0.098 | 8.981 | 0 | 0.846 |

| Perceived Enjoyment | Perceived Ease of Use | Subjective Norm | Perceived Behavioral Control | Attitude | Intention | Behavior | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Perceived Enjoyment | 0.799 | ||||||

| Perceived Ease of Use | 0.256 *** | 0.799 | |||||

| Subjective Norm | 0.253 *** | 0.318 *** | 0.796 | ||||

| Perceived Behavioral Control | 0.353 *** | 0.262 *** | 0.313 *** | 0.756 | |||

| Attitude | 0.403 *** | 0.377 *** | 0.378 *** | 0.350 *** | 0.782 | ||

| Intention | 0.295 *** | 0.349 *** | 0.434 *** | 0.322 *** | 0.415 *** | 0.756 | |

| Behavior | 0.341 *** | 0.278 *** | 0.182 *** | 0.261 *** | 0.325 *** | 0.312 *** | 0.813 |

| Perceived Entertainment | Perceived Ease of Use | Subjective Norm | Perceived Behavioral Control | Attitude | Intention | Behavior | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Perceived Entertainment | 1 | ||||||

| Perceived Ease of Use | 0.256 ** | 1 | |||||

| Subjective Norm | 0.253 ** | 0.318 ** | 1 | ||||

| Perceived Behavioral Control | 0.354 ** | 0.262 ** | 0.313 ** | 1 | |||

| Attitude | 0.403 ** | 0.376 ** | 0.377 ** | 0.350 ** | 1 | ||

| Intention | 0.295 ** | 0.349 ** | 0.434 ** | 0.322 ** | 0.415 ** | 1 | |

| Behavior | 0.342 ** | 0.278 ** | 0.182 ** | 0.261 ** | 0.325 ** | 0.312 ** | 1 |

| Path | Standard Path Coefficient | Unstandardized Path Coefficient | SE | CR | p | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| H1 | Attitude → Intention | 0.325 | 0.301 | 0.066 | 4.576 | 0.000 ** |

| H2 | Subjective Norms → Intention | 0.321 | 0.283 | 0.06 | 4.71 | 0.000 ** |

| H3 | Subjective Norms → Attitude | 0.209 | 0.2 | 0.061 | 3.255 | 0.001 ** |

| H4 | Perceived Behavioral Control → Intention | 0.135 | 0.183 | 0.089 | 2.063 | 0.039 * |

| H5 | Perceived Behavioral Control → Attitude | 0.142 | 0.208 | 0.097 | 2.15 | 0.032 * |

| H6 | Perceived Ease of Use → Attitude | 0.231 | 0.3 | 0.082 | 3.649 | 0.000 ** |

| H7 | Perceived Enjoyment → Attitude | 0.288 | 0.375 | 0.086 | 4.347 | 0.000 ** |

| H8 | Intention → Behavior | 0.314 | 0.316 | 0.076 | 4.148 | 0.000 ** |

| H9 | Perceived Behavioral Control → Behavior | 0.218 | 0.297 | 0.098 | 3.034 | 0.002 * |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Ma, K.; Liu, B.; Zhang, J. Factors Influencing Consumer Upcycling Behavior—A Study Based on an Integrated Model of the Theory of Planned Behavior and the Technology Acceptance Model. Sustainability 2024, 16, 9179. https://doi.org/10.3390/su16219179

Ma K, Liu B, Zhang J. Factors Influencing Consumer Upcycling Behavior—A Study Based on an Integrated Model of the Theory of Planned Behavior and the Technology Acceptance Model. Sustainability. 2024; 16(21):9179. https://doi.org/10.3390/su16219179

Chicago/Turabian StyleMa, Kaiyue, Bohan Liu, and Jie Zhang. 2024. "Factors Influencing Consumer Upcycling Behavior—A Study Based on an Integrated Model of the Theory of Planned Behavior and the Technology Acceptance Model" Sustainability 16, no. 21: 9179. https://doi.org/10.3390/su16219179

APA StyleMa, K., Liu, B., & Zhang, J. (2024). Factors Influencing Consumer Upcycling Behavior—A Study Based on an Integrated Model of the Theory of Planned Behavior and the Technology Acceptance Model. Sustainability, 16(21), 9179. https://doi.org/10.3390/su16219179