Perceived Greenwashing and Its Impact on the Green Image of Brands

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Literature Review

2.1. Brands’ Green Marketing

2.2. Perceived Greenwashing

2.3. Green Brand Image

3. Research Design and Data Collection

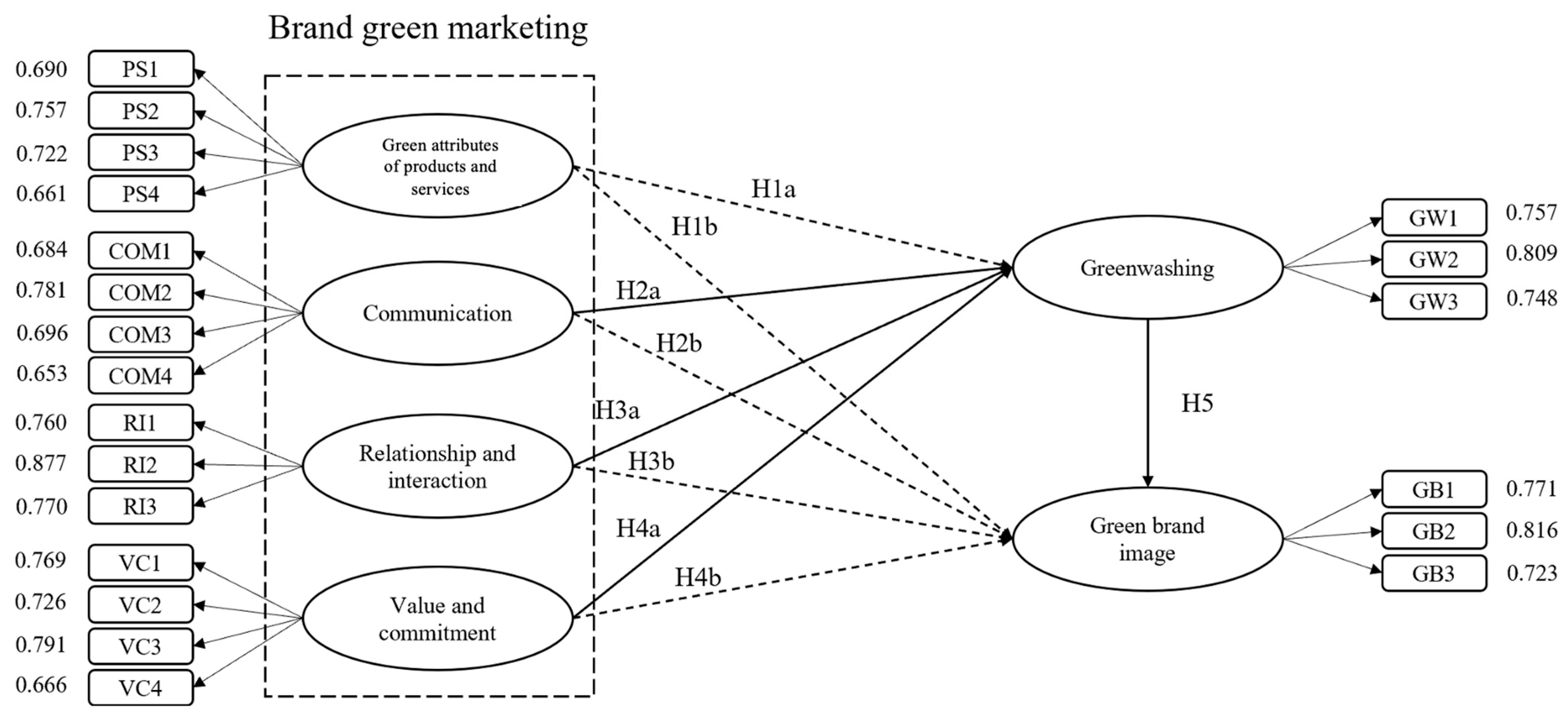

3.1. Research Framework

3.2. Expert Interviews

3.3. Questionnaire Design and Research Hypotheses

3.4. Participants

4. Results

4.1. Study 1: Exploring the Sub-Dimensions of Brands’ Green Marketing

4.1.1. Exploratory Factor Analysis

4.1.2. Confirmatory Factor Analysis (Study 1)

4.2. Study 2: Determining the Path Relationships between Influencing Factors

4.2.1. Reliability Analysis

4.2.2. Confirmatory Factor Analysis (Study 2)

4.2.3. Path Analysis

5. Conclusions and Discussion

5.1. Main Findings

5.2. Theoretical Contributions

5.3. Practical Implications

5.4. Limitations and Future Research Recommendations

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Zhou, B.; Ding, H. How public attention drives corporate environmental protection: Effects and channels. Technol. Forecast. Soc. Chang. 2023, 191, 122486. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- United Nations Environment Programme; International Resource Panel. Decoupling Natural Resource Use and Environmental Impacts from Economic Growth; United Nations Environment Programme: Nairobi, Kenya, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Škatarić, G.; Vlahović, B.; Užar, D.; Spalevic, V.; Novićević, R. The influence of green marketing on consumer environmental awareness. Poljopr. Sumar. 2021, 67, 21–36. [Google Scholar]

- Malik, C.; Singhal, N. Consumer Environmental Attitude and Willingness to Purchase Environmentally Friendly Products: An SEM Approach. Vision 2017, 21, 152–161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Papadas, K.-K.; Avlonitis, G.J.; Carrigan, M.; Piha, L. The interplay of strategic and internal green marketing orientation on competitive advantage. J. Bus. Res. 2019, 104, 632–643. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ottman, J. The New Rules of Green Marketing: Strategies, Tools, and Inspiration for Sustainable Branding; Routledge: London, UK, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Nemes, N.; Scanlan, S.J.; Smith, P.; Smith, T.; Aronczyk, M.; Hill, S.; Lewis, S.L.; Montgomery, A.W.; Tubiello, F.N.; Stabinsky, D. An Integrated Framework to Assess Greenwashing. Sustainability 2022, 14, 4431. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hameed, I.; Hyder, Z.; Imran, M.; Shafiq, K. Greenwash and green purchase behavior: An environmentally sustainable perspective. Environ. Dev. Sustain. 2021, 23, 13113–13134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Henion, K. Ecological Marketing; Columbus/American Marketing Association: Columbus, OH, USA, 1976. [Google Scholar]

- Simão, L.; Lisboa, A. Green Marketing and Green Brand—The Toyota Case. Procedia Manuf. 2017, 12, 183–194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Berhe, H.M. The Impact of Green Investment and Green Marketing on Business Performance: The Mediation Role of Corporate Social Responsibility in Ethiopia’s Chinese Textile Companies. Sustainability 2022, 14, 3883. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Majeed, M.U.; Aslam, S.; Murtaza, S.A.; Attila, S.; Molnár, E. Green Marketing Approaches and Their Impact on Green Purchase Intentions: Mediating Role of Green Brand Image and Consumer Beliefs towards the Environment. Sustainability 2022, 14, 11703. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brockhaus, S.; Fawcett, S.E.; Knemeyer, A.M.; Fawcett, A.M. Motivations for environmental and social consciousness: Reevaluating the sustainability-based view. J. Clean. Prod. 2017, 143, 933–947. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abrantes, B.F.; Ström, E. Business utilitarian ethics and green lending policies: A thematic analysis on the Swedish global retail and commercial banking sector. Int. J. Bus. Gov. Ethics 2023, 17, 443–470. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Becker-Olsen, K.; Potucek, S. Greenwashing. In Encyclopedia of Corporate Social Responsibility; Idowu, S.O., Capaldi, N., Zu, L., Gupta, A.D., Eds.; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2013; pp. 1318–1323. [Google Scholar]

- Guo, R.; Zhang, W.; Wang, T.; Li, C.B.; Tao, L. Timely or considered? Brand trust repair strategies and mechanism after greenwashing in China—From a legitimacy perspective. Ind. Mark. Manag. 2018, 72, 127–137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Y.-S.; Chang, C.-H. Greenwash and Green Trust: The Mediation Effects of Green Consumer Confusion and Green Perceived Risk. J. Bus. Ethics 2013, 114, 489–500. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pomering, A.; Johnson, L.W. Advertising corporate social responsibility initiatives to communicate corporate image. Corp. Commun. Int. J. 2009, 14, 420–439. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, R.; Tao, L.; Li, C.B.; Wang, T. A Path Analysis of Greenwashing in a Trust Crisis among Chinese Energy Companies: The Role of Brand Legitimacy and Brand Loyalty. J. Bus. Ethics 2017, 140, 523–536. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Philippe, D.; Durand, R. The impact of norm-conforming behaviors on firm reputation. Strateg. Manag. J. 2011, 32, 969–993. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Urbański, M.; ul Haque, A. Are You Environmentally Conscious Enough to Differentiate between Greenwashed and Sustainable Items? A Global Consumers Perspective. Sustainability 2020, 12, 1786. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nguyen, T.T.; Yang, Z.; Nguyen, N.; Johnson, L.W.; Cao, T.K. Greenwash and Green Purchase Intention: The Mediating Role of Green Skepticism. Sustainability 2019, 11, 2653. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiao, Z.; Wang, Y.; Ji, X.; Cai, L. Greenwash, moral decoupling, and brand loyalty. Soc. Behav. Personal. Int. J. 2021, 49, 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, L.; Li, D.; Cao, C.; Huang, S. The influence of greenwashing perception on green purchasing intentions: The mediating role of green word-of-mouth and moderating role of green concern. J. Clean. Prod. 2018, 187, 740–750. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baum, L.M. It’s Not Easy Being Green … Or Is It? A Content Analysis of Environmental Claims in Magazine Advertisements from the United States and United Kingdom. Environ. Commun. 2012, 6, 423–440. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tan, Z.; Sadiq, B.; Bashir, T.; Mahmood, H.; Rasool, Y. Investigating the Impact of Green Marketing Components on Purchase Intention: The Mediating Role of Brand Image and Brand Trust. Sustainability 2022, 14, 5939. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zameer, H.; Wang, Y.; Yasmeen, H. Reinforcing green competitive advantage through green production, creativity and green brand image: Implications for cleaner production in China. J. Clean. Prod. 2020, 247, 119119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dangelico, R.M.; Vocalelli, D. “Green Marketing”: An analysis of definitions, strategy steps, and tools through a systematic review of the literature. J. Clean. Prod. 2017, 165, 1263–1279. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, J.; Sawyer, L.; Safi, A. Institutional pressure and green product success: The role of green transformational leadership, green innovation, and green brand image. Front. Psychol. 2021, 12, 704855. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aivazidou, E.; Tsolakis, N.; Vlachos, D.; Iakovou, E. A water footprint management framework for supply chains under green market behaviour. J. Clean. Prod. 2018, 197, 592–606. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mourad, M.; Serag Eldin Ahmed, Y. Perception of green brand in an emerging innovative market. Eur. J. Innov. Manag. 2012, 15, 514–537. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bashir, S.; Khwaja, M.G.; Rashid, Y.; Turi, J.A.; Waheed, T. Green Brand Benefits and Brand Outcomes: The Mediating Role of Green Brand Image. Sage Open 2020, 10, 2158244020953156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Watson, A.; Perrigot, R.; Dada, O. The effects of green brand image on brand loyalty: The case of mainstream fast food brands. Bus. Strategy Environ. 2024, 33, 806–819. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chan, H.K.; He, H.; Wang, W.Y.C. Green marketing and its impact on supply chain management in industrial markets. Ind. Mark. Manag. 2012, 41, 557–562. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qayyum, A.; Jamil, R.A.; Sehar, A. Impact of green marketing, greenwashing and green confusion on green brand equity. Span. J. Mark.—ESIC 2023, 27, 286–305. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salhab, H.; Al-Amarneh, A.; Aljabaly, S.; Zoubi, M.; Othman, M. The impact of social media marketing on purchase intention: The mediating role of brand trust and image. Int. J. Data Netw. Sci. 2023, 7, 591–600. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jackson, D.L. Revisiting Sample Size and Number of Parameter Estimates: Some Support for the N:q Hypothesis. Struct. Equ. Model. Multidiscip. J. 2003, 10, 128–141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chin, W.W. The partial least squares approach to structural equation modeling. Mod. Methods Bus. Res. 1998, 295, 295–336. [Google Scholar]

- Fornell, C.; Larcker, D.F. Evaluating structural equation models with unobservable variables and measurement error. J. Mark. Res. 1981, 18, 39–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eisinga, R.; Te Grotenhuis, M.; Pelzer, B. The reliability of a two-item scale: Pearson, Cronbach, or Spearman-Brown? Int. J. Public Health 2013, 58, 637–642. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jeong, E.; Jang, S.; Day, J.; Ha, S. The impact of eco-friendly practices on green image and customer attitudes: An investigation in a café setting. Int. J. Hosp. Manag. 2014, 41, 10–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Walker, K.; Wan, F. The Harm of Symbolic Actions and Green-Washing: Corporate Actions and Communications on Environmental Performance and Their Financial Implications. J. Bus. Ethics 2012, 109, 227–242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, J.; Lobo, A.; Leckie, C. The role of benefits and transparency in shaping consumers’ green perceived value, self-brand connection and brand loyalty. J. Retail. Consum. Serv. 2017, 35, 133–141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Butt, M.M.; Mushtaq, S.; Afzal, A.; Khong, K.W.; Ong, F.S.; Ng, P.F. Integrating Behavioural and Branding Perspectives to Maximize Green Brand Equity: A Holistic Approach. Bus. Strategy Environ. 2017, 26, 507–520. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akturan, U. How does greenwashing affect green branding equity and purchase intention? An empirical research. Mark. Intell. Plan. 2018, 36, 809–824. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Dimension | Item | Question |

|---|---|---|

| Basic Information | A-1 | What is your name? |

| A-2 | What is your background and relevant professional experience? | |

| A-3 | What organization or institution do you currently work for? | |

| A-4 | How long have you been in your current role? | |

| Brands’ Green Marketing | B-1 | What dimensions do you believe brands’ green marketing encompasses? How should it be evaluated? |

| B-2 | How well do you think your product (or a certain product) performs in terms of green marketing? | |

| B-3 | What other aspects should be considered in brands’ green marketing? Can you elaborate (open-ended question)? |

| Code | Key Findings |

|---|---|

| A | Green brands must provide eco-friendly products with attributes like sustainable packaging and recycling, covering multiple areas. |

| B | In marketing, the environmental friendliness of a product is not limited to the product itself but extends to the entire production chain, such as using biodegradable packaging materials. |

| C | Green brands clearly communicate the features of eco-friendly products through social media and digital marketing, enhancing promotional effectiveness and expanding market reach. |

| D | Green brands ensure that their environmental marketing information is intuitive and easy to understand, conveying their environmental policies and product characteristics. |

| E | Green brands should actively participate in discussions on environmental topics on social media to increase user interaction. |

| F | Brands should find ways to ensure that consumers gain a deeper understanding of their green information and correctly interpret its meaning. |

| G | Green brands should regularly engage in multi-faceted interactions with consumers, providing feedback and responses on product information, usage, and services, to enhance consumer trust and loyalty. |

| H | Green brands lead in environmental technology innovation, continually improving product design and energy-saving technologies. They should also promote transparency in environmental policies and practices to build consumer trust. |

| I | The goal of brands’ green marketing should be to foster consumer recognition of the brand’s environmental efforts, making the brand’s products trustworthy and worthy of support. |

| Dimension | Indicator | Measurement Items |

|---|---|---|

| Green attributes of products and services | PS1 | The types and range of green products offered by the brand and their uniqueness in the market. |

| PS2 | The quality and performance of green products, such as their environmental benefits, durability, etc. | |

| PS3 | The innovation and competitive advantage of green products, i.e., the brand’s leading position in green product development. | |

| PS4 | The characteristics and quality of green services, e.g., whether the brand’s environmental services meet consumer needs and have high credibility. | |

| Communication | COM1 | The clarity of the brand’s environmental product claims and promotional effectiveness in advertisements. |

| COM2 | The clarity and accuracy of environmental marketing information, including whether the brand’s environmental policies and product features are communicated in an easily understandable way. | |

| COM3 | The level of engagement and interactivity in social media and digital marketing, such as discussions and interactions on environmental topics on social media platforms. | |

| COM4 | The awareness and understanding of the brand’s environmental information by consumers, i.e., whether consumers are aware of and correctly understand the brand’s green marketing messages. | |

| Relationship and interaction | RI1 | The frequency and depth of interactions between the brand and consumers, e.g., whether the brand regularly interacts with consumers and provides feedback and responses. |

| RI2 | The level of consumer participation in environmental activities and community projects, i.e., whether consumers actively participate in environmental activities or advocacy organized by the brand. | |

| RI3 | The trust and loyalty between the brand and consumers, including the level of consumer trust in the brand’s environmental commitments and brand loyalty. | |

| Value and commitment | VC1 | The brand’s environmental value proposition and commitment, i.e., whether the brand’s attitude and stance on environmental issues are recognized by consumers. |

| VC2 | The transparency and credibility of the brand’s environmental policies, including whether the brand openly and transparently discloses its environmental policies and practices, and the level of consumer trust in them. | |

| VC3 | The brand’s innovation and leadership in environmental protection, i.e., whether the brand is a leader in environmental technology, product design, etc. | |

| VC4 | The level of consumer recognition and identification with the brand’s environmental values, i.e., whether consumers believe that the brand’s environmental efforts are trustworthy and worthy of support. |

| Latent Variable | Measurement Item | Source |

|---|---|---|

| Greenwashing | I doubt the authenticity of the environmental information promoted by the brand. | [24] |

| I feel there is a discrepancy between the brand’s actual environmental actions and its promotion. | ||

| I hold a positive attitude toward the brand’s claimed environmental products or services. | ||

| Green brand image | The performance of the brand’s green products meets my expectations. | [36] |

| The brand’s green products align with my environmental values. | ||

| The brand demonstrates a certain level of environmental commitment in its products and marketing activities. |

| Category | Item | Number | Percentage |

|---|---|---|---|

| Gender | Male | 62 | 19.9% |

| Female | 263 | 80.1% | |

| Age | 19–29 | 55 | 26.9% |

| 30–39 | 145 | 44.6% | |

| 40–49 | 75 | 23.1% | |

| 50 and above | 50 | 15.4% | |

| Marital Status | Married | 298 | 91.7% |

| Unmarried | 27 | 8.3% | |

| Monthly Income | Below 4000 | 15 | 4.6% |

| 4001–8000 | 188 | 57.8% | |

| 8001–16,000 | 63 | 19.4% | |

| 16,001–30,000 | 31 | 9.5% | |

| Above 30,001 | 28 | 8.6% | |

| Education Level | Junior high school or below | 3 | 0.9% |

| High school or technical school | 27 | 8.3% | |

| Bachelor or associate degree | 215 | 66.2% | |

| Master’s degree or above | 80 | 24.6% |

| Indicator | Factor Loading | Communality | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Factor 1 | Factor 2 | Factor 3 | Factor 4 | ||

| PS1 | 0.066 | 0.778 | 0.087 | 0.216 | 0.664 |

| PS2 | 0.087 | 0.777 | 0.192 | 0.227 | 0.700 |

| PS3 | 0.183 | 0.726 | 0.284 | 0.119 | 0.655 |

| PS4 | 0.394 | 0.617 | 0.058 | 0.210 | 0.582 |

| COM1 | 0.757 | 0.104 | 0.025 | 0.247 | 0.646 |

| COM2 | 0.809 | 0.192 | 0.129 | 0.155 | 0.732 |

| COM3 | 0.629 | 0.188 | 0.317 | 0.193 | 0.568 |

| COM4 | 0.690 | 0.085 | 0.235 | 0.154 | 0.562 |

| RI1 | 0.149 | 0.192 | 0.785 | 0.167 | 0.703 |

| RI2 | 0.230 | 0.184 | 0.824 | 0.123 | 0.781 |

| RI3 | 0.131 | 0.113 | 0.845 | 0.139 | 0.763 |

| VC1 | 0.151 | 0.261 | 0.333 | 0.615 | 0.580 |

| VC2 | 0.344 | 0.370 | 0.078 | 0.627 | 0.653 |

| VC3 | 0.203 | 0.161 | 0.086 | 0.801 | 0.717 |

| VC4 | 0.219 | 0.178 | 0.166 | 0.815 | 0.771 |

| Factor | Item | Unstd. | Std. | z | p | S.E. | AVE | CR |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Green attributes of products and services | PS1 | 1.000 | - | - | - | 0.688 | 0.502 | 0.801 |

| PS2 | 1.024 | 0.086 | 11.877 | 0.000 | 0.757 | |||

| PS3 | 1.016 | 0.089 | 11.433 | 0.000 | 0.719 | |||

| PS4 | 0.812 | 0.076 | 10.726 | 0.000 | 0.666 | |||

| Communication | COM1 | 1.000 | - | - | - | 0.696 | 0.498 | 0.798 |

| COM2 | 1.076 | 0.088 | 12.209 | 0.000 | 0.780 | |||

| COM3 | 0.989 | 0.089 | 11.141 | 0.000 | 0.691 | |||

| COM4 | 0.912 | 0.086 | 10.548 | 0.000 | 0.648 | |||

| Relationship and interaction | RI1 | 1.000 | - | - | - | 0.757 | 0.647 | 0.845 |

| RI2 | 1.106 | 0.073 | 15.072 | 0.000 | 0.877 | |||

| RI3 | 1.050 | 0.075 | 14.022 | 0.000 | 0.772 | |||

| Value and commitment | VC1 | 1.000 | - | - | - | 0.662 | 0.547 | 0.828 |

| VC2 | 1.215 | 0.101 | 12.028 | 0.000 | 0.772 | |||

| VC3 | 1.062 | 0.093 | 11.373 | 0.000 | 0.718 | |||

| VC4 | 1.171 | 0.095 | 12.311 | 0.000 | 0.798 |

| PS | COM | RI | VC | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Products and services | 0.708 | |||

| Communication | 0.471 | 0.705 | ||

| Relationship and interaction | 0.441 | 0.448 | 0.804 | |

| Value and commitment | 0.592 | 0.568 | 0.444 | 0.739 |

| Construct | Item | Corrected Item-to-Total Correlation | Cronbach’s α after Deletion | Cronbach’s α |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Green attributes of products and services | PS1 | 0.611 | 0.748 | 0.798 |

| PS2 | 0.668 | 0.719 | ||

| PS3 | 0.618 | 0.744 | ||

| PS4 | 0.551 | 0.776 | ||

| Communication | COM1 | 0.587 | 0.753 | 0.795 |

| COM2 | 0.676 | 0.709 | ||

| COM3 | 0.592 | 0.750 | ||

| COM4 | 0.568 | 0.762 | ||

| Relationship and interaction | RI1 | 0.674 | 0.811 | 0.842 |

| RI2 | 0.755 | 0.735 | ||

| RI3 | 0.694 | 0.794 | ||

| Value and commitment | VC1 | 0.568 | 0.813 | 0.823 |

| VC2 | 0.646 | 0.778 | ||

| VC3 | 0.649 | 0.776 | ||

| VC4 | 0.73 | 0.739 | ||

| Perceived greenwashing | GW1 | 0.663 | 0.745 | 0.813 |

| GW2 | 0.692 | 0.717 | ||

| GW3 | 0.638 | 0.769 | ||

| Brand image | BI1 | 0.593 | 0.802 | 0.807 |

| BI2 | 0.715 | 0.675 | ||

| BI3 | 0.663 | 0.729 |

| Factor | Item | Unstd. | p | Std. | SMC | AVE | CR |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Green attributes of products and services | PS1 | 1.000 | - | 0.690 | 0.476 | 0.502 | 0.801 |

| PS2 | 1.022 | 0.000 | 0.757 | 0.573 | |||

| PS3 | 1.017 | 0.000 | 0.722 | 0.522 | |||

| PS4 | 0.805 | 0.000 | 0.661 | 0.437 | |||

| Communication | COM1 | 1.000 | - | 0.684 | 0.468 | 0.498 | 0.798 |

| COM2 | 1.096 | 0.000 | 0.781 | 0.610 | |||

| COM3 | 1.014 | 0.000 | 0.697 | 0.485 | |||

| COM4 | 0.934 | 0.000 | 0.653 | 0.426 | |||

| Relationship and interaction | RI1 | 1.000 | - | 0.760 | 0.577 | 0.647 | 0.845 |

| RI2 | 1.101 | 0.000 | 0.877 | 0.769 | |||

| RI3 | 1.043 | 0.000 | 0.771 | 0.594 | |||

| Value and commitment | VC1 | 1.000 | - | 0.665 | 0.443 | 0.547 | 0.828 |

| VC2 | 1.203 | 0.000 | 0.769 | 0.591 | |||

| VC3 | 1.068 | 0.000 | 0.726 | 0.527 | |||

| VC4 | 1.155 | 0.000 | 0.791 | 0.626 | |||

| Perceived greenwashing | GW1 | 1.000 | - | 0.757 | 0.573 | 0.595 | 0.815 |

| GW2 | 0.981 | 0.000 | 0.809 | 0.654 | |||

| GW3 | 0.974 | 0.000 | 0.748 | 0.559 | |||

| Brand image | BI1 | 1.000 | - | 0.723 | 0.522 | 0.594 | 0.814 |

| BI2 | 1.067 | 0.000 | 0.816 | 0.666 | |||

| BI3 | 1.030 | 0.000 | 0.771 | 0.594 |

| PS | COM | RI | VC | GW | BI | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Green attributes of products and services | 0.709 | |||||

| Communication | 0.471 | 0.705 | ||||

| Relationship and interaction | 0.441 | 0.448 | 0.804 | |||

| Value and commitment | 0.592 | 0.568 | 0.444 | 0.739 | ||

| Perceived greenwashing | −0.454 | −0.522 | −0.427 | −0.571 | 0.772 | |

| Brand image | 0.431 | 0.470 | 0.405 | 0.493 | −0.562 | 0.771 |

| Hypotheses | X | → | Y | Unstd. | SE | z | p | Std. |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| H1a | PS | → | GW | −0.049 | 0.096 | −0.513 | 0.608 | −0.046 |

| H1b | PS | → | BI | 0.084 | 0.104 | 0.805 | 0.421 | 0.074 |

| H2a | COM | → | GW | −0.322 | 0.105 | −3.082 | 0.002 | −0.268 |

| H2b | COM | → | BI | 0.225 | 0.116 | 1.934 | 0.053 | 0.178 |

| H3a | RI | → | GW | −0.162 | 0.072 | −2.257 | 0.024 | −0.151 |

| H3b | RI | → | BI | 0.094 | 0.078 | 1.196 | 0.232 | 0.083 |

| H4a | VC | → | GW | −0.498 | 0.130 | −3.836 | 0.000 | −0.393 |

| H4b | VC | → | BI | 0.075 | 0.145 | 0.519 | 0.604 | 0.056 |

| H5 | GW | → | BI | −0.450 | 0.099 | −4.563 | 0.000 | −0.429 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Tu, J.-C.; Cui, Y.; Liu, L.; Yang, C. Perceived Greenwashing and Its Impact on the Green Image of Brands. Sustainability 2024, 16, 9009. https://doi.org/10.3390/su16209009

Tu J-C, Cui Y, Liu L, Yang C. Perceived Greenwashing and Its Impact on the Green Image of Brands. Sustainability. 2024; 16(20):9009. https://doi.org/10.3390/su16209009

Chicago/Turabian StyleTu, Jui-Che, Yang Cui, Lixia Liu, and Chun Yang. 2024. "Perceived Greenwashing and Its Impact on the Green Image of Brands" Sustainability 16, no. 20: 9009. https://doi.org/10.3390/su16209009

APA StyleTu, J.-C., Cui, Y., Liu, L., & Yang, C. (2024). Perceived Greenwashing and Its Impact on the Green Image of Brands. Sustainability, 16(20), 9009. https://doi.org/10.3390/su16209009