Abstract

The sustainable development of rural tourism requires not only active participation from the government and enterprises but is also closely tied to the attitudes of local residents. This study, grounded in the theories of relative deprivation and social comparison, focuses on the residents living near the Jinshi Gorge Scenic Area in Shangluo City. We constructed a structural equation model to explore how residents’ perceptions of the social environment in rural tourism influence their sense of relative deprivation, enhance their happiness, and ultimately promote the sustainable development of rural tourism. The study’s findings reveal the following: (1) that demographic characteristics, including age, education level, and annual income, significantly influence residents’ perceptions of their social environment, particularly their sense of group identity, social support, and feelings of inequality. (2) Levels of relative deprivation vary significantly across different demographic groups. (3) There is a strong positive correlation between individual cognitive relative deprivation and individual emotional relative deprivation. Similarly, group cognitive relative deprivation positively predicts group emotional relative deprivation. (4) Experiences of discrimination, feelings of inequality, and strength of group identity emerge as significant predictors of both individual and group-level cognitive and emotional relative deprivation. (5) Social support has a significant negative effect on individual cognition, individual emotions, group cognition, and group emotional relative deprivation.

1. Introduction

The development of rural tourism is increasingly characterized by diversification, personalization, and sustainability. This diversified development model not only offers tourists a wider range of choices but also injects new vitality into the rural economy. However, alongside these positive developments, issues such as unequal tourism development and disparities in the distribution of tourism benefits have emerged. Generations of residents in tourist destinations have traditionally depended on local resources for their livelihoods, meaning that these resources are integral to their daily lives and production. However, the advent of tourism often results in the separation of these resources from local communities, with their production and lifestyle being commodified as tourism products. Despite this, residents are frequently denied the rights and benefits they deserve, leading to an objective situation where local communities are often deprived [1].

Moreover, the development and operation of tourist destinations involve complex negotiations among various stakeholders, each pursuing their own interests [2]. As one of these stakeholders, the residents of tourist destinations generally find themselves in a weaker position, with limited influence over tourism development decisions. Socio-environmental perception refers to an individual’s subjective interpretation of their surrounding environment, and this perception significantly influences residents’ attitudes and support for tourism activities. One of the key factors shaping residents’ support for tourism development is their perception of changes in the quality of their local environment. However, negative perceptions of the social environment, often stemming from challenges or inequalities brought about by tourism, can erode residents’ attitudes toward tourism. This can lead to conflict with other stakeholders, ultimately hindering the sustainable development of local tourism. Consequently, there is an urgent need for tourism research to incorporate new theoretical frameworks to address these pressing issues and challenges. The introduction of the relative deprivation theory may offer valuable insights into the attitudes and behaviors of multiple stakeholders in tourism, as well as provide a means to resolve conflicts [3].

The concept of relative deprivation (RD) originated in psychology and was first introduced by the American scholar Samuel Stouffer [4]. Over time, it has been applied across various fields, including sociology, political science, and economics. Robert K. Merton provided a comprehensive analysis of relative deprivation in his seminal work “Social Theory and Social Structure” [5]. Walter Garrison Runciman further refined the concept by identifying the following four basic conditions for the formation of relative deprivation: (1) the individual or group does not possess X, (2) they are aware that others have X, (3) they expect to obtain X, and (4) this expectation is reasonable and feasible [6]. Relative deprivation theory not only effectively explains the psychological effects experienced by vulnerable groups but also possesses strong explanatory power in various contexts. A.V. Seaton was the first to apply the concept of relative deprivation to the psychological study of residents in tourist destinations. He has argued that the “demonstration effect”—arising from contact with tourists—leads to a sense of relative deprivation among local residents. This effect is exacerbated when providing products or services to tourists results in the loss of residents’ means of production and living, while the high income of tourism practitioners further accentuates feelings of deprivation among non-participating residents [7].

In recent years, many scholars have applied relative deprivation theory to empirical research on tourist destinations, addressing topics such as its conceptualization and measurement [8,9,10], influencing factors and formation mechanisms [11,12,13], as well as its impact on attitudes and behaviors [14,15]. However, previous research on the social environmental factors influencing relative deprivation has predominantly focused on individual perspectives, such as the clarity of land and tourism resource property rights, perceptions of fairness, and subjective social class. Relative deprivation is a subjective cognitive and emotional experience that occurs when individuals or groups compare themselves to a reference group and perceive themselves to be at a disadvantage. This experience is often accompanied by negative emotions, such as anger and dissatisfaction, as individuals or groups recognize that their rights have been unfairly treated. Such subjective cognition and emotional experiences are influenced by various factors within the social environment.

In the context of tourism development, conflicts among stakeholders often expose local residents to significant disparities in income distribution, social status, quality of life, employment opportunities, and other factors. These disparities can cause residents to feel inferior to tourists and other groups, leading to dissatisfaction and a pronounced sense of relative deprivation. This sense of deprivation is a major factor contributing to conflicts both within the community and with tourists. Research has shown that such feelings of relative deprivation can foster negative attitudes toward tourism and may even result in boycotting behaviors. Furthermore, these negative attitudes and actions often escalate into concrete instances of conflict [16], such as protests, boycotts of tourism projects, or direct confrontations with tourists [17]. When residents in rural areas become aware of the higher living standards enjoyed by foreign tourists, they may experience heightened feelings of relative deprivation, which can fuel negative emotions or even opposition to tourism development [18]. It is essential to explore how perceptions of the social environment contribute to feelings of relative deprivation and to identify the specific social factors that most influence these perceptions. By implementing national policies and forms of regional governance that emphasize the equitable distribution of tourism benefits, it is possible to mitigate residents’ sense of deprivation and reduce the risk of social conflict. This study, therefore, takes the Jinshi Gorge Scenic Area in Shangluo City as a case study by which to explore the impact of social environment perception on relative deprivation among residents in tourist destinations. The research aims to identify the root causes of negative emotions among disadvantaged residents in the context of tourism development, balance the interests of various stakeholders, and promote the sustainable development of tourist destinations.

2. Theoretical Framework and Research Hypotheses

Scholars widely agree that the concept of relative deprivation is grounded in a social comparison framework. It is a subjective cognitive and emotional experience in which an individual or group perceives themselves to be in a disadvantaged position by comparing themselves with a reference group, leading to negative emotions such as anger and dissatisfaction [19,20,21]. Relative deprivation is typically categorized into individual relative deprivation (IRD) and group relative deprivation (GRD), a distinction that holds particular relevance for residents of tourism destinations. IRD refers to the dissatisfaction individuals experience when they perceive themselves as being disadvantaged—whether economically, socially, or in terms of quality of life—compared with others [22]. In tourist destinations, residents may feel personally marginalized through comparisons with wealthier tourists or more affluent groups. GRD, on the other hand, reflects the collective sense of unfairness experienced by residents as a group when comparing themselves with other groups, such as tourists or external investors [6]. This group-level deprivation is more likely to trigger collective action, including protests or boycotts of tourism projects [23].

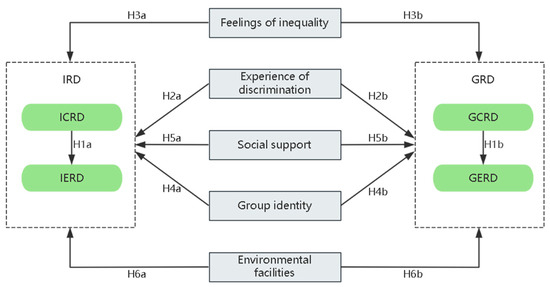

Relative deprivation arises through social comparison and involves three key psychological processes: cognitive comparison, cognitive evaluation, and the resultant emotions [22]. Pan et al. developed a theoretical model of reference and comparison among residents in tourist destinations that illustrates how individuals make reference choices, engage in social comparisons, and evaluate their relative disadvantages, which in turn influences the formation of a sense of relative deprivation [13]. The formation of relative deprivation is a complex process that unfolds in three stages: cognitive comparison, cognitive assessment, and corresponding emotional responses [21]. First, individuals compare their status with that of an externally selected reference group. They then cognitively evaluate their disadvantaged position, which ultimately leads to emotional reactions such as anger and resentment. Based on previous research and logical inference, the following hypotheses are proposed (Figure 1):

H1a.

Individual cognitive relative deprivation (ICRD) has a positive impact on individual emotional relative deprivation (IERD).

H1b.

Group cognitive relative deprivation (GCRD) has a positive impact on group emotional relative deprivation (GERD).

Figure 1.

Hypothetical model.

According to social comparison theory, perceived unfairness can lead to a sense of relative deprivation [24]. As a subjective feeling, relative deprivation is closely linked to objective environmental changes. Perceived discrimination refers to an individual’s subjective perception of bias or differential treatment based on their membership in socially recognized groups or specific personal characteristics, such as race, gender, disability, ethnic origin, immigration status, social class, or cultural background [25]. The pre-existing psychological characteristics of individuals are closely related to their perceptions and, consequently, to their assessments of their situation. For instance, Liu et al. conducted a survey on the relative deprivation of impoverished college students, finding that higher levels of perceived discrimination were associated with stronger experiences of relative deprivation [26].

In the context of tourism, residents of tourist destinations are often in a disadvantaged position when compared with other stakeholders, with significantly less influence over tourism development decisions. As a group, these residents experience varying levels of opportunity to participate in tourism and to benefit from it. Within the group, individual residents may perceive these disparities as unfair, particularly if they have fewer opportunities to participate in tourism activities. This perceived unfairness may lead to dissatisfaction with their own situation (the cognitive component of relative deprivation) and emotional responses such as anger or resentment (the emotional component of relative deprivation). Consequently, residents with fewer opportunities for participation may feel deprived and treated unfairly, and this sense of discrimination may exacerbate their feelings of relative deprivation.

The expression “not worrying about scarcity, but about inequality” reflects people’s sensitivity to social inequality. Unequal conditions can trigger a psychological process of social comparison, leading individuals or groups in lower status positions to realize that they should not be in a relatively disadvantaged situation. This recognition can further fuel feelings of anger and relative deprivation [27]. Multiple empirical studies have demonstrated that increasing economic inequality intensifies social comparison, heightens perceptions of social competition [28], and subsequently creates a “breeding ground” for relative deprivation [29,30]. If these perceived inequalities are not addressed in a timely manner, they can deepen the negative effects of relative deprivation, potentially leading to adverse outcomes such as physical illness [31]. Based on the above research findings and logical reasoning, the following hypotheses are proposed:

H2a.

The experience of discrimination has a positive impact on individual relative deprivation (IRD).

H2b.

The experience of discrimination has a positive impact on group relative deprivation (GRD).

H3a.

Feelings of inequality have a positive impact on individual relative deprivation (IRD).

H3b.

Feelings of inequality have a positive impact on group relative deprivation (GRD).

Relative deprivation theory gains further explanatory power when integrated with other psychological processes, such as social support [32] and group identity [33]. Group identity, the sense of belonging and identification with a particular group, influences social comparison processes. A strong group identity can heighten individuals’ awareness of within-group and between-group disparities. This, coupled with social comparison theory, suggests that individuals with strong group identities are more likely to engage in comparisons, potentially leading to increased feelings of relative deprivation if they perceive their group as disadvantaged [34]. For instance, Liu’s study on vocational college students demonstrated that group identity moderated the relationship between self-stigma and group relative deprivation, amplifying the negative impact of self-stigma on feelings of group deprivation [35]. These findings lead to the following hypotheses:

H4a.

Group identity positively influences individual relative deprivation (IRD).

H4b.

Group identity positively influences group relative deprivation (GRD).

Social support, encompassing emotional, informational, and material aid from one’s social network [36], can mitigate the negative impacts of relative deprivation. This support system, comprising family, friends, community, and institutions [37], reflects the overall support available to individuals within their social environment [38]. Social support provides a buffer against stress by offering emotional reassurance, practical assistance, and access to coping strategies [39,40]. This buffering effect can ameliorate negative psychological outcomes associated with relative deprivation, such as depression and anxiety [41,42]. Conversely, experiencing relative deprivation can diminish individuals’ perception of available social support and hinder their ability to access and benefit from it [43]. Based on this interplay between social support and relative deprivation, we propose the following hypotheses:

H5a.

Social support negatively influences individual relative deprivation (IRD).

H5b.

Social support negatively influences group relative deprivation (GRD).

Focusing on the tangible aspects of the social environment, the development of environmental facilities in tourist destinations can have a double-edged effect on residents’ perceptions. Residents of tourist destinations, as local hosts, can also benefit from an improved living environment and enhanced public spaces, which contribute to a greater sense of wellbeing [44]. The development of public spaces in tourist areas, such as parks, greenbelts, and other amenities, not only provides leisure and recreational spaces for tourists but also offers local residents venues for daily relaxation. These spaces allow residents to enjoy the physical and mental benefits of nature while fostering social interaction and strengthening community cohesion, which helps to alleviate feelings of relative deprivation [45]. Therefore, we propose the following hypotheses:

H6a.

Development of environmental facilities negatively influences individual relative deprivation (IRD).

H6b.

Development of environmental facilities negatively influences group relative deprivation (GRD).

3. Methodology

3.1. Research Site

The Jinshi Gorge Scenic Area is situated in the heart of Xinkailing, in the southeast of Shangnan County, Shaanxi Province, approximately 60 km from the county seat and 18 km from Jinshi Gorge Town. In 2002, the local government developed a natural ecological and cultural landscape complex to address county-level economic challenges. As part of a tourism-driven strategy, the government encouraged local villagers to participate in tourism development, aiming to establish a sustainable model for rural tourism growth.

However, several issues emerged during the development process. Conflicts arose among villagers, scenic area managers, and the government. The villagers, who found themselves at a disadvantage, received minimal compensation after relinquishing their land. This led to a loss of confidence in societal structures and significantly impacted their personal lives. As a result, dissatisfaction and protests erupted among the villagers, causing repeated conflicts with scenic area managers. These tensions not only hinder the sustainable development of the scenic area but also introduce instability to the local community.

The choice of Jinshi Gorge Scenic Area as the research site is based on four key considerations. First, the development of tourism in this region has significantly impacted the local socio-economic landscape, affecting residents’ livelihoods and income structures, while also driving population mobility and occupational changes. This dynamic environment provides a rich context for studying how individuals perceive the social environment. Second, the area around the scenic spot likely reflects a process of urban–rural integration, where stark differences in living standards and perceptions among residents can easily lead to comparisons of social inequality and, consequently, a heightened sense of relative deprivation. Furthermore, conflicts of interest that have emerged during the area’s development may have intensified these feelings of deprivation among the local population. Third, the Jinshi Gorge Scenic Area serves as a microcosm of many other rural scenic areas across China. Therefore, examining the relationship between social environment perception and relative deprivation here offers valuable insights and lessons that can be applied to similar regions. Finally, despite its location in a mountainous area, Jinshi Gorge benefits from well-developed transportation infrastructure and good accessibility, making it a practical and convenient site for conducting surveys and field research.

3.2. Research Method

Structural equation modeling (SEM) is a quantitative analysis technique used to address practical problems by analyzing the covariance matrix of variables and assessing the consistency between sample data and a theoretical model. Unlike traditional methods, such as factor analysis, path analysis, linear regression, multivariate analysis of variance, and time series analysis, SEM allows for more comprehensive analysis. It excels in validating relationships between variables through processes like model establishment, estimation, and testing. One of SEM’s key strengths lies in its ability to handle latent variables [46]—unobservable constructs that are inferred from observed variables. This makes SEM particularly advantageous for accurately estimating latent variables, revealing complex relationships, and uncovering underlying structures. Additionally, SEM enhances the accuracy of results and allows for the simultaneous analysis of multiple dependent and independent variables [47], offering an advantage when studying multi-level relationships.

In previous studies, the measurement of relative deprivation has often been based on income [48] and has been quantitatively analyzed using the Gini coefficient [49]. In the present study, however, relative deprivation is measured using a scale that considers both individual and group dimensions as well as cognitive and emotional aspects. When examining the impact of social environment perceptions on relative deprivation, some scholars have focused on single variables, such as income level or social status, and have employed regression analysis [48] to explore these relationships. However, in this study, the initial model for understanding the relationship between social environment perception and relative deprivation among rural tourism residents involves latent variables that cannot be directly measured using observable indicators. Instead, the correlation between these variables is determined through path coefficients.

Moreover, as social environment perception encompasses multiple variables, SEM is used to assess the overall influence of these relationships. Both social environment perception and relative deprivation, as latent variables, are typically measured through questionnaires, which often contain subjective questions that introduce a certain degree of error. SEM addresses this issue by explicitly isolating and estimating measurement error, thereby improving the accuracy of model estimates. Given that the data collected are usually multidimensional and involve complex causal structures, SEM is well-suited to handle the intricate relationships between latent and observed variables, making it an ideal method for analyzing such survey data.

This study employs a structural equation model to examine how perceived inequality, social support, and group identity within residents’ social environments influence the experience of relative deprivation. A questionnaire was designed to assess each dimension, and Amos software was used to analyze their interrelationships. The survey questionnaire is divided into three main sections: demographic characteristics, social environment perception, and relative deprivation assessment. The demographic section collects data on personal background, including gender, age, educational level, and annual income. The social environment perception section covers experiences of discrimination, inequality, group identity, social support, and infrastructure development. The relative deprivation measurement is adapted from established scales used in previous research [50,51]. The social environment perception scale is a self-developed instrument, refined through interviews with local residents. Respondents’ levels of agreement are measured using a 5-point Likert scale, ranging from 1 (very dissatisfied) to 5 (very satisfied).

We conducted a pre-survey of residents living within four kilometers of the Jinshi Gorge scenic area on 13 July 2023. The survey targeted local households, using a combination of door-to-door interviews and questionnaires. Based on the pre-survey results, the prepared scale was adjusted accordingly. On 30 July 2023, we conducted a second, random survey of the same population around the Jinshi Gorge Scenic Area in Shangluo City. This survey also focused on residents living within four kilometers of the scenic spot, with Jinshi Gorge as the central reference point. The survey employed a mixed-method approach, using both online electronic questionnaires and offline paper questionnaires. For elderly participants, paper questionnaires were used, and responses were recorded with the assistance of on-site staff asking questions. No incentives were offered, as prior communication with local community staff ensured smooth participation, and very few residents declined to take part.

3.3. Scale Evaluation

On 13 July 2023, we conducted a preliminary survey of residents around the Jinshi Gorge Scenic Area using both interviews and questionnaires. Based on the results, we refined the survey scale. The reliability and validity of the overall scale, as well as its subscales, were assessed using SPSS 24.0 and Amos 24.0 (Table 1). The Cronbach’s alpha coefficients for each scale exceeded 0.6, indicating satisfactory reliability. Additionally, the KMO values for each variable were greater than 0.7, and Bartlett’s sphericity test was significant at p < 0.05, confirming that the data were suitable for factor analysis.

Table 1.

Confirmatory factor analysis of questionnaire for social environment.

We conducted both exploratory and confirmatory factor analyses on the self-developed Social Environment Perception Scale (Table 1). Principal component analysis was employed to extract common factors with eigenvalues greater than 1. The five factors extracted aligned with the questionnaire structure, demonstrating good structural validity across the subscales of social environment perception.

To further assess the validity of each subscale, we examined both convergent and discriminant validity. The standardized factor loadings for each item were all above 0.4, the average variance extracted (AVE) exceeded 0.4, and the composite reliability (CR) was greater than 0.7, indicating acceptable convergent validity. Discriminant validity was tested by comparing the square root of the AVE with the correlation coefficients between variables (Table 2). The results show that the square root of each variable’s AVE was greater than its correlations with other variables, confirming good discriminant validity for the Social Environment Perception Scale.

Table 2.

Discriminant validity of perceived variables in social environment.

Finally, the model fit test (Table 3) showed that, for the absolute index, the ratio of the chi-square value to the degrees of freedom (X2/df) was less than 3, and the root mean square error of approximation (RMSEA) was less than 0.1; for the appreciation index, the comparative fit index (CFI) was 0.888, robust fitting index (RFI) was 0.903, and the incremental fit index (IFI) was 0.891; for the contracted index, the parsimony normative fit index (PNFI) was 0.557, and the parsimony comparative fit index (PCFI) was 0.564. According to the model index criteria, it can be seen that the model has a good structural validity and can be used for hypothesis testing.

Table 3.

Overall fitting coefficient table for perceived variables of social environment.

4. Results

4.1. Villagers’ Social Backgrounds and Tourism Participation

We collected a total of 215 samples, of which 203 were valid. The survey data were analyzed using SPSS software, and the descriptive statistics for the characteristics of the surveyed population are presented (Table 4). The gender distribution was relatively balanced, with males comprising 53.69% of the sample and females 46.31%. The majority of respondents were between the ages of 31 and 69, representing 87.2% of the sample. Educational attainment was predominantly at the secondary school level, with 78.82% of respondents falling into this category, indicating a relatively low overall education level. Annual incomes were mainly in the range of 30,000 to 70,000 RMB, accounting for 75.37% of the sample. Tourism income made up between 10% and 70% of the total income for 66.99% of respondents. However, a significant portion of the villagers still rely on other industries for their livelihood.

Table 4.

Statistical characteristics of samples.

4.2. The Impact of Demographic Characteristics on Social Environment and Relative Deprivation Perception

This section utilizes SPSS 24.0 to examine the impact of demographic factors, such as gender and age, on perceived inequality, social identity, discrimination experiences, and individual cognitive deprivation within the social environment. First, an independent sample t-test was conducted to analyze gender differences. The results indicate that the significance levels for perceived inequality, discrimination experiences, and individual cognitive deprivation related to group identity were all greater than 0.05, suggesting no significant gender differences in these areas. However, the significance levels for individual emotional relative deprivation and group emotional relative deprivation were less than 0.05, indicating significant gender differences in these perceptions. The table (Table 5) below shows the test of difference in perception of emotional deprivation by gender and from the results it is clear that the perception of emotional deprivation is higher in the female group than in the male group.

Table 5.

Independent sample t test of gender characteristics on various variables.

Next, a one-way ANOVA was performed to analyze the impact of age on these variables, with the results presented in Table 6. The significance levels for the effects of age on discrimination experiences, social support, environmental facility construction, and individual cognitive relative deprivation were greater than 0.05, indicating no significant age-related differences in these variables. However, the significance levels for perceived inequality, group identity, and individual emotional relative deprivation were 0.050, 0.000, and 0.000, respectively, all below the 0.05 threshold, suggesting that age has a significant impact on these variables.

Table 6.

Single factor analysis of variance of age characteristics on various variables.

To further investigate, a homogeneity of variance test was conducted for perceived inequality, group identity, and individual emotional relative deprivation, with significance levels of 0.425, 0.190 and 0.566, respectively—all above the 0.05 threshold—indicating no significant differences in variance. Subsequently, a multiple comparison analysis was performed using the least significant difference (LSD) method. The results reveal that perceived inequality scores are highest among ‘46–69 year olds’. The ranking of perceived identity scores across age groups, from highest to lowest, show that there is a positive correlation between a resident’s age and the sense of group identity, with the sense of social identity becoming stronger as the resident gets older. Additionally, the relative emotional deprivation scores for individuals aged 18–30 and 70+ age groups were higher than those for the 31–45 and 46–69 age groups.

A one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) was conducted to examine the effects of educational level and annual income on various social and psychological variables among the respondents. The analysis revealed that the significance levels for the impact of educational level on environmental facility construction and group identity were 0.566 and 0.378, respectively—both of which are greater than the conventional threshold of 0.05. Thus, no significant differences were observed in the variables of environmental facility construction and group identity across different educational levels.

However, the significance levels for inequality, discrimination experiences, social support, and group emotional relative deprivation were all below 0.05. This indicates that there are significant differences in these variables based on respondents’ educational levels. A homogeneity of variance test was also conducted, revealing that the significance levels for inequality, individual cognitive relative deprivation, group cognitive relative deprivation, and group emotional relative deprivation were all greater than 0.05, suggesting no significant variance differences among groups.

For multiple comparison analysis, the minimum significant difference method was applied. The results show that the significance levels for discrimination experiences, social support, environmental facility construction, and individual emotional relative deprivation were all less than 0.05. Consequently, Tamhane’s T2 test was used to further analyze the perceived differences in discrimination experiences and social support among groups with varying educational levels.

The multiple comparison analysis of educational levels revealed several trends. In terms of perceived inequality, respondents with “primary school and below” and “junior high school” education levels scored higher, while those with “high school or vocational school” and “college or above” education levels scored lower. For social support, the “high school or vocational school” group had higher perceived scores, whereas the “primary school and below” and “junior high school” groups had lower scores. When examining individual cognitive deprivation, the scores for the “primary school and below” and “junior high school” groups were significantly lower compared with the “high school or vocational school” and “college or above” groups. In terms of individual emotional deprivation, scores increased progressively from “elementary school or below” to “college or above”. Lastly, for group cognitive and emotional relative deprivation, the “primary school and below” and “junior high school” groups reported significantly lower scores than the “high school or vocational school” and “college or above” groups.

The one-way ANOVA results for annual income levels indicated that the significance levels for social support, individual emotional relative deprivation, and group emotional relative deprivation were all greater than 0.05. This suggests no significant differences in the perception of these variables among residents with varying annual incomes. Conversely, the significance levels for perceived inequality, discrimination experiences, group identity, environmental facility construction, individual cognitive relative deprivation, and group cognitive relative deprivation were all below 0.05. This indicates significant differences in these variables based on annual income levels. Further tests for homogeneity of variance and multiple comparison analyses were conducted to explore these differences more thoroughly.

According to the multiple comparison analysis of annual income levels, several patterns emerged. In terms of perceived inequality, respondents with annual incomes of “30,001–50,000 RMB” and “50,001–70,000 RMB” scored higher, while those earning “over 70,000 RMB” scored lower. For perceived discrimination experiences, respondents in the “10,000–30,000 RMB” group scored the highest, followed by the “30,001–50,000 RMB”, “50,001–70,000 RMB”, and “above 70,000 RMB” groups. Regarding environmental facility perception and group identity, individuals with annual incomes below 10,000 RMB scored higher, while those in other income groups scored lower. For individual cognitive relative deprivation, the highest scores were found among those earning below 10,000 RMB, with lower scores in the other income groups. Finally, for group cognitive relative deprivation, respondents in the “30,001–50,000 RMB” income group scored lower, while those in the “50,001–70,000 RMB” and “above 70,000 RMB” groups scored higher.

4.3. The Influence of Perceived Social Environment on Relative Deprivation

Structural equation models were constructed for each concept using Amos 24.0. To estimate the parameters and assess the model fit, the maximum likelihood method was employed. The results, as shown in Table 7, indicate that the chi-square to degrees of freedom ratio (CMIN/df) is 1.422. The root mean square error of approximation (RMSEA) is 0.029. Additionally, the comparative fit index (CFI), incremental fit index (IFI), and parsimonious goodness-of-fit index (PCFI) all exceed 0.8, which is within the acceptable range. These results suggest that the model fits the data well.

Table 7.

Fitness results of the structural equation model.

The structural equation model was constructed using Amos software to test the proposed hypotheses, with the results presented in Table 8. The findings indicate that individual cognitive relative deprivation has a positive effect on individual emotional relative deprivation. Similarly, group cognitive relative deprivation positively influences group emotional relative deprivation. Additionally, discrimination experiences were found to have a positive impact on all four variables: individual cognitive relative deprivation, individual emotional relative deprivation, group cognitive relative deprivation, and group emotional relative deprivation.

Table 8.

Research hypothesis results.

Furthermore, the perception of inequality also positively affects all four variables, including both individual and group levels of cognitive and emotional relative deprivation. Group identity similarly exerts a positive influence on these variables. Conversely, social support was found to have a negative impact on all four variables, suggesting that higher levels of social support are associated with lower levels of both individual and group cognitive and emotional relative deprivation. Finally, the construction of environmental facilities was shown to have a dual effect: it positively influences both individual and group cognitive relative deprivation while negatively affecting individual and group emotional relative deprivation.

5. Conclusions and Discussion

5.1. Conclusions

Residents’ perceptions of the social environment are shaped by a variety of demographic factors, reflecting complex interactions. Older villagers tend to have a stronger sense of community and a deeper connection to traditional cultural values. Their long-standing ties to the community and greater identification with traditional values influence their social environment perceptions [52], which are more focused on these cultural and communal aspects. Those with lower levels of education are more likely to perceive social inequality. These perceptions are closely tied to their annual income levels. Villagers with lower incomes are more likely to view the social environment as unfair, often attributing this perceived inequity to the unequal distribution of resources and limited opportunities [53]. There is also a significant negative correlation between annual income and experiences of discrimination: the lower the income, the stronger the perception of being discriminated against. Low-income individuals tend to have lower subjective evaluations of their social status and are more likely to feel that they have experienced discrimination. In contrast, people with higher education levels tend to have a stronger sense of social support. Higher educational attainment is often associated with broader social networks and greater adaptability, making it easier for these individuals to access social support and making them less sensitive to perceived inequality.

Perceptions of relative deprivation are influenced by various demographic factors, particularly in relation to individual and group emotional deprivation. Significant gender differences exist, with females more likely to experience emotional relative deprivation than males. Age and education level also affect perceptions of emotional deprivation on both individual and group levels. Younger individuals (18–30 years old) and older adults (70 years and above) report higher levels of emotional relative deprivation. These age groups face different life challenges and social expectations, which shape their perceptions of emotional fulfillment. Education level is inversely related to perceptions of emotional relative deprivation. Individuals with higher education tend to have stronger abilities to process information, think critically, and regulate emotions [54], all of which help reduce the sense of emotional deprivation. Educated individuals are also more adept at recognizing their emotional needs and employing effective strategies to meet those needs, thereby lowering their perceptions of deprivation. Annual income also plays a role in shaping perceptions of relative deprivation. Residents with lower income levels tend to experience greater feelings of relative deprivation. Economic hardship increases life stress and social comparisons, which in turn exacerbates perceptions of deprivation [55].

Individual cognitive relative deprivation significantly positively influences individual emotional relative deprivation, while group cognitive relative deprivation also has a notable positive effect on group emotional deprivation. Experiences of discrimination, inequality, and group identity contribute significantly to residents’ individual cognitive, affective, group cognitive, and group emotional perceptions of relative deprivation. Specifically, experiences of inequality and discrimination negatively impact residents’ cognitive and affective states, leading to heightened feelings of relative deprivation, particularly in group cognition and affect [56]. Conversely, social support exerts a significant negative effect on individual cognitive and affective relative deprivation, as well as on group cognitive and affective relative deprivation. The acquisition of social support can enhance individuals’ social identity [57] and mitigate both individual and group feelings of relative deprivation in cognitive and emotional aspects. Furthermore, the construction of environmental facilities has a significant negative impact on residents’ emotional relative deprivation, while simultaneously exerting a positive effect on residents’ cognitive relative deprivation.

In the development of rural tourism, it is crucial to prioritize the interests of vulnerable groups. Due to economic constraints or cultural backgrounds, these groups are more susceptible to feelings of relative deprivation during tourism activities [58]. To address this, the government must take an active role in guiding the process by formulating policies tailored to local conditions. This includes providing financial, technical, and other forms of support, as well as establishing robust supervisory and management mechanisms to protect the legal rights of residents, particularly those who are vulnerable. During the tourism development phase, it is essential to ensure transparency in policymaking, minimize social inequality, and foster social harmony. This can help alleviate tensions between different groups and reduce feelings of relative deprivation [59]. Furthermore, efforts should be made to strengthen education and public awareness, organize community activities, and cultivate a strong sense of community culture. By increasing residents’ participation in the development process, the experience of discrimination can be mitigated, and mutual understanding and respect between groups enhanced, thus reducing the likelihood of conflict. In addition, improving the infrastructure, tourism facilities, and public services in rural tourism areas is critical. Such upgrades not only increase visitor satisfaction but also meet the needs of local residents, thereby minimizing potential sources of conflict and promoting social harmony and stability. When economic opportunities and resources are distributed more equitably, the overall economy becomes more prosperous and stable, ultimately supporting sustainable development.

5.2. Discussion

Various factors, such as gender, education level, and annual income, significantly influence villagers’ perceptions of their social environment. As a form of subjective cognition, these perceptions are shaped by individual characteristics, aligning with the findings of prior research. Frleta found that women in rural areas often experience greater social inequality and face more constraints regarding economic opportunities, which contributes to more nuanced feelings toward tourism development [60]. Women’s social roles and family responsibilities make them particularly attuned to the long-term wellbeing and environmental sustainability of their communities. As a result, they may be more sensitive to the social and environmental challenges that tourism can bring [61]. Additionally, villagers with higher levels of education tend to exhibit stronger critical thinking skills and have broader access to information, which enhances their ability to interpret tourism development policies and market opportunities [62]. This increased access to social networks and opportunities for participation in decision-making processes can mitigate their perceptions of inequality and discrimination, leading to a more balanced view of tourism’s impact.

Differences in gender and education level contribute to variations in perceptions of relative deprivation, as individuals from diverse backgrounds process rational and emotional information in distinct ways. Low-income groups, in particular, tend to experience a heightened sense of inequality and discrimination. These villagers often face limited opportunities to participate in tourism and have less influence over decision-making processes, making them more susceptible to unequal treatment. Experiences of discrimination, perceived inequality, and group identification all play a significant role in shaping both individual and collective perceptions of relative deprivation. Research in social psychology suggests that experiences of discrimination affect not only an individual’s emotional state but may also prompt behavioral responses, including confrontation or disengagement [63]. According to social identity theory, strong group identification is often linked to intergroup polarization and stereotyping, which can influence how residents perceive the social dynamics between internal and external groups. Group identity fosters comparisons with other individuals or groups, further amplifying perceptions of unfairness and exacerbating negative emotions such as anger and hostility [64].

Social support and environmental amenities play a crucial role in mitigating individual perceptions of cognitive deprivation. Social support has a direct and positive impact on residents’ emotional wellbeing, helping to reduce negative feelings associated with relative deprivation, such as anger and helplessness, while also enabling individuals to better cope with the stress of social inequality [65]. Tourism development often leads to environmental changes, such as improved infrastructure and ecological enhancements. As tourism destinations are also the living spaces of local residents, these improvements in environmental facilities and living conditions can decrease villagers’ resistance to unequal participation in tourism activities [66], thereby alleviating their emotional sense of relative deprivation. However, the effects of environmental facility improvements on feelings of relative deprivation are complex and require further investigation. On one hand, the construction of public amenities—such as parks, green spaces, libraries, and cultural centers—can improve residents’ living environment and enhance their overall quality of life. On the other hand, not all residents benefit equally from these improvements. Some may experience significant gains, while others may feel excluded due to factors like the location of their residence, financial constraints, or limited access to these amenities. This unequal distribution of benefits can heighten feelings of disparity, potentially intensifying the sense of relative deprivation among certain groups.

While this study has made strides in exploring the relationship between residents’ perceptions of the social environment and relative deprivation in rural tourism destinations, certain limitations remain in the research content and design. Firstly, there is certainly a correlation between these data, but we cannot infer a direct causal relationship from this. Further experiments and studies are needed to understand these relationships more deeply. Residents’ perceptions of the social environment encompass a broad spectrum of factors, and this study has only selected a few key dimensions based on previous research and field investigations. Other potential factors, such as geographical location and neighborhood dynamics, require further investigation. Secondly, the research on residents’ relative deprivation in tourist destinations was conducted solely through questionnaires, capturing their perceptions at specific points in time. Future research could integrate the tourism destination life cycle theory and game theory to examine the dynamic changes in residents’ relative deprivation at different stages of tourism development. This would allow for an exploration of whether relative deprivation is a transient or long-term phenomenon and whether it accumulates or diminishes over time. Finally, the impact of perceived social environment on relative deprivation may be moderated by certain variables. Future studies could incorporate moderating variables, such as personality traits, to enhance the research framework on the influence of perceived social environment on residents’ relative deprivation in tourist destinations.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, M.W. and D.K.; methodology, Y.Y.; software, M.W.; validation, M.W.; investigation, M.W. and D.K.; data curation, M.W.; writing—original draft preparation, M.W.; writing—review and editing, Y.Y.; visualization, M.W. and D.K.; supervision, Y.Y.; funding acquisition, Y.Y. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (NSFC) under the project “Research on Spatial Characterization and Regional Effects of Policy Mobility for Rural Revitalization”, grant number 42271232.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Ethical review and approval were waived for this study, as the national law “Regulations for Ethical Review of Biomedical Research Involving Humans” does not require the full review process for data collection from adults who have adequate decision-making capacity to agree to participate.

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in the study are included in the article, further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Bao, J.G.; Yang, B. Institutionalization and practices of the “rights to tourist attractions” (RTA) in “Azheke Plan”: A field study of tourism development and poverty reduction. Tour Trib. 2022, 37, 18–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, Z.; Shi, H.; Yang, D.; Ren, X.; Cai, Y. Analysis of core stakeholder behaviour in the tourism community using economic game theory. Tour. Econ. 2015, 21, 1169–1187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pan, J.; Yang, Z. Knowledge mapping of relative deprivation theory and its applicability in tourism research. Humanit. Soc. Sci. Commun. 2023, 10, 68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stouffer, S.A. The American Soldier: Adjustment During Army Life, 3rd ed.; Princeton University Press: Princeton, NJ, USA, 1949; pp. 114–186. [Google Scholar]

- Merton, R.K. Social Theory and Social Structure, 4th ed.; Free Press: New York, NY, USA, 1957; pp. 178–211. [Google Scholar]

- Runciman, G.W. Relative Deprivation and Social Justice: A Study of Attitudes to Social Inequality in Twentieth-Century England, 2nd ed.; University of California Press: Berkeley, CA, USA, 1966; pp. 301–338. [Google Scholar]

- Seaton, A.V. Demonstration effects or relative deprivation? The counter-revolutionary pressures of tourism in Cuba. In Progress in Tourism and Hospitality Research; John and Wiley and Sons: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 1997; Volume 3, pp. 307–320. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cai, K.; Pan, J.; He, H. Interest, power and system: Causal mechanisms of social conflict in tourism. J. Sichuan Norm. Univ. 2017, 44, 48–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gong, J.; Tang, W. Relative deprivation of residents in rural tourist destinations: Scale development and empirical test. J. Tour. 2022, 37, 64–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cai, K.; Zhou, J. Evaluation of relative deprivation level of residents in rural tourism places: Index system construction and empirical research. J. Guizhou Norm. Univ. 2023, 41, 11–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, D.; Ma, Q.; Zhao, Z. A study on the antecedents and consequences of residents’ relative deprivation in rural tourist destinations: Based on an individual psychology perspective. Hum. Geogr. 2020, 35, 32–39+98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pan, J.; Yang, Z. Research on the Generation Mechanism of Relative Deprivation Sense of Residents in Tourist Destinations. J. Southwest Univ. Natl. 2022, 43, 50–57. [Google Scholar]

- Pan, J.; Yang, Z.; Cai, Y. The generative basis of relative deprivation of residents in tourist destinations: Who to choose for reference? How to compare? Hum. Geogr. 2023, 38, 164–171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, J.; Peng, J. A study of community residents’ attitudes in tourist destinations under the perspective of relative deprivation—A case study of Maolan Nature Reserve. Ecol. Econ. 2011, 2, 34–40+49. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, N.; Hsu, C.H.; Li, X. Feeling superior or deprived? Attitudes and underlying mentalities of residents towards mainland Chinese tourists. Tour. Manag. 2018, 66, 94–107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Power, S.A.; Madsen, T.; Morton, T.A. Relative deprivation and revolt: Current and future directions. Curr. Opin. Psychol. 2020, 35, 119–124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Zhang, T.; Zhao, Z.; Zhang, J.; Li, X. Influential factors of environmental conflicts in tourist places based on qualitative comparative analysis—Taking Wutai Mountain scenic spot as an example. J. Northwestern Univ. 2024, 54, 627–638. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, J.; Zhao, Z.; Liu, Y.; Li, X. Structure and Formation Mechanism of Conflict Types in Rural Tourism Communities in the Context of Scenic Village Integration—Taking Zhaoxing Dong Village as an Example. Econ. Geogr. 2022, 42, 216–224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiong, M.; Ye, Y. Relative deprivation: Conceptualization, measurement, influencing factors and effects. Adv. Psychol. Sci. 2016, 24, 438–453. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, D.; Guo, Y. Sense of relative deprivation: Wanting, deserving, and resenting the unearned. Psychol. Sci. 2016, 39, 714–719. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smith, H.J.; Pettigrew, T.F.; Pippin, G.M.; Bialosiewicz, S. Relative Deprivation: A Theoretical and Meta-Analytic Review. Personal. Soc. Psychol. Rev. 2012, 16, 203–232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smith, H.J.; Pettigrew, T.F. Advances in relative deprivation theory and research. Soc. Justice Res. 2015, 28, 1–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, Z.; Sun, B. Influential mechanism of farmers sense of relative deprivation in the sustainable development of rural tourism. J. Sustain. Tour. 2020, 28, 110–128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Festinger, L. A theory of social comparison processes. Hum. Relat. 1954, 7, 117–140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Skosireva, A.; O’campo, P.; Zerger, S.; Chambers, C.; Gapka, S.; Stergiopoulos, V. Different faces of discrimination: Perceived discrimination among homeless adults with mental illness in healthcare settings. BMC Health Serv. Res. 2014, 14, 376. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, T.; Jin, X.; Zhao, Y. Relationship between discrimination perceptions and aggression in poor college students: Chain mediation between relative deprivation and core self-evaluation. Chin. J. Clin. Psychol. 2021, 29, 1036–1044. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smith, H.J.; Pettigrew, T.F. The Subjective interpretation of inequality: A model of the relative deprivation experience. Soc. Personal. Psychol. Compass 2014, 8, 755–765. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sommet, N.; Morselli, D.; Spini, D. Income Inequality Affects the Psychological Health of Only the People Facing Scarcity. Psychol. Sci. 2018, 29, 1911–1921. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Osborne, D.; Sibley, C.G.; Sengupta, N.K. Income and neighbourhood-level inequality predict self-esteem and ethnic identity centrality through individual- and group- based relative deprivation: A multilevel path analysis. Eur. J. Soc. Psychol. 2015, 45, 368–377. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sánchez, Á.; Willis, G.B.; Jetten, J.; Rodríguez-Bailón, R. Economic inequality enhances inferences that the normative climate is individualistic and competitive. Eur. J. Soc. Psychol. 2019, 49, 1114–1127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smith, J.; Huo, Y.J. Relative deprivation: How subjective experiences of inequality influence social behavior and health. Policy Insights Behav. Brain Sci. 2014, 1, 231–238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xie, X.; Wang, Y.; Wang, P.; Zhao, F.; Lei, L. Basic psychological needs satisfaction and fear of missing out: Friend support moderated the mediating effect of individual relative deprivation. Psychiatry Res. 2018, 268, 223–228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zagefka, H.; Binder, J.; Brown, R.; Hancock, L. Who is to blame? The relationship between ingroup identification and relative deprivation is moderated by ingroup attributions. Soc. Psychol. 2013, 44, 398–407. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Q.; Yu, G. The relationship between group identity and individual mental health: Moderating variables and mechanisms. Adv. Psychol. Sci. 2016, 24, 1300–1308. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, R. The Relationship between Academic Stigma and Aggression among Higher Education Students: The Dual Damaging Effects of Group Identity and Relative Deprivation. Ph.D. Thesis, Changjiang University, Wuhan, China, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Xiao, S. Theoretical basis and research application of the Social Support Rating Scale. J. Clin. Psychiatry 1994, 2, 98–100. [Google Scholar]

- Cheng, H.J.; Zhang, C.H.; Gong, Y.H. A Review of Research on Social Support for College Students. J. Chengdu Univ. Technol. 2014, 1, 89–92. [Google Scholar]

- Sarason, I.G.; Levine, H.M.; Basham, R.B.; Sarason, B.R. Assessing social support: The social support questionnaire. J. Personal. Soc. Psychol. 1983, 44, 127–139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cobbs, S. Social support as moderator of life stress. Psychosom. Med. 1976, 38, 300–314. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kawachi, I.; Berkman, F. Social ties and mental health. Urban Health 2001, 78, 458–467. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhao, S.; Peng, L. Feeling matters: Perceived social support moderates the relationship between personal relative deprivation and depressive symptoms. BMC Psychiatry 2021, 21, 345. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, J. Research on the Relationship between Emotional Labor, Social Support, Self-Monitoring and Mental Health. Master’s Thesis, Harbin Normal University, Harbin, China, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Han, L.; Ren, Y.; Xue, W.; Gao, F. Self-esteem and aggression: Multiple mediating roles of relative deprivation and perceived social support. Spec. Educ. China 2017, 2, 84–89. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, R.; Dai, M.; Ou, Y.; Ma, X. Management Residents’ happiness of life in rural tourism development. J. Destin. Mark. Manag. 2021, 20, 100–112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mehan, A. The Affective Agency of Public Space: Social Inclusion and Community Cohesion; Walter De Gruyter GmbH Co KG: Berlin, Germany, 2024; Volume 22, pp. 256–269. [Google Scholar]

- Kline, R.B. Principles and Practice of Structural Equation Modeling; Guilford Publications: New York, NY, USA, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Byrne, B.M. Structural Equation Modeling with EQS: Basic Concepts, Applications, and Programming, 2nd ed.; Routledge: New York, NY, USA, 2013; p. 454. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gero, K.; Kondo, K.; Kondo, N.; Shirai, K.; Kawachi, I. Associations of relative deprivation and income rank with depressive symptoms among older adults in Japan. Soc. Sci. Med. 2017, 189, 138–144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yitzhaki, S. Relative deprivation and the Gini coefficient. Q. J. Econ. 1979, 93, 321–324. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Birt, C.M.; Dion, K.L. Relative deprivation theory and responses to discrimination in a gay male and lesbian sample. Br. J. Soc. Psychol. 1987, 26, 139–145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Meng, X. Relative Deprivation of Migrant Children: Characteristics, Influencing Factors and Mechanisms. Ph.D. Thesis, Fujian Normal University, Fuzhou, China, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Stets, J.E.; Burke, P.J. Identity theory and social identity theory. Soc. Psychol. Q. 2000, 26, 224–237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aiyar, S.; Ebeke, C. Inequality of opportunity, inequality of income and economic growth. World Dev. 2020, 136, 105–115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mayer, J.D.; Geher, G. Emotional intelligence and the identification of emotion. Intelligence 1996, 22, 89–113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marmot, M. Status Syndrome: How Your Social Standing Directly Affects Your Health; A&C Black: London, UK, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Florez, E.; Cohen, K.; Ferenczi, N.; Linnell, K.; Lloyd, J.; Goddard, L.; Kumashiro, M.; Freeman, J. Linking recent discrimination-related experiences and wellbeing via social cohesion and resilience. J. Posit. Psychol. Wellbeing 2020, 4, 92–104. [Google Scholar]

- McKimmie, B.M.; Butler, T.; Chan, E.; Rogers, A.; Jimmieson, N.L. Reducing stress: Social support and group identification. Group Process. Intergroup Relat. 2020, 23, 241–261. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peng, J.; Xu, C.; Jian, W. Applying relative deprivation theory to study the attitudes of host community residents towards tourism: The case study of the Zhangjiang National Park, China. Curr. Issues Tour. 2016, 19, 734–754. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, L.; Yotsumoto, Y. Conflict in tourism development in rural China. Tour. Manag. 2019, 70, 188–200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Frleta, D.S. Gender differences: Perceived tourism impacts and tourism development support. In Gender and Tourism: Challenges and Entrepreneurial Opportunities; Emerald Publishing Limited: Bingley, UK, 2021; pp. 129–148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elshaer, I.; Moustafa, M.; Sobaih, A.E.; Aliedan, M.; Azazz, A.M. The impact of women’s empowerment on sustainable tourism development: Mediating role of tourism involvement. Tour. Manag. Perspect. 2021, 38, 100–215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, L.; Chan, E.; Song, H. Social capital and entrepreneurial mobility in early-stage tourism development: A case from rural China. Tour. Manag. 2017, 63, 338–350. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schmitt, M.T. The consequences of perceived discrimination for psychological well-being: A meta-analytic review. Psychol. Bull. 2014, 140, 921. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ellemers, N.; Spears, R.; Doosje, B. Self and social identity. Annu. Rev. Psychol. 2002, 53, 161–186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Thoits, P.A. Mechanisms linking social ties and support to physical and mental health. J. Health Soc. Behav. 2011, 52, 145–161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dwyer, L. Resident well-being and sustainable tourism development: The ‘capitals approach’. J. Sustain. Tour. 2023, 31, 2119–2135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).