Abstract

This research proposes a model to assess the impacts of transformational environmental leadership and corporate social responsibility on sustainable performance with the mediating effect of competitive advantage in environmentally certified companies in Mexico. Based on a literature review, a measurement instrument was created to evaluate the variables in the model. The sample is composed of 150 certified companies from 29 states. We used factor analysis and path analysis for hypothesis testing. We observed that transformational environmental leadership facilitates the internal changes and decision-making necessary to implement corporate social responsibility practices, develop competitive advantages, and improve sustainable performance. We also observed a positive relationship between competitive advantage and sustainable performance. From a transformational environmental leadership perspective, this study is helpful for researchers, industry experts, policymakers, and managers interested in voluntary environmental certifications in emerging economies. The research model implies a way to strengthen companies’ competitive advantage and sustainable performance through transformational environmental leadership and corporate social responsibility.

1. Introduction

Currently, corporate social responsibility (CSR) and transformational environmental leadership (TEL) have acquired importance in civil society, public organizations, and companies since CSR promotes greater competitiveness and productivity [1]. Responsable [2] found that companies that adopt CSR practices notice an increase in their contribution to social welfare and improvements in brand image, work environment, and profitability. Other benefits include customer loyalty, a positive impact on attracting and retaining talent, an improved work environment, the generation of value for shareholders, and cost reduction. Ethical leadership promotes more positive behavior among customers and employees by fostering a sense of participation and collaboration in an initiative that favorably impacts society [3,4,5,6]. For employees, this translates into increased productivity and a sense of purpose. For customers, it means loyalty, as they perceive their consumption as supporting social causes. These improvements benefit companies and the country, as business growth contributes to the economy. However, “as the 21st century approaches, the business world is incessantly moving closer to an arduous and dark relationship with the forces of nature and the environment as a whole” [7] (p. 1). Assuming CSR and TEL actions in companies to mitigate their environmental impact is relevant.

The resource-based view (RBV) explains how resources and capabilities generate a competitive advantage (CA) for companies [8]. Hitt and Ireland [9] and Thompson and Strickland [10] stated that an infinite number of attributes lead to the generation of worth for a company. Esteve and Mañez [11] mentioned that each company has unique resources and capabilities that they acquire, develop, and expand over time. Later, Teece et al. [12] proposed the dynamic capabilities theory (DCT) as a critique and extension of the RBV differentiated by focusing on dynamic capabilities.

Augier and Teece [13], Kraaijenbrink et al. [14], Barney et al. [15], and Seddon [16] indicated that several concepts of resources, capabilities, and CA generate confusion about which elements and variables can be seen as resources or capabilities. The RBV and the DCT propose that resources and capabilities are sources of CA. Although the idea of abilities in both theories has been broadly conceptualized, there remains ambiguity in what qualifies as an ability. This study attempts to fill this gap in the literature by analyzing transformational environmental leadership (TEL) and corporate social responsibility (CSR) as dynamic capabilities within the DCT. The RBV addresses CA and performance, which fits our research model, which includes CA and sustainable performance (SP). Therefore, in this study, we integrate RBV and DCT as two theories that complement each other since the DCT is an extension of the RBV.

Likewise, at a conceptual level, TEL, CSR, and SP have been characterized by an extensive academic discussion regarding how these variables are defined and measured [17,18,19]. TEL has been seen as a leadership style characterized by environmental behaviors and values with a solid moral component focused on implementing continuous environmental improvement measures to preserve the planet for future generations [20,21,22,23,24,25]. CSR has been conceptualized as an active and voluntary commitment by a company to maximize the well-being of different interest groups and contribute to the development of society [26,27]. Finally, SP has been analyzed as those achievements of the company that concern stakeholder expectations, mainly in the economic, environmental, and social aspects that determine growth and long-term success [28,29,30,31].

In addition to the above, companies are currently pressured to integrate environmental and social processes due to growing environmental, social, and economic uncertainties [32]. This widespread pressure leads companies to become more sustainable [33], seeking CA to obtain SP by implementing environmental and social strategies, such as TEL and CSR. In the literature, there is little research focused on the relationship between TEL and performance [19]. This also occurs academically in the relationships between TEL, CSR, and CA. Therefore, this research also contributes to a more comprehensive and nuanced analysis of these variables.

Pacto Global Red Mexico (Global Compact Mexico Network) [1] found that companies with environmental certifications responded better to the COVID-19 pandemic than those without certifications. Therefore, TEL and CSR allow organizations to obtain the capabilities required for facing critical situations. In 2018, PROFEPA (Procuraduría Federal de Protección al Ambiente) [Federal Attorney for Environmental Protection] [34] indicated that certified companies generate savings in electricity, better handle special waste, and reduce carbon dioxide emissions, water use, and solid waste. These savings and decreases led to improved SP. Likewise, the actions related to TEL and CSR benefited the company by obtaining a CA that improved SP. These results showed that more research into voluntary environmental certification processes is required.

Various authors have argued that dynamic capabilities cause the creation of value and CA [12,35,36,37,38,39]. Wilden et al. [40] proposed in their model that dynamic capabilities affect performance; however, they emphasized that more research is necessary, mainly focused on the relationship between dynamic capabilities and performance through CA. Also, Hefalt et al. [41] and Fainshmidt et al. [42] mentioned that these relationships require further investigation. For this reason, we address the following research question: How do TEL and CSR as dynamic capabilities relate to CA and SP in environmentally certified companies?

The rest of the paper is organized as follows: Section 2 presents the literature review, research model, and hypotheses. Section 3 explains the research method and data analysis. Section 4 presents the results. Section 5 discusses the findings and highlights the contributions and implications of the research. Finally, Section 6 offers conclusions, limitations, and recommendations for future research.

2. Literature Review and Hypotheses Development

2.1. The Resource-Based View (RBV) and the Dynamic Capabilities Theory (DCT)

The RBV explains that companies are a set of resources, capabilities, and competencies that generate CA. Strategic capabilities must be valuable, unique, or rare and difficult to imitate or replace [12,35,43]. In the DCT, dynamic capabilities are described as “the company’s ability to integrate, build, and reconfigure internal and external competencies to address rapidly changing environments” [12] (p. 515).

The TEL is characterized by its environmentally friendly processes and organized systems for sustainable implementation and continuous improvement, which add value to the market [7,21]. The rarity and difficulty of imitation occur through the vision of managers in articulating strategies, decision-making, and actions within the company [13]. Lippman and Rumelt [44] and Teece [37] concluded that dynamic capabilities must be difficult to replicate and imitate because they have the characteristics of managers as a starting point. According to Teece [45], leadership is a principal element in a company’s dynamic capabilities. Teece [36] also mentioned that management skills are critical among these capabilities because they allow opportunities to be seized. For this reason, in this study, TEL is analyzed as a dynamic capability. As a dynamic capacity, TEL denotes the company’s ability to make decisions, commit, and adapt to current social and environmental problems through continuous improvement. In this sense, the decisions and the level of commitment of a company have an impact on improvements in the performance of the company.

CSR is “the active and voluntary contribution to social, economic, and environmental improvement by companies to improve their competitive situation, value, and added value” [46]. CSR is related to the strategies and operations of the firm. Navas [47] defined strategic capabilities as those organizational skills that facilitate and improve the development of an activity within the company. CSR is seen as a capacity that allows obtaining CA [8,48]. This study analyzes CSR as a dynamic capability due to the adaptation processes involved in implementing it within a company and the unique way it performs depending on the business line, organization, leadership, and other aspects of the firm. Teece [36] mentioned that dynamic capabilities adapt to changing environments. CSR can be characterized as seizing, sensing, and reconfiguring due to adaptation to the company context.

Subsequently, Teece [36] mentioned that dynamic capabilities allow a firm to sustain higher performance over time in a changing and highly competitive market. In this scenario, an integral development of the company is reflected in its performance and CA [12]. CA derives from implementing a strategy that generates value for the market and the company [8]. Porter [49] referred to the fact that CA and strategic recognition tools are differential causes in performance between companies in the same sector. For this reason, dynamic capabilities are tied to CA and SP.

We use RBV and DCT together because they complement each other when considering that the strategic resources and capacities proposed by Barney [8] must be seen as dynamic capacities, according to Teece [12], especially in highly changing business environments. This is Teece’s critique of Barney’s work. Also, the combination of both theories is conducted to establish how these dynamic capabilities lead to obtaining a CA and improving the performance of companies. Both Barney [8] and Teece [12] explored and explained how companies in changing environments can obtain CA that leads to improved company performance.

2.2. Transformational Environmental Leadership and Corporate Social Responsibility

Pucheta-Martínez and Gallego-Álvarez [50] examined the effects of the stance of the chief executive officer (CEO) on CSR in 13,178 international firms from 39 countries. These authors showed that the CEO’s stance positively impacts CSR. Budur and Demir [51] studied which type of leadership is most effective in CSR practices with a sample of 197 employees of private corporations in Kurdistan, Iraq. The findings indicated that ethical leadership plays a crucial role in CSR. Saha et al. [52] investigated ethical leadership and CSR, highlighting that ethical leadership directly and positively impacts CSR. Ahsan [53] studied how financial performance and CSR are affected by the relationship between organizational culture and transformational leadership in the Italian manufacturing sector. The author suggested a favorable and substantial relationship between transformational leadership and CSR. For this reason, the following hypothesis is proposed:

H1.

Transformational environmental leadership (TEL) positively affects corporate social responsibility (CSR).

2.3. Transformational Environmental Leadership and Competitive Advantage

López-Cabrales et al. [54] indicated that dynamic capabilities generate competitive advantages for companies in the manufacturing sector in Spain. So, TEL, as a dynamic capability, also generates CA. In this sense, López-Cabrales et al. [54] argued that leadership leads to CA because managers realize that the proper management system generates CA and business success. For their part, Chen et al. [55] found in a study with 252 companies from Science Park in Southern Taiwan that transformational leadership positively affects sustained CA. These authors proved that “leadership and execution play a fundamental role in the value proposition and the creation and delivery of value to the system” [55] (p. 13), which generates CA. Hussein et al. [56] investigated the relationship between digital leadership and sustainable competitive advantage in 323 companies in the tourism sector in Saudi Arabia. The findings showed that digital leadership positively affects sustainable competitive advantage. Regarding the above, the following hypothesis is proposed:

H2.

Transformational environmental leadership (TEL) positively affects competitive advantage (CA).

2.4. Corporate Social Responsibility and Competitive Advantage

Tien and Hung Anh [57] conducted four industry case studies in Vietnam with companies well known for implementing CSR strategies. These authors found that the implementation of CSR strategies generated CA. Ratnawati et al. [58] analyzed the mediation of CSR in the relationship between innovation and learning orientation, performance, and CA with a sample of 198 small- and medium-sized enterprises (SMEs) in Indonesia. The results showed that CSR influences CA in a positive and significant way. Shah and Khan [59] found that customer perceptions of CSR directly and positively influence effective and continuous commitment in the banking industry with a sample of 360 respondents from Pakistan. Long-term customer loyalty generated by CSR implemented in the company consequently provides a sustainable CA. Eyasu and Arefayne [60] examined the relationship between the CSR commitment (from the perspective of four different stakeholders, customer, employee, community, and environment) and the CA strategy of the banking industry. Using data from 28 branches of Lion International Bank in Ethiopia, these authors found a positive influence on the bank’s CA. Sigit et al. [61] analyzed the connection between intellectual capital, CSR, business performance, and competitive advantage, considering the mediating role of business performance from a sustainability perspective. With a sample of 60 pharmaceutical companies in Indonesia, Malaysia, and Singapore, these authors found that CSR significantly impacts CA. Taking into account the above information, the following hypothesis is proposed:

H3.

Corporate Social Responsibility (CSR) positively affects competitive advantage (CA).

2.5. Transformational Environmental Leadership and Sustainable Performance

Research in environmental management has shown that TEL provides diverse benefits for a company that implements it. In this sense, Pan and Tian [62] conducted a study in 224 agricultural companies, finding a positive relationship between environmental leadership and environmental organizational culture, green organizational identity, and corporate green innovation performance. Chang et al. [63] found that transformational leadership affects the quality of service in the hotel sector in Taiwan. These authors found that an improvement in the quality of service leads to a positive impact on performance because by improving the quality of service, there is a greater probability that the customer will return and recommend the company. Su et al. [19] found that environmental leadership positively and significantly influences environmental and economic performance in 353 agricultural companies in China. Dey et al. [64], with information from 327 employees from various industrial sectors in Bangladesh, showed that ethical leadership ultimately affects sustainable performance and influences the voluntary environmental behavior of employees. Ledi et al. [65] examined the relationship between green transformational leadership and environmental performance in 306 manufacturing firms in Ghana. They found that green transformational leadership is positively and significantly related to environmental performance. Therefore, the following hypothesis is proposed:

H4.

Transformational environmental leadership (TEL) positively affects sustainable performance (SP).

2.6. Corporate Social Responsibility and Sustainable Performance

Abbas et al. [66] investigated the relationship between CSR and sustainable performance, moderated by social media marketing strategies in 548 Pakistani firms. The results showed that CSR positively impacts sustainable performance.

Orazalin and Baydauletov [67] examined how environmental and social performance is affected by CSR and board gender diversity in European industries. These authors found that more effective CSR strategies improve environmental and social performance. Anser et al. [68] found that CSR involvement significantly predicts social and environmental performance. This study analyzed the relationship between CSR engagement and involvement with environmental performance with a sample of 324 hotel and tourism unit managers. Malik et al. [69] conducted a study in 150 companies in the manufacturing sector where they analyzed the relationship between green human resources management, CSR, and SP mediated by organizational citizenship behavior. The results indicated that SP (social and environmental) is positively and significantly linked to CSR. Le [70] examined the relationship between CSR and SP in SMEs in an emerging economy with a sample of 469 respondents. Villena and Quinteros [71] emphasized that the company’s improvement of the environment can be explained by its CSR adoption. They found that CRS positively and significantly affects sustainable business performance. Ahsan [53] found that CSR significantly and positively correlated with financial performance in the Italian manufacturing sector. With the information collected, the following hypothesis is proposed:

H5.

Corporate social responsibility (CSR) positively affects sustainable performance (SP).

2.7. Competitive Advantage and Sustainable Performance

Sihite [72] explained that CA affects SP in companies. This author used a sample of 43 managers in Indonesia’s building automation systems industry. Yang et al. [73], using a sample of 319 companies in Pakistan, found that CA positively and significantly impacts performance. Do and Nguyen [74] investigated the links between proactive environmental strategies, CA, and company performance in 232 companies in Vietnam. These authors found that the proactive environmental strategy generates a CA, which causes improvements in the performance of the company in the short term. Cahyono et al. [75] found that CA positively impacts the performance of SMEs in Indonesia. Shebeshe et al. [76] studied how sustainable supply chain management influences competitive advantage and organizational performance in 221 manufacturing industries in Ethiopia. The relationship between competitive advantage and organizational performance shows a strong positive correlation. Based on these research findings, we propose the following hypothesis:

H6.

Competitive advantage (CA) positively affects sustainable performance (SP).

2.8. Relationship between Transformational Environmental Leadership and Sustainable Performance through Competitive Advantage

Do and Nguyen [74] studied the links between proactive environmental strategy, competitive advantages, and company performance in 232 sustainable companies in Vietnam. These authors found that a proactive environmental strategy generates competitive advantages that improve performance. Nguyen et al. [77] examined a sample of 182 information technology SMEs in Vietnam and found that business leadership improves company performance through mediating variables such as dynamic capabilities and CA. Tan et al. [78] assessed the mediating role of CA and the relationship between environmental strategy and awareness with performance (environmental and financial) in 240 manufacturing SMEs in Bangladesh. They found that CA and environmental performance are strongly affected by the environmental strategy. With the information collected, the following hypothesis is proposed:

H7.

Transformational environmental leadership (TEL) positively affects sustainable performance (SP) through competitive advantage (CA).

2.9. Relationship between Corporate Social Responsibility and Sustainable Performance through Competitive Advantage

Porter [49] stated that CA is a source of performance. Han et al. [79] showed that CSR results in obtaining sustainable CA. Valdiansyah and Augustine [80] mentioned that CSR stimulates the company to obtain a lasting competitive benefit. Therefore, the literature infers that CSR lays a solid foundation for competitiveness and organizational performance [80]. Hang et al. [81] found that CA has a mediating role between CSR and organizational performance in SMEs in Pakistan. Sigit et al. [61] found that CSR, green competitive advantage, and firm performance are related to each other in 60 pharmaceutical companies in Southeast Asia. With this information, the following hypothesis is formulated:

H8.

Corporate social responsibility (CSR) positively affects sustainable performance (SP) through competitive advantage (CA).

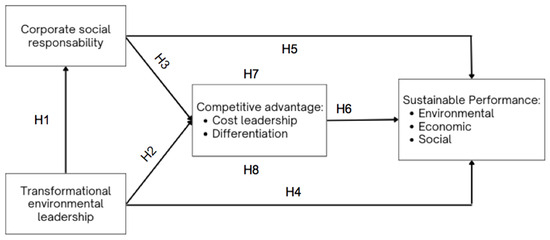

Based on the literature review, the following research model is proposed (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Research model. Source: elaborated by the authors.

3. Methodology

3.1. Research Design

This quantitative research uses a cross-sectional and instrumental variable design, with structural equation modeling for hypothesis testing.

3.2. Study Setting

The study population is PROFEPA’s environmentally certified companies located in Mexico. The database considered companies with current certification in 2023, 338 companies that could be accessible via email. The unit of analysis is the environmentally certified companies. The unit of response is the manager in charge of the voluntary environmental certification granted by PROFEPA.

3.3. Sample and Procedure

The sampling technique is probabilistic, considering a finite population. The following parameters were used to determine the sample size: target population of 338 (25% north, 45% center, and 30% south), margin of error 5%, confidence level 95%, probability of occurrence of an event 50% and likelihood of non-occurrence 50%. The sample size was 150 certified companies. The data were collected online (accessed on 15 April 2023). As suggested by PROFEPA, it was decided to exclude from the study the mining companies, CFE (Comisión Federal de Electricidad) [Federal Electricity Commission], and PEMEX (Petróleos Mexicanos) [Mexican Oil].

3.4. Data Collection

The questionnaires were emailed, and the PDFiller service was used for data collection. Three hundred and thirty-eight questionnaires were distributed, and one hundred and fifty complete questionnaires were obtained.

3.5. Validity and Reliability of the Data

Validation was conducted through evidence based on test content and evidence based on internal structure. Evidence-based test content is characterized by using previous studies with specific dimensions of the constructs. When available, scales from the literature were used to develop items tailored for PROFEPA’s environmentally certified companies in Mexico (specifically and only in the case of sustainable performance; see Appendix B). The items of the instrument are mentioned in Appendix A. Analysis of the internal structure offers evidence of how the individual elements relate to each other and, thus, how they fit into the intended constructions. For this, confirmatory factorial analysis was carried out using EQS 6 software for multivariate analysis. All measurement models were assessed according to the fit indicators provided by the software, especially looking for a non-significant p-value (p > 0.05) for the chi-square test. Reliability was assessed using Cronbach’s alpha. All the constructs showed good reliability coefficients, with Cronbach’s alpha between 0.705 and 0.972.

3.6. Measurement of the Variables

3.6.1. Transformational Environmental Leadership

TEL is characterized by continuous improvement behaviors and environmental values with a strong morale focused on preserving and conserving the planet’s resources for future generations. The items in this scale were developed from previous studies [82,83]. The results of the confirmatory factor analysis are shown in Table 1.

Table 1.

Transformational environmental leadership. Factor loadings for the first- and second-order factors.

3.6.2. Corporate Social Responsibility

CSR is characterized by seeking to maximize the well-being of both the company and its stakeholders through an active and voluntary commitment to achieve the development of society. The items in this scale were developed from previous studies [84,85,86,87,88]. Confirmatory factor analysis results are shown in Table 2.

Table 2.

Corporate social responsibility. Factor loadings for the first- and second-order factors.

3.6.3. Competitive Advantage

CA is one of those unique, rare, and difficult-to-imitate strategies that generate value for the market and the company, positioning it in a more profitable situation than its competitors and/or surpassing them. The items in this scale were developed from previous studies [89,90,91]. Confirmatory factor analysis results are shown in Table 3.

Table 3.

Competitive advantage. Factor loadings for the first-, second-, and third-order factors.

3.6.4. Sustainable Environmental and Social Performance

Sustainable environmental performance and sustainable social performance are those environmental and social business achievements that support the long-term growth and success of the company. The items in this scale were developed from previous studies [64,92,93,94]. Confirmatory factor analysis results are shown in Table 4. Although the social and environmental dimensions of sustainable performance were confirmed, this was not the case for the economic dimension of sustainable performance. In this case, a second-order structure was rejected by the data. This can be explained because sustainable performance is not a reflective variable but a formative one. Consequently, the environmental and social dimensions of sustainable performance were used separately as two first-order factors in the statistical analyses. So, we named these factors as environmental sustainable performance (ESP) and social sustainable performance (SSP), respectively.

Table 4.

Sustainable performance. Factor loadings for the first-order factors.

4. Results

4.1. Sample Characteristics

The demographic characteristics of the sample were separated into two parts: employee and organizational profiles. Regarding the organizations, 90% had been in operation for more than 10 years; 63% had more than 2000 employees; 45% were in the states of the Center of Mexico, 30% in the South, and 25% in the North; 77% were in transformation, 20% in commerce and services, and 3% in tourism; and 47% had the clean industry certification, 13% the environmental quality certification, and 1% the environmental tourism quality certification. Regarding the respondents, 59% are males, 40% females, and 1% others. A total of 45% were between 18 and 38 years old, 32% were between 38 and 48 years old, and 23% were more than 48 years old. In terms of tenure, 71% had been working in the company for five years or less. As for education, 67% had at least a bachelor’s degree, and 27% had postgraduate education.

4.2. Data Analysis

Factor analysis and path modeling with instrumental variables were used in this research.

4.3. Statistical Analysis

The previous factor analysis allowed averaging the composition item values to determine the factor scores. The use of full structural models for hypothesis testing was ruled out because the sample was relatively small. For this reason, path analysis was chosen to evaluate the hypotheses using factor scores. Path analysis allows for simultaneous estimation of the direct and indirect effects of the variables in the model. The instrumental variables (intrinsic motives of TEL and institutional coordination) were introduced to purge the model from potential endogeneity of TEL, reverse causality, omitted variables, and common method bias to obtain consistent estimates [95]. Intrinsic motives of TEL and institutional coordination were included as instrumental variables because they are truly exogenous to the model and significantly explain the independent variable TEL (β = 0.287, p < 0.003).

4.4. Hypotheses Testing

Table 5 shows evidence of convergent and discriminant validity, where the square root of the average variance extracted (AVE) of each of the five first-order factors exceeds the bivariate Pearson correlations of that factor with the others [96].

Table 5.

Square root of the average extracted variance (AVE) and bivariate Pearson correlations.

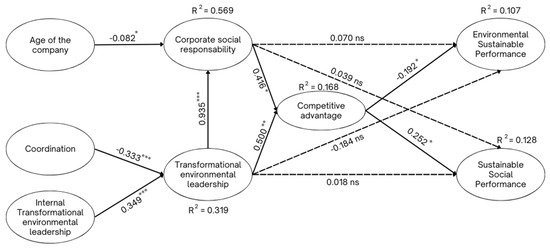

The path model was run in EQS software with the following acceptable fit indices [97]: chi-square = 15.54 with 23 degrees of freedom; p > 0.87; CFI = 1.000; and RMSEA = 0.000. Table 6 shows non-standardized (B) and standardized (b) coefficients for all paths that have direct and indirect effects in the model, while Figure 2 shows standardized coefficients (β).

Table 6.

Path analysis results.

Figure 2.

Research model with standardized coefficients (β) for the direct effects. Source: elaborated by the authors. * p < 0.05, ** p < 0.01, *** p < 0.001.

4.5. Hypothesis Testing Results

In Table 7, the hypothesis testing results are explained in terms of the significance of the direct and indirect effects as follows:

Table 7.

Hypothesis testing.

5. Discussion

This study analyzes the relationships between transformational environmental leadership and sustainable performance through dynamic capabilities and competitive advantage in PROFEPA’s environmentally certified companies. In the following paragraphs, the results of the hypothesis testing are developed.

First, in line with previous research [50,51,52,53], this study empirically establishes a positive association between TEL and CSR (H1). This result suggests that TEL facilitates internal changes in companies through decision-making focused on environmental care, improving the implementation of CSR practices. RBV and DCT support the argument that TEL influences CSR (both dynamic capabilities). TEL directs the implementation of environmental and corporate social responsibility actions. This finding is in harmony with those of previous studies on TEL and CSR carried out by Pucheta-Martínez and Gallego-Álvarez [50] in international companies from 39 countries and with those of Budur and Demir [51] in the Kurdistan region of Iraq, emphasizing that this relationship can be observed in emerging countries.

Second, a positive relationship is observed between TEL and CA (H2), as well as a positive indirect effect on CA through CSR, in line with previous research. López-Cabrales et al. [54], Chen et al. [55], and Hussein et al. [56] found a positive relationship between TEL and CA. This result suggests that TEL plays a fundamental role in generating and delivering value to the system by constantly seeking to care for the natural environment. RBV supports this finding and shows that TEL, seen as a resource, generates a competitive advantage. The findings are in harmony with previous studies on TEL and CA carried out by López-Cabrales et al. [54] in Spain and Chen et al. [55] in Taiwan, emphasizing that these relationships can be observed in emerging countries.

Third, it is observed that CSR positively affects CA (H3), as shown in previous research. Tien and Hung Anh [57], Ratnawati et al. [58], Shah and Khan [59], Eyasu and Arefayne [60], Bhuiyan et al. [98], and Sigit et al. [61] observed that CSR positively affects CA. For this reason, CSR is characterized by unique organizational skills dependent on the company that facilitates and improves the development of an activity within it, which motivates constant improvements in CA. DCT supports that dynamic capabilities generate competitive advantage, which frames that CSR is seen as a dynamic capability that leads to CA. Our findings are in line with those of previous studies on CSR and CA conducted by Tien and Hung Anh [57] in Vietnam, Ratnawati et al. [58] in Indonesia, Shah and Khan [59] in Pakistan, Eyasu and Arefayne [60] in Ethiopia, Bhuiyan et al. [98] in Bangladeshi organizations, and Sigit et al. [61] in Indonesia, Malaysia, and Singapore.

Fourth, a positive association between TEL and SP is observed (H4); however, we adapted the model because we could only measure two dimensions (social and environmental) of sustainable performance. TEL has no direct effect on social or environmental sustainable performance. However, TEL has a positive indirect effect on social sustainable performance. Our results show more broadly the benefits of TEL in SSP, maybe because this leadership is characterized by a strong moral component focused on preserving resources for future generations, which leads the company to implement strategies that positively affect social sustainable performance. However, Foo et al. [99] did not find a direct relationship between leadership and sustainable performance in manufacturing firms in Malaysia. Perhaps this contradictory result happened because they only studied manufacturing companies, and they did not necessarily have environmental certification. Riva et al. [100] and Ledi et al. [65] found a direct and positive impact between TEL and environmental performance, the former in hotels in Bangladesh and the latter in manufacturing firms in Ghana. Maybe this difference arises due to the context, which has been strongly criticized for its environmental impact.

Fifth, similarly, in testing H5, CSR shows no direct effect on social or environmental sustainable performance. However, CSR has a positive indirect effect on SSP and a negative indirect effect on ESP. Our results coincide with those of Orazalin and Baydauletov [67], Sarwar et al. [101], and Ahsan [53], who found a positive influence between CSR and SSP. CSR helps to improve practices to benefit stakeholders and improve the image of the company to obtain better social performance for the business. In the case of CSR and ESP, our results show a negative relationship, maybe because the main focus of CSR is directed to the social part, leaving aside the environmental part.

Sixth, H6 is accepted, CA has a positive direct effect on SSP and a negative direct effect on ESP. Our results coincide with previous research by Cahyono et al. [75], who found a positive relationship between CA and performance. In opposition to our results, Waqas et al. [102] found a positive relationship between CA and ESP in manufacturing companies in China. This can be due to the differences in context and sectors. Additionally, it is possible that the companies located in Mexico do not perceive CA as linked to a continuous improvement process.

Finally, H7 is accepted, TEL has a positive indirect effect on social sustainable performance through CA. Previous research, such as that of Nguyen et al. [77], has shown that leadership improves company performance through CA. Also, H8 is accepted, CSR has a positive indirect effect on SSP and a negative indirect effect on ESP through CA. Waqas et al. [102], Hang et al. [81], and Sigit et al. [61] considered the impact of CSR on performance. However, these studies do not take into account the effect of CA on these relationships according to the RBV and DCT because dynamic resources and capabilities generate CA that influences performance. The arguments of Barney [8] and Teece [45] support a relationship between TEL and SP (seen as SSP and ESP) through CA. Both theories support the relationship between CSR and SP through CA.

5.1. Theoretical Implications

This research highlights how resources and dynamic capabilities lead to CA and impact the outcomes of the company. The first implications consist of observing positive associations between a resource (TEL) and a dynamic capability (CSR). For this reason, both theories, RBV and DCT, complement each other. Although some research has addressed this relationship [50,51,52], our study delves into what can be seen as a resource and a dynamic capability and the close relationship that exists between both elements. Our findings reinforce the idea that managerial competencies are key to triggering the dynamic capabilities of companies [1,30,40]. Thus, TEL affects dynamic capabilities such as CSR through decision-making and actions.

The second implication is derived from the observed relationship between resources, dynamic capabilities, and competitive advantages raised by uniting the RBV and the DCT. Although some authors support this [54,55], our findings reinforce the idea that the relationship between a resource and a competitive advantage can occur indirectly through a dynamic capability. For this reason, the TEL consists of managerial competencies that determine the actions to follow for dynamic capabilities such as CSR. CSR is a capability characterized by seizing, sensing, and reconfiguring that generates competitive advantage in changing environments [8,37,48]. As Barney [8] suggested, the combination of resources and capabilities provides a competitive advantage to the company.

The third implication underlies how resources and dynamic capabilities can influence performance through competitive advantage. Barney [8] proposed that the resources and capabilities that are leveraged to create competitive advantages, in turn, cause improvements in the company’s performance. Our findings on how TEL influences SSP through CA, likewise how CSR influences SSP and ESP through CA, allow us to reinforce the idea that these relationships lead to improvements in company performance. Although one of the relationships was found to be negative (CSR and ESP through CA), this may occur due to the lack of long-term vision of how social responsibility actions can impact the environment.

Finally, the use of both theories is proposed for future research to analyze dynamic elements such as CSR, which is directed by the leader’s decision-making. Likewise, it is important to consider that companies are in constant change, so it is important to keep dynamic capabilities in mind as an important element in strategy adaptation.

5.2. Practical Implications

One of the practical implications of this research is to demonstrate how having TEL and CSR generates a competitive advantage for the company, which can be an incentive for companies without certification to join PROFEPA’s National Environmental Audit Program. The second contribution is that the age of the company leads to visualizing the opportunities and advantages that are obtained by having an environmental certification, as well as TEL and CSR actions. For this reason, it is emphasized that the implementation of environmental actions helps companies develop a CA in the long term. The third contribution is that the environmental focus of the CEO/Manager/Owner of the company influences companies to take actions with an environmental focus and obtain voluntary environmental certifications. Likewise, employees can be influenced by the leader to change their mentality, which leads companies to have a competitive advantage. Finally, this research provides elements from a business and social point of view that encourage companies to join the certification processes provided by the government to improve sustainability. In the future, these contributions can help companies be aware of the fact that by carrying out environmental and social actions, they can contribute to a better society.

6. Conclusions

This study offers empirical evidence of the influence of TEL and CSR in environmentally certified companies in Mexico. Specifically, it delves into the effects of TEL and CSR that lead to generating competitive advantage, which has repercussions on social and environmental performance.

Our findings highlight the fundamental role of TEL in companies with environmental certification, illustrating its profound impact in guiding the implementation of both environmental and social actions. Based on RBV and DCT, our research suggests that resources influence dynamic capabilities and together generate competitive advantage, which affects the social and environmental performance of companies. This finding is reinforced by the observed relationships between the variables in the research model since TEL is seen as a resource, CSR as a dynamic capability, and CA as a competitive advantage. Interestingly, TEL is related to SSP through CA, which coincides with what was proposed by Nguyen et al. [77], who showed that leadership improves company performance across CA. On the other hand, the relationship established between CSR and SP (divided into the ESP and SSP) through CA shows a positive relationship with the SSP and a negative relationship with the ESP. This result can probably suggest that companies do not perceive how CSR can positively influence ESP, but they do observe it with SSP. By analyzing the intricate relationships between TEL, CSR, CA, SSP, and ESP, this study increases our theoretical understanding of the leader’s influence on implementing environmental and social actions that lead to competitive advantage to generate improvements in company performance. In addition, it provides useful information to encourage companies to undertake the voluntary environmental certification process.

Limitations and Future Research

One of the limitations of our research is that it is a cross-sectional study, so the possibility of carrying out an analysis of the relationship between variables over time is suggested. Secondly, the sample is composed of companies with current certification given by PROFEPA; therefore, for future research, it is recommended to carry out a comparison between certified and non-certified companies to assess whether the certification modifies the relationships between the variables in our model. Third, this study focused only on PROFEPA’s environmentally certified companies located in Mexico. To generalize the findings, future research should explore whether the results remain consistent with other environmental certifications and emerging countries. However, the survey instrument developed in this research can be applied in future studies in various geographical contexts. In addition, it will be interesting to test the research model in other parts of the world, such as in Latin American and European countries.

Finally, this study was applied only to managers and/or environmental contacts of certified companies, but it would be interesting to do triangulation with other actors, such as company employees or customers, to analyze the influence of TEL.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, D.A.R.-A. and P.S.S.-M.; methodology, D.A.R.-A., P.S.S.-M. and R.D.-P.; software, D.A.R.-A. and R.D.-P.; validation, D.A.R.-A. and R.D.-P.; formal analysis, D.A.R.-A. and R.D.-P.; investigation, D.A.R.-A.; resources, D.A.R.-A. and P.S.S.-M.; data curation, D.A.R.-A. and R.D.-P.; writing—original draft preparation, D.A.R.-A., P.S.S.-M. and M.F.S.-B.; writing—review and editing, D.A.R.-A., P.S.S.-M., R.D.-P. and M.F.S.-B.; visualization, D.A.R.-A., P.S.S.-M., R.D.-P. and M.F.S.-B.; supervision, D.A.R.-A. and P.S.S.-M.; project administration, P.S.S.-M.; funding acquisition, D.A.R.-A. and P.S.S.-M. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

This research does not incorporate, collect, process, or relate to sensitive personal data, so there is no applicable Institutional Review Board Statement.

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in this study.

Data Availability Statement

The data that support this study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

Acknowledgments

The authors are grateful to the federal attorney general for environmental protection (PROFEPA). This support played an instrumental role in the investigation project of this article.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Appendix A

Table A1.

Items proposed in the questionnaire.

Table A1.

Items proposed in the questionnaire.

| TEL | Individual Transformational environmental leadership | TEL1 | I inspire subordinates with the sustainable business plan | |

| TEL2 | I provide my subordinates with a clear sustainable vision of the business | |||

| TEL3 | I encourage employees to achieve sustainable business goals | |||

| TEL4 | Considered the sustainable business beliefs of my subordinates | |||

| TEL5 | Discussed my environmental values and beliefs | |||

| Structural Transformational environmental leadership | TEL6 | I provide education and training on environmental issues to my subordinates | ||

| TEL7 | I have developed a well-defined environmental policy | |||

| TEL8 | Support and encourage the development of environmental programs | |||

| TEL9 | I have approved special funds for investment in clean technologies | |||

| CSR | Environmental | CSR1 | Implement environmental protection activities | |

| CSR2 | Has environmental policies | |||

| CSR3 | Launches campaigns that aim to promote awareness of the importance of environmental protection | |||

| CSR4 | Take actions to save energy beyond legal requirements | |||

| CSR5 | Take voluntary actions to recycle and/or reuse | |||

| Social and ethical | CSR6 | Provides procedures that help ensure the health and safety of employees | ||

| CSR7 | Recognizes that its directors and employees have a central role in upholding its ethical standards and codes of conduct | |||

| CSR8 | It directly addresses issues of justice in line with criteria developed and endorsed by workers and interest groups as an expression of its economic, social and environmental report | |||

| CSR9 | Is highly committed to well-defined ethical principles | |||

| Legal | CSR10 | Performs consistently with government expectations and the law | ||

| CSR11 | Complies with various international, government and local regulations | |||

| CSR12 | Provides goods and services that meet minimum legal requirements | |||

| Philanthropic | CSR13 | Sponsors cultural programs | ||

| CSR14 | Make financial donations to social causes | |||

| CSR15 | Sponsorships in educational programs in society | |||

| VC | Cost leader | VC1 | We achieved a leadership position in costs in our sector | |

| VC2 | The company has improved productivity, compared to competing companies | |||

| VC3 | Regulatory compliance costs were reduced (the firm avoids fines for polluting and compensation for damages caused), compared to competing companies | |||

| Differentiation | Innovation | VC4 | We are constantly investing to generate new capabilities that give us an advantage over our competitors | |

| VC5 | Our firm offers that there was a new way of serving customers | |||

| VC6 | The company adapts products and/or services to the changing needs of customers in a better way than the competition | |||

| Market | VC7 | It is difficult for our competitors to imitate us | ||

| VC8 | Nobody can copy our corporate routines, processes and culture | |||

| Quality | VC9 | The company is able to compete based on quality | ||

| VC10 | The company offers products and/or services that are more reliable than those of competing companies | |||

| VC11 | The company has created a special product/brand image that competitors cannot imitate | |||

| DS | Environmental | DS1 | Consumption of hazardous/harmful/toxic materials | |

| DS2 | Generation of hazardous/harmful/toxic materials | |||

| DS3 | Urban solid waste generation | |||

| DS4 | Energy consumption | |||

| DS5 | Polluting gas emissions | |||

| Social | DS6 | Adoption of policies and efforts to be a good corporate citizen | ||

| DS7 | Adoption of policies to improve the safety and health at work of employees | |||

| DS8 | Awareness and protection of the rights of the community served | |||

| DS9 | Relationship with employees | |||

| DS10 | Employee training and education | |||

Appendix B

Table A2.

Items and author(s) proposed in the questionnaire.

Table A2.

Items and author(s) proposed in the questionnaire.

| No. | Ítem | Author(s) |

|---|---|---|

| DS1 | Consumption of hazardous/harmful/toxic materials | * PROFEPA guidelines [103,104] |

| DS2 | Generation of hazardous/harmful/toxic materials | |

| DS3 | Urban solid waste generation | |

| DS4 | Energy consumption | Chiappetta et al. [105] |

| DS5 | Polluting gas emissions | * PROFEPA guidelines [103,104] |

| DS6 | Adoption of policies and efforts to be a good corporate citizen | Dey et al. [64] |

| DS7 | Adoption of policies to improve the safety and health at work of employees | Nor-Aishah et al. [106] |

| DS8 | Awareness and protection of the rights of the community served | |

| DS9 | Relationship with employees | Ali et al. [94] |

| DS10 | Employee training and education |

Note: * Prepared by the authors based on PROFEPA guidelines Normas Mexicanas (Mexican Standards) [103,104].

References

- Pacto Global Red México. Las empresas mexicanas por la agenda 2030 en la década de acción. Red Mex. Pacto 2021, 1–89. Available online: https://pactoglobal.org.mx/las-empresas-mexicanas-por-la-agenda-2030-en-la-decada-de-accion/ (accessed on 9 January 2021).

- Responsable. Segundo Estudio Panorama de la Responsabilidad Social en México 2019. Responsible 2019, 1–140. Available online: https://responsable.net/2019/07/23/panorama-la-responsabilidad-social-mexico-2019/ (accessed on 10 March 2022).

- Davis, K. Can business afford to ignore social responsibilities? Calif. Manag. Rev. 1960, 2, 70–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parket, I.R.; Eilbirt, H. Social responsibility: The underlying factors. Bus. Horiz. 1975, 18, 5–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Soloman, R.; Hansen, K. It’s Good Business; Atheneum: New York, NY, USA, 1985. [Google Scholar]

- DiSegni, D.; Huly, M.; Akron, S. Corporate Social Responsibility, Environmental Leadership, and Financial Performance. Soc. Responsib. J. 2015, 1, 131–148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Woo, E.-J.; Kang, E. Environmental Issues As an Indispensable Aspect of Sustainable Leadership. Sustainability 2020, 12, 7014. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barney, J. Firm resources and sustained competitive advantage. J. Manag. 1991, 17, 99–120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hitt, M.; Ireland, R. Relationships among corporate level distinctive competencies, diversification strategy, corporate structure and performance. J. Manag. Stud. 1986, 23, 401–416. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thompson, A.; Strickland, A. Strategic Management: Concepts and Cases; Business Publications: Plano, TX, USA, 1987. [Google Scholar]

- Esteve-Pérez, S.; Mañez-Castillejo, J. The Resource-Based Theory of the Firm and Firm Survival. Small Bus. Econ. 2008, 30, 231–249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Teece, D.P. Dynamic capabilities and strategic management. Strateg. Manag. J. 1997, 18, 509–533. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Augier, M.; Teece, D. Dynamic Capabilities and the Role of Managers in Business Strategy and Economic Performance. Organ. Sci. 2009, 20, 410–421. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kraaijenbrink, J.; Spender, J.; Groen, A. The Resource-Based View: A Review and Assessment of Its Critiques. J. Manag. 2009, 36, 349–372. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barney, J.; Ketchen, D.; Wright, M. The Future of Resource-Based Theory: Revitalization or Decline? J. Manag. 2011, 37, 1299–1315. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seddon, P. Implications for strategic IS research of the resource-based theory of the firm: A reflection. J. Strateg. Inf. Syst. 2014, 23, 257–269. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jamali, D.; Safieddine, A.M.; Rabbath, M. Corporate Governance and Corporate Social Responsibility Synergies and Interrelationships. Corp. Gov. Int. Rev. 2008, 16, 443–459. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Turker, D. How Corporate Social Responsibility Influences Organizational Commitment. J. Bus. Ethics 2009, 89, 189–204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Su, X.; Xu, A.; Lin, W.; Chen, Y.; Liu, S.; Xu, W. Environmental Leadership, Green Innovation Practices, Environmental Knowledge Learning, and Firm Performance. SAGE Open 2020, 10, 215824402092290. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Graves, L.M.; Sarkis, J.; Zhu, Q. How transformational leadership and employee motivation combine to predict employee proenvironmental behaviors in China. J. Environ. Psychol. 2013, 35, 81–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dombrowski, U.; Mielke, T. Lean Leadership—Fundamental Principles and Their Application. Procedia CIRP 2013, 7, 569–574. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Robertson, J.; Barling, J. Greening organizations through leaders’ influence on employees’ pro-environmental behaviors. J. Organ. Behav. 2013, 34, 176–194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jones Christensen, L.I.; Mackey, A.; Whetten, D. Taking responsibility for corporate social responsibility: The role of leaders in creating, implementing, sustaining, or avoiding socially responsible firm behaviors. Acad. Manag. Perspect. 2014, 28, 164–178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Robertson, J.L.; Barling, J. Contrasting the nature and effects of environmentally specific and general transformational leadership. Leadersh. Organ. Dev. J. 2017, 38, 22–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Graves, L.M.; Sarkis, J.; Gold, N. Employee proenvironmental behavior in Russia: The roles of top management commitment, managerial leadership, and employee motives. Resour. Conserv. Recycl. 2019, 140, 54–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carroll, A.B. Carroll’s pyramid of CSR: Taking another. Int. J. Corp. Soc. Responsib. 2016, 1, 3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gobierno de México. Available online: https://www.gob.mx/profepa/que-hacemos (accessed on 24 March 2024).

- Duanmu, J.-L.; Bu, M.; Pittman, R. Does market competition dampen environmental performance? Evidence from China. Strateg. Manag. J. 2018, 39, 3006–3030. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rajesh, R. Exploring the sustainability performances of firms using environmental, social, and governance scores. J. Clean. Prod. 2020, 247, 119600. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carroll, A. Corporate social responsability and the COVID-19 pandemic: Organizational and managerial implications. J. Strateg. Manag. 2021, 14, 315–330. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vural-Yavaş, C. Economic policy uncertainty, stakeholder engagement, and environmental, social, and governance practices: The moderating effect of competition. Corp. Soc. Responsib. Environ. Manag. 2020, 28, 82–102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wijethilake, C. Proactive sustainability strategy and corporate sustainability performance: The mediating effect of sustainability control systems. J. Environ. Manag. 2017, 196, 569–582. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, J.; Yuan, Y.; Zhang, J. Environmental leadership in organizations: A literature review and prospects. Econ. Manag. J. 2018, 40, 193–208. [Google Scholar]

- PROFEPA. Informe de Actividades 2019. México: Secretaría de Medio Ambiente y Recursos Naturales 2020. Available online: https://www.gob.mx/cms/uploads/attachment/file/557861/informe-de-actividades-profepa-2019.pdf (accessed on 12 March 2020).

- Eisenhardt, K.M.; Martin, J. Dynamic Capabilities: What are They? Strateg. Manag. J. 2000, 21, 1105–1121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Teece, D.J. Explicating dynamic capabilities: The nature and microfoundations of (sustainable) enterprise performance. Strateg. Manag. J. 2007, 28, 1319–1350. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Teece, D.J. The Foundations of Enterprise Performance: Dynamic and Ordinary Capabilities in an (Economic) Theory of Firms. Acad. Manag. Perspect. 2014, 28, 328–352. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qiu, L.; Jie, X.; Wang, Y.; Zhao, M. Green product innovation, green dynamic capability, and competitive advantage: Evidence from Chinese manufacturing enterprises. Corp. Soc. Responsib. Environ. Manag. 2019, 27, 146–165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferreira, J.; Coelho, A.; Moutinho, L. Dynamic capabilities, creativity and innovation capability and their impact on competitive advantage and firm performance: The moderating role of entrepreneurial orientation. Technovation 2020, 92–93, 102061. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wilden, R.; Devinney, T.M.; Dowling, G.R. The architecture of dynamic capability re-search identifying the building blocks of a configurational approach. Acad. Manag. Ann. 2016, 10, 997–1076. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Helfat, C.E.; Finkelstein, S.; Mitchell, W.; Peteraf, M.; Singh, H.; Teece, D.; Winter, S.G. Dynamic Capabilities: Understanding Strategic Change in Organizations; Wiley-Blackwell: Oxford, UK, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Fainshmidt, S.; Wenger, L.; Pezeshkan, A.; Mallon, M. When do Dynamic Capabilities Lead to Competitive Advantage? The Importance of Strategic Fit. J. Manag. Stud. 2018, 56, 758–787. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hoopes, D.M. Guest editors’ introduction to the special issue: Why is there a resource-based view? Toward a theory of competitive heterogeneity. Strateg. Manag. J. 2003, 24, 889–902. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lippman, S.; Rumelt, R. Uncertain Imitability: An Analysis of Interfirm Differences in Efficiency under Competition. Bell J. Econ. 1982, 13, 418–438. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Teece, D.J. Dynamic capabilities and entrepreneurial management in large organizations: Toward a theory of the (entrepreneurial) firm. Eur. Econ. Rev. 2016, 86, 202–216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gobierno de México. Secretaría de Economía. Available online: https://www.gob.mx/se/articulos/responsabilidad-social-empresarial-32705 (accessed on 24 March 2024).

- López, N.; Martín, G. La Dirección Estratégica de la Empresa. Teoría y Aplicaciones; Civitas: Madrid, Spain, 2002. [Google Scholar]

- McWilliams, A.; Siegel, D.S.; Wright, P.M. Corporate social responsibility: International perspectives. J. Bus. Strateg. 2006, 23, 1–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Porter, M. Toward a dynamic theory of strategy. Strateg. Manag. J. 1991, 12, 95–117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pucheta-Martínez, M.C.; Gallego-Álvarez, I. An international approach of the relationship between board attributes and the disclosure of corporate social responsibility issues. Corp. Soc. Responsib. Environ. Manag. 2018, 26, 612–627. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Budur, T.; Demir, A. Leadership Effects on Employee Perception about CSR in Kurdistan Region of Iraq. Int. J. Soc. Sci. Educ. Stud. 2019, 5, 184–192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saha, R.; Shashi; Cerchione, R.; Singh, R.; Dahiya, R. Effect of ethical leadership and corporate social responsibility on firm performance: A systematic review. Corp. Soc. Responsib. Environ. Manag. 2019, 27, 409–429. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahsan, M.J. Unlocking sustainable success: Exploring the impact of transformational leadership, organizational culture, and CSR performance on financial performance in the Italian manufacturing sector. Soc. Responsib. J. 2024, 20, 783–803. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lopez-Cabrales, A.; Bornay-Barrachina, M.; Diaz-Fernandez, M. Leadership and dynamic capabilities: The role of HR systems. Pers. Rev. 2017, 46, 255–276. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, R.; Lee, Y.-D.; Wang, C.-H. Total quality management and sustainable competitive advantage: Serial mediation of transformational leadership and executive ability. Total Qual. Manag. Bus. Excell. 2018, 31, 451–468. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hussein, H.; Albadry, O.M.; Mathew, V.; Al-Romeedy, B.S.; Alsetoohy, O.; Abou Kamar, M.; Khairy, H.A. Digital Leadership and Sustainable Competitive Advantage: Leveraging Green Absorptive Capability and Eco-Innovation in Tourism and Hospitality Businesses. Sustainability 2024, 16, 5371. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tien, N.H.; Hung Anh, D.B. Gaining competitive advantage from CSR policy change: Case of foreign corporations in Vietnam. Pol. J. Manag. Stud. 2018, 18, 403–417. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ratnawati; Soetjipto, B.E.; Murwani, F.D.; Wahyono, H. The Role of SMEs’ Innovation and Learning Orientation in Mediating the Effect of CSR Programme on SMEs’ Performance and Competitive Advantage. Glob. Bus. Rev. 2018, 19, S21–S38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shah, S.; Khan, Z. Corporate social responsibility: A pathway to sustainable competitive advantage? Int. J. Bank Mark. 2020, 38, 159–174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eyasu, A.M.; Arefayne, D. The effect of corporate social responsibility on banks’ competitive advantage: Evidence from Ethiopian lion international bank SC. Cogent Bus. Manag. 2020, 7, 1830473. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sigit, H.; Tariq, T.; Yousif, A.; Sriyono, S.; Satrio, S.; Prasetyo, U. Green perspective on intellectual capital, corporate social responsibility, and competitive advantage: The role of firm performance. Environ. Econ. 2024, 15, 97–107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pan, C.L.; Tian, H. Environmental leadership, green organizational identity and corporate green innovation performance. Chin. J. Manag. 2017, 14, 832–841. [Google Scholar]

- Chang, H.-T.; Chou, Y.-J.; Miao, M.-C.; Liou, J.-W. The effects of leadership style on service quality: Enrichment or depletion of innovation behaviour and job standardisation. Total Qual. Manag. Bus. Excell. 2019, 32, 676–692. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dey, M.; Bhattacharjee, S.; Mahmood, M.; Uddin, M.A.; Biswas, S.R. Ethical leadership for better sustainable performance: Role of employee values, behavior and ethical climate. J. Clean. Prod. 2022, 337, 0959–6526. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ledi, K.K.; Prah, J.; Ameza-Xemalordzo, E.; Bandoma, S. Environmental performance reclaimed: Unleashing the power of green transformational leadership and dynamic capability. Cogent Bus. Manag. 2024, 11, 2378922. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abbas, J.; Mahmood, S.; Ali, H.; Ali Raza, M.; Ali, G.; Aman, J.; Bano, S.; Nurunnabi, M. The Effects of Corporate Social Responsibility Practices and Environmental Factors through a Moderating Role of Social Media Marketing on Sustainable Performance of Business Firms. Sustainability 2019, 11, 3434. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Orazalin, N.; Baydauletov, M. Corporate social responsibility strategy and corporate environmental and social performance: The moderating role of board gender diversity. Corp. Soc. Responsib. Environ. Manag. 2020, 27, 1664–1676. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anser, M.K.Y.Z.; Majid, A.; Yasir, M. Does corporate social responsibility commitment and participation predict environmental and social performance? Corp. Soc. Responsib. Environ. Manag. 2020, 27, 2578–2587. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Malik, S.Y.; Hayat Mughal, Y.; Azam, T.; Cao, Y.; Wan, Z.; Zhu, H.; Thurasamy, R. Corporate Social Responsibility, Green Human Resources Management, and Sustainable Performance: Is Organizational Citizenship Behavior towards Environment the Missing Link? Sustainability 2021, 13, 1044. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Le, T. How do corporate social responsibility and green innovation transform corporate green strategy into sustainable firm performance? J. Clean. Prod. 2022, 362, 132228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Villena, M.G.; Quinteros, M.J. Corporate Social Responsibility, Environmental Emissions and Time-Consistent Taxation. Environ. Resour. Econ. 2024, 87, 219–255. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sihite, M. Competitive Advantage: Mediator of Diversification and Performance. IOP Conf. Ser. Mater. Sci. Eng. 2018, 288, 012102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, S.; Ishtiaq, M.; Anwar, M. Enterprise risk management practices and firm performance, the mediating role of competitive advantage and the moderating role of financial literacy. J. Risk Financ. Manag. 2018, 11, 35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Do, B.; Nguyen, N. The links between proactive environmental strategy, competitive advantages and firmperformance: An empirical study in Vietnam. Sustainability 2020, 12, 4962. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cahyono, Y.; Purwoko, D.; Koho, I.; Setiani, A.; Supendi, S.; Setyoko, P.; Sosiady, M.; Wijoyo, H. The role of supply chain management practices on competitive advantage and performance of halal agroindustry SMEs. Uncertain Supply Chain. Manag. 2023, 11, 153–160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shebeshe, E.N.; Sharma, D. Sustainable supply chain management and organizational performance: The mediating role of competitive advantage in Ethiopian manufacturing industry. Future Bus. J. 2024, 10, 47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nguyen, P.V.; Ngoc Huynh, H.T.; Hai Lam, L.N.; Bao Le, T.; Xuan Nguyen, N.H. The impact of entrepreneurial leadership on SMEs’ performance: The mediating effects of organizational factors. Heliyon 2021, 7, e07326. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tan, K.; Siddik, A.B.; Sobhani, F.A.; Hamayun, M.; Masukujjaman, M. Do Environmental Strategy and Awareness Improve Firms’ Environmental and Financial Performance? The Role of Competitive Advantage. Sustainability 2022, 14, 10600. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, H.; Yu, J.; Kim, W. Environmental corporate social responsibility and the strategy to boost the airline’s image and customer loyalty intentions. J. Travel Tour. Mark. 2019, 36, 371–383. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Valdiansyah, R.H.; Augustine, Y. Modelling of beyond budgeting, competitor accounting, transparency, competitive advantage, and organizational performance: The case of Indonesia SMEs. Tech. Soc. Sci. J. 2021, 22, 334–349. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hang, Y.; Sarfraz, M.; Khalid, R.; Ozturk, I.; Tariq, J. Does corporate social responsibility and green product innovation boost organizational performance? A moderated mediation model of competitive advantage and green trust. Econ. Res.-Ekon. Istraživanja 2022, 35, 5379–5399. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dubey, R.; Gunasekaran, A.; Ali, S.S. Exploring the relationship between leadership, operational practices, institutional pressures and environmental performance: A framework for green supply chain. Int. J. Prod. Econ. 2015, 160, 120–132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, S.K.; Del Giudice, M.; Chierici, R.; Graziano, D. Green innovation and environmental performance: The role of green transformational leadership and green human resource management. Technol. Forecast. Soc. Change 2020, 150, 119762. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cronjé, F.; van Wyk, J. Measuring corporate personality with social responsability bench marks. J. Glob. Responsib. 2013, 4, 188–243. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bernal-Conesa, J.; Briones-Peñalver, A.J.; Nieves-Nieto, C. Impacts of the CRS strategies of technology companies on performance and competitiveness. Tour. Manag. Stud. 2017, 13, 73–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Choongo, P. A longitudinal study of the impact or corporate social responsability on firm performance in SMEs in Zambia. Sustainability 2017, 9, 1300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mallouh, A.; Tahtamouni, A. The impact of social responsibility disclosure on the liquidity of the Jordanian industrial corporations. Int. J. Manag. Financ. Account. 2018, 10, 273–300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, S.; Han, H.; Radic, A.; Tariq, B. Corporate social responsibility (CSR) as a customer satisfaction and retention strategy in the chain restaurant sector. J. Hosp. Tour. Manag. 2020, 45, 348–358. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anwar, M.; Rehman, A.U.; Shah, S.Z.A. Networking and new venture’s performance: Mediating role of competitive advantage. Int. J. Emerg. Mark. 2018, 13, 998–1025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, C.-H. How organizational green culture influences green performance and competitive advantage: The mediating role of green innovation. J. Manuf. Technol. Manag. 2019, 30, 666–683. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reklitis, P.; Sakas, D.P.; Trivellas, P.; Tsoulfas, G.T. Performance Implications of Aligning Supply Chain Practices with Competitive Advantage: Empirical Evidence from the Agri-Food Sector. Sustainability 2021, 13, 8734. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Habidin, N.F.; Zubir, A.F.M.; Fuzi, N.M.; Latip, N.A.M.; Azman, M.N.A. Sustainable manufacturing practices in Malaysian automotive industry: Confirmatory factor analysis. J. Glob. Entrep. Res. 2015, 5, 14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bamgbade, J.A.; Kamaruddeen, A.M.; Nawi, M.N.M.; Yusoff, R.Z.; Bin, R.A. Does government support matter? Influence of organizational culture on sustainable construction among Malaysian contractors. Int. J. Constr. Manag. 2018, 18, 93–107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ali, H.; Chen, T.; Hao, Y. Sustainable Manufacturing Practices, Competitive Capabilities, and Sustainable Performance: Moderating Role of Environmental Regulations. Sustainability 2021, 13, 10051. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Antonakis, J.; Bendahan, S.; Jacquart, P.; Lalive, R. On making causal claims: A review and recommendations. Leadersh. Q. 2010, 21, 1086–1120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fornell, C.; Larcker, D.F. Evaluating structural equation models with unobservable variables and measurement error. J. Mark. Res. 1981, 18, 39–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kline, R.B. Principles and Practice of Structural Equation Modeling; The Guildford Press: New York, NY, USA, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Bhuiyan, F.; Rana, T.; Baird, K.; Munir, R. Strategic outcome of competitive advantage from corporate sustainability practices: Institutional theory perspective from an emerging economy. Bus. Strateg. Environ. 2023, 32, 4217–4243. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Foo, P.Y.; Lee, V.H.; Ooi, K.B.; Tan, G.W.H.; Sohal, A. Unfolding the impact of leadership and management on sustainability performance: Green and lean practices and guanxi as the dual mediators. Bus. Strateg. Environ. 2021, 30, 4136–4153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Riva, F.; Magrizos, S.; Rubel, M.R.B. Investigating the link between managers’ green knowledge and leadership style, and their firms’ environmental performance: The mediation role of green creativity. Bus. Strateg. Environ. 2021, 30, 3228–3240. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sarwar, H.; Aftab, J.; Ishaq, M.I.; Atif, M. Achieving business competitiveness through corporate social responsibility and dynamic capabilities: An empirical evidence from emerging economy. J. Clean. Prod. 2023, 386, 135820. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Waqas, M.; Honggang, X.; Ahmad, N.; Khan, S.A.R.; Iqbal, M. Big data analytics as a roadmap towards green innovation, competitive advantage and environmental performance. J. Clean. Prod. 2021, 323, 128998. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- NMX-AA-162-SCFI-2012; Normas Mexicanas NMX-AA-162-SCFI-2012. Procuraduria Federal de Proteccion al Ambiente: Mexico City, Mexico, 2012.

- NMX-AA-163-SCFI-2012; Normas Mexicanas NMX-AA-163-SCFI-2012. Procuraduria Federal de Proteccion al Ambiente: Mexico City, Mexico, 2012.

- Chiappetta, C.; Seuring, S.; Lopes de Sousa Jabbour, A.B.; Jugend, D.; De Camargo Fiorini, P.; Latan, H.; Izeppi, W.C. Stakeholders, innovative business models for the circular economy and sustainable performance of firms in an emerging economy facing institutional voids. J. Environ. Manag. 2020, 264, 110416. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nor-Aishah, H.; Ahmad, N.H.; Thurasamy, R. Entrepreneurial leadership and sustainable performance of manufacturing SMEs in Malaysia: The contingent role of entrepreneurial bricolage. Sustainability 2020, 12, 3100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).