Sun and Sand Ecotourism Management for Sustainable Development in Sisal, Yucatán, Mexico

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

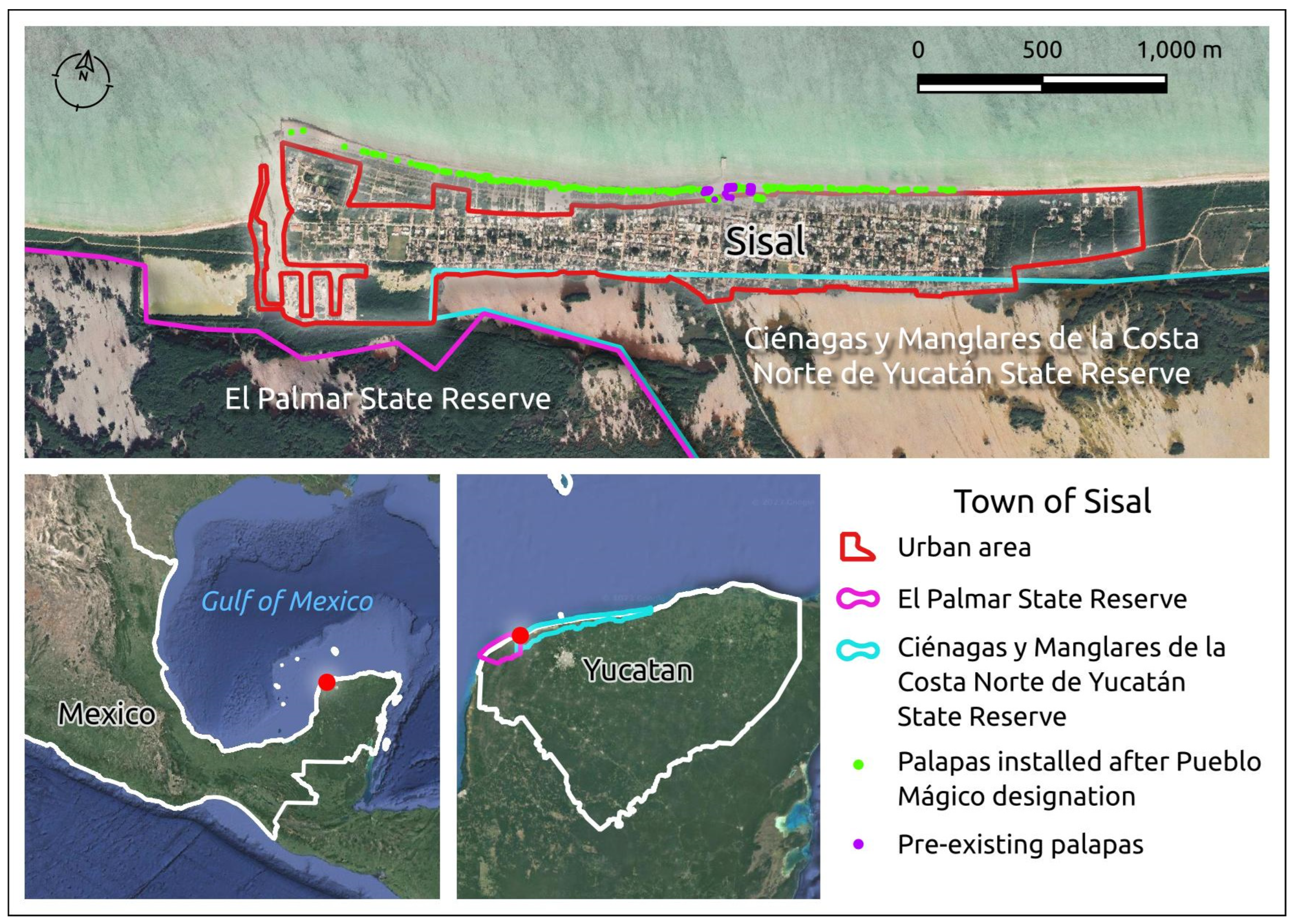

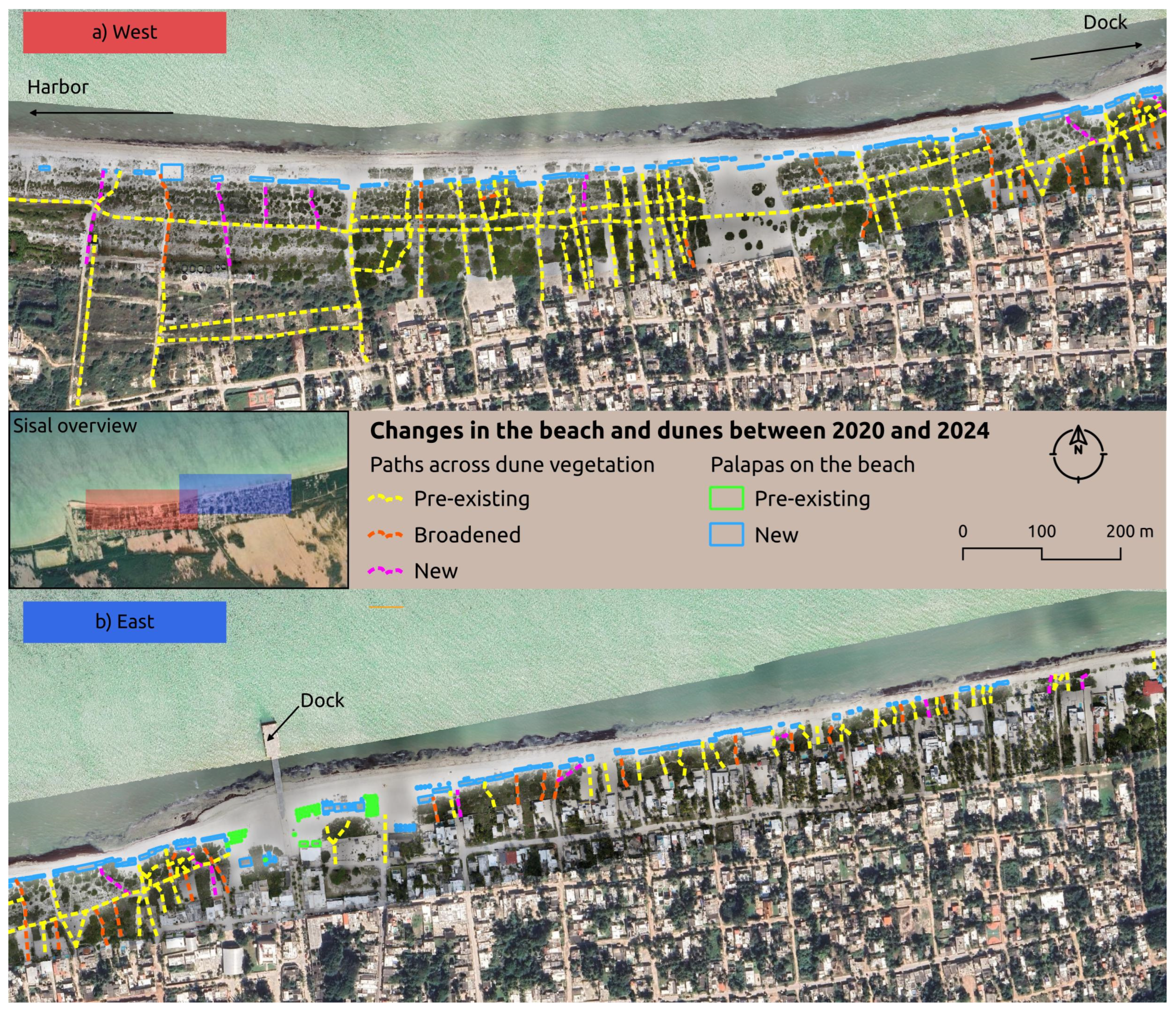

2.1. Study Area

2.2. Interviews and Surveys

2.2.1. Interviews

2.2.2. Surveys

2.3. Information Analysis

2.3.1. Interviews

2.3.2. Surveys

3. Results

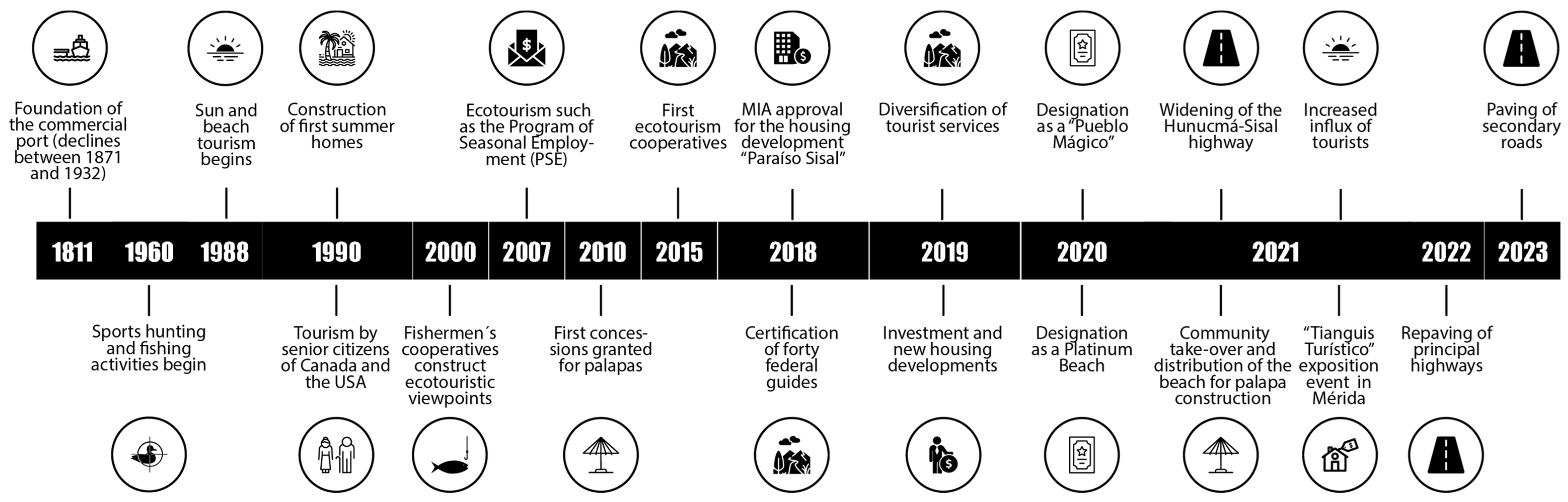

3.1. Interviews: History of Tourism in Sisal

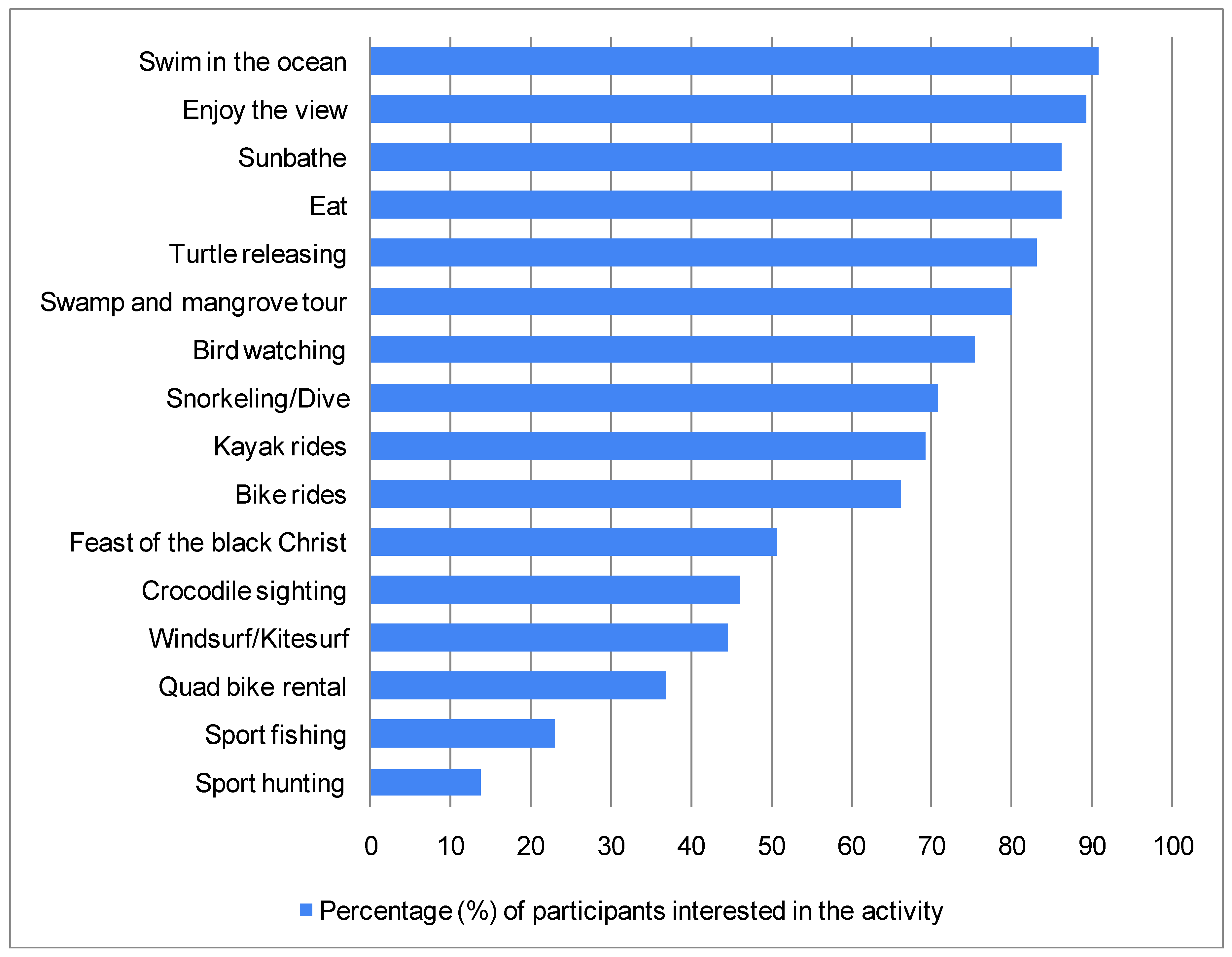

3.2. Surveys: Sisal as a Current Tourism Destination

3.3. Challenges and Conflicts among Social Actors in the Management of Nature-Based Tourism or Ecotourism

- Set “A”: Governmental authorities in charge of federal, state, and municipal environmental protection. They regulate the use of natural resources through mandatory environmental regulations and standards.

- Set “B”: Local authority, organized and unorganized local population, tourism service providers, traders, and tourists (local, national, and international). They are under the political power of Set “A” and depend to varying extents on the economic resources and information available. They have options to resist pressure and even to apply pressure on Set “A” through social mobilization, a situation that could lead to possible conflicts. Their presence and participation are of particular importance for the conservation of ecosystems of their interest.

- Set “C”: Institutions and academic groups that operate at the local level and have a strong interest in conservation. Their research performance implies objectivity and impartiality in interlocution with actors from the other sets, without differences in their interests necessarily leading to conflict. This gives them a potential role as generators of evidence-based information with which to address territorial conflicts. Their impact, often demanded by the local actors and authorities themselves, depends on the degree of ethics, commitment, and positioning of academics, as well as the administrative processes of the institution.

- Set “D”: Organized palaperos and private outsiders (tourism investors and real estate developers). Their interest is the economic exploitation of natural resources, using their physical and moral resources (palaperos) or their economic, social, and information power (private outsiders). It is this group that generally resists environmental regulations and norms for their use, and it has more tools and strategies with which to evade the environmental regulatory influence of Set “A”.

- Set “E”: Governmental institutions, the activities of which are mainly oriented towards the promotion of socio-economic tourism development and which present tools of political power and information. Their actions can have a major impact on the territory, the management of emerging conflicts, the conservation of coastal ecosystems, the social well-being of the inhabitants, and environmental justice.

4. Discussion

4.1. Conflicts and Challenges for the Development of Sustainable Local Tourism in Sisal

4.2. New Perspectives of Sustainable Ecotourism in Sisal

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Statista. Available online: https://es.statista.com/estadisticas/640133/aportacion-del-sector-turistico-al-pib-mundial/ (accessed on 14 February 2024).

- United Nations World Tourism Organization (UNWTO). Panorama del Turismo Internacional; United Nations World Tourism Organization (UNWTO): Madrid, Spain, 2019; p. 23. [Google Scholar]

- Nguyen, D.T.; Kuo, K.C.; Lu, W.M.; Nhan, D.T. How sustainable are tourist destinations worldwide? An environmental, economic, and social analysis. J. Hosp. Tour. Res. 2024, 48, 698–711. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- United Nations World Tourism Organization (UNWTO). Available online: https://www.unwto.org/sustainable-development (accessed on 28 August 2024).

- Lu, L.; Zeng, J.; Yu, T. A review of studies on tourism ecological security. Ecol. Sci. 2023, 42, 238–247. [Google Scholar]

- Secretaría de Turismo (Sectur). Available online: https://www.gob.mx/sectur/prensa/mexico-se-reposiciona-en-el-9-lugar-mundial-en-captacion-de-divisas-por-turismo-segun-la-omt?idiom=es (accessed on 21 May 2023).

- Secretaría de Turismo (Sectur). Resultados de la Actividad Turística, 2019th ed. Available online: https://www.datatur.sectur.gob.mx/RAT/RAT-2019-12(ES).pdf (accessed on 6 December 2019).

- Jaramillo-Escobedo, J.V.; Luyando-Cuevas, J.R. Percepción de los residentes en un destino turístico de sol y playa en el noreste de México como precursor del desarrollo local y sustentable. Tur. Soc. 2023, 32, 119–143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gobierno del Estado de Yucatán (GEY). Siete Playas de Yucatán Reciben Certificación Platino por Segundo año Consecutivo. 2022. Available online: https://www.yucatan.gob.mx/saladeprensa/ver_nota.php?id=6359 (accessed on 19 February 2024).

- Diario Oficial de la Federación. Acuerdo por el que se Expide la Estrategia Nacional de Pueblos Mágicos 01-10-2020. Secretaría de Turismo, 2020. Available online: http://sistemas.sectur.gob.mx/PueblosMagicos/Formatos/ENPM-DOF.pdf (accessed on 10 March 2020).

- Secretaría de Turismo (Sectur). Estrategia Nacional de Pueblos Mágicos. Available online: https://sistemas.sectur.gob.mx/PueblosMagicos/Formatos/ENPM.pdf (accessed on 1 October 2020).

- Secretaría de Turismo (Sectur). Guía de Incoporación y Permanencia, Pueblos Mágicos. Available online: https://www.sectur.gob.mx/wp-content/uploads/2014/10/GUIA-FINAL.pdf (accessed on 8 July 2024).

- Ellinger da Fonseca, P. Tourism for What Development? The Role of Entrepreneurs and Institutions in Shaping Paths. Master’s Thesis, Local and Regional Development (LRD), The Hague, The Netherlands, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Nelson, A.C. Theories of Regional Development. In Theories of Local Economic Development, 1st ed.; Bingham, R.D., Mier, R., Eds.; Sage: London, UK, 1993; pp. 27–57. [Google Scholar]

- Wahab, S.; Pigram, J.J. Tourism, Development and Growth: The Challenge of Sustainability, 1st ed.; Routledge: London, UK, 1997; 302p. [Google Scholar]

- Ray, C. The EU LEADER Programme: Rural Development Laboratory. Sociol. Rural. 2000, 40, 163–171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gudynas, E. Desarrollo y sustentabilidad ambiental: Diversidad de posturas, tensiones persistentes. In La Tierra no es Muda: Diálogos Entre el Desarrollo Sostenible y el Postdesarrollo; Matarán-Ruíz, A., López-Castellano, F., Eds.; Universidad de Granada: Granada, Spain, 2011; pp. 69–96. [Google Scholar]

- Von Bertrab Tamm, A.I. Conflicto social alrededor de la conservación en la Reserva de la Biosfera de Los Tuxtlas: Un análisis de intereses, posturas y consecuencias. Nueva Antropol. 2010, 23, 55–80. [Google Scholar]

- Badillo-Alemán, M.; Mendoza-González, G.; Salinas-Peba, L.H.; Robles-Toral, P.J.; Calderón-Godoy, C.; Arceo-Carranza, D.; Garnica-Cabrera, A.; Teutli-Hernández, C.; Salazar-Solís, C.G.; Chiappa-Carrara, X.; et al. Guía de Servicios Ecosistémicos de la duna Costera de la Península de Yucatán; Universidad Nacional Autónoma de México: Mérida, Mexico, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Martínez, M.L.; Silva, R.; Pérez-Maqueo, O.; Chávez, V.; Mendoza-González, G.; Maximiliano-Cordova, C. The dilemma of coastal management: Exploitation or conservation? Coast. Futures 2024, 2, e10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Corriente Alterna. La Resistencia de un Pequeño Puerto a Convertirse en Pueblo Mágico. Available online: https://corrientealterna.unam.mx/nota/sisal-la-resistencia-de-un-pequeno-puerto-a-convertirse-en-pueblo-magico/h (accessed on 10 April 2022).

- Meza-Osorio, Y.T. Perspectivas Locales Sobre el Turismo en Sisal, Yucatán y Sus Implicaciones en la Conservación de los Ecosistemas de Playas y Dunas Costeras en el Contexto de la Designación de Pueblo Mágico. Master’s Thesis, Universidad Nacional Autónoma de México, Mexico City, Mexico, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Urrea-Mariño, U. Análisis de las Prácticas de Vida Asociadas a la Basura, los Residuos y los Desechos en la Población Costera de Sisal, Yucatán: Propuesta de Modelo de Manejo. Bachelor’s Thesis, Universidad Nacional Autónoma de México, Mexico City, Mexico, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Zielinski, S.; Jeong, Y.; Kim, S.I.; Milanés, C.B. Why Community-based Tourism and Rural Tourism in Developing and Developed Nations are Treated Differently? A Review. Sustainability 2020, 12, 5938. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vargas del Río, D. Turismo de Segunda residencia y turismo de naturaleza en el espacio rural mexicano. Estud. Soc. 2015, 23, 290–312. [Google Scholar]

- Córdoba y Ordóñez, J.; García de Fuentes, A. Tourism, globalization and the environment in the Mexican Caribbean Coast. Investig. Geográficas 2003, 52, 117–136. [Google Scholar]

- García de Fuentes, A.; Xool-Koh, M. Turismo alternativo y desarrollo en la costa de Yucatán. In Turismo, Globalización y Sociedades Locales en la Península de Yucatán; El Sauzal, Marín-Guardado, G., de Fuentes, A.G., Daltabuit-Godás, M., Eds.; ACA y PASOS, RTPC: Tenerife, España, 2012; pp. 173–195. [Google Scholar]

- Jouault, S. El turismo solidario: Definición y perspectivas en comunidades de Yucatán. In Turismo y Sustentabilidad en la Península de Yucatán; Fraga, J., Khafash, L., Villalobos-Zapata, G., Eds.; Universidad Autónoma de Campeche: Campeche, Mexico, 2014; pp. 173–186. [Google Scholar]

- Strasdas, W. Ecotourism in Practice: The Implementation of the Socio-Economic and Conservation-Oriented Objectives of an Ambitious Tourism Concept in Developing Countries; Studienkreis für Tourismus und Entwicklung: Ammerland, Germany, 2001; pp. 31–57. [Google Scholar]

- INEGI Censo de Población y Vivienda 2020. Available online: https://www.inegi.org.mx/programas/ccpv/2020/ (accessed on 21 August 2024).

- Méndez, D. Análisis de la Participación Comunitaria en el Ámbito Ambiental, Sisal, Yucatán. Bachelor’s Thesis, Universidad Nacional Autónoma de México, Mexico City, Mexico, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Santoyo-Palacios, A.B. Esbozo Monográfico de Sisal, Yucatán. Bachelor’s Thesis, Laboratorio Nacional de Resiliencia Costera (Lanresc), Hunucmá, Mexico, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Cuevas-Jiménez, A.; Euán-Ávila, J.; Villatoro-Lacouture, M.; Silva-Casarín, R. Classification of Beach Erosion Vulnerability on the Yucatan Coast. Coast. Manag. 2016, 44, 333–349. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- García de Fuentes, A.; Xool, M.; Euán, J.I.; Munguía, A.; Cervera, M.D. La Costa de Yucatán en la Perspectiva del Desarrollo Turístico; Serie Conocimientos, 9; Becerra, R., Ed.; Conabio: Mexico City, Mexico, 2011; 82p. [Google Scholar]

- Hernández-Sampieri, R.; Fernández, C.; Baptista, P. Metodología de la Investigación, 6th ed.; Mc Graw Hill: Ciudad de México, Mexico, 2014; 600p. [Google Scholar]

- Mendoza-González, G.; Paredes-Chi, A.; Méndez-Funes, D.; Giraldo, M.; Torres-Irineo, E. Perceptions and Social Values Regarding the Ecosystem Services of Beaches and Coastal Dunes in Yucatán, Mexico. Sustainability 2021, 13, 3592. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tarrés, M.L.; Vela-Peón, F. Observar, escuchar y comprender. In Sobre la Tradición Cualitativa en la Investigación Social, 1st ed.; El Colegio de México: Ciudad de México, Mexico, 2001; 268p. [Google Scholar]

- Savin-Baden, M.; Major, C. Qualitative Research: The Essential Guide to Theory and Practice, 1st ed.; Routledge: London, UK, 2013; 608p. [Google Scholar]

- King, N.; Horrocks, C. Interviews in Qualitative Research, 1st ed.; Sage: London, UK, 2010; 256p. [Google Scholar]

- Kahn, R.; Cannell, C. Entrevista. In vestigación Social. In Enciclopedia Internacional de las Ciencias Sociales, 1st ed.; David, S., Ed.; Aguilar: Madrid, Spain, 1977; Volume 4, pp. 266–276. [Google Scholar]

- Mertens, D.M. Research and Evaluation in Education and Psychology: Integrating Diversity with Quantitative, Qualitative, and Mixed Methods, 3rd ed.; Sage Publications: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 2010; pp. 88–189. [Google Scholar]

- Penalva-Verdú, C.; Alaminos, A.; Francés, F.; Santacreu, Ó. La Investigación Cualitativa: Técnicas de Investigación y Análisis con Atlas ti, 1st ed.; Pydlos: Cuenca, Ecuador, 2015; 177p. [Google Scholar]

- Brenner, L. Gobernanza ambiental, actores sociales y conflictos en las Áreas Naturales Protegidas mexicanas. Rev. Mex. Sociol 2010, 72, 283–310. [Google Scholar]

- Drawio 1.3. Available online: https://app.diagrams.net/ (accessed on 4 April 2022).

- Por Esto. Mayo 20. Palapas en la Zona de Playa del Pueblo Mágico de Sisal Causa Enfrentamiento. Available online: https://www.poresto.net/yucatan/2021/5/20/palapas-en-la-zona-de-playa-del-pueblo-magico-de-sisal-causa-enfrentamiento.html (accessed on 20 September 2021).

- Secretaría de Medio Ambiente y Recursos Naturales (Semarnat). Available online: https://apps1.semarnat.gob.mx:8443/dgiraDocs/documentos/yuc/resolutivos/2018/31YU2018TD003.pdf (accessed on 11 December 2021).

- López-Maldonado, Y.C. El Interés de Habitantes de Sisal, Yucatán en el Desarrollo de la Comunidad como Centro Turístico a Través del Uso y Manejo del Patrimonio Cultural y Natural. Master’s Thesis, Centro de Investigación y de Estudios Avanzados del Instituto Politécnico Nacional-CINVESTAV, Mexico City, Mexico, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Rodas, M.; Donoso, N.U.; Sanmartín, I. Turismo comunitario en Ecuador: Una revisión de la literatura. Rev. RICIT 2015, 9, 60–78. [Google Scholar]

- Guzmán-López, T.; Sánchez-Cañizares, S.M. Turismo comunitario y generación de riqueza en países en vías de desarrollo. Un estudio de caso en El Salvador. REVESCO 2009, 99, 85–103. [Google Scholar]

- Kieffer, M. Turismo Rural Comunitario y organización colectiva: Un enfoque comparativo en México. Rev. PASOS 2018, 16, 429–441. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Del Cairo, C.; Gómez-Zúñiga, S.; Ortega-Martínez, J.E.; Ortiz-Gallego, D.; Rodríguez-Maldonado, A.C.; Vélez-Triana, J.S.; Vergara-Gutiérrez, T. Dinámicas socioecológicas y ecoturismo comunitario: Un análisis comparativo en el eje fluvial Guayabero-Guaviare. Cuad. Desarrollo Rural 2018, 15, 1–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guzmán-López, T.; Borges, O.; Castillo-Canalejo, A.M. Desarrollo económico local y turismo comunitario en países en vías de desarrollo. Un estudio de caso. Rev. RCS (Ve) 2011, 17, 432–446. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Butler, G.; Rogerson, C.M. Inclusive local tourism development in South Africa: Evidence from Dullstroom. Local Econ. 2016, 31, 264–282. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Acharya, B.P.; Halpenny, E.A. Homestays as an Alternative Tourism Product for Sustainable Community Development: A Case Study of WomenManaged Tourism Product in Rural Nepal. Tour. Plan. Dev. 2013, 10, 367–387. [Google Scholar]

- Hampton, M.P. Entry points for local tourism in developing countries: Evidence from yogyakarta, Indonesia. Geogr. Ann. Ser. B Hum. Geogr. 2003, 85, 85–101. [Google Scholar]

- Ford, Z.E.; Jackson, S.; Bino, G.; Brandis, K.J.; Kingsford, R.T. Scale, evidence, and community participation matter: Lessons in effective and legitimate adaptive governance from decision making for Menindee Lakes in Australia’s Murray-Darling Basin. Ecol. Soc. 2023, 28, 15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Törn, A.; Siikamäki, P.; Tolvanen, A.; Kauppila, P.; Rämet, J. Local people, nature conservation, and tourism in northeastern Finland. Ecol. Soc. 2007, 13, 8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tosun, C. Limits to community participation in the tourism development process in developing countries. Tour. Manag. 2000, 21, 613–633. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ostrom E y Ahn, T.K. Una perspectiva del capital social desde las ciencias sociales: Capital social y acción colectiva. Rev. Mex. Sociol 2003, 65, 155–233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rosado-Varela, A.A.; Castillo-Villanueva, L. Reinvención de destinos turísticos, estrategias y políticas. Capital social comunitario y turismo sostenible como medio para el desarrollo local. In Temas Pendientes y Nuevas Oportunidades en Turismo y Cooperación al Desarrollo, 1st ed.; Nel-lo Andreu, M., Campos-Cámara, B.L., Sosa-Ferreira, A.P., Eds.; URV, UQROO, UCARIBE: Quintana Roo, Mexico, 2015; pp. 407–416. [Google Scholar]

- Szeman, I.; Wenzel, J. What do we talk about when we talk about extractivism? Textual Pract. 2021, 35, 505–523. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shaw, K. Gentrification: What It Is, Why It Is, and What Can Be Done about It. Geogr. Compass 2008, 2, 1697–1728. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mantero, J.C. Desarrollo local y actividad turística. Aportes Transf. 2004, 8, 11–38. [Google Scholar]

- Azuz-Adeath, I.; Rodríguez-Cardózo, L.; Alonso-Peinado, H. Ecosistemas costeros complejos. In Gobernanza y Manejo de las Costas y Mares ante la Incertidumbre Una Guía para Tomadores de Decisiones, 1st ed.; Rivera-Arriaga, E., Azuz-Adeath, I., Cervantes-Rosas, O.D., Espinoza-Tenorio, A., Silva-Casarín, R., Ortega-Rubio, A., Botello, A.V., Vega-Serratos, B., Eds.; Ricomar: Campeche, Mexico, 2020; pp. 517–530. [Google Scholar]

- Leeuwis, C.; Van den Ban, A. Communication for Rural Innovation. Rethinking Agricultural Extension, 1st ed.; Blackwell Publishing: Oxford, UK, 2004; 412p. [Google Scholar]

- Romero-Tarín, A.; Canales-Aliende, J.M. El papel de los centros de poder en el proceso de toma de decisión de las políticas públicas y en la creación de la agenda política. RIPS 2019, 18, 9–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Sector | Characteristic | No. of Participants | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Women | Men | ||

| Governmental | Local and municipal authorities | 1 (25%) | 3 (75%) |

| Social | Local providers of tourism services: ecotourism guides (15), palaperos (5), restaurateurs (6), hoteliers (4), hostel owners (3), artisans (2), merchant (1) | 10 (27.7%) | 26 (72.2%) |

| Private | Investors in tourism and real estate developers | 0 (0%) | 2 (100%) |

| Total | 42 | 11 (27.5%) | 31 (72.5%) |

| Section | Information Analyzed |

|---|---|

| 1. Characterization of the social actors and corresponding activities. | Focal groups: government decision-makers; key investors and service providers. Information gathered: Decision makers (Post and period; relationship with tourism; coastal dunes conservation activities); service providers (type of services; years of activity). |

| 2. Reconstruction of the history of tourism in Sisal. | Timeline: understanding the beginning, development, current events, and perspectives of tourism in Sisal. |

| 3. Formal and non-formal knowledge and future perspectives on the conservation of beaches and coastal dunes in Sisal. | Conservation: determining the knowledge of coastal dunes and their function, estimating and understanding their conservation status, exploring perspectives on conservation. |

| 4. New tourism in Sisal. | Magical town designation: knowledge about this designation, opinion, perspectives. Social groups: Actions for conservation and sustainable tourism and the social influence in each group. |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Meza-Osorio, Y.T.; Mendoza-González, G.; Martínez, M.L. Sun and Sand Ecotourism Management for Sustainable Development in Sisal, Yucatán, Mexico. Sustainability 2024, 16, 8807. https://doi.org/10.3390/su16208807

Meza-Osorio YT, Mendoza-González G, Martínez ML. Sun and Sand Ecotourism Management for Sustainable Development in Sisal, Yucatán, Mexico. Sustainability. 2024; 16(20):8807. https://doi.org/10.3390/su16208807

Chicago/Turabian StyleMeza-Osorio, Yari Tatiana, Gabriela Mendoza-González, and M. Luisa Martínez. 2024. "Sun and Sand Ecotourism Management for Sustainable Development in Sisal, Yucatán, Mexico" Sustainability 16, no. 20: 8807. https://doi.org/10.3390/su16208807

APA StyleMeza-Osorio, Y. T., Mendoza-González, G., & Martínez, M. L. (2024). Sun and Sand Ecotourism Management for Sustainable Development in Sisal, Yucatán, Mexico. Sustainability, 16(20), 8807. https://doi.org/10.3390/su16208807