Abstract

This study aims to investigate the factors contributing to and affecting consumer behavior toward renewable energy by following the theories of reasoned action and planned behavior. For this reason, a quantitative research method was employed and primary data were collected via a questionnaire, resulting in a random sample of 450 respondents. Structural equation modeling (SEM) revealed that concern for environmental commitment positively affects attitudes toward solar energy (β = 0.272, p < 0.001), positive subjective norms toward environmental commitment positively influence attitudes (β = 0.092, p < 0.001), perceptions of solar energy values significantly shape attitudes (β = 0.533, p < 0.001), social influence also plays a role in shaping attitudes (β = 0.047, p < 0.001), and that regulations (behavioral control) have a negative impact on attitudes (β = −0.204, p < 0.001). A positive attitude toward solar energy strongly predicts purchase intention (β = 0.944, p < 0.001). The overall model highlights the direct influence of attitude on buying intention and underscores the roles of environmental concern and functional utility in shaping consumer attitudes. This study contributes to the existing literature on renewable energy adoption by providing empirical evidence on the factors influencing consumers’ attitudes toward solar energy systems. By identifying key predictors, the study offers valuable insights into how these elements shape consumer attitudes and subsequent purchase intentions. Additionally, the study enhances the understanding of the role of positive attitudes in driving investment in solar energy, thereby contributing to both theoretical frameworks and practical applications in energy policy and marketing strategies.

1. Introduction

Climate change is driven by both natural and man-made factors, with the energy industry being a significant man-made contributor [1]. As the climate crisis worsens, causing environmental and economic disruptions, the energy production industry has found itself under increasing scrutiny [2]. Fossil-fuel-based energy production exacerbates environmental problems, necessitating a shift in the energy mix at both state and individual levels. Rising awareness of fossil fuel pollution and supply instability due to geopolitical conflicts, coupled with global price increases [3], underscore the need for alternative energy sources, such as renewable resources, which offer long-term returns and energy security [4].

In addition to the pollution and climate issues, Lebanon is currently facing a very severe economic crisis, which is reflecting negatively on various aspects of life in the country. This economic crisis in Lebanon has led to the deteriorating state of the energy industry in the country and an exponential increase in pollution [5]. The economic crisis, as well as the energy crisis, has affected different aspects of life in the country, such as production, savings, and consumption [6]. Adding to that, the failing state of the energy sector in Lebanon is causing devastating effects on the environment. Alternative sources that compensate for state-level failures in energy supply consist of individual neighborhood-level generators that operate on fossil fuels but which have a low efficiency in terms of supplying electricity across the country. The tendency to compensate for increases in the number of electricity outages via private subscriptions to such generators also comes at large costs for the Lebanese population, as these energy sources are pricier compared with other sources of energy. Renewable energy sources can play a major role in the attempt to overcome the energy problem that has caused such environmental and economic problems in the country, as such sources provide electricity at a lower cost while providing an environmentally friendly way to generate electricity.

Thus, with the recent fuel shortages in Lebanon causing outages even at the level of privately owned generators, the Lebanese population is seeking alternative sources of energy [7]. As a result of attempts to fill these energy shortages, the demand for renewable energy has been increasing considerably in terms of popularity in the country. From here stems the research objective, which is to study Lebanese behavioral patterns toward solar energy.

In the study of consumer behavior, any external change in the environment of an individual is highly likely to cause a change in their behavior. Such new experiences are certain to result in shifts in the trends of consumers. With the severity of the changes being imposed on Lebanese consumers following the economic crisis, this study aims to identify the changes in the behavior of Lebanese consumers related to the use of renewable energy as a substitute for conventional sources of energy in the country.

A change in consumer behavior in the energy consumption patterns in Lebanon addresses a timely topic that is very relevant to the Lebanese consumer amidst the deterioration of the energy sector in the country that manifest via increased energy outages and the increased cost of electricity. A study related to these new trends can guide a national strategy towards renewable energy, could better advance such means of energy production, and could be applicable at both the state level and individual levels. Furthermore, the results might yield suggestions of marketing strategies and show the implications for policy makers and electricity suppliers, while guiding future research in this field.

The study’s main research question is as follows: To what extent are Lebanese consumers prepared to adopt solar energy systems?

The sub-research questions are as follows: SRQ1: To what extent do the green energy behavior predictors affect Lebanese consumers’ attitudes toward solar energy? SRQ2: To what extent does the attitude toward solar energy affect Lebanese consumers’ buying decisions?

This study expands the literature on renewable energy adoption by providing empirical evidence on the factors shaping Lebanese consumers’ attitudes toward solar energy. By identifying critical predictors such as green energy behavior, social influence, and regulatory frameworks, the study offers significant insights into how these factors affect consumer attitudes and purchasing decisions. The findings will have important theoretical and practical implications for energy policy and marketing strategies in Lebanon.

2. Literature Review and Hypotheses Development

2.1. Mainstream Literature

2.1.1. Consumer Behavior

The understanding of consumer behavior can be viewed in relation to three concepts—the consumer’s motives, the consumer’s decision process, and the factors that affect consumer behavior [8].

Behind any activity or consumer action exists a motive [9]. Motivation occurs when a need is aroused that the consumer wishes to satisfy. The concept of motivation was addressed by several theories, such as Maslow’s hierarchy of needs, Murray Henry’s theory, self-determination theory, and Herzberg’s motivation and expectancy theory [10]. In marketing, Maslow’s theory is often used in consumer behavior studies to explain consumer motivation [11,12]. This theory proposes five different levels of needs. The physiological needs are the basic survival needs. The safety needs include protection from violence and theft, emotional stability and wellbeing, health security, and financial security. Love and belonging needs refer to social needs and are related to human interaction such as friendships, membership in social groups, and family bonds. Esteem needs are ego-driven needs which include self-respect, acknowledgment, self-confidence in one’s own potential, and being deserving of respect. Self-actualization needs, also called self-fulfillment needs or growth needs, encompass education, skill development, and the refining of talents.

As the role of marketing remains to be act as an influence on customers seeking to conduct a certain purchase, marketers seek to capture certain moments that matter while trying to market a certain product [13]. These moments are referred to as touch points and have a high level of influence on customers. The model presented by Kotler et al. [14] provides five stages of the decision-making process, where the customer starts with need recognition and then begins searching for information. Then, the customer evaluates the alternatives before ultimately reaching a purchase decision. The decision-making process does not end with the purchase behavior but includes the post-purchase behavior as well. First, need recognition occurs when a consumer exactly determines their needs. At this stage marketers, by using an integrated marketing communication mix, seek to direct consumers toward a recognition of their unfulfilled needs and places the offered the product as an alternative with which to satisfy the aroused need. Second, a search for information would arise when consumers require information about competing products that might satisfy their needs. The role of integrated marketing communication is essential, as it permits marketers to communicate to potential consumers a description of the product values offered. Third, evaluation of alternatives includes comparing the different alternatives to select the best deal based on values that vary among consumers. The comparison process could be based on attributes such as quality, price, brand reputation, and services. In this perspective, marketers must rely on an effectively integrated marketing communication mix to communicate the brand’s differentiated superior values intended to fulfill consumers’ expectations. Fourth, the purchase decision stage indicates that the consumer has evaluated all facts and has reached the decision to purchase the selected brands. Fifth, post-purchase behavior refers to the analysis as to whether the purchased goods match the communicated expectations [14].

The idea of consumer attitude has been widely explored in the marketing literature and is seen as a key factor in predicting purchasing decisions [15,16,17]. Marketers must comprehend consumer attitudes to create effective marketing strategies that target potential customers [18]. In many studies, consumer attitude has been evaluated and measured based on three components of attitudes—beliefs, feelings, and intentions to buy [19]. The cognitive or perception component consists of a person’s knowledge and beliefs regarding an object. The affective component of an attitude comprises the consumer’s emotions or feelings toward an object. The conative component measures the predisposition or tendency to act in a certain way.

2.1.2. Renewable Energy: Solar Energy

Today, there is a global concern for protecting the environment [20]. However, although there is widespread acknowledgment of the need for environmental protection, perceptions regarding the fairness of who bears the burden of change can vary significantly [21]. Some individuals or countries may argue that they are already doing their part to protect the environment, or that they should not be held responsible for past emissions, often placing responsibility on others [21]. In contrast, others believe that responsibility is collective and that every individual and country must make impactful changes to achieve environmental and sustainability goals [21]. These differing perspectives can influence attitudes toward renewable energy adoption and green practices, making it important to recognize not only the economic and environmental benefits but also the need for equitable solutions that address varying levels of responsibility [22]. This controversy on fairness and shared responsibility is vital in global efforts to combat climate change. Guaranteeing that all stakeholders feel a sense of ownership and accountability for the transition to a green economy is key to fostering widespread commitment and impactful change.

The United Nations Environmental Programme (UNEP) defines a green economy as low-carbon, resource-efficient, and socially inclusive, with a focus on human wellbeing and a healthy natural environment [22]. One of the key concerns of the green economy is the clean energy policy, which includes renewable energy. According to the United Nations definition, renewable energy is derived from natural sources that are replenished at a higher rate than they are consumed [22]. Compared with fossil fuels, renewable energy generates far lower emissions, making it a crucial aspect in reducing the emissions that are the primary cause of the global climate crisis [23]. Furthermore, renewable energy can provide economic benefits for both developed and developing countries as it requires lower investment and generates three times more jobs than fossil fuels [24].

Renewable energy encompasses different categories such as wind energy, geothermal energy, hydropower, and bioenergy [24]. In their book, Corkish et al. [25] describe solar energy based on several measurements. First, the sun generates energy through fusion reactions in its core, which have been occurring for 4.5 billion years and are expected to continue for another 6.5 billion years. Second, solar energy accounts for 99.98% of the world’s energy supply, including thermal, hybrid solar, hydro, wind, and wave power. Third, the total power radiated into space by the sun is 3.86 × 1026 W, with most of the radiation being in the visible and infrared parts of the spectrum. Finally, the sun’s electromagnetic radiation has a temperature of around 5778 K.

The advantages of using solar energy are many. The energy production is sustainable, consistent, and available for all areas of the earth. Additionally, solar energy conversion technologies are developing exponentially. Energy collection and conversion to various useful energy forms is generally quiet and clean and there is no local pollution from the operation, including greenhouse gas pollution [26].

2.1.3. Green Marketing

The concept of green marketing originated with the wish to include the environmental factor in the marketing process, where elements of the environmental argument are incorporated into the marketing mix [27]. In this regard, green marketing can be said to incorporate the use of limited environmental resources along with traditional marketing practices to render the practices “greener” [28]. Green marketing can provide certain benefits to society, as it is very conscious regarding the use of resources and aims at promoting and advancing products that can actually have a positive impact on the environment, enhancing the overall wellbeing of society [29].

While this term has been used to describe different concepts from its inception in the early 1970s to the present, the most commonly referenced meaning relates to the concepts of resource conservation and pollution prevention, while also incorporating elements of sustainability in the construct. It is also centered on responsibility, as it promotes the responsible use of resources, preserving them and reducing their unnecessary exploitation [30]. While price can be a very important factor in green marketing, with green products often requiring pricier manufacturing and supply chains, green marketing as a marketing practice cannot be effective without incorporating the customer behavior concepts and depends on the understanding of consumer attitudes and beliefs, as well as their readiness to purchase such products [31].

A green consumer exclusively purchases environmentally friendly products produced with eco-friendly values. Green consumer behavior can be influenced by many factors, including the early education of children regarding green issues; as such, awareness can lead to positive habits and better choices later on in life [31]. One of the main attributes of a product that attracts green customers is the durability of the product, as products with better durability last longer and reduce the need to buy new products, and the recyclability of the product, as recyclable products could be reused without wasting more resources [32]. Furthermore, numerous factors have been identified to have an impact on consumers’ intentions to engage in green purchasing. These factors include, but are not limited to, environmental concerns, product knowledge, subjective norms, social impact, attitudes, behavior control, product accessibility, and perceived consumer effectiveness [33].

While green movements aim at causing positive change at a consumer level, their efforts and success could be best described as limited. Products that have a green label occupy a smaller market share than other products [32]. The adoption of green energy solutions is still low, as communities are unaware of the various advantages provided by green energy solutions [34]. Consumers only focus on products that can be recycled, while neglecting the products that have already been recycled, signaling that consumers still do not fully understand renewable energy sources. Consumers, while intending to benefit the environment, are unaware of the different ways to achieve this goal [35].

2.1.4. Consumer Awareness and Energy Consumption

Numerous studies worldwide have shown that consumers are not entirely aware of aspects of their energy consumption, often exhibiting low levels of understanding regarding their energy expenditure. Trotta et al. [36] have shown that households in Finland are not aware of their energy consumption, even as around 20% of the global energy consumption is linked to households, showing the importance of energy literacy at that level. Most of such households were found to be unfamiliar with the requirements needed to heat and cool their houses and unaware of the best practices used to conserve energy. While policies have emerged to tackle such literacy problems in terms of energy consumption, these policies were founded on a scientific basis without offering practical solutions for households [37]. While the policies address important issues, they remain linked to the individual’s effort to adopt those practices. Individuals should understand the importance of such investments to engage with them. Without proper awareness, these policies remain ineffective.

Furthermore, while the main barrier to adopting energy-saving measures is the lack of knowledge related to such measures, another barrier can be observed. Some people have high levels of energy literacy but refuse to engage in such practices for reasons that include the high initial costs of renewable energy installation or a lack of interest in the marginal savings that are realized over long periods. It is important to increase customer awareness to help customers understand the importance of such energy sources in keeping the environment safe and pollution levels manageable [37].

Behavioral trends toward sustainable energy consumption differ among countries and are influenced by external economic factors, such as economic crises, or environmental factors, such as the immanency of climate change globally [38]. As energy consumption is on the rise globally, the daily habits of consumers and domestic expenditure changes can result in great savings over long periods, making the study of behavioral trends related to sustainable energy consumption very important in tackling climate problems. The most prominent environmental trends observed in the energy market are the rise in environmental friendliness, increased control over individual consumption, increased use of electrical vehicles, and increased awareness related to the quality of electricity supply.

2.2. Theoretical Underpinning

The theory of reasoned Action (TRA) was selected as the theoretical underpinning of the study as many studies, such as those of Dalila et al. [39], Indriani et al. [40], and Pratama et al. [41], have used attitude as a mediating variable by which to measure purchase intention. The TRA represents the development of the three components of attitude to measure and predict consumer intention (cognitive, affective, and conative) in addition to subjective norms comprising the social pressures affecting the person’s behavior. In the context of renewable energy, it is noteworthy to mention that TRA was applied in various studies, including those conducted by Gibbons [42], Wall et al. [43], Polcyn et al. [44], Khalid et al. [45], and Loan [46]. This supports the choice of TRA as the theoretical underpinning.

However, while TRA provides a robust framework, it is important to recognize its limitations. TRA assumes that consumers have complete and accurate information and does not fully account for other influential factors, such as perceived behavioral control, social approval, and personal resources. In practice, consumers often make decisions under conditions of uncertainty and incomplete information, especially in regions where resource constraints are prevalent [47]. This is particularly relevant in economically challenged contexts like Lebanon, where financial capacity and peer approval may play a critical role in consumer behavior [48].

To address these limitations, it is necessary to integrate insights from the theory of planned behavior (TPB), also called planned action theory, which introduces the concept of perceived behavioral control [49]. Perceived behavioral control refers to an individual’s perceived ability to perform a behavior, taking into account both internal factors (such as self-efficacy) and external factors (such as access to financial resources and infrastructure) [50].

In the context of solar energy, positive attitudes can emerge from awareness of environmental benefits and cost savings [51], while subjective norms reflect social influences, such as community support for green initiatives [52,53,54]. Social approval from family, neighbors, and peers significantly influences consumer behavior [55]. Knowing the “right” thing to do is important, but consumers may still refrain from purchasing green products due to social pressures or concerns about peer acceptance [55]. For example, purchasing solar energy products may be perceived as a luxury in some communities, where financial or cultural barriers exist. Importantly, perceived behavioral control captures a consumer’s belief in their ability to adopt solar technology, which is particularly relevant in regions with economic constraints [45]. Research has shown that these components not only predict behavioral intentions but also mediate the effects of underlying motivations, providing a nuanced understanding of the factors that drive solar energy adoption [44]. Therefore, this study aims to investigate how these dimensions of TPB interact with consumer motives and decision-making processes in influencing the purchasing intentions for solar energy products.

Thus, while TRA provides a foundational framework, the incorporation of perceived behavioral control and the acknowledgment of social influences and resource limitations offer a more comprehensive understanding of consumer decision-making. These additional considerations help to explain why positive attitudes toward solar energy products may not always translate into purchase behavior in resource-constrained settings.

2.3. Hypotheses Development

Attitude is a part of the TRA and TPB, as mentioned previously. Consumers’ attitudes toward green goods are defined as the overall positive or negative evaluation of environmentally friendly products, based on a sense of responsibility toward environmental sustainability [56]. Due to its importance, this variable has been discussed in several studies, such as those of Alhamad et al. [56], Anvar and Venter [57], Bahl and Chandra [58], Chen and Chai [59], Lestari et al. [60], Mehta and Chahal [61], Sahioun et al. [62], Souri et al. [63], Tang et al. [64], and Walia et al. [65].

As mentioned, subjective norms in the TRA and TPB involve the social pressures a person feels to engage or not engage in a certain behavior. Consumers’ concerns toward a green commitment to the Earth refer to an individual’s perception of their moral obligation to contribute to ecological preservation [59]. Various studies, such as those of Bellomo and Pleyers [66], Lin and Niu [67], Maichum et al. [52], and Yadav and Pathak [68], have discussed consumers’ norms about green consumption and their effect on the attitude toward purchasing green products.

Consumers’ perceptions of solar energy values include the perceived benefits of solar energy, such as cost savings, environmental impact, and long-term viability [69,70]. Many previous studies, such as those of Abreu et al. [71], Chan et al. [69], Cousse [72], Irfan et al. [73], Irfan et al. [74], Perlaviciute and Steg [75], Rai and Beck [76], and Sütterlin and Siegrist [77] discussed attitudes towards adopting renewable energy and the impact of consumer perceptions.

Social influence on buying decisions with regard to solar energy represents the effect of social norms, peer pressure, or social acceptability that may motivate or hinder the decision to adopt solar energy [49]. It is also under the umbrella of subjective norms in the TRA and TPB. Several studies, such as those of Axsen and Kurani [78], Aziz et al. [79], Elmustapha et al. [80], Fathima et al. [81], Fathima et al. [82], Kratschmann and Dütschke [83], Li [84], Liang et al. [85], and Wolske et al. [55], have found that social influence has a significant impact on the attitude toward solar energy in different contexts.

Behavioral constraints hindering the purchasing of solar energy are defined as external barriers, such as government regulations, policy constraints, or lack of financial incentives [86,87]. Recent studies by Hille [88], Sun et al. [32], and Xie et al. [89] have emphasized the importance of governmental laws and incentives (behavioral constraints) in affecting consumers’ attitudes toward buying green products such as solar systems.

While prior research has extensively explored consumer behavior, attitudes, and motivations in general, there remains a gap in the literature regarding the intersection of these factors with the adoption of renewable energy sources, particularly solar energy. Previous studies on green consumer behavior primarily address general environmental attitudes and purchasing behaviors, without adequately and comprehensively considering how specific motivational theories, such as the TRA and TPB, influence consumer decision making in the context of renewable energy. Additionally, there is a need for more empirical studies focusing on how these motivational factors impact the adoption of renewable energy in developing economies, where awareness and infrastructure for renewable energy are still evolving. Thus, this study aims to bridge this gap by examining how consumer motives, decision-making processes, and attitudes, grounded in established motivational theories, influence the adoption of solar energy in such contexts.

Based on the abovementioned previous studies and the theoretical underpinnings, in addition to the gap in the literature, the independent variables of this study are as follows: consumers’ attitudes toward green goods, consumers’ concerns toward the Earth and a green commitment, consumers’ perceptions of solar energy values, social influence on buying decisions of solar energy, and behavioral constraints hindering buying solar energy (laws and regulations). Additionally, based on the theoretical underpinnings and previous studies, the mediating variable chosen for this study is the consumers’ attitudes toward solar energy, which represents the overall positive or negative evaluation of using solar energy as an alternative to traditional energy sources [74]. Finally, the dependent variable of this study is the purchase intention of solar energy. This is defined as an individual’s likelihood or intent to buy solar energy equipment in the near future. Intention is frequently used in consumer behavior studies as it reflects a commitment to engage in a specific action and is considered a reliable indicator of future purchasing behavior [49]. In the context of renewable energy, purchase intention is discussed in several studies, such as those of Abreu et al. [71], Chan et al. [69], Claudy et al. [90], Elahi et al. [51], Fornara et al. [91], Irfan et al. [74], Tan et al. [92], and Xie et al. [89]. These studies mention that purchase intention reflects a consumer’s readiness and willingness to invest in solar technology. The use of purchase intention as the outcome variable is justified based on prior literature as mentioned, where intention has been shown to reliably predict future behavior, particularly in the context of high-involvement, high-cost purchases like solar equipment. It is vital to note that, while actual purchase data would provide direct insights, intention to purchase remains a widely accepted predictor of actual behavior, particularly in product categories such as solar energy equipment. Given the resource constraints in Lebanon, understanding intention is especially crucial, as it helps identify potential barriers consumers face before purchasing.

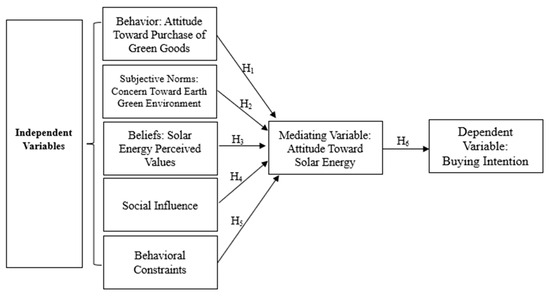

Consequently, the framework in Figure 1 is based on the theoretical foundations and previous studies discussed and provides the groundwork for the empirical part of the study, showing the variables of the study and the hypotheses.

Figure 1.

Research model.

The conceptual model is designed to address the study’s main research question and sub-research questions. The hypotheses are as follows:

H1.

Attitudes toward green products positively affect attitudes toward solar energy.

H2.

Subjective concern for the Earth and a green commitment positively affects attitudes toward solar energy.

H3.

Perception of solar energy values subjectively positively affects the attitude toward solar energy.

H4.

Social influence positively affects the attitude toward solar energy.

H5.

Behavioral constraints related to stimulating laws and regulations positively affect the attitude toward solar energy.

H6.

A positive attitude toward solar energy stimulates a positive purchase intention toward solar energy.

2.4. Research Context

The energy sector in Lebanon has been a challenging issue in recent years, with frequent blackouts and high costs for consumers [93]. It is characterized by a failed state-owned energy supply, with the shortages being partially filled with privately owned generators on the neighborhood level, providing Lebanese households with a portion of their energy needs. This problem has worsened considerably after the closure of the Zahrani and Deir Ammar plants, increasing the reliance of the population on privately owned generators. Producing energy in this way is a great environmental hazard, as these generators produce massive emissions in the absence of regulations [94].

Due to the economic crisis and public debt, the government can no longer afford to import or subsidize fuel, resulting in an energy crisis with worsening power outages and fuel shortages. According to the International Monetary Fund (IMF), electricity accounts for nearly half of Lebanon’s public debt, with the government subsidizing the national electric company, Electricite du Liban (EDL), for years. Thus, despite official tariffs being low, prices end up being higher per kWh due to the bills paid to private generators [95].

Sustainable electricity experts argue that the Lebanese government needs to build new power plants, shut down inefficient old ones, and utilize renewable energy to provide 24-h electricity at lower costs [95]. This will reduce public spending and debt, increase productivity, and generate “green jobs” in the renewable energy sector, contributing to economic growth [95,96].

With the recent fuel shortages in the country causing outages even at the level of privately owned generators, the Lebanese population is seeking alternative sources of energy, with renewable energy considerably increasing in popularity in the country. Lebanon is characterized by a supportive environment for renewable energy, with abundant wind and water, and with around 300 days of sun yearly. Following the economic crisis that started in 2019, solar power became the main source of power in the country amidst the lack of availability of a sustainable grid in the country [94]. More Lebanese households are turning to solar energy for its reliability and affordability compared with conventional sources. The surging demand for solar installations indicates a potential shift towards renewable energy in the country [97].

3. Methodology

The study follows a quantitative approach, one which relies on data collected through a structured questionnaire that was sent to Lebanese consumers asking about different motivations and factors relevant to renewable energy consumption. It consisted of 5-point Likert scale statements and was developed based on an exhaustive review of the literature, including previous studies on consumer motivations toward renewable energy consumption. The items included in the questionnaire were selected based on their relevance to the research objectives and their ability to provide a comprehensive understanding of the factors that drive consumer behavior toward renewable energy adoption. The questionnaire was adopted from Xu et al. [98] and Kianpour et al. [99] which included developed and validated scales to measure consumer behavior toward renewable energy. The questionnaire comprised three major sections—socio-demographic data, customer motivations, and purchase intention.

Attitude toward solar energy was measured using six items to capture respondents’ general environmental concerns and specific attitudes toward solar energy. Items included statements reflecting the fragility of nature, the necessity of ecological balance, and the importance of renewable energy. Subjective norms were measured with six items capturing social influences on solar energy adoption. Respondents were asked about the behavior and expectations of their social networks. Perceived behavioral control was assessed through five items that gauge respondents’ confidence in their ability to adopt solar energy solutions. Purchase intention was measured using three items to reflect respondents’ future intentions to adopt solar energy. Purchase behavior was captured using three items that reflect the frequency of eco-friendly purchasing habits. Motivations for adopting solar energy, including perceived effectiveness, promotional tools, and the influence of behavioral constraints (laws and regulations), were assessed using six items. This section evaluated how these factors drive consumers’ attitudes and intentions toward solar energy adoption.

To ensure clarity, the specific measurement items for purchase intention included questions about the likelihood of considering solar energy equipment, planning to invest, and willingness to replace existing energy systems with solar solutions. These items are consistent with validated scales used in previous studies on purchase intention [98,99].

The questionnaire was replicated on Google Forms (2023), which is a suitable and reachable platform for the participants. The questionnaire was uploaded as a Supplementary File. A random sample of 450 respondents was obtained. The sample size statistical liability was measured through the following equation:

To ensure the relevance of the sample, this study intentionally focused on individuals with decision-making authority within households. This is shown in Table 1, where the majority of the respondents are over 36 years old (35.1% of the respondents). This is followed by the 25–30 age group at 26.2%. Additionally, previous research has indicated that those with higher levels of education and income tend to be early adopters of green technologies, given their greater environmental awareness and financial capacity [37]. As seen in Table 1, the sample is composed largely of college graduates, with around 50% holding graduate degrees. In Lebanon, where resource constraints are a significant barrier, this sample profile indicates a representative sample.

Table 1.

Sample Profile.

In addition to several reliability and validity tests, structural equation modelling (SEM) was used to test the hypotheses.

4. Hypothesis Testing

4.1. KMO and Barlett’s Test of Sphericity

Table 2 shows the outcome of the test. The KMO is 0.726 with a significant Barlett’s test of sphericity (p < 5%), indicating that the developed scale is appropriate for further analysis.

Table 2.

Outcome of KMO and Barlett’s test of sphericity.

4.1.1. Exploratory Factor Analysis

Table 3 shows that the eigenvalues of seven components have values higher than 1, indicating that they are suitable for inclusion in the analysis. Furthermore, these components account for approximately 78.894% of the total variance in the model.

Table 3.

Outcome of total variance explained.

Table 4 highlights that the factor loadings underlying the factors are greater than 0.4, demonstrating a strong correlation between the respective variables measuring the factor.

Table 4.

Outcome of the rotated factor loading matrix.

4.1.2. Confirmatory Factor Analysis

Table 5 shows the model fit. The chi-square statistic yielded a p of 0.002 which is less than 0.05. Thus, this means that the hypothesis that the model fits the data is rejected. However, as this test is sensitive to large sample sizes (in this case, 450), other indices were considered for evaluating the CFA model fit. As shown in Table 5, the model fit is justified as the goodness of fit indices are aligned with the respective cutoff. CFI is 0.964, which is larger than the cutoff value of 0.90. TLI is 0.955 which is greater than the cutoff value of 0.90. SRMR is 0.039 which is less than the cutoff value of 0.08, showing a reasonable fit. RMSEA is 0.049 which indicates a good fit as it lies close to 0.05. The cutoff values are taken from Tabachenik and Fidel [100].

Table 5.

Model Fit.

Table 6 indicates that all retained manifests or observed variables have significantly high loadings with ps less than 0.01 and values exceeding the cutoff of 0.7. This indicates that the factor loadings are statistically significant and confirm the association between the observed variables and their underlying latent constructs.

Table 6.

Confirmatory factor analysis loading factor and scale convergent validity and reliability.

Additionally, the average variance extracted (AVE) values for the convergent validity test meet the requirement, as they are greater than 0.5. This indicates that the items in the scale are measuring the same construct. Furthermore, both tests conducted to assess the scale reliability show that the scale is reliable. The composite reliability values exceed the minimum threshold of 0.7, indicating that the scale items have good internal consistency. The Cronbach’s alpha coefficients fall within an acceptable to good range, which further confirms the scale’s reliability.

Table 7 shows the descriptive statistics for the variables, including the mean, standard error of the mean, and standard deviation. The mean values for the different constructs, such as green purchase behavior intention (GPBI), motivational factors (concern, subjective norms, social influence, functional utility, and behavioral constraints), and buying intention (BI), range between 3.32 and 4.11, indicating a moderate to relatively high level of agreement or positive response across the items.

Table 7.

Descriptive statistics.

The standard errors of the mean are consistently low, suggesting that the sample data are relatively stable and that the mean values are a good representation of the population. The standard deviations, which range between 1.03 and 1.23, indicate that there is some variability within the responses, but none of the items show excessive dispersion. This suggests a moderate level of consistency in the respondents’ answers across the different items.

Thus, these descriptive statistics provide a clear indication of the general patterns and distribution of the data, which are essential for further interpretation and hypothesis testing.

Table 8 shows the scale discriminant validity using the heterotrait–monotrait ratio. The HTMT cutoff is below 0.85 and here, for all the constructs the HTMT ratios are less than 0.85. The results suggest that the constructs are highly distinct from each other and consequently confirm an adequate discriminant validity for all the factors. Thus, based on the confirmatory positive statistical results, SEM analysis can be carried out.

Table 8.

Scale discriminant validity.

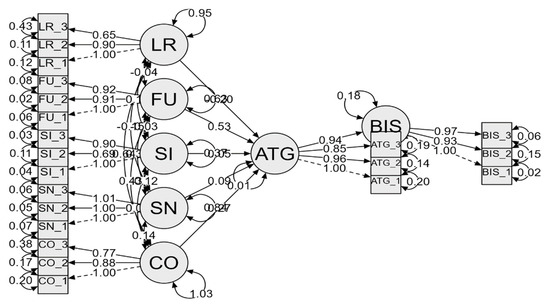

4.1.3. Hypotheses Validation Using SEM

The results in Table 9 provide insights into the relationships between various predictors and the outcomes based on SEM. In Table 8 and Figure 2, CO refers to green concern; SN to subjective norms; SI to social influence; FU to functional utility, which is the perception of solar energy values; LR to behavioral control (rules and regulations); ATG to attitude toward green solar energy; and BIS to buying intention toward solar energy.

Table 9.

SEM results.

Figure 2.

SEM path diagram.

The regression coefficient β = 0.272, z = 7.72, p < 0.001 indicates that green concern has a statistically significant positive effect on attitudes toward solar energy. This suggests that individuals concerned about environmental issues are more likely to adopt favorable attitudes toward solar energy.

With a coefficient β = 0.092, z = 4.867, p < 0.001, we find that subjective norms also positively impact attitudes toward solar energy. This indicates that social pressures or moral obligations encourage individuals to adopt pro-environmental attitudes.

A smaller, but significant, positive relationship is also observed (β = 0.047, z = 4.832, p < 0.001), suggesting that perceived social expectations play a role in shaping positive attitudes.

Functional utility, with the highest effect (β = 0.533, z = 14.353, p < 0.001), shows that perceived usefulness and the practical benefits of solar energy have the strongest influence on attitudes. H4 is strongly supported.

Remarkably, behavioral control has a negative relationship with attitudes (β = −0.204, z = −6.7, p < 0.001), indicating that regulatory barriers may deter positive attitudes toward solar energy.

Finally, a positive and significant relationship is observed (β = 0.944, z = 18.843, p < 0.001), confirming that positive attitudes toward solar energy strongly drive buying intentions.

5. Discussion

5.1. General Discussion

The study found that five out of six hypotheses were supported, indicating that several factors had a statistically significant positive effect on the attitude towards renewable energy, which would lead to a positive intention to invest in a solar system.

Green concern has a positive and significant effect on attitude toward solar energy, as indicated by the regression coefficient β = 0.272, with a z-value of 7.72 and a p of <0.001. This suggests that individuals who are concerned about green issues are more likely to have a positive attitude toward solar energy. Thus, H1 is supported; a positive attitude toward green products positively influences the attitude toward solar energy. This finding aligns with previous studies, such as those of Alhamad et al. [56], Anvar and Venter [57], Bahl and Chandra [58], Chen and Chai [59], Lestari et al. [60], Mehta and Chahal [61], Sahioun et al. [62], Souri et al. [63], Tang et al. [64], and Walia et al. [65], which discuss consumer attitudes toward green goods and their impact on attitudes toward adopting sustainable alternatives like solar energy. These results further confirm the relevance of attitude as part of the TRA and the TPB in shaping consumer decisions in sustainability contexts, including regions like Lebanon, where economic pressures coexist with environmental concerns.

Subjective norms have a significant positive impact on attitude toward solar energy, with a β = 0.092, z-value of 4.867, and p < 0.001. This indicates that subjective norms positively influence attitudes toward green energy. Thus, H2 is supported; positive subjective norms encouraging green behavior positively affect attitudes toward solar energy. These results support the findings of Bellomo and Pleyers [66], Lin and Niu [67], Maichum et al. [52], and Yadav and Pathak [68], who have emphasized that an individual’s moral obligation toward ecological preservation strengthens their positive attitude toward adopting renewable energy. This reinforces the notion that heightened concern for environmental sustainability drives favorable attitudes toward clean energy solutions such as solar energy. In the context of Lebanon, where social ties and community influence are strong, subjective norms may have an even greater impact on consumer attitudes toward solar energy. Given Lebanon’s collective culture and the pressures of economic and energy crises, individuals may feel motivated to adopt solar energy not only out of personal conviction but also because of perceived social expectations and the desire to align with community-driven sustainability practices. This reinforces the notion that heightened concern for environmental sustainability, driven by both individual beliefs and societal pressures, fosters favorable attitudes toward clean energy solutions such as solar energy.

Functional utility, or the perceived usefulness and functionality of solar energy, has the strongest positive effect on attitude toward solar energy, with a β = 0.533, z-value of 14.353, and p < 0.001. This result shows that the practicality and benefits of solar energy greatly influence the attitude toward it. Thus, H3 is supported; the usefulness of solar energy plays a critical role in shaping a positive attitude toward green products like solar energy. This is in line with research by Abreu et al. [71], Chan et al. [69], Cousse [72], Irfan et al. [73], Irfan et al. [74], Perlaviciute and Steg [75], Rai and Beck [76], and Sütterlin and Siegrist [77], which has highlighted that the perceived cost savings, environmental benefits, and long-term sustainability of solar energy play a crucial role in shaping consumer attitudes toward its adoption. The high significance of this factor underscores the importance of communicating the tangible benefits of solar energy in promoting its wider acceptance. In Lebanon, where energy reliability is a persistent concern, these positive perceptions of solar energy’s functionality and usefulness are particularly important. The ability of solar energy to provide a stable and cost-effective alternative to the country’s unreliable energy infrastructure makes its perceived utility crucial in driving consumer interest. This aligns with findings by Elrick-Barr et al. [1], who have noted that, when consumers perceive renewable energy as both technologically advanced and reliable, their intention to invest in such systems increases. In Lebanon’s context, communicating the tangible benefits of solar energy—such as energy independence and cost savings—is vital for promoting its broader acceptance.

Social influence shows a smaller, but significant positive effect on attitude toward solar energy, with β = 0.047, a z-value of 4.832, and a p < 0.001. This suggests that the social context, or how individuals perceive others’ views regarding solar energy, slightly affects their attitude toward adopting green energy. Thus, H4 is supported; positive social influence positively impacts attitudes toward solar energy, though to a lesser extent compared with other variables. This finding aligns with prior research by Axsen and Kurani [78], Aziz et al. [79], Elmustapha et al. [80], Fathima et al. [81], Fathima et al. [82], Kratschmann and Dütschke [83], Li [84], Liang et al. [85], and Wolsk et al. [55] which emphasizes that peer pressure, social norms, and the perceived social acceptability of solar energy positively influence consumer attitudes. As supported by Kanwal et al. [4], social influence; particularly the opinions of family, friends, and community leaders, plays a strong role in shaping consumer decision-making processes. In Lebanon, where communal ties and social networks are deeply rooted, social endorsement of solar energy can significantly boost its adoption. The role of social influence in Lebanon is particularly important, given the close-knit nature of communities, where the approval of peers and local influencers can strongly sway decisions. This underscores the importance of awareness campaigns and endorsements from trusted social groups or influencers to enhance positive attitudes toward solar energy adoption, particularly in developing countries facing similar economic and energy challenges.

Interestingly, regulations that represent the laws and policies around solar energy (behavioral control) have a significant negative effect on attitude toward solar energy, with β = −0.204, z-value of −6.7, and p < 0.001. This suggests that stricter or less favorable regulations may actually hinder positive attitudes toward solar energy adoption. Thus, H5 is not supported in the expected direction. Regulations appear to have a negative rather than positive effect on attitudes toward solar energy. This is not in line with the previous studies of Arroyo and Carrete [86] and Sun et al. [32], which emphasized that government policies and incentives are critical in fostering positive consumer attitudes toward adopting renewable energy. Hille [88] and Kowalska-Pyzalska [87] emphasize that supportive policies and incentives are critical in promoting renewable energy adoption. In the context of Lebanon, where the energy sector is fraught with significant challenges, the results indicate that existing governmental regulations are not viewed as helpful in accelerating the transition to renewable energy. This may be due to the perception that regulations in Lebanon either lack effective implementation or are seen as barriers rather than facilitators in the adoption of solar energy solutions. This underscores the need for more transparent and supportive policy frameworks to positively influence consumer attitudes and drive wider adoption of solar energy in the country.

Finally, attitude toward solar energy has a strong, positive, and significant impact on buying intention toward solar energy, with β = 0.944, z-value of 18.843, and p < 0.001. This indicates that individuals with a positive attitude toward green energy are very likely to express a strong intention to purchase solar energy products. Thus, H6 is supported; a positive attitude toward solar energy strongly drives purchase intentions. This finding is consistent with previous studies, such as those of Abreu et al. [71], Chan et al. [69], and Claudy et al. [90], which found that positive attitudes strongly influence the intention to purchase renewable energy products. Ajzen’s [49] TPB is supported here, as the intention to engage in environmentally friendly behavior, such as purchasing solar energy products, is driven by the consumer’s positive evaluation of the technology. This highlights the importance of fostering positive attitudes to stimulate purchase intentions in high-involvement purchases like solar energy systems. This finding echoes the work of Schulmeister [3], who argued that positive attitudes, shaped by various internal and external factors, lead to actionable intentions in the context of renewable energy adoption. In Lebanon, where renewable energy solutions are essential to addressing the country‘s energy crises, these results suggest that improving public perception and awareness about the benefits of solar energy will be crucial in encouraging wider adoption.

Thus, it can be concluded that positive influences on attitudes toward solar energy come from green concern, subjective norms, social influence, and especially functional utility or the perceived usefulness and functionality of solar energy, demonstrating that concern for the environment and the practical benefits of solar energy are crucial in forming favorable attitudes. Regulations, however, have an unexpectedly negative effect on attitudes, possibly indicating dissatisfaction with the current regulatory environment or perceived constraints. A positive attitude toward solar energy significantly enhances the likelihood of purchasing solar energy products. These results underline the importance of promoting the functional and environmental benefits of solar energy to improve consumer attitudes and drive purchase intentions.

5.2. Theoretical Implications

This study approaches the issues related to the consumer behavioral pattern toward renewable energy. From a theoretical point of view, this study provides valuable new insights into the expansion of the literature on consumer perceptions of renewable energy. The study discusses the impact of several key factors that influence consumers’ behavior toward solar energy acquisition. In analogy to the literature review, the findings show that the various factors considered in TRA and TPB models adopted in similar studies have a positive and significant influence on the consumer adoption of renewable energy. In addition, it did highlight that the financial burden of the investment in solar energy did not have a negative influence on consumer adoption of renewable energy. In this perspective, and in line with the results, studying the consumer acquisition process would necessitate the consideration of those factors considered in this study that were similarly identified in different studies stated previously. These factors are concern toward a green environment, personal or subjective motivations, social influence, functional utility or the perceived usefulness and functionality of solar energy, and behavioral constraints related to laws and regulations.

5.3. Practical Implications

The suggested practical implications would cover two sectors which are the private sector and the public sector. The private sector should increase consumer awareness of the environmental impact and advantages and values of renewable energy by investing in marketing campaigns and promoting it on social media platforms. Additionally, amid the economic crisis, the private sector should promote payment methods by which to ease the pain of a large upfront solar investment in order to stimulate it further down the purchase decision process and should invest in customer care and service to ensure prompt interaction with any complaints and with the after-sales services. The public sector should include regulatory laws to encourage consumers to invest in solar energy and offer financial incentives such as tax reductions to companies investing in renewable energies.

5.4. Contributions of the Study

The contributions of this study are as follows:

- Comprehensive framework: This research provides a comprehensive and integrated approach to understanding the factors that shape and enhance consumer behavior toward renewable energy, particularly solar energy. It meticulously identifies the key factors influencing consumer behavior and clearly delineates the relationships between these factors and the intention to invest in solar energy systems.

- Theoretical and empirical integration: The study’s integrated model represents a significant contribution to academic research, as it combines both theoretical and empirical approaches to identify and validate the relevant determinants of consumer behavior in the context of renewable energy.

- Holistic understanding: By bridging theoretical insights with robust statistical analysis, the research offers a nuanced understanding of how environmental concerns, personal motives, social influences, perception, and governmental intervention collectively influence consumer attitudes and intentions.

- Extension of existing knowledge: This study extends the existing body of knowledge by providing a holistic framework that can be applied in future research to explore consumer behavior in other renewable energy contexts.

5.5. Limitations and Future Research

The underpinning theories were limited to the TRA and TPB; thus, other suitable theories could be included in future studies. Additionally, the moderating impact of social demographics on behavior was not included in the statistical analysis. Future studies could develop a more comprehensive measurement scale that would include additional factors and variables. Another limitation is that this study relies solely on self-reported attitudes, without an independent assessment of observed purchase or energy consumption behaviors due to the unavailability of data. Thus, future research could integrate longitudinal data collection or field experiments to track actual purchasing decisions over time. This would allow for a deeper understanding of how the attitudes and intentions identified in the current study translate into real-world actions. Additionally, future research could explore partnerships with energy providers to track actual electricity usage, allowing for a more accurate examination of the link between attitudes and behavior. This would provide a clearer picture of how self-reported motivations translate into real-world energy consumption patterns, thus strengthening the analysis of consumer behavior toward renewable energy adoption. Future studies could also analyze the effect of consumer income on consumer decisions, as this will help marketers of solar energy systems to set more appropriate product diversification strategies, resulting in an accelerated propagation of solar energy investment among a large number of users, which will in turn alleviate the energy crisis that is currently coupled with an economic crisis.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at: https://www.mdpi.com/article/10.3390/su16208777/s1, The questionnaire was uploaded as a supplementary file.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, N.J.A.M., E.S., D.I. and N.S.; methodology, N.J.A.M., E.S. and D.I.; formal analysis, E.S.; writing—original draft preparation, N.J.A.M. and D.I.; investigation, D.I.; writing—review and editing, N.J.A.M. and N.S. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki and approved by the Institutional Review Board of the Holy Spirit University of Kaslik (protocol code HCR/EC 2023-039 on 1 October 2023). Ethical approval was uploaded to the system.

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study. We used an electronic click consent option within the survey questionnaire, where participants confirmed their consent before proceeding.

Data Availability Statement

Data collected from participants answering the questionnaire are available upon request due to privacy and ethical restrictions.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Elrick-Barr, C.E.; Zimmerhackel, J.S.; Hill, G.; Clifton, J.; Ackermann, F.; Burton, M.; Harvey, E.S. Man-made structures in the marine environment: A review of stakeholders’ social and economic values and perceptions. Environ. Sci. Policy 2022, 129, 12–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Loucks, D.P. Impacts of climate change on economies, ecosystems, energy, environments, and human equity: A systems perspective. In The Impacts of Climate Change; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2021; pp. 19–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schulmeister, S. Fixing rising price paths for fossil energy: Basis of a “green growth” without rebound Effects. In Climate Change in Regional Perspective: European Union and Latin American Initiatives, Challenges, and Solutions; Springer Nature: Cham, Switzerland, 2024; pp. 89–111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kanwal, S.; Mehran, M.T.; Hassan, M.; Anwar, M.; Naqvi, S.R.; Khoja, A.H. An integrated future approach for the energy security of Pakistan: Replacement of fossil fuels with syngas for better environment and socio-economic development. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2022, 156, 111978. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salem, H.S.; Pudza, M.Y.; Yihdego, Y. Harnessing the energy transition from total dependence on fossil to renewable energy in the Arabian Gulf region, considering population, climate change impacts, ecological and carbon footprints, and United Nations’ Sustainable Development Goals. Sustain. Earth Rev. 2023, 6, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dagher, L.; Jamali, I.; Abi Younes, O. Extreme energy poverty: The aftermath of Lebanon’s economic collapse. Energy Policy 2023, 183, 113783. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramadan, D. Shock Value: A Study of Energy Access, Resilience, and How Public-Private Electricity Distribution Can Bring Energy Justice to Lebanon; The American University of Paris (France): Paris, France, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Han, H. Consumer behavior and environmental sustainability in tourism and hospitality: A review of theories, concepts, and latest research. In Sustainable Consumer Behaviour and the Environment; Routledge: London, UK, 2021; pp. 1–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schüler, M.; Fee Maier, M.; Liljedal, K.T. Motives and barriers affecting consumers’ co-creation in the physical store. Int. Rev. Retail. Distrib. Consum. Res. 2020, 30, 289–310. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Durmaz, Y.; Diyarbakırlıoğlu, I. A Theoritical Approach to the Strength of Motivation in Customer Behavior. Glob. J. Hum. Soc. Sci. 2011, 11, 36–42. [Google Scholar]

- Duygun, A.; Şen, E. Evaluation of consumer purchasing behaviors in the COVID-19 pandemic period in the context of Maslow’s hierarchy of needs. PazarlamaTeorisi Ve Uygulamaları Derg. 2020, 6, 45–68. [Google Scholar]

- Ghatak, S.; Singh, S. Examining Maslow’s hierarchy need theory in the social media adoption. FIIB Bus. Rev. 2019, 8, 292–302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prabhu, J.J. A study and analysis of consumer behavior and factor influencing in marketing. Int. Res. J. Mod. Eng. 2020, 2, 68–76. [Google Scholar]

- Kotler, P.; Keller, K.L.; Ancarani, F.; Costabile, M. Marketing Management 14/e; Pearson: London, UK, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Cherian, J.; Jacob, J. Green marketing: A study of consumers’ attitude towards environment friendly products. Asían Soc. Sci. 2012, 8, 117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chou, S.F.; Horng, J.S.; Liu CH, S.; Lin, J.Y. Identifying the critical factors of customer behavior: An integration perspective of marketing strategy and components of attitudes. J. Retail. Consum. Serv. 2020, 55, 102113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, Q.; Zhao, S. Determinants of consumers’ willingness to buy counterfeit luxury products: An empirical test of linear and inverted u-shaped relationship. Sustainability 2021, 13, 1194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Argyriou, E.; Melewar, T.C. Consumer attitudes revisited: A review of attitude theory in marketing research. Int. J. Manag. Rev. 2011, 13, 431–451. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Solomon, M.; Russell-Bennett, R.; Previte, J. Consumer Behaviour; Pearson Higher Education AU: Sydney, NSW, Australia, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Sands, P. Environmental protection in the twenty-first century: Sustainable development and international law. In The Global Environment; Routledge: London, UK, 2023; pp. 116–137. [Google Scholar]

- Bal, M.; Stok, M.; Bombaerts, G.; Huijts, N.; Schneider, P.; Spahn, A.; Buskens, V. A fairway to fairness: Toward a richer conceptualization of fairness perceptions for just energy transitions. Energy Res. Soc. Sci. 2023, 103, 103213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stenseke, M. Agenda 2030 and the green economy. In Research Handbook on the Green Economy; Edward Elgar Publishing: Northampton, MA, USA, 2024; pp. 81–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, S. Energy crisis and climate change: Global concerns and their solutions. In Energy: Crises, Challenges and Solutions; Wiley: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2021; pp. 1–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Majid, M. Renewable energy for sustainable development in India: Current status, future prospects, challenges, employment, and investment opportunities. Energy Sustain. Soc. 2020, 10, 1–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Corkish, R.; Lipiński, W.; Patterson, R.J. Introduction to solar energy. In Solar Energy; World Scientific: Singapore, 2016; pp. 1–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pandey, A.K.; Kumar, R.R.; Kalidasan, B.; Laghari, I.A.; Samykano, M.; Kothari, R.; Abusorrah, A.M.; Sharma, K.; Tyagi, V.V. Utilization of solar energy for wastewater treatment: Challenges and progressive research trends. J. Environ. Manag. 2021, 297, 113300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharma, A.P. Consumers’ purchase behaviour and green marketing: A synthesis, review and agenda. Int. J. Consum. Stud. 2021, 45, 1217–1238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nath, P.; Siepong, A. Green marketing capability: A configuration approach towards sustainable development. J. Clean. Prod. 2022, 354, 131727. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chung, K.C. Green marketing orientation: Achieving sustainable development in green hotel management. J. Hosp. Mark. Manag. 2020, 29, 722–738. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dahhan, A.; Arenkov, I.A. Green marketing as a trend towards achieving sustainable development. Экoнoмика Предпринимательствo И Правo 2021, 11, 2497–2512. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nekmahmud, M.; Fekete-Farkas, M. Why not green marketing? Determinates of consumers’ intention to green purchase decision in a new developing nation. Sustainability 2020, 12, 7880. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, P.C.; Wang, H.M.; Huang, H.L.; Ho, C.W. Consumer attitude and purchase intention toward rooftop photovoltaic installation: The roles of personal trait, psychological benefit, and government incentives. Energy Environ. 2020, 31, 21–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vu, D.M.; Ha, N.T.; Ngo TV, N.; Pham, H.T.; Duong, C.D. Environmental corporate social responsibility initiatives and green purchase intention: An application of the extended theory of planned behavior. Soc. Responsib. J. 2022, 18, 1627–1645. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Asante, D.; Ampah, J.D.; Afrane, S.; Adjei-Darko, P.; Asante, B.; Fosu, E.; Dankwah, D.A.; Amoh, P.O. Prioritizing strategies to eliminate barriers to renewable energy adoption and development in Ghana: A CRITIC-fuzzy TOPSIS approach. Renew. Energy 2022, 195, 47–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vermeir, I.; Weijters, B.; De Houwer, J.; Geuens, M.; Slabbinck, H.; Spruyt, A.; Van Kerckhove, A.; Van Lippevelde, W.; De Steur, H.; Verbeke, W. Environmentally sustainable food consumption: A review and research agenda from a goal-directed perspective. Front. Psychol. 2020, 11, 1603. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Trotta, G.; Kalmi, P.; Kazukauskas, A. The role of energy literacy as a component of financial literacy: Survey-based evidence from Finland. In Heading towards Sustainable Energy Systems: Evolution or Revolution? 15th IAEE European Conference; International Association for Energy Economics: Vienna, Austria, 2017; pp. 3–6. [Google Scholar]

- Mushtaq, B.; Bandh, S.A.; Shafi, S. Environmental Management: Environmental Issues, Awareness and Abatement; Springer Nature: Cham, Switzerland, 2020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dinu, M.; Pătărlăgeanu, S.R.; Petrariu, R.; Constantin, M.; Potcovaru, A.M. Empowering sustainable consumer behavior in the EU by consolidating the roles of waste recycling and energy productivity. Sustainability 2020, 12, 9794. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dalila, D.; Latif, H.; Jaafar, N.; Aziz, I.; Afthanorhan, A. The mediating effect of personal values on the relationships between attitudes, subjective norms, perceived behavioral control and intention to use. Manag. Sci. Lett. 2020, 10, 153–162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Indriani IA, D.; Rahayu, M.; Hadiwidjojo, D. The influence of environmental knowledge on green purchase intention the role of attitude as mediating variable. Int. J. Multicult. Multireligious Underst. 2019, 6, 627–635. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pratama AA, N.; Hamidi, M.L.; Cahyono, E. The effect of halal brand awareness on purchase intention in indonesia: The mediating role of attitude. Cogent Bus. Manag. 2023, 10, 2168510. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gibbons, R. Exploring Consumer Perception and Attitudes towards Renewable Energy with a View to Developing Best Practice for Marketing Renewable Energy. Master’s Thesis, Letterkenny Institute of Technology, Letterkenny, Ireland, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Wall, W.P.; Khalid, B.; Urbański, M.; Kot, M. Factors influencing consumer’s adoption of renewable energy. Energies 2021, 14, 5420. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Polcyn, J.; Us, Y.; Lyulyov, O.; Pimonenko, T.; Kwilinski, A. Factors influencing the renewable energy consumption in selected European countries. Energies 2021, 15, 108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khalid, B.; Urbański, M.; Kowalska-Sudyka, M.; Wysłocka, E.; Piontek, B. Evaluating consumers’ adoption of renewable energy. Energies 2021, 14, 7138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Loan, C.T.K. Factors Influencing Green Purchase Intention of Students: A Case Study at Vietnam National University of Agriculture: Factors influencing green purchase intention of students: A case study at Vietnam National University of Agric. Vietnam. J. Agric. Sci. 2020, 3, 732–745. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stango, V.; Zinman, J. We are all behavioural, more, or less: A taxonomy of consumer decision-making. Rev. Econ. Stud. 2023, 90, 1470–1498. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elmustapha, H.; Hoppe, T. Challenges and opportunities of business models in sustainable transitions: Evidence from solar energy niche development in Lebanon. Energies 2020, 13, 670. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ajzen, I. The Theory of planned behavior. Organ. Behav. Hum. Decis. Process. 1991, 50, 179–211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zolait, A.H.S. The nature and components of perceived behavioural control as an element of theory of planned behaviour. Behav. Inf. Technol. 2014, 33, 65–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elahi, E.; Khalid, Z.; Zhang, Z. Understanding farmers’ intention and willingness to install renewable energy technology: A solution to reduce the environmental emissions of agriculture. Appl. Energy 2022, 309, 118459. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maichum, K.; Parichatnon, S.; Peng, K.C. Application of the extended theory of planned behavior model to investigate purchase intention of green products among Thai consumers. Sustainability 2016, 8, 1077. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Minton, E.A.; Spielmann, N.; Kahle, L.R.; Kim, C.H. The subjective norms of sustainable consumption: A cross-cultural exploration. J. Bus. Res. 2018, 82, 400–408. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Setyo, W.; Mukhamad, N.; Ujang, S.; Yudha, A. Broadening influence: Scale development for subjective norms across extended social groups in green purchasing. Environ. Soc. Psychol. 2024, 9, 2940. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wolske, K.S.; Gillingham, K.T.; Schultz, P.W. Peer influence on household energy behaviours. Nat. Energy 2020, 5, 202–212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alhamad, A.; Ahmed, E.R.; Akyürek, M.; Baadhem, A.M.S. The impact of environmental awareness and attitude on green purchase intention: An empirical study of turkish consumers of green product. Mal. Turgut Özal Üniversitesi İşletme Ve Yönetim Bilim. Derg. 2023, 4, 22–36. [Google Scholar]

- Anvar, M.; Venter, M. Attitudes and purchase behaviour of green products among generation Y consumers in South Africa. Mediterr. J. Soc. Sci. 2014, 5, 183–194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bahl, S.; Chandra, T. Impact of marketing mix on consumer attitude and purchase intention towards ‘green’ products. A J. Res. Artic. Manag. Sci. Allied Areas (Ref.) 2018, 11, 1–11. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, T.B.; Chai, L.T. Attitude towards the environment and green products: Consumers’ perspective. Manag. Sci. Eng. 2010, 4, 27. [Google Scholar]

- Lestari, E.R.; Hanifa, K.P.U.; Hartawan, S. Antecedents of attitude toward green products and its impact on purchase intention. In IOP Conference Series: Earth and Environmental Science; IOP Publishing: Bristol, UK, 2020; Volume 515, No. 1, p. 012073. [Google Scholar]

- Mehta, P.; Chahal, H.S. Consumer attitude towards green products: Revisiting the profile of green consumers using segmentation approach. Manag. Environ. Qual. Int. J. 2021, 32, 902–928. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sahioun, A.; Bataineh, A.Q.; Abu-AlSondos, I.A.; Haddad, H. The impact of green marketing on consumers’ attitudes: A moderating role of green product awareness. Innov. Mark. 2023, 19, 237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Souri, M.E.; Sajjadian, F.; Sheikh, R.; Sana, S.S. Grey SERVQUAL method to measure consumers’ attitudes towards green products-A case study of Iranian consumers of LED bulbs. J. Clean. Prod. 2018, 177, 187–196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, Y.; Wang, X.; Lu, P. Chinese consumer attitude and purchase intent towards green products. Asia-Pac. J. Bus. Adm. 2014, 6, 84–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Walia, S.B.; Kumar, H.; Negi, N. Consumers’ attitude and purchase intention towards ‘green’ products: A study of selected FMCGs. Int. J. Green Econ. 2019, 13, 202–217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bellomo, M.; Pleyers, G. Sustainable Cosmetics: The Impact of Packaging Materials, Environmental Concern and Subjective Norm on Green Consumer Behaviour. DIAL Digital Access to Libraries Université Catholique de Louvain. 2021. Available online: https://dial.uclouvain.be/memoire/ucl/en/object/thesis%3A31245 (accessed on 5 October 2023).

- Lin, S.T.; Niu, H.J. Green consumption: Environmental knowledge, environmental consciousness, social norms, and purchasing behavior. Bus. Strategy Environ. 2018, 27, 1679–1688. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yadav, R.; Pathak, G.S. Young consumers’ intention towards buying green products in a developing nation: Extending the theory of planned behavior. J. Clean. Prod. 2016, 135, 732–739. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chan, H.W.; Udall, A.M.; Tam, K.P. Effects of perceived social norms on support for renewable energy transition: Moderation by national culture and environmental risks. J. Environ. Psychol. 2022, 79, 101750. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pagliuca, M.M.; Panarello, D.; Punzo, G. Values, concern, beliefs, and preference for solar energy: A comparative analysis of three European countries. Environ. Impact Assess. Rev. 2022, 93, 106722. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abreu, J.; Wingartz, N.; Hardy, N. New trends in solar: A comparative study assessing the attitudes towards the adoption of rooftop PV. Energy Policy 2019, 128, 347–363. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cousse, J. Still in love with solar energy? Installation size, affect, and the social acceptance of renewable energy technologies. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2021, 145, 111107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Irfan, M.; Elavarasan, R.M.; Hao, Y.; Feng, M.; Sailan, D. An assessment of consumers’ willingness to utilize solar energy in China: End-users’ perspective. J. Clean. Prod. 2021, 292, 126008. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Irfan, M.; Zhao, Z.Y.; Li, H.; Rehman, A. The influence of consumers’ intention factors on willingness to pay for renewable energy: A structural equation modeling approach. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 2020, 27, 21747–21761. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Perlaviciute, G.; Steg, L. The influence of values on evaluations of energy alternatives. Renew. Energy 2015, 77, 259–267. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rai, V.; Beck, A.L. Public perceptions and information gaps in solar energy in Texas. Environ. Res. Lett. 2015, 10, 074011. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sütterlin, B.; Siegrist, M. Public acceptance of renewable energy technologies from an abstract versus concrete perspective and the positive imagery of solar power. Energy Policy 2017, 106, 356–366. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Axsen, J.; Kurani, K.S. Social influence, consumer behavior, and low-carbon energy transitions. Annu. Rev. Environ. Resour. 2012, 37, 311–340. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aziz, N.S.; Wahid, N.A.; Sallam, M.A.; Ariffin, S.K. Factors influencing Malaysian consumers’ intention to purchase green energy: The case of solar panel. Glob. Bus. Manag. Res. 2017, 9, 328–346. [Google Scholar]

- Elmustapha, H.; Hoppe, T.; Bressers, H. Consumer renewable energy technology adoption decision-making; comparing models on perceived attributes and attitudinal constructs in the case of solar water heaters in Lebanon. J. Clean. Prod. 2018, 172, 347–357. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arshiya Fathima, M.S.; Batcha, H.M.; Alam, A.S. Factors affecting consumer purchase intention for buying solar energy products. Int. J. Energy Sect. Manag. 2023, 17, 820–839. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arshiya Fathima, M.S.; Khan, A.; Alam, A.S. A Bibliometric Review of Consumers’ Purchase Behaviour for Solar Energy Products. Int. J. Energy Sect. Manag. 2023. ahead of print. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kratschmann, M.; Dütschke, E. Selling the sun: A critical review of the sustainability of solar energy marketing and advertising in Germany. Energy Res. Soc. Sci. 2021, 73, 101919. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, H. Consumer Behavior, Social Influence, and Smart Grid Implementation. Ph.D. Thesis, Institut für Sozialwissenschaften der Universität Stuttgart, Stuttgart, Germany, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Liang, X.; Hu, X.; Islam, T.; Mubarik, M.S. Social support, source credibility, social influence, and solar photovoltaic panels purchase intention. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 2021, 28, 57842–57859. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arroyo, P.; Carrete, L. Motivational drivers for the adoption of green energy: The case of purchasing photovoltaic systems. Manag. Res. Rev. 2019, 42, 542–567. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kowalska-Pyzalska, A. What makes consumers adopt to innovative energy services in the energy market? A review of incentives and barriers. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2018, 82, 3570–3581. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hille, E. Europe’s energy crisis: Are geopolitical risks in source countries of fossil fuels accelerating the transition to renewable energy? Energy Econ. 2023, 127, 107061. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]