Abstract

Outdoor running has a positive impact on human health. Our study attempted to address the issue of what other aspects motivate people to take up running. We were particularly interested in the landscape and its significance at the stage of decision making regarding participation in races. Our goal was also to identify the landscape features of routes, which determine their popularity. We conducted surveys among running participants and spatial analyses using GIS tools. Great landscape values of running routes can contribute to the activation of a running society, especially those including women and city dwellers. The high diversity of the landscape of cross-country routes, especially in terms of their relief and land use, significantly affects their high landscape rating. Route profiles and running challenges are as important as landscape values. The landscape that runners observe during long-distance runs affects their regeneration and motivates them to finish competitions. Runs organised in mountain and foothill landscapes, characterised by a wide variety of landscapes, are particularly attractive for runners. This study illuminates how the enchanting tapestry of landscapes not only fuels the passion for outdoor running but also underscores the intricate relationship between humans and their surroundings. The results enable us to establish the key principles for designing new running routes that support runners during their exertion.

1. Introduction

The environment in which a person lives affects their behaviour and mood [1] and, consequently, their physical [2] and mental health [3]. Spatial features can positively stimulate one’s physical activity and are undertaken in various social and individual spheres [4,5,6,7]. Often, these features are associated with broadly understood beauty, aesthetics and harmony, as well as safety [8,9]. The positive health effects of attractive environments for athletes are well documented. For example, exercising in nature, in a natural environment, also referred to as “green exercise” [10], is associated with greater physical and mental health benefits, including lowered blood pressure, reduced stress and improved mood, positive effects on self-esteem and a better perception of health and well-being [11,12,13,14].

Increasing public participation in sport and physical activity is an important goal of health policy in countries around the world [15,16,17]. Participation in sport is associated with positive health benefits [17,18]. In particular, the positive effects of running as an integral part of an active and healthy lifestyle are emphasised [19,20]. In recent decades, running has grown rapidly in popularity as it is a natural and simple form of activity available to many people. Running is increasingly becoming a ”lifestyle sport” [19]. The latest research shows that out of a group of 10 countries surveyed, an average of 4 out of 10 people say that they run [21]. The frequency and intensity of running are important in achieving a certain level of fitness, and the type and quality of the environment in which a person runs are important for a range of health benefits. A variety of studies show that some environments can facilitate and enhance the health benefits of running, while others hinder them. Therefore, it matters where (e.g., in what geographic location, indoors or outdoors) a person runs [22,23]. Therefore, running routes should run through high-quality green areas related to the idea of green infrastructure [24], which is an important element connecting various forms of slow mobility in natural environments [25]. Green infrastructure promotes the development of a sustainable environment, ensuring a higher quality of life [26]. The integration of pedestrian (including running), cycling and horse trails with the concept of green infrastructure allows for the utilisation of ecosystem services within the context of a connected bioregion [25].

Promotion of running activities in attractive environmental conditions is carried out, e.g., by organising running events in valuable cultural landscapes. Such activities have a centuries-old tradition dating back to the end of the 19th century, when the premiere edition of the Boston Marathon took place [27]. Currently, numerous urban centres pride themselves on organising mass competitions, the largest of which are the Chicago Marathon and the London Marathon [21]. Urban marathons are for many people a combination of sightseeing and sport (so-called sports tourism) [28]. The routes of the most beautiful marathons lead through popular districts, next to the most famous monuments or to the most charming alleys of cities. In Poland, the first mass urban running events were held at the end of the 1970s, but initially, they had a small social scope. The beginning of the 21st century is a period of particular dissemination of running in Poland on a mass scale. Since the beginning of this period, there has been a quantitative increase in running events, which stabilised in 2016. Currently, in almost every large- and medium-sized city, runs at various distances are held every year [27,29].

An alternative to running in the urban environment are competitions, the routes of which lead through natural landscapes, covered with forests and meadows, or along rivers and even along seaside cliffs. Participants of such races as the Big Sur International Marathon, the Great Wall Marathon or the Australian Outback Marathon have the opportunity to absorb breathtaking views during physical effort. The distance of runs taking place in unusual natural scenery often exceeds the distance of a marathon (42.195 km)—these are the so-called ultra-runs. Overcoming such long-distance routes, characterised by various terrain obstacles, requires special motivation. Ultra-runners emphasise that the impressive views they can observe during a run are a great source of motivation and mobilisation for them to continue running [runners-world.pl]. Scientific research confirms that natural surroundings and attractive landscapes effectively support the body’s regeneration process, positively affecting mental health [30].

There is evidence confirming the high pro-health value of physical activity taking place outdoors, especially when surrounded by greenery. It seems obvious that the primary reason people take up running is to care for their health and well-being and develop physical fitness [31,32,33]. It was also confirmed that running events have been important social events for many years, in which not only the runners themselves participate but so too do local organisers, volunteers, fans and spectators [34]. If we want to promote running, which is an activity that does not require financial outlays and can be practiced almost anywhere, it seems important to look for additional arguments relevant to people taking up this activity or planning to start it. Our literature review shows that respondents appreciate the environmental values of trails, but there is no detailed research on this subject, which is why this aspect is the essence of our research. The main research problem was assessing the importance of the landscape when making decisions about participating in an organised run. We asked ourselves and the people to whom we sent the surveys the following questions: Is the landscape an important aspect motivating you to take part in organised runs? What landscape values of the routes of running competitions determine their popularity? We were also interested in whether landscape values were equally important to all respondents, regardless of gender, age and place of residence (Figure 1). In addition, the implementation of our research allows us to formulate guidelines that can be helpful to landscape architects, planners and organisations involved in shaping competition running routes and promoting an active lifestyle.

Figure 1.

The scheme of connections between research questions, methods and the main research objective.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Survey Study

Quantitative research was conducted in the form of an anonymous online survey created using docs.google.com. The survey was distributed via Polish online running groups (Facebook) in the period from April to July in 2021.

The online survey consisted of four parts. Part one (metrics) included four questions about (1) age, (2) gender, (3) place of residence (city, town, village) and (4) province/voivodeship). This section contained two questions, in which respondents were asked about their frequency of participation in street running events within one year and asked respondents to name a street race they consider to have the most scenic landscape (questions: (1) How many Street Runs did you participate in during the year? and (2) Which of these runs do you consider to have the most attractive landscape?). The next part, dedicated to mountain running (taking place in mountain areas) and route running (organized in a natural environment, on a natural surface), had a similar format (frequency of participation and indicating the race with the most attractive landscape). The questions in this section were as follows: (1) How many trail or mountain runs did you participate in during the year? and (2) Which of these runs do you consider to have the most attractive landscape? The last part consisted of questions about motivation and reasons why our respondents take up running activities (question 1: What is most important to you when choosing a run to participate in?). In a multiple-choice question, respondents could select their key motivations (up to 3), including options such as (a) distance/length of the race, (b) trail profile, (c) scenic beauty/landscape, (d) proximity to place of residence, (e) charitable purpose of the race, (f) type/amount of prize(s), (g) opportunity for competition, (h) opportunity to test one’s abilities, (i) health aspects, (j) cost/registration fee and (k) other. The next question was: Do landscape features of the route have significant importance to you when choosing a run? Runners could choose their answer from 5 options: (a) definitely yes, (b) probably yes, (c) hard to say, (d) probably not and (e) definitely not. In this section of the survey, there was also a question about whether runners observe the landscape during their run (respondents could choose from the options: (a) yes, always; (b) only if something catches my attention; and (c) I don’t pay attention to the surroundings during the run). The last question of the survey was: Landscape features and the attractiveness of the surroundings are most significant in which types of runs? Respondents had the multiple-choice option to choose their answers from the following options: (a) in all types of runs, (b) in races and mountain runs, (c) in 5–10 km races, (d) in half marathons, (e) in marathons, (f) In ultramarathons and (g) other.

2.2. Spatial Analyses

The routes most often indicated by the respondents as attractive in terms of landscape were characterised using indicators calculated in the GIS environment. For each of the selected routes, the following were determined: 3D length, diversity of terrain (minimum, maximum and average altitude values above sea level; sum of elevation gains; average and maximum decreases), percentage share of the length of paths running through protected areas and various types of land use. All relief analyses were performed in 1 m intervals, and distances were determined along the 3D surface.

The landscape characteristics of the running routes were made on the basis of the following digital data obtained from the Geoportal of Spatial Management Infrastructure [www.geoportal.gov.pl] (accessed on 6 December 2023):

- Digital Terrain Model (DEM)—files containing height values of points in a regular grid with a mesh of 1 m, interpolated on the basis of a cloud of points from aerial laser scanning (LiDAR). The average data error does not exceed 0.2 m;

- Database of Topographic Objects (BDOT10k)—a vector database containing the spatial location of topographic objects along with their land cover characteristics. The content and detail of the BDOT10k database correspond to a 1:10,000 topographic map;

- LAS—binary files containing a point cloud derived from airborne laser scanning (LiDAR). These files contain, e.g., information on point classes, which can be described as low, medium and high vegetation, buildings and infrastructure, water and soil. In addition, points from multiple coverage areas, unclassified points and noise are also distinguished.

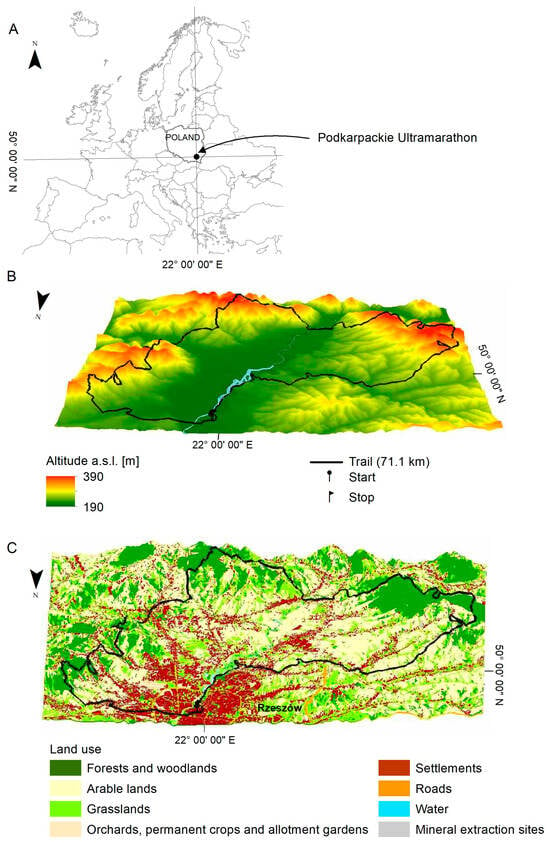

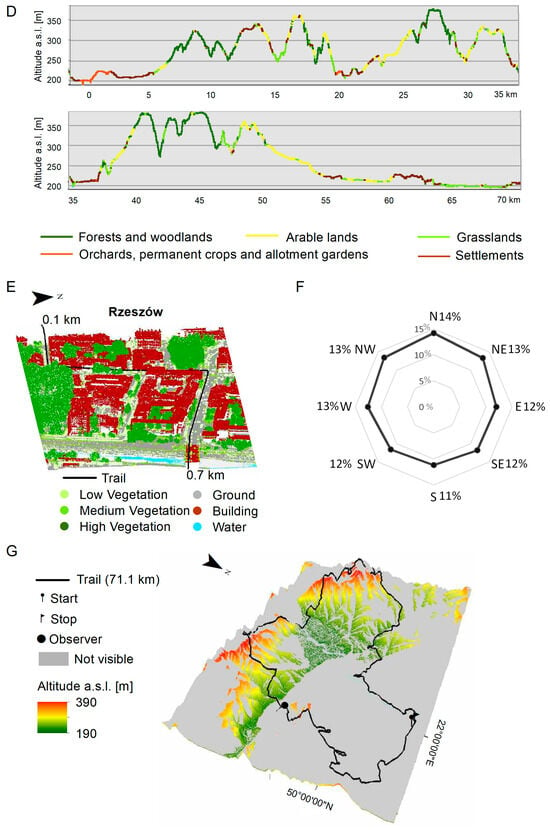

Case Study: Podkarpackie Ultramarathon

Extended spatial analyses were conducted for the Podkarpackie Ultramarathon (UP), which was among the most frequently chosen by respondents. It combines features typical of both urban street running and rural trail running, spanning through a city of nearly 200,000 inhabitants and various surrounding landscapes and landforms. Detailed analyses including assessments of changes in land use concerning the topography, visibility and exposure are presented in Section 3.4.

Spatial analyses were performed using ArcGIS Pro 2.9 software.

2.3. Statistical Analyses

The questionnaire data were compiled in multi-way tables. Then, the relationship between the frequency distribution of respondents’ responses depending on the following nominal variables was assessed: age, sex and place of living; this was investigated using a nonparametric χ2 test. Using nonparametric tests, the row data were also compared in relation to sex (Mann–Whitney U test), age and place of living (Kruskal–Wallis test). These tests were applied to check whether the analysed statistical samples (two or more) came from the same general population. The selection of these statistical tests depended on the fact that the data did not meet the required assumptions, e.g., normal distribution and homogeneity of variances, as examined by Shapiro–Wilk and Brown–Forsyth tests, respectively. The multivariate technique DCA (detrended correspondence analysis) was applied to indicate the most important criteria for choosing a run by a runner. The respondents’ answers were coded as 0 (no criterion selected) and 1 (criterion selected). The results were illustrated by scatterplot. Statistical tests and multivariate techniques were performed using STATISTICA 13.0 and Canoco 5, respectively.

3. Results

3.1. Running Activity from the Perspective of Gender, Age and Place of Residence

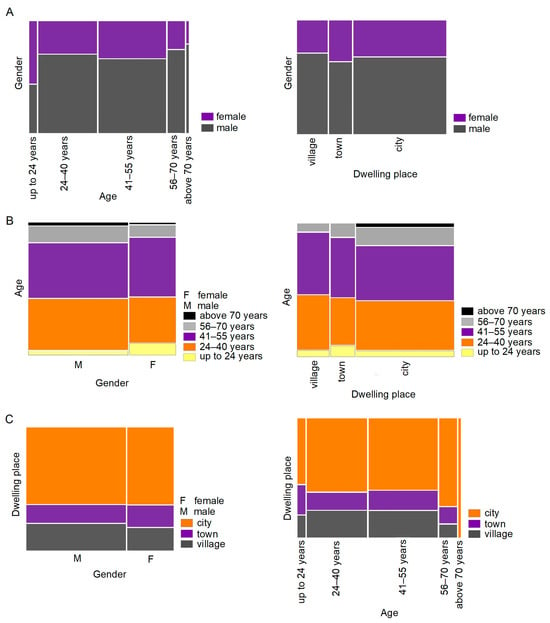

A total of 322 people responded to the survey, most of whom (68%) were men (Figure 2A). The respondents were mainly people from cities (64%) (Figure 2C), aged 24–55 (82%) (Figure 2B). There were no statistically significant differences between the proportion of male and female runners depending on the place of residence (χ2 = 0.773; p = 0.6793) and age (χ2 = 6.017; p = 0.1978). Among men, inhabitants of small towns accounted for only 13%, which is twice as low as in the case of inhabitants of rural areas and three times lower than in the case of inhabitants of cities. Rural women participated in runs less often than men, but it depended on their age. The youngest (under 24) and the oldest (over 70) were the least numerous groups. Only four people over 70 years of age responded to the survey, and only one woman was among them. They all lived in cities. Respondents aged 56–70 were also part of a small group (36 people living mainly in the city); among them, 75% were men. Regardless of the place of residence, the number of runners in different age groups was similar (χ2 = 7.117; p = 0.5240). Out of 141 respondents aged 41–55 (44%), 23% were rural residents, compared to 61% urban residents. An almost identical distribution was found in the 24–40 age group and a very similar distribution was found in the 24-year-old group (Figure 2). To sum up, it can be said that Polish runners are dominated by men living in cities in a wide age range, i.e., 24–55 years old.

Figure 2.

Running activity in relation to gender (A), age (B) and place of residence (C).

3.2. Running Activities in the Context of the Criterion for Choosing the Type and Attributes of Running

Detailed statistical analyses showed that the number of respondents declaring participation in street runs was statistically significantly higher than that in mountain or trail runs, 61% (280 people) and 45% (210 people), respectively. The number of street runs in which the respondents participated ranged from 1 to 56 (Me = 5), while that of mountain and trail runs ranged from 1 to 23 (Me = 3). Regardless of the type of run, there were about twice as many men. In the case of street runs, women participated in runs with the same frequency as men (Z = 0.495, p = 0.621); in the case of mountain or trail runs, women ran slightly less frequently during the year (Z = −2.853, p = 0.004). Both types of runs, regardless of gender, were attended by runners aged 24 to 55, which accounted for about 80%. They were mainly city dwellers, about 63%, regardless of gender. Place of residence (H = 0.184; p = 0.912) and age (H = 2.117; p = 0.713) were not factors determining how many runs respondents participated in.

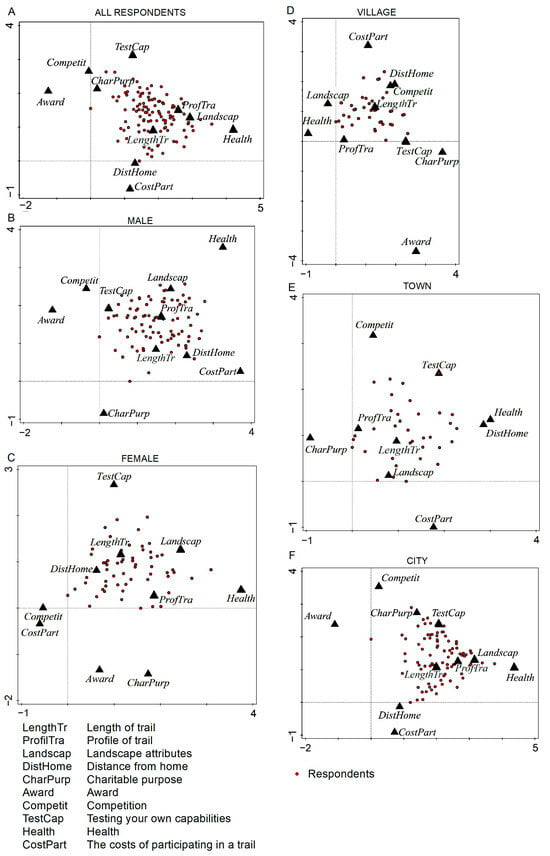

Route choice was dictated by various factors. When choosing a run, the respondents were mainly guided by the trail profile (186 people), and this was more important for men. A total of 163 people also chose running routes characterised by high landscape values, mainly those living in cities and towns. The next was the length of trail, regardless of gender and place of residence. Women decided to participate in trail runs when taking into account practical criteria such as distance from home as well as difficulty expressed in length and profile. Unlike men, self-testing was not an important factor they considered. When choosing a run, the respondents were also guided by health aspects, especially city dwellers. For runners, both women and men, and regardless of where they lived, irrelevant factors were award as well as cost. For some villagers, the opportunity to compete was important. Few considered charity purpose (Figure 3A–F).

Figure 3.

DCA plot illustrating the importance of criteria for gear selection. (A) All respondents; (B) male; (C) female, (D) respondents from village, (E) town, (F) city.

3.3. Trail Landscape Attributes and Landscape Perception

Respondents participated in 127 different street runs and 106 different trail or mountain runs. Among the street runs, the most popular were the Cracovia Marathon (42.2 km) and the Warsaw Half Marathon (21.1 km), held in large cities (population over 800,000). The routes are laid out in places attractive to tourists; they run through old city districts and recreation areas, along large river valleys, extensive parks and even through a zoo. Despite this, street running was not perceived by the respondents as attractive in terms of landscape.

Six competition routes enjoyed popularity among runners who preferred non-urbanised running scenery, including the Rzeźnik Run (BRz) (80.6 km) and Krynica 7 Valleys Run Festival (B7DK) (100.1 km). Both routes run through mountain ranges rising to 1000–1200 m above sea level. Each route crosses deeply cut river valleys several times and then climbs up steep slopes to the mountain peaks. Both routes have been marked out in areas frequented by hikers and in the vicinity of well-known health resorts.

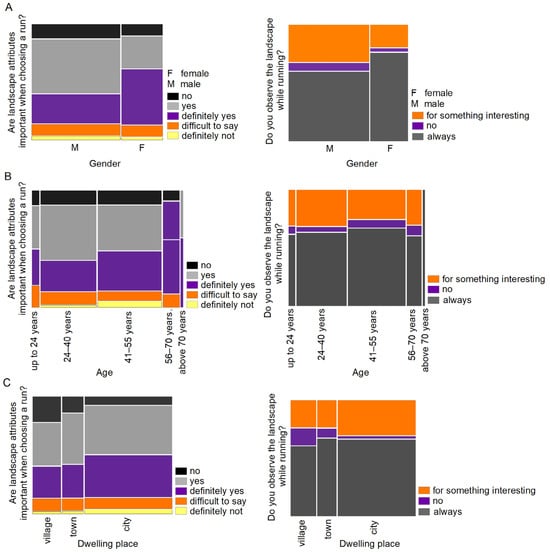

Run choice was guided by the landscape (76%) and as many as 66% of the respondents always pay attention to the landscape during the run (Figure 4). Women and men, when choosing the type of run, appreciate landscape values to a different extent (χ2 = 18.436; p = 0.001). For 50% of women, the most important criterion for choosing a route is an attractive landscape, and as many as 77% of them admire nature while running. It is different for men. Among them, the question of whether landscape values are important when choosing a run was answered yes for 49% respondents, and 61% of them always pay attention to the surroundings while running (Figure 4A).

Figure 4.

Running activity in the context of landscape values of routes in relation to gender (A), age (B) and place of residence (C).

Out of 302 respondents, 122 people confirmed that landscape values are important to them, regardless of the type of run. However, road running provides an opportunity to observe the landscape for only 19 people, and half of them also appreciate the landscape along the routes. A total of 144 runners declared that they admire the landscape during mountain runs, and 100 appreciate the surrounding nature during long-distance runs (marathons, ultra-runs).

The analysis of the graphs, as well as the results of the frequency analysis, indicate that the importance of the landscape criterion when choosing a run does not depend on the runner’s place of residence (χ2 = 13,579; p = 0.093) and age (χ2 = 17,797; p = 0.539). However, the results show a certain tendency—the older the runners, the more they appreciate the advantages of the routes they run on. About 37% of city dwellers choose running with an interesting landscape, but if they do, 67% of them always admire it while running. Significantly fewer rural residents, although still a lot (61%), are interested in the surrounding nature while running (χ2 = 17.295; p = 0.002) (Figure 4C).

3.4. Characteristics of the Most Attractive Landscape Competition Routes

The routes most often indicated as the most attractive in terms of landscape are located in south-eastern Poland and are almost entirely located in the Carpathians [35]. The most frequently mentioned were six particular routes, including four typically mountain ones (Rzeźnik Run BRz, Krynica 7 Valleys Run B7DK, Magurski Ultramarathon UM, Bieszczadzki Ultramarathon UB) and two located in the foothills (Podkarpacki Ultramarathon UP, Lubeński Cross PL). Mountain routes have been marked out in areas of exceptional natural value, 100% of which run through protected areas (Table 1). From 60% to over 80% of the length of these routes runs through forested areas. These routes are very difficult and physically demanding due to the length (70–100 km) and the great diversity of the terrain. The absolute altitudes of these routes range from 300 to over 1260 m above sea level. The routes cross numerous deep mountain valleys, which results in large differences and a total elevation gain exceeding even 6000 m.

Table 1.

Parameters of routes most often indicated in the survey as the most attractive in terms of landscape.

Foothill routes have a slightly different character. Although they are as long as mountain trails (approx. 70 km), the terrain denivelations are much smaller here. The total sum of elevation gains is lower—a maximum of over 2600 m. Both foothill and mountain routes are characterised by steep ascents. In almost all routes, maximum drops exceed slopes of 50°. However, the average drops in foothill routes are clearly lower (Table 1).

Land use along foothill routes is more diverse than along mountain routes. The foothill routes run to a greater extent through built-up areas (10–24% of the route length), while the remaining sections (forest, grassland and arable land) have comparable, similar shares.

Case Study: Podkarpackie Ultramarathon

The Podkarpackie Ultramarathon starts and ends in the centre of the provincial city, and its main part runs through an agro-forest mosaic. Two components that distinguish this trail are its high diversity and, at the same time, its balanced distribution of land cover, which are crucial features contributing to the overall attractiveness of the landscape [36] (Table 2).

Table 2.

Parameters of the Podkarpackie Ultramarathon route taking into account land use in relation to the relief.

The UP route is 71.1 km long (Figure 5) and runs through areas with varied relief, the height difference reaching 190.8 m. The “up” and “down” sections are evenly distributed. The route climbs 36.1 km, which is 51% of its length. In total, the participants climb heights of 2612.3 m up and 2612.4 m down (Table 2).

Figure 5.

Relief and land development along the route of Podkarpackie Ultramarathon: (A) Location. (B) Terrain model. (C) Three-dimensional land use model. (D) Longitudinal profile of the route, taking into account land development. Use of colours according to the legend Figure 2C. (E) Classification of the LiDAR point cloud along the route within the centre of Rzeszów. (F) Route exposure. (G) Visibility from the selected waypoint.

Land development along the route is also very diverse (Figure 5C). The longest sections lead through the following: forests, arable land, grassy vegetation and buildings. Each of these types covers over 20% of the length of the route, and in total, the above-mentioned usable lands account for over 99% of the route (Table 2). The “up” and “down” sections of the route in particular types of land use have similar lengths and total changes in height. These features make the route diverse in terms of landscape but, at the same time, balanced in terms of altitude (Figure 5D). The average slope of the route is 6.3°. The highest slopes are recorded in forest areas and the lowest in built-up areas (Table 2). The buildings have a varied character, from compact and historic buildings in the centre of a large city (Figure 5E) to low-rise rural buildings.

Due to the planning of the route in a closed loop, the exposure along the route is quite evenly distributed, although sections with a northern exposure slightly predominate (Figure 5F). Despite the numerous hills through which the route passes, one can admire the vast panorama of the region only in relatively short sections (Figure 5G). The highest hills are covered with forest, which limits visibility (Figure 5C,D).

4. Discussion

Existing research confirms that the high attractiveness of the landscape can encourage participation in sports and physical activity outdoors. However, these studies focus largely on activities in the city, especially individual, unorganised ones [6,7]. We prove that an attractive landscape is also an important aspect of running routes, which was emphasized by most of our respondents, especially women, which was also confirmed by Pomfret and Bramwell [37].

The dominant position of men in sports results from cultural determinants [38]. Physical activity is associated with traits traditionally considered “masculine”, such as physical strength, power, readiness for competition and confrontation [39]. However, research indicates that both genders show equally significant interest in participating in sports in the early years of schooling. Still, girls often do not receive adequate support to develop these interests [40]. The issue of the presence of women in individual running in an attractive landscape area of residence is described by Titze et al. [41]. They found that women who did not have the opportunity to run in an attractive landscape were more likely to give up regular running activity. Also, Bobiec et al. [42] draw attention to the special way of perceiving the landscape by women, focusing on the aesthetics, safety and quality of the accompanying infrastructure. The attractiveness of the landscape of running competitions may become an opportunity to activate running among women and promote physical activity among them. When setting new running routes, it is worth remembering, because, as it has been shown, women take up running competitions less often. As we have shown, when choosing runs, in addition to landscape values, practical considerations are also important, such as short distances from places of residence. Scientific research shows that the psychological aspect, such as family support, is also important [41], as well as a sense of freedom, e.g., an escape from the stereotype of a woman who only takes care of the home and family [43]. When choosing races, they take into account the route profile and length. More and more women decide to take part in difficult races, including ultramarathons and mountain runs, although men still dominate. However, it is worth noting that if they choose a difficult race, they are very committed, and the percentage of success in completing the race is high, sometimes higher than that in the group of men [44].

In our research, the aspect of an attractive landscape was particularly emphasised in mountain and route runs, which usually take place in areas of high natural value. The landscape is especially important in long-distance running. It has been proven that the ultimate goal is finishing an ultra-run, not the final position [45]. In addition, Watkins et al. [46] extended knowledge about the motivation of ultra-runners, pointing to aspects such as fun and care for competitors. Our experience allows us to supplement the knowledge about ultra-runners with another aspect, i.e., the importance of landscape values in choosing a running route.

Two mountain runs, considered by our respondents to be the most beautiful in terms of landscape, are considered the most difficult mountain runs in Poland, which are also very popular among runners. Participation in them is treated as a “running achievement of life”; therefore, the main motivator of their choice is the desire to complete them and test their own abilities. The landscape, while attractive, adds to the sporting challenge. The variability of the route is important, not for visual reasons, but because it determines the difficulty level of the competition. However, we were interested in the attractiveness of the routes, which may not be in the “TOP” ranking of mountain runs in Poland, and the participation in which is dedicated to people with a high degree of fitness. Rather, we wanted to check the attractiveness of more regional routes and consider what landscape features they have and whether they can determine their attractiveness.

A detailed analysis of the 70-kilometre-long Podkarpackie Ultramarathon route shows significant diversification both in terms of relief and land cover. The diversity of the landscape is considered one of the most important values and determines its uniqueness and high importance for tourism [47], including sports tourism [48], and especially walking and running activities [49]. The diversification of land cover results in the fact that the participants of this run alternately run on asphalt and natural surfaces. The presence of asphalt surfaces on the route can sometimes negatively affect its assessment, as long-distance runners prefer natural surfaces [50]. The even distribution of ascents and descents brings it closer to Anglo-Saxon-style runs (running on the route “up-down-up-down”), which are especially preferred by ultramarathon runners [45]. At the same time, the altitude balance of the route makes it accessible also to runners with less sports skills. There are few scenic openings on the route, which are an important aspect of landscape attractiveness [48]. Nearly one-third of the route runs through forested areas, providing protection from harsh weather conditions and allowing one to “immerse” in nature [10]. The specificity of the run is that its beginning and end take place in the very centre of the large provincial city of Rzeszów, which is surrounded by a network of small towns, often with charming small-town and rural buildings. It seems, therefore, that it is this diversity of the route that determines the fact that many people take part in this competition.

Our research shows the high popularity of road running among both women and men. The Cracovia Marathon is one of the most popular running events in Poland, with an international dimension. The motto of the event is “with history in the background”, and the participants of the marathon run next to numerous monuments of over-1000-year-old Krakow. The uniqueness of this run lies largely in the popularity and beauty of the city itself. The Warsaw Half Marathon is, in turn, the largest street run in Poland with a long history (it has been organised since 1979, initially under the name “March of Peace”). The route of the run leads through the most beautiful corners of Warsaw, the capital of the country. Interestingly, street runs organised in the centres of historic cities were usually not considered by our respondents from the point of view of the attractiveness of the landscape, although the routes also run in attractive natural places (e.g., parks, river valleys). This is consistent with existing research, according to which landscape is understood and associated with a nice, non-urbanised view (e.g., of mountains, a lake or a river) [51]. “Nice view” indicates the visual aspect of the landscape, which is largely taken into account when assessing the attractiveness of the landscape. As more than 80% of human sensory experience is focused on sight [52], scenic beauty and preference comprise an essential criterion in studies of landscape perception [53]. The scenic attractiveness of landscapes is expressed, e.g., in the diversity of landscapes, view openings and the contrast of successive scenery [54]. Marking out competition running routes should take these aspects into account.

Most of our respondents came from cities with limited opportunities for contact with the natural environment [55]. The phenomenon of a lack of access or a lack of involvement in nature in an increasingly urbanised world has been widely analysed by Richard Louv [56], who coined the popular term “nature deficit”, which is decreasing from generation to generation. There are also limited opportunities to observe the open landscape in the city, which is also important for human well-being [57]. For city dwellers, nature attracts with its peace, provides a break from the hustle and bustle and is often a form of escape from everyday life [58]. This is why city dwellers most often chose runs that offered them an interesting, open landscape. Less interest in running activities in areas with a low degree of industrialisation may indicate that residents of large cities are more aware of the benefits of running activities [59]. This is also confirmed by the fact that our oldest respondents (people over 70) came from cities, and their motivation was probably related to pro-health aspects. The low participation of residents of small towns in running activities may indicate the cultural and social conditions of these areas, which are an enclave of traditional small-town communities that form a local community [60]. These communities show a more closed attitude towards external initiatives and trends, which could include running competitions. In Poland, there is a decline in the physical activity of rural residents, although they have better spatial, tourist and natural conditions compared to city residents [58,59]. This may result, among other things, from the lack of appropriate outdoor infrastructure. For rural residents, large urban agglomerations can be an attraction, which is why they often choose mass urban runs. The important motivation to take part in runs includes psychological factors such as the desire to compete and the emotions experienced during the run [58], which was also confirmed by our research. Now, rural areas in Poland are subject to strong urbanisation processes; as a result, the village in the spatial and functional dimensions becomes similar to the city. Contemporary inhabitants of the countryside are more and more often not related to agricultural activities; they are often urban people who have settled in rural areas, bringing their big-city habits and activities with them [61]. This may justify a slightly greater participation of rural residents in running competitions than of residents of small towns.

Promoting physical activity is an important goal for international organisations dedicated to public health [62]. The universality and accessibility of running activities make them one of the key forms of physical activation. In the reality of the pandemic threat or the war, running is becoming a form of activity desired by more and more people [25]. This demand should be capitalised on, especially in rural areas with high natural landscapes and cultural values but often with less development. Running events in regions with high potential for ecosystem services are almost neutral to the environment and, therefore, consistent with the idea of sustainable development and sustainable tourism. An important task facing state, local government and city authorities is assistance in organising mass sports events. Such activities contribute to the regional development, strengthen its competitiveness and, thus, can significantly contribute to improving the economic, territorial and social cohesion of countries. In global, national and regional strategies and policies, such activities constitute directional development priorities [63,64,65,66]. Promoting health-promoting physical activity is included in the Sports Development Program developed by the Ministry of Sport and Tourism of the Republic of Poland [67]. It refers to the recommendations listed in a number of European documents [68,69,70], although the European Union itself does not have the competence to harmonise the laws of Member States in the implementation of sports policy. Political guidelines should be flexible and adapted to the specificity of local communities and the needs of organisers. Without effective cooperation with local authorities and access to aid funds, the development of long-distance running activities will be difficult in Polish conditions.

5. Conclusions

The presented results confirm the importance of the landscape values of running routes and emphasise the diversity of landscapes as a primary value that has a positive impact on the promotion of running activities. The high landscape values of running routes can contribute to the activation of the running community, especially those including women and city residents. The profile of the route, health-promoting aspects and running challenges (distance, elevation gain) are as important as the landscape values of running routes. Runs organised in mountain and foothill landscapes, characterised by a wide variety of landscapes, are particularly attractive for runners. These values are especially appreciated by city residents, for whom participation in such runs is an opportunity to eliminate the deficit of contact with the natural environment. Cross-country trails marked out in a diverse landscape may become an important element in shaping local tourism, especially in rural and environmentally valuable areas. The wide variety of landscapes on cross-country trails allows you to discover the beauty of regions that is often missing on popular tourist trails and stimulate local economies and communities. Striving for regionally balanced countries’ economies is consistent with the Sustainable Development Goals as is promoting sustainable and responsible tourism [64,71]. Such activities are also in line with the assumptions of green infrastructure (connecting urban, suburban and rural green spaces into one, extensive network), allowing the combination of various forms of slow mobility, among which running plays an important role [25]. An interesting result of our research was the observation that runners do not associate the city with the word “landscape”. The popularity of city races results more from the tourist attractiveness of the cities and the theme/idea of the race than from the landscape values of these routes.

It is known that attractively designed public spaces promote running activities. The currently known guidelines for designing running routes largely concern the principles of organising the start/finish area, the principles of measuring and marking the route, ensuring safety on the running route and ensuring the smooth course of the race [72]. The rules for designing running routes also include those that recommend marking routes in a “diverse landscape”, with valuable “landscape and historical elements” [73]. However, these are quite general guidelines. Our research clarifies the principles of landscape perception, proving that route planning should take into account the diversity of landscapes expressed in the diversified profiles of routes, the diversity of land cover and its types of use, even distribution of ascents on the running route, the presence of viewing spots and contrasting landscape scenery along routes. Future research should be expanded to include a detailed analysis of visual aspects, including the presence of landscape elements on running routes, such as landscape accents and frames. In future considerations, it is worth taking into account the time of year/day in which a run takes place and how it affects the visual perception of the landscape. Research focusing on visual aspects seems to be insufficient. It would be valuable to refer to the multi-sensory experience of the landscape, which generates stimuli that affect the hearing, smell and touch of runners.

Author Contributions

All authors contributed to the study conception and design. Material preparation, data collection and analysis were performed by A.G., I.K. and B.O. The first draft of the manuscript was written by A.G. and all authors commented on previous versions of the manuscript. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all the participants.

Data Availability Statement

The raw datasets generated during and/or analysed during the current study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Kondo, M.C.; Triguero-Mas, M.; Donaire-Gonzales, D.; Seto, E.; Valentin, A.; Hurst, G.; Carrasco-Turigas, G.; Masterson, D.; Ambros, A.; Ellis, N.; et al. Momentary mood response to natural outdoor environments in four European cities. Environ. Int. 2020, 134, 105237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Twohig-Bennett, C.; Jones, A. The health benefits of the great outdoors: A systematic review and meta-analysis of greenspace exposure and health outcomes. Environ. Res. 2018, 166, 628–637. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van den Berg, M.; van Poppel, M.; van Kamp, I.; Andusaityte, S.; Balseviciene, B.; Cirach, M.; Danileviciute, A.; Ellis, N.; Hurst, G.; Masterson, D.; et al. Visiting green space is associated with mental health and vitality: A cross-sectional study in four European cities. Health Place 2016, 38, 8–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Q.; Zhang, H.; Xu, H. Health tourism destinations as therapeutic landscapes: Understanding the health perceptions of senior seasonal migrants. Soc. Sci. Med. 2021, 279, 113951. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Milligan, C.; Chalfont, G.; Kaley, A.; Lobban, F. Wilderness as therapeutic landscape in later life: Towards an understanding of place-based mechanisms for wellbeing through nature-adventure activity. Soc. Sci. Med. 2021, 289, 114411. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Giles-Corti, B.; Broomhall, M.H.; Knuiman, M.; Collins, C.; Douglas, K.; Ng, K.; Lange, A.; Donovan, R.J. Increasing walking: How important is distance to. attractiveness. and size of public open space? Am. J. Prev. Med. 2005, 28, 169–176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ettema, D. Runnable cities: How does the running environment influence perceived attractiveness. restorativeness. and running frequency? Environ. Behav. 2015, 48, 21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beenackers, M.A.; Kamphuis, C.B.M.; Burdorf, A.; Mackenbach, J.P.; van Lenthe, F.J. Sports participation. perceived neighborhood safety. and individual cognitions: How do they interact? Int. J. Behav. Nutr. Phys. Act. 2011, 8, 76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kamphuis, C.B.M.; van Lenthe, F.J.; Giskes, K.; Huisman, M.; Brug, J.; Mackenbach, J.P. Socioeconomic status, environmental and individual factors, and sports participation. Med. Sci. Sports Exerc. 2008, 40, 71–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bamberg, J.; Hitchings, R.; Latham, A. Enriching green exercise research. Landsc. Urban Plan. 2018, 178, 270–285. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barton, J.; Pretty, J. What is the best dose of nature and green exercise for improving mental health—A multi-study analysis. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2010, 44, 3947–3955. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bowler, D.E.; Buyung-Ali, L.M.; Knight, T.M.; Pullin, A.S. A systematic review of evidence for the added benefits to health of exposure to natural environments. BMC Public Health 2010, 10, 456. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Martens, D.; Gutscher, H.; Bauer, N. Walking in “wild” and “tended” Urban forests: The impact on psychological well-being. J. Environ. Al Psychol. 2014, 31, 36–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gladwell, V.F.; Brown, D.K.; Wood, C.; Sandercock, G.R.; Barton, J.L. The great outdoors: How a green exercise environment can benefit all. Extrem. Physiol. Med. 2013, 2, 3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kahlmeier, S. World Health Organization. Promoting Sport and Enhancing Health In European Union Countries: A Policy Content Analysis to Support Action; World Health Organization: Copenhagen, Denmark, 2011; Available online: https://www.researchgate.net/publication/281726717_Promoting_sport_and_enhancing_health_in_European_Union_countries_a_policy_analysis_to_support_action (accessed on 6 December 2023).

- Christiansen, N.V.; Kahlmeier, S.; Racioppi, F. Sport promotion policies in the European Union: Results of a contents analysis. Scand. J. Med. Sci. Sports 2014, 24, 428–438. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eime, R.M.; Young, J.A.; Harvey, J.T.; Charity, M.J.; Payne, W.R. A systematic review of the psychological and social benefits of participation in sport for adults: Informing development of a conceptual model of health through sport. Int. J. Behav. Nutr. Phys. Act. 2013, 10, 98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Downward, P.; Hallmann, K.; Rasciute, S. Exploring the interrelationship between sport, health and social outcomes in the UK: Implications for health policy. Eur. J. Public Health 2017, 28, 99–104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shipway, R.; Holloway, I. Health and the running body: Notes from an ethnography. Int. Rev. Sociol. Sport 2016, 51, 78–96. Available online: https://eprints.bournemouth.ac.uk/22108/1/Running%20Health%20Brian%20entry.pdf (accessed on 14 January 2024). [CrossRef]

- Oja, P.; Titze, S.; Kokko, S.; Kujala, U.M.; Heinonen, A.; Kelly, P.; Koski, P.; Foster, C. Health benefits of different sport disciplines for adults: Systematic review of observational and intervention studies with meta-analysis. Br. J. Sports Med. 2015, 49, 434–440. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Recreational Running Consumer Research Study. 2021. Available online: https://assets.aws.worldathletics.org/document/60b741d388549ceda6759894.pdf?_gl=1*1opbbfh*_ga*MTg2MjUwNDU3NC4xNzAxODYwNDAy*_ga_7FE9YV46NW*MTcwMTg2MDQwMS4xLjEuMTcwMTg2MDQyMC4wLjAuMA (accessed on 6 December 2023).

- Bodin, M.; Hartig, T. Does the outdoor environment matter for psychological restoration gained through running? Psychol. Sport Exerc. 2003, 2, 141–153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hansmann, R.; Hug, S.M.; Seeland, K. Restoration and stress relief through physical activities in forests and parks. Urban For. Urban Green. 2007, 6, 213–225. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- European Union. Building a Green Infrastructure for Europe. 2013. Available online: https://ec.europa.eu/environment/nature/ecosystems/docs/green_infrastructure_broc.pdf (accessed on 1 February 2023).

- Ladu, M.; Battino, S.; Balletto, G.; Garcia, A.A. Green Infrastructure and Slow Tourism: A Methodological Approach for Mining Heritage Accessibility in the Sulcis-Iglesiente Bioregion (Sardinia, Italy). Sustainability 2023, 15, 4665. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Benedict, M.A.; McMahon, E.T. Green Infrastructure: Linking Landscapes and Communities; Island Press: Washington, DC, USA, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Waniowski, P.; Waniowski, T. Marketing aspects of organizing mass runs—Seeking new opportunities. In Health and Lifestyles. Determinants of Lifespan; Szalonka, K., Nowak, W., Eds.; e-Monografie; E-Publishing; Law and Economics Digital Library, Faculty of Law, Administration and Economics of the University of Wrocław: Wrocław, Poland, 2020; Volume 170, Available online: https://repozytorium.uni.wroc.pl/en/dlibra/publication/128151 (accessed on 6 December 2023). (In Polish) [CrossRef]

- Simasathiansophon, N. The motivation to run in a marathon. In Proceedings of the E3S Web Conferences, Topical Problems of Green Architecture, Civil and Environmental Engineering, Moscow, Russia, 19–22 November 2019; Volume 164, pp. 1–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Waśkowski, Z. Profile of a Polish Runner; Technical Report; Poznan University of Economics: Poznań, Poland, 2014; Available online: https://www.researchgate.net/publication/269221876_Profil_polskiego_biegacza (accessed on 6 December 2023). (In Polish)

- Scheerder, J.; Breedveld, K.; Borgers, J. Running across Europe. The Rise and Size of One of the Largest Sport Markets; Palgrave Macmillan: London, UK, 2015. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, B.J.; Tsunetsugu, Y.; Kasetani, T.; Kagawa, T.; Miyazaki, Y. The physiological effects of Shinrin-yoku (taking in the forest atmosphere or forest bathing): Evidence from field experiments in 24 forests across Japan. Environ. Health Prev. Med. 2010, 15, 18–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Akers, A.; Barton, J.; Cossey, R.; Gainsford, P.; Griffin, M.D.; Micklewright, D. Visual color perception in green exercise: Positive effects on mood and perceived exertion. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2012, 46, 8661–8666. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rogerson, M.; Barton, J. Effects of the visual exercise environments on cognitive directed attention, energy expenditure and perceived exertion. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2015, 12, 7321–7336. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Larsen, J.; Bærenholdt, J.O. Running together: The social capitals of a tourism running event. Ann. Tour. Res. 2019, 79, 102788. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Solon, J.; Borzyszkowski, J.; Bidłasik, M.; Richling, A.; Badora, K.; Balon, J.; Brzezińska-Wójcik, T.; Chabudziński, Ł.; Dobrowolski, R.; Grzegorczyk, I.; et al. Physico-geographical mesoregions of Poland—Verification and adjustment of boundaries on the basis of contemporary spatial data. Geogr. Pol. 2018, 91, 143–170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qian, J.; Xiang, W.; Liy, Y.; Meng, X. Incorporating landscape diversity into greenway alignment planning. Urban For. Urban Green. 2018, 35, 45–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pomfret, G.; Bramwell, B. The characteristics and motivational decisions of outdoor adventure tourists: A review and analysis. Curr. Issues Tour. 2016, 19, 1447–1478. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mowad, J. Gender Inequality in Sports, Fair Play. Rev. Filos. Ética Derecho Deporte 2019, 13, 28–53. [Google Scholar]

- Pringle, R. Masculinities, sport, and power: A critical comparison of Gramscian and Foucauldian inspired theoretical tools. J. Sport Soc. Issues 2005, 29, 256–278. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lopiano, D. Gender equity in sports. Divers. Factor 2004, 12, 24–29. [Google Scholar]

- Titze, S.; Stronegger, W.; Owen, N. Prospective study of individual. social. and environmental predictors of physical activity: Women’s leisure running. Psychol. Sport Exerc. 2005, 6, 363–376. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bobiec, A.; Paderewski, J.; Gajdek, A. Urbanisation and globalised environmental discourse do not help to protect the bio-cultural legacy of rural landscapes. Landsc. Urban Plan. 2021, 208, 104038. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Doran, A. Empowerment and women in adventure tourism: A negotiated journey. J. Sport Tour. 2016, 20, 57–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Apollo, M.; Mostowska, J.; Legut, A.; Maciuk, K.; Dallen, J.T. Gender differences in competitive adventure sports tourism. J. Outdoor Recreat. Tour. 2023, 42, 100604. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krouse, R.Z.; Ransdell, L.B.; Lucas, S.M.; Pritchard, M.E. Motivation goal orientation coaching and training habits of women ultrarunners. J. Strength Cond. Res. 2011, 25, 2835–2842. Available online: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/21946910/ (accessed on 14 January 2024). [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Watkins, L.; Wilson, M.; Buscombe, R. Examining the diversity of ultra-running motivations and experiences: A reversal theory perspective. Psychol. Sport Exerc. 2022, 63, 102271. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, H.; Yang, Z.; Han, F. Tourist landscape vulnerability assessment in mountainous world natural heritage sites: The case of Karajun-Kurdening. Xinjiang, China. Ecol. Indic. 2023, 148, 110038. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dzięgiel, A.; Tomanek, M. The profile of a participant mountain running events. Stud. I Monogr. AWF We Wrocławiu 2014, 120, 88–102. Available online: http://repozytorium.umk.pl/handle/item/2745 (accessed on 6 December 2023). (In Polish).

- Hitchings, R.; Latham, A. How ‘social’ is recreational running? Findings from a qualitative study in London and implications for public health promotion. Health Place 2017, 46, 337–343. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Howe, P.D.; Morris, C. An exploration of the co-production of performance running bodies and natures within “Running Taskscapes”. J. Sport Soc. Issues 2009, 33, 308–330. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kulczyk, S. Landscape and Tourism; About Mutual Relations; Uniwersytet Warszawski: Warszwa, Poland, 2013; Available online: https://wgsr.uw.edu.pl/wgsr/wp-content/uploads/2018/11/Krajobraz_i_turystyka_kulczyk.pdf (accessed on 6 December 2023). (In Polish)

- Porteous, J.D. Environmental Aesthetics: Ideas, Politics and Planning. Routledge: London, UK, 1996. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Palmer, J.F. Research agenda for landscape perception. In Trends in Landscape Modelling; Buchmann, E., Ervin, S., Eds.; Herbert Wichmann Verlag: Heidelberg, Germany, 2003; pp. 163–172. [Google Scholar]

- Kaplan, R.; Kaplan, S.; Ryan, R.L. With People in Mind; Island Press: Washington, DC, USA, 1998. [Google Scholar]

- Nikkhou, A.S.M.; Tezer, A. Nature-deficit disorder in modern cities. In Sustainable Development and Planning XI; WIT Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 2020; pp. 407–417. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Louv, R. Last Child in the Woods: Saving Our Children from Nature-Deficit Disorder; Algonquin Press: Chapel Hill, NC, USA, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Thompson, C.W. Linking landscape and health: The recurring theme. Landsc. Urban Plan. 2010, 99, 187–195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Malchrowicz-Mośko, E.; Poczta, J. Sports activity of the inhabitants of rural areas—Motives for participation in a mass race event on the example of the Poznań Half Marathon. J. Educ. Health Sport 2017, 7, 329–340. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sygit, K.M.; Sygit, M.; Wojtyła-Buciora, P.; Lubliniec, O.; Stelmach, W.; Krakowiak, J. Physical activity as an important element in organizing and managing the lifestyle of populations in urban and rural environments. Ann. Agric. Environ. Med. 2019, 26, 8–12. Available online: https://agro.icm.edu.pl/agro/element/bwmeta1.element.agro-bf7c7836-29fd-44fe-bf61-b2aead1494ec (accessed on 14 January 2024). [CrossRef]

- Górka, A. Small cities in big cities, big cities in small ones—Local or alienation in public space. Acta Univ. Lodz. Folia Geogr. Socio-Oeconomica 2015, 15, 293–304. Available online: https://dspace.uni.lodz.pl/xmlui/bitstream/handle/11089/4189/18-g%c3%b3rka.pdf?sequence=1&isAllowed=y (accessed on 6 December 2023). (In Polish).

- Wiklin, J. A Diverse and Changing Polish Countryside—Report Synthesis. In Polska Wieś 2020; Wilkin, J., Hałasiewicz, A., Eds.; Raport o Stanie Wsi: Warszawa, Poland, 2020. Available online: https://sir.cdr.gov.pl/wp-content/uploads/2020/06/Raport-o-stanie-wsi-Polska-Wies-2020.pdf (accessed on 6 December 2023). (In Polish)

- WHO Guidelines on Physical Activity and Sedentary Behaviour: At a Glance. Available online: https://www.who.int/europe/publications/i/item/9789240014886 (accessed on 6 December 2023).

- Strategy for Local Sustainable Tourism Development. Available online: https://www.atlantis-press.com/article/125963749.pdf (accessed on 6 December 2023).

- Biodiversity Strategy for 2030. Available online: https://environment.ec.europa.eu/strategy/biodiversity-strategy-2030_en (accessed on 6 December 2023).

- Strategy for Responsible Development. Available online: https://www.gov.pl/web/fundusze-regiony/informacje-o-strategii-na-rzecz-odpowiedzialnego-rozwoju (accessed on 6 December 2023). (In Polish)

- Development Strategy of the Podkarpackie Voivodeship. Available online: https://www.podkarpackie.pl/images/pliki/RR/2022/Strategia_rozwoju_wojew%C3%B3dztwa_-_Podkarpackie_2030_-_Sejmik_WP_28.09.2020_r.pdf (accessed on 6 December 2023). (In Polish).

- Program Rozwoju Sportu do 2020. Warszawa. 2019. Available online: https://www.gov.pl/web/sport/dokumenty-strategiczne (accessed on 30 December 2023). (In Polish)

- Commission of the European Communities. White Paper on Sport. Brussels. 2007. Available online: https://publications.parliament.uk/pa/cm200708/cmselect/cmcumeds/347/347.pdf (accessed on 6 December 2023).

- Council of the European Union. Council Conclusions of 18 November 2010 on the Role of Sport as a Source of and a Driver for Active Social Inclusion. 2010/C 326/04. Brussels. 2010. Available online: https://eur-lex.europa.eu/LexUriServ/LexUriServ.do?uri=OJ:C:2010:326:0005:0008:EN:PDF (accessed on 6 December 2023).

- Council of the European Union. Council Recommendation of 26 November 2013 on Promoting Health-Enhancing Physical Activity across Sectors. 2013/C 354/01. Brussels. 2013. Available online: https://eur-lex.europa.eu/LexUriServ/LexUriServ.do?uri=OJ:C:2013:354:0001:0005:EN:PDF (accessed on 6 December 2023).

- Sustainable Europe by 2030. Available online: https://commission.europa.eu/publications/sustainable-europe-2030 (accessed on 6 December 2023).

- Manual for Designing Cross-Country Routes. Available online: https://www.malopolska.pl/_userfiles/uploads/Podrecznik_projekotwania_tras_biegowych.pdf (accessed on 6 December 2023). (In Polish).

- IAAF Road Running Manual. Available online: https://media.aws.iaaf.org/competitioninfo/a6691e27-f891-4c84-8e95-7d2b5ddd77ee.pdf (accessed on 6 December 2023).

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).