Abstract

Green tourism is part of the global effort to create a more sustainable living environment, taking into account the needs of both the industry, the tourists and the local communities. CCIs are considered trustworthy ambassadors of authenticity and life values, and can therefore effectively promote and/or strengthen the ecological value. This paper focuses on the role that cultural and creative industries (CCIs) can play in the implementation of sustainable development, especially in regard to green tourism, focusing on their role as communicators of green messages. The methodological tools used for the collection, analysis and interpretation of data for this research include semiotic analysis in a number of CCIs’ products, coding their ecological messages; content analysis of the CCIs’ digital posts for a one-year period in order to examine the form, types and content of the communication; and a digital ethnography of the users’ comments in order to study the perception and interaction of the receivers of such messages, focusing on past, present and potential tourists. Through the case study of Greece—a well-known tourist destination with rich cultural resources—the author tries to answer to the following research questions: (a) Could green tourism be promoted as a life value through CCIs’ products and messages? (b) Are there any good and innovative practices for such promotion through the synergy of the tourism industry with CCIs that could be used as models for further cases? This paper concludes that CCIs can promote sustainability as a life value through role modeling, educational programs, and subconscious or more straightforward messages, using both their products and formal communication channels. The more successful way for Greek CCIs to promote green tourism is through synergies with official tourism promotion mechanisms. The research shows that in many cases, this linkage has been successful in a number of ways.

1. Introduction

Sustainability is an issue that has aroused many discussions among both researchers and stakeholders in areas such as tourism, culture and economic development. Climate change and environmental unbalances, as well as the constant overcrowd in touristic cultural areas, have underlined the urgent need for people to be more environmentally and culturally sensitive and make an effort to maintain resources—environmental, cultural or other—for future generations. If we focus on the environment and the need to take specific actions toward its protection, we will see that in the past years, in an attempt to make environmentally friendly choices widely known and adopted by the majority of—if not all of—the population, policy makers have voted for specific laws and created promotional material which was distributed to a variety of audiences. It is noted that widely promoted green strategies, such as minimizing food waste and plastic waste reduction initiatives, are embraced by many households, businesses and tourism accommodation properties in many countries worldwide.

In the tourism sector, the balance between welcoming foreigners and keeping the destinations’ natural and sociocultural resources intact is difficult to establish and maintain in destinations characterized by mass-scale tourism and mummification practices adopted by the tourism industry, which, for many decades, focused on the economic aspect of tourism development, overlooking the environmental and sociocultural impact of such a strategy. Sustainability in the tourism industry is considered hard to achieve [1], but destinations have started to realize that their potential green image can be used as a competitive advantage. In addition, after the COVID-19 pandemic and the Great Reset values, tourism’s concept of the “new normal” [2] highlights the need for future transformations in the tourism industry, including green practices.

Green tourism is part of the global effort to create a more sustainable living environment, taking into account the needs of both the industry, the tourists and the local communities. A number of studies have been published on sustainable and/or green tourism [3,4,5] discussing problems of “carrying capacity, control of tourism development, and the relevance of the term to mass or conventional tourism” [6]. Important EU initiatives, such as encouraging tourist accommodations to adopt green practices and supporting energy efficiency, have been adopted by the tourism sector and tourists alike. The mechanisms, however, through which sustainability can be promoted as a human priority have not been widely studied, although various studies have highlighted the importance of green marketing [7] for the realization of a green tourism industry, the increase in awareness through marketing [8] and the effective promotion of sustainable destinations and practices through identifying and targeting segments [9]. Apart from the media and tourism stakeholders, there are other communication mechanisms and/or opinion leaders that can shape the ground for the prioritization of green tourism following the above-mentioned practices.

This paper focuses on the role that cultural and creative industries (CCIs) can play in the implementation of sustainable development [10,11,12], especially in regard to green tourism. It highlights the issue of promoting green tourism through the synergy of the tourism industry with CCIs and uses the case study of Greece to examine this phenomenon. This paper’s goal is to identify good and innovative practices to promote green tourism as a life value through synergy with various CCIs. In order to understand the reason why CCIs are considered trustworthy communicators of such messages, it is first necessary to analyze the nature and history of CCIs and their communicative perspectives, as well as their synergies with the tourism industry and their effort to adopt sustainability principles in their own premises.

1.1. Cultural and Creative Industries: History and Terminology

Arts and culture are an essential part of people’s everyday lives, as they are related to important aesthetic human creations, almost all human interactions and practices on a daily basis, as well as meaning-making practices in specific spatiotemporal contexts. Parallel to scientific endeavors, art is believed to be a means of presenting the truth for mankind, the essence of humanity and the world beyond it. Stemming from tradition and aiming at innovation, culture is considered extremely significant in regard to personal choices and/or social collectivities, the formation of life values and everyday practices.

The term “cultural industry” was introduced in the book “The Dialectics of Enlightenment” by Theodor Adorno and Max Horkheimer, the main agents of the Frankfurt School, a group of researchers associated with the Institute of Social Research in Frankfurt, Germany. Influenced by Marxist theory, Adorno and Horkheimer talk about the alienation of the individual in the framework of commercialized economy, stemming from mechanized and standardized work. This automatized work routine is extended to one’s free time, encouraging the individual to find pleasure in the products of the culture industry. The Frankfurt School emphasized the organization of cultural goods’ production in a mass manufacturing scale but also expressed disapproval of the commercialization of culture. For them, culture was, at the time, “packaged” by the media and offered to masses of passive consumers, just like any other commercial product of the mass society.

During the decades of 1970 and 1980, the easier and wider access to a variety of cultural goods and services, the mediated cultural experience and the so-called democratization of culture created new theoretical discussions and scientific debates. The Birmingham School for Cultural Studies, founded by Richard Hoggart and Stuart Hall, questioned the notion of the mass and talked about groups of audiences formed on the basis of gender, age, interests, etc. The role of the receivers of the media messages became of outmost importance for the messages’ final perception, and therefore, the notion of the “culture industry” was fundamentally disputed.

The notion “cultural industries”—in plural—was introduced, implying an extension, so as to include, in addition to the mass media, all of the organizations engaged in the production, distribution and promotion of goods and/or services and all of the activities that manage symbolic goods—goods whose primary value stems from their cultural value [13]. It is unquestionable, at this time, that there are many better ways to produce and communicate culture in the framework of the culture industries, which was actually one of the reasons for the multiplication of the term. The term “cultural industries” highlights the various forms of cultural production in contemporary settings and the big number of the differentiated functions of the various cultural sectors, as well as the recognition of the role of cultural industries as means of economic growth at the local and/or national level, a fact that connects them with cultural policy [14]. Under the term cultural industries, we therefore include all of the cultural organizations, profit or non-profit, which present or host cultural goods and/or services: museums, galleries, film industry, performing arts organizations, publications, audiovisual media and all of the cultural activities that can be said to include “industrial ways” in the production and distribution of their goods and/or services. Cultural industries include all human activities associated with identity formation, artistic creation and human creativity, activities that in the distant past were considered personal achievements were transformed into collective tasks and later on into institutional actions. The final product passes through various stages of production many times, with the use of technology, and is finally standardized, distributed to vast audiences, acquires doubtful quality and value and almost always aims at the biggest possible audience and the biggest possible income [15].

The notion of the cultural industries, according to Hesmondhalgh [14], is connected to a wide grid of approaches on culture, known as the political economy of culture. The media continue to play a crucial role for cultural industries in recent times, as the importance of the promotion and the communication strategies used, along with the actual creative process, remains of great value and power for the cultural industries. The cultural policy of the 1980s (starting at an international level from UNESCO) confirmed the interconnection of culture and economy, using culture not only as a field of local growth but also as a developing field in employment, such as human resources, and identity formation at a national level. After the Tofflerian “cultural explosion” [16] of the 1990s, a period when cultural organizations over-doubled, infrastructure expanded and a vast number of festivals and cultural institutions were created worldwide, it became clear that cultural industries are dynamic fields of an area’s economic growth and, in many cases, of a destination’s tourism development.

The most contemporary term “creative industries” is even more expanded, so as to include all of the industries characterized by creativity as their raw material [17], where we notice “theoretical and practical convergence of the creative arts (individual talent) and the cultural industries (mass scale) in the framework of new media technologies and the new technology of knowledge for the new interactive people-consumers” [18]. Under the term “creative industries”, we can find the fashion, sports and video game industries, to name just a few. The categorization, however, is not stable, as the boundaries change in respect to the respective policy [19].

1.2. CCIs as Communication Vehicles

For many researchers, the use of both sectors in one phrase (cultural and creative industries) “represents a qualitative augmented industry and a more inclusive concept of economy” [20]. Being production mechanisms themselves, CCIs have adopted sustainable methods in the whole procedure of a good/service creation—from an idea conception to its actual realization. For this research, CCIs will be studied as vehicles through which messages and/or good practices on sustainability are communicated to cultural audiences. Being digitally oriented by their nature, especially after the COVID-19 adventure [21], CCIs connect to various audiences and have developed various channels for such communication: from the cultural goods and/or services themselves to promotional actions, and from audiovisual content for various media to digital and edutainment applications, including creative interactive social media posts and professionally designed web sites.

Apart from their creative and innovative character, CCIs have many major advantages as communication mechanisms. Firstly, they cover wide areas of culture and creativity—from highbrow art to popular cinema and from hand-crafted traditional items to video games—and can therefore promote their products and/or services to wide audiences, covering a large range of ages, interests and financial and sociocultural characteristics. This is a crucial point that affects both local residents—the permanent CCIs’ audiences—and tourists alike, as they all will be able to choose a cultural production or service that fits their taste in their home or visited land. The digital presence that most CCIs have chosen to have help the satisfied cultural viewer and/or listener follow and interact with their creative processes, either before, during or after his/her actual visit in their physical premises. This digital interaction creates special bonds between audiences and the CCIs that people choose to follow, forms communities [22,23] and enhances the role of CCIs as communicators of various messages. Through the above-mentioned relationship building [24], CCIs are considered trustworthy ambassadors of authenticity and life values, and can therefore effectively promote and/or strengthen the ecological value of green tourism.

1.3. Synergies of the CCIs with the Tourism Industry

The reasons for choosing to study CCIs as transmitters of messages on green tourism are many. First and foremost, the role of CCIs as both communicators and communication channels is evident throughout their history—the first and biggest cultural industry being the media—and it is a role that they have performed effectively at an international level. In addition, CCIs address their messages to big and extremely varied audiences, as they cover a wide range of interests. There are specific CCIs that can communicate—in an interactive and therefore successful way—with young audiences, such as the film and music industries, the fashion industry, the sports industry, the video game industry, the comics industry and many others. Editions, the media, museums and cultural organizations in general send messages to a wide variety of receivers in terms of age, social and financial status, gender, origins, etc. Most crucially, CCIs—carrying the value-shaping mechanisms of culture—are perceived as trustworthy communicators by a very big, international audience of diverse types. Lastly, CCIs are connected to tourism in various ways, and therefore, potential tourists are likely to search or even follow the digital accounts of the most known CCIs of their chosen destination and therefore receive their messages.

The synergies of CCIs with the tourism industry are seen in many cases. Culture as a word, as well as some of its famous visual representations, mostly monuments and landmarks—especially the ones included in Barthes’ “language of travel” [25]—have been widely seen on the tourism industry’s media, such as postcards, tourist leaflets and posters, destinations’ promotional videos, and national tourism organizations’ websites and social media posts. The increasing convergence of tourism and culture [26] has been widely discussed between tourism stakeholders and the scientific community. Cultural resources have been repeatedly used by many content producers outside of the tourism industry, as well, from schoolbooks to animation films, movies and TV shows, video games and individuals who wish to describe their travel experience or show it to friends and family through their own snapshots either in frames in their living rooms or through posts on their social media accounts [27]. This is easily recognized because widely recycled cultural imagery is seen as a seal of the authenticity of a place. These repeatedly seen cultural resources function as discriminating factors of a destination and its assets, transferring its “charisma” [28] and highlighting its uniqueness to all potential audiences.

“One must take endless precautions in Paris not to see the Eiffel Tower”, Barthes [25] says, as it is the most characteristic sign of Frenchness and therefore promoted in every corner of the city, in every souvenir shop, in every poster. Tourists that choose to visit Paris are prepared for this gaze [29]. They have seen the image of the Eiffel Tower in every schoolbook, in every media image whenever the context is of French nature. They have seen the words “Paris, France” near the Eiffel Tower in every tourist image, on postcards and leaflets, learning that the two are connected and inseparable [28].

Many tourists worldwide have followed the cultural tourism trend during recent decades, travelled to places rich in cultural resources, visited the famous monuments and waited in queues in order to photograph themselves in front of them—chest out, wide smile, in the same posture as everyone else in front of them. Regarding the case study of this paper, famous Greek archaeological sites such as the Acropolis or Knossos and Delphi, archaeological museums and/or any kind of ancient monument or object connected to the nation’s history are seen as signs of Greekness [30], are cherished and valued as authentic and/or charismatic and are therefore highly visible on tourist products. Such cultural monuments have established a special bond with the tourism industry and their messages are often addressed to tourists.

The recent need for creativity in tourism, the new creative tourism trend, offers visitors the opportunity to come to terms with cultural and creative industries and develop their creative potential through active participation in local traditional activities, courses or experiences [31]. Experience-based tourism is an emerging market of the tourism industry. Activities that give visitors the opportunity to participate include, for example, wine tasting, courses in traditional dances or fishing and cooking, etc. Such activities are important for our study, as through them, value is generated and innovation is encouraged. Furthermore, they are sustainable and mobile [32]. Their most important contribution to tourism development, however, is that they create the much-desired differentiation for a destination and connect visitors to local communities [33]. According to Booyens and Rogerson [34], the synergies between creative industries and tourism can help with tourism growth, and therefore, such synergies should be strengthened by developing creative networks and integrating creative tactics into the image of the destination. As the new generation of cultural tourism (UNESCO), creative tourism brings together cultural heritage, local traditions, the arts and creative industries in order to shape creative potentials for tourists. In this case, value stems from experiences and emotions [35], not tangible objects and visuality.

1.4. Green Tourism as a Life Value

Values are important elements of any sociocultural formation. They help people distinguish between right and wrong, good and just. They are connected to morality and are traditionally passed from generation to generation. In the era of technoculture, visual immersion and bodiless experiences, values can be passed on through mass and new media mediations. Life values are strongly connected to axiology, ethical theory and moral philosophy in ways that cannot be presented in the context of this paper. The author is mainly concerned with the classification of sustainability awareness and responsibility as something “good” and worthy of acquiring as a life motif and the role of CCIs in shaping such classification. The promotion of green tourism could be placed under the more general sustainability awareness umbrella, as people that identify sustainability as one of their core values will probably try to find sustainable practices in all of their activities, including traveling. Bergin-Seers and Mair [36] distinguish emerging green tourists by their environmental behavior at home.

1.5. Sustainability in CCIs

The reduction in the negative impact on the environment has been identified as one of the primary goals of almost every business and organization. CCIs have followed this guideline, as they play an important role in the global economy [37]. As a term, sustainability in CCIs refers to social and environmental principles, as well as financial and sustainability issues [12,20]. As stated in Kovaité et al. [20] and according to EY: Building a Better Working World (2021) and UNESCO (2007), CCIs can create a social inclusive ecosystem and can also integrate technological innovation and cultural diversity. CCIs have been seen as able to lead the way toward transformative sustainability if they work together with other economic sectors [38], while UNESCO (2021) has highlighted the importance of creativity in every sector of sustainability and suggested investment in creativity for environmental protection [39]. According to Papadaki et al. [40], “Examples of good sustainability practices in the CCIs include cultural staff and equipment traveling with mass transportation, fuel-efficient, electric or very few vehicles, use of renewable energy resources during a film production, apply reuse and recycle mechanisms in all the stages of cultural production, use LED lighting in performances, reduce the use of paper and/or implement sustainable design on set and minimize the use of plastic. In addition, many famous actors or singers stand by organizations that care for the environment or create their own ecological initiatives and these actions encourage the participation of people in relevant activities, as such professions, due to their publicity, can create role-models”.

The creative industries are a fast-growing economic sector capable of enhancing sustainability in many ways [26]. It is important to examine the role of CCIs—and their protagonists and therefore representatives—as ambassadors of innovation, creative ideas and societal change, as well as their ability to influence sustainable development [41] as primary drivers that strive to meet societal needs [21]. CCIs are widely seen as cross-innovation leaders, while their ability to promote sustainability has been studied in previous research projects [26], underlying their importance as sources of cultural and commercial value. Apart from their being role models for sustainable growth, CCIs can be seen as mediators of important messages concerning good practices in sustainability, as proposed above and will be shown in the next sections of the present paper.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Case Study

As a tourist destination, Greece is well known for its beaches and natural landscape, archaeological resources and rich traditions—including gastronomical habits, dances and festivities, as well as myths and historical narratives. Greekness is to a great extent shaped by and promoted through the media—both mass and new media—[42], while its touristic brand is enriched by Greek policy makers, the Greek National Tourist Organization (GNTO) and stakeholders in the tourism industry, both in the public and private sector. Greek cultural organizations have undoubtedly contributed to the shaping of the image of Greece, while they have cooperated in many ways with official media communication channels, the mass media and/or foreign and highly influential international CCIs, such as the film industry.

This paper follows ten big CCI brands in Greece—in terms of the numbers of visitors that they attract and their recognizable identity worldwide—and their ecological messages in order to study the ways in which they promote ecological value as a life value to tourism hosts and visitors alike. The CCIs that have been chosen to be included in this particular study include a small number (1 or 2) of a wide range of cultural organizations, as it was important to include in the data different types of cultural goods, productions and services, rather than more cultural bodies of the same sector. To be more specific, it was considered important to include such types of cultural resources that are considered as popular and/or characteristic of Greece: namely, archaeological sites and museums, contemporary cultural scenes, including organizations of performing arts and traditional orchestras, film and music festivals, as well as cultural landmarks and places that gather both locals and foreigners for a short walk around the premises or a photograph of the town’s view. According to the above-mentioned criteria, as well as their consistent and multilingual digital presence, the following CCIs were selected: the National Gallery of Greece, the Acropolis Museum, the National Archaeological Museum, the National Opera of Greece, the National Theatre, Onassis Stegi, Thessaloniki International Film Festival, Thessaloniki Concert Hall, the National Museum of Modern Art and a popular music singer, representing the music industry. (It is the same dataset as the one presented at the 2nd International Conference “Sustainability in Creative Industries”, including “mostly big cultural bodies—visual art and archaeological museums, performing arts organizations and venues, a film festival and a representative from the music industry—covering both Greek cultural heritage and recent creation in visual, performing and audiovisual arts, but not including smaller creative industries, like hand-crafted goods’ industries, as they did not fall under the criteria set by the researchers” [40]).

In addition, the cultural industries that are considered the strongest and most influential—from the time of the Frankfurt School’s writings until recent research [43,44]—, namely, the film and music industries, are studied in a separate sub-chapter through semiotic analysis of a number of their products and a digital ethnography of their audiences’ comments on specific digital platforms.

2.2. Methods and Data Collection

Following identifying the research goals, the author collected two sets of data: messages—communicated either through specific CCIs’ productions, like music and films, or through digital messages in social media—and a digital ethnography of receivers’ comments.

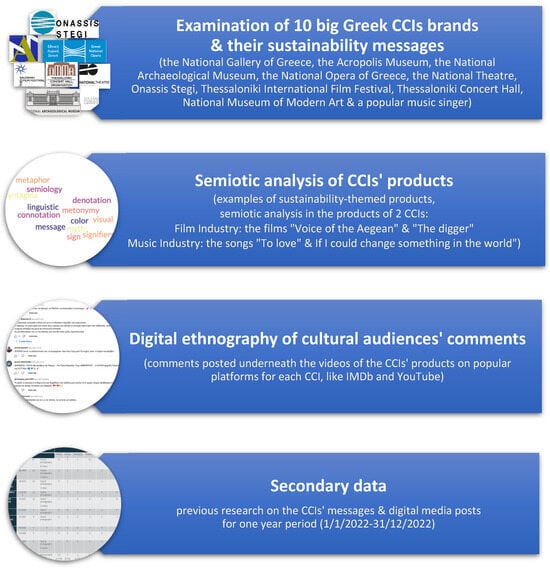

This study uses both qualitative and quantitative methodological tools in order to gather, analyze and interpret data regarding the role of some of the biggest Greek CCIs as trustworthy communicators of messages on sustainability and, specifically, green tourism. The methodological tools used in this research, as shown in Figure 1, include the examination of the big CCI brands in Greece (the 10 cultural organizations, as well as cultural and creative spaces that welcome the biggest number of tourists in Greece) regarding their green messages (e.g., on World Environment Day), semiotic analysis of a number of Greek CCIs’ products on sustainability and digital ethnography of the comments that were posted underneath the videos of the CCIs’ products in the digital environment and especially on popular platforms for each CCI, like IMDb and YouTube. In addition, secondary data from the author’s previous research on Greek CCIs’ messages and digital media posts for a one-year period (1 January 2022–31 December 2022) were added to the present research data.

Figure 1.

The methodological tools used in this research.

The research data gathered and analyzed for this study are useful in terms of the following:

- The examination of the number and type of messages distributed to the CCIs’ audiences, both through their own cultural production mechanisms and/or through their digital communication channels, as well as the messages’ content;

- the highlighting of the most influential and/or interactive CCI and/or message;

- the promotion and encouragement of good practices in promoting green tourism in Greece.

2.2.1. Content Analysis

Content analysis offers researchers the opportunity to study various kinds of content (mainly texts and/or images) in order to identify meaningful subjects (inductive reasoning) and look for existing subjects by testing specific hypotheses (deductive reasoning) [45]. The specific research followed a combination of the two (abductive coding), as the researcher tried to double test data. The preliminary codes selected were enriched by more codes after the examination of the first dataset. After defining the aim of the research and the research questions, the data sample and data collection methods were chosen, as well as the analysis methodology and the practical implications. The four stages that Bengtsson [45] describes, namely, decontextualization, recontextualization, categorization and compilation, are recognizable during the overall research process.

The steps followed for the specific content analysis were as follows: collection of data, becoming familiarized with the datasets, definition of codes for each content analysis (sustainability signification, sustainability issues and models for achieving sustainability), definition of meaning units for each code (environment, green, earth, save resources and future—for sustainability signification; energy, packaging and waste—for sustainability issues; and circular economy, protection and education—for models of achieving sustainability). The author then studied the occurrence of each meaning unit and code in each dataset in order to examine the CCIs’ role in promoting sustainability and green tourism in particular.

2.2.2. Semiotic Analysis

Semiotics or semiology is the science that studies signs. Signs are sociocultural conventions agreed between members of the same community in order to be able to communicate on a common ground. Language is the most common example of a sign system. The father of semiotics is considered to be the Swiss linguist Ferdinard de Saussure, while the American philosopher Charles Sanders Peirce also influenced the shaping of the new science to a great extent. For the purposes of this research, the analysis will follow the semiotic model of the French literary theorist Ronald Barthes, who was among the first semiologists to study images, apart from texts. He argues that each visual text carries three messages: a linguistic one, offered through the text, a literal one, formed through the denotation, and a symbolic one, stemming from the connotation. “Connotation, therefore, is formed beyond the literal meaning and is more subjective, as it includes feelings, memories and emotions, as well as sociocultural assumptions and personal experience of the message receiver” [46], while denotation refers to the obvious meaning of the sign. With the notion of anchorage, Barthes refers to the text, the element that, according to him, controls or guides apprehension. Other notions that will be used for the analysis of the CCIs’ products are myth, metaphor and metonymy. Myth is a narrative through which a certain culture interprets or understands some aspects of reality or nature. Metaphor is a way to express the uncommon through the common signs. Metonymy is one small part of reality that represents the whole. The reason for conducting semiotic analysis of the CCIs’ products is because the author wanted to find the hidden meanings behind the obvious signification schemata. Because of the small number of products under examination, semiotic analysis was both possible and, most importantly, valuable for highlighting the real meanings of the CCIs’ messages.

2.2.3. Digital Ethnography

Ethnography, in anthropology and social sciences, is the study of people on site, in their natural everyday life surroundings through observation and interviewing. Digital ethnography is the study of people in the digital environment. For this research, by digital ethnography, we mean the examination of the comments that were posted underneath the images and videos of the CCIs’ products in the digital environment and especially on important platforms for each CCI (YouTube and Spotify for music; IMDb and YouTube for films). The author also used, as secondary data, the digital ethnography of the comments written under the selected Greek CCI’s posts regarding sustainability on Facebook, presented in a previous study [40].

3. Results

3.1. The Big CCI Brands in Greece and Their Green Strategies

As will be shown in the following chapters, CCIs project various messages on ecology and green tourism, both through their linguistic and visual codes (in films and music lyrics or video clips for instance), and through their digital messages on social media. Green messages may be communicated on various dates throughout the year but are multiplied on specific occasions, such as World Environment Day. The selected CCIs have promoted good sustainability practices through their own example on their premises. All of the selected organizations try, for example, to minimize paper waste by offering services like electronic tickets and mobile applications, rather than printed catalogues. “Thessaloniki International Film Festival promotes green cinema in many ways, while its main venue has been energetically upgraded. Thessaloniki Concert Hall also uses energy saving technology” [40].

3.2. Green Messages on World Environment Day

World Environment Day is celebrated on the 5 June and is an opportunity for every business and organization to express and promote its ecological production strategy and/or values. As part of on-going research on the function of Greek CCIs as communication channels, this paper adds to the research presented at the 2nd International Conference on “Sustainability in Creative Industries” [40]. Regarding the CCIs’ messages on the 2023 World Environment Day, research has shown that they accounted for 10% of the total messages posted on the specific day. Other sustainability messages’ creators on that day included businesses (25%), local authorities (10%) and political parties (18%), volunteer groups (10%), tourism bodies (2%), specific themed groups (14%), educational institutions (9%), scientific communities (1%) and media groups (1%) [40]. The Greek CCIs that posted content on the 5 June 2023 included the Archaeological Museum of Thessaloniki, a record company, Athens Comics Library, a local cultural organization, a Greek popular singer, a television musical show and Thessaloniki International Film Festival (TIFF). The most interesting aspect of these posts, as stated in Papadaki et al. [40], is the fact that among all 2023 WED posts, they created the biggest interaction with the users. The most popular among them were the ones created by the film and music industries. More specifically, TIFF posted three highly engaging posts, while a well-known Greek singer, seen as a characteristic representative of the music industry, uploaded the most interactive post among all of the posts seen on that day. The polytropic message consisted of an image of the singer taking care of his garden and a text, where he shared some advice on everyday sustainability practices. The outcome was that “while the average number of likes, comments and shares of the posts with the hashtag #WorldEnvironmentDay were of one—or in some cases—two-digit numbers, the post of the Archaeological Museum of Thessaloniki gathered 267 likes, 3 comments and 19 shares, while the post made by the popular Greek singer gathered the impressive numbers of 10,000 likes, 847 comments and 142 shares. This fact stresses the dynamics of CCIs and especially the artists as communicators of messages” [40]—in this case sustainability messages.

3.3. CCIs’ Products and Their Ecological Messages

A number of CCI products and/or services include ecological messages into their main communication mechanism; the cultural work itself transfers such messages. The museums of this study have organized various exhibitions as vehicles encouraging ecological awareness or educational programs on environmental issues. According to Papadaki et al. [40], the National Museum of Contemporary Art of Greece has hosted, during 2022, “Arc: The structure of care” in Thessaloniki Biennale of Contemporary Art and “An action to wear my garbage” at its premises, while the Acropolis Museum has organized a number of educational programs on the subject. Performing arts organizations have organized relevant projects or performances, like “Art, science and technology for environmental challenges” and “Circular cultures: topographies of waste” by Onassis Stegi. “Thessaloniki Concert Hall hosts scientific and cultural events focused on sustainability issues, such as “How would climate change be like if it was music?”—a performance by EUYO, The European Union Youth Orchestra, and MOYSA, Megaro Youth Symphony Orchestra, followed by scientific talks by biologists and meteorologists, as well as music producers and performers” [40].

During 2023, Onassis Stegi encouraged the use of bicycles, produced performances on ecological themes, organized workshops on circular cultures and presented artworks on climate change. The National Gallery of Greece invited audiences to its gardens in order to talk about climate change. Thessaloniki International Film Festival organized the Climate Hub on subjects of environmental and social sustainability, screened films on environmental issues, broadcasted green podcasts, promoted recycling initiatives and sustainable gastronomical choices and introduced the “Green Fee”—a special fee that will be used both for the decrease in the organization’s environmental footprint and for green information messages and sustainability awareness-raising actions. The National Museum of Modern Art presented video installations and contemporary artworks on sustainability, such as The Weather Orchestra, artwork protests against the environmental catastrophe, such as “Surging Seas”, and organized projects like “Footprint” and “Return to Sender” on the issue of waste management of food and the fashion industry, respectively.

Among the big cultural industries, the two that will be studied in terms of their strategy to promote green messages through their direct reference or implicit coding are the film and music industries. The reason for this choice, apart from the numbers of their audiences and their value in financial terms, is their social impact. Both music and movies are believed to be influential shapers of identities, and collective and personal lifestyles, as well as inspirers of specific cultural communities and fandoms [47,48,49]. They were also the ones that communicated the most interactive sustainability messages on the 2023 World Environment Day, as shown in a previous section.

3.3.1. Movies Filmed in Greece

The film industry is the cultural industry that has communicated the most ecological messages to the biggest audience. Many recent movie scripts focus on the planet’s destruction, problematizing the viewers on the recent practices and/or including images of clean landscapes and/or the main natural elements that people recently decided to protect and clean: beaches, mountains and forests. Such Hollywood films include “Intersellar” (2014), “Virunga” (2014), “Beasts of the southern wild” (2012), “Children of men”, “The day after tomorrow” (2004), “Into the wild”, “Avatar”, “Wall-e” (2008) and “Erin Brockovich” (2000), as well as a number of documentaries. European films and documentaries, such as “Alcarràs (Spain, 2022), “Save the tree” (Spain, 2018), “I’m so sorry” (France, 2021), Demain (France, 2015) and “The velvet queen” (France, 2021) can be included in the list of the films with an ecological message. Regarding Greek film productions, the documentaries “Voice of the Aegean” (2004) and “Into the land of ice and fire” (2021) and the film “The digger” (2020) can be considered among the main Greek films with clear ecological messages.

The documentary “Voice of the Aegean” and the film “The digger” are Greek productions, filmed in Greece by Greek directors and with a Greek cast, while the documentary “Into the land of ice and fire” was directed by a Greek director but was filmed in the Norwegian arctic tundra and was inspired by the contemporary life of the indigenous people inhabiting the specific region, the Sámi. As the dataset for the specific research contains only Greek productions, the documentary “Into the land of ice and fire” was excluded. Our dataset, therefore, concerning Greek films with straightforward ecological messages consists of one documentary and one film, namely, the documentary “Voice of the Aegean” and the film “The digger”. Both film texts have been presented in festivals worldwide and have won many awards. “The digger” has been nominated for 24 awards and has won 21 awards, while “Voice of the Aegean” won the Best Film for the Nature Award in 2005 (European Heritage FF).

For a first decoding of the films’ messages, we conducted semiotic analysis of the trailers using an adaptation of Barthes’ semiotic model. The trailers were chosen to be studied as they are “both cultural goods and marketing texts… (that) include the most aesthetic visual codes of the film… (and) the main elements of the script that define the plot and are addressed to bigger audiences than the films themselves” [50]. The two visual texts are filmed in completely different settings, as the “Voice of the Aegean” focuses on the change in the Aegean sea and the landscape of the Aegean islands, while the plot of “The digger” unfolds around the appearance of an industrial unit that threatens to change the landscape of a mountainous small city where the protagonist lives. Despite the fact, however, that the documentary of our study is set in blue colors, while the film’s scenography is mainly set in a dark brown and green setting, the two films share a common background and, most importantly, promote similar messages on ecology and the need for sustainable choices. As shown in Table 1, both visual texts showcase the danger that nature faces due to human intervention. The encoding is unquestionably different in each case due to the directors’ choices and the different storylines, but also the type of visual text. In the case of the documentary “Voice of the Aegean”, the messages are more straightforward, as they are given through interviews with the locals and images of historic events and certain known facts. On the contrary, in a fictional text, such as a movie with a script, an aesthetically inspired production and the need to offer certain elements to the audience including suspense, the messages are more difficult to be decoded and might even be perceived differently by different viewers. According to Fish [51], certain “interpretive communities” have been formed in every sociality, sharing common origin, values, cultural habitus and/or knowledge on certain issues and are therefore able to perceive messages in similar or even identical ways, while Fiske [52] argues that every reader of a cultural text creates a different reading of the messages’ meanings.

Table 1.

Semiotic analysis of the films’ trailers using Barthes’ model.

This, along with our attempt to study the basic elements of the CCIs’ sustainability messages’ communication flow, guided us to the examination of the viewers’ comments, where it became evident that the vast majority of the viewers (88%) perceived the specific visual texts as metaphors for the ecological problem. In the case of the film “The digger”, there were many comments (37%) parallelizing the son’s attitude and his demand “for his share” of the father’s estate as a metonymy for the younger generations vivid claim for the natural future resources needed for their survival.

In addition to these two themed specific films, almost all of the films that were filmed in Greece entail many hints and promises for a clean Greek landscape. The iconography of these films includes images of the protagonists walking or swimming in clear blue waters and walking in green settings—be it mountains or forests—giving an ideal background for the plot of a well-protected, intact nature. These movies project a beautified image of a pure nature, embracing the film’s plot. According to Papadaki [50], all films filmed in Greece during the period between 1957 and 2014 included images of clear blue sea waters, while 92% showed natural landscapes and generally green scenery, including mountains and forests. Many contemporary films filmed in Greece follow the same path. “Maestro”, a Greek series broadcasted during 2022 on Netflix, is set in the Greek islands of Paxoi and contains many scenes colored by the blue and green scenery of the small Ionian islands.

More evidently, the 2022 film “The triangle of sadness” was filmed in the Greek island of Evia, and more specifically, Chiliadou beach, a few months after the catastrophic fires that destroyed a big part of the island. The film won the Best European Film Location Award 2022, an award organized by the European Film Commissions Network (EUFCN), which was awarded in a ceremony that took place in the context of the European Film Market in Berlin on 18 February 2023. The voters of the EUFCN Best Film Location Award had, in fact, the chance to win a trip to Greece and visit Chiliadou Beach. The social media posts and stories of the lucky voters were added to the numbers of other media posts and stories uploaded by formal cultural and tourist bodies, among which were the Greek Film Centre, the European Film Commissions Network and the Greek National Tourist Organization. These posts were addressed to two CCIs’ target audiences: film lovers and tourists, prompting both to visit the place and encouraging film-induced tourism in Greece [50].

The island of Evia also hosts the Evia Film Project, a green initiative from Thessaloniki International Film Festival, launched in 2022, to support the place after the 2021 wildfires. The Evia Film Project can also be added to the film-induced tourism initiatives in Evia—inviting a big number of domestic tourists for its various actions and performances. It is addressed to many types of audiences, of all ages, but with a basic common ground: an interest for the film industry, a desire to visit Evia and a concern for sustainability issues, as the whole project is based on broadcasting films and organizing actions in order to inform, educate and engage with visitors on sustainability perspectives. These two examples of the same place demonstrate the CCIs’ possibilities to take green initiatives, communicate sustainability messages and support places that have faced ecological disasters, while promoting, at the same time, the specific places as tourism destinations for potential visitors.

3.3.2. Song Lyrics

Many music bands have produced songs that talk about the environment and the need for its protection, like Radiohead, Neil Young—with the album “Greendale”—and Bob Dylan, with the well-known song “Licensed to kill”. The Greek music industry has followed the same path. Two of the most popular songs with lyrics signifying green practices are the songs “To love” by Nikos Veliotis (lyrics) and Pathelis Thalassinos (music) and “If I could change the world” by Depi Chatzikampani (lyrics) and Filippos Platsikas (music). The first song encourages listeners “to love mountains and seas, the familiar and unfamiliar landscapes, the birds, the flowers, the clouds, but the humans above all”. The main lyrics of the second song’s refrain are “if I could change the world, I would paint the sea blue again”. There is no direct reference to the meaning units or the wider codes that we have selected for our analysis, but only indirect implications of the need for sustainability. The first song refers to many elements of a healthy and unpolluted nature, such as mountains, seas, known and unknown places, birds, flowers, clouds, islands, rivers, stars and pigeons, encouraging the listeners “to love” these elements in an effort to transmit the message of employing sustainability practices and be protective toward nature. The second song’s lyrics are a man’s description of a woman’s walk through the years. She is imaginarily seen in Rome—when the city was burning—in Volga’s banks in Russia, in Colombo’s ship leaving Spain and heading for the unknown, in France on the 1 May and today, with a boy in her hands, near the crusaders (Table 2).

Table 2.

Semiotic analysis of the songs’ using Barthes’ model.

In the above-mentioned songs, we find an optimistic narrative (“To love”) and a pessimistic storyline (“If I could change the world”). The first song encourages love for all natural beings, while the second finds it hard “to change the world”, as no one listens and/or “is interested in a world boiling and burning”. The common signification is that we all need to change our lifestyles if we want “to change the world” and see the “sea blue again”.

As in the case of the film industry’s products, the music industry has also produced many songs that have travelled outside Greece—either in the mother language or in English—and are familiar to potential tourists. Again, they describe a clean Greek landscape, with blue seas and green mountains.

3.3.3. Digital Ethnography of the Audiences’ Comments

The films studied are not available through a digital platform. One can find information about the trailers and some scenes online. This is the reason why the comments recorded were few and mainly from an audience very well informed about and engaged in the film industry. The author recorded the comments on two platforms: IMDb and YouTube. “The digger” had 9 comments on IMDb and 43 on YouTube, while “Voice of the Aegean” had no comments on IMDb and 3 comments on YouTube, which, however, referred to the soundtrack, not the film. The songs of this study, being popular Greek songs, have many videos on many platforms. The author recorded the comments from the 10 first videos on YouTube. The song “To love” has 2,966,000 views between 2010 and 2023, while the song “If only I could change the world” has 6,759,000 views between 2009 and 2023. The comments underneath these 10 videos for each song were 526 for the first song and 1660 for the second. All of the comments were typed in excel files and given one number each, with the letter f in front if they referred to the films and the letter m when they referred to the music.

The comments varied from appraisal of the music/film and the musicians/cast to sociopolitical critique, comments on educational practices and personal memories while watching one of the specific films or listening to one of the specific songs. The sample of the comments for the songs include phrases like “very timely” (m12), “thank God the sea in my island maintains its fabulous blue colour”(m123), “wishing there were more songs passing these messages to my generation” (m202), “well-aimed” (m509), “we are responsible for this world”(m767), “unfortunately, we cannot change the world” (m909), “the best song for the environment and sustainability”(f1230), “the paradise is nature”(m1512), etc. The most common words found were ”environment” (found in 32% of the comments), “nature” (found in 57% of the comments), “future” (found in 28% of the comments), “school” (found in 78% of the comments) and “sustainability” (found in 19% of the comments). The sample of the comments for the films include phrases like “Greece contemporanity, its distorted modernity filmed with sensitivity and humor” (f5), “gorgeous landscapes” (f9), “it tackles interesting topics” (f14), “the director builds a confrontation with the progress as a destructive element” (f23), “the greatness of Greek landscape” (f27), “a multidimensional film with deep social and political messages” (f31), “raises critical political issues” (f33), “worth seeing and thinking about the issues raised” (f40), “some of the most important subjects of our times, such as climate change and deforestation” (f42), “environment, economical, ethical and social dilemmas”, “gifted people tighted strongly with their country land and nature” (f52), etc. The repeated words in this sample were the words “environment” (35%), “nature” (67%), “issues” (43%), “politics” (21%), “landscape” (23%), “countryside” (12%) and “climate change” (13%).

Three interesting points were drawn from this analysis. Firstly, the fact that 24% of the comments were written in a language other than Greek highlights that foreign people—maybe past or future tourists in Greece—watch the specific videos and interact with CCIs by writing comments. Second, the majority of the audience’s members understand the ecological “issue”, connect it with “politics” and express their concern on the “future”. Third, a very large number of people commented that the specific songs had been heard in Greek school celebrations, mainly at the end of the year, especially in early school years. This fact showcases the role of the specific cultural texts as educational media, transmitting important messages to young children and shaping ecological values.

Cultural audiences are characterized as highly engaged with sustainability, having many expectations from cultural organizations, as far as their green practices are concerned. The 2023 Green Act Report [53] stated that 87% of cultural audiences are worried about the climate crisis, while 93% have made changes to their lifestyles in order to act in a more sustainable manner. A total of 77% of cultural audiences think that cultural organizations have a big responsibility to change society and make changes in response to the climate change. Three in four cultural visitors want information from organizations about how they can act more sustainably, while 66% want more information about how to travel sustainably. These facts allow us to assume that cultural audiences are both eager to receive sustainability messages from CCIs, adopt sustainability practices in their everyday activities and connect culture to tourism.

3.4. Content Analysis on Social Media Posts (1 January 2022–31 December 2022)

As part of on-going research on the function of Greek CCIs as communication channels, this paper adds to the research presented at the 2nd International Conference on “Sustainability in Creative Industries” [40]. According to the analysis of the Greek CCIs’ posts on sustainability conducted in the above-mentioned research, Greek CCIs uploaded a significant number of messages on their official Facebook accounts during 2022. As seen in Table 3, the uploaded messages could be categorized under four types of content: good sustainability practices adopted by CCIs (e.g., energy upgrade or waste minimization), the CCIs’ own green-themed productions (performances, exhibitions, etc.), educational programs on ecological themes and social messages on the need to encourage everyday sustainability practices. According to the authors, “the CCIs can function as role-models, showcasing good sustainable practices they have adopted, they can send subconscious but powerful messages through art exhibitions and performances, can offer educational programmes, awakening the ecological consciousness to young generations and can promote a greening lifestyle both as an urgent need and as a life value” [40].

Table 3.

Analysis of the Greek CCIs’ green posts during 2022, Source: Papadaki et al. [40].

As cultural bodies usually encourage two-way communication flows with their audiences [54], not only in their premises but in the digital environment as well, [23], this study’s findings that 75% of the CCIs’ sustainability messages were interactive came as no surprise. Most comments written by the users underneath the posts shared positive feedback; in some cases, even overwhelming praise was noted. For example, comments like “Keep up the good work”, “Great initiative”, etc., were repeatedly found as responses to the CCIs’ sustainability messages. In fact, almost half of the comments studied (46%) expressed appraisal for the CCI’s actions. Other kinds of comments included “endorsement of the communicated message, critique of the message or the situation, asking for clarifications or posing a question and answer to a question posed either by the cultural body or one of the users” [40].

4. Discussion

4.1. Challenges and Barriers in Promoting Green Tourism through CCIs

The challenges and barriers faced in promoting green tourism are unquestionably many and variable. It is a rather difficult subject as a very newly appeared notion that people are not familiar with. This difficulty is faced both during the creation and the perception process of every sustainability message. The message creators—CCIs in our case—choose to make meaning related to ecological and sustainability issues mostly through their own productions, actions and/or specific initiatives and less through the creation of clear, transparent sustainability messages. At the same time, CCIs show great attention to forming educational programs and other initiatives for young children; the latter are seen as the future CCIs’ audiences and, at the same time, musketeers for all sustainability dimensions. Cultural audiences—including cultural tourists—however, also need information and guidance concerning the suggested sustainability practices that they could adopt in their everyday lives, as shown in the 2023 Green Act Report. A big number of these audiences expect cultural organizations to provide them with information on the subject. This kind of guidance could be given through the CCIs’ messages, as seen in the previous sections, in simple ways, beginning with awareness raising of sustainability among cultural audiences and potential cultural tourists. Repeated messages through beloved films and music works and educational programs, as well as role modeling practices and interactive digital messages could gradually build awareness for audiences following CCIs.

4.2. Benefits for Policymakers and Stakeholders: Examples and Good Practices

Policymakers and stakeholders in the tourism and cultural sectors could benefit from the synergy of CCIs with the tourism industry in many ways and gain various advantages, among which is audience development. The “Clean it like a Greek” initiative, organized by the non-profit environmental, educational and activity foundation “Aquahelp Foundation”, could be seen as such an example. The initiative aimed to clean the beaches, sea landscapes, mountains and forests in Greece, so the country could be promoted as the cleanest destination in Europe. One of the main partners of the action was the Greek National Tourism Organization with the participation of the Greek Minister of Tourism in many events. Among the ecological activities, many cultural activities were organized in each Greek periphery that hosted the initiative. The “Clean it like a Greek” initiative took place mostly in the Greek islands, as these are the places that attract the biggest number of tourists in the country. Such actions succeeded in promoting the Greek islands worldwide and, at the same time, inspired ecological practices and strengthened sustainability values for potential tourists and locals alike.

The same is the case with the organization of the “Evia Film Project” by Thessaloniki International Film Festival. It could engage locals and visitors in sustainability practices, subconsciously strengthening life values such as responsibility for the environment and future generations or even introducing such values to younger generations and people that had not conceptualized the ecological problem in its real dimensions. The use of cultural bodies and even smaller scale cultural activities for the education on and the strengthening of such life values is an important strategy that policymakers could adopt. The promotion of sustainability messages through cultural bodies is yet another good practice in the same direction, as the example of Chiliadou beach characteristically showcased in the previous sections. Official tourism bodies like the Ministry of Tourism and/or the Greek National Tourism Organization could act as mediators of these good practices toward a wider, international audience through their distribution channels and especially social media.

4.3. Limitations to This Study and Future Research Paths

At this point, certain limitations to this study should be mentioned. The time limits set for the specific research allowed for the recording of the CCIs’ messages for a one-year period, while it would be interesting to see the CCIs’ sustainability messages in a broader timeline, examine the CCIs’ consistency on sustainability awareness raising and even make some comparisons between specific periods of time. In addition, future research avenues could place the research in wider spatial contexts, including CCIs based in other countries, or examine the basic elements of the communication process in more detail and with a variety of methodological tools: conducting interviews with the communication experts in each CCI sector in order to understand the CCIs’ goals in designing and promoting sustainability messages; thoroughly studying the digital messages through, for instance, semiotic analysis; and defining any repeated patterns or studying the users/CCIs’ followers through audience research in order to see the way in which audiences respond, adopt or overlook the CCIs’ messages in their real-life practices. Furthermore, the links of the CCIs’ messages to the tourism industry could be studied in an attempt to highlight possible networks of further distribution of the messages to wider audiences and, most importantly, for the study of potential tourists. Other prospective research paths include the examination of the different types of CCIs regarding both their sustainability practices and/or messages in one destination and/or a variety of countries. Such research directions could inspire comparisons between different CCIs and perhaps define patterns in the messages of each industry.

5. Conclusions

This paper highlights the role of CCIs in communicating messages on sustainability and encouraging green tourism. Greece was selected as the case study for this study, as it is a country that welcomes many cultural tourists and is gazed at by many international foreign gazes both physically and digitally. Athens was awarded the prize of Europe’s leading cultural city destination for 2023 by the World Travel Awards which strongly proves the above argument. This research proved that CCIs can promote sustainability as a life value in various audiences and actually inspire two-way communication with them. The selected CCIs for the specific research are well known in the tourism industry, and their premises and cultural goods/productions and/or services are promoted through various tourist communication media, such as leaflets, postcards, websites of local authorities or local businesses and social media posts of both formal institutional bodies and/or tourists themselves. The connection of CCIs to tourism in a country like Greece is self-evident, as cultural resources are one of the biggest assets of the country as a tourist destination. As every potential tourist in Greece will most probably try to find information on the country’s cultural bodies before arriving at the destination, CCIs could offer information on green practices in the country—at least in the cultural sector—and attract tourists with an eye for sustainability.

For the purposes of the specific research, two databases were created: one consists of selected CCIs’ messages—mostly digital posts uploaded on their official Facebook accounts—and the other consists of the comments of the CCIs’ audiences under certain selected products’ digital distribution platforms and/or their Facebook posts.

This study showed that there are some good practices among both the themed events, the productions and the Facebook messages, but they are rather few. Even on World Environment Day, the messages posted were few, although among them, this study highlighted some very successful ones in terms of the innovation and interactivity patterns used.

The success of the CCIs’ messages is measured in this study by the analysis of the audiences’ comments. The fact that 88% of the audience members recognize the metaphors for the ecological problem in the CCIs’ productions—namely, the films and music works studied in this paper—proves that the myths and secondary meanings of the messages, uncovered through the semiotic analysis, are perceived. This fact is justifiable, as cultural audiences—including cultural tourists—are believed to be highly concerned with the impact of climate change [53] and are therefore more likely to understand such messages and more willing to apply changes in their everyday practices in order to help achieve a more sustainable future. Further research is needed, however, in order to examine the extent to which cultural audiences actually apply sustainability practices, rather than just commenting on such practices on social media, and whether they adopt green patterns in their tourist traveling, as well.

The initial coding of the research data included codes such as sustainability signification, sustainability issues and models for achieving sustainability, as chosen in previous research [40]. The meaning units of the initial coding were enriched, however, after the analysis of the digital ethnography of the audiences’ comments, so as to include the most common words used by the commentators. There were certain words used in all of our datasets that could function as the meeting points of the CCIs’ content producers and their audiences. Environment, nature and education were the three words most repeated in all of the messages and comments studied.

Most importantly, as this study highlighted, one of the most successful practices to promote sustainability concerns and/or practices and green tourism at the same time is the synergy of CCIs with official tourism promotion mechanisms, like the Greek National Tourism Organization and the film industry, in the case of Chiliadou beach and the Evia Film Project. All in all, if, through role modeling, educational programs and subconscious or more straightforward messages, CCIs manage to promote sustainability practices in everyday routine as a life value, it is most likely that cultural audiences will apply these practices in all aspects of their activities, including traveling.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

The data presented in this study are available on request from the corresponding author.

Conflicts of Interest

The author declares no conflicts of interest.

References

- Séraphin, H.; Nolan, E. Introduction. In Green Events and Green Tourism: An International Guide to Good Practice; Routledge: New York, NY, USA, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Glebova, E.; Perić, M. Tourism great reset: The inclusive, sustainable, and innovative reality. In Routledge Handbook of Trends and Issues in Tourism Sustainability, Planning and Development, Management, and Technology; Morrison, A.M., Buhalis, D., Eds.; Routledge: Abingdon, UK, 2023; pp. 33–43. [Google Scholar]

- Furqan, A.; Ahmad, P.; Mat, S.; Rosazman, H. Promoting green tourism for future sustainability. Theor. Empir. Res. Urban Manag. 2010, 8, 64–74. [Google Scholar]

- Gomes, S.; João, M.L. Insights for pro-sustainable tourist behavior: The role of sustainable destination information and pro-sustainable tourist habits. Sustainability 2023, 15, 8856. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Glyptou, K.; Kalogeras, N.; Skuras, D.; Spilanis, I. Clustering sustainable destinations: Empirical evidence from selected Mediterranean countries. Sustainability 2022, 14, 5507. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Butler, R.W. Sustainable tourism: A state-of-the-art review. Tour. Geogr. 1999, 1, 7–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gavrilović, Z.; Maksimović, M. Green innovations in the tourism sector. Strateg. Manag. 2018, 23, 36–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gheorghe, G.; Tudorache, P.; Rosca, I.M. The contribution of green marketing in the development of a sustainable destination through advanced clustering methods. Sustainability 2023, 15, 13691. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hecks, E. Direct Marketing: The Benefits of Personalization and Targeting—Designerly. Available online: https://designerly.com/benefits-of-direct-marketing/ (accessed on 22 December 2023).

- Hall, P. Creative cities and economic development. Urban Stud. 2000, 37, 639–649. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pratt, A.C. Urban regeneration: From the arts “Feel good” factor to the cultural economy: A case study of Hoxton. Urban Stud. 2009, 46, 1041–1061. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Imperiale, F.; Fasiello, R.; Adamo, S. Sustainability determinants of cultural and creative industries in peripheral areas. J. Risk Financ. Manag. 2021, 14, 438. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- O’ Connor, J. The definition of the “cultural industries”. Eur. J. Arts Educ. 2000, 2, 15–27. [Google Scholar]

- Hesmondhalgh, D. The Cultural Industries; Sage: London, UK, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Badimaroudis, F. Cultural Communication; Kritiki: Athens, Greece, 2011. (In Greek) [Google Scholar]

- Toffler, A. The Culture Consumers: A Study of Art and Affluence in America; Random House: New York, NY, USA, 1973. [Google Scholar]

- Cunningham, S. From cultural to creative industries: Theory, industry and policy implications. Media Int. Aust. 2002, 102, 54–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hartley, J. Innovation in governance and public service: Past and present. Public Money Manag. 2005, 25, 27–34. [Google Scholar]

- Hesmondhalgh, D.; Pratt, A.C. Cultural industries and cultural policy. Int. J. Cult. Policy 2005, 11, 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kovaite, K.; Šūmakaris, P.; Korsakiene, R. Sustainability in creative and cultural industries: A bibliometric analysis. Creat. Stud. 2022, 15, 278–298. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Klein, M.; Gerlitz, L.; Spychalska-Wojtkiewicz, M. Cultural and creative industries as boost for innovation and sustainable development of companies in cross innovation process. Procedia Comput. Sci. 2021, 192, 4218–4226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jenkins, H. Textual Poachers. Television Fans and Participatory Culture; Routledge: London, UK, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Hill, L.; O’ Sullivan, C.; O’ Sullivan, T.; Whitehead, B. Creative Arts Marketing; Routledge: London, UK; New York, NY, USA, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Bernstein, J.S. Arts Marketing Insights: The Dynamics of Building and Retaining Performing Arts Audiences; John Wiley & Sons: London, UK, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Barthes, R. The Empire of Signs; Hill and Wang: New York, NY, USA, 1982. [Google Scholar]

- Al-Shimari, K.K.J.; Hamzh, H.K.; Alktrani, S.H. Tourism, creative industries and exports sustainability: An international comparative study. Afr. J. Hosp. Tour. Leis. 2019, 8. Available online: https://www.researchgate.net/publication/337758968_Tourism_creative_industries_and_exports_sustainability_An_international_comparative_study (accessed on 29 November 2023).

- Dinhopl, A.; Gretzel, U. Selfie-taking as touristic looking. Ann. Tour. Res. 2016, 57, 126–139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Papadaki, E. Mass-produced images of archaeological sites: The case study of Knossos on postcards. Visual Resources. Int. J. Doc. 2004, 4, 365–382. [Google Scholar]

- Urry, J.; Larsen, J. The Tourist Gaze; Sage: London, UK, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Barthes, R. Mythologies; Vintage: London, UK, 1993. [Google Scholar]

- Ritchards, G.; Raymond, C. Creative tourism. ATLAS News 2000, 23, 16–20. [Google Scholar]

- Ritchards, G. Cultural Attractions and European Tourism; Boekman Foundation: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Smith, M. Tourism, culture and regeneration: Differentiation through creativity. In Tourism, Creativity and Development; Swarbrooke, J., Smith, M., Onderwater, L., Eds.; ATLAS Reflections; Association for Tourism and Leisure Education: Arnheim, The Netherlands, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Booyens, I.; Rogerson, C.M. Creative tourism in Cape Town: An innovation perspective. Urban Forum 2015, 26, 405–424. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prahalad, C.K.; Ramaswamy, V. Co-creation experiences: The next practice in value creation. J. Interact. Mark. 2004, 18, 5–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bergin-Seers, S.; Mair, J. Emerging green tourists in Australia: Their behaviors and attitudes. Tour. Hosp. Res. 2009, 9, 109–119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deloitte. The Future of the Creative Economy. Available online: https://www2.deloitte.com/content/dam/Deloitte/uk/Documents/technology-media-telecommunications/deloitte-uk-future-creative-economy-report-final.pdf (accessed on 20 November 2023).

- Harper, G. Sustainable development and the creative economy. Creat. Ind. J. 2021, 14, 107–108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gustafsson, C.; Lazzaro, E. The innovative response of cultural and creative industries to major European societal challenges: Toward a knowledge and competence base. Sustainability 2021, 13, 13267. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Papadaki, E.; Kourgiantakis, M.; Apostolakis, A. Sustainability messages from cultural and creative industries. In Proceedings of the Sustainability in Creative Industries Conference (ASTI), Virtual, 7–8 November 2023. in press. [Google Scholar]

- Marcolin, V.; Marshall, M.; Pascual, J.; Mihailovi, S.Q. Culture and the United Nations Sustainable Development Goals: Challenges and Opportunities. Brainstorming Report. Voices of Culture: Structured Dialogue between the European Commission and the Cultural Sector, Brussels. 2021. Available online: https://voicesofculture.eu/wp-content/uploads/2021/02/VoC-Brainstorming-Report-Culture-and-SDGs.pdf (accessed on 20 November 2023).

- Kavoura, A. A conceptual communication model for nation branding in the Greek framework. Implications for strategic advertising policy. Procedia-Soc. Behav. Sci. 2014, 148, 32–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cook, D. The Culture Industry Revisited; Rowman & Littlefield Publishers: London, UK, 1996. [Google Scholar]

- Baltzis, A. History and Economy of the Music Industry. The SAGE International Encyclopedia of Mass Media and Society; Merskin, D.L., Ed.; SAGE: London, UK, 2020; pp. 1144–1150. [Google Scholar]

- Bengtsson, M. How to plan and perform a qualitative study using content analysis. NursingPlus Open 2016, 2, 8–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Papadaki, E. Branding commodity, tourist & cultural products: Some thoughts on applying semiotic analysis for the marketing strategy in each product category. In Proceedings of the International Conference on Business and Economics—Hellenic Open University, Athens, Greece, September 2021; Available online: https://eproceedings.epublishing.ekt.gr/index.php/ICBE-HOU/article/view/5318/5199 (accessed on 29 November 2023).

- Duffet, M. (Ed.) Popular Music Fandom. Identities, Roles and Practices; Routledge: London, UK, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Santhosh, M. A study on fandom for movies and series. IRE J. 2019, 3. Available online: https://www.irejournals.com/formatedpaper/1701729.pdf (accessed on 29 November 2023).

- Jenkins, H. Fans, Bloggers and Gamers: Exploring Participatory Culture; New York University Press: New York, NY, USA, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Papadaki, E. Tourism industry’s synergies with cultural and creative industries as marketing tools: The case study of film-induced tourism in Greece. In Proceedings of the International Conference on Strategic Innovative Marketing and Tourism (ASTI), Zakynthos, Greece, 22–26 September 2023. in press. [Google Scholar]

- Fish, S. Is There a Text in This Class? The Authority of Interpretive Communities; Harvard University Press: Cambridge, UK, 1980. [Google Scholar]

- Fiske, J. Introduction to Communication Studies; Routledge: London, UK; New York, NY, USA, 1989. [Google Scholar]

- Act Green 2023 Benchmark Report. Indigo-Ltd. 2023. Available online: https://s3-eu-west-1.amazonaws.com/supercool-indigo/Act-Green-2023-Benchmark-report-c-Indigo-Ltd.pdf (accessed on 20 November 2023).

- Hooper-Greenhill, E. Museum, Media, Message; Routledge: London, UK, 2014. [Google Scholar]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).