1. Introduction

1.1. Aim of the Study

Many countries have established marine protected areas to preserve marine ecosystems and fisheries. A “protected area” refers to a particular site that requires the preservation of the environment. In natural resource management, the purpose of reserves is to protect biodiversity and the various values that derive from it by constraining space utilization. “Protected areas” can be understood as a policy approach to conserve biodiversity in a given space by initially identifying threats and subsequently implementing legal and institutional measures to effectively manage or control them [

1]. South Korea has established 15 marine protected areas to conserve unique marine ecosystems [

2], for which conservation funds are provided under South Korean law [

3]. On 24 December 2014, the Ministry of Oceans and Fisheries (MOF) designated waters around Ulleungdo island, near Dokdo, to preserve habitats and spawning areas for protected marine organisms and to conserve the submarine landscape [

4].

This study advocates similarly conserving Dokdo’s marine ecosystem by establishing the waters surrounding Ulleungdo and Dokdo as marine protected areas. It establishes the ecological case for the protection of these areas and considers the following research questions: can South Korea establish marine protected areas in overlapping sea areas? Do territorial sovereignty disputes and the absence of maritime boundary delimitation affect such establishment? If yes, what are the legal grounds? Should South Korea cooperate with Japan to establish marine protected areas in Dokdo?

Dokdo, an indigenous land of South Korea, is effectively administered by South Korea. Under these circumstances, territorial sovereignty claims over Dokdo have aggravated diplomatic and cooperative relations between Japan and South Korea. In response, South Korean researchers have investigated the territorial sovereignty over Dokdo. However, none has proposed measures that enable South Korea, a coastal state, to exercise its sovereignty and exclusive jurisdiction over Dokdo by establishing marine protected areas to protect Dokdo’s marine ecosystem. This study is distinguished from existing studies in that it proposes measures that enable South Korea, a coastal state, to establish Dokdo’s marine protected area with a focus on protecting Dokdo’s marine ecosystem, beyond maritime boundary disputes. Bridging this gap, this study verifies the legitimacy and appropriateness of such establishments as marine protection measures for conserving Dokdo’s marine ecosystem, which benefits South Korea and Japan. The study examines Korean and international laws as grounds for the necessity of establishing marine protected areas and the legal validity of such establishment to protect Dokdo’s marine ecosystem and increase the island’s social, cultural, and educational perspectives and marine tourism value. It facilitates socio-political discussions on the establishment of Dokdo and its surrounding waters as marine protected areas.

1.2. Research Methodology

This study emphasizes the need to conserve Dokdo’s marine ecosystem by establishing the surrounding waters of Ulleungdo and Dokdo as marine protected areas.

This research employs both empirical and doctrinal methodologies. Firstly, the authors assess the importance of conserving Dokdo’s marine ecosystem by conducting a thorough literature review and evaluating The National Marine Ecosystem Monitoring Program’s 2020 findings. The study provides a comprehensive overview of the current state of Dokdo’s marine ecosystem and its biodiversity.

Subsequently, a doctrinal study is conducted to scrutinize the legality, appropriateness, and validity associated with establishing a marine protected area for Dokdo under international law and by considering international precedents. In the context of this study, “doctrinal research” entails the synthesis of rules, principles, guidelines, and values to clarify and justify the legal aspects within the broader framework of legal systems.

Burksiene, V. and Dvorak, J. argued that “the success of performance management in protected areas depends on the network flattening and real involvement of locals and indigenous people in public governance” [

5]. In order to achieve the goal for the establishment of Dokdo’s marine protected area, this study underscores the necessity of a practical cooperation regime at the regional level to facilitate the effective implementation.

Thus, the study aims to verify the legitimacy and appropriateness of such establishment of marine protected areas as marine protection measures for conserving Dokdo’s marine ecosystem and providing both South Korea and Japan with benefits.

2. Marine Protected Areas in South Korea

2.1. Concept of Marine Protected Area

In natural resource management, protected areas, with restricted access, are used to preserve biodiversity and create various types of value [

1]. The designation of a protected area restricts hunting or the collection of organisms living or growing in the area [

1].

The first World Conference on National Parks in 1962 provided an international forum to discuss the use of marine protected areas for region-based management [

6]. Subsequently, the Ramsar Convention, the first international treaty for the conservation of wetland resources, was concluded in 1971, and the Regional Seas Program of the United Nations Environment Program was established in 1972; these measures have served as a basis for further measures [

7].

In 1988, the International Union for the Conservation of Nature and Natural Resources (IUCN) defined a marine protected area as a clearly defined geographical space that is recognized, dedicated, and managed via legal or other valid means for the long-term conservation of nature with associated ecosystem services and cultural values [

8]. In the Convention on Biological Diversity, a protected area is described as a geographically defined area designated to achieve conservation objectives [

9]. In South Korea, “marine protected areas” are areas designated as conservation worthy for their diverse marine organisms and assets, including marine landscapes [

10].

A marine protected area is a zone preserved by laws or other effective measures to keep a certain part of the ocean from harm. Marine protected areas include those for marine preservation, fisheries resource protection, valuable heritage conservation, and provision of opportunities for tourism, leisure, and educational activities. These types vary per designation purpose and each country’s degree of regulation for protection. Indeed, marine protected areas are established for various purposes, including the protection of the marine environment, marine ecosystems, fisheries resources, marine cultural heritage and conservation of wetlands, marine tourism, and education [

10].

Roberts and Hawkins [

11] note that biodiversity and productivity in the sea can be significantly recovered if networks of marine protected areas ensure ecological consistency and if 30% of each marine habitat is protected. The expansion of marine protected areas can reduce poverty, strengthen food security, create jobs, and protect coastal villages. In 2014, the IUCN World Parks Congress presented its goal to achieve at least 30% of marine protected area coverage worldwide [

12]. Since the Royal National Park in Australia was established as the world’s first marine protected area in 1879, 248 countries have designated marine protected areas as of 2023 [

13]. They manage 17,742 marine protected areas that cover 29,452,490 km

2. This gross area accounts for 8.13% of the oceans worldwide [

13]. For spatial range, marine protected areas comprise areas under the jurisdiction of coastal states and areas beyond national jurisdiction (61% of the oceans). Only 1.18% of the areas are marine protected areas [

13].

2.2. Legal Basis for Marine Protected Areas

The United Nations Convention on the Law of the Sea (UNCLOS) provides legal bases for applying region-based management measures, such as the establishment of marine protected areas, to conserve the marine environment despite the absence of specified regulations. Coastal states can establish marine protected areas in waters in their jurisdiction and regulate marine activities in such areas per the responsibility to protect and preserve the marine environment stated by Article 192 of the UNCLOS [

14]. Paragraph 5 of Article 194 of the UNCLOS indicates that coastal states must take necessary measures “to protect and preserve rare or fragile ecosystems as well as the habitat of depleted, threatened, or endangered species and other forms of marine life” [

14]. Thus, establishing marine protected areas is a measure coastal states can adopt to safeguard their marine environment. Paragraph 1 of Article 2 of the UNCLOS affirms that coastal state sovereignty extends to territorial seas [

15]. Coastal states can exercise their complete and exclusive jurisdiction (e.g., prescriptive and enforcement jurisdiction) over territorial seas, thus establishing marine protected areas to protect the marine ecosystem of territorial seas.

South Korean laws that provide grounds for establishing marine protected areas include the Conservation and Management of Marine Ecosystems Act, which presents regulations on protected areas for marine organisms, ecosystems, and landscapes. The Wetlands Conservation Act provides regulations on areas for protecting wetlands. Article 27 of the Conservation and Management of Marine Ecosystems Act prohibits new construction or extensions of buildings or other artificial structures, changes to the structure of public waters, any increase or decrease in the water level or seawater quantity, and any collection of sea sand, quartz sand, soil, and stones from public waters in marine protected areas. Furthermore, local governments that have established marine protected areas can apply for projects on collecting marine wastes, installing marine pollution reduction facilities, and providing support for marine protected areas and residents living near such areas, as per Article 34 of the Conservation and Management of Marine Ecosystems Act and Article 14 of the Enforcement Ordinance Act [

16,

17].

2.3. Establishment Procedure

Paragraph 1 of Article 25 of the Conservation and Management of Marine Ecosystems Act specifies standards for the designation of marine protected areas: (1) sea areas where marine ecosystems maintain primitiveness or sea areas worthy of conservation and academic research for their diverse marine organisms; (2) academic research or conservation-worthy areas for their unusual topography, geological features, or ecology; (3) sea areas worthy of conservation for their high primary production capacity or function as the habitat or spawning areas of marine organisms under protection; (4) sea areas that may represent diverse marine ecosystems or are equivalent to examples thereof; (5) sea areas worthy of special conservation for their beautiful marine or submarine landscape, including coral reefs and seaweeds; (6) areas worthy of conservation to maintain or improve their function as marine ecosystem carbon sinks; and (7) other sea areas prescribed by a presidential decree, which are especially necessary for the effective conservation and management of marine ecosystems [

18].

Procedures for such designation include the stages of preliminary preparation, designation preparation, and designation. In the first stage, the central government recommends a marine protected area and undergoes advance consultations with the corresponding local government. Further, it conducts a detailed survey on the target area to determine the appropriateness of the area as a marine protected area [

18]. In the second stage, the central government prepares a designation plan based on the results of the detailed survey. It then holds a public hearing and a presentation for relevant local residents to emphasize the necessity and expected effects of establishing the target area as a marine protected area and form a sufficient consensus among them [

18]. Subsequently, it formulates, designates, and announces the target area as a marine protected area via the review of the Marine Fishery Development Committee, as per relevant laws. Accordingly, the South Korean government has designated 32 marine protected areas, covering a 1798.692 km

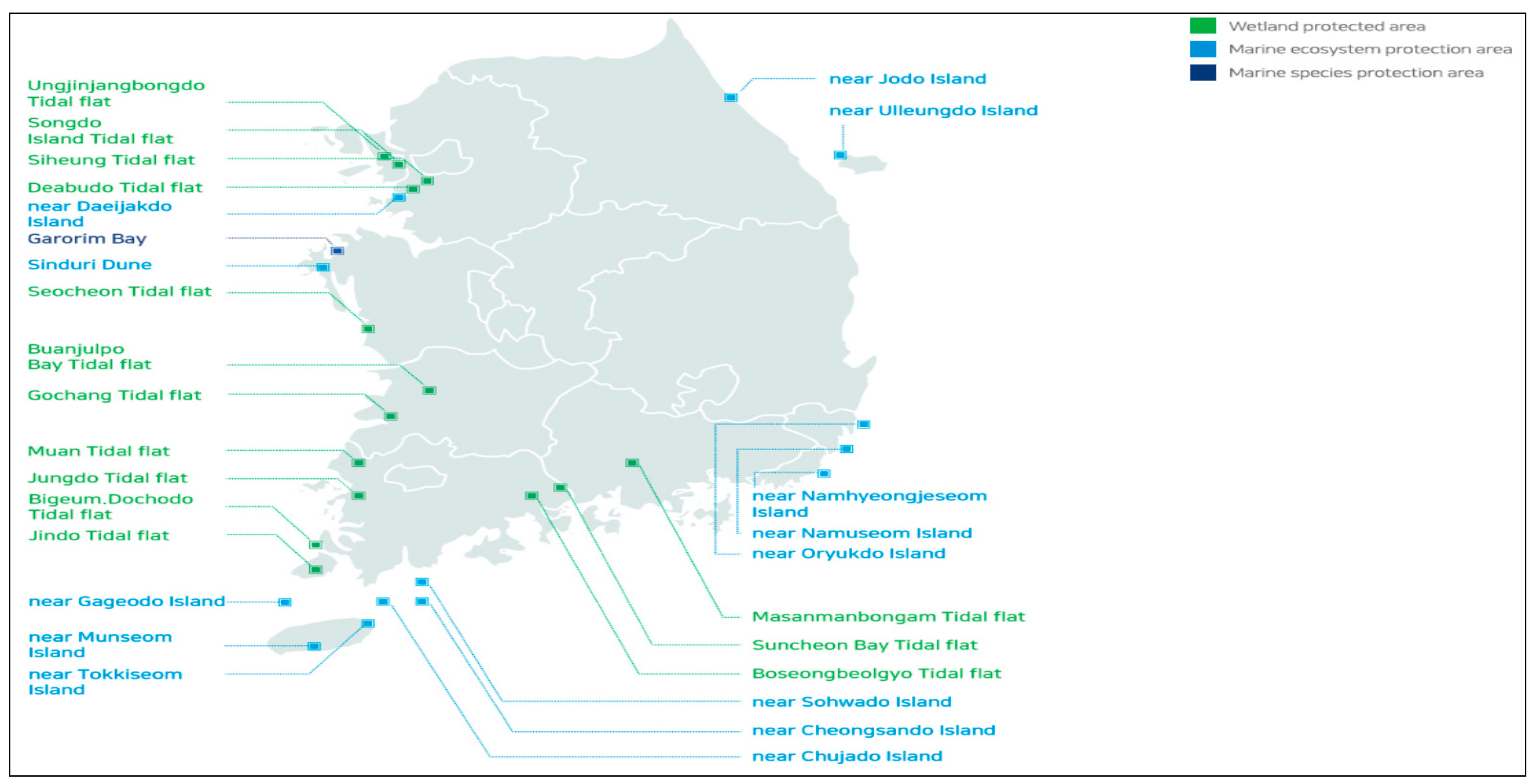

2 area (

Figure 1) [

19]. The South Korea Marine Environment Management Corporation operates the marine protected area center to enhance its management system and reinforce the foundation for the regional autonomous management of marine protected areas [

2].

2.4. Necessity of Establishing Marine Protected Areas in Dokdo

The South Korean government designated the waters surrounding Ulleungdo as the first protected area for marine ecosystems in the East Sea on 24 December 2014. The waters surrounding Ulleungdo are target areas for protecting the habitat and spawning areas of marine organisms that provide excellent submarine landscapes, including coral reefs and seaweeds. The South Korean government had long discussed the necessity of such an establishment. The surrounding waters include various invertebrates [

20,

21].

Figure 2 shows the waters surrounding the northern and western parts of Ulleungdo as a marine protected area. The local government with jurisdiction over the island (Gyeongsangbuk-do) operates the Visitor Centre to inform the public about the value and importance of the marine protected area and increase the public consensus on the establishment of Dokdo and its surrounding waters as marine protected areas [

4]. In the seas surrounding Dokdo, cold and warm currents ensure diversity of marine organisms: approximately 250 species of seaweed, 520 marine invertebrates, including the protected marine organism Dendrophyllia cribrosa, and many commercially viable fish [

22,

23]. Additionally, Dokdo has great ecological, historical, and cultural tourist value.

However, climate change has increased the temperature of the surrounding waters, worsening albinism and damaging the marine ecosystem balance [

24]. The South Korean government should designate Dokdo and its surrounding waters as marine protected areas to overcome this problem. The marine ecosystem of Dokdo’s surrounding waters warrants conservation and protection. As noted, several laws verify the significance of conserving and protecting the area. Thus, although the South Korean government has implemented projects on restoring the diversity of marine organisms to prevent albinism, the designation of Dokdo’s surrounding waters as marine protected areas will maximize the efficiency of such projects.

2.5. Expected Effects of Marine Protected Area on Dokdo

The effects of a marine protected area are as follows. First, from a financial perspective, it increases the cultural, ecological, and social value of the relevant regions. It can also help develop local communities based on an increase in the number of tourists in association with local tourism policies [

25]. Rocin and Nicolas et. al. (2008) [

26] stated that MPA had an impact on local economic gain through the sea-side industry and MPA ecosystem services. In order to maximize Dokdo as a one-of-a-kind potential marine tourism destination, it is crucial to give utmost importance to preserving its cultural heritage, recognizing its territorial significance, and protecting its marine ecosystems. This involves the establishment of marine ecological tourism parks in the surrounding areas of Dokdo, as well as creating cruise tourism routes that connect with Japan, particularly in Ulleungdo. Implementing these strategies will not only revitalize the marine tourism industry but also enhance the overall attractiveness of Dokdo as a sought-after destination. By designating a marine protected area, the government can conserve and restore the marine ecosystem of the target area, manage it as a sustainable tourism resource, and use the area to promote the ocean’s ecological experience and education on marine organisms. Moreover, a marine protected area designation can strengthen the sustainability of local communities.

Second, it can bring positive environmental effects. A marine protected area provides approximately four times more fish species than a commercial fishing region. Furthermore, the reduced influence of human activities and enhanced management of marine protected areas help restore the marine ecosystem and protect the marine environment [

27]. In aspects of marine tourism, marine protected areas will pursue the goal of developing environmentally conscious and sustainable tourism. This entails managing visitor engagement and implementing time restrictions on activities, aimed at promoting the responsible utilization of marine resources. Such policies will be conducive to the conservation of the marine ecosystem and the development of local communities by reducing human activities, at least.

Third, it induces positive political effects. When a certain region is designated as a marine protected area per South Korean laws, the relevant local community responsible for its management can receive support for management projects and systematically implement conservation plans [

16]. Establishing Dokdo as a marine protected area will enable South Korea to promote the value of Dokdo’s marine ecosystem globally and invigorate marine tourism. This move will benefit South Korea and Japan while serving as a measure for actively countering the territorial sovereignty claims of Japan, helping South Korea reinforce its effective control and sovereignty over Dokdo.

Simply put, as socio-economic aspects, the establishment of marine protected areas can lead to augmented income through enhanced catch, heightened public awareness regarding the importance of the marine environment, increased revenue as a marine tourism resource, and a growing interest in the region. Leeworthy observed the Sambos Sambo Ecological Reserve within the Florida Keys National Marine Sanctuary over 4 years in 2001. After assuming that fishermen who experienced the most significant losses from the reserve would derive the greatest future benefits, he conducted a cost–benefit analysis. The findings indicated overall benefits for everyone involved. Specifically, those who incurred losses due to the fishing ban gained 67% of the profit, while those who did not suffer losses gained 22% of the profit [

28].

3. General Characteristics of Dokdo

3.1. Geographical Features

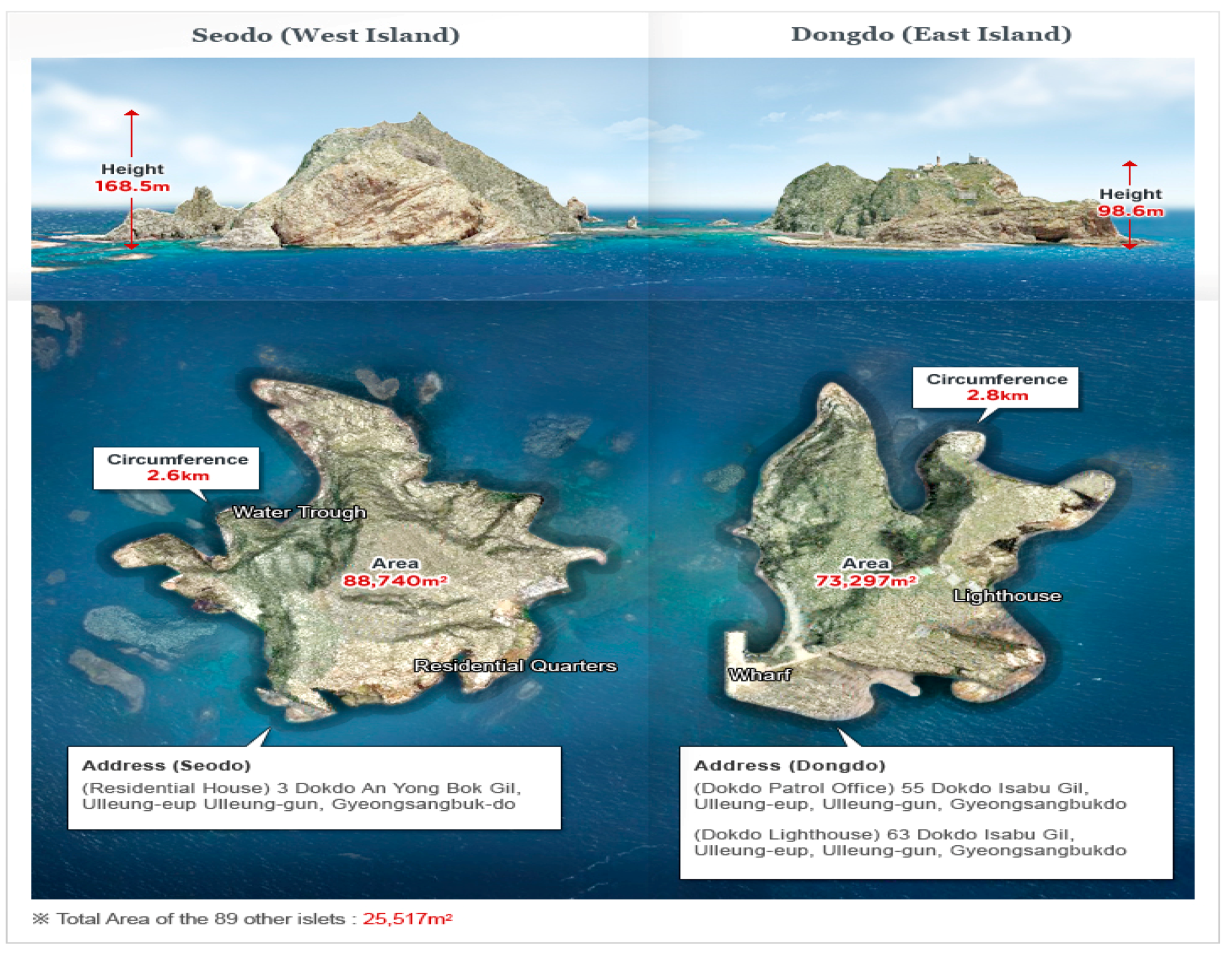

Dokdo comprises eastern and western volcanic islands—Dongdo and Seodo—and 89 surrounding rocks (

Figure 3) [

29]. It is located 87.4 km southeast of Ulleungdo and 157.5 km northwest of Oki Island, Japan, with an area of 187,554 m

2 [

30]. Dokdo is called Takeshima in Japanese and Liancourt Rocks in English [

30]. Dongdo (Seodo) is 98.6 (168.5) m above sea level, with a surface area of 73,297 (88,740) m

2. The distance between them is 151 m [

31]. Dongdo has a manned lighthouse, marine and fishery facilities, and accommodations for the Dokdo Security Police (DSP). At its center is a vertical hole that reaches sea level [

4]. Seodo has a rough cone-shaped peak that is challenging to reach. Jongdeok Choi was registered as the first resident of Dokdo in March 1965. Since then, 14 South Koreans have been registered.

Dokdo hosts approximately forty officers from the DSP, three Dokdo lighthouse keepers from the Pohang Regional Office of Oceans and Fisheries, and two members of the Dokdo Administration Office, from the Ulleung-gun Office [

4].

3.2. Ecologically Significant Marine Area

Dokdo has a mild oceanic climate influenced by warm currents. Its annual average temperature is 12 °C, with average temperatures of 1 °C and 23 °C in January and August, respectively [

23]. In the seas surrounding Dokdo, nutrient-rich water is blended by cold and warm seasonal currents, helping plankton and fish thrive, providing abundant fishing grounds [

32,

33], and housing hundreds of marine species of all types [

34]. However, the waters have recently suffered albinism, a process through which rocky areas become white due to calcareous algae and the loss of seaweed [

22]. This phenomenon has worsened due to rapid rises in water temperatures and seaweed-eating sea urchins, increasing concerns over imbalances in the marine ecosystem [

35]. The MOF has aimed to restore marine diversity in Dokdo since 2015, including diagnosing and observing albinism, removing sea urchins and calcareous algae and releasing their natural predators, and transplanting seaweed [

36].

3.3. Marine Tourism in Dokdo

Dokdo’s entire area was restricted until 2005, when certain areas of Dongdo were opened to limited numbers of public visitors for up to an hour at specific times of the day, with further restrictions in the seabird breeding season from May to June [

37]. In addition, Dokdo is a marine tourist attraction for special purposes given its natural history and socio-cultural value. Marine tourists to Dokdo tend to broadly understand and be interested in its history, culture, and land [

38]. Thus, the behaviors of Korean tourists who visit Dokdo are affected by the general image of Dokdo as a marine tourism destination, as reflected by its territorial protection, resistance to Japan, clean zone, and ecological tourism. Moreover, such behaviors reflect unique cultural characteristics [

38]. As seen in

Table 1, the number of visitors to Dokdo has gradually increased, from approximately 40,000 persons in 2005 to 200,000 in 2018 (and 250,000 in 2013). There are fewer visitors in winter due to the frequent ship cancellations because of rough weather; typically, May and September record the highest number of visitors.

3.4. South Korean Laws and Regulations Regarding Dokdo

Dokdo is an administrative property of the Ministry of Land, Infrastructure, and Transport [

39]. In addition, the Cultural Heritage Administration (CHA) designated Dokdo South Korea’s Natural Monument No. 336 in 1982. It was then designated a “natural reserve” in 1999 [

40]. Moreover, the Ministry of Environment (MOE) designated Dokdo a “specified island” in 2000 to conserve its natural environment and ecosystem. Finally, Dokdo was designated as a natural environment conservation area [

39].

The legal conditions concerning the use of Dokdo are as follows. As Dokdo Is administratively part of Ulleung-gun in Gyeongsangbuk-do (province), the Ulleung-gun Office prepares solutions for issues related to the Dokdo territory and supports its residents. The South Korean Coast Guard and South Korean police patrol the area and provide emergency services. The MOF, MOE, and CHA have adopted management programs to protect Dokdo, including its natural environment, as per relevant laws [

39].

4. Factors behind Hampering the Establishment of Dokdo MPA

4.1. Disputes over Dokdo’s Sovereignty

Since South Korea declared the Peace Line in 1952, South Korea and Japan have faced political and diplomatic issues concerning sovereignty over Dokdo. Japan lodged an official diplomatic complaint against South Korea after the declaration of the Peace Line; both countries exchanged diplomatic documents four times [

41,

42,

43]. Arguments about Dokdo-related issues hinged on legal justifications for the historical sovereignty over Dokdo and the effective right to its control. Japan has attempted to register this island as an internationally disputed region based on constant provocation. Indeed, the local parliament of Shimane Prefecture passed an ordinance designating 22 February as Takeshima Day in 2005. Japan’s Ministry of Education, Science, Sports, and Culture has included distorted content on Dokdo in school textbooks. Moreover, marine exploration ships of the Japan Coast Guard (JCG) approached Dokdo to conduct a hydrographical survey [

43]. Japan has claimed its territorial sovereignty over Dokdo to increase its jurisdiction over the oceans and ultimately reinforce military strategies and gain practical economic benefits [

43]. The decades-long territorial sovereignty issue over Dokdo between South Korea and Japan has been actively examined in various fields, from history to international law, geography, and ecology. South Korea and Japan have investigated the Dokdo issue to academically justify securing territorial sovereignty. Findings from history and international law perspectives are used as territorial sovereignty justifications. Claimant countries must hold a dominant position for their claims for territorial sovereignty in international law to receive international approval for such claims. That is, South Korea and Japan should provide historically clear grounds for their territorial sovereignty.

Japan has called on international observers to recognize Dokdo as a disputed region and prepared judicial measures to solve the issue of territorial sovereignty per the International Court of Justice (ICJ), especially after Japan could not successfully negotiate with South Korea [

44,

45]. Currently, Japan takes a passive attitude toward the judicial management of its disputes over the Kuril and Senkaku Islands based on the intervention of the ICJ. However, in contrast, it is actively urging judicial management of the Dokdo issue. Japan recognizes that it will not suffer a loss even if it loses against South Korea, which exercises effective control over Dokdo [

46,

47]. South Korea has actively opposed Japan’s claim for territorial sovereignty over Dokdo. It has verified grounds for legitimacy in claiming territorial sovereignty over Dokdo via history, geography, and international law [

46]. Thus, reviewing the accuracy of data on Dokdo may help relieve the enraged sentiments of the public on the Dokdo issue in South Korea and Japan and enhance state partnership.

4.2. Undelimited Maritime Boundary in the East Sea

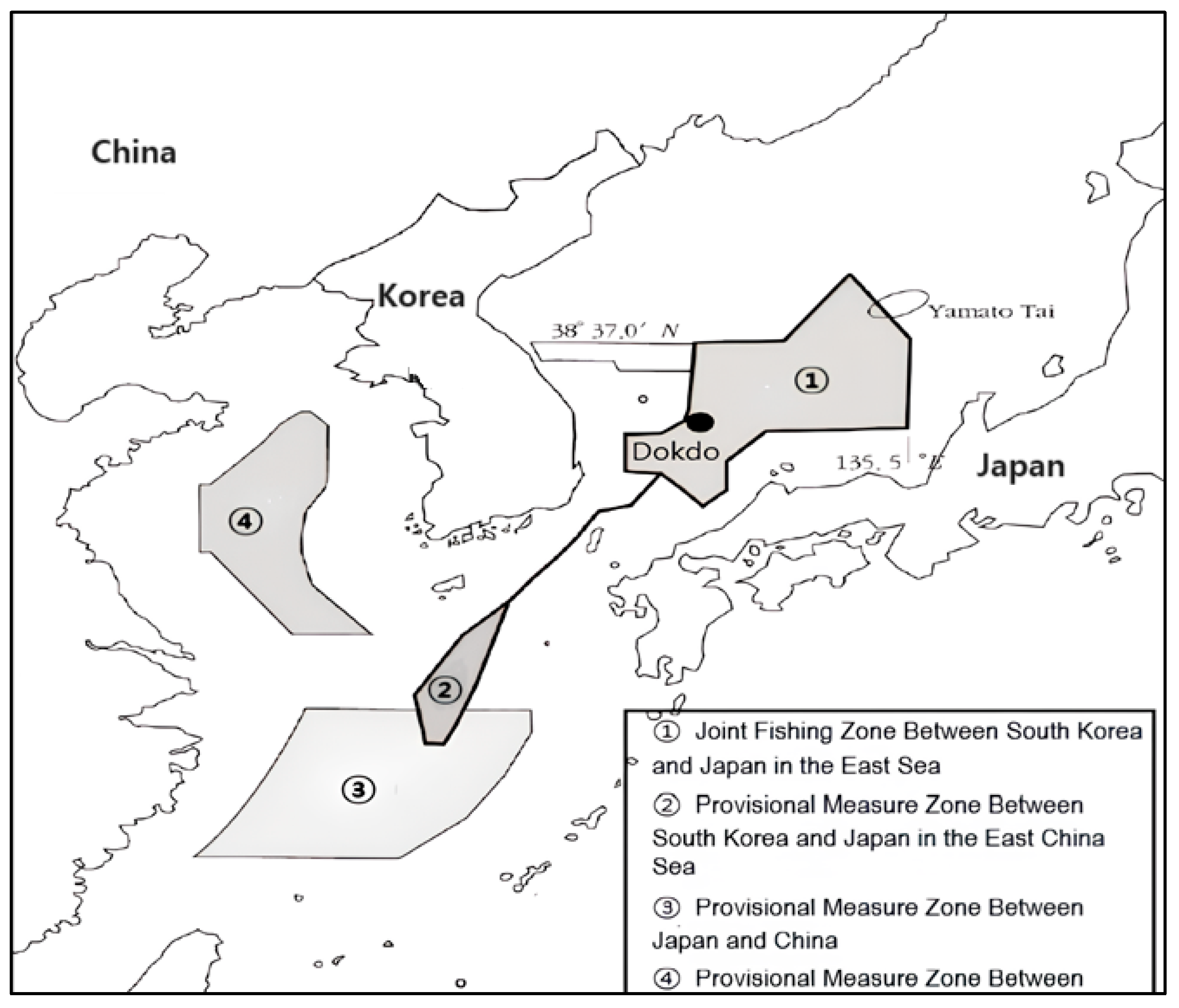

After the UNCLOS was adopted, South Korea and Japan declared their respective 200-nautical mile exclusive economic zones (EEZs) in 1996 (see

Figure 4). The distance between the shores of South Korea, China, and Japan does not exceed 400 nautical miles in most cases, and their EEZs and continental shelves overlap in certain waters [

48,

49]. Therefore, the maritime boundary for the waters surrounding the South Korean peninsula has not been delimited; this is associated with disputes on territorial sovereignty over Dokdo. According to the UNCLOS, coastal states can claim jurisdiction under the territorial sea, contiguous zone, EEZ, continental shelf, and adjacent resources. The tense conflict about Dokdo between South Korea and Japan has hindered the maritime boundary delimitation for the waters surrounding this island [

41]. Per the UNCLOS, a coastal state has sovereign rights for exploring, exploiting, conserving, and managing the natural resources, whether living or non-living, of the waters overlying the seabed, the seabed, and its subsoil, and rights to other activities for the economic exploitation and exploration of the zone, such as the production of energy from the water, currents, and winds in the EEZ [

50]. Moreover, the coastal state can exercise exclusive jurisdiction in the relevant provisions of the Convention regarding the establishment and use of artificial islands, installments, and structures for marine scientific research. The coastal state also has general duties and prescriptive and enforcement jurisdiction to protect the marine environment [

51,

52]. Though coastal states with overlapping waters eventually fail to delimit a maritime boundary for such waters, the states have the rights and duties specified by this Convention. Nevertheless, this Convention notes that coastal states that face overlapping water issues must enter into provisional arrangements of a particular nature and avoid jeopardizing or hampering the final agreement during this transitional period [

53].

This article serves as a regulation that restricts the application of rights of coastal states to overlapping waters. Coastal states may clash in the exercise of rights over overlapping waters [

54,

55]. For example, the JCG informed the International Hydrographic Organization of its plan to conduct a hydrographic survey and marine scientific research in Dokdo’s surrounding waters on 14 April 2006 [

56,

57,

58]. Unilateral action by one state where there is a sharing of certain sea area does not help two states to build up cooperation. It should be noted that unilateral action should not hamper regional cooperation or coordination. Effective provisional agreements on the overlapping waters between South Korea and Japan include the 1974 Agreement on the Joint Development of the Southern Part of the Continental Shelf adjacent to the Two Countries [

59] and the 1998 Agreement on Fisheries [

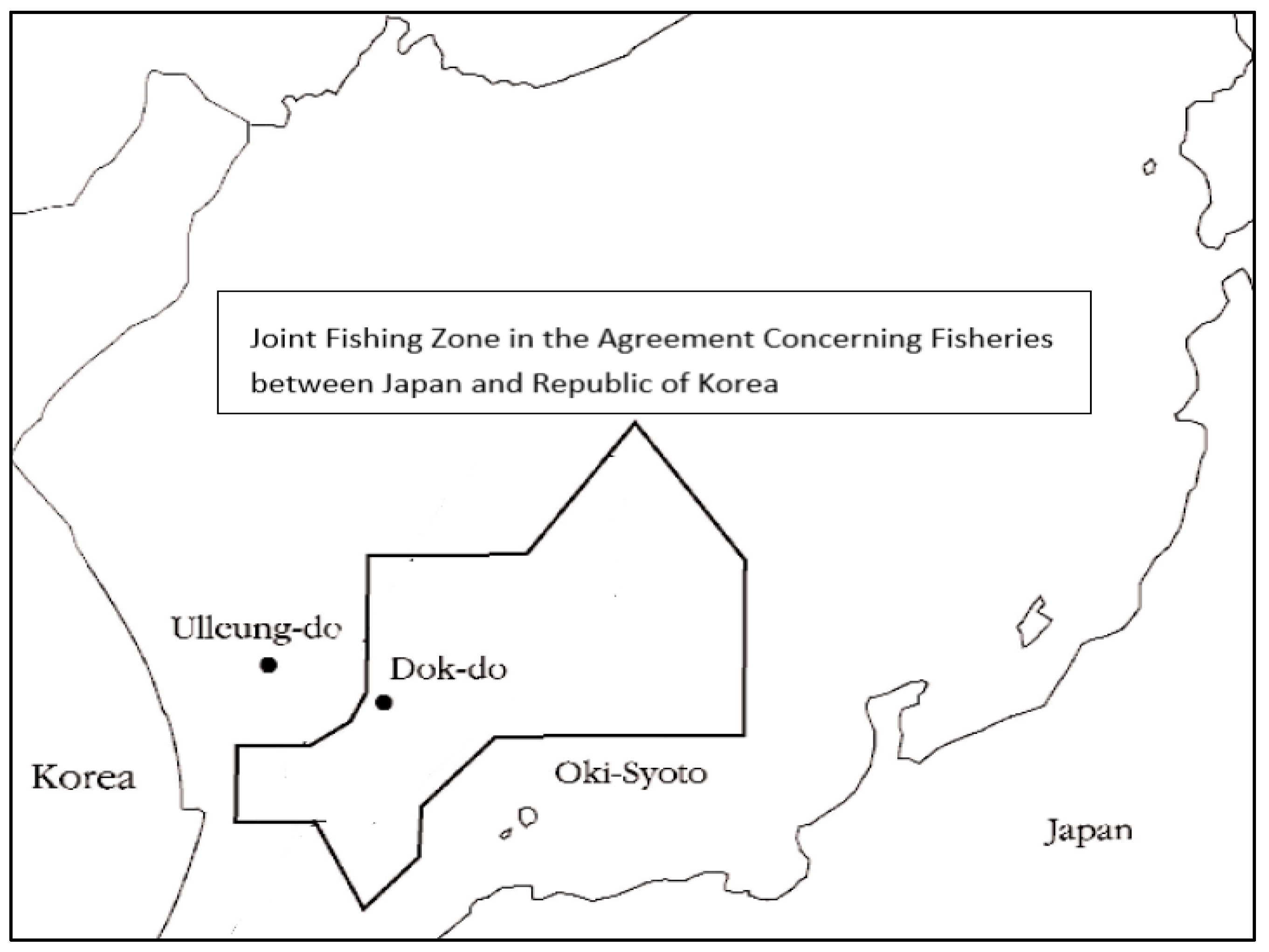

60], concluded to conserve living resources.

4.3. South Korea–Japan Fisheries Agreement

Regarding fishery issues in the EEZ, including overlapping waters, the 1998 Agreement between Japan and the Republic of South Korea Concerning Fisheries [

61] notes that both countries should annually inform their counterpart on conditions allowed to the public, including fishers, such as catchable species of fish, fishing quota, and fishing zones (

Figure 5). Moreover, they should quickly release counterpart ships and crews arrested or detained after appropriate guarantees or other equivalent documents are submitted. They must comply with international laws on navigation, maintain fishing safety and order by fishing vessels, and implement the right measures to manage marine accidents smoothly and swiftly [

62]. The EEZ in the East Sea comprises overlapping waters with issues on territorial sovereignty over Dokdo. This zone is open to the fishing vessels of both countries; they can exercise jurisdiction for fishing in this zone [

63]. As this agreement applies only to the fishing field, it is not relevant to territorial sovereignty over Dokdo’s issues, maritime boundary delimitation in the EEZ, and control over the continental shelf. First, the agreement does not apply to territorial seas because it targets the EEZ. The agreement intends to regulate fishing-related issues before the final maritime boundary delimitation in the EEZ. As in the Minquiers and Ecrehos Case decided by the ICJ in 1953, the UK and France agreed to establish a joint fishing zone in the waters surrounding the islet groups in the Minquiers and Ecrehos. Despite this agreement, the ICJ decided that it does not affect territorial sovereignty over the target islets [

64]. On 1 March 2001, the Constitutional Court of South Korea published a decision on a constitutional appeal that the fisheries agreement does not affect territorial sovereignty over Dokdo despite the location of this island in middle waters where fishers from South Korea and Japan can freely catch fish. It also decreed that the agreement is irrelevant to the territorial sea issue [

65]. In another maritime dispute between El Salvador and Honduras, a Special Chamber of the ICJ decided that the joint water system established by the corresponding countries, which succeeded the prior countries that historically possessed the target waters, is separate from territorial sovereignty over islands located in joint waters [

66]. This precedent indicates that an agreement on a maritime boundary between countries does not affect their territorial sovereignty.

4.4. Effect on Formulating a Marine Protected Area in Dokdo

Dokdo is located in the overlapping sea area of EEZ between South Korea and Japan. Waters without a delimited maritime boundary can induce sovereignty and jurisdiction disputes between the countries concerned. Such countries have duplicated rights to possess the EEZ and continental shelf and legal grounds for somewhat justifying their rights in this zone. The UNCLOS specifies that coastal countries should not hamper the fulfillment of duties for negotiations based on trust and good faith to conclude provisional agreements with countries adjacent to overlapping waters and the reaching of the final agreement on maritime boundary delimitation. Hence, South Korea and Japan signed the Agreement between Japan and the Republic of South Korea Concerning Fisheries in 1998 and established middle waters in the East Sea, where fishing vessels of both countries can catch fish. In such waters, each country can exercise jurisdiction overfishing. The agreement only regulates fishing-related issues and is separate from disputes about territorial sovereignty over Dokdo; thus, it does not affect the exercise of sovereignty and exclusive jurisdiction of coastal states over Dokdo, except for fishing. Indeed, Mauritius initiated arbitral proceedings against the UK in December 2010, arguing that the UK declared a marine protected area near the Chagos Archipelago unilaterally and that the UK’s action of prohibiting fishing in the marine protected area violated the UNCLOS. The Permanent Court of Arbitration (PCA) decided that the UK violated the UNCLOS based on its action of setting a marine protected area one-sidedly without discussions with Mauritius [

67]. PCA notes that the UK violated Paragraph 3, Article 2 of the UNCLOS, which indicates that coastal states should exercise sovereignty over the territorial sea per the Convention; Paragraph 2, Article 56, which indicates that coastal states should properly consider the rights and duties of other states in the process of exercising their rights in the EEZ; and Paragraph 4, Article 194, which notes that coastal states should refrain from unjustifiable interference with activities conducted by other states in the exercise of their rights in taking measures to prevent, reduce, or control marine environmental pollution [

67]. Regarding jurisdiction over judgments, the court decided that issues on the position of coastal states related to the Chagos Archipelago are associated with disputes on territorial sovereignty and that it does not have jurisdiction over disputes over the Chagos Archipelago between Mauritius and the UK [

67]. The establishment of a marine protected area should, therefore, be treated as a separate issue from any dispute on territorial sovereignty. When South Korea plans to establish Dokdo and its surrounding waters as marine protected areas, the government should intensively review the UNCLOS violations per the aforementioned case of disputes over the Chagos Archipelago. Furthermore, the South Korean government needs to consistently persuade the international community to establish Dokdo MPA.

5. Legality, Legitimacy, and Cooperation for Establishing Dokdo MPA

5.1. State Obligation in the Overlapping Sea Area of EEZs

Dokdo is located amid waters in which the EEZs of South Korea and Japan overlap. This zone includes only provisional waters, as per the Agreement between Japan and the Republic of South Korea Concerning Fisheries, without a delimited maritime boundary. The issue of territorial sovereignty over Dokdo hinders the agreement between South Korea and Japan on the final maritime boundary delimitation in this zone and disturbs their cooperation, such as on marine environment protection. Article 74 of the UNCLOS mentions the rights and duties of coastal states in waters without a delimited maritime boundary. Paragraph 1 notes that the delimitation of the EEZ between neighboring states should be made by agreement based on international law. Paragraph 3 stipulates the duties of coastal states as follows:

“Pending agreement as provided for in Paragraph 1, the States concerned, in a spirit of understanding and cooperation, shall make every effort to enter into provisional arrangements of a practical nature and, during this transitional period, not to jeopardize or hamper the reaching of the final agreement. Such arrangements shall be without prejudice to the final delimitation” [

52].

South Korea and Japan have established provisional waters based on the UNCLOS and the Agreement between Japan and the Republic of South Korea Concerning Fisheries. One-sided actions of coastal states in overlapping waters occasionally threaten neighboring states, thereby violating Paragraph 3, Article 74 of the UNCLOS. Such coastal state behaviors are clearly highlighted in international precedents represented by the Aegean Sea Continental Shelf case between Greece and Turkey in 1976, the Guyana and Suriname arbitration in 2007, and the dispute concerning the delimitation of the maritime boundary between Ghana and Ivory Coast in 2017.

In the aforementioned case between Greece and Turkey, the Turkish State Petroleum Company gained approval for oil exploration on a continental shelf in the overlapping waters surrounding Greece and Turkey and launched seismic wave exploration without discussions with Greece [

68]. Greece requested the ICJ to conduct provisional measures, stating that Turkey’s actions of unilateral exploration and scientific research brought irreparable damage to the overlapping waters surrounding both countries, which did not include a delimited maritime boundary, and that these actions will obstruct their favorable relations. The ICJ noted that Turkey’s exploration actions did not cause irreparable damage to the rights of Greece based on the following grounds: (1) no complaint has been made that this form of seismic exploration involves any risk of physical damage to the seabed or subsoil or their natural resources; (2) seismic exploration activities undertaken by Turkey are all transitory and do not involve the establishment of installations on or above the seabed of the continental shelf; (3) no suggestion has been made that Turkey has embarked upon any operations involving the actual appropriation or other use of the natural resources of the areas of the continental shelf in dispute [

68]. As for the arbitration case of Guyana and Suriname in 2007, the Tribunal presented standards for decisions based on the irreparable damage from the one-sided actions of a coastal state in overlapping waters [

69]. Guyana allowed CGX Resources Inc., a Canadian company, to perform oil exploration and development in overlapping waters surrounding Guyana and Suriname. When CGX vessels conducted oil exploration in the overlapping waters on 3 June 2000, they were ordered by vessels of the Navy of Suriname to leave the zone immediately; armed conflict ensued. Guyana initiated arbitral proceedings accordingly, and the Tribunal decided that Guyana and Suriname violated their obligations under Articles 74 (3) and 83 (3) of the UNCLOS [

68]. The Tribunal mentioned the Aegean Sea Continental Shelf case between Greece and Turkey in 1976 as a precedent and stated that the ICJ’s decision in the cited case distinguishes between activities of a transitory character and those that risk irreparable prejudice to the position of the other party [

68].

Accordingly, the Tribunal regarded seismic wave exploration as an allowed activity in overlapping waters and drilling as an action that can cause permanent physical changes to the marine environment, thus requiring an agreement or discussion with neighboring states [

68]. As noted, a coastal state should review the status of violation against obligations indicated in Paragraph 3, Article 74 of the UNCLOS when it plans to exercise its rights unilaterally in overlapping waters. However, the establishment of a marine protected area is a measure that a coastal state can implement to protect the marine environment and marine ecosystems. As this action benefits coastal and neighboring states, it is recommended not to prohibit neighboring states excessively from exercising their rights, such as fishing and navigation rights.

5.2. Coastal States’ Rights and Exclusive Jurisdiction

UNCLOS guarantees the exclusive sovereignty of coastal states over territorial seas. Exclusive sovereignty refers to independent and exclusive rights of coastal states, including fishing rights, obligations of protection and preservation of the marine environment, marine scientific research, rights to develop and explore natural resources, and legal execution rights. Per Article 56 of the UNCLOS, in EEZs, the coastal state has sovereign rights for exploring and exploiting, conserving, and managing the natural resources, whether living or non-living, of the waters overlying the seabed and the seabed and its subsoil. It includes rights for other activities for the economic exploitation and exploration of the zone, such as the production of energy from the water, currents, and winds. Coastal states can also exercise jurisdiction as provided for in the relevant provisions regarding the establishment and use of artificial islands, installations, and structures; marine scientific research; and protection and preservation of the marine environment [

70]. The Territorial Sea and Contiguous Zone Act notes that Dokdo belongs to the territorial sea of South Korea, and South Korea exercises exclusive sovereignty over this island. South Korean laws indicate the status of Dokdo as the sovereign territory of South Korea [

71].

Regarding the exercise of coastal state rights to conserve the marine environment indicated in the UNCLOS, South Korea designated and announced Dokdo as South Korea’s Natural Monument No. 336 to conserve the natural environment and ecosystem of Dokdo, as per the Cultural Heritage Protection Act. It also formulated the Special Act on the Conservation of the Ecosystems in Island Areas Including Dokdo to designate and manage Dokdo as a specified island. Additionally, Dokdo is designated as a natural conservation area per the National Land Planning and Utilization Act. The laws specify that Dokdo is the national territory of South Korea. Hence, South Korea has exclusive and active rights as a coastal state to establish Dokdo’s surrounding waters as a marine protected area to protect the marine ecosystem and environment of this zone actively, as per the Conservation and Management of Marine Ecosystems Act. However, Dokdo is located amid a provisional zone in overlapping waters surrounding South Korea and Japan, established per the Agreement between Japan and the Republic of South Korea Concerning Fisheries. Thus, South Korea can establish Dokdo’s surrounding waters as a marine protected area without excessively extending the range of establishment of this area and provoking Japan based on actions such as the restriction of fishing rights. The establishment of Dokdo as a marine protected area would protect the marine ecosystem of its surrounding waters, benefiting both South Korea and Japan.

5.3. Effective Control over Dokdo and South Korean Laws

Discussions concerning the issue of territorial sovereignty over Dokdo have emphasized that South Korea exerts effective control over Dokdo. South Korea’s argument for sovereignty over Dokdo is based on historical, geographical, and international law legitimacy [

72]. The grounds are as follows: (1) the operation of the South Korean police stationed in Dokdo to defend the island; (2) the operation of the South Korean military to defend Dokdo’s territorial sea and airspace; (3) the application of various laws to Dokdo; (4) the installation and operation of different facilities, including the lighthouse, in Dokdo; and (5) South Korean residents live in Dokdo. These grounds are based on an ancient claim. South Korea argues that it implemented a series of measures after the Second World War and recovered its exercise of effective sovereignty over Dokdo, which was severed during the Japanese colonization, based on the applied measures. South Korea also asserts that it has constantly exercised effective control over Dokdo since the re-exercise of sovereignty over Dokdo [

73]. The country also adopts the geographical unity of Dokdo with Ulleungdo or the principle of adjacency based on geographical proximity as grounds for its claim to the territory. South Korea’s claims of effective control over Dokdo closely relate to its historical claim on the territory of Dokdo via international law. South Korea has exercised effective control over Dokdo based on legislative and administrative power per the Special Act on the Conservation of the Ecosystems in Island Areas Including Dokdo and the Act on the Sustainable Use of Dokdo. South Korea argues that given the constant, peaceful application of legislative, administrative, and judicial functions, Dokdo is a territory of South Korea. There are residents and members of the DSP on the island [

72]. Given these facts, South Korea may legitimately establish the waters surrounding Dokdo as a marine protected area to protect the marine ecosystem and environment of this island, according to South Korean laws.

5.4. The Need for Regional Cooperation Regime of Marine Environmental Protection

South Korea and Japan have encountered challenges in developing cooperation systems in fields that require partnership, such as in the protection of the marine environment. A coastal state has prescriptive and enforcement jurisdiction in its EEZ regarding the pollution caused by ocean dumping and vessels. Therefore, the exercise of enforcement jurisdiction by one or all the coastal states in overlapping waters can yield conflicts among the states concerned. For example, in the case of the South China Sea Arbitration between the Philippines and China in 2016, the Tribunal admitted that China’s actions of reclaiming land and rocks and constructing artificial islands in the Spratly Islands had caused serious and irreparable damage to the marine ecosystem surrounding the islands. Moreover, the harmful fishing activities of Chinese fishers and the catching of endangered fish violated regulations on marine environment protection described in the UNCLOS [

74]. Thus, coastal states should focus on violations against their obligations of protecting the marine environment when they perform resource development, such as oil exploration and drilling and facility construction.

The issue of territorial sovereignty over Dokdo can be expected to delay maritime boundary delimitation considerably in the EEZ between South Korea and Japan. Under this assumption, South Korea should implement measures for protecting and conserving the marine environment and ecosystem of Dokdo’s surrounding waters to prevent conflicts by exercising jurisdiction in overlapping waters. Cooperation between South Korea and Japan is necessary to establish Dokdo’s marine protected areas. Accordingly, we propose the establishment of marine protected areas as a measure for enhancing cooperation between South Korea and Japan. The establishment will reduce the tension between the countries caused by the issue of territorial sovereignty. This measure will also help form and advance collaborative relations between South Korea and Japan toward achieving global values associated with marine environment protection and marine ecosystem conservation. Furthermore, it is essential to carry out a joint environmental impact assessment to identify the necessity for establishing a marine protected area around Dokdo.

6. Discussion

As Dokdo is an island, it has maritime jurisdiction zones including the territorial sea and EEZ. Dokdo is located amid waters in which the jurisdiction of South Korea and Japan overlap, and maritime boundary delimitation has not been completed. According to the fisheries agreement between Japan and South Korea, Dokdo is in a provisional zone. Japan has consistently claimed its territorial sovereignty over Dokdo to expand its maritime jurisdiction and territory.

As in the case of disputes over the Chagos Archipelago between Mauritius and the UK, the establishment of a marine protected area without agreement with neighboring coastal states can initiate illegality conflicts. Thus, South Korea should thoroughly review violations of Articles 2 (3), 56 (2), and 194 (3) of the UNCLOS before establishing Dokdo as a marine protected area.

If the range of the marine protected area surrounding Dokdo does not exceed three nautical miles based on its surrounding waters, as in the range of the marine protected area of Ulleungdo, Article 56 of the UNCLOS will not be applied. Moreover, Article 2 of the UNCLOS relates to sovereignty over territorial seas. As South Korea has already exercised its sovereignty over Dokdo as a coastal state, it does not violate the corresponding article. Article 194 (4) of the UNCLOS specifies that coastal states should avoid unjustifiable interference through activities conducted by other states in the exercise of their rights and in pursuance of their duties in taking measures to prevent, reduce, or control the pollution of the marine environment [

75]. Thus, South Korea should minimize the range of establishing a marine protected area in Dokdo’s surrounding waters to derive results that reflect South Korea’s consideration of the rights of Japan.

Furthermore, South Korea should broadly announce that its establishment of Dokdo as a marine protected area is not a measure that infringes on the rights of neighboring states, such as fishing and navigation rights per South Korean laws, but a limited measure to gain administrative and financial support toward achieving political influence for conserving and protecting the marine ecosystem of Dokdo. Hence, it should be verified that South Korea has never unduly prevented Japan from exercising its rights or performing activities for achieving its obligations based on the establishment of a marine protected area.

Regarding disputes over the Chagos Archipelago, the Tribunal notes that coastal states involved in disputes over territorial sovereignty should perform measures for safeguarding the marine environment, implemented to protect sovereignty, before the establishment of a marine protected area, and accomplish satisfactory results among the states concerned [

69]. South Korea may need to reach an agreement or exchange information with Japan at the least before establishing Dokdo and its surrounding waters as marine protected areas.

7. Conclusions

Dokdo is known for the considerable diversity of its marine organisms. However, climate change has increased the water temperatures in its surrounding waters, significantly threatening the balance of the marine ecosystem in this zone. Thus, South Korea should designate and manage Dokdo as a marine protected area to protect and conserve its marine ecosystem. On 19 December 2014, the MOF designated the waters surrounding Ulleungdo as a marine protected area. The range of the designation includes the waters surrounding the northern and western parts of Ulleungdo, extending three nautical miles. Gyeongsangbuk-do, the administrative district responsible for the management of Dokdo, announced that it will expand its marine protected areas for ecological reasons. Indeed, there has constantly been a demand for establishing Dokdo as a marine protected area like Ulleungdo to protect the habitats and spawning areas of protected marine organisms and conserve the excellent submarine landscape, including coral reefs and seaweeds.

This study examined the necessity of establishing Dokdo as a marine protected area and reviewed its legal grounds from the perspective of South Korea. Recently, albinism aggravated by climate change has induced significant damage to Dokdo’s marine ecosystem. The establishment of Dokdo and its surrounding waters as marine protected areas will, thus, serve as a crucial legal measure for effectively conserving and protecting the marine ecosystem of this island.

Regarding the social, cultural, and historical values of Dokdo, the establishment of Dokdo as a marine protected area will contribute to protecting the marine ecosystem of Dokdo, advancing local communities, globally promoting Dokdo in association with marine tourism, and reinforcing South Korea’s sovereignty over Dokdo and relevant marine areas based on its active exercise of sovereignty as a coastal state. Furthermore, the protection of overlapping waters will benefit South Korea and Japan. Thus, this action can serve as an opportunity for relieving diplomatic tension between these countries and enhancing their cooperation.

Nonetheless, there is a potential for Japan to engage in a unilateral lawsuit to international courts, depending on whether it breaches the UNCLOS provisions related to the establishment of a marine protected area in overlapping waters, independent of the sovereignty matter concerning Dokdo. With regard to the possibility of a unilateral lawsuit, South Korea submitted a declaration on excluding it from compulsory procedure under Article 298 of the UNLCOS on 18 April 2006. If South Korea sets Dokdo and surrounding waters as marine protected areas and Japan raises a unilateral lawsuit, it is highly likely to go to an arbitral tribunal. The protection of Japan’s rights requires a strategic approach that minimizes the scope of establishing Dokdo’s marine protected area. Furthermore, there is a need to communicate to Japan and the public that Dokdo’s marine protected area is aimed at providing administrative and financial support to achieve policy objectives related to the preservation and safeguarding of marine ecosystems. It should be clarified that these measures are not intended to impinge upon the rights of neighboring states, such as the restriction of fishing and navigational rights in accordance with domestic law. The South Korean government needs to demonstrate that its unilateral establishment of marine protected areas does not unfairly impede Japan’s exercise of rights and fulfilment of obligations.

Given the location of Dokdo in overlapping waters without a delimited maritime boundary, South Korea should thoroughly review violations against regulations on the establishment of a marine protected area described in the UNCLOS to minimize diplomatic conflicts with Japan. South Korea may need to reach an agreement or exchange information with Japan. In the case of disputes over the Chagos Archipelago, the Tribunal concluded that coastal states should discuss and exchange information with the other party before establishing a marine protected area. Furthermore, in establishing Dokdo and its surrounding waters as marine protected areas, South Korea needs to coordinate and cooperate with Japan to avoid the possibility of conflicts and take measures for managing conflicts. In order to achieve this, South Korea and Japan may consider the establishment of a regional protection committee to enhance the collaborative framework in the East Sea, including Dokdo, by conducting a joint environmental impact assessment.