Abstract

(1) Background: A precise and comprehensive diagnosis of the needs of older adults is the basis for developing concepts of aesthetic functional and spatial arrangements of public open spaces in residential areas that meet their expectations, termed “age-friendly residential areas” (AFRAs). The primary objective of the research was to determine the needs of older people concerning their preferences for the development of AFRAs. (2) Methods: This research was conducted on the basis of a survey conducted from October 2021 to April 2022, involving 1815 older citizens from Poland, Germany, the United Kingdom, the United States, Canada, Croatia, Italy, Lithuania, and Slovakia. The research aimed to determine the needs of older people regarding their preferences for the development of AFRA public open spaces. The developed research approach made it possible to answer the following research questions: (1) What are the needs of different generations of older adults, differentiated by gender and lifestyle, in terms of spatio-functional and landscape aspects with regard to the open spaces of residential estates? (2) Do older citizens from different countries living in various estates (single-family, multi-family) have the same expectations towards AFRAs? (3) Results: The research results showed a high convergence of preferences among older people regardless of gender, age group, or type of residential estate they live in (multi-family/single-family). Slight differences in AFRA preferences were noticed between Polish and non-Polish older adults, most often due to cultural habits. A correlation between the landscape attractiveness and aesthetics of the estate and the comfort of life for the older population, as well as their impact on the final assessment of the estate, was confirmed. As a result of the research, 33 spatio-functional and 16 landscape factors of AFRAs were identified and ranked.

1. Introduction

Urbanisation and population ageing are intertwined factors in the development of adapted urban spaces. Understanding the relationship between the environment and well-being is fundamental to the development of age-friendly urban planning, for instance, in the context of ageing [1]. A proper and comprehensive diagnosis of the needs of older adults is the basis for the development of aesthetic spatio-functional layouts of residential open spaces that meet their expectations, namely “age-friendly estates”. Ageing is a natural process associated with physiological changes. A reduction in the metabolic rate by about 7% occurs every decade after the age of 30. The specifics of the older population require solutions that influence the ability to function more efficiently, enhance activity among older adults, the improvement of well-being, and integration with the immediate environment, which is emphasised by the WHO [2,3,4]. The intense process of societal ageing, not only in Europe, is a catalyst for actions towards orienting urban public spaces to the needs of older adults [5]. This process is multifaceted and complex. The evolution of spatio-functional arrangements entails landscape changes (transformations) and must take into account aspects of safe use of urban spaces [6].

The landscape of urban public spaces should also be an essential element of the multi-criteria assessment of the quality of life for all age and social groups and should be especially taken into account in planning the aesthetic forms of residential estates in the context of the older population. Above all, it gains particular importance for older citizens, who have more free time. A more stabilised and peaceful lifestyle promotes the contemplation of the landscape in spatial, architectural, functional, aesthetic, historical, or recreational terms. The complexity and multifaceted nature of the concept raise questions about the impact of landscape values on the quality of life of older adults.

The landscape is often perceived as a positive element that supports the ageing process in a given place [7]. Moreover, it significantly influences physical activity, intellectual engagement, and the overall willingness to act and take on new challenges [8]. Despite growing interest in this topic, there remains a need for more integrated research that considers both functional and landscape aspects in the context of older adults.

Modern, age-friendly functional and spatial arrangements with aesthetic landscapes should be integral parts of cities and contribute to improving the quality of life for older adults. Their proper structure should also support the process of extending active lifestyles in this age group. Central and Eastern European cities are characterised by significant diversity in their building technologies and functional–spatial solutions [9] and, thus, landscape diversity [10,11]. This presents a significant challenge for urban planners designing spaces for older adults and people with disabilities. Some outdated architectural solutions do not provide comfort for older adults, even after remedial measures [12]. Therefore, new comprehensive solutions and changes in functional–spatial structures are increasingly preferred [13]. The aim of this research was to determine the needs of older people regarding their preferences for the development of AFRA public open spaces. The research focuses on functional–spatial and landscape (aesthetic) elements of public open spaces.

The research approach allowed the authors to answer the following research questions: (1) What are the needs of older people, differentiated by age, gender, and lifestyle, in terms of functional–spatial and landscape aspects of open spaces in residential areas? (2) Do older adults from different countries, living in different types of housing (single-family, multi-family), have the same expectations regarding AFRAs? The answers to these research questions were obtained through a survey conducted from October 2021 to April 2022, involving 1815 older citizens from Poland, Germany, the United Kingdom, the United States, Canada, Croatia, Italy, Lithuania, and Slovakia. The random sample was sufficiently large to ensure that the results were representative, with a maximum margin of error of 3% and a confidence level of 95%. The conducted research confirmed the research hypothesis that the landscape is as important to older adults as the functionality of public open spaces in residential areas.

Innovation

When assessing the age-friendliness of residential areas, it is essential to consider functional–spatial and landscape elements as an inseparable whole of the public open spaces in residential areas, as they mutually influence well-being. To date, these two categories have been assessed separately, especially in the context of older adults [14]. Previous studies focused on specific aspects of age-friendly spatial arrangements in terms of functional–spatial aspects, such as the accessibility of services and infrastructure like shops, clinics, pharmacies, and public transport stops [15,16]; the safety of well-lit and monitored spaces with organised pedestrian traffic [17]; or the architectural adaptation of homes and buildings to meet the needs of older adults by eliminating barriers [18,19,20]. In the landscape aspect, research focused on the accessibility and quality of green spaces, such as parks, squares, or gardens [14,21]; the availability of recreational areas like walking paths [22]; social integration features like gazebos, benches, and meeting places [23,24,25]; and the aesthetics of the surroundings, including analyses of the quality and diversity of plantings, the presence of water, and small architectural elements [26].

One attempt to distinguish aesthetic and planning criteria affecting the quality of life based solely on literature review [27] was identified, where the scope of the identified factors was limited mainly to greenery and the density of development. Hence, the proposed approach, which is based on a comprehensive list of elements that consider landscape values to assess the age-friendliness of residential areas, is innovative and fills a gap in the literature. The list of existing indicators in the approach to AFRA assessment was supplemented and expanded to include eight functional–spatial categories: transportation and communication functionality, recreational, commercial and service, cultural and educational, informational, protective, neighbourhood, and planning. Additionally, four categories of landscape aesthetics were included: green–blue infrastructure, urban layouts, the appearance of spatial objects, and the orderliness and cleanliness of the surroundings.

The limitations of previous studies confirm that the planned comprehensive approach to AFRA assessment is necessary to better understand and effectively meet the needs of the growing social group of older adults in a complementary manner. Determining the importance of specific elements of residential area development will guide revitalisation efforts that consider the priorities of older adults.

2. Literature Review

2.1. Lifestyle and Social Activity of Older Adults

The older population is very diverse [13], and so the forms of activity among older adults are varied. In gerontological research and related sciences, various forms of activity by older people are distinguished and associated with lifestyles and individual predispositions [28]. The basic division includes active and passive styles, but [28] indicated another classification (as presented in Table 1). Therefore, when a survey is being developed for older adults, questions about their lifestyle should be posed.

Table 1.

Lifestyles of older people resulting from preferred activities. Source: own elaboration on the basis of [28].

The lifestyles of older adults also vary from country to country depending on different traditions, established cultural patterns, and even levels of public awareness [29,30,31]. In Poland, the lifestyle of the older population significantly differs from that of their peers in EU countries, particularly in Western and Nordic countries. This is influenced by an insufficient awareness of the health benefits of sport, by cultural patterns and historical backgrounds, and by the health and social care system in the country, which does not always provide older citizens with quick access to appropriate medical care. The difference in the lifestyles of older people also stems from the division of age among the older population. In societies undergoing globalisation, leisure time activities—just like all cultural phenomena—are undergoing significant transformations. There have been changes in the preferred lifestyle that promote a healthy, eco-friendly, and active approach, as well as an increasing awareness of the importance of tourism and recreation for improving the quality of life [32].

For the purpose of this study, it was assumed that among the lifestyles distinguished by [28], two, i.e., the passive and home-centred styles, can be considered inactive or low-activity lifestyles, and the rest fall into an active way of life. Hence, the level of preference was examined with a division into these two types of activities.

2.2. Factors Influencing the Longevity of Older People

Differences in health status and mortality have been a research field of social epidemiology and public health. Most of the studies in this field focused on differences between social groups at various administrative–geographical levels, especially at the regional level [33,34,35]. A long and healthy life is one of the most universally valued goals of humanity [36]; hence, average life expectancy is a useful indicator for comparing social, economic, and cultural inequalities. Material resources, inequalities in income, and differences in education are also key life expectancy factors [35,37,38].

In the year 2000, the average global life expectancy was 63.8 years for men and 68 years for women [37]. For comparison, in research conducted by [39] for 35 selected countries worldwide, it was 71.6 years for the whole population in 2010. In the first half of 2020, the average life expectancy in the USA was 77.8; in Spain, it was 79.9. Over the years, there has been a continuous increase in life expectancy, particularly in highly developed countries [40], leading to the emergence of multi-generational cities [41]. For the first time in history, five generations live at once. Houses and cities have to be reinvented [42]. This rapid trend was disrupted by the outbreak of the COVID-19 pandemic [43]. According to research [44,45], this increased life expectancy resulted from a higher quality of life, which, in turn, stemmed from better economic conditions and social care by the state. Therefore, it is crucial that the control group in research includes ageing people from highly developed countries, where the material status of older adults is at a medium or higher level, so that economic factors do not limit their needs.

Based on a literature review regarding older adults, it can be summarised that many factors influence life expectancy. One of the key factors is the quality of life. Most older people rate this quality positively. Life satisfaction is often described using the shape of the letter U. In the first part of life, it is at its best, then deteriorates due to the accumulation of professional duties. It then improves in connection with retirement and an increase in free time for personal development and pursuits. Humanity is becoming accustomed to longevity despite the many inconveniences of old age (e.g., dementia, depression, loss of physical agility, chronic diseases). However, this model was more visible in the population of the 1950s. Recent studies confirmed that this model holds for other primates, and the human population is slowly moving away from these assumptions. The reason for this is the apparent deterioration of health with age despite medical advancements [46,47].

Mental health status, which can be defined as well-being, is also a very important issue and is one of the fundamental goals of the WHO. Well-being can have an impact on improving health, increasing the joy of life, and improving overall physical condition [46,48,49]. Some studies indicate that mental well-being is an important health protective factor, reducing the risk of chronic diseases and promoting longevity [50,51]. Chronic diseases are particularly dangerous for older citizens [52]. An antidote to chronic diseases is increased physical activity. It is associated with lower mortality rates among those affected by serious chronic diseases and can also prevent depressive states [53,54].

In light of the above considerations, it is essential that elements of age-friendly recreational areas (AFRAs) encourage older adults to engage in physical activity. This should be established during the survey study.

3. Materials and Methods

3.1. Survey Coverage

A survey in form of a questionnaire was conducted from October 2021 to April 2022 in a paper format (Poland 54%) and electronically (Germany, United Kingdom, United States, Canada, Croatia, Italy, Lithuania, and Slovakia—in total, 46%) among a group of 1815 older adults. It was conducted among older people according to an age structure based on [2]: pre-old age 55–59 (pre-senior), early old age 60/65–74 (young old), old age proper 75–89 (old old), and oldest old 90+ (oldest old lifelong). The survey was primarily conducted among citizens of cities with more than 150,000 inhabitants. Large cities have a more varied landscape and functionality, which can be classified according to the proposed AFRA methodology.

The selection of the random research sample took into account the wealth level of the countries (Table 2).

Table 2.

Basic economic data from the countries covered in the study. Source: own elaboration on the basis of * [55], ** [56], and *** [57].

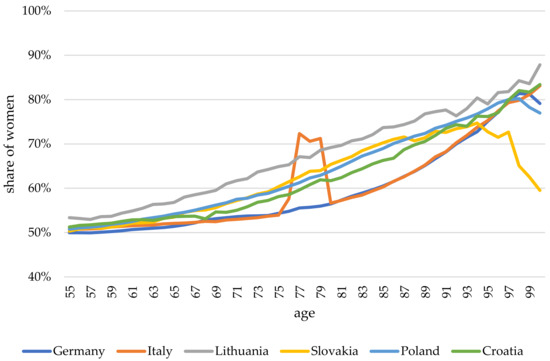

The selected countries vary in terms of their well-being indices and wealth levels. However, they can be classified as developed or wealthy countries according to statistical data. Depending on the age of older citizens in these countries, situations are observed where the number of women exceeds the number of men in certain age groups (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Share of women in the older population in the studied countries. Source: own elaboration on the basis of [58].

The research sample, consisting of over 70% women, aligns with statistics regarding the proportion of women in the older population in the studied countries. Additionally, women showed greater participation in filling out the surveys.

3.2. Study Framework

During this 3-year (2020–2023) scientific project funded by the National Science Centre in Poland, empirical qualitative and quantitative research was conducted.

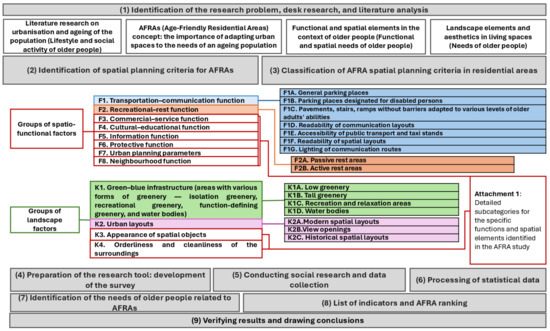

The research began with defining the research problem and conducting a literature review on urbanisation and ageing, with a particular focus on the needs of older people. Criteria for older adults in AFRAs were then identified and grouped into functional–spatial and landscape factors (Table A1 and Table A3). The next step involved developing a survey to collect data from older people about their needs. The collected data were then statistically analysed, and based on this analysis, a list of indicators was created, and a ranking of AFRAs was conducted. The final stage involved verifying the results and formulating conclusions (Figure 2).

Figure 2.

Research framework. Source: own elaboration.

3.3. Classification of Spatio-Functional Arrangements of Residential Public Open Spaces

In the research process, one critical step was the classification of spatio-functional arrangements in residential public open spaces, focusing on factors that influence the quality of life of the older population within urban environments (Table 3). This classification involved identifying key functions and organising them into spatio-functional and landscape categories, as detailed in Table A1 and Table A3.

Table 3.

Classification of spatio-functional arrangements of residential public open spaces. Source: own elaboration.

3.4. Classification of Landscape Arrangement Factors of Residential Public Open Spaces

The next step involved classifying the factors influencing the evaluation of landscapes in public spaces within older people’s residential areas (Table 4). This classification identified specific landscape features, which are detailed in Table A3.

Table 4.

Classification of landscape arrangement factors of residential public open spaces. Source: own elaboration.

3.5. Survey

The next stage involved developing a survey with open-ended questions based on the previously identified key functional–spatial and landscape factors. The aim of the survey was to gather data on older people’s preferences regarding AFRAs. Pilot studies were conducted among 31 older adults participating in the University of the Third Age in Olsztyn.

To study preferences in the context of different age groups of older adults and their activity levels, the survey included demographic questions regarding gender, age, professional or educational activity, type of residence, country of residence, city, and neighbourhood.

In the subsequent questions, respondents were asked to evaluate the extent to which functionality and aesthetics contribute to the quality of their lives in residential estates (on a 5-point scale, from unimportant to very important). Some questions included more detailed explanations, as follows:

- –

- F1D Readability of communication layouts—“Signposts, signs, information boards, banners, and other markings”;

- –

- F1F Readability of spatial layouts—“Easy orientation in space”;

- –

- F2B Active rest areas—“Outdoor gyms, swimming pools, sports clubs”;

- –

- F8A Neighbourhood function—“Presence of noise-generating or problematic areas”;

- –

- K2B View openings—“Open layouts providing views of the surroundings”;

- –

- K3C Harmonious accompanying infrastructure—“Benches, playgrounds, fountains, monuments”;

- –

- K3D Landscape dominant elements—“Presence of landscape elements aiding orientation (e.g., church tower, tall building, old tree)”.

As a result of the conducted surveys, 1852 responses were collected, of which 37 were rejected as incomplete. Following this verification, 1815 surveys qualified for further analysis.

3.6. Respondents

According to the methodological random sample requirements, it was established that participants from Poland should constitute approximately 50% of the respondents, with an even distribution of responses from five geographical regions of Poland (Gdańsk, Kraków, Poznań, Olsztyn, and Warsaw). Additionally, at least 100 responses were required from each of the other countries of comparison, which together were to make up the remaining 50% of responses from outside Poland. The requirement of at least 100 participants from each comparison country was achieved despite the COVID-19 pandemic. Due to the insufficient number of responses from the wealthiest countries in Asia, South America, Africa, and Australia, these regions were not included, representing an area for further research. The difficulties in conducting research in other parts of the world were due to the pandemic, the English-language survey, and the exclusively electronic format of the research. In Poland, the survey was distributed with the assistance of deputy mayors responsible for pro-ageing policy, while abroad, it was conducted online with the help of older adults’ associations and through the “snowball sampling” method, where participants recruited others. The comparison group consisted of older citizens from countries with high economic development indices, under the assumption that better financial conditions and older adult care might lead to more demanding AFRA criteria. The snowball sampling method can have several significant issues. Participants recruit people from their social circles, which may result in limited diversity of the sample and reduced representativeness. Additionally, respondents from countries other than Poland filled out the survey in English, which could have been challenging if it was not their native language.

3.7. Processing Statistical Data and Developing Rankings and Indicator List

As part of the analysis of the indicators collected through the survey, a method based on weighted calculations on a 5-point scale was adopted. The aim of this stage was to determine the relative importance of each indicator in assessing AFRAs according to the needs of older adults. The analysis process involved several key steps. Each indicator was evaluated on a 5-point scale, where responses were assigned weights corresponding to their values (from 1 to 5). For indicator i, the weighted average score was calculated using the following formula:

where

- —number of responses for score (ranging from 1 to 5) for indicator ;

- —weight assigned to scale value (on a 5-point scale ).

This formula allows for calculating an average score that takes into account both the number of responses and the value assigned to each response on the scale.

After the average scores were calculated for each indicator, a ranking of the indicators was conducted based on the obtained values. The indicators were ordered according to their average scores, with a higher average score indicating a higher rank in the ranking.

Here,

- —ranking of the -th indicator,

- —position of indicator in the ranking based on its average rating.

4. Results

4.1. Analysis of the Respondents’ Demography

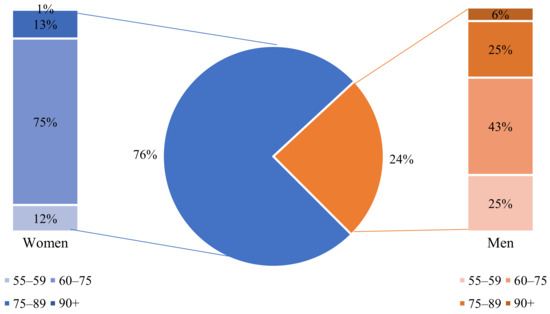

The questionnaire survey was conducted on a population sample of 1815 respondents, 76% of which were women. The age structure of the population sample was as follows: 55–59—15%, 60–75—67%, 76+—18%. Most of the female (75%) and male (43%) respondents belonged to the young old group (60–75) (Figure 3).

Figure 3.

Age and gender of the surveyed pre-seniors and older people. Source: own elaboration.

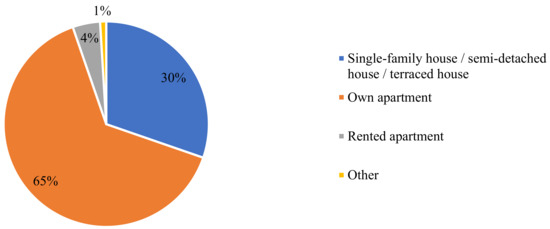

In all, 67% of the surveyed older adults inhabited apartments, while 32% lived in single-family homes, semi-detached houses, or terraced houses (Figure 4).

Figure 4.

Types of dwellings occupied by the respondents. Source: own elaboration.

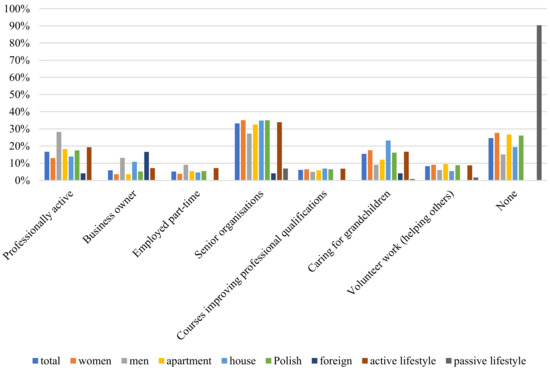

When asked about their daily activities, most older adults declared that they belonged to older peoples’ organisations (such as the University of the Third Age) (28%), followed by those who were not professionally active and were not enrolled in educational programs (21%). In the surveyed group, 15% of the respondents were professionally active, and 13% were taking care of their grandchildren. Only 7% of the older adults worked as volunteers, and 5% attended courses to improve their professional qualifications, were part-time employees, or were business owners (Figure 5). These responses do not total 100% because the respondents were allowed to select more than one answer.

Figure 5.

Daily life activities of the surveyed pre-seniors and older people. Source: own elaboration.

The majority of female respondents were members of organisations for older people (35%) and were not engaged in any professional or educational activities (28%). Very few of the retired women owned businesses or were employed part-time (4% and 5%, respectively). Conversely, most male respondents were professionally active (29%) or belonged to organisations for older people (28%), while the smallest proportions of retired men were improving their professional qualifications (6%) or were involved in volunteer work (6%).

Similarly, older residents living in flats and houses also varied in the types of daily activities they undertook. The most popular answer for both groups was membership in older peoples’ organisations (33% and 36%, respectively). The second most common response among apartment dwellers was not being engaged in any type of professional or educational activity (27%); among house dwellers, it was taking care of their grandchildren (23%).

When it comes to the country of origin, Polish older adults were mostly involved in older peoples’ organisations (35%) or not involved in any type of professional or educational activity (26%), whereas most of the non-Polish respondents declared being business owners (29%). Contrarily, being employed full-time or part-time (21% among non-Polish respondents) was the least frequently chosen answer by Polish older adults (5%).

Generally speaking, the studied group of older adults consisted of 74% leading an active lifestyle and 26% preferring a home-centred (passive) style. Therefore, this study was primarily dedicated to older adults actively participating in social life, as it is difficult to reach home-centred older adults with surveys. Consequently, there is no possibility of adapting the elements of spatial development to their needs, as this social group very rarely makes use of them.

4.2. Hierarchy of Factors Contributing to Age-Friendliness of Residential Public Open Spaces

In subsequent questions, respondents were asked to assess how much functionality and aesthetics enhance their quality of life in residential estates. For each factor, the arithmetic mean of the relevance identified by the respondents in the survey was calculated. Then, a hierarchy of factors influencing age-friendliness was determined. The older people’s perceptions of the elements described in the previous section are presented in Table 5 and Table 6.

Table 5.

Hierarchy of selected functionality factors that contribute to age-friendliness of residential public open spaces. Source: own elaboration.

Table 6.

Hierarchy of selected aesthetic factors that contribute to age-friendliness of residential public open spaces. Source: own elaboration.

In the group of functionality factors, the highest ranks were assigned to locations where basic necessities can be purchased (such as grocery stores, department stores, and pharmacies) and primary healthcare facilities. Elements such as the lighting of communication routes; pavements, stairs, and ramps without barriers adapted to various levels of older adults’ abilities; and the accessibility of public transport adapted to various levels of ability are also important. A level of at least 4 on a 5-point scale was also assigned to cemeteries, restaurants, and walking areas (parks, squares, green spaces). The lowest in the ranking were components such as parking places designated for disabled persons, chapels and other elements of small sacred architecture, or protective infrastructure.

According to the respondents, the most important aesthetic components are walking paths, avenues, park layouts, green spaces, squares, low and tall greenery, and spatial layouts of historical heritage. These older adults also pay great attention to objects and elements that harm the aesthetic values of the landscape. The least important components are sports facilities and playgrounds, view openings, and landscape dominant elements.

4.3. Ranking of Factors Contributing to Age-Friendliness of Residential Public Open Spaces

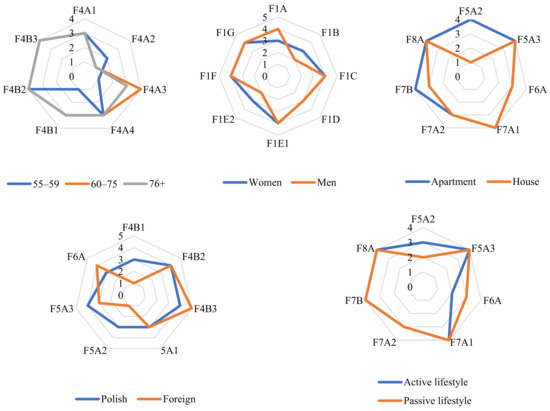

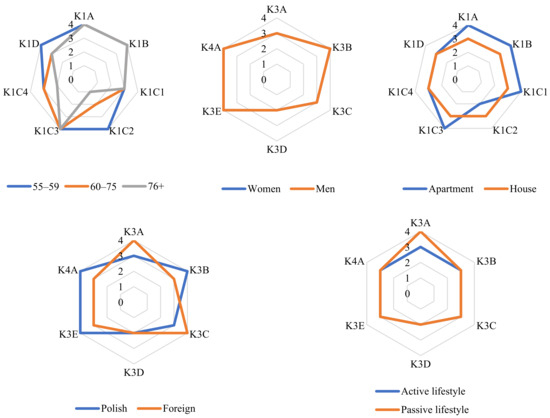

Afterwards, each factor in each category of components was ranked based on its perceived importance in the conducted survey. Cumulative frequency series and median values were used for the entire population sample. A similar comparison was then conducted regarding age, gender, accommodations, and country of origin of the surveyed older citizens, and their lifestyles in terms of activity (Table A2 and Table A4, Figure 6 and Figure 7).

Figure 6.

Ranks calculated for the analysed functionality components for different sub-groups of respondents and selected groups of factors. Source: own elaboration.

Figure 7.

Ranks calculated for the analysed aesthetic components for different sub-groups of respondents and selected groups of factors. Source: own elaboration.

For example, in different age groups, swimming pools were considered moderately important (3) for those aged 55–59, not very important for those aged 60–75 (2), and not important at all for those aged 76+ (1). Similar trends are noticeable in the context of other active recreation places; older age groups attach less importance to them than younger ones, probably due to their deteriorating health with age. For the older groups, cultural and educational facilities such as community clubs, cultural houses, and libraries are also more important, providing them with opportunities to meet other people, especially their peers.

In terms of gender differences, it was observed that women placed less importance on the presence of parking places but more on public transport. This could be because, in the analysed generational groups of older adults, women less frequently had a driving license compared to men. Furthermore, for women, cinemas, theatres, and libraries, as well as chapels and other elements of small sacred architecture, were more important.

Walking areas (squares, parks, green spaces) and biologically active areas are less important to those living in houses than to those residing in apartments, probably because the former take care of their own green areas within their properties. A similar situation applied to parking places, both in general and for disabled persons, for similar reasons. Additionally, for house residents, community clubs and libraries were less significant.

Moreover, non-Polish older adults rated swimming pools as important, while Polish ones rated them not important at all. Non-Polish older adults also considered gyms, department stores, and passive recreation places to be more important. On the other hand, libraries and pharmacies were less important to them. A more significant difference was seen in the case of museums and galleries: while Polish older adults rated them as moderately important, for their peers from other countries, they were not important at all. The same difference in ranking occurred in the case of chapels and the presence of auditory signals on the street.

The biggest differences between active and passive older adults were noticed in the case of chapels and other elements of small sacred architecture (important for active, unimportant for passive). Furthermore, the condition of pavements and stairs and the presence of benches and safe shelter places proved to be more important for the second group of respondents. In contrast, auditory signalling and the activities of security and public services were less important for inactive older adults.

Regarding aesthetic components, there were decidedly fewer differences. Water bodies turned out to be slightly more important for the youngest group of older adults. This group, along with the oldest group (76+), also placed greater importance on well-maintained building façades. On the other hand, those aged 55–59 did not consider objects that harm the aesthetic value of the landscape as being important, unlike the assessments of the other age groups.

In terms of gender differences, differences were only obtained in terms of well-maintained façades, being important for women but moderately important for men. Apartment dwellers rated low and tall greenery and parks as being more important in aesthetic matters. Well-maintained building façades and spatial layouts of historical heritage also had greater significance for them. Conversely, harmonious architecture, which was moderately important for older citizens living in apartments, was not important at all for house dwellers. Differences between Polish and non-Polish older adults were visible for benches and resting places, water bodies, and well-maintained building façades—they were rated higher by the non-Polish respondents. Older adults leading a passive lifestyle rated tall greenery and spatial layouts of historical heritage lower than the rest (as important), while benches and resting places and well-maintained building façades were rated higher than most of the studied group (important).

Generally speaking, in the group of functionality factors, the highest ranks were assigned to group 8 (Neighbourhood function) and group 3 (Commercial–service function), and the lowest were assigned to group 7 (Protective function) and group 2 (Recreational–rest function). Aesthetic factors received the highest ranks in group 2 (Urban layouts) and the lowest in group 3 (Appearance of spatial objects). Differences in preferences can arise from various factors, primarily including health status, technological developments and the ability to use them, wealth, and cultural heritage.

5. Discussion

The research results show that older citizens particularly value the proximity of commercial and service facilities (among functional–spatial factors), which aligns with previous studies [15,16], and walking areas (among landscape factors), which confirms the findings of [14,21]. Additionally, in this study, proximity to sacred sites and neighbourhood functions, which had not been prioritised in previous scientific research, were ranked highly.

No significant differences were observed in AFRA preferences related to gender or the type of housing (multi-family/single-family). In individual cases, there were differences of just one rank point. Similarly, only minor differences were found concerning age groups, with pre-seniors and younger seniors generally rating active recreational spaces higher and passive spaces lower, which aligns with the theory of reminiscence [108,109]. Slightly larger differences in AFRA preferences appeared between Polish and non-Polish respondents, most often due to cultural habits. This leads to the general conclusion that the study of needs and preferences should be conducted at the national level. Slightly greater differences also emerged between individuals who preferred an active lifestyle and those with lower activity levels. Considering the results of numerous scientific studies, it is important to stimulate the activity of older adults to maintain or improve their physical and mental health. Therefore, AFRA preferences should be carefully considered, with an emphasis on functional solutions that encourage activity. Such research is planned to be conducted in the near future.

Most of the participants were individuals leading an active lifestyle, due to the difficulty in accessing those with lower activity levels (only 26% of respondents). Therefore, future studies should expand the random sample to include more people with lower activity levels to ensure that the results are fully representative of the older population, taking into account different lifestyles.

Due to the nature of the survey and the method of distribution (snowball sampling), it was mainly filled out by older, educated individuals who spoke English (which may be relatively rare in this age group in many countries). This can be considered an advantage of the results, as such individuals often act as “role models” in their local communities.

Another limitation would be the size of the analysed cities. Older people in smaller towns may not have access to or are not aware of the facilities presented in the proposed methodology, which would affect how they perceive their residential estates. That is why the recommendations stemming from research results should reflect not only the existing tastes of older people but also the possible better alternatives. Even without the presence of such objects in a city, designers and policy-makers should not exclude such facilities from their urban planning.

The conducted study made it possible to identify AFRA development elements divided into five levels of importance, based on responses from 1815 respondents from nine countries. The developed list of AFRA elements includes five groups in the functional–spatial category, with a total of 33 elements, and four groups in the landscape values category, with 16 elements. All of the established development elements can be identified using publicly available spatial data.

This comprehensive approach to AFRA assessment allows for the establishment of priorities in both sustainable spatial development policy for residential areas and pro-ageing policies.

It is recommended that similar studies be conducted in countries with lower levels of development to compare the results, although it should be noted that access to data may be more challenging. The results obtained could help avoid the repetition of spatial planning mistakes in developing countries.

6. Conclusions

In summary, the minor differences in the prioritisation of functional–spatial and landscape indicators allowed for the standardisation of the results. The developed AFRA element list represents a complete set of preferences for countries with high economic development. By adopting the developed methodology, it is possible to determine the ranks of individual AFRA elements for any country, regardless of its level of wealth.

An important issue remains the comparative analysis of AFRA preferences in different countries, which could help identify similarities and differences between various cultures and geographical areas and highlight similar clusters. This is another planned task in the project.

The overall results from this study confirmed global observations that an individual’s lifestyle is largely determined by their economic wealth, which, in turn, influences their life needs. The research also revealed that specific AFRA landscape features affecting the aesthetics of residential areas are important. Older adults want to live in green, harmonious spaces and enjoy contemplating the landscape.

Author Contributions

Conceptualisation, A.S., M.C., M.D. and A.D.; methodology, A.S., M.C., M.D. and A.D.; software, M.C.; validation, A.S., M.C., M.D. and A.D.; formal analysis, A.S., M.C., M.D. and A.D.; investigation, A.S., M.C., M.D. and A.D.; resources, A.S., M.C., M.D. and A.D.; data curation, M.C.; writing—original draft preparation, A.S., M.C., M.D. and A.D.; writing—review and editing, A.S., M.C., M.D. and A.D.; visualisation, M.C.; supervision, A.D.; project administration, A.D.; funding acquisition, A.S., M.C., M.D. and A.D. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded in whole by National Science Centre, Poland [2019/35/B/HS4/01380]. Project title: The concept of identifying age-friendly housing estates in the aspect of infrastructural and landscape determinants.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement

Dataset available on request from the authors.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Appendix A

Table A1.

Categories of functionality factors. Source: own elaboration.

Table A1.

Categories of functionality factors. Source: own elaboration.

| Code | Category of Factors | Factors |

|---|---|---|

| F1A | General parking places |

|

| F1B | Parking places designated for disabled persons |

|

| F1C | Pavements, stairs, and ramps without barriers adapted to various levels of older adults’ abilities |

|

| F1D | Readability of communication layouts |

|

| F1E | Accessibility of public transport and taxi stands |

|

| F1F | Readability of spatial layouts |

|

| F1G | Lighting of communication routes |

|

| F2A | Passive rest areas |

|

| F2B | Active rest areas |

|

| F3A | Primary healthcare locations |

|

| F3B | Places to purchase basic necessities |

|

| F3C | Restaurants/bars |

|

| F3D | Security and public services (response speed and ability for personal and telephone contact) |

|

| F3E | Public toilets and cleanliness of the estate |

|

| F4A | Cultural–educational facilities |

|

| F4B | Sacred facilities |

|

| F5A | Clear signage adapted to the abilities of older adults |

|

| F6A | Places of safe shelter and infrastructure elements providing safety in emergency situations (e.g., shelters, flood protection, evacuation points) |

|

| F7A | Building intensity |

|

| F7B | Biologically active area |

|

| F8A | Neighbourhood function (function of land adjacent to the estate) |

|

Table A2.

Ranks calculated for the analysed functionality factors. Source: own elaboration.

Table A2.

Ranks calculated for the analysed functionality factors. Source: own elaboration.

| Category | Rank | 55–59 | 60–75 | 76+ | Women | Men | Flat | House | Polish | Non-Polish | Active Lifestyle | Passive Lifestyle |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| F1A | 4 | 4 | 4 | 4 | 3 | 4 | 4 | 3 | 4 | 4 | 4 | 4 |

| F1B | 2 | 3 | 3 | 2 | 3 | 2 | 3 | 2 | 2 | 3 | 2 | 3 |

| F1C | 4 | 4 | 4 | 4 | 4 | 4 | 4 | 4 | 4 | 4 | 4 | 4 |

| F1D | 3 | 3 | 3 | 3 | 3 | 3 | 3 | 3 | 3 | 3 | 3 | 3 |

| F1E1 | 4 | 4 | 4 | 4 | 4 | 4 | 4 | 4 | 4 | 4 | 4 | 4 |

| F1E2 | 3 | 3 | 3 | 3 | 3 | 2 | 3 | 3 | 3 | 2 | 3 | 3 |

| F1F | 4 | 4 | 4 | 4 | 4 | 4 | 4 | 4 | 4 | 4 | 4 | 4 |

| F1G | 4 | 4 | 4 | 4 | 4 | 4 | 4 | 4 | 4 | 4 | 4 | 4 |

| F2A1 | 3 | 3 | 3 | 3 | 3 | 3 | 4 | 3 | 3 | 4 | 3 | 4 |

| F2A2 | 4 | 4 | 4 | 4 | 4 | 4 | 4 | 3 | 4 | 4 | 4 | 4 |

| F2B | 3 | 3 | 3 | 2 | 3 | 3 | 3 | 3 | 3 | 3 | 3 | 3 |

| F3A | 4 | 4 | 4 | 4 | 4 | 4 | 4 | 4 | 4 | 4 | 4 | 4 |

| F3B1 | 4 | 4 | 4 | 4 | 4 | 4 | 4 | 4 | 4 | 4 | 4 | 4 |

| F3B2 | 4 | 4 | 4 | 4 | 4 | 4 | 4 | 4 | 4 | 5 | 4 | 4 |

| F3B3 | 4 | 4 | 4 | 4 | 4 | 4 | 4 | 4 | 4 | 3 | 4 | 4 |

| F3C | 4 | 4 | 4 | 4 | 4 | 4 | 4 | 4 | 4 | 4 | 4 | 4 |

| F3D | 3 | 3 | 3 | 3 | 3 | 3 | 3 | 3 | 3 | 3 | 3 | 2 |

| F3E | 3 | 3 | 3 | 3 | 3 | 3 | 3 | 3 | 3 | 3 | 3 | 3 |

| F4A1 | 3 | 2 | 3 | 3 | 3 | 3 | 3 | 2 | 3 | 3 | 3 | 3 |

| F4A2 | 4 | 1 | 4 | 3 | 4 | 3 | 4 | 3 | 4 | 3 | 4 | 4 |

| F4A3 | 3 | 3 | 3 | 3 | 3 | 3 | 3 | 3 | 3 | 1 | 3 | 3 |

| F4A4 | 3 | 3 | 4 | 3 | 4 | 3 | 3 | 3 | 3 | 3 | 3 | 3 |

| F4B1 | 4 | 4 | 4 | 4 | 4 | 4 | 4 | 4 | 4 | 4 | 4 | 4 |

| F4B2 | 3 | 1 | 3 | 3 | 3 | 1 | 3 | 3 | 3 | 1 | 3 | 1 |

| F4B3 | 4 | 4 | 4 | 4 | 4 | 4 | 4 | 4 | 4 | 4 | 4 | 4 |

| F5A2 | 3 | 3 | 3 | 3 | 3 | 3 | 3 | 2 | 3 | 1 | 3 | 2 |

| F5A3 | 4 | 4 | 4 | 4 | 4 | 4 | 4 | 4 | 4 | 3 | 4 | 4 |

| F6A | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 3 |

| F7A1 | 4 | 4 | 4 | 4 | 4 | 4 | 4 | 4 | 4 | 4 | 4 | 4 |

| F7A2 | 3 | 3 | 3 | 3 | 3 | 3 | 3 | 3 | 3 | 3 | 3 | 3 |

| F7B | 4 | 4 | 4 | 4 | 4 | 4 | 4 | 3 | 4 | 4 | 4 | 4 |

| F8A | 4 | 4 | 4 | 4 | 4 | 4 | 4 | 4 | 4 | 4 | 4 | 4 |

green—rank higher than the average one; red—rank lower than the average one.

Appendix B

Table A3.

Categories of aesthetic factors. Source: own elaboration.

Table A3.

Categories of aesthetic factors. Source: own elaboration.

| Code | Category of Factors | Factors |

|---|---|---|

| K1A | Low greenery |

|

| K1B | Tall greenery |

|

| K1C | Recreation and relaxation areas |

|

| K1D | Water bodies |

|

| K2A | Modern spatial layouts |

|

| K2B | View openings |

|

| K2C | Spatial layouts of historical heritage |

|

| K3A | Façades of buildings and other construction objects |

|

| K3B | Harmonious architecture |

|

| K3C | Harmonious accompanying infrastructure |

|

| K3D | Landscape dominant elements |

|

| K3E | Objects and elements reducing the aesthetic values of the landscape |

|

| K4A | Well-maintained and clean estate elements |

|

Table A4.

Ranks calculated for the analysed aesthetic factors. Source: own elaboration.

Table A4.

Ranks calculated for the analysed aesthetic factors. Source: own elaboration.

| Category | Rank | 55–59 | 60–75 | 76+ | Women | Men | Flat | House | Polish | Non-Polish | Active Lifestyle | Passive Lifestyle |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| K1A | 4 | 4 | 4 | 4 | 4 | 4 | 4 | 3 | 4 | 4 | 4 | 4 |

| K1B | 4 | 4 | 4 | 4 | 4 | 4 | 4 | 3 | 4 | 4 | 4 | 3 |

| K1C1 | 3 | 3 | 3 | 3 | 3 | 3 | 4 | 3 | 3 | 4 | 3 | 4 |

| K1C2 | 4 | 4 | 4 | 4 | 4 | 4 | 4 | 4 | 4 | 4 | 4 | 4 |

| K1C3 | 4 | 4 | 4 | 4 | 4 | 4 | 4 | 3 | 4 | 4 | 4 | 4 |

| K1C4 | 3 | 3 | 3 | 2 | 3 | 3 | 3 | 3 | 3 | 3 | 3 | 3 |

| K1D | 3 | 4 | 3 | 3 | 3 | 3 | 3 | 3 | 3 | 4 | 3 | 3 |

| K2A | 3 | 3 | 3 | 3 | 3 | 3 | 3 | 3 | 3 | 3 | 3 | 3 |

| K2B | 4 | 4 | 4 | 4 | 4 | 4 | 4 | 4 | 4 | 4 | 4 | 4 |

| K2C | 4 | 4 | 4 | 4 | 4 | 4 | 4 | 3 | 4 | 4 | 4 | 3 |

| K3A | 3 | 4 | 3 | 4 | 4 | 3 | 4 | 3 | 3 | 4 | 3 | 4 |

| K3B | 3 | 3 | 3 | 3 | 3 | 3 | 3 | 1 | 3 | 3 | 3 | 3 |

| K3C | 3 | 4 | 3 | 3 | 3 | 3 | 3 | 3 | 3 | 4 | 3 | 3 |

| K3D | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 |

| K3E | 3 | 1 | 3 | 3 | 3 | 3 | 3 | 3 | 3 | 3 | 3 | 3 |

| K4A | 3 | 3 | 3 | 3 | 3 | 3 | 3 | 3 | 3 | 3 | 3 | 3 |

green—rank higher than the average one; red—rank lower than the average one.

References

- Sun, Y.; Ng, M.K.; Chao, T.-Y.S. Age-Friendly Urbanism: Intertwining “ageing in Place” and “Place in Ageing”. Town Plan. Rev. 2020, 91, 601–619. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- WHO. Global Age-Friendly Cities: A Guide; WHO: Geneva, Switzerland, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- WHO. Measuring the Age-Friendliness of Cities: A Guide to Using Core Indicators. A Guide to Using Core Indicators; WHO: Geneva, Switzerland, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- WHO. World Report on Ageing and Health; WHO: Geneva, Switzerland, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Gronostajska, B. Kształtowanie Środowiska Mieszkaniowego Dla Seniorów [Shaping the Housing Environment for Older People]; Oficyna Wydawnicza PWr: Wrocław, Poland, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Zhai, Y.; Li, K.; Liu, J. A Conceptual Guideline to Age-Friendly Outdoor Space Development in China: How Do Chinese Seniors Use the Urban Comprehensive Park? A Focus on Time, Place, and Activities. Sustainability 2018, 10, 3678. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Finlay, J.; Franke, T.; McKay, H.; Sims-Gould, J. Therapeutic Landscapes and Wellbeing in Later Life: Impacts of Blue and Green Spaces for Older Adults. Health Place 2015, 34, 97–106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ibrahim, N.K.; Abbawi, R.F.N. The Role of Landscape in Achieving (Ageing in Place) within Multi-Story Housing Projects. In Proceedings of the IOP Conference Series: Materials Science and Engineering; IOP Publishing: Bristol, UK, 2020; Volume 881, p. 012022. [Google Scholar]

- Wolny, A.; Dawidowicz, A.; Źróbek, R. Identification of the Spatial Causes of Urban Sprawl with the Use of Land Information Systems and GIS Tools. Bull. Geogr. Socio-Econ. Ser. 2017, 35, 111–122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gentile, M.; Tammaru, T.; Van Kempen, R. Heteropolitanization: Social and Spatial Change in Central and East European Cities. Cities 2012, 29, 291–299. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Murzyn, M.A. Heritage Transformation in Central and Eastern Europe. In The Routledge Research Companion to Heritage and Identity; Routledge: Milton Park, UK, 2016; pp. 315–346. [Google Scholar]

- Dawidowicz, A.; Dudzińska, M. The Potential of GIS Tools for Diagnosing the SFS of Multi-Family Housing towards Friendly Cities—A Case Study of the EU Member State of Poland. Sustainability 2022, 14, 6642. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Śleszyński, P. Społeczno-Ekonomiczne Skutki Chaosu Przestrzennego Dla Osadnictwa i Struktury Funkcjonalnej Terenów [Socio-Economic Effects of Spatial Chaos on Settlement and the Functional Structure of Land]; Studia KPZK: Warsaw, Poland, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Xu, T.; Nordin, N.A.; Aini, A.M. Urban Green Space and Subjective Well-Being of Older People: A Systematic Literature Review. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 19, 14227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wahl, H.W.; Oswald, F. Environmental Perspectives on Aging. In The SAGE Handbook of Social Gerontology; Dannefer, D., Phillipson, C., Eds.; SAGE: Newcastle upon Tyne, UK, 2010; pp. 111–124. [Google Scholar]

- Buffel, T.; Phillipson, C.; Scharf, T. Ageing in Urban Environments: Developing ‘Age-Friendly’ Cities. Crit. Soc. Policy 2012, 32, 597–617. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Phillipson, C. The ‘Elected’ and the ‘Excluded’: Sociological Perspectives on the Experience of Place and Community in Old Age. Ageing Soc. 2007, 27, 321–342. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gitlin, L.N. Conducting Research on Home Environments: Lessons Learned and New Directions. Gerontologist 2003, 43, 628–637. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Plouffe, L.; Kalache, A. Towards Global Age-Friendly Cities: Determining Urban Features That Promote Active Aging. J. Urban Health 2010, 87, 733–739. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Carmona, M. Re-Theorising Contemporary Public Space: A New Narrative and a New Normative. J. Urban. Int. Res. Placemaking Urban Sustain. 2015, 8, 373–405. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sugiyama, T.; Thompson, C.W.; Alves, S. Associations Between Neighborhood Open Space Attributes and Quality of Life for Older People in Britain. Environ. Behav. 2009, 41, 3–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van Hees, S.; Horstman, K.; Jansen, M.; Ruwaard, D. Photovoicing the Neighbourhood: Understanding the Situated Meaning of Intangible Places for Ageing-in-Place. Health Place 2017, 48, 11–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moran, M.; Van Cauwenberg, J.; Hercky-Linnewiel, R.; Cerin, E.; Deforche, B.; Plaut, P. Understanding the Relationships between the Physical Environment and Physical Activity in Older Adults: A Systematic Review of Qualitative Studies. Int. J. Behav. Nutr. Phys. Act. 2014, 11, 79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Douglas, O.; Lennon, M.; Scott, M. Green Space Benefits for Health and Well-Being: A Life-Course Approach for Urban Planning, Design and Management. Cities 2017, 66, 53–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yeo, N.L.; Elliott, L.R.; Bethel, A.; White, M.P.; Dean, S.G.; Garside, R. Indoor Nature Interventions for Health and Wellbeing of Older Adults in Residential Settings: A Systematic Review. Gerontologist 2020, 60, e184–e199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kearney, A.R. Residential Development Patterns and Neighborhood Satisfaction. Environ. Behav. 2006, 38, 112–139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matsuoka, R.H.; Kaplan, R. People Needs in the Urban Landscape: Analysis of Landscape and Urban Planning Contributions. Landsc. Urban Plan. 2008, 84, 7–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chabior, A. Aktywizacja i Aktywność Ludzi w Okresie Późnej Dorosłości [Active and Active People in Late Adulthood]; Wszechnica Świętokrzyska: Kielce, Poland, 2011; ISBN 8362718080. [Google Scholar]

- Punyakaew, A.; Lersilp, S.; Putthinoi, S. Active Ageing Level and Time Use of Elderly Persons in a Thai Suburban Community. Occup. Ther. Int. 2019, 2019, 7092695. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gorgol, J. Czas Wolny w Perspektywie Rozwoju Nowoczesnych Technologii [Spare Time in the Perspective of Development of Modern Technology]. In Kultura Czasu Wolnego We Współczesnym Świecie [Leisure culture in the modern world]; Tanaś, V., Welskop, W., Eds.; Wydawnictwo Naukowe Wyższej Szkoły Biznesu i Nauk o Zdrowiu: Łódź, Poland, 2016; pp. 225–231. ISBN 978-83-940080-7-9. [Google Scholar]

- Rzepko, M.; Drozd, M.; Drozd, S.; Bajorek, W.; Kunysz, P. Uczestnictwo w Turystyce i Rekreacji Ruchowej Osób Starszych—Mieszkańców Rzeszowa [Participation in Tourism and Physical Recreation for Senior Citizens—Residents of Rzeszów]. Handel Wewnętrzny 2017, 4, 206–219. [Google Scholar]

- Sawińska, A. Seniorzy i Preseniorzy Jako Perspektywiczny Podmiot Rynku Turystycznego i Rekreacyjnego [Seniors and Preseniors as a Prospective Player in the Tourism and Leisure Market]. Rozpr. Nauk. Akad. Wych. Fiz. We Wrocławiu 2014, 46, 171–177. [Google Scholar]

- Kunst, A.E.; Groenhof, F.; Mackenbach, J.P. Mortality by Occupational Class among Men 30–64years in 11 European Countries. Soc. Sci. Med. 1998, 46, 1459–1476. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Townsend, P.; Whitehead, M.; Davidson, N. Introduction to Inequalities in Health. In Welfare and the State: Critical Concepts in Political Science; Deakin, N., Jones-Finer, C., Matthews, B., Eds.; Penguin: London, UK, 1992; Volume II, pp. 1–27. [Google Scholar]

- Wilkinson, R.G.; Marmot, M. Social Determinants of Health: The Solid Facts; World Health Organization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2003; ISBN 9289013710. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, L.-Y.; Feng, M.; Hu, X.-Y.; Tang, M.-L. Association of Daily Health Behavior and Activity of Daily Living in Older Adults in China. Sci. Rep. 2023, 13, 19484. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smits, J.; Monden, C. Length of Life Inequality around the Globe. Soc. Sci. Med. 2009, 68, 1114–1123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Goesling, B.; Firebaugh, G. The Trend in International Health Inequality. Popul. Dev. Rev. 2004, 30, 131–146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muszyńska, M.; Janssen, F. The Concept of the Equivalent Length of Life for Quantifying Differences in Age-at-Death Distributions across Countries. Genus 2016, 72, 6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arias, E.; Tejada-Vera, B.; Kochanek, K.D.; Ahmad, F.B. Provisional Life Expectancy Estimates for January through June, 2020; Vital Statistics Rapid Release 10; U.S. Department of Health and Human Services: Washington, DC, USA, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Buzalska, M. Raport Szczęśliwy Dom: Mieszkanie Na Osi Czasu [Happy Home Report: Housing on the Timeline]. Available online: https://www.otodom.pl/wiadomosci/pobierz/raporty/raport-szczesliwy-dom-mieszkanie-na-osi-czasu (accessed on 23 August 2024).

- Waloch, N. Architektka: Pierwszy Raz w Dziejach Żyje Pięć Pokoleń Naraz. Domy i Miasta Trzeba Wymyślić Od Nowa [Report: Five Generations at Once. Houses and Cities Have to Be Reinvented]. Available online: https://www.wysokieobcasy.pl/wysokie-obcasy/7,163229,31242767,architektka-pierwszy-raz-w-dziejach-zyje-piec-pokolen-naraz.html (accessed on 23 August 2024).

- Harper, S. The Impact of the Covid-19 Pandemic on Global Population Ageing. J. Popul. Ageing 2021, 14, 137–142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mackenbach, J.P.; Valverde, J.R.; Bopp, M.; Brønnum-Hansen, H.; Deboosere, P.; Kalediene, R.; Kovács, K.; Leinsalu, M.; Martikainen, P.; Menvielle, G.; et al. Determinants of Inequalities in Life Expectancy: An International Comparative Study of Eight Risk Factors. Lancet Public Health 2019, 4, e529–e537. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McMaughan, D.J.; Oloruntoba, O.; Smith, M.L. Socioeconomic Status and Access to Healthcare: Interrelated Drivers for Healthy Aging. Front. Public Health 2020, 8, 231. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Steptoe, A.; de Oliveira, C.; Demakakos, P.; Zaninotto, P. Enjoyment of Life and Declining Physical Function at Older Ages: A Longitudinal Cohort Study. Can. Med. Assoc. J. 2014, 186, E150–E156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Netuveli, G.; Blane, D. Quality of Life in Older Ages. Br. Med. Bull. 2008, 85, 113–126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Miret, M.; Caballero, F.F.; Olaya, B.; Koskinen, S.; Naidoo, N.; Tobiasz-Adamczyk, B.; Leonardi, M.; Haro, J.M.; Chatterji, S.; Ayuso-Mateos, J.L. Association of Experienced and Evaluative Well-Being with Health in Nine Countries with Different Income Levels: A Cross-Sectional Study. Global Health 2017, 13, 65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- World Health Organization. Mental Health Action Plan 2013–2020; WHO: Geneva, Switzerland, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Dolan, P.; White, M.P. How Can Measures of Subjective Well-Being Be Used to Inform Public Policy? Perspect. Psychol. Sci. 2007, 2, 71–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Steptoe, A.; Deaton, A.; Stone, A.A. Psychological Wellbeing, Health and Ageing. Lancet 2015, 385, 640. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roberts, K.C.; Rao, D.P.; Bennett, T.L.; Loukine, L.; Jayaraman, G.C. Prevalence and Patterns of Chronic Disease Multimorbidity and Associated Determinants in Canada. Health Promot. Chronic Dis. Prev. Can. 2015, 35, 87–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, G.; D’Arcy, C. Physical Activity and Social Support Mediate the Relationship between Chronic Diseases and Positive Mental Health in a National Sample of Community-Dwelling Canadians 65+: A Structural Equation Analysis. J. Affect. Disord. 2022, 298, 142–150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chekroud, S.R.; Gueorguieva, R.; Zheutlin, A.B.; Paulus, M.; Krumholz, H.M.; Krystal, J.H.; Chekroud, A.M. Association between Physical Exercise and Mental Health in 1· 2 Million Individuals in the USA between 2011 and 2015: A Cross-Sectional Study. Lancet Psychiatry 2018, 5, 739–746. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ventura, L. Richest Countries in the World 2024. Available online: https://gfmag.com/data/richest-countries-in-the-world/ (accessed on 23 August 2024).

- Ortiz-Ospina, E.; Roser, M. Happiness and Life Satisfaction. Self-Reported Life Satisfaction Differs Widely between People and between Countries. What Explains These Differences? Available online: https://ourworldindata.org/happiness-and-life-satisfaction (accessed on 20 September 2024).

- Business Insider. Gdzie Warto Pobierać Emeryturę? W Tych Krajach Żyje Się Najlepiej [Where Is It Worth Drawing a Pension? These Countries Have the Best Quality of Life]. Available online: https://businessinsider.com.pl/twoje-pieniadze/gdzie-warto-pobierac-emeryture-w-tych-krajach-zyje-sie-najlepiej/tmjtpr5 (accessed on 30 April 2023).

- Eurostat. Population by Age and Sex. Available online: https://ec.europa.eu/eurostat (accessed on 23 August 2024).

- Lu, W.; Zhang, C.; Ni, X.; Liu, H. Do the Elderly Need Wider Parking Spaces? Evidence from Experimental and Questionnaire Surveys. Sustainability 2020, 12, 3800. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leonardi, S.; Distefano, N.; Pulvirenti, G. Identification of Road Safety Measures for Elderly Pedestrians Based on K-Means Clustering and Hierarchical Cluster Analysis. Arch. Transp. 2020, 56, 107–118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wadu Mesthrige, J.; Cheung, S.L. Critical Evaluation of ‘Ageing in Place’ in Redeveloped Public Rental Housing Estates in Hong Kong. Ageing Soc. 2020, 40, 2006–2039. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Golbuff, L.; Aldred, R. Cycling Policy in the UK: A Historical and Thematic Overview; University of East London Sustainable Mobilities Research Group: London, UK, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Pucher, J.; Buehler, R. City Cycling; MIT Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 2012; ISBN 0262304996. [Google Scholar]

- Hjorthol, R. Transport Resources, Mobility and Unmet Transport Needs in Old Age. Ageing Soc. 2013, 33, 1190–1211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, J.; Chowdhury, S. Investigating the Barriers in a Typical Journey by Public Transport Users with Disabilities. J. Transp. Health 2018, 10, 361–368. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, Y.; Zeng, W.; Zhou, Y.; Luo, R.; Xu, Z.; Tang, X. Elderly-Oriented Reconstruction Plans of Outer Public Space in Small Town Communities. E3S Web Conf. 2019, 136, 04079. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Annear, M.; Keeling, S.; Wilkinson, T.I.M.; Cushman, G.; Gidlow, B.O.B.; Hopkins, H. Environmental Influences on Healthy and Active Ageing: A Systematic Review. Ageing Soc. 2014, 34, 590–622. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Putri, N.R.I.A.T.; Rekawati, E.; Wati, D.N.K. Relationship of Age, Gender, Hypertension History, and Vulnerability Perception with Physical Exercise Compliance in Elderly. Enferm. Clin. 2019, 29, 541–545. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sabau, E.; Niculescu, G.; Gevat, C.; Lupu, E. The Attitude of the Elderly Persons towards Health Related Physical Activities. Procedia Soc. Behav. Sci. 2011, 30, 1913–1919. [Google Scholar]

- Yung, E.H.K.; Conejos, S.; Chan, E.H.W. Social Needs of the Elderly and Active Aging in Public Open Spaces in Urban Renewal. Cities 2016, 52, 114–122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- OECD. Health at a Glance 2013: OECD Indicators; OECD: Paris, France, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Gajda, R.; Jeżewska-Zychowicz, M. Elderly Perception of Distance to the Grocery Store as a Reason for Feeling Food Insecurity—Can Food Policy Limit This? Nutrients 2020, 12, 3191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Glanz, K.; Sallis, J.F.; Saelens, B.E.; Frank, L.D. Healthy Nutrition Environments: Concepts and Measures. Am. J. Health Promot. 2005, 19, 330–333. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ishikawa, M.; Yokohama, T.; Murayama, N. Relationship between Geographical Factor-Induced Food Availability and Food Intake Status: A Systematic Review. Jpn. J. Nutr. Diet. 2013, 71, 290–297. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Friebe, J.; Schmidt-Hertha, B. Activities and Barriers to Education for Elderly People. J. Contemp. Educ. Stud. Sodob. Pedagog. 2013, 64, 10. [Google Scholar]

- Hameister, D.R. Conceptual Model for the Library’s Service to the Elderly. Educ. Gerontol. 1976, 1, 279–284. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adams, R.G.; Brittain, J.L. Functional Status and Church Participation of the Elderly: Theoretical and Practical Implications. J. Relig. Aging 1988, 3, 35–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garvin, T.; Nykiforuk, C.I.J.; Johnson, S. Can We Get Old Here? Seniors’ Perceptions of Seasonal Constraints of Neighbourhood Built Environments in a Northern, Winter City. Geogr. Ann. Ser. B 2012, 94, 369–389. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mishler, A.D.; Neider, M.B. Improving Wayfinding for Older Users with Selective Attention Deficits. Ergon. Des. Q. Hum. Factors Appl. 2017, 25, 11–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Madden, D.J.; Turkington, T.G.; Provenzale, J.M.; Denny, L.L.; Langley, L.K.; Hawk, T.C.; Coleman, R.E. Aging and Attentional Guidance during Visual Search: Functional Neuroanatomy by Positron Emission Tomography. Psychol. Aging 2002, 17, 24–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- UN-Habitat. Financing Urban Shelter: Global Report on Human Settlements 2005; Sterling: New York, NY, USA, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Idham, N.C.; Andriansyah, M. Temporary Shelters and Disaster Resilience in Sustainability: A Case Study of Sigi After The 7.4 M Palu Earthquake 2018. J. Des. Built Environ. 2021, 21, 1–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ligety, C. A Fresh Look at Emergency and Rapid Shelter Solutions. Cityscape 2021, 23, 459–472. [Google Scholar]

- Meng, L.; Wen, K.-H.; Zeng, Z.; Brewin, R.; Fan, X.; Wu, Q. The Impact of Street Space Perception Factors on Elderly Health in High-Density Cities in Macau—Analysis Based on Street View Images and Deep Learning Technology. Sustainability 2020, 12, 1799. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gehl, J. Life between Buildings: Using Public Space; Island Press: Washington, DC, USA, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Takano, T.; Nakamura, K.; Watanabe, M. Urban Residential Environments and Senior Citizens’ Longevity in Megacity Areas: The Importance of Walkable Green Spaces. J. Epidemiol. Community Health 2002, 56, 913–918. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- d’Acci, L. Quality of Urban Area, Distance from City Centre, and Housing Value. Case Study on Real Estate Values in Turin. Cities 2019, 91, 71–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Glaesener, M.-L.; Caruso, G. Neighborhood Green and Services Diversity Effects on Land Prices: Evidence from a Multilevel Hedonic Analysis in Luxembourg. Landsc. Urban Plan. 2015, 143, 100–111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McCord, J.; McCord, M.; McCluskey, W.; Davis, P.T.; McIlhatton, D.; Haran, M. Effect of Public Green Space on Residential Property Values in Belfast Metropolitan Area. J. Financ. Manag. Prop. Constr. 2014, 19, 117–137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Senetra, A.; Krzywnicka, I.; Mielke, M. An Analysis of the Spatial Distribution, Influence and Quality of Urban Green Space—A Case Study of the Polish City of Tczew. Bull. Geogr. Socio-Econ. Ser. 2018, 42, 129–149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Home, R.; Hunziker, M.; Bauer, N. Psychosocial Outcomes as Motivations for Visiting Nearby Urban Green Spaces. Leis. Sci. 2012, 34, 350–365. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nastran, M. Visiting the Forest with Kindergarten Children: Forest Suitability. Forests 2020, 11, 696. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fang, C.-F.; Ling, D.-L. Guidance for Noise Reduction Provided by Tree Belts. Landsc. Urban Plan. 2005, 71, 29–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Özgüner, H. Cultural Differences in Attitudes towards Urban Parks and Green Spaces. Landsc. Res. 2011, 36, 599–620. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wen, C.; Albert, C.; Von Haaren, C. The Elderly in Green Spaces: Exploring Requirements and Preferences Concerning Nature-Based Recreation. Sustain. Cities Soc. 2018, 38, 582–593. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haase, D. Reflections about Blue Ecosystem Services in Cities. Sustain. Water Qual. Ecol. 2015, 5, 77–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Veerkamp, C.J.; Schipper, A.M.; Hedlund, K.; Lazarova, T.; Nordin, A.; Hanson, H.I. A Review of Studies Assessing Ecosystem Services Provided by Urban Green and Blue Infrastructure. Ecosyst. Serv. 2021, 52, 101367. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Józefowicz, I.; Michniewicz-Ankiersztajn, H. Green and Blue Spaces as the Area for Residential Investments in a Modern City–Example of Bydgoszcz (Poland). Geogr. Tour. 2020, 2, 85–96. [Google Scholar]

- Kłopotowski, M.; Gawryluk, D. Modern Architecture—Residential Buildings. In Buildings 2020+ Constructions, Materials and Installations; Krawczyk, D.A., Ed.; Bialystok University of Technology Bialystok: Białystok, Poland, 2019; pp. 29–52. [Google Scholar]

- Plit, J.; Myga-Piątek, U. The Degree of Landscape Openness as a Manifestation of Cultural Metamorphose. Quaest. Geogr. 2014, 33, 145–154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Zagroba, M.; Szczepańska, A.; Senetra, A. Analysis and Evaluation of Historical Public Spaces in Small Towns in the Polish Region of Warmia. Sustainability 2020, 12, 8356. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burgers, J.; Zuijderwijk, L. At Home at the Neighborhood Square: Creating a Sense of Belonging in a Heterogeneous City. Home Cult. 2016, 13, 101–121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mayer, H.; Knox, P. Small-Town Sustainability: Prospects in the Second Modernity. Eur. Plan. Stud. 2010, 18, 1545–1565. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lobato, A.S. Tourism, Cultural Heritage and Production of Space: An Analysis of the Historic Center of Braganca City, at the State of Para/Turismo. Geo UERJ 2015, 26, 113–135. [Google Scholar]

- Ozimek, A. Landscape Dominant Element–An Attempt to Parameterize the Concept. Tech. Trans. 2019, 116, 35–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Keshtkaran, R. Urban Lanscape: A Review of Key Concepts and Main Purposes. Int. J. Dev. Sustain. 2019, 8, 141–168. [Google Scholar]

- Council of Europe. Landscape Convention Treaty Open for Signature by the Member States and for Accession by the European Union and by the Non-Member States (ETS No. 176); CE: Florence, Italy, 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Draaisma, D. Fabryka Nostalgii: O Fenomenie Pamięci Wieku Dojrzałego [The Nostalgia Factory: On the Phenomenon of Coming-of-Age Memory]; Czarne: Czarne, Poland, 2010; ISBN 8375361798. [Google Scholar]

- Niezgoda, A.; Jerzyk, E. Seniorzy w Przyszłości Na Przykładzie Rynku Turystycznego [Seniors in the Future Using the Example of the Tourism Market]. Zesz. Nauk. Uniw. Szczecińskiego. Probl. Zarządzania Finans. Mark. 2013, 32, 475–489. [Google Scholar]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).