Research on the Impact Mechanism of Self-Quantification on Consumers’ Green Behavioral Innovation

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Theoretical Background

2.1. Self-Quantification

2.2. Green Behavioral Innovation

2.3. Self-Quantification and Green Behavior

3. Research Hypotheses

4. Experimental Design

4.1. Promotional Goal Orientation Experimental Design

4.2. Defensive Goal Orientation Experiment Design

5. Results

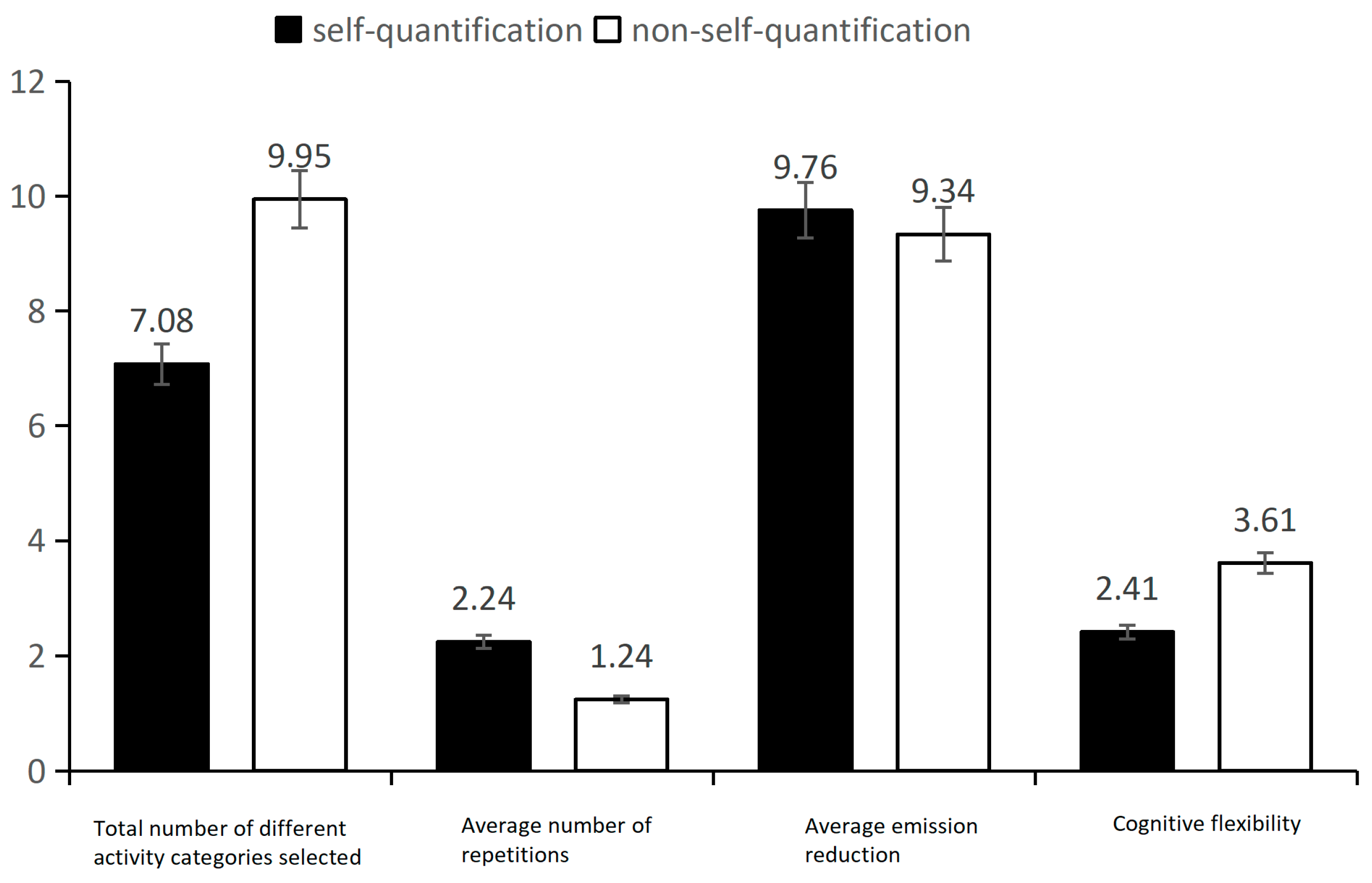

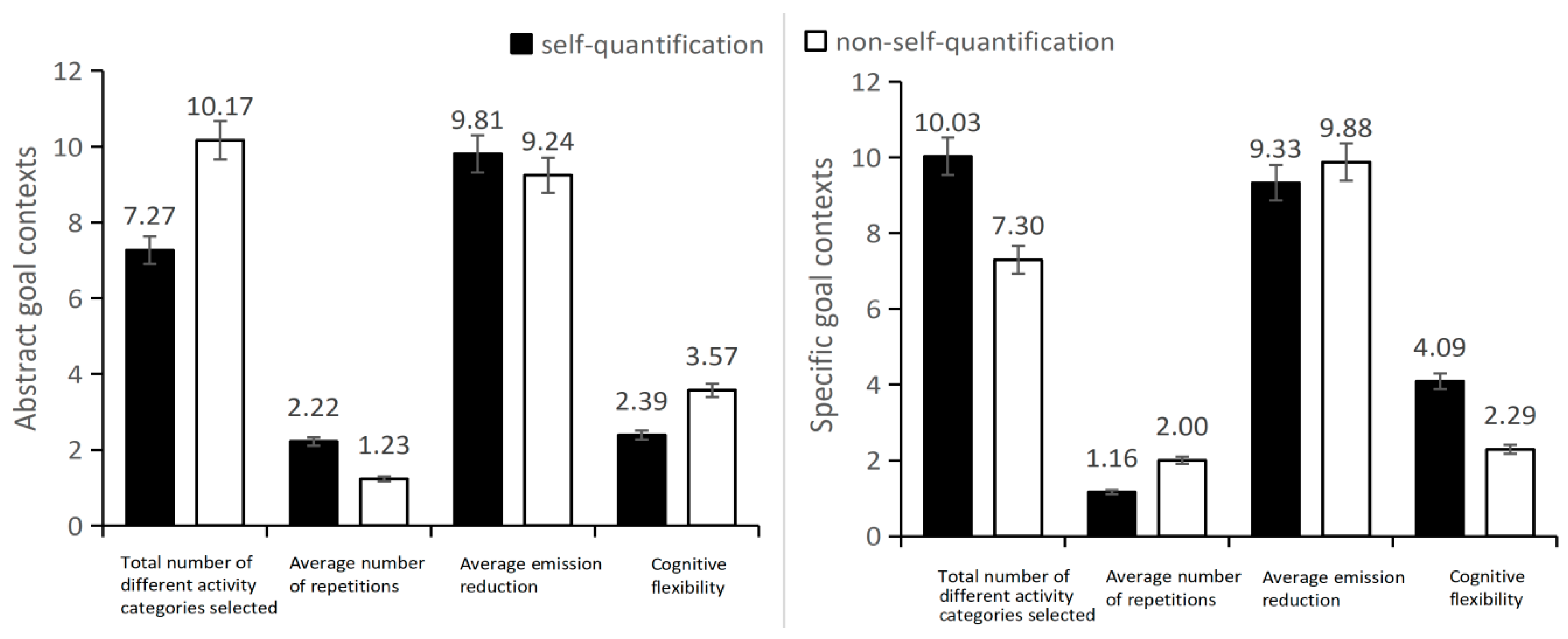

- Firstly, in promotional goal-oriented green consumption activities, such as emission reduction, when the participation goals are relatively vague and abstract, non-self-quantification consumers tend to select a wider variety of activity categories during the activity period. This results in a lower repetition of activity category selection, indicative of higher green behavioral innovation, albeit potentially leading to a relatively lower final participation outcome. In contrast, consumers who engage in self-quantification tend to select fewer types of activity categories, with a higher degree of repetition in their activity category selection. This pattern reveals lower levels of green behavioral innovation but often translates into a relatively higher participation outcome in the activities.

- Secondly, in promotional goal-oriented green consumption activities, such as emission reduction, when the participation goals are more precise and specific, non-self-quantification consumers tend to select fewer types of activity categories during the activity period. This leads to a higher repetition of activity category selection, indicative of lower green behavioral innovation, yet often resulting in a relatively higher final participation outcome. Conversely, consumers who engage in self-quantification select a wider variety of activity categories, with lower repetition in their activity category selection. This pattern exhibits higher levels of green behavioral innovation but may result in a relatively lower participation outcome in the activities. However, the participation outcome of these self-quantification consumers is still capable of meeting the specified goal requirements.

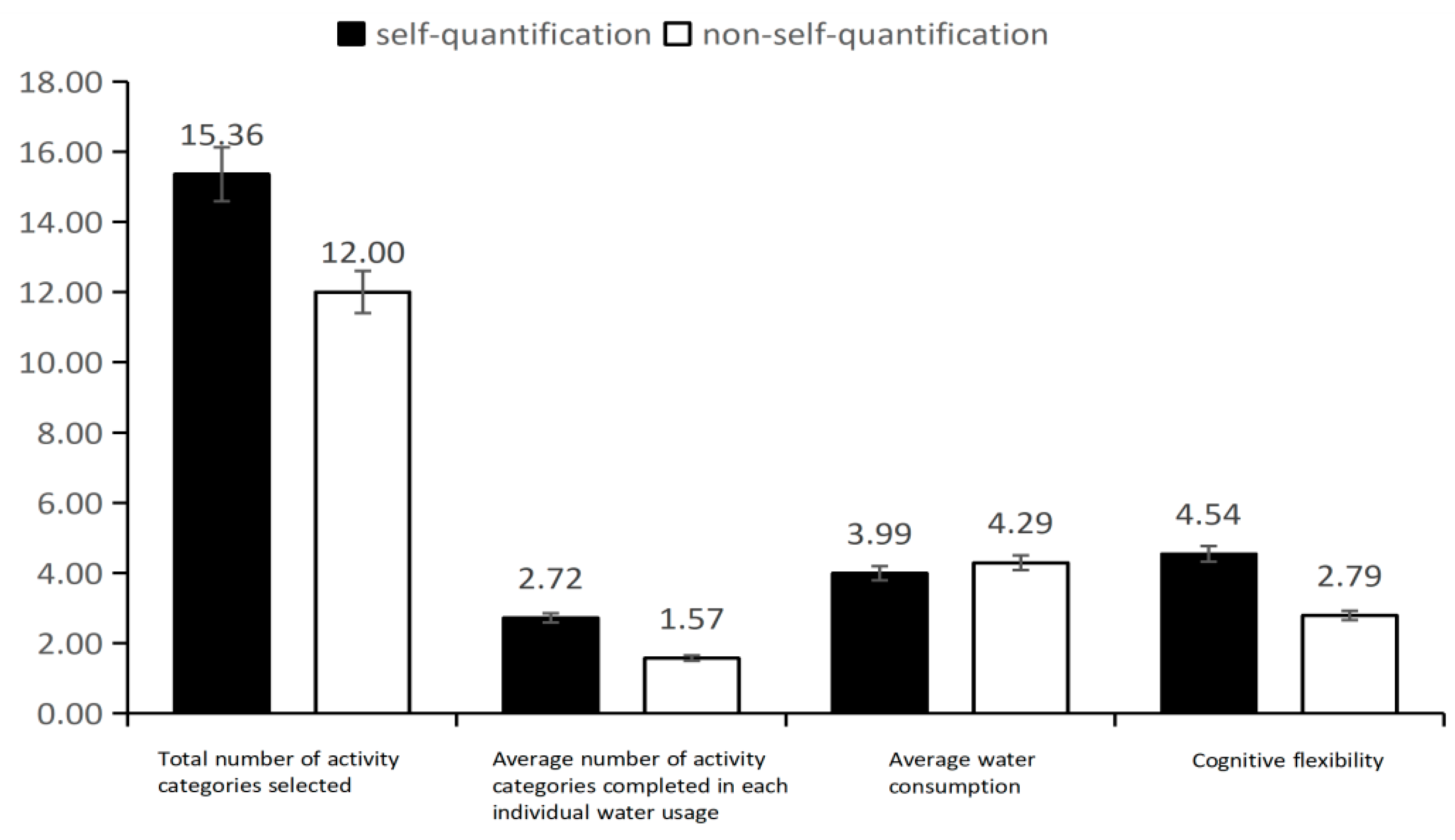

- Thirdly, in defensive goal-oriented green consumption activities, such as water use, when the participation goals are relatively vague and abstract, during the consumption period, non-self-quantification consumers tend to participate in fewer types of activity categories and complete fewer activity categories with each energy usage, demonstrating lower levels of green behavioral innovation. Consequently, they tend to use relatively more energy for the activity. In contrast, consumers who engage in self-quantification participate in a wider range of activity categories, completing more activity categories with each energy usage and exhibiting higher levels of green behavioral innovation. This ultimately results in the use of relatively less energy for their activities.

- Fourthly, in defensive goal-oriented green consumption activities, such as water use, when the participation goals are more precise and specific, during the consumption period, non-self-quantification consumers tend to participate in more types of activity categories and complete more activity categories with each energy usage, demonstrating higher levels of green behavioral innovation. As a result, they tend to use relatively less energy for the activity. On the other hand, consumers who engage in self-quantification may participate in fewer types of activity categories and complete fewer activity categories with each energy usage, exhibiting lower levels of green behavioral innovation. This can lead to relatively higher energy usage for their activities, although the total energy usage remains within the specified goal limitation.

6. Discussions

6.1. Theoretical Contributions

6.2. Practical Insights

6.3. Research Limitations and Future Research Directions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Rapp, A.; Cena, F.; Marcengo, A. Editorial of the special issue on quantified self and personal informatics. Computers 2018, 7, 14–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Zhang, H.; Zhang, C.; Li, D. The impact of self-quantification on consumers’ participation in green consumption activities and behavioral decision-making. Sustainability 2020, 12, 4098. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Li, D.; Zhang, C.; Zhang, H. Quantified or nonquantified: How quantification affects consumers’ motivation in goal pursuit. J. Consum. Behav. 2019, 18, 120–134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shin, D.; Biocca, F. Health experience model of personal informatics: The case of a quantified self. Comput. Hum. Behav. 2017, 69, 62–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hamari, J.; Hassan, L.; Dias, A. Gamification, quantified-self or social networking? Matching users’ goals with motivational technology. User Model. User Adap. 2018, 28, 35–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Etkin, J. The hidden cost of personal quantification. J. Consum. Res. 2016, 42, 967–984. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fischer, C. Feedback on household electricity consumption: A tool for saving energy? Energy Effic. 2008, 1, 79–104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ehrhardt-Martinez, K.; Donnelly, K.A.; Laitner, S. Advanced Metering Initiatives and Residential Feedback Programs: A Meta-Review for Household Electricity-Saving Opportunities; American Council for an Energy-Efficient Economy: Washington, DC, USA, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Oltra, C.; Boso, A.; Espluga, J.; Prades, A. A qualitative study of users’ engagement with real-time feedback from in-house energy consumption displays. Energy Policy 2013, 61, 788–792. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Westin, E. Visualization of Quantified Self with Movement and Transport Data; KTH Royal Institute of Technology: Stockholm, Sweden, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Siepmann, C.; Kowalczuk, P. Understanding continued smartwatch usage: The role of emotional as well as health and fitness factors. Electron. Mark. 2021, 31, 795–809. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Greene, A.K.; Brownstone, L.M. “Just a place to keep track of myself”: Eating disorders, social media, and the quantified self. Fem. Media Stud. 2023, 23, 508–524. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Swann, C.; Jackman, P.C.; Lawrence, A. The (over)use of SMART goals for physical activity promotion: A narrative review and critique. Health Psychol. Rev. 2023, 17, 211–226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wyer, W.R.S., Jr.; Xu, A.J. The role of behavioral mind-sets in goal-directed activity: Conceptual underpinnings and empirical evidence. J. Consum. Psychol. 2010, 20, 107–125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, Z.H.; Chang, C.T.; Lee, Y.K. Linking hedonic and utilitarian shopping values to consumer skepticism and green consumption: The roles of environmental involvement and locus of control. Rev. Manag. Sci. 2020, 14, 61–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amin, S.; Tarun, M.T. Effect of consumption values on customers’ green purchase intention: A mediating role of green trust. Soc. Responsib. J. 2021, 17, 1320–1336. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tietze, F.; Hansen, E.G. To own or to use: How product service systems impact firms’ innovation behaviour. Eur. Econ. Rev. 2013, 8, 53–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feng, H.; Wang, F.; Song, G.; Liu, L. Digital transformation on enterprise green innovation: Effect and transmission mechanism. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 19, 10614. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Petersen, R.R.; Lukas, A.; Wiil, U.K. QS mapper: A transparent data aggregator for the quantified self: Freedom from particularity using two-way mappings. In Proceedings of the 10th International Joint Conference on Software Technologies, Colmar, France, 20–22 July 2015; Volume 1, pp. 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.; Lv, X.; Tang, Z. The impact of mortality salience on quantified self behavior during the COVID-19 pandemic. Pers. Individ. Differ. 2021, 180, 110972. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, X.; Dong, F. Why do consumers make green purchase decisions? Insights from a systematic review. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2020, 17, 6607. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shi, H.; Chen, R. Goal specificity or ambiguity? Effects of self-quantification on persistence intentions. J. Res. Interact. Mark. 2022, 16, 569–584. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Suárez, E.; Hernández, B.; Gil-Giménez, D. Determinants of frugal behavior: The influences of consciousness for sustainable consumption, materialism, and the consideration of future consequences. Front. Psychol. 2020, 11, 567752. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peloza, J.; White, K.; Shang, J. Good and guilt-free: The role of self-accountability in influencing preferences for products with ethical attributes. J. Mark. 2013, 77, 104–119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sidelkivska, V.; Bilbao-Calabuig, P. Conceptualizing cognitive and behavioral elements of individual’s creativity and innovation: Systematic literature review. Eur. J. Soc. Theory 2023, 7, 1–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kurznack, L.; Schoenmaker, D.; Schramade, W. A model of long-term value creation. J. Sustain. Financ. Investig. 2021, 5, 1–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kuzma, E.; Padilha, L.S.; Sehnem, S.; Julkovski, D.J.; Roman, D.J. The relationship between innovation and sustainability: A meta-analytic study. J. Clean. Prod. 2020, 259, 120745. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moraes, C.R.B.; Abreu, A.; Woida, L.M. Innovation management through knowledge and organizational socialization. Informação Informação 2012, 17, 103–132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- White, K.; Habib, R.; Hardisty, D.J. How to SHIFT consumer behaviors to be more sustainable: A literature review and guiding framework. J. Mark. 2019, 83, 22–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Casalegno, C.; Candelo, E.; Santoro, G. Exploring the antecedents of green and sustainable purchase behaviour: A comparison among different generations. Psychol. Market. 2022, 39, 1007–1021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jorge, A.; Amaral, I.; De Matos Alves, A. “Time Well Spent”: The ideology of temporal disconnection as a means for digital well-being. Int. J. Commun. 2022, 16, 1551–1572. [Google Scholar]

- Park, H.; Feigenbaum, J. Bounded rationality, lifecycle consumption, and social security. J. Econ. Behav. Organ. 2018, 146, 65–105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feng, S.; Mäntymäki, M.; Dhir, A.; Salmela, H. How self-tracking and the quantified self promote health and well-being: Systematic review. J. Med. Internet Res. 2021, 23, e25171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spaargaren, G. Sustainable consumption: A theoretical and environmental policy perspective. In The Ecological Modernisation Reader; Routledge: Abingdon, UK, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Toyama, M.; Yamada, Y. The relationships among tourist novelty, familiarity, satisfaction, and destination loyalty: Beyond the novelty-familiarity continuum. J. Int. Mark. 2012, 4, 10–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mehta, R.; Zhu, M. Creating when you have less: The impact of resource scarcity on product use creativity. J. Consum. Res. 2015, 42, 767–782. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shao, S.; Hu, Z.; Cao, J.; Yang, L. Environmental regulation and enterprise innovation: A review. Bus. Strateg. Environ. 2020, 29, 1465–1478. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pizam, A.; Reichel, A.; Uriely, N. Sensation seeking and tourist behavior. J. Hosp. Market. Manag. 2001, 9, 17–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Isen, A.M. An influence of positive affect on decision making in complex situations: Theoretical issues with practical implications. J. Consum. Psychol. 2001, 11, 75–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pirson, M.; Langer, E.; Bodner, T. The Development and Validation of the Langer Mindfulness Scale-Enabling a Socio-Cognitive Perspective of Mindfulness in Organizational Contexts; Fordham University Schools of Business: Manhattan, NY, USA, 2012; pp. 1–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ionescu, T. Exploring the nature of cognitive flexibility. New Ideas Psychol. 2012, 30, 190–200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Herd, K.B.; Ravi, M.; Stacy, W. Head vs. heart: The effect of objective versus feelings-based mental imagery on new product creativity. J. Consum. Res. 2019, 46, 36–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, Y.; Deng, W. Moderating the link between discrimination and adverse mental health outcomes: Examining the protective effects of cognitive flexibility and emotion regulation. PLoS ONE 2023, 18, e0282220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Förster, J.; Friedman, R.S.; Liberman, N. Temporal construal effects on abstract and concrete thinking: Consequences for insight and creative cognition. J. Pers. Soc. Psychol. 2004, 87, 177–189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dangelico, R.M.; Vocalelli, D. “Green Marketing”: An analysis of definitions, strategy steps, and tools through a systematic review of the literature. J. Clean. Prod. 2017, 165, 1263–1279. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vermeir, I.; Weijters, B.; De Houwer, J. Environmentally sustainable food consumption: A review and research agenda from a goal-directed perspective. Front. Psychol. 2020, 11, 1603. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Dreu, C.K.W.; Baas, M.; Boot, N.C. Oxytocin enables novelty seeking and creative performance through upregulated approach: Evidence and avenues for future research. Wiley Cogn. Sci. 2015, 6, 409–417. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gable, P.A.; Harmon-Jones, E. The motivational dimensional model of affect: Implications for breadth of attention, memory, and cognitive categorization. Cogn. Emot. 2010, 24, 322–337. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Z.; Liu, Y.; Jiang, X. The effect of low versus high approach-motivated positive affect on cognitive control. Acta Psychol. Sin. 2013, 45, 546–555. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dreisbach, G.; Fröber, K. On how to be flexible (or not): Modulation of the stability-flexibility balance. Curr. Dir. Psychol. Sci. 2019, 28, 3–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Ittersum, K.; Wansink, B.; Sheehan, D. Smart shopping carts: How real-time feedback influences spending. J. Mark. 2013, 77, 21–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moser, S.; Kleinhückelkotten, S. Good intents, but low impacts: Diverging importance of motivational and socioeconomic determinants explaining pro-environmental behavior, energy use, and carbon footprint. Environ. Behav. 2018, 50, 626–656. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fernandes, D.; Mandel, N. Political conservatism and variety-seeking. J. Consum. Psychol. 2014, 24, 79–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chiew, K.S.; Braver, T.S. Positive affect versus reward: Emotional and motivational influences on cognitive control. Front. Psychol. 2011, 2, 279. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Zhang, H.; Xie, J.; Zhang, C. The influence of self-quantification on individual’s participation performance and behavioral decision-making in physical fitness activities. Humanit. Soc. Sci. Commun. 2023, 10, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramirez, E.; Jiménez, F.R.; Gau, R. Concrete and abstract goals associated with the consumption of environmentally sustainable products. Eur. J. Mark. 2015, 49, 1645–1665. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Swann, C.; Schweickle, M.J.; Peoples, G.E. The potential benefits of nonspecific goals in physical activity promotion: Comparing open, do-your-best, and as-well-as-possible goals in a walking task. J. Appl. Sport. Psychol. 2022, 34, 384–408. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ülkümen, G.; Cheema, A. Framing goals to influence personal savings: The role of specificity and construal level. J. Mark. Res. 2011, 48, 958–969. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, L.; Wang, X. The impact of the target framework effect of causal marketing advertising on consumer purchase intention. Dongyue Trib. 2016, 37, 144–151. [Google Scholar]

- Jung, J.H.; Schneider, C.; Valacich, J. Enhancing the motivational affordance of information systems: The effects of real-time performance feedback and goal setting in group collaboration environments. Manag. Sci. 2010, 56, 724–774. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sevilla, J.; Lu, J.; Kahn, B.E. Variety seeking, satiation, and maximizing enjoyment over time. J. Consum. Psychol. 2019, 29, 89–103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scott, M.L.; Nowlis, S.M. The effect of goal specificity on consumer goal reengagement. J. Consum. Res. 2013, 40, 444–459. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Keinan, A.; Kivetz, R. Productivity orientation and the consumption of collectable experiences. J. Consum. Res. 2011, 37, 935–950. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zou, Y.; Li, P.; Hofmann, S.G. The mediating role of non-reactivity to mindfulness training and cognitive flexibility: A randomized controlled trial. Front. Psychol. 2020, 11, 1053. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Swan, M. The quantified self: Fundamental disruption in big data science and biological discovery. Big Data 2013, 1, 85–99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Froehlich, J.; Findlater, L.; Ostergren, M. The design and evaluation of prototype eco-feedback displays for fixture-level water usage data. In Proceedings of the SIGCHI Conference on Human Factors in Computing Systems, Austin, TX, USA, 5–10 May 2012; Volume 5, pp. 2367–2376. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, X.; Lynch, J.G.; Chen, Q. Reconsidering Baron and Kenny: Myths and truths about mediation analysis. J. Consum. Res. 2010, 37, 197–206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Preacher, K.J.; Rucker, D.D.; Hayes, A.F. Addressing moderated mediation hypotheses: Theory, methods, and prescriptions. Multivar. Behav. Res. 2007, 42, 185–227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ratner, R.K.; Kahn, B.E. The impact of private versus public consumption on variety-seeking behavior. J. Consum. Res. 2002, 29, 246–257. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Activity Name | Reducing Carbon Emissions Value | Activity Name | Reducing Carbon Emissions Value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Reduce disposable tableware usage for 1 time | 20 g CO2 | Reduce computer usage for 1 h | 190 g CO2 |

| Recycle 1 plastic bottle | 26 g CO2 | Reduce elevator usage for 1 time | 218 g CO2 |

| Recycle 1 cardboard box | 37 g CO2 | Reduce air condition usage for 1 h | 621 g CO2 |

| Reduce fluorescent lamp usage for 1 h | 41 g CO2 | Recycle 1 book | 660 g CO2 |

| Reduce electric fan usage for 1 h | 45 g CO2 | Walk for 1 h | 2254 g CO2 |

| Raise a green plant for 1 day | 90 g CO2 | Recycle 1 old piece of clothing | 3600 g CO2 |

| Reduce washing machine usage for 1 h | 180 g CO2 | Subway travel for 1 h | 3736 g CO2 |

| Activity Name | Activity Name | Activity Name | Activity Name |

|---|---|---|---|

| Wash fruits | Take a shower | Mop the floor | Scrub clothes |

| Wash dishes | Specifically wash hair | Flush toilets | Rinse clothes |

| Brush teeth | Wash face | Water flowers | Wash duster |

| Specially wash hands | Wash feet | Wipe tables and chairs | Wipe windows |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Zhang, Y.; Dai, Z.; Zhang, H.; Hu, G. Research on the Impact Mechanism of Self-Quantification on Consumers’ Green Behavioral Innovation. Sustainability 2024, 16, 8383. https://doi.org/10.3390/su16198383

Zhang Y, Dai Z, Zhang H, Hu G. Research on the Impact Mechanism of Self-Quantification on Consumers’ Green Behavioral Innovation. Sustainability. 2024; 16(19):8383. https://doi.org/10.3390/su16198383

Chicago/Turabian StyleZhang, Yudong, Zhangyuan Dai, Huilong Zhang, and Gaojun Hu. 2024. "Research on the Impact Mechanism of Self-Quantification on Consumers’ Green Behavioral Innovation" Sustainability 16, no. 19: 8383. https://doi.org/10.3390/su16198383

APA StyleZhang, Y., Dai, Z., Zhang, H., & Hu, G. (2024). Research on the Impact Mechanism of Self-Quantification on Consumers’ Green Behavioral Innovation. Sustainability, 16(19), 8383. https://doi.org/10.3390/su16198383