1. Introduction

China is pressing to recycle or properly dispose of large amounts of e-waste, as its electronic products have reached the stage of massive scrapping [

1]. Particularly, the digital acceleration brought about by COVID-19 has led to a sharp increase in the amount of e-waste [

2]. However, the traditional manual recycling mode of going from door to door has become increasingly challenging due to escalating labor costs [

3,

4]. It is estimated that the total number of old and unused smartphones in China will reach 6 billion by 2025, but the recycling rate will be less than 4% [

5]. To address this social problem, the Chinese government has launched an online recycling campaign. More and more e-waste online recycling platforms, such as Aihuishou, Aibolyu, Hushanghuishou, Beijingyingchuang and Huishouge, have been established successively, contributing to the proliferation of online e-waste recycling [

6,

7].

Online recycling proposed a novel solution to China’s growing e-waste challenges. Residents first inquire through the e-waste online recycling platform. After reaching a preliminary agreement on recycling, they complete the offline delivery based on the volume of e-waste and the convenience of offline recycling. This is done through one of three methods: scheduled doorstep collection, mail-in recycling, or drop-off at physical stores. Finally, they receive corresponding points or monetary compensation. However, in practice, residents’ participation remains lackluster [

8]. For instance, with mobile phones, research shows that, while residents’ willingness to participate in online recycling of e-waste is pretty high, 79.3% of residents still leave their discarded mobile phones at home [

9]. It is apparent that, although the majority of residents recognize the significance of e-waste online recycling for resource preservation, environmental protection, and model innovation, their actual behavior in e-waste recycling does not align with this attitude. This suggests a certain level of inconsistency between residents’ intentions and behaviors. If left unaddressed, the intention–behavior gap in e-waste online recycling participation will seriously restrict the development of China’s e-waste online recycling and, even further, impede the realization of China’s “Internet + Recycling” strategy.

The emergence of e-waste online recycling has gradually attracted increasing scholarly attention over time. Numerous scholars have investigated the development model, current status, and business ecosystem of e-waste online recycling [

10,

11,

12,

13]. In recent years, increasing attention has been given to studying residents’ behavior in e-waste online recycling. Researchers have studied the antecedents of e-waste online recycling intentions and behavior using established theories such as the theory of planned behavior (TPB), technology acceptance model (TAM), elaboration likelihood model (ELM), innovation diffusion theory (IDT), and social cognition theory (SCT). Factors such as perceived behavioral control, subjective norms, attitudes, economic motivation, perceived convenience, and perceived innovation characteristics play crucial roles in influencing e-waste online recycling intentions. However, price disadvantage is the main obstacle for residents to participate in e-waste online recycling. Privacy concern, pricing fairness concern, environmental mental concern, and income level have different moderating effects [

5,

14,

15]. Some scholars focus on antecedents, while others concentrate on intervention strategies for e-waste online recycling intentions. For example, Wang et al. found that providing green information and economic incentives can increase the participation intention of consumers [

16,

17].

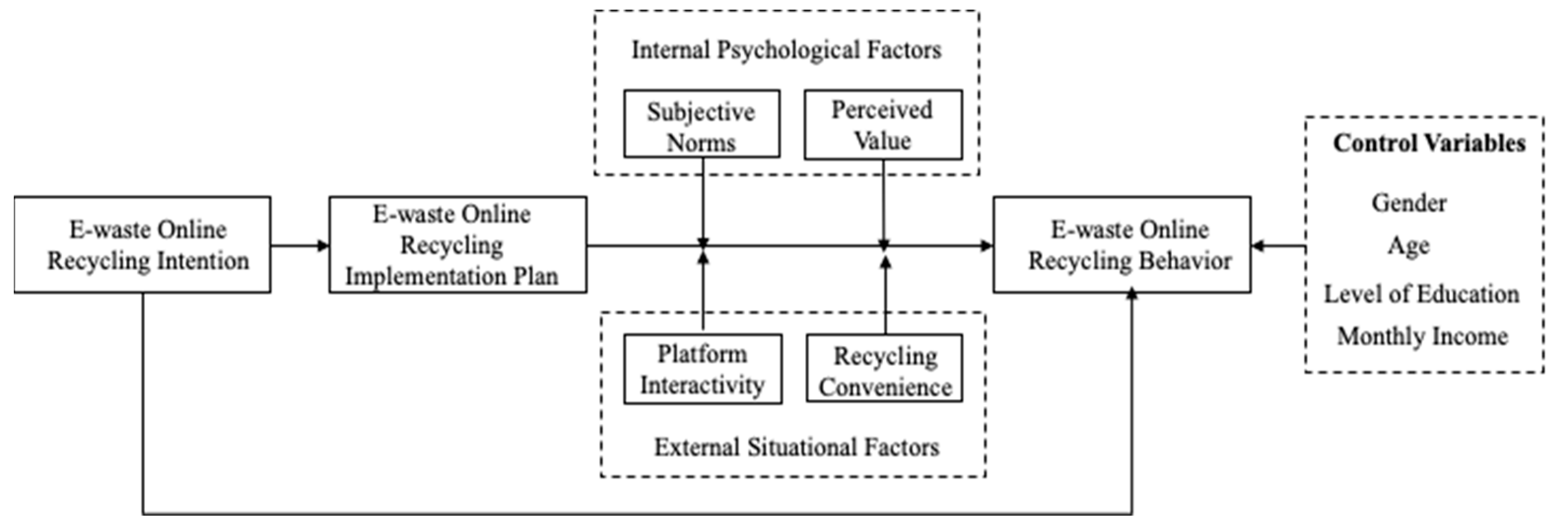

Scholars generally believe that recycling intentions can predict subsequent actual participation behavior. However, unlike traditional e-waste recycling behavior, online recycling integrates online information flow, fund flow, and offline logistics. The complexity of online and offline interactions renders residents’ recycling intentions more susceptible to disruption by internal psychological factors and external situational factors, hindering the transformation of intention into actual behaviors. Unfortunately, the existing research has failed to explain why residents do not do what they say in e-waste online recycling and how to promote the conversion of intention into behaviors effectively.

Taking urban residents in China as respondents, this paper uses a questionnaire survey to explore the psychological mechanism and determinants underlying the intention–behavior gap in e-waste online recycling. Semi-structured interviews were also conducted to provide additional support for our empirical findings and help us interpret results. The rest of the paper continues: First, the theoretical background and research hypotheses are presented. Then, the research method is elaborated, followed by the data analysis and results. Finally, the findings are discussed, and theoretical implications and management recommendations are proposed. In addition, the paper summarizes research limitations and points out future research directions.

4. Results

4.1. Common Method Bias Testing

The self-report questionnaire method used in this study has the potential to introduce common method bias. Therefore, before testing the scale’s reliability, validity, and assumptions, the study employed the Harman single-factor method to test the variables for common method bias. Four factors with eigenvalues greater than 1 were obtained after exploratory factor analysis without rotation setup, and the first factor explained 36.84% of the total variance, which was less than 40% of the critical criterion, indicating that the influence of common method bias on the results of the statistical analysis in this study was not significant.

4.2. Reliability and Validity Testing

For the reliability and validity analysis of the variables involved in the integrated model, the study utilized SPSS 26.0 and AMOS24.0. The test results of each latent variable are shown in

Table 2.

The internal consistency coefficient and combined reliability were used to measure the internal consistency reliability. The results show that the Cronbach’s Alpha coefficient of each variable in the scale is greater than 0.7, indicating good internal consistency reliability. Additionally, the combined reliability (CR) falls between 0.7 and 0.9, which is higher than the acceptable standard of 0.7, indicating that the scale has high reliability.

Validity reflects the degree of effectiveness or accuracy of a measurement method, i.e., whether the questionnaire items are measured accurately and effectively. Conducting a validity test on the questionnaire is a fundamental prerequisite for empirical research. We examined construct validity, convergent validity, and discriminant validity separately. Since the questions of the six variables all have theoretical support and mature scales with reference, the study deemed it appropriate to conduct confirmatory factor analysis (CFA) to verify whether the items can reflect the variables. CFA was carried out using AMOS26.0, and the factor loadings were calculated. The analysis results showed that, among the 18 observed variables, the factor load for the remaining 16 variables was all greater than 0.6, except for PV1 and IP1, which were 0.53 and 0.52, respectively. The measurement results of the model parameters (CMIN/DF = 1.819 < 2, RMSEA = 0.042 < 0.08, IFI = 0.968 > 0.9, TLI = 0.959 > 0.9, and CFI = 0.968 > 0.9) all indicate that the model has a good fit and high persuasiveness. Then, the convergent validity of the scale was evaluated by factor loading, average variance extraction (AVE), and combined reliability (CR). The results show that the lowest CR value of variables is 0.70, and the AVE value of each variable is greater than 0.45 within the allowable error range, indicating that this study has acceptable convergent validity [

47]. The heterogeneity–single-trait correlation ratio (HTMT) is an effective method to evaluate the discriminant validity of variance-based structural equations [

48]. This paper used the HTMT method to test the variables’ discriminant validity. According to the standard of HTMT0.85, all the values contained in the table are less than 0.85, indicating no problem with discriminant validity among the variables (as shown in

Table 3).

4.3. Direct Effect Testing

Based on ensuring that the indicators of the structural model meet the evaluation criteria, this study used logistic regression to test the relationship between variables. Before this, the multicollinearity test was carried out to ensure the stability of the research results. The study used the variance inflation factor (VIF) to determine whether there was a multicollinearity problem. Generally, when the VIF value is less than 5, it can be considered that there is no multicollinearity problem. By establishing a regression model, the result shows that the maximum VIF in this paper is 1.926, which is far lower than the measurement standard of 5, so it can be considered that there is no problem of multicollinearity.

When constructing the regression model, this paper takes the residents’ gender, age, education, and income as control variables. First, the actual behavior of e-waste online recycling was included as a dependent variable in the model. Then, the online recycling intention was included as an independent variable in the analysis to create a model. Next, the e-waste online recycling implementation plan is used as an independent variable to develop a new model. Finally, the intention to recycle e-waste online is taken as an independent variable, and the implementation plan of e-waste online recycling is used as a dependent variable to generate another model. By observing the regression coefficient and the significance level of the variables in the model, the study judges whether the hypothesis is supported.

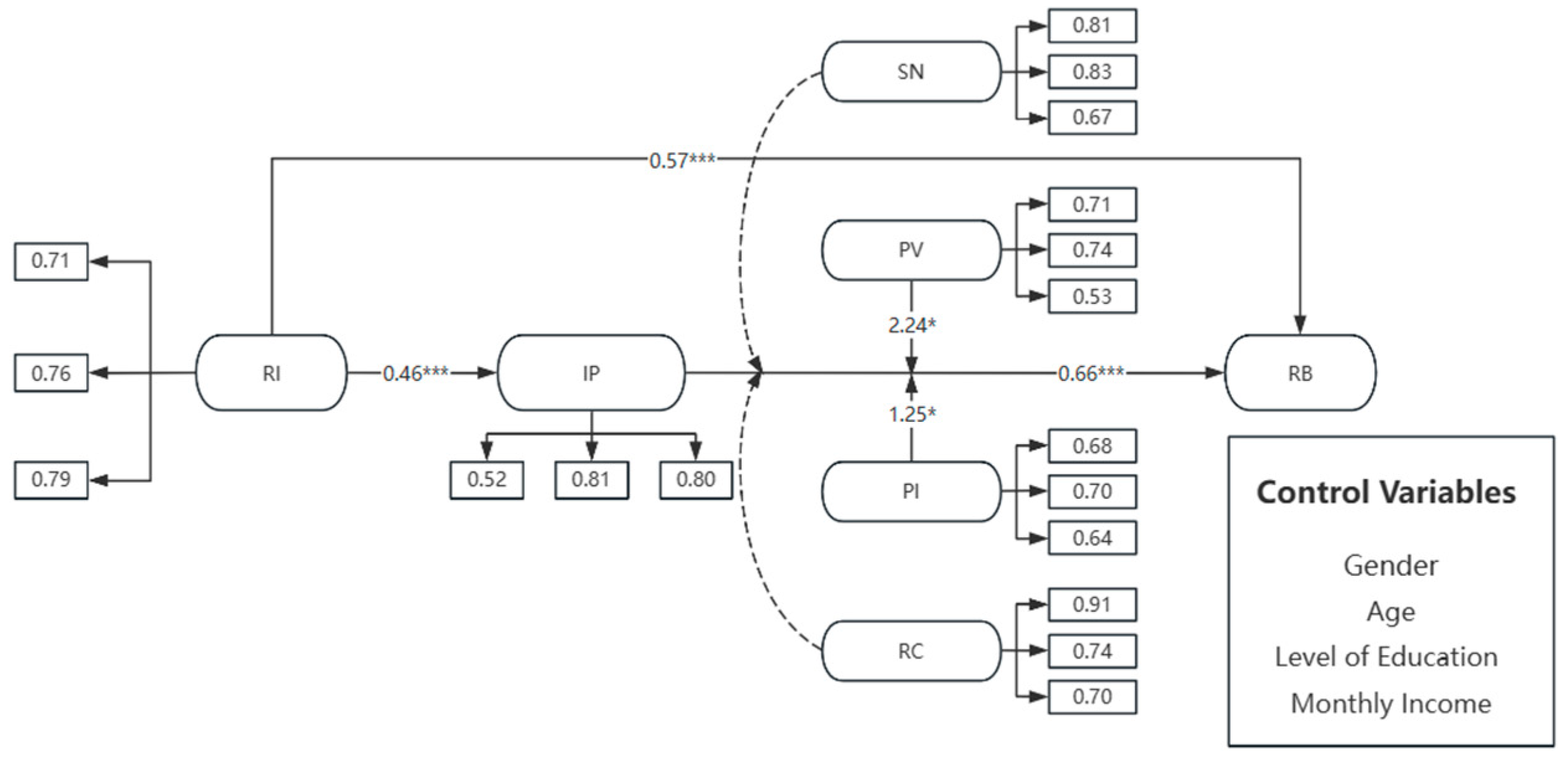

The specific analysis results of the hypothesis test are presented in

Figure 2. From the hypothesis verification of the direct path, it can be observed that the standardized path coefficient of residents’ e-waste online recycling intention to actual behavior is 0.566 (

p < 0.001), the standardized path coefficient of the intention to the implementation plan is 0.458 (

p < 0.001), and the standardized path coefficient of the residents’ e-waste online recycling implementation plan to the actual participation behavior is 0.656 (

p < 0.001). All these findings reached statistical significance. According to the test results of direct effects, hypotheses H1, H2, and H3 are verified, providing hard evidence for the verification of subsequent hypotheses.

4.4. Mediation Effect Testing

Based on proving the direct effect hypothesis, the implementation plan is included in the model as a mediator variable. The mediation effect of residents’ e-waste online recycling implementation plan between intention and behavior is further tested by using the Process plug-in Model4 in SPSS 26.0. The results show that the path coefficient of the direct effect of the implementation plan is 0.352, while the path coefficient of the indirect effect is 0.214. The 95% bootstrap confidence intervals of both the direct effect and the indirect effect do not include a zero value, indicating that the mediation effect is significant. As a partial mediator, the implementation plan has a significant relationship between participation intention and actual participation, thus supporting hypothesis H4.

The analysis of the interview content further confirmed the aforementioned results. First, online recycling intention is a prerequisite for participation, as intention leads to behavior. For example, Interviewee H mentioned “When it comes to electronic products, whether buying or selling, I don’t like using online methods because I feel that offline transactions offer more assurance in terms of quality or recycling prices, so I wouldn’t use an e-waste online recycling platform (H-8)”. Second, once the intention to recycle is formed, residents will further develop an implementation plan based on “wish fulfillment”. For instance, Interviewee C said “I think these recycling platforms are quite good. You don’t even have to leave your home to sell your unused phones. The main reason I haven’t used them yet is that my current phone and computer are still in good condition, and I don’t have any idle devices. But when a new model I like comes out, I plan to use this method to recycle my old ones (C-12)”. Third, in terms of the relationship between the implementation plan and recycling behavior, the analysis of the interview transcripts shows that residents tend to act based on “need stimulation”. The implementation plan emphasizes that they already have items ready for recycling or are prepared for online recycling, which further stimulates their desire and motivation to recycle through online platforms, eventually leading to actual behavior. For example, Interviewee Y stated “I once saw a counter in a mall that was an offline display for an online electronic waste recycling platform. My friend happened to be planning to buy a new camera, so he used the screen to check the recycling price for his old camera, and he ended up recycling it there (Y-5)”.

4.5. Moderating Effect Testing

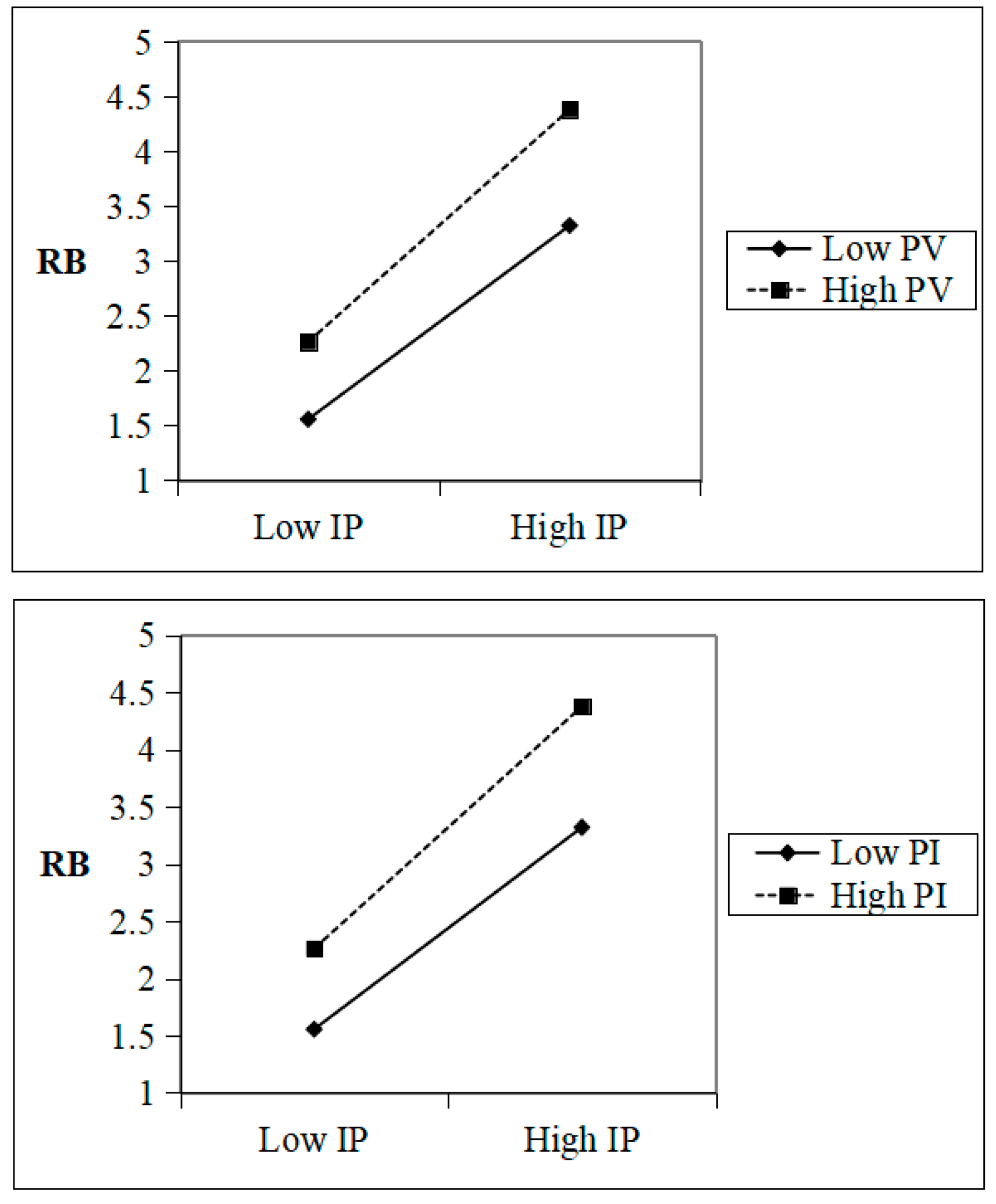

The study used the binary logistic regression method to test the moderating effect of the model hierarchically. First, all variables were centralized. Second, the centralized IP was multiplied by the centralized four moderator variables, respectively, to obtain four interaction terms. Finally, regression analysis was carried out, and the control variables, centralized variables, and interaction items were incorporated into the model layer by layer for analysis. The results of the moderating effect were obtained, as shown in the simple slope analysis diagram in

Figure 3.

The test results of the moderating effect of subjective norms in the process of residents’ e-waste online recycling implementation plan on actual participation behavior show that the correlation between the interaction term of subjective norms and implementation plan and residents’ actual participation behavior is not significant. Therefore, hypothesis H5 is not supported.

The test results of the moderating effect of perceived value on the impact of residents’ e-waste online recycling implementation plan on actual participation behavior show that the interaction term between perceived value and recycling implementation plan is significantly positively correlated with residents’ actual participation behavior (β = 2.238, p < 0.05). Therefore, hypothesis H6 holds.

The test results of the moderating effect of platform interactivity on the impact of residents’ e-waste online recycling implementation plan on actual participation behavior show that the interaction item of platform interactivity and implementation plan is significantly positively correlated with residents’ actual participation behavior (β = 1.250, p < 0.05). Therefore, hypothesis H7 holds.

The test results of the moderating effect of recycling convenience on the impact of residents’ e-waste online recycling implementation plan on actual participation behavior show that the interaction item of recycling convenience and the recycling implementation plan is not significantly correlated with residents’ actual participation behavior. Therefore, hypothesis H8 is rejected.

The analysis of the interview transcripts further revealed two types of moderating effects. First is the reinforcing effect brought by perceived value and platform interactivity. High perceived value and platform interactivity encourage residents to complete the process to gain monetary, environmental, or smooth user experience benefits, thereby promoting actual behavior. For instance, Interviewee T mentioned “I just tried out the AiHuiShou platform, and I found the experience quite good. It’s easy to use, like when a teacher highlights key points in class—you instantly know how to complete the process. Next time I need to replace an electronic device, I will use this method (T-34)”. Similarly, Interviewee M stated “This method is better than the old street vendors collecting items. My old phone was just sitting at home, not being used. Through this method, I got a few hundred yuan, and it also helps protect the environment. So, considering this, I recycled my old phone through this platform (M-6)”. However, for social norms and recycling convenience, the moderating effect was not significant due to a neutralizing effect. The non-exclusive nature of recycling convenience and the sporadic influence of social norms reduced the moderating impact of these variables. For example, Interviewee X said “Other recycling methods are also convenient now. For instance, when you buy a new phone, the retailer will remind you that you can trade in your old phone, and the value is directly deducted from the new one. So, I don’t think convenience is a unique advantage of online recycling platforms, and it doesn’t increase my willingness to use such a platform (X-52)”. Interviewee W noted “Many people around me seem to give their old phones to their elders at home, rather than using these platforms to recycle them (W-26)”.

5. Discussion and Conclusions

5.1. Findings and Practical Implication

This is the pioneering study to explain the influencing mechanism of why urban residents say one thing and do another when they participate in e-waste online recycling. We constructed a theory model combining the mediating factor of the implementation plan and incorporating the moderating effects of intrinsic psychological and extrinsic situational factors. Specifically, the main conclusions and practical implication of this study are as follows (as shown in

Table 4).

First, residents’ e-waste online recycling intention predicts subsequent actual recycling behavior. Urban residents with a stronger willingness to recycle e-waste online are more likely to use online methods to dispose of e-waste than others with no or weaker willingness to do so. Additionally, residents’ e-waste online recycling intention had a significant positive effect on the implementation plan. This finding supports the results of the previous Carrington (2010) study on the difference between intention and behavior [

19]. Furthermore, it provides theoretical support for the subsequent examination of the mediators and moderators that make it difficult for residents to engage in online recycling behavior. E-waste online recycling platforms should implement various strategies to enhance residents’ willingness to recycle. Firstly, the platform can increase awareness of e-waste online recycling through education and promotion, emphasizing the importance of recycling for environmental protection and resource conservation. Secondly, incentives such as reward points, recycling discounts, or gamified experiences can effectively motivate residents to recycle. Additionally, the platform should leverage data analysis to understand residents’ recycling habits and needs, thereby offering personalized recommendations and support to further boost recycling motivation.

Second, implementation plans partially mediate the relationship between e-waste online recycling intention and actual recycling behavior. This suggests that, while enhancing users’ willingness to recycle, online recycling platforms can also enhance the predictive power of intention for subsequent actual participation behavior by prompting residents to develop a specific and detailed implementation plan. This result not only extends the application of the theoretical model proposed by Carrington (2010) but also provides a new path for existing online recycling platforms to attract residents to engage in actual recycling [

19]. E-waste online recycling platforms should prioritize helping urban residents develop specific recycling implementation plans. This study confirms that such plans predict actual recycling behavior better than intentions alone. Currently, online recycling companies focus on stimulating residents’ willingness to recycle, often resulting in mere downloads or registrations without action. Given the lengthy e-waste lifecycle, effective plans can clarify objectives, manage time, meet deadlines, and enhance success rates. Platforms should promote recycling’s environmental significance and resource value, improve convenience, and gather insights to offer personalized assistance, boosting residents’ conversion rates of recycling behavior.

Finally, both perceived value and platform interactivity positively moderated the relationship between the implementation plan and e-waste online recycling behavior. However, subjective norms and recycling convenience did not significantly moderate the path of the implementation plan in increasing participation. Based on this surprising result, this paper further tested the moderating variables and found that the positive moderating effects of certain intrinsic psychological factors and certain external situational factors were significant for both the intention-to-implement plan and intention-to-behavior paths. This suggests that, after residents establish a recycling implementation plan, convenience and subjective norms play a lesser role in actual recycling behavior but are more influential in transitioning from intention to implementation. Electronic products’ personal and emotional nature may lead residents to forgo recycling despite having a plan. Subjective social norms were more significant initially but are diminishing with the maturity of e-waste online recycling platforms [

30]. Online recycling firms should enhance e-waste recycling’s perceived value for residents, increasing plan translation into action. For platforms and residents, the act of recycling is not only a sustainable environmental behavior but also an economic behavior. Companies should aim to bring greater efficacy or value to residents and increase their perceived value of online recycling behaviors. On the one hand, enterprises can increase the perceived value through more reasonable price compensation or in-kind rewards to promote the conversion of intention to behavior. On the other hand, enterprises can publicize the subsequent use of recycled electronic products to visualize their environmental value, thus improving the predictive power of residents’ recycling implantation plan to behavior. Lastly, recycling companies need to enhance the interactivity of online recycling platforms. Platforms should ease information exchange and provide emotional support for e-waste online recycling. Improving information presentation and user experience can leave positive impressions, encouraging ongoing participation. Accessible recycling information, connections with recyclers, and a seamless recycling process foster sustained engagement.

5.2. Theoretical Contribution

Firstly, this study contributes to the research by examining the mechanism of transforming urban residents’ online recycling intention into behavior. The existing research, often based on the theory of planned behavior, assumes intention predicts recycling behavior. However, little attention is given to the gap between intention and behavior in e-waste recycling. Addressing this gap, the study constructs a theoretical model incorporating the implementation plan as a mediating variable. It explores its role in residents’ e-waste online recycling behavior, filling gaps in the current research.

Secondly, while previous studies have only focused on the direct influence of intrinsic psychological factors in the process of intention and behavior, this study uncovers the moderating influence of various psychological factors on residents’ online recycling participation. Building on the theoretical model of the intention–behavior gap, this study also highlights the moderating effect of perceived value between the implementation plan and online recycling behavior. It elucidates the intricate mechanism through which urban residents’ e-waste online recycling intentions translate into actions.

Finally, this study elucidates how external contextual factors shape residents’ online recycling participation behavior. Unlike traditional offline recycling, e-waste online recycling involves intricate online–offline interaction. However, current research has paid less attention to the unique characteristics of online recycling. This study investigates the moderating effects of recycling online platform interactivity and further clarifies the boundaries and conditions under which external contextual factors play a role.

5.3. Limitation

This study has some limitations that need to be further explored and improved. Firstly, in terms of data collection, this study primarily uses subjective evaluation methods to gather data. Although efforts were made to ensure rigor in the data collection process, such as anonymizing responses and using neutral language in the questionnaire design, issues related to social desirability bias and subjective judgments remain difficult to avoid. Additionally, data collected at a single point in time cannot dynamically reveal behavioral characteristics. Future research could consider employing experimental methods to control the research context or using reproducible data, such as app download statistics and online reviews, for variable measurement. Expanding the sample size and survey scope or conducting longitudinal tracking studies could also enhance the generalizability and dynamism of the research findings. Secondly, regarding the research content, we discussed the impact of intrinsic psychological factors and external environments on the implementation of the program and obtained some statistically significant results. However, the complexity of online and offline interactions has further dimensions that this study has not fully explored. Future research could consider factors such as switching costs and recycling habits for a more comprehensive analysis.