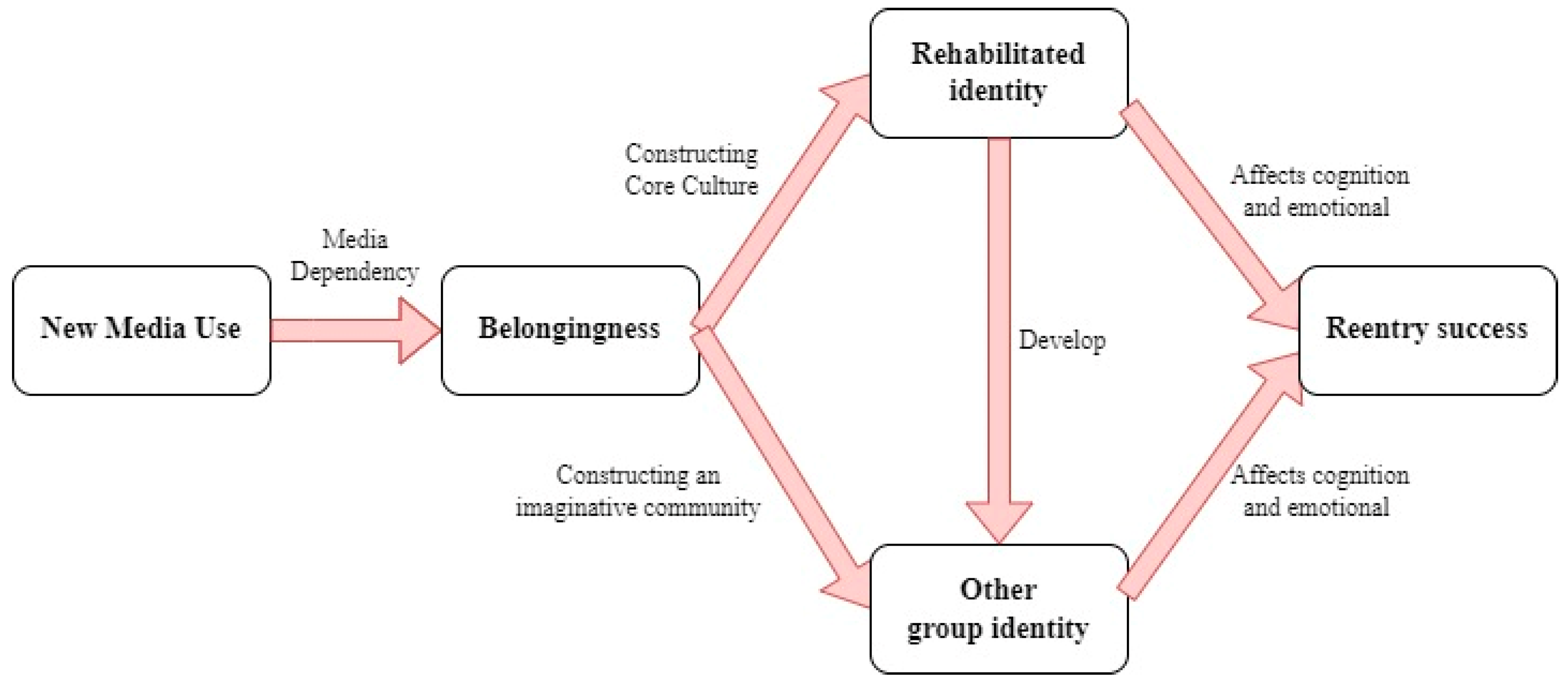

How Does New Media Shape the Sense of Belonging and Social Identity? The Social and Psychological Processes of Sustainable Successful Reintegration for Rehabilitated People

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Research Methodology

2.1.1. Narrative Study as a Research Paradigm

2.1.2. Methods of Data Collection

2.2. Literature Review and Materials

2.3. Main Theoretical Perspectives

2.4. Descriptions of the Interviewees

3. Results

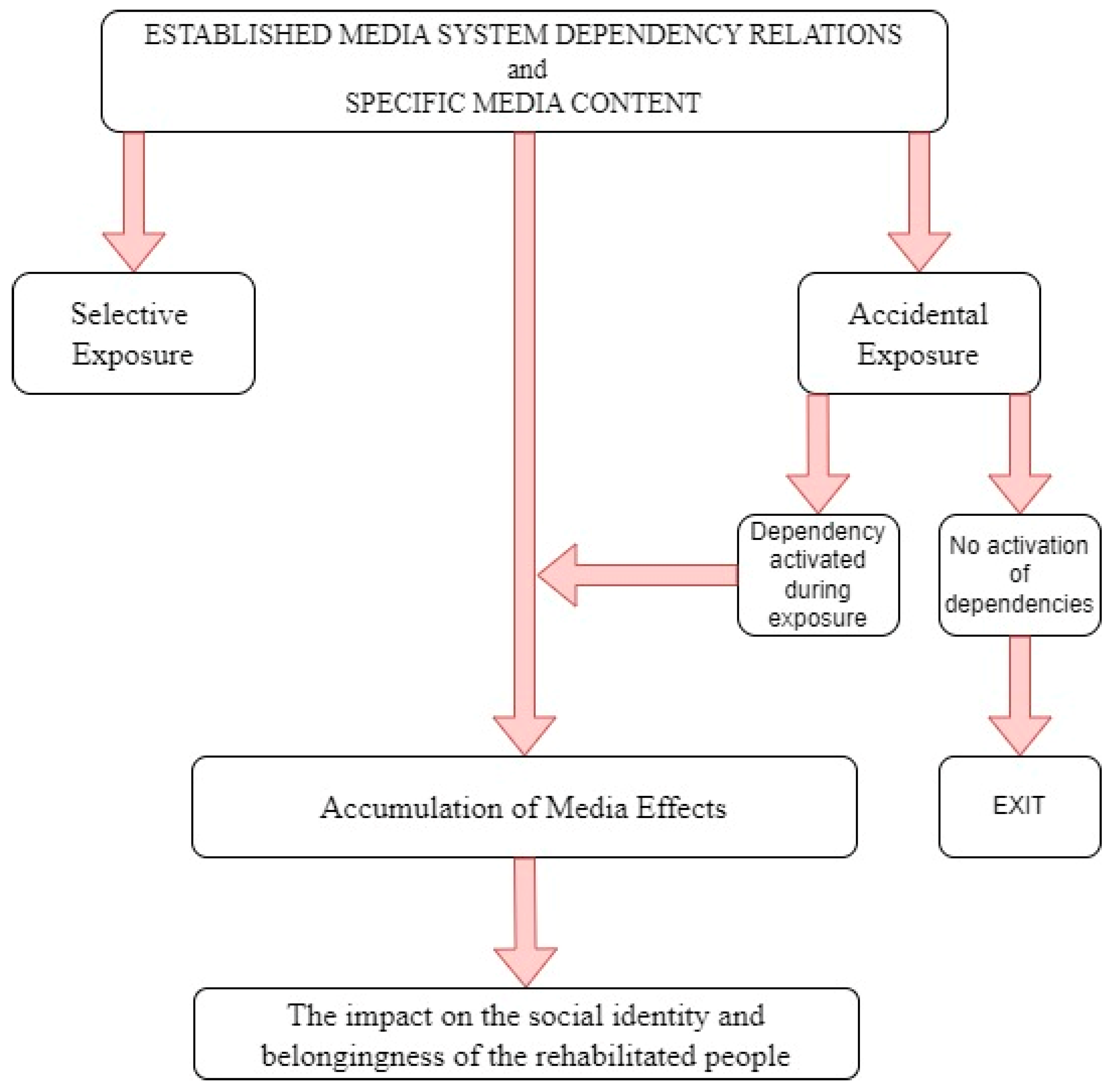

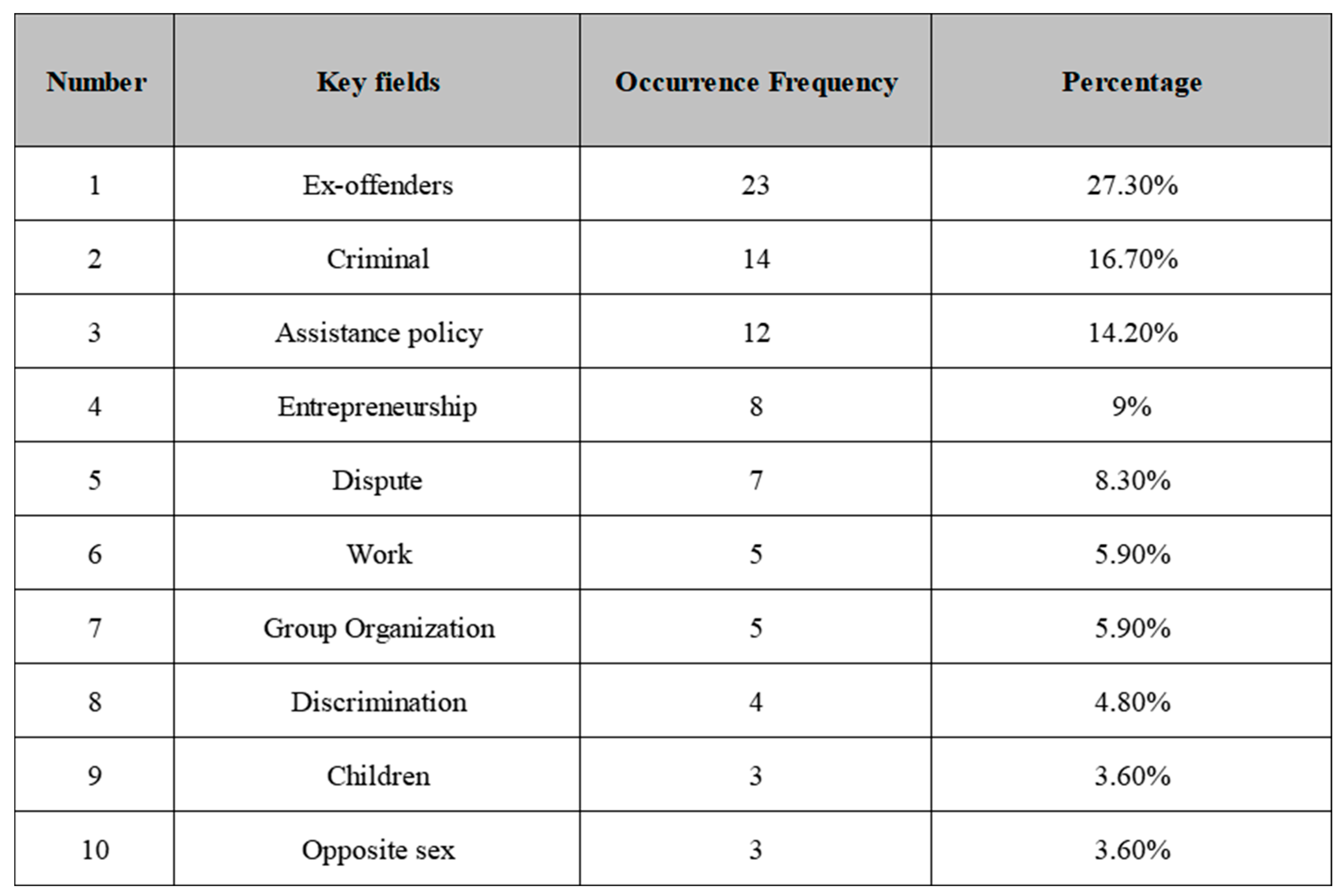

3.1. The Dynamic Media Dependency Process: The Media Systems of the Rehabilitated People

3.1.1. Selective Exposure: The Active Seeker

3.1.2. Accidental Exposure: The Passive Observer

3.1.3. Accumulation of Media Effects: The Senseless Recipient

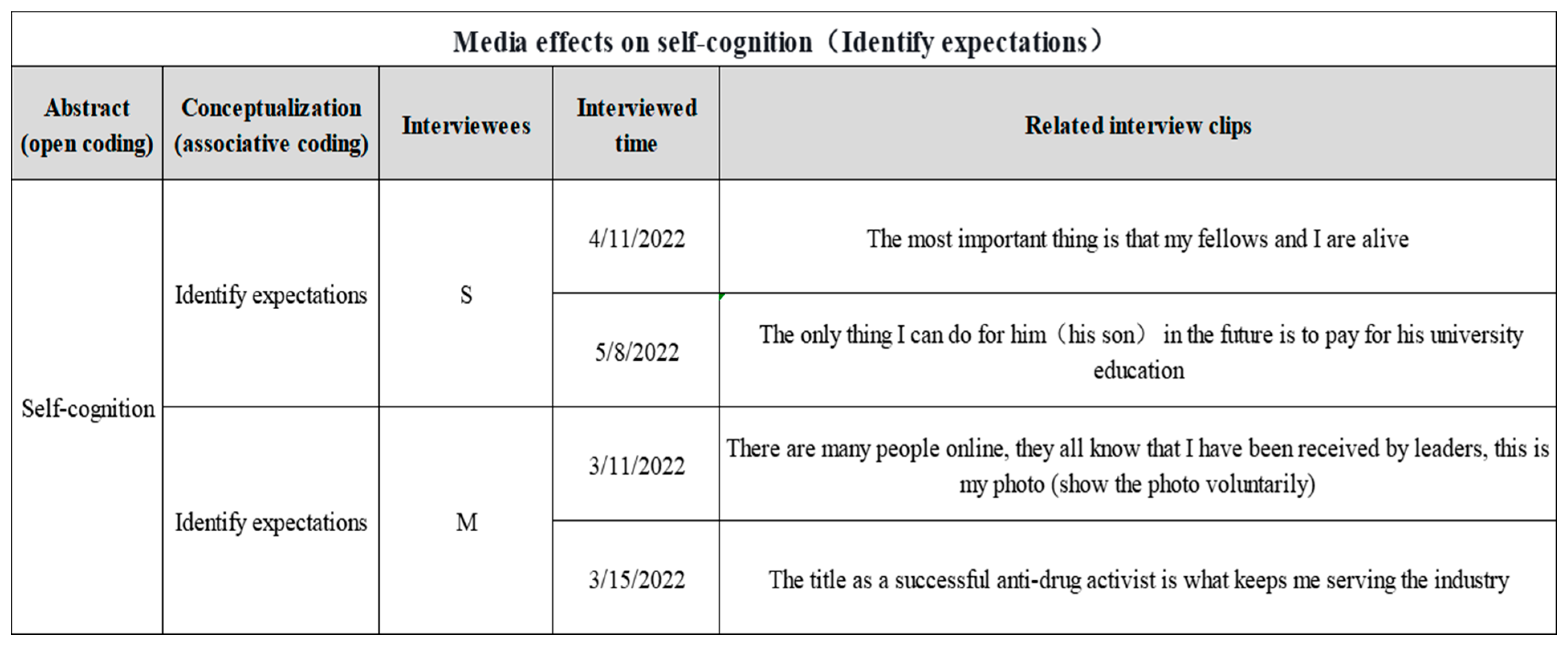

3.2. Identity Construction under Media Dependency: The Cognition, Emotion, and Behavior of the Rehabilitated People

3.2.1. Painful Memories: The Ambivalent Identity of the “Prisoner”

3.2.2. Opportunities for Positive Identification: Rehabilitated People under New Media

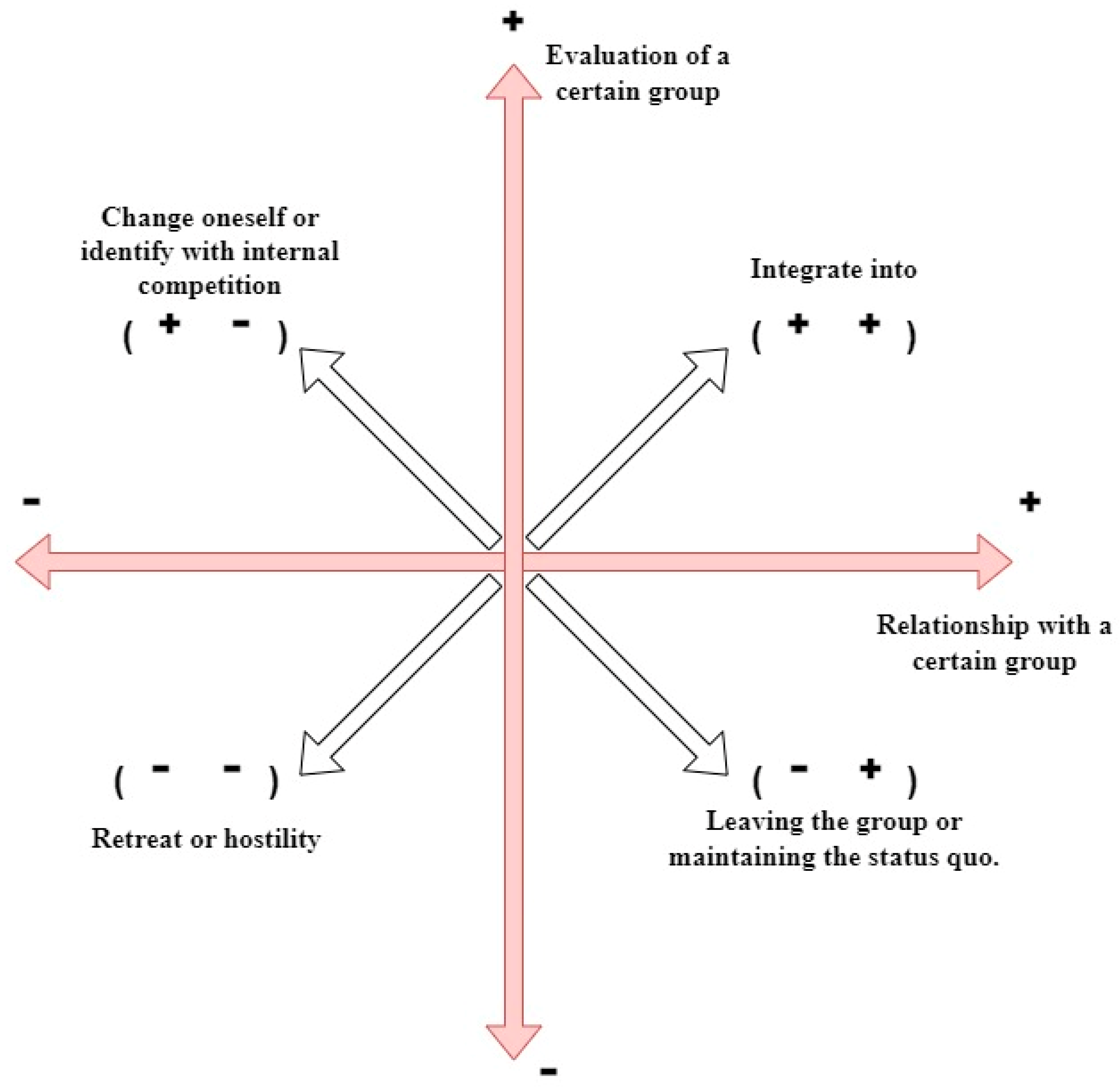

3.2.3. The Two-Dimensional Construction of Rehabilitated People’s Identity

3.2.4. The Development and Pluralism of the Rehabilitated Identity

4. Discussion

4.1. Overview

4.2. Conclusions and Political Recommendations

4.3. Future Research Potential

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Pękala-Wojciechowska, A.; Kacprzak, A.; Pękala, K.; Chomczyńska, M.; Chomczyński, P.; Marczak, M.; Kozłowski, R.; Timler, D.; Lipert, A.; Ogonowska, A.; et al. Mental and physical health problems as conditions of ex-prisoner re-entry. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2021, 18, 7642. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, R.; Wang, M.S.; Toubiana, M.; Greenwood, R. Stigma beyond levels: Advancing research on stigmatization. Acad. Manag. Ann. 2021, 15, 188–222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carson, E.A.; Anderson, E. Prisoners in 2015; NCJ 250229; U.S. Department of Justice: Washington, DC, USA, 2016.

- Jeffries, S.; Chuenurah, C.; Russell, T. Expectations and experiences of women imprisoned for drug offending and returning to communities in Thailand: Understanding women’s pathways into, through, and post-imprisonment. Laws 2020, 9, 15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matthews, E. Peer-focused prison reentry programs: Which peer characteristics matter most? Incarceration 2021, 2, 2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boman IVJ, H.; Mowen, T.J. Building the ties that bind, breaking the ties that don’t: Family support, criminal peers, and reentry success. Criminol. Public Policy 2017, 16, 753–774. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Western, B.; Braga, A.A.; Davis, J.; Sirois, C. Stress and hardship after prison. Am. J. Sociol. 2015, 120, 1512–1547. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ortiz, J.M.; Jackey, H. The system is not broken, it is intentional: The prisoner reentry industry as deliberate structural violence. Prison J. 2019, 99, 484–503. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aldamen, Y. Understanding social media dependency, and uses and gratifications as a communication system in the migration era: Syrian refugees in host countries as a case study. Soc. Sci. 2023, 12, 322. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Youssef, E.; Medhat, M.; Alserkal, M. Investigating the Effect of Social Media on Dependency and Communication Practices in Emirati Society. Soc. Sci. 2024, 13, 69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ball-Rokeach, S.J.; Power, G.J.; Guthrie, K.K.; Waring, H.R. Value-framing abortion in the United States: An application of media system dependency theory. Int. J. Public Opin. Res. 1990, 2, 249–273. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pahl-Wostl, C.; Odume, O.N.; Scholz, G.; De Villiers, A.; Amankwaa, E.F. The role of crises in transformative change towards sustainability. Ecosyst. People 2023, 19, 2188087. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Halfmann, A.; Rieger, D. Permanently on call: The effects of social pressure on smartphone users’ self-control, need satisfaction, and well-being. J. Comput.-Mediat. Commun. 2019, 24, 165–181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ike, T.J.; Jidong, D.E.; Ike, M.L.; Ayobi, E.E. Public perceptions and attitudes towards ex-offenders and their reintegration in Nigeria: A mixed-method study. Criminol. Crim. Justice 2023. [CrossRef]

- Jackson, L.A.; Kyriakopoulos, A.; Carthy, N. Criminal and positive identity development of young male offenders: Pre and post rehabilitation. J. Crim. Psychol. 2023, 13, 173–189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mertl, J. What seems to be the problem? Ex-prisoners’ reentry/resettlement in the Czech Republic. Crime Delinq. 2024, 70, 1993–2016. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baffour, F.D.; Francis, A.P.; Chong, M.D.; Harris, N.; Baffour, P.D. Perpetrators at first, victims at last: Exploring the consequences of stigmatization on ex-convicts’ mental well-being. Crim. Justice Rev. 2021, 46, 304–325. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paat, Y.F.; Hope, T.L.; Zamora, H.; Lopez, L.C.; Salas, C.M. Inside the lives of Mexican origin ex-convicts: Pre- and post-incarceration. Int. J. Crime Justice Soc. Democr. 2018, 7, 83–99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matthews, E.; Bowman, R.; Whitbread, G.; Johnson, R.D.C. Central Kitchen: Peer mentoring, structure and self-empowerment play a critical role in desistance. J. Offender Rehabil. 2020, 59, 22–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, Y. Thwarted belongingness hindered successful aging in Chinese older adults: Roles of positive mental health and meaning in life. Front. Psychol. 2022, 13, 839125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- González, P.A.; Dussaillant, F.; Calvo, E. Social and individual subjective wellbeing and capabilities in Chile. Front. Psychol. 2021, 11, 628785. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mayor, E. Nonverbal immediacy mediates the relationship between interpersonal motives and belongingness. Front. Sociol. 2020, 5, 596429. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pardede, S.; Gausel, N.; Høie, M.M. Revisiting the “the breakfast club”: Testing different theoretical models of belongingness and acceptance (and social self-representation). Front. Psychol. 2021, 11, 604090. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- McEwan, B.; Sumner, E.; Eden, J.; Fletcher, J. The effects of Facebook relational maintenance on friendship quality: An investigation of the Facebook relational maintenance measure. Commun. Res. Rep. 2018, 35, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, J.Y. A study of social media users’ perceptional typologies and relationships to self-identity and personality. Internet Res. 2018, 28, 767–784. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pan, Z.; Lu, Y.; Wang, B.; Chau, P.Y. Who do you think you are? Common and differential effects of social self-identity on social media usage. J. Manag. Inf. Syst. 2017, 34, 71–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gentile, B.; Twenge, J.M.; Freeman, E.C.; Campbell, W.K. The effect of social networking websites on positive self-views: An experimental investigation. Comput. Hum. Behav. 2012, 28, 1929–1933. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, C.; Bradford Brown, B. Online self-presentation on Facebook and self development during the college transition. J. Youth Adolesc. 2016, 45, 402–416. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Latif, K.; Weng, Q.; Pitafi, A.H.; Ali, A.; Siddiqui, A.W.; Malik, M.Y.; Latif, Z. Social comparison as a double-edged sword on social media: The role of envy type and online social identity. Telemat. Inform. 2021, 56, 101470. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Keita, S.; Renault, T.; Valette, J. The usual suspects: Offender origin, media reporting and natives’ attitudes towards immigration. Econ. J. 2024, 134, 322–362. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Connelly, F.M.; Clandinin, D.J. Stories of experience and narrative inquiry. Educ. Res. 1990, 19, 2–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bruner, J. The narrative construction of reality. Crit. Inq. 1991, 18, 1–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McNamee, S. Research as relational practice: Exploring modes of inquiry. In Systemic Inquiry: Innovations in Reflexive Practice Research; Everything is Connected Press: Farnhill, UK, 2014; pp. 74–94. [Google Scholar]

- Puppis, M. Analyzing talk and text I: Qualitative content analysis. In The Palgrave Handbook of Methods for Media Policy Research; Palgrave Macmillan: Basingstoke, UK, 2019; pp. 367–384. [Google Scholar]

- McQuail, D.; Windahl, S. Communication Models for the Study of Mass Communications; Routledge: London, UK, 2015; pp. 187–190. [Google Scholar]

- Tajfel, H. Social identity and intergroup behaviour. Soc. Sci. Inf. 1974, 13, 65–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scholz, G.; Wijermans, N.; Paolillo, R.; Neumann, M.; Masson, T.; Chappin, É.; Templeton, A.; Kocheril, G. Social agents? A systematic review of social identity formalizations. J. Artif. Soc. Soc. Simul. 2023, 26, 6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scholz, G.; Eberhard, T.; Ostrowski, R.; Wijermans, N. Social Identity in Agent-Based Models—Exploring the State of the Art. In Proceedings of the Conference of the European Social Simulation Association, Mainz, Germany, 23–27 September 2019; Springer International Publishing: Cham, Switzerland, 2019; pp. 59–64. [Google Scholar]

- Mattingly, B.A.; Lewandowski, G.W., Jr.; McIntyre, K.P. “You make me a better/worse person”: A two-dimensional model of relationship self-change. Pers. Relatsh. 2014, 21, 176–190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cameron, J.E. A three-factor model of social identity. Self Identity 2004, 3, 239–262. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nixon, S. ‘Giving back and getting on with my life’: Peer mentoring, desistance and recovery of ex-offenders. Probat. J. 2020, 67, 47–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hogg, M.A.; Turner, J.C. Intergroup behaviour, self-stereotyping and the salience of social categories. Br. J. Soc. Psychol. 1987, 26, 325–340. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Best, D.; Lubman, D.I.; Savic, M.; Wilson, A.; Dingle, G.; Haslam, S.A.; Haslam, C.; Jetten, J. Social and transitional identity: Exploring social networks and their significance in a therapeutic community setting. Ther. Communities Int. J. Ther. Communities 2014, 35, 10–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wijermans, N.; Scholz, G.; Chappin, É.; Heppenstall, A.; Filatova, T.; Polhill, J.G.; Semeniuk, C.; Stöppler, F. Agent decision-making: The Elephant in the Room-Enabling the justification of decision model fit in social-ecological models. Environ. Model. Softw. 2023, 170, 105850. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chadwick, A. The Hybrid Media System: Politics and Power; Oxford University Press: Oxford, UK, 2017; pp. 34–58. [Google Scholar]

- Puglisi, R.; Snyder, J.M., Jr. Empirical studies of media bias. In Handbook of Media Economics; North-Holland: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2015; Volume 1, pp. 647–667. [Google Scholar]

- Cohen, A.P. Symbolic Construction of Community; Routledge: London, UK, 2013; pp. 87–135. [Google Scholar]

- Jenkins, R. Social Identity; Routledge: London, UK, 2014; pp. 11–83. [Google Scholar]

- Anderson, B.R.O.G. Comunitats Imaginades: Reflexions Sobre L’origen i la Propagació del Nacionalisme; Universitat de València: Valencia, Spain, 2005; pp. 24–89. [Google Scholar]

- Zhuravskaya, E.; Petrova, M.; Enikolopov, R. Political effects of the internet and social media. Annu. Rev. Econ. 2020, 12, 415–438. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rauch, J. Superiority and susceptibility: How activist audiences imagine the influence of mainstream news messages on self and others. Discourse Commun. 2010, 4, 263–277. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, C.; Lee, M.K.O.; Hua, Z. A theory of social media dependence: Evidence from microblog users. Decis. Support Syst. 2015, 69, 40–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lutz, S.; Schneider, F.M. Is receiving dislikes in social media still better than being ignored? The effects of ostracism and rejection on need threat and coping responses online. Media Psychol. 2021, 24, 741–765. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lutz, S. Why don’t you answer me?! Exploring the effects of (repeated exposure to) ostracism via messengers on users’ fundamental needs, well-being, and coping motivation. Media Psychol. 2023, 26, 113–140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vogel, E.A.; Rose, J.P.; Roberts, L.R.; Eckles, K. Social comparison, social media, and self-esteem. Psychol. Pop. Media Cult. 2014, 3, 206–222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Xiao, L.; Chu, F.; Mao, J.; Yang, J.; Liu, Z. How Does New Media Shape the Sense of Belonging and Social Identity? The Social and Psychological Processes of Sustainable Successful Reintegration for Rehabilitated People. Sustainability 2024, 16, 7958. https://doi.org/10.3390/su16187958

Xiao L, Chu F, Mao J, Yang J, Liu Z. How Does New Media Shape the Sense of Belonging and Social Identity? The Social and Psychological Processes of Sustainable Successful Reintegration for Rehabilitated People. Sustainability. 2024; 16(18):7958. https://doi.org/10.3390/su16187958

Chicago/Turabian StyleXiao, Liyao, Fufeng Chu, Jingjing Mao, Jiaxin Yang, and Ziyu Liu. 2024. "How Does New Media Shape the Sense of Belonging and Social Identity? The Social and Psychological Processes of Sustainable Successful Reintegration for Rehabilitated People" Sustainability 16, no. 18: 7958. https://doi.org/10.3390/su16187958

APA StyleXiao, L., Chu, F., Mao, J., Yang, J., & Liu, Z. (2024). How Does New Media Shape the Sense of Belonging and Social Identity? The Social and Psychological Processes of Sustainable Successful Reintegration for Rehabilitated People. Sustainability, 16(18), 7958. https://doi.org/10.3390/su16187958