Abstract

In the context of Disease X risks, how governments and public health authorities make policy choices in response to potential epidemics has become a topic of increasing concern. The tightness of epidemic prevention policies is related to the effectiveness of the implementation of measures, while the organizational cognition of epidemic risks is related to the rationality of policy choices. During the three years of COVID-19, the Chinese government constantly adjusted the tightness of its prevention policies as awareness of the epidemic risk improved. Therefore, based on the epidemic risk organizational cognition model, the key nodes that affect the tightness of epidemic prevention policies can be explored to find the organizational behavior rules behind the selection of prevention policies. Firstly, through observing the adjustments made to the Chinese government’s prevention strategies during the epidemic, a time-series cross-case comparative analysis reveals how policy tightness shifted from stringent to lenient. This shift coincided with the organizational cognition of epidemic risk evolving from vague to clear. Secondly, by building the “knowledge-cognition” coordinate system to draw the organizational cognition spiral of epidemic risk, it is clear that the changes in the tightness of the prevention policies mainly came from the internalization and externalization of knowledge such as epidemic risk characteristics to promote the level of organizational cognition, which is manifested as expansion and deepening. Thirdly, the node changes in the interaction between organizational cognition development and policy choice proved that different stages of the epidemic had diverse environmental parameters. Moreover, as the epidemic nears its end, the focus of policy tightness is shifting from policy objectives to policy implementation around governance tools. The results indicate that organizational cognition of epidemic risk exhibits significant stages and periodicity. Additionally, epidemic risk characteristics, environmental coupling, and governance tools are crucial factors in determining the tightness of epidemic prevention policies.

1. Introduction

The sustainability of organizational operation is an important research direction in organizational behavior [1]. It is a key task for public health organizations to adjust the leniency of epidemic prevention and control measures to ensure the sustainability of organizational behavior. In early 2024, WHO Director-General Tedros Adhanom Ghebreyesus [2] issued a public warning about the possibility of an outbreak of Disease X, which is not a specific disease but an infectious disease caused by an unknown pathogen that could lead to a global pandemic [3]. In this context, it is necessary to conduct a comprehensive review of the COVID-19 pandemic in previous years, identify key items affecting the rigor of epidemic prevention and control policies, and explore their role in the sustainable development of public health organizations from the perspective of organizational cognition. In 2020, the Chinese government classified COVID-19 as a Class B infectious disease but managed it as a Class A, authorizing local authorities to impose a lockdown and other restrictions [4]. How to formulate the decision-making mechanism of epidemic prevention policy selection became a major research topic in public policy management at that time. Therefore, in the face of the possible threat of Disease X, the ability to form a scientific and efficient dynamic epidemic control policy is particularly critical, and organizational cognition [5], as an important driving force for policy adjustment, has become a research path with which to explore this issue.

From December 2019 to December 2022, the COVID-19 epidemic continued to fluctuate in China. From the perspective of organizational cognition, Chinese public health organizations’ perceptions of epidemic risk had shifted from vague to clear during the Wuhan epidemic, from clear to precise during the Shanghai epidemic, and from specific to comprehensive during the winter epidemic in 2022. Influenced by the organizations’ perceptions, from the perspective of policy flexibility, the Chinese government’s epidemic risk prevention policy has shifted from initial comprehensive tight control to mid-term precise tight control, and then to comprehensive relaxation. In the course of a relatively complete epidemic life cycle, the epidemic risk cognition of public health organizations continues to evolve and develop, and the prevention policy choices of epidemic risk continue to adjust accordingly. The study aims to explore the organizational behavioral laws of public health organizations in adjusting the tightness of epidemic prevention policies, so as to provide proactive theoretical groundwork for the increasing possibility of a widespread Disease X pandemic. To accomplish this aim, the study sets out the following objectives: first, to reveal how prevention policy tightness shifted from stringent to lenient in the COVID-19 epidemic with a time-series cross-case comparative analysis; second, to construct a “knowledge-cognition” binary coordinate system and plot the spiral curve of organizational cognition for epidemic risk by using conceptual modeling; third, to identify crucial process intersections of organizational cognition and policy selection, and to explicit the different impacts of the nodes on the choice of policy tightness at different stages of the epidemic.

2. Literature Review

With the development of the global social economy, while embracing the new era, human beings have also entered a risk society where various complex emergencies cross over. Three years of regular epidemic prevention shows that public policies involve all aspects of society and affect almost everyone’s daily life.

2.1. Research on Public Policy Choice

Public policy is a set of related decisions made by public organizations and their behavioral subjects in specific situations. In principle, these policies are within the capacity of the action subjects [6], which are mainly manifested as public value orientation, public problem orientation, and public power enforcement. In the practice of COVID-19 prevention, how to select appropriate policy tools according to the risk situation of the epidemic and socioeconomic situation has become a hot topic, so policy selection has become a major issue of research in related fields.

- In terms of the participants of policy choice, it has become a consensus that multi-agent participation supports the rationality of policy choice, and active participation incentive and function matching as well as participants’ risk perception ability and knowledge level have positive effects on multi-participation [7,8,9];

- In terms of the basis for policy selection, the determination of epidemic prevention policies not only relies on sufficient and abundant relevant information but also depends on the characteristics of policy objects, the background of policy implementation, and the support of various regulatory mechanisms [10,11,12];

- In terms of the process of policy selection, the general process mainly includes environment and object evaluation, system cost evaluation, and policy tool simulation, among which the opening and evolution of the policy selection process are not only affected by object positioning but also by stakeholders [13,14,15];

- In terms of tools for policy choice, scholars have conducted objective and specific discussions on such policy choice tools such as information tools, technology tools, and regulation tools based on specific cases, including not only the tool choice mode of m/n but also the tool combination mode of Cnm [16,17,18].

2.2. Research on Organizational Cognition

Due to the increase in uncertainty and the risk amplification effect in modern society, the internal perception displayed by organizations may affect the choice of risk prevention policies, and such complex and diversified risk perception formed in different social backgrounds is organizational cognition [19]. In addition to the influence of individual knowledge conservation, perceptual experience and value orientation also play an important role [20]. At the same time, the combined effects of social environment, cultural background, individual attitude, and other factors can enhance or weaken organizational risk perception (see Table 1).

Table 1.

Summary of research views on organizational cognition.

First of all, under the social amplification effect of risk, the participants of organizational risk cognition are diversified [21]. The individual characteristics, heterogeneity, and power structure of the main team will affect organizational cognition [22,23]. Secondly, organizational cognition is the process from internalization to externalization of the shared mind of organizational members [24], wherein active and sufficient organizational communication plays a positive role in the learning and transformation of the shared emotional journey and knowledge information of members in the process of organizational cognition [25], while distributed cognition of organization members plays a special role of decoupling in the formation of organizational cognition [26]. Thirdly, the interactive atmosphere of risk preference, value orientation, and emotional attitude jointly determines the overall trend of organizational cognition [27]. For example, collectivist organizational culture can strengthen the positive relationship between members and leaders [28]. It mainly includes collective cognition, organizational learning, shared mind, interactive memory, and psychological climate [29]. Finally, internal and external environmental factors will affect organizational cognition, among which the intensity of external risks will significantly stimulate the enthusiasm of organizational cognition [30]. Organizational cognition guided by senior managers should take the initiative to respond to the constantly dynamic external environment [31], and the organization’s experiences will help to form good new cognition in an abnormal environment or crisis situation [32].

To sum up, in the epidemic risk management scenario, policy selection refers to the process of multiple subjects selecting and combining various policy tools such as regulation, technology, and information based on various supporting mechanisms on the premise of mastering epidemic risk information. Organizational cognition is the perception and judgment of epidemic risk formed by organizations under the dual influence of individual and social environments. To promote survival and development, the organizations will constantly deal with various external information, actively absorb external information, respond to changes in the external environment, and constantly adjust their own practices to adapt to various changes in information from the external environment, with organizational crisis learning behavior being the link between the two [33]. In order to better explore this process, this study will build an interactive model of organizational cognition and policy choice based on multi-case comparative analysis.

3. Epidemic Prevention Policy Selection in the Evolution of Organizational Cognition

3.1. Research Design

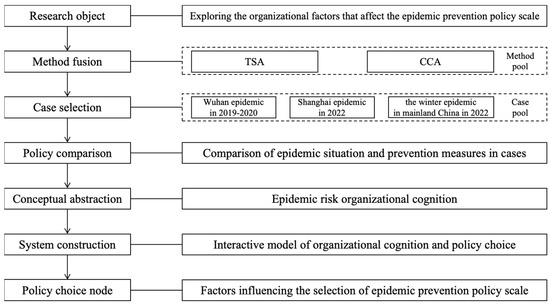

As shown in Figure 1, this study aims to explore the organizational factors that affect the scale of epidemic prevention policies. Utilizing CCA and TSA as the methodological approach, we selected three distinct epidemic cases for comparison: the Wuhan epidemic of 2019–2020, the Shanghai epidemic of 2022, and the winter epidemic in mainland China in 2022. Through a conceptual abstraction process, the concept of “Epidemic Risk Organizational Cognition” was derived and an interactive model of organizational cognition and policy choice was constructed. Then, the factors influencing the selection of epidemic prevention policy scales were identified through analysis of the policy choice node.

Figure 1.

Research process design.

3.1.1. Fusion of Methods

This study requires a combination of qualitative methods. Policy measures are often formulated and implemented in a specific context, and over time, they may produce different effects, so time series analysis can be selected to reveal the law of this process. Cross-case comparative analysis, as a qualitative analysis method, can directly show the similarities and differences in policy choices in different epidemic cases.

- Time series analysis (TSA) decomposes an event into trend, cycle, period, and unstable factors. It emphasizes the extraction of relevant event features and the analysis of its change process and development mode through continuous observation of a region within a certain period of time [34].

- Cross-case comparative analysis (CCA) would be used to explore the common factors and individual factors in epidemic risk organizational cognition by sorting out the homogeneous elements and the heterogeneous elements in different cases [35].

Although TSA can show the time process, it can only consider the same sample index. Although CCA can compare the characteristics of different case events, it cannot investigate their time development attributes. Therefore, this paper combines TSA and CCA and uses temporal cross-case comparative analysis (TSCCA) to explore the ontological event characteristics and the evolution of policy selection in different phases of the epidemic.

3.1.2. Case Selection

The Wuhan epidemic in 2019–2020, the Shanghai epidemic in 2022, and the winter epidemic in mainland China in 2022 are selected as study cases. Firstly, the selection of cases should be sequential, and the case events should be selected according to the time series of the outbreak. The three alternative cases are located at the beginning, middle, and end of the whole life cycle of the epidemic, respectively, and the development process of the epidemic risk organization cognition and the characteristics of policy selection in different stages can be investigated. Secondly, the selection of cases should be comparable. The spaces where the cases were located not only had similar social and economic functions and population characteristics but also relatively consistent administrative management modes, so the impact of noise can be eliminated as far as possible. Finally, the selection of cases should be representative, and the three cases are significantly representative of the whole epidemic cycle. The Wuhan epidemic is at the beginning of the cycle, and awareness of the prevention policy of emerging infectious diseases shifts from vague to clear; the Shanghai epidemic is at the stage of normal control, and risk awareness and institutional oversight are typical of normal prevention. The winter of 2022 was the period with the highest number of COVID-19 infections in China since the outbreak, and changes in various epidemic data have guided the adjustment of policy choices.

3.2. Selection Process of Epidemic Risk Prevention Policy

The information and characteristic attributes of moderate epidemic risk prevention policy selection in the three cases were summarized (see Table 2). In terms of the temporal and spatial attributes of the policy choices, the three epidemic prevention policy choices were respectively made at the early, middle, and late stages of the epidemic life cycle.

Table 2.

Epidemic characteristics and prevention policies in cases.

The Lockdown and Static Management in the first two cases were regional decisions made by the local government based on the urgency of the local epidemic risk prevention situation. Class as B and Treat as B is a policy change made by the central government based on the latest epidemic prevention control situation research. From the perspective of policy features and functions, the initial lockdown strategy did not have clear institutional arrangements in the early stages. It was a temporary prevention strategy implemented by mandatory administrative orders, with the sole goal of stopping the transmission path of epidemic risk. Later, this mode of prevention was institutionalized into a static management mode covering the whole region, and each region formulated a specific disposal plan according to its own situation, in addition to preventing risks to ensure the normal order of social livelihood [36].

At the end of the epidemic, with major changes in the characteristics of the epidemic, the competent ministries changed the focus of prevention to key groups and social and economic recovery by revising the overall epidemic prevention plan. In terms of policy implementation consequences and tightness, according to the time order, the policy tightness in the three cases is reflected in the process of tightening to loosening, among which the closed prevention mode of full static management is in the critical period of the transformation of epidemic characteristics [37].

3.3. Stage Division of Epidemic Risk Organizational Cognition

According to the case analysis, it can be seen that in different periods of the COVID-19 epidemic, the governing bodies responded to the epidemic with different policy tightness. On the one hand, the level of organizational cognition will continue to improve with the expansion of knowledge breadth and depth. On the other hand, it also fluctuates according to the change in governance and cognitive environment, that is, the cognitive level increases when the cognition adapts to the environment and the cognitive level decreases when the cognition does not adapt to the environment.

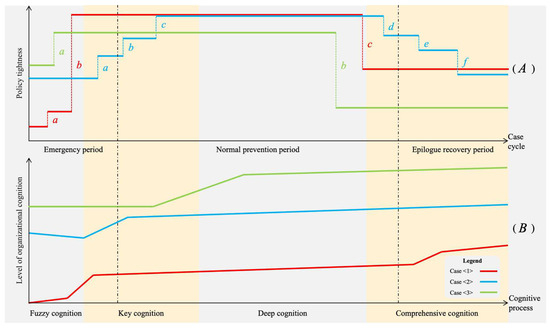

In this process, policy tightness, as an explicit indicator, showed non-linearity in the epidemic cycle (see Figure 2) for two main reasons. First, epidemic prevention and control policies mainly came from administrative orders and existing regulations, which were mandatory, so they showed a transition in policy tightness at a certain point in time. Second, epidemic risk prevention and control policies need to be adjusted according to the change in risk situation. Therefore, in the face of existing risks, there will not only be a tightening of policy in severe situations but also policy easing in a slowing situation.

Figure 2.

Organizational cognition stage of epidemic risk based on the policy choice process. (A) The epidemic prevention policies tightness curves in the three cases are shown in stages; (B) The epidemic risk organizational cognition curves in the three cases are shown in stages.

- Red Curve: Discontinuity point (a) comes from the government’s advocacy for residents to maintain good health habits in public places, which belongs to the guiding policy; discontinuity point (b) is derived from the formal definition of the human-to-human transmission characteristics of COVID-19, which is manifested as the implementation of a Lockdown in Wuhan; discontinuity point (c) stems from the initial solution of the early epidemic and the “lifting of the lockdown” strategy, but it still maintains a policy tightening far beyond that before the outbreak of the epidemic.

- Blue Curve: Discontinuity point (a) comes from a series of closed control measures according to the emergency plan because of the fact that the key units were affected by the imported epidemic; discontinuity points (b,c) originated from the Static Management in Shanghai after the sharp increase in the number of infections and deaths, which has the hierarchical and classified attributes; discontinuity points (d,e,f) come from the step-by-step lifting of the Static Management, but in order to continue to control the epidemic risk, the policy tightness remains at a relatively high position.

- Green Curve: discontinuity point (a) originated from the quickly implemented risk hierarchical control and dynamic zero clearance strategy for responding to the winter epidemic on the Chinese mainland in 2022, so the curve after the discontinuity point is slightly lower than that of the first two cases; discontinuity point (b) originated from the Category B and B control policies issued by the National Health Commission. Because the epidemic situation and virus characteristics at that time were comprehensively analyzed and judged, the intensity of the new mutant virus dropped significantly [38].

According to the discontinuity points in the policy tightness curve in Figure 2, it can be found that the epidemic risk prevention and control process in the three epidemic cases can be divided into the policy selection process, including the emergency response period, the risk prevention and control period, and the end recovery period. According to the stages of the policy selection process, four stages of organizational cognition of epidemic risk can be obtained.

- In the fuzzy cognition stage, for the new epidemic, the cognition level is positively correlated with the time course. However, due to the lack of control over the epidemic situation and virus information, the slope of the curve is small. For the late-onset epidemic, due to changes in the background such as virus mutation, social and economic impact, and the resilience of disaster-bearing bodies, the cognition of epidemic risk organizations shows a certain degree of inadaptation [39], so the cognition curve decreases.

- In the key cognition stage, with the progress of the epidemic in Wuhan and Shanghai and the enrichment of relevant information, organizational cognition on the risk of the epidemic began to evolve, which was reflected in the improvement of the slope of the cognition curve, that is, the curve had an inflection point.

- In the stage of deepening cognition, since the change in the direction of policy choice in the winter of 2022 is an innovation, it takes a longer and more stable time to analyze the risk situation of the epidemic. Therefore, the inflection points in the third case occurred at the stage of deepening cognition. The overall cognitive performance of the epidemic prevention model in the latter two cases was gradually internalized as part of the organizational culture.

Based on the cognitive process of epidemic risk organizations obtained in the case comparison, we can further explore the process mechanism of epidemic risk organizational cognition and the key nodes for cognition to guide policy choices.

4. Organizational Cognition Nodes of Epidemic Risk Based on the Knowledge—Cognition Dimension

Looking back at the process of regular epidemic prevention and control in the past three years, risk prevention and control policies have gone through a cycle from loose to tight and then loose. Therefore, it is necessary to abstract the organizational cognition stage in the original case to explore the general process of organizational cognition of epidemic risk, namely the key nodes, and provide a theoretical tool for the possible future epidemic risk and the upgrading direction of organizational cognition.

4.1. Organizational Cognition Process of Epidemic Risk

4.1.1. Dimensions of Cognition and Knowledge

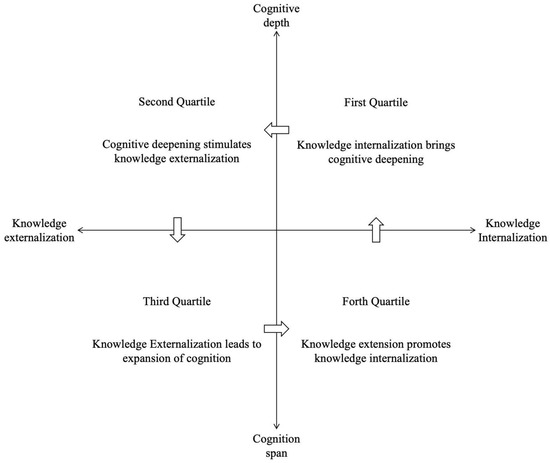

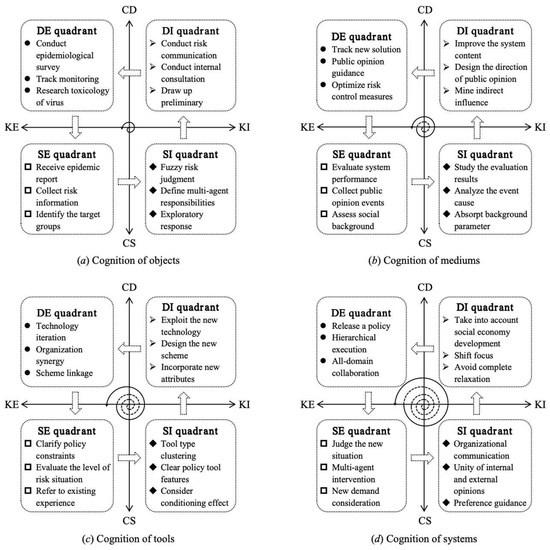

Cognitive process theory divides cognitive levels into breadth and depth [40]. The breadth of epidemic risk organization cognition is mainly related to the scope of epidemic risk knowledge and information. In the process of epidemic prevention and control, there will not only be many traditional risk types but also some new risk sources and risk transmission channels with the emergence of new epidemics. In the limited response time, the organization should first grasp the necessary knowledge. At the same time, the depth of organizational cognition of epidemic risk is mainly related to the essential characteristics and development laws of epidemic risk (see Figure 3).

Figure 3.

Cross-coordinate system of the cognitive dimension and knowledge dimension.

The study of organizational behavior divides the knowledge transformation behavior on which the improvement of organizational capability depends into two modes: knowledge internalization and knowledge externalization [41]. In the process of crisis learning of organizational cognition, this behavior is mainly divided into the upgrading and supplementing of knowledge and skills, the forward-looking understanding of the epidemic risk situation, and the strengthening of the epidemic knowledge system [42]. In the process of knowledge transformation, the organization first internalizes the organizational behavior basis by absorbing experience and then feeding back into epidemic risk prevention and control practice. It can be seen that the process of deep and broad expansion of cognition and the process of internalization and transformation of knowledge are both shown as spiral cycle modes.

4.1.2. Organizational Cognitive Spiral Balanced by Knowledge and Cognition

Knowledge internalization refers to the experience and lessons absorbed by the organization from management of the epidemic, which are integrated into its own institutional goal relationship attributes through the organizational mechanism and become the shared mind that members of the organization must abide by. Knowledge externalization refers to the application of internalized knowledge as organizational cognition to the outside of the organization, such as in the practice of epidemic risk management, to find problems and seek opportunities for cognitive evolution and improvement [43]. As shown in Figure 3, the generation and development process of organizational cognition is the process of the continuous spiral development of the organizational cognition level around the internalization and externalization of knowledge. Among them, the horizontal axis refers to the knowledge dimension, and organizational learning behavior is divided into two processes of internalization and externalization of knowledge through the origin. The organizational cognitive level referred to by the vertical axis is endowed with the meaning of dynamic evaluation, that is, every time an organization experiences knowledge externalization, it will always find the inadaptability of the existing cognitive level, thus obtaining the goal of organizational cognitive development and promoting the curve of the organizational cognitive level to the next quadrant.

4.2. Key Nodes in the Organization Cognition Process of Epidemic Risk

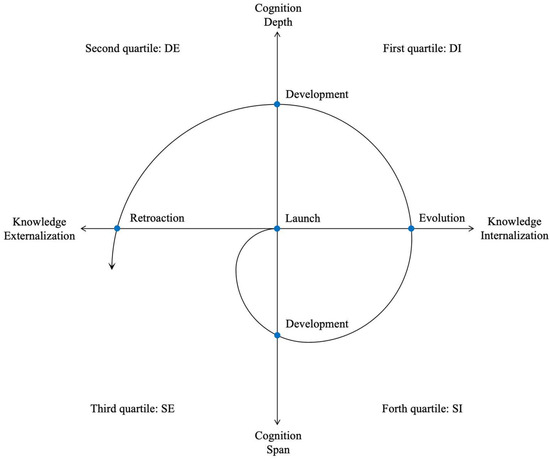

The generation and development of organizational cognition provide a logical starting point for better guiding organizational behavior, while the evolution and upgrading of organizational cognition provide a long-term mechanism for realizing the self-optimization of organizations. The key times of the three groups of epidemic cases can correspond to the nodes of the organizational cognitive spiral, thus forming a comparison table of organizational cognitive node information (see Table 3). Therefore, through the node information, event characteristics can be summarized in the whole organizational cognitive cycle and four types of key nodes can be summarized, namely, the startup node, the development node, the evolution node, and the feedback node (see Figure 4).

Table 3.

Information of epidemic risk organization cognition nodes in the cases.

Figure 4.

One-period model of organizational cognition.

- Cognitive initiation node: The risk preference, personal characteristics, and professional ability of the management will dominate the cognitive priming. The overall risk cognition level and execution ability of grass-roots members determine the realization of organizational risk management performance. The relationship attributes, process mechanism, and resource matching of organizational operations restrict the initiation efficiency of organizational cognition. In Case <1>, organizational cognition initiation comes from the normal epidemic risk monitoring and reporting mechanism. The existing organizational culture rich in awareness of innovation, risk, and development is not only reflected in explicit rules and regulations (such as the emergency plan launched in Case <2>) but also in the implicit organizational atmosphere (such as the precipitation of the concept of precise epidemic prevention in each organization in Case <3>). The stimulation of external factors is reflected in the following two aspects: the organizational needs are internalized in the operation of the organization, and the organization tracks and evaluates the changes in various social and economic fields based on the policy goals and guides the cognitive direction. For example, in Case <1>, the government started the organizational cognitive upgrading in response to the unknown pneumonia epidemic.

- Cognitive development node: Cognitive development nodes come from the intersection of the organizational cognitive spiral and cognitive breadth and depth. When organizations perceive epidemic risk information for the first time, they should first make clear what knowledge and information they should master, that is, come to the node of cognitive breadth. In Case <1>, before upgrading organizational cognition, governments first mastered the necessary knowledge and skills, such as risk source information, virus information, and transmission path, etc. The next step is to explore the essential characteristics and development rules of epidemic risk based on extensive cognition, that is, to come to the node of cognition depth. After the epidemic risk is monitored, the cognitive scope is further expanded through in-depth understanding, and then it enters a virtuous cycle of continuous improvement in the breadth and depth of cognition.

- Cognitive evolution node: The evolution of organizational cognition is reflected in the global changes within the organization affected by various factors, including institutional innovation and technological innovation. In epidemic risk perception, there is an interaction between various factors such as the organizational system, culture, and background. Organizations constantly assimilate external information into their own cognitive structure and constantly change their cognitive structure to adapt to the external environment. Among them, technological tool innovation is not only the result of cognitive evolution but also the support of institutional improvement, such as the makeshift hospital and health code technology in Case <1> and AI technology in Case <2>.

- Cognitive retroaction node: the cognitive retroaction node comes from the intersection of the organizational cognitive spiral curve and the knowledge externalization axis. As part of the dynamic cognitive system, feedback can not only reduce the cognitive differences within and outside the organization through practical interaction but also provide experiences or lessons for improving cognition. At the same time, feedback can also make the organization more active in understanding the required content, what good performance is, and the effort required to achieve the corresponding standard.

5. Key Points Selection of Epidemic Risk Prevention Policy Based on Organizational Cognition

5.1. Interaction between Organizational Cognition and Policy Choice

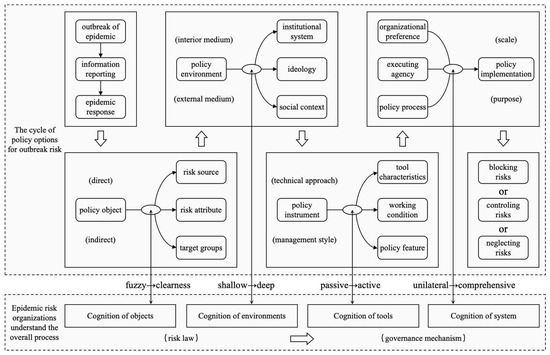

Taking an overview of the change process of epidemic prevention and control policies in the cases, policy selection requires the study and judgment of policy objects, the policy environment, and policy tools in turn, and finally, the policy selection result is determined through the policy process before implementation. At the same time, through the abstract process of organizational cognition, it can be seen that the process of organizational cognition of epidemic risk is divided into four successive and spiral cycle modules: knowledge breadth setting, organizational internalization of knowledge, in-depth exploration of knowledge, and organizational externalization of knowledge. By corresponding the above two to each other according to different modules and links, the interactive logic of organizational cognition and policy choice in the context of epidemic risk can be sorted out (see Figure 5).

Figure 5.

Interactive model of organizational cognition and policy choice.

In different stages of the epidemic, the focus of policy selection is different. First, in the emergency period of the epidemic, the focus of policy selection is the policy object. The organization carries out risk cognition around risk sources, risk attributes, and target groups, and selects policy tools to implement risk prevention and control strategies based on this. Secondly, during the normal control period of the epidemic, policy choices focus on environmental changes and the innovation of technical tools. Finally, in the recovery period at the end of the epidemic, the focus of policy choices is the systematic reconstruction of organizational cognition. On the whole, the policy choice of epidemic risk prevention must go through the organizational cognition process of objectives, the environment, tools, and systems.

The policy object module is the starting point for organizational cognition (Figure 6a). In the SE quadrant of the spiral coordinate system of organizational cognition, organizational cognition begins to generate. First, the categories of knowledge and information that need to be defined, including risk source information, epidemic information, and policy target groups, are determined. Then, it enters the SI quadrant of the cognitive spiral. Through the internalization of the fuzzy epidemic information, a consensus is reached on the initial understanding of the policy object within and between organizations. As we enter the DI quadrant of the cognitive spiral, through the collection of existing information and organizational experience, the risk sources, risk attributes, and target groups of the epidemic are clarified to a certain extent. After that, organizational cognition enters the last link of the single cycle, the DE quadrant, which realizes the externalization of knowledge and the test of existing cognition through epidemiological investigation, early implementation of risk prevention and control strategies, and medical research. In the whole life cycle of the epidemic, this spiral of cognition is constantly repeated. Through a virtuous cycle, the transition of organizational cognition from vagueness to clarity and the scientific effectiveness of policy choices are realized.

Figure 6.

Organizational cognition spiral in epidemic risk prevention policy selection.

The policy environment module is an extension of organizational cognition (Figure 6b). Given the established policy background, the cognitive spiral starts in quadrant ES, that is, the response of the existing institutional background and ideology in the epidemic risk situation. Therefore, the organization can find the inadaptability and inadequacy of the existing institutional system at the breadth level. Then, it enters into the CI quadrant to absorb this maladaptive cognition. Through the internalization of knowledge and the realization of a shared mind, a new depth of organizational cognition is formed to introduce the cognitive spiral into the DI quadrant. Finally, organizational cognition after this development will form a new policy choice model and feed back to the next stage of epidemic risk prevention and control, that is, to realize the externalization of knowledge.

The policy tool module is the evolution of organizational cognition (Figure 6c). The choice of policy tools should first be based on the study and judgment of the current epidemic risk situation, that is to say, the conditions for the choice of policy tools should be clarified. Therefore, the organizational cognitive spiral first starts from the experience and lessons gained from the externalization of the existing knowledge, namely, the ES quadrant. On this basis, organizations begin to select available policy tools, so it is necessary to clarify their characteristics and attributes, including compulsion, tightness, diversity, and combination, etc. This process is mainly reflected in the organization’s internal sorting of existing cognition, so it also introduces organizational cognition into the CI quadrant. After research on and judgment of the decision-making level of the organization, the organization further conducts in-depth research and judgment on the applicability and core laws of policy tools to achieve the improvement of policy tools and the deepening of organizational cognition, and then the appropriate combination of policy tools is selected based on the object and background.

The policy implementation module is the systematization of organizational cognition (Figure 6d). The organizational cognition spiral is a theoretical tool to measure the interaction mode between organizational cognition and policy choice. The research carried out in an existing paradigm does not mean that the practice activities should be carried out in accordance with the fixed process in policy choice, but when crisis management and crisis learning are needed, attention should be paid to the key points of cognition in other modules while focusing on different nodes in each cognitive development stage, so as to make the policy choices in each epidemic period scientific and rational and to release the key points in the policy choices of epidemic risk prevention and control through the paradigm of the organizational cognitive spiral.

5.2. Key Points of Policy Selection for Epidemic Risk Prevention

The policy selection process of epidemic risk prevention and control does not rely on an absolutely fixed template but has different focuses in different stages of epidemic development. The key points of policy selection of epidemic prevention and control can be separated from the organizational cognition node according to the results of case analysis, and thus a multi-source data list system supporting policy selection can be obtained.

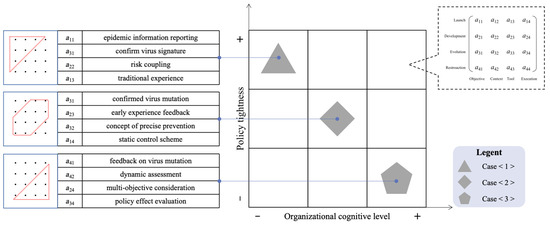

Firstly, a policy node coordinate system was constructed according to the interactive system of organizational cognition and policy choice of epidemic risk (see Figure 7). The horizontal axis is the level of organizational cognition, and the vertical axis is the degree of policy tightness. According to different degrees and combinations, it can be set up as a nine-house pattern, and each house is an observation matrix formed by the intersection of organizational cognition and policy choice. The rows of the matrix are represented as policy choice modules, and the columns of the matrix are, respectively, policy objects, policy environments, policy tools, and policy implementation, and the columns of the matrix are represented as organizational cognitive nodes, namely cognitive initiation, cognitive development, cognitive evolution, and cognitive feedback.

Figure 7.

Evaluation coordinate system of organizational cognition and policy choice based on a cross-matrix group.

Secondly, according to the landmark events that occurred before the decision-making body made policy choices in the three cases, the key event matrix of policy choices in the three cases can be constructed (see Figure 7). Among them, the first table represents the policy choice points in Case <1>, the second one represents the outcome choice points in Case <2>, and the third one represents the policy choice points in Case <3>. By comparing the event matrix of policy choice points, it can be seen that the priorities of policy choice are different at different stages of the epidemic life cycle. According to the development of time, the main points of emphasis in the policy choice matrix are represented by the gradual transition from the upper left corner of the matrix to the lower right corner of the matrix.

Finally, the key features of policy selection in the matrix are summarized. From the perspective of the process, with the development of the epidemic, the prevention and control organizations will have more and more information about the epidemic, and the focus of policy selection will transition from the early stage of the organizational cognition and policy selection process to the later stage, and the characteristic events can be summarized and integrated in a descriptive matrix (see Table 4).

Table 4.

Key point matrix of policy choice based on an interactive system.

6. Results

Firstly, in the early stage of the epidemic, the influence nodes of policy selection are mainly distributed in the intersection of policy objects, policy environment, and the initiation, development, and evolution of cognition. In summary, the intersection of policy objects and cognitive evolution, a31, and the intersection of policy environment and cognitive development, a22, played the most critical role in policy selection in the early stages of the epidemic. In the case of the Wuhan epidemic, it was the expert group that changed the existing cognition of public organizations on the human-to-human transmission of the epidemic, anticipated the spatio-temporal coupling of the epidemic and the Spring Festival travel rush in the next few days, and chose and implemented an efficient Lockdown strategy, which contained the spread of the domestic epidemic risk in a relatively short period of time.

Secondly, in the middle stage of the epidemic, the influence nodes of policy selection are mainly distributed in the intersection of policy environment, policy tools, and the development and evolution of cognition. From case analysis and epidemic risk prevention and control practice, it can be seen that the role of tool innovation is mainly concentrated in the middle stage of epidemic development. The accumulation of cognition in the early stage proved sufficient for the development work, and the urgent need for normal prevention and control provided the necessity. At the end of the epidemic, the focus is no longer on tool innovation but on changing policy preferences based on continuous assessment of policy targets and the policy environment. Therefore, in summary, the intersection of policy objects and cognitive evolution (a31) still plays a key role in policy selection, while the intersection of policy tools and cognitive evolution (a33) provides important technical support for global static control strategies.

Thirdly, at the end of the epidemic, the influence nodes of policy selection are mainly distributed in the intersection of policy environment, policy implementation, cognitive evolution, and cognitive feedback. In the winter epidemic of 2022, public health organizations found, through node a41, that the risk prevention measures for early virus transmission could not adapt to the latest epidemic trend, and adjusted policies by issuing epidemic prevention and control measures to investigate the public opinion response and impact trend of policy choices in advance (a34). Finally, the Class B and Treat as B strategy was officially implemented ten days after the policy was released through the consideration of multiple objectives and systematic research and judgment.

7. Discussion

This study conducted a comprehensive qualitative analysis of organizational cognitive processes and policy choices under epidemic risk, revealing the key points and influencing factors of policy choices at different stages. These findings provide important implications in the face of the potential global pandemic risk of highly virulent infectious diseases such as Disease X.

First of all, when risks are incubated, the government’s accurate judgment of risks will directly affect the formulation of prevention and control strategies. Because the risk of Disease X is highly uncertain and devastating, governments need to quickly and accurately identify risks, assess their possible impacts and harm, and develop appropriate prevention and control strategies. Therefore, strengthening the construction of risk monitoring and early warning systems and improving the cognitive ability of epidemic risk organizations are key to effectively dealing with the risk of Disease X.

Secondly, when the risk has been transformed into an outbreak event, environmental coupling and innovation in policy tools become key to policy choices. In the process of coping with the risk of Disease X, government organizations also need to constantly adjust and improve prevention and control strategies to adapt to changes in risk situations. The innovation and application of policy tools will play an important role, such as the use of advanced technologies, such as big data and artificial intelligence for risk monitoring and forecasting, to provide a more scientific and accurate basis for policy making. At the same time, the changing policy environment also requires greater flexibility and adaptability on the part of the government, which should understand and implement effective strategies at every stage to mitigate negative social communication impacts, ultimately leading to smoother and more effective responses to similar incidents.

Thirdly, as epidemic risks recede, the intersection of cognitive evolution and cognitive feedback becomes central to policy choices. Governments need to evaluate and reflect on the effects of prevention and control strategies and policies in the early stages. By collecting and analyzing feedback information from various aspects, the government objectively evaluates the prevention and control effect and summarizes the experience and lessons to provide reference and guidance for future risk prevention and control work. At the same time, the establishment of a sound feedback mechanism and adjustment mechanism is also an important guarantee to ensure the continuity and stability of policies.

Finally, although this study mainly discussed the choice of the tightness of prevention and control policy from the perspective of organizational cognition, the influence of environmental factors and virus characteristics on policy choice was discussed. On the one hand, the impact of population mobility on policy choices is inevitable. During the epidemic, the government may take more stringent measures to limit the movement of people across the region and reduce the risk of the virus spreading. When formulating policies, organizations need to fully consider population movement data, predict its impact on the spread of the epidemic, and adjust policy flexibility accordingly. On the other hand, natural environmental factors such as temperature will also have an impact on the development of the epidemic and policy choices. The activity, survival, and transmissibility of the virus may vary under certain temperature conditions. Therefore, when formulating epidemic prevention policies, the government needs to timely adjust prevention and control measures to meet the challenges of epidemics in different seasons. In addition, there are significant differences between viral and bacterial outbreaks in terms of transmission mechanisms, infection symptoms, and treatment methods, so different prevention and control strategies need to be formulated. For viral outbreaks, governments may focus more on measures such as isolation, testing, and vaccination. For bacterial outbreaks, policies may focus more on improving sanitation, antibiotic use, and so on. When formulating epidemic prevention policies, the government needs to take these factors into account, combined with the development of organizational cognition, and constantly adjust and optimize prevention and control strategies to cope with the complex and changeable epidemic challenges.

8. Conclusions

Continuously improving epidemic risk organizational cognition and dynamically adjusting epidemic prevention policy choice nodes are the only ways to continuously improve the epidemic risk management ability of public health organizations. Therefore, this paper first analyzes the policy selection process and organizational cognition stage of epidemic prevention in the Wuhan epidemic, the Shanghai epidemic, and the winter 2022 epidemic, and then obtains key events and phased characteristics. On this basis, the organizational awareness spiral for epidemic risk management is described, and the key nodes are obtained. Finally, based on the construction of the interactive system of organizational cognition and policy choice, the key points of epidemic prevention policy tightness were explored by forming a cross-matrix of organizational cognition and policy choice. Through the TSCCA method, we find that the key points of policy choice have significant stage characteristics, and risk characteristics, environmental coupling, development, and use of governance tools play key leading roles. However, due to research tendency and paper length, qualitative analysis is mainly relied on as the research method, and validation based on quantitative analysis has not been fully integrated. Future research may consider using quantitative methods, such as statistical modeling or big data analysis, to more accurately reveal the key points and influencing factors of epidemic risk policy choices. Meanwhile, this study mainly focused on the epidemic situation in specific regions and time periods, and the generalizability and extensibility of its conclusions may be limited to some extent, which needs to be verified in a wider context and sample in future studies.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, C.F. and Y.Z.; Formal analysis, C.F.; Funding acquisition, Y.Z.; Investigation, C.F., Y.Z. and Y.Q.; Methodology, C.F. and Y.Z.; Project administration, C.F.; Resources, C.F. and Y.Z.; Supervision, Y.Z.; Validation, Y.Q.; Writing—original draft, C.F.; Writing—review & editing, C.F., Y.Z. and Y.Q. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This work was supported by the China National Social Science Fund Project (grant number 20BGL252).

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

Data will be made available on request.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to express their sincere gratitude to the anonymous reviewers for their many valuable comments and suggestions.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest. The funders had no role in the design of the study; in the collection, analyses, or interpretation of data; in the writing of the manuscript; or in the decision to publish the results.

References

- Yang, S.; Zhang, L.; Wang, L. Key factors of sustainable development of organization: Bibliometric analysis of organizational citizenship Behavior. Sustainability 2023, 10, 8261. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- WHO Director-General’s Speech at the World Governments Summit—12 February 2024. Available online: https://www.who.int/director-general/speeches/detail/who-director-general-s-speech-at-the-world-governments-summit—12-february-2024 (accessed on 12 February 2024).

- Van Kerkhove, M.D.; Ryan, M.J.; Ghebreyesus, T.A. Preparing for “Disease X”. Science 2021, 6566, 377. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mei, C.Q. Policy style, consistency and the effectiveness of the policy mix in China’s fight against COVID-19. Policy Soc. 2020, 3, 309–325. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Toader, A.F.; Martin, R. Bringing the cognitive revolution forward: What can team cognition contribute to our understanding of leadership? Leadersh. Q. 2023, 1, 101619. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jenkins, W.I. Policy Analysis: A Political and Organizational Perspective; Martin Robertson: London, UK, 1978. [Google Scholar]

- Awaga, A.L.; Xu, W.; Liu, L.; Zhang, Y. Evolutionary game of green manufacturing mode of enterprises under the influence of government reward and punishment. Adv. Prod. Eng. Manag. 2020, 4, 416–430. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tontrup, S.; Sprigman, C.J. Self-nudging contracts and the positive effects of autonomy-Analyzing the prospect of behavioral self-management. J. Empir. Leg. Stud. 2022, 3, 594–676. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guntermann, E.; Lenz, G. Still not important enough? COVID-19 policy views and vote choice. Perspect. Polit. 2022, 2, 547–561. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, J.G.; Smith, D. Disclosure policy choice, stock returns and information asymmetry: Evidence from capital expenditure announcements. Aust. J. Manag. 2022, 4, 192–213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Truby, J. Decarbonizing bitcoin: Law and policy choices for reducing the energy consumption of blockchain technologies and digital currencies. Energy Res. Soc. Sci. 2018, 44, 399–410. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Awazi, N.P.; Tchamba, M.N.; Avana, T.M.L. Climate change resiliency choices of small-scale farmers in cameroon: Determinants and policy implications. J. Environ. Manag. 2019, 250, 109560. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jaunich, M.K.; Levis, J.W.; DeCarolis, J.F.; Barlaz, M.A.; Ranjithan, S.R. Solid waste management policy implications on waste process choices and system wide cost and greenhouse gas performance. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2019, 4, 1766–1775. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Baumann, C.; White, S. Making better choices: A systematic comparison of adversarial and collaborative approaches to the transport policy process. Transp. Policy 2012, 24, 83–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Powe, N.A.; Connelly, S.; Nel, E. Planning for small town reorientation: Key policy choices within external support. J. Rural Stud. 2022, 90, 65–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, X.; Shi, L.; Lu, X.Y.; Li, X.T.; Ma, L. Government dissemination of epidemic information as a policy instrument during COVID-19 pandemic: Evidence from Chinese cities. Cities 2022, 125, 103658. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Stevenson, M.D.; Oakley, J.E.; Chick, S.E.; Chalkidou, K. The cost-effectiveness of surgical instrument management policies to reduce the risk of vCJD transmission to humans. J. Oper. Res. Soc. 2009, 4, 506–518. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berker, L.E.; Bocher, M. Aviation policy instrument choice in Europe: High flying and crash landing? Understanding policy evolutions in the Netherlands and Germany. J. Public Policy 2022, 3, 593–613. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Slovic, P. Perception of risk. Science 1987, 236, 280–285. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abels, G. Experts, citizens, and eurocrats-towards a policy shift in the governance of bio-politics in the EU. Eur. Integr. Online Pap. 2002, 6, 19. [Google Scholar]

- Maule, A.J. Translating risk management knowledge: The lessons to be learned from research on the perception and communication of risk. Risk Manag. Int. J. 2004, 2, 17–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matysiak, L.; Rugman, A.M.; Bausch, A. Dynamic capabilities of multinational enterprises: The dominant logics behind Sensing; transforming seizing, and matter. Manag. Int. Rev. 2018, 2, 225–250. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mol, E.D.; Khapova, S.N.; Elfring, T. Entrepreneurial team cognition: A review. Int. J. Manag. Rev. 2015, 2, 232–255. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hartmann, A. The role of organizational culture in motivating innovative behaviour in construction firms. Constr. Innov. Inf. Process Manag. 2006, 3, 159–172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muthusamy, S.K. Power of positive words: Communication, cognition, and organizational transformation. J. Organ. Chang. Manag. 2019, 1, 103–122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jensen, A.; Secchi, D.; Jensen, T.W. A distributed framework for the study of organizational cognition in meetings. Front. Psychol. 2022, 13, 769007. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Eveland, W.P.; Cooper, K.E. An integrated model of communication influence on beliefs. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2013, 3, 14088–14095. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Duan, J.Y.; Lin, X.S.; Wang, X.T.; Xu, Y. How organizational cultures shape social cognition for newcomer voices. J. Occup. Organ. Psychol. 2022, 3, 660–686. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Islam, G. Extending organizational cognition: A conceptual exploration of mental extension in organizations. Hum. Relat. 2015, 3, 463–487. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gupta, N.; Fischer, A.R.H.; Frewer, L.J. Socio-psychological determinants of public acceptance of technologies: A review. Public Underst. Sci. 2012, 7, 782–795. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Maran, T.K.; Baldegger, U.; Klosel, K. Turning visions into results: Unraveling the distinctive paths of leading with vision and autonomy to goal achievement. Leadersh. Organ. Dev. J. 2022, 1, 133–154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nayak, A.; Chia, R.; Canales, J.I. Non-cognitive micro-foundations: Understanding dynamic capabilities as idiosyncratically refined sensitivities and predispositions. Acad. Manag. Rev. 2020, 2, 280–303. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Argyris, C.; Schon, D.A. Organizational learning: Q theory of action perspective. Reis 1997, 77, 345–348. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moulder, R.G.; Martynova, E.; Boker, S.M. Extracting nonlinear dynamics from psychological and behavioral time series through HAVOK analysis. Multivar. Behav. Res. 2023, 2, 441–465. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wachnicka, J.; Jarczewska, A.; Pappalardo, G. Methods of cyclist training in Europe. Sustainability 2024, 19, 14345. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, T.; Li, J.; Wang, Z.H. Evaluating the influence of static management on individuals’ oral health. BMC Oral Health 2023, 1, 584. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, G.; Wang, X.L.; Zhang, T.Y.; Zhao, W.P.; Ma, L. The impact of confirmed cases of COVID-19 on residents’ traditional Chinese medicine health literacy: A survey from Gansu Province of China. PLoS ONE 2024, 11, e0285744. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, Y.F.; Xu, S.J.; Luo, Y.X.; Peng, J.L.; Guo, J.M.; Dong, A.L.; Xu, Z.B.; Li, J.T.; Lei, L.J.; He, L.; et al. Predicting the transmission dynamics of novel coronavirus infection in Shanxi province after the implementation of the “Class B infectious disease Class B management” policy. Front. Public Health 2024, 11, 1322430. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Masjedi, M.R.; Roshanfekr, P.; Naghdi, S.; Higgs, P.; Armoon, B.; Ghaffari, S.; Ghiasvand, H. Socio-economic contributors to current cigarette smoking among Iranian household heads: Findings from a national household survey. J. Subst. Use 2020, 3, 217–233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Strasser, K.; del Rio, F. The role of comprehension monitoring, theory of mind, and vocabulary depth in predicting story comprehension and recall of kindergarten children. Read. Res. Q. 2014, 2, 169–187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shu, W.; Pang, S.Q.; Chen, M. Achieving structured knowledge management with a novel online group decision support system. Inf. Dev. 2022, 38, 23–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- West, C.J. A methodological framework for improving knowledge creation teams. Eng. Manag. J. 2008, 2, 3–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bakker, A.B.; Breevaart, K.; Scharp, Y.S.; de Vries, J.D. Daily self-leadership and playful work design: Proactive approaches of work in times of crisis. J. Applied Behav. Sci. 2023, 2, 314–336. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).