2. Theoretical Background

The research issues presented in this article require a discussion of several important topics related to tourism. These include the concept of tourism potential and tourist attractions, which are its basic component. It is also necessary to define types of tourism associated with the use of natural tourist attractions and to define sustainable tourism and present its features.

According to the dictionary description, potential encompasses “qualities or abilities that may develop and allow someone or something to succeed” [

23]. In the scientific literature, tourism potential is treated as the capacity of a location to successfully draw in and accommodate visitors, taking into account certain factors, such as the quality and promotion of tourist resources, ease of access and accommodation, and more. Tourism potential encompasses all the natural, cultural, historical, and socio-economic resources vital for the development of tourism in the particular place or area [

24]. According to Kaczmarek et al. [

25] (p. 53), tourism potential includes “all structural and functional resources that condition the development of tourism in a given area”. Structural resources of potential include tourist attractions, tourism infrastructure, communication availability, and other elements important for tourism development. Functional resources, according to Kaczmarek et al. [

25], include economic, political, cultural, ecological, technological, socio-demographic, and psychological conditions present in the area. Bellinger 1994 [

26] distinguished several basic elements of tourism potential, such as natural conditions, tourism infrastructure, social factors, and marketing activities promoting tourism.

Recognizing the tourism potential is one of the basic types of analysis in tourism research. It allows for identifying the most important elements that condition tourism potential in a given area and drawing conclusions regarding the current state and chances for tourism development in the future. The most important methods for identifying and evaluating tourism potential include observation, research based on interviews with tourists and residents, surveys, literature analysis, document analysis, and other sources [

27].

According to Williams 1998 [

28], tourist attractions, including those created by nature, are a fundamental element of the potential that conditions the development of tourism. Many other scientific works also emphasize the special role of natural attractions in shaping the tourism potential of a given area. The importance of green areas, attractive landscapes, and protected nature areas for the development of tourism in smaller and less developed locations, where agriculture or extractive industry economically dominate, is highlighted. Natural assets in such localities offer an opportunity for more diverse and sustainable development, taking into account tourism [

27,

29,

30,

31,

32,

33,

34].

Already Cohen 1972 [

35] noticed that tourist destinations draw tourists’ attention with tourist attractions. Lew 1987 [

36] (p. 554) defined tourist attractions as all “elements of a nonhome place that draw discretionary travelers away from their homes. They usually include landscapes to observe, activities to participate in, and experiences to remember”. Similarly, Pearce [

37] perceived tourist attractions as characteristic and valuable elements that interest tourists, including elements of nature, monuments, and events, such as festivals or sports events [

38].

Tourist attractions should, therefore, be seen as a core of tourist potential and can be divided based on many criteria (

Table 1). One of the most basic divisions was developed by Swarbrooke 2002 [

39] and is based on its origin (genesis). In this case, we can talk about natural attractions created by nature and related to physical elements of the environment, such as beaches, landscapes, mountains, caves, lakes, rivers, and forests. Another type includes objects created by humans during the development of human civilization, such as prehistoric sites, monuments, buildings associated with famous people, palace–garden complexes, industrial centers, and sacred buildings. Another group includes places designed and built from scratch as attractions, such as amusement parks, casinos, spas, and safari parks. The last type of attractions distinguished by Swarbrooke 2002 [

39] are cultural, sports, religious events, festivals, Olympic Games, and other events. This article concerns a case study of the Kroczyce commune, which is particularly rich in tourist attractions created by nature. Therefore, the analysis presented in the article focuses on the natural attractions of the studied area.

However, the division of tourist attractions can also be made based on other premises than genesis. Another division was proposed by Medlik 2011 [

40] (p. 152), in which the basic criterion is the degree of association of the attraction with a given location. In this case, the first group includes attractions related to a given place, such as climate, landscape, history. The next group of attractions includes events, such as festivals, concerts, sports events, trade fairs, etc. In this case, we are dealing with attractions whose location can change, as is the case with the Olympic Games.

Table 1.

Typology of tourist attractions.

Table 1.

Typology of tourist attractions.

| Typology Criterion | Types of Tourist Attractions |

|---|

| Origin (genesis) | -Created by nature and associated with physical elements of the environment.

-Objects created by humans.

-Places designed and built from scratch as attractions.

-Events. |

| The degree of association of the attraction with a given location | -Strictly associated with a specific place.

-Not associated with a specific location. |

Spatial character

| -Point-based.

-Linear.

-Area-based. |

| Range of impact | -International.

-National.

-Regional.

-Local. |

Regarding the spatial character, tourist attractions can be divided into three basic types. The first type is point-based attractions, which refer to individual natural objects (e.g., a cave, waterfall) or those created by humans (e.g., historical buildings). The next group includes linear attractions, such as the seashore, river valley, or tourist routes. The third group of attractions based on spatial characteristics are area-based attractions. This group includes, for example, parks and protected natural spaces or large areas of landscapes attractive to tourists [

41] (p. 240).

Another typology of attractions is based on the range of their impact, which depends on the structure of the tourists visiting the attractions. In this case, we can talk about attractions that have an international reach (dominated by tourists from abroad), national (dominated by tourists from a given country), regional, and local. In the latter cases, domestic tourists coming from the region (regional tourists) or originating from the surroundings of a given attraction (local tourists) dominate [

38] (p. 27).

Tourism is a complex phenomenon encompassing all activities related to the travel of people outside their usual place of residence for purposes related to, among others, rest, sightseeing, and includes the organization and conduct of their activities and of the facilities and services that are necessary for meeting their needs [

28]. As can be seen, tourism is a multifaceted phenomenon, which makes its classification difficult. For this reason, no uniform scheme for the typology of tourist movement has been developed so far. There are many classifications of tourism based, among others, on the number, age, structure of participants, as well as seasonality, type of chosen accommodation, or means of transport used for the trip [

28].

Tourism classification is also based on the motivation of tourists and the purpose of the trip related to it [

28]. Tourists may have specific needs, such as rest or sightseeing, which they fulfill in a specific tourist destination using its attractions and tourist infrastructure. Of course, a tourist trip may be associated with several needs and motives at once. In this case, in order to clearly determine the type of tourism, the dominant need and motive are considered, as stated by Kurek 2012 [

42] (p. 197). For example, Williams 1998 [

28] (p. 11) distinguished recreational and business types of tourism based on tourist needs and motivations. Meanwhile, Kurek 2012 [

42] identified six basic types of tourism based on the needs and motivations driving tourists traveling to a specific destination (

Figure 1).

Qualified tourism emphasizes active leisure and direct contact with nature. It includes various forms of activities, such as mountain climbing, trekking, kayaking, mountain biking, skiing, and spelunking. This type of tourism requires participants to have specific skills and knowledge (i.e., qualifications), appropriate physical preparation, and specialized equipment. Through qualified tourism, travelers can experience unforgettable adventures, explore places inaccessible to the average tourist, and test their own limits of mental and physical resilience [

42].

A term related to qualified tourism, which is more frequently used in the English literature, is active tourism. It can be defined as a form of tourism in which engaging in a particular kind of recreational or hobbyist activity is a main or essential element of the trip, regardless of its duration [

43,

44]. In this case, participants in active tourism do not always (though they may) need to have as high qualifications or physical preparation as those practicing qualified tourism in the strict sense. Active tourism includes various forms of activity related to trips. On the one hand, it includes less demanding forms, like walking, physical exercise, jogging, hiking on typical tourist trails, and participation in trips organized and led by qualified guides (e.g., mountain trekking tours). On the other hand, active tourism can also include trips requiring greater qualifications and preparation (qualified tourism), which involve a higher degree of risk taken by tourists and are associated with extreme sports. As can be seen, active tourism is a broad concept and includes more specialized types of tourism, such as qualified tourism and even adventure tourism [

45].

Another key theme from the perspective of this article is the issue of sustainable tourism. Increasing environmental pollution, climate change, depletion of resources, and growing consumerism are significant challenges for the world. Modern science increasingly embrace sustainable development as a crucial concept for social and economic processes. Sustainable development revolves around the need to satisfy basic human needs, achieve equity and social justice, cultural diversity, ecological integrity and biodiversity, integration of economic development, and environmental preservation [

2,

46]. The Brundtland Report describes sustainable development as growth that meets today’s needs without compromising future generations. This description aligns with the “Report of the Club of Rome” and “Agenda 21” from the 1992 Rio de Janeiro conference. The UN agencies also base their current policies on sustainable development principles, and these policies are now being applied globally to various sectors, including tourism. The essence of sustainable development is to ensure a high quality of life by wisely using resources, meeting societal needs, expanding opportunities, and preserving the environment [

19]. Nowadays, some authors link or even replace sustainable development with the idea of sustainable degrowth. Sustainable degrowth is a socio-political, economic, and ecological concept that advocates for the intentional reduction in production and consumption to achieve social and environmental goals, emphasizing well-being and ecological sustainability over economic growth and material expansion. It challenges the conventional notion that economic growth is inherently positive and seeks a balanced, equitable, and sustainable way of living [

47,

48].

The concept of sustainable tourism Is derived from sustainable development and aligns with its social, economic, and environmental core pillars [

49,

50,

51]. This three-pronged approach is now widely recognized across various societal and economic sectors. Moreover, the UN’s 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development, adopted in 2015, introduced Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs), addressing issues, like poverty, inequality, injustice, and climate change, with specific references to tourism growth [

19]. According to Butler 1993 [

52] (p. 29), sustainable tourism “is developed and maintained in an area (community, environment) in such a manner and at such a scale that it remains viable over an infinite period and does not degrade or alter the environment (human and physical) in which it exists to such a degree that it prohibits the successful development and well-being of other activities and processes”.

Sustainable tourism often encompasses activities beyond mainstream or mass tourism, such as ecotourism, responsible tourism, agritourism, and active tourism. It emphasizes minimal environmental disruption, cultural respect, local community involvement, and enhanced travel satisfaction [

20,

53]. Moreover, sustainable tourism is friendly to the environment and could be well utilized in small regions rich in natural attractions [

21]. In essence, sustainable tourism aims to protect both natural and cultural assets without compromising their integrity [

19]. Niezgoda and Zmyślony 2002 [

54], in line with the principles of sustainable development, identify three primary objectives of sustainable tourism as:

Environmental: conserving natural resources and minimizing pollution.

Economic: boosting local economic welfare, maintaining tourism infrastructure, and gaining a competitive advantage.

Social: offering good jobs, preserving local culture, engaging locals in tourism decisions, and enhancing their well-being.

Established by the United Nations in 2015, the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) consist of 17 interlinked objectives. These goals, set for achievement by 2030 as part of the 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development, cover crucial areas, such as poverty, hunger, health, education, gender equality, clean water and sanitation, affordable and clean energy, decent work and economic growth, industrial innovation and infrastructure, reduced inequalities, sustainable cities and communities, responsible consumption and production, climate action, aquatic and terrestrial life, peace, justice, strong institutions, and partnerships to achieve these goals [

55].

Sustainable tourism is poised to contribute to most of the goals outlined in the 2030 Agenda [

56,

57]. However, it particularly contributes to the goals of environmental sustainability, economic growth, and inclusiveness. In terms of environmental sustainability, focusing on protecting life and providing climate action, sustainable tourism significantly preserves natural resources, like water, landscapes, and biodiversity. It reduces the environmental impact of tourism, advocating for eco-tourism and responsible resource use. It contributes to climate action by recognizing travel and tourism’s impact on climate change and seeking sustainable travel practices [

58].

In the area of decent work and economic growth, sustainable tourism stimulates economic development, particularly in rural and underdeveloped areas, through responsible job and enterprise creation. It encourages local entrepreneurship and craftsmanship and the use of local products, increasing inclusivity and spreading the economic benefits of tourism [

4]. Sustainable tourism also encompasses responsible consumption and production, urging sustainable practices in tourism-related businesses and among tourists to minimize waste and promote efficient resource use [

59,

60].

By aligning with the SDGs, the tourism industry can significantly contribute to sustainable development, balancing the needs of present and future generations and ensuring tourism remains a viable and responsible activity for years to come.

Additionally, from the perspective of this article, it is also important to present the concept of nature-based tourism and its relationship with ecotourism, sustainable tourism, and natural attractions. According to Taczanowska et al., 2019 [

61], nature-based tourism encompasses all varieties of tourism activities where natural settings and environments form the main point of interest. This form of tourism focuses on destinations offering rich, unspoiled natural attractions, like forests, mountains, and wildlife habitats. It attracts visitors who engage in activities, such as hiking and wildlife observation, immersing them in the natural landscape [

62]. Valentine 1992 [

63] observed that tourism where nature (landscapes, wildlife, etc.) is the primary attraction dominated in the 1990s in some regions, like Australia, and was a major tourist type in certain areas, such as the United States, Africa, and Latin America. Nature-based tourism is one of the fastest-growing tourism sectors. It not only allows for the appreciation of nature but also contributes to improving quality of life through sports and recreational activities in natural areas [

64,

65,

66].

Trips aimed at natural attractions can exhibit features of mass tourism. Such trips can leave environmental damage and may also lead to the degradation of wildlife and small local communities. In this case, even though the tourist attraction is nature, and the tourism is nature-based, it is not considered a sustainable form of tourism [

63].

On the other hand, nature-based tourism can successfully be a part of sustainable tourism when conducted with responsibility in visitors’ behavior [

67]. This is especially true when the tourist destination’s capacity is not exceeded. Often, nature-based tourism, which adheres to sustainability principles, is treated as ecotourism, characterized as low-impact, non-consumptive, and locally oriented [

53,

68]. In this case, it is part of sustainable tourism, and the destinations often include unspoiled, legally protected natural areas, like reserves, national parks, or landscape parks [

3,

61].

3. Materials and Methods

Runge 2007 [

69] (p. 21) describes research methods as the systematic ways of collecting, processing, analyzing, and interpreting empirical data to provide justified answers to specific research questions. Similarly, Bryman 2016 [

70] (p. 40) views a research method as a technique for data collection, which may include tools, such as questionnaires, structured interviews, or participant observation. The methods are generally categorized into quantitative and qualitative approaches. Our article particularly focuses on structured interviews and direct observation, which fall under the qualitative methods commonly employed in social sciences disciplines, such as ethnography, sociology, and human geography [

70,

71,

72]. These methods were supplemented with SWOT analysis and desk research.

Qualitative methods, like structured interviews and observation, are essential in understanding tourist potential and attitudes towards sustainable tourism. Structured interviews yield standardized data from various respondents, including residents and visitors, offering insights into diverse preferences and approaches towards sustainable practices. Observation complements this by capturing real interactions at tourist sites, providing practical insights that interviews might miss. Together, these methods offer a holistic view of tourism dynamics, crucial for devising effective sustainable tourism strategies.

A structured interview in social sciences is a research method used to gather data and information from participants in a systematic and standardized manner. It is a qualitative research technique that involves asking a predetermined set of questions to all participants in a consistent and uniform way. A structured interview consists of a group of standardized questions recorded in the form of a questionnaire concerning the issue under investigation. The questions are most often closed-ended with predefined responses, although they may be supplemented with specifically formulated open-ended questions allowing respondents to provide their own answers [

73].

The research procedure adopted for the article involved preparing a standardized questionnaire with questions, selecting respondents, and choosing the method of conducting the study. This article used the personal face-to-face interviewing method. Researchers asked respondents if they would like to participate in the interview, read questions from the questionnaire and recorded the answers. This is one of the most popular forms of interviewing, alongside phone, mail, and online interviewing [

74]. The selection of respondents was non-representative and can be described as an intercept interview. An intercept interview is used to collect data from individuals in real-time while they are at a specific location or engaged in a particular activity [

75].

The questionnaire focused on assessing the tourist potential, with a particular emphasis on natural attractions. It aimed to determine which elements contribute to the municipality’s attractiveness. This included visits to and evaluations of major natural attractions. Additionally, the questionnaire sought to identify both positive and negative factors that impact the development of tourism. It also aimed to recognize the most important types of tourism for the municipality, especially those related to nature, and gathering insights on the vision for its future tourism development. The first group of three questions pertained to the assessment of the tourism potential of the Kroczyce municipality and aimed to identify the elements that have the greatest impact on it. Then, respondents were asked to identify and assess the most important natural tourist attractions in the area under study. A subsequent question referred to opportunities and barriers for tourism development in the municipality and was supplemented by a question regarding tourism-related elements that require rapid improvement. Two questions were also asked about what type of tourism currently dominates and should dominate in the future in the studied area. Then, respondents were asked a question about their vision for the future of tourism in the Kroczyce municipality.

The interview was conducted in paper form, among tourists and residents of the Kroczyce commune. The study was carried out in the months of July–October 2021 and January–February 2022. The main study was preceded by a pilot study, which took place on June 19 in the Kroczyce commune. Its purpose was to check the correctness of the interview questionnaire construction. The main study was conducted in the Góra Zborów Nature Reserve, near the Dzibice water reservoir, near the Okiennik Wielki rock group, in the center of Kroczyce, and around the main bike paths in the studied commune. Overall, 156 questionnaires completed with tourists and residents in the studied area were used for the analysis.

Another method used was observation. It is a key method in various research domains, including tourism or geography. Observation involves systematically watching, recording, and analyzing attractions and facilities, tourists’ behaviors, interactions, and experiences in real-time. Observation may be direct (researcher personally observes facts and behaviors during the fieldwork), or indirect (which involves the analysis of recordings produced by other researchers during their fieldwork) [

76]. In the case of this article, a direct field observation was undertaken to identify and describe the main natural tourist attraction of the Kroczyce commune. The authors visited the most important tourist attractions in the studied area. The main features of the attractions were described in an inventory card, photographs were taken, and notes were made regarding the condition of the objects and the presence of tourists.

The SWOT analysis method was also used for the article. Its name is an acronym for strengths, weaknesses, opportunities, and threats. A SWOT analysis is effective for assessing tourist potential as it examines internal strengths and weaknesses, along with external opportunities and threats. Strengths highlight positive aspects to attract tourists, while weaknesses identify areas for improvement. Opportunities and threats focus on external factors that can impact tourism growth, like travel trends or competitive challenges. This approach offers a balanced overview, aiding in strategic planning for sustainable tourism development [

22,

77].

Further research conducted for the article was desk research. It included creating databases with interview responses and analyzing internet sources. An analysis of the literature, materials, and data obtained from institutions in the studied commune (promotional publications about the commune, statistical data) was also performed.

5. Results

5.1. Natural Tourist Attractions

The Kroczyce municipality is rich in natural tourist attractions. The most important of them are presented in

Table 2, using the classification from Potocka’s 2009 study [

82]. This classification refers to the degree of human intervention in the natural attractions formed in a given area. The collected data indicate that the most numerous group consists of natural attractions shaped without any human intervention. The fewest elements were classified as attractions resulting from significant human intervention. This last group includes, among others, collections and exhibitions of natural objects (e.g., rocks, minerals) that would not have been created without human activity (including collecting artifacts, their conservation, exhibition, etc.).

The spatial distribution of the most important natural attractions is presented in

Figure 3. The symbol of a tree represents the location of a given value, and the labels indicate their names. The area of the Eagle Nests Landscape Park, which runs through the western part of the Kroczyce municipality, is marked in dark gray. The highest concentration of natural values in the studied area is found around the villages of Podlesice and Kroczyce, located in the west of the municipality.

The primary natural asset (formed without human intervention) of the Kroczyce municipality is the karst landscape (

Table 2). This landscape is unique and is associated with the process of karstification occurring below the Earth’s surface. As a result of karstification, grooves, sinks, depressions, karst outliers (from more resistant rocks), and caves, as well as dripstones, stalactites, and stalagmites, are formed. The process of karstification is chemical in nature and involves the dissolution of rocks by water saturated with CO

2. Rocks subject to karstification include primarily limestone, chalk, gypsum, rock salt, and dolomite [

83]. Limestone is commonly found in the Kraków-Częstochowa Upland, including the area of the Kroczyce municipality. The most important limestone rock groups exhibiting features of karst topography in this area include Okiennik Wielki, Skały Kroczyckie, and Skały Podlesickie (

Scheme 1).

The rocks in the municipality of Kroczyce are a tourist attraction, enjoyed by active tourists interested in trekking and rock climbing. The area of limestone rock groups is equipped with basic tourist infrastructure, such as information boards, prepared tourist trails (e.g., the Eagle Nests Trail), and facilities for climbers in the form of anchors for attaching ropes [

84].

The studied territory is also rich in caves, formed as a result of karst processes. These caves are a destination for enthusiasts of active travels associated with cave exploration. The caves here are divided into two types. The first type includes caves that require specialized equipment for exploration (helmets, harnesses, ropes, clamps, and flashlights). The descent into these caves is through a narrow, long shaft, and a person rappels down a rope to the interior of the cave, and then explores its area. Examples of such caves are Żabia Cave and Wielkanocna Cave.

The second type of caves is characterized by entrances in the form of tight horizontal openings. Most of the route in these caves is traversed by crawling and squeezing through narrow passages. An example of this group is Berkowa Cave, located under Góra Kołoczek in the Skały Podlesickie group (

Scheme 2).

Most of the caves in the Kroczyce municipality are difficult to explore and require appropriate qualifications from the tourists who explore them. Bats, which are a protected species in Poland, inhabit these caves. In the Kroczyce area, one can often encounter speleological groups or instructors preparing for extreme activities. The interiors of the caves conceal interesting speleothems and smaller karst structures (

Scheme 3).

In the Kroczyce municipality, there is also a karst cave, which is the only one in the area fully adapted for sightseeing and developed for mass tourism. This is the Głęboka Cave, which is 190 m long and located in the Góra Zborów nature reserve. The cave has stairs, metal railings, lighting, and information boards concerning the geology and history of the cave. It is adapted for visitors who do not possess specialized equipment and skills (

Scheme 4).

The cave is open to visitors only in the presence of a guide and after purchasing an entrance ticket in advance. The walls are rich in speleothems, openings, and calcite chimneys, and one can feel the coolness and humidity emanating from the limestone soaked with water [

85] (

Scheme 4).

Another group of tourist attractions in the Kroczyce commune are natural attractions shaped with partial human intervention (

Table 2). Their core consists of natural elements, but their existence required some human participation. This mainly concerns water reservoirs and areas and objects of protected nature, whose establishment involved, among other things, defining boundaries, limiting human activity (industrial, service, transport), and intensive processes of nature protection and conservation.

The water reservoirs formed on the rivers Białka and Krztynia, that flow through the studied area, are examples of the attractions made with the human intervention. Both rivers are natural attractions formed without any human intervention. However, the water reservoirs were made with human involvement. Their formation required the construction of dams and water locks on rivers. The most significant reservoirs are Dzibice, Biała Błotna, Siamoszyce, and Przyłubsko. These reservoirs facilitate the development of recreational tourism, but also active tourism related to sailing and swimming. The Dzibice water reservoir, created on the Białka river, covers an area of 34 hectares and is in the north-western part of the municipality (

Figure 3). During the holiday season, visitors can rent kayaks, boats, motorboats, and pedal boats here. There are several small, sandy beaches along the shore that are popular with tourists (

Scheme 5). In the peak season, there are small catering establishments and private accommodations for tourists.

Another river located in the Kroczyce commune is Krztynia, which has two water reservoirs: Siamoszyce and Przyłubsko (

Figure 3). The most significant one for tourism is the Siamoszyce reservoir, covering an area of 20 hectares. In the reservoir, you can enjoy swimming and practice water sports. The reservoir is abundant in shoals of carp, pike, perch, and bream. A short distance away, there is a holiday resort, and during the season, water equipment rental services operate at the shore.

The next attraction is the Eagle Nests Landscape Park, which extends into the Silesian and Lesser Poland provinces. The park, as a protected and developed area, is a natural attraction whose creation and existence required human decisions and actions. Landscape parks are one of the forms of nature protection in Poland. They protect areas important for their landscape values and their natural, historical, and cultural values. The existence of a landscape park aims to popularize and preserve these values for future generations under the conditions of sustainable development [

86].

The total area of the Eagle Nests Landscape Park is 608 km

2. It is one of six landscape parks located on the Kraków-Częstochowa Upland. There are 18 communes associated with the park, one of which is the Kroczyce commune. The park’s mission is to protect the limestone and karst landscape of the Jurassic period, as well as the rich flora and unique fauna. The attractions of the park are karst formations, including the most popular karst outliers, valleys, and caves, and medieval castles [

87].

One of the more important natural attractions in the Kroczyce commune is the Góra Zborów Nature Reserve in Podlesice (

Scheme 6). Nature reserves are areas preserved in a natural or slightly altered state, ecosystems, refuges, and natural habitats (including plant, animal, and fungi habitats and inanimate natural formations), distinguished by natural, scientific, cultural, or landscape values. This reserve includes two large hills: Góra Zborów and Kołaczek. The hills are part of the Kroczyce Rocks group. The reserve covers approximately 45 hectares, and within its borders, there are 318 species of plants. Among the plants in the reserve, 11 are strictly protected, and 10 are partially protected, with numerous species at risk of extinction [

88].

Moving on to the fauna of the reserve, the entomofauna (insects inhabiting a given area) is noteworthy. As indicated by the literature, 22 species of butterflies can be found in the reserve, along with bumblebees, which are species under full protection. Reptiles, such as lizards, are also present. There are 49 species of breeding birds (including cuckoos, partridges, long-eared owls, blackbirds, tree pipits, starlings, jays, and others), as well as numerous mammals, including bats [

88]. Bats have their foraging grounds and hibernation sites within the reserve (

Scheme 7).

At the entrance to the reserve, there is also a lapidarium (

Scheme 8) displaying typical rock samples from various geological periods. The main part of the lapidarium consists of rock blocks and erratic boulders, accompanied by descriptive plaques.

Another tourist attraction of the studied municipality is the Natura 2000 area named Ostoja Kroczycka, located near the borders of the Góra Zborów Reserve (

Table 2). Natura 2000 areas are established within the European Union countries with the aim of protecting populations of wild birds and natural habitats. The Ostoja Kroczycka Natura 2000 area was established in 2011 and covers an area of ca. 1391 hectares. Within the municipality, there is also a legally protected natural monument (a form of protection for small natural objects, e.g., trees) in the form of a 500-year-old Linden tree (

Table 2). The monument is in Kroczyce. The tree is 20 m tall, and the trunk circumference is 5.6 m at a height of 1.3 m (

Scheme 9).

The group of natural attractions shaped with significant human intervention is represented by the geological exhibition located in the building of the Center for Natural and Cultural Heritage of the Jura in Podlesice. Humans organize the exhibition, and the displays were collected by geologists and enthusiasts from the region, hence the classification of this asset as being created with significant human intervention (

Scheme 10).

The artifacts presented in the exhibition come from the Kraków-Częstochowa Upland but also from other areas of Poland and the world. The collection includes, among others, sapphires, diamonds, rubies, and other minerals, fossils, and meteorites, as well as shark teeth and dinosaur bones. In addition to the rich collection of minerals and fossils, it is worth paying attention to the educational boards presenting information about the genesis and age of the exhibits [

85].

5.2. Interview Results

In the field, a total of 156 structured interviews were conducted, which were used for the analysis in this article. As many as 72.4% of interviews were conducted with tourists visiting the Kroczyce municipality, and 27.6% were conducted with residents. In the group of respondents, women were predominant (61.5%), while in terms of age, people aged 31–42 years prevailed (33.3%). The largest groups in terms of education were people with secondary (41.7%) and higher education (39.7%). Among the visitors, most people came from the Silesian voivodeship, where the Kroczyce municipality is located (regional visitors). Regarding the length of stays in the area under study, the visiting group mainly indicated short durations, with 1-day stays (54.3%) and 2- and 3-day stays (24.6% when combined). The main travel purposes of the respondents visiting the municipality were related to physical activity and sports (35.7% of visitors’ responses) and rest (33.4%). In summary, the respondents participating in the study were mainly people aged 31–42 years, most often originating from outside the studied municipality but from the region of the Silesian voivodeship, well-educated, female, and staying in the studied area for 1–3 days (

Figure 4).

In the first question, respondents were tasked with assessing the overall current level of tourism potential of the municipality, choosing from the given responses: very high, high, average, low, and very low. As many as 88.5% of respondents indicated a high or very high level of potential. Then, the respondents were asked to assess the overall potential and its main components, such as attractions, tourist infrastructure, communication availability, and the level of tourist promotion of the municipality. The assessment was to be made on a scale from 1 point (lowest) to 5 points (highest). The average assessment of the municipality’s overall potential was 4.25 points, confirming the high assessment indicated in the introductory question. Regarding the components of the potential, the highest number of points were given to natural tourist attractions (4.76), thus indicating their leading impact on tourism in the municipality. Human-made (anthropogenic) attractions and tourist infrastructure received fewer points. The current transportation availability of the research area was rated poorly, and the level of existing tourist promotion of the Kroczyce municipality received the weakest average score of just 2.71 points. Respondents commented that it is decidedly insufficient. Some respondents pointed out that the funds allocated for this purpose by local authorities are insufficient, and there is too little awareness of the importance of promotional activities for the development of tourism (

Table 3).

Subsequently, respondents were asked which of the components most significantly determines the tourist potential of the Kroczyce municipality. Respondents answered using a Likert scale (the Likert scale is a psychometric scale commonly used in questionnaires and surveys to measure respondents’ attitudes, opinions, or perceptions. It typically presents a statement or question followed by a series of response options that range from “strongly agree”, “agree”, and “neutral” to “disagree” and “strongly disagree” [

89]). As the element with the greatest impact on the potential, respondents pointed to the tourist attractions of the area under study. In discussions, they emphasized the particular importance of tourist attractions highlighting those created by nature. As many as 75.7% of respondents strongly agreed with this statement. According to respondents, actions related to tourist promotion and existing tourist infrastructure facilities in the municipality also have a significant impact on the potential. The dependence of potential on accessibility to the Kroczyce municipality and the activities of local institutions related to tourism development were rated lower. Considering the two questions discussed earlier, it can be stated that, according to respondents, the potential of the municipality is determined by high-class natural tourist attractions, which are vital for the creation of tourism based on a sustainable model. On the other hand, respondents understand the significant role of promotional activities and tourist infrastructure in shaping tourist potential, but they rate the current level of these elements decidedly lower than natural attractions (

Table 4).

One of the key questions in the survey concerned the natural tourist attractions that respondents visited in the Kroczyce municipality. In this question, respondents were also asked to evaluate these attractions. The structure of the responses indicates which natural attractions most capture the attention of visitors (during their visit to the municipality) and residents (during activities undertaken in their free time). This was a multiple-choice question; respondents indicated which attractions they visited and then rated them.

Góra Zborów Nature Reserve, the Natura 2000 Area Ostoja Kroczycka, and the Głęboka Cave were the places that respondents visited most frequently (

Table 5). The highest-rated natural attractions in the municipality were also the Góra Zborów Nature Reserve, the Głęboka Cave (with an average rating of about 4.8), and the Natura 2000 Area Ostoja Kroczycka (4.7) and groups of rock formations (like Kroczyckie Rocks, Podlesickie Rocks). Among all the suggested places, only the Dzibice, Biała Błotna, and Siamioszyce water reservoirs were rated slightly below 4 points. The structure of the ratings thus indicates a prominent level of natural attractions in the Kroczyce municipality. Additionally, to emphasize the importance of the most popular places,

Table 6 presents data on the volume of tourist traffic in the highest-rated natural attractions in the municipality, i.e., in the Góra Zborów Nature Reserve and the Głęboka Cave. This data indicates a substantial number of visitors in both locations.

In the subsequent part of the interview, respondents were asked to indicate the main factors positively influencing tourism in the Kroczyce municipality and the most significant barriers to its development. According to the respondents, the positive factors mainly include the natural attractions of Kroczyce, such as green areas and the picturesque Jurassic landscape (rocks, caves), which enable leisure and active tourism. On the other hand, the barriers identified by the respondents were primarily limited access to the municipality from outside its area and poor internal communication within the municipality (lack of roads, a weak bus network). Other barriers mentioned included insufficient tourist promotion and inadequate food infrastructure for the needs of tourist traffic.

The question about barriers was supplemented with another request to indicate tourism-related elements that require rapid improvement. Most frequently, respondents pointed to the need for development related to communication and transportation (17.8%). Respondents also emphasized the need to increase the number of parking spaces (6.9%) and trash bins (15.4%), and the insufficient number of dining establishments (14.7%). Attention was also drawn to the too few information boards, poor signage, the condition of tourist trails, and the insufficient number of public toilets and bicycle shelters.

Subsequent questions in the survey questionnaire related to the type of tourism that, according to respondents, currently dominates and should dominate in the future in the studied area. In the case of the question about the currently dominant type of tourism, active tourism (33.7%) and qualified tourism (31.4%) were most frequently indicated. Then, the respondent was to indicate what type of tourism should prevail in the municipality in the future. Again, the responses were dominated by active tourism (47.4%) and qualified tourism (18.1%), with leisure tourism (16.5%) in third place.

Qualified and active tourism, most often mentioned in respondents’ answers, are specific types of tourism where emphasis is placed on active leisure and direct contact with nature. This includes activities, such as mountain climbing, trekking, kayaking, sailing, mountain biking, skiing, or caving. Qualified tourism requires participants to have higher qualifications, such as certain skills, appropriate physical preparation, and often specialized equipment. Thanks to qualified and active tourism, travelers can experience unforgettable adventures, explore places inaccessible to the average tourist, and test their own limits. It is an excellent way to combine a passion for sports with a love of nature and utilizing attractions created by it.

Subsequently, respondents were asked about their vision for the future of the Kroczyce municipality. Four answers were proposed for selection. Respondents were asked to choose an answer, and the question was multiple-choice. The results obtained indicate that in the future, Kroczyce should develop as an area of qualified and active tourism (35.8% of responses), or as an area distinguished by protected nature areas (31.9% of responses) (

Table 7). This confirms the previously obtained opinions of respondents indicating the high importance of natural attractions, protected nature areas, and qualified and active tourism in the surveyed area.

The lands with karst topography, to which the Kroczyce municipality belongs, have numerous attractions, such as karst rocks and caves, making them an excellent place for active and qualified tourism. Firstly, the karst landscape is extremely picturesque and diverse, attracting nature lovers and outdoor enthusiasts. Karst rocks form unique formations that challenge climbers. Caves, on the other hand, offer unforgettable experiences for speleology enthusiasts, providing the opportunity to explore a fascinating underground world. Additionally, Jurassic areas located near to larger cities are an attractive destination for weekend trips and excursions.

Areas of this type are often protected as reserves or landscape or national parks, ensuring the protection of unique ecosystems and the preservation of wild nature. For nature enthusiasts, it is an ideal place for observing fauna and flora and learning about environmental protection. As a result, the Jurassic lands with karst topography are an excellent place for practicing various forms of active tourism, encouraging climbing, cave exploration, and other forms of activity. At the same time, they remain an oasis of wild nature, attracting ecology enthusiasts. Areas, such as the Kroczyce municipality, are, therefore, a place where physical activity and contact with nature come together in a harmonious tourist experience.

5.3. SWOT Analysis

Another method used in the analysis of the tourist potential resulting from the tourist attractions of the Kroczyce commune was SWOT analysis (

Table 7). Among the internal factors favoring the development of sustainable tourism based on the natural elements of the potential of the Kroczyce commune (strengths), one should primarily point to the wealth of natural attractions related to the karst landscape and numerous protected nature areas. They can form the basis for the development of sustainable forms of active tourism (trekking), specialized tourism (climbing, spelunking), but also recreational tourism. The willingness of the local community to engage in the development of sustainable nature tourism, emphasized by some of the respondents participating in the interview, can also be helpful. On the other hand, there are several weaknesses that hinder the development of sustainable tourism. The Kroczyce commune does not have an established brand and has weak tourist promotion. This results from the small funds allocated for this purpose by local authorities and insufficient awareness of the importance of promotional activities. The weaknesses of the commune also include insufficient development of tourist infrastructure (e.g., gastronomic, related to tourist trails) and damage to vegetation caused by tourists visiting the commune during the peak season (summer months).

On the other hand, the most important external positive factors (opportunities) supporting the development of sustainable nature tourism include the popularity and positive social attitude towards the concept of sustainable tourism. It is also important to exploit the opportunity to attract investors and funding (e.g., from the European Union) for projects related to this type of tourism and the possibility of developing a comprehensive plan for the promotion and development of sustainable tourism at the commune level. The growing social popularity of sustainable tourism, as well as active and nature-based tourism, is also significant. On the other hand, threats include the possible deepening of overtourism problems, still insufficient recognition of the need for environmental protection, or competition from neighboring communes (

Table 8).

For the Kroczyce commune, addressing the weaknesses and threats identified in the SWOT analysis can be approached through a series of targeted solutions. To address the lack of an established brand and low level of promotion, developing a branding strategy that highlights Kroczyce’s unique natural attractions is important. Creating a distinctive logo and slogan that capture the essence of the area is also crucial. Utilizing social media and digital marketing to promote the area’s attractions, with a focus on its natural beauty and unique geological features, is of the utmost importance. Engaging with travel bloggers and influencers to showcase Kroczyce’s tourism potential could also be beneficial.

Addressing limited financial resources for tourism and promotion requires forming partnerships with private entities for funding and sponsorship, as well as applying for government grants and EU funds dedicated to regional development and tourism. Collaborating with non-governmental organizations (NGOs), renowned for their knowledge and grassroots connections, is vital in implementing sustainable government policies and funds to enhance tourism practices. This partnership not only fosters effective sustainable tourism strategies but also ensures local community engagement and integrates local needs into tourism policies.

Insufficient transportation accessibility and tourist infrastructure can be improved by establishing development-responsible projects to enhance road and public transport links. Offering shuttle services from major nearby cities or attractions is also advisable. Planning for sustainable tourism infrastructure that blends with the natural environment is important, as is encouraging local entrepreneurs to develop tourist accommodations and amenities.

The risk of overtourism and damage to plant cover by tourists requires educational signage about environmental preservation throughout tourist areas and organizing guided tours to limit off-path exploration. Implementing strict regulations for waste management and conservation practices in tourist areas is essential. Involving local communities in conservation efforts and monitoring is also crucial. Developing a tourism management plan that includes visitor limits for sensitive areas and promoting off-peak tourism to distribute visitor numbers throughout the year are important strategies.

Addressing insufficient public awareness about protected areas requires launching educational campaigns and workshops on the importance of preserving natural and cultural heritage. Collaborating with schools and educational institutions for awareness programs is also effective.

To counter competition from neighboring municipalities, it is necessary to identify and promote the unique selling points of Kroczyce that differentiate it from neighboring areas. Establishing partnerships with nearby municipalities for joint tourism ventures that benefit all is also a strategic approach.

To preserve and promote local culture and traditions and to prevent the loss of spatial and cultural distinctiveness, developing tourism in a way that enhances local identity rather than overshadowing it is key. By strategically addressing these areas, the Kroczyce commune can leverage its natural and cultural assets to develop a sustainable and distinctive tourism sector.

6. Discussion

The Kroczyce commune is in southern Poland, in the area of the Kraków-Częstochowa Upland (also known as the Kraków-Częstochowa Jura), and although its character is primarily agricultural, tourism has enormous potential here. During the field research conducted, including observations and interviews with residents and tourists, the importance of natural tourist attractions for shaping the tourist potential of this area was confirmed. The main tourist attractions include the karst landscape, rock formations, caves, and nature protected areas which form the basis for the development of active and specialized tourism. In the structured interview, natural attractions received the highest score and were recognized by respondents as determining the tourism potential of the studied area. Tourist attractions are any valuable elements attracting visitors to a given tourist destination [

35,

36,

37]. They are the main feature shaping the tourist potential of a place and determine its current and further development in tourism [

25,

26]. In the case of the Kroczyce commune, the most important features turned out to be natural attractions, which are one of the basic types of attractions distinguished in the literature according to the origin [

38,

39,

62]. In the Kroczyce commune, the most important attractions include magnificent karst landscapes, rock formations, caves, and interesting protected nature areas.

The answers of the respondents participating in the interviews gave a clear picture of how they perceive the tourist potential of the Kroczyce commune. The potential was rated highly (4.25 points). Respondents primarily drew attention to the unique conditions and natural attractions of this commune, which significantly shape its potential. According to respondents’ views, natural attractions received the highest score of 4.76 points. Among these, Góra Zborów, the Natura 2000 Area Ostoja Kroczycka, and Głęboka Cave were rated highest by interview participants. Furthermore, respondents indicated that factors positively influencing the tourist potential of Kroczyce primarily include its natural attractions. It is important to note that natural assets in small communes, as evidenced by previous studies [

29,

32,

33,

34,

66], provide a foundation for sustainable development centered on natural attractions. These attractions also facilitate the development of nature-based and ecotourism, as highlighted in Cvetković’s 2023 [

3] study.

Tourist infrastructure and accessibility are other essential elements that make up the concept of tourist potential [

25,

26]. Moreover, the proper use of potential in areas wishing to develop tourism requires an efficiently organized system of tourist promotion [

22]. Many respondents appreciated the importance of these elements, while emphasizing that the tourist infrastructure and the level of promotion of the commune are not currently developed enough to fully exploit its natural potential.

The phenomenon of tourism can be divided in several ways. One of them is to distinguish types of tourism based on tourist needs and motivations [

28]. Kurek 2012 [

42] proposed six basic types of tourism based on this criterion (

Figure 1). Respondents participating in the interview conducted in the studied area emphasized that the ideal direction for the Kroczyce commune is to develop types of active and qualified tourism (35.8% of responses) or an area distinguished by protected nature areas (31.9% of responses). Due to the wealth of natural attractions, such as karst landscapes, rock groups, caves, and protected areas, the commune should focus on tourism based on natural attractions, enabling active leisure and relaxation in nature. This approach has several advantages. First, it allows for sustainable development, which is crucial for preserving the natural heritage of the region. Such tourism is also a response to contemporary trends, where more people are looking for active recreation in unspoiled nature.

Sustainable tourism involves the holistic management of various kinds of regions to meet economic, social, and environmental needs while integrating culture, ecological processes, biodiversity, preserving natural resources, and fostering societal development in accordance with the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) [

4,

49,

52,

59]. It frequently includes experiences that go beyond conventional or large-scale tourism, encompassing ecotourism, responsible tourism, agritourism, and active tourism. Its focus lies on minimizing environmental impact, respecting local cultures, engaging with communities, and enhancing travelers’ enjoyment [

20,

53]. Sustainable tourism is particularly important for small rural areas, like Kroczyce, which have valuable natural attractions [

21]. It is a development model that not only allows preserving natural values for future generations but also counteracts excessive exploitation (overtourism). In addition to the environmental aspect, it also has a social and economic aspect, positively affecting the local community. The protection and preservation of natural resources for future generations, boosting the local economy, social equity, well-being, and preserving local culture are among the principles of sustainable tourism [

54].

Participants of the questionnaire interview appreciate the significant importance of natural tourist attractions and see the future of Kroczyce commune as an area for qualified and active tourism and a territory with protected areas. The development of tourism based on natural attractions and active nature tourism associated with protected areas presents an opportunity for the development of sustainable tourism. This, in turn, leads to a range of social implications.

Implementing sustainable tourism in a commune abundant in natural attractions brings significant social benefits. Educational activities focusing on nature protection and sustainable development elevate community awareness and conservation culture [

90]. Campaigns promoting sustainable tourism enhance community pride and promote adherence to responsible tourism practices. Encouraging exploration and respect for local culture and traditions enriches visitor experiences. Volunteer programs for nature protection foster community involvement [

91,

92]. Involving government officials, policy makers, non-governmental organizations (NGOs), residents and tourists in monitoring tourism’s environmental impact promotes sustainable practices. Broad social consultations ensure inclusive tourism policies, creating a collaborative environment for achieving sustainable tourism goals [

93,

94].

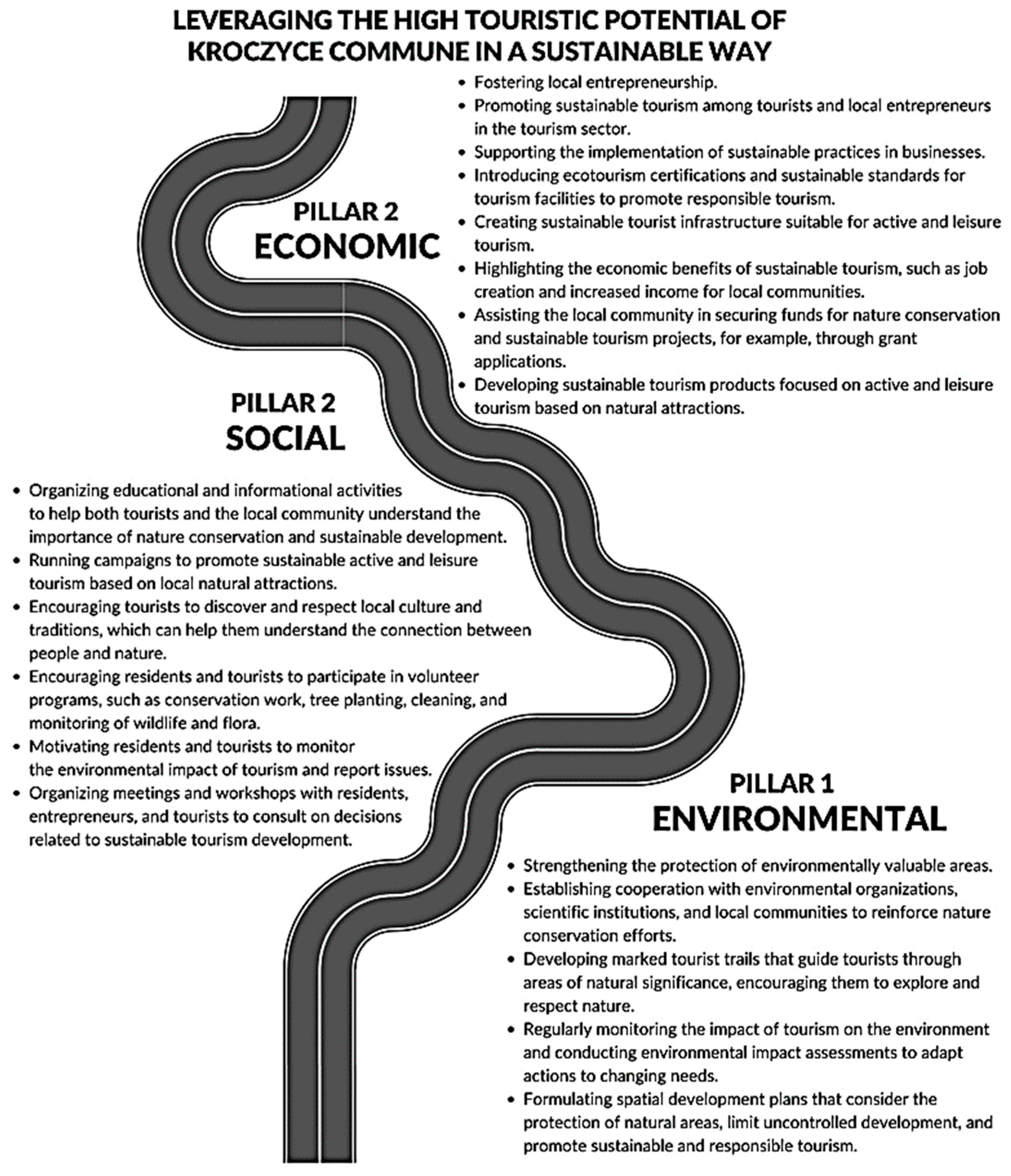

To fully utilize the tourist potential of the Kroczyce commune in a sustainable way, a roadmap was developed, indicating the direction of actions in natural, social, and economic pillars of sustainable tourism (

Figure 5).

In the environmental pillar, roadmap proposals include strengthening the protection of natural areas and developing cooperation with communities engaged in eco-friendly activities. It is also proposed to develop marked tourist trails, monitor the impact of tourism on the environment, and develop spatial planning plans that consider the protection of natural areas, control unregulated development, and promote sustainable and responsible tourism.

In the social pillar, the most important proposed actions include conducting educational and informational activities in the field of nature protection and sustainable development, as well as campaigns promoting sustainable active and leisure tourism based on local natural attractions. Further suggestions include encouraging tourists to explore and respect local culture and traditions, developing volunteer programs related to nature protection, encouraging residents and tourists to monitor the impact of tourism on the environment, and organizing broad social consultations in the field of tourism and sustainable development.

In the economic pillar, the roadmap proposes supporting the development of local entrepreneurship, promoting sustainable tourism among tourists and local entrepreneurs, and supporting the implementation of sustainable practices in enterprises. Additionally, it proposes the creation of sustainable tourist infrastructure and the promotion of the economic benefits resulting from sustainable tourism. Assisting the local community in obtaining funds for projects related to nature protection and sustainable tourism and creating sustainable tourist products in the field of active and leisure tourism based on natural attractions are further possible actions (

Figure 5).

7. Conclusions

In conclusion, the municipality of Kroczyce, nestled in southern Poland, is on the precipice of transforming itself from a primarily agricultural community into a burgeoning hotspot for nature tourism. Kroczyce boasts an array of unique natural attractions that set it apart. The karst landscape, caves, and water reservoirs are significant, and the region is rich in protected nature areas. These natural assets are not only a haven for a diverse range of flora and fauna but also present important attractions for nature enthusiasts. Hiking, cave exploration, leisure, and camping are just a few of the activities that could attract tourists seeking solace in nature’s embrace.

Our research is a case study focused on the role of natural attractions in creating sustainable, nature-based tourism. It confirmed that the natural landscape, rock formations, water reservoirs, protected areas, and caves are vital elements of tourist potential and particularly valuable assets for tourism, which can be utilized sustainably. The findings also highlight an important level of awareness among residents and visitors about the role of natural attractions in tourism development and the need for sustainable tourism practices. Local authorities can leverage this potential in Kroczyce by adopting a thoughtful and sustainable approach to tourism development. By investing in eco-friendly infrastructure, promoting conservation efforts, and involving the local community, Kroczyce can ensure that tourism evolves in harmony with the environment. Such practices will not only enhance the experience for tourists but also ensure the preservation of the natural ecosystem for future generations.

Additionally, the transformation into a nature tourism hub can bring significant socio-economic benefits to the residents of Kroczyce. The influx of tourists can lead to job creation, an increase in local trade, and improved amenities, thus contributing to the overall development of the region.

Kroczyce stands at a crossroads where the right strategies can shape its identity as an important point on the map of nature tourism in Poland. By balancing the preservation of its agricultural roots with a forward-thinking approach to sustainable tourism, the municipality can create a model that benefits residents, tourists, and the environment alike.

This study, investigating the role of natural attractions in the creation of tourist potential and development of sustainable, nature-based tourism in Kroczyce, a small agricultural municipality in Poland, encountered certain limitations. Primarily, the research relied on field observations and interviews with residents and mostly regional tourists. While this approach provided valuable insights, it may have introduced biases based on the perspectives and experiences of the interviewees. Additionally, the study’s geographic and demographic scope potentially affected the generalizability of the findings to other regions or types of municipalities.

Future research directions should aim to validate and expand upon these findings in diverse contexts. Investigations in different geographic locations and varied types of communities would help in verifying the universality of the study’s conclusions. Furthermore, employing a wider range of research methodologies, such as the Delphi method and studies involving decision-makers, could offer a more comprehensive understanding and strengthen the validity of the conclusions.