The Role of Passive Investors in Corporate Governance and Socially Responsible Investing: Evidence from Shareholder Proposals

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Hypothesis Development

2.1. Background on Passive Investors

2.2. Shareholder Proposals

2.3. The Link between Passive Ownership and Shareholder Proposal

2.4. The Potential Moderating Role of Managerial Ability on Passive-Shareholder Proposal Link

2.5. The Possible Moderating Role of the Co-Opted Board

3. Data, Summary Statistics, and Empirical Frameworks

3.1. Passive Ownership

3.2. Shareholder Proposals

3.3. Firm-Level Variables

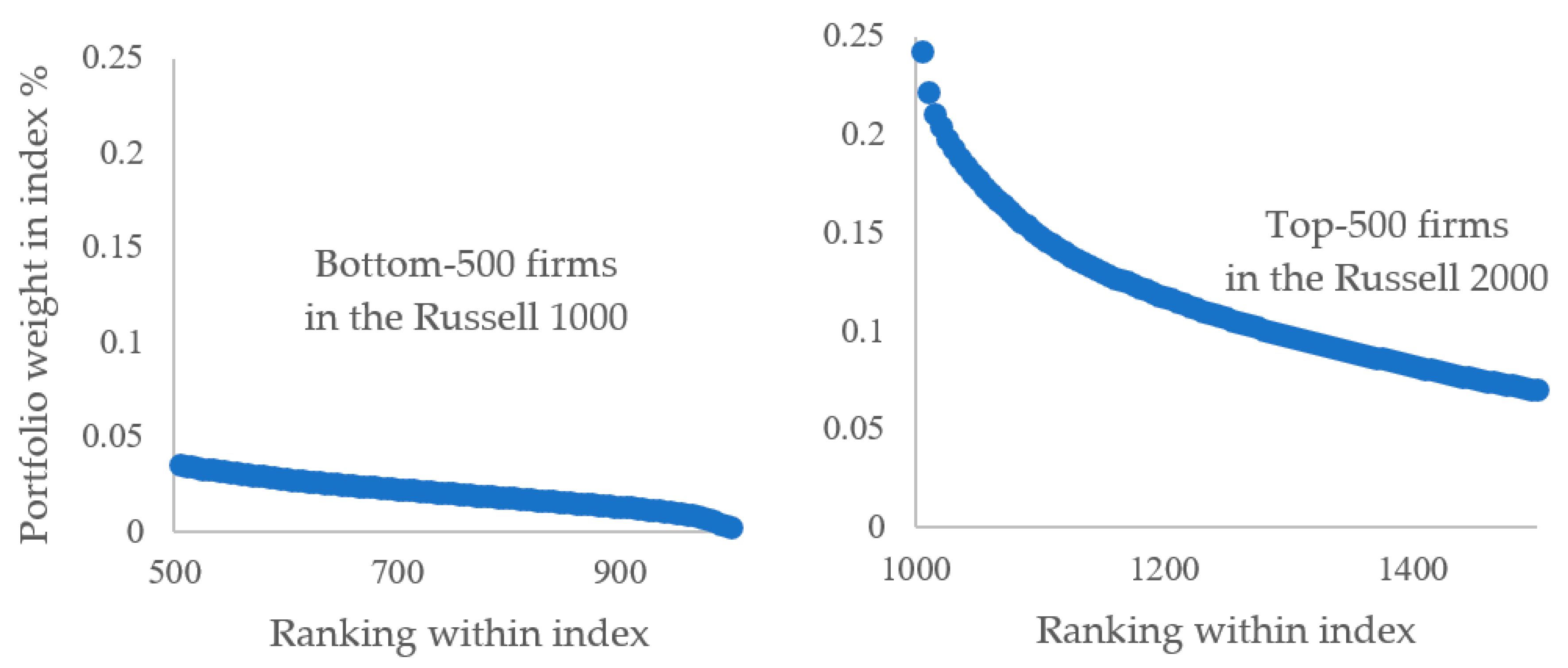

3.4. Russell 1000/2000 Index Reconstitution

3.5. Descriptive Statistics

3.6. Empirical Framework

4. Results

4.1. Baseline Results

4.1.1. The Impact of Passive Ownership on Shareholder Proposals

4.1.2. The Moderating Role of Managerial Ability

4.1.3. Does Board Co-Option Matter

4.2. Passive Ownership and Shareholder Proposal Withdrawals

4.3. The Impact of Passive Investors on Voting Outcomes

4.4. Long-Term Value Implication

4.5. Robustness Check

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A

References

- Fichtner, J.; Heemskerk, E.M.; Garcia-Bernardo, J. Hidden Power of the Big Three? Passive Index Funds, Re-Concentration of Corporate Ownership, and New Financial Risk. Bus. Polit. 2017, 19, 298–326. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Appel, I.R.; Gormley, T.A.; Keim, D.B. Passive Investors, Not Passive Owners. J. Financ. Econ. 2016, 121, 111–141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Appel, I.R.; Gormley, T.A.; Keim, D.B. Standing on the Shoulders of Giants: The Effect of Passive Investors on Activism. Rev. Financ. Stud. 2019, 32, 2720–2774. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Passive Likely Overtakes Active by 2026, Earlier If Bear Market|Insights|Bloomberg Professional Services. Available online: https://www.bloomberg.com/professional/blog/passive-likely-overtakes-active-by-2026-earlier-if-bear-market/ (accessed on 16 December 2023).

- Jahnke, P. Ownership Concentration and Institutional Investors’ Governance through Voice and Exit. Bus. Polit. 2019, 21, 327–350. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Webber, D.; Barzuza, M.; Curtis, Q. Shareholder Value(s): Index Fund ESG Activism and the New Millennial Corporate Governance. South. Calif. Law Rev. 2020, 93, 1243. [Google Scholar]

- Johnson, M.F.; Shackell, M.B. Shareholder Proposals on Executive Compensation. SSRN 1997. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sjostrom, W.K.J.; Kim, Y.S. Majority Voting for the Election of Directors. Conn. Law Rev. 2007, 40, 459. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferri, F. ‘Low-Cost’ Shareholder Activism: A Review of the Evidence. In Research Handbook on the Economics of Corporate Law; Claire Hill & Brett McDonnell, Ed.; Edward Elgar Publishers: Cheltenham, UK, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Azar, J.; Duro, M.; Kadach, I.; Ormazabal, G. The Big Three and Corporate Carbon Emissions around the World. J. Financ. Econ. 2021, 142, 674–696. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boone, A.L.; White, J.T. The Effect of Institutional Ownership on Firm Transparency and Information Production. J. Financ. Econ. 2015, 117, 508–533. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, T.; Dong, H.; Lin, C. Institutional Shareholders and Corporate Social Responsibility. J. Financ. Econ. 2020, 135, 483–504. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Crane, A.D.; Michenaud, S.; Weston, J.P. The Effect of Institutional Ownership on Payout Policy: Evidence from Index Thresholds. Rev. Financ. Stud. 2016, 29, 1377–1408. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schmidt, C.; Fahlenbrach, R. Do Exogenous Changes in Passive Institutional Ownership Affect Corporate Governance and Firm Value? J. Financ. Econ. 2017, 124, 285–306. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khan, M.; Srinivasan, S.; Tan, L. Institutional Ownership and Corporate Tax Avoidance: New Evidence. Account. Rev. 2017, 92, 101–122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ertimur, Y.; Ferri, F.; Muslu, V. Shareholder Activism and CEO Pay. Rev. Financ. Stud. 2011, 24, 535–592. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Del Guercio, D.; Seery, L.; Woidtke, T. Do Boards Pay Attention When Institutional Investor Activists “Just Vote No”? J. Financ. Econ. 2008, 90, 84–103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gillan, S.L.; Starks, L.T. Corporate Governance Proposals and Shareholder Activism: The Role of Institutional Investors. J. Financ. Econ. 2000, 57, 275–305. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gillan, S.L.; Starks, L.T. Corporate Governance, Corporate Ownership, and the Role of Institutional Investors: A Global Perspective. J. Appl. Financ. 2003, 13, 4–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grewal, J.; Serafeim, G.; Yoon, A. Shareholder Activism on Sustainability Issues. SSRN 2016. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ng, J.; Wu, H.; Zhai, W.; Zhao, J. The Effect of Shareholder Activism on Earnings Management: Evidence from Shareholder proposals. J. Corp. Financ. 2021, 69, 102014. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smith, M.P. Shareholder Activism by Institutional Investors: Evidence from CalPERS. J. Financ. 1996, 51, 227–252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Renneboog, L.; Szilagyi, P.G. The Role of Shareholder Proposals in Corporate Governance. J. Corp. Financ. 2011, 17, 167–188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prevost, A.K.; Rao, R.P.; Williams, M.A. Labor Unions as Shareholder Activists: Champions or Detractors? Financ. Rev. 2012, 47, 327–349. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prevost, A.K.; Rao, R.P. Of What Value Are Shareholder Proposals Sponsored by Public Pension Funds. J. Bus. 2000, 73, 177–204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matsusaka, J.G.; Ozbas, O.; Yi, I. Opportunistic Proposals by Union Shareholders. Rev. Financ. Stud. 2019, 32, 3215–3265. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wahal, S. Pension Fund Activism and Firm Performance. J. Financ. Quant. Anal. 1996, 31, 1–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Agrawal, A.; Lim, Y. Where Do Shareholder Gains in Hedge Fund Activism Come From? Evidence From Employee Pension Plans. J. Financ. Quant. Anal. 2022, 57, 2140–2176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brav, A.; Jiang, W.; Kim, H. The Real Effects of Hedge Fund Activism: Productivity, Asset Allocation, and Labor Outcomes. Rev. Financ. Stud. 2015, 28, 2723–2769. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brav, A.; Jiang, W.; Partnoy, F.; Thomas, R. Hedge Fund Activism, Corporate Governance, and Firm Performance. J. Financ. 2008, 63, 1729–1775. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Denes, M.R.; Karpoff, J.M.; McWilliams, V.B. Thirty Years of Shareholder Activism: A Survey of Empirical Research. J. Corp. Financ. 2017, 44, 405–424. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- DesJardine, M.R.; Shi, W.; Sun, Z. Different Horizons: The Effects of Hedge Fund Activism Versus Corporate Shareholder Activism on Strategic Actions. J. Manag. 2022, 48, 1858–1887. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fu, L.; Pan, L.; Wu, F. Does Passive Investment Have a Positive Governance Effect? Evidence from Index Funds Ownership and Corporate Innovation. Int. Rev. Econ. Financ. 2021, 75, 524–545. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Petry, J.; Fichtner, J.; Heemskerk, E. Steering Capital: The Growing Private Authority of Index Providers in the Age of Passive Asset Management. Rev. Int. Polit. Econ. 2021, 28, 152–176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Easley, D.; Michayluk, D.; O’Hara, M.; Putniņš, T.J. The Active World of Passive Investing. Rev. Financ. 2021, 25, 1433–1471. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haddad, V.; Huebner, P.; Loualiche, E. How Competitive Is the Stock Market? Theory, Evidence from Portfolios, and Implications for the Rise of Passive Investing. SSRN 2021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abramova, I.; Core, J.E.; Sutherland, A. Institutional Investor Attention and Firm Disclosure. Account. Rev. 2020, 95, 1–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McCAHERY, J.A.; Sautner, Z.; Starks, L.T. Behind the Scenes: The Corporate Governance Preferences of Institutional Investors. J. Financ. 2016, 71, 2905–2932. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dubois, E. Passive Investors Get Active on Sustainability Risks. Harv. Law Sch. Forum Corp. Gov. 2020. Available online: https://corpgov.law.harvard.edu/2020/03/12/passive-investors-getactive-on-sustainability-risks/ (accessed on 13 November 2023).

- Gormley, T.A.; Gupta, V.K.; Matsa, D.A.; Mortal, S.C.; Yang, L. The Big Three and Board Gender Diversity: The Effectiveness of Shareholder Voice. J. Financ. Econ. 2023, 149, 323–348. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bardos, K.S.; Ertugrul, M.; Gao, L.S. Corporate Social Responsibility, Product Market Perception, and Firm Value. J. Corp. Financ. 2020, 62, 101588. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fallah Shayan, N.; Mohabbati-Kalejahi, N.; Alavi, S.; Zahed, M.A. Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) as a Framework for Corporate Social Responsibility (CSR). Sustainability 2022, 14, 1222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fatima, T.; Elbanna, S. Corporate Social Responsibility (CSR) Implementation: A Review and a Research Agenda Towards an Integrative Framework. J. Bus. Ethics 2023, 183, 105–121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gillan, S.L.; Koch, A.; Starks, L.T. Firms and Social Responsibility: A Review of ESG and CSR Research in Corporate Finance. J. Corp. Financ. 2021, 66, 101889. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, D.Z.X. Environmental, Social and Governance (ESG) Activity and Firm Performance: A Review and Consolidation. Account. Financ. 2021, 61, 335–360. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, T.-T.; Wang, K.; Sueyoshi, T.; Wang, D.D. ESG: Research Progress and Future Prospects. Sustainability 2021, 13, 11663. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pedersen, L.H.; Fitzgibbons, S.; Pomorski, L. Responsible Investing: The ESG-Efficient Frontier. J. Financ. Econ. 2021, 142, 572–597. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Petersen, H.L.; Vredenburg, H. Morals or Economics? Institutional Investor Preferences for Corporate Social Responsibility. J. Bus. Ethics 2009, 90, 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sánchez-Teba, E.M.; Benítez-Márquez, M.D.; Bermúdez-González, G.; Luna-Pereira, M.d.M. Mapping the Knowledge of CSR and Sustainability. Sustainability 2021, 13, 10106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Starks, L.T. Presidential Address: Sustainable Finance and ESG Issues—Value versus Values. J. Financ. 2023, 78, 1837–1872. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jo, H.; Harjoto, M.A. Corporate Governance and Firm Value: The Impact of Corporate Social Responsibility. J. Bus. Ethics 2011, 103, 351–383. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carnini Pulino, S.; Ciaburri, M.; Magnanelli, B.S.; Nasta, L. Does ESG Disclosure Influence Firm Performance? Sustainability 2022, 14, 7595. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gillan, S.L.; Texas Tech University, Lubbock, TX, USA; Hartzell, J.C.; University of Texas at Austin, Austin, TX, USA; Koch, A.; University of Texas at Austin, Austin, TX, USA; Starks, L.T.; University of Texas at Austin, Austin, TX, USA. Firms’ Environmental, Social and Governance (ESG) Choices, Performance and Managerial Motivation. Unpublished work. 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Mackey, A.; Mackey, T.B.; Barney, J.B. Corporate Social Responsibility and Firm Performance: Investor Preferences and Corporate Strategies. Acad. Manag. Rev. 2007, 32, 817–835. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Graves, S.B.; Waddock, S.A. Institutional Owners and Corporate Social Performance. Acad. Manag. J. 1994, 37, 1034–1046. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stuebs, M.T.; Sun, L. Corporate Social Responsibility and Firm Reputation. SSRN 2011. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aabo, T.; Giorici, I.C. Do Female CEOs Matter for ESG Scores? Glob. Financ. J. 2023, 56, 100722. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Birindelli, G.; Dell’Atti, S.; Iannuzzi, A.P.; Savioli, M. Composition and Activity of the Board of Directors: Impact on ESG Performance in the Banking System. Sustainability 2018, 10, 4699. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dyck, A.; Lins, K.V.; Roth, L.; Wagner, H.F. Do Institutional Investors Drive Corporate Social Responsibility? International Evidence. J. Financ. Econ. 2019, 131, 693–714. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, J.; Xiong, X.; Gao, Y.; Zhang, J. The Impact of Institutional Investors on ESG: Evidence from China. Account. Financ. 2023, 63, 2801–2826. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tur-Porcar, A.; Roig-Tierno, N.; Llorca Mestre, A. Factors Affecting Entrepreneurship and Business Sustainability. Sustainability 2018, 10, 452. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fisch, J.; Hamdani, A.; Solomon, S.D. The New Titans of Wall Street: A Theoretical Framework for Passive Investors. Univ. Pa. Law Rev. 2019, 168, 17–72. [Google Scholar]

- Strampelli, G. Are Passive Index Funds Active Owners: Corporate Governance Consequences of Passive Investing. San Diego Law Rev. 2018, 55, 803. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boone, A.L.; Gillan, S.; Towner, M. The Role of Proxy Advisors and Large Passive Funds in Shareholder Voting: Lions or Lambs? SSRN 2017. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Busch, T.; Scheitza, L.; Bauckloh, T.; Klein, C. ESG and Firm Value Effects of Shareholder Proposals. Acad. Manag. Proc. 2023, 2023, 10182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- D’Augusta, C.; Grossetti, F.; Imperatore, C. Environmental Awareness and Shareholder Proposals: The Case of the Deepwater Horizon Oil Spill Disaster. Corp. Gov. Int. J. Bus. Soc. 2023. ahead-of-print. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cziraki, P.; Renneboog, L.; Szilagyi, P.G. Shareholder Activism through Proxy Proposals: The European Perspective. Eur. Financ. Manag. 2010, 16, 738–777. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dikolli, S.S.; Frank, M.M.; Guo, Z.M.; Lynch, L.J. Walk the Talk: ESG Mutual Fund Voting on Shareholder Proposals. Rev. Account. Stud. 2022, 27, 864–896. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karpoff, J.M.; Malatesta, P.H.; Walkling, R.A. Corporate Governance and Shareholder Initiatives: Empirical Evidence. J. Financ. Econ. 1996, 42, 365–395. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buchanan, B.G.; Netter, J.M.; Poulsen, A.B.; Yang, T. Shareholder Proposal Rules and Practice: Evidence from a Comparison of the United States and United Kingdom. Am. Bus. Law J. 2012, 49, 739–803. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cui, H.; Chi-Moon Leung, S. The Long-Run Performance of Acquiring Firms in Mergers and Acquisitions: Does Managerial Ability Matter? J. Contemp. Account. Econ. 2020, 16, 100185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Andreou, P.C.; Karasamani, I.; Louca, C.; Ehrlich, D. The Impact of Managerial Ability on Crisis-Period Corporate Investment. J. Bus. Res. 2017, 79, 107–122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baik, B.; Brockman, P.A.; Farber, D.B.; Lee, S. (Sunghan) Managerial Ability and the Quality of Firms’ Information Environment. J. Account. Audit. Financ. 2018, 33, 506–527. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yan, Y.; Yang, X. Analyst Recommendations: Evidence on Hedge Fund Activism and Managerial Ability. Rev. Pac. Basin Financ. Mark. Policies 2022, 25, 2250004. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coles, J.L.; Daniel, N.D.; Naveen, L. Co-Opted Boards. Rev. Financ. Stud. 2014, 27, 1751–1796. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cassell, C.A.; Myers, L.A.; Schmardebeck, R.; Zhou, J. The Monitoring Effectiveness of Co-Opted Audit Committees. Contemp. Account. Res. 2018, 35, 1732–1765. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, T.; Dong, H.; Lin, C. Institutional Ownership and Audit Quality: Evidence from Russell Index Reconstitutions. SSRN 2017. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rahman, D.; Kabir, M.; Oliver, B. Does Exposure to Product Market Competition Influence Insider Trading Profitability? J. Corp. Financ. 2021, 66, 101792. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zaman, R.; Atawnah, N.; Nadeem, M.; Bahadar, S.; Shakri, I.H. Do Liquid Assets Lure Managers? Evidence from Corporate Misconduct. J. Bus. Financ. Account. 2022, 49, 1425–1453. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Demerjian, P.; Lev, B.; McVay, S. Quantifying Managerial Ability: A New Measure and Validity Tests. Manag. Sci. 2012, 58, 1229–1248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Proffitt, W.T.; Spicer, A. Shaping the Shareholder Activism Agenda: Institutional Investors and Global Social Issues. Strateg. Organ. 2006, 4, 165–190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Variable | Description |

|---|---|

| Band | An indicator of whether the company’s end-of-May market capitalization is adequately near the Rusell 1000/2000 cutoff such that the firm will remain in the same index. Source: CRSP and FTSE Russell |

| Board Co-option | Percentage of directors that are appointed following the hiring of the CEO (Coles et al., [75]). Source: https://sites.temple.edu/lnaveen/data/, accessed on 5 November 2023 |

| Indicator for Any Proposal | An indicator that equals one if there were one or more proposals sponsored in a firm-year. Source: ISS |

| Indicator for GOV Proposal | An indicator that equals one if there were one or more governance-related proposals sponsored in a firm-year. Source: ISS |

| Indicator for SRI Proposal | An indicator that equals one if there were one or more SRI proposals sponsored in a firm-year. Source: ISS |

| Indicator for Withdrawn | An indicator of if there is any proposal being withdrawn in a firm-year. Source: ISS |

| Leverage | Measured as the ratio of debt in current liabilities plus long-term debt to total assets. Source: Compustat |

| Ln(Mktcap) | The logarithm of total market cap. Source: CRSP |

| Ln(Floatmc) | The logarithm of float-adjusted market cap. Source: FTSE Russell |

| Managerial Ability | Top management team’s managerial ability (Demerjian et al., [80]). Source: https://peterdemerjian.weebly.com/managerialability.html, accessed on 5 November 2023 |

| Passive% | Percent of passive ownership. Source: Thomson Reuters and CRSP |

| R2000 | An indicator of if the company is included in the Russell 2000. Source: FTSE Russell |

| ROA | The ratio of net income to total assets. Source: Compustat |

| PPE | Sum (property, plant, and equipment) scaled by total assets. Source: Compustat |

| Total Proposal Total SRI Proposal Total GOV Proposal | The total number of shareholder proposals in a firm-year. Source: ISS The total number of socially responsible investing proposals in a firm-year. Source: ISS The total number of governance proposals in a firm-year. Source: ISS |

| Total Withdrawn | The total number of proposals withdrawn in a firm-year. Source: ISS |

| Vote-for% | The voting percentage that is in support of the proposal. Source: ISS |

| Variables | N | Mean | SD | P25 | Median | P75 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Total Proposal | 29,230 | 0.340 | 1.116 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Total SRI Proposal | 29,230 | 0.127 | 0.547 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Total GOV Proposal | 29,230 | 0.208 | 0.735 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Indicator for Any Proposal | 29,230 | 0.163 | 0.369 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Indicator for SRI Proposal | 29,230 | 0.080 | 0.272 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Indicator for GOV Proposal | 29,230 | 0.123 | 0.329 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Passive% | 29,065 | 0.105 | 0.056 | 0.067 | 0.096 | 0.134 |

| Ln(Mktcap) | 29,230 | 21.115 | 1.594 | 19.869 | 20.918 | 22.105 |

| Total Withdrawn | 29,230 | 0.083 | 0.347 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Indicator for Withdrawn | 29,230 | 0.169 | 0.375 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Vote-for% | 5516 | 33.164 | 22.900 | 13.300 | 31.300 | 45.400 |

| ROA | 29,230 | 0.087 | 0.183 | 0.037 | 0.103 | 0.159 |

| Leverage | 29,230 | 0.227 | 0.230 | 0.040 | 0.183 | 0.344 |

| PPE | 29,230 | 0.223 | 0.243 | 0.036 | 0.126 | 0.332 |

| Managerial Ability | 21,218 | 0.004 | 0.152 | −0.087 | −0.035 | 0.049 |

| Board Co-option | 12,910 | 0.466 | 0.307 | 0.2 | 0.444 | 0.714 |

| (1) | (2) | (3) | (4) | (5) | (6) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Total Proposal | Total SRI Proposal | Total GOV Proposal | Indicator for Any Proposal | Indicator for SRI Proposal | Indicator for GOV Proposal | |

| Passive% | 0.839 *** | 0.406 *** | 0.458 *** | 0.264 *** | 0.119 ** | 0.153 ** |

| (4.61) | (4.19) | (3.33) | (3.25) | (2.13) | (2.04) | |

| Ln(Mktcap) | −0.849 *** | −0.408 ** | −0.229 | −0.404 *** | −0.208 *** | −0.318 *** |

| (−2.60) | (−2.29) | (−1.21) | (−6.55) | (−3.58) | (−5.45) | |

| Ln(Mktcap)2 | 0.023 *** | 0.011 ** | 0.007 | 0.011 *** | 0.006 *** | 0.008 *** |

| (2.80) | (2.41) | (1.49) | (6.96) | (3.83) | (5.81) | |

| ROA | −0.108 ** | −0.017 | −0.097 ** | −0.042 ** | −0.025 *** | −0.044 ** |

| (−2.34) | (−1.01) | (−2.47) | (−2.28) | (−2.68) | (−2.42) | |

| Leverage | 0.102 ** | −0.003 | 0.097 *** | 0.042 ** | −0.008 | 0.037 ** |

| (2.24) | (−0.15) | (2.66) | (2.43) | (−0.74) | (2.31) | |

| PPE | 0.228 | 0.150 * | 0.080 | 0.075 * | 0.094 *** | 0.037 |

| (1.59) | (1.88) | (0.88) | (1.72) | (2.71) | (0.89) | |

| Year FE | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Firm FE | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| N | 29,230 | 29,230 | 29,230 | 29,230 | 29,230 | 29,230 |

| R-sq | 0.710 | 0.600 | 0.620 | 0.555 | 0.484 | 0.517 |

| (1) | (2) | (3) | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Total Proposal | Total SRI Proposal | Total GOV Proposal | |

| Passive% | 0.740 *** | 0.404 *** | 0.369 ** |

| (3.43) | (3.27) | (2.34) | |

| Managerial Ability | 0.413 ** | 0.253 ** | 0.220 * |

| (2.30) | (2.17) | (1.85) | |

| Passive%*Managerial Ability | −4.384 *** | −2.696 *** | −2.387 ** |

| (−2.72) | (−2.69) | (−2.25) | |

| Ln(Mktcap) | −1.032 ** | −0.520 ** | −0.330 |

| (−2.47) | (−2.25) | (−1.41) | |

| Ln(Mktcap)2 | 0.027 *** | 0.013 ** | 0.010 |

| (2.63) | (2.35) | (1.63) | |

| ROA | −0.163 ** | −0.026 | −0.138 ** |

| (−2.26) | (−0.77) | (−2.53) | |

| Leverage | 0.060 | −0.013 | 0.060 |

| (1.12) | (−0.48) | (1.38) | |

| PPE | 0.203 | 0.105 | 0.104 |

| (1.17) | (1.10) | (0.99) | |

| Year FE | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Firm FE | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| N | 21,218 | 21,218 | 21,218 |

| R-squared | 0.713 | 0.609 | 0.618 |

| (1) | (2) | (3) | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Total Proposal | Total SRI Proposal | Total GOV Proposal | |

| Passive% | 1.168 * | 1.126 *** | 0.485 |

| (1.79) | (2.67) | (1.14) | |

| Board Co-option | −0.351 ** | −0.027 | −0.317 *** |

| (−2.57) | (−0.35) | (−3.46) | |

| Passive%*Board Co-option | 2.196 ** | 0.300 | 1.808 *** |

| (2.58) | (0.64) | (3.17) | |

| Ln(Mktcap) | −0.707 | −0.510 | 0.176 |

| (−0.88) | (−1.13) | (0.42) | |

| Ln(Mktcap)2 | 0.021 | 0.014 | −0.001 |

| (1.09) | (1.26) | (−0.10) | |

| ROA | −0.529 ** | −0.156 | −0.422 ** |

| (−2.17) | (−1.38) | (−2.33) | |

| Leverage | 0.101 | −0.086 | 0.164 |

| (0.72) | (−1.30) | (1.44) | |

| PPE | 0.228 | 0.185 | 0.019 |

| (0.57) | (0.82) | (0.08) | |

| Year FE | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Firm FE | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| N | 12,910 | 12,910 | 12,910 |

| R-squared | 0.713 | 0.604 | 0.626 |

| (1) | (2) | |

|---|---|---|

| Total Withdrawn | Indicator for Withdrawn | |

| Passive% | 0.208 *** | 0.276 *** |

| (3.05) | (3.40) | |

| Ln(Mktcap) | −0.360 *** | −0.436 *** |

| (−3.60) | (−6.79) | |

| Ln(Mktcap)2 | 0.009 *** | 0.012 *** |

| (3.76) | (7.16) | |

| ROA | −0.003 | −0.039 ** |

| (−0.23) | (−2.10) | |

| Leverage | 0.024 * | 0.057 *** |

| (1.67) | (3.15) | |

| PPE | 0.053 | 0.086 ** |

| (1.27) | (1.97) | |

| Year FE | Yes | Yes |

| Firm FE | Yes | Yes |

| N | 29,230 | 29,230 |

| R-sq | 0.337 | 0.555 |

| (1) | (2) | (3) | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Vote-for% (SRI) | Vote-for% (GOV) | Vote-for% (All) | |

| Passive% | 11.566 *** | 5.546 ** | 7.442 *** |

| (5.77) | (2.26) | (3.45) | |

| Ln(Mktcap) | 31.161 *** | 23.186 *** | 19.147 *** |

| (2.83) | (3.40) | (2.77) | |

| Ln(Mktcap)2 | −0.684 *** | −0.581 *** | −0.492 *** |

| (−2.89) | (−3.99) | (−3.30) | |

| ROA | −6.597 | 8.557 | −0.345 |

| (−1.29) | (1.50) | (−0.08) | |

| Leverage | −5.166 ** | −8.523 ** | −8.221 *** |

| (−2.34) | (−2.37) | (−3.54) | |

| PPE | 6.303 *** | −2.031 | −3.553 * |

| (2.87) | (−0.83) | (−1.66) | |

| Year FE | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Firm FE | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| N | 1886 | 3630 | 5516 |

| R-sq | 0.186 | 0.122 | 0.129 |

| (1) | (2) | (3) | |

|---|---|---|---|

| BHAR (All Proposal) | BHAR (SRI Proposal) | BHAR (GOV Proposal) | |

| Passive% | 0.576 ** | 0.617 ** | 0.611 ** |

| (2.46) | (1.98) | (2.22) | |

| Ln(Mktcap) | 0.046 | 0.281 *** | −0.031 |

| (0.58) | (2.59) | (−0.32) | |

| Ln(Mktcap)2 | −0.001 | −0.006 ** | 0.001 |

| (−0.52) | (−2.54) | (0.37) | |

| ROA | −0.169 * | −0.174 ** | −0.148 |

| (−1.93) | (−2.02) | (−1.27) | |

| Leverage | 0.019 | 0.041 | 0.003 |

| (0.58) | (1.17) | (0.07) | |

| PPE | −0.021 | −0.021 | −0.019 |

| (−0.94) | (−0.71) | (−0.69) | |

| Year FE | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Firm FE | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| N | 9810 | 3708 | 6102 |

| R-sq | 0.030 | 0.039 | 0.028 |

| (1) | (2) | (3) | (4) | (5) | (6) | (7) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Passive% | Total Proposal | Total SRI Proposal | Total GOV Proposal | Indicator for Any Proposal | Indicator for SRI Proposal | Indicator for GOV Proposal | |

| R2000it | 0.034 *** | ||||||

| (14.33) | |||||||

| Passive% | 2.428 *** | 0.938 ** | 1.436 *** | 1.494 *** | 0.636 * | 1.161 *** | |

| (3.38) | (2.36) | (2.71) | (2.79) | (1.83) | (2.66) | ||

| Polynomial order | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 |

| Band | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Ln(Floatmc) | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Year FE | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| N | 9660 | 9660 | 9660 | 9660 | 9660 | 9660 | 9660 |

| R-sq | 0.312 | 0.039 | 0.017 | 0.026 | 0.043 | 0.020 | 0.027 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Yang, L.; Huang, X.; Song, X. The Role of Passive Investors in Corporate Governance and Socially Responsible Investing: Evidence from Shareholder Proposals. Sustainability 2024, 16, 416. https://doi.org/10.3390/su16010416

Yang L, Huang X, Song X. The Role of Passive Investors in Corporate Governance and Socially Responsible Investing: Evidence from Shareholder Proposals. Sustainability. 2024; 16(1):416. https://doi.org/10.3390/su16010416

Chicago/Turabian StyleYang, Lukai, Xinhui Huang, and Xiaochuan Song. 2024. "The Role of Passive Investors in Corporate Governance and Socially Responsible Investing: Evidence from Shareholder Proposals" Sustainability 16, no. 1: 416. https://doi.org/10.3390/su16010416

APA StyleYang, L., Huang, X., & Song, X. (2024). The Role of Passive Investors in Corporate Governance and Socially Responsible Investing: Evidence from Shareholder Proposals. Sustainability, 16(1), 416. https://doi.org/10.3390/su16010416