Impact of Policy Design on Plastic Waste Reduction in Africa

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

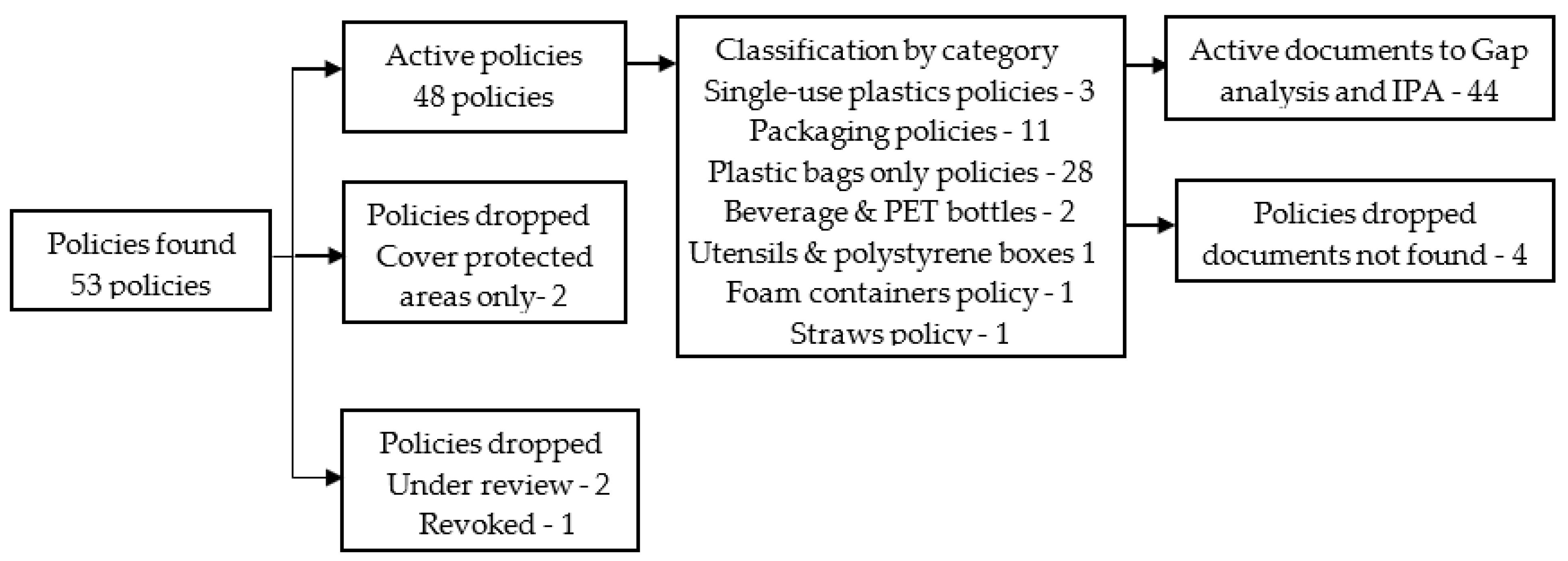

2.1. Policy Identification and Selection Criteria

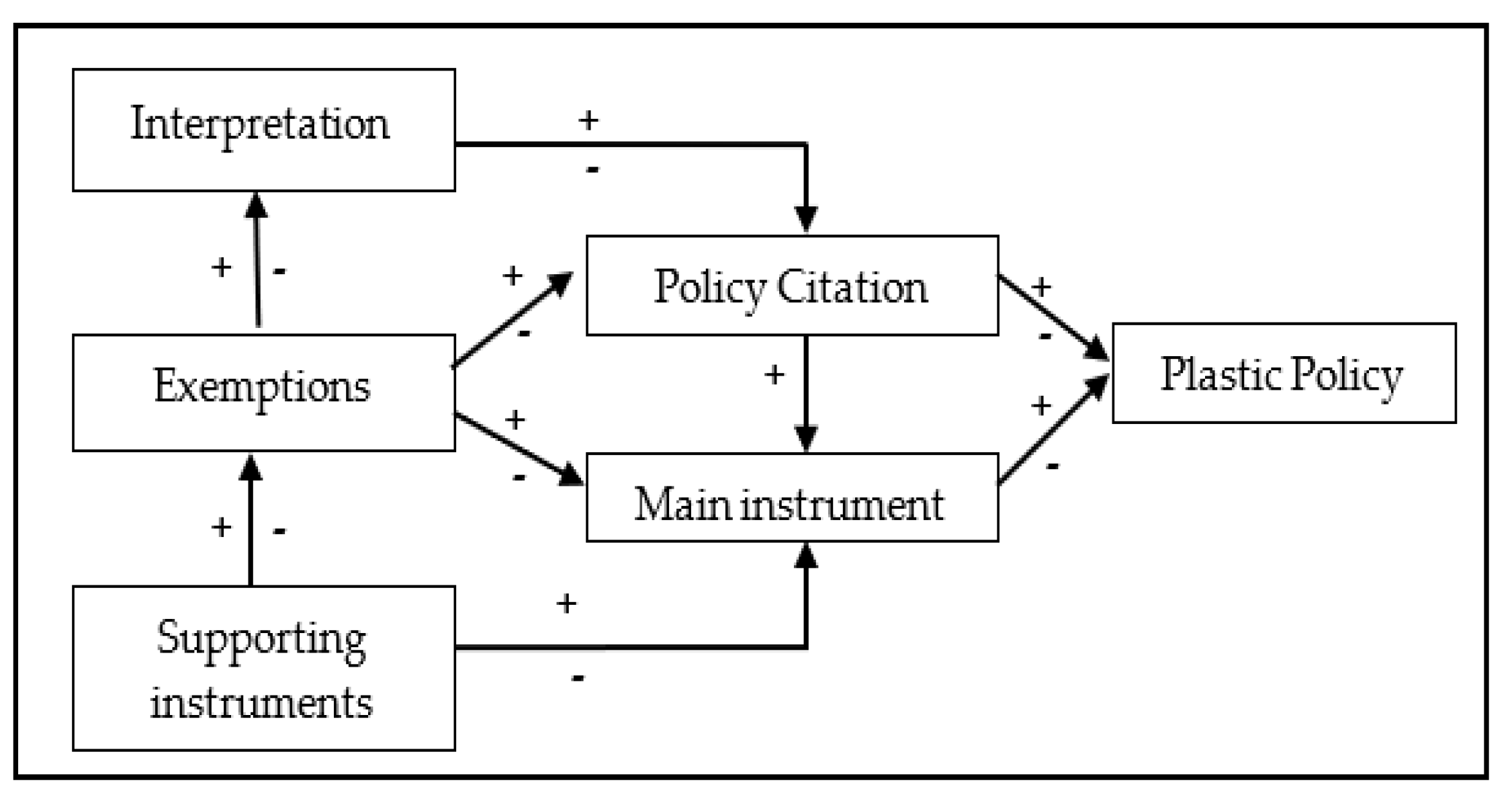

2.2. Data Analysis

3. Results and Discussions

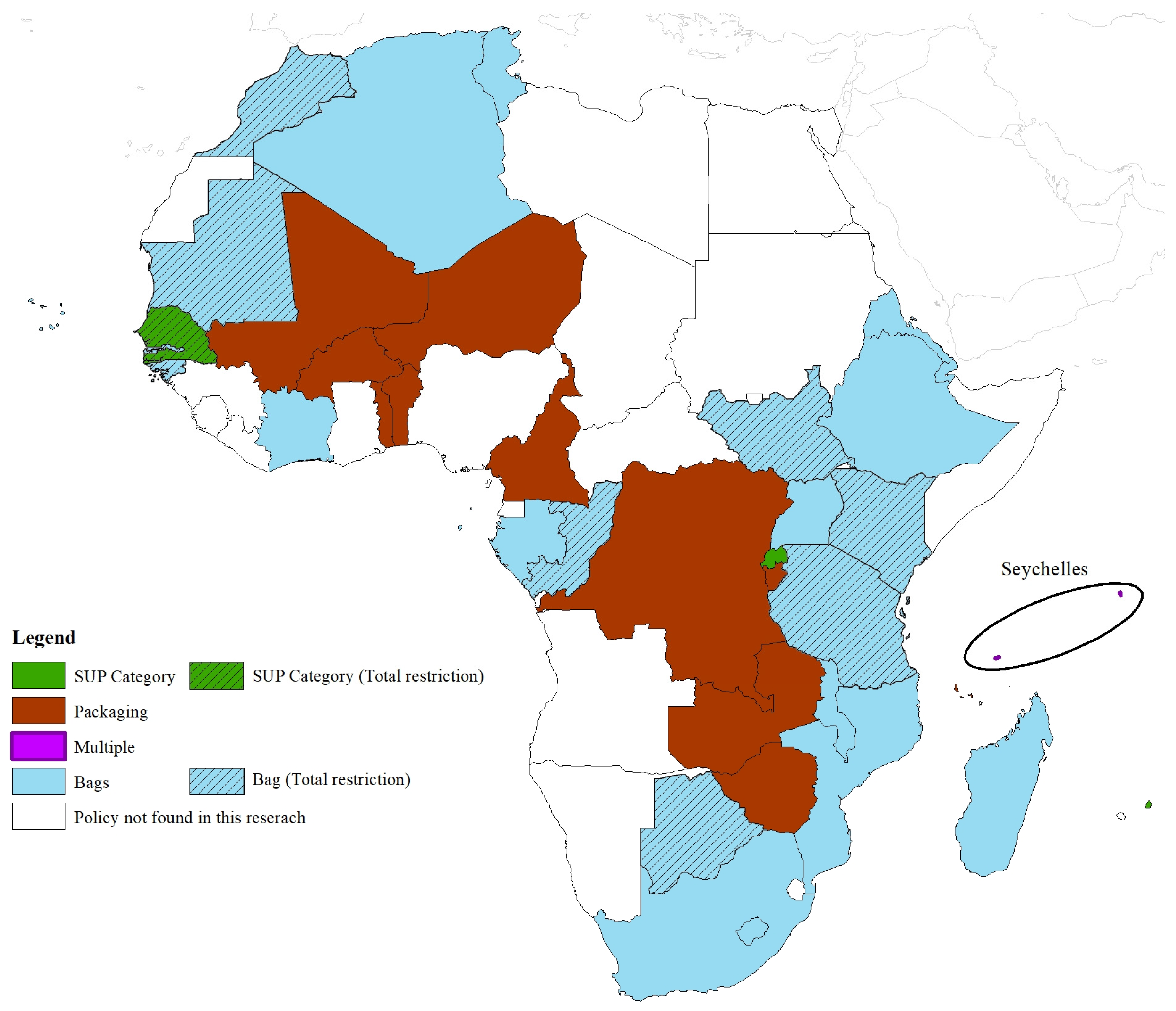

3.1. Overview of Plastic Policies in Africa

3.2. Scope of SUP Policies

3.3. Scope of Packaging Policies

3.4. Scope of Product Policies

3.4.1. SUPB Policies

3.4.2. Multiple Product Policies: The Case of Seychelles

3.5. Complementarity of Policy Instruments

3.6. Implication of Status, Scope, and Variability of Plastic Policies to Waste Prevention

3.6.1. Policy Instrument Sources

3.6.2. Policy Scope Sources

3.6.3. Exemption Related Sources

3.6.4. Transboundary Flow and Sources

4. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Ncube, L.K.; Ude, A.U.; Ogunmuyiwa, E.N.; Zulkifli, R.; Beas, I.N. An Overview of Plastic waste Generation and Management in Food Packaging Industries. Recycling 2021, 6, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- UNEP. Single-Use Plastics, A Roadmap for Sustainability; UNEP: Nairobi, Kenya, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Xanthos, D.; Walker, T.R. International Policies to Reduce Plastic Marine Pollution from Single-Use Plastics (Plastic Bags and Microbeads): A Review. Mar. Pollut. Bull. 2017, 118, 17–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Charles, D.; Kimman, L.; Saran, N. The Plastic Waste Makers Index; Minderoo Foundation: Broadway Nedlands, WA, Australia, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Geyer, R.; Jambeck, J.R.; Law, K.L. Production, Use, and Fate of All Plastics Ever Made. Sci. Adv. 2017, 3, e1700782. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Babayemi, J.O.; Nnorom, I.C.; Osibanjo, O.; Weber, R. Ensuring Sustainability in Plastics Use in Africa: Consumption, Waste Generation, and Projections. Environ. Sci. Eur. 2019, 31, 1–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lebreton, L.; Andrady, A. Future Scenarios of Global Plastic Waste Generation and Disposal. Palgrave Commun. 2019, 5, 6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaza, S.; Lisa, Y.; Perinaz, B.; Van Woerden, F. What A Waste 2.0: A Global Snapshot of Solid Waste Management to 2050; World Bank: Washington, DC, USA, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Jambeck, J.R.; Geyer, R.; Wilcox, C.; Siegler, T.R.; Perryman, M.; Andrady, A.; Narayan, R.; Law, K.L. Plastic Waste Inputs from Land into the Ocean. Science 2015, 347, 768–771. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adyel, T.M. Accumulation of Plastic Waste during COVID-19. Science 2020, 369, 1314–1315. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Benson, N.U.; Fred-Ahmadu, O.H.; Bassey, D.E.; Atayero, A.A. COVID-19 Pandemic and Emerging Plastic-Based Personal Protective Equipment Waste Pollution and Management in Africa. J. Environ. Chem. Eng. 2021, 9, 105222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ayeleru, O.O.; Dlova, S.; Akinribide, O.J.; Ntuli, F.; Kupolati, W.K.; Marina, P.F.; Blencowe, A.; Olubambi, P.A. Challenges of Plastic Waste Generation and Management in Sub-Saharan Africa: A Review. Waste Manag. 2020, 110, 24–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muposhi, A.; Mpinganjira, M.; Wait, M. Considerations, Benefits and Unintended Consequences of Banning Plastic Shopping Bags for Environmental Sustainability: A Systematic Literature Review. Waste Manag. Res. 2022, 40, 248–261. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Knoblauch, D.; Mederake, L.; Stein, U. Developing Countries in the Lead-What Drives the Diffusion of Plastic Bag Policies? Sustainability 2018, 10, 1994. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Behuria, P. Ban the (Plastic) Bag? Explaining Variation in the Implementation of Plastic Bag Bans in Rwanda, Kenya and Uganda. Environ. Plan. C Politics Space 2021, 39, 1791–1808. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bezerra, J.C.; Walker, T.R.; Clayton, C.A.; Adam, I. Single-Use Plastic Bag Policies in the Southern African Development Community. Environ. Chall. 2021, 3, 100029. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sadan, Z.; de Kock, L. Plastic Pollution in Africa Identifying Policy Gaps and Opportunities; WWF Kenya: Cape Town, South Africa, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Adam, I.; Walker, T.R.; Bezerra, J.C.; Clayton, A. Policies to Reduce Single-Use Plastic Marine Pollution in West Africa. Mar. Policy 2020, 116, 103928. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alpizar, F.; Carlsson, F.; Lanza, G.; Carney, B.; Daniels, R.C.; Jaime, M.; Ho, T.; Nie, Z.; Salazar, C.; Tibesigwa, B.; et al. A Framework for Selecting and Designing Policies to Reduce Marine Plastic Pollution in Developing Countries. Environ. Sci. Policy 2020, 109, 25–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cornago, E.; Börkey, P.; Brown, A. Preventing Single-Use Plastic Waste: Implications of Different Policy Approaches; OECD: Paris, France, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Schnurr, R.E.J.; Alboiu, V.; Chaudhary, M.; Corbett, R.A.; Quanz, M.E.; Sankar, K.; Srain, H.S.; Thavarajah, V.; Xanthos, D.; Walker, T.R. Reducing Marine Pollution from Single-Use Plastics (SUPs): A Review. Mar. Pollut. Bull. 2018, 137, 157–171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dikgang, J.; Visser, M. Behavioural Response to Plastic Bag Legislation in Botswana. S. Afr. J. Econ. 2012, 80, 123–133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Omondi, I.; Asari, M. A Study on Consumer Consciousness and Behavior to the Plastic Bag Ban in Kenya. J. Mater. Cycles Waste Manag. 2021, 23, 425–435. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nyathi, B.; Togo, C.A. Overview of Legal and Policy Framework Approaches for Plastic Bag Waste Management in African Countries. J. Environ. Public Health 2020, 2020, 8892773. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akenji, L.; Bengtsson, M.; Kato, M.; Hengesbaugh, M.; Hotta, Y.; Aoki-Suzuki, C.; Gamaralalage, P.J.D.; Liu, C. Circular Economy and Plastics: A Gap-Analysis in ASEAN Member States; European Commission Directorate General for Environment and Directorate General for International Cooperation and Development: Jakarta, Indonesia, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Farrelly, T.A.; Borrelle, S.B.; Fuller, S. The Strengths and Weaknesses of Pacific Islands Plastic Pollution Policy Frameworks. Sustainability 2021, 13, 1252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- UNEP. The Role of Packaging Regulations and Standards in Driving The Circular Economy; UNEP: Bangkok, Thailand, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- de Wee, G. Comparative Policy Analysis and the Science of Conceptual Systems: A Candidate Pathway to a Common Variable. Found. Sci. 2022, 27, 287–304. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ferraro, G.; Failler, P. Governing Plastic Pollution in the Oceans: Institutional Challenges and Areas for Action. Environ. Sci. Policy 2020, 112, 453–460. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Diana, Z.; Vegh, T.; Karasik, R.; Bering, J.; Llano Caldas, D.J.; Pickle, A.; Rittschof, D.; Lau, W.; Virdin, J. The Evolving Global Plastics Policy Landscape: An Inventory and Effectiveness Review. Environ. Sci. Policy 2022, 134, 34–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Knoblauch, D.; Mederake, L. Government Policies Combatting Plastic Pollution. Curr. Opin. Toxicol. 2021, 28, 87–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nielsen, T.D.; Holmberg, K.; Stripple, J. Need a Bag? A Review of Public Policies on Plastic Carrier Bags—Where, How and to What Effect? Waste Manag. 2019, 87, 428–440. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Deme, G.G.; Ewusi-Mensah, D.; Olagbaju, O.A.; Okeke, E.S.; Okoye, C.O.; Odii, E.C.; Ejeromedoghene, O.; Igun, E.; Onyekwere, J.O.; Oderinde, O.K.; et al. Macro Problems from Microplastics: Toward a Sustainable Policy Framework for Managing Microplastic Waste in Africa. Sci. Total Environ. 2022, 804, 150170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tencati, A.; Pogutz, S.; Moda, B.; Brambilla, M.; Cacia, C. Prevention Policies Addressing Packaging and Packaging Waste: Some Emerging Trends. Waste Manag. 2016, 56, 35–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Wee, G.; Asmah-Andoh, K. Model for Overcoming Policy Analysis Limitation and Implementation Challenges: Integrative Propositional Analysis of South African National Mental Health Policy Framework and Strategic Plan 2013–2020. Int. J. Public Adm. 2022, 45, 658–674. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wallis, S.E. Understanding and improving the usefulness of conceptual systems: An Integrative Propositional Analysis-based perspective on levels of structure and emergence. Syst. Res. Behav. Sci. 2021, 38, 426–447. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wright, B.; Wallis, S.E. Using integrative propositional analysis for evaluating entrepreneurship theories. SAGE Open 2015, 5, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karasik, R.; Virdin, J.; Diana, Z. Plastics Policy Inventory. Available online: https://nicholasinstitute.duke.edu/plastics-policy-inventory (accessed on 23 February 2023).

- GPML. The Global Partnership on Plastic Pollution and Marine Litter Digital Platform. Available online: https://digital.gpmarinelitter.org/ (accessed on 23 February 2023).

- Oceng, R.; Andarani, P.; Zaman, B. Quantification of plastic litter and microplastics in African water bodies toward closing the loop of plastic consumption. Acadlore Trans. Geosci. 2023, 2, 94–112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ocean Conservancy. Building A Clean Swell; Ocean Conservancy: Washington, DC, USA, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- ten Brink, P.; Schweitzer, J.; Watkins, E. Plastics Marine Litter and the Circular Economy; Institute for European Environmental Policy: Brussels, Belgium, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Li, Y.; Wang, B. Go Green and Recycle: Analyzing the Usage of Plastic Bags for Shopping in China. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2021, 18, 12537. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Policy Element | Term | Definition as Applied in the Research |

|---|---|---|

| Title | Policy title as stated in the policy document | |

| Citation | Statement in a policy document introducing what a policy entails | |

| Policy type | Category policy | Policy that covers a family of single-use plastic such as SUP policy or packaging policy |

| SUP policy | Policy that covers all single-use plastics including packaging and SUP items. | |

| Packaging policy | Policy that covers both primary and secondary plastic packaging. | |

| Product policy | Policy that covers a single plastic product or item made fully or partially from plastic | |

| Instrument | Mechanism to reduce or manage the plastic problem | |

| Regulatory instrument | Command and control instruments in form of bans | |

| Total ban | Prohibition on the consumption of all SUP item(s) in all forms and restrictions | |

| Partial instrument | Prohibition on the consumption of SUP item(s) with certain exemptions or restrictions. | |

| Economic instrument | Monetary instruments such as taxes and levies on SUP items | |

| Main instrument | Policy mechanism to reduce and manage plastic pollution identified by policy title or citation. | |

| Supporting instrument | Any other mechanism to reduce or manage plastic pollution mentioned within the policy document. | |

| Interpretation | The definition of terms as used in the policy document and the context of understanding a policy | |

| Single-use plastic items (SUP Items) | Products include packaging, cutlery (straws, knives, plates, stirrers, etc.), beverage cups, cotton buds, cigarette butts, balloons, balloon sticks, wet wipes, and sanitary items. | |

| Plastic packaging | Items used for protection, containment, handling, delivery, and presentation of goods from producers to consumers. | |

| Product definition | Refers to the description of an item, fully or partially made from plastic. Product names were also considered as product definition | |

| Undefined SUP | SUP that falls under category definition but are unmentioned or unlisted in a policy, hence have unclarified status. | |

| Primary packaging | Packaging in direct contact with the product, especially from manufacturing and includes bottles, containers, food packaging, food containers, beverage containers (PET bottles), wrappers, and packets. | |

| Secondary packaging (Bags) | Packaging used to carry goods from retail centers. Most include carrier bags, and flimsy/barrier bags | |

| Plastic carrier bags | Bags with or without handles used to carry products from retail centers to a destination by consumers | |

| Barriers bags | Thin or film bags at retail centers used for packaging, safety and grouping products | |

| Exemptions | SUP defined and permitted for circulation under the scope other controlled SUP. |

| Countries | Plastic Policies | Plastic Products |

|---|---|---|

| Seychelles | 5 | 6 |

| Mauritius | 3 | 8 |

| Senegal | 1 | 8 |

| DRC | 1 | 6 |

| Togo | 1 | 2 |

| Zambia | 1 | 3 |

| Zimbabwe | 2 | 3 |

| Benin; Mali | 2 | 1 |

| Other Countries | 1 | 1 |

| Secondary Packaging | Primary Packaging | Single Use Plastic Items | |||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Country | Year of Adoption | Policy Instrument | Category/ Product Definition | Policy Coverage | Carrier Bags | Barrier Bags | Beverage & PET Bottles | Containers | Sachets Wrappers | Non-Food Packaging | Beverage Cup | Cutlery | Plates | Straws | Stirrers | Lids | |||

| Mauritius | 2020 | NBB | Yes/Yes | SUP | ✔ | E | ✔ | o | o | E | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ | |||

| Senegal | 2020 | Ban | Yes/Yes | SUP | ✔ | o | o | o | ✔ | o | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ | |||

| Rwanda | 2019 | NBB | Yes/No | SUP | ✔ | o | Out of policy | o | o | o | o | o | o | ||||||

| Mali | 2001 | EPR/NBB | No/No | Packaging | ✔ | o | o | o | o | o | Out of policy | ||||||||

| Benin | 2004 | Tax | Yes/Yes | Packaging | ✔ | o | E | E | E | E | |||||||||

| Zimbabwe | 2010 | TB/Ban | Yes/Yes | Packaging /PS * | ✔ | ✔ | E | E | E | E | |||||||||

| Togo | 2011 | NBB | No/No | Packaging | ✔ | o | o | o | ✔ | o | |||||||||

| Cameroon | 2012 | NBB/TB | Yes/No | Packaging | ✔ | ✔ | o | o | o | o | |||||||||

| Burkina Faso | 2014 | NBB | Yes/No | Packaging | ✔ | o | E | E | E | E | |||||||||

| DRC | 2018 | NBB | No/Yes | Packaging | ✔ | ✔ | E | E | ✔ | ✔ | |||||||||

| Burundi | 2018 | NBB | Yes/No | Packaging | ✔ | o | E | E | E | E | |||||||||

| Zambia | 2018 | EPR/TB | Yes/Yes | Packaging | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ | E | E | E | |||||||||

| Seychelles | 2013–2020 | NBB/EPR | Yes | Multiple products | ✔ | E | ✔ | Out of policy | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ | Out of policy | ||||||

| Restriction Scope | Instrument | Countries |

|---|---|---|

| Ban on carrier and barrier bags | Total ban | Kenya, Mauritania, Tanzania, Congo |

| Non-biodegradable ban | Cameroon, DRC, Eritrea | |

| Thickness ban | Zambia, Zimbabwe, Ethiopia, Madagascar, Uganda, Tunisia | |

| Ban on carrier bag with barrier bag status undefined | Total ban | Senegal |

| Non-biodegradable ban | Rwanda, Togo, Burundi, Burkina Faso, Côte d’Ivoire, Gabon | |

| Thickness ban | Mali | |

| Ban on carrier bag with exemption on barrier bags | Total ban | Mauritius, Botswana, Cape Verde, Gambia, Morocco, Seychelles |

| Non-biodegradable ban | São Tomé and Príncipe, | |

| Thickness ban | Malawi | |

| Ban on plastic bag imports | Non-biodegradable ban | Djibouti |

| Charge on carrier and barrier bags | South Africa (Also applies a thickness ban) | |

| Charge on carrier bags only | Benin, Algeria, Mozambique, Lesotho |

| Supporting Instruments | ||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Country | Policy Target | Main Instrument | Charge | EPR | Source Registration | Source Labelling | Source Reporting | Recycling | Product Design | Overpackaging | Polymer Restrictions | Degradability Restrictions | Awareness | Comment |

| Mauritius | SUP | NBB | - | - | ✔ | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - |

| Bags | NBB | - | - | ✔ | ✔ | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | Oxo ban | |

| PET Bottle | EPR | - | - | ✔ | - | ✔ | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | |

| Senegal | SUP | Ban | - | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ | - | - | - | - | Waste import ban |

| Rwanda | SUP | NBB | - | ✔ | ✔ | - | - | ✔ | - | - | - | ✔ | - | - |

| Togo | Packaging | NBB | - | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ | - | - | - | - | - |

| Benin | Packaging | Tax | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - |

| Bags | Ban | - | ✔ | - | - | - | ✔ | - | - | - | - | - | - | |

| Cameroon | Packaging | NBB/TB | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | |

| DRC | Packaging | NBB | - | ✔ | ✔ | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - |

| Burundi | Packaging | NBB | - | ✔ | ✔ | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - |

| Burkina Faso | Packaging | NBB | - | - | ✔ | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - |

| Zimbabwe | Packaging | TB | ✔ | - | ✔ | ✔ | - | ✔ | - | - | - | - | - | |

| Polystyrene | Ban | - | ✔ | - | - | - | - | - | - | ✔ | - | - | - | |

| Mali | Packaging | EPR | - | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ | - | ✔ | ✔ | - | - | - | - | |

| Bags | NBB | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | |

| Zambia | Packaging | EPR/TB | - | - | ✔ | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - |

| Supporting Instruments in Plastic Policies in Africa | ||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Country | Policy Target | Main Instrument | Charge | EPR | Source Registration | Source Labelling | Source Reporting | Recycling | Product Design | Overpackaging | Polymer Restrictions | Degradability Restrictions | Awareness | Comment |

| Seychelles | Bags | NBB | - | - | ✔ | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - |

| Utensil and PS boxes | NBB | - | - | ✔ | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | |

| Straws | NBB | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | |

| PET bottle | EPR | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | |

| Beverage Container | EPR | - | - | - | - | - | - | ✔ | - | - | - | - | - | |

| Algeria | Bags | Tax | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - |

| Botswana | Bags | Ban | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - |

| Cape Verde | Bags | NBB | - | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ | - | - | - | - | - | - | ✔ | Reduction Targets |

| Côte d’Ivoire | Bags | NBB | - | ✔ | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - |

| Djibouti | Bags | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | Ban only |

| Republic of the Congo | Bags | Ban | - | - | ✔ | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | Food only/Oxo ban |

| Ethiopia | Bags | TB | - | - | ✔ | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | Biodegradability labels |

| Eritrea | Bags | NBB/TB | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - |

| Gabon | Bags | NRB | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - |

| Gambia | Bags | Ban | - | ✔ | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - |

| Kenya | Bags | Ban | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - |

| Lesotho | Bags | Tax | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - |

| Madagascar | Bags | TB | - | - | - | ✔ | - | - | - | - | - | - | ✔ | - |

| Malawi | Bags | TB | - | - | - | ✔ | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - |

| Mauritania | Bags | Ban | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - |

| Morocco | Bags | Ban | - | - | - | ✔ | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - |

| Mozambique | Bags | TB | ✔ | - | ✔ | ✔ | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - |

| South Africa | Bags | TB | ✔ | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - |

| Uganda | Bags | TB | - | ✔ | - | ✔ | - | ✔ | - | - | - | - | - | - |

| Tanzania | Bags | Ban | - | ✔ | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - |

| Tunisia | Bags | TB | - | - | - | ✔ | - | - | - | - | - | — | - | Oxo ban |

| São Tomé and Príncipe | Bags | NBB | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | ✔ | - |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Omondi, I.; Asari, M. Impact of Policy Design on Plastic Waste Reduction in Africa. Sustainability 2024, 16, 4. https://doi.org/10.3390/su16010004

Omondi I, Asari M. Impact of Policy Design on Plastic Waste Reduction in Africa. Sustainability. 2024; 16(1):4. https://doi.org/10.3390/su16010004

Chicago/Turabian StyleOmondi, Isaac, and Misuzu Asari. 2024. "Impact of Policy Design on Plastic Waste Reduction in Africa" Sustainability 16, no. 1: 4. https://doi.org/10.3390/su16010004

APA StyleOmondi, I., & Asari, M. (2024). Impact of Policy Design on Plastic Waste Reduction in Africa. Sustainability, 16(1), 4. https://doi.org/10.3390/su16010004