How Is the Utilities Sector Contributing to Building a Sustainable Future? A Systematic Literature Review of Sustainability Practices

Abstract

:1. Introduction

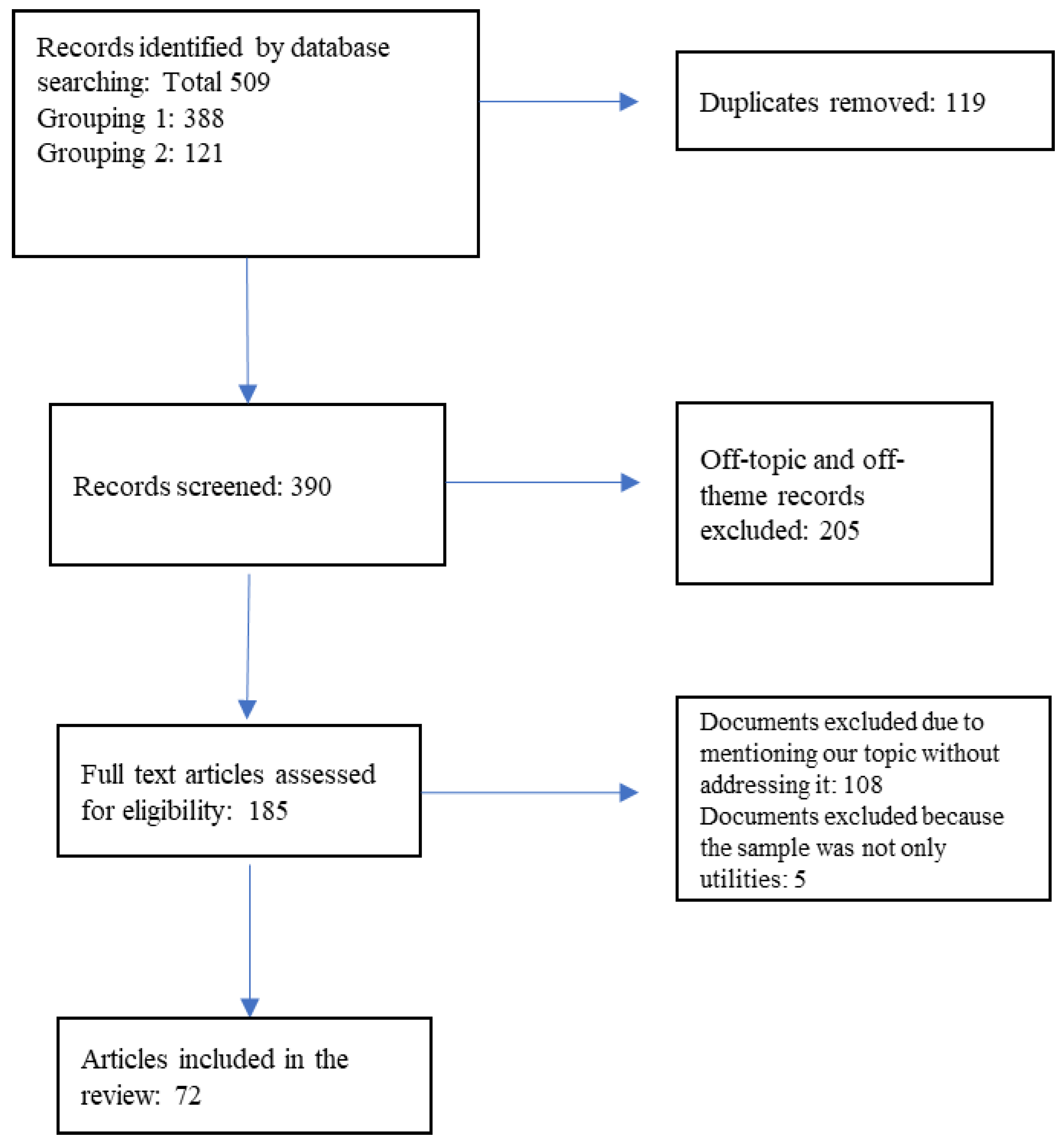

2. Methodology

- -

- Group 1: includes all documents on utility companies and sustainability issues.

- -

- Group 2: collects all contributions on utility companies and their corporate social responsibility (CSR).

3. Data Analysis and Results

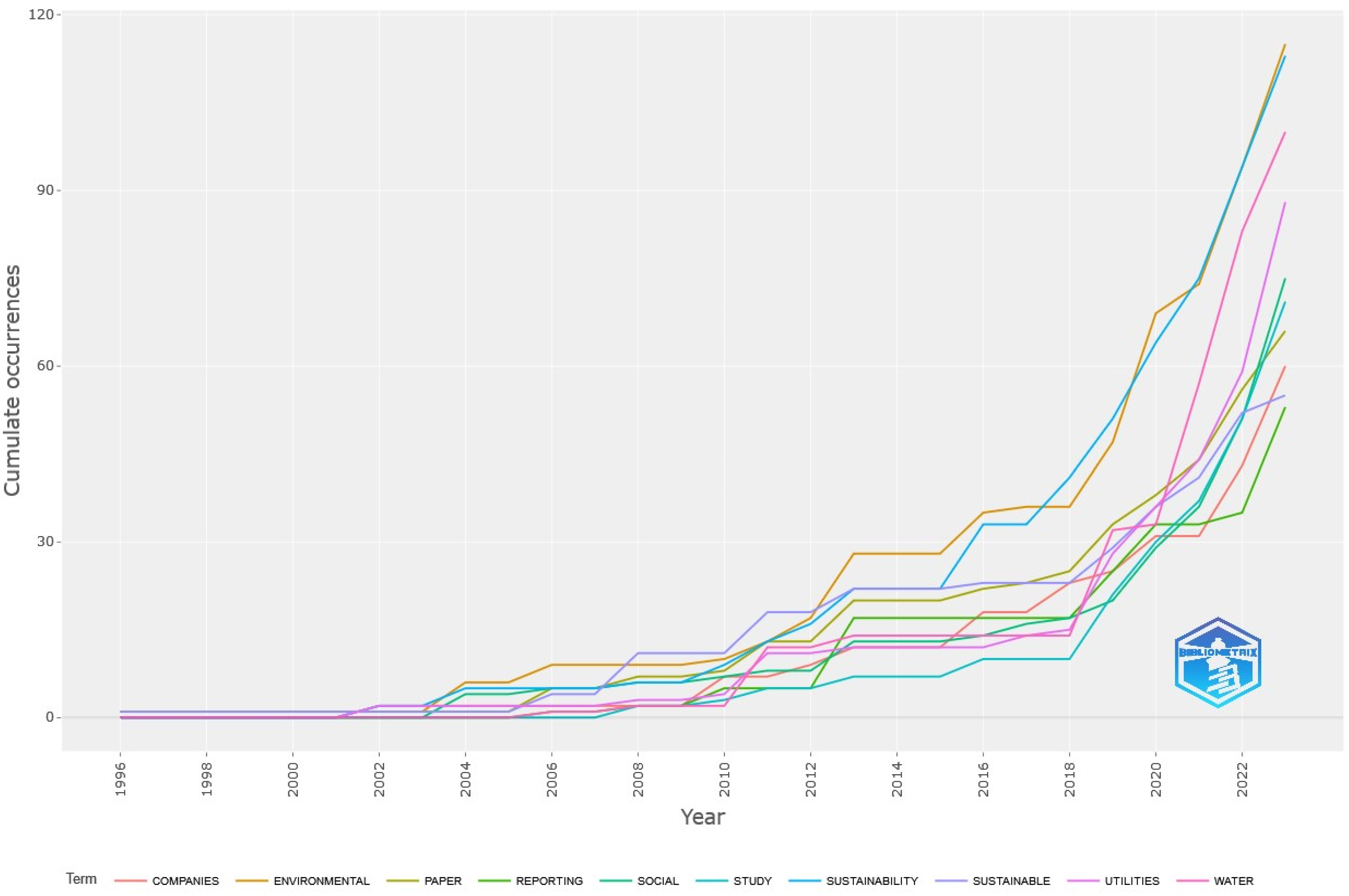

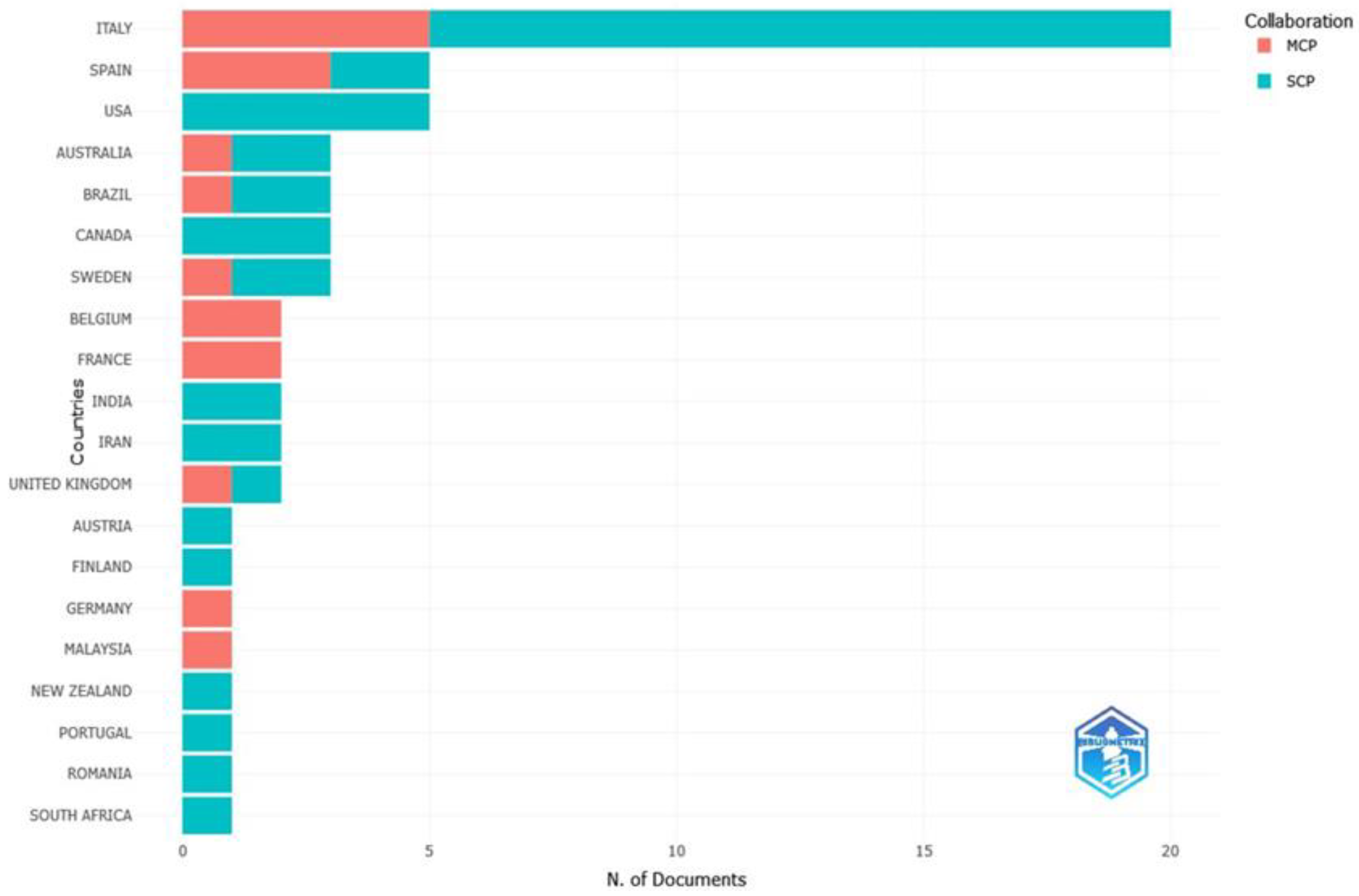

3.1. Bibliometric Aspects of the Selected Articles

3.2. Content of the Selected Articles

3.2.1. Sustainability Practice Disclosure

3.2.2. Sustainability Practices and Financial Issues

3.2.3. Practices for Sustainability: The Relevance of the Circular Economy

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions, Implications and Limitations

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- World Commission on Environment and Development, Special Working Session. World commission on environment and development. Our Common Future 1987, 17, 1–91. [Google Scholar]

- Bocken, N.M.; Geradts, T.H. Barriers and drivers to sustainable business model innovation: Organization design and dynamic capabilities. Long Range Plan. 2020, 53, 101950. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bauer, P.; Traxler, A.A.; Greiling, D. Management control by municipal utilities for value creation to achieve the sustainable development goals. Util. Policy 2023, 84, 101641. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Warner, M.E.; Bel, G. Competition or monopoly? Comparing privatization of local public services in the US and Spain. Public Adm. 2008, 86, 723–735. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garde Sanchez, R.; Rodriguez Bolivar, M.P.; Lopez Hernandez, A.M. Perceptions of stakeholder pressure for supply-chain social responsibility and information disclosure by state-owned enterprises. Int. J. Logist. Manag. 2017, 28, 1027–1053. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lepore, L.; Pisano, S. Environmental Disclosure: Critical Issues and New Trends; Taylor & Francis: Abingdon, UK, 2022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Manes-Rossi, F.; Nicolò, G.; Tiron Tudor, A.; Zanellato, G. Drivers of integrated reporting by state-owned enterprises in Europe: A longitudinal analysis. Meditari Account. Res. 2021, 29, 586–616. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nicolo, G.; Zampone, G.; Sannino, G.; Tiron-Tudor, A. Worldwide evidence of corporate governance influence on ESG disclosure in the utilities sector. Util. Policy 2023, 82, 101549. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cormier, D.; Gordon, I.M. An examination of social and environmental reporting strategies. Account. Audit. Account. J. 2001, 14, 587–617. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Di Vaio, A.; Trujillo, L.; D’Amore, G.; Palladino, R. Water governance models for meeting sustainable development Goals: A structured literature review. Util. Policy 2021, 72, 101255. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Massaro, M.; Dumay, J.; Guthrie, J. On the shoulders of giants: Undertaking a structured literature review in accounting. Account. Audit. Account. J. 2016, 29, 767–801. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tranfield, D.R.; Denyer, D.; Smart, P. Towards a methodology for developing evidence-informed management knowledge by means of systematic review. Br. J. Manag. 2003, 14, 207–222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Danese, P.; Manfe, V.; Romano, P. A systematic literature review on recent lean research: State-of-the-art and future directions. Int. J. Manag. Rev. 2018, 20, 579–605. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leonidou, E.; Christofi, M.; Vrontis, D.; Thrassou, A. An integrative framework of stakeholder engagement for innovation management and entrepreneurship development. J. Bus. Res. 2018, 119, 245–258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, C.L.; Chugh, H. Entrepreneurial learning: Past research and future challenges. Int. J. Manag. Rev. 2014, 16, 24–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dada, O. A model of entrepreneurial autonomy in franchised outlets: A systematic review of the empirical evidence. Int. J. Manag. Rev. 2018, 20, 206–226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elsevier. What Is Scopus about? 2022. Available online: https://service.elsevier.com/app/answers/detail/a_id/15100/supporthub/scopus/related/1/ (accessed on 4 April 2022).

- Fink, A. Conducting Research Literature Reviews: From the Internet to Paper, 5th ed.; Sage Publications: Los Angeles, CA, USA, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Krippendorff, K. Reliability in content analysis: Some common misconceptions and recommendations. Hum. Commun. Res. 2004, 30, 411–433. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aveyard, H. Doing a Literature Review in Health and Social Care: A Practical Guide; McGraw-Hill Education: London, UK, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Aria, M.; Cuccurullo, C. Bibliometrix: An R-tool for comprehensive science mapping analysis. J. Informetr. 2017, 11, 959–975. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heimerl, F.; Lohmann, S.; Lange, S.; Ertl, T. Word cloud explorer: Text analytics based on word clouds. In Proceedings of the 2014 47th Hawaii International Conference on System Sciences, Waikoloa, HI, USA, 6–9 January 2014; pp. 1833–1842. [Google Scholar]

- DiMaggio, P.; Powell, W.W. The iron cage revisited: Collective rationality and institutional isomorphism in organisational fields. Am. Sociol. Rev. 1983, 48, 147–160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carlisle, M.; Millar, M.I.; Jarosz Wukich, J. Shareholder primacy or stakeholder pluralism? Environmental shareholder proposals and board responses. Account. Audit. Account. J. 2023. Available online: https://www.emerald.com/insight/content/doi/10.1108/AAAJ-07-2021-5377/full/html (accessed on 29 October 2023).

- Hossain, M.M.; Alam, M.; Hecimovic, Á.; Alamgir Hossain, M.; Choudhury Lema, A. Contributing barriers to corporate social and environmental responsibility practices in a developing country: A stakeholder perspective. Sustain. Account. Manag. Policy J. 2016, 7, 319–346. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scarpellini, S.; Marín-Vinuesa, L.M.; Aranda-Usón, A.; Portillo-Tarragona, P. Dynamic capabilities and environmental accounting for the circular economy in businesses. Sustain. Account. Manag. Policy J. 2020, 11, 1129–1158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vitiea, K.; Lim, S. Voluntary environmental collaborations and corporate social responsibility in Siem Reap city, Cambodia. Sustain. Account. Manag. Policy J. 2019, 10, 451–475. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deegan, C.; Blomquist, C. Stakeholder influence on corporate reporting: An exploration of the interaction between WWF-Australia and the australian minerals industry. Account. Organ. Soc. 2006, 31, 343–372. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Y.L.; Huang, M.C. Water usage reduction and CSR committees: Taiwan evidence. Corp. Soc. Responsib. Environ. Manag. 2023, 30, 1070–1081. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ji, Y.; Ji, M.; Yang, G.; Dong, S. Water resource management and financial performance in high water-sensitive corporates. Corp. Soc. Responsib. Environ. Manag. 2023, 30, 2419–2434. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- D’Amore, G.; Landriani, L.; Lepore, L. Ownership and sustainability of Italian water utilities: The stakeholder role. Util. Policy 2021, 71, 101228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Suchman, M.C. Managing legitimacy: Strategic and institutional approaches. Acad. Manag. Rev. 1995, 20, 571–610. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bonetti, L.; Lai, A.; Stacchezzini, R. Stakeholder engagement in the public utility sector: Evidence from Italian ESG reports. Util. Policy 2023, 84, 101649. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Soares, R.A.; Abreu MC, S.D.; Rebouças SM, D.P.; Marino PD BL, P. The effect of national business systems on social and environmental disclosure: A comparison between Brazil and Canada. Rev. Bras. Gestão Negócios 2020, 22, 29–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moseñe, J.A.; Burritt, R.L.; Sanagustín, M.V.; Moneva, J.M.; Tingey-Holyoak, J. Environmental reporting in the Spanish wind energy sector: An institutional view. J. Clean. Prod. 2013, 40, 199–211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ligorio, L.; Caputo, F.; Venturelli, A. Sustainability disclosure and reporting by municipally owned water utilities. Util. Policy 2022, 77, 101382. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Russo, S.; Schimperna, F.; Lombardi, R.; Ruggiero, P. Sustainability performance and social media: An explorative analysis. Meditari Account. Res. 2022, 30, 1118–1140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Giacomini, D.; Zola, P.; Paredi, D.; Mazzoleni, M. Environmental disclosure and stakeholder engagement via social media: State of the art and potential in public utilities. Corp. Soc. Responsib. Environ. Manag. 2020, 27, 1552–1564. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mamun, M. Sustainability reporting of major electricity retailers in line with GRI: Australia evidence. J. Account. Organ. Chang. 2023, 19, 474–493. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Andrades, J.; Martinez-Martinez, D.; Herrera, J.; Larran, M. Is water management really transparent? A comparative analysis of ESG reporting of Andalusian publicly-owned enterprises. Public Money Manag. 2023, 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dragomir, V.D. The disclosure of industrial greenhouse gas emissions: A critical assessment of corporate sustainability reports. J. Clean. Prod. 2012, 29, 222–237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miras-Rodríguez MD, M.; Di Pietra, R. Corporate Governance mechanisms as drivers that enhance the credibility and usefulness of CSR disclosure. J. Manag. Gov. 2018, 22, 565–588. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ates, S. The credibility of corporate social responsibility reports: Evidence from the energy sector in emerging markets. Soc. Responsib. J. 2023, 19, 756–773. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mio, C. Corporate social reporting in Italian multi-utility companies: An empirical analysis. Corp. Soc. Responsib. Environ. Manag. 2010, 17, 247–271. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Frank, A.G.; Dalle Molle, N.; Gerstlberger, W.; Bernardi JA, B.; Pedrini, D.C. An integrative environmental performance index for benchmarking in oil and gas industry. J. Clean. Prod. 2016, 133, 1190–1203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Slacik, J.; Greiling, D. Coverage of G4-indicators in GRI-sustainability reports by electric utilities. J. Public Budg. Account. Financ. Manag. 2020, 32, 359–378. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Palme, U.; Tillman, A.M. Sustainable development indicators: How are they used in Swedish water utilities? J. Clean. Prod. 2008, 16, 1346–1357. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Traxler, A.A.; Greiling, D. Sustainable public value reporting of electric utilities. Balt. J. Manag. 2019, 14, 103–121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Imperiale, F.; Pizzi, S.; Lippolis, S. Sustainability reporting and ESG performance in the utilities sector. Util. Policy 2023, 80, 101468. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chelli, M.; Durocher, S.; Fortin, A. Substantive and symbolic strategies sustaining the environmentally friendly ideology: A media-sensitive analysis of the discourse of a leading French utility. Account. Audit. Account. J. 2019. Available online: https://www.emerald.com/insight/content/doi/10.1108/AAAJ-02-2018-3343/full/html (accessed on 29 October 2023). [CrossRef]

- Vinnari, E.; Laine, M. Just a passing fad? The diffusion and decline of environmental reporting in the Finnish water sector. Account. Audit. Account. J. 2013, 26, 1107–1134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tregidga, H.; Milne, M.J. From sustainable management to sustainable development: A longitudinal analysis of a leading New Zealand environmental reporter. Bus. Strategy Environ. 2006, 15, 219–241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Argento, D.; Culasso, F.; Truant, E. From sustainability to integrated reporting: The legitimizing role of the CSR manager. Organ. Environ. 2019, 32, 484–507. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Venturelli, A.; Ligorio, L.; de Nuccio, E. Biodiversity accountability in water utilities: A case study. Util. Policy 2023, 81, 101495. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paolone, F.; Sardi, A.; Sorano, E.; Ferraris, A. Integrated processing of sustainability accounting reports: A multi-utility company case study. Meditari Account. Res. 2021, 29, 985–1004. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lynn, K. A triple ‘S’for sustainability: Credit ratings agencies and their influence on the ecological modernization of an electricity utility. Util. Policy 2013, 27, 9–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Remo-Diez, N.; Mendaña-Cuervo, C.; Arenas-Parra, M. Exploring the asymmetric impact of sustainability reporting on financial performance in the utilities sector: A longitudinal comparative analysis. Util. Policy 2023, 84, 101650. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sidhoum, A.A.; Serra, T. Corporate social responsibility and dimensions of performance: An application to US electric utilities. Util. Policy 2017, 48, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rosenberg, S. PSEG and the promise of wind power. CASE J. 2019, 16, 51–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- López-Cabarcos, M.Á.; Santos-Rodrigues, H.; Quiñoá-Piñeiro, L.; Piñeiro-Chousa, J. How to explain stock returns of utility companies from an environmental, social and corporate governance perspective. Corp. Soc. Responsib. Environ. Manag. 2023, 30, 2278–2291. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mio, C.; Fasan, M.; Scarpa, F. Materiality investor perspectives on utilities’ ESG performance. An empirical analysis of ESG factors and cost of equity. Util. Policy 2023, 82, 101555. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hamrouni, A.; Uyar, A.; Boussaada, R. Are corporate social responsibility disclosures relevant for lenders? Empirical evidence from France. Manag. Decis. 2020, 58, 267–279. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Veltri, S.; Bruni, M.E.; Iazzolino, G.; Morea, D.; Baldissarro, G. Do ESG factors improve utilities corporate efficiency and reduce the risk perceived by credit lending institutions? An empirical analysis. Util. Policy 2023, 81, 101520. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peterson, T. Utility environmental commitments and shareholder performance. J. Sustain. Financ. Invest. 2022, 1–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Winkler, H.; Tyler, E.; Keen, S.; Marquard, A. Just transition transaction in South Africa: An innovative way to finance accelerated phase out of coal and fund social justice. J. Sustain. Financ. Invest. 2021, 13, 1228–1251. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wong FW, M.H.; Foley, A.; Del Rio, D.F.; Rooney, D.; Shariff, S.; Dolfi, A.; Srinivasan, G. Public perception of transitioning to a low-carbon nation: A Malaysian scenario. Clean Technol. Environ. Policy 2022, 24, 3077–3092. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Breindel, H. Right now. For tomorrow: Launching a purpose-driven sustainability brand. Brand. J. Brand Strategy 2021, 10, 121–126. [Google Scholar]

- Orsini, L.P.; Leardini, C.; Danesi, L.; Guerrini, A.; Frison, N. Circular economy in the water and wastewater sector: Tariff impact and financial performance of SMARTechs. Util. Policy 2023, 83, 101593. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- D’Inverno, G.; Carosi, L.; Romano, G. Environmental sustainability and service quality beyond economic and financial indicators: A performance evaluation of Italian water utilities. Socio-Econ. Plan. Sci. 2021, 75, 100852. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Annunziata, E.; Rizzi, F.; Frey, M. How do firms interpret extended responsibilities for a sustainable supply chain management of innovative technologies? An analysis of corporate sustainability reports in the energy sector. Sinergie Ital. J. Manag. 2019, 37, 57–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vernay, A.L.; Sohns, M.; Schleich, J.; Haggège, M. Commercializing sustainable technologies by developing attractive value propositions: The case of photovoltaic panels. Organ. Environ. 2020, 33, 220–244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lippolis, S.; Ruggieri, A.; Leopizzi, R. Open Innovation for sustainable transition: The case of Enel “Open Power”. Bus. Strategy Environ. 2023, 32, 4202–4216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schaefer, A. Corporate sustainability–integrating environmental and social concerns? Corp. Soc. Responsib. Environ. Manag. 2004, 11, 179–187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Minoja, M.; Romano, G. Managing intellectual capital for sustainability: Evidence from a Re-municipalized, publicly owned waste management firm. J. Clean. Prod. 2021, 279, 123213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Andrews, O.; Slater, A. Energy utilities tackle sustainability reporting. Corp. Environ. Strategy 2002, 9, 86–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beiranvand, D.N.; Firouzabadi, K.J.; Dorniani, S. A new framework for evaluation sustainable green service supply chain management in oil and gas industries. Teh. Glas. 2022, 16, 74–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cruz, S.; Paulino, S. Public service innovation and evaluation indicators. J. Technol. Manag. Innov. 2013, 8, 26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Noussan, M.; Tagliapietra, S. The effect of digitalization in the energy consumption of passenger transport: An analysis of future scenarios for Europe. J. Clean. Prod. 2020, 258, 120926. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leao, A.S.; Sipert, S.A.; Medeiros, D.L.; Cohim, E.B. Water footprint of drinking water: The consumptive and degradative use. J. Clean. Prod. 2022, 355, 131731. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gómez-Bolaños, E.; Hurtado-Torres, N.E.; Delgado-Márquez, B.L. Disentangling the influence of internationalization on sustainability development: Evidence from the energy sector. Bus. Strategy Environ. 2020, 29, 229–239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Basiri, S.K.; Sobhani, F.M.; Sadjadi, S.J. Developing natural-gas-supply security to mitigate distribution disruptions: A case study of the National Iranian Gas Company. J. Clean. Prod. 2020, 254, 120066. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Favre, M. Are Households Willing to Finance the Cost of Individual Water Supply? Case Study in Central Tunisia. Water Econ. Policy 2021, 7, 2150016. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lombardi, G.; Stefani, G.; Paci, A.; Becagli, C.; Miliacca, M.; Gastaldi, M.; Giannetti, B.; Almeida, C. The sustainability of the Italian water sector: An empirical analysis by DEA. J. Clean. Prod. 2019, 227, 1035–1043. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rafique, M.M.; Bahaidarah, H.M.; Anwar, M.K. Enabling private sector investment in off-grid electrification for cleaner production: Optimum designing and achievable rate of unit electricity. J. Clean. Prod. 2019, 206, 508–523. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Warneryd, M.; Karltorp, K. Microgrid communities: Disclosing the path to future system-active communities. Sustain. Futures 2022, 4, 100079. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amaral, A.L.; Martins, R.; Dias, L.C. Drivers of water utilities’ operational performance–An analysis from the Portuguese case. J. Clean. Prod. 2023, 389, 136004. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mergoni, A.; D’Inverno, G.; Carosi, L. A composite indicator for measuring the environmental performance of water, wastewater, and solid waste utilities. Util. Policy 2022, 74, 101285. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gonçalves, E.; Werneck Capodeferro, M.; Jerônimo Smiderle, J.; Engel Guimarães, P.H. Sustainability of water and sanitation state-owned companies in Brazil. Compet. Regul. Netw. Ind. 2022, 23, 101–118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, M.R.; Mittal, A.K.; Upadhyay, V. Benchmarking of North Indian urban water utilities. Benchmarking Int. J. 2011, 18, 86–106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Agovino, M.; Cerciello, M.; Garofalo, A.; Landriani, L.; Lepore, L. Corporate governance and sustainability in water utilities. The effects of decorporatisation in the city of Naples, Italy. Bus. Strategy Environ. 2021, 30, 874–890. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- George, R.A.; Siti-Nabiha, A.K.; Jalaludin, D.; Abdalla, Y.A. Barriers to and enablers of sustainability integration in the performance management systems of an oil and gas company. J. Clean. Prod. 2016, 136, 197–212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mehmood, A.; De Luca, F.; Quach, H. Investigating how board gender diversity affects environmental, social and governance performance: Evidence from the utilities sector. Util. Policy 2023, 83, 101588. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lamboglia, R.; Fiorentino, R.; Mancini, D.; Garzella, S. From a garbage crisis to sustainability strategies: The case study of Naples’ waste collection firm. J. Clean. Prod. 2018, 186, 726–735. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Soyka, P.A.; Bateman, M.E. Greenhouse Gas Management: Are US Public Utility Companies Ready? Electr. J. 2011, 24, 36–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Banerjee, S.B.; Bonnefous, A.M. Stakeholder management and sustainability strategies in the French nuclear industry. Bus. Strategy Environ. 2011, 20, 124–140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sudhir, V.; Muraleedharan, V.R.; Srinivasan, G. Integrated solid waste management in urban India: A critical operational research framework. Socio-Econ. Plan. Sci. 1996, 30, 163–181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Annesi, N.; Battaglia, M.; Frey, M. Stakeholder engagement by an Italian water utility company: Insight from participant observation of dialogism. Util. Policy 2021, 72, 101270. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matos, S.; Silvestre, B.S. Managing stakeholder relations when developing sustainable business models: The case of the Brazilian energy sector. J. Clean. Prod. 2013, 45, 61–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Searcy, C.; McCartney, D.; Karapetrovic, S. Identifying priorities for action in corporate sustainable development indicator programs. Bus. Strategy Environ. 2008, 17, 137–148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Giacomini, D.; Paredi, D.; Sancino, A. Stakeholder interactions as sources for organisational learning: Insights from the water sector. Meditari Account. Res. 2022, 30, 1–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bebbington, J.; Laine, M.; Larrinaga, C.; Michelon, G. Environmental accounting in the European Accounting Review: A reflection. Eur. Account. Rev. 2023, 32, 1107–1128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jebe, R. The convergence of financial and ESG materiality: Taking sustainability mainstream. Am. Bus. Law J. 2019, 56, 645–702. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Madison, N.; Schiehll, E. The effect of financial materiality on ESG performance assessment. Sustainability 2021, 13, 3652. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scheyvens, R.; Hughes, E.; Pratt, S.; Harrison, D. Tourism and CSR in the Pacific, in Tourism in Pacific Islands: Current Issues and Future Challenges; Pratt, S., Harrison, D., Eds.; Routledge: Evanston, IL, USA, 2015; pp. 134–147. [Google Scholar]

- Cantele, S.; Tsalis, T.A.; Nikolaou, I.E. A new framework for assessing the sustainability reporting disclosure of water utilities. Sustainability 2018, 10, 433. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Global Reporting Initiative and SASB. A Practical Guide to Sustainability Reporting Using Gri and Sasb Standards and Climateworks Foundation; Global Reporting Initiative and SASB: San Francisco, CA, USA, 2021; pp. 1–42. [Google Scholar]

- Shrivastava, P.; Verma, M.K.; Murmu, M.; Ahmad, I. Multi criteria decision analysis (MCDA) framework for the integrated urban water system. Int. J. Eng. Technol. 2018, 7, 290–293. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Truffer, B.; Voß, J.P.; Konrad, K. Mapping expectations for system transformations: Lessons from Sustainability Foresight in German utility sectors. Technol. Forecast. Soc. Chang. 2008, 75, 1360–1372. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhandari, P.; Creighton, D.; Gong, J.; Boyle, C.; Law, K.M. Evolution of cyber-physical-human water systems: Challenges and gaps. Technol. Forecast. Soc. Chang. 2023, 191, 122540. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bebbington, J.; Unerman, J. Achieving the United Nations Sustainable Development Goals: An enabling role for accounting research. Account. Audit. Account. J. 2018, 31, 2–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bebbington, J.; Larrinaga, C.; Moneva, J.M. Corporate social reporting and reputation risk management. Account. Audit. Account. J. 2008, 21, 337–361. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Unerman, J.; Bebbington, J.; O’dwyer, B. Corporate reporting and accounting for externalities. Account. Bus. Res. 2018, 48, 497–522. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cisco—Annual Report 2022. Reimagining the Future of Connectivity. Available online: https://www.cisco.com/c/dam/en_us/about/annual-report/cisco-annual-report-2022.pdf (accessed on 29 October 2023).

- Valenzuela-Fernandez, L.; Merigó, J.M.; Lichtenthal, J.D.; Nicolas, C. A bibliometric analysis of the first 25 years of the Journal of Business-to-Business Marketing. J. Bus.—Bus. Mark. 2019, 26, 75–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Sources | Articles |

|---|---|

| Journal of Cleaner Production | 14 |

| Utilities Policy | 14 |

| Business Strategy and the Environment | 6 |

| Corporate Social Responsibility and Environmental Management | 4 |

| Meditari Accountancy Research | 3 |

| Accounting Auditing and Accountability Journal | 2 |

| Journal of Sustainable Finance and Investment | 2 |

| Organization and Environment | 2 |

| Socio-Economic Planning Sciences | 2 |

| Technological Forecasting and Social Change | 2 |

| Baltic Journal of Management | 1 |

| Benchmarking | 1 |

| Case Journal | 1 |

| Clean Technologies and Environmental Policy | 1 |

| Competition and Regulation in Network Industries | 1 |

| Corporate Environmental Strategy | 1 |

| Electricity Journal | 1 |

| International Journal of Recent Technology and Engineering | 1 |

| Journal of Accounting and Organizational Change | 1 |

| Journal of Brand Strategy | 1 |

| Journal of Management and Governance | 1 |

| Journal of Public Budgeting Accounting and Financial Management | 1 |

| Journal of Technology Management and Innovation | 1 |

| Management Decision | 1 |

| Public Money and Management | 1 |

| Revista Brasileira de Gestao de Negocios | 1 |

| Sinergie | 1 |

| Social Responsibility Journal | 1 |

| Sustainable Futures | 1 |

| Tehnicki Glasnik | 1 |

| Water Economics and Policy | 1 |

| Total Papers | 72 |

| No. | Topic | Articles | Content |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Sustainability practice disclosure | Andrades et al., 2023; Argento et al., 2019; Ates, 2023; Chelli et al., 2018; Dragomir, 2012; Frank et al., 2016; Giacomini et al., 2020; Imperiale et al., 2023; Ligorio et al., 2022; Mamun, 2023; Mio, 2010; Miras-Rodriguez and Di Pietra, 2018; Mosene et al., 2012; Palme and Tillman, 2008; Paolone et al., 2021; Russo et al., 2022; Slacik and Greiling, 2020; Soares et al., 2020; Traxler and Greiling, 2019; Tregidga and Milne, 2006; Venturelli et al., 2023; Vinnari and Laine, 2013 [34,35,36,37,38,39,40,41,42,43,44,45,46,47,48,49,50,51,52,53,54,55] | Analysis of sustainability disclosure: determinants and quality |

| 2 | Sustainability practices and financial issues | Breindel, 2021; Hamrouni et al., 2020; Lopez-Cabarcos et al., 2023; Lynn, 2013; Mio et al., 2023; Peterson, 2022; Remo-Diez et al., 2023; Rosenberg, 2019; Sidhoum and Serra, 2017; Veltri et al., 2023; Winkler et al., 2023; Wong et al., 2022 [56,57,58,59,60,61,62,63,64,65,66,67] | Analysis of the relationships between sustainability practices and financial issues |

| 3 | Sustainability practices and circular economy | Annunziata et al., 2019; D’Inverno et al., 2021; Orsini et al., 2023; Lippolis et al., 2023; Schaefer, 2004; Vernay et al., 2020 [68,69,70,71,72,73] | Analysis of sustainability practices: circular economy and new technologies |

| 4 | Sustainability practices and their performance | Agovino et al., 2021; Amaral et al., 2023; Andrews and Slater, 2002; Basiri et al., 2020; Beiranvand et al., 2022; Cruz and Paulino, 2013; Favre, 2021; George et al., 2016; Gomez-Bolanos et al., 2019; Goncalves et al., 2022; Lamboglia et al., 2018; Lombardi et al., 2019; Mehmood et al., 2023; Leao et al., 2022; Mergoni et al., 2022; Minoja and Romano, 2021; Noussan and Tagliapietra, 2020; Rafique et al., 2019; Shrivastava et al., 2018; Singh et al., 2011; Soyka and Bateman, 2010; Warneryd and Karltorp, 2022 [74,75,76,77,78,79,80,81,82,83,84,85,86,87,88,89,90,91,92,93,94] | Analysis of the relationships between sustainability practices and their performance: different sustainability dimensions |

| 5 | Sustainability practices and stakeholders | Annesi et al., 2021; Banerjee and Bonnefous, 2011; D’Amore et al., 2021; Matos and Silvestre, 2013; Searcy et al., 2008; Sudhir et al., 1996 [31,95,96,97,98,99] | Analysis of the relationships between sustainability practices and stakeholders’ role |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

D’Amore, G.; Testa, M.; Lepore, L. How Is the Utilities Sector Contributing to Building a Sustainable Future? A Systematic Literature Review of Sustainability Practices. Sustainability 2024, 16, 374. https://doi.org/10.3390/su16010374

D’Amore G, Testa M, Lepore L. How Is the Utilities Sector Contributing to Building a Sustainable Future? A Systematic Literature Review of Sustainability Practices. Sustainability. 2024; 16(1):374. https://doi.org/10.3390/su16010374

Chicago/Turabian StyleD’Amore, Gabriella, Maria Testa, and Luigi Lepore. 2024. "How Is the Utilities Sector Contributing to Building a Sustainable Future? A Systematic Literature Review of Sustainability Practices" Sustainability 16, no. 1: 374. https://doi.org/10.3390/su16010374

APA StyleD’Amore, G., Testa, M., & Lepore, L. (2024). How Is the Utilities Sector Contributing to Building a Sustainable Future? A Systematic Literature Review of Sustainability Practices. Sustainability, 16(1), 374. https://doi.org/10.3390/su16010374