Abstract

This article explores the depopulation phenomenon in the context of the Molise region, an Inner Area in the south of Italy, considering it as an indicator of emerging social vulnerability. In particular, this paper presents the results of a quantitative study conducted in Molise on a non-probabilistic sample composed of 89 respondents through an online self-administered semi-structured questionnaire. This research may contribute to stimulating reflection on social vulnerability studies by explaining that, in the age of complexity, societies, although simple, are not builders of social capital capable of protecting against social vulnerability. In particular, the data reveal that more than 2/3 of the sample (+75%) do not participate in community activities (events at volunteer centers; civic and political activities; and events youth aggregation centers). For this reason, it is important to improve solidarity, which is the core of new strategies of proximity welfare that help to reduce depopulation.

1. Introduction

1.1. The Diversified Opportunities of Italian Society

In recent decades, growing territorial inequalities have promoted contrasting policies between different social realities, and, as a result, local welfare systems are becoming increasingly significant [1]. Within this framework, peripheral and vulnerable territories, especially in the south of Italy, suffer from a double disadvantage, both geographical and social, from which emerges the depopulation phenomenon [2].

Therefore, in order to reduce these gaps, local welfare tends to foster even more measures to support social services for people as well as ad hoc actions intended to increase job opportunities, especially for younger individuals because they, more than others, are leaving their native countries. In fact, according to the AlmaLaurea 2023 Report [3], a substantial percentage (28.6%) of young people—to attend university—migrate from southern to developed areas of central and northern Italy. This proportion of the population rarely returns to their “homeland”, where social relationships established among people, in the form of social capital [4,5,6], may allow them to live better [7], maintaining the bond between people and boosting solidarity among them [8]. The social bond—more than any other element—could become a protective factor enabling citizens to remain in a specific place, react to the risk of vulnerability, and compare possible critical events [9,10,11], both of a personal and socio-environmental nature, as reported in the literature.

This article, in relation to some dimensions of the Index of Social and Material Vulnerability, composed of seven different dimensions in addition to vulnerability (housing conditions, level of education, participation in the labor market, economic conditions, family structures, welfare distress, and ageing), considers the depopulation phenomenon in Molise.

Specifically, the total resident population of the Molisan area amounted to 289,840 on 1 January 2023 (Table 1), corresponding to a decrease of almost 4% in the last 12 months [12].

Table 1.

Resident population of the Molise Region for the years 2022–2023.

Moreover, between 1951 and 2019, a little village named “Provvidenti” in the Molise region experienced a strong contraction of its resident population, amounting to −83%. Other villages in this area are experiencing a similar decline, and the Regional County Seat (Campobasso) is also experiencing a decrease in population, especially with regard to younger residents (Figure 1). In fact, the number of young people aged 10 to 29 years old fell by 8283 persons over eight years (from 2011 to 2019) [13]. The depopulation phenomenon also impacts communities’ economic systems, livelihoods, and future development. Compared to the 2019 pre-crisis economic level, regional output in this area is still 1.5% lower than the national recovery rate and the output of southern regions in Italy [14].

Figure 1.

Administrative map of the Molise region.

It must be considered that the productive economic vocation of the Molise region is dedicated to agricultural, manufacturing, and handicraft activities [14] rather than being oriented toward innovative and attractive opportunities for youths.

In this scenario, the research critically analyses the behaviors of young people in the relationship between risk factors and possible (but not implemented) interventions for social change [15,16]. These factors govern the desire of a youth to stay or leave their own “community” [17,18,19], which is often determined by being born and raised in the “right” place (or not “right”) in the Italian peninsula.

In this study, we aim to investigate the future needs and expectations of young people (15–34 years old) in Molise in order to understand the kinds of interactions they have with the native territory, the reasons they give to explain the depopulation phenomenon, and the motivations that usually push them to leave (and sometimes return) to Molise.

Specifically, the research problem is articulated in the following cognitive questions:

- (1)

- In an age of complexity, are simple societies [20] builders of social capital?

- (2)

- Why do young people leave Molise?

- (3)

- Which strategies and actions should be adopted to limit social vulnerability in the future?

The research challenge is to find strategies [21] for providing proximity welfare, especially for communities located in regions dubbed “Inner” areas, known as fragile territories, far away from main centers and from essential services and all too often abandoned to themselves. These areas, constituting characteristic features throughout Europe, which in France are known as “forgotten territories” by the State and by the Market, in England as “territories left behind”, and in Spain as the “empty Spain” [22], all experience depopulation.

Moreover, all of Europe’s rural areas are also vulnerable to several issues: fewer job opportunities, weaker infrastructure, and poorer access to public services such as healthcare or education or commercial services such as entertainment. These elements, as also evidenced by the research conducted, precipitate new socio-demographic challenges for multilevel governance through a bottom-up approach, which can better address the needs of Inner Areas.

1.2. Conceptual Framework

In the literature, some researchers have considered social vulnerability to be a cause, and others an effect, of adversities [23]. Regardless, social vulnerability definitions are multiple. Among these, Cutter (1996) provided 18 different definitions [24] used across a variety of fields.

It is possible to define multiple indices of vulnerability, such as the Index of Vulnerability according to Territorial Fragility (IVFT), which measures the “health status of the territory” [25] (p. 60) according to the natural risk related to the characteristics of a territory, and the Index of Countering Social and Material Vulnerability (ICVSM), which covers social welfare assistance carried out by public bodies, particularly municipalities [25].

So, vulnerability is also considered a wider and multidimensional concept that may allow researchers to analyze how “the autonomy and self-determination capacity of individuals are permanently threatened by not being always involved in the main social integration and resource distribution systems” [26] (p. 8).

This concept is clearly related to the social analysis of deprivation, which is crucial to exploring well-being via a holistic approach [27].

This inevitably leads to considering social inequality a phenomenon rooted and reproduced in social systems resulting in trajectories of social vulnerability emphasizing the weaknesses typical of specific areas that are not able to address people’s needs.

Hence, the other side of social vulnerability can be termed “resilience” [28]. The latter is a risk adaptation tool useful for helping communities to recover from disturbances and improve their well-being [29,30,31]. In particular, Coles and Buckle (2004) state that for recovery processes, communities need the active and meaningful participation of people [32], without forgetting “the characteristics and circumstances of a community, system or asset that make it susceptible to the damaging effects of a hazard” [33] (p. 30).

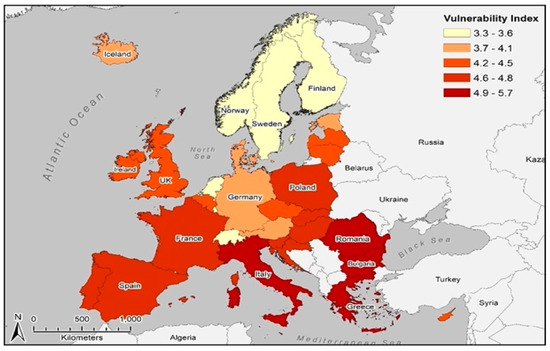

In this framework, Italy does not seem to be a very resilient country because, according to the European Commission, it has one of the highest vulnerability values in Europe (Figure 2), understood as “the risk of being affected by exogenous shocks, from various origins (external, natural, in particular climatic, or socio-political)” [34] (p. 14).

Figure 2.

Vulnerability index at the country level.

This definition is relevant because it refers to unknown future living conditions that are potential social risks and sources of need for different social groups, which have different abilities to react to and manage the effect of natural-hazard-related processes [35,36,37].

For example, younger generations, particularly inhabitants of Inner Areas of Italy, often live in conditions of great inequality that exposes them to the risk of social vulnerability [38,39].

So, on the one hand, the desire to leave their community [40,41,42] is growing among youths; on the other hand, the desire to deal with extreme adverse conditions is decreasing.

For this reason, social vulnerability—acting like a process for identifying and defining the potential, aspirations, and needs for the sustainable human development of a territory [43]—could contribute to identifying long-term policies in accordance not only with national, European, and extra-European strategies (e.g., National Strategy for Inner Areas; National Plan for Recovery and Resilience; Next generation EU; and Agenda 2030) but also bottom-up social policy.

This bottom-up approach considers a person not as a passive final subject of social benefits but as an active and emancipated subject that participates in the co-creation of well-being [7].

1.3. Welfare and Inner Areas

Over the years, the central role that civil society assumes has provided welfare because there has been an important change from a traditional welfare state to a welfare society [44]. In other words, the shift gave rise to so-called community welfare [45], also defined as proximity welfare [46]. In this type of welfare, the aim is to try to satisfy citizens’ needs through dedicated services (like social services) in order to benefit territories. Additionally, in this analysis, we report a worrying socio-demographic crisis above all for the Inner Areas of Italy, where there has been a “demographic decline” in the last 15 years, reaching a denatality rate of over 30% [12].

Among the factors precipitating this low birth rate, there is uncertainty about the future, which is especially burdensome for young people searching for a job. In fact, members of this social category struggle to enter to the labor market, pushing them further and further away from the possibility of gaining independence and having the time required to have their own families and children [47].

In addition, more than other territories, Inner Areas do not provide infrastructures such as adequate education facilities, mobility, care, assistance, and services for early childhood such as kindergartens. In fact, Inner communities “are aging”, and they will continue to suffer from the permanent tendency of the younger population to leave rural areas [48], provoking a further increase in vulnerability.

All of these aspects characterize the Molise region as an Inner Area and as a rural and peripheral territory, where 109 of 136 municipalities are defined by the Italian Territorial Cohesion Agency as being an “Inner” area, suffering from depopulation [49].

Moreover, this condition has been analyzed in many disciplinary studies concerning different European regions without taking into account the sociological perspective of vulnerability that could provide a key to the interpretation of inequalities of territories, useful for overcoming vulnerabilities.

For example, one can find studies on Inner Areas and the collection of good practices approached from the perspective of rural development [50], which is also crucial for understanding real communities’ needs, essential elements in the implementation of a sociological approach to creating new policies and increasing their resilience.

On this topic, discussed by the European Council and the Representatives of the Governments of the EU Member States, it has “become crucial to increase opportunities for young people in rural and remote areas also involving EU Member States, in order to promote and to facilitate the active citizenship and the meaningful participation of younger from diverse backgrounds” [51].

Participation in these processes should take place using appropriate approaches, such as the promotion of cooperation between administrations at all levels (horizontal and vertical principles subsidiarity), “including grassroots youth activities” [52].

1.4. Some Social Causes of Depopulation

In the interdisciplinary approach concerning the social vulnerability topic, the depopulation dimension, including demographic migration, is a multidimensional social event that can be analyzed at the macro level by analyzing institutional and political systems (from the perspective of global and local welfare) and at the micro level by observing individuals’ behaviors and motivations (voluntary or imposed), subtended by the decision to stay or leave a territory [53,54].

The causes that most frequently emerge are represented by Inner Areas’ inhabitants’ “not adequate” socio-economic conditions (related to employment opportunity issues) [55]. In addition, as the authors stressed in the cited paper, it is important to consider other problems: infrastructure insufficiency; the difficulty of creating networks between social, educational, cultural, and school services; climate change; the migration “emergency”; and the crisis regarding the traditional welfare system [56].

In particular, Inner Areas are losing territorial capital; historical–cultural heritage, both material (monuments, landscapes, etc.) and intangible (languages and dialects, traditional knowledge, etc.) [57]; and social and human capital.

In fact, these questions are highly significant for Inner Areas because they have to cope with demographic dynamics such as aging populations and low birth rates along with all the other crises connected to “new poverties” [2].

Historically, rural areas have been marked by constant processes of marginalization that have precipitated the isolation and impoverishment of their territories. These elements have negatively impacted these communities, which are becoming poorer and poorer, affecting their citizens’ identities [57].

Thus, the complex condition described herein requires a consideration of both the strengths and weaknesses of Inner Areas, also in terms of vulnerability risk, in order to evaluate public interventions [58] so as to include all institutional actors and Intermediate Bodies [59]. So, it is crucial to implement strategic actions useful for achieving a more sustainable and attractive form of the development of “edge” territories [60], a development model wherein values of social cohesion [20] are an authentic source for collective well-being.

In this way, these communities [61] could exert a healing effect that prevents many critical situations [62] in smaller territories; in fact, all the communities are “competent” [63] in re-designing the already-existing institutional patterns of intervention into resources of possible activation. Risk management (in its several manifestations: natural disasters, violence and crime, socio-cultural variables and political, economic, and geographical factors) is strategic with respect to the generation of responses that must be preventive and positive [46].

In this framework, social capital, intergeneration ties, solidarity [64], the sense of community [65], the value of belonging to a community [66], and involvement [67] are all factors that make a significant difference in the dynamics and processes of depopulation in Inner Areas, as well as the factors gathered from the Molise research.

For these reasons, institutions might reflect on themselves in terms of protective factors, risk factors in the local community, and finding a balance between the economic and social elements.

It is important to create a theoretical framework to assess and measure the multidimensional well-being of individuals and communities. It is also crucial to create a new collaboration of personal and collective well-being oriented towards an integrated approach. Moreover, it is necessary to change the actual economic paradigm, recognizing the limitations of economic indicators as a unique measurement of development, and to take into account climate change and ecological limits [68].

Indeed, the many and complex environmental and institutional challenges require a new direction, oriented toward promoting policies of sustainable development and its goals (the 17 Sustainable Development Goals of the United Nations), which, in turn, aim to encourage partnerships between public, public–private, and civil society actors.

All actors should work together on how communities can become places for satisfying the needs of future generations and on increasing the social and economic opportunities of women, men, and young people living in a given territory.

2. Research Methods

The authors conducted a literature review [5,6,60] regarding the main topic from a sociological integrated perspective, thanks to which the research problem and cognitive research questions were identified and outlined.

This research was implemented in Molise under the framework of a program financed by the Italian Ministry of Education, University, and Research, dubbed PCTO (Percorsi per le competenze trasversali e per l’orientamento), and was completed by 63 high school students, who also represent the convenience sample of this research. These students were instructed to enlarge the sample by encouraging their friends to join in on the research (snowball sample). Consequently, the final sample, not representative and not probabilistic, was composed of 89 young respondents aged between 16 and 32. Respondents were mostly young female students (78.7% versus 21.3% male): 71.8% of the sample was composed of 16–19-year-olds, 19.8% consisted of 20–24-year-olds, 5.2% consisted of 25–29-year-olds, and 3.2% consisted of 30–32-year-olds. Among these groups, 96.6% lived in Molise—mostly in the Inner Areas—with their families and were students (95.5%).

For the survey, conducted in March 2023, we opted for the self-administration of an online questionnaire for several reasons: web-based administration is quicker and more accessible, and data uploading and analysis are synchronized with compilation, and therefore the results are immediately available to researchers.

The semi-structured questionnaire was composed of closed questions and a few open-ended questions used to investigate subjective motivations [69]. It consisted of 66 questions; some questions included nominal variables, while others included ordinal variables assessed via the Likert Scale (from 1 to 5 points).

In the questionnaire, a funnel technique was employed, starting with simple questions regarding relationships with relatives and friends and ending with more complex questions related to the topic of depopulation. The questionnaire was divided into five different thematic areas: 1. socio-anagraphical; 2. perception of one’s relationship with one’s family, friendships, territory, and well-being/quality of life; 3. perception of and motivation for depopulation; 4. behaviors exhibited; and 5. the role of policies and welfare in countering this phenomenon.

All these dimensions are related to social vulnerability, well-being, and depopulation in Inner Areas, providing useful information for exploring topics through descriptive and relationship-related research questions.

It was necessary to use a qualitative perspective to observe phenomena analyzed from different points of view in order to verify the possible convergence of results, which will be used to validate them (triangulation) [70].

3. Results

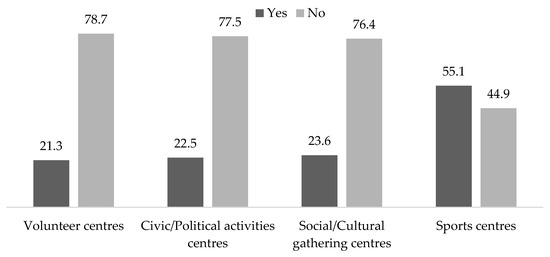

Many of the young people interviewed reported that they were not fully active in the territorial communities in which they lived (Figure 3); in fact, very few of them were involved in volunteer centers (21.3%). Similarly, 22.5% participated in civic and political activities, and 23.6% attended socio-cultural centers, while more than half of the sample (55.1%) reported involvement in sports centers.

Figure 3.

Social participation in community activities (%).

Moreover, confirming this hypothesis, 33.7% of the respondents argued that the territories where they live do not promote community well-being, reporting a lack of major health services, sports facilities, cultural and social associations (61.8% each), schools (60.7%), transport infrastructures (55.1%), banks and post offices (32.6%), universities (28.1%), and training centers (25.8%).

More than half of the young respondents (53.9%) declared that they engage in daily travel to reach school or university (76.4%); go shopping (74.2%); receive medical treatment and undergo specialized examinations (58.4%); visit the cinema, theatre, or museum (47.2%); and even meet friends (51.7%).

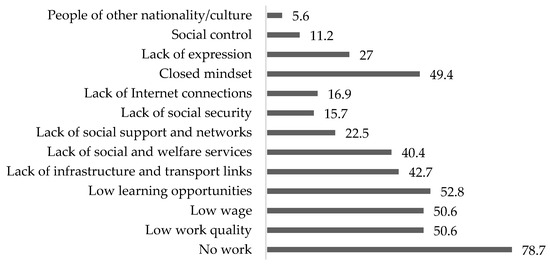

In addition, the respondents highlighted all social vulnerability index dimensions. In fact, they mentioned an “absence” of jobs (78.7%), few educational opportunities (52.8%), humble salaries (50.6%), a lack of infrastructure and connections (42.7%), and inefficient social and welfare services (40.4%), representing the main reasons contributing to Molise’s depopulation (Figure 4).

Figure 4.

Reasons for depopulation in the territory (%).

Accordingly, more than 43.8% of the sample said that they would leave Molise because “there are very few opportunities for personal and economic growth” and, therefore, “there is no life choices” because institutions and political bodies fail to respond to the needs of young people who decide to stay in this geographic area (53.9%).

The young people interviewed said they wished to leave Molise (41.6%) because they wanted to “find more opportunities” and “have better life chances” and “better life expectancy”.

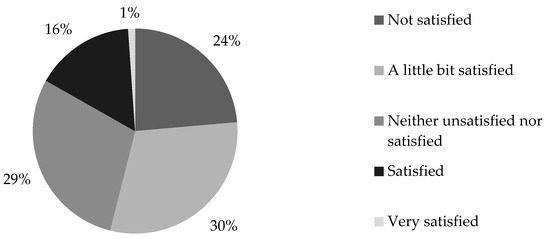

Indeed, a factor emphasizing this community’s “alienation” is the sense of life dissatisfaction in the community; almost half of the sample (54,9%) said that they were not satisfied, while 16.8% claimed that they were satisfied, and the rest of the youths claimed that they had neutral perspectives about their lives.

In any case, the only positive but not attractive element in simple society is represented by family life and friendship ties, which are fundamental for the respondents’ well-being (80%) [71] (Figure 5).

Figure 5.

Degree of life satisfaction in the territory (%).

An interesting finding—which is connected to the theme of Should Young stay or should Young go—is linked to the social-cultural patterns: most of the sample (98.9%) believed that they lived in a small town where “there are only old people who judges behavior with prejudice” [72] and where “people are not open to each other”.

According to the respondents, the main actors responsible for depopulation are the government (61.8%), local authorities (62.9%), and the consequently inadequate welfare policies (47.2%).

However, the respondents indicated some possible solutions that might combat the phenomenon of depopulation, such as natural and cultural resources (68.5%), specific productive activities (52.8%), proximity services for the population (48.3%), the creation of new services (41.6%), and opportunities for supporting young people that encourage them to “stay and don’t go”.

Political bodies should encourage the access of young people to the workplace (89.9%); create many more educational opportunities in accordance with the excellence present in this territorial area (73.0%); arrange connections and infrastructures (49.4%); create and modify work orientation from school (44.9%); and reinforce social welfare services (43.8%).

In fact, schools and universities play a crucial role in creating work-oriented possibilities in the territory (68.5%), ideating more efficient school-to-work alternation agreements (61.8%), strengthening the internship activities in degree programs (51.7%), and creating cooperation networks with other universities and nearby areas (42.7%).

There are other motivations explaining the choice to leave Molise among youths, but it is important to stress the National Strategy of Inner Areas and the new National Recovery and Resilience Plan that can represent a real challenge regarding fostering better life chances for all members of younger generations living in the Inner Areas of Italy.

4. Discussion

This article is based on the conceptual framework of social and material vulnerability defined by scholars [26] as people’s exposure to the risk of not being permanently included in the main systems of social integration and the distribution of resources.

Adhering to this definition, several countries have promoted vulnerability analyses and produced some reports. Among these, at the international level, it is important to refer to the United Nations’ Human Development Report—Sustaining Human Progress: Reducing Vulnerabilities and Building Resilience; meanwhile, at the national level, ad hoc statistical surveys [25] have been conducted specifically for regional territories.

These surveys have allowed the creation of a territorial database, relevant for scientific studies (8MILACENSUS), in which social and material vulnerability are presented along with seven other thematic areas (population, integration of foreigners, families, housing conditions, education, the labor market, and mobility in an area).

This tool enabled the creation of a profile of Italian territorial communities useful for helping decision makers to plan social policies at the local and national levels.

Within this framework, studies conducted on specific territories are important because they enrich specific context knowledge. For this reason, this study, conducted in Molise, an Inner Italian Area, considered the definition of vulnerability in terms of the lack of social integration for a specific social category, namely, young people, who, feeling excluded from their communities and revealing a negative outlook about the future, may decide to leave. The research’s data represent young people’s lack of involvement and participation in their communities and their social inclusion activities and indicate their wish to remain outsiders, with the desire to abstain from engagement with the changing conditions of the territories they live in. So, simple societies [20] are not always promoters of social solidarity and, consequentially, may not be builders of social consensus and social capital. In this social structure, young people do not have the perception of being similar and do not collaborate for consensus building.

Inner communities, characterized by the quasi-exclusive presence of elderly people (98.9% of the sample affirmed that “there are only old people who judges behavior with prejudice”), induce distrust in young people towards both the communities themselves and old people, depicted according to the image proposed by Goodman [73] “as a seemingly closed room” where young people do not enter.

Thus, a further element of territorial fragility, i.e., depopulation, emerges.

All Inner Areas’ critical elements also enable young people to transform their biographical pathways. For example, the respondents highlighted the lack of job opportunities (89.9%) as an element motivating their migration [74].

Nowadays, the challenges facing Inner Areas and the younger generations living there are many and reflect multiple factors, as demonstrated by the research discussed here.

Hence, in the territory analysis, the community emerges as a broader sociological category that is inclusive of complex social action; it is social identity and belonging to a group that can (re)generate solidarity as “a set of subjects who share significant aspects of their existence and who, because of this, are in a relationship of interdependence, can develop a sense of belonging and can entertain relations of mutual trust” [75] (p. 13). Feeling a sense of “community” [76] implies being active citizens with rights and duties; social participation must be placed at the center of policies and welfare, where fragmented interventions can no longer be imagined.

It is important to consider active participation in the “community” through political, socio-cultural, and voluntary actions. Indeed, “the social value and function of voluntary activity is an expression of participation, solidarity and pluralism, promotes its development while safeguarding its autonomy and encourages its original contribution to the achievement of social, civil and cultural goals” [77].

The possibility of being actors in processes of change relates to the possibility of knowing a territory and influencing it at the political level in order to be able to imagine positive strategies for citizens from a horizontal welfare level. Sharing and cultivating common values in proximity, thanks to the collective consciousness, i.e., “the set of beliefs and feelings common […] to the members of the same society” [20] (p. 46), means making a community more competent and “resilient” in different aspects [78].

This means creating better bonds for social cohesion, solidarity, and reducing social, cultural, and economic inequalities [79]. Unfortunately, from what has emerged, solidarity is in danger because there appear to be no opportunities to change communities in the future.

In this regard, a high dissatisfaction rate (53.9%) of quality of life emerges. Research findings, although derived from a small sample size that does not allow for generalization, suggest the implementation of policies that, acting through the welfare system, work toward this direction, prioritizing the satisfaction of the younger generation as an indicator, among others, of holistic well-being. Not surprisingly, employment status may contribute to well-being along with a “good” health status and economic support. In fact, the respondents proposed proactive actions that, being varied and multilevel, could offer proximity welfare for territories, reconciling this form of welfare with the universalism of rights.

If politicians do not and will not invest in measures in order to increase the rate of births, promote labor market participation, and encourage the (re)organization and management of migration flows, then “the region’s economic-social growth will suffer a strong and further decline” [14] (p. 22).

At the same level, the inadequacy of infrastructure connections makes community empowerment very difficult; for reference, consider the data related to the daily commutes for basic and necessary needs for the young people interviewed. In this sense, the scarce presence of social welfare services and social support should be emphasized. This makes it difficult to appropriately address citizens’ needs, especially in the changed epidemiological and demographic scenario.

There is also a gap in the educational and training services that are available to the sample, which were perceived to be insufficient and inadequate. In this regard, the educational poverty issue, specifically in Molise, should be highlighted [80]: kindergartens and early-childhood services in this region offer 1.224 facilities compared to about 6.000 for children under the age of 3; the supply of these services in Molise is 44.1% compared to the national average of 59.3% [81]. Such limited access to these services can easily lead to social isolation, which is one of the push factors causing young people to migrate to other (more developed) areas.

Consequently, the data collected will form the basis for developing future studies, and in this frame more attention should be paid to the protective resilience factors (social, cultural, economic, and political) that make it possible to respond adequately to the needs of the local population, thinking in terms of preventing social vulnerability, promoting culture, and strengthening social welfare services.

The National Strategy for Inner Areas (SNAI), for example, includes (among others) these areas of intervention (essential services and local development) and, at the regional level, is in line with other policy instruments, such as the National Recovery and Resilience Plan (PNRR) and the 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development. In this framework, the challenge for the future is to implement proximity welfare appropriately supported by the economic resources belonging to the National Recovery and Resilience Plan (PNRR), which can act as a flywheel to counter the depopulation of the Inner Areas of Italy induced by the younger generations, and by the achievement of the 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development goals to reduce vulnerability and all kinds of inequalities.

As Johan Rockström reminds us, the global economic system must be fundamentally rethought by (re)connecting it to the biosphere and the resources provided by the Earth [82]. A new form of integrated, proactive, and collaborative governance that must work on equity and on inclusion is required; in this way, it is possible to respond to the ever-increasing risks and different vulnerabilities.

Actors at the political and administrative levels have to think about a real proximity welfare scheme to enforce actions that improve and emancipate their communities through the implementation of the interventions provided in the plans. At the same time, it is therefore essential to structurally invest in economic policies, particularly in labor and family policies; in health and welfare policies; and in the geography of the regional territory. Otherwise, the risk that is more than just real is that of undermining community resilience and future sustainability.

In conclusion, these results could create a good basis for further studies involving other similar socio-geographical contexts, despite the fact that this study possesses some significant limitations, i.e., the small sample size that is justified by this specific kind of research, namely the pilot study.

Addressing the areas outlined above would allow for a comparison of different units of analysis, useful for the conception of a welfare model that succeeds, via its policies, in reducing the Inner Area depopulation phenomenon and the migration of young people. This phenomenon seems to have the same push factors everywhere.

For this purpose, it could be interesting to compare the group of young Inner Area migrants with that of young foreign migrants in order to highlight similarities and differences in the push factors of different migrations.

A comparison is fundamental to identifying common strengths and weaknesses and then analyzing the most significant results in depth, assuming a transformative paradigm capable of transforming and emancipating research contexts.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, D.G.; methodology, D.G. and D.B.; validation, D.G., M.D. and D.B.; formal analysis, D.B.; investigation, D.G. and M.D.; data curation, D.G., M.D. and D.B.; writing—original draft preparation, D.G. and M.D.; writing—review and editing, D.G., M.D. and D.B.; visualization, M.D.; supervision, D.G., M.D. and D.B. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study. The research was conducted with full respect for the participants and research partners. The data were anonymized so that they could not be linked to the respondents of the survey.

Data Availability Statement

The data presented in this study are available on request from the corresponding author. The data are not publicly available.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Cibinel, E.; Maino, F. Valoriamo: Reti partecipate per un welfare aziendale a misura di territorio. In Il Ritorno Dello Stato Sociale? Mercato, Terzo Settore e Comunità oltre la Pandemia. Quinto Rapporto sul Secondo Welfare in Italia 2021; Maino, F., Ed.; Giappichelli: Torino, Italy, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Reynaud, C.; Miccoli, S. Demographic sustainability in Italian territories: The link between depopulation and population ageing. Vienna Yearb. Popul. Res. 2023, 21, 339–360. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Almalaurea. Mobilità per Studio e Lavoro. 2023. Available online: https://www.almalaurea.it/sites/default/files/2023-06/4_Approfondimento_mobilit%C3%A0_per%20studio%20e%20lavoro_0.pdf (accessed on 11 December 2023).

- Bourdieu, P. Le Sens Pratique; Minuit: Paris, France, 1980. [Google Scholar]

- Putnam, R.D. Bowling Alone: America’s Declining Social Capital. In Culture and Politics. A Reader; Crothers, L., Lockhart, C., Eds.; Palgrave Macmillan: London, UK, 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Coleman, J. Foundations of Social Theory; Harvard University Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 1990. [Google Scholar]

- Grignoli, D. Welfare percorsi di innovazione. In Welfare Rights e Community Care. Rischi e opportunità del Vivere Sociale; Barba, D., Grignoli, D., Eds.; Edizioni Scientifiche Italiane: Napoli, Italy, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Breton, M. Neighborhood resiliency. J. Community Pract. 2001, 19, 21–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gist, R.; Lubin, B. Psychosocial Aspects of Disasters; Wiley: Toronto, ON, Canada, 1989. [Google Scholar]

- Kendra, J.; Wachtendorf, T. Elements of resilience after the World Trade Center disaster: Reconstituting New York City’s Emergency Operations Centre. Disasters 2003, 27, 37–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pierucci, P.; Serio, M. Modalità di coping di fronte alla pandemia. Sociologia dei disastri e resilienza di comunità. Salute Società 2021, 3, 191–215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Istat. Indicatori Demografici; Istituto Nazionale di Statistica: Roma, Italy, 2022; Available online: https://demo.istat.it/tavole/?t=indicatori (accessed on 10 December 2023).

- Istat. Il Censimento Permanente Della Popolazione in Molise; Istituto Nazionale di Statistica: Roma, Italy, 2021; Available online: https://www.istat.it/it/files//2021/02/Censimento-permanente-della-popolazione_Molise.pdf (accessed on 12 December 2023).

- Bank of Italy. Regional Economies. The Economy of Molise; Banca d’Italia: Roma, Italy, 2023; Available online: https://www.bancaditalia.it/pubblicazioni/economie-regionali/2023/2023-0014/2314-molise.pdf (accessed on 12 December 2023).

- Blaikie, P.; Cannon, T.; Davis, I.; Wisner, B. At Risk. Natural Hazards, People’s Vulnerability and Disasters; Routledge: London, UK, 1994. [Google Scholar]

- AHPRU. A Study of Resiliency in Communities; Health Canada: Ottawa, ON, Canada, 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Bauman, Z. Missing Community; Harvard University Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Tönnies, F. Gemeinschaft und Gesellschaft; Fues: Leipzig, Germany, 1887. [Google Scholar]

- Simmel, G. Die Großstädte und das Geistesleben; Hofenberg: Petershagen, Germany, 1903. [Google Scholar]

- Durkheim, E. De la Division du Travail Social; Alcan: Paris, France, 1893. [Google Scholar]

- Malaguti, E. Educarsi Alla Resilienza. Come Affrontare Crisi e Difficoltà e Migliorarsi; Erickson: Trento, Italy, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Pugliese, E. In Spopolamento, Stipendi Bassi e Pochi Servizi. L’Emigrazione in Italia Diventa un Problema anche Ambientale D’Alessandro J. Repubblica. 2023. Available online: https://www.repubblica.it/green-and-blue/2023/02/16/news/spopolamento_stipendi_bassi_servizi_ambiente_aree_interne_borghi_pnrr-388142884/ (accessed on 5 December 2023).

- Kates, R.W. The interaction of climate and society. In Climate Impact Assessment; Kates, R.W., Ausubel, J.H., Berberian, M., Eds.; Wiley: New York, NY, USA, 1985. [Google Scholar]

- Cutter, S.L. Vulnerability to environmental hazards. Prog. Hum. Geogr. 1996, 20, 529–539. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Istat. Le Misure Della Vulnerabilità; Istituto Nazionale di Statistica: Roma, Italy, 2020; Available online: https://www.istat.it/it/files/2020/12/Le-misure-della-vulnerabilita.pdf (accessed on 12 December 2023).

- Ranci, C. Fenomenologia della vulnerabilità sociale. Rass. Ital. Di Sociol. 2002, 43, 521–552. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Townsend, P. Deprivation. J. Soc. Policy 1987, 16, 125–146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Galderisi, A.; Ferrara, F.; Ceudech, A. Resilience and/or vulnerability? Relationships and roles in risk mitigation strategies. In Proceedings of the 24th AESOP Annual Conference, Helsinki, Finland, 7–10 July 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Glass, R.I.; Craven, R.B.; Bregman, D.I.; Stroll, B.J.; Kerndt Horowitz, P.; Winkle, J. Injuries from Wichita Falls tornado: Implications for prevention. Science 1980, 207, 734–738. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bolin, R. Long-Term Recovery from Disaster; Institute of Behavioral Science: Boulder, CO, USA, 1982. [Google Scholar]

- Perry, J.B.; Hawkiils, R.; Neal, D.M. Giving and Receiving Aid. IJMED 1983, 1, 171–188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coles, E.; Buckle, P. Developing Community Resilience as a Foundation for Effective Disaster Recovery. AJEM 2004, 19, 6–15. [Google Scholar]

- United Nations Office for Disaster Risk Reduction. UNISDR Terminology on Disaster Risk Reduction; United Nations: Geneva, Switzerland, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- United Nations. Multidimensional Vulnerability Index. Potential Development and Uses; United Nations: Geneva, Switzerland, 2021; Available online: https://sdgs.un.org/sites/default/files/2021-11/multidimensional_vulnerability_indices_0.pdf (accessed on 14 December 2023).

- Oliver-Smith, A. What Is a Disaster? Anthropological Perspectives on a Persistent Question; Routledge: New York, NY, USA, 1999. [Google Scholar]

- Weichselgartner, J. Disaster mitigation: The concept of vulnerability revisited. DPM 2001, 10, 85–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cutter, S.L.; Boruff, B.J.; Shirley, W.L. Social vulnerability to environmental hazards. Soc. Sci. Q. 2003, 84, 242–261. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Istat. Le Misure della Vulnerabilità: Un’applicazione a Diversi Ambiti Territoriali; Istituto Nazionale di Statistica: Roma, Italy, 2020; Available online: https://www.istat.it/it/files/2020/12/Le-misure-della-vulnerabilita.pdf (accessed on 12 December 2023).

- Istat. I giovani Del Mezzogiorno: L’incerta Transizione All’età Adulta; Istituto Nazionale di Statistica: Roma, Italy, 2023; Available online: https://www.istat.it/it/files//2023/10/Focus-I-giovani-del-mezzogiorno.pdf (accessed on 12 December 2023).

- Wirth, L. The City; University of Chicago Press: Chicago, IL, USA, 1925. [Google Scholar]

- Park, R.E. Human Communities: The City and Human Ecology; Free Press: Glencoe, IL, USA, 1952. [Google Scholar]

- Park, R.E. The city: Suggestions for the investigation of human behavior in the urban environment. In The City; Park, R.E., Burgess, E.W., McKenzie, R.D., Eds.; University of Chicago Press: Chicago, IL, USA, 1967. [Google Scholar]

- Godfrey, B. Toward the construction of a social vulnerability index—Theoretical and methodological considerations. Soc. Econ. Stud. 2004, 53, 1–29. [Google Scholar]

- Ferrera, M. Modelli di Solidarietà. Politica e Riforme Sociali Nelle Democrazie; Il Mulino: Bologna, Italia, 1993. [Google Scholar]

- Cugno, A. Il potere istituente del welfare comunitario: Considerazioni a margine. In Welfare Responsabile; Cesareo, V., Ed.; Vita e Pensiero: Milano, Italy, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Messia, F.; Venturelli, C. Il Welfare di Prossimità: Partecipazione Attiva, Inclusione Sociale e Comunità; Erickson: Trento, Italy, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Inapp. Una Ripresa a Tempo Parziale; Istituto Nazionale per le Analisi Delle Politiche Pubbliche: Roma, Italy, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Mijarc. The Future of Rural Youth. 2003. Available online: https://www.saltoyouth.net/downloads/4-17-1251/FutureOfRuralYouth_MIJARC.pdf (accessed on 18 December 2023).

- Agenzia Per La Coesione Territoriale. Strategy. Roma. 2020. Available online: https://www.agenziacoesione.gov.it/lagenzia/obiettivi-e-finalita/strategia/?lang=en (accessed on 15 December 2023).

- Labianca, M.; Navarro Valverde, F. Depopulation and aging in rural areas in the European Union: Practices starting from the LEADER approach. In Perspectives on Rural Development; Cejudo, E., Navarro, F., Eds.; Siba Unisalento: Lecce, Italy, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Council of the European Union. Raising Opportunities for Young People in Rural and Remote Areas. 2020. Available online: https://www.consilium.europa.eu/media/44119/st08265-en20.pdf (accessed on 14 December 2023).

- European Union. Official Journal of the European Union. 2020. Available online: https://eur-lex.europa.eu/legal-content/EN/TXT/PDF/?uri=OJ:C:2020:193:FULL&from=EN (accessed on 14 December 2023).

- Giardiello, M.; Capobianco, R. Le contraddizioni e i paradossi della mobilità giovanile italiana. Studi Di Sociol. 2021, 1, 83–100. [Google Scholar]

- Giardiello, M.; Capobianco, R. Può la mobilità determinare un cambiamento sociale? Il caso studio dei giovani calabresi. Meridiana: Riv. Di Stor. E Sci. Soc. 2022, 103, 205–230. [Google Scholar]

- Avallone, G. La Sociologia Urbana e Rurale. Origini e Sviluppi in Italia; Liguori Editore: Napoli, Italy, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Carrosio, G. I margini al Centro. L’Italia Delle Aree Interne Tra Fragilità e Innovazione; Donzelli: Roma, Italy, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Amodio, T. Una lettura della marginalità attraverso lo spopolamento e l’abbandono nei piccoli comuni. Boll. Della Assoc. Ital. Cartogr. 2021, 172, 50–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- D’Arcangelo, L. Welfare di comunità e inclusione sociale. Riv. Del Dirit. Della Sicur. Soc. 2015, 15, 25–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Agenzia Per La Coesione Territoriale. Intermediate Bodies. Roma. 2020. Available online: https://www.agenziacoesione.gov.it/lacoesione/le-politiche-di-coesione-in-italia-2014-2020/the-actors/intermediate-bodies/?lang=en (accessed on 15 December 2023).

- Barca, F.; Casavola, P.; Lucatelli, S. Strategia Nazionale per le AREE Interne: Definizione, Obiettivi, Strumenti e Governance; Collana Materiali UVAL: Roma, Italy, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Neal, Z. Making Big communities small: Using network science to understand the ecological and behavioral requirements for community social capital. Am. J. Community Psychol. 2015, 55, 369–380. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tobin, G.A.; Whiteford, L.M. Economic Ramifications of Disaster: Experiences of Displaced Persons on the Slopes of Mount Tungurahua, Ecuador. In Proceedings of the Applied Geography Conferences 25, Binghamton, NY, USA, 23–25 October 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Lavanco, G.; Novara, C. Disastri, Catastrofi ed Emergenze: Analisi dei Maggiori Contributi in Psicologia dei Disastri. In Comunità e globalizzazione della paura; Lavanco, G., Ed.; FrancoAngeli: Milano, Italy, 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Hernandez, P. Resilience in families and communities: Latin American contributions from the psychology of liberation. Fam. J. Couns. Ther. Couples Fam. 2002, 1, 334–343. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sarason, S.B. The Psychological Sense of Community: Prospects for a Community Psychology; Brookline Books: Brookline, MA, USA, 1974. [Google Scholar]

- Mahmoudi Farahani, L. The value of the sense of community and neighbouring. Hous. Theory Soc. 2016, 33, 357–376. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zimmerman, M.A. Empowerment Theory & Adolescent Resilience. In Proceedings of the European Association for Research on Adolescence, Cyprus, 25–28 September 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Stiglitz, J.; Sen, A.; Fitoussi, J.-P. The Measurement of Economic Performance and Social Progress Revisited (Reflections and Overview); Commission on the Measurement of Economic Performance and Social Progress: Paris, France, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Corbetta, P. Metodologia e Tecniche Della Ricerca Sociale; Il Mulino: Bologna, Italy, 1999. [Google Scholar]

- Cameron, R. Mixed Methods Research: The Five Ps Framework. EJBRM 2011, 9, 96–108. [Google Scholar]

- Banfield, E.C. The Moral Basis of a Backward Society; Free Press: Glencoe, IL, USA, 1958. [Google Scholar]

- Secondulfo, D. La Bella Età. Giovani e Valori Nel Nord-Est di Un’italia che Cambia; FrancoAngeli: Milano, Italy, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Goodman, P. La Gioventù Assurda. Problemi dei Giovani Nel Sistema Organizzato; Einaudi: Torino, Italy, 1964. [Google Scholar]

- Barbieri, P.; Cutuli, G.; Scherer, S. Giovani e lavoro oggi. Uno sguardo sociologico a una situazione a rischio. Sociol. Del Lav. 2014, 136, 73–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martini, E.R.; Torti, A. Fare Lavoro di Comunità; Carocci: Roma, Italy, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Chavis, D.M.; Wandersman, A. Sense of community in the urban environment: A catalyst for participation and community development. In A Quarter Century of Community Psychologyl; Springer: Boston, MA, USA, 2002; pp. 265–292. [Google Scholar]

- Framework Law on Volunteering; Law August 11, 1991, No. 266—Art. 1, Paragraph 1; GU Serie Generale n. 196: Rome, Italy, 1991.

- Bravo, M.; Rubio-Stipec, M.; Canino, G.J.; Woodbury, M.A.; Ribera, J.C. The psychological sequelae of disaster stress prospectively and retrospectively evaluated. Am. J. Community Psychol. 1990, 18, 661–680. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Franzini, M. Redistribuire non basta. Politiche pre-distributive per una società più giusta e meno diseguale. Soc. Cohes. Pap. 2022, 4, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Grignoli, D.; Boriati, D. Sovrapposizioni di disuguaglianza e percorsi educativi. Un’esperienza nell’era del COVID. Filos. Morale 2023, 3, 145–158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Openpolis. Le Aree Interne, Tra Spopolamento e Carenza di Servizi; Fondazione Openpolis: Roma, Italy, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Rockström, J.; Norström, A.V.; Matthews, N.; Biggs, R.; Folke, C.; Harikishun, A.; Huq, S.; Krishnan, N.; Warszawski, L.; Nel, D. Shaping a resilient future in the response to COVID-19. Nat. Sustain. 2023, 8, 897–907. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).