Exploring How and When Environmental Corporate Social Responsibility Impacts Employees’ Green Innovative Work Behavior: The Mediating Role of Creative Self-Efficacy and Environmental Commitment

Abstract

:1. Introduction

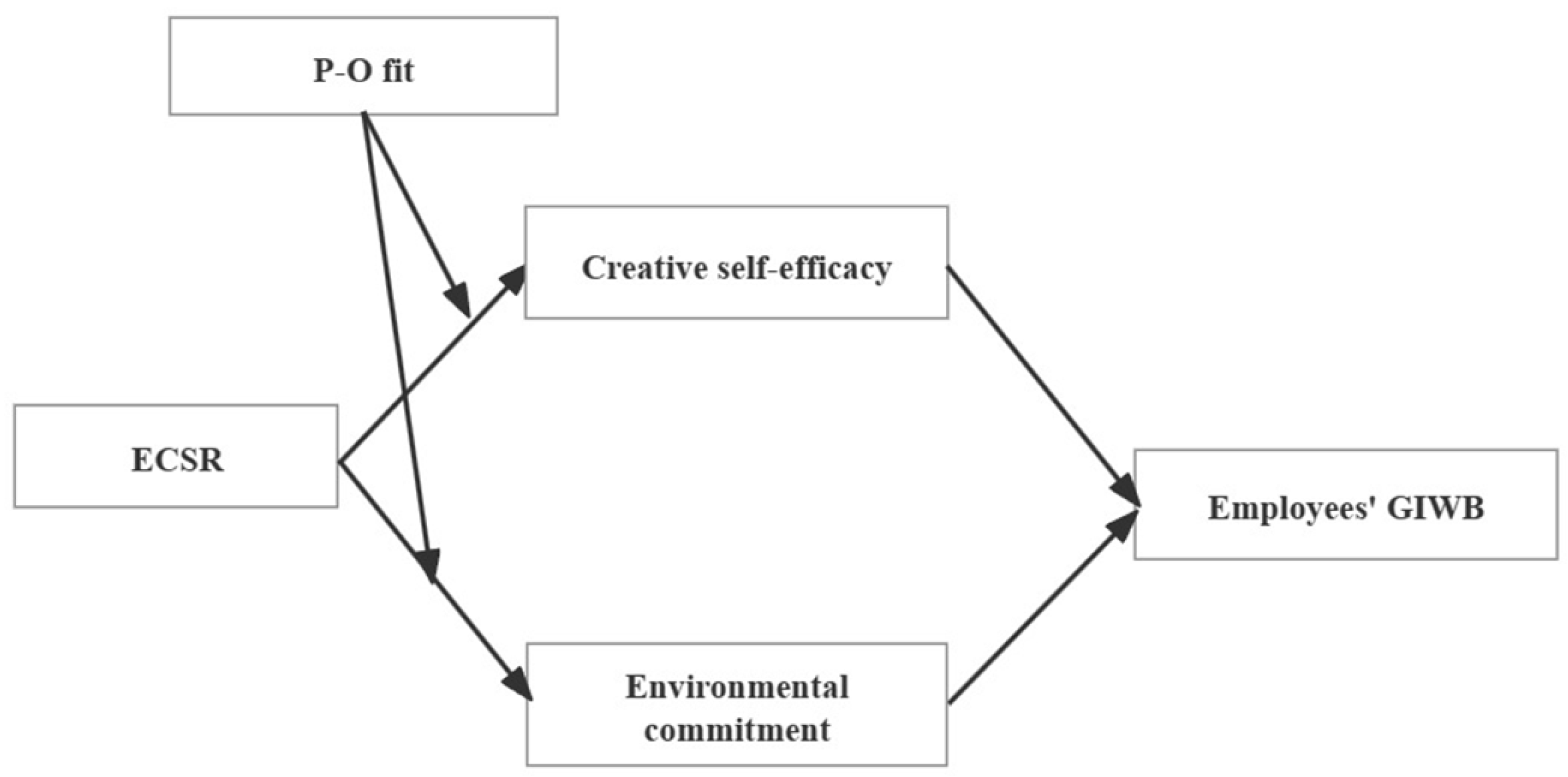

2. Theoretical Background and Hypotheses Development

2.1. S-O-R Framework

2.2. Environmental Corporate Social Responsibility (ECSR)

2.3. ECSR and Employees’ Green Innovative Work Behavior (GIWB) in the Chinese Manufacturing Sector

2.4. ECSR, Creative Self-Efficacy, and Employees’ GIWB

2.5. ECSR, Environmental Commitment, and Employees’ GIWB

2.6. Moderating Role of P-O Fit

3. Methods

3.1. Participants and Procedures

3.2. Measures

3.3. Control Variables

3.4. Common Method Bias (CMB)

3.5. Confirmatory Factor Analysis (CFA)

4. Results

4.1. Descriptive Statistics and Correlations

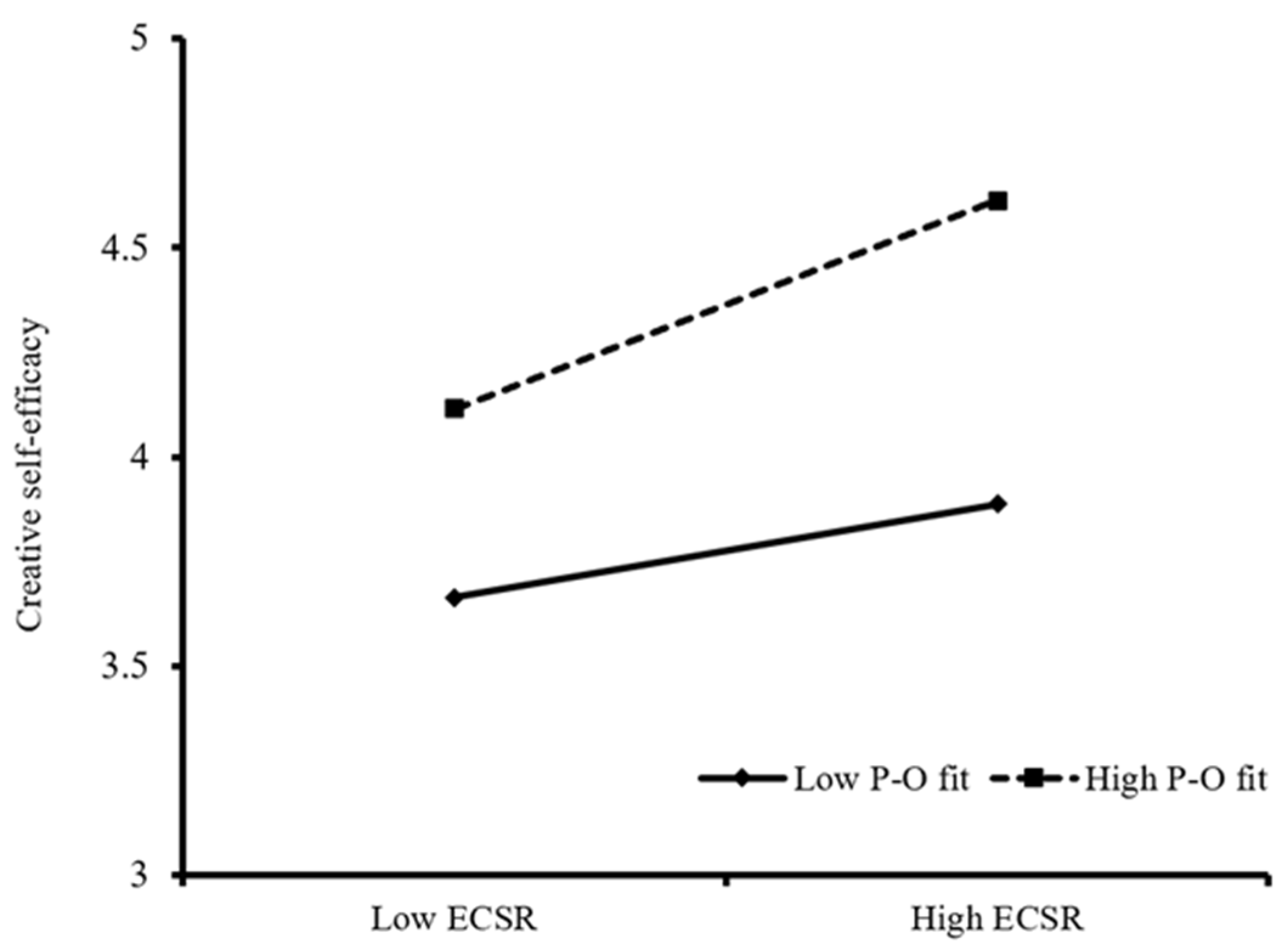

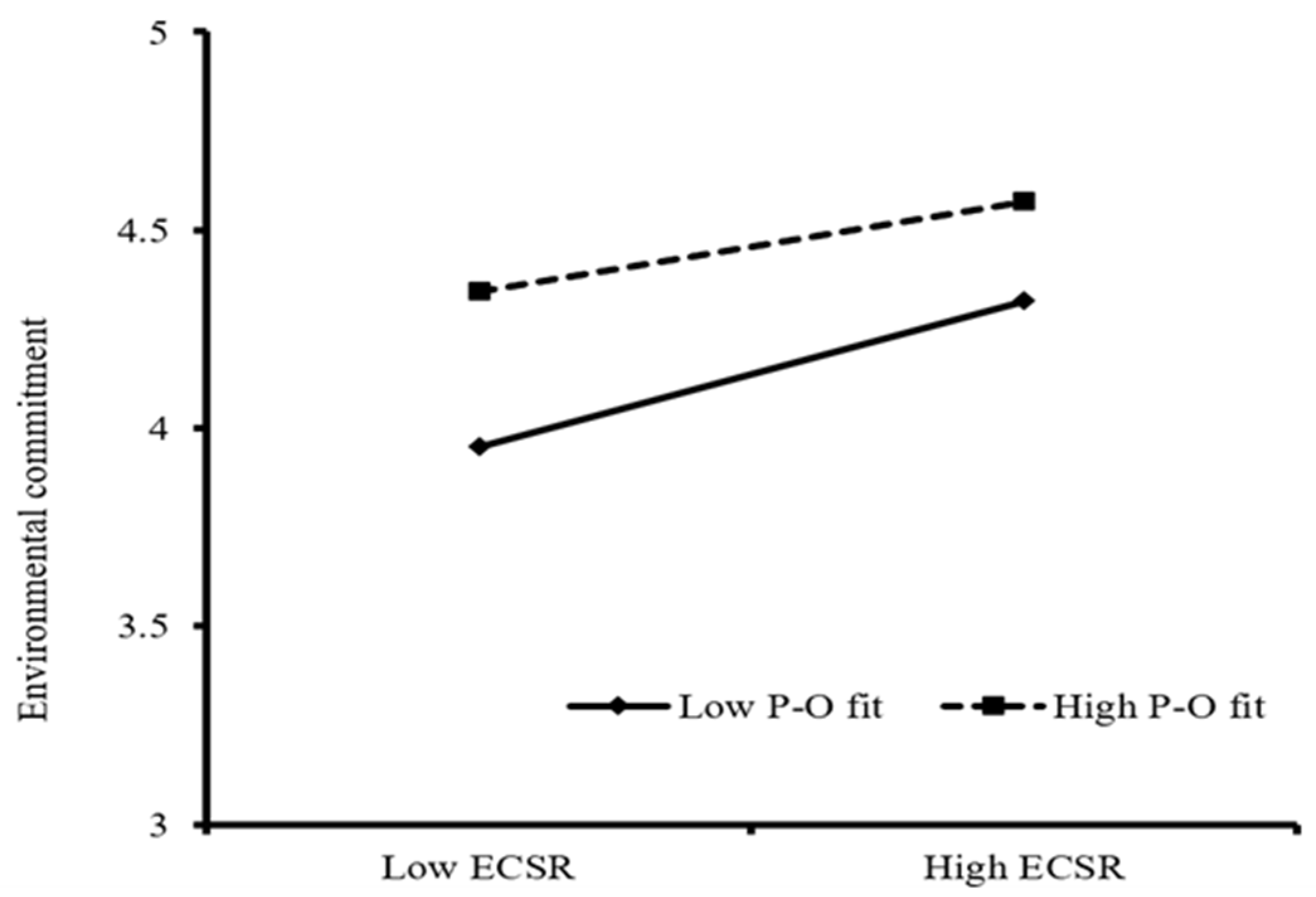

4.2. Hypotheses Testing

5. Discussion

5.1. Theoretical Implications

5.2. Practical Implications

5.3. Limitations and Future Directions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A

| Constructs | Items | References |

|---|---|---|

| ECSR | Compared with our major competitors: | Wei et al. (2015) [45] |

| Our products are more environmentally friendly. | ||

| Our production process requires fewer natural resources. | ||

| Our production process decreases environmental pollution. | ||

| Our products are easier to recycle for reuse. | ||

| P-O fit | My personal values match my organization’s values and culture. | Cable & DeRue (2002) [97] |

| The things that I value in life are very similar to the things that my organization values. | ||

| My organization’s values and culture provide a good fit with the things that I value in life. | ||

| Creative self-efficacy | I have confidence in my ability to solve problems creatively. | Tierney & Farmer (2002) [25] |

| I feel that I am good at generating novel ideas. | ||

| I have a knack for further developing the ideas of others. | ||

| I am good at finding creative ways to solve problems. | ||

| Environmental commitment | I really care about the environmental concern of my company. | Raineri & Paillé (2016) [72] |

| I would feel guilty about not supporting the environmental efforts of my company. | ||

| The environmental concern of my company means a lot to me. | ||

| I feel a sense of duty to support the environmental efforts of my company. | ||

| I really feel as if my company’s environmental problems are my own. | ||

| I feel personally attached to the environmental concern of my company. | ||

| I strongly value the environmental efforts of my company. | ||

| GIWB | I generate green creative ideas. | Aboramadan et al. (2022) [9] |

| I search out new environmentally-related technologies, processes, techniques and/or product ideas. | ||

| I promote and champion green ideas with others. | ||

| I Investigate and secure the funds needed to implement new green ideas. | ||

| I develop adequate plans and schedules for the implementation of new green ideas. | ||

| I am environmentally innovative. |

References

- Li, G.P.; Wang, X.; Wu, J. How scientific researchers form green innovation behavior: An empirical analysis of China’s enterprises. Technol. Soc. 2019, 56, 134–146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, D.; Wang, L.F. Does environmental corporate social responsibility (ECSR) promote green product and process innovation? Manag. Decis. Econ. 2022, 43, 1439–1447. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chang, C.H. The influence of corporate environmental ethics on competitive advantage: The mediation role of green innovation. J. Bus. Ethics 2011, 104, 361–370. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Y.; Lai, S.; Wen, C. The influence of green innovation performance on corporate advantage in Taiwan. J. Bus. Ethics 2006, 67, 331–339. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Y.S. The driver of green innovation and green image–green core competence. J. Bus. Ethics 2008, 81, 531–543. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Y.S.; Chang, C.H. The determinants of green product development performance: Green dynamic capabilities, green transformational leadership, and green creativity. J. Bus. Ethics 2012, 116, 107–119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aboramadan, M. The effect of green HRM on employee green behaviors in higher education: The mediating mechanism of green work engagement. Int. J. Organ. Anal. 2020, 30, 7–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aboramadan, M.; Kundi, Y.M.; Farao, C. Examining the effects of environmentally-specific servant leadership on green work outcomes among hotel employees: The mediating role of climate for green creativity. J. Hosp. Market. Manag. 2021, 30, 929–956. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aboramadan, M.; Crawford, J.; Türkmenoğlu, M.A.; Farao, C. Green inclusive leadership and employee green behaviors in the hotel industry: Does perceived green organizational support matter? Int. J. Hosp. Manag. 2022, 107, 103330. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scott, S.G.; Bruce, R.A. Determinants of Innovative Behavior: A path model of individual innovation in the workplace. Acad. Manag. J. 1994, 37, 580–607. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Katz, D.; Kahn, R.L. The Social Psychology of Organizations; Wiley: New York, NY, USA, 1978. [Google Scholar]

- Kuo, C.; Ni, Y.L.; Wu, C.; Duh, R.; Chen, M.Y.; Chang, C. When can felt accountability promote innovative work behavior? The role of transformational leadership. Pers. Rev. 2021, 51, 1807–1822. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Janssen, O. Job demands, perceptions of effort-reward fairness and innovative work behavior. J. Occup. Organ. Psychol. 2000, 73, 287–302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- O’Reilly, C.A.; Chatman, J.A. Organizational commitment and psychological attachment: The effects of compliance, identification, and internalization on prosocial behavior. J. Appl. Psychol. 1986, 71, 492–499. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Afridi, S.A.; Afsar, B.; Shahjehan, A.; Khan, W.; Rehman, Z.U.; Khan, M.A.S. Impact of corporate social responsibility attributions on employee’s extra-role behaviors: Moderating role of ethical corporate identity and interpersonal trust. Corp. Soc. Responsib. Environ. Manag. 2023, 30, 991–1004. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Wu, J.; Fan, Y. The effect of perceived organizational support toward the environment on team green innovative behavior: Evidence from Chinese green factories. Emerg. Mark. Financ. Trade 2022, 58, 2326–2341. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ruan, R.; Wan, C.; Zhu, Z. Research on the relationship between environmental corporate social responsibility and green innovative behavior: The moderating effect of moral identity. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 2022, 29, 52189–52203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Z.; Ren, S.; Chadee, D.; Sun, C. The influence of exploitative leadership on hospitality employees’ green innovative behavior: A moderated mediation model. Int. J. Hosp. Manag. 2021, 99, 103058. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, J.; Tang, W.; Zhang, B.; Wang, H. Influence of Environmentally Specific Transformational Leadership on Employees’ Green Innovation Behavior—A Moderated Mediation Model. Sustainability 2022, 14, 1828. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Roeck, K.; Farooq, O. Corporate social responsibility and ethical leadership: Investigating their interactive effect on employees’ socially responsible behaviors. J. Bus. Ethics 2018, 151, 923–939. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salancik, G.R.; Pfeffer, J. A social information processing approach to job attitudes and task design. Adm. Sci. Q. 1978, 232, 224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yin, C.; Ma, H.; Gong, Y.; Chen, Q.; Zhang, Y. Environmental CSR and environmental citizenship behavior: The role of employees’ environmental passion and empathy. J. Clean. Prod. 2021, 320, 128751. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, H.; Chua, B.; Ariza-Montes, A.; Untaru, E. Effect of environmental corporate social responsibility on green attitude and norm activation process for sustainable consumption: Airline versus restaurant. Corp. Soc. Responsib. Environ. Manag. 2020, 27, 1851–1864. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mehrabian, A.; Russell, J.A. An Approach to Environmental Psychology; MIT Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 1974. [Google Scholar]

- Tierney, P.; Farmer, S.M. Creative Self-Efficacy: Its potential antecedents and relationship to creative performance. Acad. Manag. J. 2002, 45, 1137–1148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cantor, D.E.; Morrow, P.C.; Montabon, F. Engagement in environmental behaviors among supply chain management employees: An organizational support theoretical perspective. J. Supply Chain. Manag. 2012, 48, 33–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chatman, J.A. Improving interactional organizational research: A model of person-organization fit. Acad. Manag. Rev. 1989, 14, 333–349. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kristof, A.L. Person–organization fit: An integrative review of its conceptualizations, measurement, and implications. Pers. Psychol. 1996, 49, 1–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, D.; Wang, L.; Sun, C.; Wu, D.; Mao, W.; Hu, Y. The relationship between perceived corporate environmental responsibility and employees’ pro-environmental behavior: A moderated serial mediation model. Corp. Soc. Responsib. Environ. Manag. 2023, 30, 2606–2622. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baker, J.; Grewal, D.; Parasuraman, A. The influence of store environment on quality inferences and store image. J. Acad. Market. Sci. 1994, 22, 328–339. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bagozzi, R.P. Comment on “Antecedents of performance and satisfaction in a service sale force as compared to an industrial sales force”. J. Pers. Sell. Sales Manag. 1986, 6, 49–51. [Google Scholar]

- Ahn, J.A.; Seo, S. Consumer responses to interactive restaurant self-service technology (IRSST): The role of gadget-loving propensity. Int. J. Hosp. Manag. 2018, 74, 109–121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leung, X.Y.; Wen, H. Chatbot usage in restaurant takeout orders: A comparison study of three ordering methods. J. Hosp. Tour. Manag. 2020, 45, 377–386. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leung, X.Y.; Torres, B.J.V.; Fan, A. Do kiosks outperform cashiers? An S-O-R framework of restaurant ordering experiences. J. Hosp. Tour. Technol. 2021, 12, 580–592. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eroğlu, S.; Machleit, K.A.; Davis, L. Atmospheric qualities of online retailing. J. Bus. Res. 2001, 54, 177–184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kuo, Y.; Chen, F. The effect of interactivity of brands’ marketing activities on Facebook fan pages on continuous participation intentions: An S–O-R framework study. J. Retail. Consum. Serv. 2023, 74, 103446. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gong, Y.; Huang, J.; Farh, J. Employee learning orientation, transformational leadership, and employee creativity: The mediating role of employee creative self-Efficacy. Acad. Manag. J. 2009, 52, 765–778. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tuan, L.T. Green creative behavior in the tourism industry: The role of green entrepreneurial orientation and a dual-mediation mechanism. J. Sustain. Tour. 2020, 29, 1290–1318. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, J.; Wang, H.; Zhang, Z.; Ru, X. Examining when and how perceived sustainability-related climate influences pro-environmental behaviors of tourism destination residents in China. J. Hosp. Tour. Manag. 2021, 48, 357–367. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, W.; Ma, Y.; Fan, X.; Peng, X. Corporate environmental ethics and employee’s green creativity? The perspective of environmental commitment. Corp. Soc. Responsib. Environ. Manag. 2023, 30, 1856–1868. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chang, C.H.; Chen, Y.S. Green organizational identity and green innovation. Manag. Decis. 2013, 51, 1056–1070. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, W.; Yu, H.; Xu, H. Effects of green human resource management and managerial environmental concern on green innovation. Eur. J. Innov. Manag. 2020, 24, 951–967. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mazurkiewicz, P. Corporate Environmental Responsibility: Is a Common CSR Framework Possible? World Bank Working Paper; Woold Bank: Washington, DC, USA, 2004; Available online: http://siteresources.worldbank.org/EXTDEVCOMSUSDEVT/Resources/csrframework.pdf (accessed on 24 December 2023).

- Chuang, S.; Huang, S. The Effect of environmental corporate social responsibility on environmental performance and business competitiveness: The mediation of green information technology capital. J. Bus. Ethics 2018, 150, 991–1009. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wei, Z.; Shen, H.; Zhou, K.Z.; Li, J.J. How does environmental corporate social responsibility matter in a dysfunctional institutional environment? Evidence from China. J. Bus. Ethics 2015, 140, 209–223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Flammer, C. Corporate social responsibility and shareholder reaction: The environmental awareness of investors. Acad. Manag. J. 2013, 56, 758–781. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Turker, D. How corporate social responsibility influences organizational commitment. J. Bus. Ethics 2009, 89, 189–204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baughn, C.C.; Bodie, K.L.; McIntosh, J.C. Corporate social and environmental responsibility in Asian countries and other geographical regions. Corp. Soc. Responsib. Environ. Manag. 2007, 14, 189–205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rahman, N.; Post, C. Measurement issues in environmental corporate social responsibility (ECSR): Toward a transparent, reliable, and construct valid instrument. J. Bus. Ethics 2012, 105, 307–319. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- García-Piqueres, G.; García-Ramos, R. Is the corporate social responsibility–innovation link homogeneous? Looking for sustainable innovation in the Spanish context. Corp. Soc. Responsib. Environ. Manag. 2020, 27, 803–814. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, J.; Wei, J.; Lu, L. Strategic stakeholder management, environmental corporate social responsibility engagement, and financial performance of stigmatized firms derived from Chinese special environmental policy. Bus. Strategy Environ. 2019, 28, 1027–1044. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Forcadell, F.J.; Úbeda, F.; Aracil, E. Effects of environmental corporate social responsibility on innovativeness of Spanish industrial SMEs. Technol. Forecast. Soc. 2021, 162, 120355. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rela, I.Z.; Awang, A.H.; Ramli, Z.; Sum, S.M.; Meisanti, M. Effects of environmental corporate social responsibility on environmental well-being perception and the mediation role of community resilience. Corp. Soc. Responsib. Environ. Manag. 2020, 27, 2176–2187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Roeck, K.; Delobbe, N. Do environmental CSR initiatives serve organizations’ legitimacy in the oil industry? Exploring employees’ reactions through organizational identification theory. J. Bus. Ethics 2012, 110, 397–412. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chang, T.; Yeh, Y.; Li, H. How to shape an organization’s sustainable green management performance: The mediation effect of environmental corporate social responsibility. Sustainability 2020, 12, 9198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Latif, B.; Gunarathne, N.; Gaskin, J.; Ong, T.S.; Ali, M. Environmental corporate social responsibility and pro-environmental behavior: The effect of green shared vision and personal ties. Resour. Conserv. Recycl. 2022, 186, 106572. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ruepert, A.; Keizer, K.; Steg, L. The relationship between corporate environmental responsibility, employees’ biospheric values and pro-environmental behavior at work. J. Environ. Psychol. 2017, 54, 65–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tian, Q.; Robertson, J.L. How and when does perceived CSR affect employees’ engagement in voluntary pro-environmental behavior? J. Bus. Ethics 2017, 155, 399–412. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bandura, A. Self-Efficacy: The Exercise of Control; Macmillan: New York, NY, USA, 1997. [Google Scholar]

- Gist, M.E.; Mitchell, T.R. Self-efficacy: A theoretical analysis of its determinants and malleability. Acad. Manag. Rev. 1992, 17, 183–211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alhmoudi, R.S.; Singh, S.K.; Caputo, F.; Riso, T.; Iandolo, F. Corporate social responsibility and innovative work behavior: Is it a matter of perceptions? Corp. Soc. Responsib. Environ. Manag. 2022, 29, 2030–2037. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fu, Q.; Ghardallou, W.; Comite, U.; Siddique, I.; Han, H.; Arjona-Fuentes, J.M.; Ariza-Montes, A. The Role of CSR in Promoting Energy-Specific Pro-Environmental Behavior among Hotel Employees. Sustainability 2022, 14, 6574. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ren, S.; Jiang, K.; Tang, G. Leveraging green HRM for firm performance: The joint effects of CEO environmental belief and external pollution severity and the mediating role of employee environmental commitment. Hum. Resour. Manag. 2021, 61, 75–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wan, J.; Gu, Q. Leader creativity expectations motivate employee creativity: A moderated mediation examination. Int. J. Hum. Resour. Manag. 2015, 28, 724–749. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jaiswal, N.K.; Dhar, R.L. Transformational leadership, innovation climate, creative self-efficacy and employee creativity: A multilevel study. Int. J. Hosp. Manag. 2015, 51, 30–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bigné, E.; Andreu, L.; Pérez, C.; Ruiz, C. Brand love is all around: Loyalty behavior, active and passive social media users. Curr. Issues Tour. 2020, 23, 1613–1630. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, D.; Jiang, K.; Shalley, C.E.; Keem, S.; Zhou, J. Motivational mechanisms of employee creativity: A meta-analytic examination and theoretical extension of the creativity literature. Organ. Behav. Hum. Decis. Process. 2016, 137, 236–263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Herscovitch, L.; Meyer, J.P. Commitment to organizational change: Extension of a three-component model. J. Appl. Psychol. 2002, 87, 474–487. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Meyer, J.P.; Allen, N.J. A three-component conceptualization of organizational commitment. Hum. Resour. Manag. Rev. 1991, 1, 61–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Polonsky, M.J. Incorporating ethics into business students’ research projects: A process approach. J. Bus. Ethics 1998, 17, 1227–1241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Keogh, P.D.; Polonsky, M.J. Environmental commitment: A basis for environmental entrepreneurship? J. Organ. Chang. Manag. 1998, 11, 38–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raineri, N.; Paillé, P. Linking corporate policy and supervisory support with environmental citizenship behaviors: The role of employee environmental beliefs and commitment. J. Bus. Ethics 2016, 137, 129–148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reverte, C. The impact of better corporate social responsibility disclosure on the cost of equity capital. Corp. Soc. Responsib. Environ. Manag. 2011, 19, 253–272. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Afsar, B.; Umrani, W.A. Corporate social responsibility and pro-environmental behavior at workplace: The role of moral reflectiveness, coworker advocacy, and environmental commitment. Corp. Soc. Responsib. Environ. Manag. 2019, 27, 109–125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zientara, P.; Zamojska, A. Green organizational climates and employee pro-environmental behavior in the hotel industry. J. Sustain. Tour. 2018, 26, 1142–1159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shah, S.H.A.; Al-Ghazali, B.M.; Bhatti, S.; Aman, N.; Fahlevi, M.; Aljuaid, M.; Hasan, F. The Impact of Perceived CSR on Employees’ Pro-Environmental Behaviors: The Mediating Effects of Environmental Consciousness and Environmental Commitment. Sustainability 2023, 15, 4350. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paillé, P.; Valéau, P. “I don’t owe you, but I am committed”: Does felt obligation matter on the effect of green training on employee environmental commitment? Organ. Environ. 2020, 34, 123–144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharma, S.; Prakash, G.; Kumar, A.; Mussada, E.K.; Antony, J.; Luthra, S. Analysing the relationship of adaption of green culture, innovation, green performance for achieving sustainability: Mediating role of employee commitment. J. Clean. Prod. 2021, 303, 127039. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paillé, P.; Morelos, J.H.M.; Raineri, N.; Stinglhamber, F. The influence of the immediate manager on the avoidance of non-green behaviors in the workplace: A three-wave moderated-mediation model. J. Bus. Ethics 2017, 155, 723–740. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gladwin, T.N.; Kennelly, J.J.; Krause, T. Shifting paradigms for sustainable development: Implications for management theory and research. Acad. Manag. Rev. 1995, 20, 874–907. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kristof-Brown, A.L.; Zimmerman, R.D.; Johnson, E.C. Consequences of individuals’ fit at work: A meta-analysis of person-job, person-organization, person-group, and person supervisor fit. Pers. Psychol. 2005, 58, 281–342. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Verquer, M.L.; Beehr, T.A.; Wagner, S.H. A meta-analysis of relations between person-organization fit and work attitudes. J. Vocat. Behav. 2003, 63, 473–489. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, P.; Sparrow, P.; Cooper, C.L. The relationship between person-organization fit and job satisfaction. J. Manag. Psychol. 2016, 31, 946–959. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, H.; Zhou, Q.; He, P.; Jiang, C. How and when does socially responsible HRM affect employees’ organizational citizenship behaviors toward the environment? J. Bus. Ethics 2019, 169, 371–385. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sørlie, H.O.; Hetland, J.; Bakker, A.B.; Espevik, R.; Olsen, O.K. Daily autonomy and job performance: Does person-organization fit act as a key resource? J. Vocat. Behav. 2022, 133, 103691. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Valentine, S.; Godkin, L.; Lucero, M. Ethical context, organizational commitment, and person-organization fit. J. Bus. Ethics 2002, 41, 349–360. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, M.; Lyu, Y.; Li, Y.; Xing, Z.; Li, W. The impact of high-commitment HR practices on hotel employees’ proactive customer service performance. Cornell Hosp. Q. 2016, 58, 94–107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Hoogh, A.H.B.; Hartog, D.N.D. Neuroticism and locus of control as moderators of the relationships of charismatic and autocratic leadership with burnout. J. Appl. Psychol. 2009, 94, 1058–1067. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wei, S.; Wang, L.; Jiang, W.; Feng, L.; Feng, T. How eco-control systems enhance carbon performance via low-carbon supply chain collaboration? The moderating role of organizational unlearning. Corp. Soc. Responsib. Environ. Manag. 2023, 30, 2536–2554. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, Y.; Wang, L.; Yang, Q. Do corporate environmental ethics influence firms’ green practice? The mediating role of green innovation and the moderating role of personal ties. J. Clean. Prod. 2020, 266, 122054. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Glavas, A.; Kelley, K. The effects of perceived corporate social responsibility on employee attitudes. Bus. Ethics Q. 2014, 24, 165–202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Onkila, T. Pride or embarrassment? Employees’ emotions and corporate social responsibility. Corp. Soc. Responsib. Environ. Manag. 2013, 22, 222–236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Podsakoff, P.M.; MacKenzie, S.B.; Lee, J.Y.; Podsakoff, N.P. Common method biases in behavioral research: A critical review of the literature and recommended remedies. J. Appl. Psychol. 2003, 88, 879–903. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Z.; Jiang, F. It is not only what you do, but why you do it: The role of attribution in employees’ emotional and behavioral responses to illegitimate tasks. J. Vocat. Behav. 2023, 142, 103860. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aguinis, H.; Villamor, I.; Ramani, R.S. MTurk research: Review and recommendations. J. Manag. 2020, 47, 823–837. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rupp, D.E.; Ganapathi, J.; Aguilera, R.V.; Williams, C.A. Employee reactions to corporate social responsibility: An organizational justice framework. J. Organ. Behav. 2006, 27, 537–543. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cable, D.M.; DeRue, D.S. The convergent and discriminant validity of subjective fit perceptions. J. Appl. Psychol. 2002, 87, 875–884. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhou, P.; Arndt, F.; Jiang, K.; Dai, W. Looking backward and forward: Political links and environmental corporate social responsibility in China. J. Bus. Ethics 2020, 169, 631–649. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kock, N. Common method bias in PLS-SEM: A full collinearity assessment approach. Int. J. e-Collab. 2015, 11, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hayes, A.F. PROCESS macro (Version 3.3). 2019. Available online: https://processmacro.org (accessed on 24 December 2023).

- Kim, S.; Park, H.J. Corporate social responsibility as an organizational attractiveness for prospective public relations practitioners. J. Bus. Ethics 2011, 103, 639–653. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmed, M.; Sun, Z.; Raza, S.A.; Qureshi, M.A.; Yousufi, S.Q. Impact of CSR and environmental triggers on employee green behavior: The mediating effect of employee well-being. Corp. Soc. Responsib. Environ. Manag. 2020, 27, 2225–2239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Su, L.; Swanson, S.R. Perceived corporate social responsibility’s impact on the well-being and supportive green behaviors of hotel employees: The mediating role of the employee-corporate relationship. Tour. Manag. 2019, 72, 437–450. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arnaud, A.; Sekerka, L.E. Positively ethical: The establishment of innovation in support of sustainability. Int. J. Sustain. Strateg. Manag. 2010, 2, 121–137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Demographics | Sample No. (%) (N = 300) | |

|---|---|---|

| Gender | ||

| Female | 146 (48.67%) | |

| Male | 154 (51.33%) | |

| Age | ||

| Under 30 years | 123 (41%) | |

| 31–40 years | 156 (52%) | |

| Over 40 years | 21 (7%) | |

| Ownership | ||

| State-owned enterprise | 80 (26.67%) | |

| Private-owned enterprise | 191 (63.67%) | |

| Foreign-invested enterprise | 29 (9.66%) | |

| Education | ||

| Junior college or below | 65 (21.67%) | |

| Undergraduate | 203 (67.67%) | |

| Postgraduate or above | 32 (10.66%) | |

| Grade | ||

| Frontline employee | 148 (49.33%) | |

| Supervisor | 152 (50.67) |

| Models | Factor Loaded | χ2 | Df | Δχ2(Δdf) | CFI | TLI | RMSEA |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 5-factor model | ECSR, POF, EC, CSE, GIWB | 415.93 | 242 | - | 0.93 | 0.92 | 0.05 |

| 4-factor model | ECSR, POF, EC + CSE, GIWB | 532.46 | 246 | 116.53(4) | 0.89 | 0.88 | 0.06 |

| 3-factor model | ECSR, POF, EC + CSE + GIWB | 625.76 | 249 | 209.83(7) | 0.86 | 0.84 | 0.07 |

| 2-factor model | ECSR, POF + EC + CSE + GIWB | 777.77 | 251 | 361.84(9) | 0.80 | 0.78 | 0.08 |

| 1-factor model | ECSR + OC + POF + JI + EGIB | 839.93 | 252 | 424(10) | 0.78 | 0.75 | 0.09 |

| Variables | M | SD | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. ECSR | 4.14 | 0.58 | 1 | ||||

| 2. P-O fit | 4.09 | 0.60 | 0.55 ** | 1 | |||

| 3. Creative self-efficacy | 4.01 | 0.62 | 0.46 ** | 0.56 ** | 1 | ||

| 4. Environmental commitment | 4.32 | 0.52 | 0.53 ** | 0.54 ** | 0.52 ** | 1 | |

| 5. GIWB | 4.10 | 0.60 | 0.48 ** | 0.46 ** | 0.56 ** | 0.56 ** | 1 |

| Creative Self-Efficacy | Environmental Commitment | GIWB | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Variables | Model1 | Model2 | Model3 | Model4 | Model5 | Model6 | Model7 | Model8 |

| Gender | 0.00 | −0.00 | 0.03 | 0.03 | 0.02 | 0.02 | 0.01 | 0.01 |

| Age | −0.11 * | −0.10 * | −0.04 | −0.04 | −0.05 | −0.00 | −0.03 | −0.00 |

| Ownership | −0.09 | −0.08 | 0.05 | 0.06 | 0.02 | 0.06 | 0.00 | 0.04 |

| Education | 0.06 | 0.03 | 0.00 | −0.03 | 0.05 | 0.02 | 0.05 | 0.03 |

| Grade | 0.16 ** | 0.10 * | 0.08 | 0.02 | 0.05 | −0.02 | 0.01 | −0.03 |

| ECSR | 0.44 *** | 0.29 *** | 0.52 *** | 0.29 *** | 0.47 *** | 0.28 *** | 0.25 *** | 0.18 ** |

| Creative self-efficacy | 0.43 *** | 0.33 *** | ||||||

| Environmental commitment | 0.42 *** | 0.30 *** | ||||||

| P-O fit | 0.47 *** | 0.31 *** | ||||||

| ECSR×P-O fit | 0.19 ** | −0.12 * | ||||||

| R2 | 0.26 | 0.40 | 0.29 | 0.38 | 0.24 | 0.38 | 0.36 | 0.43 |

| ΔR2 | 0.19 | 0.02 | 0.27 | 0.01 | 0.22 | 0.14 | 0.12 | 0.05 |

| Adjusted R2 | 0.25 | 0.38 | 0.27 | 0.36 | 0.22 | 0.36 | 0.35 | 0.41 |

| F | 17.38 *** | 23.74 *** | 19.80 *** | 22.25 *** | 15.21 *** | 25.10 *** | 23.67 *** | 27.40 *** |

| Mediation | Effect | SE | 95% CI |

|---|---|---|---|

| Creative self-efficacy | 0.14 | 0.04 | [0.08, 0.22] |

| Environmental commitment | 0.16 | 0.05 | [0.07, 0.27] |

| Total indirect | 0.30 | 0.58 | [0.20, 0.43] |

| Contrasts (Creative self-efficacy vs. Environmental commitment) | −0.01 | 0.06 | [−0.15, 0.10] |

| Path | Levels of Moderator (P-O Fit) | Conditional Indirect Effect | SE | 95%CI | Index | Pass or Not |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ECSR-Creative self-efficacy-GIWB | −1SD | 0.06 | 0.03 | [0.01, 0.12] | 0.06 [0.01, 0.14] | Pass |

| +1SD | 0.13 | 0.04 | [0.06, 0.24] | |||

| Contrasts | 0.07 | 0.04 | [0.01, 0.16] | |||

| ECSR- Environmental commitment -GIWB | −1SD | 0.11 | 0.04 | [0.04, 0.21] | −0.03 [−0.11, 0.02] | Not |

| +1SD | 0.07 | 0.03 | [0.02, 0.14] | |||

| Contrasts | −0.04 | 0.04 | [−0.12, 0.03] |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Chen, J.; Zhang, A. Exploring How and When Environmental Corporate Social Responsibility Impacts Employees’ Green Innovative Work Behavior: The Mediating Role of Creative Self-Efficacy and Environmental Commitment. Sustainability 2024, 16, 234. https://doi.org/10.3390/su16010234

Chen J, Zhang A. Exploring How and When Environmental Corporate Social Responsibility Impacts Employees’ Green Innovative Work Behavior: The Mediating Role of Creative Self-Efficacy and Environmental Commitment. Sustainability. 2024; 16(1):234. https://doi.org/10.3390/su16010234

Chicago/Turabian StyleChen, Jiali, and Aiqing Zhang. 2024. "Exploring How and When Environmental Corporate Social Responsibility Impacts Employees’ Green Innovative Work Behavior: The Mediating Role of Creative Self-Efficacy and Environmental Commitment" Sustainability 16, no. 1: 234. https://doi.org/10.3390/su16010234

APA StyleChen, J., & Zhang, A. (2024). Exploring How and When Environmental Corporate Social Responsibility Impacts Employees’ Green Innovative Work Behavior: The Mediating Role of Creative Self-Efficacy and Environmental Commitment. Sustainability, 16(1), 234. https://doi.org/10.3390/su16010234