Perceived Risk and Food Tourism: Pursuing Sustainable Food Tourism Experiences

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Literature Review

2.1. Perceived Risk

2.2. Theory of Planned Behavior and Extended Theory of Planned Behavior

2.3. Coping Behavior

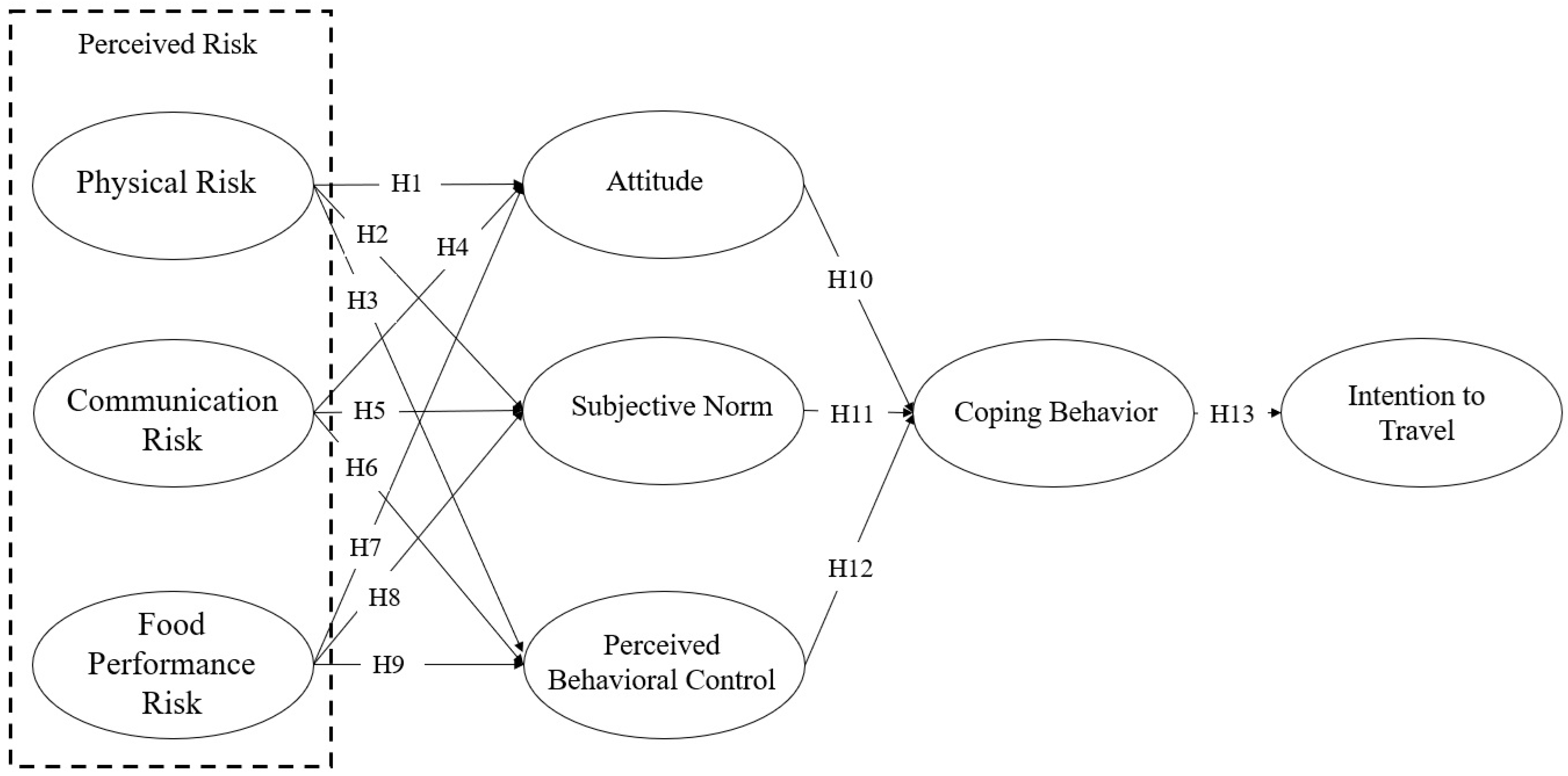

2.4. The Relationships between Constructs

2.4.1. Perceived Risk and TPB Variables

2.4.2. TPB Variables and Coping Behaviors

2.4.3. Coping Behaviors and Intention to Travel

3. Methodology

3.1. Construct Measurement

3.2. Sampling and Data Collection

3.3. Data Analysis

4. Results

4.1. Descriptive Statistics

4.2. Exploratory Factor Analysis (EFA)

4.3. Confirmatory Factor Analysis (CFA)

4.4. Testing Hypotheses

5. Conclusions

6. Implications, Limitations, and Future Research Directions

6.1. Theoretical Implications

6.2. Practical Implications

6.3. Limitations and Future Research Directions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Horng, J.S.; Tsai, C.T. Culinary tourism strategic development: An Asia-Pacific perspective. Int. J. Tour. Res. 2012, 14, 40–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Du Rand, G.E.; Heath, E.; Alberts, N. The role of local and regional food in destination marketing: A South African situation analysis. In Wine, Food, and Tourism Marketing; Routledge: Binghamton, NY, USA, 2013; pp. 97–112. [Google Scholar]

- Rousta, A.; Jamshidi, D. Food tourism value: Investigating the factors that influence tourists to revisit. J. Vacat. Mark. 2020, 26, 73–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baek, K.; Choe, Y.; Lee, S.; Lee, G.; Pae, T. The effects of the pilgrimage to the Christian Holy Land on the meaning in life and quality of life as moderated by the tourist’s faith maturity. Sustainability 2022, 14, 2891. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yoo, J.; Choe, Y.; Lee, G. Exploring pilgrimage value by ZMET: The mind of Christian pilgrims. Ann. Tour. Res. 2022, 96, 103466. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Q.; Huang, R. Local food in China: A viable destination attraction. Br. Food J. 2018, 120, 146–157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sims, R. Food, place and authenticity: Local food and the sustainable tourism experience. J. Sustain. Tour. 2009, 17, 321–336. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Everett, S.; Slocum, S.L. Food and tourism: An effective partnership? A UK-based review. J. Sustain. Tour. 2013, 21, 789–809. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wani, M.D.; Dada, Z.A.; Shah, S.A. Can consumption of local food contribute to sustainable tourism? Evidence from the perception of domestic tourists. Int. J. Sustain. Dev. World Ecol. 2023, 1–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kilcher, L. How organic agriculture contributes to sustainable development. Journal of Agricultural Research in the Tropics and Subtropics. Supplement 2007, 89, 31–49. [Google Scholar]

- Manioudis, M.; Meramveliotakis, G. Broad strokes towards a grand theory in the analysis of sustainable development: A return to the classical political economy. New Political Econ. 2022, 27, 866–878. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tomislav, K. The concept of sustainable development: From its beginning to the contemporary issues. Zagreb. Int. Rev. Econ. Bus. 2018, 21, 67–94. [Google Scholar]

- Choe, J.Y.J.; Kim, S.S. Effects of tourists’ local food consumption value on attitude, food destination image, and behavioral intention. Int. J. Hosp. Manag. 2018, 71, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chang, S.Y. The influence of novelty-seeking and risk-perception behavior on holiday decisions and food preferences. Int. J. Hosp. Tour. Adm. 2011, 12, 305–329. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ren, Y.; Choe, Y.; Song, H. Antecedents and consequences of brand equity: Evidence from Starbucks coffee brand. Int. J. Hosp. Manag. 2023, 108, 103351. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stewart, J.X.; Bramble, L.; Ziraldo, D. Key challenges in wine and culinary tourism with practical recommendation. Int. J. Contemp. Hosp. Manag. 2008, 20, 303–312. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Youn, H.; Kim, J.H. Is unfamiliarity a double-edged sword for ethnic restaurants? Int. J. Hosp. Manag. 2018, 68, 23–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Caber, M.; González-Rodríguez, M.R.; Albayrak, T.; Simonetti, B. Does perceived risk really matter in travel behaviour? J. Vacat. Mark. 2020, 26, 334–353. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moon, J.; Choe, Y.; Song, H. Determinants of consumers’ online/offline shopping behaviours during the COVID-19 pandemicInt. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2021, 18, 1593. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rather, R.A. Demystifying the effects of perceived risk and fear on customer engagement, co-creation and revisit intention during COVID-19: A protection motivation theory approach. J. Dest. Mark. Manag. 2021, 20, 100564. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sánchez-Cañizares, S.M.; Cabeza-Ramírez, L.J.; Muñoz-Fernández, G.; Fuentes-García, F.J. Impact of the perceived risk from COVID-19 on intention to travel. Curr. Issues Tour. 2021, 24, 970–984. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- An, S. Examining the Relationships among Perceived Risk, Attitude and Intention to Travel to Destinations along the U.S.-Mexico Border. Ph.D. Thesis, Texas A&M University, College Station, TX, USA, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Hasan, M.K.; Abdullah, S.K.; Lew, T.Y.; Islam, M.F. The antecedents of tourist attitudes to revisit and revisit intentions for coastal tourism. Int. J. Cult. Tour. Hosp. Res. 2019, 13, 218–234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abidin, Z.; Handayani, W.; Zaky, E.A.; Faturrahman, A.D. Perceived risk and attitude’s mediating role between tourism knowledge and visit intention during the COVID-19 pandemic: Implementation for coastal-ecotourism management. Heliyon 2020, 8, 10. [Google Scholar]

- Samdin, Z.; Abdullah, S.I.N.W.; Khaw, A.; Subramaniam, T. Travel risk in the ecotourism industry amid COVID-19 pandemic: Ecotourists’ perceptions. J. Ecotourism. 2022, 21, 266–294. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jun, S.H. The effects of perceived risk, brand credibility and past experience on purchase intention in the Airbnb context. Sustainability 2020, 12, 5212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yi, J.; Yuan, G.; Yoo, C. The effect of the perceived risk on the adoption of the sharing economy in the tourism industry: The case of Airbnb. Inf. Process. Manag. 2020, 57, 102108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hamid, S.; Bano, N. Behavioral intention of traveling in the period of COVID-19: An application of the theory of planned behavior (TPB) and perceived riskInt. J. Tour. Cities 2021, 8, 357–378. [Google Scholar]

- An, S.; Eck, T.; Yim, H. Understanding consumers’ acceptance intention to use mobile food delivery applications through an extended technology acceptance model. Sustainability 2023, 15, 832. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lim, H.R.; An, S. Intention to purchase wellbeing food among Korean consumers: An application of the Theory of Planned Behavior. Food Qual. Prefer. 2021, 88, 104101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seong, B.H.; Hong, C.Y. Does risk awareness of COVID-19 affect visits to national parks? Analyzing the tourist decision-making process using the theory of planned behavior. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2021, 18, 5081. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cristobal-Fransi, E.; Daries, N.; Ferrer-Rosell, B.; Marine-Roig, E.; Martin-Fuentes, E. Sustainable tourism marketing. Sustainability 2020, 12, 1865. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- UNWTO. Making Tourism More Sustainable: A Guide for Policy Makers; Bird, G., Ed.; United Nations Environment Programme: Paris, France, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Slovic, P. Perception of risk. Science 1987, 236, 280–285. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Choe, Y.; Wang, J.; Song, H. The impact of the Middle East Respiratory Syndrome coronavirus on inbound tourism in South Korea toward sustainable tourism. J. Sustain. Tour. 2021, 29, 1117–1133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sönmez, S.F.; Graefe, A.R. Determining future travel behavior from past travel experience and perceptions of risk and safety. J. Travel Res. 1998, 37, 171–177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaplan, L.B.; Szybillo, G.J.; Jacoby, J. Components of perceived risk in product purchase: A cross-validation. J Appl. Psychol. 1974, 59, 287–291. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boksberger, P.E.; Bieger, T.; Laesser, C. Multidimensional analysis of perceived risk in commercial air travel. J. Air Transp. Manag. 2007, 13, 90–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matiza, T.; Slabbert, E. Tourism is too dangerous! Perceived risk and the subjective safety of tourism activity in the era of COVID-19. Geoj. Tour. Geosites 2021, 36, 580–588. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moutinho, L. Consumer behaviour in Tourism. Eur. J. Mark. 1987, 21, 5–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roehl, W.S.; Fesenmaier, D.R. Risk perceptions and pleasure travel: An exploratory analysis. J. Travel Res. 1992, 30, 17–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tsaur, S.H.; Tzeng, G.H.; Wang, K.C. Evaluating tourist risks from fuzzy perspectives. Ann. Tour. Res. 1997, 24, 796–812. [Google Scholar]

- Grewal, D.; Gotlieb, J.; Marmorstein, H. The moderating effects of message framing and source credibility on the price-perceived risk relationship. J. Consum. Res. 1994, 21, 145–153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Björk, P.; Kauppinen-Räisänen, H. The impact of perceived risk on information search: A study of Finnish tourists. Scand. J. Hosp. Tour. 2011, 11, 306–323. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- An, M.; Lee, C.; Noh, Y. Risk factors at the destination: Their impact on air travel satisfaction and repurchase intention. Serv. Biz. 2010, 4, 155–166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Forsythe, S.M.; Shi, B. Consumer patronage and risk perceptions in Internet shopping. J. Bus. Res. 2003, 56, 867–875. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guttentag, D. Airbnb: Disruptive innovation and the rise of an informal tourism accommodation sector. Curr. Issues Tour. 2015, 18, 1192–1217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zervas, G.; Proserpio, D.; Byers, J.W. The rise of the sharing economy: Estimating the impact of Airbnb on the hotel industry. J. Mark. Res. 2017, 54, 687–705. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, J.Y. The Relationship of Perceived Risk to Personal Factors, Knowledge of Destination, and Travel Purchase Decisions in International Leisure Travel. Ph.D. Thesis, Virginia Polytechnic Institute and State University, Blacksburg, VA, USA, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Emami, A.; Ranjbarian, B. The perceived risk of iran as a tourism destination (A mixed method approach). Iran. J. Manag. Stud. 2019, 12, 45–67. [Google Scholar]

- Ajzen, I. From intentions to actions: A theory of planned behavior. In Action Control; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 1985; pp. 11–39. [Google Scholar]

- Ajzen, I. The theory of planned behavior. Organ. Behav. Hum. Decis. 1991, 50, 179–211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Armitage, C.J.; Conner, M. Efficacy of the theory of planned behaviour: A meta-analytic review. Br. J. Soc. Psychol. 2001, 40, 471–499. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ulker-Demirel, E.; Ciftci, G. A systematic literature review of the theory of planned behavior in tourism, leisure and hospitality management research. J. Hosp. Tour. Manag. 2020, 43, 209–219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Walker, K.; Moscardo, G. Encouraging sustainability beyond the tourist experience: Ecotourism, interpretation and values. J. Sustain. Tour. 2014, 22, 1175–1196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Su, D.N.; Johnson, L.W.; O’Mahony, B. Will foodies travel for food? Incorporating food travel motivation and destination foodscape into the theory of planned behavior. Asia Pac. J. Tour. Res. 2020, 25, 1012–1028. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abbasi, G.A.; Kumaravelu, J.; Goh, Y.N.; Singh, K.S.D. Understanding the intention to revisit a destination by expanding the theory of planned behaviour (TPB). Span. J. Mark. ESIC 2021, 25, 282–311. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Troise, C.; O’Driscoll, A.; Tani, M.; Prisco, A. Online food delivery services and behavioural intention—A test of an integrated TAM and TPB framework. Br. Food 2021, 122, 664–683. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seong, B.H.; Choi, Y.; Kim, H. Influential factors for sustainable intention to visit a national park during COVID-19: The extended theory of planned behavior with perception of risk and coping behavior. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2021, 18, 12968. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zeydan, Í.; Gürbüz, A. Examining tourists’ travel intentions in Türkiye during pandemic and post-pandemic period: The mediating effect of risk reduction behavior. J. Multidiscip. Acad Tour. 2023, 8, 171–183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shindler, B.; Shelby, B. Product shift in recreation settings: Findings and implications from panel research. Leis. Sci. 1995, 17, 91–107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Manning, R.E. Studies in Outdoor Recreation: Search and Research for Satisfaction; Oregon State University Press: Corvallis, OR, USA, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Chu, K.K.; Li, C.H. A study of the effect of risk-reduction strategies on purchase intentions in online shopping. Int. J. Electron. Bus. Manag. 2008, 6, 213–226. [Google Scholar]

- Adam, I. Backpackers’ risk perceptions and risk reduction strategies in Ghana. Tour. Manag. 2015, 49, 99–108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reichel, A.; Fuchs, G.; Uriely, N. Israeli backpackers: The role of destination choice. Ann. Tour. Res. 2009, 36, 222–246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, H.K.; Kim, Y. Protective behaviors against particulate air pollution: Self-construal, risk perception, and direct experience in the theory of planned behavior. Environ. Commun. 2021, 15, 1092–1108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dayour, F.; Park, S.; Kimbu, A.N. Backpackers’ perceived risks towards smartphone usage and risk reduction strategies: A mixed methods study. Tour. Manag. 2019, 72, 52–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Doran, A.; Pomfret, G. Exploring efficacy in personal constraint negotiation: An ethnography of mountaineering tourists. Tour. Stud. 2019, 19, 475–495. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Johnson, T.; Bruwer, J. Generic consumer risk-reduction strategies (RRS) in wine-related lifestyle segments of the Australian wine market. Int. J. Wine Mark. 2004, 16, 5–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, M.C. Factors influencing the adoption of internet banking: An integration of TAM and TPB with perceived risk and perceived benefit. Electron. Commer. Res. Appl. 2009, 8, 130–141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sanayei, A.; Bahmani, E. Integrating TAM and TPB with perceived risk to measure customers’ acceptance of internet banking. Int. J. Inf. Manag. 2012, 10, 25–37. [Google Scholar]

- Xie, Q.; Song, W.; Peng, X. Predictors for e-government adoption: Integrating TAM, TPB, trust and perceived risk. Electron. Libr. 2016, 35, 2–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ha, N. The impact of perceived risk on consumers’ online shopping intention: An integration of TAM and TPB. Manag. Sci. Lett. 2020, 10, 2029–2036. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tobias-Mamina, R.; Maziriri, E.T. Modelling consumers’ willingness to use card-less banking services: An integration of TAM and TPB. Int. J. Bus. Manag. 2020, 12, 241–257. [Google Scholar]

- Jomnonkwao, S.; Wisutwattanasak, P.; Ratanavaraha, V. Factors influencing willingness to pay for accident risk reduction among personal car drivers in Thailand. PLoS ONE 2021, 16, e0260666. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hsieh, H.S.; Kanda, Y.; Fujii, S. Incorporation of coping planning into the behavior change model that accounts for implementation intention. Transp. Res. F Traffic Psychol. 2019, 60, 228–244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morar, C.; Tiba, A.; Basarin, B.; Vujičić, M.; Valjarević, A.; Niemets, L.; Lukić, T. Predictors of changes in travel behavior during the COVID-19 pandemic: The role of tourists’ personalities. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2021, 18, 11169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Melania, A. The Relationship between Risk, Humor Coping Mechanism and Travel Behavior Intention of Quarantined Residents during COVID-19 Pandemic. Ph.D. Thesis, Universitas Andalas, West Sumatra, Indonesia, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Kurniawati, R. The Effects of Personal Attributes, Risk Perception, and Risk Reduction Strategies on Travel Intention for a Vulnerable Island Destination: The US Travelers’ Perspective for Bali, Indonesia. Ph.D. Thesis, University of Central Florida, Orlando, FL, USA, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Zheng, D.; Luo, Q.; Ritchie, B.W. Afraid to travel after COVID-19? Self-protection, coping and resilience against pandemic ‘travel fear’. Tour. Manag. 2021, 83, 104261. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, S.; Yoon, A.; Kim, M.J.; Yoon, J.H. What influences tourist behaviors during and after the COVID-19 pandemic? Focusing on theories of risk, coping, and resilience. J. Hosp. Tour. Manag. 2022, 50, 355–365. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, H.; Deng, F. How to influence rural tourism intention by risk knowledge during COVID-19 containment in China: Mediating role of risk perception and attitude. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2020, 17, 3514. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fuchs, G.; Reichel, A. An exploratory inquiry into destination risk perceptions and risk reduction strategies of first time vs. repeat visitors to a highly volatile destination. Tour. Manag. 2011, 32, 266–276. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lo, A.S.; Cheung, C.; Law, R. Hongkong residents’ adoption of risk reduction strategies in leisure travel. J. Travel Tour. 2011, 28, 240–260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ajzen, I.; Driver, B.L. Application of the theory of planned behavior to leisure choice. J. Leis. Res. 1992, 24, 207–224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elder, D. Jeju Island Statistics: The Province in Numbers. Inside Jeju. Available online: https://insidejeju.com/planning/jeju-statistics-the-island-in-numbers/ (accessed on 3 November 2023).

- Hair, J.F.; Ringle, C.M.; Sarstedlt, M. Partial least squares structural equation modeling: Rigorous applications, better results and higher acceptance. Long Range Plan. 2013, 46, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fornell, C.; Larcker, D.F. Evaluating structural equation models with Unobservable variables and measurement error. J. Mark. Res. 1981, 18, 39–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chien, P.M.; Sharifpour, M.; Ritchie, B.W.; Watson, B. Travelers’ health risk perceptions and protective behavior: A psychological approach. J. Travel Res. 2017, 56, 744–759. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Choi, B.; Ahluwalia, R. Determinants of brand switching: The role of consumer inferences, brand commitment, and perceived risk. J. Appl. Soc. Psychol. 2013, 43, 981–991. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Loh, Z.; Hassan, S.H. Consumers’ attitudes, perceived risks and perceived benefits towards repurchase intention of food truck products. Br. Food J. 2022, 124, 1314–1332. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, Y.J. Relationships among environmental attitudes, risk perceptions, and coping behavior: A case study of four environmentally sensitive townships in Yunlin County, Taiwan. Sustainability 2018, 10, 2663. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, J.; Choe, Y.; Song, H. Brand behavioral intentions of a theme park in China: An application of brand experience. Sustainability 2020, 12, 4500. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Variables | Item | N | % |

|---|---|---|---|

| Gender | Male | 139 | 45.9 |

| Female | 164 | 54.1 | |

| Age | 20s | 75 | 24.8 |

| 30s | 98 | 32.3 | |

| 40s | 66 | 21.8 | |

| 50s | 36 | 11.9 | |

| 60s | 28 | 9.2 | |

| Monthly income (USD) | 1000 and less | 56 | 18.5 |

| 1001–2000 | 117 | 38.6 | |

| 2001–3000 | 91 | 30.0 | |

| Over 3000 | 39 | 12.9 | |

| Employment or professional status | Student | 21 | 6.9 |

| Office worker | 118 | 38.9 | |

| Professional | 46 | 15.2 | |

| Self-employed | 72 | 23.8 | |

| Other | 46 | 15.2 | |

| Number of food tourism experiences | 1–2 | 64 | 21.1 |

| 3–4 | 93 | 30.7 | |

| 5–6 | 87 | 28.7 | |

| More than 7 times | 59 | 19.5 | |

| Destination of food tourism | Domestic | 102 | 33.7 |

| International | 86 | 28.4 | |

| Both | 115 | 37.9 | |

| Accompany | Family members | 76 | 25.1 |

| Non-Family members | 198 | 65.3 | |

| Alone | 29 | 9.6 | |

| Total | 303 | 100 |

| Variables and Items | Factor Loading | Eigen Value | Variance Explained | Cronbach’s α |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Physical risk | 4.356 | 14.050 | 0.911 | |

| Potential health problems | 0.767 | |||

| Get sick from food | 0.766 | |||

| Possibility of contacting infectious diseases while dining | 0.746 | |||

| Possibility of man-made violent events | 0.714 | |||

| Possibility of public security incidents | 0.644 | |||

| May be sick on the trip (e.g., pneumonia) | 0.625 | |||

| Communication risk | ||||

| The inconvenience of using other languages | 0.873 | 2.941 | 9.488 | 0.861 |

| Difficulty in ordering food | 0.841 | |||

| Difficulty in understanding the menu | 0.829 | |||

| Communication problems while dining | 0.719 | |||

| Food performance risk | ||||

| Food arrangements are not as expected | 0.886 | 2.675 | 8.630 | 0.785 |

| Food taste is unsatisfactory | 0.880 | |||

| Food tourism is unable to meet the requirements of cultural experiences | 0.876 | |||

| Attitude | ||||

| I like to visit Jeju for food tourism | 0.816 | 2.437 | 7.862 | 0.744 |

| happy to visit Jeju for food tourism | 0.755 | |||

| Visiting Jeju for food tourism is worthwhile | 0.668 | |||

| Visiting Jeju for food tourism will have good outcomes | 0.592 | |||

| Subjective norm | ||||

| My family thinks positively about my trip to Jeju for food tourism | 0.733 | 2.382 | 7.685 | 0.893 |

| My friends think positively about my trip to Jeju for food tourism | 0.717 | |||

| My family will want me to visit Jeju for food tourism | 0.709 | |||

| My friends will want me to visit Jeju for food tourism | 0.525 | |||

| Perceived behavioral control | ||||

| I can visit Jeju for food tourism whenever I want | 0.742 | 2.284 | 7.366 | 0.854 |

| I am financially able to afford to visit Jeju for food tourism | 0.645 | |||

| I have enough time to visit Jeju for food tourism | 0.640 | |||

| I can easily find the information about visiting Jeju for food tourism | 0.618 | |||

| Coping behavior | ||||

| Search for information about food tourism in Jeju | 0.798 | 2.164 | 6.982 | 0.743 |

| Choose a famous restaurant | 0.747 | |||

| Learn to speak the language for a simple conversation | 0.661 | |||

| Intention to travel | ||||

| Will make an effort | 0.779 | 1.994 | 6.442 | 0.713 |

| Intend to visit | 0.771 | |||

| Want to visit | 0.577 | |||

| Variables and Items | Standardized Loading | S.E. | C.R. | CR | AVE |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Physical risk | |||||

| Potential health problems | 0.792 | ||||

| Get sick from food | 0.756 | 0.067 | 13.974 | 0.902 | 0.605 |

| Possibility of contacting infectious diseases while dining | 0.634 | 0.074 | 11.320 | ||

| Possibility of man-made violent events | 0.802 | 0.070 | 15.052 | ||

| Possibility of public security incidents | 0.788 | 0.073 | 14.723 | ||

| May be sick on the trip (e.g., pneumonia) | 0.791 | 0.074 | 12.538 | ||

| Communication risk | |||||

| The inconvenience of using other languages | 0.726 | ||||

| Difficulty in ordering food | 0.706 | 0.128 | 10.250 | 0.883 | 0.626 |

| Difficulty in understanding the menu | 0.902 | 0.124 | 12.061 | ||

| Communication problems while dining | 0.886 | 0.131 | 11.979 | ||

| Food performance risk | |||||

| Food arrangements are not as expected | 0.857 | ||||

| Food taste is unsatisfactory | 0.870 | 0.058 | 18.054 | 0.894 | 0.737 |

| Food tourism is unable to meet the requirements of cultural experiences | 0.848 | 0.057 | 17.580 | ||

| Attitude | |||||

| I like to visit Jeju for food tourism | 0.735 | ||||

| happy to visit Jeju for food tourism | 0.809 | 0.157 | 8.516 | 0.873 | 0.632 |

| Visiting Jeju for food tourism is worthwhile | 0.814 | 0.116 | 7.521 | ||

| Visiting Jeju for food tourism will give me good outcomes | 0.819 | 0.127 | 8.190 | ||

| Subjective norm | |||||

| My family thinks positively about my trip to Jeju for food tourism | 0.801 | ||||

| My friends think positively about my trip to Jeju for food tourism | 0.777 | 0.086 | 12.071 | 0.858 | 0.610 |

| My family will want me to visit Jeju for food tourism | 0.780 | 0.086 | 12.120 | ||

| My friends will want me to visit Jeju for food tourism | 0.743 | 0.087 | 11.616 | ||

| Perceived behavioral control | |||||

| I can visit Jeju for food tourism whenever I want | 0.835 | ||||

| I am financially able to afford to visit Jeju for food tourism | 0.807 | 0.103 | 8.723 | 0.886 | 0.660 |

| I have enough time to visit Jeju for food tourism | 0.862 | 0.111 | 10.320 | ||

| I can easily find the information about visiting Jeju for food tourism | 0.744 | 0.097 | 10.164 | ||

| Coping behavior | |||||

| Search for information about food tourism in Jeju | 0.845 | ||||

| Choose a famous restaurant | 0.759 | 0.090 | 10.278 | 0.821 | 0.605 |

| Learn to speak the language for a simple conversation | 0.725 | 0.076 | 9.809 | ||

| Intention to travel | |||||

| Will make an effort | 0.879 | ||||

| Intend to visit | 0.730 | 0.120 | 8.460 | 0.830 | 0.621 |

| Want to visit | 0.746 | 0.146 | 8.518 | ||

| χ2 = 737.658, df = 406, CMIN/DF = 1.817, GFI = 0.961 AGFI = 0.930, NFI = 0.951, CFI = 0.926, RMR = 0.034, RMSEA = 0.052 | |||||

| Variable | PR | CR | FP | AT | SN | PBC | CB | BI |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| PR | 0.737 | |||||||

| CR | 0.145 (0.021) * | 0.605 | ||||||

| FP | 0.102 (0.010) * | 0.518 (0.268) *** | 0.621 | |||||

| AT | −0.182 (0.033) * | −0.542 (0.294) *** | −0.482 (0.232) *** | 0.660 | ||||

| SN | −0.281 (0.079) *** | −0.594 (0.353) *** | −0.623 (0.388) *** | 0.693 (0.480) *** | 0.601 | |||

| PBC | −0.152 (0.023) * | −0.493 (0.243) *** | −0.479 (0.229) *** | 0.418 (0.175) *** | 0.535 (0.286) *** | 0.632 | ||

| CB | 0.395 (0.156) *** | 0.526 (0.277) *** | 0.468 (0.219) *** | 0.768 (0.590) *** | 0.706 (0.498) *** | 0.453 (0.205) *** | 0.605 | |

| BI | −0.246 (0.021) *** | −0.210 (0.044) ** | −0.309 (0.095) *** | 0.349 (0.122) *** | 0.372 (0.138) *** | 0.344 (0.118) *** | 0.359 (0.129) *** | 0.626 |

| Hypothesis | Path | Standardized Path Coefficients | t-Value | Results |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| H1 | PHY → ATT | −0.497 | −5.497 *** | Supported |

| H2 | PHY → SN | −0.261 | −4.760 *** | Supported |

| H3 | PHY → PBC | −0.362 | −4.177 *** | Supported |

| H4 | COM → ATT | −0.360 | −3.973 *** | Supported |

| H5 | COM → SN | −0.115 | −1.847 | Rejected |

| H6 | COM → PBC | −0.356 | −3.670 *** | Supported |

| H7 | FP → ATT | −0.329 | −4.286 *** | Supported |

| H8 | FP → SN | −0.186 | −3.112 *** | Supported |

| H9 | FP → PBC | 0.064 | −1.105 | Rejected |

| H10 | ATT → CB | 0.536 | 6.898 *** | Supported |

| H11 | SN → CB | 0.356 | 5.222 *** | Supported |

| H12 | PBC → CB | 0.309 | 3.384 *** | Supported |

| H13 | CB → BI | 0.337 | 5.523 *** | Supported |

| χ2 = 806.301, df = 418, CMIN/DF = 1.929, GFI = 0.948, AGFI = 0.919, NFI = 0.937, CFI = 0.918, RMR = 0.040, RMSEA = 0.056 | ||||

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

An, S.; Choi, J.; Eck, T.; Yim, H. Perceived Risk and Food Tourism: Pursuing Sustainable Food Tourism Experiences. Sustainability 2024, 16, 13. https://doi.org/10.3390/su16010013

An S, Choi J, Eck T, Yim H. Perceived Risk and Food Tourism: Pursuing Sustainable Food Tourism Experiences. Sustainability. 2024; 16(1):13. https://doi.org/10.3390/su16010013

Chicago/Turabian StyleAn, Soyoung, Jinkyung Choi, Thomas Eck, and Huirang Yim. 2024. "Perceived Risk and Food Tourism: Pursuing Sustainable Food Tourism Experiences" Sustainability 16, no. 1: 13. https://doi.org/10.3390/su16010013

APA StyleAn, S., Choi, J., Eck, T., & Yim, H. (2024). Perceived Risk and Food Tourism: Pursuing Sustainable Food Tourism Experiences. Sustainability, 16(1), 13. https://doi.org/10.3390/su16010013