Let’s Be Vegan? Antecedents and Consequences of Involvement with Vegan Products: Vegan vs. Non-Vegan

Abstract

:1. Introduction

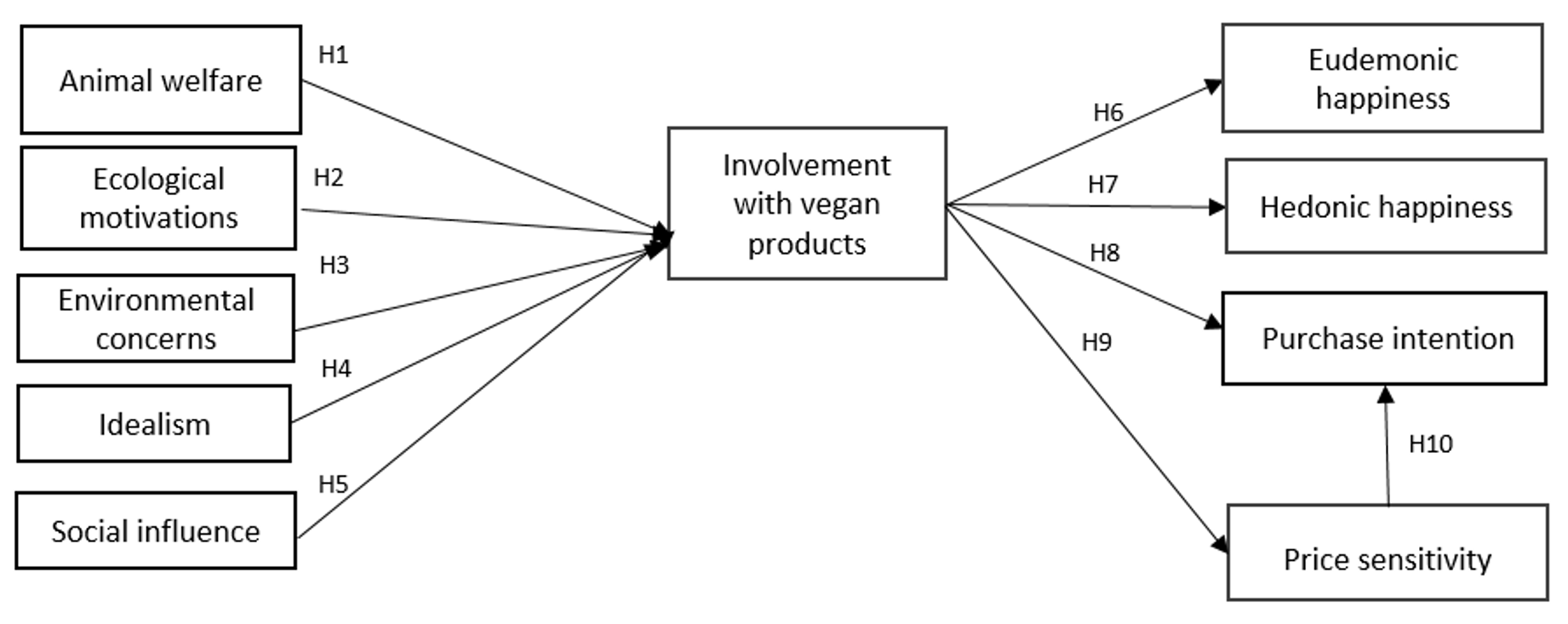

2. Conceptual Development and Research Hypotheses

2.1. Veganism

2.1.1. Self-Determination Theory and Veganism

2.1.2. Vegans and Non-Vegans

2.1.3. Involvement with Vegan Products

2.2. Drivers of Involvement with Vegan Products

2.2.1. Animal Welfare

2.2.2. Ecological Motivation

2.2.3. Environmental Concerns

2.2.4. Idealism

2.2.5. Social Influence

2.3. Understanding the Consequences of Involvement with Vegan Products

2.3.1. Eudemonic and Hedonic Happiness

2.3.2. Purchase Intention

2.3.3. Price Sensitivity

3. Method

4. Sample and Data Collection

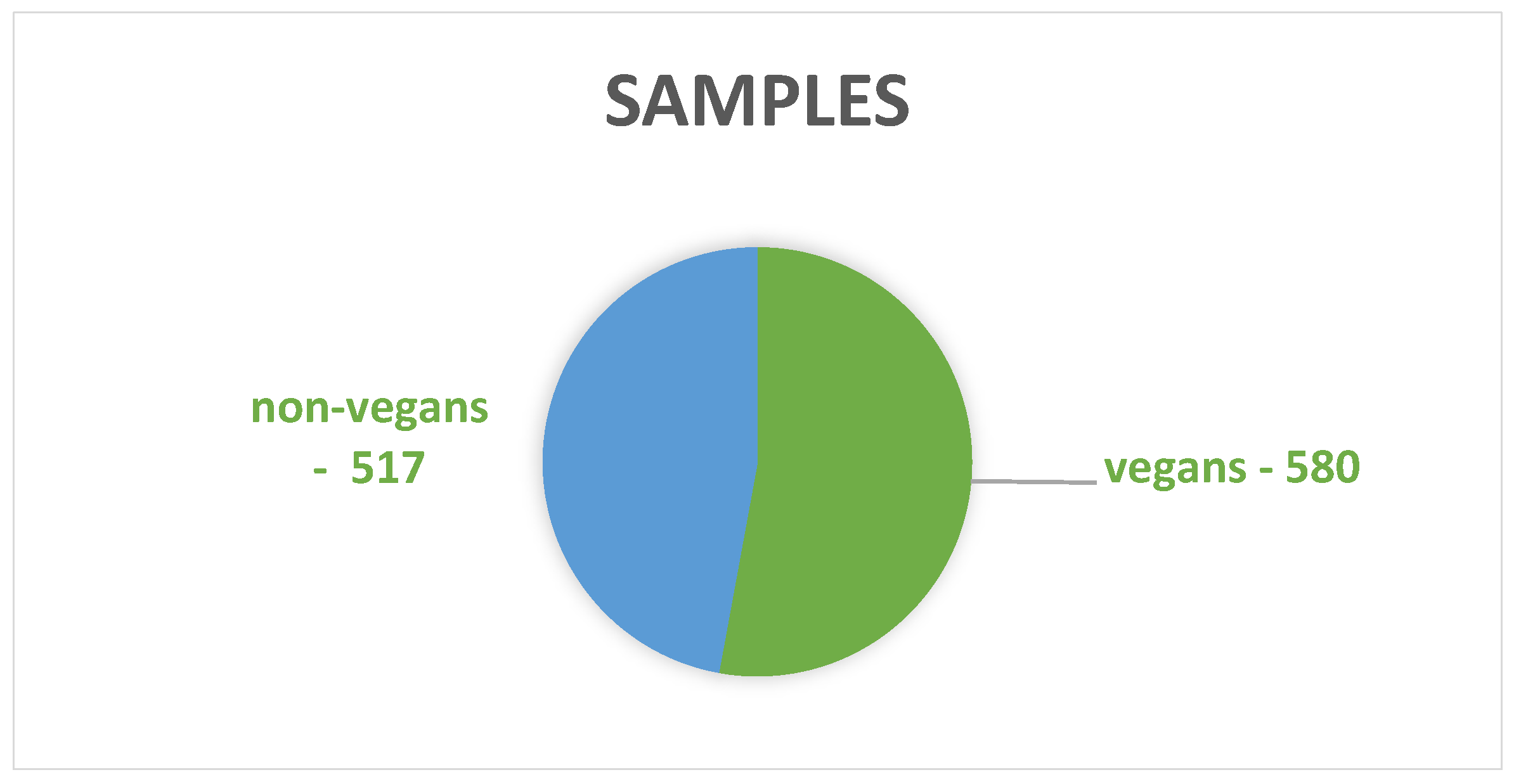

4.1. Sampling

4.2. Measures

4.3. Common Method Bias

5. Findings and Discussion

5.1. Determinants of Involvement with Vegan Products

Consequences of Involvement with Vegan Products

5.2. Price Sensitivity and Purchase Intention

6. Contributions and Limitations

6.1. Theoretical Contributions

- (1)

- Firstly, comparing ideology and individual features as antecedents of involvement with vegan products, providing the basis for further investigations on the drivers and motivations of veganism;

- (2)

- The second contribution concerns the impact on well-being. The investigation of a lifestyle or, at least, consumption that provides happiness and well-being, will bring a better comprehension on the future of veganism and on the growth of this market;

- (3)

- The third contribution is related to impact on price sensitivity, showing that prices are less relevant and that customers are willing to pay more for vegan products;

- (4)

- The fourth compares vegans and non-vegans concerning the involvement with vegan products, showing how social issues may lead to a greater involvement with vegan products that non-vegans may buy less of currently but are willing to pay even more for.

6.2. Practical Contributions

6.3. Limitations and Future Research Directions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- The Vegan Society (n.d.). The Veganuary Campaign. Available online: https://www.vegansociety.com/take-action/campaigns/veganuary-2021 (accessed on 25 January 2021).

- Piia, J.; Markus, V.; Mari, N. The Oxford Handbook of Political Consumerism; Boström, M., Micheletti, M., Oosterveer, P., Eds.; The Oxford University Press: Oxford, UK, 2019; pp. 157–179. [Google Scholar]

- Fuentes, C.; Fuentes, M. Making alternative proteins edible: Market devices and the qualification of plant-based substitutes. Consum. Soc. 2023, 2, 200–219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harmon, J. Bacterial Cellulose Product Development: Comparing Leather and Leather Alternatives. In Proceedings of the International Textile and Apparel Association Annual Conference Proceedings, Virtual, 18–20 November 2020; p. 77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wrenn, C. Black Veganism and the Animality Politic. Soc. Anim. 2019, 27, 127–131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dos Santos, R.C.; de Brito Silva, M.J.; da Costa, M.F.; Batista, K. Go vegan! digital influence and social media use in the purchase intention of vegan products in the cosmetics industry. Soc. Netw. Anal. Min. 2023, 13, 49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wescombe, N.J. Communicating Veganism: Evolving Theoretical Challenges to Mainstreaming Ideas. Stud. Media Commun. 2019, 7, 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Innova Market Insights (n.d.). Innova Market Insights: The Plant-Based Revolution Marches on. Available online: https://www.foodingredientsfirst.com/news/innova-market-insights-the-plant-based-revolution-marches-on.html (accessed on 2 June 2022).

- The Economist (n.d.). 2019 the Year of Veganism. Available online: https://www.economist.com/graphic-detail/2020/01/29/interest-in-veganism-is-surging (accessed on 2 January 2020).

- Dyett, P.A.; Sabaté, J.; Haddad, E.; Rajaram, S.; Shavlik, D. Vegan lifestyle behaviors. An exploration of congruence with health-related beliefs and assessed health indices. Appetite 2013, 67, 119–124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Goksen, G.; Altaf, Q.S.; Farooq, S.; Bashir, I.; Capozzi, V.; Guruk, M.; Bavaro, S.L.; Sarangi, P.K. A glimpse into plant-based fermented products alternative to animal based products: Formulation, processing, health benefits. Food Res. Int. 2023, 173, 113344. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Janssen, M.; Busch, C.; Rödiger, M.; Hamm, U. Motives of consumers following a vegan diet and their attitudes towards animal agriculture. Appetite 2016, 105, 643–651. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kerschke-Risch, P. Vegane Ernährung: Motive, Einstieg und Dauer—Erste Ergebnisse Einer Quantitativen Sozialwissenschaftlichen Studie. Obtido 16 de Agosto de 2018. 2015. Available online: https://www.ernaehrungs-umschau.de/print-artikel/11-06-2015-vegane-ernaehrung-motive-einstieg-und-dauer-erste-ergebnisse-einer-quantitativen-sozialwissenschaftlichen-studie/ (accessed on 24 April 2018).

- Radnitz, C.; Beezhold, B.; DiMatteo, J. Investigation of lifestyle choices of individuals following a vegan diet for health and ethical reasons. Appetite 2015, 90, 31–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barrett, J.; Raskoff, S.Z. Ethical veganism and free riding. J. Ethics Soc. Phil. 2023, 24, 184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ciocchetti, C. Veganism and living well. J. Agric. Environ. Ethics 2012, 25, 405–417. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Novoselova, T.A.; van der Lans, I.A.; Meuwissen, M.P.; Huirne, R. Consumer acceptance of GM applications in the pork production chain: A choice modelling approach. In Proceedings of the 2005 International Congress, Copenhagen, Denmark, 23–27 August 2005; No. 24527; European Association of Agricultural Economists: London, UK, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Carlsson-Kanyama, A.; González, A.D. Potential contributions of food consumption patterns to climate change. Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 2009, 89, 1704S–1709S. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dixon, K.A.; Michelsen, M.K.; Carpenter, C.L. Modern diets and the health of our planet: An investigation into the environmental impacts of food choices. Nutrients 2023, 15, 692. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- OIE. Introduction to the recommendations for animal welfare. In Terrestrial Animal Health Code; World Organisation for Animal Health: Paris, France, 1965; pp. 1–2. Available online: http://www.oie.int/fileadmin/Home/eng/Health_standards/tahc/current/chapitre_aw_introduction.pdf (accessed on 20 February 2021).

- Olsson, I.; Silva, S.; Townend, D.; Sandøe, P. Protecting Animals and Enabling Research in the European Union: An Overview of Development and Implementation of Directive. ILAR J. 2010, 57, 347–357. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shani, A.; Pizam, A. Towards an ethical framework for animal-based attractions. Int. J. Contemp. Hosp. Manag. M 2008, 20, 679–693. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Petrie, C. Live Export: A Chronology. Parliamentary Library: Canberra Australia. 2016. Available online: https://parlinfo.aph.gov.au/parlInfo/download/library/prspub/4700032/upload_binary/4700032.pdf (accessed on 2 May 2019).

- Byrd, E.; Lee, J.G.; Widmar, N.J. Perceptions of Hunting and Hunters by U.S. Respondents. Animals 2017, 4, 7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peta UK Annual Review. 2018. Available online: https://www.peta.org.uk/wp-content/uploads/2019/01/ANNUAL-REVIEW-2018_UK_FINAL_72_WEB.pdf (accessed on 2 May 2019).

- Greenebaum, J.B. Veganism, identity and the quest for authenticity. Food Cult. Soc. 2012, 15, 129–144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grauel, J. Being Authentic or Being Responsible? Food Consumption, Morality and the Presentation of Self. J. Consum. Cult. 2016, 16, 852–869. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Belasco, W.J. Appetite for Change: How the Counterculture Took on the Food Industry; Cornell University Press: Ithaca, Greece, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Sirieix, L.; de Lanauze, G.S.; Dyen, M.; Balbo, L.; Suarez, E. The role of communities in vegetarian and vegan identity construction. J. Retail. Consum. Serv. 2023, 75, 103470. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tunçay Son, G.Y. Vegan and Vegetarianism in the Frame of Bioethics. Ankara: Institute of Social Sciences, Ankara Üniversitesi. 2016. Available online: http://acikarsiv.ankara.edu.tr/browse/29850/yasemin_tuncay_son.pdf (accessed on 15 March 2021).

- DaSilva, G.; Hecquet, J.; King, K. Exploring veganism through serious leisure and liquid modernity. Ann. Leis. Res. 2019, 23, 627–644. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Earle, M.; Hodson, G. What’s your beef with vegetarians? Predicting anti-vegetarian prejudice from pro-beef attitudes across cultures. Personal. Individ. Differ. 2017, 119, 52–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bagci, S.C.; Olgun, S. A social identity needs perspective to Veg*nism: Associations between perceived discrimination and well-being among Veg*ns in Turkey. Appetite 2019, 143, 104441. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rosenfeld, D.L.B. The psychology of vegetarianism: Recent advances and future directions. Appetite 2018, 131, 125–138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pfeiler, T.M.; Egloff, B. Examining the “Veggie” personality: Results from a representative German sample. Appetite 2018, 20, 246–255. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Costa, I.; Gill, P.R.; Morda, R.; Ali, L. “More than a diet”: A qualitative investigation of young vegan Women’s relationship to food. Appetite 2019, 143, 104418. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rex, E.; Baumann, H. Beyond ecolabels: What green marketing can learn from conventional marketing? J. Clean. Prod. 2007, 15, 567–576. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghali, Z. The Antecedents of the Consumer Purchase Intention: Sensitivity to Price and Involvement in Organic Product: Moderating Role of Product Regional Identity. Trends Food Sci. Technol. 2019, 90, 175–179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mintel GNPD. 2016. Available online: https://www.mintel.com/press-centre/food-and-drink/mintel-identifies-global-food-and-drink-trends-for-2016 (accessed on 3 June 2019).

- Hargreaves, S.M.; Rosenfeld, D.L.; Moreira AV, B.; Zandonadi, R.P. Plant-based and vegetarian diets: An overview and definition of these dietary patterns. Eur. J. Nutr. 2023, 62, 1109–1121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Doyle, J. Celebrity vegans and the life styling of ethical consumption. Environ. Commun. 2016, 10, 777–790. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cherry, E. I Was a Teenage Vegan: Motivation and Maintenance of Lifestyle Movements. Sociol. Inq. 2015, 85, 55–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alnasser, A.; Alomran, N. The motivations and practices of vegetarian and vegan Saudis. Sci. Rep. 2023, 13, 9742. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beverland, M.B.; Wahl, K.; Groot, J. Sustaining a Sustainable Diet: Vegans and their Social Eating Practices. Marketing as Provisioning Technology: Integrating Perspectives on Solutions for Sustainability, Prosperity, and Social Justice. In Proceedings of the 40th Annual Macro Marketing Conference, Prosperity, Chicago, IL, USA, 25–28 June 2015; pp. 145–146. [Google Scholar]

- Mortara, A. ‘Techno mums’ Motivations towards Vegetarian and Vegan Lifestyles. Ital. Sociol. Rev. 2013, 3, 184–192. [Google Scholar]

- Twine, R. Materially Constituting a Sustainable Food Transition: The Case of Vegan Eating Practice. Sociology 2017, 52, 166–181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moutinho, L.; Dionísio, P.; Leal, C. Surf tribal behaviour: A sports marketing application. Mark. Intell. Plan. 2007, 25, 668–690. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brignall, T.W.; Van Valey, T.L. An Online Community as a New Tribalism: The World of Warcraft. In Proceedings of the 2007 40th Annual Hawaii International Conference on System Sciences (HICSS’07), Waikoloa, HI, USA, 3–6 January 2007; p. 179b. [Google Scholar]

- Andersen, J.G.; Tobiasen, M. Who are these political consumers anyway? Survey evidence from Denmark. In Politics, Products and Markets. Exploring Political Consumerism. Past and Present; Micheletti, M., Ed.; Transaction Publishers: London, UK, 2004; pp. 203–222. [Google Scholar]

- Stolle, D.; Micheletti, M. Political Consumerism: Global Responsibility in Action; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Van Boven, L.; Gilovich, T. The Social Costs of Materialism: The Existence and Implications of Experiential Versus Materialistic Stereotypes; Unpublished manuscript; University of Colorado: Denver, CO, USA, 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Kalte, D. Political Veganism: An Empirical Analysis of Vegans’ Motives, Aims, and Political Engagement. Political Stud. 2020, 69, 814–883. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rosenfeld, D.L.; Burrow, A. Vegetarian on purpose: Understanding the motivations of plant-based dieters. Appetite 2017, 116, 456–463. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Beardsworth, A.D.; Keil, E.T. Contemporary Vegetarianism in the U.K.: Challenge and Incorporation? Appetite 1993, 20, 229–234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Francione, G.L.; Charlton, A. Animal Rights: The Abolitionist Approach; Exempla Press: Logan, UT, USA, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Greenebaum, J. Vegans of color: Managing visible and invisible stigmas. Food Cult. Soc. 2018, 21, 680–697. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hsu, C.L.; Chen, M.C. Explaining consumer attitudes and purchase intentions toward organic food: Contributions from regulatory fit and consumer characteristics. Food Qual. Prefer. 2014, 35, 6–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Popa, M.E.; Mitelut, A.C.; Popa, E.E.; Stan, A.; Popa, V.L. Organic foods contribution to nutritional quality and value. Trends Food Sci. Technol. 2019, 84, 15–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rahman, I. The interplay of product involvement and sustainable consumption: An empirical analysis of behavioral intentions related to green hotels, organic wines and green cars. Sustain. Dev. 2018, 26, 399–414. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ryan, R.M.; Deci, E.L. On happiness and human potentials: A review of research on hedonic and eudaimonic well-being. Annu. Rev. Psychol. 2001, 52, 41–166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Garg, R.; Agarwal, P.; Singh, A.P.; Magan, R.; Gupta, P. The Lifestyle Habits and Well-being of Doctors through a Lens of Happiness Score on an Indian Dataset. J. South Asian Fed. Obstet. Gynaecol. 2022, 14, 730–733. [Google Scholar]

- Khan, S.; Abbas, M. Interactive effects of consumers’ ethical beliefs and authenticity on ethical consumption and pro-environmental behaviors. J. Retail. Consum. Serv. 2023, 71, 103226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gilal, F.G.; Zhang, J.; Paul, J.; Gilal, N.G. The role of self-determination theory in marketing science: An integrative review and agenda for research. Eur. Manag. J. 2019, 37, 29–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghvanidze, S.; Velikova, N.; Dodd, T.H.; Wilna, O.T. Consumers’ environmental and ethical consciousness and the use of the related food products information: The role of perceived consumer effectiveness. Appetite 2016, 107, 311–322. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Maeda-Yamamoto, M. Development of functional agricultural products and use of a new health claim system in Japan. Trends Food Sci. Technol. 2017, 69, 324–332. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Laureti, T.; Benedetti, I. Exploring pro-environmental food purchasing behaviour: An empirical analysis of Italian consumers. J. Clean. Prod. 2018, 172, 3367–3378. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carrington, M.J.; Neville, B.A.; Whitwell, G.J. Lost in translation: Explorethical consumer intention behavior gap. J. Bus. Res. 2014, 67, 2759–2767. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moslehpour, M.; Yin Chau, K.; Du, L.; Qiu, R.; Lin, C.Y.; Batbayar, B. Predictors of green purchase intention toward eco-innovation and green products: Evidence from Taiwan. Econ. Res.-Ekon. Istraž. 2023, 36, 2121934. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Richins, M.L.; Bloch, P.H. After the New wears off: The Temporal Context of Product Involvement. J. Consum. Res. 1986, 13, 280. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Celsi, R.L.; Olson, J.C. The role of involvement in attention and comprehension processes. J. Consum. Res. 1988, 15, 210–224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tarkiainen, A.; Sundqvist, S. Product involvement in organic food consumption: Does ideology meet practice? Psychol. Mark. 2009, 26, 844–863. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baldini, A.P.; Canniatti Ponchio, M. Avaliação do processo de compra de alto envolvimento: Aplicação do Consumer Styles Inventory ao mercado brasileiro de veículos comerciais leves. Rev. Adm. UNIMEP 2017, 16, 2. [Google Scholar]

- Zhou, Y.; Huang, W. The influence of network anchor traits on shopping intentions in a live streaming marketing context: The mediating role of value perception and the moderating role of consumer involvement. Econ. Anal. Policy 2023, 78, 332–342. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, S.C.; Keil, M. The moderating effects of product involvement on escalation behavior. J. Comput. Inf. Syst. 2019, 59, 218–232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, S.; Lee, S.K.; Jeong, J.; Moon, J. The effect of agritourism experience on consumers’ future food purchase patterns. Tour. Manag. 2019, 70, 144–152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rokonuzzaman, M.; Harun, A.; Al-Emran, M.; Prybutok, V.R. An investigation into the link between consumer’s product involvement and store loyalty: The roles of hopping value goals and information search as the mediating factors. J. Retail. Consum. Serv. 2020, 52, 101933. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jeseviciute-Ufartiene, L. Consumer involvement in the purchasing process: Consciousness of the choice. Econ. Cult. 2019, 16, 126–136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Strubel, J.; Petrie, T.A. The clothes make the man: The relation of sociocultural factors and sexual orientation to appearance and product involvement. J. Retail. Consum. Serv. 2016, 33, 1–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ares, G.; Besio, M.; Gimenez, A.; Deliza, R. Relationship between involvement and functional milk desserts intention to purchase. Influence on attitude towards packaging characteristics. Appetite 2010, 55, 298–304. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, J.U.; Kim, W.J.; Park, S.C. Consumer perceptions on web advertisements and motivation factors to purchase in the online shopping. Comput. Hum. Behav. 2010, 26, 1208–1222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Montandon, A.C.; Ogonowski, A.; Botha, E. Product Involvement and the Relative Importance of Health Endorsements. J. Food Prod. Mark. 2017, 23, 649–667. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hoyer, W.D.; MacInnis, D.J. Consumer Behaviour, Houghton Mifflin Company, 2nd ed.; Houghton Mifflin Company: Boston, MA, USA, 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Caro, A.; Mazzon, J.A.; Caemmerer, B.; Wessling, M. Inovatividade, envolvimento, atitude e experiência na adoção da compra on-line. RAE-Rev. Adm. Empresas 2011, 51, 568–584. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- EU Platform on Animal Welfare. Animal Health and Welfare DG for Health and Food Safety. 2019. Available online: https://rpawe.oie.int/fileadmin/upload-activities/2019_awfp/2019_awfp_eng/16_-s.ralchev-_eu_platform_on_animal_welfare.pdf (accessed on 22 June 2019).

- European Commission. Attitudes of Europeans towards Animal Welfare Report; Publications Office of the EU: Brussels, Belgium, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Duncan, I.J.H. Poultry welfare: Science or subjectivity? Br. Poult. Sci. 2002, 43, 643–652. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- McDowall, S.; Hazel, S.J.; Chittleborough, C.; Hamilton-Bruce, A.; Stuckey, R.; Howell, T.J. The Impact of the Social Determinants of Human Health on Companion Animal Welfare. Animals 2023, 13, 1113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Padilla Bravo, C.; Cordts, A.; Schulze, B.; Spiller, A. Assessing determinants of organic food consumption using data from the German National Nutrition Survey II. Food Qual. Prefer. 2013, 28, 1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zanoli, R.; Scarpa, R.; Napolitano, F.; Piasentier, E.; Naspetti, S.; Bruschi, V. Organic label as an identifier of environmentally related quality: A consumer choice experiment on beef in Italy. Renew. Agric. Food Syst. 2013, 28, 70–79. Available online: https://www.jstor.org/stable/26324747 (accessed on 18 May 2021). [CrossRef]

- Clark, B.; Stewart, G.B.; Panzone, L.A.; Kyriazakis, I.; Frewer, L.J. A systematic review of public attitudes, perceptions and behaviors towards production diseases associated with farm animal welfare. J. Agric. Environ. Ethics 2016, 29, 455–478. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kazez, J. The taste question in animal ethics. J. Appl. Philos. 2017, 35, 661–674. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hewson, C.J. What is animal welfare? Common definitions and their practical consequences. Can. Vet. J. 2003, 44, 496–499. [Google Scholar]

- Zapf, R.; Schultheiß, U.; Archilles, W.; Schrader, L.; Knierim, U.; Herrmann, H.-J.; Brinkmann, J.; Winckler, C. Tierschutzindikatoren. Vorschläge für die Betriebliche Eigenkontrolle. KTBL Schrift 507; Kuratorium für Technik und Bauwesen in der Landwirtschaft e.V. (KTBL): Darmstadt, Germany, 2015; ISBN 978-3-945088-06-7. [Google Scholar]

- Cooper, L. A New Veganism: How Climate Change Has Created More Vegans. Granite Aberd. Univ. Postgrad. Interdiscip. J. 2018, 2, 16–24. [Google Scholar]

- Campbell, L.M.; Smith, C. What Makes Them Pay? Values of Volunteer Tourists Working for Sea Turtle Conservation. Environ. Manag. 2006, 38, 84–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kaplan Mintz, K.; Arazy, O.; Malkinson, D. Multiple forms of engagement and motivation in ecological citizen science. Environ. Educ. Res. 2023, 29, 27–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Faria, C.; Paez, E. Animals in Need: The Problem of Wild Animal Suffering and Intervention in Nature. Relat. Beyond Anthr. 2015, 3, 7–13. [Google Scholar]

- Harper, G.C.; Makatouni, A. Consumer perception of organic food production and farm animal welfare. Br. Food J. 2002, 104, 287–299. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Şimşekoğlu, Ö.; Nordfjærn, T.; Rundmo, T. The role of attitudes, transport priorities, and car use habit for travel mode use and intentions to use public transportation in an urban Norwegian public. Transp. Policy 2015, 42, 113–120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, P.; Liu, Q.; Qi, Y. Factors influencing sustainable consumption behaviors: A survey of the rural residents in China. J. Clean. Prod. 2014, 63, 152–165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ruby, M.B.; Heine, S.J.; Kamble, S.; Cheng, T.K.; Waddar, M. Compassion and contamination. Cultural differences in vegetarianism. Appetite 2013, 71, 340–348. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Majláth, M. What are the Main Psychographic Differences between Persons Behave in an Environmentally Friendly Way and Those Who Do Not? In Proceedings of the MEB 2008—6th International Conference on Management, Enterprise and Benchmarking, Budapest, Hungary, 30–31 May 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Franzen, A.; Meyer, R. Environmental attitudes in cross-national perspective: A multilevel analysis of the ISSP 1993 and 2000. Eur. Socio Rev. 2010, 26, 219–234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dagher, G.K.; Itani, O. Factors influencing green purchasing behavior: Empirical evidence from the Lebanese consumers. J. Consum. Behav. 2014, 13, 188–195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tobler, C.; Visschers VH, M.; Siegrist, M. Eating green. Consumers’ willingness to adopt ecological food consumption behaviors. Appetite 2011, 57, 674–682. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rothgerber, H. A meaty matter. Pet diet and the vegetarian’s dilemma. Appetite 2013, 134, 76–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cova, B. Community and consumption: Towards a definition of the ‘linking value’ in products and services. Eur. J. Mark. 1997, 31, 297–316. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jabar, F.A. Sheikhs and Ideologues: Deconstruction and Reconstruction of Tribes under the Patrimonial Totalitarianism in Iraq, 1968–1998. In Tribes and Power: Nationalism and Ethnicity in the Middle East; Jabar, F.A., Dawod, H., Eds.; Saqi: London, UK, 2003; pp. 69–109. [Google Scholar]

- Charrad, M. Central and Local Patrimonialism: State-Building in KinBased Societies. Ann. Am. Acad. Political Soc. Sci. 2011, 636, 49–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cruz, S.M. The relationships of political ideology and party affiliation with environmental concern: A meta-analysis. J. Environ. Psychol. 2017, 53, 81–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chao, C.M.; Yu, T.K.; Yu, T.Y. Understanding the factors influencing recycling behavior in college students: The role of interpersonal altruism and environmental concern. Int. J. Sustain. High. Educ. 2023, 24, 969–985. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chan, R.Y.K.; Lau, L.B.Y. The Effectiveness of Environmental Claims among Chinese Consumers: Influences of Claim Type, Country Disposition and Ecocentric Orientation. J. Mark. Manag. 2004, 20, 273–319. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Takács-Sánta, A. Barriers to environmental concern. Res. Hum. Ecol. 2007, 14, 26–38. [Google Scholar]

- Shannon, M.C.; Manata, B. Measurement of Environmental Concern: A Review and Analysis. Front. Psychol. 2020, 11, 363. [Google Scholar]

- Dietz, T.; Fitzgerald, A.; Shwom, R. Environmental values. Ann. Rev. Environ. Res. 2005, 30, 335–372. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bamberg, S. How does environmental concern influence specific environmentally related behaviors? A new answer to an old question. J. Environ. Psychol. 2003, 23, 21–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Greaves, M.; Zibarras, L.D.; Stride, C. Using the theory of planned behavior to explore environmental behavioral intentions in the workplace. J. Environ. Psychol. 2013, 34, 109–120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pollard, M.; Kalafatis, S.P.; Tsogas, M.H.; East, R. Green marketing and Ajzen’s theory of planned behaviour: A cross-market examination. J. Consum. Mark. 1999, 16, 441–460. [Google Scholar]

- Arisal, İ.; Atalar, T. The Exploring Relationships between Environmental Concern, Collectivism and Ecological Purchase Intention. Proc. Soc. Behav. Sci. 2016, 235, 514–521. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wills, T. Social media as a research method. Commun. Res. Pract. 2016, 2, 7–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ruane, L.; Wallace, E. Brand tribalism and self-expressive brands: Social influences and brand outcomes. J. Prod. Brand Manag. 2015, 24, 333–348. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Z.; Zhao, C.; Yin, J.; Zhang, B. Purchasing intentions of Chinese citizens on new energy vehicles: How should one respond to current preferential policy? J. Clean. Prod. 2017, 161, 1000–1010. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lai, Q.; Thornton, A. The making of family values: Developmental idealism in Gansu, China. Soc. Sci. Res. 2015, 51, 174–188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thornton, S.J. History and Social Studies: A Question of Philosophy. Int. J. Soc. Educ. Off. J. Indiana Counc. Soc. Stud. 2005, 20, 1–5. [Google Scholar]

- Khan, Y.; Hameed, I.; Akram, U. What drives attitude, purchase intention and consumer buying behavior toward organic food? A self-determination theory and theory of planned behavior perspective. Br. Food J. 2023, 125, 2572–2587. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guyer, P.; Horstmann, R. “Idealism”, The Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy, Edward N. Zalta (ed.). 2019. Available online: https://plato.stanford.edu/archives/win2019/entries/idealism/ (accessed on 20 June 2020).

- Yifat, K.; Tyler, T.R. Tomorrow I’ll Be Me: The Effect of Time Perspective on the Activation of Idealistic Versus Pragmatic Selves. Organ. Behav. Hum. Decis. Process. 2007, 102, 193–211. [Google Scholar]

- Sarnowski, J. “Self-Preservation”: Identity, Idealism, and Pragmatism in Charles W. Chesnutt’s “The Wife of His Youth”. Pap. Lang. Lit. 2018, 54, 315-I. [Google Scholar]

- Forsyth, D.R.; O’Boyle, E.H.; McDaniel, M.A. East Meets West: A Meta-Analytic Investigation of Cultural Variations in Idealism and Relativism. J. Bus. Ethics 2008, 83, 813–833. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scholl, R. Motivating Ethical Behavior. Global Encyclopedia of Public Administration, Public Policy, and Governance; Farazmand, A., Ed.; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Marta JK, M.; Attia, A.; Singhapakdi, A.; Atteya, N. A Comparison of Ethical Perceptions and Moral Philosophies of American and Egyptian Business Students. Teach. Bus. Ethics 2003, 7, 1–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guyer, P.; Horstmann, R.-P. Idealism. Em E. N. Zalta (Ed.). The Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy (Summer 2018). Metaphysics Research Lab, Stanford University. 2018. Available online: https://plato.stanford.edu/archives/sum2018/entries/idealism/ (accessed on 20 May 2019).

- Varshneya, G.; Pandey, S.K.; Das, G. Impact of Social Influence and Green Consumption Values on Purchase Intention of Organic Clothing: A Study on Collectivist Developing Economy. Glob. Bus. Rev. 2017, 18, 478–492. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clark, C.; Brittany, L.; Bo, W.; Ditto, P. Tribalism is Human Nature. Curr. Dir. Psychol. Sci. 2019, 28, 587–592. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Simiyu, G.; Kariuki, V.W. Self-Image and Green Buying Intentions among University Students: The Role of Environmental Concern and Social Influence. J. Nonprofit Public Sect. Mark. 2023, 1–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, S.; Wang, B.; Liu, J. Group decision making under social influences based on information entropy. Granul. Comput. 2020, 5, 303–308. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goes, P.B.; Lin, M.; Yeung, C.-M.A. Popularity Effect in User-generated Content: Evidence from Online Product Reviews. Inf. Syst. Res. 2014, 25, 222–238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, K.; Stylianou, A.C.; Zheng, Y. Sources and impacts of social influence from online anonymous user reviews. Inf. Manag. 2018, 55, 1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Markowski, K.L.; Roxburgh, S. “If I became a vegan, my family and friends would hate me:” Anticipating vegan stigma as a barrier to plant-based diets. Appetite 2019, 135, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Friedkin, N.E. A Structural Theory of Social Influence; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 2006; Volume 13. [Google Scholar]

- Cunningham, S.A.; Vaquera, E.; Maturo, C.C.; Narayan, K.V. Is there evidence that friends influence body weight? A systematic review of empirical research. Soc. Sci. Med. 2012, 75, 1175–1183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Crano, W. Milestones in the psychological analysis of social influence. Group Dyn. Theory Res. Pract. 2000, 4, 68–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Venkatesh, V.; Morris, M.G.; Davis, F.D.; Davis, G.B. User acceptance of information technology: Toward a unified view. MIS Q. 2003, 27, 425–478. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peng, S.; Yang, A.; Cao, L.; Yu, S.; Xie, D. Social influence modeling using information theory in mobile social networks. Inf. Sci. 2017, 379, 146–159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pedersen, S.; Grønhøj, A.; Thøgersen, J. Following family or friends. Social norms in adolescent healthy eating. Appetite 2015, 86, 54–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Polivy, J.; Pliner, P. “She got more than me”. Social comparison and the social context of eating. Appetite 2015, 86, 88–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cialdini, R.; Trost, M. Social influence: Social norms, conformity and compliance. In The Handbook of Social Psychology; American Psychological Association: Worcester, MA, USA, 1998; Volume 2, pp. 151–192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Gavelle, E.D.; Fouillet, O.; Delarue, H.; Darcel, J.; Huneau, N.; Mariotti, J.F. Self-declared attitudes and beliefs regarding protein sources are a good prediction of the degree of transition to a low-meat diet in France. Appetite 2019, 142, 104345. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Canavari, M.; Olson, K.D. Organic Food: Consumers’ Choices and Farmers Opportunities; Springer Science + Business Media: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2007; pp. 171–181. [Google Scholar]

- Sheldon, K.M.; Kasser, T. Coherence and congruence: Two aspects of personality integration. J. Personal. Soc. Psychol. 1995, 68, 531–543. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kahneman, D.; Diener, E.; Schwarz, N. Well-Being: The Foundations of Hedonic Psychology; Russell Sage Foundation: Manhattan, NY, USA, 1999. [Google Scholar]

- Waterman, A.S. Two conceptions of happiness: Contrasts of personal expressiveness (eudaimonia) and hedonic enjoyment. J. Personal. Soc. Psychol. 1993, 64, 678–691. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bentley, W. Happiness and Being Human: The Tension between Immanence and Transcendence in Religion/Spirituality. Religions 2023, 14, 877. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ryff, C.D. Psychological well-being in adult life. Curr. Dir. Psychol. Sci. 1995, 4, 99–104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ryan, R.M.; Huta, V.; Deci, E.L. Living well: A self-determination theory perspective on eudaimonia. J. Happiness Stud. 2008, 9, 139–170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hall, C.M.; Voigt, C.; Brown, G.; Howat, G. Wellness Tourists: In Search of Transformation. Tour. Rev. 2011, 66, 16–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khan, M.A.; Ghani, U.; Aziz, S. Impact of Islamic Religiosity on Customers’ Attitudes towards Islamic and Conventional ways of Advertisements, Attitude towards Brands and Purchase Intentions. Bus. Econ. Rev. 2019, 11, 1–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lyubomirsky, S. Hedonic Adaptation to Positive and Negative Experiences. In The Oxford Handbook of Stress, Health, and Coping; Folkman, S., Ed.; Oxford University Press: Oxford, UK, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Dodds, W.B.; Monroe, K.B.; Grewal, D. Effects of price, brand and store information on buyers’ product evaluations. J. Mark. Res. 1991, 28, 307–319. [Google Scholar]

- Fournier, S. Consumers and their brands: Developing relationship theory in consumer research. J. Cons. Res. 1998, 24, 343–373. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu PC, S.; Yeh, G.Y.-Y.; Hsiao, C.-R. The effect of store image and service quality on brand image and purchase intention for private label brands. Australas. Mark. J. AMJ 2011, 19, 30–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mello, L.T.; Sauerbronn, J.F.R. Um experimento sobre intenção de compra e atitude frente a embalagem de consumidores de cosméticos com certificação ecológica. Rev. Vianna Sapiens 2017, 5, 23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martins, J.; Costa, C.; Oliveira, T.; Gonçalves, R.; Branco, F. How smartphone advertising influences consumers’ purchase intention. J. Bus. Res. 2019, 94, 378–387. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luo, M.M.; Chen, J.-S.; Chin, R.K.H.; Liu, C.-C. An examination of the effects of virtual experiential marketing on online customer intentions and loyalty. Serv. Ind. J. 2011, 31, 2163–2191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gogoi, B. Study of antecedents of purchase intention and its effect on brand loyalty of private label brand of apparel. Int. J. Sales Mark. 2013, 3, 73–86. [Google Scholar]

- Loebnitz, N.; Mueller Loose, S.; Grunert, K.G. Impacts of situational factors on process attribute uses for food purchases. Food Qual. Prefer. 2015, 44, 84–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Loebnitz, N.; Grunert, K.G. Impact of self-health awareness and perceived product benefits on purchase intentions for hedonic and utilitarian foods with nutrition claims. Food Qual. Prefer. 2018, 64, 221–231. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hsu, C.-L.; Chang, C.-Y.; Yansritakul, C. Exploring purchase intention of green skincare products using the theory of planned behavior: Testing the moderating effects of country of origin and price sensitivity. J. Retail. Consum. Serv. 2017, 34, 145–152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yadav, R.; Pathak, G.S. Young consumers’ intention towards buying green products in a developing nation: Extending the theory of planned behavior. J. Clean. Prod. 2016, 135, 732–739. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramirez, E.; Goldsmith, R.E. Some Antecedents of Price Sensitivity. J. Mark. Theory Pract. 2009, 17, 199–214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Erdmann, A.; Mas, J.M.; de Obesso, M. Disruptive technologies: How to influence price sensitivity triggering consumers’ behavioural beliefs. J. Bus. Res. 2023, 158, 113645. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Medeiros, J.F.; Duarte Ribeiro, J.L.; Nogueira Cortimiglia, M. Influence of perceived value on purchasing decisions of green products in Brazil. J. Clean. Prod. 2016, 110, 158–169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Teng, C.-C.; Lu, C.-H. Organic food consumption in Taiwan: Motives, involvement, and purchase intention under the moderating role of uncertainty. Appetite 2016, 105, 95–105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kotler, P.; Won, V.; Saunders, J.; Armstrong, G. Principles of Marketing, 4th European ed.; Prentice Hall: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Dalli, D.; Romani, S.; Gistri, G. Brand Dislike: The Dark Side of Consumer Preferences. In NA—Advances in Consumer Research; Pechmann, C., Price, L., Eds.; Association for Consumer Research: Duluth, MN, USA, 2006; Volume 33, pp. 87–95. [Google Scholar]

- Goldsmith, R.E.; Freiden, J.B.; Eastman, J.K. The generality/specificity issue in consumer innovativeness research. Technovation 1995, 15, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Insch, G.S.; McBride, J.B. The impact of country-of-origin cues on consumer perceptions of product quality: A binational test of the decomposed country-of-origin construct. J. Bus. Res. 2004, 57, 256–265. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Manrai, L.A.; Lascu, D.; Manrai, A.K. Interactive effects of country of origin and product category on product evaluations. Int. Bus. Rev. 1998, 7, 591–615. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Awada, L.; Yiannaka, A. Consumer perceptions and the effects of country of origin labeling on purchasing decisions and welfare. Food Policy 2012, 37, 21–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Godey, B.; Pederzoli, D.; Aiello, G.; Donvito, R.; Chan, P.; Oh, H.; Singh, R.; Skorobogatykh, I.I.; Tsuchiya, J.; Weitz, B. Brand and country-of-origin effect on Consumers’ decision to purchase luxury products. J. Bus. Res. 2012, 65, 1461–1470. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jabs, J.; Sobal, J.; Devine, C.M. Managing vegetarianism: Identities, norms and interactions. Ecol. Food Nutr. 2000, 39, 375–394. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Y.-S. The Driver of Green Innovation and Green Image—Green Core Competence. J. Bus. Ethics 2008, 81, 531–543. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Graaf, S.; Van Loo, E.J.; Bijttebier, J.; Vanhonacker, F.; Lauwers, L.; Tuyttens FA, M.; Verbeke, W. Determinants of consumer intention to purchase animal-friendly milk. J. Dairy Sci. 2016, 99, 8304–8313. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leonidou, L.C.; Leonidou, C.N.; Kvasova, O. Cultural drivers and trust outcomes of consumer perceptions of organizational unethical marketing behavior. Eur. J. Mark. 2013, 47, 525–556. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Podsakoff, P.M.; MacKenzie, S.B.; Lee, J.; Podsakoff, N.P. Common method biases in behavioral research: A critical review of the literature and recommended remedies. J. Appl. Psychol. 2003, 88, 879–903. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hair, J.F.; Black, W.C.; Babin, B.J.; Anderson, R.E. Multivariate Data Analysis, 7th ed.; Prentice-Hall: Saddle River, NJ, USA, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Shiu, E.; Pervan, S.J.; Bove, L.L.; Beatty, S.E. Reflections on discriminant validity: Reexamining the Bove et al., (2009) findings. J. Bus. Res. 2011, 64, 497–500. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Norman, D. The Psychology of Everyday Things; Basic Books: New York, NY, USA, 1988. [Google Scholar]

- Cheung, G.W.; Rensvold, R.B. Evaluating goodness-of-fit indexes for testing measurement invariance. Struct. Equ. Model. 2002, 9, 233–255. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jabs, J.; Devine, C.M.; Sobal, J. Model of the process of adopting vegetarian diets: Health vegetarians and ethical vegetarians. J. Nutr. Educ. 1998, 30, 196–202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pluhar, E.B. Meat and Morality: Alternatives to Factory Farming. J. Agric. Environ. Ethics 2010, 23, 455–468. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- MacNair, R. McDonald’s “Empirical Look at Becoming Vegan”. Soc. Anim. 1998, 9, 63–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Earle, M.; Hodson, G.; Dhont, K.; MacInnis, C. Eating with our eyes (closed): Effects of visually associating animals with meat on antivegan/vegetarian attitudes and meat consumption willingness. Group Process. Intergr. Relat. 2019, 22, 818–835. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Backer, C.J.S.; Hudders, L. Meat morals: Relationship between meat consumption consumer attitudes towards human and animal welfare and moral behavior. Meat Sci. 2015, 99, 68–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gagne, M.; Deci, E.L. Self-determination theory and work Motivation. J. Organ. Behav. 2005, 26, 331–362. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ryan, R.M.; Sheldon, K.M.; Kasser, T.; Deci, E.L. All goals were not created equal: An organismic perspective on the nature of goals and their regulation. In The Psychology of Action: Linking Cognition and Motivation to Behavior; Gollwitzer, P.M., Bargh, J.A., Eds.; Guilford: New York, NY, USA, 1996; pp. 7–26. [Google Scholar]

- Jalil, A.J.; Tasoff, J.; Bustamante, A.V. Eating to save the planet: Evidence from a randomized controlled trial using individual-level food purchase data. Food Policy 2020, 95, 101950. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Category | Vegans (580) | Non-Vegans (517) |

|---|---|---|

| Male | 170 | 165 |

| Female | 410 | 352 |

| Age | ||

| 10–17 | 18 | 15 |

| 18–25 | 218 | 165 |

| 26–33 | 190 | 162 |

| 34–41 | 90 | 97 |

| Over 41 | 64 | 78 |

| Educational background | ||

| Until 12th grade | 201 | 136 |

| Higher education | 379 | 381 |

| Occupation | ||

| Student/Student worker | 158 | 194 |

| Employed | 282 | 287 |

| others | 68 | 36 |

| Household members | ||

| 1–2 | 279 | 217 |

| Over 3 | 301 | 300 |

| Income | ||

| Less than 500 € | 77 | 107 |

| 501 €–1499 € | 278 | 184 |

| Over 1500 € | 225 | 226 |

| Construct | Metrics | Vegan | Non-Vegan | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| SRW | CR | SRW | CR | ||

| Animal welfare (AW) (Graaf et al., 2016) [183] | 1. Animals must be kept in their natural habitat. | 0.717 | 0.611 | ||

| 2. It is important that animals can behave naturally. | 0.908 | 25.141 | 0.77 | 18.676 | |

| 3. I care about the welfare of animals. | 0.884 | 20.089 | 0.741 | 13.334 | |

| 4. Animals must not suffer. | 0.901 | 20.476 | 0.818 | 14.3 | |

| 5. The idea of a “natural environment” applies to both domestic and wild animals. | 0.651 | 15.094 | 0.714 | 13.104 | |

| 6. Companies must think about their profits, but also about animals. | 0.783 | 18.103 | 0.814 | 14.315 | |

| 7. Companies must think about animals as well as their market value and costs. | 0.702 | 16.252 | 0.761 | 13.693 | |

| Ecological motivations (EM) (Yadav & Pathak, 2016) [169] | 1. It is very important that production of vegan products respect animal rights. | 0.835 | 0.779 | ||

| 2. It is very important that vegan products have been prepared in an ecological environment. | 0.906 | 28.789 | 0.924 | 23.076 | |

| 3. It is very important that vegan products are packaged ecologically. | 0.930 | 30.163 | 0.868 | 21.495 | |

| 4. It is very important that vegan products have been produced in a way that does not unbalance nature. | 0.935 | 30.438 | 0.871 | 21.601 | |

| Environmental concerns (EC) (Yadav & Pathak, 2016) [169] | 1. The balance of nature is very delicate and can be easily changed. | 0.749 | 0.848 | ||

| 2. Human beings, when they interfere with nature, often cause disastrous consequences. | 0.85 | 21.116 | 0.923 | 29.391 | |

| 3. Human beings must live in harmony with nature to survive. | 0.858 | 21.346 | 0.926 | 29.527 | |

| 4. Humanity is abusing the environment. | 0.885 | 22.056 | 0.926 | 29.581 | |

| 5. Humanity was not created to dominate the rest of nature. | 0.809 | 19.981 | 0.86 | 25.662 | |

| Idealism (ID) (Leonidou, Leonidou & Kvasova, 2013) [184] | 1. I respect the principles and universal values when doing judgments. | 0.782 | 0.785 | ||

| 2. There are universal principles or ethical rules that can be applied to most parts of situations. | 0.882 | 20.433 | 0.872 | 21.245 | |

| 3. Regardless of circumstances, there are principles and overlapping rules. | 0.667 | 15.916 | 0.844 | 20.515 | |

| 4. We must prevent others from taking risks. | 0.691 | 16.564 | 0.79 | 18.975 | |

| Social Influence (SI) (Varshneya, Pandey & Das, 2017) [133] | 1. My friends often recommend vegan products to me. | 0.931 | 0.938 | ||

| 2. My friends usually go shopping for vegan products with me. | 0.727 | 18.373 | 0.939 | 41.62 | |

| 3. My friends often share their experiences and knowledge about vegan products with me. | 0.865 | 20.78 | 0.952 | 43.589 | |

| Involvement with vegan products (INV) (Teng & Lu, 2016) [173] | 1. Vegan products are important to me. | 0.931 | 0.978 | ||

| 2. Vegan products remain interesting to me. | 0.900 | 34.378 | 0.977 | 71.68 | |

| 3. I am concerned about animal issues. | 0.764 | 24.338 | 0.928 | 49.071 | |

| 4. I am very involved in finding and reading information about vegan products. | 0.630 | 17.771 | 0.882 | 39.000 | |

| Eudaemonic Happiness (EUD) (Ryan & Deci 2001) [60] | 1. Veganism helped me become self-determining and independent. | 0.864 | 0.817 | ||

| 2. Veganism helped me have warm, satisfying, and trusting relationships with others. | 0.976 | 38.322 | 0.846 | 44.965 | |

| 3. Veganism helped me possess a positive attitude toward myself. | 0.848 | 27.965 | 0.822 | 22.927 | |

| 4. Veganism helped me feel there is meaning to present and past life. | 0.857 | 28.54 | 0.997 | 32.071 | |

| 5. Veganism helped me develop a lot as a person. | 0.849 | 27.871 | 0.996 | 29.569 | |

| 6. Veganism helped me have a sense of mastery and competence in managing the environment. | 0.992 | 39.75 | 0.994 | 31.932 | |

| Hedonic happiness (HED) (Van Boven & Gilovich, 2003) [51] | 1. Veganism increased my overall life satisfaction. | 0.905 | 0.919 | ||

| 2. Veganism contributed to my overall happiness. | 0.965 | 40.495 | 0.951 | 38.796 | |

| 3. Veganism has improved my overall well-being. | 0.908 | 35.276 | 0.901 | 33.712 | |

| Purchase intention (PI) (Teng & Lu, 2016) [173] | 1. I am happy to buy vegan products. | 0.846 | 0.847 | ||

| 2. I hope to consume vegan products. | 0.833 | 24.078 | 0.924 | 29.262 | |

| 3. I would buy vegan products. | 0.795 | 22.493 | 0.93 | 29.667 | |

| 4. I plan to consume vegan products. | 0.808 | 19.705 | 0.951 | 26.404 | |

| 5. I intend to buy vegan products in the next few days. | 0.667 | 17.684 | 0.789 | 22.213 | |

| Price sensitivity (PS) (Ramirez & Goldsmith, 2009) [170] | 1. I am willing to buy vegan products even if I think they will have a high cost. | 0.798 | 0.822 | ||

| 2. It is worth spending money on buying vegan products. | 0.819 | 19.305 | 0.835 | 20.251 | |

| 3. I don’t mind spending money to buy vegan products. | 0.809 | 19.164 | 0.83 | 20.138 | |

| Constructs | SD | AW | EM | EC | ID | SI | INV | EUD | HED | PI | PS | AVE | CR |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| AW | 0.382 | 0.919 | 0.637 | 0.924 | |||||||||

| EM | 0.531 | 0.13 | 0.943 | 0.814 | 0.946 | ||||||||

| EC | 0.390 | 0.239 | 0.138 | 0.913 | 0.691 | 0.918 | |||||||

| ID | 1.009 | 0.148 | 0.25 | 0.248 | 0.837 | 0.578 | 0.844 | ||||||

| SI | 1.708 | 0.026 | −0.068 | 0.17 | 0.051 | 0.852 | 0.662 | 0.854 | |||||

| INV | 0.725 | 0.194 | 0.087 | 0.246 | 0.175 | 0.097 | 0.872 | 0.664 | 0.886 | ||||

| EUD | 1.401 | 0.139 | 0.154 | 0.169 | 0.199 | 0.041 | 0.201 | 0.97 | 0.81 | 0.962 | |||

| HED | 1.005 | 0.138 | 0.06 | 0.164 | 0.175 | 0.275 | 0.384 | 0.22 | 0.947 | 0.858 | 0.948 | ||

| PI | 0.647 | 0.221 | 0.098 | 0.237 | 0.185 | 0.094 | 0.716 | 0.163 | 0.396 | 0.873 | 0.628 | 0.893 | |

| PS | 1.105 | 0.201 | 0.213 | 0.185 | 0.255 | 0.161 | 0.333 | 0.133 | 0.247 | 0.374 | 0.839 | 0.654 | 0.85 |

| Constructs | SD | AW | EM | EC | ID | SI | INV | EUD | HED | PI | PS | AVE | CR |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| AW | 0.436 | 0.899 | 0.562 | 0.899 | |||||||||

| EM | 0.378 | 0.477 | 0.923 | 0.743 | 0.92 | ||||||||

| EC | 0.463 | 0.403 | 0.536 | 0.953 | 0.805 | 0.954 | |||||||

| ID | 0.916 | 0.326 | 0.3 | 0.429 | 0.892 | 0.678 | 0.894 | ||||||

| SI | 1.807 | 0.101 | 0.078 | 0.078 | 0.11 | 0.96 | 0.889 | 0.96 | |||||

| INV | 1.001 | 0.453 | 0.399 | 0.371 | 0.276 | 0.142 | 0.969 | 0.888 | 0.969 | ||||

| EUD | 1.529 | 0.192 | 0.152 | 0.103 | 0.19 | 0.073 | 0.413 | 0.971 | 0.839 | 0.969 | |||

| HED | 1.517 | 0.324 | 0.19 | 0.167 | 0.179 | 0.312 | 0.599 | 0.466 | 0.945 | 0.854 | 0.949 | ||

| PI | 1.008 | 0.497 | 0.451 | 0.41 | 0.248 | 0.141 | 0.719 | 0.411 | 0.596 | 0.942 | 0.793 | 0.95 | |

| PS | 1.179 | 0.381 | 0.235 | 0.3 | 0.269 | 0.234 | 0.467 | 0.27 | 0.359 | 0.491 | 0.862 | 0.687 | 0.868 |

| Vegan (n = 580) | Non-Vegan (n = 517) | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| srw | p | srw | p | |

| H1: Animal Welfare → Involvement | 0.145 | 0.001 | 0.299 | *** |

| H2: Ecological motivations → Involvement | 0.028 | 0.519 | 0.165 | 0.002 |

| H3: Environmental concerns → Involvement | 0.178 | *** | 0.131 | 0.010 |

| H4: Idealism → Involvement | 0.113 | 0.017 | 0.066 | 0.153 |

| H5: Social influence → Involvement | 0.071 | 0.115 | 0.088 | 0.025 |

| H6: Involvement → Eudaemonic Happiness | 0.344 | *** | 0.420 | *** |

| H7: Involvement → Hedonic happiness | 0.787 | *** | 0.607 | *** |

| H8: Involvement → Purchase intention | 0.211 | *** | 0.472 | *** |

| H9: Involvement → Price sensitivity | 0.403 | *** | 0.787 | *** |

| H10: Price sensitivity → Purchase intention | 0.103 | 0.002 | 0.119 | *** |

| Research Gap | Previous Studies and Additional Insights | SDT and Motivations for Involvement with Vegan Products |

|---|---|---|

| Literature indicates limited research on involvement with vegan products and motivations for adopting a vegan lifestyle (Earle & Hodson, 2017; Bagci & Olgun, 2019) [32,33]. | Ethical values steer food intake (De Backer et al., 2015; Ruby et al., 2013) [101,194]. | SDT outlines intrinsic and extrinsic motivation, explaining that behavior is molded by the satisfaction of getting what is wanted (Gilal et al., 2019) [63]. |

| Lack of investigation into the involvement with a vegan diet and vegan products (Earle et al., 2019) [193]. | Veganism extends beyond vegans; non-vegans choose to partially follow this lifestyle due to the rising social movement concerning animal welfare, rights, cruelty, and environment protection. | Vegans and non-vegans consume products related to themselves, positively impacting individual well-being and the overall environment (Khan, Ghani, & Aziz, 2019) [157]. |

| Investigation on veganism is primarily diet-focused, with other motivations such as social influence and ideology remaining largely uninvestigated (Greenebaum, 2018) [56]. | Study supports past literature, showing that vegan products are consumed by both vegans and non-vegans, indicating diverse behaviors and contributing to the rise of a potentially profitable market. | Individuals involved with vegan products experience satisfaction from fulfilling their needs, leading to a sense of achievement, fulfillment, and well-being (Gagne & Deci, 2005; Ryan et al., 1996) [195,196]. |

| (1) Comparison of ideology and individual features as antecedents of involvement with vegan products, laying the basis for further investigations on drivers and motivations of veganism. |

| (2) Examination of impacts on well-being, exploring the relationship between a lifestyle or consumption that provides happiness and well-being and the future and growth of veganism. |

| (3) Analysis of impacts on price sensitivity, revealing that prices are less relevant, and customers are willing to pay more for vegan products. |

| (4) Comparison of vegans and non-vegans regarding involvement with vegan products, highlighting how social issues may lead to greater involvement, and non-vegans are willing to pay more. |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Miguel, I.; Coelho, A.; Bairrada, C. Let’s Be Vegan? Antecedents and Consequences of Involvement with Vegan Products: Vegan vs. Non-Vegan. Sustainability 2024, 16, 105. https://doi.org/10.3390/su16010105

Miguel I, Coelho A, Bairrada C. Let’s Be Vegan? Antecedents and Consequences of Involvement with Vegan Products: Vegan vs. Non-Vegan. Sustainability. 2024; 16(1):105. https://doi.org/10.3390/su16010105

Chicago/Turabian StyleMiguel, Isabel, Arnaldo Coelho, and Cristela Bairrada. 2024. "Let’s Be Vegan? Antecedents and Consequences of Involvement with Vegan Products: Vegan vs. Non-Vegan" Sustainability 16, no. 1: 105. https://doi.org/10.3390/su16010105

APA StyleMiguel, I., Coelho, A., & Bairrada, C. (2024). Let’s Be Vegan? Antecedents and Consequences of Involvement with Vegan Products: Vegan vs. Non-Vegan. Sustainability, 16(1), 105. https://doi.org/10.3390/su16010105