Marketing Sustainable Fashion: Trends and Future Directions

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Theoretical Background

2.1. Sustainability, Climate Change, and Business

2.2. Marketing and Sustainability

2.3. Role of Fashion in Sustainability

2.4. Sustainable Fashion

2.5. Marketing of SF

- Business to consumer (B2C);

- Business to business (B2B).

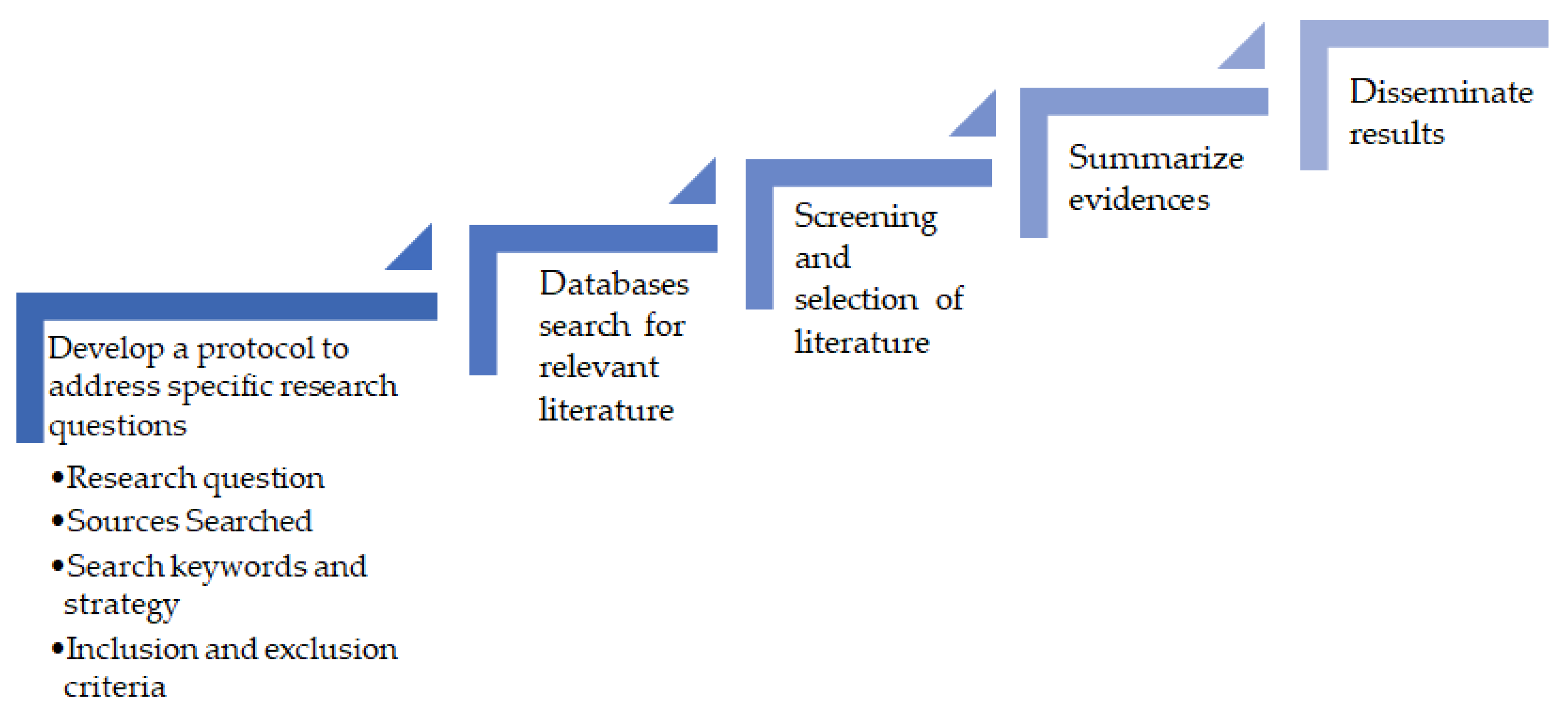

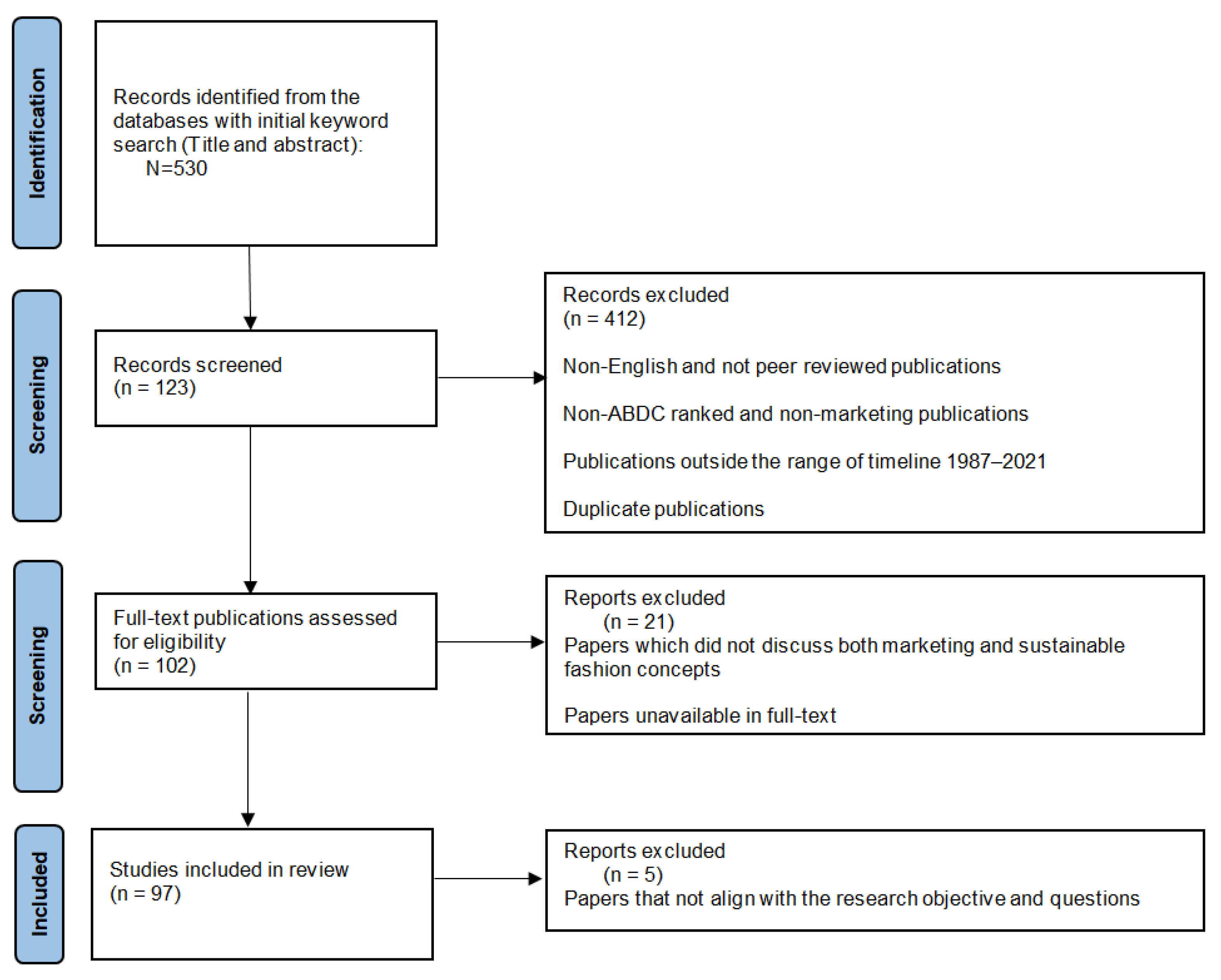

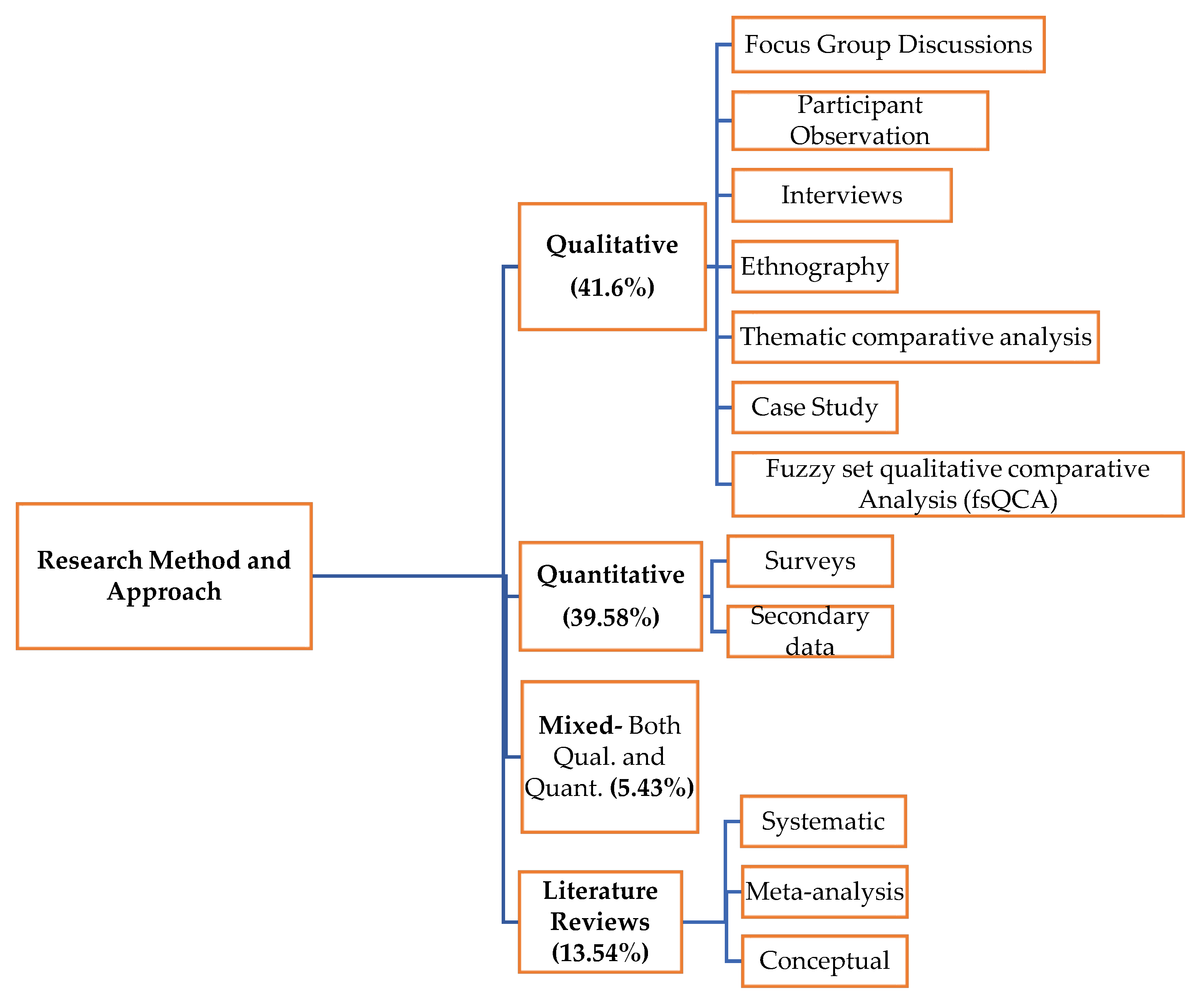

3. Systematic Literature Review (SLR) Methodology

3.1. Search for Existing Literature

3.2. Screening

3.3. Eligibility Criteria

3.4. Inclusion

4. Findings

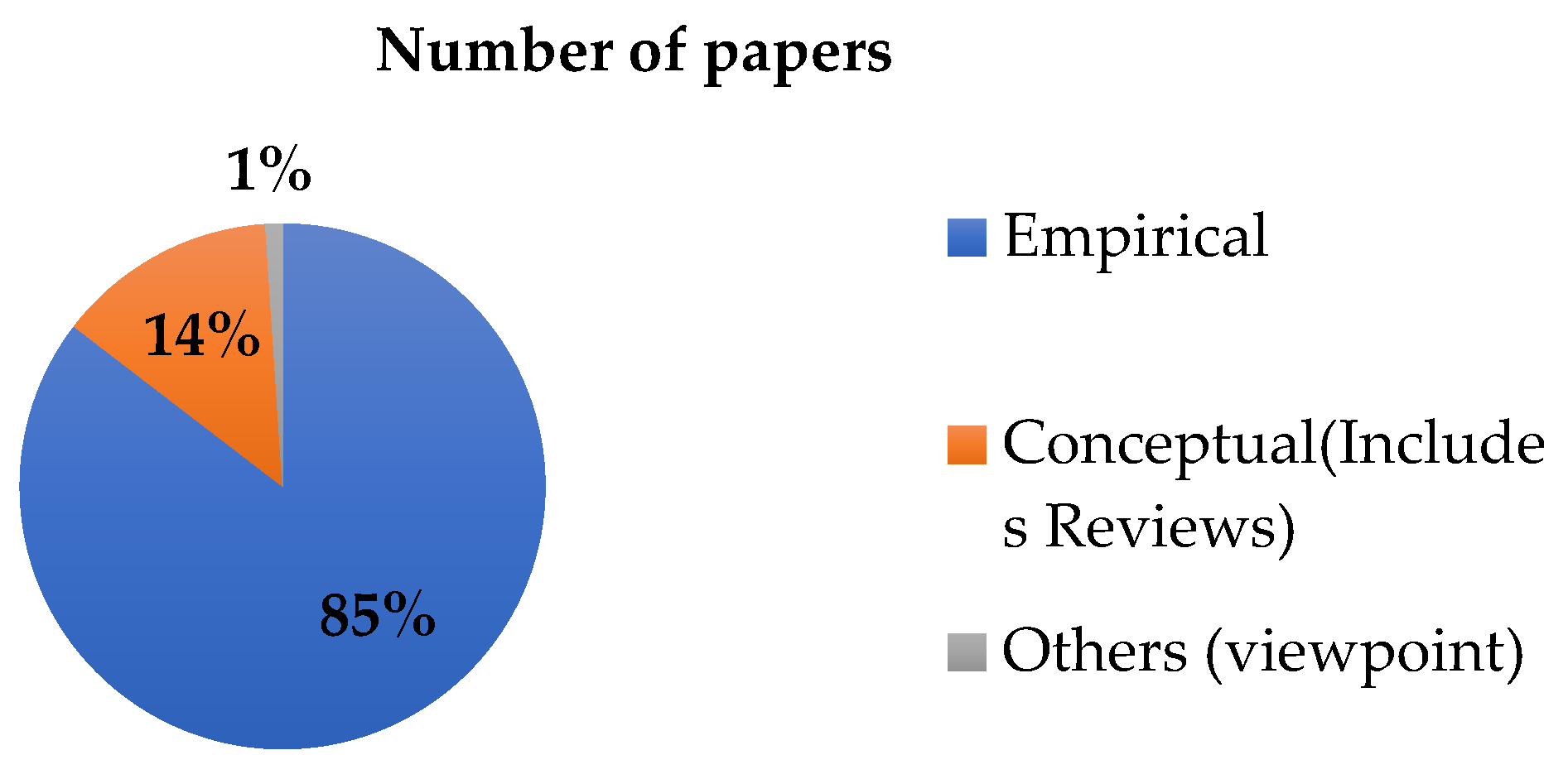

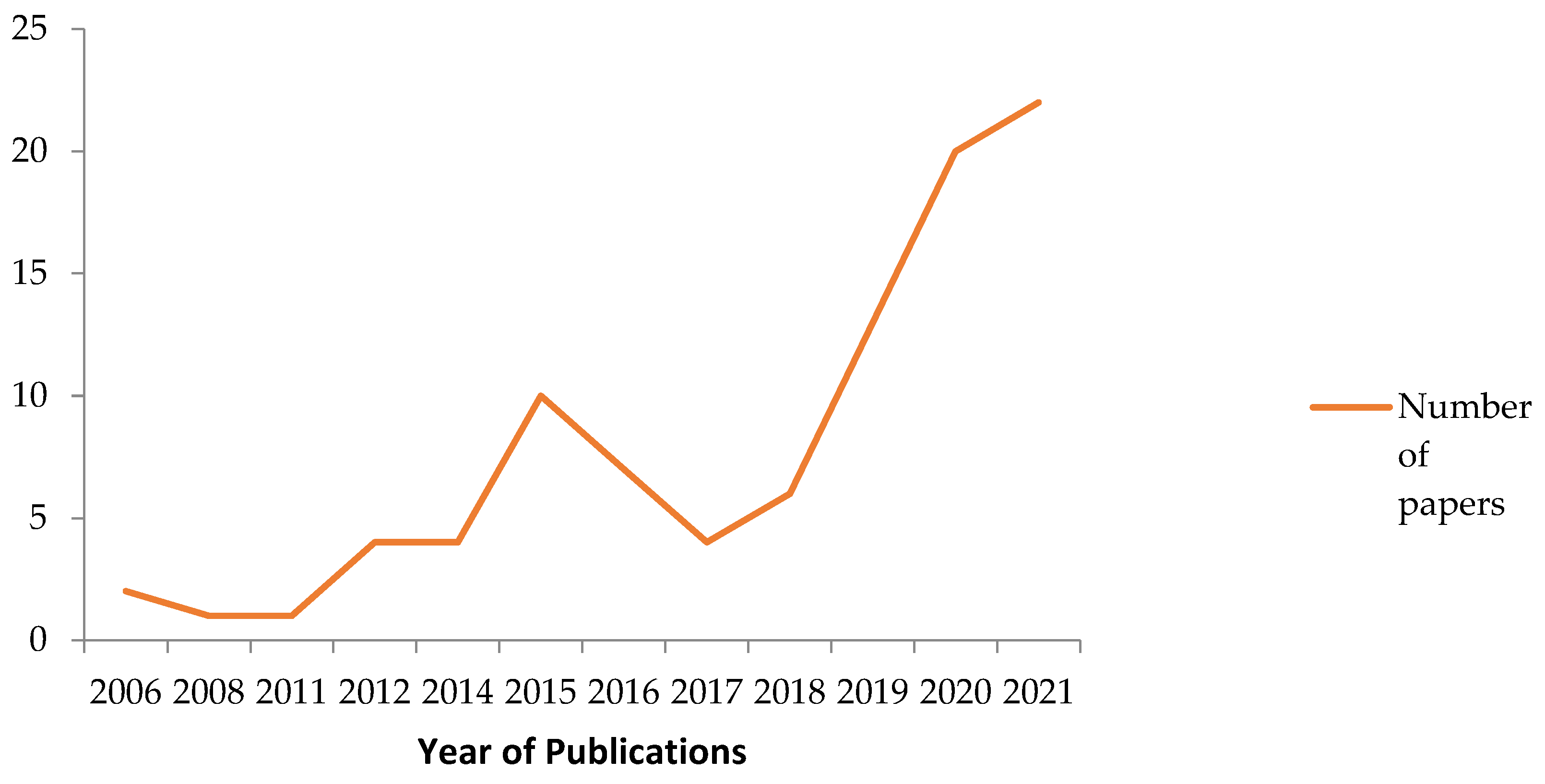

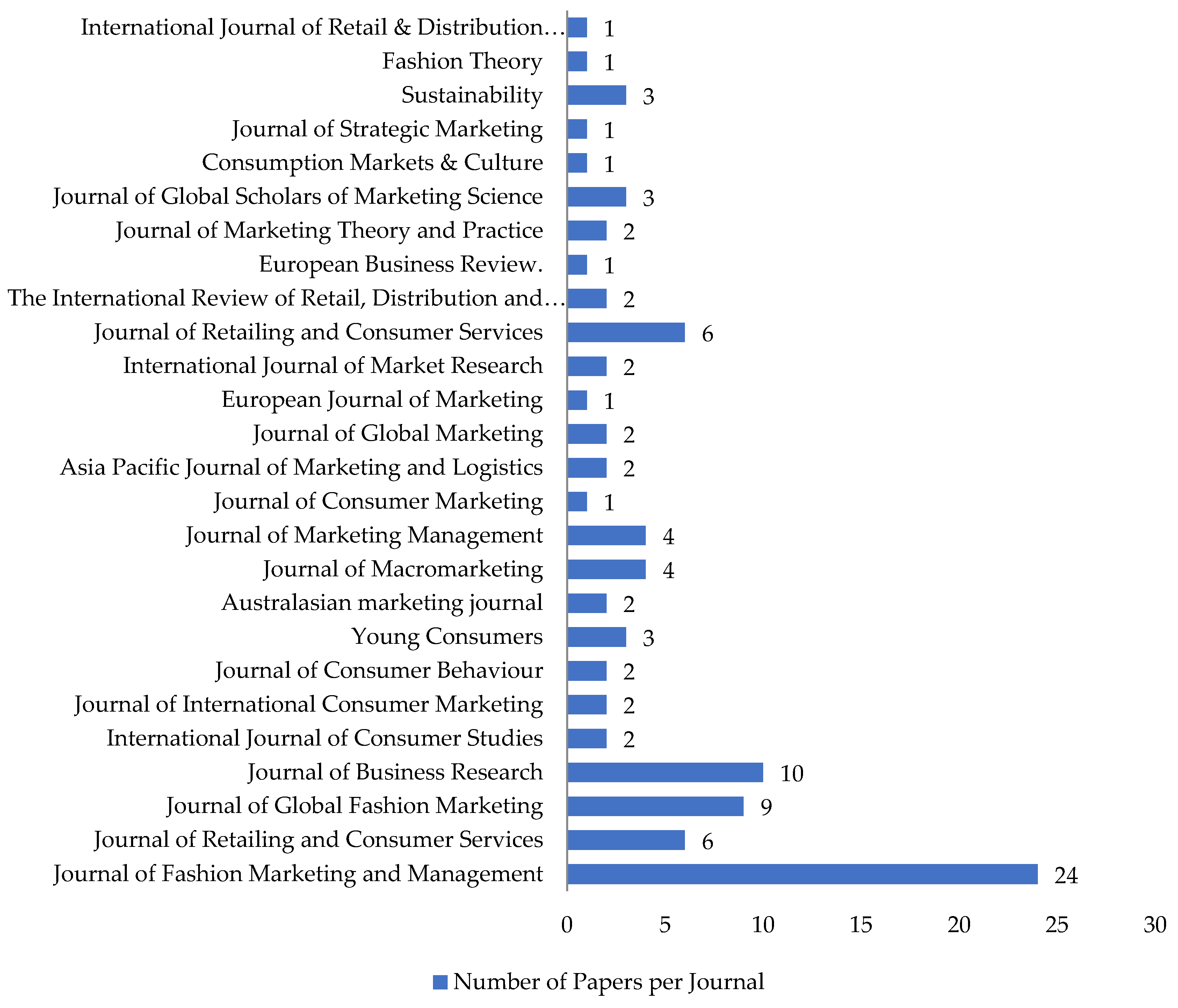

4.1. Descriptive Analysis

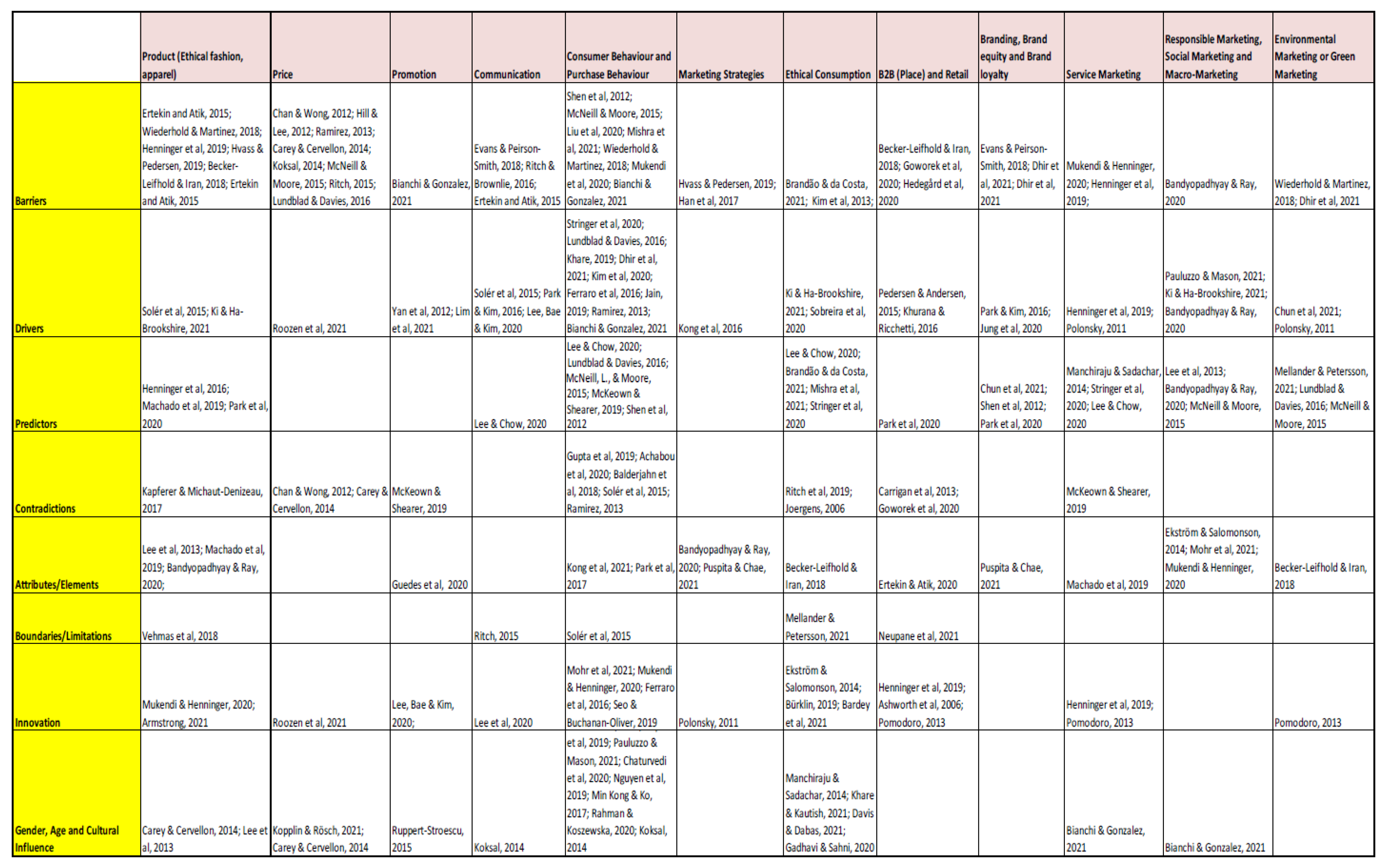

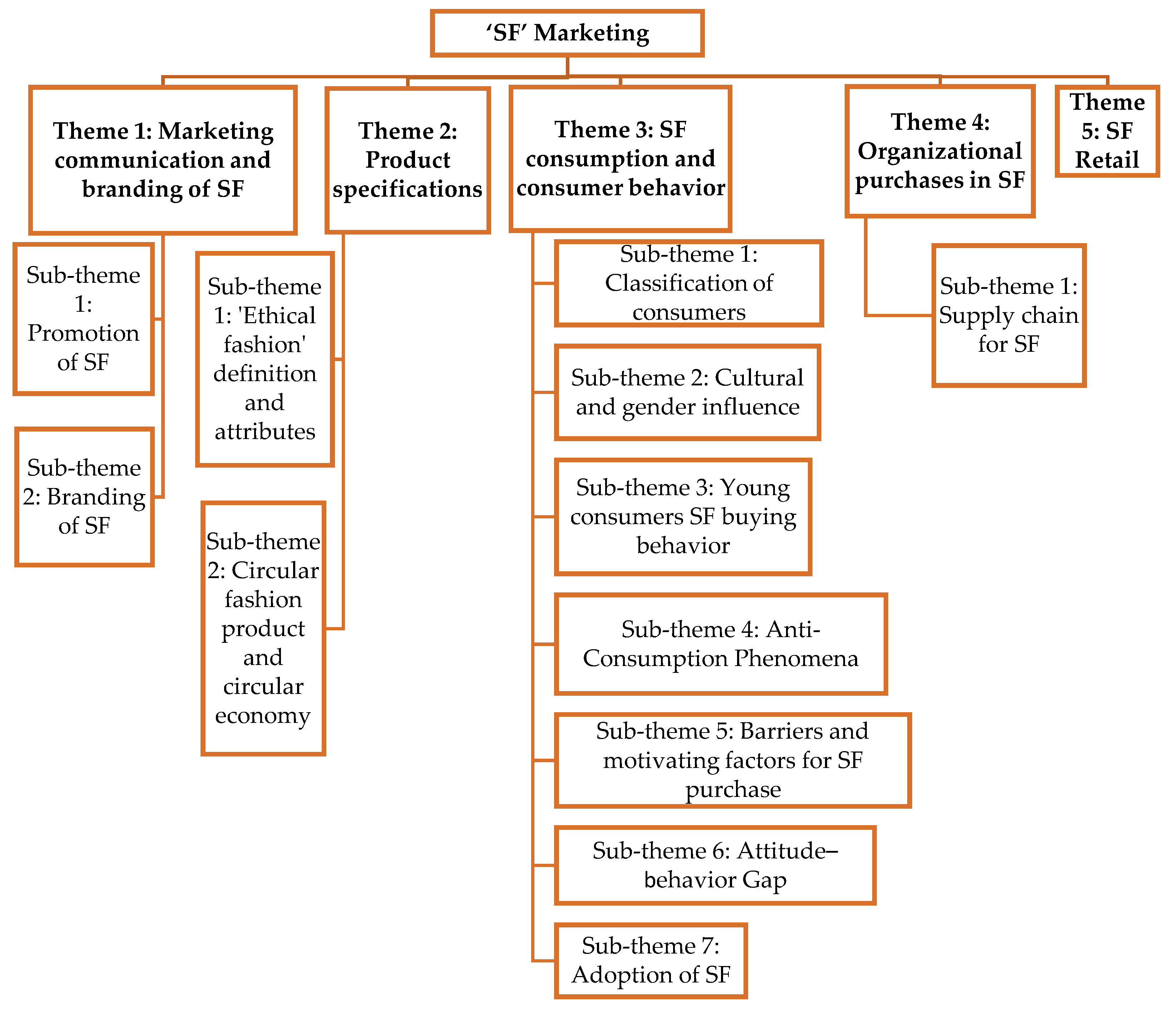

4.2. Thematic Analysis

4.2.1. Theme 1: Marketing Communication and Branding of SF. (21 Papers)

Sub-Theme 1: Promotion of SF (8 Papers)

Sub-Theme 2: Branding of SF (12 Papers)

4.2.2. Theme 2: Product Specifications (21 Papers)

Sub-Theme 1: ‘Ethical Fashion’ Definitions and Attributes (6 Papers)

Sub-Theme 2: Circular Fashion Products and Circular Economy (13 Papers)

4.2.3. Theme 3: SF Consumption and Consumer Behavior (77 Papers)

Sub-Theme 1: Segmentation of Consumers (8 Papers)

Sub-Theme 2: Culture and Gender Influence (19 Papers)

Sub-Theme 3: Young Consumers’ SF Buying Behavior (7 Papers)

Sub-Theme 4: Anti-Consumption and Fast Fashion Avoidance Phenomena (3 Papers)

Sub-Theme 5: Barriers and Motivating Factors for SF Purchase (15 Papers)

Sub-Theme 6: Attitude–Behavior Gap (11 Papers)

Sub-Theme 7: Adoption of SF (5 Papers)

4.2.4. Theme 4: Organizational Purchases in SF (10 Papers)

Sub-Theme 1: SF Supply Chain (8 Papers)

4.2.5. Theme 5: SF Retail. (6 Papers)

5. Discussion

- What do we know about marketing sustainable fashion (SF)?

- How can marketing facilitate the popularization and mainstreaming of SF?

Theoretical Contribution and Future Research Directions

- Marketers and brand managers have to take up strategies for creating awareness and education of consumers regarding the SF and the peripheral activities related to its value chain (from eco-friendly raw material procurement to environmentally safe disposal or recycling). For example, consumers’ knowledge about eco-labels can be enhanced through marketing;

- The SF brands should work towards making value-based segmentation [10,98,99,101] and pricing strategies. For example, customers value fast fashion companies’ low-priced trendy designs. Similarly, SF brands must create a value proposition for customers in terms of longevity, sustainability, and social responsibility;

- Findings indicate a need for macro-marketing and policy-level change for mainstreaming SF [135]. Macro-level changes, such as policy formulation, certification on authenticity, or keeping a tab on sustainability across the fashion value chain, measures for fair trade, etc., can bring long-term change in the SF value chain. There is a need for national and global collaboration among leading brands to establish national/global frameworks for sustainable fashion. Initiatives such as the sustainable fashion coalition [151] can help SF brands to collaborate and co-create marketing strategies to mainstream SF;

- Our findings suggest that social media platforms are the most effective way for consumers’ to engage with SF. Thus, marketers and managers should leverage social media’s effectiveness innovatively through digital and influencer marketing. Marketing communication will be able to create narratives that promote values aligned with SF;

- Retailers can play an essential role by choice editing—deciding what to keep in the store to influence consumer choice and purchase. They can also design a reverse logistics system and encourage customers to return clothes to designated points, thus promoting a circular transition in SF.

6. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Keeble, B.R. The Brundtland Report: “Our Common Future”. Med. War 1988, 4, 17–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Borowy, I. Defining Sustainable Development for Our Common Future: A History of the World Commission on Environment and Development (Brundtland Commission); Routledge: London, UK, 2013. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Norton, B. Sustainability, Human Welfare, and Ecosystem Health. Environ. Values 1992, 1, 97–111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jonathen, W.; Hamid, S.; Hauke, E.; Mekala, K.; Brodie, B. Confronting Climate Risk. Mckinsey.com. Available online: https://www.mckinsey.com/business-functions/sustainability/our-insights/confronting-climate-risk (accessed on 20 October 2021).

- Comin, L.C.; Aguiar, C.C.; Sehnem, S.; Yusliza, M.-Y.; Cazella, C.F.; Julkovski, D.J. Sustainable business models: A literature review. Benchmarking Int. J. 2020, 27, 2028–2047. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Freudenreich, B.; Lüdeke-Freund, F.; Schaltegger, S. A Stakeholder Theory Perspective on Business Models: Value Creation for Sustainability. J. Bus. Ethics 2020, 166, 3–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nosratabadi, S.; Mosavi, A.; Shamshirband, S.; Kazimieras Zavadskas, E.; Rakotonirainy, A.; Chau, K.W. Sustainable Business Models: A Review. Sustainability 2019, 11, 1663. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mio, C.; Panfilo, S.; Blundo, B. Sustainable development goals and the strategic role of business: A systematic literature review. Bus. Strat. Environ. 2020, 29, 3220–3245. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kotler, P. A Generic Concept of Marketing. J. Mark. 1972, 36, 46–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tolkamp, J.; Huijben, J.; Mourik, R.; Verbong, G.; Bouwknegt, R. User-centred sustainable business model design: The case of energy efficiency services in the Netherlands. J. Clean. Prod. 2018, 182, 755–764. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, E.-J.; Choi, H.; Han, J.; Kim, D.H.; Ko, E.; Kim, K.H. How to “Nudge” your consumers toward sustainable fashion consumption: An fMRI investigation. J. Bus. Res. 2020, 117, 642–651. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roozen, I.; Raedts, M.; Meijburg, L. Do verbal and visual nudges influence consumers’ choice for sustainable fashion? J. Glob. Fash. Mark. 2021, 12, 327–342. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Patagonia. Worn Wear—Better than New. Available online: https://wornwear.patagonia.com/ (accessed on 28 February 2023).

- Voola, R.; Bandyopadhyay, C.; Azmat, F.; Ray, S.; Nayak, L. How are consumer behavior and marketing strategy researchers incorporating the SDGs? A review and opportunities for future research. Australas. Mark. J. 2022, 30, 119–130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dahl, R. Green Washing. Environ. Health Perspect. 2010, 118, A246–A252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sailer, A.; Wilfing, H.; Straus, E. Greenwashing and Bluewashing in Black Friday-Related Sustainable Fashion Marketing on Instagram. Sustainability 2022, 14, 1494. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berliner, D.; Prakash, A. “Bluewashing” the Firm? Voluntary Regulations, Program Design, and Member Compliance with the United Nations Global Compact. Policy Stud. J. 2015, 43, 115–138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chandy, R.K.; Johar, G.V.; Moorman, C.; Roberts, J.H. Better Marketing for a Better World. J. Mark. 2021, 85, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oxfordlearnersdictionaries.com. Available online: https://www.oxfordlearnersdictionaries.com/definition/english (accessed on 7 July 2022).

- Kaiser, S.B.; Green, D.N. Fashion and Cultural Studies; Bloomsbury Publishing: London, UK, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Steele, V. Definition of Fashion. LoveToKnow. Available online: https://fashion-history.lovetoknow.com/alphabetical-index-fashion-clothing-history/definitionn-fashion (accessed on 20 November 2022).

- Simmel, G. Fashion. Am. J. Sociol. 1957, 62, 541–558. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Simmel, G. Fashion. In Fashion Theory; Routledge: Oxfordshire, UK, 2020; pp. 92–101. [Google Scholar]

- Cambridge.org. Available online: https://dictionary.cambridge.org/dictionary/english (accessed on 21 November 2022).

- Fletcher, K.; Grose, L. Fashion & Sustainability: Design for Change; Hachette: London, UK, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Niinimäki, K.; Peters, G.; Dahlbo, H.; Perry, P.; Rissanen, T.; Gwilt, A. The environmental price of fast fashion. Nat. Rev. Earth Environ. 2020, 1, 189–200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kapferer, J.-N.; Michaut-Denizeau, A. Is Luxury Compatible with Sustainability? Luxury Consumers’ Viewpoint. In Advances in Luxury Brand Management; Palgrave Macmillan: Cham, Switzerland, 2017; pp. 123–156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clark, H. SLOW + FASHION—An Oxymoron—Or a Promise for the Future…? Fash. Theory 2008, 12, 427–446. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carey, L.; Cervellon, M.-C. Ethical fashion dimensions: Pictorial and auditory depictions through three cultural perspectives. J. Fash. Mark. Manag. Int. J. 2014, 18, 483–506. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hill, J.; Lee, H.-H. Young Generation Y consumers’ perceptions of sustainability in the apparel industry. J. Fash. Mark. Manag. 2012, 16, 477–491. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salmeron, J.L.; Hurtado, J.M. Modelling the reasons to establish B2C in the fashion industry. Technovation 2006, 26, 865–872. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharma, N.; Saha, R.; Rameshwar, R. I Don’t Buy LED Bulbs but I Switch off the Lights” Green Consumption versus Sustainable Consumption. J. Indian Bus. Res. 2019, 11, 138–161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spielmann, N. Green is the New White: How Virtue Motivates Green Product Purchase. J. Bus. Ethics 2021, 173, 759–776. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Atthirawong, W.; Panprung, W. A Study on the Consumers’ Buying Behavior towards Green Products in Bangkok. Int. J. Manag. Appl. Sci. 2017, 3, 26–31. [Google Scholar]

- Gleim, M.R.; Smith, J.S.; Andrews, D.; Cronin, J.J., Jr. Against the Green: A Multi-method Examination of the Barriers to Green Consumption. J. Retail. 2013, 89, 44–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peattie, K. Green Consumption: Behavior and Norms. Annu. Rev. Environ. Resour. 2010, 35, 195–228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moser, A.K. Thinking green, buying green? Drivers of pro-environmental purchasing behavior. J. Consum. Mark. 2015, 32, 167–175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Perry, A.; Chung, T. Understand attitude-behavior gaps and benefit-behavior connections in Eco-Apparel. J. Fash. Mark. Manag. Int. J. 2016, 20, 105–119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chan, T.Y.; Wong, C.W. The Consumption Side of Sustainable Fashion Supply Chain: Understanding Fashion Consumer Eco-Fashion Consumption Decision. J. Fash. Mark. Manag. Int. J. 2012, 16, 193–215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharma, A. Sustainability research in business-to-business markets: An agenda for inquiry. Ind. Mark. Manag. 2020, 88, 323–329. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fink, A. Conducting Research Literature Reviews: From the Internet to Paper; Sage Publications: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Booth, A.; Sutton, A.; Clowes, M.; Martyn-St James, M. Systematic Approaches to a Successful Literature Review; SAGE Publications: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Boell, S.K.; Cecez-Kecmanovic, D. On Being ‘Systematic’ in Literature Reviews. Formulating research methods for information systems. J. Inf. Technol. 2015, 30, 48–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moher, D.; Liberati, A.; Tetzlaff, J.; Altman, D.G.; PRISMA Group. Preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses: The PRISMA statement. Int. J. Surg. 2010, 8, 336–341. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tranfield, D.; Denyer, D.; Smart, P. Towards a Methodology for Developing Evidence-Informed Management Knowledge by Means of Systematic Review. Br. J. Manag. 2003, 14, 207–222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bandyopadhyay, C.; Ray, S. Social enterprise marketing: Review of literature and future research agenda. Mark. Intell. Plan. 2020, 38, 121–135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Henninger, C.E.; Alevizou, P.J.; Oates, C.J. What is sustainable fashion? J. Fash. Mark. Manag. Int. J. 2016, 20, 400–416. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khandual, A.; Pradhan, S. Fashion Brands and Consumers Approach Towards Sustainable Fashion. In Fast Fashion, Fashion Brands and Sustainable Consumption; Muthu, S., Ed.; Textile Science and Clothing Technology; Springer: Singapore, 2018; pp. 37–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kong, H.M.; Ko, E.; Chae, H.; Mattila, P. Understanding fashion consumers’ attitude and behavioral intention toward sustainable fashion products: Focus on sustainable knowledge sources and knowledge types. J. Glob. Fash. Mark. 2016, 7, 103–119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McKeown, C.; Shearer, L. Taking sustainable fashion mainstream: Social media and the institutional celebrity entrepreneur. J. Consum. Behav. 2019, 18, 406–414. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Testa, D.S.; Bakhshian, S.; Eike, R. Engaging consumers with sustainable fashion on Instagram. J. Fash. Mark. Manag. Int. J. 2021, 25, 569–584. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, H.; Kim, Y.-K. Proactive versus reactive apparel brands in sustainability: Influences on brand loyalty. J. Retail. Consum. Serv. 2016, 29, 114–122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yan, R.N.; Hyllegard, K.H.; Blaesi, L.F. Marketing Eco-Fashion: The Influence of Brand Name and Message Explicitness. J. Mark. Commun. 2012, 18, 151–168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lim, D.J.; Youn, N.; Eom, H.J. Green Advertising for the Sustainable Luxury Market. Australas. Mark. J. 2021, 29, 288–296. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guedes, B.; Bardey, A.; Schat, A. Improving sustainable fashion marketing and advertising: A reflection on framing message and target audience. Int. J. Mark. Res. 2020, 62, 124–126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, E.J.; Bae, J.; Kim, K.H. The effect of sustainable certification reputation on consumer behavior in the fashion industry: Focusing on the mechanism of congruence. J. Glob. Fash. Mark. 2020, 11, 137–153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- American Marketing Association. Available online: https://www.ama.org/topics/branding/ (accessed on 22 November 2022).

- Murphy, J.M. What Is Branding? In Branding: A Key Marketing Tool; Palgrave Macmillan UK: London, UK, 1992; pp. 1–12. [Google Scholar]

- Solér, C.; Baeza, J.; Svärd, C. Construction of silence on issues of sustainability through branding in the fashion market. J. Mark. Manag. 2015, 31, 219–246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kong, H.M.; Witmaier, A.; Ko, E. Sustainability and social media communication: How consumers respond to marketing efforts of luxury and non-luxury fashion brands. J. Bus. Res. 2021, 131, 640–651. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Neupane, S.; Chimhundu, R.; Kong, E. Strategic profile for positioning eco-apparel among mainstream apparel consumers. J. Glob. Fash. Mark. 2021, 12, 229–244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bandyopadhyay, C.; Ray, S. Finding the Sweet Spot between Ethics and Aesthetics: A Social Entrepreneurial Perspective to Sustainable Fashion Brand (Juxta) Positioning. J. Glob. Mark. 2020, 33, 377–395. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beard, N.D. The Branding of Ethical Fashion and the Consumer: A Luxury Niche or Mass-market Reality? Fash. Theory 2008, 12, 447–467. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, H.; Liu, H.; Kim, S.J.; Kim, K.H. Sustainable fashion index model and its implication. J. Bus. Res. 2019, 99, 430–437. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Evans, S.; Peirson-Smith, A. The Sustainability Word Challenge: Exploring Consumer Interpretations of Frequently Used Words to Promote Sustainable Fashion Brand Behaviors and Imagery. J. Fash. Mark. Manag. Int. Natl. J. 2018, 22, 252–269. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jung, J.; Kim, S.J.; Kim, K.H. Sustainable marketing activities of traditional fashion market and brand loyalty. J. Bus. Res. 2020, 120, 294–301. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ozdamar Ertekin, Z.; Atik, D. Sustainable Markets: Motivating Factors, Barriers, and Remedies for Mobilization of Slow Fashion. J. Macromark. 2015, 35, 53–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, E.; Weder, F. Framing Sustainable Fashion Concepts on Social Media. An Analysis of #slowfashionaustralia Instagram Posts and Post-COVID Visions of the Future. Sustainability 2021, 13, 9976. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Joergens, C. Ethical fashion: Myth or future trend? J. Fash. Mark. Manag. Int. J. 2006, 10, 360–371. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Conner, M.; Armitage, C. Extending the Theory of Planned Behavior: A Review and Avenues for Further Research. J. Appl. Soc. Psychol. 1998, 28, 1429–1464. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brandão, A.; da Costa, A.G. Extending the theory of planned behaviour to understand the effects of barriers towards sustainable fashion consumption. Eur. Bus. Rev. 2021, 33, 742–774. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hustvedt, G.; Bernard, J. Consumer willingness to pay for sustainable apparel: The influence of labelling for fibre origin and production methods. Int. J. Consum. Stud. 2008, 32, 491–498. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Merli, R.; Preziosi, M.; Acampora, A. How do scholars approach the circular economy? A systematic literature review. J. Clean. Prod. 2018, 178, 703–722. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vehmas, K.; Raudaskoski, A.; Heikkilä, P.; Harlin, A.; Mensonen, A. Consumer attitudes and communication in circular fashion. J. Fash. Mark. Manag. Int. J. 2018, 22, 286–300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ki, C.-W.; E Ha-Brookshire, J. Consumer Versus Corporate Moral Responsibilities for Creating a Circular Fashion: Virtue or Accountability? Cloth. Text. Res. J. 2022, 40, 271–290. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Becker-Leifhold, C.; Iran, S. Collaborative Fashion Consumption-Drivers, Barriers and Future Pathways. J. Fash. Mark. Manag. 2018, 22, 189–208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hvass, K.K.; Pedersen, E.R.G. Toward Circular Economy of Fashion: Experiences from a Brand’s Product Take-Back Initiative. J. Fash. Mark. Manag. 2019, 23, 345–365. [Google Scholar]

- Puspita, H.; Chae, H. An explorative study and comparison between companies’ and customers’ perspectives in the sustainable fashion industry. J. Glob. Fash. Mark. 2021, 12, 133–145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mukendi, A.; Henninger, C.E. Exploring the spectrum of fashion rental. J. Fash. Mark. Manag. Int. J. 2020, 24, 455–469. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, S.H.; Chow, P.-S. Investigating consumer attitudes and intentions toward online fashion renting retailing. J. Retail. Consum. Serv. 2020, 52, 101892. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Machado, M.A.D.; de Almeida, S.O.; Bollick, L.C.; Bragagnolo, G. Second-hand fashion market: Consumer role in circular economy. J. Fash. Mark. Manag. Int. J. 2019, 23, 382–395. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Henninger, C.E.; Bürklin, N.; Niinimäki, K. The Clothes Swapping Phenomenon-When Consumers Become Suppliers. J. Fash. Mark. Manag. Int. J. 2019, 23, 327–344. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ritch, E.L. ‘From a mother to another’: Creative experiences of sharing used children’s clothing. J. Mark. Manag. 2019, 35, 770–794. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, H.; Kwon, T.A.; Zaman, M.; Song, S.Y. Thrift shopping for clothes: To treat self or others? J. Glob. Fash. Mark. 2020, 11, 56–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shen, B.; Wang, Y.; Lo, C.K.; Shum, M. The impact of ethical fashion on consumer purchase behavior. J. Fash. Mark. Manag. Int. J. 2012, 16, 234–245. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McNeill, L.; Moore, R. Sustainable fashion consumption and the fast fashion conundrum: Fashionable consumers and attitudes to sustainability in clothing choice: Sustainable Fashion Consumption and the Fast Fashion Conundrum. Int. J. Consum. Stud. 2015, 39, 212–222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.; Liu, M.T.; Pérez, A.; Chan, W.; Collado, J.; Mo, Z. The importance of knowledge and trust for ethical fashion consumption. Asia Pac. J. Mark. Logist. 2020, 33, 1175–1194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Manchiraju, S.; Sadachar, A. Personal values and ethical fashion consumption. J. Fash. Mark. Manag. Int. J. 2014, 18, 357–374. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stringer, T.; Mortimer, G.; Payne, A.R. Do ethical concerns and personal values influence the purchase intention of fast-fashion clothing? J. Fash. Mark. Manag. Int. J. 2020, 24, 99–120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bürklin, N. Institutional enhancement of consumer responsibility in fashion. J. Fash. Mark. Manag. Int. J. 2019, 23, 48–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morgan, L.R.; Birtwistle, G. An investigation of young fashion consumers’ disposal habits. Int. J. Consum. Stud. 2009, 33, 190–198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gupta, S.; Gwozdz, W.; Gentry, J. The Role of Style Versus Fashion Orientation on Sustainable Apparel Consumption. J. Macromark. 2019, 39, 188–207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jeong, D.; Ko, E. The influence of consumers’ self-concept and perceived value on sustainable fashion. J. Glob. Sch. Mark. Sci. 2021, 31, 511–525. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mishra, S.; Malhotra, G.; Chatterjee, R.; Shukla, Y.S. Impact of self-expressiveness and environmental commitment on sustainable consumption behavior: The moderating role of fashion consciousness. J. Strat. Mark. 2021, 1–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, H.; Lee, M.-Y.; Koo, W. The four faces of apparel consumers: Identifying sustainable consumers for apparel. J. Glob. Fash. Mark. 2017, 8, 298–312. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Suqri, M.N.; Al-Kharusi, R.M. Information Seeking Behavior and Technology Adoption: Theories and Trends; IGI Global: Hershey, PA, USA, 2015; pp. 188–204. [Google Scholar]

- Sarver, V.T. Ajzen and Fishbein’s “Theory of Reasoned Action”: A Critical Assessment. J. Theory Soc. Behav. 1983, 13, 155–164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haines, S.; Lee, S.H. One size fits all? Segmenting consumers to predict sustainable fashion behavior. J. Fash. Mark. Manag. Int. J. 2021, 26, 383–398. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferraro, C.; Sands, S.; Brace-Govan, J. The role of fashionability in second-hand shopping motivations. J. Retail. Consum. Serv. 2016, 32, 262–268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dhir, A.; Sadiq, M.; Talwar, S.; Sakashita, M.; Kaur, P. Why do retail consumers buy green apparel? A knowledge-attitude-behaviour-context perspective. J. Retail. Consum. Serv. 2021, 59, 102398. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Balderjahn, I.; Peyer, M.; Seegebarth, B.; Wiedmann, K.-P.; Weber, A. The many faces of sustainability-conscious consumers: A category-independent typology. J. Bus. Res. 2018, 91, 83–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lundblad, L.; Davies, I.A. The values and motivations behind sustainable fashion consumption. J. Consum. Behav. 2015, 15, 149–162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, H.; Choo, H.J.; Yoon, N. The motivational drivers of fast fashion avoidance. J. Fash. Mark. Manag. Int. J. 2013, 17, 243–260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ritch, E. Consumers interpreting sustainability: Moving beyond food to fashion. Int. J. Retail. Distrib. Manag. 2015, 43, 1162–1181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kopplin, C.S.; Rösch, S.F. Equifinal causes of sustainable clothing purchase behavior: An fsQCA analysis among generation Y. J. Retail. Consum. Serv. 2021, 63, 102692. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bianchi, C.; Gonzalez, M. Exploring sustainable fashion consumption among eco-conscious women in Chile. Int. Rev. Retail. Distrib. Consum. Res. 2021, 31, 375–392. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kong, M.; Ko, H. Why Do Consumers Choose Sustainable Fashion? A Cross-Cultural Study of South Korean, Chinese, and Japanese Consumers. J. Glob. Fash. Mark. 2017, 8, 220–234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khare, A.; Kautish, P. Antecedents to green apparel purchase behavior of Indian consumers. J. Glob. Sch. Mark. Sci. 2022, 32, 222–251. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Davis, L.; Dabas, C. Capturing sustainable fashion purchase behavior of Hispanic consumers in the US. J. Glob. Fash. Mark. 2021, 12, 245–259. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yoon, N.; Lee, H.; Choo, H. Fast Fashion Avoidance Beliefs and Anti-Consumption Behaviors: The Cases of Korea and Spain. Sustainability 2020, 12, 6907. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rahman, O.; Koszewska, M. A study of consumer choice between sustainable and non-sustainable apparel cues in Poland. J. Fash. Mark. Manag. Int. J. 2020, 24, 213–234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ruppert-Stroescu, M.; Lehew, M.L.; Connell, K.Y.H.; Armstrong, C.M. Creativity and Sustainable Fashion Apparel Consumpion: The Fashion Detox. Cloth. Text. Res. J. 2015, 33, 167–182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Central Intelligence Agency. The World Factbook. Available online: https://www.cia.gov/the-world-factbook/ (accessed on 28 February 2023).

- Pauluzzo, R.; Mason, M.C. A multi-dimensional view of consumer value to explain socially-responsible consumer behavior: A fuzzy-set analysis of Generation Y’s fast-fashion consumers. J. Mark. Theory Pract. 2022, 30, 191–212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, J.Y.; Halter, H.; Johnson, K.K.; Ju, H. Investigating fashion disposition with young consumers. Young Consum. 2013, 14, 67–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chaturvedi, P.; Kulshreshtha, K.; Tripathi, V. Investigating the determinants of behavioral intentions of generation Z for recycled clothing: An evidence from a developing economy. Young Consum. 2020, 21, 403–417. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nguyen, M.T.T.; Nguyen, L.H.; Nguyen, H.V. Materialistic values and green apparel purchase intention among young Vietnamese consumers. Young Consum. 2019, 20, 246–263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gadhavi, P.; Sahni, H. Analyzing the “Mindfulness” of Young Indian Consumers in their Fashion Consumption. J. Glob. Mark. 2020, 33, 417–429. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bardey, A.; Booth, M.; Heger, G.; Larsson, J. Finding yourself in your wardrobe: An exploratory study of lived experiences with a capsule wardrobe. Int. J. Mark. Res. 2022, 64, 113–131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mellander, E.; McIntyre, M.P. Fashionable detachments: Wardrobes, bodies and the desire to let go. Consum. Mark. Cult. 2021, 24, 343–356. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mukendi, A.; Davies, I.; Glozer, S.; McDonagh, P. Sustainable fashion: Current and future research directions. Eur. J. Mark. 2020, 54, 2873–2909. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramirez, E. The Consumer Adoption of Sustainability-Oriented Offerings: Toward a Middle-Range Theory. J. Mark. Theory Pract. 2013, 21, 415–428. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koksal, M.H. Psychological and behavioural drivers of male fashion leadership. Asia Pac. J. Mark. Logist. 2014, 26, 430–449. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khare, A. Green Apparel Buying: Role of Past Behavior, Knowledge and Peer Influence in the Assessment of Green Apparel Perceived Benefits. J. Int. Consum. Mark. 2019, 1–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wiederhold, M.; Martinez, L.F. Ethical consumer behaviour in Germany: The attitude-behaviour gap in the green apparel industry. Int. J. Consum. Stud. 2018, 42, 419–429. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, J.; Seo, Y.; Ko, E. Staging luxury experiences for understanding sustainable fashion consumption: A balance theory application. J. Bus. Res. 2017, 74, 162–167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ritch, E.L.; Brownlie, D. Everyday dramas of conscience: Navigating identity through creative neutralisations. J. Mark. Manag. 2016, 32, 1012–1032. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Armstrong, C.M.J. Fashion and the Buddha: What Buddhist Economics and Mindfulness Have to Offer Sustainable Consumption. Cloth. Text. Res. J. 2021, 39, 91–105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jain, S. Factors Affecting Sustainable Luxury Purchase Behavior: A Conceptual Framework. J. Int. Consum. Mark. 2019, 31, 130–146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seo, Y.; Buchanan-Oliver, M. Constructing a typology of luxury brand consumption practices. J. Bus. Res. 2019, 99, 414–421. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, J.; Kang, S.; Lee, K.H. How social capital impacts the purchase intention of sustainable fashion products. J. Bus. Res. 2020, 117, 596–603. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Achabou, M.A.; Dekhili, S.; Codini, A.P. Consumer preferences towards animal-friendly fashion products: An application to the Italian market. J. Consum. Mark. 2020, 37, 661–673. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sobreira, É.; Silva, C.R.M.; Romero, C.B.A. Do empowerment and materialism influence slow fashion consumption? Evidence from Brazil. J. Fash. Mark. Manag. Int. J. 2020, 24, 415–435. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mohr, I.; Fuxman, L.; Mahmoud, A.B. A triple-trickle theory for sustainable fashion adoption: The rise of a luxury trend. J. Fash. Mark. Manag. Int. J. 2022, 26, 640–660. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ekström, K.M.; Salomonson, N. Reuse and Recycling of Clothing and Textiles—A Network Approach. J. Macromark. 2014, 34, 383–399. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pedersen, E.R.G.; Andersen, K.R. Sustainability innovators and anchor draggers: A global expert study on sustainable fashion. J. Fash. Mark. Manag. 2015, 19, 315–327. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Polonsky, M.J. Transformative green marketing: Impediments and opportunities. J. Bus. Res. 2011, 64, 1311–1319. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chun, E.; Joung, H.; Lim, Y.J.; Ko, E. Business transparency and willingness to act environmentally conscious behavior: Applying the sustainable fashion evaluation system “Higg Index”. J. Glob. Sch. Mark. Sci. 2021, 31, 437–452. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carrigan, M.; Moraes, C.; McEachern, M. From conspicuous to considered fashion: A harm-chain approach to the responsibilities of luxury-fashion businesses. J. Mark. Manag. 2013, 29, 1277–1307. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khurana, K.; Ricchetti, M. Two decades of sustainable supply chain management in the fashion business, an appraisal. J. Fash. Mark. Manag. Int. J. 2016, 20, 89–104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ertekin, Z.O.; Atik, D. Institutional Constituents of Change for a Sustainable Fashion System. J. Macromark. 2020, 40, 362–379. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, S.; Song, Y.; Tong, S. Sustainable Retailing in the Fashion Industry: A Systematic Literature Review. Sustainability 2017, 9, 1266. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ashworth, C.J.; Schmidt, R.Ä.; Pioch, E.A.; Hallsworth, A. An Approach to Sustainable ‘Fashion’ E-Retail: A Five-Stage Evo-lutionary Strategy for ‘Clicks-and-Mortar’ and ‘Pure-Play’ Enterprises. J. Retail. Consum. Serv. 2006, 13, 289–299. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goworek, H.; Oxborrow, L.; Claxton, S.; McLaren, A.; Cooper, T.; Hill, H. Managing sustainability in the fashion business: Challenges in product development for clothing longevity in the UK. J. Bus. Res. 2020, 117, 629–641. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hedegård, L.; Gustafsson, E.; Paras, M.K. Management of sustainable fashion retail based on reuse—A struggle with multiple logics. Int. Rev. Retail. Distrib. Consum. Res. 2020, 30, 311–330. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pomodoro, S. Temporary retail in fashion system: An explorative study. J. Fash. Mark. Manag. Int. J. 2013, 17, 341–352. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Materra Secures a Two-Year Funded Pilot in Gujarat to Develop more Sustainable Cotton Farming with Fashion for Good, Kering, PVH and Arvind—MATERRA®. Available online: https://www.materra.tech/blog/pilot-farm-launch (accessed on 3 March 2023).

- U.S. D2C E-Commerce Sales 2021. Available online: https://www.statista.com/statistics/1109833/usa-d2c-ecommerce-sales/ (accessed on 28 February 2023).

- Dey, K.; Mishra, P.K. Mainstreaming blended finance in climate-smart agriculture: Complementarity, modality, and proximity. J. Rural. Stud. 2022, 92, 342–353. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Global Ethical Fashion Market Report Opportunities and Strategies. Available online: https://www.thebusinessresearchcompany.com/report/ethical-fashion-market (accessed on 28 February 2023).

- SAC. Sustainable Apparel Coalition. Available online: https://apparelcoalition.org (accessed on 28 February 2023).

- UNFCCC. About the Fashion Industry Charter for Climate Action. Available online: https://unfccc.int/climate-action/sectoral-engagement/global-climate-action-in-fashion/about-the-fashion-industry-charter-for-climate-action (accessed on 28 February 2023).

| Sl. No. | Barriers to SF | Citations |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | Extra effort needed for consumer education | [104,121] |

| 2 | Lack of capital for certification and materials | [67,121] |

| 3 | Uncertainty regarding the appropriateness of existing certification | [67,106,121] |

| 4 | Preconceptions and skepticism about SF | [67,106,121,124] |

| 5 | Lack of visibility/accessibility to consumers | [121] |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Ray, S.; Nayak, L. Marketing Sustainable Fashion: Trends and Future Directions. Sustainability 2023, 15, 6202. https://doi.org/10.3390/su15076202

Ray S, Nayak L. Marketing Sustainable Fashion: Trends and Future Directions. Sustainability. 2023; 15(7):6202. https://doi.org/10.3390/su15076202

Chicago/Turabian StyleRay, Subhasis, and Lipsa Nayak. 2023. "Marketing Sustainable Fashion: Trends and Future Directions" Sustainability 15, no. 7: 6202. https://doi.org/10.3390/su15076202

APA StyleRay, S., & Nayak, L. (2023). Marketing Sustainable Fashion: Trends and Future Directions. Sustainability, 15(7), 6202. https://doi.org/10.3390/su15076202